1. Introduction

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy has adverse fetal and child outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, preterm delivery, and low birthweight [Reference Murin, Rafii and Bilello1–Reference Einarson and Riordan3]. Approximately 54% of women quit smoking prior to or during pregnancy [4]. Unfortunately, around 50% will relapse within the first 6 months postpartum, with the number climbing even higher at one year postpartum [Reference Tong, Jones, Dietz, D’Angelo and Bombard5–Reference Fingerhut, Kleinman and Kendrick9]. Smoking postpartum increases the risk of smoking-related disease for women and has negative effects on childhood development due to secondhand smoke (e.g., increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome, respiratory infections, and other diseases) [4, Reference Dybing and Sanner10]. Thus, more research is needed on enrolling postpartum women into clinical trials and supporting them postdelivery to prevent relapse to smoking.

Currently, few treatments have shown efficacy at reducing postpartum relapse to smoking. Treatments include behavioral approaches, (e.g., Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and self-help mailings) [Reference Tong, Dietz and England11–Reference Levine, Cheng, Marcus, Kalarchian and Emery14] and nicotine replacement therapy [Reference Su and Buttenheim15, Reference Claire, Chamberlain and Davey16]. Women’s use of these treatments for postpartum relapse prevention is limited. Given the efficacy of pharmacotherapy for relapse prevention outside of pregnancy, more work is needed to expand relapse prevention pharmacotherapy options for those who are postpartum [Reference Einarson and Riordan3, Reference Allen, Thomas and Harrison17–Reference Notley, Blyth, Craig, Edwards and Holland19]. Non-nicotine-containing medications may be indicated for postpartum women who have been abstinent from nicotine during pregnancy due to reluctance to reintroduce nicotine. Bupropion is worth consideration for use in postpartum relapse prevention because it has demonstrated efficacy as a smoking cessation aid [Reference Hays, Hurt and Rigotti20] and is generally safe and well-tolerated, with few side effects [Reference Wellbutrin21]. Bupropion can further reduce nicotine cravings and improve depression, both of which are associated with increased risk for smoking relapse [Reference Burgess, Brown and Kahler22]. For pregnant women, postpartum depression is of particular concern, with up to 20% developing the disorder [Reference Hays, Hurt and Rigotti20, Reference Gavin, Gaynes, Lohr, Meltzer-Brody, Gartlehner and Swinson23, Reference Nonacs, Soares, Viguera, Pearson, Poitras and Cohen24]. Thus, bupropion may be particularly effective at preventing postpartum relapse, in part, because of its antidepressant effects.

One potential concern for use of bupropion for postpartum relapse is the safety for infants who are breastfeeding. LactMed (last updated July 2022), in summarizing data regarding the use of bupropion during lactation, reported that maternal bupropion use results in low concentrations of bupropion and bupropion metabolites in breast milk which would not be expected to cause adverse events in breastfed infants [25]. Bupropion has been studied for postpartum depression in a small sample of women, some of whom were breastfeeding. Bupropion use was not associated with adverse effects on infant health or lactation [Reference Nonacs, Soares, Viguera, Pearson, Poitras and Cohen24]. Investigational use of the medication was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as part of the Investigational New Drug application for this study.

Although there is a need to investigate treatments for prevention of postpartum relapse, clinical trial recruitment for postpartum relapse prevention studies can be quite difficult [Reference Park, Quinn and Chang26]. The most successful recruitment methods for pregnant individuals in the literature include multiple streams of engaging participants, including using clinical registries, mailings through healthcare settings, traditional media, and more recently social media [Reference Park, Quinn and Chang26]. Despite these methods, few clinical trials targeting pregnant and postpartum women meet their recruitment target in the time originally planned [Reference McDonald, Knight and Campbell27]. Previous research has reviewed struggles with recruitment [Reference Park, Quinn and Chang26, Reference Lopez, Simmons, Quinn, Meade, Chirikos and Brandon28–Reference McBride, Emmons and Lipkus30]. Medication trials in pregnant and postpartum women, especially those choosing to breastfeed, may have unique recruitment challenges including greater reticence to accept pharmacological intervention than the general population [Reference Rigotti, Park, Chang and Regan31]. A trial utilizing nicotine replacement therapy among pregnant women identified five main recruitment challenges: low smoking disclosure rate, smoking too few cigarettes, late entry into prenatal care, small potential participant pool, and a high refusal rate [Reference Pollak, Oncken and Lipkus29].

In addition to recruitment being difficult, it is also expensive. For instance, one study investigated the costs of recruiting individuals to join research in which participants received relapse prevention self-help materials and self-report questionnaires. Various strategies such as media advertisements, direct mailings, and healthcare provider outreach were high cost with low yield. Media advertisements resulted in a cost of $6,332 per participant. Outreach calls were successful, but costly as paid staff worked approximately 200-250 hours per month for 1.5 years to successfully recruit 338 people [Reference Lopez, Simmons, Quinn, Meade, Chirikos and Brandon28].

While previous studies have enumerated reasons for low participant accrual and suggested methods for recruitment, very few qualitative studies have been conducted to determine how pregnant women view participation in smoking cessation and relapse prevention research during the postpartum period. Qualitative interviews may be particularly helpful for identifying potential barriers to recruitment and understanding the perceptions of potential participants compared to survey methods or record review, which rely on investigator generated hypothesized barriers [Reference Locock and Smith32].

We are currently conducting a clinical trial testing bupropion for postpartum relapse prevention (BurPPP) [Reference Allen, Thomas and Harrison17]. Like previous research involving the recruitment of pregnant women, participant identification and engagement has been challenging. Over the initial two years of the study, we have been contacted by or reached out to 845 women to assess interest/eligibility. Of these, 135/835 (16%) were screened, 76/835 (9%) were eligible, and only 16/835 (2%) enrolled. Given this low rate of accrual, we conducted exploratory qualitative interviews to assess pregnant women’s interest in (1) remaining abstinent postpartum, (2) using bupropion for relapse prevention, and (3) participating in research studies to address smoking relapse following prenatal abstinence. In this qualitative investigation, we sought to gain insight into pregnant individuals’ attitudes regarding research participation to inform recruitment strategies for future postpartum relapse prevention studies.

2. Methods

2.1. Human Subjects

This study was conducted with approval via the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board (IRB; #00007684, approved November 1, 2019).

2.2. Recruitment

Potential participants were contacted as a part of a larger clinical trial testing the efficacy of bupropion for prevention of postpartum relapse [Reference Allen, Thomas and Harrison17]. Participants were recruited from April 2021 to November 2021. Participants were identified and recruited via the following methods for the full trial and were then asked if they were interested in participating in the qualitative study: (1) letters sent to pregnant individuals in outpatient and inpatient with a smoking history seen at OB/GYN or Family Medicine clinics, (2) self-referral via Facebook ads for the BurPPP trial, (3) advertising across social media platforms managed by a clinical research recruiting firm [33], and (4) in-person recruitment medical settings. Interested individuals were screened for eligibility over the phone. For participants who were eligible for the qualitative study, they were read and sent a study fact sheet conforming to the elements of informed consent and verbal consent was obtained prior to conducting the interviews.

2.3. Participants

Eligible participants were pregnant women who were between 18 and 41 years of age, English speaking, and who endorsed that they either (1) quit smoking during their pregnancy or (2) were considering quitting smoking during their pregnancy. Of note, participant advertisements detailed participation in the larger trial, and they were informed of the qualitative interview during the initial contact. They did not have to be interested in participating in the larger trial to complete the interview.

2.4. Qualitative Data Collection

After obtaining verbal consent, a Bachelor’s-level tobacco treatment specialist (MAH) completed a semistructured interview. The interview guide (Appendix A) gathered general demographic information and assessed attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs surrounding the following topics: (1) pregnancy and quitting, (2) postpartum cessation, and (3) participation in research generally and the BurPPP study, specifically bupropion vs. placebo for postpartum relapse prevention.

All interviews were conducted via telephone and were audio recorded. On average, interviews lasted between 15 and 25 minutes. Participants were compensated with a $25 gift card for their time.

2.5. Data Analysis

Using NViVo Pro, two independent raters (MAH and PF) double-coded all interview transcripts using thematic analysis. A codebook was created and codes refined during meetings between raters. Themes were reviewed and considered in context of previous work. A final codebook was created upon agreement by both raters.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

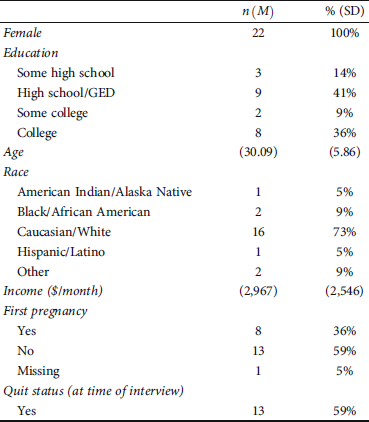

All participants (N = 22) identified as female and were between the ages of 22 and 41 (73% White). Most had completed high school/GED. Monthly household income ranged from $0 to $8,000 with a median monthly income of $1,766 and average of $2,967. For 36% of women, it was their first pregnancy. At the time of the interview, 59% of the participants had quit smoking. See Table 1 for demographics.

Table 1: Participant characteristics (N = 22).

3.2. Perceptions regarding Smoking during Pregnancy

Overall, women were extremely knowledgeable about the risks of smoking during pregnancy and motivated to quit/stay quit. They typically received information on these risks from friends, family members, social media, traditional media, and clinicians. Most participants were certain that quitting smoking was the best decision for their unborn child.

Despite the overall interest in quitting, several participants expressed skepticism about the importance of quitting. These participants told anecdotes about their own previous pregnancies or the pregnancies of other women in which the children had no postpartum difficulties even if the mother had smoked throughout pregnancy.

“I’m in a Facebook group with a lot of smoking soon to be moms and I mean, everybody has been pretty healthy and being born pretty healthy and stuff like that.” (24-year-old White woman)

The perception of being judged for smoking while pregnant varied by smoking status. For those who quit smoking at the beginning of their pregnancy, none reported feeling judged for being a former smoker and many reported experiencing praise for successfully quitting. For those who had difficulty quitting, some reported experiencing judgement, particularly from partners. A couple of women noted that they themselves would judge others if they had smoked during their pregnancy and were unable to quickly quit.

“I haven’t felt personally judged. But if I knew other people that were smoking in pregnancy, I would judge them.” (28-year-old White woman)

3.3. Smoking Cessation during Pregnancy

Participants varied in smoking status at the time of the interview and timing of cessation during pregnancy. Some women quit as soon as they found out they were pregnant (45%), while others quit later in pregnancy (14%), and others still were unable to successfully quit (41%). The majority of abstinent women indicated they quit cold turkey. Many mentioned strategies for staying quit, such as delaying cigarettes or distracting themselves during a craving. For those that had tried nicotine replacement therapy, use was often short lived (e.g., casual use and putting the patch on a few times over a week). This is in line with previous research which has found overall reticence and underuse of nicotine replacement therapy in pregnant women [Reference Bowker, Campbell, Coleman, Lewis, Naughton and Cooper34, Reference McDaid, Thomson and Emery35]. One person noted their provider talked to them about quitting but had not assisted in making a plan or prescribing medication to help fully quit.

3.4. Barriers and Facilitators to Quitting Smoking during Pregnancy

All women expressed some interest in quitting; however, many indicated barriers to quitting successfully. Barriers included personal life stressors as well as partners, friends, and family who smoked. For participants with other children, some described smoking as one of the few times of day when they were alone. For those who had not been able to quit during their pregnancy, most had reduced their cigarettes per day.

Overall motivations for quitting during pregnancy were twofold: (1) personal reasons outside of pregnancy for quitting and (2) concern for the baby’s health. Unrelated to their pregnancy, many women told us that they had already attempted to quit or were starting to think about quitting ahead of finding out they were pregnant. Motivations for quitting smoking prior to pregnancy included money, time, and appearance. The women who were able to quit at the beginning of pregnancy noted that the smell of cigarettes was no longer appealing while pregnant and even exacerbated morning sickness. They noted their aversion to the smell of cigarettes made it easier to quit. For many, there was also strong desire to be as healthy as possible for their baby.

“… It was really exciting news to find that [pregnancy] out and [I] didn’t want to do anything to compromise that.” (31-year-old White woman)

3.5. Postpartum Smoking Plans

Most women, though with some trepidation, planned on staying smoke-free postpartum. They viewed pregnancy as a means to quit for good. Some women, particularly first-time mothers, noted that lifestyle changes associated with parenthood (e.g., not going to bars or clubs where it is tempting to smoke) would make it easier to stay quit.

Overall, participants were quite confident that they would be able to quit and stay quit without assistance. This was true even for participants who had not remained abstinent after previous pregnancies and for those who had not yet quit. These women indicated that staying quit would be difficult, but they believed that this time would be different.

“I don’t plan to smoke after I give birth. And I’m just hoping I can stick it out and not you know, like, crave it anymore.” (23-year-old White woman)

3.6. Attitudes towards Research

Participants overwhelmingly had positive feelings towards research. A few individuals had participated in studies or had some knowledge of research methods from their education. Many expressed enthusiasm for the prospect of helping other pregnant women through research.

“I really liked the idea… It’s helpful for people. I know that a lot of my friends and family… when they’re pregnant, they don’t care if they smoke. You know, because they probably don’t know the information about it.” (37-year-old Native American woman)

By far the biggest reason for disinterest in participation in our trial was concern about taking bupropion. A number of women had heard of bupropion and were aware of its uses for mood as well as some of its side effects. Those who knew little about bupropion were quite concerned about side effects for themselves as well as risk to nursing infants. Two individuals noted they would prefer to receive the placebo pill as they were worried about taking medication. Even participants who were generally open to taking medication noted that taking medication for a study was unappealing.

“But like maybe people are just scared. You know, like, the medication might have like, some sort of side effects that they didn’t know about or something like that.” (24-year-old White woman)

Overall, women who were planning on breastfeeding were the most concerned about taking the medication. Though as part of the Investigational New Drug (IND) process, our medical team, the IRB, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) determined the amount of bupropion transferred to the baby via breast milk was unlikely to cause harm, participants were still concerned about risk to the baby [36, Reference Sachs, Committee on Drugs and Frattarelli37]. Many expressed hesitation about taking bupropion or a desire to discuss the medication with their healthcare provider.

“I don’t want that medication in the breast milk either. I just would, would rather not. And that’s my own… I know that they say it’s safe, I just, I’m so hesitant on it.” (34-year-old White woman)

Outside of the specific medication for the study and concerns about taking medication while nursing, a number of participants expressed hesitancy about medication use generally and skepticism about chemicals in pills. None of these individuals drew a comparison between the chemicals in medications to chemicals in cigarettes. Many expressed particular disinterest in taking medication for relapse prevention because they did not believe they were at risk for relapse.

“I’m not too fond of taking meds, trying pills and stuff. I don’t know, I get this anxiety when it comes to taking medication.” (41-year-old Black woman)

Similarly, the second most common reason for lack of interest in the study was that for those who had quit or were confident they would quit during their pregnancy they found little reason to be in a relapse prevention study.

“I mean, I hate to say it, but like, I would be a very bad test subject, because like, I have no interest in picking up another cigarette like... The want is already gone.” (33-year-old White woman)

We asked participants about ways to structure the study to make them more likely to participate. Overall, participants were concerned about making new time commitments while beginning parenthood. Due to time concerns, there was a preference for online surveys over visits and virtual over in-person visits. Some expressed interest in a person to talk to for accountability purposes.

“I just didn’t know if I could commit to those weekly check-ins and you know, having the time to sit down and do a 60-minute interview via zoom, you know, once a week like that.” (31-year-old White woman)

Compensation was not a large motivator for study participation. However, participants preferred larger compensation increments over fewer visits or a shorter timeframe.

4. Discussion

In this qualitative study of perceptions of participation in postpartum relapse prevention research, we found that interest in quitting smoking and staying quit is high among women in pregnancy and postpartum. There is some interest in behavioral support; however, these interests were overshadowed by the burden of time associated with said support. Attitudes towards research in general were positive; however, interest in participating in relapse prevention studies was low, partly due to the burdens of new motherhood.

Women in our study overestimated their likelihood of staying quit postpartum, with nearly all believing they would be able to remain abstinent. In epidemiological studies, approximately half of women quit smoking during pregnancy [4, Reference Schneider, Huy, Schütz and Diehl38]. However, in the first year postpartum, most women will relapse (within the first six months 40-50% may relapse, [Reference Jones, Lewis, Parrott, Wormall and Coleman6, Reference Harmer and Memon7] while at twelve months relapse rates climb to 70-90% [4, Reference Rockhill, Tong, Farr, Robbins, D’Angelo and England8, Reference Fingerhut, Kleinman and Kendrick9, Reference Solomon, Higgins, Heil, Badger, Thomas and Bernstein39, Reference Letourneau, Sonja, Mazure, O’Malley, James and Colson40]). Women reported getting information about the importance of abstinence during pregnancy from family, friends, media sources, and their healthcare team. Thus, healthcare providers appear to be a trusted information source for communicating risk of relapse as well as the risks and benefits of pharmacological and behavioral interventions. Similar research has also shown healthcare clinicians as trusted resources for relapse prevention [Reference Notley, Brown and Bauld41, Reference Thomson, McDaid and Emery42]. Educating pregnant individuals on their high risk of relapse may increase interest in postpartum relapse prevention treatments.

In general, pregnant women were reluctant to take medication to stop smoking and/or stay quit postpartum. This attitude was particularly true for women who planned to breastfeed. Prior literature is consistent with these findings, showing that postpartum individuals are unlikely to use pharmacological treatments for tobacco dependence [Reference Rigotti, Park, Chang and Regan31, Reference Thomson, McDaid and Emery42, Reference Tibuakuu, Okunrintemi and Jirru43]. The Health Belief Model may partially explain this. The Health Belief Model states that health behavior is guided by the motivation to avoid illness (smoking-related disease or adverse effects on child health) and the belief that engaging in a particular behavior will prevent illness. According to the model, the likelihood of engaging in a health behavior (e.g., taking medication to prevent relapse) is a combination of the perceived severity of the illness, the perceived susceptibility to illness, the perceived benefit of engaging in the behavior, and the perceived barriers of engaging in the behavior. In this case, pregnant women did not feel they were susceptible to illness because they did not believe they would relapse, and they perceived the barriers of taking medication (potential adverse effects to mother and child) to be too great [Reference Champion and Skinner44, Reference Jones, Jensen, Scherr, Brown, Christy and Weaver45]. Patients may benefit from decision aids from providers and community members, step-up treatments if they do relapse, and detailed education regarding the risk and benefit of the pharmacologic interventions.

Cessation medication hesitancy is concerning due to research showing that use of smoking cessation medication doubles quit rates [Reference Etter and Stapleton46]. While small amounts of nicotine from nicotine replacement therapies is transferred to infants during breastfeeding, the amount of nicotine transferred is substantially less than if the parent continued to smoke [36, Reference Sachs, Committee on Drugs and Frattarelli37, Reference Ilett, Hale, Page-Sharp, Kristensen, Kohan and Hackett47, Reference Hickson, Lewis and Campbell48]. In the same vein, bupropion doses are transferred in small amounts to infants via breast milk (reported to be 2% of weight-adjusted maternal dose of bupropion and its active metabolites) [Reference Haas, Kaplan, Barenboim, Jacob and Benowitz49], and the benefit of abstinence from cigarettes vastly outweighs the small risks of taking the medication [50]. Some of the risks of smoking while breastfeeding include disturbed sleep and potential for damage to the liver and lungs [Reference Mennella, Yourshaw and Morgan51, Reference Primo, Ruela, Brotto, Garcia and Lima Ede52]. Additionally, secondhand smoke is associated with asthma, chronic respiratory infections, SIDS, and behavior modeling, as well as a number of other adverse effects on the child [4, Reference Dybing and Sanner10, 53]. It is important to note that the recommendation by LactMed for bupropion in breastfeeding women is “use with caution” [50]. Women need help weighing the known harms of infant smoke exposure versus the harms of short-term medication use [50]. It is possible that relapse prevention treatment would be more acceptable to postpartum women if offered after they begin to struggle maintaining abstinence rather than if offered prophylactically.

While women were supportive of research, few women were interested in signing up for our postpartum relapse prevention study. This finding is consistent with the literature on recruiting pregnant smokers [Reference Park, Quinn and Chang26, Reference Lopez, Simmons, Quinn, Meade, Chirikos and Brandon28, Reference Pollak, Oncken and Lipkus29]. To our knowledge, our study is the first to ask women why they are uninterested in participating in relapse prevention research using medication. Women noted high confidence in remaining quit and low interest in taking medication and concerns about study burden as reasons not to participate. Many were specifically concerned with taking on new commitments postpartum. Participants suggested reducing participant burden with online participation, reduced visit numbers and length, and better compensation. However, even low contact, low burden, studies of postpartum relapse prevention treatments have had difficulty recruiting [Reference Lopez, Simmons, Quinn, Meade, Chirikos and Brandon28]. Thus, it could be that misperceptions about relapse risk coupled with reluctance to make commitments postpartum may be combining to drive poor recruitment success.

This study should be interpreted with limitations in mind. This is a small qualitative study of women in a single state who were mostly White. Their expressed opinions may not be representative of the experience of individuals in other geographic regions or from different racial/ethnic backgrounds. This study was designed primarily to gain insight into the poor recruitment success of the BurPPP trial. The interview guide was developed by the researchers and not informed by a guiding theory or community input, which would have strengthened the scientific rigor of the study. However, our experience is consistent with other studies that have shown difficulty recruiting pregnant and postpartum women into relapse prevention studies [Reference Park, Quinn and Chang26, Reference Lopez, Simmons, Quinn, Meade, Chirikos and Brandon28, Reference Pollak, Oncken and Lipkus29]. Future work should investigate partner perspectives, which are an important factor in postpartum relapse [Reference Orton, Coleman, Coleman-Haynes and Ussher54].

This study serves to add insight to this discourse. It is worth noting that our trial recruitment may have been particularly difficult due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in interviews, most women reported that COVID-19 would not affect their interest in a remotely conducted clinical trial. Finally, our study only asked about interest in bupropion and not other medications for cessation. It may be that women are more willing to take other medications, such as nicotine replacement therapy [Reference Park, Quinn and Chang26]. However, many women in interviews noted a reticence to take medication generally, not just bupropion.

In conclusion, postpartum relapse to cigarette smoking poses significant health risk to women and children but few women believe they will relapse. Barriers to engagement in relapse prevention trials include reluctance to take medication and to take on additional time commitments postpartum. Healthcare systems may be in a position to offer reimbursement for childcare costs or additional parental supports to address concerns about the maternal burden that might come from engaging in smoking cessation activities. Healthcare clinicians are trusted advisors and may be one conduit for promoting engagement in cessation programs by educating about relapse risk vs. medication risk or by helping to catch early relapse behavior and connect patients to treatment. While specific solutions to these issues are beyond the scope of this study, addressing the concerns that these women expressed may be critical to optimizing participation in effective relapse prevention research and programs.

Data Availability

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Disclosure

This paper was previously presented at the 28th Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, March 15-18, 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ashley Petersen and Madison Kahle. This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA047287) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (TL1 TR002493 and UL1 TR002494).

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A: interview guide. This list of questions (created by MAH and JT) guided the conversation with participants during qualitative interviews. (Supplementary Materials)