Introduction

Long-term care services for people with disabilities and frail older people are often provided by non-state organisations in market-type arrangements (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2011). England has had a marketised care system for several decades, characterised by the dominance of for-profit providers and often considered to deliver a narrowly functional model of care (Lewis and West, Reference Lewis and West2014; Rodrigues and Glendinning, Reference Rodrigues and Glendinning2015). The Care Act 2014 aimed to improve care services through a range of approaches, including assigning local government in England a duty to ‘shape’ the care market. Market shaping extended the existing commissioning role of local government to give responsibility to ‘promote the efficient and effective operation of a market in services for meeting care and support needs’, including for people who fund their own care (HM Government, 2014, Section 5 (1)). Market shaping entails:

…[engaging] with stakeholders to develop understanding of supply and demand and…based on evidence, to signal to the market the types of services needed now and in the future to meet them, encourage innovation, investment and continuous improvement (DH, 2017, para 4.7).

In England, this duty is discharged by the 152 local authorities that have social care responsibilities. The market-shaping duty includes a requirement to enable personalised support for people using services and co-production with partners in line with the broader principles of the Care Act (DH, 2017).

In this article we consider how English local authorities are discharging their market shaping duty under the Act. The analysis draws on interview and focus group data from 28 national policy stakeholders and 354 people in eight local sites (commissioners, social workers, providers, people using services, family carers). We identify different types of market shaping, and how local authorities cycle between and combine these types. To do so we utilise grid-group cultural theory, first developed by Mary Douglas (Reference Douglas1970), and adapted for policy and institutional analysis (e.g. Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Ellis and Wildavsky1990; Hood, Reference Hood2000; 6, 2003). The contribution that we offer is threefold. First, we provide the first large-scale empirical analysis of how local authorities are discharging their new market shaping duty. Second, we show the complexity of care markets even within a single locality, in which several different market types co-exist and must be ‘shaped’. Third, we bring to the surface the cultural theories embedded in different approaches to market shaping, based on the rules and relationships between the state and care providers. This theoretical perspective explains why each approach is unstable and hard to combine with another.

The article focuses on England. We see the findings as having broader relevance, as many countries have increasingly marketised care systems (Pavolini and Ranci, Reference Pavolini and Ranci2008; Dickinson et al., Reference Dickinson, Carey, Malbon, Gilchrist, Chand, Kavanagh and Alexander2021) in which state oversight of markets implicitly establishes rule-relationship configurations with providers. Our typology offers a way to map these configurations, understand how they change over time and highlight the inherent tensions between them.

Care as a market

Markets in public services are premised on the assumption that competitive allocation of contracts will provide a diverse and affordable supply of quality services (Considine et al., Reference Considine, O’Sullivan, MCGann and Nguyen2020; Dickinson et al., Reference Dickinson, Carey, Malbon, Gilchrist, Chand, Kavanagh and Alexander2021). In England, this was the basis for the reorientation of social care services from largely state provision in the early 1980s to a now largely outsourced model, with 79 per cent of full-time equivalent social care jobs in the for profit or not for profit sectors (Skills for Care 2020). The National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990 promoted a market of providers, competing for business from local authorities and self-funders (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Hardy and Forder2001; Lewis and West, Reference Lewis and West2014). It is a quasi-market in the sense that the state continues to fund and purchase a majority of social care services, and providers are regulated by the Care Quality Commission (Dearnaley, Reference Dearnaley2013). Some purchasing is done directly by people using services through a direct payment from the state (123,000 people currently hold a direct payment (Kings Fund 360, 2021)); and around 350,000 self-funders purchase their own care because they don’t quality for means-tested state support (Henwood et al., Reference Henwood, Glasby, McKay and Needham2020). These multiple purchasers make for a complex set of demand signals. The Care Act aimed to improve market oversight, and distinctively it gave local government a duty to shape this whole market, rather than focusing only on the care it was purchasing directly.

There are well-known limits to the operation of markets in long-term care including a lack of alignment of supply and demand, and difficulty in measuring outcomes (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Hardy and Forder2001; Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2011; Dickinson et al., Reference Dickinson, Carey, Malbon, Gilchrist, Chand, Kavanagh and Alexander2021). The sustainability and effectiveness of care markets in the UK has further been undermined by cuts to public spending in recent years, despite growing demand, with a 29% cut in local authority spending power since 2010-11 (PAC, 2021, p. 5). The scale of the cuts, at a time of rising demand for care, has created a widespread narrative of ‘crisis’ around care services (e.g. King’s Fund and Nuffield Trust, 2016). Workforce shortages in the sector have created further strain (Skills for Care, 2020) and most localities have reported providers leaving the market (ADASS, 2017). These issues have all been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic (ADASS, 2021). Promised national reform of care funding arrangements to bring more money into the system has yet to be implemented (Glasby et al., Reference Glasby, Zhang, Bennett and Hall2021), creating a sense of stasis within the sector.

It is in this difficult context that local authorities have attempted to become ‘market shapers’, as the Care Act requires. The Act was an ambitious piece of legislation, which aimed to reorient care services away from ‘task-based’ care towards a focus on prevention and wellbeing. It placed a strong emphasis on user choice and control, and co-production between different stakeholders. Making market shaping a legal duty suggests a clearly delimited and legally defensible set of tasks, although a number of commentators have highlighted the lack of clarity regarding what it means to shape a market (IPC, 2015; Dickinson et al., Reference Dickinson, Carey, Malbon, Gilchrist, Chand, Kavanagh and Alexander2021). It can be seen as part of a broader international trend to extend the role of government beyond that of regulator, procurer or commissioner, into ‘market stewardship’ (Gash, Reference Gash2014). Dickinson et al. (Reference Dickinson, Carey, Malbon, Gilchrist, Chand, Kavanagh and Alexander2021) suggest that stewardship necessitates a concern for the diversity and sufficiency of the market. However, who does this and how it is done in particular settings remains ambiguous (Gash, Reference Gash2014; Carey et al., Reference Carey, Dickinson, Malbon and Reeders2018).

Using cultural theory to study care markets

Market-shaping as a set of practices can be understood through the interplay of rules and relationships, drawing on the grid-group cultural theory of Mary Douglas (Reference Douglas1970). Bradbury-Jones et al. (Reference Bradbury-Jones, Taylor and Herber2014) highlight the need to be explicit about when theory entered the study: it was after national policy stakeholder interview analysis that we brought in cultural theory, prior to starting the local case site work. National interviewees drew our attention to two levers through which local authorities were shaping care markets: first, the specification of rules (e.g. in contracts and monitoring), which can be tightly specified or permissive; second, the development of relationships with providers, which can aim to build either close relationships with a small number of providers or weaker relationships with a dispersed set of providers. Rules and/or relationships have been flagged as important dynamics in existing analyses of care markets (e.g. Lewis and West, Reference Lewis and West2014; IPC, 2015; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Miller and Buckingham2017; CLG Committee, 2017), but the patterned interplay between these variables has not been explored.

Having identified these two themes (rules and relationships) in our national data, we considered their interaction using grid-group cultural theory. This theory has been widely used within institutional analysis and public policy to understand patterns of behaviour (Douglas and Wildavsky, Reference Douglas and Wildavsky1983; Wildavsky, Reference Wildavsky1987; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Ellis and Wildavsky1990; Entwistle et al., Reference Entwistle, Guarneros-Meza, Martin and Downe2016; Simmons, Reference Simmons2016, Reference Simmons2018; 6 and Swedlow, Reference Swedlow2016). The grid-group aspect of cultural theory considers how far people’s lives are governed by external rules (the grid dimension) and how far people are part of a loose or tightly bounded social group (the group dimension). From this emerges a two-by-two matrix, typifying four patterns of relations. Hierarchy is high group/high grid, in which a strongly cohered group is governed by strong pre-set rules (e.g. a traditional bureaucracy). Egalitarianism is high group/low grid and describes a strongly cohered group in which rules emerge through partnership and dialogue (e.g. co-productive decision-making arrangements). Individualism (low group/low grid) dominates when there is no strong sense of group and where rules are minimal (e.g. in market-based systems). Fatalism (low group/high grid) describes a setting in which rules are imposed and there is a weak group identity (Hood, Reference Hood2000).

The four part typology can ‘show how cultural patterns are both “internalised” in individuals and “institutionalised” in policy contexts’ (Simmons, Reference Simmons2018, p. 235). As Swedlow explains, ‘the social relations of the four ways of life specified by cultural theory are simultaneously specifications of four ways of making decisions, constituting authority, and exercising power’ (2014, p. 469). For example, hierarchy means ‘the proper authority decides’, individualism means ‘I decide’, fatalism means ‘others decide’ and egalitarianism means ‘we decide’ (2014, pp. 469-70).

We use the four types to understand rule-relationship configurations in English care markets. We focus on engagement between local authorities and care providers since a market shaping strategy is primarily revealed in the way local authorities engage with the provider market (although we recognise that this is a simplifying assumption and there may also be a role for families, communities and other stakeholders). On the grid dimension (which we call rules), local authorities can use contracting and monitoring processes to set down rules in a prescriptive way, leaving providers to follow them; alternatively they can be more flexible, engaging providers as co-producers (e.g. through commissioning for outcomes, Bovaird, Reference Bovaird2014). Entwistle et al. describe a high grid approach as being about ‘the use of hard regulatory instruments and the maintenance of hierarchy’, and a low-grid approach as ‘government having to rely on the soft instruments of diplomacy, partnership and trust’ (2016, p. 899). For the group element (which we call relationships), local authorities can work closely with an ‘in-group’ of preferred providers or can stimulate a dispersed market with weak coordinating factors. Some local authorities, for example, may set up block or framework contracts with a small number of large providers, whereas others may encourage multiple providers to operate and compete on their patch, with more ‘spot purchasing’.

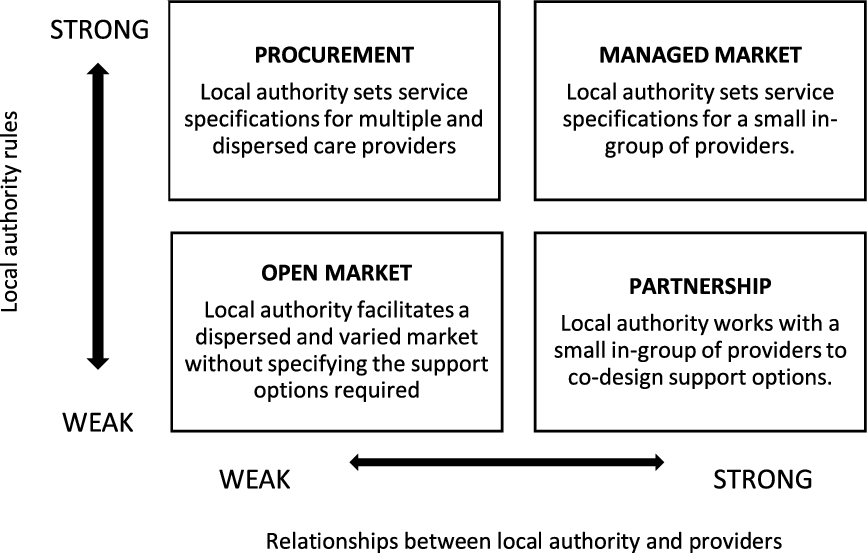

Combining the two variables produces four types of market shaping as shown in Figure 1, which we have given the following labels: procurement (strong rules, weak relationships); managed market (strong rules, strong relationships); open market (weak rules, weak relationships); partnership (weak rules, strong relationships). Of the four, we see the two low rules types as most compatible with the vision of social care set out in the Care Act, given the Act’s promotion of user choice and control (most easily facilitated by the open market approach), and co-production (the partnership approach) (DH, 2017).

FIGURE 1. A typology of care market shaping

Cultural theorists anticipate that any collectivity will have all four types present within it, but that one of the four types is likely to be dominant and institutionalised (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Ellis and Wildavsky1990; Simmons, Reference Simmons2018). There is a competitive element to their co-existence: ‘each culture defines itself by contrast with the others’ (Douglas, Reference Douglas2007, p. 8). Beyond offering a descriptive model, cultural theory also explains how one institutional or cultural type deepens or changes into another through feedback dynamics (6 and Swedlow, Reference Swedlow2016, p. 869). This dynamic analysis of grid-group patterns avoids ‘bird spotting’ studies, which merely identify examples of the four types (Mamadouh, Reference Mamadouh1999, p. 405). It also provides space for agency and fluidity, avoiding the determinism that can be attributed to grid-group categorisation (Logue et al., Reference Logue, Clegg and Gray2016, p. 1591). Through studying the interaction of the four types in local markets it is possible to identify dominant cultures, how they interact with the other types, and how domination changes over time.

Methods

This article draws on findings from a project funded by the National Institute for Health Research, which examined how local authorities were discharging their market shaping duties under the Care Act. Ethical approval for the project was granted by the NHS Research Ethics Committee (17/LO/1729). The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS) also gave approval for the research (RG17-05). The research was undertaken alongside nineteen people with lived experience of using social care services, who worked with the academic researchers to design interview questions, interview participants, and decide practice recommendations.

The first stage of the project focused on understanding the programme theory of market shaping – how it was supposed to work (Needham et al., Reference Needham, Hall, Allen, Burn, Mangan and Henwood2018). Twenty-eight senior leaders of national organisations and opinion formers in the care sector were interviewed during 2017, selected from high profile organisations in care policy (charities, think tanks and membership bodies). In the second stage, we undertook interviews and focus groups in eight local authority case sites to understand how market shaping was working in practice. To develop the sampling frame for local authorities, we used a ‘decision tree’ regression which stratified the 152 local authorities by reported care outcomes and other market-relevant criteria (e.g. type of council, urban/rural and political control). From this we identified a ‘most different’ sample of eight case sites which aimed to reflect the national variance in the sector. Eight sites does not allow us to claim generalizability to English local authorities as a whole. Like other studies using multiple cases, we see it as offering analytical generalizability to theory (Eisenhardt and Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007), in our case to a patterned understanding of market shaping as a set of rules and relationships

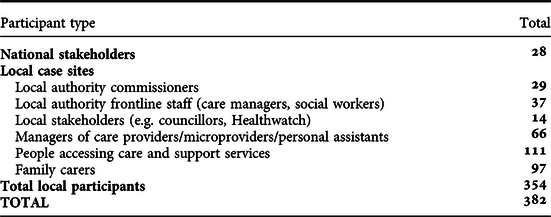

The eight participating local authorities agreed to participate in the research under the condition of anonymity. In these sites, the research team spoke to 354 people during 2018 (see Table 1). There were 257 semi-structured interviews with a range of actors in the local care market including local authority commissioners, care managers and social workers, other local stakeholders (e.g. from health or the voluntary sector), care providers and people using services. Focus groups were conducted with 97 carers. Interview and focus group participants were recruited through snowball sampling, identifying local authority contacts through websites, then using these interviewees to provide contacts to providers, and then asking providers or other local stakeholders to link us to service users and family carers. We checked the sample periodically to ensure that we had participants with experience of a range of care services (e.g. residential and domiciliary care; services for older people and working age adults with disabilities).

TABLE 1. Summary of study participants

Interviews and focus groups were transcribed by an external company and analysed by the research team in QSR-NVivo 11, using a two stage thematic coding process (Attride-Stirling, Reference Attride-Stirling2001). An initial coding frame was developed based on the programme theories that were found to underpin market shaping during an initial realist literature review (see Needham et al., Reference Needham, Hall, Allen, Burn, Mangan and Henwood2018). The grid-group theoretical framework was adopted following this first phase of the research as discussed in the previous section. A second phase of coding was done using a coding frame derived from the grid-group categories. For each site, we looked for indicators of:

-

who was setting market rules (e.g. access to a framework contract) and care specifications?

-

what were the dominant patterns of commissioning/provision (e.g. spot purchasing, block or framework contracts, direct payments)?

-

were local authority commissioners seeking to work with a small or large pool of providers?

-

what mechanisms existed for local authorities and providers to meet and how did these operate?

We used these indicators to make assignments to one of our four grid-group types. We had anticipated doing this at the level of the local authority, but it became clear during the analysis that this needed to be done at a sub-market level (e.g. older people’s residential care, or learning disability direct payments), and this is how we report on it in the findings section below.

Coding was done by five members of the research team through a consensus coding approach (Gibbert and Ruigrok, Reference Gibbert and Ruigrok2010), starting with group coding meetings, and moving to individual coding with regular discussion of coding decisions. Preliminary analyses were shared with local authority commissioners in the case sites to provide a ‘member check’ on our findings and support a peer learning network between the sites (Koelsch, Reference Koelsch2013). In reporting the findings below we draw on anonymized quotes, which captured the experiences of operating within one of the four approaches or of shifting between approaches. Most of the quotes are from local authority managers or providers as they spoke most explicitly about market shaping, although we used data from all of our participants to assign markets to the four categories.

Findings

We had initially expected to be able to assign each local authority to one of the four cultural types. However, rather than matching a whole local authority to a type we found that commissioners were using different approaches to market shaping for different population, such as older people or people using mental health services. Local authority interviewees frequently talked about the difficulties of generalising about their care markets, which militated against a unified approach to market shaping:

It’s very difficult to think across the whole picture, isn’t it? We’ll end up with: market shaping for home care looks like this and your assets-based community shaping looks like that, but it’s so difficult to bring it all together. (Site 4, local authority INT1)

Some of the sites were deliberately distinguishing their market shaping approaches in different sub-markets – for example, pursuing a partnership-type approach with providers of mental health services whilst developing an open market within learning disability support. Others were taking a less purposeful or explicit approach and simply had in place a number of different approaches to market shaping in different services.

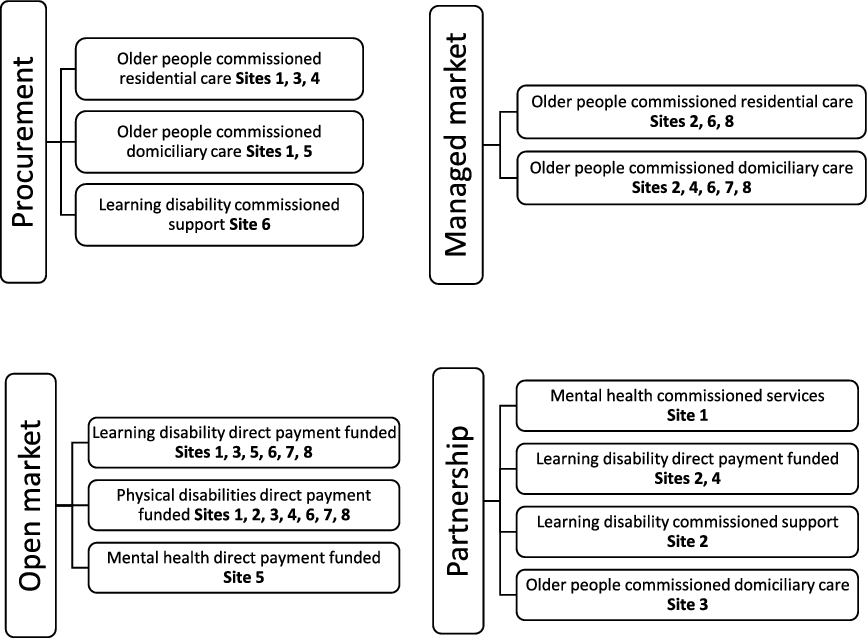

Figure 2 shows the allocation of market types within the eight local authorities, using service labels such as domiciliary and residential care, and service user categories such as older people, learning disability and mental health, which are common within adult social care (whilst acknowledging that these labels are artificial and can be misleading, SCIE, 2004). Commissioned services are those purchased by the local authority. Direct payment services are those where the local authority allocates the funding to the care user to make a purchase. The figure only shows those parts of the markets where we had sufficient data to make an allocation. We gained most information about older people’s services and least about mental health services, where the overlap with health further complicates market shaping (Carr, Reference Carr2018). Self-funders are not included in the analysis: we found that they remained peripheral to local authority market shaping, despite the intentions of the Care Act (Henwood et al., Reference Henwood, Glasby, McKay and Needham2020).

FIGURE 2. Allocation of sub-markets to types of market shaping

The procurement approach was found in five of the sites, and was most prevalent within older people’s residential and domiciliary care markets. Here a dispersed market of providers was operating, with the local authority setting tight contract specifications. There was limited local authority engagement and collaboration with providers, and user choice of services was limited. In the managed market approach, found in five sites, local authorities maintained a high level of control over the social care market and developed close relationships with a small number of providers (e.g. through block or framework contracts). This was most common in domiciliary care markets. In the open market approach the local authority facilitates interaction between providers and service users, but does not set strong controls on market entry or user choice. Elements of this model were found in all sites for people receiving direct payments, who had a range of provider options, including personal assistants (PAs). In the partnership approach, close relationships are developed between local authorities and providers to co-design and develop service provision, in dialogue with communities. Elements of this model were found in four sites, which were taking a strategic and more outcomes-oriented approach to parts of their market.

The type of service was the best predictor of which quadrant services were assigned to. Older people’s services were particularly likely to be in the top half of the quadrant (strong rules), whereas services for working age people were in the lower quadrant (weak rules). We found a lack of ambition around older people’s services which is in line with existing literature (Lewis and West, Reference Lewis and West2014; King’s Fund and Nuffield Trust, 2016), as these quotes from commissioners indicate:

Older people’s care home market is like the one where… I wouldn’t say we’ve got no plans around it but we haven’t got any bespoke plans around how we deal with that market. (Site 1, local authority INT1)

[T]he issues around an individual employing a PA, for example, is just too difficult to manage. Especially for an older person. (Site 8, local authority INT4)

The following four sections look in more detail at procurement, managed market, open market and partnership.

Procurement – strong rules, weak relationships

Exemplar type – spot purchasing

In the procurement approach, the market shaping strategy is to combine tight local authority control with a dispersed market of providers who bid for contracts. Commissioners in local authorities develop service specifications and invite providers to supply services. The use of spot contracts and dynamic purchasing systems were examples of this approach, with an emphasis on what is sometimes called ‘time and task’ contracting (Lewis and West, Reference Lewis and West2014).

The rationale for using this kind of procurement approach varied. In some local authorities it was seen as the best way to get competitively priced care in a just-in-time way – adhering to minimum care standards and stringent budget constraints whilst also satisfying the requirements of procurement law. Value for money was particularly important, as this local authority interviewee indicated:

My understanding of market shaping is that it’s almost encouraging providers to be more competitive in terms of could they provide more value for money in care? (Site 1, local authority INT5)

Care providers saw this approach as being driven by short-termism and paternalism within local authorities, which inhibited effective relationships and planning: ‘They make all the decisions before they enter into any kind of consultation with providers’ (Site 3, provider INT1). It was seen as antithetical to the principles of the Care Act, with no incentive to innovate. The emphasis is on matching supply to demand as determined by the local authority; there is little scope for the specification or resultant services to incorporate provider co-design or user choice and control.

Managed market – strong rules, strong relationships

Exemplar type - block contract

The managed market approach aims to secure sufficiency of supply through the use of block or framework contracts with a small number of providers. It appears to mark the next phase of evolution in local authority market shaping approaches after procurement: five of the eight local authority case sites had moved some of their sub-markets away from procurement-driven approaches to take a managed market approach.

This approach was seen by local authority commissioners as offering advantages to the local authority, providers and service users, stabilising the market and facilitating rapid placements when people needed care. In some sites, this had been done across a whole local authority patch. For example, one of the local authorities in our study had addressed delayed hospital discharge by block contracting with three providers specifically to do home reablement work with people after a hospital stay. In others it was being done through a neighbourhood approach, in which providers were given guaranteed hours within small areas – a lead provider was appointed for an area who could sub-contract with other providers in a more flexible way.

Commissioners had opted for a managed market approach to stabilise and ensure sufficiency of supply. However, the approach had largely failed to do this in the five local authorities that were using it: issues of undersupply of staff or provider withdrawal meant that block and framework contracting did not deliver the anticipated market stability. As one commissioner put it:

The intention was to try and take a stronger approach of shaping the market, by contracting people, agencies, rather than just doing spot purchases for people all the time. But trying to take that control back hasn’t worked out as well as hoped. (Site 7, local authority INT4)

In this case, the attempt to establish a lead and sub provider model had fallen through when both lead providers handed back their contracts due to difficulties recruiting staff. Providers also expressed concern about how this approach to commissioning was impacting on choice and control for people using services:

The way they commission that service is in geographical lots, so they will…commission 5,000 hours of domiciliary care for [an area]…The challenge really to the local authority…is to say, “Well, where is the choice there? That customer has no choice, you decide and that’s a given”. (Site 2, provider INT1)

The guaranteeing of hours to providers, at the same time as purposefully shrinking the number of commissioned services, appeared to prioritise stability over user choice.

Open market – weak rules, weak relationships

Exemplar type - Direct payments

In the open market approach, local authorities stimulate a diverse market of providers with relatively weak market oversight. Purchasing may be done by the person using the service, through a direct payment or another kind of individualised funding model (for example, as a self-funder). All the local authorities in our study were adopting some elements of an open market approach through enabling direct payments. The open market approach requires local authorities to let relationships develop bilaterally between users and providers. As a provider put it:

Local authorities have to get out of the way and allow providers and service users to develop the relationships between them…[T]heir role simply needs to be, “Is everything proceeding as it should be? Is the customer happy, healthy? In that case, that’s all we need to know.” (Site 2, provider INT3)

However, this requirement to ‘get out of the way’ was something that many local authority commissioners struggled with:

We’re still very much in the mind-set that we’re the parent: we know all the services, we know what are the best ones, and we are the judges of quality…. (Site 8, local authority INT2)

Paradoxically, some local authorities appeared to be getting too far out of the way. Interviewees with direct payments reported positive experiences of being able to choose their own care, but wanted more local authority support and facilitation than they were currently getting. Users and carers were often left to find providers through word of mouth, and once arrangements were in place they were rarely reviewed. Personal assistants reported feeling isolated, with a lack of formal structures to match them to the people needing support:

You’re left to struggle on your own. That’s the only downside…Gumtree, I’ve used the Job Centre. Word of mouth, yeah. Advertising in shops, newsagents, that kind of thing. (Site 1, personal assistant INT2)

Family carers spoke of the difficulties of operationalising choice where they were only given a list of providers – or told to look online. The open market was found to be particularly difficult to navigate for interviewees for whom English was a second language, especially if they were not able to access online resources.

Partnership – weak rules, strong relationships

Exemplar type - outcomes-based commissioning

In this approach, local authorities work with a small number of providers to co-design services or commission for outcomes and leave providers to develop appropriate support models with users. This approach gives primacy to the long-term stability of the market, an appropriate service mix, and the harnessing of provider expertise in service design. In all eight of our sites we found that this was the model that local authority interviewees aspired to move towards, feeling that it was consistent with the Care Act and likely to offer stability, quality and affordability. User choice of provider is limited in the partnership approach, given that it aims at slimming the market – although some areas were bringing users and families into a co-design process with providers and commissioners to jointly agree outcomes.

Slimming down the market and taking a more long-term approach was welcomed by some providers:

There used to be 30 odd but there’s nine main providers in [our area] now. So, that gives you the economy of scale…which is good. And it’s a 10-year framework … it allows you to put some real roots down. (Site 4, provider INT3)

However, a number of local authority commissioners reported slow progress in moving in this direction, which some attributed to a lack of appetite for new ways of working amongst providers:

I think if I was to go and do a tender and say that I want an outcome-based contract, [the providers] would have absolutely no idea what I’m talking about or where I’m starting from. (Site 7, local authority INT2)

The partnership approach requires high levels of trust between commissioners and providers, and a willingness to co-design for the long-term. On the whole, we found low levels of trust between commissioners and providers in all our sites:

Fundamentally it’s trust… Particularly financially if we’re saying ‘yes we’ll give you that pot of money for that group of customers, here’s x per year, just meet all their needs, we trust you to do that’, but we don’t…. We want to measure it. We don’t quite trust that those outcomes will be met for that money unless we can see what’s been delivered minute by minute. (Site 8, Local authority INT4)

From the provider perspective, a key barrier to trust was the high turnover of local authority staff which inhibits communication and relationship building. There was also a plea from providers for outcomes-based approaches to be based on learning and adaptation, recognising that in complex systems it can be difficult to attribute outcomes (Bovaird, Reference Bovaird2014).

Mixed models, cycling and hybridity

As discussed above, rather than each site exclusively deploying one of the four approaches, we found that typically they were pursuing several types of market shaping simultaneously. This was patterned, differing by service user groups and types of services in the locality, and changing over time. Some of the local authority interviewees talked us through the evolution of their market engagement which mapped onto changing national policy priorities over two decades (rather than starting with the Care Act). A procurement approach was largely adopted by local authorities following community care reforms of the 1990s. A move to the managed market approach was evident in the introduction of commissioning in the early 2000s (CLG, 2006). The Putting People First concordat (HM Government, 2007) triggered a push towards personalisation and open market approaches, later followed by the Care Act 2014’s emphasis on co-production, prevention and wellbeing which links to the more long-term, high trust approaches of the partnership model.

Our data suggests that the shift between models may also be a response to the limitations of each type in the context of the broader pressures on the care system. Swedlow (Reference Swedlow2014, p. 470) argues that change will occur if people adhering to certain cultural values and behaviours do not get properly rewarded and therefore lose their commitment to that cultural form. As Mamadouh (Reference Mamadouh1999, p. 397) puts it, ʼthe cumulative impact of successive anomalies or surprises… provoke a change of paradigm’. We can argue that this is the driver of change in market shaping, as perceived failings in dominant cultural forms (e.g. to stabilise the care market or offer sufficient diversity) has led to ‘punctuated equilibrium’ with one form giving way to another (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Ellis and Wildavsky1990; Hood, Reference Hood2000: 70; 6 and Swedlow, Reference Swedlow2016).

However, this evolutionary metaphor suggests a linear progression, whereas we also found cyclical patterns in our data. In his work on cultural theory, Hood notes that ‘any one of the polar approaches discussed here might be expected to regenerate…however confidently they might have been consigned to the “dustbin of history”’ (Reference Hood2000, p. 70). Several of our interviewees reflected on a timeline of change in which they had moved some sub-markets to an open market approach around 10 years ago and had subsequently gone back to the managed market to regain greater control. One local authority interviewee described the rationale for retreating from the open market:

Everyone jumped on choice means more… more provision and more providers and you got all these organisations set up to kind of hit that…Actually, it diluted a market and… I think it’s created unsustainable business models at the moment actually. So, we’re looking to kind of reverse that a little bit. (Site 1, local authority INT1)

As well as taking different approaches in different services, and cycling over time, some sites were engaged in hybrid approaches, in which they attempted to utilise more than one of the models in the same market at the same time. For example, in domiciliary care, one of our sites was working with established providers through a managed market approach whilst also stimulating an open market with micro-enterprise and personal assistant provision. They hoped as a result of this to be able to combine market diversity with market stability. Hybrid forms are well known in institutional theory and can work well under certain conditions (Skelcher and Smith, Reference Skelcher and Smith2015). However cultural theory offers a way to see why hybrids within a single sub-market are likely to be unstable due to the rivalry between the different underlying theories (Hood, Reference Hood2000; 6, 2003; Douglas, Reference Douglas2007). This was indeed what we found: where different providers were being offered a different rule/relationship configuration in the same market this was creating tension because of a perception of double standards. As one provider put it:

The reaction from the traditional service providers has been very mixed…One of the fears for providers is that it’s an attempt to kind of dismantle the current structure of the market and give people more choice. In so doing, undercutting traditional providers because micro-providers aren’t subject to the same regulatory control, so their costs are lower. [Site 5, provider 1.]

Hence, whilst some commissioners hoped for a hybrid as the ‘best of both worlds’, the uneasy combination of cultural biases made it a fragile configuration.

Discussion

Our aim in this article has been to develop an understanding of how local authorities are discharging their market shaping duty under the Care Act 2014. Whilst care markets are not new, the directive to ‘shape’ care markets is a relatively new and under-studied duty. We have used grid-group cultural theory to develop a typology of market shaping based on rules and relationships, exploring how local market shaping practices fit the typology. The typology positions market shaping as a feature of the patterned interaction between local authorities and providers, and in particular the setting of rules and the development of relationships by local authorities, which can be combined into a two by two matrix.

All of the sites in our study were combining quadrants, as well as moving between them over time. The Care Act directs local authorities towards the ‘weak rules’ half of the typology in its promotion of user choice and control (the open market) and co-production (partnership). However, these approaches require local authorities to cede considerable amounts of power, and we found the perceived risks of ceding this power generated countervailing forces pulling commissioners towards the ‘strong rules’ half of the typology. This was particularly the case for older people’ services, where our findings supported existing literature in finding a lack of ambition and retention of time and task-based models (Lewis and West, Reference Lewis and West2014; King’s Fund and Nuffield Trust, 2016).

The article makes three contributions to the extant literature. First, we show the complexity of care markets, in which several types of market co-exist even within a single locality. Existing characterisations of care markets have been at a national level (e.g. Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2011) or by sector (e.g. the care home market (Forder and Allan, Reference Forder and Allan2014)), but this misses the extent to which localities have different markets for different population groups and service types. Our fieldwork – in which local respondents often asked us to clarify ‘which market’ we were asking about – draws attention to the complexity of care market shaping, in which local authorities are working across several markets simultaneously.

Second, we provide the first large-scale empirical analysis of how local authorities are discharging their new market shaping duty. This brings a much fuller understanding of market shaping, building on the practice-focused literature which has so far dominated in this field (e.g. IPC, 2015; Bolton, Reference Bolton2019). We highlight continuity with earlier forms of commissioning prior to the Care Act, and also the tendency of local authorities to cycle through different approaches. Considine et al.’s (Reference Considine, O’Sullivan, MCGann and Nguyen2020) work on employment markets shows how provider promises of personalisation evaporate when risks are high, with standardisation seen as a way to minimise risk. This is similarly evident in the way that local authorities are interacting with providers over a period of high risk within the care system, with a move back from approaches that foster individual choice and provider innovation.

Third, we surface the different cultural theories embedded in different approaches to market shaping. This gives a patterned understanding of market shaping as a set of rules and relationships. Using cultural theory explains the types of market shaping, the tendency to cycle between approaches over time and the instability of hybrid models. External pressures on the care system – including a lack of funding and workforce shortages – mean that the expected rewards from a particular rule-relationship configuration are not being realised, creating pressure to pursue new configurations (Swedlow, Reference Swedlow2014). To achieve the goals of the Care Act, commissioners are expected to shape their markets in ways that promote both fluid open markets and stable long-term relationships. However rival cultural biases mean that hybrid models antagonise providers and risk further unsettling an unstable market.

Improving social care provision is an urgent imperative for local and national policy-makers. Simmons has highlighted how cultural theory can help practitioners in their ‘institution work’ (Reference Simmons2018, p. 235), providing both a ‘map’ to reflect on where they are and an ‘internal compass’ about the ‘rightness’ of their approach. In a care context, an awareness of their current configuration of rules and relationships could allow local commissioners and providers to reflect on their cultural biases and to consider alternatives. As Rayner puts it, ‘What grid and group can do is demonstrate the route by which…changes occur and indicate what kinds of strategies are available to the inhabitants of any particular social environment in their search for another’ (Rayner, Reference Rayner1979, p. 68).

Conclusion

Care markets have existed for several decades and have been subject to critique for failing to deliver high quality and appropriate services for people who rely on them. The Care Act 2014 aimed to improve local authority oversight of care markets and to extend the commissioning role to give them broad responsibility for shaping the care market. This article has taken forward our understanding of market shaping, by utilising cultural theory to surface the rule-relationship configurations that underpin the interactions of local authorities and providers. It explains how the Care Act’s ambition of moving to ‘weak rules’ approaches has been of limited effectiveness.

The data presented here are from a large qualitative data set, drawn from national interviewees and eight local authorities. Although our data is extensive, we acknowledge that there may be limits to the extent to which our participants were typical of people working in or using care services. People who agreed to be interviewed may be those who are most able and motivated to talk about their experiences, and may not represent the broader care population. Two of our original eight local authority case sites dropped out and had to be replaced, and although we retained the balance of sampling characteristics, we recognise that the participating sites may be atypical in being open to research about their market shaping activities.

It is important to note also that there are many other stakeholders in the care system, beyond the local authority-provider nexus discussed here. Local authorities are involved in relationships with communities and people using services (including self-funders), as well as national government, health commissioners and regulators. These stakeholders may have a bearing on which rule-relationship configuration becomes dominant in a locality. Future work could look for patterns in which cultural type is preferred by different groups. For example, health commissioners may prefer the high-control managed market arrangements if these are the ones most likely to expedite hospital discharge. Although our fieldwork was conducted prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, its disruptive effects on health and care systems are a further destabilising factor which may incline commissioners towards strong rules approaches, and this merits further attention.

There are clear differences between care markets in different countries which inhibit the transferability of our findings to different settings. Nonetheless, as Hood (Reference Hood2000) argues, the advantage of grid-group theory is its applicability to a range of institutional contexts. It offers scope to compare local rule-relationship configurations across a range of countries. Future research of this type would take us beyond comparisons of care systems at the national level, into a recognition that local care systems are patterned and comparable.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme (PR-R14-1215- 21004 Shifting-Shapes: How can local care markets support quality and choice for all? and PR-ST-1116-10001 Shaping Personalised Outcomes - How is the Care Act promoting the personalisation of care and support?). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.