1 Introduction

The Trianon Treaty and the Holocaust are among the most important events of Hungarian history in the twentieth century. Their significance goes beyond history, their impact is outstanding from a political, social, and sociopsychological point of view, and their influence continues to this day. There is a close connection between the social memory of Trianon and the Holocaust. However, they cannot have an equal place in national memory (É. Kovács Reference Kovács2010; Gyáni Reference Gyáni2012a, Reference Gyáni2012b, Reference Gyáni, Miller and Lipman2012c). Trianon has a “hegemonic position in Hungarian social memory” (É. Kovács Reference Kovács2016, 531), while the “public memory of the Jewish Holocaust does not play a great role in shaping present-day historical consciousness in Hungary” (Gyáni Reference Gyáni, Miller and Lipman2012c, 92). The evaluation and memorialization of Trianon and the Holocaust are still among the most divisive topics in Hungary, separating those on opposite poles of the political and ideological spectrum. This division is still present in both political and public discourses and has been reinforced by the Orbán regime’s extensive identity and memory politics.

This article analyzes this division by examining the thematic structure and the discursive framing in articles about Trianon and the Holocaust in today’s Hungarian online media. The fact that Fidesz has built a highly polarized media empire since 2010 makes this corpus suitable for grasping divisions along political lines. On the one hand, Fidesz is extensively using the media as a channel through which it continuously repeats and propagates, among other things, its messages regarding identity and memory politics. On the other hand, due to the one-sidedness of the progovernment media, the anti-government media occupy almost the only field where the messages of the opposition or standpoints confronting Fidesz may appear. In this way, online media provide a rich empirical base for sociological research and make it possible to describe the framing and interpretation of the above topics and analyze the similarities and differences of memorialization between the distinctive political sides.

Our corpus consists of 26,519 articles containing the word Trianon or Holocaust published on various online sites between September 2017 and September 2020. In our analysis, we use a mixed-method approach, combining automated text analytics with the qualitative analysis of discourses.

2 The Role of History after 1989

A radical change of regime, such as what took place in Hungary, similarly to other Eastern European countries, between 1989 and 1990 necessitated “the reformulation of collective identities and the introduction or reinvigoration of the principles of legitimising power” (Kubik and Bernhard Reference Kubik, Bernhard, Kubik and Bernhard2014, 8). Accordingly, one of the crucial tasks of the political parties that emerged after 1989 was to establish clear and distinct identities. Since their political programs were very similar, “attempts to forge an identity were made primarily on a symbolic level” (A. Kovács Reference Kovács2011, 22). In addition to self-placement on the western political spectrum, “the second method for manifesting identity was to express a relationship with certain emblematic periods, events, or individuals from Hungarian history” (A. Kovács Reference Kovács2011, 22). “The liberal opposition […] primarily referred to the democratic chapters of recent Hungarian history” (Rainer Reference Rainer and Mörner2020, 142) It is important to note that Fidesz belonged to the liberal camp at this time. The national conservative opposition reached back to the interwar period where national conservativism was said to be the mainstream ideology. However, at the same time, they had to make a sharp distinction from the dark side of the Horthy regime, the collaboration with the Germans, anti-Jewish legislation, the Holocaust, and politics leading to Arrow Cross rule. Footnote 1 In this narrative, the deeply antisemitic Horthy regime, which consistently and increasingly restricted the fundamental rights of Jews, had nothing to do with the Holocaust, which only happened because the Germans occupied Hungary on March 19, 1944. Moreover, the anti-Jewish legislation served the precise purpose of satisfying German needs and, in this way, protecting Hungarian Jews from deportation. Furthermore, the answer to the question of what led to the German orientation of the Horthy regime and the “derailing of Hungarian history” (A. Kovács Reference Kovács2011, 23–24) was the unjust Trianon Treaty.Footnote 2

As Andrea Pető argued, “After the forcible forgetting of memory policy under communism, a memory bomb exploded in 1989. Society was said to have broken out from under the red carpet, under which everything had been hidden” (Reference Pető2014, 4). After 1989, pre-World War II cleavages resurfaced (A. Kovács Reference Kovács2011, 6–11; Romsics Reference Romsics and Bíró2018). The groups separated by these cleavages belonged to different sides of the political spectrum and differed, among other things, in their relationship with the past and the events of Hungarian history. Their differences were also manifested in symbolic debates such as what should be the coat of arms and the main national holiday of the Republic of Hungary (Rainer Reference Rainer and Mörner2020, 143).

3 Factors behind the Success of Right-Wing Populist Parties

Fidesz has come a long way from the late 1980s to the present day. As mentioned, they started as part of the liberal opposition, followed from 1993 by an increasingly marked conservative turn (Fowler Reference Fowler2004), leading to the so-called illiberal turn after 2010 (Rupnik Reference Rupnik2012) to finally become a right-wing populist party establishing a populist, autocratic, illiberal, hybrid democracy (Bozóki and Hegedűs Reference Bozóki and Hegedűs2018; Krekó and Enyedi Reference Krekó and Enyedi2018; Enyedi Reference Enyedi2020).

Chantal Mouffe’s work helps us to understand the process. In her book On the Political (2005), she criticizes liberalism and cosmopolitanism from various aspects. She argues that the formation of political identities is based on an “us” versus “them” distinction, which “can always become the locus of an antagonism” (Mouffe Reference Mouffe2005, 16). According to Mouffe, as potential conflict is always present, one of the main goals of democratic politics should be to promote a “tamed” version of antagonism, which she calls agonism. In Mouffe’s approach, the difference between antagonism and agonism lies mainly in the nature of an “us” versus “them” relationship. In antagonism, they are enemies “who do not share any common ground.” At the same time, in agonism, they are “adversaries” who “although acknowledging that there is no rational solution to their conflict, nevertheless recognize the legitimacy of their opponents” (20).

In 2005, Mouffe detected that the frontiers between the left and right had been blurred, to which the disintegration of the bipolar world order also contributed. It did not lead to the emergence of more harmonious, more mature democratic systems but to “the explosion of multiplicity of new antagonisms” (64), and in many countries to the emergence of right-wing populist parties as it happened in Hungary. According to Mouffe, “the announced disappearance of collective identities” (70) did not take place, and the ignorance of “the affective dimension mobilised by collective identifications” (6) is one of the mistakes of liberal rationalism. Mouffe argues that the possibility of universal rational consensus put forward by liberal rationalism is not possible, and “the rationalist model of democratic politics […] is particularly vulnerable when confronted with a populist politics offering collective identifications with highly affective content like ‘the people’ ” (70). We will see that it is precisely what happened in the case of Fidesz.

4 Modes of Remembering

Bull and Hansen distinguish two modes of remembering that lack any interaction: antagonistic and cosmopolitan. Antagonistic remembering “represents the past in terms of a moral struggle between essentialised collective identities, conceiving the ‘other’ as an enemy to be destroyed” (Bull and Cacciatori Reference Bull and Cacciatori2020, 4). It “relies on heritage as monumentalism and on a canonical version of history” (Bull and Hansen Reference Bull and Hansen2016, 390). On the contrary, cosmopolitan remembering “emphasises the human suffering of past atrocities and human rights violations” (Bull and Hansen Reference Bull and Hansen2016, 390) and “represents the past as a moral struggle between abstract systems (e.g., democracy and dictatorship)” (Bull and Cacciatori Reference Bull and Cacciatori2020, 4).

These modes differ in their ability for reflection, self-reflection, and dialogue. Antagonistic remembering is neither reflective nor self-reflective and “is not open to a dialogue with the other, because it sees the other as an enemy, nor does it allow for multiple views” (Bull and Cacciatori Reference Bull and Cacciatori2020, 4). On the contrary, cosmopolitan remembering is reflective and open to dialogues with the other: “It promotes multiple perspectives with a view to aiming at an overarching uniform narrative” (Bull and Cacciatori Reference Bull and Cacciatori2020, 4).

Bull and Hansen argue, building upon Mouffe’s theory, that the cosmopolitan mode of remembering “has proved unable to prevent the rise of, and is being increasingly challenged by, new antagonistic collective memories constructed by populist neo-nationalist movements” (Bull and Hansen Reference Bull and Hansen2016, 390–391). Moreover, they argue that “the proponents of a cosmopolitan memory tend to downplay the significance of neo-nationalism” and “overlook the important and novel role played by memory work in accounting for the increasing popularity of these movements” (393).

Both the antagonistic and cosmopolitan modes of remembering rely on the distinction between good and evil, however, in very different ways. While the former uses these categories as moral ones, where the boundary between the two is sharp and distinct (“us” equals good; “them” equals evil), the latter mode treats good and evil as abstract categories. It is also important to note that the antagonistic mode uses the perpetrator perspective, inasmuch as “us” is portrayed as victims and “them” as perpetrators. However, cosmopolitan remembering deals only with the victims’ perspective and does not deal with the perpetrators’ perspective.

The way the two kinds of remembering simplify past historical events is also very different. The antagonistic mode “opts to turn historical events into foundational myths of the community of belonging,” which means that it is “prone to misrepresent or manipulate the past, promoting forgetting as much as (selective) remembering.” By contrast, “the cosmopolitan mode de-contextualises the past in order to transcend historical particularism and promote a new kind of universalism” (Bull and Hansen Reference Bull and Hansen2016, 395).

It is especially important how the two modes of memory relate to emotions or, as Mouffe called them, passions. In the antagonistic mode of remembering, emotions play an essential role because they “cement a strong sense of belonging to a particularistic community, focusing on the suffering inflicted by the ‘evil’ enemies upon this same community.” The emphasis on suffering allows easy identification for those who see themselves as members of this community and are willing to take up the fight against those enemies. In contrast, the cosmopolitan mode of remembering also deals with emotions but in an abstract form. It focuses “on the suffering inflicted upon humanity, hence upon ‘us all’ as human beings” (Bull and Hansen Reference Bull and Hansen2016, 398). In this sense, the emotions mobilized by the antagonistic remembering are seen as a barrier to rational dialogue.

Bull and Hansen propose a third mode of remembering, building on Mouffe’s critique of cosmopolitanism. They consider this agonistic mode of remembering, as they call it, a possible way to overcome the lack of interaction between the antagonistic and cosmopolitan modes.

5 Memory Politics in Hungary after 1998

Viktor Orbán and his right-wing, national-conservative government first came to power in 1998. They were aware from the very beginning of how important the manipulation of public memory and history, thus memory and identity politics, are in legitimizing power. One of the main mnemonic goals of this period was to equate the horrors of fascism and communism. The House of Terror Museum, inaugurated in 2002 on the Memorial Day of the Victims of Communist Dictatorships, just a month and a half before the parliamentary elections, was particularly designed to serve this goal.Footnote 3 It aimed to disseminate the message and convince Hungarian voters that the political left should be associated with a brutal dictatorship similar to fascism. The inauguration ceremony was part of the electoral campaign as it was before the election, in which the primary opponent was the Hungarian Socialist Party, the successor of the communist party (Apor Reference Apor2014; Laczó Reference Laczó, Kovács and Trencsényi2019). The museum’s purpose was not to present historical facts but to show “the simplistic emotional version of history” (Apor Reference Apor2014, 329). Although the museum was “a spectacular example of directly abusing history for political aims” (330), at the same time it “skillfully and on a large scale, combined with interactive multimedia forms of the 21st century, together created a very suggestive form” (Rainer Reference Rainer and Mörner2020, 145).

In 2002, Fidesz lost the parliamentary elections to the Socialists, and for two consecutive terms left-liberal governments were in power. The period between 2002 and 2010 was characterized by a marked neoliberal turn, especially during the premiership of Ferenc Gyurcsány between 2004 and 2009 (Palonen Reference Palonen2009). Although some weak attempts were made, the left could not create a historical narrative of its own. Moreover, it did not even realize how important this would be (Kiss Reference Kiss and Mitroiu2015; Rainer Reference Rainer and Mörner2020). The left-liberal governments followed the cosmopolitan ways of remembering, and they downplayed the importance of memory politics that Fidesz constructed.

In the eight years of left-liberal governments, Fidesz, continually preparing itself for the takeover, primarily with the help of the so-called Civic Circles (Polgári Körök) initiated by Orbán, rebuilt the Hungarian right and strengthened its (collective) identity (Greskovits Reference Greskovits2020). An important step in this image building while in opposition was the 2004 dual citizenship referendum initiated by the World Federation of Hungarians. In the campaign, Fidesz was the leading advocate of supporting the question that asked whether the National Assembly should pass a law that enabled the simplified naturalization process of ethnic Hungarians with non-Hungarian citizenship. The then-governing left-liberal MSZP-SZDSZ (Magyar Szocialista Párt–Szabad Demokraták Szövetsége) coalition recommended voting against the question, providing an attack surface for being antipatriotic to this day.Footnote 4 Fidesz took an emotional stance during the campaign, depicting the referendum as a historic decision on the fate of Hungarians. At the same time, the governing parties approached the matter from a rational point of view, claiming, for example, that if the neighboring states became EU members, the issue would resolve itself. This example illustrates well the extent to which leftist liberals did not realize the importance of collective identities and the extent to which they ignored the affective dimension. Following Mouffe’s line of reasoning, we argue that these factors played an important role in the success of Fidesz in the 2010 parliamentary elections. Although the referendum was not successful at that time, the debate had a long-lasting effect that, as will be seen, is confirmed by our analysis as well.

In 2010, Fidesz regained power and has retained it in three consecutive elections since then. The constant instrumentalization of history, memory, and identity politics has offered key building blocks for the Orbán regimes (Krekó and Enyedi Reference Krekó and Enyedi2018; Feischmidt Reference Feischmidt2020; Benazzo Reference Benazzo2017; Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020). After 2010, Trianon has been at the center of the Orbán regime’s memory policy resulting in a Trianon cult (Gyáni Reference Gyáni2012b, Reference Gyáni, Miller and Lipman2012c; Feischmidt Reference Feischmidt2020). One of the Orbán government’s first measures was to grant citizenship to Hungarian minorities abroad. The measure was presented as the nation’s unification; however, the votes of these new Hungarian citizens were also crucial for Fidesz. Soon after that, the government declared June 4 “the day of the peace diktat of 1920,” the “Day of National Belonging” (Hatályos Jogszabályok Gyűjteménye 2010), further instrumentalizing history and putting historical debates at the service of politics (É. Kovács Reference Kovács2010).

The two-thirds majority allowed the Orbán government to create a new constitution, the so-called Fundamental Law, in 2011. The preamble to the law titled “National Avowal” carries an important identity and memory policy message by promising “to preserve the intellectual and spiritual unity of our nation, torn apart in the storms of the last century.”Footnote 5 Besides that, it explicitly declares that Hungary lost its self-determination from the day of the German occupation in March 1944 until the first democratic parliamentary election in May 1990, thus suggesting, for example, that the Hungarian state was not responsible for the deportations that happened after the German occupation (Benazzo Reference Benazzo2017; Laczó Reference Laczó, Kovács and Trencsényi2019). This reasoning was especially important for the Orbán regime as it has placed more emphasis than ever on rehabilitating the Horthy era, which has been going hand in hand with its whitewashing and the constant “assault on the historical memory of the Holocaust” (Braham Reference Braham, Braham and Kovács2016, 261). The controversial relationship of the Orbán cabinet to the Holocaust was shown most clearly by the Memorial for the Victims of the German Occupation, inaugurated in 2014 under the guise of the night without any official ceremony: “It depicts Nazi Germany as an eagle descending upon Hungary represented by the archangel Gabriel” (Pető Reference Pető2019, 472), although Hungary was an ally of Nazi Germany till the very end of World War II. The monument deliberately does not differentiate between the victims of World War II and the Holocaust (H. Kovács and Mindler-Steiner Reference Kovács and Mindler-Steiner2015).

It is clear that the Orbán regime follows the antagonistic mode of remembering. The agents of this mode are “mnemonic warriors” (Kubik and Bernhard Reference Kubik, Bernhard, Kubik and Bernhard2014; Bull and Cacciatori Reference Bull and Cacciatori2020). This role perfectly fits with Orbán and his government. According to Orbán and Fidesz, a sharp line exists between “true” and “false” versions of history. There is a contest, if not war, in the field of memory politics between “us,” the custodians of truth, and “them,” the proponents of a “distorted” vision of the past. As the content of collective memory is nonnegotiable, those who have alternative visions of the past must be delegitimized or even destroyed (Kubik and Bernhard Reference Kubik, Bernhard, Kubik and Bernhard2014). The Orbán regime successfully occupied the ideological-symbolic sphere without the opposition being able to create any counternarrative. For the Orbán regime to successfully spread its mnemonic messages, the occupation of the media was a perfect tool.

6 The Media Landscape of Contemporary Hungary

The Orbán regime after 2010 fundamentally transformed the media landscape of the country. The government has been systematically building a centralized media network, suitable for conveying the messages it considers important to as many people and in the most coherent form possible. This is no different for the messages of memory and identity politics.

We would like to show how fundamental and all-encompassing this transformation has been. One of the first measures taken by the Orbán government after their landslide victory in 2010 was establishing the National Media and Infocommunications Authority (NMHH). A highly important, theoretically independent organization within the NMHH is the Media Council, which oversees the distribution of terrestrial frequencies, is responsible for content monitoring, and may impose fines based on ambiguous content restrictions (Bajomi-Lázár Reference Bajomi-Lázár2013, 82). All council members in 2010 and 2019 have been nominated and then elected for nine years by Fidesz, with its supermajority in the National Assembly, without the need to compromise with any other party (Polyák Reference Polyák, Połońska and Beckett2019, 284–285; Kovács Reference Kovács2019).

Since 2010, public service media has also undergone several changes and become entirely controlled by the government. In 2010, all public service providers—state television, radio channels, the Hungarian Press Agency (MTI)—were concentrated in a fund (MTVA), the head of which is appointed by the president of the Media Council (Bajomi-Lázár Reference Bajomi-Lázár2013, 81–82). The conglomerate is not only overly centralized but is under constant political control. The changes did not spare the news agency either, which became the government’s mouthpiece, has a distinct progovernment bias, and rarely features stories showing the government in an unfavorable light (Bajomi-Lázár Reference Bajomi-Lázár2013, 56–57). Moreover, since 2010, the agency provides news free of charge, meaning that most Hungarian media outlets rely on the biased news of MTI.

Since 2010, the political machinations of the Media Council led to the closure of previously successful radio stations and newspapers with long histories, as well as the concentration of various media products into the hands of oligarchs close to the prime minister and the government (Polyák Reference Polyák, Połońska and Beckett2019, 285; Mertek Media Monitor 2016; Griffen Reference Griffen2020). Furthermore, in 2018, the Central European Press and Media Foundation (CEPMF, or KESMA in Hungarian) was created, which resulted in an “unprecedented level of ownership concentration in the Hungarian media market” (Máriás et al. Reference Máriás, Nagy, Polyák, Szávai, Urbán and Urbán2019, 51). The foundation owns 476 media outlets, all of which were voluntarily donated by their owners to CEPMF. The Media Authority did not need to review the creation of this extraordinary media giant since it was declared to be of “strategic national importance,” excluding it from the need for approval by any bureau (Máriás et al. Reference Máriás, Nagy, Polyák, Szávai, Urbán and Urbán2019, 52). In Reference Máriás, Nagy, Polyák, Urbán and Urbán2018, 79 percent of the total public media market was financed by sources decided by the governing party, while the government has a near-monopoly in the daily print and radio sectors. As a result of this centralization, progovernment media outlets–including those of CEMPF, the public service media, and some other companies—closely follow the communication of the governing parties and share the news they consider important with the appropriate interpretation (Máriás et al. Reference Máriás, Nagy, Polyák, Szávai, Urbán and Urbán2019, 57; Griffen Reference Griffen2020, 58–59; Krekó and Enyedi Reference Krekó and Enyedi2018, 45–46).

In this increasingly polarized media system, self-censorship, including holding back information, became prevalent (Schimpfössl and Yablokov Reference Schimpfössl and Yablokov2020, 34), and publishers became increasingly dependent on their financiers (Polyák Reference Polyák, Połońska and Beckett2019, 294–295). There is evidence that the biggest advertiser—the Hungarian state—favors certain companies close to the government, making fair competition on the market impossible. While independent participants are being avoided by state advertising, progovernment actors receive substantial funding from the same source, regardless of their publicity or readership (Bajomi-Lázár Reference Bajomi-Lázár2017, 165–169; Bátorfy and Urbán Reference Bátorfy and Urbán2020; Griffen Reference Griffen2020, 59–60; Krekó and Enyedi Reference Krekó and Enyedi2018, 46; Polyák Reference Polyák, Połońska and Beckett2019, 291–293).

7 Corpus and Methodology

7.1 The Corpus

In our research, we analyzed articles published in the online Hungarian press between September 2017 and September 2020. To acquire our corpus, we used the SentiOne social listening platform. SentiOne gathers content from thousands of websites and makes it searchable using keyword and metadata-based queries.Footnote 6 We used two sets of keywords to obtain documents related to our two topics. We downloaded the full text of all articles published in the abovementioned period that contained the word holo or trianon by themselves or as part of other words (e.g., Holocaust), in a non-case sensitive manner. In the case of Trianon, this method yielded accurate results. However, we had to manually filter out some content resulting from the use of the holo. For example, we considered the words holocaust, holohoax, holosurvivor, holobusiness, and holoindustry as valid results since we were also interested in antisemitic articles found on far-right websites. Still, we filtered out documents that contained the words, for example, hologram, holographic, Holocene, or psychology.

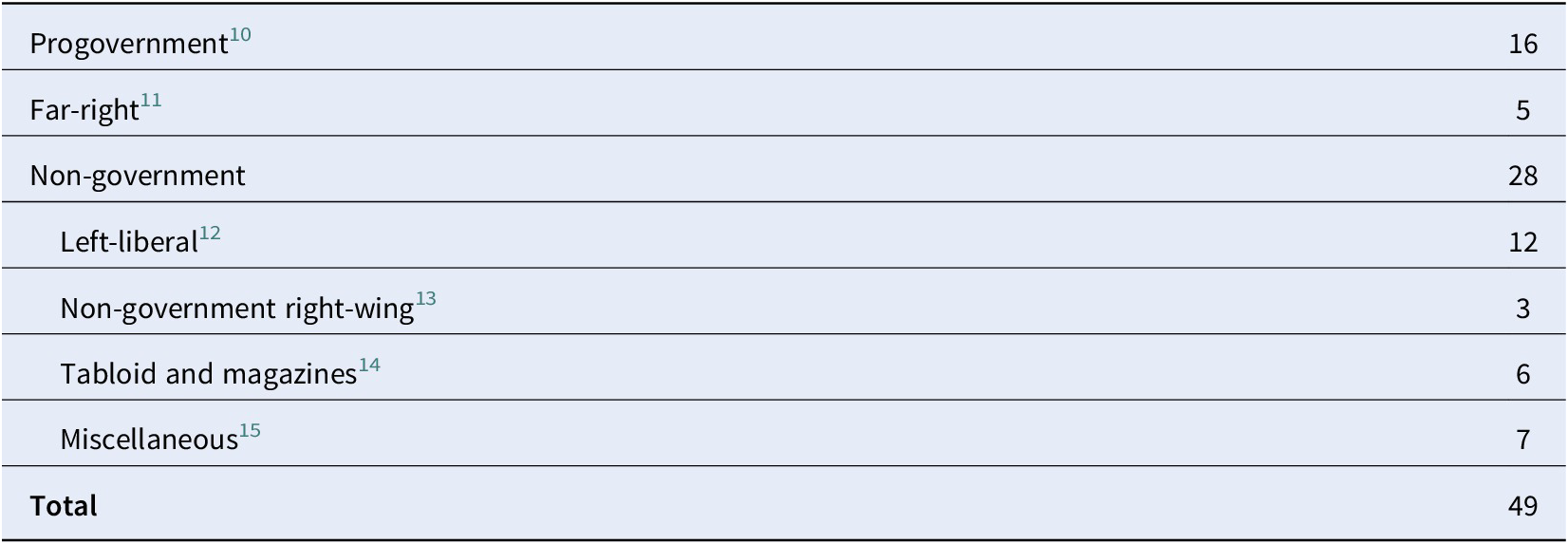

As we wanted to analyze whether the latent topics and the discursive framing of Trianon and the Holocaust differed in articles from sites with different political leanings, we formed three main groups: progovernment, far right, and nongovernment. While the first two groups were politically homogeneous, the latter was not. It consisted of news sites ranging from the Jobbik-related, right-wing Alfahír to the left-liberal Magyar Narancs, as well as tabloid media sites and online magazines. Therefore, we broke down this category into four groups: left-liberalFootnote 7 , nongovernment right-wing, tabloid and magazines, and miscellaneous.

The progovernment category contains outlets from CEMPF and public service media, while the far-right group contains those connected to the far-right party, Mi Hazánk Mozgalom (Our Homeland Movement) and the far-right movement in Hungary.Footnote 8 Our research also included six tabloid newspapers and magazines that do not belong to the progovernment media conglomerate. The tabloid media are represented by one site, which was the sixth most-read website in 2020. The magazines included in our research are women’s magazines, among which we find very and less popular ones. There is one remaining group that needs to be explained. The nongovernment, right-wing group contains outlets linked to Jobbik and others that were created by right-wing journalists whose media outlets fell victim to Fidesz’s ideologically and organizationally centralizing media policy.

Table 2 shows the number of articles in the domain groups described above. At first glance, it may seem that the difference in the number of websites will result in a very diverse number of documents in each group, but it is not the case.

Table 1. Number of Domains in the Created Groups

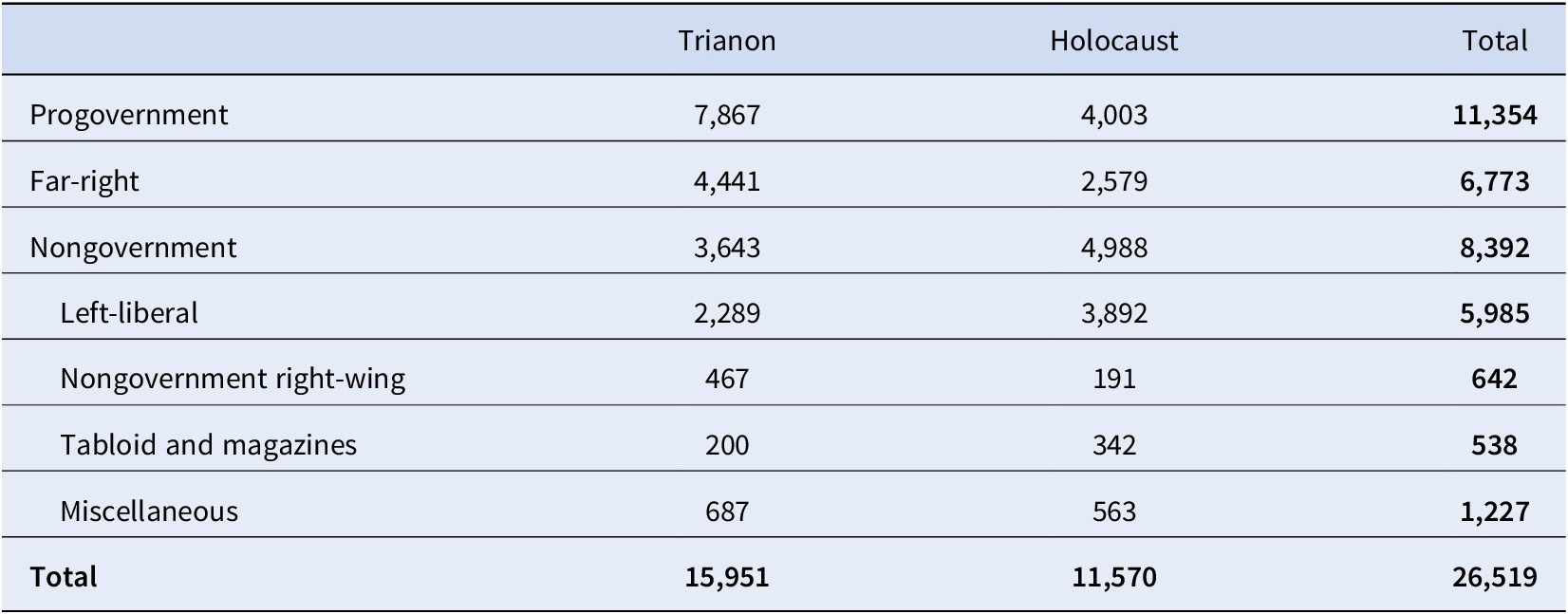

Table 2. Number of Articles in the Domain GroupsFootnote 16

While we classified almost half as many domains in the progovernment group as in the nongovernment group, the number of articles related to Trianon in the former group was more than twice as many as in the latter. Also, concerning the Holocaust, many more articles appeared in the progovernment press than would have been expected based on the group’s size alone. The table also shows that far-right websites were very productive in the two topics under research. The difference is perceptible, even compared to progovernment media, but it is downright striking compared to nongovernment media.

7.2 Methodology

In our research, we applied a mixed-method approach, using both quantitative and qualitative techniques. As we analyzed vast amounts of unstructured textual data, it was necessary to utilize automated text analytical tools—namely, Natural Language Processing (NLP). We used topic modelling to identify the latent thematic structure of articles on Trianon and the Holocaust in the online Hungarian press. Although the use of NLP in general, and topic models in particular, is relatively new in social science and humanities research (Ignatow Reference Ignatow2016; DiMaggio Reference DiMaggio2015; Mohr and Bogdanov Reference Mohr and Bogdanov2013; Mützel Reference Mützel2015; Jänicke et al. Reference Jänicke, Franzini, Cheema, Scheuermann, Brogo, Ganovelli and Viola2015; Németh, Katona, and Kmetty Reference Németh, Katona and Kmetty2020; Németh and Koltai Reference Németh, Koltai, Rudas and Péli2021), there are already good examples of the use of this new methodology to analyze topics connected to ours, such as memorialization (Makhortykh, Lyebyedyev, and Kravtsov Reference Makhortykh, Lyebyedyev and Kravtsov2021), political agenda (Grimmer Reference Grimmer2010), rhetoric (Mohr et al. Reference Mohr, Wagner-Pacifici, Breiger and Bogdanov2013; Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Monroe, Colaresi, Crespin and Radev2010), and discourse (Gülzau Reference Gülzau2020; Curran et al. Reference Curran, Higham, Ortiz and Filho2018). Using topic models allows us to explore the latent structure of huge textual datasets that would not be possible manually. However, we firmly believe that a qualitative analysis, namely, the close reading of the obtained topics, is essential for the appropriate interpretation.

To create our topic models, we used Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), an unsupervised, Bayesian statistical model that detects the co-occurrence of words in a textual corpus and uses this information to unfold its latent thematic structure. The structure is presented to the researcher as a collection of thematic groups or topics, each of which is described by a set of keywords characteristic of the given topic. This comes from LDA’s two fundamental assumptions: (1) every document in a corpus is a mixture of a finite number of topics; and (2) every word in a document can be assigned to one or more of the topics. This also means that (1) a given topic can be characterized using the words connected to it, and (2) a document that is associated with a given topic is more likely to contain the words connected to that topic (Blei, Ng, and Jordan Reference Blei, Ng and Jordan2003; Blei and Lafferty Reference Blei and Lafferty2009; Németh and Koltai Reference Németh, Koltai, Rudas and Péli2021, 59–60; Németh, Katona, and Kmetty Reference Németh, Katona and Kmetty2020, 55–56). In this research project, we used the LDA Mallet implementation (McCallum Reference McCallum2002) via the Gensim Python package (Řehůřek and Sojka Reference Řehůřek and Sojka2010).

Topic modelling requires many preprocessing steps to be conducted on the corpus before running the model itself. Our preprocessing pipeline consisted of six main steps: (1) removing URLs, (2) lemmatization and part-of-speech filtering (keeping only adjectives, adverbs, nouns, numbers, and proper nouns), (3) named entity recognition, (4) trigram and bigram detection and concatenation, (5) stop word filtering, and (6) frequency-based filtering.Footnote 9

During topic modelling, the researcher defines the number of topics prior to running the model, which is often a challenging task without knowing the exact content of the given corpus. To determine the appropriate number of topics, we ran multiple models for topic numbers, ranging from 5 to 30, and analyzed the average and the standard deviation of the

![]() $ {C}_v $

topic-coherence metric (Röder, Both, and Hinneburg Reference Röder, Both and Hinneburg2015), which gives feedback on the overall quality and interpretability of topics. In parallel, we evaluated our models based on a qualitative assessment of the model’s interpretability, and we decided to use a model with 24 topics. To obtain the appropriate interpretation, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the articles, with special—but not exclusive—attention to those that are the most representative of their topic.

$ {C}_v $

topic-coherence metric (Röder, Both, and Hinneburg Reference Röder, Both and Hinneburg2015), which gives feedback on the overall quality and interpretability of topics. In parallel, we evaluated our models based on a qualitative assessment of the model’s interpretability, and we decided to use a model with 24 topics. To obtain the appropriate interpretation, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the articles, with special—but not exclusive—attention to those that are the most representative of their topic.

8 Results

8.1 The Overall Thematic Structure

As the first step of the analysis, we calculated two statistics for each topic: (1) the proportion of texts related to Trianon and the Holocaust, respectively, and (2) the proportion of articles published in the various domain groups, as presented in Table 1. 13 out of 24 topics are primarily dominated by articles about Trianon, while seven are about the Holocaust. At first glance, the lack of common subjects in the progovernment and nongovernment media is striking. What one is talking about, the other is not, and vice versa. This does not mean that what appears in the progovernment media is not at all present on the left-liberal sites, just that there is not a single subject that both types of media would prominently address. This finding supports Rainer’s statement that “the current visions of the recent history of the individual political camps are incompatible” (Rainer Reference Rainer and Mörner2020, 147). At the same time, we do find topics that appear in both progovernment and far-right sites. In addition, a part of the progovernment media that is significantly closer to the far right can be identified.

8.2 The Far-Right Rhetoric

The far-right press was much more concerned with Trianon than the Holocaust, and the discursive framing of Trianon is not at all surprising. Most of the articles dealing with Trianon feature a harsh revisionist and irredentist rhetoric. In one of the many texts remembering the treaty, the author writes: “After the defeat of the First World War, the Trianon peace dictated by the victorious Entente powers gave the neighboring robber states two-thirds of the territory of our country, and one-third of the Hungarian population” (Kuruc.info 2018b). Moreover, several articles remember positively the territorial revisions introduced by the First and the Second Vienna Awards in 1938 and 1940.Footnote 17 There are numerous texts about commemorations, such as that of the Trianon Treaty, as well as the 100th anniversary of Miklós Horthy’s election as Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary. The characteristic phrases used in these topics are “peace diktat,” “Trianon mourning day,” and “Trianon memorial tree.” A few quotes capture the emotional content of these articles: “Our torn-up homeland celebrates its founding” (Kuruc.info 2018a), “We do not put up with the most unjust peace diktat in history” (Kuruc.info 2020b), “They waved national-colored and Árpád-striped flags and sang the ‘Die, Trianon’ rhyme and contemporary songs” (Kuruc.info 2020a).

Articles that deal with Transylvania form a separate topic. The rhetoric of these articles is no different from the previous ones. These pieces are mainly about Székely (Szekler) autonomy, conflicts with Romanians, attacks on Hungarians by Romanian nationalists, and anti-Hungarian prejudices in Romania.Footnote 18

In the far-right online press, one of the most prevalent subjects is communists and liberals’ intrigues against the Hungarian nation—both in the past and the present. This topic frequently comes up regarding Trianon and, as we will see, the Holocaust as well. In these articles, the “communists” and “liberals” are mainly used as code words for Jews. They also suggest that the Hungarian Soviet Republic and the Red Terror were primarily organized by Jews.Footnote 19 One popular character in the far-right press regarding this topic is historian Ernő Raffay, who claims that Trianon was caused by “liberalism” and the “Freemasonic left.” In an interview with the progovernment Magyar Idők (Hungarian Times) in 2018, he also claimed that territorial revision of Trianon is possible if it is supported by a world power and the necessary “clever Hungarian diplomacy, a strong army, and a cohesive nation” (Pataki Reference Pataki2018).

Although the far-right press is overrepresented in this topic, there are also articles from radical progovernment websites.Footnote 20 One of the most prominent is titled “István Csurka’s five thoughts that came true.” Csurka was a radical nationalist politician, the founder of the far-right Hungarian Justice and Life Party (MIÉP). Some typical quotes from this article include the following: “The ultimate goal is to exterminate Hungarians. Not with guns, not with poison gas, but with financial policy, taking away our livelihoods, because the others need a place”; “International big capital and banks are facilitating the migration because it is in their interest. Within the borders of Trianon, Hungary can accommodate twenty million people, but in the foreseeable future, only seven million of them will be Hungarian and four million Gypsies, and the other nine will be all sorts of mixed people” (Nemzeti.net 2019). Another example from the common topic of the far-right and the progovernment press is Sándor Lezsák, a Fidesz MP and deputy speaker of the Hungarian National Assembly. In his speech, he said that “the migration crisis represents a continuing Trianon for Europe, another major post-Cold War era that could also involve cultural, human, and territorial casualties” (Kuruc.info 2019). Not only the words of Lezsák but also that of the clearly far-right Csurka are in line with all that Prime Minister Orbán has been saying, that “ethnic homogeneity must be preserved” (Miniszterelnök.hu 2017).

There is not a single topic that is mainly about the Holocaust, whereas we found the far-right media sites to be overrepresented in this regard. The far-right press primarily deals with the Holocaust in relation to Trianon, which constitutes a textbook case of competitive victimhood. Consider, for example, a typical quote on Trianon: “The Hungarian Holocaust, which, if anyone dared to deny it, would deserve just as much punishment as in the case of any other Holocaust denial” (Stoffán Reference Stoffán2020). In connection with the Holocaust, open or more covert Holocaust denial and relativization appear several times. These articles are dominated by words and phrases typical of the far-right scene (Barna and Knap Reference Barna and Knap2019), such as “Holohoax,” “alleged Holocaust,” “socionist,” “Holohoax Memorial Day,” “holoindustry,” and “holosurvivor.”

8.3 The Communication of Fidesz through the Progovernment Media

There are 9 topics in which the progovernment online media’s articles appeared predominantly. As we mentioned earlier, the far-right press is also overrepresented in some of these topics. Even so, there was not a single topic of the 9 in which the left-liberal media were also predominant, which is a good indication that the narrative of the progovernment press primarily intersects with the far-right in terms of content. Of the topics, 7 out of the 9 mainly deal with Trianon, and the remaining two deal with the Holocaust.

8.3.1 The Discursive Framing of Trianon in the Progovernment Media

Fidesz’s communication about Trianon aimed at reaching a wide range of audiences. Relatively neutral news connected to commemorations and the events surrounding the Trianon centenary form a separate topic in which the progovernment media predominantly appear. It is interesting to note that there is a group of articles about the government’s financial support for Trianon, which form a separate topic, present not only in the progovernment but also in the far-right press. However, while the former’s emphasis is on the government and the financial support itself, the latter’s focus is on the various types of collective identities: the nation, the community, and Hungarians in neighboring countries.

There is another topic in the articles that is overrepresented in both the progovernment and the far-right press. Viktor Orbán’s speeches create a clear link between these two media groups. The central part of this topic is the prime minister’s speeches, which build on the far-right rhetoric described above and a vocabulary that strongly recalls the wording of the revisionist press of the Horthy era. While an open irredentist narrative never prevails in these speeches, contrary to what we have seen in the far-right press, the tone is often consistent with the far-right. These texts are often intended to evoke strong emotions. Some characteristic quotes include the following: “This is our home; this is our life; there is no other, so we will fight for it to the end, and we will never give up” (Miniszterelnök.hu 2018).Footnote 21 Or another one, “What was once unjust will remain until the end of time. […] Time heals wounds but does not heal amputation. The time that has passed has not changed anything, because what happened ninety-nine years ago was not a trial but an ultimatum. A punishment imposed on us for losing the war” (Magyar Nemzet 2019).

Articles about one of the Trianon Memorial Year’s major events in 2020, the inauguration of the Trianon Monument—the so-called Monument of National Unity—also belong to this topic. The monument is a 100-meter-long, 4-meter-wide sloping promenade facing the Hungarian parliament. On both sides of the promenade, the names of all the settlements belonging to Hungary according to the 1913 census are engraved on separate granite bricks.Footnote 22 Traditionally, the inauguration of military officers is held on the same day, and the prime minister gives a speech to them. This year, in his speech, Orbán used similar rhetoric to that described above. Let us quote only one part from the speech: “Few of you here today know what an important role awaits you in shaping the future of a Hungary that is now regaining its self-respect, that is now breaking free from the captivity of a hundred years of Trianon, that is now rediscovering a taste for its old greatness and the path toward it, that is now casting off the miserable rags of defeatism and subservience” (Miniszterelnök.hu 2020c)

One of the most important parts of Fidesz’s communication about Trianon was its reframing—namely, to make the Hungarian nation, the former victim, a hero. To achieve this goal, the collective victimhood of Hungarians is usually mentioned together with the “strong nation” that was able to not only survive the “peace diktat” but today is stronger than ever. One of the good examples is Viktor Orbán’s usual “state of the nation” address at the beginning of 2020. He started as follows: “I am extremely fortunate not to be delivering a state of the nation address in Hungary one hundred years ago.” He then listed at length the events that preceded the “Trianon peace diktat.” However, listing them was only a rhetorical preparation for presenting Hungary and the Hungarian nation as a hero that survived all this: “Today, one hundred years after the Trianon death sentence, I can tell you that we are alive and that Hungary still exists. And not only are we alive, but we have escaped from the grip of the surrounding circle of enemies” (Miniszterelnök.hu 2020a). Of course, naming the enemies, the opposition was not left out, including the alleged mastermind behind everything, George Soros. In the later part of the prime minister’s speech, he also made it clear that becoming a hero has primarily been made possible in the past ten years by him and his party.Footnote 23

The emotional climate of the government’s and Fidesz’s communication to different audiences vary. Unsurprisingly, more extreme messages are more emotional. One of the topics used to mobilize emotions is sport, as it can increase national pride. The Orbán government often uses sport in its identity policy (Dóczi Reference Dóczi2012; Molnar and Whigham Reference Molnar and Whigham2019; Dóczi and Molnar Reference Dóczi, Molnar, Rojo-Labaien, Díaz and Rookwood2020), and this was also the case in relation to Trianon. The following quote from the prime minister clearly shows this: “There will also be [the centenary of the Treaty of] Trianon, and in this context, we ought to say something about football. We don’t usually say it out loud, but football isn’t just a game: it’s life itself. […] So, for a nation like us, football always provides the opportunity for consolation and recompense; and so it should be treated not just as a sport but also as part of culture and history” (Miniszterelnök.hu 2020b). In this topic about sport, we also find articles about matches played in or against teams of neighboring countries, wherein mutual grievances and Trianon are often mentioned. The most discussed sport-related event on this topic is the Honvéd-Craiova football match, which ended in turmoil.

8.3.2 The Main Topic about the Holocaust: Discrediting the Opposition

As mentioned earlier, there were two Holocaust-related topics where articles in progovernment media were overrepresented. One of these is less important to us now: it consists of foreign news connected somehow to the Holocaust. The other topic, however, is about nothing else than a collaboration between the opposition and Jobbik.Footnote 24 These articles are mainly about Jobbik politicians’ antisemitic cases, primarily from before Jobbik’s centrist turn.Footnote 25 The continuous appearance of these scandals in the progovernment media aims to discredit Jobbik and, in this way, the entire opposition coalition. The left-liberal side has long dominated the discourse on the Holocaust. However, as they entered the coalition with Jobbik, it enabled the Orbán regime a possibility to deprive them of their monopoly over the discourses about the Holocaust.

8.4 Topics in the Left-Liberal Online Media

There are five topics in which the left-liberal press is overrepresented. Two of them deal almost exclusively with the Holocaust. The other three deal with both the Holocaust and Trianon, one focused more on the Holocaust and the other two on Trianon.

8.4.1 The Discursive Framing of Trianon in the Left-Liberal Media

The first striking observation is that the left-liberal media lack any emotional relationship with Trianon. This is fully consistent with what Bull and Hansen (Reference Bull and Hansen2016) wrote on the cosmopolitan mode of remembering and Feischmidt (Reference Feischmidt2020) on the Trianon cult. First, we want to show an eloquent example of this lack of emotions. In 2020, the mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony, contrary to past practices on his side of the political spectrum, tried to remember Trianon, not only as a historical fact but also with an emotional attitude.Footnote 26 He proposed that the city, meaning all public transportation services, should stop for a minute at 4:30 p.m. on June 4.Footnote 27 Karácsony asked everyone to “stop your cars, bicycles and those on foot,” to let every citizen “hear the closeness of each other across the borders and between past and future generations. […] Then, after a minute of silence, let life move on with being a little closer to each other” (Presinszky Reference Presinszky2020).

His original call on Facebook was shared by many news outlets. However, the manner of doing so depended greatly on the political orientation of the particular media. The topic, mostly containing articles about the Karácsony case, was predominantly presented in the progovernment and far-right media and appeared much less in any other types of non-government press, including the left-liberal media. In the former, the articles featuring the reactions of the political right expressed, mostly and surprisingly, a positive emotional attitude toward the proposal. Even the prime minister struck an unusual tone when asked by journalists by saying that he “highly appreciates the mayor’s decision to initiate a commemoration of Trianon in the capital” (Blikk 2020). Moreover, Orbán said that “the message of the centenary of the Trianon peace diktat is that although there may be political differences between us, we all belong to the same Hungarian nation.” At the same time, the reaction of the speaker of the Hungarian National Assembly differed significantly as he questioned the sincerity of the initiative. He said that “some of the [left-wing politicians], out of political calculation, try to set themselves as pro-nation on certain issues, but at the crucial moment, their left-liberal cloven hoof shows” (Magyar Hang 2020).

On the contrary, the left-liberal media presented Karácsony’s case in a completely neutral tone, only reporting the facts while avoiding any discussions or emotions about it. The proposition itself predominantly appeared in short articles containing Karácsony’s original Facebook post, and just a few sentences were provided for context, with a neutral tone. In summary, these articles do not evaluate or criticize the proposition itself; they tend to analyze opinions and reactions by government officials and opinion leaders. One of the radical portals of the government media pointed out, albeit controversially, this lack of interest on the left-liberal side: “Gary Bogus [Kamu Geri] tries to forge political capital with Trianon, but his voters are not interested’ (Vadhajtások 2020a).

There are two topics predominantly containing articles connected to Trianon in which the left-liberal media are overrepresented. One of them is a very coherent topic, containing articles about memorials, exhibitions, museums, historical photos, and buildings that can be summarized as “remembering Trianon.” The articles on the other topic mainly deal with literature and writings related to Trianon. In this topic, the nongovernment right-wing press is also overrepresented. The articles in these two topics again not only predominantly lack any affective attitude but also “de-contextualise the past” (Bull and Hansen Reference Bull and Hansen2016, 395).

8.4.2 The Discursive Framing of the Holocaust in the Left-Liberal Media

As we have already mentioned, there is a topic in which the left-liberal media are overrepresented where articles regarding both the Holocaust and Trianon were present. The topics that connect the two are the very subject of this article: memorialization and memory politics. These articles mostly contain reports on scientific research and analyses, as well as interviews with researchers. In line with the cosmopolitan mode of remembering, this topic deals with the Holocaust from the victims’ perspective and again in a very neutral, scientific form.

There are two topics characterized by a strong predominance of Holocaust-related articles, primarily present in the left-liberal media. One of them is mainly about commemorations and other events, while the other one is about the government’s controversial memory politics concerning the Holocaust. There is a common theme connecting the two, which also forms the core of many other articles: responsibility. However, the articles in the two topics approach it from very different angles. In the first topic, the issue of responsibility is mostly related to some kind of apology. For example, there was the case of Zoltán Pokorni, the mayor of Budapest’s 12th district from the governing Fidesz party, who spoke about his grandfather, who, as it turned out, was a member of the Arrow Cross Party and collaborated with a renegade priest responsible for mass murders. Pokorni spoke on a commemoration in tears, saying, “We are one in pain” (Marosán Reference Marosán2020). In the other topic, the issue of responsibility appears in connection with the government’s memory politics. The most common subject in these articles is how the Hungarian government is trying to whitewash the Horthy regime and shift the responsibility for what happened during the Holocaust to the Germans.

8.5 Topics in the Tabloid Media and Online Magazines

There are three topics in which the tabloid media and magazines were overrepresented. In one of them, in which the left-liberal media are also somewhat overrepresented, we mostly find life stories of Holocaust survivors. These articles also present the perspectives of the victims; however, they have an emotional charge. A very peculiar topic contains articles mainly about hiking, travel, and tourism. The articles here mention Trianon—for example, regarding a detached settlement from the country—while primarily dealing with other subjects. The third one is about culture, films, and theater connected to both Trianon and the Holocaust. However, these two topics already clearly follow the cosmopolitan mode of remembering.

9 Conclusion

In our research, we examined the discursive framing of Trianon and the Holocaust in today’s Hungarian online media. Our corpus contained 26,519 articles connected to these two historical events published in the online Hungarian press between September 2017 and September 2020. We used a mixed-method approach by combining computational text analysis, namely, LDA topic models and qualitative methods. Our aim was not only to map the latent thematic structure and the discourses about Trianon and the Holocaust but also to identify the main differences in memorialization and framing on the different sides of the political spectrum.

In our article, we used Mouffe’s theory (Reference Mouffe2005) and the modes of remembering proposed by Bull and Hansen (Reference Bull and Hansen2016) as our theoretical framework. The discourses of the far-right and the government media follow the antagonistic mode of remembering. The far-right narrative about Trianon uses harsh irredentist and revisionist language evoking the interwar period. Although Orbán does not use these discursive elements, the tone of his speeches often resembles that of the far right. The two narratives had another intersection, namely, the responsibility for Trianon leading to naming the enemy of the nation. From 2010, the national-conservative politics of memory in the 1990s “was supplemented by one element […], which stated that in the 20th century, every left-wing party was always anti-national in its aims, sometimes directly serving foreign powers. This appeared to be a continuation of one of the fundamental areas of Horthy’s discourse, according to which the Treaty of Trianon was the responsibility of Hungarian liberals, radicals, leftists, Jews and communists” (Rainer Reference Rainer and Mörner2020, 145). However, the government not only legitimizes far-right views with its rhetoric but also with those who it considers worthy of a state award. There are plenty of examples to be listed. Still, we mention only one: the previously mentioned Ernő Raffay, despite his extremist and antisemitic views, received the Knight’s Cross of the Hungarian Order of Merit in 2020.

In the case of Trianon, in addition to the similarities, we must highlight a significant difference between the rhetoric of the far right and the government. In relation to Trianon, the far right is only “mourning” over the “torn-up homeland,” while Fidesz is already focusing on the future and carving a hero out of the once defeated nation. As Andrea Pető writes, “It has a very clear vision of the future, and the past is playing an important role in appropriating the past. The clear strategic vision of the future makes revisionism powerful. It deals with the emotional well-being of the followers offering them emotional redress” (Reference Pető2017, 9–10).

In the rhetoric of articles about the Holocaust, there is much less overlap between the far-right and progovernment press. In the former, Holocaust denial and relativization often occur. The Holocaust also often appears in connection with Trianon, and in these articles, competitive victimhood narratives are predominantly present.

The issue of responsibility is at the center of the Orbán government’s Holocaust rhetoric. As it aims at distancing the Horthy era from the Holocaust, in accordance with the antagonistic mode of remembering, they “manipulate the past, promoting forgetting as much as (selective) remembering” (Bull and Hansen Reference Bull and Hansen2016, 395). It is precisely what Andrea Pető (Reference Pető2014) calls the nonremembering of the Holocaust.

It has been discussed before, and it was clear from our results as well, how different the relationship of antagonistic and cosmopolitan mode of remembering to emotions is. Feischmidt (Reference Feischmidt2020) analyzes the relationship between memory politics and neonationalism. She argues, and we found the same, that the most important difference between the left-liberal and the right-wing discursive strategies lies precisely in the use of emotions. The former is characterized by “detachment from the emotional aspects,” while the latter is characterized by the “eleva[tion] the Trianon discourse into the emotive and symbolic domain” (Feischmidt Reference Feischmidt2020, 132). Feischmidt goes even further when, in our view, she rightly states that “the current wave of memory politics became the engine of new forms of nationalism,” which she calls neonationalism (131). Our research has shown that the political left-liberal side has been paying a high price for not recognizing the importance of memory politics in time. It would be worthwhile for them to develop their own historical narrative and to not let the neo-nationalist, populist right to monopolize the field of memory and identity politics.

As discussed earlier, the reconciliation of the antagonistic and cosmopolitan modes of remembering would be possible by developing agonistic remembering. Agonistic memory is reflective, open to a dialogue with the other but does not presuppose that it would lead to consensus. “Agonistic memory promotes radical multiperspectivity” as “it also incorporates the perspectives of the perpetrators, not in order to legitimise them but in order to understand the historical and socio-political conditions, as well as the passions that led to perpetratorship” (Bull and Cacciatori Reference Bull and Cacciatori2020, 5). However, in the present situation, there is no chance for agonistic remembering to become the dominant mode.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for Maria Alina Asavei, and Diána Gabriella Bartha and thank them for the inspiring and helpful comments and ideas that helped improve the article.

Financial Support

Ildikó Barna was supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office — NKFIH grant K 134428. Árpád Knap was supported by the ÚNKP-20-3 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Disclosures

None.