INTRODUCTION

Leadership remains one of the most researched phenomena in management research (e.g., Avolio, Walumbwa, & Weber, Reference Avolio, Walumbwa and Weber2009; Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester, & Lester, Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; van Knippenberg & Sitkin, Reference van Knippenberg and Sitkin2013). Although extensive research has probed into the distinct effects of different leadership styles and behaviors on followers and organizational outcomes, their relative importance and the mechanisms, through which they achieve their effects, remain poorly understood (see Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; Piccolo & Colquitt, Reference Piccolo and Colquitt2006; van Knippenberg & Sitkin, Reference van Knippenberg and Sitkin2013; Walumbwa, Avolio, & Zhu, Reference Walumbwa, Avolio and Zhu2008). Recently, different authors (e.g., Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; Schaubroeck, Shen, & Chong, Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017; van Knippenberg & Sitkin, Reference van Knippenberg and Sitkin2013) urged scholars to pay more attention to identifying the unique mediating mechanisms and assessing the relative importance of different leadership styles and behaviors. In this article, we address these issues in the context of Russia.

To understand the relative importance of widely practiced leadership styles and their psychological mechanisms is important for at least two reasons. First, research has noted that leaders can exhibit, or can be perceived by followers as exhibiting, different leadership behaviors depending on circumstances (Schuh, Zhang, & Tian, Reference Schuh, Zhang and Tian2013). For instance, Bass and Steidlmeier (Reference Bass and Steidlmeier1999) observed that it is unlikely that leaders exclusively engage in one particular type of leadership behavior all the time. The behavioral repertoires of most leaders go beyond one particular style and include a wider range of behaviors. Martin and Epitropaki (Reference Martin and Epitropaki2001) suggest that effective leaders are skilled tacticians who ‘are able to adjust their behaviors to individual group members’ (259). For instance, a leader can simultaneously and situationally stimulate intellectually his/her followers and inspire teamwork as well as be controlling and strict to a certain extent. Yet, despite several calls for integrative examinations of different leadership styles and behaviors (e.g., Casimir, Reference Casimir2001; De Cremer, Reference De Cremer2006; Hoch, Bommer, Dulebohn, & Wu, Reference Hoch, Bommer, Dulebohn and Wu2018) very few studies have addressed this issue (e.g., Schuh et al., Reference Schuh, Zhang and Tian2013).

Second, several theoretical perspectives on leadership such as the evolutionary approach (Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; Van Vugt, Hogan, & Kaiser, Reference Van Vugt, Hogan and Kaiser2008) or the implicit leadership theories (House, Dorfman, Javidan, Hanges, & de Luque, Reference House, Dorfman, Javidan, Hanges and de Luque2014; Offermann & Coats, Reference Offermann and Coats2018) acknowledge that the dominant styles of leadership in a particular society are likely to co-evolve with the society itself. Given the ongoing rapid transformation of many countries globally, due to, for example, internal socioeconomic and sociopolitical changes, increasing globalization, and technological changes, it is likely that leadership styles in these countries are also transforming, making different combinations of leadership behaviors possible. Moreover, also followers’ perceptions and expectations of leaders change and potentially become more heterogeneous (Epitropaki, Sy, Martin, Tram-Quon, & Topakas, Reference Epitropaki, Sy, Martin, Tram-Quon and Topakas2013; Ling, Chai, & Fang, Reference Ling, Chia and Fang2000; Offermann & Coats, Reference Offermann and Coats2018). In support, specifically in the Russian context, the focal context of this article, a range of different managerial styles has been found to coexist and be effective in organizations (Balabanova, Efendiev, Ehrnrooth, & Koveshnikov, Reference Balabanova, Efendiev, Ehrnrooth and Koveshnikov2015; Balabanova, Rebrov, & Koveshnikov, Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018). Furthermore, several researchers have claimed that since the 1990s the traditional control-oriented leadership style has been gradually replaced or complemented in Russia by more Westernized ones, such as, authoritative (e.g., Fey, Adaeva, & Vitkovskaia, Reference Fey, Adaeva and Vitkovskaia2001; Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries2000; McCarthy, Puffer, & Darda, Reference McCarthy, Puffer and Darda2010). Thus, we need a better understanding of the interplay between different leadership behaviors in order to evaluate their unique effects on employees.

In this article, we focus on three leadership styles that are widely practiced and influential in many countries around the world, and which represent three key aspects of leadership – charisma, benevolence, and authority. Respectively, the focal styles are transformational (e.g., Avolio et al., Reference Avolio, Walumbwa and Weber2009; Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen, & Lowe, Reference Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen and Lowe2009; van Knippenberg & Sitkin, Reference van Knippenberg and Sitkin2013), paternalistic (Aycan et al., Reference Aycan, Kanungo, Mendonca, Yu, Deller, Stahl and Kurshid2000; Aycan, Reference Aycan, Yang, Hwang and Kim2006; Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2008; Chen, Eberly, Chiang, Farh, & Cheng, Reference Chen, Eberly, Chiang, Farh and Cheng2014), and authoritarian (see Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000; Farh, Cheng, Chou, & Chu, Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou, Chu, Tsui, Bian and Cheng2006; Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017). Drawing on job demand resource (JDR) theory (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007), we theorize and examine how these styles – when perceived by followers – impact on followers’ work engagement and via what psychological mechanisms. More specifically, drawing on JDR theory, we differentiate between three mediating mechanisms, namely followers’ self-efficacy, self-esteem, and job control. We define self-efficacy as the perceived ability to do whatever is required to perform successfully one's job (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977). Self-esteem is ‘the perceived self-value that individuals have of themselves as organizational members acting within an organizational context’ (Pierce, Gardner, Cummings, & Dunham, Reference Pierce, Gardner, Cummings and Dunham1989: 625). Job control is one's perceived ability to influence what happens in the work environment around one's job-related tasks (van Yperen & Hagedoorn, Reference van Yperen and Hagedoorn2003).

In order to control for cultural context, we examine the three styles in the context of Russia, more specifically, among white-collar employees in Russian domestic organizations. We believe that Russia offers a suitable context for our study due to its cultural, socioeconomic, and institutional specifics, all three leadership styles representing the three focal aspects of leadership, namely charisma, benevolence, and authority, were shown to be present and influential in Russian organizations (see Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Efendiev, Ehrnrooth and Koveshnikov2015). Transformational leadership was found to be effective in facilitating organizational performance (Elenkov, Reference Elenkov2002) and organizational identification (Koveshnikov & Ehrnrooth, Reference Koveshnikov and Ehrnrooth2018). Paternalistic leadership has been declared an enduring and fundamental feature of many leader–employee relationships in Russia (Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Efendiev, Ehrnrooth and Koveshnikov2015; Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries2001; Puffer, Reference Puffer1994). Finally, with some empirical support research showed that authoritarian leadership style, ‘in which loyalty is exchanged for freedom from accountability’, is still efficient in modern Russia (Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018; Fey et al., Reference Fey, Adaeva and Vitkovskaia2001; McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood, & Stewart Jr, Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008: 226).

A possible reason for the diversity of leadership styles in Russia can be the rapid socioeconomic and sociopolitical transformations that have occurred in Russia in recent decades (for a more detailed description see the next section). These processes influenced Russian followers in different ways and hence diversified their implicit leadership theories, i.e. the cognitive structures and/or prototypes that shape followers’ perceptions of leaders’ behaviors and specify traits and behaviors that followers expect from leaders (Epitropaki et al., Reference Epitropaki, Sy, Martin, Tram-Quon and Topakas2013; Ling et al., Reference Ling, Chia and Fang2000; Offermann & Coats, Reference Offermann and Coats2018). Thus, whereas we know that the three styles can be efficient in facilitating important organizational and employee outcomes in Russian organizations, our knowledge of their relative importance and the mediating mechanisms, through which they operate on employees, remains limited. Against this background, in this study, we pose two research questions. The first one concerns the relative importance of transformational, paternalistic, and authoritarian leadership styles for employees’ work engagement. The second one addresses whether followers’ self-efficacy, self-esteem and/or job control mediate the relationships between the three styles and employees’ work engagement.

Based on our analysis of 403 white-collar employees in Russian domestic organizations, we find all three styles to affect employees’ work engagement positively, with transformational leadership exhibiting the strongest effect. We also find interesting and theoretically justifiable differences in how the three mediating mechanisms affect the relationships between the leadership styles and work engagement: self-esteem appears to be a relatively more important mediating mechanism for transformational, self-efficacy for authoritarian, and job control for paternalistic leadership.

The study makes three contributions to the leadership literature. First, it examines the three leadership styles’ associations with employee's work engagement and the mediating mechanisms through which these associations operate. In this way, we increase our understanding of the relative importance of the three leadership styles, their differential effects and interrelations, and the different mechanisms through which they affect followers (e.g., DeRue, Nahrgang, Wellman, & Humphrey, Reference Derue, Nahrgang, Wellman and Humphrey2011; Hoch et al., Reference Hoch, Bommer, Dulebohn and Wu2018). Second, we offer a theoretical explanation and empirical evidence for the positive influences of authoritarian and paternalistic leadership styles. By doing so, we add to our still limited and inconclusive understanding of how these two styles operate on followers (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000; Farh et al., Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou, Chu, Tsui, Bian and Cheng2006; Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2008; Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017; Wu, Huang, Li, & Liu, Reference Wu, Huang, Li and Liu2012; Zhang & Xie, Reference Zhang and Xie2017). Finally, and more generally, focusing on the three leadership styles’ influences in Russian organizations allows us to bridge the research gap in global knowledge concerning the generalizability of different leadership theories (see Liden, 2012; Yang, Zhang, & Tsui, Reference Yang, Zhang and Tsui2010) created by the fact that most leadership research and theories have been developed and tested within Western contexts. Further, both authoritarian and paternalistic leadership styles have been emphasized as very much indigenous leadership styles. In this way, our research also concurs with a growing interest in indigenous leadership research (e.g., Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Fu, Xi, Li, Xu, Cao, Li, Ma and Ge2012; Zhang, Chen, & Ang, Reference Zhang, Chen and Ang2014) and leadership research in non-Western cultural contexts (see Avolio et al., Reference Avolio, Walumbwa and Weber2009; Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018; Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017; Walumbwa, Lawler, & Avolio, Reference Walumbwa, Lawler and Avolio2007).

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Research Context

Russia offers a fascinating context in which to examine different leadership styles, their relative importance and influences on followers. Historically, Russian management has been portrayed as a successor of the Soviet managerial approach. Russian managers were depicted as directive, control-oriented, and authoritarian (see Fey & Denison, Reference Fey and Denison2003; Puffer, Reference Puffer1994). Russian organizations were characterized by the high concentration of power, rigid hierarchies, the omnipresent use of coercive power, low employee participation and involvement, and the high importance of rank and status (e.g., Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries2001; McCarthy, Puffer, Vikhanski, & Naumov, Reference McCarthy, Puffer, Vikhanski and Naumov2005; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008). These characteristics have predetermined the prevalence of authoritarian leadership among Russian leaders (Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries2001).

However, over the last 30 years, Russia has gone through several socioeconomic and sociopolitical developments and transformations: starting with the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991; through to the period of Wild Capitalism of the 1990s and the economic crisis of 1998; to the prosperous 2000s; and finally, the Ukrainian conflict and the Western-imposed economic sanctions. Over these years, at least until recently, Russian businesses and the Russian business culture was slowly moving toward Western standards and ways of doing business yet at the same time preserving some of its key traditions and cultural attributes rooted in the traditionally high power distance between superiors and subordinates and the generally high uncertainty avoidance (Naumov & Puffer, Reference Naumov and Puffer2000). These processes had an important influence on the development of leadership and leadership styles in Russian business organizations.

The evolution of Russian leadership styles has been noted by several authors in the past (e.g., Fey et al., Reference Fey, Adaeva and Vitkovskaia2001; Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries2000; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer and Darda2010). These authors argued that since the collapse of the Soviet Union the expectations of Russian employees toward leadership have evolved and to be effective Russian managers were advised to rely on authoritative leadership style. Authoritative leaders are the ones who ‘provide clear vision, facilitate empowerment … foster openness and teamwork, exercise discipline and control by providing clear boundaries, give support, and create a sense of security’ (Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries2000: 77). Moreover, since the 1990s, Russian leadership has also evolved toward heterogeneity. As several recent studies show (e.g., Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Efendiev, Ehrnrooth and Koveshnikov2015, Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018), a range of different leadership styles coexist today in Russian business organizations. The studies indicate that instead of relying on the over-simplistic view that since 1991 Russian management has evolved in a steady, linear manner from the traditional authoritarian toward a more Westernized transformational or authoritative style, a more realistic view is that contemporary Russian management situationally combines and exhibits a range of leadership behaviors pertinent to different leadership styles.

Several typologies of contemporary Russian managers’ leadership orientations and behaviors have been proposed (e.g., Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Efendiev, Ehrnrooth and Koveshnikov2015, Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018; Fey et al., Reference Fey, Adaeva and Vitkovskaia2001). They point toward a diversity of leadership behaviors co-existing in contemporary Russian organizations. For instance, Balabanova et al.’s (Reference Balabanova, Efendiev, Ehrnrooth and Koveshnikov2015) study shows that leadership orientations among Russian managers tend to vary depending on the region and industry in which they operate and on these managers’ gender. Furthermore, Astakhova, DuVois, and Hogue (Reference Astakhova, DuBois and Hogue2010) conceptually argued that Russian managers are likely to possess different leadership orientations depending on whether they are younger or older than 40 years old. Belonging to a post-Soviet generation, the younger managers are likely to be more Westernized in their leadership behaviors and cultural values as compared to their more senior colleagues, who are more likely to rely on control-oriented leadership behaviors. Similarly, in their book on Russian leaders, Kets de Vries and colleagues (2005) distinguish between ‘Russian’ Russian leaders, who are keen on building traditional, ‘100 percent Russian organizations’ (xiv), and ‘Global’ Russian leaders, who adopt more Western ways of management and leadership.

Pointing toward the heterogeneity of leadership behaviors co-existing in contemporary Russia, the extant studies also show that many of these diverse leadership behaviors result in positive employee and organizational outcomes. It suggests that followers in contemporary Russia are perceptive toward a range of leadership behaviors comprising control-oriented and authoritarian as well as more paternalistic, and in some cases transformational behaviors. Altogether, this review underscores the existence and relevance of the three focal leadership styles examined in this article for contemporary employees and business organizations in Russia.

Leadership Styles and the JDR Model

Amongst numerous leadership styles, transformational, paternalistic, and authoritarian leadership styles appear to draw particularly high interest from scholars (Avolio et al., Reference Avolio, Walumbwa and Weber2009; Aycan, Reference Aycan, Yang, Hwang and Kim2006; Aycan et al., Reference Aycan, Kanungo, Mendonca, Yu, Deller, Stahl and Kurshid2000; Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000; Farh et al., Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou, Chu, Tsui, Bian and Cheng2006; Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; Kirkman et al., Reference Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen and Lowe2009; Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2008; van Knippenberg & Sitkin, Reference van Knippenberg and Sitkin2013; Wang & Howell, Reference Wang and Howell2010; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang, Li and Liu2012; Zhang & Xie, Reference Zhang and Xie2017). As mentioned above, they represent three key aspects of leadership – charisma, benevolence, and authority, respectively.

Transformational leadership is a leadership approach, which transforms the values and priorities of followers and motivates them to perform beyond their expectations (Yukl, Reference Yukl2006). It comprises four related behaviors labeled core transformational leadership behavior or idealized influence, inspirational motivation or high performance expectations, individualized consideration or supportive leadership, and intellectual stimulation (e.g., Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Bommer, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Bommer1996; Richardson & Vandenberg, Reference Richardson and Vandenberg2005). It has been widely studied in Western contexts (Avolio et al., Reference Avolio, Walumbwa and Weber2009) and shown to affect a wide range of employee outcomes such as engagement, well-being, self-efficacy, and self-esteem (Kark, Shamir, & Chen, Reference Kark, Shamir and Chen2003; Kelloway, Turner, Barling, & Loughlin, Reference Kelloway, Turner, Barling and Loughlin2012; Nielsen & Munir, Reference Nielsen and Munir2009). In non-Western contexts, evidence concerning the effects of transformational leadership remains limited, albeit with a few exceptions (Elenkov, Reference Elenkov2002; Koveshnikov & Ehrnrooth, Reference Koveshnikov and Ehrnrooth2018).

Authoritarian leadership refers to ‘a leader's behavior of asserting strong authority and control over subordinates and demanding unquestioned obedience from them’ (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014: 799). This style is relatively less researched compared to transformational leadership. However, in certain cultures around the world characterized by high power distance and/or collectivism its prevalence and importance has been recognized (see Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008; Zhang & Xie, Reference Zhang and Xie2017). Whereas in Western contexts, authoritarian leadership was shown to exhibit mainly negative effects, for example a decrease in follower commitment and effort (House et al., Reference House, Dorfman, Javidan, Hanges and de Luque2014) and an increase in burnout (De Hoogh & Den Hartog, Reference De Hoogh and Den Hartog2009), in high power distance, mainly non-Western, cultures, more positive effects have been discussed and discovered. For instance, Balabanova et al. (Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018) argued that in Russia with its high power distance culture (Naumov & Puffer, Reference Naumov and Puffer2000) to encourage followers to look beyond their self-interest for a common good, leaders need to be authoritarian. Others (e.g., Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang, & Farh, Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004; Farh et al., Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou, Chu, Tsui, Bian and Cheng2006) suggested that in China authoritarian leadership instills followers with gratitude toward their leaders and increases compliance. Recently, Wang and Guan (Reference Wang and Guan2018) found authoritarian leadership to increase employee performance, mediated by their learning goal orientation, in Chinese organizations.

Paternalistic leadership is a leadership style whereby a leader takes a personal interest in the follower's off-the-job lives and attempts to promote the follower's personal welfare by assuming the role of a parent and considering it an obligation to provide protection to the follower under his/her care (Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2006). Research suggests that paternalistic leadership is likely to influence organizational performance and employee attitudes in many business cultures (although mainly non-Western ones), such as the Middle East, Pacific Asia, and Latin America (e.g., Aycan et al., Reference Aycan, Kanungo, Mendonca, Yu, Deller, Stahl and Kurshid2000; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Farh et al., Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou, Chu, Tsui, Bian and Cheng2006; Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2006, 2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang, Li and Liu2012). Evidence exists that in Western contexts also paternalistic leadership maybe more present than is usually assumed. For instance, in a rare cross-cultural study, Aycan et al. (Reference Aycan, Kanungo, Mendonca, Yu, Deller, Stahl and Kurshid2000) found that employees in China, Pakistan, India, Turkey, and the USA reported higher levels of paternalistic practices compared to their colleagues in Canada, Germany, and Israel. At the same time, some scholars have noted the widespread (mainly in the West) negative attitude toward paternalistic leadership.

Given the extant knowledge about the three leadership styles, we still know little concerning their relative importance in influencing employee outcomes. Moreover, we have limited understanding of the mechanisms through which the three operate on followers. Meanwhile, research suggests that the styles can be quite different but complementary in their effects. For instance, Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004) found paternalistic leadership to account for additional variance over transformational leadership in explaining a number of employee attitudes thus indicating that it has a unique explanatory power. At this stage, it is also important to note that previous research has considered authoritarian leadership to constitute one of the behavioral dimensions of paternalistic leadership (see Cheng, Chou, & Farh, Reference Cheng, Chou and Farh2000; Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2006, 2008). However, rather extensive evidence indicates that authoritarian behavior is very different from other behaviors commonly included into the concept of paternalistic leadership such as benevolent and moral leadership (see Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004; Niu, Wang, & Cheng, Reference Niu, Wang and Cheng2009; Chan, Huang, Snape, & Lam, Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Chen, Yang, & Jing, Reference Chen, Yang and Jing2015). Recently, Harms et al. (2018: 117) advocated the need to examine the unique effects of authoritarian leadership by identifying and focusing on its core elements not conflated with any other leadership behaviors or measures. Therefore, in this study, we treat authoritarian leadership behavior as distinctively different from other dimensions of paternalistic leadership.

In what follows, we theorize the relative importance of the three styles in relation to employee work engagement and the psychological mechanisms that mediate these relationships. More concretely, we draw on JDR theory (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007; Demerouti & Bakker, Reference Demerouti and Bakker2011), which posits that in every occupation there are job-related factors, which can be classified as either job demands or job resources both with implications for work engagement. The former refers to those physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require physical or psychological effort or skills to deal with it which may or may not negatively influence work engagement. In contrast, job resources, our focus in this study, are those physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are functional in achieving job goals, reducing job demands, and stimulating personal growth, learning and development. Job resources have a motivational role for employees with potentially positive effects on work engagement. The resources can be either extrinsic, whereby job resources are instrumental in helping employees to achieve their work goals, or intrinsic, whereby job resources foster employees’ growth, learning and development.

Perceived job control has been conceived as a job resource, fostered extrinsically by social support and feedback from supervisors (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007; Schreurs, Van Emmerik, Notelaers, & De Witte, Reference Schreurs, Van Emmerik, Notelaers and De Witte2010). It was shown to reduce the detrimental effects of work stress on employees (Schaubroeck & Merritt, Reference Schaubroeck and Merritt1997) and increase their job-related performance (Schaubroeck & Fink, Reference Schaubroeck and Fink1998). Self-efficacy and self-esteem have been conceived as intrinsically motivating personal job resources linked with employees’ growth and development, and positively affecting employees’ performance (Luchman & González-Morales, Reference Luchman and González-Morales2013; Schreurs et al., Reference Schreurs, Van Emmerik, Notelaers and De Witte2010) and work engagement (Simbula, Guglielmi, & Schaufeli, Reference Simbula, Guglielmi and Schaufeli2011; Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, Reference Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti and Schaufeli2009). Therefore, given the importance of the three job resources for employees’ work-related outcomes, in this study, we theorize and examine the mediating effects of job control, self-efficacy, and self-esteem as three job resources provided by leaders to their followers. Overall, using JDR theory allows us to theorize the respective influences of the three focal leadership styles on followers’ work engagement as being accomplished through either intrinsically or extrinsically (or both) motivating psychological job resources that the focal styles enhance. We now turn to deriving our hypotheses.

Transformational Leadership and Employee Work Engagement

Transformational leadership puts a lot of emphasis on the symbolic aspects of leaders’ behavior, such as providing a compelling vision, inspirational messages, emotional support and encouragement, and intellectual stimulation (see Bass, Reference Bass1985, Reference Bass1998). In these ways, it infuses work and organizations with meaningfulness, purpose and commitment. Perceiving one's work as meaningful and purposeful is likely to increase the emotional commitment and work engagement of followers (see Piccolo & Colquitt, Reference Piccolo and Colquitt2006; Wang, Law, Hackett, Wang, & Chen, Reference Wang, Law, Hackett, Wang and Chen2005). We argue that the mechanisms through which it happens involve the ability of transformational leaders to (a) enhance followers’ self-concept comprising their self-efficacy and self-esteem and (b) make followers feel in control of their job-related tasks. In terms of the JDR model, all of these are psychological resources with which transformational leaders provide their followers.

Starting with followers’ self-concept, in their pioneering work, Shamir and colleagues (e.g., Kark & Shamir, Reference Kark and Shamir2002; Shamir, House, & Arthur, Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993; Shamir, Zakay, Breinin, & Popper, Reference Shamir, Zakay, Breinin and Popper1998, 2000) argued that followers are likely to achieve high levels of both self-esteem and self-efficacy through their interactions with transformational leaders. First, the positive effect on followers’ self-efficacy stems from the ability of transformational leaders to make their followers feel good about themselves and their abilities. Such leaders continuously emphasize positive visions of the future, communicate high performance expectations, and propagate their confidence in followers’ abilities to accomplish tasks and contribute to the organization (Avolio et al., Reference Avolio, Zhu, Koh and Puja2004). Kahai, Sosik, and Avolio (Reference Kahai, Sosik and Avolio1997) suggest that transformational leaders increase followers’ self-efficacy by engaging them in problem solving relevant for their organizations. By consulting followers and encouraging them to come up with ideas for solutions, transformational leaders enhance followers’ beliefs in their own abilities and minimize the sense of helplessness (see Mulki, Jaramillo, & Locander, Reference Mulki, Jaramillo and Locander2006). Other mechanisms through which transformational leaders can influence followers’ self-efficacy are regular feedback and performance appraisal (e.g., Kirkpatrick & Locke, Reference Kirkpatrick and Locke1996). Providing constructive and encouraging feedback can strengthen followers’ self-confidence and thus increase their self-opinions.

Second, Shamir et al. (Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993) also proposed that transformational leadership is likely to enhance followers’ self-esteem. They hypothesized that transformational leaders can transform followers’ self-concept from being self-oriented to being more oriented toward a collective goal, mission and vision and convince followers to equate their personal values with those of the organization. In these ways, transformational leaders influence followers’ self-esteem. The mechanism through which it happens relates to followers’ empowerment through their identification with a bigger and stronger entity, that is, the organizational unit, the values of which they embrace and internalize as their own. Social identity theory (Tajfel, 1982) stipulates a close link between an individual's self-esteem and identification with the group. Individuals tend to base their self-esteem at least partly on their belonging to the group and experiencing group successes and failures as their personal ones. Such identification with the group is often associated with the attribution of positive qualities to the group and increases the self-esteem of its members. Based on this argumentation, Kark et al. (Reference Kark, Shamir and Chen2003) argued and empirically confirmed that transformational leadership enhances followers’ identification with the organizational unit / group. The identification then ultimately empowers followers by connecting them to a bigger and stronger entity, i.e. the organizational unit, increasing their sense of self-worth and self-esteem (see also Shamir et al., Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993, 1998).

Having considered the influence of transformational leadership on followers’ self-concept, Shamir et al. (Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993) then theorized that self-esteem and self-efficacy, as the expressions of followers’ self-concept, could act as possible mediators between transformational leadership and followers’ performance. A mechanism through which this relationship operates is self-engagement. This is then argued to add to the followers’ commitment to a course of action or a task execution (Bono & Judge, Reference Bono and Judge2003; Shamir et al., Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993). In this way, followers who perceive their work as being congruent with their own goals and motives and who perceive themselves as belonging to their organizational unit and workgroup are likely to feel more psychologically resourceful and ultimately more self-satisfied, self-confident and intrinsically motivated (cf. Zhang & Bartol, Reference Zhang and Bartol2010). Taken together, we foresee that the effects of transformational leadership on followers’ work engagement will be mediated by followers’ self-esteem and self-efficacy. Hence, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: Controlling for the effects of authoritarian and paternalistic leadership styles, transformational leadership will be positively associated with followers’ work engagement.

Hypothesis 1b: Followers’ self-efficacy will mediate positively the association between transformational leadership and followers’ work engagement.

Hypothesis 1c: Followers’ self-esteem will mediate positively the association between transformational leadership and followers’ work engagement.

As for the mediating role of perceived job control in the relationship between transformational leadership and follower work engagement, the extant literature offers several arguments to support the idea that transformational leaders can make followers feel more in control of their job-related tasks and hence increase followers’ work engagement. First, and most importantly, transformational leaders enhance the sense of freedom and autonomy among followers motivating them to take charge and be proactive in relation to their job tasks (Den Hartog & Belschak, Reference Den Hartog and Belschak2012). Such leaders stimulate followers to seek new ways to perform their tasks (Piccolo & Colquitt, Reference Piccolo and Colquitt2006). In addition, research shows that through their leadership behaviors transformational leaders can reframe stressful job tasks as opportunities for growth rather than mere sources of stress (Sosik & Godshalk, Reference Sosik and Godshalk2000). They also enhance followers’ task-related self-confidence and social support perceptions (Lyons & Schneider, Reference Lyons and Schneider2009; Shamir et al., Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993). Finally, on the emotional side, such leaders were found to lower work-related stress and emotional exhaustion (Avolio, Zhu, Koh, & Puja, Reference Avolio, Zhu, Koh and Puja2004) and generate positive emotions among their followers about their job-related tasks (Bono, Foldes, Vinson, & Muros, Reference Bono, Foldes, Vinson and Muros2007; Lyons & Schneider, Reference Lyons and Schneider2009). Thus, taken together this evidence suggests that transformational leadership is likely to facilitate positively followers’ work engagement by also increasing their perceived job control. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1d: Followers’ perceived job control will mediate positively the association between transformational leadership and followers’ work engagement.

Authoritarian Leadership and Employee Work Engagement

Despite the negative image that authoritarian leadership has acquired in Western literature (e.g., Aryee, Chen, Sun, & Debrah, Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007) in which it is often associated with such figures as Hitler, Franco, and others, it has to be acknowledged that empirical studies of authoritarian leadership in organizations are rare. As such, authoritarian leadership is usually attributed to high power distance societies where members appreciate, admire and submit to strong authority (e.g., Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018; Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008). However, empirical evidence for the effects of authoritarian leadership on followers has so far been mixed.

Several extant studies found the effects of authoritarian leadership to be negative, e.g. for followers’ extra-role performance (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Zhang & Xie, Reference Zhang and Xie2017), organizational citizenship behavior (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013), voice (Li & Sun, Reference Li and Sun2015), and group creativity (Zhang, Tsui, & Wang, Reference Zhang, Tsui and Wang2011). Yet, several authors argued that it is too early to state, based on these results, that authoritarian leadership has only negative influences on followers (e.g. Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017). Recently, research offered some evidence of positive effects of authoritarian leadership on employee innovative behaviors (Tian & Sanchez, Reference Tian and Sanchez2017), psychological safety (De Hoogh, Greer, & Den Hartog, Reference De Hoogh, Greer and Den Hartog2015), and performance specifically among followers with high learning goal orientations (Wang & Guan, Reference Wang and Guan2018). Further, Balabanova et al. (Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018) documented the positive impact of authoritarian leaders on their companies’ performance (see also Huang, Xu, Chiu, Lam, & Farh, Reference Huang, Xu, Chiu, Lam and Farh2015).

Indeed, we anticipate that under the conditions of high uncertainty avoidance and high power distance, followers might experience and react to authoritarian leadership positively with increased work engagement, mainly for two reasons. First, they may experience their leaders’ expectations to make decisions on their behalf and provide detailed guidance concerning what to do and how, as an important psychological resource, as per the JDR model. It is then likely to decrease their anxiety and uncertainty related to their ability to fulfill their role and the necessity to make decisions (see Dorfman et al., Reference Dorfman, Howell, Hibino, Lee, Tate and Bautista1997; Rast, 2015; Wang & Guan, Reference Wang and Guan2018). For instance, Chen, Zhang, and Wang (Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014) found management control to enhance the effects of supervisors’ power sharing on employees’ psychological empowerment in China. Additionally, followers may also appreciate their leaders to assume responsibility for results and thus free them from accountability (Fey et al., Reference Fey, Adaeva and Vitkovskaia2001; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008). Provided with clear guidance to follow and bearing less responsibility and accountability, followers under authoritarian leaders, ironically, might feel more intrinsically empowered and motivated to accomplish their tasks, mainly through increased self-efficacy.

Second, authoritarian leadership can increase followers’ psychological resources through a mechanism known as leaders’ mood contagion (see Bono & Ilies, Reference Bono and Ilies2006; Sy, Cote, & Saveedra, Reference Sy, Côté and Saavedra2005) and by enhancing their sense of identity as group members (Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017). Research found a link between leaders' moods, the moods of their followers and the followers’ performance (Sy et al., Reference Sy, Côté and Saavedra2005). More importantly, Fredrickson (Reference Fredrickson, Cameron, Dutton and Quinn2003) suggests that the extent of leaders’ mood contagion depends on the power hierarchy differential between leaders and followers. It means that leaders’ mood contagion is more likely for an authoritarian leader – follower relationship characterized by high power distance than for other types of leader – follower relationships. Powerful authoritarian leaders are likely to provide a clearer, more unambiguous and powerful prototype to follow and identify with for their followers (Rast et al., 2013). In this way, followers are likely to be attracted to the certainty and strength projected by authoritarian leaders and ‘contaminated’ by the self-efficacy and self-esteem that such leaders exude (Wang & Guan, Reference Wang and Guan2018).

However, we do not expect authoritarian leadership to be particularly conducive to followers’ job control. Given the authoritarian leaders’ demand of obedience and strict control, followers, who might feel at the same time more self-efficacious and better about their self-esteem, are not likely to feel independent and entrepreneurial in executing their job-related tasks but become dependent on and expecting leaders’ guidance and orders when doing their jobs. For instance, authoritarian leadership was shown to decrease followers’ job-related role clarity (Zhang & Xie, Reference Zhang and Xie2017) and group creativity (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Tsui and Wang2011).

Therefore, the authoritarian leaders’ demands of obedience, clear, and unambiguous behavioral guidelines and behavioral prototypes to follow and identify with, and the projected sense of order and discipline are likely to motivate followers to become more work engaged. It is likely to do so by making followers feel psychologically more empowered and enhancing their self-esteem and self-efficacy in terms of their perceived abilities and self-confidence in relation to achieving their job-related goals (see Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; De Hoogh et al., Reference De Hoogh, Greer and Den Hartog2015). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2a: Controlling for the effects of transformational and paternalistic leadership styles, authoritarian leadership will be positively associated with followers’ work engagement.

Hypothesis 2b: Followers’ self-efficacy will mediate positively the association between authoritarian leadership and followers’ work engagement.

Hypothesis 2c: Followers’ self-esteem will mediate positively the association between authoritarian leadership and followers’ work engagement.

Paternalistic Leadership and Employee Work Engagement

The paternalistic leadership relationship is the one in which followers willingly reciprocate the care and protection of paternal authority by showing conformity (see Aycan et al., Reference Aycan, Kanungo, Mendonca, Yu, Deller, Stahl and Kurshid2000; Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2006). Kets de Vries argued that ‘[p]aternalism can be a great source of strength, because it makes for interdependence, security and safety’ (2000: 78; cf. Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2008). In support, empirical studies in several contexts, for example China and Turkey, have shown that paternalistic leadership predicts employee job attitudes and performance (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004; Farh et al., Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou, Chu, Tsui, Bian and Cheng2006; Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2006; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang, Li and Liu2012). In similarity with transformational leaders, paternalistic leaders also induce emotional reactions from followers. These are related to admiration, respect, liking, gratitude, and, possibly, fear. Additionally, paternalistic leaders are very concerned with their followers’ both work-related and personal welfare (Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2006; Pellegrini, Scandura, & Jayaraman, Reference Pellegrini, Scandura and Jayaraman2010).

To explain the positive effects of paternalistic leadership, research usually notes that people are generally motivated to reciprocate beneficial behaviors based on the sense of indebtedness and felt obligations toward the person providing them. Such exchanges, if reciprocated appropriately, are assumed to create trust between the parties. When a leader provides continuous care and shows concern for followers’ jobs and personal life-related wellbeing, the followers are likely to develop warm feelings and confidence toward the leader thus forming an emotional bond and facilitating affective trust (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004). In support, several studies (Wasti, Tan, & Erdil, Reference Wasti, Tan and Erdil2011; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang, Li and Liu2012) found benevolent paternalistic leadership to be effective in building trust between leaders and followers. Such trust in turn represents a psychological resource, which, in line with the JDR model, can imbue followers with a strong sense of reciprocity to their leaders by sharing and expressing their ideas and concerns without fear of reprimand. In support, research has found paternalistic leadership to affect positively followers’ in-role and extra-role performance (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014) and job satisfaction (Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2006). Thus, paternalistic leadership is also likely to increase followers’ work engagement.

Based on extant literature, we suggest that the mechanisms through which paternalistic leadership is likely to increase followers’ work engagement are twofold. The first one relates to enhanced followers’ perceived job control. Research shows that paternalistic leaders imbue followers with a sense of confidence in that they can trust that the leader will support and care for them while they perform their job-related tasks and will help them if they encounter difficulties in the work setting but also beyond it (Niu et al., Reference Niu, Wang and Cheng2009). In this way, followers perceive higher control over their job-related tasks because they feel less vulnerable and do not fear punishment in case something goes wrong (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014). The second mechanism concerns the ability of paternalistic leaders through their leadership behaviors to make followers perceive themselves as valuable organizational members (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014). Drawing on the idea that leadership behaviors transmit information, which followers use to make self-evaluations, Zhang, Huai, and Xie (Reference Zhang, Huai and Xie2015) showed that paternalistic leadership enhances followers’ self-evaluations in the form of status judgments, which are followers’ autonomous judgments about whether their contributions to the organization are recognized and whether their supervisors value them. Paternalistic leaders’ care and protection signals to followers that they are valuable organizational members and leaders are willing to devote time and energy in caring for them (see Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013). This is likely to boost followers’ perceptions of their self-esteem, that is, their perceived value to the organization and the importance of their contributions.

However, we do not expect paternalistic leadership to affect positively followers’ self-efficacy. To the best of our knowledge, no research has directly examined the relationship between leader paternalism and follower self-efficacy. Although, we hypothesized its positive influence on followers’ self-esteem, at the same time, research shows that paternalistic leadership can be associated with excessive leader dependency and learned helplessness (Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries2000; Pellegrini et al., Reference Pellegrini, Scandura and Jayaraman2010), which is not likely to enhance followers’ self-engagement and/or self-confidence in their abilities to independently cope with situations at work. Instead, as discussed earlier, through their trust and care, paternalistic leaders will make followers more resourceful by providing them with the feeling of extrinsic security and care as well as the self-perception of being a valuable organizational member. Therefore, we expect paternalistic leadership to facilitate followers’ work engagement mainly through increased perceived job control and (organization-based) self-esteem stemming from the mutual trust between followers and leaders.

Hypothesis 3a: Controlling for the effects of transformational and authoritarian leadership styles, paternalistic leadership will be positively associated with followers’ work engagement.

Hypothesis 3b: Followers’ job control will mediate positively the association between paternalistic leadership and followers’ work engagement.

Hypothesis 3c: Followers’ self-esteem will mediate positively the association between paternalistic leadership and followers’ work engagement.

METHODS

Participants

The data for the study was obtained from a large-scale project on the influence of various leadership styles and HRM practices on employee attitudes in Russian organizations. We surveyed white-collar employees in 232 organizations located in Moscow and St Petersburg and operating in five industries, namely food processing, machine building, construction, metals, and finance. The data was gathered in the first half of 2014 using a telephone survey, which was administered by a professional data collection agency located in Russia.

We developed the survey instrument from scratch and the agency used its network of contacts and personnel resources to conduct the actual survey in Russian. The original questionnaire was developed in English using validated constructs from top ranked Western management journals. It was translated into Russian and then back-translated into English by two professional translators. The back-translated version was checked for any discrepancies by the authors. The Russian version of the instrument was then pre-tested on five Russian native speakers living and working in Russia to identify any confusing or ambiguous phrases or concepts. After that, the questionnaire was sent to the agency to be used for data collection. It took on average around 30 minutes for respondents to complete.

Altogether 965 employees were contacted during their working hours and 403 agreed to participate in the survey for a small financial remuneration (1.74 employees per organization). Thus, the obtained response rate was around 42%. The average age of respondents was 36.3 (SD = 9.9) and their average working hours per week was 41.3 (SD = 6.0). 35% were male and the respondents were equally divided between Moscow and St Petersburg (50% each).

Measures

For all measures, we used a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1’ = ‘Strongly disagree’ to ‘5’ = ‘Strongly agree’.

Independent variables

To measure the three leadership styles, we asked the respondents to evaluate their immediate, proximal leaders, i.e., their team leaders, who represented the organizations’ middle-level management. Transformational leadership was measured using a construct originally developed by Podsakoff and colleagues (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, & Fetter, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman and Fetter1990; Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Bommer1996). The items were adopted from a shortened version of Podsakoff's original measure as it was used in previous research (e.g., MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Rich, Reference MacKenzie, Podsakoff and Rich2001; Kirkman et al., Reference Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen and Lowe2009). The construct includes four transformational behaviors: core transformational leadership (three items), supportive leadership (two items), intellectual stimulation (two items), and high performance expectations (two items). As the measure was developed in a Western context, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to verify its applicability in the Russian context. After CFAs, four items with low loadings were removed from the construct. Cronbach's alpha of the remaining five items was 0.80. Paternalistic leadership was measured using the four best loading items in Pellegrini and Scandura (Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2006) (α = 0.86). Authoritarian leadership was measured using the three best loading items in Cheng, Chou, and Farh (Reference Cheng, Chou and Farh2000) and Sheer (Reference Sheer2010) (α =0.70). All items used in the study are listed in Appendix I.

Mediating variables

Self-esteem was measured using a three-item construct adopted from Pierce et al. (Reference Pierce, Gardner, Cummings and Dunham1989) (α = 0.83) and self-efficacy using the three best loading items in Riggs and Knight (Reference Riggs and Knight1994) (α = 0.74). The job control measure was adopted from Yperen and Hagedoorn (2003) and six items were chosen based on the best factor loadings in Jackson, Wall, Martin, and Davids (1993) (α =0.87).

Dependent variable

Work engagement was measured using a shortened version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) developed and validated in Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova (Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006). It consists of nine items measuring vigor (three items), dedication (three items), and absorption (three items). Based on CFA, we removed one item due to its low loading (α = 0.89).

Controls

Prior research has identified followers’ gender and tenure as potentially important variables that can influence employees’ attitudes and leader effectiveness (e.g., Riordan, Griffith, & Weatherly, Reference Riordan, Griffith and Weatherly2003; Walumbwa, Wang, Lawler, & Shi, Reference Walumbwa, Wang, Lawler and Shi2004). Moreover, a follower's work engagement can depend on his/her hierarchical position (i.e., whether an employee is in a supervisory position or not). Gender was coded as ‘1’ for female, ‘0’ for male. Tenure was measured as the number of years working in the current position with the same supervisor, and hierarchical position was coded as a dummy variable standing for ‘1’ when ‘supervisor’ and ‘0’ otherwise.

Reliability and Validity

After examining our measurements individually, we conducted a CFA to confirm the properties of our measures in the Russian sample and to establish convergent and discriminant validity. Results showed that the seven-factor model (transformational leadership, paternalistic leadership, authoritarian leadership, self-esteem, self-efficacy, job control, and work engagement) fits the data well: χ 2 = 1443.35 (df = 718), p < 0.01; χ2/df = 2.01, RMSEA = 0.05, GFI = 0.96, AGFI = 0.95 (O'Rourke & Hatcher, Reference O'Rourke, Psych and Hatcher2013). Based on MacCallum, Browne, and Sugawara (Reference MacCallum, Browne and Sugawara1996) power calculation techniques for structural equation models, the statistical power for our RMSEA was within the recommended range, standing at 0.99 (Preacher & Coffman, Reference Preacher and Coffman2006).

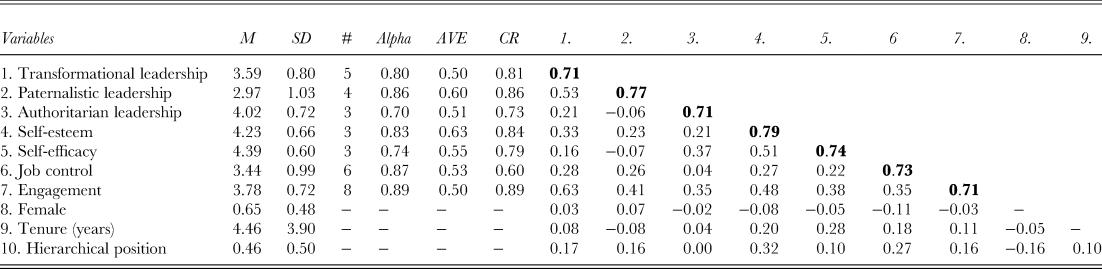

All final standardized loadings were significant and superior to 0.60 (Anderson & Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988). For all the constructs, the average variances extracted (AVE) were larger than 0.50, and the construct reliabilities were larger than 0.70, altogether providing support for convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). In addition, the correlations with other latent constructs were smaller than the square root of each construct's AVE, providing support for discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). In sum, the analyses showed that our final measures were reliable and valid. Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables. We note that transformational and paternalistic leadership are highly correlated (r = 0.53). Nonetheless, the multicollinearity diagnostics showed that all variance inflation factors (VIF) were between 1.00 and 1.43, well below the threshold value of 3, indicating no multicollinearity issues.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Notes: N = 403. #: Number of items. Alpha: Cronbach's alphas. AVE: Average Variance Extracted. CR: Construct Reliability. Values in bold on the diagonal are the square roots of the AVEs for each construct. The off-diagonal elements are correlations between constructs.

All correlations above 0.08 were significant at the 5% level.

The CFAs showed that not only the seven-factor model was appropriate but also better than a single factor model (χ 2 = 2025.72; df = 782; p < 0.01; χ2/df = 2.59; RMSEA = 0.06; GFI = 0.82; AGFI = 0.80). Additionally, all item loadings were still significant after the inclusion of a common latent factor (Williams, Hartman, & Cavazotte, Reference Williams, Hartman and Cavazotte2010). These results suggest that potential common method bias was unlikely to bias the interpretations of our analyses (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003).

RESULTS

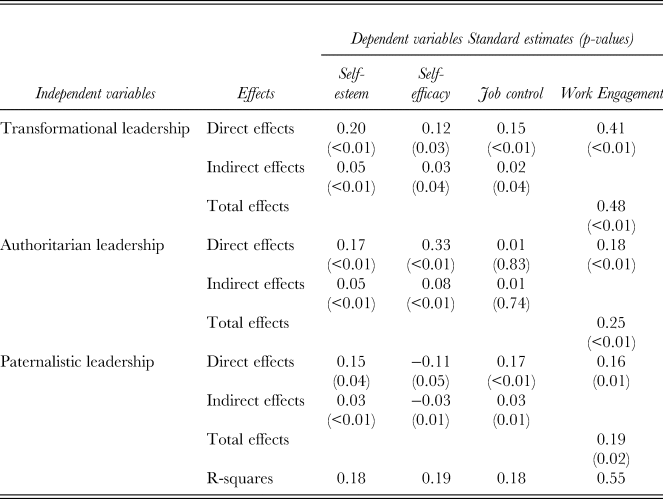

To test our hypotheses, we estimated the hypothesized structural model (see Table 2). The fit indices were: χ 2 = 1523.24; df = 725; p < 0.01; χ2/df = 2.10; RMSEA = 0.05; GFI = 0.98; AGFI = 0.98. The standardized estimate of the path from transformational leadership to work engagement was positive and significant (direct effect: b = 0.41, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 1a. The relationships between transformational leadership and self-esteem, self-efficacy, and role job control were significant and positive (respectively, b = 0.20, p < 0.01; b = 0.12, p = 0.03; b = 0.15, p < 0.01). Additionally, positive and significant indirect effects have been found for the three mediators (self-esteem: b = 0.05, p < 0.01; self-efficacy: b = 0.03, p = 0.04; job control: b = 0.02, p = 0.04) demonstrating complementary mediations. It means that both mediated effects and direct effect exist and point in the same direction (Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, Reference Zhao, Lynch and Chen2010). The triple mediation increased the total effect of transformational leadership on work engagement to 0.48 (p < 0.01), supporting Hypotheses 1b, 1c and 1d.

Table 2. Results of structural equation modeling estimations

Notes: N = 403. Standardized estimates, controlled for gender (b = −0.03, p = 0.46), tenure (b = −0.00, p = 0.95), and hierarchical position (b = −0.05, p = 0.21) – coefficient from Work Engagement model.

The relationship between authoritarian leadership and work engagement was positive and significant (direct effect: b = 0.18, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 2a. Authoritarian leadership was also significantly and positively associated with self-esteem (b = 0.17, p < 0.01) and self-efficacy (b = 0.33, p < 0.01). No significant effect was found for job control (b = 0.01, p = 0.83). In terms of mediation, significant and positive relationships were found between authoritarian leadership and work engagement through self-efficacy (b = 0.08, p < 0.01) and self-esteem (b = 0.05, p < 0.01), thus confirming Hypotheses 2b and 2c. These complementary mediations increased the total effect of authoritarian leadership on work engagement to 0.25 (p < 0.01).

Finally, paternalistic leadership was positively and significantly associated with work engagement (direct effect: b = 0.16, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 3a is confirmed. The direct effects of paternalistic leadership on self-esteem (b = 0.15, p < 0.01) and job control (b = 0.17, p < 0.01) were positive and significant while negative and significant on self-efficacy (b = −0.11, p = 0.05). A competitive mediation (both mediated effect and direct effect exist but point in opposite directions (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lynch and Chen2010)) was found in the case of self-efficacy in the relationship between paternalistic leadership and work engagement, with a negative and significant effect of -0.03 (p = 0.03). Additional complementary mediations effects were found for self-esteem (b = 0.03, p = 0.01) and job control (b = 0.03, p < 0.01) so that the total effect of paternalistic leadership on work engagement was 0.19 (p < 0.01). These results provide support for Hypotheses 3b and 3c.

DISCUSSION

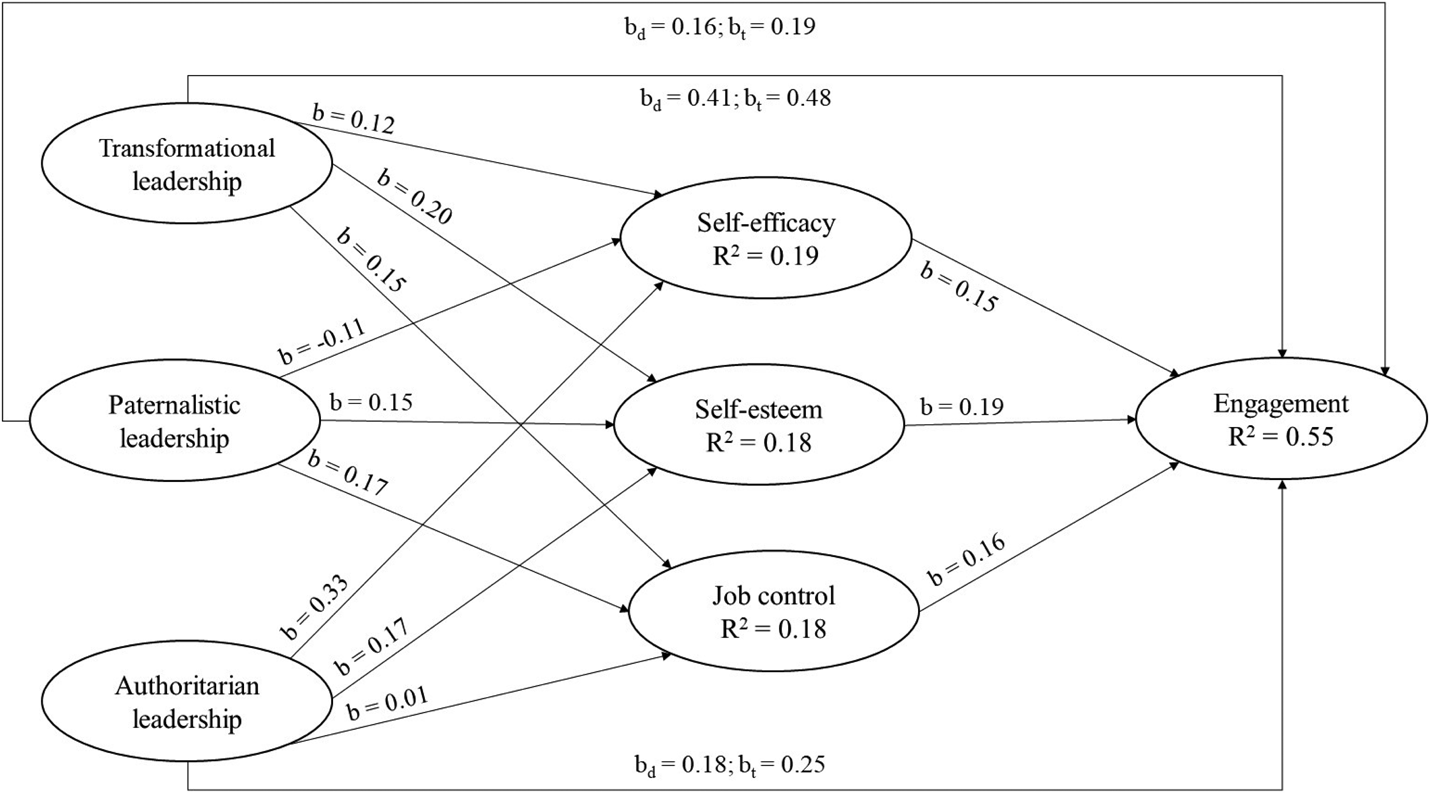

The study has addressed two important but currently under-researched questions in contemporary leadership research. The first deals with the relative importance and complementarity of different leadership behaviors and the second concerns the unique mediating mechanisms through which different leadership behaviors exert their influences on followers (see Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; Piccolo & Colquitt, Reference Piccolo and Colquitt2006; Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017; van Knippenberg & Sitkin, Reference van Knippenberg and Sitkin2013; Walumbwa et al., Reference Walumbwa, Avolio and Zhu2008). Figure 1 depicts the results of our analyses.

Figure 1. Structural model testing

In relation to the first question, our analysis shows that the three leadership styles, which we examined in this study, i.e. transformational, paternalistic, and authoritarian, although overlapping to some extent, are in fact largely complementary to each other. Whereas transformational leadership explains a relatively large share of the variance in followers’ work engagement (effect size: Cohen's f2 = 0.30; medium size effect, see Cohen, Reference Cohen1988), nonetheless both authoritarian and paternalistic leadership also contribute to followers’ work engagement via their unique - although weaker - influences (effect sizes: Cohen's f2 = 0.07 and 0.04 respectively; both small size effects). We found all three styles relate to followers’ work engagement positively. These findings contradict several previous studies that found the effects of authoritarian and paternalistic leadership on follower outcomes to be largely negative (see Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Li & Sun, Reference Li and Sun2015; Zhang & Xie, Reference Zhang and Xie2017).

The fact that we conducted our study in Russia, a cultural context that scores high in power distance and uncertainty avoidance (Naumov & Puffer, Reference Naumov and Puffer2000), can partially explain our different results. Yet, given that other studies have also found positive effects in the case of both styles (see Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018; Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2006, 2008; Wang & Guan, Reference Wang and Guan2018; Wasti et al., Reference Wasti, Tan and Erdil2011; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang, Li and Liu2012), to fully understand the extant mixed evidence, we need to consider the focal relationships more closely and in more detail. One way to do it is via the prism of psychological mechanisms through which these leadership behaviors influence followers. This leads us to what our results tell us concerning our second research question.

Our findings indicate that the three styles influence followers via different psychological mechanisms. As we expected, the most encompassing style that relates to followers via all three mediating mechanisms is transformational. It provides followers with all three psychological resources, as per the JDR theory, tested in our study. Transformational leadership motivates followers to become more engaged in their work by boosting their self-esteem and self-efficacy as well as by increasing their perceived job control. In this sense, our findings support Shamir's theory of self-concept (Shamir et al., Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993, 1998, 2000), which postulates that transformational leaders influence positively the self-perceptions of followers and make them feel better about themselves. They also increase followers’ perceived control over job-related tasks through support and feedback.

Moreover, our findings provide support for the generalizability of transformational leadership in the Russian context. Up to now, the evidence of positive effects of this type of leadership in Russia has been rare, despite the calls for Russian managers to adopt more participative and delegating leadership styles, e.g. authoritative style (e.g., Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries2000; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer and Darda2010). Moreover, recent research shows that this style is relatively rare among top managers in private business organizations in Russia (see Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018). Against this background, our results add to the growing evidence of the positive effects of transformational leadership also in Russia (see Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018; Elenkov, Reference Elenkov2002; Koveshnikov & Ehrnrooth, Reference Koveshnikov and Ehrnrooth2018).

One possible reason why transformational leadership is the most influential for followers’ work engagement in contemporary Russia, despite its strong historical legacy of more control-oriented leadership styles (e.g., Fey et al., Reference Fey, Adaeva and Vitkovskaia2001; Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries2001), is the presumably changing nature of Russian followers, whose leader expectations tilt toward higher levels of involvement, delegation, and participation. Recently, Koveshnikov and Ehrnrooth (Reference Koveshnikov and Ehrnrooth2018) speculated that Russian employees might be not as receptive as their Western counterparts to transformational leadership behaviors, which employ various symbolic elements (e.g., visions, mottos, values) to inspire followers, due to the enduring legacy of the Soviet period whereby various symbols and slogans were the main propaganda vehicles. Yet, given the relatively young average age of our respondents, many of them do not have these experiences and memories. Therefore, our study echoes earlier conceptual studies (e.g., Astakhova et al., Reference Astakhova, DuBois and Hogue2010) and suggests that the new generation of Russian employees is gradually moving toward developing more Western-like expectations of their leaders thus potentially increasing the relevance and effectiveness of transformational leadership in contemporary Russia (cf. Koveshnikov & Ehrnrooth, Reference Koveshnikov and Ehrnrooth2018; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008).

Complementing the effects of transformational leadership, paternalistic appears to contribute to followers’ work engagement, as we expected, by increasing followers’ perceived job control. It seems that feeling protected and cared for by a leader provides a follower with a sense of security and control in terms of how (s)he goes about doing his/her job. We also find that paternalistic leaders increase followers’ self-esteem but decrease self-efficacy. These competing mediation effects indicate a complex relationship between paternalistic leadership and intrinsic psychological resources for followers’ work engagement. On the one hand, as we expected, paternalistic leaders make followers feel better about themselves as a result of being associated with and supported by a leader who cares about every aspect of the followers’ lives as well as both their work-related and personal welfare (Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2006; Pellegrini et al., Reference Pellegrini, Scandura and Jayaraman2010). On the other hand, it appears to trigger a feeling of helplessness and dependency on one's leader (Kets de Vries, Reference Kets de Vries2000; Pellegrini et al., Reference Pellegrini, Scandura and Jayaraman2010).

Thus, our results add to the evidence of the complex nature of paternalistic leadership and its influences on followers and provide a possible explanation for the mixed results that research on this type of leadership and its influences found in the past (e.g., Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Pellegrini et al., Reference Pellegrini, Scandura and Jayaraman2010). Paternalistic leadership does not seem to make followers more self-efficacious, in fact, we found that it decreases their self-efficacy, yet it offers them the extrinsic comfort of ‘fatherly’ care and support from a proximal leader when dealing with their job-related tasks, making them feel both better about themselves and more valued. This type of leadership provides a mixed blessing and future research needs to identify possible boundary conditions determining the direction of the leadership's effects on followers.

Finally, in similarity with transformational leadership, authoritarian leadership appears to prime followers’ self-concept in terms of both self-esteem and self-efficacy. Interestingly, in comparative terms, it turns out to be the most influential leadership style for followers’ self-efficacy through which it then relates to followers’ work engagement. In addition, as we expected, authoritarian leaders also seem to be effective in facilitating followers’ work engagement through followers’ self-esteem. While these findings can be attributed to the specifics of the Russian context where authoritarian leadership has been shown to influence employees’ attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018; Fey et al., Reference Fey, Adaeva and Vitkovskaia2001; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008), a more general explanation, which we provided above in the theory section, is also plausible.

It seems that the attention and guidance from a powerful and hierarchically more senior leader infuses followers with a sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem. It provides them with intrinsic psychological resources to perform their work tasks. It may have to do with the mood contagion mechanism, mentioned above, or the fact that under authoritarian leadership employees in a sense trade their loyalty for freedom from accountability. In this way, feeling, on the one hand, ‘contaminated’ by the powerful leader and his/her attitudes and, on the other hand, non-accountable for decisions and final results, makes employees more self-efficacious and self-confident (see Rast et al., 2013; Tian & Sanchez, Reference Tian and Sanchez2017; Wang & Guan, Reference Wang and Guan2018). At the same time, on the downside, the need to strictly follow and obey orders from a leader does not really contribute to followers’ perceived job control and instead makes them dependent on the leader's detailed guidance concerning their job-related tasks. Nonetheless, taken together these results are interesting and clearly need to be examined in more depth in future research. They point toward intriguing positive consequences of authoritarian leadership behaviors (see also Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018) that need to be investigated further to identify these behaviors’ implications and boundary conditions (cf. Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018).

Lastly, we note that our analyses found the role of control variables such as gender, age and hierarchical position to be insignificant in predicting how the three leadership styles influence employee work engagement. Our study indicates that although these variables might affect what leadership orientations Russian employees have, as previous research has suggested (Astakhova et al., Reference Astakhova, DuBois and Hogue2010; Balabanova et al., Reference Balabanova, Efendiev, Ehrnrooth and Koveshnikov2015), they do not influence how Russian employees react to different leadership styles with work engagement behaviors. It suggests the predominant role of employees’ implicit leadership theories in determining their reactions to different leadership behaviors over employees’ gender, age and hierarchical position.

Theoretical Advances

To sum up, the article makes three contributions to leadership literature. First, it is one of the first studies to theorize and provide evidence for the relative importance and complementarity of three different types of leadership behaviors in facilitating positive follower outcomes. More concretely, we show that transformational, paternalistic and authoritarian leadership behaviors jointly explain a significant share of followers’ work engagement. Importantly, all three explain a unique share of the explained variance thus indicating that the three styles are complementary in their influences. In this way, our study responds to the calls for integrative examinations of different leadership styles (Casimir, Reference Casimir2001; De Cremer, Reference De Cremer2006; Hoch et al., Reference Hoch, Bommer, Dulebohn and Wu2018; Schuh et al., Reference Schuh, Zhang and Tian2013).

In addition, we address the question of how these complementary effects are achieved by theorizing based on JDR theory and examining empirically the effects of three mediating mechanisms, namely self-efficacy, self-esteem, and perceived job control. Thus, we increase our understanding of different mechanisms through which the focal leadership styles operate on followers (DeRue et al., Reference Derue, Nahrgang, Wellman and Humphrey2011; Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; Hoch et al., Reference Hoch, Bommer, Dulebohn and Wu2018; Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017; van Knippenberg & Sitkin, Reference van Knippenberg and Sitkin2013; Walumbwa et al., Reference Walumbwa, Avolio and Zhu2008). We show that to some extent the three mediating mechanisms overlap, although with some notable differences. For instance, our findings illuminate the multifaceted influence of transformational leadership, which provides followers with both intrinsic, i.e. self-esteem and self-efficacy, and extrinsic, i.e., job control, psychological resources for work engagement. In contrast, the effects of the remaining two styles are narrower. Whereas authoritarian leadership is associated positively with followers’ self-concept, the nature of the positive association of paternalistic leadership is largely extrinsic. Hence, our study sheds light on the comparative nature of different leadership styles’ influences on followers.

Second, our study focuses on two leadership styles, namely paternalistic and authoritarian, which are perceived largely negatively in the West and remain little understood in the leadership literature. We provide a still rare theoretical explanation and empirical evidence for the positive influences of these styles by adding to literature that tries to untangle how the two operate on followers (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Wang2014; Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000; Farh et al., Reference Farh, Cheng, Chou, Chu, Tsui, Bian and Cheng2006; Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018; Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2008; Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang, Li and Liu2012; Zhang & Xie, Reference Zhang and Xie2017). Our study provides a possible explanation for the hitherto inconclusive and mixed results that previous research on these two styles has obtained. We uncover that the effects of authoritarian leadership tend to be rather narrowly focused, facilitating followers’ self-concept but being ineffective for more extrinsic aspects of followers’ jobs. Thus, depending on examined outcomes, research might find the effects of authoritarian leadership to be different. Moreover, the intrinsic nature of the leadership's influence points toward a possible boundary condition for authoritarian leadership's effectiveness. Whereas previous research found the influence of authoritarian leadership to be enhanced in high power distance cultural contexts (e.g., De Hoog et al., Reference De Hoogh, Greer and Den Hartog2015; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Xu, Chiu, Lam and Farh2015), we highlight the psychological nature of followers as a possible determinant of such leaders’ effectiveness. Based on our study, we can speculate that individuals who are more receptive to mood contagion as well as those with an elevated need to belong to a high status group or be associated with a powerful person might be more prone to the positive influences of authoritarian leadership.