INTRODUCTION

Perhaps nowhere has the need for organizational change been more pressing than in the transition from a state-controlled to market-oriented system in the areas of the former Soviet Union (FSU), where firms have had to cope with fundamentally altered formal institutional environments. This institutional disruption requires punctuated, systemic organizational change and ongoing adjustments as the transition evolves, emphasizing the capacity for change as a determinant of firm performance in these contexts (Judge, Naoumova, & Douglas, Reference Judge, Naoumova and Douglas2009). Such multi-level, transformative change is ultimately the responsibility of individual actors (St. John, Reference St. John, Ketchen and Bergh2005), and researchers have recognized the importance of micro, person-oriented considerations in organization change (Battilana & Casciaro, Reference Battilana and Casciaro2013; Judge, Thorensen, Pucik, & Welbourne, Reference Judge, Thorensen, Pucik and Welbourne1999; Kleinbaum & Stuart, Reference Kleinbaum and Stuart2014). Here, our focus is on employees, as their resistance to change is widely cited as a principal inhibitor of organizational change, particularly in the FSU (cf. May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy, & Ledgerwood, Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011).

Nearly 300 years ago, Peter the Great observed that ‘anything that is new, even if it is good and necessary, our people will not do without being compelled’ (Massie, Reference Massie1981: 773). Recently, evidence of pervasive employee resistance to change in the post-Soviet region, including Belarus, Bulgaria, Estonia, Russia, and Ukraine, suggests formidable impediments to forging more competitive firms (cf. May et al., Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011), attributable largely to an ‘indestructible Soviet mentality’ (Garin, Reference Garin2017) that pervades the region, especially in Ukraine and Russia (Sohryu, Reference Sohryu2015), which together formed the epicenter of the Soviet Union. This mindset, termed ‘Homo-Sovieticus’, constrains the development of Ukraine (Bilan, Reference Bilan2016), particularly in the eastern half of the country, which is more closely aligned with Russia, ethnically and ideologically (Björkman & Lervik, Reference Björkman and Lervik2007), as well as politically and economically (Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015).

A key issue in the behavioral literature is how change endeavors influence the employee-organization relationship, specifically as indicated by organizational commitment (Armenakis & Bedeian, Reference Armenakis and Bedeian1999), a psychological state pertaining to the level of attachment the employee has to the organization (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991). Organizational commitment (OC) influences job attendance, performance, turnover, and organizational citizenship, and correlates positively with job involvement, job satisfaction, and occupational commitment (Fedor, Caldwell, & Herold, Reference Fedor, Caldwell and Herold2006; Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002). Moreover, OC, along with commitment to change, predicts behavioral support for a change (Herscovitch & Meyer, Reference Herscovitch and Meyer2002). Consequently, the level of employee OC is associated with an array of job-related behaviors important for firm change and subsequent organizational performance.

OC is particularly relevant during disruptive institutional transitions as organizational change influences the level of person-organization fit or the degree to which employees believe that their values match those of the organization (Caldwell, Herold, & Fedor, Reference Caldwell, Herold and Fedor2004). This raises concerns both for the impact on individuals’ responses to the change and for their relationship with the organization (Fedor et al., Reference Fedor, Caldwell and Herold2006), including the potential to reduce OC (Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Herold and Fedor2004). Consequently, we focus on dispositional resistance to change (RTC) and OC, which address these two considerations. In doing so, we draw on trait activation theory (Tett & Guterman, Reference Tett and Guterman2000), which suggests that a trait alone is insufficient to predict outcomes; instead, the subject's trait will interact with the situation in determining behaviors. Here, we argue that organizational change is a key element of the situation that will ‘activate’ employees’ dispositional RTC, such that those who are predisposed to resist change will be less committed to their organizations. That is, in the absence of organizational change, a person's RTC may remain dormant and be unrelated to his or her OC.

We also draw on trait activation to predict how employees with varying levels of RTC will respond to change based on their perceptions of two potentially important situational factors that are likely to affect the way that employees experience change: trust in management and procedural justice. Both of these constructs reflect important employee perceptions of the work environment during change (Van den Bos, Wilke, & Lind, Reference Van den Bos, Wilke and Lind1998), and are key determinants of employee commitment (Mathieu & Zajac, Reference Mathieu and Zajac1990; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002). Moreover, these situational factors are particularly important in the post-Soviet context, where distrust in organizational climates and favoritism as a basis of managerial decision-making have been pervasive (May & Stewart, Reference May and Stewart2013; Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015). Consequently, we expect that the relationship between RTC and OC will be influenced by these two organizational factors.

We specify, to our knowledge, a heretofore unexamined model of the relationship between RTC and OC, specifically, affective OC, moderated by the work experience factors of perceptions of trust in top management and procedural justice. We expect that trust in top management will mitigate the negative relationship between RTC and OC, whereas procedural justice will exacerbate this relationship because of contextual characteristics, namely, the uncertainties surrounding the novelty of standardized work policies and procedures grounded in a universalist approach when applied to a particularist setting like Ukraine. This analytical approach simultaneously considers both personality and work experience, which is rare in the extant change literature (Oreg, Reference Oreg2006), but holds promise to better explain outcomes (Judge & Zapata, Reference Judge and Zapata2015), including understanding OC (Mathieu & Zajac, Reference Mathieu and Zajac1990). We test this model with a sample of employees from four firms in Ukraine, all of which were undergoing similar fundamental changes at the time of data collection, including in the performance evaluation and compensation systems of their human resource management function.

Institutional reform in Ukraine has been particularly fraught due to fragile property rights and self-serving oligarchs exerting considerable economic influence (Kononovo, Reference Kononov2010), as well as rampant bureaucracy, perceptions of ineffectiveness, and even corruption, in regulatory bodies and the legal system (May et al., Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011). These formal institutional conditions, combined with the informal institutional environment, pose a starkly different institutional setting to the West, where the theory we draw on was developed. Hence, Ukraine constitutes the ideal unconventional setting that Bamberger and Pratt (Reference Bamberger and Pratt2010) identified as useful for theory development. The indigenous considerations in Ukraine not only inform the development of local management theory (Van de Ven, Meyer, & Jing, Reference Van de Ven, Meyer and Jing2018) but also represent potential contingency effects that can enrich extant theory (May & Stewart, Reference May and Stewart2013) by extending Western theories to make them more internationally applicable (cf. Tsui, Reference Tsui2007) in a manner described by May and Stewart (Reference May and Stewart2013) as ‘double-loop theorizing’ across contexts to forge theory more comprehensive in its explanatory reach. The results also have practical implications in potentially informing managerial intervention by predicting the potential for resistance and by addressing workplace climate and practices to improve commitment to the firm.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

In addition to the aforementioned features of formal institutions, the informal institutional aspects of Ukraine inform this study. The culture of Ukraine is characterized by relatively high levels of power distance (an individual's acceptance of power differentials at different levels of hierarchy in society, such as between authorities and subordinates), uncertainty avoidance (an individual's attitude toward uncertainty and risk, and the need for structure), and collectivism (a focus on others such that relationships are particularly important and necessitate loyalty) (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2004; Naumov, Reference Naumov1996; Prykarpatska, Reference Prykarpatska2008). These societal, cultural values, along with the historical legacy of communism, are in stark contrast to the West, where most of the theory concerning change and organizational commitment has focused. Moreover, these values influence workplace norms, and Ukraine firms are typically characterized by patriarchal organizational cultures, high managerial control, separation of workers from managers, low employer commitment to employees, and lack of job-based evaluations of performance and rewards (Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015). Overall, we would expect that individuals’ assumptions concerning high power distance, and their anxieties stemming from high uncertainty avoidance, in particular, complicate change processes, which are inherently uncertain, particularly when they entail change that disrupts historical workplace norms and relationships (Kleinbaum & Stuart, Reference Kleinbaum and Stuart2014).

Cultural-cognitive institutional frameworks provide the foundations of institutional logics (Scott, Reference Scott2008), entailing ‘beliefs, practices, values, assumptions, and rules that shape cognition and guide decision-making in a given social context’ (Thornton & Ocasio, Reference Thornton and Ocasio1999: 801). Institutions are a primary source of identity creation and imprinting (Puffer, McCarthy, & Satinsky, Reference Puffer, McCarthy and Satinsky2018) whereby individuals develop characteristic traits that reflect the nuances of their environment, here from communist imprinting, during their formative years (Banalieva, Puffer, McCarthy, & Vaiman, Reference Banalieva, Puffer, McCarthy and Vaiman2018; Grigore & Tucker, Reference Grigore and Tucker2014). Institutions as rules and shared meaning are path dependent (Ardichvili & Zavyarova, Reference Ardichvili and Zavyalova2015) and tend to persist (Kostova & Roth, Reference Kostova and Roth2008), even if they are unproductive (North, Reference North1990) or the environment changes (Marquis & Tilcsik, Reference Marquis and Tilcsik2013). The Soviet experience entailed strong situational constraints (cf. Roth & Kostova, Reference Roth and Kostova2003), as evidenced by indications that, although formal institutions have changed, Ukrainians are still strongly influenced by the Soviet past (Bilan, Reference Bilan2016; Garin, Reference Garin2017; Hyrych, Reference Hyrych2017; May et al., Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011; Sohryu, Reference Sohryu2015). This embeddedness in the past emphasizes the role of informal institutions in compensating for country inefficiencies (Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015), underscoring the importance of norms and patterns of practice in understanding change phenomena, such as the dispositional, cognitive, and attitudinal variables in this study.

Resistance to Change

Piderit (Reference Piderit2000) posited that employees’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors concerning change are all important, but may not be mutually consistent. Therefore, resistance to change is best viewed as a multidimensional position toward change comprising cognitive, affective, and behavioral components. Consistent with this conceptualization, Oreg (Reference Oreg2003: 680) developed a multidimensional (routine seeking, emotional reaction, short-term thinking, and cognitive rigidity) dispositional measure of RTC ‘designed to tap an individual's tendency to resist or avoid making changes, to devalue change generally, and to find change aversive across diverse contexts and types of change’. Treated this way, RTC is an individual's enduring generalized response to change, rather than a response to a specific change situation, and can explain why some employees are more adaptive to change, while others are more recalcitrant.

Ukraine provides an interesting context for studying RTC. In addition to the aforementioned cultural considerations, the communist ‘attitudinal legacy’ (Blanchflower & Freeman, Reference Blanchflower and Freeman1997) persists (Hyrych, Reference Hyrych2017; Sohryu, Reference Sohryu2015) and can influence individuals’ values and behaviors (Wyrwich, Reference Wyrwich2013). A study of Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine found evidence of a shared worldview, comprising: paternalism, conformity, fear of reform, intolerance of unfamiliar others, opposition to individualism, social alienation, and undervaluation of knowledge and talent (Hyrych, Reference Hyrych2017). These contextual considerations have consequences for people's beliefs and attitudes concerning change-related phenomena and are relevant to the dimensions of RTC. For instance, RTC includes the dimension of routine seeking. Routine and conformity, facilitated by rules and regulations, were important in the Soviet period (Michailova, Reference Michailova2000), and remain so (May & Stewart, Reference May and Stewart2013). Similarly, change associated with institutional transition emphasizes the emotional reaction of RTC to imposed change, as evinced by the rise in alcohol abuse (Samokhvalov et al., Reference Samokhvalov, Pidkorytov, Linskiy, Minko, Minko, Rehm and Popova2009), suicides (Maksymenko, Reference Maksymenko2018), low birth rate, and decreased life expectancy (Garin, Reference Garin2017; World Life Expectancy, 2016) in the region since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Also, short-term planning and tasks are still emphasized over longer-term considerations (May, Puffer, & McCarthy, Reference May, Puffer and McCarthy2005; McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood, & Stewart, Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008; Michailova, Reference Michailova2000). Moreover, unquestioning compliance was expected during the Soviet period, while independent, critical thinking (cognitive flexibility) was often punished (Michailova & Husted, Reference Michailova and Husted2003). Even still, those higher in RTC are less likely to seek new knowledge for their firms in Ukraine (May et al., Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011), signaling their preference for the status quo. Overall, given the relevance of the dimensions of RTC in this institutional context, and its imprinting effects on people, we believe that RTC holds particular value for better understanding OC in the region.

Organizational Commitment

In an attempt to help clarify the state of a burgeoning field complicated by multiple conceptualizations and measures, Meyer and Allen (Reference Meyer and Allen1991) described OC as a psychological state that includes three distinguishable components: affective (an attitude or desire), continuance (a need), and normative (a perceived obligation). Meyer and Allen (Reference Meyer and Allen1991: 14) defined affective commitment as an employee's ‘attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organization’. The authors described continuance commitment as more calculative, entailing the perceived costs of continuing with the organization compared to leaving it, and normative commitment as opting to maintain organizational membership out of a sense of obligation. Meyer and Allen (Reference Meyer and Allen1991) suggested that, to varying degrees, an individual can experience all three forms of commitment such that the elements might interact to influence behavior, although they have different antecedents, correlates, and consequences (cf. Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002). For instance, personal dispositions (like RTC, as addressed here), work experiences, and organizational structure (i.e., the degree of decentralization of decision-making and the formalization of policies and procedures) are the most important predictors of affective commitment (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991).

As for correlates and outcomes, there are differences in the magnitude and direction depending upon the type of OC (cf. Mathieu & Zajac, Reference Mathieu and Zajac1990; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002). To our knowledge, there have been only two studies of OC in the FSU. Buchko, Weinzimmer, and Sergeyev (Reference Buchko, Weinzimmer and Sergeyev1998) found job involvement, work satisfaction, promotion satisfaction, and supervisor satisfaction all positively significantly correlated with attitudinal OC in a sample of 180 employees of an electrical components manufacturer in Russia. Turnover intention was negatively correlated with attitudinal commitment, defined as the acceptance of the organization's values, and the willingness to exert effort on the organization's behalf (Mowday, Steers, & Porter, Reference Mowday, Steers and Porter1979). Labatmedienė, Endriulaitienė, and Gustainienė (Reference Labatmedienė, Endriulaitienė and Gustainienė2007) validated the three-component measure of OC by Allen and Meyer (Reference Allen and Meyer1990) using a sample of 105 non-managerial employees across medium-sized enterprises in Lithuania. The researchers also reported a negative relationship between OC and intention to leave the firm but found no significant relationships between affective commitment and age, gender, educational level, organizational tenure, or personality traits.

We focus on affective OC because its generalized psychological orientation makes it more important than other forms of commitment in terms of understanding why an employee will act in the best interests of the organization across situations (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991). Research supports this contention, as affective commitment, with its emphasis on personal fulfillment, strongly and consistently correlates with outcomes relevant for both employees and the organization (Mathieu & Zajac, Reference Mathieu and Zajac1990; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002). The meta-analysis by Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002: 20) indicated that, of the three types of OC, ‘affective commitment had the strongest and most favorable correlations with organization-relevant (attendance, performance and organizational citizenship behavior) and employee-relevant (stress and work-family conflict) outcomes’. Notably, their meta-analytic results indicated similar findings with non-North American samples, suggesting that expected outcomes of affective commitment would be cross-culturally generalizable.

Resistance to Change and Organizational Commitment

Although individual dispositions, once largely neglected in organizational change research (Judge et al., Reference Judge, Thorensen, Pucik and Welbourne1999), are garnering more attention, including some investigation of how dispositional RTC influences change phenomena, these studies are sparse and have not included links between RTC and OC. The work of Oreg (Reference Oreg2003, Reference Oreg2006; and with Sverdlik, Reference Oreg and Sverdlik2011) and Elias (Reference Elias2009), considered in conjunction with trait activation theory, provides a basis for understanding the connection between RTC and OC. Oreg (Reference Oreg2006) found that individuals high in dispositional RTC were less likely to initiate change and were more likely to hold negative attitudes toward change initiatives. These negative attitudes about change, we reason, would have implications for OC, given its focus on an individual's psychological affiliation with the firm. Additionally, Naus, van Iterson, and Roe (Reference Naus, van Iterson and Roe2007) discovered that the interaction of rigidity, measured with two of Oreg's (Reference Oreg2003) RTC items, and role conflict, significantly predicted employees’ inclination to leave the organization, an indirect indicator of OC because OC influences turnover (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002). Moreover, Oreg and Sverdlik (Reference Oreg and Sverdlik2011), drawing on the results of three studies, concluded that the correlation between individuals higher in dispositional RTC and ambivalence about change was moderated by their orientation toward the change agent, defined as both trust in management and identification with the organization, a construct with similarity to OC.

Elias (Reference Elias2009) found that change attitudes, defined as an individual's evaluative judgment of a change initiative, fully mediated the relationship between growth need strength and affective OC. Additionally, change attitudes partially mediated the relationships between both locus of control and internal work motivation with OC. Notably, although Elias characterized the mediator as an attitude toward change, it was a general approach to change, not to the specific change situation. Thus, the results produced with this measure may have implications for the relationship between RTC and OC.

To conceptualize the connection between RTC and OC, we draw on trait activation theory, which argues that the extent to which a particular trait is likely to affect an employee's attitudes or behaviors is dependent on the degree to which the situation provides an opportunity for, or necessitates, the activation of the trait (Tett & Guterman, Reference Tett and Guterman2000). Trait activation theory is rooted in Hattrup and Jackson's (Reference Hattrup, Jackson and Murphy1996) contention that it is essential to understand workplace situations if we want to develop any comprehension of how dispositions are related to workplace outcomes. Research provides consistent support for the core ideas of trait activation in the workplace (e.g., Hochwarter, Witt, Treadway, & Ferris; Reference Hochwarter, Witt, Treadway and Ferris2005; Kamdar & Van Dyne, Reference Kamdar and Van Dyne2007). Here, the implication is that employees’ RTC should not be related to their OC unless the employees recognize that the organization is experiencing substantive change. Without this understanding, the trait will remain dormant. On the other hand, when employees recognize that significant change is occurring, RTC will be activated, and the experience of change should prompt employees high in RTC to feel lower levels of emotional attachment to their organizations.

Ultimately, successful organizational change requires that employees accept and facilitate the change. Yet change can have a range of implications for employees, such as uncertainty, increased work demands, and the loss of a sense of control (cf. Fedor et al., Reference Fedor, Caldwell and Herold2006), and can disrupt employees’ psychological contracts with their organizations (Ashford, Lee, & Bobko, Reference Ashford, Lee and Bobko1989). Consequently, the change can alter the alignment between the individual and the organization, a consequence for OC (Cable & Judge, Reference Cable and Judge1996) that has ramifications for important workplace behaviors. Those high in dispositional RTC are more likely to respond to imposed change with negative emotional reactions, including anger, anxiety, and fear (Oreg, Reference Oreg2006). As personality is strongly linked with affect (cf. Oreg, Reference Oreg2006), this reaction has implications for employees’ attitudes toward the organization, including OC. Therefore, we posit that:

Hypothesis 1: There will be a negative relationship between RTC and OC during substantive firm change across institutional settings.

Organizational Context

While trait activation provides the basis for the argument that RTC is likely activated by organizational change, it also provides a backdrop for understanding how situations in organizations may influence the magnitude of employees’ reactions to change. That is, the way that employees interpret the organizational context at the time that change is occurring is likely to affect their reactions to the change. Extant research supports the proposition that organizational contexts can influence the degree to which employees’ dispositional characteristics influence their reactions to change (Mathieu & Zajac, Reference Mathieu and Zajac1990; Sackett, Lievens, Van Iddekinge, & Kuncel, Reference Sackett, Lievens, Van Iddekinge and Kuncel2017). Accordingly, we suggest that it is necessary to consider the role that situational factors play in shaping the relationship between RTC and attitudinal OC. We focus on perceptions of trust in top management and procedural justice, both important for the cooperation necessary for effective change (Tyler, Reference Tyler2003), as work experiences are particularly important antecedents of affective OC (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002), and are especially relevant to an employee's organizational experience in Ukraine.

In addition to the aforementioned uncertainty avoidance, power distance, and collectivist elements of the Ukrainian culture, there are other considerations in the informal institutional environment that we believe are of consequence for the relationships of interest in this study, specifically particularism versus universalism (cf. Michailova & Hutchings, Reference Michailova and Hutchings2006; Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, Reference Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner1997). Particularist cultures stress interpersonal reciprocity, favoritism, and in-group/out-group membership considerations in interpersonal networks, which influence processes and outcomes (May & Stewart, Reference May and Stewart2013). Loyalty to the in-group is expected and is rewarded with protection. Conversely, universalist cultures tend to rely on policies and rules to regulate activity at the macro/social and firm levels. Based on data from the European Social Survey, Nawojczyk (Reference Nawojczyk2006) ranked Ukraine as the most particularist country in the FSU. Ukrainian managers use particularist approaches when delegating tasks, giving feedback, and rewarding employees (Malota, Reference Malota2016).

Inequality and injustice in formal institutions were common in the Soviet experience, and often still prevail, suggesting a different experience in Ukraine with issues of organizational justice than in the universalist cultures of the West. Although some firms are changing, the Soviet legacy of institutional arrangements remains resilient in human resource practices in Ukraine (Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015; Selivanovskikh, Reference Selivanovskikh2018; Talajlo, Reference Talajlo2010). Therefore, we propose that this institutional legacy will help explain the relationship between RTC and OC via the intervening effects of the organizational climate in the midst of firm change initiatives in this context.

Trust in Top Management

Trust in management refers to an employee's situational belief that, among other characteristics, managers are reliable, fair, and competent (Butler, Reference Butler1991). Trust correlates favorably with a number of positive organizational outcomes, including OC, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions (for a meta-analysis, see Choi & Resick, Reference Choi and Resick2016). Trust in top management is particularly critical because higher-level managers typically have greater power based on their position in the hierarchy (i.e., power distance). They also have better access to information and can make decisions (including work assignments, performance evaluations, and restructuring, among others) that affect employees. Based on this, Jiang and Probst (Reference Jiang and Probst2016) suggest that trust in management is especially valuable to employees because it makes uncertain situations (such as organizational change) more predictable. In the high power distance context of our study, we suggest that trust in top management is a situational factor that may be especially important in mitigating the negative relationship between RTC and OC. Employees often perceive change negatively because of its inherent uncertainty; trust in management should reduce this uncertainty, as it signals a willingness to be vulnerable (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995), and thus makes employees feel less threatened by change, allaying some of the concerns of those higher in RTC.

Although trust between employees and management is important for organizational change initiatives (Gomez & Rosen, Reference Gomez and Rosen2001), trust has been infrequently explored as a correlate of OC in the context of organizational change. Yet there is some evidence to support the contention that trust in management will buffer the negative effects of RTC and OC. For example, Jiang and Probst (Reference Jiang and Probst2016) drew on Hobfoll's (Reference Hobfoll1989) conservation of resources theory, which concerns motivations to acquire and protect resources, to argue that trust in management should reduce the strength of the negative relationship between job insecurity and outcomes. Jiang and Probst (Reference Jiang and Probst2016) positioned job insecurity as a resource threat, and trust in management as a resource, as employees who trust management believe that managers will look out for the best interests of employees. The results of their study showed that trust in management moderated the relationships between job insecurity and work satisfaction, supervisor satisfaction, affective commitment, psychological distress, and burnout. Employees who had higher levels of trust in management tended to have more positive (or less negative) reactions to job insecurity, whereas employees with lower levels of trust in management had worse reactions to job insecurity. Similarly, Wong, Wong, Ngo, and Liu (Reference Wong, Wong, Ngo and Lui2005) showed that the negative relationship between job insecurity and helping behavior was weaker when employee trust in the organization was higher.

Trust in management is particularly salient in the FSU due to lingering distrust from the Soviet era (Gurkov & Zelenova, Reference Gurkov and Zelenova2011/2012; May & Stewart, Reference May and Stewart2013; Pučėtaitė, Lämsä, & Novelskaitė, Reference Pučėtaitė, Lämsä and Novelskaitė2010; Stewart, May, McCarthy, & Puffer, Reference Stewart, May, McCarthy and Puffer2009a), and employee reports of managerial inconsistency, lack of interest and even corruption in the region (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008; Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015). This distrust is attributable to historical factors, such as authoritarian and patriarchal organizational structures, complicated relationships between managers and employees, and flexible attitudes towards norms and standards (Pučėtaitė et al., Reference Pučėtaitė, Lämsä and Novelskaitė2010). Yet trust is important for the reciprocity expected within the social networks of favor exchange widely practiced in the area (Michailova & Worm, Reference Michailova and Worm2003), which entails both economic and social exchanges. For these reasons, we aver that trust, an important antecedent of OC in the West, is perhaps more important in the context of the former Soviet region, especially trust in top managers, who have the ultimate authority and power concerning change initiatives. Trust in management can help mitigate some of the anxiety associated with altering the expectations and responsibilities of employees amidst organizational change, particularly for those resistant to change in an area noted for high uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2004; Prykarpatska, Reference Prykarpatska2008), to the benefit of OC.

Hypothesis 2: Trust in top management will moderate the relationship between RTC and OC in Ukraine, such that those higher in RTC, but who trust management, will be more committed to the organization than are those who evince lower trust in management.

Procedural Justice

Organizational justice entails perceptions about the accuracy, consistency, fairness, and correctability of organizational decision-making processes (Colquitt & Rodell, Reference Colquitt and Rodell2011), and the means used to achieve stated aims and distribute rewards and sanctions (Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988). Initially, organizational justice research focused on the former of these considerations, specifically, the perceptions of justice in decision outcomes, but subsequently, attention has been devoted to the processes that result in decision outcomes, termed procedural justice (cf. Colquitt, Reference Colquitt2001). We focus on procedural justice because it may subsume the interpersonal considerations of interactional justice associated with interpersonal interactions (Blader & Tyler, Reference Blader and Tyler2003), and is consistently related to organizational outcomes, such as OC (Sweeney & McFarlin, Reference Sweeney and McFarlin1993; Colquitt, Reference Colquitt2001). In fact, procedural justice is more highly correlated with OC than is distributive justice in change situations (van Dierendonck & Jacobs, Reference van Dierendonck and Jacobs2012). Moreover, procedural justice is an important determinant of people's reactions to change (cf. Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Herold and Fedor2004), and thus, may be important in understanding successful organizational change (Bernerth, Armenakis, Feild, & Walker, Reference Bernerth, Armenakis, Feild and Walker2007).

Procedural justice is particularly important to the development of affective OC because it serves as a signal to employees that the organization supports them, or values their contributions and cares about their well-being (Wayne, Shore, Bommer, & Tetrick, Reference Wayne, Shore, Bommer and Tetrick2002). Perceptions of support, in turn, activate the reciprocity norm, which obligates employees to repay the organization for favorable treatment that it has provided, and strengthens the employee-organization relationship (Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkle, Lynch, & Rhoades, Reference Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkle, Lynch and Rhoades2001). Extensive research shows that a key way that employees respond to favorable treatment is through high levels of affective OC (Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017; Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002). Procedural justice connotes respect and signals to individuals that they are valued members of a group, resulting in commitment and identification, providing the basis for the group engagement model (e.g., Blader & Tyler, Reference Blader and Tyler2009).

Research in the West shows clear and consistent relationships between procedural justice and affective OC. In fact, the meta-analysis by Li and Cropanzano (Reference Li and Cropanzano2009) showed that procedural justice had a stronger relationship with work-related outcomes in North America than in East Asia, suggesting contextual differences in justice effects. There is not much knowledge, however, about organizational justice in the post-Soviet region (Gatskova, Reference Gatskova2013), although socio-cultural contexts affect fairness perceptions associated with organizational justice (Lind, Tyler, & Huo, Reference Lind, Tyler and Huo1997; Silva & Caetano, Reference Silva and Caetano2016).

Because of the context, we anticipate a different outcome in Ukraine than in the West. In much of the FSU, there is a long history of favoritism afforded through particularist norms that emphasize in-group relationships, loyalty, and circumstances over universally applied rules (cf. Gatskova, Reference Gatskova2013; Michailova & Hutchings, Reference Michailova and Hutchings2006; Nawojczyk, Reference Nawojczyk2006). In fact, these practices are used as a means to manipulate or exploit formal rules by using informal norms and personal obligations to gain access, patronage, protection, and security (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2008). These exchanges of favors have a transactional instrumentality and have largely guided human resource practices. For example, even though decades have passed since the collapse of the Soviet Union, there remains a lack of formal regulations and norms for performance appraisal and compensation (Dirani et al., Reference Wyrwich2015; Gurkov & Zelenova, Reference Gurkov and Zelenova2011/2012), and laxity in applying norms and standards that do exist (Pučėtaitė et al., Reference Pučėtaitė, Lämsä and Novelskaitė2010). To wit, guaranteed wages have been low, but have been supplemented by large, arbitrarily determined bonuses, resulting in wage differences of more than 500 percent among employees with similar job titles in the same work unit in Russia (Gurkov & Zelenova, Reference Gurkov and Zelenova2011/2012), suggesting that pay is influenced by the relationship between the employees with their supervisors. Similarly, there are very low levels of formalized performance evaluation systems in Ukraine (Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015). Notably, rewards can influence commitment bonds (Klein, Molloy, & Brinsfield, Reference Klein, Molloy and Brinsfield2012), including affective OC (cf. Gao-Urhahn, Biemann, & Jaros, Reference Gao-Urhahn, Biemann and Jaros2016).

Just as the norms of exchange and reciprocity are important in consideration of trust, we expect that the perceived abandonment of these norms in favor of the formalized standardization of work expectations, practices, and routines of procedural justice will be problematic in Ukraine. While the adherence to standardization in procedural justice produces perceptions of fairness across workgroups in the West (Li & Cropanzano, Reference Li and Cropanzano2009), the exchange of favors produces what might be considered ‘situational fairness’ in much of the post-Soviet region. Such is particularly the case in Ukraine, where a deep, shared distrust of the state has prompted people to rely even more on each other amidst broader institutional uncertainty (Hayonz & Lushnycky, Reference Hayonz and Lushnycky2005) and do business in a relationship-oriented way (Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015). The standardization and consistency inherent in procedural justice threaten to disrupt this informal, relational exchange, producing more uncertainty within the ambiguity of organizational change in a high uncertainty avoidance context like Ukraine. High uncertainty avoidance influences employees’ concerns about justice and attitudes toward the organization that are similar to OC (see the meta-analysis by Shao, Rupp, Skarlicki, & Jones, Reference Shao, Rupp, Skarlicki and Jones2013).

Evidence from Russia supporting this expectation indicates that job security, not higher pay, is the only predictor of positive HR outcomes for non-managerial employees (Fey, Björkman, & Pavlovskaya, Reference Fey, Björkman and Pavlovskaya2000) and that Russian employees will actually leave their jobs for lower-paying positions to avoid the uncertainty of being evaluated on higher performance standards (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008). In Kyrgyzstan, another country once part of the Soviet Union, although one with dissimilarities to Ukraine, procedural justice is related to obedience, but not to organizational participation and loyalty (Özbek, Yoldash, & Tang, Reference Özbek, Yoldash and Tang2016), both correlates of OC. In Ukraine, the implementation of procedural justice motivated the seeking of knowledge (May et al., Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011), perhaps as a means of coping with the uncertainty of new job-related expectations. Given the foregoing, we propose that a change to universal procedural justice considerations from particularist, relationship-based work practices will likely produce additional uncertainty that is particularly threatening to those who are dispositionally resistant to such change and will have negative consequences for their attitudes toward the firm.

Hypothesis 3: Procedural justice will moderate the relationship between RTC and OC in Ukraine, such that those higher in RTC, and who have higher perceptions of procedural justice, will be less committed to the organization than those who evince lower perceptions of procedural justice.

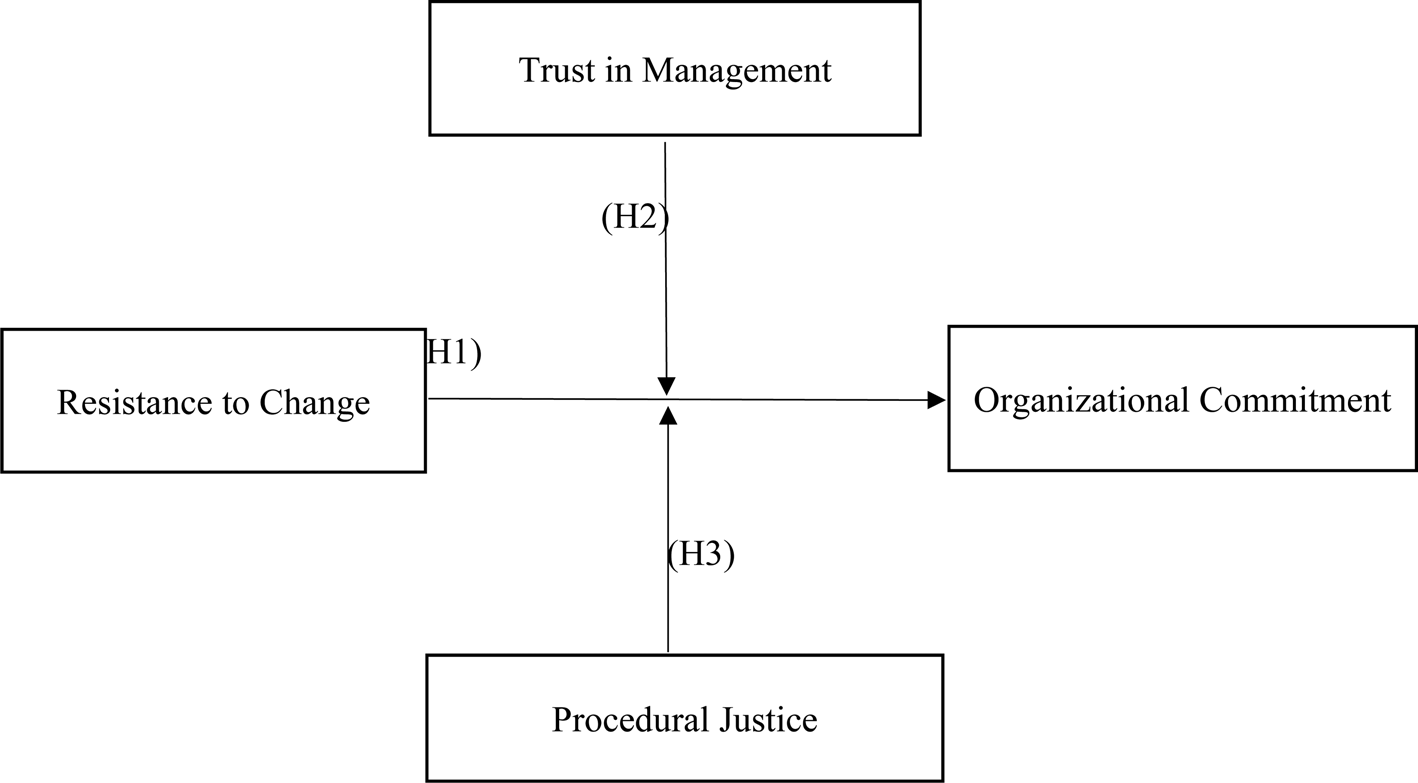

Figure 1 displays the research model.

Figure 1. Research model

METHODS

Sample and Procedures

Access to sites and participants poses considerable obstacles to research in the post-Soviet states due to a lingering legacy of secrecy (Fey et al., Reference Fey, Björkman and Pavlovskaya2000), fear of giving feedback (Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015), and suspicion of outsiders, particularly Westerners (cf. Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, May, McCarthy and Puffer2009a). To overcome these obstacles, we drew on a network of Russian and US academicians, practitioners, and consultants that we have forged over the years to seek participation in the study. One of these people, a widely trusted insider in the region, gained agreement from the CEOs (Directors General) of four privately held companies in Ukraine for their employees to participate in the study. Their agreement, however, was predicated on anonymity, including the collection of minimal demographic data from participants, which is typical in conducting research in emerging economies (cf. May et al., Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011) in order to protect identities to secure participation.

We focused exclusively on non-supervisory employees for inclusion in the study. In all of the firms, each Human Resource (HR) Director presented their employees with a hard copy of the survey, accompanied by a letter from the Director General requesting participation. The employees anonymously submitted their completed surveys in centrally located collection boxes, and the HR staff then collected the completed surveys and forwarded them to us. This similarity in the data collection procedure across firms enhances the comparability of samples (Schaffer & Riordan, Reference Schaffer and Riordan2003). Notably, at the time of data collection, 2009, all of the firms were undergoing large-scale organizational change that would directly influence employees. These reforms included the first-time introduction of job design and descriptions, performance appraisals, and compensation systems linked to performance. Although private, the firms had inchoate HRM departments, which is common in the region, where the embedded institutional legacy from centralized planning typically results in HR practices that are not consistent with those of the West (May & Ledgerwood, Reference May, Ledgerwood, Domsch and Lidokhover2007; Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015; Selivanovskikh, Reference Selivanovskikh2018; Talajlo, Reference Talajlo2010), including not linking the HR function to the goals and strategies of the firm (Gurkov & Zelenova, Reference Gurkov and Zelenova2011/2012).

The sample comprises firms in a range of sectors: a cosmetics retailer, headquartered in Kiev, with retail stores in central and eastern Ukraine; a supermarket chain with 27 stores in the Dnepropetrovsk area; a warehousing and distribution services provider in Donetsk that caters to retail food outlets across Ukraine; and a holding company, based in Dnepro, that oversees retail, transportation and commercial real estate in Ukraine and Russia. In conjunction with management, we targeted 2,300, 1,180, 167, and 305 employees, respectively, from these firms to participate in the study. After eliminating cases with missing data, the final, usable sample totaled 1,607 non-managerial employees, an effective overall response rate of approximately 41%, which we attribute to the support from management and the provided anonymity. Eighty-five percent of the respondents were female, and the sample was relatively young: 65% were age 30 or younger, 22% were 31 to 40 years of age, and 13% were 41 years of age or older.

Measures

Reward expectancy

Using the anticipatory element of Vroom's (Reference Vroom1964) expectancy theory, and drawing on the expertise of the aforementioned network of professionals that we elaborate on later, we developed a five-item Likert-type scale to measure the degree to which employees actually believed that their organization was undergoing change, as evidenced by changes in human resource practices, including the fact that their compensation was about to be linked to their individual job performance for the very first time. An example item is ‘My salary depends on my performance on my job’ (see Appendix I for these and all other measurement items). The Cronbach alpha reliability of the scale was 0.79.

Here, we use the reward expectancy measure as an empirical check to ensure that the subjects in the analysis are only those who believed that change was actually occurring in the HR practices of their firms, a condition prerequisite for activization of RTC. Of all of the changes underway in the firms, we focus on the linking of individual performance and pay because of its immediate relevance to employees’ welfare. This type of check is necessary, we argue, because managers of firms in this region often abandon organizational reforms or capriciously switch among new consultants and techniques before new approaches take hold (May et al., Reference May, Rayter and Ledgerwood2016). It's no wonder then that employees have little confidence in announced change initiatives (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, May, Ledgerwood and Stewart2008), a skepticism also grounded in the experience of frequent change of state directives during the Soviet period, when workers hesitated to follow initial instructions. Instead, they often delayed the initiation of specific directives until the final days of a production period, an organizational practice known as ‘storming’. Pay based on performance would supplant pay based on the favors of personal exchange. Because the cynicism about change initiatives could result in denial of the change, we use this variable as an empirical check to ensure the circumstances necessary for trait activation.

Resistance to change

We used the aforementioned Oreg (Reference Oreg2003) Resistance to Change Scale, which measures an individual's dispositional tendency to resist or avoid change, to devalue change generally, and to find change aversive across contexts and types of change. Consequently, the scale measures an approach to change as an element of personality generally, instead of resistance to a specific change situation and includes dimensions of routine seeking, emotional reaction to change, short-term thinking, and cognitive rigidity. Despite considerable validity evidence (e.g., Oreg, Reference Oreg2003, Reference Oreg2006; Oreg et al., Reference Oreg, Bayazit, Vakola, Arciniega, Armenakis, Barkauskiene, Bozionel os, Fujimoto, González, Han, Hřebíčková, Jimmieson, Kordačová, Mitsuhashi, Mlačić, Ferić, Topić, Ohly, Saksvik, Hetland, Saksvik and van Dam2008), the cognitive rigidity subscale of the instrument is problematic in Russia and Ukraine, but the other subscales exhibit measurement validity (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, May, McCarthy and Puffer2009a; Stewart, May, McCarthy, & Puffer, Reference Stewart, May, McCarthy and Puffer2009b). Thus, we excluded cognitive rigidity and measured RTC with 13 items associated with the dimensions of routine seeking, emotional reaction, and short-term thinking, which produced a Cronbach alpha of 0.81.

Trust in top management

We measured the level of trust that an employee has in the top management of the firm, here, the Directors General and deputies, with the overall trust subscale from Butler's (Reference Butler1991) Conditions of Trust Inventory. Notably, this measure addresses the employee's overall trust level with management, not necessarily just their legitimacy, competence, accessibility, etc. Following May et al. (Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011), we also modified the items to focus on top management because all compensation decisions are ultimately controlled by directors and their deputies. Butler (Reference Butler1991) reported encouraging validity evidence for the measure, and here the four Likert-type items produced a Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of 0.87.

Procedural justice

Following May et al. (Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011), we used five Likert-type items from Moorman (Reference Moorman1991) to measure the degree to which employees perceive a sense of consistency and fairness in organizational procedures and policies. Factor analysis of the items resulted in one problematic item that loaded weakly onto a factor separate from the others, so we discarded this item.[Footnote 1] The remaining four items loaded strongly onto a single factor and produced an alpha reliability estimate of 0.74, so we used these items to measure procedural justice.

Organizational commitment

We used the Affective Commitment Scale by Allen and Meyer (Reference Allen and Meyer1990), a measure applicable to most societal contexts (Wasti et al., Reference Wasti, Peterson, Breitsohl, Cohen, Jørgensen, De Aguiar Rodrigues, Weng and Xu2016). These items address an emotional state concerning the employee's emotional attachment, identification, and involvement with the organization. Therefore, this measure addresses the strength of the individual's affiliation with the organization, and the associated willingness to remain with the organization because the employee wants to, rather than needs to or feels that he or she ought to (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991). Allen and Meyer (Reference Allen and Meyer1996) reported considerable validity evidence for the measure. We dropped one item that factor analysis indicated problematic, most likely because it asked about discussing one's organization with people outside the firm, which would be unusual in a society marked by secrecy and in-group versus out-group considerations. The remaining seven items produced an alpha reliability of 0.78 for the scale in our sample.

Translation and Validation of Instrumentation

We capitalized on the bicultural, bilingual skills of our broader research team, which also has expertise in the local business environment, to address semantic equivalency of the instrumentation. As part of a larger research project that included firms from Russia, all items were first translated from English into Russian, in which the Ukrainian respondents are also typically fluent (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2014), particularly individuals from central and eastern Ukraine where all of the Ukrainian firms were located. The items were then independently back-translated into English by a second person, a native Russian speaker with work experience in the research context, a benefit for translation in cross-cultural research (Schaffer & Riordan, Reference Schaffer and Riordan2003). After the back-translation, this individual and one of the authors carefully reviewed all of the scale items, generating the combined perspectives of a cultural insider and an outsider that enhance the likelihood of obtaining equivalency across not only languages but also cultures (Schaffer & Riordan, Reference Schaffer and Riordan2003). Additionally, as recommended by Ryan, Chan, Ployhart, and Slade (Reference Ryan, Chan, Ployhart and Slade1999), four more bilingual Russian experts, routinely engaged in management training in the region, inspected the English and Russian versions of the instrument, and concluded that the standard of linguistic equivalency was met.

We used confirmatory factor analysis to test the factorial validity of the measurement model. First, we tested models for each of the latent factors, which resulted in all loadings being significant (see Appendix I), and acceptable fit in each model.[Footnote 2] Further, we examined a four-construct model associated with the specified research model. Although the average variance extracted (AVE) for procedural justice and OC did not meet the 0.50 threshold, their composite reliabilities (0.751 and 0.791, respectively) exceeded 0.70, another indicator of adequate convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981).[Footnote 3] The same was true for reward expectancy. To test for discriminant validity, we also ran a series of models linking the items of the four specified factors to one factor (χ2 = 7,341.82, df = 351, CFI = 0.488, RMSEA = 0.11), to two factors (χ2 = 4,775.55, df = 349, Δχ2 = 2,566.27, CFI = 0.674, RMSEA = 0.088), to three factors (χ2 = 4,722.01, df = 348, Δχ2 = 53.54, CFI = 0.677, RMSEA = 0.088) and to four factors (χ2 = 1,529.92, df = 341, Δχ2 = 3,192.09, CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.046). These fit statistics and changes in χ2 demonstrate the discriminant validity of the four measures.

RESULTS

First, we screened the respondents using reward expectancy, retaining the responses of those who either ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that pay was being linked to performance for the analysis. As described, this helps ensure that the remaining participants actually believe their firms are undergoing change, thereby activating the consequences of RTC for OC. This screening resulted in a total of 566 respondents for analysis. Although necessary for trait activation, we recognize that the application of the screen introduces the potential for indirect range restriction in the data. To the degree that range restriction occurs, it would attenuate the relationships of interest, resulting in more conservative tests of the hypotheses (cf. Aguinis, Edwards, & Bradley, Reference Aguinis, Edwards and Bradley2017).

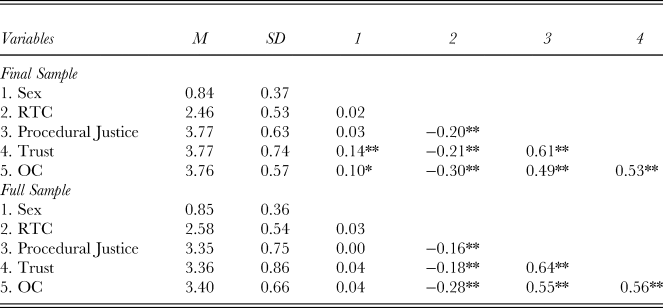

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations, for both the full and the final samples, with the only meaningful difference being that sex was significantly related to procedural justice and OC (women had higher levels of OC) in the final sample, but not in the full sample. RTC was strongly negatively correlated with procedural justice, trust, and OC. Procedural justice was positively correlated with trust and OC, and the latter two variables were also positively correlated. These correlations generally support the expectations from our theorizing.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Notes: Final Sample N = 566 Full Sample N = 1,607. * p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01. Sex: 0 = male; 1 = female. RTC = Resistance to Change. OC = Organizational Commitment

We used hierarchical regression modeling to test the hypotheses. We initially tested controls for firm, and respondent sex and age, the only individual demographics data that we were allowed to collect in the four firms, and even then, firm management required that age data be collected in 10 categories of age ranges. Although sex was not a significant predictor of OC in Lithuania (Labatmedienė et al., Reference Labatmedienė, Endriulaitienė and Gustainienė2007), sex was a significant predictor of OC when it came into the model (B = 0.15, p = 0.02), with women more committed than men. Perhaps this is due to women having less opportunity for job mobility in this patriarchal society (Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015), where interpersonal networks associated with employment tend to be male-dominated, so that job security considerations play a role in women being more attached to their firms. Firm and respondent age were not significantly related to OC. The lack of a firm effect is likely due to the high similarities of the changes underway in the firms. Respondent age was not related to OC in Lithuania (Labatmedienė et al., Reference Labatmedienė, Endriulaitienė and Gustainienė2007), but it was in Russia, with older respondents more committed (Buchko et al., Reference Buchko, Weinzimmer and Sergeyev1998). Perhaps the relationship that Buchko et al. (Reference Buchko, Weinzimmer and Sergeyev1998) identified was a function of the time of the study, but they also found that tenure was significant, and they recognized the relationship between age and tenure. Ultimately, because of the number of dummy variables associated with firm and respondent age, and because the results did not materially change without them in the model, we excluded these two variables for the sake of simplicity and readability of the results.

We mean-centered the remaining variables. Notably, all variance inflation factors for the variables were below the threshold of 2.5, with the interaction terms the highest, at 1.74. Consequently, there is no reason to believe that multicollinearity influenced the results.

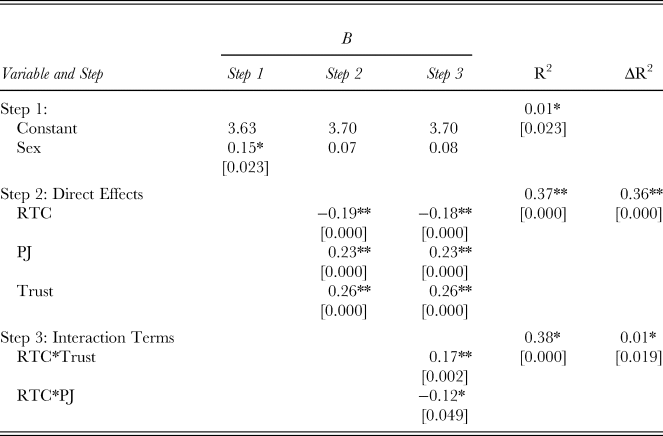

The results of the analysis are presented in Table 2. First, we entered sex, and then the predictor variables (RTC, trust, and procedural justice). We found that RTC was significantly negatively related to OC (B = -0.19, p = 0.000), as predicted in hypothesis 1. As theory predicts, procedural justice and trust perceptions were positively related to OC. Next, we entered the interaction terms (resistance to change*procedural justice, and resistance to change*trust) in step 3. Both of these interaction terms were significant above and beyond the main effects. Trust significantly moderated the relationship between RTC and OC (B = 0.17, p = 0.002), such that employees with high trust perceptions reported higher levels of commitment, supporting hypothesis 2, and high procedural justice perceptions lowered the OC of those high in RTC (B = -0.12, p = 0.049), supporting hypothesis 3.

Table 2. Hierarchical moderated regression predicting organizational commitment

Notes: N = 566. Unstandardized coefficients are reported. P-values in brackets. * p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01. Sex: 0 = male; 1 = female. RTC = Resistance to Change. PJ = Procedural Justice.

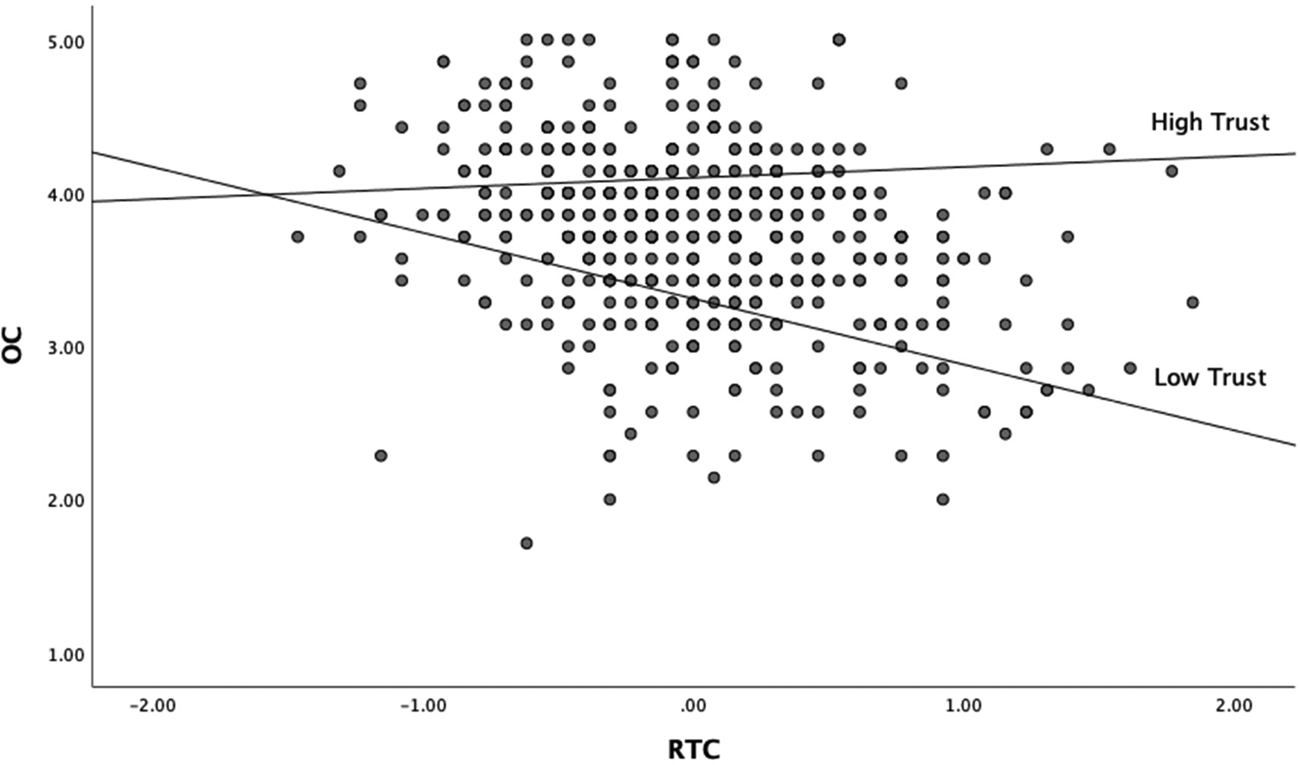

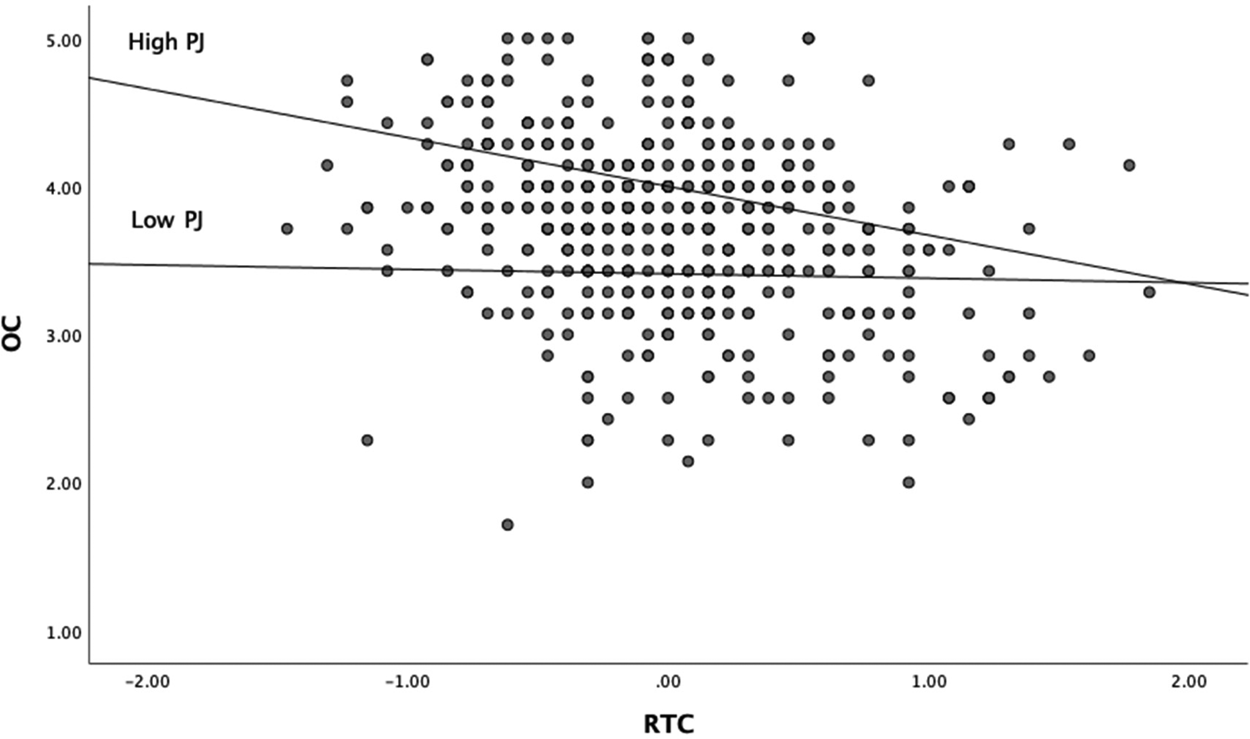

We used simple slope analysis to probe the omnibus interaction effects, not only at the conventional one standard deviation above and below the means of RTC and the moderator but also at two standard deviations for comprehensiveness. The plots are shown in Figures 2 and 3, along with a scatterplot of the values of RTC and OC, which generally comports with our theorizing about the negative relationship between RTC and OC, except for some cases of the combination of low RTC and low OC, and some at both high RTC and OC. At one standard deviation, the slope for a high level of trust (B = -0.05, t[562] = -0.84, p = 0.40) was not significantly different than zero, but the slope for low trust (B = -0.31, t[562] = -6.36, p = 0.00) was significant, results that held at two standard deviations (low trust: B = -0.43, t[562] = -4.82, p = 0.00), and the slope of high trust turned positive (B = 0.07, t[562] = 0.68, p = 0.50), as shown in Figure 2. Overall, these results do not fully support hypothesis 2, as stated, instead indicating that it is a lack of trust that has negative implications for OC at high levels of RTC. Additionally, at one standard deviation the slope of high procedural justice (B = -0.26, t[562] = -4.70, p = 0.00) was significantly different than zero, and the slope of low procedural justice (B = -0.10, t[562] = -1.89, p = 0.06) was not. At two standard deviations, low procedural justice (B = -0.03, t[562] = -0.30, p = 0.77) was also not significant, while high procedural justice remained significant (B = -0.33, t[562] = -3.51, p = 0.00). Thus, as predicted in hypothesis 3, consistently over the range of values, high procedural justice had a negative effect on OC for those high on RTC, the opposite of expectations regarding OC in the West.

Figure 2. Scatterplot of resistance to change and organizational commitment with the interactive effect of resistance to change with trust on organizational commitment

Figure 3. Scatterplot of resistance to change with organizational commitment with the interactive effect of resistance to change with procedural justice on organizational commitment

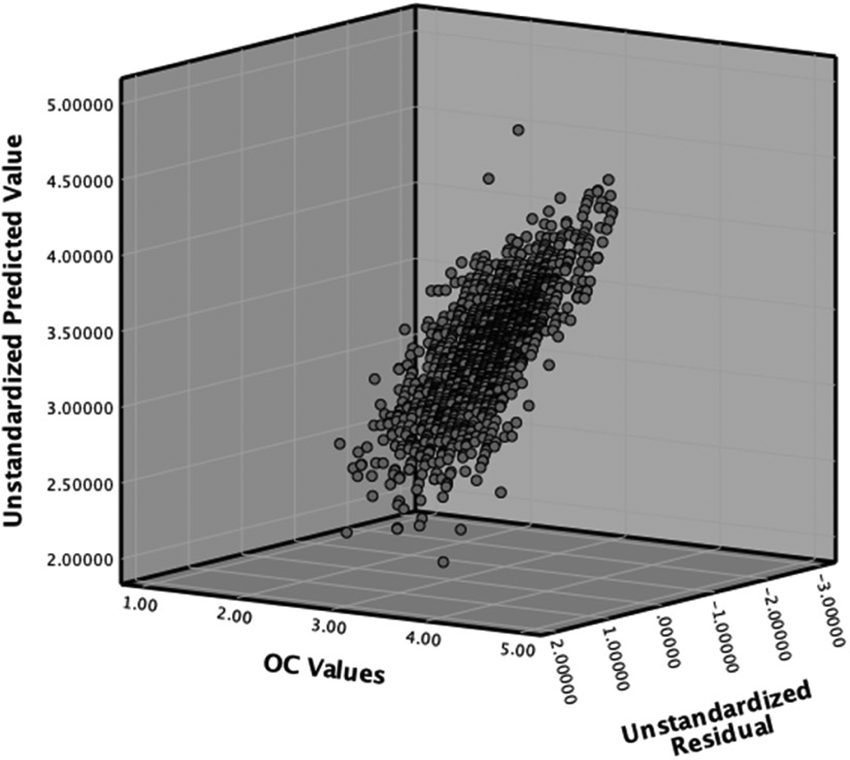

To examine effect size in the results for substantive significance, we used Cohen's (Reference Cohen1988) f 2 (f 2 = ${{R^2} \over {1-\;R^2}}$![]() ), and general conventions for regression, which address the proportion of explained variance to unexplained variance, and account for the incremental effects in the hierarchical regression model. The overall model produces an effect size of 0.61, which is of the magnitude that Cohen (Reference Cohen1988) labeled ‘large’ (i.e., 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are small, medium, and large, respectively), indicating relevance for theory and practice. Evidence concerning the adequacy of the regression is displayed in Figure 4, which combines the plots of the actual OC data, the OC predictions, and the residuals, and shows that there are only a few of the 566 cases where outcomes notably diverge from predictions, mostly at lower values of OC. With sex partialled, the main predictors also produced a large effect size (f 2 = 0.57), but the interactions, with the main predictors partialled, produced an f 2 of 0.02, which Cohen (Reference Cohen1988) termed ‘small’. Although this is typical of interactions in the social sciences (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003), the interactions are the focus of the study, and thus, warrant consideration. Importantly, with an R 2 of 0.38 in the full model, 62 percent of the variance in OC is unexplained. In evaluating effect size, we can proffer an alternative theoretical explanation that may help address unexplained variance. Given the context and results of the study, we propose that it may be useful to also consider distrust in management, as trust and distrust are conceptually and empirically distinct (cf. Kang & Park, Reference Kang and Park2017; Lewicki, McAllister, & Bies, Reference Lewicki, McAllister and Bies1998). Moreover, we focused on top management, but there may be value in examining trust/distrust of more immediate managers that takes into account the length of association between the supervisor and subordinate (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, Reference Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt and Camerer1998). We also propose that the reader consider the identified measurement issues, which are a source of error variance, especially in the multiplicative interaction terms (cf. Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003). Additionally, regarding potential omitted variables in the model, we emphasize other aspects of fairness perceptions, and later provide suggestions for research that might incorporate these and other considerations, including distrust, to improve model specification for predicting OC in change contexts, especially in this region.

), and general conventions for regression, which address the proportion of explained variance to unexplained variance, and account for the incremental effects in the hierarchical regression model. The overall model produces an effect size of 0.61, which is of the magnitude that Cohen (Reference Cohen1988) labeled ‘large’ (i.e., 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are small, medium, and large, respectively), indicating relevance for theory and practice. Evidence concerning the adequacy of the regression is displayed in Figure 4, which combines the plots of the actual OC data, the OC predictions, and the residuals, and shows that there are only a few of the 566 cases where outcomes notably diverge from predictions, mostly at lower values of OC. With sex partialled, the main predictors also produced a large effect size (f 2 = 0.57), but the interactions, with the main predictors partialled, produced an f 2 of 0.02, which Cohen (Reference Cohen1988) termed ‘small’. Although this is typical of interactions in the social sciences (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003), the interactions are the focus of the study, and thus, warrant consideration. Importantly, with an R 2 of 0.38 in the full model, 62 percent of the variance in OC is unexplained. In evaluating effect size, we can proffer an alternative theoretical explanation that may help address unexplained variance. Given the context and results of the study, we propose that it may be useful to also consider distrust in management, as trust and distrust are conceptually and empirically distinct (cf. Kang & Park, Reference Kang and Park2017; Lewicki, McAllister, & Bies, Reference Lewicki, McAllister and Bies1998). Moreover, we focused on top management, but there may be value in examining trust/distrust of more immediate managers that takes into account the length of association between the supervisor and subordinate (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, Reference Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt and Camerer1998). We also propose that the reader consider the identified measurement issues, which are a source of error variance, especially in the multiplicative interaction terms (cf. Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003). Additionally, regarding potential omitted variables in the model, we emphasize other aspects of fairness perceptions, and later provide suggestions for research that might incorporate these and other considerations, including distrust, to improve model specification for predicting OC in change contexts, especially in this region.

Figure 4. Prediction graph for adequacy of regression

Finally, we also ran the analysis on the 1,041 cases where the respondents reported less than ‘agreement’ on reward expectancy, thereby expressing doubt that their firms were actually implementing a pay system linked to performance. Notably, the main effect of RTC on OC also held (B = -0.19, p =0.00), but the interactions between RTC and trust (B = -0.03, p = 0.24), and between RTC and procedural justice (B = -0.00, p = 0.49), were not significant. We propose that these respondents, not believing that change was actually underway, were insufficiently activated with respect to their beliefs about trust and procedural justice to be relevant for OC.

DISCUSSION

The institutional disruption sparked by the collapse of the Soviet Union initiated pressure for radical organizational change. Required change initiatives, however, are often thwarted by employees (Shin, Taylor, & Seo, Reference Shin, Taylor and Seo2012), particularly in this region, where lingering institutional logics, norms, attitudes, and behaviors from the Soviet past still pose formidable obstacles to aligning the firm with new market demands. We focused on OC, which signals identification, attachment, and loyalty to the firm, under compulsory conditions of firm change because OC is correlated with job performance and a range of extra-role behaviors (Mathieu & Zajac, Reference Mathieu and Zajac1990) that are important for firm success. As expected, the results indicate that those who acknowledged the firm change and were higher on RTC were lower in OC. Apparently, organizational change disrupts the employee-firm relationship such that those more resistant to change feel less attached to the organization, and we believe this main effect would tend to hold under firm change conditions in many contexts, suggesting that the results could be widely informative about obstacles to change initiatives. This inference is the primary overall contribution of the study, as it informs change theory and also supplements the OC literature by examining the phenomenon under conditions of firm change.

We also predicted that the relationship between RTC and OC would be conditioned by the employee's expressed trust in top management and by beliefs about procedural justice. Although we anticipated that the role of trust would be similar to that shown in the West regarding OC, but perhaps more consequential due to this context, we expected that the intervening influence of procedural justice would be different than in the West, specifically, the opposite of the conclusions in the literature from Western samples such that high procedural justice perceptions are detrimental to OC. These expectations were generally supported.

Management personifies the organization to employees, and their trust in management entails the belief that managers are reliable, honest, and dependable (Butler, Reference Butler1991). This trust is emphasized in a particularist culture, where trust accrues with interactions over time, and loyalty is emphasized. People also rely heavily on personal trust in Ukraine because of the absence of reliable institutions (Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015). Moreover, given the discontinuity of the change relative to the Soviet era, the role of trust would seem conspicuous in this circumstance, particularly as employees in Ukraine are often distrustful of management, believing that they are capricious in decision and action and that they are corrupted by self-interest instead of the best interests of the firm (May et al., Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011). Interestingly, the simple slope analysis of the interaction between RTC and trust indicates that high trust does not allay the decline in OC for those high in RTC. Instead, it is the lack of trust, which is deleterious for OC among those higher in RTC. Lind et al. (Reference Lind, Tyler and Huo1997) found that trust in benevolence may play a bigger role in OC in high power distance settings. Although we did not focus specifically on benevolence, the results here suggest that the lack of trust is the more important consideration for OC in this high-power distance context. Moreover, while most research on trust assumes a zero-trust baseline, where trust is initially absent in a relationship but grows over time, our results may be suggestive of what Lewicki et al. (Reference Lewicki, McAllister and Bies1998: 439) described as distrust, characterized by ‘a fear of, a propensity to attribute sinister intentions to, and a desire to buffer oneself from the effects of another's conduct’. Lewicki, Tomlinson, and Gillespie (Reference Lewicki, Tomlinson and Gillespie2006) described distrust as a baseline state, sometimes rooted in societal cultures. In this sense, distrust moves beyond just a lack of trust, such that individuals are more resolute in their suspicions of others, and they tend to assume more negative intentions than would someone harboring only low trust perceptions. We believe that these characterizations could certainly fit the conditions in the Ukrainian context. Ultimately, it is trust that facilitates risk-taking (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995), which is particularly important under firm change conditions in the region, and consideration of trust issues, including distrust, may be integral for understanding OC in this setting. Procedural justice has a different effect.

Dent and Goldberg (Reference Dent and Goldberg1999) argued that the widespread notion that employees’ general resistance toward change thwarted organizational change overlooked the fact that employees would not necessarily resist change generally, but instead, would resist change that had negative consequences for them. Here, the implementation of standardized procedures for consistency, particularly in compensation decisions, marks a notable departure from the particularist customs of exchange where uniform rules were often distorted or ignored in determining decisions like employee pay, deferring instead to personal relationships between the supervisors and subordinates (May et al., Reference May, Stewart, Puffer, McCarthy and Ledgerwood2011; Novitskaya, Reference Novitskaya2015). Consequently, formalized rules may not decrease risk and ensure perceptions of fairness if they disrupt historical practices and relationships, but rather, practicing the more familiar, predictable social norms helps reduce uncertainties in times of change (cf. Lund, Scheer, & Kozlenkova, Reference Lund, Scheer and Kozlenkova2013). While fairness judgments can reduce uncertainty, injustice perceptions can increase uncertainty (Reb, Goldman, Kray, & Cropanzano, Reference Reb, Goldman, Kray and Cropanzano2006). Thus, we suggest that this change to standardization, especially in compensation practices, would create uncertainty that problematically alters the individual's psychological contract with the firm, prompting the fear, anxiety, and anger likely in those high in RTC (cf. Oreg, Reference Oreg2006), reducing their commitment to the firm.

There are two contending perspectives concerning socio-cultural influences in the justice literature. For instance, Morris and Leung (Reference Morris and Leung2000: 114) suggested that ‘on an abstract level, people's justice perceptions are determined by similar principles across cultures’. They also noted similarities across cultures in the consequences of procedural justice, including on OC. The results here raise questions about those conclusions, instead suggesting that perceptions of fairness and their consequences can be more context-specific, an inference more in line with the alternative position that socio-cultural values affect perceptions of procedural fairness. To wit, Lunnan and Traavik (Reference Lunnan and Traavik2009: 141) stated, ‘Our results found that even when a HR practice reflects the due process justice principle, which is considered universal, the very fact this practice is standardized can evoke perceptions that it is unfair’. Procedural justice does not universally facilitate OC, as the effects on OC are lower in high power distance cultures (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Rupp, Skarlicki and Jones2013). Collectivism emphasizes norms in predicting behavioral intentions (cf. Wasti, Reference Wasti2003), and our results also suggest that change conditions influence the role of procedural justice in predicting OC.

In addition to the inference that contextual circumstances may mean that procedural justice is not necessarily universally considered fair, the results provide useful contributions to justice theory, which generally proports that higher levels of justice are desirable. Our findings challenge that assumption. For example, fairness heuristic theory posits that people cope with a fundamental social dilemma about whether or not to cooperate with authorities so as to gain favorable outcomes over time or to be possibly exploited. In deciding about cooperation, people rely on a psychological shortcut using fairness as a proxy for trust, as fair treatment signals trustworthiness (Lind, Reference Lind, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001). Here, the results suggest that, in a relational, particularist setting marked by widespread distrust, it is not fairness typically associated with procedural justice that substitutes for trust; rather, trust issues are more immediate to a person's attachment to the firm as a signal of cooperation. Procedural justice operates separately. Similarly, uncertainty management theory, a successor to fairness heuristic theory, suggests that the consistency necessary for fairness helps people manage uncertainty. Yet there was procedural inconsistency within the particularist traditions in Ukraine, so a change to standardized practices and policies would actually create more uncertainty, especially for those resistant to change, as they consider the consequences for their personal welfare as a result of the change to procedural justice. Thus, the results here underscore that attention to context is important for justice theory, as exceptions afford opportunity to improve the capacity of theory to more broadly address relevant phenomena.

Finally, the study contributes to trait activation theory, not only in terms of the organizational change setting but also in its application. Ordinarily, activation could be assumed in studies of firm transition in most Western research settings, but trait activation cannot be assumed here because employees are dubious about announced initiatives. Thus, we recommend caution in research assumptions regarding trait activation in all settings.

The contextualization of theory can not only produce more insight into local organizational phenomena but can also leverage the extant theory, a cross-fertilization of emic and etic perspectives with value for the original theory by examining its boundary conditions (May & Stewart, Reference May and Stewart2013). Double-loop theorizing is an iterative, non-recursive process in which the local and the original theory inform each other. In this effort, exceptions to expectations hold tremendous value in understanding behavior (Johns, Reference Wyrwich2006). The results here concerning trust and procedural justice represent such exceptions and illustrate the value of using transition contexts to assess extant theory for generalizability. Institutional logic variations are important in this endeavor. For instance, not much is known about how socio-cultural context affects justice perceptions (Silva & Caetano, Reference Silva and Caetano2016), but relational concerns are paramount in determining procedural perceptions, or at least their consequences (Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988). Change in routine and procedure can disrupt these relational patterns. Overall, the results here represent the contextualization Wasti et al. (Reference Wasti, Peterson, Breitsohl, Cohen, Jørgensen, De Aguiar Rodrigues, Weng and Xu2016) encouraged for a more nuanced understanding of OC.