Introduction

Laser wakefield acceleration (LWFA) (Ref. Reference Tajima and Dawson1) is a specific technique within the broader category of laser-plasma accelerators (LPAs), which themselves are a subset of plasma-based accelerators (PBAs). In LWFA, an intense, ultrashort laser pulse propagates through an underdense plasma, creating a plasma wave- or “wakefield”-behind it. This wakefield possesses electric fields that can be several orders of magnitude stronger than those in conventional accelerators, enabling the acceleration of electrons to high energies over very short distances. Despite these advantages, LPAs face challenges related to beam stability and quality, which currently hinder their ability to fully replace traditional RF systems. A critical factor in overcoming these challenges lies in the plasma source itself: the creation of stable, uniform plasma channels is essential for sustaining high-gradient wakefields and achieving high-quality beam acceleration.

Among the various solutions, gas-filled plasma capillaries provide a flexible approach, allowing fine control over plasma properties. To characterize and optimize these plasma conditions, plasma spectroscopy plays a fundamental role. By analysing spectral line emissions, it is possible to extract key parameters such as electron density and temperature along the capillary axis (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler2). These diagnostics inform the capillary design and ensure plasma uniformity, directly supporting stable and high-quality LWFA experiments. The strategies and diagnostics described above are closely aligned with the objectives of the I-LUCE (INFN-Laser indUCEd Radiation Production) facility (Refs Reference Cirrone, Amato, Bandieramonte, Bonanno, Cantone, Catalano, Cuttone, Maggiore, Miraglia, Musumeci and Passarello3, Reference Cirrone, Arjmand, Sciuto, Fattori, Pappalardo, Catalano, Cuttone, Oliva, Petringa and Tramontana4, Reference Arjmand, Amato, Catalano, Cuttone, Manna, Oliva, Pappalardo, Petringa, Suarez, Vinciguerra and Cirrone5), currently under development at the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare - Laboratori Nazionali del Sud (INFN-LNS) in Catania, Italy. I-LUCE will provide a dedicated platform for investigating high-power laser-plasma interactions. The facility will feature a high-power laser system capable of accelerating electron beams from the MeV to GeV scale, using either a 460 TW, 23 fs, 2.5 Hz laser or a 45 TW, 23 fs, 10 Hz laser. Gas-filled plasma capillaries will be employed to create tailored plasma channels for LWFA, enabling stable and efficient beam generation to support advances in very high-energy electron beam (VHEE) applications (Refs Reference Arjmand, Amato, Catalano, Cuttone, Manna, Oliva, Pappalardo, Petringa, Suarez, Vinciguerra and Cirrone5, Reference Labate, Palla, Panetta, Avella, Baffigi, Brandi, Di Martino, Fulgentini, Giulietti, Köster and Terzani6, Reference Whitmore, Mackay, van Herk, Jones and Jones7, Reference Arjmand, Amato, Catalano, Manna, Mascali, Mauro, Oliva, Pappalardo, Suarez and Vinciguerra8).

Radiation in discharge plasmas

Radiation in discharge plasmas originates from various dominant emission mechanisms that result from interactions between charged particles (electrons, ions) and neutral atoms. The emitted radiation spans from the ultraviolet (UV) to the infrared (IR) range and includes both continuum and line emission for low-temperature and high-temperature plasmas. The primary mechanisms of radiation in such plasmas include:

• Line Radiation (Bound-Bound Transitions):

Occurs when electrons move between specific energy levels in atoms or ions, releasing photons at characteristic wavelengths. In low-temperature, partially ionized plasmas, where atoms or ions are still in the bound state, this is the dominant form of radiation. For example, in hydrogen plasmas, the Balmer series spectral lines, especially

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$ and

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$ and  $\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ are prominent.

$\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ are prominent.• Bremsstrahlung Radiation (Free-Free Transitions):

Occurs when charged particles, mainly free electrons, are decelerated or deflected by the electric fields of other charged particles (ions) in the plasma. This interaction results in the emission of electromagnetic radiation. The intensity of bremsstrahlung radiation depends on both the electron temperature and the plasma density. Although it is most prominent in high-temperature, high-density plasmas-particularly those that are fully ionized with energetic electrons in high-pressure gases (e.g. arcs, fusion).

• Recombination Radiation (Free-Bound Transitions):

Occurs when free electrons recombine with ions, forming neutral atoms. The energy released during this process manifests as photons, with energy corresponding to the difference between the electron’s kinetic energy and the ion’s binding energy. Recombination radiation becomes significant in moderately ionized plasmas, such as in high-pressure arcs or certain laser-produced plasmas, where recombination events are more frequent.

Each of these mechanisms contributes to the overall radiative behaviour of discharge plasmas. Among them, line emission is central to this work, serving as the primary diagnostic tool. By analysing the spectral lines it produces, critical plasma parameters such as electron density, electron temperature, and ionization states can be accurately determined. This is particularly important for plasma diagnostics in LPA applications via LWFA, where precise control of plasma conditions is essential.

Spectroscopic diagnostic

Accurate diagnostics of discharge plasmas are essential for understanding and controlling their properties. Depending on the plasma conditions and expected electron densities, various methods can be applied, such as interferometric methods, mechanical probes (Langmuir), and different spectroscopic methods (absorption, emission, scattering, etc.). This is particularly important in compact configurations, where the plasma may be confined to dimensions of approximately 2 mm to 100 µm, or in optically thin plasmas. In such cases, mechanical probes are impractical, as they can disturb local plasma conditions. Instead, non-intrusive, real-time diagnostic techniques are required to provide reliable information without affecting the plasma.

Among spectroscopic techniques, optical emission spectroscopy (OES) stands out as one of the most effective non-contact methods for diagnosing discharge plasmas. By analysing the light emitted from excited atoms and ions, OES enables the measurement of key plasma parameters such as electron density, electron temperature, and ionization degree. It also allows identification of the species present in the discharge through their unique spectral signatures. Due to its non-intrusive nature, OES is particularly advantageous in scenarios where maintaining plasma integrity is crucial, such as in compact or optically thin plasmas. OES is typically implemented using either spectrometers or monochromators. Spectrometers provide the full emission spectrum, supporting broad analysis and species identification. Monochromators, equipped with diffraction gratings, isolate individual wavelengths for detailed study of specific spectral lines. In both approaches, accurate calibration is essential to ensure precise and reliable diagnostics.

Time-resolved imaging spectroscopy

Various diagnostic techniques are used in the OES and plasma analysis, each for specific measurement goals. These include time-resolved spectroscopy with intensified charge-coupled device (ICCD) detectors for transient phenomena, fibre-optic and slit-scanning spectroscopy for spatial-spectral mapping, and monochromatic imaging for specific emission lines. Time-resolved imaging spectroscopy is particularly valuable for capturing both spatial and spectral information simultaneously, ideal for studying dynamic behaviours and non-uniformities in plasmas.

For reliable spectral measurements, imaging spectrographs require precise wavelength calibration. This calibration ensures that the recorded spectra are accurately mapped to their corresponding wavelengths, which is essential for identifying emission lines and extracting quantitative plasma parameters such as electron density and temperature.

Calibration methods include using spectral lamps, monochromators, tunable lasers, or gas cells. While monochromators and tunable lasers are more complex and costly, spectral lamps provide a simpler solution, covering a broad range such as the visible spectrum. Wavelength calibration is essential for ensuring the alignment of a spectrometer’s spectral response with known reference wavelengths, minimizing errors. Continuous evaluation of calibration performance is crucial for high-precision applications like laser-plasma interaction studies and time-resolved diagnostics, ensuring sustained accuracy over time. Even slight deviations in the relationship between spectral pixel indices and wavelengths can significantly impact spectral interpretation. Although many instruments show an approximate linear relationship, deviations may occur because of instrumental imperfections or optical aberrations.

A key component in spectrometers, the diffraction grating, disperses light by causing constructive interference at specific angles, as described by the grating equation (Ref. Reference Palmer and Loewen9):

where m: diffraction order, λ: wavelength of the light, d: spacing between the grating grooves, α: incident angle (the angle at which light strikes the grating), β: diffraction angle (the angle at which light is dispersed and detected).

The relationship between the diffraction angle β and the wavelength λ is generally small and is often approximated as linear. However, this relationship is not strictly linear. By solving the grating equation for ![]() $\beta(\lambda)$, the diffraction angle is given by (Ref. Reference Henriksen, Sigernes and Johansen10):

$\beta(\lambda)$, the diffraction angle is given by (Ref. Reference Henriksen, Sigernes and Johansen10):

\begin{equation}

\beta(\lambda) = arcsin \

(\frac{m\lambda}{d} - sin\alpha).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\beta(\lambda) = arcsin \

(\frac{m\lambda}{d} - sin\alpha).

\end{equation}The relationship is approximately linear near zero, though deviations from perfect linearity may arise. These deviations are primarily caused by misalignments in the grating and optical aberrations in the lenses, which can alter the diffraction angles.

Spectroscopic system setup

The spectroscopic system used in this study includes a spectrograph, detector, light source, and auxiliary optics. Princeton Instruments (PI) SpectraPro HRS-300, optimized for the visible wavelength range (approximately 400–700 nm), was used for spectral analysis. Its specifications are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Specification of the SpectraPro HRS-300 PI spectrograph

The spectrograph system incorporates interchangeable grating turrets to accommodate various spectral applications. It also features the IntelliCal wavelength calibration light source, a compact, USB-powered unit that combines mercury (Hg) and neon-argon (Ne-Ar) emission lamps within a single housing. These lamps emit stable and well-characterized spectral lines, facilitating precise and repeatable calibration. The IntelliCal unit can be mounted directly to the spectrograph’s entrance slit for routine calibration or repositioned for in situ alignment checks, thereby minimizing experimental downtime. A front-panel toggle switch allows for quick lamp selection, and an accompanying emission-line reference chart ensures traceable wavelength validation, essential for resolving sub-nanometre spectral features. The spectrograph separates the incoming light into different wavelengths, which are recorded using an Andor iStar DH320T Gen 3 time-resolved image intensifier connected to an ICCD camera. The ICCD detector features a ![]() $1024 \times 255$ pixel matrix with an effective pixel size of

$1024 \times 255$ pixel matrix with an effective pixel size of ![]() $26\times 26\ \mu\mathrm{m}$, providing high spatial and spectral resolution.

$26\times 26\ \mu\mathrm{m}$, providing high spatial and spectral resolution.

This configuration enables both time-resolved measurements (with a minimum gate width of 2 ns) and precise spectral sampling, which is critical for capturing transient phenomena such as laser-induced plasmas or fluorescence decay.

The spectrograph incorporates three interchangeable gratings, each optimized for specific resolution and wavelength coverage. While the detector theoretical range spans 0-1500 nm, practical operation is constrained by factors such as grating efficiency, optical component transmission, slit aperture geometry, and the ICCD’s quantum efficiency.

High-resolution configurations utilize a 1200 grooves/mm (g/mm) grating, providing a 60 nm spectral window per acquisition, or a 2400 g/mm grating, yielding a 30 nm window. The 1024 horizontal pixels of the ICCD, combined with the 26 µm pixel pitch, translate to a spectral sampling density of ∼0.06 nm/pixel for the 1200 g/mm grating. This ensures fine resolution of narrow spectral features, while the 2400 g/mm grating further enhances resolving power, ideal for applications such as Raman spectroscopy or resolving atomic emission lines. The inverse relationship between groove density and spectral coverage highlights the adaptability, balance resolution, and range of the system for targeted experimental needs.

Data acquisition

To ensure accurate wavelength calibration within the 400–700 nm range, we used emission lines from mercury (Hg: 400–580 nm) and neon-argon (Ne-Ar: 580–700 nm) lamps, chosen for their distinct and stable lines. The IntelliCal light source, integrating both lamps mounted directly to the entrance slit, facilitated the calibration. During the calibration process, the spectrometer was configured with a 1200 g/mm diffraction grating, operating in the first diffraction order (m = 1). The light source was positioned in front of the spectrometer’s entrance slit, and each lamp – either a Hg or Ne-Ar lamp – was illuminated sequentially to collect spectral images. The exposure time for each lamp was adjusted to ensure an adequate signal without causing overexposure. It varied according to the intensity of the light emitted by each lamp. The Ne-Ar lamp, which typically emits more intense lines, required shorter exposure times to avoid saturation, whereas the Hg lamp, with less intensity, necessitated longer exposure times for optimal image capture. An example of a detected spectral frame is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. An example of detected spectral frame showing Ne-Ar emission lines in the 620–660 nm range.

Identifying spectral lines

The spectrometer was set up with a 1200 g/mm grating to achieve high spectral resolution across the 400–710 nm visible range, using both Hg (blue colour) and Ne-Ar (red colour) lamps. Figure 2 shows the overlaid spectra of this range.

Figure 2. Overlaid spectra from five intervals covering 400–710 nm.

However, to do this, the full range was divided into five separate intervals, each spanning 60 nm, because of the spectrometer’s limited spectral window per acquisition. For each interval, the spectrometer was calibrated by setting the central wavelength near the midpoint of the target lines. This approach allowed for the observation of two to six emission lines per interval, depending on the lamp used.

The number and distribution of lines varied by lamp type. The Hg lamp, with relatively few lines, typically exhibited two to three lines per 60 nm window. In contrast, the Ne-Ar lamp produced a denser distribution, especially in the red and near-infrared regions, enabling up to six lines per interval. To optimize spectral coverage, the wavelength intervals were centred on the densest groupings of lines within each lamp emission range. The measured emission lines were identified and verified using reference values from the NIST database (Ref. 11), confirming both line identification and wavelength calibration. Figure 3 displays the recorded spectra from five intervals, highlighting variations in line density between sources: blue for Hg and red for Ne-Ar.

Figure 3. Observed spectrum of calibration lamps, including Hg (blue) and Ar-Ne (red) from 5 intervals, showing the line output.

To evaluate the accuracy of the wavelength calibration, two complementary analyses were conducted: a point-by-point deviation assessment and a statistical error quantification. Each measured wavelength was compared with its corresponding reference value, and the deviations are illustrated in Figure 4. As shown, almost 50% of the deviations fall within the range of ±0.1–0.5 nm, indicating a reasonable calibration accuracy which for precise spectroscopy (e.g. Stark broadening, Doppler shift) the acceptable deviation must be ![]() $ \lt \pm$0.2–0.5 nm.

$ \lt \pm$0.2–0.5 nm.

Figure 4. Deviation between known and measured wavelengths in Table 2.

To quantitatively assess the overall calibration quality, the mean absolute error (MAE) was computed:

\begin{equation}

\overline{\Delta \lambda} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} |\Delta \lambda_{i}|,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\overline{\Delta \lambda} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} |\Delta \lambda_{i}|,

\end{equation} where N is the total number of emission lines used in the calibration, and ![]() $\Delta \lambda_{i}$ is the difference between the measured and reference wavelengths for the ith emission line. The calibration quality can be assessed on the basis of the MAE:

$\Delta \lambda_{i}$ is the difference between the measured and reference wavelengths for the ith emission line. The calibration quality can be assessed on the basis of the MAE:

• MAE ≤ 0.5 nm: high accuracy, sufficient for most spectroscopic applications,

• MAE ≥ 1 nm: potential systematic errors that require correction or higher order fitting.

The measured MAE of ≈0.5 nm indicates a high calibration accuracy. The remaining error likely stems from the employing of multiple separate spectral intervals, which can introduce inconsistencies due to varying sampling intervals. However, for studies focused on specific spectral lines, particularly the characterization of hydrogen plasma via the Hα or Hβ lines, a more targeted calibration approach is feasible. By focusing on a specific spectral region and employing a single calibration interval, the accuracy can be enhanced, potentially reducing the MAE. In summary, while the current calibration provides good accuracy with minor deviations, adopting a localized calibration strategy for the spectral region of interest could further improve precision.

Pixel-to-wavelength mapping

After identifying emission lines in the captured spectra and recording their corresponding pixel positions on the detector, we established a precise wavelength calibration. Figure 5 presents the five spectral intervals with their corresponding pixel positions.

Figure 5. Raw spectral data from 5 intervals showing identified emission lines (Figure 3) and their corresponding pixel positions. (a) Interval 1, (b) Interval 2, (c) Interval 3, (d) Interval 4, (e) Interval 5.

This pixel-to-wavelength mapping process involved establishing a linear relationship between pixel positions and wavelengths using known reference lines. For each interval, we model the wavelength λ as a function of the position of the pixels p:

where S is the dispersion coefficient or slope (wavelength change per pixel), and b is the intercept (wavelength at pixel zero). The mapping approach varied by interval based on the number of identifiable emission lines:

• Intervals 2 and 5 contained only one identifiable emission line, making linear regression impossible; these were excluded from calibration,

• Intervals with two reference lines used direct linear interpolation:

$ S = \frac{\lambda_2 - \lambda_1}{p_2 - p_1}$,

$ S = \frac{\lambda_2 - \lambda_1}{p_2 - p_1}$,• Intervals with more than two lines employed least-squares regression to account for potential nonlinearities.

Figure 6 demonstrates this piecewise mapping approach, showing linear fits for intervals 1, 3, and 4. The variation in slopes across intervals (ranging from 0.037 to 0.193 nm/pixel) indicates moderate changes in spectral resolution across the detector. While the interval with the smallest dispersion coefficient (0.037 nm/pixel) offers the highest resolution, the overall variation is sufficiently small that it has negligible impact for most practical applications where spectral lines are not extremely closely spaced. However, it is important to note that the same pixel position corresponds to different wavelengths in different intervals. Additionally, the wavelength change per pixel (resolution) varies across the spectral range, meaning that each interval requires its own distinct calibration parameters.

Figure 6. Linear regression of wavelengths versus pixel positions across three spectral intervals (1, 3, 4).

Table 2 presents the complete calibration results, including pixel positions, reference wavelengths, measured wavelengths, and their deviations for both Hg and Ne-Ar lamps across five spectral intervals.

Table 2. Emission lines from Hg/Ne-Ar lamps across five intervals with pixel positions, known wavelengths, and measurement deviations

Plasma imaging: Image formation and calibration

To tease out the generated plasma require capturing both spectral and spatial information, enabling the recovery of the plasma distribution along the capillary channel. This is achieved using a spectrometer coupled with a fast-gated ICCD camera, which offers a resolution of ![]() $1024 \times 255$ pixels. The setup enables the simultaneous recording of wavelength-resolved light (horizontal axis) and spatially-resolved emission along the plasma channel (vertical axis), producing a two-dimensional (2D) image of the plasma. The formation of the 2D image recorded by the ICCD captures both spectral and spatial dimensions of the plasma emission. Then, to extract physical information from the ICCD image, calibration procedures are required to convert pixel indices into physical units.

$1024 \times 255$ pixels. The setup enables the simultaneous recording of wavelength-resolved light (horizontal axis) and spatially-resolved emission along the plasma channel (vertical axis), producing a two-dimensional (2D) image of the plasma. The formation of the 2D image recorded by the ICCD captures both spectral and spatial dimensions of the plasma emission. Then, to extract physical information from the ICCD image, calibration procedures are required to convert pixel indices into physical units.

• Spectral Dimension (X-axis): Light emitted from the plasma enters the spectrometer, where it is dispersed by a diffraction grating. This dispersion spreads the light across the horizontal axis of the ICCD, so that each of the 1024 columns corresponds to a specific wavelength. This allows for the identification of emission lines from plasma species.

• Spatial Dimension (Y-axis): The entrance slit of the spectrometer is aligned with the longitudinal axis of the capillary, enabling light from different axial positions of the plasma to pass through the slit at different vertical positions. These are then mapped onto the 255 rows of the ICCD. Thus, each row corresponds to a unique position along the length of the capillary, preserving the spatial distribution of the emission.

• Spectral Calibration:

The spectral calibration maps the horizontal pixel position to the corresponding wavelength. The calibration factor is determined by dividing the total wavelength range covered by the grating by the number of horizontal pixels. For the available diffraction gratings:

(5) \begin{equation}

\text{{1200 g/mm}} - \gt \text{Conversion Factor} \ (\frac{\text{nm}}{\text{pixel}}) = \frac{60}{1024},

\end{equation}(6)

\begin{equation}

\text{{1200 g/mm}} - \gt \text{Conversion Factor} \ (\frac{\text{nm}}{\text{pixel}}) = \frac{60}{1024},

\end{equation}(6) \begin{equation}

\text{{2400 g/mm}} - \gt \text{Conversion Factor} \ (\frac{\text{nm}}{\text{pixel}}) = \frac{30}{1024}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\text{{2400 g/mm}} - \gt \text{Conversion Factor} \ (\frac{\text{nm}}{\text{pixel}}) = \frac{30}{1024}.

\end{equation}These values provide a global wavelength calibration that enables an accurate mapping of the emission lines.

• Spatial Calibration:

The spatial calibration converts vertical pixel positions to real distances along the capillary. Assuming a capillary length L capillary, the conversion factor is:

(7) \begin{equation}

\text{Conversion Factor} \ (\frac{\text{mm}}{\text{pixel}}) = \frac{L_{\text{capillary}}}{255}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\text{Conversion Factor} \ (\frac{\text{mm}}{\text{pixel}}) = \frac{L_{\text{capillary}}}{255}.

\end{equation}This allows each row of the ICCD image to be associated with a specific longitudinal position in the plasma.

Once both in situ calibrations have been completed and the corresponding factors have been determined, they are applied across the entire ICCD dataset. This enables a precise mapping of each pixel to its associated wavelength and longitudinal position, allowing for the extraction of spatially resolved plasma parameters. This approach is proposed for future implementation at the I-LUCE facility, as detailed in the spectroscopic setup discussed in Section 3.

Plasma formation and experimental setup

Plasma generation within gas-filled capillaries is achieved by electrical breakdown of the gas, leading to various discharge regimes such as dark, glow, or arc discharges. When a high voltage is applied across electrodes at both ends of the capillary, electrons emitted from the cathode are accelerated by the resulting electric field. These electrons collide with gas atoms, causing ionization and excitation processes that produce free electrons, ions, and photons, culminating in a self-sustaining plasma discharge. Additionally, ion bombardment of the cathode surface leads to secondary electron emission and material sputtering, further influencing the plasma characteristics.

The experimental setup (see Figure 7) for plasma generation in a gas-filled capillary includes a high-voltage system connected to electrodes at both ends, delivering pulsed kilovolt discharges with millisecond durations. Hydrogen gas, produced by electrolysis of water, is introduced into the capillary through mechanically controlled valves operating at repetition rates of 1–10 Hz. The internal pressure is maintained by a regulator to achieve optimal plasma conditions. Plasma initiation is facilitated by a resistor-capacitor (RC) circuit that provides the necessary ionization current.

Figure 7. Experimental setup for plasma discharge system and OES diagnostics.

During the discharge process, the light emitted from the plasma is collected and directed to a spectrometer for spectral dispersion, then recorded by an intensified charge-coupled device (ICCD) camera.

Simultaneously, electrical measurements are performed by monitoring the discharge current through voltage-to-current conversion. All system operations, including gas injection, discharge triggering, and diagnostic measurements, are synchronized by a delay generator.

The optical system enables plasma characterization through OES, with the emitted radiation serving as a diagnostic of local plasma conditions. The capillary configuration with hydrogen plasma offers particular advantages for diagnostics, as it produces strong visible emission lines while minimizing diffraction effects, allowing for accurate determination of electron density and temperature from the spectral features.

Plasma characterization via OES

Spectral analysis of these lines-particularly the Balmer series lines Hα (656.3 nm) and Hβ (486.1 nm) – enables reliable electron density characterization via spectral line broadening (SLB) and temperature expectation via their emission energy. These lines are favored for their strong intensity, high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), minimal spectral overlap, and the availability of extensive empirical data sets (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler2). By analysing the broadening of hydrogen emission lines, particularly Hα and Hβ, we can probe the behaviour of free electrons in the plasma, enabling diagnostics of electron density and the electric field near emitters. Although free electrons do not emit discrete spectral lines (their radiation is continuous, e.g. bremsstrahlung), their role as perturbs is critical.

Their high mobility and density induce rapid electric field fluctuations around emitting species, leading to measurable spectral broadening. SLB in plasma arises from several effects (Ref. Reference Fujimoto12):

• Natural broadening – finite lifetime of excited states,

• Doppler broadening – thermal motion of emitting particles,

• Stark broadening – electric fields from charged particles,

• Quasi-static broadening – slowly varying ion fields,

• Impact or collisional broadening – frequent particle collisions.

The dominant mechanism depends on plasma conditions (Ref. Reference Parigger, Drake, Helstern and Gautam13). Doppler broadening results in a Gaussian profile and originates from the motion of emitters – typically heavier species like ions or neutrals. Notably, electrons do not contribute to Doppler broadening, as they do not serve as emitters in this context. Instead, Stark and collisional broadening produce Lorentzian line shapes. When both Gaussian and Lorentzian contributions are present, the overall line profile is described by a Voigt function.

To illustrate this, several theoretical line-shape distributions were compared with experimental data, as shown in (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Costa, Di Pirro, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Del Giorno, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler14). Figure 8 presents a comparison of the three line-shape models-Gaussian, Lorentzian, and Voigt-fitted to the experimental Hβ line. Firstly, the data show two close peaks, which could stem from fine-structure splitting in Hβ. However, that splitting is only 0.016 nm-far below the instrument’s 0.1 nm resolution and further blurred by Stark broadening – so it is negligible.

Figure 8. Comparison of Gaussian, Lorentzian, and Voigt line shapes for Hβ line (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Costa, Di Pirro, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Del Giorno, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler14)(CC BY-SA 4.0).

The Lorentzian fit shows broader wings compared to the Gaussian and aligns more closely with the experimental data in these outer regions. While it slightly deviates at the peak, it provides a better overall match to the wings, suggesting that pressure broadening dominates under these plasma conditions. The Gaussian fit fails to capture the wings and tails, sharply dropping off and underestimating the experimental data in those regions. Although its symmetric bell-shaped form aligns reasonably well in the centre, it does not reproduce the broader features, especially on the left wing. The Voigt profile, which theoretically combines Doppler and pressure broadening effects, shows a reasonably good fit similar to the Lorentzian. However, in this case, it slightly overestimates the peak amplitude and deviates from the experimental points in both the core and wings, suggesting that the Lorentzian component is more representative of the actual broadening mechanism.

We evaluated the goodness of fit using two metrics: the sum of squared errors (SSE), which measures the total squared difference between observed and modelled values, and R-squared (R2), the coefficient of determination that quantifies the proportion of the data’s variance explained by the model (ranging from 0 to 1). A high R2 and low SSE indicate a better model agreement. As shown in Table 3, the Lorentzian and Voigt profiles significantly outperform the Gaussian fit. Specifically, the Lorentzian model achieves the highest R2 (0.96) and the lowest SSE (2.27e+8), making it the most suitable for deriving the plasma electron distribution and interpreting the line broadening.

Table 3. Goodness of fit for ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$ profile. R2 and SSE values comparing Gaussian, Lorentzian, and Voigt fits to the

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$ profile. R2 and SSE values comparing Gaussian, Lorentzian, and Voigt fits to the ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$ line

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$ line

This comparison supports our conclusion that Stark broadening is the dominant mechanism, with a negligible Doppler effect (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Costa, Di Pirro, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Del Giorno, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler14). This line-broadening analysis is a crucial extension of established methods for measuring electron temperature and density.

Thus, in low-pressure plasmas, such as those produced in our discharge capillaries, Stark broadening – also known as the Stark–Lo Surdo effect – is typically the dominant broadening mechanism. It is particularly sensitive to the density and dynamics of free electrons, making it a robust tool for diagnostics. Theoretical treatments of Stark broadening incorporate effects such as Debye shielding, ion dynamics, and the motion of the emitters themselves (Refs Reference Griem15, Reference Gigosos and Cardeñoso16).

The theoretical framework for Stark broadening analysis has evolved through successive refinements, improving diagnostic accuracy. Foundational work established the modern paradigm through Stark broadening tables (SBT), employing the quasi-static approximation for ion microfields, impact approximation for electron microfields and decoupled treatment of field interactions (Ref. Reference Griem15). These tables enabled robust electron density determination via full width at half maximum (FWHM) measurements of hydrogen lines, a methodology validated by later studies (Refs Reference Griem15, Reference Gigosos and Cardeñoso16, Reference Vidal, Cooper and Smith17). The FWHM remains the standard metric due to its direct physical interpretation and experimental accessibility.

Computational advancements led to improved Stark broadening models, with numerical simulations overcoming limitations of analytical approximations through self-consistent field calculations and enhanced line profile resolution (Ref. Reference Gigosos and Cardeñoso16).

Further developments introduced the full width at half area (FWHA) parameter, demonstrating superior performance in low-density regimes (Ref. Reference Gigosos, González and Cardeñoso19). Recent work has refined these methods by addressing systematic biases, yielding improved metrics such as the half-halfwidth at half area (HHWA) (Ref. Reference Mijatović, Djurović, Gavanski, Gajo, Favre, Morel and Bultel20).

The choice of spectral line for plasma diagnostics is critical, as different emission lines provide distinct insights into plasma parameters. Line intensity ratios serve as reliable indicators of electron temperature, while Stark-broadened line widths correlate with electron density. Additionally, the full spectral profile reveals underlying plasma processes. Among the Balmer series, Hβ has been widely adopted as the most robust diagnostic line, offering reliable density measurements in both low (≤1015 cm−3) and high (1017–1018 cm−3) density regimes, with its capability to determine electron density with ![]() $\pm7\%$ accuracy (Ref. Reference Wiese, Kelleher and Paquette21). However, at high electron densities (≥1018 cm−3), Hβ becomes broad (Ref. Reference Griem15), leading to spectral overlap with nearby lines and continuum blending, which complicates accurate measurement.

$\pm7\%$ accuracy (Ref. Reference Wiese, Kelleher and Paquette21). However, at high electron densities (≥1018 cm−3), Hβ becomes broad (Ref. Reference Griem15), leading to spectral overlap with nearby lines and continuum blending, which complicates accurate measurement.

In such high-density scenarios, Hα presents a viable alternative due to its narrower profile – typically four times narrower than Hβ under identical conditions – and its higher intensity, which improves the SNR. Historically, Hα has been less favoured due to challenges such as self-absorption effects and discrepancies between theoretical and experimental results at low densities (≤1015 cm−3) (Ref. Reference Griem22). Meanwhile, Hγ has been shown to match Hβ’s accuracy at low densities (≤1015 cm−3) (Ref. Reference Mijatović, Djurović, Gavanski, Gajo, Favre, Morel and Bultel20), but remains less commonly used due to its weaker emission intensity. The selection between Hα and Hβ ultimately depends on the target density range, instrumental resolution, and required precision, with Hβ remaining the standard for general applications while Hα gains traction in extreme-density plasmas.

The interest of this work Stark broadening of hydrogen spectral lines by Griem theory, which the FWHM, ![]() $\Delta \lambda_{1/2}$, of the Stark-broadened line is directly related to the local electron density and can be extracted using empirical models and tabulated data (Ref. Reference Jang, Kim, Nam, Uhm and Suk23):

$\Delta \lambda_{1/2}$, of the Stark-broadened line is directly related to the local electron density and can be extracted using empirical models and tabulated data (Ref. Reference Jang, Kim, Nam, Uhm and Suk23):

\begin{equation}

n_e \ [cm^{-3}] = 8.02 \times 10^{12} \left[ \frac{\Delta \lambda_{\frac{1}{2}}}{\alpha_\frac{1}{2}}\right] ^{\frac{3}{2}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

n_e \ [cm^{-3}] = 8.02 \times 10^{12} \left[ \frac{\Delta \lambda_{\frac{1}{2}}}{\alpha_\frac{1}{2}}\right] ^{\frac{3}{2}},

\end{equation} where ![]() $\alpha_{\frac{1}{2}}$ is a line-broadening parameter (fractional intensity width) that depends on both electron density and electron temperature. It is widely tabulated in the literature for hydrogen Balmer lines (Ref. Reference Griem15). Electron densities in the range of 1017–

$\alpha_{\frac{1}{2}}$ is a line-broadening parameter (fractional intensity width) that depends on both electron density and electron temperature. It is widely tabulated in the literature for hydrogen Balmer lines (Ref. Reference Griem15). Electron densities in the range of 1017–![]() ${10}^{19}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ are typically associated with temperatures below 10 eV. For example, at a density of

${10}^{19}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ are typically associated with temperatures below 10 eV. For example, at a density of ![]() $10^{17} \ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ and a corresponding temperature range of 1–4 eV,

$10^{17} \ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ and a corresponding temperature range of 1–4 eV, ![]() $\alpha_{\frac{1}{2}}$ ranges from 0.00186 to 0.00158 nm for the Hα line and from 0.00851 to 0.00927 nm for the

$\alpha_{\frac{1}{2}}$ ranges from 0.00186 to 0.00158 nm for the Hα line and from 0.00851 to 0.00927 nm for the ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ line (Ref. Reference Griem15). This is particularly valid in our case, where the plasma is emitted in the visible range and operates at temperatures of approximately 1–4 eV, allowing other broadening mechanisms to be neglected.

$\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ line (Ref. Reference Griem15). This is particularly valid in our case, where the plasma is emitted in the visible range and operates at temperatures of approximately 1–4 eV, allowing other broadening mechanisms to be neglected.

Figure 9 shows the evolution of the electron density (ne) as a function of plasma recombination time, derived from Hα and Hβ line measurements under 12 kV, 400 A discharge, as reported in (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler2).

Figure 9. Retrieved electron density from Hα and ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$ line as a function of time in a 3 cm length/1 mm diameter capillary (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler2) (CC BY-SA 4.0).

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$ line as a function of time in a 3 cm length/1 mm diameter capillary (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler2) (CC BY-SA 4.0).

A notable difference is observed between the plasma densities measured from the Hα and Hβ lines, with the Hα-based measurement yielding values nearly twice as high. This variation can be attributed to the intrinsic characteristics of the Hα line, such as its increased sensitivity to self-absorption and its relatively higher signal strength (Ref. Reference Gigosos and Cardeñoso16). Self-absorption means that some emitted photons are re-absorbed by the plasma before escaping. While this makes the line easier to detect, it can also result in an artificially higher density estimate. In contrast, the ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$ line, being less affected by these factors because it is at a shorter wavelength and has a lower transition probability – so its line is more optically thin and more reliable for actual plasma density. In our case,

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$ line, being less affected by these factors because it is at a shorter wavelength and has a lower transition probability – so its line is more optically thin and more reliable for actual plasma density. In our case, ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\alpha$ (higher opacity) is absorbed more than

$\mathrm{H}_\alpha$ (higher opacity) is absorbed more than ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$ thus the observed

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$ thus the observed ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\alpha$/

$\mathrm{H}_\alpha$/![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$ ratio decreases which

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$ ratio decreases which ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\alpha$ is absorbed 2 times more than

$\mathrm{H}_\alpha$ is absorbed 2 times more than ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$, then the ratio drops by ∼ 30-50%. This can reveal that we have moderate self-absorption and still have an optically thin plasma.

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$, then the ratio drops by ∼ 30-50%. This can reveal that we have moderate self-absorption and still have an optically thin plasma.

Emission lines also provide valuable information on line intensities, which are governed by plasma thermodynamics. For example, the ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$ line (486.1 nm, 2.55 eV) arises from hydrogen transitions from n = 4 to n = 2. This is illustrated in Figure 10, which is derived from the spectral data presented in Figure 8.

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$ line (486.1 nm, 2.55 eV) arises from hydrogen transitions from n = 4 to n = 2. This is illustrated in Figure 10, which is derived from the spectral data presented in Figure 8.

Figure 10. Photon energy of ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$ line with Lorentzian fit converted from Figure 8.

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$ line with Lorentzian fit converted from Figure 8.

Although the transition energy is fixed, the line intensity depends on the electron temperature due to the ionization-recombination equilibrium. The Saha equation quantitatively relates Te to the ionization state:

\begin{equation}

\frac{n_e \ n_p}{n_H} = \left (\frac{2 \pi m_e k_B T}{h^2} \right)^\frac{3}{2} \text{exp} \left ( \frac{E_H}{k_B T}\right ),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\frac{n_e \ n_p}{n_H} = \left (\frac{2 \pi m_e k_B T}{h^2} \right)^\frac{3}{2} \text{exp} \left ( \frac{E_H}{k_B T}\right ),

\end{equation}where nH: neutral hydrogen density, np: proton density, ne: electron density, me: electron mass, T: absolute temperature (K), kB: Boltzmann constant, h: Planck constant, EH: hydrogen ionization energy (13.6 eV).

This reveals three temperature regimes for ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$ emission. From Equation 9, we can observe that at low temperatures (e.g. below 8,000 K or 0.68 eV), the exponential term (

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$ emission. From Equation 9, we can observe that at low temperatures (e.g. below 8,000 K or 0.68 eV), the exponential term ( $\text{exp}( \frac{E_H}{k_B T})\ll$ 1) maintains hydrogen neutrality (

$\text{exp}( \frac{E_H}{k_B T})\ll$ 1) maintains hydrogen neutrality (![]() $n_H \gg n_p$), quenching the recombination of emission.

$n_H \gg n_p$), quenching the recombination of emission.

As the temperature increases (![]() $ 8,000$ K

$ 8,000$ K ![]() $\leq T_e \leq 15,000$ K), optimal Hβ production as partial ionization (

$\leq T_e \leq 15,000$ K), optimal Hβ production as partial ionization (![]() $n_p \sim n_H$) enables efficient recombination:

$n_p \sim n_H$) enables efficient recombination:

\begin{equation}

\epsilon_{H_{\beta}} \propto n_e n_p {\alpha}{H^{eff}_{\beta}} (T_e),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\epsilon_{H_{\beta}} \propto n_e n_p {\alpha}{H^{eff}_{\beta}} (T_e),

\end{equation} where  ${\alpha}{H^{eff}_{\beta}}$ is the temperature-dependent effective recombination coefficient. Then at

${\alpha}{H^{eff}_{\beta}}$ is the temperature-dependent effective recombination coefficient. Then at ![]() $ T_e \gt 15,000$ K (1.29 eV), hydrogen becomes significantly ionized, or reaches near-complete ionization (

$ T_e \gt 15,000$ K (1.29 eV), hydrogen becomes significantly ionized, or reaches near-complete ionization (![]() $n_H \leftarrow 0$) depletes recombination targets, diminishing Hβ.

$n_H \leftarrow 0$) depletes recombination targets, diminishing Hβ.

However, determining the electron temperature in capillary discharges can be approached through various methods, including detailed plasma modelling. For rapid estimation, in capillary discharges, the peak on-axis electron temperature can be estimated using a simplified model that balances electron thermal conductivity and Joule heating. This approach yields a scaling law for the electron temperature:

\begin{equation}

T_e \ \text{[eV]} = 5.7 \left[ \frac{I}{r_{cap}} \right]^\frac{2}{5}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

T_e \ \text{[eV]} = 5.7 \left[ \frac{I}{r_{cap}} \right]^\frac{2}{5}.

\end{equation}Here, I (kV) is the discharge current measured from the oscilloscope, and rcap (mm) is the capillary radius (Refs Reference Bobrova, Esaulov, Sakai, Sasorov, Spence, Butler, Hooker and Bulanov24, Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Franco, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler25). For a discharge current of 0.4 kA and a capillary radius of 0.5 mm (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler2), this formula predicts an on-axis electron temperature of ∼5.2 eV. At this temperature, electrons possess sufficient energy to fully ionize hydrogen, supporting the formation of a plasma channel. This method assumes that the plasma approaches a quasi-static model (QSM), which is particularly useful for understanding the dynamics in capillary discharge plasmas.

While the QSM offers a useful initial estimate, it simplifies plasma dynamics by neglecting temporal variations, cooling effects, and recombination. Nevertheless, it serves as a practical tool for assessing whether plasma conditions are suitable for full ionization and aids in the design and diagnostics of plasma-based accelerators. The actual plasma formation process occurs through distinct evolutionary stages (Ref. Reference Gonsalves, Liu, Bobrova, Sasorov, Pieronek, Daniels, Antipov, Butler, Bulanov, Waldron, Mittelberger and Leemans26).

Following discharge initiation, the system progresses from initial ionization through thermal conduction build-up before reaching full ionization. Only in the subsequent phase does the plasma approach a quasi-steady state with characteristic parabolic electron density profiles, featuring a central temperature maximum and density minimum.

However, the QSM remains an idealized approximation. It assumes axial uniformity and neglects energy losses, spatial gradients, and time-dependent effects. As a result, it tends to overestimate the maximum temperature, particularly in the early discharge phases before thermal equilibrium is established. The predicted value represents an upper limit rather than an average, as it does not account for recombination, cooling, or axial inhomogeneities. Despite these simplifications, the model’s predictive capability offers a valuable theoretical benchmark. Our experimental measurements aim to quantify the deviation between this idealized prediction and observed plasma conditions, particularly during the critical transition to full ionization.

To end this, to determine the electron temperature (Te) in our hydrogen plasma discharge, we employ population models that account for excitation and de-excitation processes. The choice of model depends on the plasma density and dominant processes, with three primary models:

• Corona: Applicable to low-density plasmas where radiative processes dominate,

• Local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE): Valid for high-density plasmas where collisional processes thermalize level population,

• Collisional-radiative (CR): Bridges the gap between corona and LTE regimes, accounting for both collisional and radiative processes.

For our hydrogen plasma with ![]() $n_e \approx 10^{17}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ (see Figure 9) and Te expected between 1 and 4 eV from Griem’s theory, we first assess whether the LTE conditions hold. The LTE criterion requires ne to exceed the critical density

$n_e \approx 10^{17}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ (see Figure 9) and Te expected between 1 and 4 eV from Griem’s theory, we first assess whether the LTE conditions hold. The LTE criterion requires ne to exceed the critical density ![]() $n^{LTE}_c$, which is the density at which the collisional de-excitation rate equals the radiative decay rate for a given transition:

$n^{LTE}_c$, which is the density at which the collisional de-excitation rate equals the radiative decay rate for a given transition:

\begin{equation}

n^{LTE}_c \gt rapprox 10^{16} \ \text{cm}^{-3} \times (\frac{T_e}{10^4 K})^{\frac{1}{2}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

n^{LTE}_c \gt rapprox 10^{16} \ \text{cm}^{-3} \times (\frac{T_e}{10^4 K})^{\frac{1}{2}}.

\end{equation} For Te of 1-4 eV, nc varies from ![]() $1.08 \times 10^{16}$ to

$1.08 \times 10^{16}$ to ![]() $2.16 \times 10^{16}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$. Given that our plasma’s electron density is

$2.16 \times 10^{16}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$. Given that our plasma’s electron density is ![]() $10^{17} \ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$, which exceeds this threshold, it suggests that LTE is plausible.

$10^{17} \ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$, which exceeds this threshold, it suggests that LTE is plausible.

A stricter validation involves comparing ne with the critical density (nc) for specific transitions, where collisional de-excitation balances radiative decay:

\begin{equation}

n_{c} \ [\text{cm}^{-3}] = \frac{A_{ul}}{\gamma_{ul}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

n_{c} \ [\text{cm}^{-3}] = \frac{A_{ul}}{\gamma_{ul}},

\end{equation} with Aul S −1 as the Einstein coefficient and ![]() $\gamma_{ul} (\mathrm{cm}^3$) as the collisional de-excitation rate coefficient (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Costa, Di Pirro, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Del Giorno, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler14). As shown in Table 4, the critical densities for the hydrogen lines are significantly lower than our measured electron density, confirming that collisional processes dominate.

$\gamma_{ul} (\mathrm{cm}^3$) as the collisional de-excitation rate coefficient (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Costa, Di Pirro, Ferrario, Del Franco, Galletti, Del Giorno, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler14). As shown in Table 4, the critical densities for the hydrogen lines are significantly lower than our measured electron density, confirming that collisional processes dominate.

Table 4. Considered critical density (nc) for ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$ and

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$ and ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ lines

$\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ lines

Furthermore, the widely used McWhirter criterion provides a stricter check for LTE validity, which establishes the minimum electron density required to ensure that collisional processes dominate over radiative processes (Ref. Reference McWhirter27):

\begin{equation}

n_e \ [\text{cm}^{-3}] \geq 1.6 \times 10^{12} \ T_e^{\frac{1}{2}} \ (\Delta E)^3,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

n_e \ [\text{cm}^{-3}] \geq 1.6 \times 10^{12} \ T_e^{\frac{1}{2}} \ (\Delta E)^3,

\end{equation} where ![]() $\Delta E$ is the energy gap between the upper and lower levels of the transition. The

$\Delta E$ is the energy gap between the upper and lower levels of the transition. The ![]() $\Delta E$ between hydrogen energy levels is crucial because it directly influences the rates of collisional excitation and de-excitation processes.

$\Delta E$ between hydrogen energy levels is crucial because it directly influences the rates of collisional excitation and de-excitation processes.

A larger ![]() $\Delta E$ corresponds to a lower probability of collisional excitation, necessitating a higher electron density to achieve LTE. For the Hα and Hβ transitions, the values of

$\Delta E$ corresponds to a lower probability of collisional excitation, necessitating a higher electron density to achieve LTE. For the Hα and Hβ transitions, the values of ![]() $\Delta E$ are ≈1.9 and 2.55 eV, respectively. At electron temperatures of 1–4 eV, the minimum electron densities required to maintain LTE are the following:

$\Delta E$ are ≈1.9 and 2.55 eV, respectively. At electron temperatures of 1–4 eV, the minimum electron densities required to maintain LTE are the following:

• Hα:

$\approx 1.09 \times 10^{13}$ to

$\approx 1.09 \times 10^{13}$ to  $2.19\times 10^{13}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$,

$2.19\times 10^{13}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$,• Hβ:

$\approx 2.65 \times 10^{13}$ to

$\approx 2.65 \times 10^{13}$ to  $5.31 \times 10^{13}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$.

$5.31 \times 10^{13}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$.

Lastly, the Hα/Hβ ratio known as the Balmer decrement is used to assess whether the LTE conditions are satisfied. This ratio reflects the balance between collisional and radiative processes that govern the excitation and de-excitation of hydrogen atoms. To evaluate this, we begin by converting level populations into line intensities and then calculate the Hα/Hβ intensity ratio. The intensity of an emission line is directly related to the population of the upper energy level involved in the transition. This relationship is given by:

where Iul: transition intensity of upper level u to lower level l, nu: population density of the upper level, Aul: Einstein coefficient (probability of emission), h: Planck’s constant, ν: frequency of the emitted light.

Applying this to the lines Hα (transition from n = 3 to n = 2) and Hβ (transition from n = 4 to n = 2):

\begin{equation}

\frac{I_{H_{\alpha}}}{I_{H_{\beta}}} = \frac{n_{3} \cdot A_{{32}} \cdot \nu{_{32}}}{n_{{4}} \cdot A_{42} \cdot \nu{_{42}}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\frac{I_{H_{\alpha}}}{I_{H_{\beta}}} = \frac{n_{3} \cdot A_{{32}} \cdot \nu{_{32}}}{n_{{4}} \cdot A_{42} \cdot \nu{_{42}}}.

\end{equation}The population densities n 2 and n 4 can be related using the Boltzmann distribution:

\begin{equation}

\frac{n_3}{n_4} = \frac{g_{3}} {g_{4}} \ \cdot \text{exp} \left (- \frac{E_{3} - E_{4}}{k_B T_e} \right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\frac{n_3}{n_4} = \frac{g_{3}} {g_{4}} \ \cdot \text{exp} \left (- \frac{E_{3} - E_{4}}{k_B T_e} \right),

\end{equation} where ![]() $g_{n} = 2n^2$: the statistical weight of level n,

$g_{n} = 2n^2$: the statistical weight of level n,  $E_{n} = - 13.6 \ \frac{\text{eV}}{n^2}$: energy of level n, kB: Boltzmann constant, Te: electron temperature.

$E_{n} = - 13.6 \ \frac{\text{eV}}{n^2}$: energy of level n, kB: Boltzmann constant, Te: electron temperature.

Substituting Equation 17 into Equation 16, we obtain the final expression for the Hα/Hβ ratio:

\begin{equation}

\frac{I_ {H_{\alpha}} }{I_{H_{\beta}}} = \left ( \frac{g_3}{g_4} \cdot \text{exp} \left ( - \frac{E_3 - E_ 4} {k_B T_e} \right ) \right ) \cdot \left ( \frac{A_{32} . \nu_{32}}{A_{{42}} . \nu_{{42}}} \right).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\frac{I_ {H_{\alpha}} }{I_{H_{\beta}}} = \left ( \frac{g_3}{g_4} \cdot \text{exp} \left ( - \frac{E_3 - E_ 4} {k_B T_e} \right ) \right ) \cdot \left ( \frac{A_{32} . \nu_{32}}{A_{{42}} . \nu_{{42}}} \right).

\end{equation}Figure 11 illustrates the time-dependent Hα/Hβ ratio. In our observations, the Hα/Hβ ratio fluctuates between 0.5 and approximately 1, suggesting that the plasma is optically thin and predominantly influenced by collisional excitation, characteristic of Case A conditions. Such low ratios indicate that collisional processes dominate and that the plasma maintains LTE. In contrast, under Case B conditions, where radiative recombination prevails, the Hα/Hβ ratio typically approaches or exceeds 2.86, as established by recombination theory (Ref. Reference Griem28).

Figure 11. Hα/Hβ ratio as a function of time. The dashed line marks the theoretical threshold value.

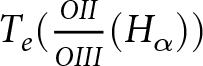

Having confirmed that the plasma satisfies LTE conditions, we can proceed to estimate the Te using LTE-based diagnostics. Under LTE the Te can be determined by analysing the Hα/Hβ intensity ratio, as previously discussed. Alternatively, it can be estimated by comparing the intensities of spectral lines from different ionization states of the same element (e.g. O II and O III), provided that the plasma density is known (Ref. Reference Griem15).

Focusing on the first approach, with the electron density and ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$/

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$/![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ ratio determined, rearrange the Boltzmann equation to solve for the electron temperature:

$\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ ratio determined, rearrange the Boltzmann equation to solve for the electron temperature:

\begin{equation}

\frac{n_u}{n_l} = \frac{g_u}{g_l} \cdot \ \text{exp} \left( - \frac{E_u - E_l}{k_B T_e} \right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\frac{n_u}{n_l} = \frac{g_u}{g_l} \cdot \ \text{exp} \left( - \frac{E_u - E_l}{k_B T_e} \right),

\end{equation}which can be rearranged to:

\begin{equation}

T_e = \frac{E_u - E_l}{k_B \ \left [ln \ (\frac{g_l}{g_u} \cdot \frac{n_u}{n_l}) \right]}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

T_e = \frac{E_u - E_l}{k_B \ \left [ln \ (\frac{g_l}{g_u} \cdot \frac{n_u}{n_l}) \right]}.

\end{equation} Here, ![]() $E_u - E_l$ is the excitation energy required to excite an electron from the lower energy level l to the upper level u. By substituting the known values for the energy levels and statistical weights, and using the measured intensity ratio to determine

$E_u - E_l$ is the excitation energy required to excite an electron from the lower energy level l to the upper level u. By substituting the known values for the energy levels and statistical weights, and using the measured intensity ratio to determine ![]() $\frac{n_u}{n_l}$, we can calculate the electron temperature. All relevant parameters can be obtained from the NIST database (Ref. 11) by selecting the desired spectral line. Table 5 summarizes the atomic parameters relevant to the Hα and Hβ lines.

$\frac{n_u}{n_l}$, we can calculate the electron temperature. All relevant parameters can be obtained from the NIST database (Ref. 11) by selecting the desired spectral line. Table 5 summarizes the atomic parameters relevant to the Hα and Hβ lines.

Table 5. Atomic parameters for ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\alpha$ and

$\mathrm{H}_\alpha$ and ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$

The electron temperature derived from the ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$/

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$/![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ intensity ratio is presented in Figure 12.

$\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ intensity ratio is presented in Figure 12.

The observed electron temperature ranges from approximately 0.9 to 5 eV, which extends beyond the typical expected range of 1–4 eV for such plasmas.

Figure 12. Retrieved electron temperature from Hα/Hβ ratio.

The deviation in the ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$/

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$/![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$-derived electron temperature can be attributed to several factors, with self-absorption being a primary contributor. This phenomenon occurs when emitted

$\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$-derived electron temperature can be attributed to several factors, with self-absorption being a primary contributor. This phenomenon occurs when emitted ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$ photons are reabsorbed by cooler plasma regions along the line of sight, distorting the observed line profile and artificially altering the

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$ photons are reabsorbed by cooler plasma regions along the line of sight, distorting the observed line profile and artificially altering the ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$/

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$/![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ ratio, leading to inaccurate temperature estimations.

$\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ ratio, leading to inaccurate temperature estimations.

Additionally, different emission lines respond uniquely to local plasma conditions because of variations in excitation and recombination processes. The ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$ and

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$ and ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ lines, being recombination lines, are particularly sensitive to cooler plasma zones where recombination dominates. Consequently, their emission is biased toward these regions, skewing the inferred temperature toward an average that may not represent the entire plasma.

$\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ lines, being recombination lines, are particularly sensitive to cooler plasma zones where recombination dominates. Consequently, their emission is biased toward these regions, skewing the inferred temperature toward an average that may not represent the entire plasma.

For more robust diagnostics, collisionally excited lines, such as O II and O III are preferable. These lines are less susceptible to self-absorption because they originate in ionized regions with lower optical depths compared to ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$. Moreover, since their excitation depends directly on electron collisions, they provide a more reliable measure of the local electron temperature in their respective ionized zones.

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$. Moreover, since their excitation depends directly on electron collisions, they provide a more reliable measure of the local electron temperature in their respective ionized zones.

An alternative diagnostic approach involves analysing spectral line intensity ratios of the same ion. However, the minimal differences in excitation energies and inherent theoretical uncertainties limit the precision of temperature measurements using single-ion line ratios. For dense plasmas in LTE conditions, a more robust technique involves analysing intensity ratios between successive ionization states (e.g. O II/O III or N II/N III). This method capitalizes on the more pronounced temperature sensitivity of the ionization equilibrium, yielding more accurate diagnostics. The diagnostic power of this approach stems from its independent determination of plasma parameters: electron density from ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$ or

$\mathrm{H}_{\alpha}$ or ![]() $\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ line broadening and electron temperature from O II/O III line ratios. This separation ensures that temperature measurements remain unaffected by Hα self-absorption effects. The intensity ratio method thus provides a valuable complement to Hα/Hβ diagnostics, especially in regions where recombination processes may distort measurements, given as (Ref. Reference Griem15):

$\mathrm{H}_{\beta}$ line broadening and electron temperature from O II/O III line ratios. This separation ensures that temperature measurements remain unaffected by Hα self-absorption effects. The intensity ratio method thus provides a valuable complement to Hα/Hβ diagnostics, especially in regions where recombination processes may distort measurements, given as (Ref. Reference Griem15):

\begin{align}

R& = \frac{{\lambda_2}^3 \ f_2 \ g_2}{{\lambda_1}^3 \ f_1 \ g_1} \left( 4 \pi^{\frac{3}{2} a_0^3 n_e} \right)^{-1} \left( \frac{T_e}{E_H} \right)^{(\frac{3}{2})} \nonumber \\

&\quad \times \text{exp} \left( - \frac{E_2 + E_{\infty} - E_1 - \Delta E_{\infty}}{T_e} \right),

\end{align}

\begin{align}

R& = \frac{{\lambda_2}^3 \ f_2 \ g_2}{{\lambda_1}^3 \ f_1 \ g_1} \left( 4 \pi^{\frac{3}{2} a_0^3 n_e} \right)^{-1} \left( \frac{T_e}{E_H} \right)^{(\frac{3}{2})} \nonumber \\

&\quad \times \text{exp} \left( - \frac{E_2 + E_{\infty} - E_1 - \Delta E_{\infty}}{T_e} \right),

\end{align} where a 0: Bohr radius, g: statistical weight, λ: spectral line wavelength, f: absorption oscillator strength, E: spectral line excitation energy, EH: hydrogen ionization energy, ![]() $E_{\infty}$: lower stage ionization energy,

$E_{\infty}$: lower stage ionization energy, ![]() $\Delta E_{\infty}$: correction factor (ionization energy reduction or shift to

$\Delta E_{\infty}$: correction factor (ionization energy reduction or shift to ![]() $E_{\infty}$).

$E_{\infty}$).

The parameters with subscripts 1 and 2 correspond to the lower and upper energy levels of the transition, respectively. To identify additional ions present in a hydrogen plasma, it is useful to analyse the emission spectrum while considering the capillary material. Understanding the chemical composition is essential because elements of the capillary can be introduced into the plasma. For example, VeroClear, a material similar to polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), commonly known as acrylic, contains carbon and oxygen (![]() $\mathrm{C}_5\mathrm{O}_2\mathrm{H}_8$), which may be released into the plasma during processing. These elements can contribute to observed spectral lines through excitation and emission processes, as reported in (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler29). Some lines may be more prominent in cooler regions, while others become significant at higher temperatures, even within the same physical location in the plasma.

$\mathrm{C}_5\mathrm{O}_2\mathrm{H}_8$), which may be released into the plasma during processing. These elements can contribute to observed spectral lines through excitation and emission processes, as reported in (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler29). Some lines may be more prominent in cooler regions, while others become significant at higher temperatures, even within the same physical location in the plasma.

Using the electron density values determined from each line as reported in Figure 9, and applying the subsequent ionization stage method described earlier, we calculated the correction factor (CF) for the Hα and Hβ lines. All relevant atomic data were taken from (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler29). Table 6 presents the corresponding plasma parameters derived at different times.

Table 6. Correction factor (![]() $\Delta E_{\infty}$) for

$\Delta E_{\infty}$) for ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\alpha$ and

$\mathrm{H}_\alpha$ and ![]() $\mathrm{H}_\beta$ lines as a function of time

$\mathrm{H}_\beta$ lines as a function of time

By analysing the emission lines of singly ionized oxygen (O II at 471.9803 nm) and doubly ionized oxygen (O III at 508.8922 nm), we determined the electron temperature as a function of plasma recombination time, as depicted in Figure 13. All physical constants and spectral data for oxygen ions are taken from (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Anania, Biagioni, Ferrario, Galletti, Lollo, Pellegrini, Pompili and Zigler29).

Figure 13. Retrieved plasma electron temperatures,  $T_e (\frac{O II}{O III} (H_{\alpha}))$ and

$T_e (\frac{O II}{O III} (H_{\alpha}))$ and  $T_e (\frac{O II}{O III} (H_{\beta}))$, as a function of time in a 3 cm length/1 mm diameter capillary.

$T_e (\frac{O II}{O III} (H_{\beta}))$, as a function of time in a 3 cm length/1 mm diameter capillary.

The electron temperature exhibits a gradual decline from approximately 2.4 to 2.1 eV, correlating with the plasma’s recombination dynamics. Both spectral lines display consistent downward trends, aligning with the observed decrease in electron density. However, minor discrepancies between the temperatures derived from O II and O III suggest sensitivity to local plasma conditions or potential line broadening effects, which may affect the precision of these measurements compared to diagnostics utilizing heavier atomic species.

Unlike the Hα and Hβ line ratios, which can be influenced by recombination processes at lower temperatures, the electron temperature is more reliably determined from the intensity ratio of the O II/O III lines. These lines, arising from ionization and recombination processes, are less affected by such effects and better reflect the actual plasma temperature.

The intensity ratio between O II and O III, representing different ionization states of oxygen, is primarily governed by electron temperature, making it a more accurate indicator with fewer distortions from plasma conditions. The electron temperature in our plasma reaches a maximum of 2.4 eV, approximately 0.46 times lower than the maximum on-axis temperature achievable along the plasma axis, as reported earlier. Despite this, the plasma maintains sufficiently high electron temperatures to support dominant electron-electron collisions. This is corroborated by Stark broadening measurements, which indicate that electron collisions are the primary broadening mechanism in our plasma. Furthermore, the consistency of these findings with the assumptions of LTE reinforces the validity of our diagnostic techniques and the applicability of LTE to characterize the plasma state. This method aligns well with the expected electron temperature, given the plasma’s density, indicating its higher accuracy under LTE conditions.

To further validate the presence of specific ions in the plasma, theoretical simulations based on established databases such as NIST atomic spectra (Ref. 11) can be employed. We consider a VeroClear (![]() $\mathrm{C}_5\mathrm{O}_2\mathrm{H}_8$) capillary – composed of 82% C, 16% O, 1% H and 1% N – with an electron density of

$\mathrm{C}_5\mathrm{O}_2\mathrm{H}_8$) capillary – composed of 82% C, 16% O, 1% H and 1% N – with an electron density of ![]() $5 \times 10^{17}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ at the Hα emission time of 1500 ns (Figure 9), corresponding to 2.3 eV (Figure 13). However, diagnostics based on the Hα/Hβ intensity ratio (Figure 12) suggest that the electron temperature may actually range from 0.8 to 5 eV. To ensure that forbidden lines from C I, C II, C III, N I, N II, N III, and O I, O II and O III remain detectable even at this temperature range, we simulate their emission spectra for

$5 \times 10^{17}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ at the Hα emission time of 1500 ns (Figure 9), corresponding to 2.3 eV (Figure 13). However, diagnostics based on the Hα/Hβ intensity ratio (Figure 12) suggest that the electron temperature may actually range from 0.8 to 5 eV. To ensure that forbidden lines from C I, C II, C III, N I, N II, N III, and O I, O II and O III remain detectable even at this temperature range, we simulate their emission spectra for ![]() $T_e = 1\,\mathrm{eV}$ and

$T_e = 1\,\mathrm{eV}$ and ![]() $T_e = 2\,\mathrm{eV}$ under the same electron density. Figure 14 illustrates the anticipated spectral lines of these ions, showing the individual lines of O II, O III, N II and N III, as well as the cumulative spectrum. The simulations assume the stated plasma conditions –

$T_e = 2\,\mathrm{eV}$ under the same electron density. Figure 14 illustrates the anticipated spectral lines of these ions, showing the individual lines of O II, O III, N II and N III, as well as the cumulative spectrum. The simulations assume the stated plasma conditions – ![]() $T_e = 1\,\mathrm{eV}$ (top panel) and

$T_e = 1\,\mathrm{eV}$ (top panel) and ![]() $T_e = 2\,\mathrm{eV}$ (bottom panel), with

$T_e = 2\,\mathrm{eV}$ (bottom panel), with ![]() $5 \times 10^{17}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ – consistent with the density range inferred from Hα and Hβ line profiles.

$5 \times 10^{17}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ – consistent with the density range inferred from Hα and Hβ line profiles.

Figure 14. Illustration of the expected spectral lines for O II, O III, N II, N III, C II, and C III at an electron density of ![]() $5 \times 10^{17}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$, with electron temperatures of 1 eV (top) and 2 eV (bottom), based on NIST database (Ref. 11).

$5 \times 10^{17}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$, with electron temperatures of 1 eV (top) and 2 eV (bottom), based on NIST database (Ref. 11).

To validate our experimental findings and theoretical expectations, we employed COMSOL Multiphysics (Ref. 30) to model plasma discharge within gas-filled capillaries. This simulation approach, detailed in our previous study, demonstrates strong agreement with both observed data and theoretical predictions (Ref. Reference Arjmand, Amato, Catalano, Manna, Mascali, Mauro, Oliva, Pappalardo, Pidatella, Suarez, Vinciguerra and Cirrone31).

Plasma-driven VHEE dosimetry

The integration of plasma diagnostics and LPA technologies aims to produce a stable, ultra-short, and high repetition rate suitable for VHEE (50–250 MeV) applications (Refs Reference Arjmand, Amato, Catalano, Cuttone, Manna, Oliva, Pappalardo, Petringa, Suarez, Vinciguerra and Cirrone5, Reference Labate, Palla, Panetta, Avella, Baffigi, Brandi, Di Martino, Fulgentini, Giulietti, Köster and Terzani6, Reference Whitmore, Mackay, van Herk, Jones and Jones7, Reference Arjmand, Amato, Catalano, Manna, Mascali, Mauro, Oliva, Pappalardo, Suarez and Vinciguerra8). These beams are particularly promising for medical applications, particularly in the treatment of deep-seated tumours through advanced radiation therapy (RT) techniques (Ref. Reference Labate, Palla, Panetta, Avella, Baffigi, Brandi, Di Martino, Fulgentini, Giulietti, Köster and Terzani6).

To assess the feasibility of VHEE beams in clinical settings, we performed Monte Carlo (MC) (Ref. 32) simulations using the Geant4 toolkit to evaluate the dose distributions from a 200 ± 25 MeV electron beam carrying 120 pC per bunch, generated by a capillary-based LPA system (Ref. Reference Lee, Kwon, Nam, Cho, Jang, Suk and Kim33). These electrons originate from a capillary-LPA system (Ref. Reference Lee, Kwon, Nam, Cho, Jang, Suk and Kim33) — specifically, a 7 mm capillary setup driven by a 150 TW, 25 fs (∼ 3 J) laser at the Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (GIST), which produced the desired beam parameters.

In contrast, our work employs the advanced I-LUCE platform featuring a 3 cm capillary. Despite this difference, the GIST laser parameters remain applicable and sufficient to reproduce clinically relevant VHEE beams using typical LPA conditions. We used this experimentally generated, capillary-driven electron beam as the source for our MC simulations, focusing on spatial dose profiles in water phantoms to assess both coverage and conformality. Ultimately, this analysis verifies the potential of LPA-generated VHEE beams to deliver therapeutic doses effectively in clinical scenarios.

Figure 15 illustrates the two-dimensional dose distribution (top panel) and the corresponding transverse dose profile (bottom panel) resulting from four electron beams (each transporting a charge of 120 pC) incident from four orthogonal directions. The average simulated dose per set of four shots resulted to be 0.28 Gy. If each shot can be released at 10 Hz we will have 28 Gy in one second.

Figure 15. 2D dose distribution of four electron beams (top), and line profile of four along the y axis of the dose distribution (bottom).

With the advent of emerging kHz laser systems, it is conceivable to achieve higher dose fractions in just 100 ms. While the development of high-repetition-rate plasma targets is still in its nascent stages, no fundamental barriers have been identified, and achieving kHz repetition rates appears feasible. Several facilities have already demonstrated the viability of such systems for high-repetition-rate applications (Ref. Reference Lee, Kwon, Nam, Cho, Jang, Suk and Kim33).

In the forthcoming second phase of the I-LUCE facility, plans are underway to upgrade the laser system to operate at 100 Hz, accompanied by enhancements in beam delivery capabilities. This advancement could pave the way for VHEE applications in RT, or ultra-high dose rate (UHDR) application known as FLASH-RT, where doses of ≥40 Gy are typically administered in less than one second.

Using the upgraded I-LUCE laser system and scaling the output to a beam with a 120 pC charge per shot, it is possible to reach dose levels suitable for delivery in the FLASH regime. In addition to increasing the laser’s repetition rate, enhancing the charge per electron bunch offers another avenue to achieve the desired dose rates. However, this approach must be balanced against potential challenges such as emittance growth and beam instabilities, which can affect beam quality.

These developments underscore the potential of LPA-driven VHEE beams to revolutionize cancer therapy, offering precise, high-dose treatments in remarkably short timeframes. The compact nature of LPA systems and their ability to deliver UHDRs make them promising candidates for clinical applications, particularly FLASH-RT.

Conclusion

To ensure precise spectral measurements for plasma diagnostics, we implemented wavelength calibration using Hg/Ne-Ar atomic emission lamps. Time-resolved spectroscopic techniques were employed to characterize the discharge plasmas, enabling the determination of electron density and temperature through SLB methods. Our analysis confirmed that Stark broadening, indicative of collisional interactions, is the dominant broadening mechanism, suggesting the presence of hot electrons within the plasma.