In 1936, after just one year of marriage, Cyril Sunseri sued to have his marriage to his wife, Verna Cassagne, annulled by a civil court in New Orleans. According to Sunseri, Cassagne was “a person of color,” and their marriage had been illegal under Louisiana's miscegenation statute. By seeking annulment rather than divorce, Sunseri was asking the court to declare that his marriage to Cassagne had never been valid. The court thus had to determine whether Cassagne possessed even “a trace of negro blood.” Sunseri alleged that Cassagne's great-great-grandmother, Fanny Ducre, was a “full-blooded negress,” while Cassagne insisted that she was an Indian. Both parties to the suit brought witnesses to testify in support of their claims, but Sunseri also adduced a trail of documentary evidence marking Ducre and her descendants as “colored.” These documents included Verna Cassagne's own birth certificate, which, despite the fact that she had been born on a “white” maternity ward, marked her as colored. In the end, the oral testimony of relatives and friends that Verna and her mother “have always been considered as being of the white race by their acquaintance in the City of New Orleans” could not win out over the documentary trail: Cassagne, the trial and appeals courts found, was Black, not white. The marriage was annulled.Footnote 1

Cassagne's fate demonstrates the power of vital statistics documents in determining racial classification and administering the racial state. Although Sunseri v. Cassagne involved a great deal of testimony about the racial reputation of Verna Cassagne, her fate was ultimately determined by the bureaucratic document filed when she was born: her birth certificate. By the 1930s, the power of birth certificates to determine the facts of a person's identity (name, parentage, exact age, sex, and race) was well established. Though scholars have often portrayed the courtroom determination of racial identity as a matter of racial reputation and association, Cassagne's case demonstrates that by the twentieth century, bureaucratic forms of knowledge could supplement and even replace local knowledge about racial identity.Footnote 2

Until late into the twentieth century, all states and localities that registered births included information about the race or color of a child's parents on the form. This was considered a basic fact of both personal identity and population knowledge.Footnote 3 But increased use of birth certificates as instruments of identification coincided with the administrative use of genealogically based blood quantum formulas to distribute (and block) access to the goods of citizenship. This was true both in federal Indian policy and state-based Jim Crow segregation. This made vital documents attractive to the architects of a racial order, who sought not only to dismantle Indian sovereignty and enforce segregation, but also to impose a Black/white order on the racially ambiguous, racially mixed communities scattered throughout the South.Footnote 4 Significantly, Cassagne claimed that she was descended not from a “mulatto,” but from an Indian. Foreclosing this possibility and reclassifying Indians as Black under state laws was critical to the success of segregation. Chief among the assets of birth registration documents was not just that they marked the race of the person to whom they belonged, but also that they were a source of genealogical information in a racial caste system based on the intergenerational math of blood quantum. Indeed, centering the use of state vital registration documents to administer policies of white supremacy supports the growing tendency to integrate postbellum policy toward Indians within the larger history of racial caste.Footnote 5

Before the twentieth century, race was rarely a matter of documentation. White Americans treated race as self-evident: you knew a person's race by looking at them. Of course, race was frequently far from self-evident. Because antebellum state laws regulated rights and freedoms according to race, individual racial status was frequently contested in the courtroom. When pre–Civil War courts had to adjudicate identity, they relied on racial performance to settle matters. For a man, whiteness was demonstrated through participation in civic rituals: voting, militia mustering, and jury duty. For a woman, her whiteness was a function of adherence to codes of respectable womanhood, sexual purity most important among them. This was not simply a matter of juries using performative clues to reckon race because documentation was unavailable; judges and juries often ignored or overruled documentary evidence of ancestry. As Ariela Gross has argued, whites had an ideological commitment to race as performance. Rather than destabilizing race, relying on performative clues bolstered “racial common sense,” the notion that race was something you could “tell by looking.” And when performative criteria were used to establish racial classification, this brought communities into courtrooms to testify about the behaviors and associations of their neighbors. Paradoxically, whites’ commitment to the stability of racial identity led them to rely on reputation rather than documentation of ancestry. By contrast, an individual's status—whether free or slave—was a matter of documentation, through evidence of ancestry, wills, bills of sale, and other legal instruments. Documentation, in other words, was more important for establishing freedom than it was for determining racial identity.Footnote 6

In the postbellum era, the tools used to establish status—free or slave—were applied to race, which became a matter of bureaucratic and legal administration rather than just reputation or association. Though many courtroom battles over racial identification continued to turn on questions of racial performance and, more important in the era of segregation, racial association, outside the courtroom the routine administration of race-based policies also relied on documentation of ancestry and identity. The use of documents to establish racial identity in a society structured by de jure segregation formed part and parcel of the bureaucratization and modernization of white supremacy, the creation of what Peggy Pascoe has called a “racial state.” Though racial classification and hierarchy were always creatures of the state, this shifted in the postbellum era as more legal and administrative power devolved from planter heads-of-households to the state, which at the same time expanded its regulatory reach through the creation of new agencies such as Boards of Health.Footnote 7 The creation of systems of vital registration also gave quasijudicial power to determine race to state functionaries from registrars to clerks of court.

The power of birth registration went beyond the simple ability to administer segregation and other blood-based policies, however. The federal and state officials who used birth certificates to sort people according to race assumed that such documents provided a disinterested, epistemologically stable source of information. But racial classification through birth registration worked less to record and stabilize the truth than to help produce it. Because state Bureaus of Vital Statistics possessed the ability to racially classify individuals on their birth documents, they redefined the racial landscape. For Native Americans, the federal government used vital registration to impose nuclear family structures in order to allot tribal land. In the case of Jim Crow segregation, state officials did this not only through the routine processing of birth registration documents that classified citizens according to race, but also by systematically denying certain babies and their parents access to the racial categories of “white” and “Indian,” foreclosing all the state and federal recognition that those entailed.

Scholars of Native American history have detailed the “intimate colonialism” of allotment and shown how state officials in the South erased Indians in order impose a Black/white binary on a multiracial South. Yet the story of how quotidian bureaucratic forms—birth certificates—played a role in the construction of racial classification and the administration of racial caste has mostly been ignored by U.S. historians.Footnote 8 Though there is a burgeoning literature on state-based forms of identification, much of this work centers on centralized European states or their colonies.Footnote 9 Recent scholarship on race and immigration in the United States has shown that documentation practices are critical to the construction of basic categories of identity, but accounts of the rise of a documentary regime in the United States are surprisingly thin. When it comes to the politics of government population knowledge, scholars scrutinize the federal, decennial census but ignore vital registration documents, in spite of the fact that census records have no probative value and are not considered a legal form of identification.Footnote 10 Birth certificates, by contrast, are not only (by statute) “prima facie evidence of facts shown thereon,” but also they have since the early twentieth century been used to establish the basic facts of identity in order to control access to school, employment, marriage, military service, social security, pensions, passports, drivers’ licenses, and myriad other rights and entitlements of citizenship.Footnote 11 For all Americans, a birth certificate has become a key that opens doors. Yet throughout the twentieth century, nonwhite Americans, rural Americans, and those born outside a hospital were less likely to have their births registered. This put both Native Americans and African Americans in a double bind. Without a registered birth, a person would have a much harder time proving his or her right to work, go to school, claim a pension, and so forth. And for registered nonwhite Americans, their birth certificates functioned as much to deny rights as to grant access to them.

The double-edged nature of vital registration for Indians and Black Americans is perhaps the best example of the dilemma of identification and documentation in general. On one hand, scholars sometimes characterize state projects of vital registration as part of the logic of what James Scott calls “state simplification,” the creation of a grid of population knowledge akin to a map of territory, and therefore an assertion of sovereignty and a form of surveillance and control.Footnote 12 It is easy to see how using birth registration documents to implement federal and state policies to end tribal sovereignty and enforce racial segregation fit with this interpretation. On the other hand, historians of identification also recognize that state-based identity registration not only serves to administer programs of rights and entitlements, but also that registration is frequently an outgrowth of such programs.Footnote 13 In other words, identity registration is more than a form of surveillance; it is a means of state recognition that unlocks the door to citizenship. It is no accident, then, that nonwhite Americans were historically the most underregistered among all births. It seems the only thing worse than being registered is the neglect of not being registered at all.

Initially, U.S. states had a patchwork of inherited systems and laws for registering vital events such as birth and death, most of which were ignored. The federal Constitution left vital registration to the states, and over the course of the nineteenth century, state laws and rates of registration continued to range from nonexistent to ineffective to, in a very few instances, such as the New England states, relatively robust. Beginning in the antebellum period, a coalition of public health reformers, physicians, statisticians, and budding social scientists led a multipronged and multidecade series of efforts to improve vital registration laws and the functioning of registration systems in the states. With the creation of the permanent Census Bureau in 1903 and the U.S. Children's Bureau in 1913, federal agencies also promoted birth registration to secure better data about the population and to promote child welfare. Despite such efforts, not until 1933 did all states (then 48) register 90 percent or more of live births, and not until after World War II did rates of registration among Native Americans reach that high. Today, although not every single birth is registered, the practice is considered universal in the United States.Footnote 14

From the beginning, every city and state that collected birth registrations required that certificates indicate the “race or color” of the parents or the child.Footnote 15 This was not necessarily for purposes of identification. Indeed, throughout the nineteenth century, Americans rarely used birth certificates as proof of identity. Instead, birth registration recorded race because vital registration was intimately linked to racial science. The state registrars responsible for collecting registration returns and issuing annual reports of birth and death statistics were constantly frustrated, however, by how casually their fellow Americans seemed to regard proper racial classification. One part of the problem was that midwives, doctors, clerks, and parents failed to report race. In 1850 Connecticut's Secretary of State complained that “color” was often left blank on birth certificates. A decade later at a meeting of Philadelphia's medical society, local physicians lamented the absence of accurate statistics on “colored births” because, as one of their group reported, “the colour in every instance [of birth] has not been designated.”Footnote 16 Likewise, throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, Michigan officials complained not just that certificates were returned with the “wrong” sort of racial classification, but also that too many were returned with no race or color recorded at all. “This imperfection in the returns is to be regretted,” the state registrar chided in 1879, “because it detracts so much from the value of the statistics.”Footnote 17

Indeed, racial categories had no stable content. While statisticians or state registrars might have agreed among themselves about a discreet set of possible answers to the “race or color” question—white, colored, mulatto, quadroon, octaroon, Indian, Japanese, Chinese, or Mongolian—returns on birth certificates made it clear that birth attendants did not share the same understanding of racial categories. Virginia's registrar complained that his state's ignorant midwives would indicate a baby's “color” with terms “such as ‘brunette,’ ‘blond,’ ‘light skinned,’ ‘dark,’ etc.” This was not just a southern complaint. In his 1874 annual report, Michigan's state registrar reprimanded local officials for their dereliction in matters of race. “The color should be stated as Black, Mulatto, Indian, White and Indian, etc., and not as African or Colored,” he grumped.Footnote 18 Nor was this simply a problem that plagued the early days of registration; errors or omissions in recording race lasted well into the twentieth century. States and the federal government tried to make racial categories more uniform. In 1920, Minnesota's state registrar provided detailed instructions to clerks on how to record race, including the fact that “B” for Black should encompass “all degrees of negro descent, as mulatto, quadroon, etc.”Footnote 19 The Census Bureau attempted to help standardize racial categories in its Physician's Handbook on Birth and Death Registration, first issued in 1939. “Racial origin should be described by stating to what people or race each parent belongs,” the handbook instructed, “as white, Indian, Negro, Chinese, etc.” And in spite of the last category—Chinese—the handbook reminded doctors not to use terms such as “American” or “Canadian” since these “express citizenship rather than a race or people.”Footnote 20

The failure to classify births according to race and the problems posed by racial ambiguity were more than a statistical annoyance. As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth, accurate racial classification of births became important not simply to test theories of racial fitness, but also to sort individuals according to the terms supplied both by state segregation and miscegenation laws, and by federal legislation distributing land and other goods to Native Americans. The instability of racial classification collided with the bureaucratic imperative to classify people on forms, to put them in a box. On the one hand, early-twentieth-century racial science held fast to the idea of race as a biological reality while, on the other hand, even proponents acknowledged that no scientific test could establish race. Racial ambiguity thus became an administrative problem that administrators of race-based policies tried to solve through recourse to genealogy—a knowledge of ancestry. This made birth certificates, which not only marked racial status, but also traced ancestry, pivotal to the racial state.

The link between identity documentation and the racial state was on full display in Indian country. From the 1830s through the 1870s, the federal government pursued the confinement of Indians on reservations, but the consensus about the wisdom of this began to fracture in the late 1870s. Ongoing graft in the administration of the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA), brutal and well-publicized military action against Indians in the West, and the exposure of near-starvation among many who received rations and annuities led reformers active in the Women's National Indian Association, the Indian Rights Association, and the annual Lake Mohonk Conference to work with politicians and OIA officials to promote a new solution to the “Indian problem.” Freedom and equality for Indians, they believed, would come through assimilation. Assimilation would require education for children, the adoption of Christianity, the reformation of gender roles through the institution of legal marriage, the end of matrilineal systems of descent, and the allotment of private property to individual Indians.Footnote 21

Allotment happened in fits and starts until the passage of the General Allotment Act in 1887, commonly known as the Dawes Act after Henry Dawes, the Massachusetts Senator and chairman of the Committee on Indian Affairs, who shepherded the bill through Congress. The Dawes Act authorized the president to order the allotment of reservations. Under its terms, each head of a family would receive a 160-acre plot of land; minors and single persons would receive smaller plots of land. Allotments were to be held in trust by the U.S. government for twenty-five years, after which time they would be converted to fee-simple property. During the trust period, allotted land could be conveyed only to an heir, with no other sale or transfer permitted.Footnote 22

Though Dawes and his allies imagined that allotment would end the federal Indian bureaucracy because it would transform Indians into citizens who had no special relationship to the federal government, Cathleen Cahill shows that assimilation through allotment led to an “increasingly complex bureaucratic structure” in the Indian Office. This occurred in part because allotment was accompanied by the delivery of didactic programs to Indians in lieu of rations and annuities. Agency farmers taught Indian men to till their fields; field matrons instructed Native women in the arts of housekeeping; teachers instructed children in English, home economics, agriculture, and elements of “civilization.” But allotment itself was also a huge administrative undertaking that involved what Rose Stremlau calls the “bureaucratic reorganization” of Indian families. Allotment attempted to construct citizens not only by breaking up tribal land and governance, but by breaking down Indian kinship structures and reformulating them as nuclear, patriarchal households.Footnote 23

Because allotment combined property transmission with family reorganization, it made population registration important to the Indian Office in new ways. As a documentary process, allotment began with the creation of a census roll, not unlike that used for rations and annuities in years past. This established a baseline register of who was eligible for an allotment. The Office wanted to know not only exactly to whom it was deeding land, but also it wanted to document the legal relationships that governed any subsequent transmission of property, from husbands to wives or from fathers to children. Documenting family relationships also ensured that no one received land illegitimately—that a woman who lived as married did not register for land as a single person, for example. This required not just scrupulous recordkeeping, but also the imposition of legal marriages duly registered and the documentation of parentage.Footnote 24

Commissioners considered documentation a sign of civilization and were likely gratified that, among other things, they taught Indians to record vital events on paper and not in memory.Footnote 25 The Indian Office and its allies hoped the creation of the original registration roll for allotment would serve as the beginning of a documentary process that would become routinized and self-perpetuating. While the agents who made the rolls often had to content themselves with oral testimony or post-hoc affidavits to determine the family relations that they should record on the allotment documents, they wanted more certainty in the process going forward. For this reason, both the government-sponsored Board of Indian Commissioners (BIC) and the Lake Mohonk Conference reformers continued to press for securing vital registration for Indians. In November 1899, the Secretary of the Board of Indian Commissioners surveyed all Indian Agents about the process of allotment, and he requested written replies to his circular letter. He wanted to know how they thought it was working in practice. Among the areas of inquiry, he asked agents to describe whether they kept a register of marriages, births, and deaths of allottees, and also to note any “evils from lack of registration and records” that they might encounter. The BIC then printed the responses of the agents. Respondents who worked on allotted agencies were more likely to keep records of births, marriages, and deaths, with some noting that the practice had begun only with allotment.Footnote 26 Many agents also detailed the “evils” of improper or inadequate registration. The agent from the Sisseton Agency noted that “an Indian does not trace his relationship as a white man would, but he is liable to adopt a father or a mother,” and this would cause trouble “when the time comes to deliver deeds to this people.” An agent with the Pueblo and Jicarilla claimed that “on account of lack of registration and records, it has been impossible to deliver a larger number of the patents.” Still others complained of another problem—the inconstancy of Indian names. At least one agent was content: at the Mescalero Apache reservation, he reported, “These Indians adopted white people's mode of naming children in 1896, being forced to by the agent.”Footnote 27 This meant that wives and children took the husband's name, and it had helped keep the record books straight.

Whether they claimed to keep accurate records or not, most agents echoed the opinion of the Siletz Agency superintendent, who wrote that “the Department should issue an order giving the form and manner in which the records of births, deaths, marriages, and divorces should be kept on each reservation, thus securing a uniformity of record for the whole service.”Footnote 28 The BIC and the Lake Mohonk conference concurred. In 1900, the Lake Mohonk Conference adopted a plea for vital registration as part of its platform. President Gates professed shock that the federal government had done “nothing to render family life sacred” among Indians by creating marriage and birth registers. These, he argued, were agents of “social purity” that created and perpetuated family groups. Proper registration would have a “marked influence in civilizing the Indians by adding dignity to family life.” To the moral arguments, Gates also added economic ones, since registration would “save the Government great expense and trouble in preventing a mass of litigation to determine the heirs” of allotted lands.Footnote 29

On May 15, 1900, the Chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, John Thurston of Nebraska, introduced a bill for the regulation of marriage among Indians and the registration of vital events. The bill would have required the Office of Indian Affairs to provide every agency with a record book; agents would be required to record all existing marriages, complete with all children, and to link the registrations to allotments. The legislation also made it the agent's duty to record all births and deaths. As they introduced a new regime of private property, the act of registration would create a form of legal identity that would remold Indian naming, kinship, and inheritance practices into Anglo legal traditions. Thurston's bill never made it out of committee, but both Gates and the BIC urged the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to use his executive powers to put in place the legislation's provisions by fiat.Footnote 30 In 1901, Commissioner William Jones did just that.Footnote 31

In spite of such directives, the birth registration rates of Native Americans remained the lowest among all Americans throughout the twentieth century. Commissioners of Indian Affairs and heads of the Indian Health Service periodically issued circular directives reminding Indian Agents to do a better job with registration, and they corresponded with individual agents, admonishing them for a job poorly done. The Office also tried to promote birth registration directly to Native Americans and to change birth practices among Native women in ways that would yield higher rates of birth registration. Both strategies are exemplified by the 1916 “Save the Babies” campaign initiated by Commissioner Cato Sells. Meant to tackle disproportionately high rates of infant mortality among Native Americans, the campaign also promoted birth registration, which the U.S. Children's Bureau had begun to argue was a critical tool in the prevention of infant mortality. As part of its campaign, the Office created and distributed a pamphlet, Indian Babies: How to Keep Them Well. Among the advice about prenatal care, and proper infant feeding and care, the handbook admonished Indian mothers to have their baby's births registered (Figure 1). “Such a record may help you to prove some day that it is an American citizen,” the booklet explained. “It will prove how old it is, and establish the right to vote, to marry, to make contracts, to establish claims to inheritance, etc.”Footnote 32

Figure 1. Instructions to Native American women on reservations to have births registered and to breastfeed. Source: Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Affairs, Indian Babies: How to Keep Them Well (Washington, DC, 1916), 5.

Beyond appealing to Native mothers to register their babies’ births, the Office tried to change birth practices among Native women in ways that would yield higher rates of birth registration. Throughout the United States, births attended by physicians or licensed midwives were much more likely to be reported than those attended by kin or neighbors. As part of the “Save the Babies” campaign, Sells instructed his subordinates to promote physician-attended and hospital births among Native American women, an outgrowth of which would be increased birth registration. Sells increased the number of hospitals on agencies and urged his physicians to admit birthing mothers. “I am particularly anxious that our hospitals shall be used for mothers in childbirth,” he wrote to his superintendents.Footnote 33 Sells bragged in 1917 that his health initiatives had reduced the influence of traditional healers, especially the medicine man. This was important because, as Sells put it, “to the extent that he has flourished his tribesmen have been nonprogressive, never reaching their possibilities, suffering for want of the hospital, physician, nurse and field matron.”Footnote 34

Shifting childbirth from home to hospital comprised part of a longer campaign by the OIA to replace traditional healing with western, allopathic medicine. Controlling Native women's relationship to reproductive health became central to that larger shift.Footnote 35 During the interwar years, the Indian Health Service (IHS) sent public health nurses to reservations, a move that aided both the medicalization of birth and the registration of newborns. IHS nurses were supposed to impart American housekeeping and childrearing practices to Indian women. Under the aegis of health, such practices were framed as not only civilized but also medically correct, sanitary, and life-giving.Footnote 36 On the Fort Belknap reservation in the early 1930s, the field nurse Miss Holzworth tried to visit all expectant women “at some time during pregnancy, and urge[d] hospitalization.” She also made sure that such women received prenatal letters from the Montana State Board of Health, which very likely also would have urged both hospitalization and birth registration. For those women who still delivered at home, Holzworth sometimes attended them, but always “secure[d] data for birth certificates.”Footnote 37 The agency hospital also gave every woman who delivered a baby there a “Hospital Birth Certificate, which has a picture of the hospital on it, and is signed by the Superintendent”Footnote 38 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Fort Belknap Agency Hospital Decorative Birth Certificate, c. 1934. Source: folder: 002129-004-0806, Reports on Medical and Nursing Activities, Indian Health and Medical Affairs, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Central Classified Files, 1907–1939, ProQuest History Vault (accessed Dec. 19, 2018).

The work of field nurses across the West was similar to that of Miss Holzworth at Fort Belknap. At Fort Hall Agency in Idaho, the field nurse Mrs. Hughes also made it her business to find out who was pregnant and pay a visit. After a baby was born, Hughes visited the new mother at home and instructed her in infant care. If the baby had been born at home rather than in the agency hospital, Hughes would make out a birth certificate for it. But according to the reports of the OIA supervisory nurse who came to inspect at Fort Hall, by 1935 over 80 percent of babies at the agency were born in the hospital, up from just over 50 percent two years prior.Footnote 39 Though many Indians resisted giving birth in hospitals and preferred midwife-assisted home deliveries, these numbers were fairly typical. By 1940, 80 percent of Indian babies were born in Indian Health Service or IHS-contracted hospitals, a rate well above the national average.Footnote 40 And, at least in the eyes of IHS medical personnel, hospital births increased the fidelity of birth registration. At Fort Hall, the agency physician assured the superintendent that “the matter of births and deaths should be free from error for the Agency Hospital” since he filled out proper forms for all the vital events that occurred there. To the extent that some births went unregistered they were from the “rest of the agency,” outside the hospital. This claim was echoed by other IHS physicians across the 1930s. Whatever happened in the hospital, they felt sure that they had accounted for, and for whatever happened outside it, they offered no guarantees.Footnote 41 Data collected by the National Office of Vital Statistics in 1950 affirmed agency physicians’ claims. Among Indians, physician-attended home births or hospital births were more than twice as likely to be registered as those occurring at home without a physician.Footnote 42 Changing Native birth practices changed Native registration rates.

Birth registration not only established the naming practices and family ties necessary for the transmission of property according to Anglo-American legal norms, but it also helped the Office of Indian Affairs to calculate the “blood quantum” of individual Indians. Modifications to the Dawes Act and subsequent changes in policy made this genealogical exercise critical to the functioning of the Office. Under the terms of the Dawes Act, individual allotments were held in trust for a period of twenty-five years, after which they became fee simple patents that individuals could dispose of as they wished. Passed in 1906, the Burke Act modified the terms of allotment in ways that made blood quantum into a system for determining control of property and citizenship. The Act provided that Indians who were allotted in the future would not become citizens until their trust period ended. At the same time, the Act made the trust period more flexible: it gave the president the power to extend the trust period beyond twenty-five years for individuals, but also to release any Indian deemed “competent and capable of managing his or her affairs” from trust period early. As the Act was made into policy by the Office of Indian Affairs, blood quantum became what Rose Stremlau calls a “filing system for human beings” to determine competency.Footnote 43

During the 1910s, the commissioners of the Office intended to have as many Indians as possible declared competent, given fee simple title, and thrust out of wardship into citizenship. To expedite the process, the Office settled on a simple formula: anyone with less than one-half Indian “blood” would be given a patent before the trust period ended; anyone with one-half or more Indian blood would have to undergo a competency hearing. Though the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” who had lands in Oklahoma were governed by separate agreements with the U.S. government, there too the administration of Indian property was reduced to a blood quantum formula. In 1908, Congress “removed all restrictions (including those on homestead and the lands of minors) from the allotments of intermarried whites, freedmen, and mixed-blood Indians with less than half Indian blood.” Those with one-half to three-quarters Indian blood could sell their surplus lands but not their homesteads. Finally, an order from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1919 removed all restrictions from allottees with one-half Indian blood.Footnote 44

Allotment ended in 1934 with the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act, but this did not end the federal government's investment in using blood quantum to administer policy. The Act not only stopped privatizing Indian land, but also prohibited the alienation of previously allotted land, allowed the return of surplus lands to Indian tribes, enabled the Secretary of the Interior to purchase land to enlarge reservations, and created a process through which tribes could formally organize for self-governance. It also provided educational loans to tribal members and called for preferential hiring of Native Americans in the Indian Service. At the same time, the Act made blood quantum into the federal legal standard for defining an Indian. For purposes of gaining access to federal resources, an Indian was a member of a recognized tribe under federal jurisdiction, a descendant of such a person, or any person with one-half or more Indian “blood.”Footnote 45 Narrow, blood-based definitions of Indian status reduced federal obligations to Indians by reducing the number of people to whom it owed land, annuities, or other entitlements.Footnote 46

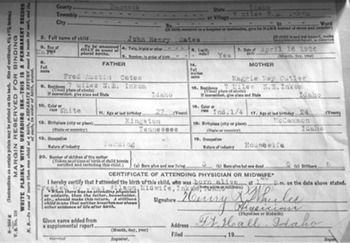

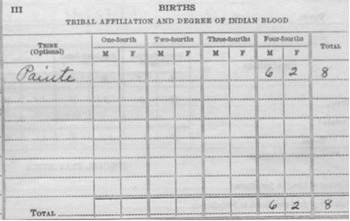

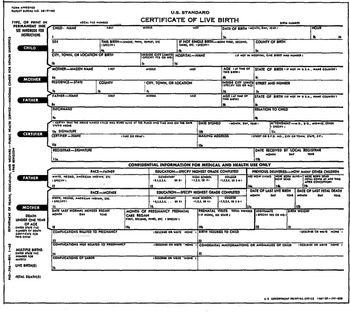

Unfortunately for administrators at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the standard Census-issued certificates of birth were ill-equipped to reckon “blood.” Though the Census Bureau's standard certificate included blanks to indicate the race or nativity of a baby's parents, they did not have blanks to indicate tribal membership or degree of “blood.” Federal officials repeatedly reminded superintendents and agency physicians to include this information on birth certificates. In May 1928, for example, Assistant Commissioner for Indian Affairs E. B. Meritt wrote to J. A. Buntin, the Superintendent of the Kiowa Agency, asking him to “kindly give the birth and death reports of your jurisdiction more careful attention.” Meritt noted that Buntin omitted information from the birth certificates he sent to the Office, including “the tribe and degree of blood” of both parents on the birth certificate. According to another letter on the matter, such information was “often omitted” by superintendents.Footnote 47 Indeed, the Office frequently sent back birth certificates to the agencies requesting tribe and degree of blood.Footnote 48 In response to one such letter, the superintendent of the Carson Agency in Nevada sent back missing tribal and blood quantum information, noting for example that a baby born December 19, 1927, was “3/4 Washoe Indian,” while another born in March of that year was “full blood.”Footnote 49 In order to record this on birth certificates, agency employees had to insert fractional information into the blanks for “race or color” on the forms (Figure 3). That agents frequently failed to notate blood or tribal membership is not surprising since the forms were created for general use, not for the administration of federal policies that differentiated among Indians based on a fictional quantum of blood. By contrast, when the Office designed forms for its own use, it differentiated births in the precise fractional terms that mattered to its own record keeping and administration (Figure 4).

Figure 3. A birth certificate from the Fort Hall Indian Agency. Box 16 on this certificate shows how employees of the Office of Indian Affairs had to retrofit state forms to include blood quantum information. Source: Fort Hall Box 2, Central Classified Files, 1907–1939, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, RG 75, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

Figure 4. Excerpt from Physician's Annual Report, Pyramid Lake Indian Agency, Dec. 31, 1930. Unlike the standard certificate of birth, the Office of Indian Affairs’ own forms called for the calculation of blood quantum. Source: Box 1, Physicians’ Annual and Semiannual Reports, 1925–1930, Records of the Health Division, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, RG 75, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

In spite of the directives of the Office of Indian Affairs, the repeated pleas of the BIC, and the apparently earnest efforts of some agents, neither marriage nor birth and death registration became uniform across Indian agencies in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries. Allotment initiated a new regime that rested on legal marriage, patriarchal households, and the adoption of Anglo-America naming, kinship, and inheritance patterns. The BIC and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs wanted marriage, birth, and death registration to help this system function. To the extent that agents put some form of registration in place, it was a technology that, along with private property and schooling, sought to individuate and assimilate Native peoples.

The reckoning of Native American blood that accompanied allotment functioned inside and supported the system of racial segregation. As states redefined what it meant to be “Black,” usually downwards to ever-decreasing fractions including the infamous “one-drop” rule, the allotment procedures of the OIA differently registered those Indians who were also of African descent. Among tribes who had held slaves—the so-called Five Civilized Tribes—commissioners from the Office of Indian Affairs forced descendants of former slaves, no matter their degree of Indian “blood,” to register on “freedman's rolls” rather than the “Indian rolls” that recorded quantum for purposes of allotment. Within a Jim Crow racial order, Black “blood” trumped both white and Indian ancestry. Just as anyone with African American ancestors could never be “white” according to the state laws governing access to schools, marriage, and other rights, so too no one with African ancestry could be fully “Indian” for the purposes of federal allotment and enrollment policy. When it came to land alienation, “freedmen” (no matter their actual ancestry) could sell land before those with one-half or more Indian blood.Footnote 50

Much as the creation of systems of vital registration accompanied the creation and administration of the Dawes Act in Indian country, the enforcement of racial segregation accompanied the efforts of both federal agencies and civic organizations to improve birth and death certification. In 1912, for example, the Atlanta Constitution reported that members of the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) were working to pass a bill for compulsory birth registration in the state. DAR member Mrs. William Lawson explained that knowing one's genealogy was particularly important in the South “owing to our large negro population.” She described traveling in Latin America and seeing “the fearful mixture of races.” Knowing that Georgians would like to put a stop to such racial mixing, she predicted that “the time will come when the need to prove your Anglo-Saxon descent will become imperative.”Footnote 51 Likewise, in 1917 Kentucky physician and public health reformer W. L. Heiser urged the men and women of his state to enforce compulsory birth registration lest “our grandchildren and great-grandchildren will be marrying persons having Negro blood in their veins.”Footnote 52 Indeed, being able to prove one's whiteness was critical to access a whole host of race-based rights and privileges, and vital registration would be instrumental in the effort to maintain racial purity in the postbellum South.

Nowhere were the ideological links between vital registration and administration of the racial state made more apparent than in Virginia. In 1912 the state reformed its floundering registration system by creating a State Board of Health. The Board included a Bureau of Vital Statistics (BVS) and a State Registrar to enforce a new vital statistics registration law. Assistant Registrar Walter Plecker assumed the job of enforcement; he became State Registrar in 1914 and served in the post until 1946. During those years he used his post not only to collect and broadcast racial statistics, but also to engage in racial purification through racial classification. Plecker and his efforts to police interracial marriages and to deny recognition to Virginia's indigenous peoples are notorious. Yet the foundational role of vital documents and birth certificates in particular to his machinations is less well understood.Footnote 53 In Walter Plecker's hands, racial purity was the product of properly recorded births.

Plecker made common cause with fellow Virginians John Powell and Ernest Cox, founders of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America, to urge his state to pass the antimiscegenation Racial Integrity Act (RIA), which it did in 1924. The Act defined “white,” “Negro,” and “Indian” not only for purposes of marriage, but also for “school attendance and for all other purposes.” In the original version of the RIA, Powell and Plecker included a provision that would have required every Virginian to have a racial registration document. This provision was stripped from the final bill, but the final act forbade marriages between whites and nonwhites except those possessing “one-sixteenth or less of the blood of the American Indian and … no other non-Caucasic blood.” In 1930, the Act was amended to “define a colored person as one with any ascertainable negro blood,” the so-called one-drop rule. The RIA also directed the State Registrar to prepare “registration certificates” to record the racial history of any person born in Virginia before 1912 who lacked a birth certificate. Writing in favor of the Act, Plecker argued that his office constituted the “greatest force in the state today combating this condition [racially mixed marriages],” but it would have the power to act with greater clarity and force under the terms of the RIA.Footnote 54

Plecker believed not just that the negro and white races should remain separate, but also that in the Southeast, those who claimed to be “Indian” were really descendants of African Americans trying to, as he put it, “pass over” into the white race. Indeed, he believed that there existed no true Indians in Virginia at all, and that anyone who claimed the mantle was simply trying to cover up Black blood going back generations. Plecker granted that though some in Virginia might be descended from the state's original inhabitants, all such were also at least partially descended from illegitimate unions between white men and Black female slaves, and thus had to be classified as “negro” under the terms of the RIA.Footnote 55 Plecker therefore saw his job not only to make certain that all those with “negro” blood became identified as Black in order ensure white racial purity, but also to stamp out “Indian” as a possible racial category in Virginia.

As soon as the RIA passed, Plecker set to work; he was “impressed with the immensity and importance of the job which the legislature has given me to do.” Plecker's employer, the State Board of Health, also recognized that the Bureau of Vital Statistics’ work was “enlarged” by the RIA.Footnote 56 For Plecker, ensuring accurate registration of vital events meant investigating families’ histories—or at least some families’ histories. To that end, Plecker and his clerks scoured registration records as they came in and took great pains to map the genealogies of families they believed were trying to pass as white or Indian when they were actually “negro.” Like the racial regime of allotment in the federal Office of Indian Affairs, Plecker too used African ancestry to override “white” or “Indian” blood. He identified several areas of the state where he believed that “families of mixed blood” tried to pass themselves off as white, Native American, or a mixture of the two. With the help of local clerks of court, registrars, and commissioners of revenue, the BVS focused its attention on Amherst, Rockbridge, and Augusta counties as sites of centuries-old racial mixing. In communications with the public, Plecker warned that perhaps as many as 20,000 “near white people” resided in these areas, sometimes sending their children to white schools and marrying white people. Though such families could at times get their offspring registered at birth as white or Indian, Plecker believed that all of them were properly classed as “negro” because of their descent. In order to protect the integrity of the white race, Plecker and his clerks in the BVS compiled a list of surnames from families they believed stemmed from racial mixture and carefully checked any birth, marriage, and death records sent to its office under these names. Plecker also distributed this list of surnames, organized by county, to all the state's registrars, physicians, health officers, nurses, school superintendents, and clerks of court, urging them to “report all known or suspicious cases” to him along with “names, ages, parents, and as much other information as possible.”Footnote 57

Plecker asked for “as much other information as possible” because he intended to exhaustively document the racial genealogy of Virginia's “mixed blood” families. As he explained, since there is no blood test for race, the only proof “is by genealogical records.”Footnote 58 Plecker used a combination of records to establish family trees for the families with surnames he considered suspect. He had birth and death records covering the period 1853 to 1896 and marriage records beginning in 1853, all of which listed the race of registered parties. Plecker was also delighted to discover the work of the pathbreaking African American historian Carter G. Woodson, who in 1925 published the book Free Negro Heads of Families in the United States in 1830 under the auspices of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. Plecker distributed information from Woodson's book to clerks in Virginia counties asking them to “look them over and tells us all of the names that now figure as Indian or white” but who were listed by Woodson as free negroes in 1830. “We believe that this will be of great value to us in establishing the fact that many of these people were in 1830 considered free negroes, who are now claiming to be pure Indian and white blood.” Plecker and his clerks also used other state and federal records that, while they were not vital registration documents, categorized enumerated persons by race. These included tax rolls stretching back to 1785, federal census records, and rolls of eligible voters created during Reconstruction by the “army of occupation.” This latter record Plecker considered particularly damning since it was an act of self-identification intended to grant a privilege. “Practically of these people who are now calling themselves Indians rushed in to register themselves as negroes in order to become voters,” he explained. It was only now, when being a “negro” was tied to a prohibition rather than a privilege, that such families wanted to be considered “Indian.”Footnote 59

Plecker believed that documents could supplant informal knowledge—in this case physical appearance or racial reputation—with a more objective and durable truth. However people might look, whatever they might say about themselves, and however they might be regarded by their neighbors, the documentary record would tell the truth about a person's lineage. But by using supporting documentation to vet racial claims on new registrations, Plecker believed that he could preserve the effectiveness of vital documents as a tool in the administration of white supremacy. His office therefore used this genealogical method both to create racially valid vital registration documents in the present and to use other kinds of official records to “correct” past registration. The move was legally innovative, epistemologically radical, and socially disruptive.

The BVS's genealogical method surfaced in its correspondence with the state's doctors and midwives, particularly those who practiced in the areas of the state that Plecker considered racially suspect. In August 1924, for example, Plecker wrote to Dr. Robert Glasgow in Lexington, Virginia, to inquire about a birth he had registered in March of the same year. The baby's surname (Beverly), that of the midwife who attended the birth (Hartless), and the place of birth (Amherst County) all suggested to Plecker that the baby might be improperly classed as white. Plecker explained to Glasgow that the baby's surname “is that of a numerous family of mixed races living in that County,” and he went on to explain that the family “are probably a mixture of three Cherokee Indians of North Carolina passing back home from a visit to Washington” who remained in Virginia “and mated with white women, their children afterwards mating with negroes” in a pattern that continued over generations. The midwife's surname was also “one which appears frequently among these people,” adding further suspicion to the case. Plecker pleaded with Glasgow to “take the proper steps to see that these people are not classed as white unless they are known absolutely to be such.”Footnote 60 Plecker sent similarly threatening letters to midwives.Footnote 61

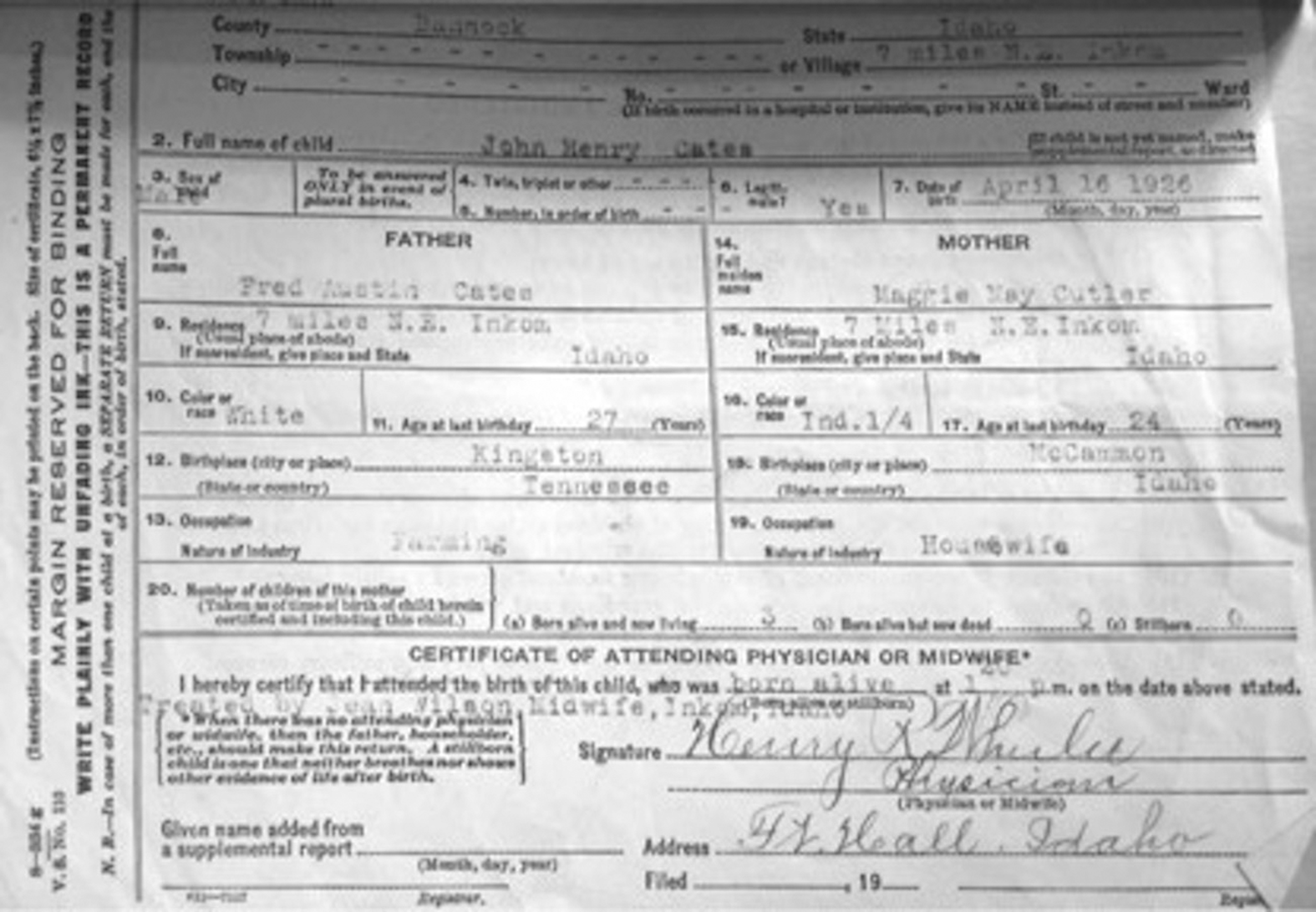

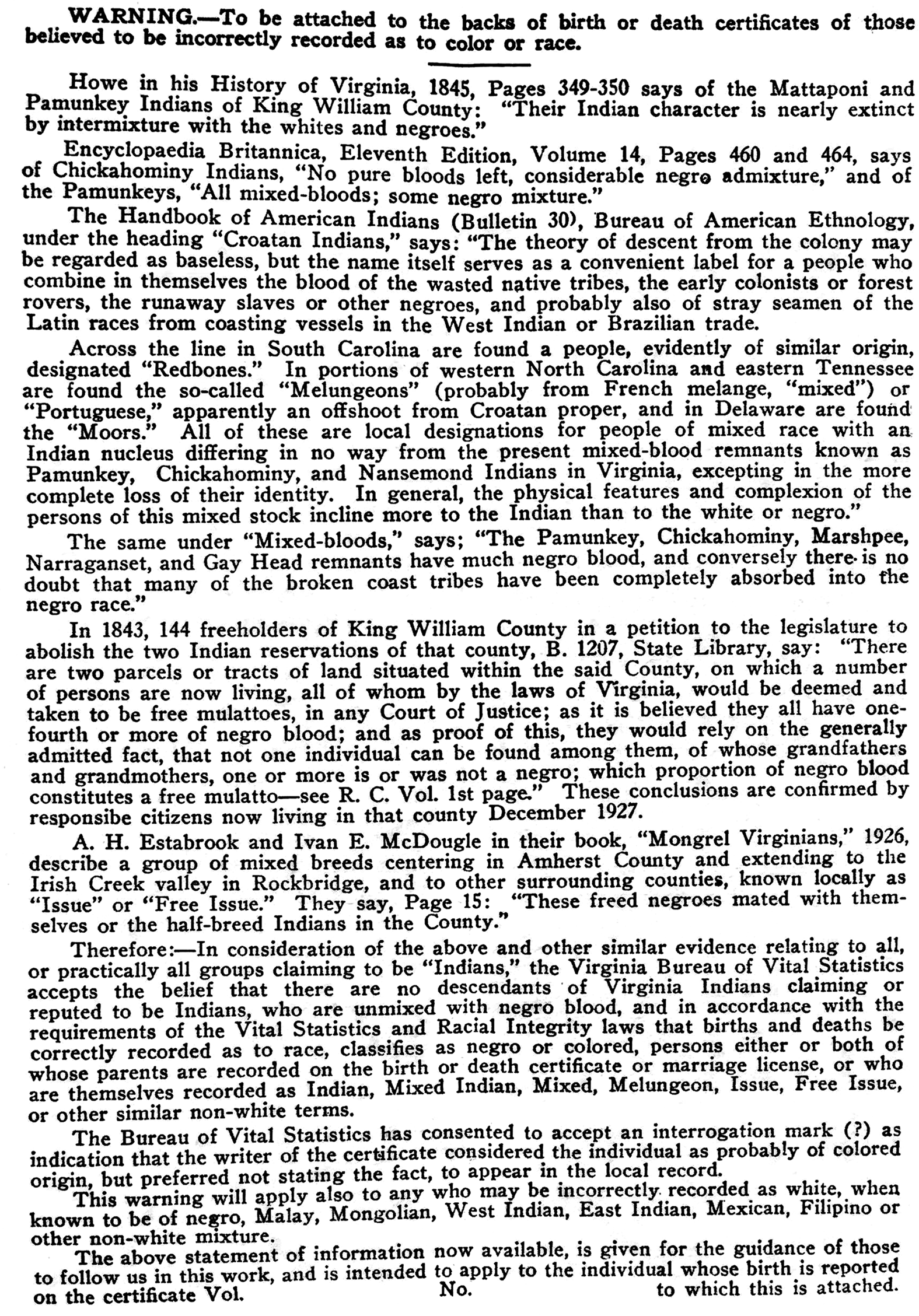

The sand in the gears of the RIA's proper functioning remained, in Plecker's mind at least, those cases in which a family or some of its members had previously been registered as white or Indian. The BVS wanted to stop such families from registering new children as white, and it did not want to issue “white” birth, death, or marriage certificates to families it believed had been registered as “white” under old rules, but who would be “colored” under the RIA. When birth certificates had been filed many years prior under a different set of rules for racial classification, Plecker's office could not refuse to issue those it believed incorrectly identified persons as “white” or “Indian” when they were actually mixed with “negro” blood. In those cases, the BVS issued the certificate but appended a letter of “warning” to those “believed to be incorrectly recorded as to color or race” (Figure 5). This letter at length cited from histories of Virginia alleging to show that there were no pure-blood Indians in the state going back as far as the 1840s; all were mixed with negro blood. Therefore, the bearer of the certificate to which the letter was appended, though he or she may be listed as “Indian, Mixed Indian, Mixed, Melungeon, Issue, Free Issue,” should be regarded as “negro or colored.” Lest there be any confusion, the letter ended by stating that the information contained therein “is intended to apply to the individual whose birth is reported on the [attached] certificate.”Footnote 62 Plecker usually also gave detailed genealogical information on the back of the certificate, citing “old records” that showed that the bearer's ancestors had been registered as colored in previous state documents (Figure 6). Beyond publicly declaring that the BVS did not consider the bearer of the birth certificate to be either white or Indian, Plecker also made certain that his office's genealogical evidence was bound into its own permanent volumes of birth records. This practice ensured that in the future, whenever a clerk searched for a birth record that Plecker believed deserved reclassification, she would find the genealogical evidence that prior generations of BVS clerks had assembled.Footnote 63

Figure 5. This was all-purpose statement that the Virginia BVS attached to the back of birth certificates it believed contained an incorrect racial designation. James R. Coates, Records Concerning the Ancestry of Indians in Virginia, 1833-1947, (31577), Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA. In other cases, the BVS adduced specific evidence of the bearer's descent from a non-white person (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. The transcript of the statement that the Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics appended to the back of Edward Willis's birth certificate. In this and other cases, Plecker detailed the reasons the bearer of the certificate could not be regarded as white or Indian, the initial racial registration notwithstanding. Box 42, John Powell Papers, 1888–1979 (7284, 7284-a), Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, VA.

The consequences of using vital documents to adjudicate racial identification were profound. In Virginia, two of the most important institutions that birth certificates in particular helped segregate were education and marriage. But the power of birth registration went far beyond the simple ability to administer segregation. Because Plecker had the authority not just to provide information to institutions about what existing birth registration documents said, but also to alter documents in accordance with his office's genealogical research, the BVS possessed the ability to redefine the racial landscape of Virginia by denying access to the racial category of “Indian.”

Documentary control of education worked in several ways. First, the Virginia State Superintendent of Public Instruction recommended to all school districts that they ask pupils to provide proof of birth registration in order to enroll in school.Footnote 64 As more towns, cities, and counties complied, the racial identification on the certificates functioned as a gate that funneled children into either white or colored schools. Plecker also sought to ensure that no children “incorrectly” registered as white or Indian were permitted to attend white schools, and he used genealogy to scrub the record, and the schools, clean. Just as Plecker used his list of surnames in certain counties to warn local clerks, registrars, and birth attendants not to falsely register these families as white, so too he warned school authorities not to allow children from such families to attend white schools.Footnote 65 In one such case, Plecker wrote to a superintendent in Lexington warning him that the Tyree children, who had been allowed to attend the white school, were actually part of a “large group of mixed breeds of negro extraction.” Plecker also wrote directly to Mrs. Tyree to tell her that she could neither receive birth certificates for her children marking them as white nor could she enroll them in white schools.Footnote 66

Finally, the BVS responded to requests for information from local school authorities and used its documents as evidence in contested cases. Plecker encouraged schools to bring questionable cases to his attention, at which point his genealogical machinery would produce the evidence required. “We have usually been able,” Plecker reported, “to furnish district superintendents the facts sought by them” and thus to prevent “near-white families of negro descent” from entering white schools. This assistance even extended to school officials in neighboring states where Virginians and their children had moved.Footnote 67

BVS's vigilance paid off as families who sought to enroll children in “white” schools were denied entrance. This not only involved the sorting of new enrollees into the “right” schools, but also reshuffling the racial deck according to the racial definitions of the RIA and the genealogical information provided by the BVS. Indeed, as soon as the law took effect, some children who had been attending white schools “for several years” were suspended “pending an investigation as to whether they were white or colored.”Footnote 68 In 1925, Plecker responded to a letter from Kate Robinson “begging that your children be allowed to go to the white schools.” He explained that because of what he believed was her racial heritage, it was not possible.Footnote 69 In Richmond, the white schools kicked out several families who identified as Chickahominy Indians and whose children had been allowed to attend.Footnote 70 In 1930, Mascott Hamilton wrote to Plecker, infuriated that the BVS had marked his family as colored and that his children now attended a segregated colored school. “I am glad,” Plecker replied and refused to reclassify the family. In some families, one branch might be recognized as white and the other classed as colored. Such was the case with the Ogdens of Amherst County. While Warren Ogden's children were suspended from the white schools, their cousins in Richmond and Lynchburg continued to attend segregated schools as whites.Footnote 71

Plecker regarded school segregation not only as an end in itself, but also as instrumental to another of the state's top priorities: the enforcement of miscegenation law. As he explained in a letter to an attorney, the problem was not simply that colored and white children might sit side by side in the classroom. Rather, if children with any negro blood were “permitted to attend white schools they naturally form white attachments, with the result of afterwards intermarrying into the white race, thus establishing a line of mixed breeds to give trouble to every one.”Footnote 72 Given the slippery slope from shared schooling to racial amalgamation, birth certificates helped to create friction on the slope. Accurate birth registration ensured the prevention of intermarriage in the future. When Plecker reminded birth attendants and local registrars about their duty to properly record race on new registrations, he told them that if they had any doubt about the race of either of the parents, hence of the child, they should consult the local clerk of court because he was responsible for issuing marriage licenses in the future and thus would be materially interested in settling any racial ambiguity. In his annual report for 1926, Plecker also averred that he aimed to prevent miscegenation by “securing proper and exact registration which he can prove in courts when called upon so to do.”Footnote 73

In addition to providing a form of preventative gatekeeping, birth records had a second important function because they could be used to prove that one of the applicants for a marriage license was nonwhite while the other was white. In Connor v. Shields, this is how Plecker argued that Dororthy Johns had negro blood in her veins. Plecker used similar tactics to contest the marriage of Benjamin Beverly to Dollie Garrett, and of Cecil Spitler to Ella Anna Clark, all of whom declared themselves as white on their applications for marriage licenses.Footnote 74 In such cases, the BVS could adduce either the birth certificate of one of the applicants or use the genealogical method and provide evidence that an ancestor of an applicant was considered nonwhite in a past act of registration.

Finally, when parents registered the birth of a child, this could trigger the BVS to inquire about the legality of their marriage. This might be because, as in the case of Lawrence Sperka and Ida Hartless, one of the parents had a surname that the BVS considered suspect. In October 1930, Plecker penned a letter to Mr. Sperka about the birth certificate he had recently filed on behalf of his newborn. Plecker explained that the baby's mother might be from a “mixed blood” group of Hartlesses who congregated around Buena Vista and Irish Creek. His letter included a questionnaire for the couple to fill out that would establish her genealogy. “In order to establish the legality of your marriage,” Plecker wrote, “will you please advise as to which family your wife belongs.” He warned Sperka that “If [she belongs] to the family of mixed breeds, your marriage is not legal.”Footnote 75 Because of the BVS's use of birth certificates to trigger investigations into marriage, parents who obeyed the law's requirement to register their children's births might find their marriage declared illegal and their children officially marked not only as colored, but also as illegitimate.Footnote 76

Though Plecker regarded the prevention of interracial marriage and schooling as the heart of his efforts to preserve racial purity, he used birth records to help segregate other civil and state institutions: cemeteries, hospitals, and public welfare agencies. Many such institutions, while they might avow a policy of segregation, did not always use the same kind of formal identification requirements as schools and marriage-licensing county clerks.Footnote 77 In addition to preventing the kind of racial mixing and familiarity that might, like common schooling, lead to “attachments,” preventing “mixed negro” families from entering white cemeteries and hospitals ensured that such families would not be able to establish a local racial reputation as white in defiance of the documentary record. Plecker worried that this sort of passing was how the contemporary documentary record could be made to lie even when the old records told a different story.

Besides denying Black and Native Virginians the ability to marry, attend schools, and enter other institutions of their choosing, Plecker's use of birth registration to police racial lines imposed a Black/white binary on a complex history of intermarriage and kinship between descendants of Africans, Native Americans, and whites from the colonial era forward. The end result was the erasure of many of Virginia's Native inhabitants who had to fight against the documentary record in order to receive state and federal tribal recognition. That fight began as soon as did Plecker's efforts to enforce the RIA, when leaders of the Mattaponi and Pamunkey publicly rebuked their classification as “negroid” by the BVS.Footnote 78 Over the next several decades, Native Virginians collected evidence both of their racial reputation as “Indian” and the documents that had registered their children as such before the RIA.Footnote 79 And, in a campaign that stretched into the twenty-first century, they also amassed evidence of Plecker's efforts to remove them from the documentary record in order to convince the state of Virginia and the federal government to recognize the Pamunkey, Chickahominy, Easter Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Nansemond, and Monacan as sovereign nations.Footnote 80

While historians already know the stories of both Jim Crow segregation and the allotment of Native American lands, the role of state-issued vital registration documents in administering these policies remains under-analyzed. Birth certificates were not simply instruments ready at hand to assist policy makers in achieving their goals. Indeed, at the time that law makers sought to destroy tribal properties and enforce segregation, most states in the union did not have functioning systems of birth registration. These projects operated alongside federal and state campaigns to achieve full birth registration, and they shared the same epistemological and ideological impulse. Documentation was not only a means to an end but also an end in itself. For the proponents of vital registration, a state's ability to register and know its population meant the mark of civilization, a step on the path from darkness to light, ignorance to knowingness. As Maryland's State Registrar put the matter in 1908, “In civilized countries the birth certificate is the basis for school attendance, voting, marriage, acquisition of property, and practically all factors concerned in civil rights, liabilities and privileges.”Footnote 81 In state administration, vital registration marked the triumph of order and rationality over the personalism that marked earlier methods of knowing people and distributing goods. Like the project of vital registration, both allotment and segregation shared an ideological commitment to order and an epistemological commitment to the superiority of state-produced knowledge over that of local, testimonial understandings of identity. In the end, the state not only made the policies that distributed rights and privileges unevenly, but it also decided who belonged in the categories to which such goods could be given.

Documentary forms of knowledge have never been total or complete in the United States but have always existed alongside other ways of fixing who people are. Nevertheless, the power of documents was clear to the men and women who lined up to be registered by the Dawes Commission, it was clear to those who refused to do so, and it was clear to those who protested Walter Plecker's designation of their race as “colored.” Eventually the documents themselves, and not just the policies they helped administer, became the targets of protest. African Americans from the middle of the twentieth century forward made it abundantly clear that, no matter what state they were born or resided in, they understood the role that birth certificates played not only in administering discriminatory policies, but also in enabling discrimination even under racially neutral policies. This is why, during World War II and the March on Washington Movement, state-level Fair Employment Commissions began to forbid employers from requiring that job seekers submit a birth certificate along with their application. Employers used the inability to produce a birth certificate (much more likely for any nonwhite American) or the certificate's racial revelations to screen applications.Footnote 82 And this is why in the 1950s, some Black doctors acted as conscientious objectors to racial classification by refusing to fill out the “race” box on the birth certificates they signed.Footnote 83 They were supported in their actions by the association for Black physicians, the National Medical Association.Footnote 84 And this is why, beginning in 1952, the NAACP's National Medical Committee also began to urge the removal of racial classification on birth certificates; local branches also put pressure on municipal health departments to drop racial identification from their certificates.Footnote 85

In 1968, the U.S. government began to issue a Standard Certificate of Birth without a box for race on the face of the certificate. Racial classifications were still made, but the information was moved to a confidential “health and medical” section of the certificate that was detached from identification (Figure 7). States were not required to adopt the Standard Certificate, and for many decades, some states refused to do so. The end of racial classification through birth registration obviously did not usher in a color-blind world. Vital documents made race not only on paper, but also in the material world, to lasting effect.

Figure 7. The U.S. Standard Certificate of Live Birth. Note that the “race” of the child's mother and father have been moved to the section that includes only “confidential information for medical and health use only.” Source: Robert D. Grover, The 1968 Revision of the Standard Certificates (Washington, DC, 1968).