In the past, we have sometimes played – and I use this provocative phrase deliberately – at ‘cheering on’ the struggles for liberation taking place in far-off lands. Now the contradiction is affecting us, becoming entwined with the already serious contradictions in our supposed wellbeing. And it turns out that what we thought was our niche is actually a cave full of monsters … we discover that the problem is still here, at the heart of the empire.Footnote 1

Enzo Mazzi (Reference Mazzi1990)

Introduction

In the early 1990s, the Italian Republic suffered a crisis that had a profound effect on antifascism (Luzzatto Reference Luzzatto2004). The disappearance of the parties that wrote the country’s constitution and the emergence of post-constitutional parties like the Northern League, Forza Italia, National Alliance and – later – the Five Star Movement, weakened the inherent link between antifascism and Italy’s political sphere. The dissolution of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) had a particularly strong bearing – impossible to calculate precisely – on the weakening of antifascism in both local and national institutions. The PCI’s legitimacy in the postwar years was grounded in its fight against the Fascist regime, making it one of the strongest conveyors of this memory. In the decades that followed, while formally the Italian constitution retained its antifascist foundations, this anchor point – symbolic yet with myriad tangible effects – was dismantled more and more broadly (Bernardi Reference Bernardi2019). The victory of a party (Brothers of Italy) with direct links to the history of Italian neofascism in the 2022 elections and Giorgia Meloni’s appointment as prime minister in October that same year was both a result of that crisis and a driver of it. On the one hand, it reflected the loss of the antifascist tradition that had already occurred. And on the other hand, as soon as the new government took office, it set to work methodically demolishing any remaining traces of antifascism, paving the way for a change to the constitution and the creation of a new republic with alternative foundations.

However, between the Second World War and the early 1990s, antifascism was more than simply a set of rules, a form of public rhetoric and the inspiration for the Italian state’s basic laws. It was also a project that sought – in a positive sense – to loosen the shackles of democracy, which as the generations passed took the form of new social groups, responding to emerging political issues and periodically redefining its meaning (Rapini Reference Rapini2005). We can therefore call it a generative tradition, rooted in Italian society. Viewed from this perspective, this article ponders whether, if one observes Italian society – as opposed to its political parties or institutions – from the 1990s to the present day, one can find traces of antifascism being very much alive, and having taken on another new meaning. Given the vast scale and unexplored nature of this subject, in the following pages we will limit our observations to a few experiences (an association and its magazine, a movement, an exhibition and a unique protest), before suggesting some hypotheses to test in future research.

Senzaconfine

A series of closely interconnected problems arose in late-1980s Italy that the governing parties found themselves unable to tackle. The presence of foreign residents had long since moved from something unusual and temporary to a permanent state of affairs, reflecting Italy’s transition from a country of emigration to one of immigration like France, Germany and the UK (Colucci Reference Colucci2018). The working conditions this low-cost workforce experienced in the agricultural, industrial and care industries were often terrible (Gambino Reference Gambino1989). Racism – a poisonous and extremely deep-rooted phenomenon that had never disappeared in Italy – seized on the figure of the vu cumprà and marocchino – to use the typical public parlance of the day (Cuffaro Reference Cuffaro1989a) – as the latest subject to racialise (Fracassi Reference Fracassi1989). Alongside racism, a new wave of neofascism also emerged that strayed into emulating the illegal actions of the Nazi groups that had sprung up in Germany during its reunification (Cipriani and Giardoni Reference Cipriani and Gaiardoni1989; Uesseler Reference Uesseler1989; Walraff Reference Walraff1989). It was already patently clear that legislation on immigration and on citizenship more generally was required (Mosca Reference Mosca1989; Cuffaro Reference Cuffaro1989b). A few small amendments aside, the law in force at the time dated back to 1912, based on the principle of jus sanguinis and introduced to maintain emigrants’ connection to Italy (Bussotti Reference Bussotti2002).

In summer 1989, a tragic event occurred that triggered a series of demonstrations and ultimately led to a national antiracism movement. The unusual breadth of the protests, their impact on society and the qualitative leap in the reflections on the country’s various problems signalled the end of a period where the only associations tackling racism were the more traditional Catholic and trade union organisations (Rebughini Reference Rebughini2000; Della Porta Reference Della Porta1999). Those involved in this new phase now felt part of a collective group or movement, based on a new set of premises (Senzaconfine 1990a; Naletto and Trillini Reference Naletto and Trillini1996).

Jerry Essan Masslo, a citizen of the racist Republic of South Africa, requested asylum upon arrival in Italy in March 1988. Although it should have been guaranteed by the Italian constitution, his application was rejected. Armed solely with a temporary permit, he only managed to land insecure and underpaid jobs, and ended up receiving support from the Community of Sant’Egidio in Rome. He decried his experience of racism from Italians in an interview with Massimo Ghirelli on the television channel Rai 2:

I don’t want to see the things I experienced in South Africa here in Italy. They are really happening here in Italy. No Black person, no African forgets what racism is, and I have experienced it here: it is unacceptable. I have seen things that should not be happening here in Italy with my own eyes. No Black person, no African can put up with this situation, nor understand racism (Masslo Reference Masslo1989).

Jerry Masslo was killed in a raid during the night of 23–24 August at Villa Literno, where he had gone to work as a tomato picker. The reaction to his death was a watershed moment (Colucci Reference Colucci2022). Just over a month later, labourers – almost all immigrants, supported by various associations and trade unions – managed to organise a strike that blocked illegal hiring for a day (Colucci and Mangano Reference Colucci and Mangano2019). This was followed on 7 October by a large antiracism demonstration, attended by around 200,000 people. One of its organisers was Abba Danna, president of Coordinamento Immigrati Sud del Mondo, an organisation founded at the start of that year, and a member of the Associazione Ricreativa Culturale Italiana (ARCI) (Danna Reference Danna1989). The number of organisations who signed up to take part rose quickly, eventually reaching 500. As well as expressing people’s personal anger, the event provided a political platform that demanded civil and political rights for immigrants, recalling the ‘strong roots of democracy and solidarity in Italy’. It also established a national convention for the end of the year, which sought to create a permanent structure for the Italian antiracism movement and to draft a bill of rights.

Although the convention was a success, the structure failed to materialise and the bill of rights did not achieve full consensus. Divided into 15 articles, it included the right to asylum – denied to Jerry Masslo – regardless of place of origin; jus soli (the granting of citizenship at birth); the recognition of dual citizenship; the right to vote in local, national and European elections after two years of living on Italian soil; equal rights for anyone resident in Italy regarding access to work, healthcare, education and accommodation; and the introduction of a law prohibiting ‘any promotion of national, ethnic or religious hatred’ (Senzaconfine 1990b).

Antifascism was merely a background element that stimulated the political culture of the socialist and communist, secular and Catholic organisations involved, as also shown by the references to many articles of the constitution. However, some of the groups perceived the link between that political tradition and antiracism more clearly than others, considering it a key battleground for expanding democracy in this new historical period. This was certainly the case for the association Senzaconfine, a ‘multicoloured meeting place’ founded around this time in Rome to promote ‘effective assimilation of all minorities […] and to build a society that is not grounded in competition, profit and exploitation’.Footnote 2

Senzaconfine’s operations were based on voluntary work by a mixed group of Italians and foreigners. Its president was Eugenio Melandri (1948–2019), a missionary who, ‘bringing together his faith and a passion for society and politics’, worked to rid the world of poverty and injustice and to promote peace (Zanotelli Reference Zanotelli2019; Un ponte per… 2019). Dino Frisullo (1952–2003) was the group’s secretary.Footnote 3 A passionate supporter of the liberation movements of countries in the Global South and of their right to self-determination – particularly the Palestinians and Kurds (Frisullo Reference Frisullo and Aziz2000) – Frisullo was a tireless organiser, a builder of relationships and a man of action. He soon became the leading figure in immigrants’ nascent self-organisation in Rome (Senzaconfine 2023).

Between 1989 and 1994, the association published a magazine of the same nameFootnote 4 that framed racism and antiracism within wider criticism of the Western development model and its cultural forms.Footnote 5

In an editorial marking the launch of a new monthly series (Figure 1), which corresponded with the 500th anniversary of the discovery of America, Melandri tackled the topic of colonialism as a ‘symbolic order’ (Melandri Reference Melandri1991). The perception of White, Christian Europe as a superior civilisation, so clearly evident throughout colonial history, had triggered – in his view – a long chain of events from the slave trade through to the contemporary racist and xenophobic uprisings. Citing Frantz Fanon and Jean-Paul Sartre, Melandri hoped that Europeans would decolonise themselves by undergoing ‘a painful operation’ to eradicate ‘the colonist found in each and every one of us’, and especially the untouchable one found in ‘government cabinets’ (Melandri Reference Melandri1992). This sensitivity ensured the magazine immediately grasped the political scope of Mexican neozapatismo and its potential to act as the spark for the first protests against globalisation in Europe (Melandri Reference Melandri1994; Senzaconfine 1994). It published articles on these topics that predated the New Global movements that sprung up at the end of the decade (Andretta et al. Reference Andretta, della Porta, Mosca and Reiter2002).

Figure 1. Senzaconfine, no. 1, 1991. Source: Archivio del Museo Storico di Trento, photographed by the author.

The Mancino law, enacted on 25 June 1993, provided a litmus test for the rise in neofascist violence in the early 1990s. The law sought to put a stop to the spread of neofascist groups and their propaganda, and to halt the frequent racist attacks. Senzaconfine monitored all these aspects continuously (Nicotra Reference Nicotra1992; Manzi Reference Manzi1992; Frisullo Reference Frisullo1993), enabling Dino Frisullo to explicitly describe the issue of the clash between antifascism and antiracism as being on the agenda of both the magazine and the antiracism movement as a whole. Far from taking a placatory position, this article highlighted the existing fault lines in the antifascist arena. Frisullo identified, on one side, ‘generic’, ‘ritual’ and ‘celebratory’ antifascism, which was very sensitive to antisemitism and considered the memory of the Holocaust to be an integral part of its own historical memory. In Italy, the memory of the extermination of the Jews and the racial laws was for many years contained within the antifascist memory, before it took on its own independent significance in the 1980s (Focardi Reference Focardi, Berti, Focardi and Sondel-Cedarmas2018). According to Frisullo, however, this group, while always showing solidarity with the Roman Jewish community whenever it was subjected to threats or slights, was less well equipped to decode other forms of racism, particularly when it was directed towards immigrants and Muslims.

On the other side, there was the antifascism promoted by younger people. Often closely linked to associations and social centres working with immigrants, they had lost trust both in ‘generic’ antifascism and in the Roman Jewish community which – often resorting to ‘Holocaust theology’ – blindly supported the State of Israel without acknowledging the colonial dimension of the occupation or the Palestinians’ rights. These two components, Frisullo continued, expressed and combined antifascism and antiracism differently, and sometimes did not understand one another, on occasions even finding themselves in conflict and on opposing sides.

Pacifist and non-violent antifascism and antiracism made up a third and final group, and this segment had a prominent role within Senzaconfine. Frisullo argued that these fault lines needed to be overcome by drawing on people’s memories of suffering, marginality and exploitation, which could counter the proliferation of ‘community, ethnic or religious identities’ and instead provide a platform for assembling a new universalist antifascism and antiracism, based on mutual acceptance. For Frisullo, however, this was not an abstract, purely moral or moralising acceptance, but rather one embodied ‘in terms of solidarity among the oppressed’ and ‘against common enemies’ (Frisullo Reference Frisullo1992).

With this in mind, Senzaconfine was one of the founders in 1994 of the Rete nazionale antirazzista (National Antiracism Network), one of the rare examples of the Italian antiracism movement coming together on a national scale. Frisullo was one of its spokespeople, alongside anthropologist Annamaria Rivera and Udo Enwereuzor (later replaced by Andrea Mormiroli). The network – which was active until 1997 – brought together 140 grassroots groups and various associations, including, at the beginning, the Italian General Confederation of Labour (CGIL) and ARCI. Senzaconfine’s work and viewpoint were embedded in its operations, as shown by the subjects of the three citizens’ initiative bills the network prepared, although they never went to a vote: the transfer of responsibility for residency from the police to local bodies; the granting of the right to vote to all foreign citizens who have lived in Italy for at least five years; and the reform of the legal system regarding Italian citizenship, altering the newly established 1992 law, which felt outdated as soon as it was introduced (Rivera Reference Rivera2023). The debates held during the law’s development and its content showed that, across the board, political elites were more interested in cajoling Italians who had moved abroad than finding a positive way to govern the reality of immigration, which was already clearly a structural phenomenon. Both the work of the associations and the first forms of migrant engagement and active citizenship were therefore ignored (Morozzo della Rocca Reference Morozzo della Rocca, Asquer, Bernardi and Fumian2014).

From Pantera to ‘race’

At the same time as the antiracism movement was emerging, another movement was finding its own language and ways of bringing together antifascism and antiracism: Pantera. The name was derived both from a news item and from the history of protest movements. A panther was apparently spotted in the Lazio countryside in that period, and this proud, wild animal, on the run from a circus, provided an irresistible symbol with which to identify for the young university students who opposed the reforms being introduced by the minister Antonio Ruberti, and who wanted to avoid being ‘captured’. The panther was also, however, the symbol of one of the most radical African American parties (Figure 2): the Black Panther Party (BPP). Despite the clear difference between historical fascism and the liberal-democratic political system of 1960s USA, the BPP maintained that the difference was much less marked for African Americans, who were racialised, discriminated against and still segregated in certain urban areas and social settings, making both the fight against fascism and racism and the push to transform capitalism relevant in a contemporary context (Cleaver Reference Cleaver, Mullen and Vials2020; Black Panther Party Reference Party, Mullen and Vials2020).

Figure 2. Symbol of the Black Panther Party, adopted as a logo by the Pantera movement. Source: Leggo, 20 January 2020.

The Italian ‘panthers’ – albeit with differences between the various groups – drew on this imagery and on Italian political tradition, and reformulated both within the new national and international context (Palombi and Ferri Reference Palombi and Ferri2020; Cominu and Perrone Reference Cominu and Perrone2023). During a historical period when racism and neo-Nazism were re-emerging rapidly in reaction to increasing immigration levels, the movement – which described itself as antifascist – shifted antiracism closer to a reflection on the constitution and citizenship:

[T]he right to study is one of the rights connected to being a member of society, a right that comes with citizenship, like the right to work, to a home and to be healthy. It comprises the right to knowledge, or rather to access the places where knowledge is processed, and this means asking a huge question about democracy. And democracy means considering a culture full of differences and seeing it in a different light: as something enriching and stimulating for all; in other words, fighting to ensure that the tools of knowledge and the places knowledge is produced, socialised and accessed are the legacy of all the differences expressed in our social and cultural context, including those that until now have remained at the margins and which therefore must be able to play an active role. Education based on accepting others’ differences is enriched by diversity and affirms the positive value of different views of the world, standing on the front line in the fight against marginalisation and racism. (Il graffio della pantera 1990a)

This statement of principle was followed by initiatives in places like Milan, Florence, Rome and Bologna in support of and in solidarity with immigrants and to campaign for their rights (Falciola Reference Falciola2020). One of the moments where the bond between antifascism and antiracism was strongest was the full week of protests Pantera organised in Rome for Liberation Day, culminating on 25 April 1990 with their attendance at the rally held by the United Asian Workers Association, a group representing people with extremely precarious working conditions. A document produced by the movement explained the bond in these terms: ‘the partisans who fought against Fascism also fought against that regime’s antisemitism. It is no stretch to connect the partisan struggle of 45 years ago with the antiracist battle of the present day’ (Il graffio della pantera 1990b).

When the Pantera movement broke up, having largely merged with the pacifist movement against the war in Iraq, a small number of students from the groups that had formed in the faculties of literature and education at the University of Bologna tried to find a way to continue their intellectual and antifascist political engagement. Giuliana Benvenuti, Riccardo Bonavita, Gianluca Gabrielli and Rossella Ropa decided to organise an exhibition on racism under Fascism, together with Mauro Raspanti from the Centro ‘Furio Jesi’,Footnote 6 an institution founded in the late 1980s to study right-wing culture and its past and present ramifications, particularly in relation to Julius Evola’s ‘spiritual racism’. The link to left-wing historian and writer Furio Jesi (1941–80) (Manera Reference Manera2012) leaves no doubt as to this group’s political leanings. Its members were not only of the same generation, they also shared a desire to fight the political climate of the time and to eradicate – once and for all – the deeply rooted and diverse racism that persisted in the country. A preparatory document for the exhibition, later repeated to a large extent in the introduction to the catalogue, noted:

[F]ollowing the numerous generic and abstract discussions on racism, which have produced full-blown rhetoric on the moralising and ineffective nature of antiracism, we have decided to ascertain in historical terms what Fascist racism actually was, and what impact it had on Italian society at the time. … A specific topic, therefore, … which also helps us to understand the specific forms that racial discrimination takes today, both through the things that have remained the same and the profound differences and changes that have occurred.Footnote 7

Underpinning everything, however, was a common identification with the antifascist tradition; indeed, they considered the exhibition a way to continue that tradition in the new political era. This goal comes across very strongly in the exhibition’s preparatory documents.Footnote 8 A striking example is the choice of a poem by Franco Fortini – Complicità – to conclude a file summarising the project:

Written in 1955, the poem invited readers to imagine the Resistance as a permanent commitment, and to fight any concessions, or – as the title puts it – complicity. As Gianluca Gabrielli noted recently, Fortini was one of the authors who spent time with the Pantera group. Indeed, in late 1989, he and classicist and historian Luciano Canfora were invited to the university for a conference on historical revisionism (Gabrielli Reference Gabrielli2024). But Fortini was also Riccardo Bonavita’s favourite author, to whom he would dedicate his entire doctoral thesis a few years later (Bonavita Reference Bonavita and Mazzucco2017). Bonavita was certainly one of the people who identified most strongly with antifascism and felt an urgent need for contemporary political engagement (Benvenuti Reference Benvenuti2024). Opting for Fortini’s poem established the group’s position within a precise and instantly recognisable historical legacy – a smart decision that meant there was no need to use the word ‘antifascism’, because antifascism provided the (upstream) condition of possibility for the choice itself.

The exhibition – soon named La menzogna della razza (The Lie of Race) – was held in the Archginnasio Municipal Library in Bologna from 27 October to 10 December 1994, and featured approximately 300 items from around 50 different archives and libraries.Footnote 9 The event was made possible by the support of Nazareno Pisauri (1940–2016), director of the Emilia-Romagna region’s Institute for Artistic, Cultural and Natural Heritage (IBACN), who managed to raise over 150 million lire, enough to cover all the costs of the exhibition, related activities and catalogue (Centro Furio Jesi Reference Jesi1994), and worked hard himself to spread the word across Italy.Footnote 10

Figure 3. Exhibition catalogue for La Menzogna della Razza. Graphic design by Andrea Rauch. Source: Personal Archive of Andrea Rapini.

Pisauri, who belonged to the same generation as Melandri and Frisullo, and, like the latter, had experience in the New Left (Bazzocchi Reference Bazzocchi2016; Campioni Reference Campioni2016), fell in love with the project, which matched his civil and political leanings. The people to whom he assigned practical and organisational tasks were all of the same political persuasion, and so became personally involved in the project and went far beyond their assigned tasks. Giovanni Serpe, who was the director of the region’s historical archives at the time, played a particularly noteworthy role. In a draft article for the magazine IBC, which described and promoted the activities of the IBACN, he wrote:

[N]owadays, in 1994, where it turns out that there is no such thing as fascism, but rather many fascisms, historically determined, with original forms, the only thing we know about these days is that they will end in a fascism, isolated yet crystal-clear signals of which are already visible, which we will later recall and recount how we lived through them .Footnote 11

The exhibition was divided into three sections. The first – Pregiudizio e propaganda (Prejudice and Propaganda) – featured a display of humorous journals, comics, colonial postcards and popular novels. The second – L’ideologia (Ideology) – analysed the various categories of racism: biological racism, national racism, esoteric-traditionalist racism, Catholic anti-Judaism and fascist antisemitism. And the third tackled Prassi persecutoria (Persecution in Practice), both in colonial settings and within Italy itself. The exhibition’s underlying interpretative approach and method were crystal clear: racism was a single phenomenon, divided up into different stereotypes and devices, but which all treated certain groups of people (Africans, homosexuals, Jews or ‘gypsies’) as inferior. Although denied by a certain proportion of historians (De Felice Reference De Felice1993) and by Italians’ own self-representation, racism was not imported from Nazi Germany following the laws of 1938: Italy had its own deep-rooted tradition too, and the authors saw its worrying persistence over time.

Considering La menzogna della razza as nothing more than a local cultural event would be a mistake: its reception and the way it travelled around Italy gave it both political and social importance. Before it even opened, an article by Giorgio Fabre previewing various documents showing that Mussolini wanted to take the internment of Jews up a level even before the time of the Italian Social Republic (Fabre Reference Fabre1994) led to an active discussion in the press involving a vast range of titles: Panorama, la Repubblica, la Stampa, l’Unità, l’Avvenire, il Popolo, l’Unione sarda, il Resto del carlino, il Messaggero, il manifesto and il sole 24 ore. Renzo De Felice – undoubtedly one of the organising group’s leading polemicists – also weighed in. And Rai 3, Rete 7 and Telecentro-Telesanterno all sent teams to film news reports.

The event’s reach and its visitor numbers for the Bologna dates led the organisers – in agreement with the IBACN – to create an abridged version to tour around the whole of Italy. The exhibition had always been designed specifically to have an impact on mass culture, rather than targeting solely ‘high culture’ or a small group of specialists. The Laboratorio Nazionale per la Didattica della Storia (National History Education Laboratory) was involved alongside the Istituto storico della Resistenza dell’Emilia-Romagna (Emilia-Romagna Historical Institute of the Resistance). Three secondary school teachers – Nadia Baiesi, Alessandra Deoriti and Anna Grattarola – devised some potential teaching programmes that accompanied the exhibition in many cities, and so resurrected the idea of working with schools and the general public.Footnote 12 Between 1995 and 2003, schools, associations and municipalities in an impressive 30 different cities asked to host the exhibition.Footnote 13 Eleven years after its launch, Riccardo Bonavita, Gianluca Gabrielli and Rossella Ropa curated a new version of the exhibition entitled L’offesa della razza (The Insult of Race). Held once again in Bologna, in the Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio, from 27 January to 26 February 2005, the exhibition took on a fresh lease of life, and continued to spread antiracist sentiments, reworked to suit the new global context, until 2013 (Bonavita, Gabrielli and Ropa 2005).Footnote 14

‘Comincia con F ma non è follia’

While the two versions of the exhibition were travelling around the country, and Italy was becoming increasingly harsh and splintered as a result of the tensions caused by globalisation (Crainz Reference Crainz2016, 294–366), the redefinition of antifascism and its connection to antiracism followed a meandering and as yet unexplored path.

Take, for example, the series of protests that came to a head in Genoa in 2001. While antifascism was certainly not centre stage at these events, the young people who took part in the social forums held before, during and after those dramatic days (19–21 July) would certainly not have accepted being defined as not antifascist, afascist or even anti-antifascist. They joined – without fanfare – the internationalist and anticolonial tradition of antifascism, which acted almost like a type of amniotic fluid. Despite the young people’s attempts to differentiate themselves from previous generations and from the rhetorical use of antifascism (Wu Ming Reference Ming and Lorenzis2003), the new organisational forms developed within this tradition, as seen in the influence of the CLN (the National Liberation Committee) on the social forums themselves. The main content underpinning the protests also came from this tradition: nation states’ failure to properly tackle the brutality of globalisation and its neocolonial function; criticism of the financial elites and demands for more democratic decision-making processes; environmental catastrophe; the impoverishment of the most destitute parts of the world; the right to asylum; and a redefinition of citizenship on a supranational scale. Antiracism was another key topic motivating the protestors; indeed, the first large demonstration (held on 19 July) was dedicated to migrant rights and fighting racism. This topic was particularly potent for the movement’s Italian contingent, since immigration had been one of the most fiercely debated topics in the recently concluded election campaign (Marini Reference Marini2002), and the new Berlusconi government (his second term in office) was preparing to deliver the ‘Bossi-Fini law’, which sought to reduce foreigners’ opportunities for accessing the country. Essentially, antifascism was an implicit assumption that did not need to be spelled out. However, it was ready to react, to speak out and drive engagement in the situations where democracy seemed most at risk: when slogans praising Pinochet and Mussolini or mobile ringtones of the Fascist hymn Faccetta nera were heard at the barracks in Bolzaneto (Sammartano Reference Sammartano, Dei and Di Pasquale2013); when faced with the ‘butchery’ at the Diaz Pertini school in Genoa (Fournier Reference Fournier2007); or in the protests in various cities against the persistent threat of neofascism, from CasaPound to Forza Nuova (Becucci Reference Becucci2003). The memories of the people involved and the oral history collections released in the years that followed (Bracaglia and Denegri Reference Bracaglia and Denegri2020; Bracaglia, Salvatori and Tiburzio Reference Bracaglia, Salvatori and Tiburzio2021; Monteventi Reference Monteventi2021; Proglio Reference Proglio2021) can all be read from this perspective.

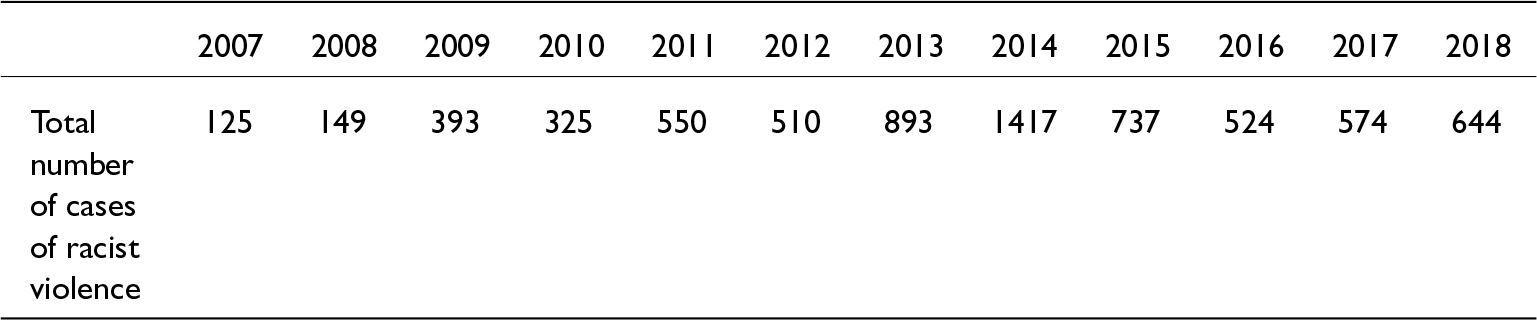

The alter-globalisation movement in Genoa had identified a menace that was destined to continue to grow relentlessly: the criminalisation of immigrants and increasingly frequent cases of racism. The constant rise in the number of foreign nationals in Italy in the previous decade and the public visibility of refugees following various humanitarian crises (in Tunisia, Libya and Syria) were used in the media and by right-wing parties – and in certain cases on the left too – to turn immigration from a social and political problem, which could be managed using standard tools and medium-term planning, into a perpetual ‘emergency’ and security issue (Miraglia and Naletto Reference Miraglia, Naletto, Giovannetti and Zorzella2020; Colucci Reference Colucci2018, 133–187). It was no coincidence that the interior minister, Roberto Maroni of the Northern League, chose the name pacchetto sicurezza (security package) for the next large-scale legislation on the subject, launched in 2008, while the financial crisis, which exploded that same year, had a serious impact on the living and working conditions of immigrants and the working classes. These changes went hand in hand with an increase in episodes of racism, which, in those years, primarily involved violence against migrants (Lunaria 2020, 6). On 14 September 2008, a 19-year-old boy called Abdoul Guiebre, known to everyone as Abba, was killed by the owners of a coffee shop in Milan after he stole a packet of biscuits. They shouted ‘sporco negro’ (dirty nigger)Footnote 15 at him, then beat him up. On 18 September, six workers from Ghana (Kwame Julius Francis, Affun Yeboa Eric, Christopher Adams, El Hadji Ababa, Samuel Kwako and Jeemes Alex), with no links to organised crime, were slaughtered in Castel Volturno by a group of hitmen from the Camorra’s Casalesi clan. Racism was given as an aggravating factor in the killers’ guilty verdict. In 2010 in Rosarno, a village in the province of Reggio Calabria, where fruit-picking was entrusted to an exploited immigrant workforce that endured incredibly tough living conditions, immigrants were attacked several times and subjected to various punitive expeditions, with kneecappings and air rifle shots fired. Riots then broke out, which received a great deal of public attention. In 2011, the neofascist Gianluca Casseri killed two Senegalese immigrants – Diop Mour and Samb Modou – in Florence with a 357 Magnum, injuring a third, Sougou Mor. In July 2016, Amedeo Mancini, who also had close ties to fascist groups, killed Nigerian refugee Emmanuel Chidi Nanmdi in Fermo with a punch, after Nanmdi had tried to defend his partner whom the Italian had called an ‘African monkey’. These are just the most serious cases; merely the tip of the iceberg. The true extent of the phenomenon is revealed in data collected by the association Lunaria, which began collating episodes of racist violence (verbal and physical attacks, damage to property or possessions, and discrimination) in 2007, the year they really started to escalate.

(Source: Lunaria 2020, 75)

Something unusual occurred in 2018. Compared to the picture we have just painted, the new element was not the racist violence that unfolded, nor its fascist origin, but rather the perhaps unprecedented joint mobilisation of antifascism and antiracism. On 31 January that year, 18-year-old Pamela Mastropietro was killed not far from Macerata, a city in the Marche region in the east of Italy. The investigators’ inquiries into her death immediately focused on Innocent Oseghale, a Senegalese immigrant with previous drug-related convictions.Footnote 16 Three days later, Luca Traini, a young man from a nearby village, decided to ‘avenge’ the killing and ‘get justice by killing Blacks’ (Tonacci Reference Tonacci2018).Footnote 17 On arriving in Macerata, he began to shoot randomly at people with black skin, injuring six.Footnote 18 Traini was not an unknown entity. He had run for the Northern League in the local elections in Corridonia in 2017, and attended the meetings of the neofascist groups CasaPound and Forza Nuova. He had a Wolfsangel tattoo on his right temple – a Germanic rune used first by the Nazis and then in the late 1970s by the Italian neofascist movement Terza Posizione. The police found a Celtic Cross flag and a copy of Mein Kampf at his home. After the attempted massacre, he gave himself up in front of the war memorial erected by the Fascist regime in 1932 in Piazza della Vittoria, wrapped in an Italian flag and with his arm outstretched in a ‘Roman salute’.

After the attack, Sisma, an independently managed social centre in Macerata, organised a rally entitled ‘Antifascista e antirazzista’ (Antifascist and antiracist), which gathered support from across Italy with a document titled Inizia per F ma non è follia (It begins with F, but it is not ‘folly’).Footnote 19 The document did not evoke the fascistisation of society in any way, nor the spectre of a past regime. On the one hand, it denounced the lack of recognition by the media and political parties of Luca Traini’s ‘fascist mould’, which had presented him instead as a madman (Rapini Reference Rapini and Vecchio2025). And on the other hand, it noted the attack’s racist content, while also more generally pointing out the racist filter through which the topic of immigration was seen in Italy.

Ignored by the leadership of Italy’s main left-wing parties, especially the Democratic Party (PD),Footnote 20 and mocked by those on the right, who claimed that the real issue was the ‘invasion’ of ‘illegal immigrants’ (Maneri and Quassoli Reference Maneri and Quassoli2020), the rally was held on 10 February and was accompanied by various forms of online mobilisation, both before and afterwards (Pavan and Rapini Reference Pavan and Rapini2022). People of all generations processed through the streets of Macerata, but most importantly it was attended by immigrants, and especially Africans, for whom fascism also evoked the colonial past, and not just a contemporary problem with racism (Camilli Reference Camilli2018). The demonstrators felt abandoned by the political parties’ stance on antifascism and their inability to explicitly condemn the fascist and colonial past’s continued existence. While there were plenty of purely identity-driven and nostalgic phrases and slogans based around the pairing of fascism and antifascism, the mobilisation also showed clear traces of an original redefinition of antifascism, mixed with antiracism and postcolonialism. Straddling past and present, the Resistance was also shown in a different light. As a way of fighting racism, various sectors of the protest began to reflect in historical and political terms on the role many Africans played in the fight for Italian and European liberation.Footnote 21 Seen from this perspective, the antifascist resistance to Nazism and Fascism was also presented as an anticolonial war. Two main reasons were given for this: firstly, because the armed partisans included many men from the Italian colonies; and secondly, because Hitler and Mussolini literally intended to turn the whole of Europe into a colony, using the same methods that until that point had only been applied in the territories ruled by the western empires.

Conclusion

In this article, we asked whether, despite the breadth and depth of the crisis currently facing antifascism, traces of a change in the meaning of that tradition can nevertheless be seen beneath the surface of the most visible examples in the spotlight of public, political and institutional discourse. By shifting our gaze to the social sphere, we have discovered that antifascist culture provided the basis for the complex antiracism movement that appeared in the early 1990s, and its subsequent forms.

The case studies we have investigated also highlight the existence of various generational segments, which, set in different contexts and political climates, gave a particular meaning to the meeting of antiracism and antifascism. Firstly, Eugenio Melandri and Dino Frisullo exemplified two radical 1970s political cultures: the former heretical and missionary Catholicism, and the latter the critical Marxism of the New Left. There was a strong link here with anti-imperialism and the struggles of the national Liberation movements, which evoked the Italian Resistance (Brazzoduro Reference Brazzoduro2020; Russo Reference Russo2020). Their commitment to antifascism helped to reposition antiracism, changing it from a purely moral and/or educational issue to one connected with incorporating the symbolic order of the colonial legacy and the role of racism in the reproduction of the social order. Nazareno Pisauri shared the same references.

The youths in Pantera comprised another generational segment. For Giuliana Benvenuti, Riccardo Bonavita and Gianluca Gabrielli, antifascism was – among other things – a vector for a genealogy of racism. They grasped on the one hand the political urgency of fighting the revisionist wave, the success of Silvio Berlusconi and his party, which stemmed from the Italian Social Movement’s transition to postfacism; and on the other hand, more positively, the need to recognise the deep roots of persistent forms of discrimination, seeking to create the conditions for a multicultural and future-oriented society. The event La menzogna della razza – an era-defining moment for Italians’ self-representation – was imbued with these goals and moods.

The final generational segment consisted of the activists at the protests triggered by the attempted racist massacre in Macerata. Here, it is trickier to isolate detailed generational data, since some people attended multiple events. Many of them were probably in Genoa in 2001, like the Wu Ming collective, which was responsible for some of the most retweeted tweets in January 2018 (Pavan and Rapini Reference Pavan and Rapini2022). They were joined – and surrounded – by younger activists too. Antifascism, which was explicitly evoked and referenced, had to compete with a variety of topics, including the persistence of neofascism and colonial arrangements, the use of women’s bodies and the depiction of the avenging man, the demonisation and animalisation of immigrants, the depoliticisation of fascist violence in public and political discourse and, finally, the reinterpretation of the Resistance from a postcolonial perspective. Those involved included – very significantly – immigrants and the children of naturalised immigrants or those waiting to acquire Italian citizenship: the appropriation of antifascism by these segments has yet to be investigated.

The examples we have looked at were not, of course, the only ones in the period under examination. It is also likely that the meaning of antifascism also followed other new paths, which need to be explored in addition to the new turn in antiracism, pinpointing any points of alignment. These include, to offer just two examples, the intersectional neofeminism of networks like Non una di meno or the reclaiming of the working-class narrative by the GKN factory workers’ collective in Campi Bisenzio, near Florence, and by the grassroots Working Class Literature Festival held there. Insorgiamo! (Let’s rise up!), the key word from the collective’s remarkable protest campaigns waged both in the media and on the streets, was taken directly from the Resistance (Collettivo di fabbrica GKN 2022). These examples suggest that after 1989, various sectors of the antifascist movement chose racism as a political battleground to defend democracy and expand its borders. This vision of racism was not limited to antisemitism: it was more wide-ranging and complex than ever before in Italy’s history (Patriarca Reference Patriarca2021).

When neoliberal globalisation created the perfect conditions for the development of new nationalisms, the resurgence of neofascism, and increasing claims from minorities of all types connected to their specific interests, the distinctive antifascist nature of the discourse on antiracism revealed only one feasible way forward: rejecting all forms of closed community or ethno-cultural and religious identitarianism. This is vitally important knowledge, which deserves to be valued along with the other information uncovered by the research. Antifascism’s universalist leanings, which stem from its connection with the twentieth century’s leading political cultures, helped to prevent immigrant protests – and their sometimes-desperate uprisings – becoming too tribalised, by avoiding protestors’ mobilisation being based on ethnic homogeneity.

Senzaconfine, Pantera, the Centro ‘Furio Jesi’, and the young men and women in Genoa and then Macerata all planted seeds to fight the creation and destructive use of clashes of civilisation between East and West, Europeans and ‘illegal immigrants’, gated communities and ‘indigènes/barbares’ (Bouteldja Reference Bouteldja2023), black and white, ‘normal’ and ‘deviant’, Jews and Palestinian Arabs, Christians and Muslims. They did it by returning to the generative nucleus of twentieth-century antifascism: a discussion on freedom, justice and equality in mass society in an age of nation-states. And, finally, they did it by directing antifascism towards new forms of postnational citizenship, within the new global space that was taking shape. Citizenship seen both as formal belonging to a political community – in other words the ‘right to have rights’ (Arendt Reference Arendt2009, 410) – and the full and tangible enjoyment of those rights.

Translated by Ian Mansbridge

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Andrea Rapini is a professor of contemporary history in the department of sociology and business law at the University of Bologna. He was previously a visiting researcher at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris and resident scholar at the École française in Rome. His studies have focused on the history and memory of antifascism (Antifascismo e cittadinanza. Giovani, identità e memorie nell’Italia repubblicana. Bologna: Bononia University Press, 2005), business history (The History of the Vespa: an Italian Miracle. London: Routledge, 2019) and the history of knowledge (A Social History of Administrative Science in Italy. Planning a State of Happiness from Liberalism to Fascism. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022). His recent publications include (with Pierre Weill) ‘Histoire des savoirs et relations de pouvoir. Les métamorphoses de la science administrative italienne (1875-1935)’, Annales. Histoire Sciences sociales, n. 2, 2024, 1–34.