Introduction

Job insecurity refers to employees’ ‘perceived potential loss of continuity in a job situation that can span the range from permanent loss of the job itself to loss of some subjectively important features of the job’ (Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, Reference Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt1984: 440).When organisations cannot provide job security, employees tend to have lower job satisfaction and organisational commitment, higher turnover intention, and worse psychological or physical health (e.g., Cheng & Chan, Reference Cheng and Chan2008; Staufenbiel & König, Reference Staufenbiel and König2010; Selenko, Mäkikangas, & Stride, Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas and Stride2017). However, with the fierce competition and rapid changes in the business environment, organisations have to adjust organisational structures, diversify employment contracts, and renew work designs, thereby making job insecurity more prominent and unavoidable (Shoss, Reference Shoss2017). Under the pressure of current business environment, the development of organisations mainly depend on their employees’ job performance, which is directly related to organisational effectiveness (Griffin, Neal, & Parker, Reference Griffin, Neal and Parker2007). Therefore, a crucial question for organisations and employees is how to effectively cope with job insecurity, so that they can maintain job performance.

In order to seek effective strategies, scholars have been committed to identifying moderators that can weaken employees’ negative responses to job insecurity. Both individual factors and work-related factors have been explored (for an overview, see Lee, Huang, & Ashford, Reference Lee, Huang and Ashford2018). For example, if employees have more psychological capital, they will experience less negative reactions to job insecurity (Lam, Liang, Ashford, & Lee, Reference Lam, Liang, Ashford and Lee2015). Likewise, the negative relationship is weaker among employees with an internal locus of control (König, Debus, Häusler, Lendenmann, & Kleinmann, Reference König, Debus, Häusler, Lendenmann and Kleinmann2010). With regard to the moderators of work-related factors, the perception of organisational justice was found to reduce the negative effect of job insecurity on job performance (Wang, Lu, & Siu, Reference Wang, Lu and Siu2015). Besides, some studies found that work-related supports could have a buffering role (Schreurs, van Emmerik, Gunter, & Germeys, Reference Schreurs, van Emmerik, Günter and Germeys2012; Selenko, Mäkikangas, Mauno, & Kinnunen, Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas, Mauno and Kinnunen2013). While the literature has largely made efforts to find moderators, scholars advocate more research should uncover additional work-related factors (Rosen, Chang, Djurdjevic, Eatough, & Erin, Reference Rosen, Chang, Djurdjevic, Eatough, Perrewé, Halbesleben and Rose2010; Shoss, Reference Shoss2017) because work-related factors and/or employees’ perceptions of organisations are important for the theoretical development of job insecurity and for providing information for organisational interventions (Wang, Lu, & Siu, Reference Wang, Lu and Siu2015).

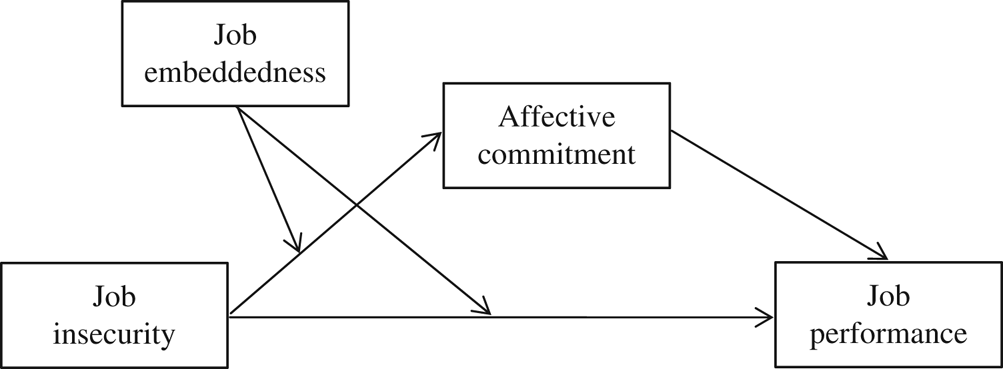

The current study aims to contribute towards the understanding of the impact of job insecurity on job performance by responding to the aforementioned call. In this respect, our study will contribute to the literature in several ways. First, based on the conservation of resources theory (COR; Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989), we expect that job embeddedness, which is defined as the combined forces that keep a person from leaving his or her job (Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez, Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001) and represents the amount of valued resources provided by the organisation (Kiazad, Holtom, Hom, & Newman, Reference Kiazad, Holtom, Hom and Newman2015), will act as a work-related factor buffering the negative effect of job insecurity on job performance. This perspective may provide new explanations for the mixed findings on the job insecurity–performance relationship. Second, we investigate why job embeddedness can assist employees in dealing with job insecurity by examining the mediating role of affective commitment, which reflects an identification with and involvement in the organisation (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991). This study has practical implications for organisations and employees in managing and coping with job insecurity.

Theory and hypotheses

Job insecurity and job performance

Job insecurity refers to employees’ perceived threats regarding the continuity and stability of the current employment (Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, Reference Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt1984). It captures employees’ uncertainties over the future of their jobs and has several characteristics. First, the precondition is that employees want to retain their organisational identity. If employees plan to change jobs or have turnover intentions, they will not have this perception. Second, job insecurity is a subjective experience and contrasts with the designation of jobs as objectively insecure, for example, based on temporary contracts or objective organisational layoffs. Thus, two employees in the same objective working conditions may have very different levels of job insecurity. Third, the threat is directed at the stability and continuity of employees’ current job in the current organisation, rather than their previous or future jobs or their entire career. Finally, job insecurity is a future-focused loss event and the actual loss has not happened (De Witte, Reference De Witte1999). As one of the most prominent and common job stressors, job insecurity generally has negative effects on employees’ work attitudes and behaviours (Shoss, Reference Shoss2017; Lee, Huang, & Ashford, Reference Lee, Huang and Ashford2018).

Notably, empirical evidence linking job insecurity to job performance is equivocal. The majority of research indicate a negative relationship between job insecurity and job performance (e.g., Cheng & Chan, Reference Cheng and Chan2008; Selenko, Mäkikangas, & Stride, Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas and Stride2017). These studies viewed job insecurity as an undesirable change in work-related demands. However, one meta-analysis found a nonsignificant relationship (Sverke, Hellgren, & Näswall, Reference Sverke, Hellgren and Näswall2002); one laboratory experiment indicated that nontraditional undergraduate students in USA facing job insecurity displayed higher levels of productivity (i.e., quantity of copyediting tasks) because of enhanced cognitive arousal than those who did not face job insecurity (Probst, Stewart, Gruys, & Tierney, Reference Probst, Stewart, Gruys and Tierney2007). In addition, a study focusing on Finish university faculties revealed a possible curvilinear relationship between job insecurity and self-reported job performance; that is, faculties reported better job performance at lower and extremely high levels of job insecurity than they did at moderate levels because of high degrees of vigour (Selenko et al., Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas, Mauno and Kinnunen2013).

These inconsistent results may be attributed to two reasons. First, previous studies focused on different definitions and measures of job performance (Probst et al., Reference Probst, Stewart, Gruys and Tierney2007). They have assessed job performance as organisational citizenship behaviour (e.g., Lam et al., Reference Lam, Liang, Ashford and Lee2015; Schreurs, van Emmerik, Günter, & Germeys, Reference Schreurs, van Emmerik, Günter and Germeys2012) or task performance via self-reports (e.g., Selenko et al., Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas, Mauno and Kinnunen2013; Selenko, Mäkikangas, & Stride, Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas and Stride2017; Schreurs et al., Reference Schreurs, van Emmerik, Günter and Germeys2012), supervisory ratings (Wang, Lu, & Siu, Reference Wang, Lu and Siu2015), and objective data (Probst et al., Reference Probst, Stewart, Gruys and Tierney2007). Following previous studies (Schreurs et al., Reference Schreurs, van Emmerik, Günter and Germeys2012; Selenko et al., Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas, Mauno and Kinnunen2013; Selenko, Mäkikangas, & Stride, Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas and Stride2017), we will relate job insecurity to task performance, which is recognised by the formal reward systems and specified explicitly in the job description (Williams & Anderson, Reference Williams and Anderson1991). Task performance is more relevant to job preservation than other factors because it is basic to organisational objectives and the main criteria for judging whether to renew employees’ contracts especially in Chinese private manufacturing companies. Besides, this study assesses task performance by means of self-report measures, the utility of which has been confirmed by research on job insecurity and job performance (Gilboa, Shirom, Fried, & Cooper, Reference Gilboa, Shirom, Fried and Cooper2008). Employees know well how they behave under stress, and thus, they will provide more accurate information about their own performance (Griffin, Neal, & Parker, Reference Griffin, Neal and Parker2007).

Another reason for the conflicting relationships between job insecurity and job performance is that individuals interpret and react to job insecurity differently. As a typical stressor, it is traditionally regarded as a hindrance stressor, which induces tension and nervousness in employees. Employees with increasing tension are not able to allocate sufficient energy to their tasks, resulting in impaired job performance. Conversely, some employees consider job insecurity as a challenge stressor, and thus, they may be motivated to make efforts to preserve their jobs or reduce the risk of job loss. Employees utilise job performance as a coping strategy and work hard in an attempt to improve it (Gilboa et al., Reference Gilboa, Shirom, Fried and Cooper2008). Therefore, in the next section, we focus on the condition (i.e., the moderator) that affects employees’ interpretations of and reactions to job insecurity.

Job embeddedness, job insecurity, and job performance

Job embeddedness is defined as ‘a broad constellation of influences on employee retention’ (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001: 1108). It is based on research on embedded figures and field theory (Lewin, Reference Lewin1951). Embedded figures immerse individuals in their backgrounds and become part of their surroundings. Similarly, field theory posits that there is a perceptual life space that surrounds individuals, and that many aspects of life are attached or connected to it. Embeddedness aggregates a variety of environmental, psychological, and social forces and enmeshes individuals into a psychological field or life space. These combined forces interact to impact individuals’ decision-making. Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001) propose three causal indicators to show one’s degree of on- and off-the-job embeddedness: links (the formal or informal ties to one’s organisation and community), fit (the compatibility of one’s values, skills, and preferences with one’s organisationand community), and sacrifice (the psychological, social, or material costs of leaving one’s organisation and community). More embedded employees experience greater levels of any or all of these dimensions.

Job embeddedness is originally conceived to explain why employees choose to stay in their organisations. As this concept has been developed further, it is increasingly related to other work behaviours such as job performance, creativity, and work–family conflict (William Lee, Burch, & Mitchel, Reference William Lee, Burch and Mitchell2014). At present, we know little about how job embeddedness interacts with negative work experiences to affect employees’ working behaviours; hence, this study explored the effect of its interaction with job insecurity on job performance. We chose to focus on the interaction of on-the-job embeddedness, rather than off-the-job embeddedness, with job insecurity, because this study aimed to identify work-related factors that could affect the relationship between job insecurity and job performance. On-the-job embeddedness is determined by work-related fit, sacrifices, and links, thus it should interact more strongly with job insecurity than off-the-job embeddedness. Moreover, previous studies have provided evidence that on-the-job embeddedness plays a stronger role in predicting working behaviours and attitudes (e.g., Burton, Holtom, Sablynski, Mitchell, & Lee, Reference Burton, Holtom, Sablynski, Mitchell and Lee2010; Jiang, Liu, McKay, Lee, & Mitchell, Reference Jiang, Liu, McKay, Lee and Mitchell2012).

Resources that individuals possess play an important role among employees in interpreting and dealing with work stress (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989). The basic tenet of COR theory is that individuals strive to retain, protect, and build resources they value (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989). When there is a threat to valued resources, employees may protect them by engaging in proactive coping (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). Job embeddedness is the result of the accumulation of individual resources in the current organisation (Halbesleben & Wheeler, Reference Halbesleben and Wheeler2008). More embeddedness means that employees gain more valued resources from the organisation. For example, sacrifices represent valued resources that have accumulated over time, such as retirement benefits and social networks. Individuals become increasingly protective of such resources as they increase (i.e., high sacrifices), because they are difficult to obtain and special to the current organisation (Kiazad et al., Reference Kiazad, Holtom, Hom and Newman2015). Further, the first corollary of COR theory states that individuals who are well endowed with resources because of their own efforts and their place in society are less vulnerable to resources loss and more capable of enhancing future resources (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989: 349). Job embeddedness can provide instrumental resources to employees (Kiazad et al., Reference Kiazad, Holtom, Hom and Newman2015). Specifically, employees with more connections with colleagues (i.e., high links) have better access to advice and receive supports on the job. Employees who hold acquired particular skills that match with their current organisations (i.e., high fit) have intrinsic motivation to fulfil tasks. These resources can help employees better meet job demands and protect against future losses. Therefore, COR theory highlights the potential value of job embeddedness for employees in dealing with work stress.

Considering the context of job insecurity, employees may become stuck in a performance management dilemma. Job insecurity denotes a threat to the employment status (König et al., Reference König, Debus, Häusler, Lendenmann and Kleinmann2010), along with the potential loss of several valued resources, such as financial and social resources (De Witte, Reference De Witte1999). Some employees may perceive job insecurity as a hindrance stressor and worry that working hard is fruitless because the organisation makes the final decisions regarding firing. Thus, they show a withdrawal response. However, some employees may deem job insecurity as a challenge stressor, and therefore, work hard to demonstrate their value and reduce the risk of resource loss. For embedded employees, embeddedness resources are limited to their current organisation and position. If employees lose their current job, they would not take away the links with colleagues and fit with the organisation (Halbesleben & Wheeler, Reference Halbesleben and Wheeler2008). Thus, embedded employees have to protect more sacrifices, and their desire to preserve jobs is more likely to be motivated. Embedded employees will actively set about positioning themselves in a relatively secure position instead of waiting for the occurrence of job loss (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). Because job performance is valued by the manufacturing organisations, employees will put more efforts into conducting their tasks to minimise the risk of job loss and avoid placing themselves in a more dangerous condition. To the best of our knowledge, no empirical studies have thoroughly examined how job embeddedness influences the relationship between job insecurity and performance. Accordingly, we hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 1: Job insecurity and job embeddedness will have an interactive effect on job performance. Specifically, with greater job embeddedness, the negative relationship between job insecurity and job performance will be weaker.

Mediating role of affective commitment

To alleviate the negative effects of job stress, the basis of organisational interventions is to understand why such negative effects occur (Rosen, Chang, Djurdjevic, & Eatough, Reference Rosen, Chang, Djurdjevic, Eatough, Perrewé, Halbesleben and Rose2010). Therefore, this part explains that the reason for job embeddedness playing as a moderator is that valued resources offset employees’ psychological strain (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989), and employees maintain affective commitment to be valuable for organisations (Zatzick, Deery, & Iverson, Reference Zatzick, Deery and Iverson2015).

Affective commitment describes ‘an emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organisation’ (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991). It is an important workplace attitude and reflects employees’ affection towards the organisation. Affective commitment is identified as the core essence of organisational commitment and emphasises its emotional component (Mercurio, Reference Mercurio2015). Job insecurity usually triggers employees’ emotional responses (Jordan, Ashkanasy, & Hartel, Reference Jordan, Ashkanasy and Hartel2002). Affective commitment has a stronger association with work outcomes such as performance, turnover, and organisational citizenship behaviour (Meyer & Herscovitch, Reference Meyer and Herscovitch2001). Thus, affective commitment is the most likely dimension of organisational commitment that is related to job insecurity. Social exchange theory states that if employees receive benefits from the organisation, they will reciprocate with positive workplace attitudes and behaviours (Blau, Reference Blau1964). However, job insecurity, as an unfavourable work experience, denotes a potential loss of resources and makes the reciprocal relationship between employees and their organisations inconstant. Employees perceive betrayal and a break in the psychological contract. They begin to concern about whether the organisation will fulfil its commitment and continually provide valued resources. Thus, employees facing job insecurity generally have low affective commitment. An empirical study focusing on Belgian bank employees has demonstrated that job insecurity is negatively related to affective commitment (Schumacher, Schreurs, Van Emmerik, & De Witte, Reference Schumacher, Schreurs, Van Emmerik and De Witte2016). Some meta-analyses also indicate that job insecurity can lead to less affective commitment (Cheng & Chan, Reference Cheng and Chan2008; Sverke, Hellgren, & Näswall, Reference Sverke, Hellgren and Näswall2002).

According to COR theory, individuals with more resources are less vulnerable to resources loss and more capable of enhancing future resources (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989). Put differently, the availability of valued resources can reduce the impact of stress by providing psychological and instrumental resources for coping with stress. We expect that embedded employees will be capable of maintaining positive work attitudes in the context of job insecurity. As stated above, highly embedded employees have important instrumental resources, such as skills matched with job requirements and a high level of interconnectedness with coworkers. It is easier for them to obtain technical and contextual knowledge and information via their coworkers or supervisors. These instrumental resources can enable employees to resist tension better and give them the confidence to quickly adjust to job insecurity. In a meta-analysis, Johnson and Eagly (Reference Johnson and Eagly1989) found that highly involved employees were less reactive to stimuli that were inconsistent with their preconceived notions.

Based on COR theory, highly embedded employees have a stronger desire to protect resources (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989) and actively use coping strategies to preserve their current jobs (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). Complemented by social exchange theory, employees with high levels of job embeddedness have a strong desire to remain with the organisation and hold high expectations for future interactions with their organisation (Sekiguchi, Burton, & Sablynski, Reference Sekiguchi, Burton and Sablynski2008). Meanwhile, affectively committed employees are valued because they bring benefits to the organisations. For example, affectively committed employees exhibit higher job performance (Fu & Deshpande, Reference Fu and Deshpande2014). In turn, organisations will reciprocate employees when possible. For instance, affectively committed employees are more likely to be promoted (Shore, Barksdale, & Shore, Reference Shore, Barksdale and Shore1995) and less likely to be laid off (Zatzick, Deery, & Iverson, Reference Zatzick, Deery and Iverson2015). Given the benefits generated by affective commitment, maintaining affective commitment is a reasonable strategy for embedded employees to cope with job insecurity. For these reasons, we believe that highly embedded employees can, because of the help of fit and links, and desire to, because of high expectations for future interactions, maintain positive connections with the organisation. Thus, when employees have high levels of job embeddedness, their affective commitment is less influenced by job insecurity. We provide the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Job insecurity and job embeddedness will have an interactive effect on affective commitment. Specifically, with greater job embeddedness, the negative relationship between job insecurity and affective commitment will be weaker.

Employees with high levels of affective commitment to the organisation not only identify with their work but also are more motivated to proactively and enthusiastically engage knowledge and skills towards their tasks (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991). Some studies have revealed that affective commitment is positively linked with job performance (e.g., Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002; Fu & Deshpande, Reference Fu and Deshpande2014). Because affectively committed employees have values and goals that are consistent with the organisation, they are more inclined to maintain their jobs by making efforts to meet organisational expectations (Leong, Randall, & Cote, Reference Leong, Randall and Cote1994). Thus, affective commitment enables employees to better allocate resources to cope with job stress and exhibit better job performance. We expect that the interaction effect of job insecurity and job embeddedness on affective commitment will carry over to employees’ job performance. The hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 3: Affective commitment will mediate the interaction effect of job insecurity and job embeddedness on job performance. Specifically, the indirect effect of job insecurity on job performance via affective commitment will be weaker at high levels of job embeddedness.

Figure 1 represents the theoretical hypothesis model.

Figure 1. Theoretical model

Method

Sample and data collection

Data were collected from contract employees in two large Chinese manufacturing companies located in the north part of China. Job insecurity is prominent among their employees. The two companies have been flattening their organisational structure since 2017 and are implementing the ‘lowliest place elimination’ system. Employees in the two private manufacturing companies re-sign labour contracts based on their performance and organisational development every three years. These operational and management styles reflect the characteristics that are typical of the majority of private manufacturing companies in the north area of China. We contacted the companies’ human resources departments, explained the research purpose, and invited them to participate in our study.

After their consent, we collected data by administering questionnaires on-site. To limit employees’ socially desirable responses, we conducted the survey as per the following procedure, which was consistent with previous studies (e.g., Probst et al., Reference Probst, Stewart, Gruys and Tierney2007; Vander Elst, Richter, Sverke, Näswall, De Cuyper, & De Witte, Reference Vander Elst, Richter, Sverke, Näswall, De Cupyer and De Witte2014). First, we stated the purpose of the study and confirmed that the employees participated in the survey voluntarily. Second, we emphasised and assured the confidentiality and anonymity of the participants’ responses. We promised the employees that their employers would not gain access to their answers and subsequently distributed the questionnaires in envelopes. Finally, we collected the questionnaires after their completion in person and sealed the envelope in their presence.

Surveys were delivered to 1,128 participants, of whom 970 participants responded (with a response rate of 85.99%). After removing invalid surveys because of missing data, the final sample consisted of 725 participants, which constituted an effective response rate of 64.27%. Among the final sample, 59.20% were male. The average age of respondents was 28.24 years (SD=4.42), and average tenure was 4.98 years (SD=3.96). The education level of the respondents was as follows: junior college or below: 59.86%, bachelor: 35.45%, and master or above: 4.69%.

Measures

This study adopted reliable and valid constructs effectively used in previous studies. All variables were measured by a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1=‘strongly disagree’ to 5=‘strongly agree.’ The survey items were translated into Chinese with the support of two professors whose main research area is organisational behaviour. We followed the translation–back-translation procedure suggested by Brislin (Reference Brislin1980) in order to verify that the Chinese version has high degrees of validity and accuracy in Chinese context.

Job insecurity

Job insecurity was captured using a 10-item scale from Huang, Niu, Lee, and Ashford (Reference Huang, Niu, Lee and Ashford2012). Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Niu, Lee and Ashford2012) developed these items based on Chinese employees to measure the affective aspects of job insecurity. The scale emphasises employees’ emotional experience of being concerned about the uncertainty regarding his or her job in the future. A sample item is ‘I am worried that this company will fire me any time’. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in our study was 0.90.

Affective commitment

The 6-item scale developed by Meyer, Allen, and Smith (Reference Meyer, Allen and Smith1993) was adopted to measure affective commitment. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements such as ‘I am glad to continue my work in this company’. The Cronbach’s α coefficient in our sample was 0.87.

Job performance

Job performance was assessed using the 7-item scale developed by Williams and Anderson (Reference Williams and Anderson1991). Participants were asked to evaluate the degree of meeting their job-role requirements in daily work. A sample item is ‘I adequately complete assigned duties’. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the job performance scale was 0.90.

Job embeddedness

Job embeddedness was measured by a 7-item global embeddedness measure developed by Crossley, Bennett, Jex, and Burnfield (Reference Crossley, Bennett, Jex and Burnfield2007), which focuses on the degrees of attachment or ties to the organisation. Participants were asked to rate their agreement with statements such as ‘I’m too caught up in this organisation to leave’. The Cronbach’s α coefficient in our sample was 0.81.

Control variables

We controlled for the possible influences of participants’ age, gender, education, and tenure on job embeddedness, affective commitment, and job performance. Previous studies suggest that employees with longer organisational tenure (in years) were more likely to have high levels of on-the-job embeddedness (Crossley, Bennett, Jex, & Burnfield, Reference Crossley, Bennett, Jex and Burnfield2007) and affective commitment (Lapointe & Vandenberghe, Reference Lapointe and Vandenberghe2017); older employees (in years) tend to have more on-the-job embeddedness (Crossley et al., Reference Crossley, Bennett, Jex and Burnfield2007); more educated employees and male employees have a higher propensity for job performance (Selenko et al., Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas, Mauno and Kinnunen2013; Selenko, Mäkikangas, & Stride, Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas and Stride2017).

Gender and education were controlled as dummy variables. They were codified as follows: gender (0=‘male’; 1=‘female’); junior college or below (1=‘junior college or below’; 0=‘bachelor’; 0=‘master or above’), bachelor (0=‘junior college or below’; 1=‘bachelor’; 0=‘master or above’).

Results

Test of measures and measurement model

First, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to examine the factor structure of each construct separately. The constructs used in this study were unidimensional; therefore, we expected that all the items of each measure would load on one factor. The principal component analysis method with eigenvalues greater than 1 was adopted in the exploratory factor analysis. Results showed that one factor was identified for all measures. Specifically, the factor of job insecurity accounted for 54.32% of the total variance; job embeddedness, 47.20%; affective commitment, 61.38%; and job performance, 62.57%.

Second, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to examine the distinctiveness of all self-reported variables. In line with previous research (e.g., Huang et al., Reference Huang, Niu, Lee and Ashford2012; Dane & Brummel, Reference Dane and Brummel2014; Lam et al., Reference Lam, Liang, Ashford and Lee2015), this study adopted the partial disaggregation method (i.e., item parcel) when comparing different models. Parcelling items can help models reduce sampling errors, improve the stability of indicators, and simplify the interpretation of model parameters (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, Reference Little, Cunningham, Shahar and Widaman2002). Parcelling was adopted in this study because we used preexisting scales that demonstrated reliability and unidimensionality and focused on the relationships among variables rather than the loads of specific items on latent constructs. Three indicators produce a just-identified latent variable (Little et al., Reference Little, Cunningham, Shahar and Widaman2002); thus, we created three parcels of items for variables measured by over 3 items. Items were parcelled by the item-to-construct balance approach as recommended by Little, Cunningham, Shahar, and Widaman (Reference Little, Cunningham, Shahar and Widaman2002), and 12 parcels were generated (3 parcels for each variable). Confirmatory factor analysis results showed that the four-factor model (i.e., job insecurity, job embeddedness, affective commitment, and job performance) had a good fit to the data (χ 2=99.78, df=48, TLI=0.99, CFI=0.99, RMSEA=0.04), which was significantly better than the fit of a three-factor model (e.g., job insecurity, job embeddedness, and affective commitment and job performance combined; χ 2=992.23, df=51, TLI=0.76, CFI=0.82, RMSEA=0.16), a two-factor model (e.g., job insecurity and job embeddedness combined, and affective commitment and job performance combined; χ 2=2,432.06, df=53, TLI=0.42, CFI=0.53, RMSEA=0.25), or a one-factor model (i.e., all items were loaded on one factor; χ 2 =3,186.42, df=54, TLI=0.25, CFI=0.39, RMSEA=0.28). All items in the four-factor model loaded significantly on their corresponding factors.

Further, this study tested the validity of measures. According to Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981), evidence of convergent validity is present when the composite reliability and average variance extracted of each latent variable are greater than 0.70 and 0.50, respectively; discriminant validity is demonstrated when the square root of AVE of a given variable exceeds the corresponding latent variable correlations in the same row and column. As shown in Table 2, results met the requirements and, therefore, provided support for both convergent and discriminant validity.

Descriptive statistical analyses

Self-rated measures are appropriate for private events and affective responses. In addition, we assume that employees themselves know more about their own job conditions, such as job insecurity, job embeddedness, and affective commitment, and that they understand well how they behave in this condition. Therefore, all variables in this study are from participants’ self-reports. However, it is possible to create common method bias. Accordingly, we used the Harman single-factor method (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003) to test whether this was problematic. The result showed that a single factor only accounted for 20.99%, which was less than 25%, so a common method bias was not a significant problem in this study.

Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s αs, and bivariate correlations for all study variables are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Correlation table and descriptive statistics

Note: N=725. Cronbach’s α values are in parentheses. Age: years; Tenure: years.

a Dummies: The reference groups are female and master or above.

na=not applicable.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Table 2. Convergent and discriminant validity of measures

Note: N=725. The bold numbers in diagonal are square roots of AVEs.

AVE=average variance extracted; CR=composite reliability; MSV=maximum shared variance.

Hypothesis testing

We conducted hierarchical regression analyses using SPSS to test the hypotheses as follows: first, we entered the demographic variables (age, male, tenure, junior college or below, bachelor) to control their effects; next, job insecurity and job embeddedness were entered into the regression; and finally, the interaction of job insecurity and job embeddedness were entered. Tables 3 and 4 show the moderation effects of job embeddedness. Hypothesis 1 stated that job embeddedness would moderate the negative relationship between job insecurity and job performance. As shown in Table 3, the interaction was significant (β=0.14, SE=0.02, p<0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. Hypothesis 2, stating that job embeddedness would moderate the negative relationship between job insecurity and affective commitment, was also supported (β=0.14, SE=0.02, p<0.001), as shown in Table 4.

Table 3. Moderation analysis of job insecurity and job embeddedness on job performance

Note: N=725. Age: years; Tenure: years.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

a Dummies: The reference groups are female and master or above.

Table 4. Moderation analysis of job insecurity and job embeddedness on affective commitment

Note: N=725. Age: years; Tenure: years.

a Dummies: The reference groups are female and master or above.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

We plotted conditional slopes at high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1 SD below the mean) levels of the independent and moderator variables (see Figures 2 and 3). Figure 2 shows the effect of the interaction of job insecurity and job embeddedness on job performance. A simple slope test demonstrated that the interaction of job insecurity and job embeddedness was negatively associated with job performance when job embeddedness was lower (simple slope = –0.31, t=–9.66, p<0.001). However, the interaction of job insecurity and job embeddedness was positively related to job performance when job embeddedness was higher (simple slope=0.07, t=2.13, p<0.05). Figure 3 shows the effect of the interaction of job insecurity and job embeddedness on affective commitment. A simple slope test demonstrated that the interaction of job insecurity and job embeddedness was negatively related with affective commitment when job embeddedness was lower (simple slope = –0.30, t=–9.55, p<0.001). However, the interaction of job insecurity and job embeddedness was positively associated with affective commitment when job embeddedness was higher (simple slope=0.064, t=2.02, p<0.05).

Hypothesis 3 stated that affective commitment would mediate the interaction effect of job insecurity and job embeddedness on job performance. To test this mediated moderation model, Hayes’ (Reference Hayes2013) PROCESS Model 8 was used. A bias-corrected confidence interval (95%) and bootstrapping with 10,000 repetitions were employed to estimate the indirect effect of job insecurity on job performance via affective commitment. Employees’ age, gender, tenure and education were included as covariates. All variables were standardised (Table 5). The results indicated that the overall indirect effect of affective commitment was 0.10 (SE=0.02) with a 95% CI of [0.063, 0.139]. Furthermore, at higher levels of job embeddedness (1 SD above the mean), job insecurity had an indirect effect on job performance via affective commitment (β=0.05, SE=0.02), and the 95% confidence interval excluded zero (95% CI [0.003, 0.094]). At lower levels of job embeddedness (1 SD below the mean), the conditional indirect effect also reached significance (β=–0.15, SE=0.03), and the 95% confidence interval did not contain zero (95% CI [–0.219, –0.094]). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Figure 2. Two-way interaction effect of job insecurity and job embeddedness on job performance

Figure 3. Two-way interaction effect of job insecurity and job embeddedness on affective commitment

Table 5. Mediation analysis of job insecurity

Note: N=725. Age: years; Tenure: years.

a Dummies: The reference groups are female and master or above.*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we explored how job embeddedness moderated the negative effect of job insecurity on job performance and the mediating role of affective commitment in this process. Results of this study supported our arguments. Specifically, we demonstrated that job insecurity was negatively associated with job performance at low levels of job embeddedness and, surprisingly, that job insecurity was positively related to job performance at high levels of job embeddedness. Moreover, the moderated mediation analyses showed that affective commitment, a positive emotional response to work experience, was a key mediator.

When job-insecure employees are faced with a performance management dilemma, job embeddedness can affect their interpretation of job insecurity. That is, with greater job embeddedness, employees not only have more resources to protect but also have instrumental resources to deal with the stress. In such a condition, they will become more concerned with trying to stay in the organisation, and interpret job insecurity as a challenge stressor. More links and high fit help restore their affective commitment. Consequently, they make greater efforts to improve job performance. This result is also consistent with the suggestion of earlier empirical research based on the forced compliance model: when employees experience negative work situations, those with a high level of job embeddedness increase their job performance and organisational citizenship behaviours to avoid more adverse situations in the future (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Holtom, Sablynski, Mitchell and Lee2010). Some theoretical work also suggests that in order to retain their job, employees who face job insecurity will concentrate on performance aspects that are typically rewarded by the organisation (Probst & Brubaker, Reference Probst and Brubaker2001). In addition, our results provide evidence that job-insecure employees regard job performance as an effective coping strategy to show their worth (Selenko et al., Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas, Mauno and Kinnunen2013). Though, employees tend to overreport their performance, self-rated performance reflects employees’ motivation to perform and self-enhancing tendency (Gillboa et al., 2008). Hence, job-insecure employees report high job performance in an attempt to make a favourable impression to reduce the likelihood of job loss. On the contrary, with low job embeddedness, employees have low expectations for future interaction with individuals and groups in their organisation and are more likely to change their jobs (Sekiguchi, Burton, & Sablynski, Reference Sekiguchi, Burton and Sablynski2008). Thus, when they experience job insecurity, their psychological contract is breached and they have less affective commitment, which ultimately results in fewer efforts for performing tasks.

Implications

Our research makes three distinct theoretical contributions to the literature. First, employee’s job insecurity is increasingly prominent in uncertain work contexts. Hence, more studies are necessary to discover methods to help employees withstand the stress of potential resource loss and maintain job performance. Given the mixed relationships between job insecurity and job performance, scholars have recently suggested that a promising direction is to give greater attention to work-related factors (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Chang, Djurdjevic, Eatough, Perrewé, Halbesleben and Rose2010). Drawing on COR theory, we contribute uniquely to this inquiry by identifying job embeddedness, a key indicator of the amount of resources, as an important boundary condition. Second, our research enriches the nomological network of job embeddedness by demonstrating its positive role in adverse work situations based on Chinese samples. Job embeddedness may play a positive role, as well as a negative role, in adverse work situations. This study explored its positive role as a moderator in addressing job insecurity. In line with embeddedness constrains behaviour by emphasising resource conservation (Kiazad et al., Reference Kiazad, Holtom, Hom and Newman2015), job-insecure employees maintain job performance because they strive to protect valued resources and can take advantage of fit and links to better cope with stress. Moreover, the study sample was from Chinese companies, in response to the call of scholars for more job embeddedness research conducted in nonwestern environments (Zhang, Fried, & Griffeth, Reference Zhang, Fried and Griffeth2012). Third, our research also offers a better understanding of the mechanism between job insecurity and job performance. Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt (Reference Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt2010) have proposed that further research is needed to explain the relationships between job insecurity and its consequences through identifying more mediating variables. Affective commitment is one such mechanism, as it has been demonstrated to link negative workplace perceptions to job performance (Restubog, Bordia, & Tang, Reference Restubog, Bordia and Tang2006).

Our research also has significant practical implications for organisations. First, it is beneficial for organisations to understand that job insecurity is not always a bad thing. The negative influence of job insecurity on job performance can be changed by a high level of job embeddedness. Highly embedded employees will put greater effort into improving their job performance. Thus, organisations can benefit from improving the level of job embeddedness for their employees. Organisations should attempt to create organisational cultures where fit, links, and sacrifices can be enhanced (William Lee, Burch, & Mitchell, Reference William Lee, Burch and Mitchell2014). For example, work by Porter, Woo, and Campion (Reference Porter, Woo and Campion2016) can help us understand how internal and external networking increase job embeddedness. In addition, organisations can give adequate stress to highly embedded employees to inspire their higher levels of job performance, such as releasing some signals of job insecure. Second, since affective commitment is a mediation mechanism, organisations should find ways, such as improving organisational support (Panaccio & Vandenberghe, Reference Panaccio and Vandenberghe2009) and supervisory mentoring (Lapointe & Vandenberghe, Reference Lapointe and Vandenberghe2017), to build such a working environment to maintain and improve employees’ emotional attachment.

Limitations and future research

As is the case with all studies, this study also has some limitations. First, we used data from self-reporting questionnaires, which may lead to a common method bias. Although it is reasonable to collect data regarding job insecurity, job embeddedness, and affective commitment using self-reports because these constructs reflect individuals’ perceptions or internal states, self-reported job performance measures may be susceptible to socially desirable responses, such as trying to create a positive impression of themselves by exaggerating one’s performance. There is evidence confirming the utility of self-reported job performance in research on job insecurity (Gilboa et al., Reference Gilboa, Shirom, Fried and Cooper2008). Different measures of job performance are not exclusive, thus, it is necessary for future research to confirm the roles of job embeddedness and affective commitment in the job insecurity–job performance relationship through more objective measures of job performance.

Second, our study used a cross-sectional design, and the causal relationships among job insecurity, affective commitment, job performance, and job embeddedness cannot be reliably ascertained. Thus, it may also be the case that employees who have higher performance display higher affective commitment. Whereas the proposed causal directions in this study are in line with COR and social exchange theory. Further, drawing on Lee, Huang, & Ashford (Reference Lee, Huang and Ashford2018) theoretically anchored taxonomy of the consequences of job insecurity and empirical studies showing longitudinal effects of job insecurity on the aforementioned outcomes (e.g., Probst, Gailey, Jiang, & Bohle, Reference Probst, Gailey, Jiang and Bohle2017; Vander Elst et al., Reference Vander Elst, Richter, Sverke, Näswall, De Cupyer and De Witte2014), we are relatively confident about the results. To further strengthen these findings, longitudinal and experimental designs are needed.

Third, we also note that a further consideration in assessing the findings of this study is the possibility that there are additional variables that may mediate the relationship between the interaction of job insecurity and job embeddedness and job performance. According to the theoretical construction, the threat of potential loss of resources caused by job insecurity can lead to emotional responses. Thus, there may be some other affective or attitude variables (e.g., job satisfaction, work engagement) acting as mechanisms. Future research should study other mechanisms.

Fourth, this study mainly focuses on affective characteristics of job insecurity, observing employees’ emotional experiences and stress regarding their fear of losing current jobs. However, job insecurity also encompasses other characteristics, such as cognition (i.e., the awareness of possible job loss), quantity (i.e., concerning about the future existence of the present job), and quality (i.e., perceived threats of impaired quality in the employment relationship; Ashford, Lee, & Bobko, Reference Ashford, Lee and Bobko1989). An interesting topic for future research is to test whether the different characteristics of job insecurity have different effects on job performance under the role of job embeddedness.

Finally, all the data are collected from two Chinese private manufacturing companies, which limit the external validity of our findings. Even though collecting all of our data from a single industry could control some potential industry-level confounding variables, it is necessary to conduct studies in multiple industries to improve the generalisability of our hypothesised model.

Conclusion

This study focuses on the less straightforward effect of job insecurity on job performance. We have investigated the moderating role of job embeddedness and the mediating role of affective commitment. Highly embedded in the organisation can help employees less vulnerable to job insecurity. More valuable resources brought by job embeddedness assist employees in identifying job insecurity as a challenge stressor, and their resources preservation motivation will restore affective commitment and better perform to keep their job. We believe this study provides a new work-related factor for understanding the job insecurity–job performance relationship. It gives important implications for further investigations of how organisations promote employees’ job performance in the face of job insecurity.

About the Authors

Shanshan Qian is a doctoral student at Business School, Nankai University, China. Her research primarily focuses on work-related stress, in particular job insecurity.

Qinghong Yuan is a professor at Business School, Nankai University, China. His research interests are work-related stress, job loss, and collective turnover.

Wanjie Niu is a doctoral student at Business School, Nankai University, China. She is interested in the impact of relational identification on employee’s proactive behaviors, such as voice and innovative behavior.

Zhaoyan Liu is a doctoral student in Department of Human Resource Management, Nankai University, China. Her research concerns organizational identification and turnover.