Introduction

About 250,000–500,000 Romani were persecuted by the Nazis and their allies and collaborators in Europe during World War II. The estimated number of Roma genocide victims within the borders of today’s Ukraine varies from 20,000 to 72,000 individuals. All figures are tentative, for they are based solely upon the few available records (Kruglov Reference Kruglov2009; Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk2016b). The Roma genocide, which is recognized as such by international law, has a strictly defined legal meaning. The key notion for the legal evaluation of its genocidal nature is intent. Legal theory treats dolus generalis and dolus specialis differently in cases of mass crimes against humanity. It means that a genocide did not occur when the mass murder of individual members of an ethnic group (dolus generalis) did not have the specific intent (dolus specialis) of exterminating the community as such (Schabas Reference Schabas2000, 213–225). The Nazi annihilation of Roma and Jewish people is, in a legal sense, genocide, the mass killings of the Slavic population by the Nazis were crimes against humanity.

Babi Yar (Babyn Yar in Ukrainian – Old Woman’s Ravine) is a chain of seven deep ravines in the north-western part of Kyiv. The site is considered to be the single largest Nazi extermination site in the former Soviet Union. There, between September 1941 and November 1943, the Nazis murdered about 77,000 individuals, mostly Jews, but also Romani, POWs, mental patients, and members of the anti-Nazi resistance (Berkhoff Reference Berkhoff2012; Berkhoff Reference Berkhoff2018, 87–92).

Theory and method

Pierre Nora and Lawrence Kritzman proposed a concept of two types of collective memory: minor memory and major memory. They have noted that the inclusion of a minor memory of a certain group into a national historical narrative (major memory) takes place through the sites of memory (Nora and Kritzman Reference Nora and Kritzman1997). Every modern state is involved in the forming of a national memory narrative, which always has a strongly engaged political meaning. The project of a new monument initiated by memory actors could be sanctioned by the authorities, edited, or rejected. Memorials are one of the most powerful physical sites of memory, connecting a remembrance date of a historical event with agents of memory and memory practices. The memorials bring sacral meaning to mass graves from world wars that occupied a central place in the cultural landscape of modern Europe (Baer Reference Baer2000; Pickford Reference Pickford2005). The approved design of a public monument often illustrates major memory narratives. Through memorials, a minor memory of a certain group could be included or excluded from a major memory narrative. Another theoretical and methodological approach for this study is the path-dependent analysis proposed by Jeffrey Olick in the study of historical anniversaries in post-war Germany (Olick Reference Olick1999). Olick formulates a process-relational approach that recognizes memory as an ongoing process that links the past and the present in dialogically contingent ways. He developed the concept of cultural mechanisms of commemoration’s path dependency. According to Olick the path dependence is a tool through which one can track and analyse changes in the construction of historical narratives. At the same time, as Evgenii Dobrenko noted, in the study of the late Stalinism, the Soviet narrative of World War II changed all the time, depending on the political context, and had no monolithic character (Dobrenko Reference Dobrenko2020). This article examines the development of memory narratives and memory practices of the Roma genocide in Ukraine as an interplay between the process of documentation of the Nazi crimes, the changing political agenda and activities of various memory actors. The methodology of the study is based on a micro-historical approach. Micro history does not mean ignoring a macro-historical perspective. On the contrary, through the site of Babi Yar in Kyiv it is possible to trace principal changes of memory narratives and memory practices of the Roma genocide in Ukraine. The article examines certain effects generated by memory actors which led to changes of the major narrative of World War II in Ukraine, and the creation of new memory practices: How the process of inclusion of the Roma genocide into the major narrative of World War II does depend on the political context and the state of knowledge production? How changes in the major narrative of World War II affected the memory practices of the Roma community? The memory and memory practices of the Roma genocide are studied in a comparative perspective in relation to the memory of the Jewish genocide in Ukraine. The comparative analysis of memory narratives and practices of the Roma genocide in Soviet and post-Soviet Ukraine in relation to other countries is beyond the scope of this article. Chronologically the article is focusing on three time periods:

-

- World War II and the post-war years of the rule of Stalin

-

- Liberalisation in the Soviet Ukraine during Khrushchev’s thaw and Gorbachev’s perestroika,

-

- The post-1991 independent Ukraine

Background

The Roma people in Ukraine are not a homogeneous ethnic group. Ukrainian Romani are divided into several sub-cultural and religious groups, the largest are Ukrainian Servy followed by the Russian Tsigane, Romanian Kelderari, Hungarian Lovari, Crimean Chingené and others. The first census of 1926 introduced ethnicity as a basic Soviet statistical category (Blum and Mespoulet Reference Blum and Mespoulet2003). The census counted 61,234 Romani in the Soviet Union, of them only 13,578 in Ukraine (the 1926 All-Soviet census). The local government of Ukraine believed that many Romani remained invisible for census takers due to a vagrant way of life. On behalf of the republican government, professor Oleksei Baranikov began in 1928 a massive investigation of Romani in Ukraine. He counted 691 Romani in the Kyiv region, many of them were vagabonds (Baranikov Reference Baranikov1931, 15). The vagrant lifestyle of the Roma was a great concern for the communist regime, which considered this to be a major obstacle for their socialist transformation and control (Kilin Reference Kilin2005). In Soviet imagination, vagabondage and poverty made Romani “a most backward minority” (O’Keeffe Reference O’Keeffe2010). Therefore, the main goal of nationalities policy towards Roma was to settle them down in order to overcome their nomadic way of life and their “backwardness,” and to develop them in the short term to a higher level, like other national minorities. Altogether 52 Roma kolkhozes were established in Soviet Ukraine prior to World War II (Belikov Reference Belikov2008, 35–36). However, many Romani abandoned kolkhozes due to maladjustment to farming. Therefore, a special programme was launched and Roma who worked with crafts were invited to build up craft cooperatives in the cities (Belikov Reference Belikov2008, 36). In 1937, a group of itinerant Kelderari Roma was settled in the vicinity of Babi Yar. There were 27 families of metal workers who founded a cooperative named Trudnatsmen (National minority’s workers) near the village of Kurenivka.Footnote 1 A collective petition sent by the Roma to Kyiv authorities mirror discourses of Soviet nationalities politics:

We are writing to You with a great earnest request to help us in our grief. We are in a difficult situation living in a camp on the open space. Previously, we were nomads, a dark illiterate people – that is our nation. But now, thanks to the Soviet power, we began to work on the manufacturing and treatment of metal goods.Footnote 2

Since the nineteenth century, the territory around Babi Yar was a home for social outcasts, prisoners and mental patients, as well as a burial place. The Kyiv psychiatric hospital with about 1300 mental patients and Lukyanivska Prison with about 25,000 inmates neighboured the Romani village. The village was surrounded by Christian Orthodox, military and Jewish cemeteries, and the Lukyanivska goods station. It was not by accident that the Nazis chose Babi Yar as a site of mass extermination in September 1941. After June 22, 1941, Kyiv was under martial rule and local Romani had few chances to leave the town. In 1941, Nazi Germany occupied central Ukraine. The largest area of the republic including Kyiv became a part of the civil zone called the Reichskommissariat Ukraine. On 29–30 September 1941, nine days after the German occupation of Kyiv, more than 33,000 Jewish civilians were exterminated by the Nazis at Babi Yar in two days of mass killings. At the same time, a German physician Gustav Schuppe visited the Kyiv psychiatric hospital. His team of about ten physicians and SS-soldiers dressed as medics used lethal injections to murder mental patients, including those who were of Roma origin (Rhodes Reference Rhodes2002 178–179). The mass killings of the Roma population by the Nazis began in 1941 and continued in Kyiv until the liberation of the city (Kruglov Reference Kruglov2002, 78). Academic publications about the mass killings of Roma at Babi Yar are based on testimonies collected by Soviet authorities after 1943. According to them, the first group of Romani were killed at Babi Yar in September 1941 (Levitas Reference Levitas1993; Berkhoff Reference Berkhoff2008, 41, 60, 221; Berkhoff Reference Berkhoff2012). The survivor of Roma genocide Volodymyr Nabaranchuk, a native of Kyiv, stated that in addition to the population of the Romani village near Kurenivka, the Nazis killed Romani in other suburbs of Kyiv with compact Roma populations (Nakhmanovich Reference Nakhmanovich, Hrynevych and Magocsi2016, 96–97). However, no exact information about the progress of killing actions, victims and perpetrators was found in Soviet, Ukrainian or German archives (Kruglov Reference Kruglov2011).

Babi Yar and the Roma: the first Soviet Reaction

Even during the war, official media made some efforts to raise public awareness about the mass extermination of Roma by the Nazis in the occupied territories of the country. A few articles were found, published in 1942–1945 by central newspapers, describing the extermination of Roma in the occupied territories of the Soviet Union as a whole (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk, Andersen and Tornqvist-Plewa2016c). Concerning Babi Yar, recent research shows that in 1943–45 the Soviet media reported frequently about the extermination of Jews at Babi Yar (Berkhoff Reference Berkhoff2018, 85–87). However, less is known about the Roma victims of Babi Yar. After the investigation of articles published in 1943–45 by central press about Babi Yar and Nazi crimes in Kyiv, we can conclude that no one mentioned the mass killings of Romani. The ethnic origin of the victims was defined by official prints as Jewish, Ukrainian, and Russian (Kriger Reference Kriger1943; “Doroga na Berlin,” Krasnaya Zvezda, February 15, Reference Grossman1945; “Babi Yar,” Krasnaya Zvezda, November 20, 1943; Dubina Reference Dubina1945, 5–7). After the liberation of Soviet Ukraine three renowned writers and army correspondents of Jewish origin, Vasily Grossman, Ilya Ehrenburg and Lev Ozerov, began to collect testimonies and records about the Nazi extermination of Jews. Some of these testimonies were published by them in media. The entire manuscript with records and oral testimonies was completed in 1945, but banned by censorship and only published in Russian in 1993 (Grossman and Ehrenburg Reference Grossman and Ehrenburg1993).Footnote 3 The book titled Chernaya kniga (Black Book) had a chapter about Babi Yar edited by Lev Ozerov, a native of Kyiv. The mass killing of Roma was not mentioned by Ozerov (Grossman and Ehrenburg Reference Grossman and Ehrenburg1993, 17–24).Footnote 4 Unlike Jewish victims at Babi Yar and other places, the Roma were not mentioned in the widely disseminated international note on Nazi atrocities announced in January 1942 by Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov (Nota 1954). Therefore, the public link between the site of Babi Yar and mass killing of Roma was missed from the very beginning. As Karel C. Berkhoff pointed out, the absence of significant foreign factors was a main reason for the lack of political interest of Soviet media to the mass shooting of Roma by the Nazis. He has noted that “in the eyes of the Kremlin, Gypsies, who actually were subject to the same mass extermination as Jews [Stalin did know about that] had no political value” (Berkhoff Reference Berkhoff2010, 116).

The Concept of Peaceful Soviet Citizens and the Roma Genocide

The concept of peaceful Soviet citizens (mirnye sovetskie grazhdane) that define the civilian victims of Nazi crimes was launched by official media in 1942–44 (Soobshcheniia Sovetskogo Informbiuro 1942, 1944, 354; “Sudebnyi protsess” 1944).Footnote 5 Telling about the Nazi crimes against the Jews and Romani as well as other groups of civilian population, the Soviet media tended to avoid mentioning the ethnicity of murdered people, presenting the civilian victims of the Nazi atrocities as peaceful Soviet citizens. Therefore, the first publications about the massacre of Jews at Babi Yar presented the victims as just peaceful citizens of the Soviet Union or peaceful residents of Kyiv (“Ocherednaya provokatsiya fashistskikh ludoedov,” Izvestiia, August 12, 1943; “Tovarishchu Stalinu ot trudiashchikhsia goroda Kieva,” Izvestiia, December 3, 1943; Leonov, “Yarost’. Iz zala suda,” Pravda, December 16, Reference Leonov1943; Ehrenburg “Iz zala suda,” Krasnaya Zvezda, December 19, Reference Ehrenburg1943; “Rech’ deputata L. R. Korniets, Ukrainskaya SSR,” Izvestiia, February 4, 1944; “Soobshchenie Chrezvychainoi Gosudarstvennoi Komissii po ustanovleniu i rassledovaniu zlodeianii nemetsko-fashistskikh zakhvatchikov i ikh soobshchnikov o razrusheniyakh i zverstvakh sovershennykh nemetsko-fashistskim zakhvatchikami v gorode Kieve,” Izvestiia, February 29, 1944; “Sudebnyi protsess po delu o zlodeianiiakh nemetsko-fashistskikh zakhvatchikov na territorii Ukrainskoi SSR,” Pravda, January 25, 1946).

In 1944, the central party newspaper Pravda published a report of the Extraordinary State Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Committed by the German-Fascist Invaders and their Accomplices in Kyiv (hereafter the ChGK). The commission was led by Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of Ukrainian SSR (see figure 1). The report ignored the ethnicity of civilian victims of Babi Yar and presented them as “ordinary Soviet citizens, women, children and old folk” (“Soobshchenie Chrezvychainoi Gosudarstvennoi Komissii po ustanovleniu i rassledovaniu zlodeianii nemetsko-fashistskikh zakhvatchikov i ikh soobshchnikov o razrusheniyakh i zverstvakh sovershennykh nemetsko-fashistskim zakhvatchikami v gorode Kieve,” Izvestiia, February 29, 1944).

Figure 1. Soviet Extraordinary Commission for Investigation of Nazi Crimes’ Office in Kyiv. 1944. Private collection of Natalia Zinevych.

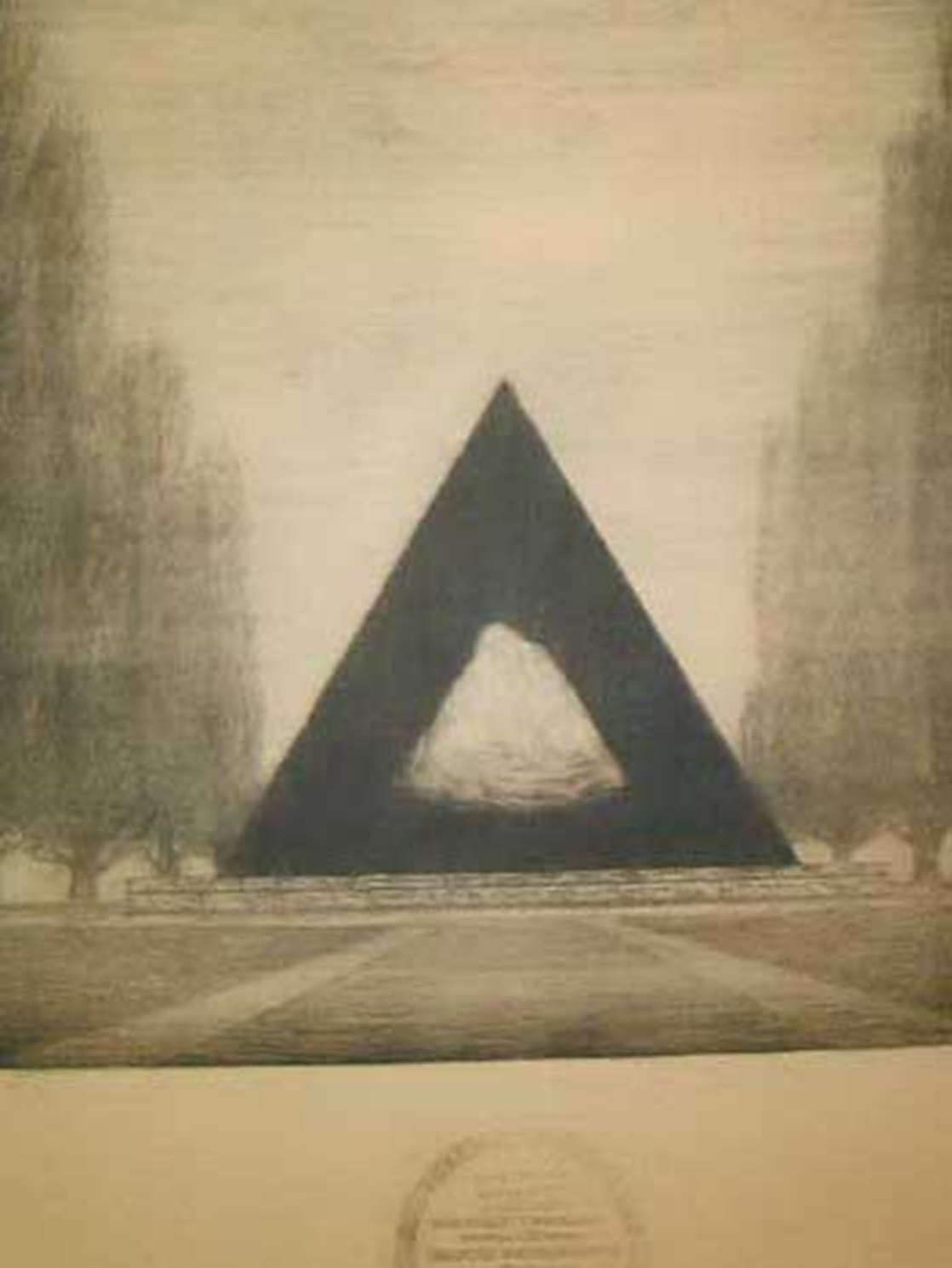

This definition was made despite the ChGK investigation that collected many sources on mass extermination of Jewish and Roma population. For example, Ivan N. Zhitov, a professor at Kyiv Institute of Forestry, stated that the Germans started to shoot Romani at Babi Yar three months after the massacre of Jews, meaning at the end of December 1941.Footnote 6 Ludmila I. Zavorotnaya stated that during the occupation of the town she saw many gypsy wagons with people guarded by the Nazis drive past her house towards Babi Yar. N. Tkachenko claimed to have seen a lot of traditional gypsy clothes left by perpetrators in Babi Yar (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk2014, 27–28). In 1945, ChGK records were defined as classified and the commission was dissolved. Publishing of information about the ethnicity of victims was not prohibited officially. The list of unacceptable information, edited by the General Directorate for the Protection of State Secrets in the Press, only prohibited mention in mass media of the number of victims among civil population (Perechen’ 1949, 20–22).Footnote 7 Post-war public silence about the ethnicity of Roma victims of Babi Yar can be interpreted against the background of the so-called internal censorship, in which memory actors had to follow the lines of the major narrative of World War II. As Ivan Katchanovsky pointed out “Soviet academic and public discourse concerning the war was heavily politicized and censored, and some historical facts and data were falsified to reflect the party line and official ideology” (Katchanovsky Reference Katchanovsky2014, 217). The official concept of peaceful Soviet citizens affected the knowledge production, and the development of memory narratives and memory practices of the Roma genocide in Ukraine. The war against Nazi Germany was named “The Great Patriotic War of the Soviet nation,” a term that appeared in Pravda on June 23, 1941 for the first time, on the day after the Nazi invasion (Yaroslavsky “Velikaya otecchestvennaya voina sovetskogo naroda,” Pravda, June 23, Reference Yaroslavsky1941). The major narrative of the Nazi occupation at that time had a strong focus on heroes (partisans and underground fighters) but not on civilian victims. Hundreds of memorials devoted to dead soldiers, partisans and underground fighters were erected in Ukraine after 1945. Few of them were dedicated to civilian victims, and as a rule, without naming their ethnicity. However, the situation of memorialisation of the Jewish and Roma genocide during the first decade after the war was different. The struggle of Jewish intelligentsia for recognition of Nazi crimes led to some compromises with the state. On many Jewish mass graves, monuments were erected through the initiative of survivors and military veterans of Jewish origin. Most of these had a politically correct inscription about peaceful victims of fascism, which, however, often were doubled by inscriptions in Yiddish. The letters left no doubt about the ethnic origin of the victims (Altshuler Reference Altshuler2002). Holocaust monuments appeared in the Soviet Union at many Jewish cemeteries emphasizing the ethnicity of the dead (Zeltser Reference Zeltser2018). At the same time, most of the Roma genocide mass graves remained unmarked (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk, Andersen and Tornqvist-Plewa2016c). Alaina Lemon has pointed out that because victory over Nazism was seen to be achieved by all nationalities of the Soviet Union, the Nazi extermination of civil population was depicted as a tragedy for the entire Soviet nation without specifying the victims of the Roma genocide (Lemon Reference Lemon2000, 148). In 1945, Pravda informed its readers about the decision of the communist party to build a Memorial and Museum in Babi Yar “to the memory of tens of thousands of peaceful citizens of Kyiv” (“Pamiatnik pogibshim v Bab’em Yaru,” Pravda, April 3, 1945) (see figure 2). The fact that most of the victims of Babi Yar were Jews and Romani was ignored.

Figure 2. The 1945 project of the memorial at Babi Yar. Private collection of Natalia Zinevych.

However, no memorial was built until 1976, and the site remained unmarked after the war. Having avoided a public discussion on the genocidal nature of the massacres at Babi Yar, the authorities stopped previous plans for memorialization of the site and dampened the historical narrative of the tragedy. The largest site of the Nazi extermination was not recognized by the state and was deprived of legal protection (Burakovskiy Reference Burakovskiy2011). In 1961, as a result of an accident at the brick factory that had been built at Babi Yar after 1945, the dam securing large volumes of pulp collapsed and destroyed most of the ravines and mass graves.

In post-war Soviet Union, there was little recognition of Roma as an ethnic group specifically and systematically targeted for persecution by the Nazis. The state preferred to treat the Roma as a part of the entire group of civilian victims called peaceful Soviet citizens, who suffered during the temporary occupation of the country. Romani of Kyiv, who survived the genocide, visited Babi Yar after 1945. The commemoration ceremony was held on Provody Day (a Ukrainian Orthodox religious holiday for commemoration of dead people). According to Roma tradition, a funeral wreath of flowers was left at Babi Yar and a commemoration dinner was arranged. Due public silence and the absence of a memorial, the tragedy was remembered only on a family level, inside local Romani circles (interview with Raisa Nabarchuk 2012). The Roma had very little possibility of carrying out their memory practices in public. The authorities have not regarded Babi Yar as a site for remembrance and have forced all involved actors to follow this decision. Without having a public space, the memory of genocide existed only in private family circles of the Roma community. According to Michael Stewart the situation of “remembering without commemoration” was typical at that time for Roma genocide survivors across Europe (Stewart Reference Stewart2004). Unlike the Jews, the Roma of Ukraine lacked a rich cultural landscape. Therefore, the Jewish Holocaust was commemorated not only at mass graves, but also through deserted synagogues, former ghettos and cemeteries. The Roma, who mainly had a vagrant way of life prior to the war, do not have any of these. The remaining mass graves constitute the only physical space of remembrance of the Roma genocide.

Politics of Liberalisation and New Trends in Memory Narratives and Practices

During the Khrushchev thaw, new interpretations regarding the significance of civilian victims of the Nazi occupation developed in the Soviet Union. In 1960, the Piskarevo Memorial Complex was opened in Leningrad devoted to “The Victims of Siege during the Great Patriotic War.” In 1965, a large memorial “To the Victims of Fascism” was opened in Ukrainian Donetsk. In 1969, the Memorial Complex Khatyn’ was completed in Belarus, on the site of a former village where the Slavic population was fully exterminated by the Nazis (Rudling Reference Rudling2012; Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk2013). A focus on civilian victims created opportunities for including the memory of Roma and Jewish genocides into the major memory narrative of the Nazi occupation. On the 20th anniversary of the tragedy, in September 1961, Yevgeny Yevtushenko published an epic titled “Babi Yar” in Literaturnaya gazeta, the leading newspaper of the Union of Soviet Writers. The poem, whose first line is “over Babi Yar there are no monuments” led to a strong public support to recognize Babi Yar as a site of Jewish genocide (Gitelman Reference Gitelman and Gitelman1997, 20). Nikita Khrushchev, the party leader of the Soviet Union and former head of the ChGK commission in Kyiv had to meet the writers in order to explain the “errors” of Yevtushenko’s epic. For the first time, the political leader recognized in the public sphere that both Roma and Jews were a primary target of Hitler’s extermination war, but he denied the exceptional nature of the Roma and Jewish genocides:

Let’s take the case of Babi Yar. When I worked in Ukraine, I visited Babi Yar. Many people were murdered there. But comrades, Comrade Yevtushenko, you have to know that not only Jews died there, there were many others. Hitler exterminated Jews, exterminated Gypsies, but his next plan was to exterminate the Slavic peoples, we know that he also exterminated many Slavs. If we now calculate arithmetically, how many exterminated peoples were Jews and how many Slavs, those who state that it was anti-Semitic [war] would see that there were more Slavs exterminated than Jews. It’s correct. So why should we put special attention to this question and contribute to hatred between peoples? What aims have those who raise such question? Why? I think this is completely wrong. (Khrushchev Reference Khrushchev2009, 2, 547)

Pravda published a report from the meeting which stressed that:

According to Comrade Khrushchev, the author of the poem [Yevtushenko] showed an ignorance of historical facts, he believes that the victims of Nazi atrocities were only the Jews, in fact there [in Babi Yar] were murdered many Russians, Ukrainians and other Soviet people of various nationalities. (“Rech’ tovarishcha N. S. Khrushcheva,” Pravda, March 10, 1963)

As we see, the text of the speech at the meeting has been censored afterwards. The Roma have been excluded from the list of victims and the genocide of Jews was played down. According to the official narrative, the victims of genocide suffered under the Nazi occupation just like other people of various nationalities in the Soviet Union.

In 1956, Khrushchev and the Soviet government took the initiative to introduce a criminal prosecution of vagabond Romani. According to the edict On Engagement in Work of Nomadic Gypsies the police had an obligation to stop all travelling Roma and to compel them to settle down. The local authorities had to provide Roma with temporary housing and work, and most itinerary Romani in Ukraine settled down. As a result, many genocide mass graves lost the personal and emotional link between relatives and victims. The representatives of local Roma communities that settled down near many of the genocide sites knew nothing about the murdered Roma. The situation was different for Jewish communities since most of the genocide mass graves were commemorated by local genocide survivors (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk, Andersen and Tornqvist-Plewa2016c). The site of Babi Yar was an exception due to the existence of a local community of settled Roma, represented by first and second generations of genocide survivors who continuously visited Babi Yar after 1956 (interview with Raisa Nabaranchuk; interview with Tatiana Demina).

In 1966 Anatoly Kuznetsov published a documentary novel about the Babi Yar massacre. Kuznetsov grew up in Kurenivka in the vicinity of Babi Yar, and survived the occupation in Kyiv. The novel describes personal experience of the Nazi occupation focusing on the massacre of Jews, but also mentioned the mass killings of Roma. The novel was printed first as a journal publication in 2 million copies (Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov1966). In 1967, the novel was published as a book in 150,000 copies by Komsomol printing house (Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov1967b). The censors cut the manuscript down by a quarter of its original text and removed all mention about the local collaboration with the Nazis, as well as anti-Semitic attitudes of Slavic neighbours (Blium Reference Blium1996, 133–34). It should be noted that a fragment concerning the mass killings of Roma remained in the Soviet edition. The book was translated into English in 1967 and published in non-censored content in the USA (Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov1967a). For the first time, Soviet and international readers learnt about the mass killings of Roma at Babi Yar:

The fascists hunted Gypsies as if they were game. I have never come across anything official concerning this, yet in the Ukraine the Gypsies were subject to the same immediate extermination as the Jews … Whole tribes of Gypsies were taken to Babi Yar, and they did not seem to know what was happening to them until the last minute. (Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov1967a, 100)

Despite having been published by Komsomol printing house, the novel was highly criticized by Izvestia, the official newspaper of Soviet government (Troitskii “Po stranitsam zhurnalov,” Izvestiia, January 20, Reference Troitskii1967). Kuznetsov defected from the Soviet Union in 1968, and the book was confiscated from the libraries. Nevertheless, the novel became the first single public testimony on the mass killing of Roma at Babi Yar. In 1968, an international journal for Romani studies published a review on Kuznetsov’s novel, written by Angus Fraser, with special attention to the fate of the Romani at Babi Yar (Fraser Reference Fraser1968). In 1968, Grattan Puxon, a British Traveller-Gypsy activist and Dr. Donald Kenrick, a prominent linguist, completed the first-ever research project on the Nazi genocide of the Roma, supported by the Institute of Contemporary History at the Wiener Holocaust Library in London. The authors referred to Kuznetsov and noted that “an unknown number of Gypsies were murdered with the Jews at Babi Yar” (Kenrick and Puxon Reference Kenrick and Puxon1968, 149–152). This information was repeated in their ground-breaking book on the Roma genocide, The Destiny of Europe’s Gypsies (Reference Kenrick and Puxon1972).

On September 29, 1966, on the 25th anniversary of the tragedy, an unauthorized rally was held for the first time at Babi Yar. The participants demanded the recognition of the Jewish genocide and the construction of a monument (Nakhmanovich Reference Nakhmanovich2006). The rally was attended by hundreds of people, among them Holocaust survivors, Jewish activists, writers, film makers, and dissidents of Jewish, Russian, and Ukrainian origin. The extermination of Roma in Babi Yar was not mentioned by any of the speakers (“Babi Yar-1966: kak eto bylo,” Maidan, September 28, 2006). The same year, a feature film Those Who’ll Return Shall Love to the End was shot in Kyiv by Leonid Osyka. The central scene of the film is the mass killing of a Gypsy caravan by the Nazis (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk, Friedman and Jacob2016a). At the end of 1966, a simple foundation stone was put up in Babi Yar with the inscription, “A monument will be erected here to honour the Soviet people – victims of fascist crimes in the period of temporary occupation in Kiev in 1941–1943.” Finally, in 1976 the Soviet memorial was erected at Babi Yar (see figure 3). The initiators discouraged placing any emphasis on ethnic aspects of the tragedy. Instead a typical soldier monument was constructed with the inscription, “Soviet citizens, POWs, soldiers and officers of the Red Army, were shot here in Babi Yar by German Fascists” (Evstafieva Reference Evstafieva, Evstafieva and Nakhmanovich2004, 187–206). The construction of a memorial 35 years after the tragedy was presented as a great achievement of memory politics (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk2014, 34–36). The civilian victims were defined by officials as “peaceful citizens of Ukrainian, Jewish, Belarusian and Polish descent” (Odinets“Monument u Bab’ego Yara,” Pravda, June 23, Reference Odinets1976). The Roma victims were not mentioned. An interview with Chief Architect Anatoly Ignashchenko illustrates the main line of the official narrative of Babi Yar, with a strong focus on heroes and combatants: “The memorial is intended as a sculptural requiem to strong-minded people – mariners of Dnepr River Navy, the defenders of Kyiv, underground fighters, the POWs, but also peaceful citizens, women, elderly, children” (Tsikora “Monument zhertvam fashizma,” Izvestiia, July 2, Reference Tsikora1976). Despite the silence concerning the Roma victims, the 1976 memorial legitimized memory practices of local Romani. The first and second generations of genocide survivors started to visit the monument on Victory Day and Memorial Day, the 29th of September (see figure 4). They brought flowers and photos of murdered relatives to the monument (interview with Raisa Nabarchuk). However, due to the lack of an educated strata within Romani community, efforts for public recognition and memorialization of the genocide were problematic. The only known attempt was made in 1968 in Moscow. The artists at the State Theatre Romen sent a collective petition to the regional authorities in Smolensk asking for permission to erect a monument on the site of the mass extermination of the gypsy village Aleksandrovka (Holler Reference Holler2009, 263–79). The answer was negative, despite the existence of the official print Mass killing of Romani by the Nazis near Smolensk (“Rasstrel nemtsami tsygan bliz Smolenska” 1945) presented by the actors of memory as a legal point for the erection of monument.

Figure 3. The Soviet memorial at Babi Yar opened in 1976. Photo by Andrej Kotljarchuk.

Figure 4. Roma genocide survivors at Baby Yar Memorial. On the left: Parania Startseva, on the right: Boris Startsev. Kyiv, 1976. Private collection of Natalia Zinevych.

Democratisation of Soviet society during the perestroika opened closed public “floodgates” of memory of the Roma genocide. In 1985, the theatre Romen prepared a spectacle Birds need the Sky performed in Moscow, Kyiv, and other large cities, dedicated to Roma genocide victims (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk, Friedman and Jacob2016a). The review of the performance was the first detailed account of the Nazi genocide of Roma published in the Soviet Union after 1945 (Kishchik Reference Kishchik1985). In 1989, a metal plaque was placed at the Babi Yar monument in Hebrew symbolizing the conversion of Babi Yar from a typical memorial of the Great Patriotic War to a Holocaust site. The first testimonies of the Jewish tragedy were published already during World War II. After the war the Jewish memory actors made a lot of public efforts for recognition of Babi Yar as the site of genocide (Mankoff Reference Mankoff2004; Lustiger Reference Lustiger2008, 122–124). The first list of Jewish victims of Babi Yar with more than 7000 names and several personal biographies was collected and printed during the Soviet time (Zaslavskii Reference Zaslavskii1991). The attempts of Roma memory actors were not so successful. In 1989, the first memorial on the site of the Roma genocide was opened at the village of Aleksandrovka near Smolensk. However, the 1989 monument presented victims as the Soviet peaceful citizens without specifying their ethnicity. It was not until 2019 that the first Roma genocide memorial was erected in Russia, three years after the Roma genocide memorial in Kyiv. The new memorial erected at Aleksandrovka is the first Roma genocide monument in the post-Soviet countries where the names of the victims are written. However, the list of the victims is not comprehensive. The commemoration of the Roma genocide in the post-Soviet Ukraine faced several obstacles related to the dependency on past history, like the poor documentation and the de-personification of the victims. A key challenge for the commemoration of the Roma tragedy of Babi Yar was the lack of names and personal biographies of both genocide victims and survivors. This highlights the main difference between the ongoing commemoration of the Holocaust and the Nazi genocide of Roma in Ukraine. Due to the collective protests and efforts of Jewish intelligentsia, the Jewish trauma of Babi Yar was accepted, to some extent, by the Soviet government; and recognized in 1989–1991. The official recognition of the Roma genocide was a long-term process that took decades after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Babi Yar and the Commemoration of the Roma Genocide in Contemporary Ukraine

After 1989, the significance of the Holocaust underwent a substantial change and the Jewish memorial Menorah was opened at Babi Yar on the 50th anniversary of the tragedy. Two new editions of the list of Jewish victims of Babi Yar were prepared and published, which contain more than 14,000 names and several personal testimonies (Shlaen Reference Shlaen and Malitskaya1995; Levitas Reference Levitas2005). Only two names of Roma victims have been identified for the same period of time (The Babi Yar Public Committee Database 2019). However, even two names have a great symbolic value for actors of memory in their efforts for public recognition of the Roma genocide. An initiative to erect a Roma genocide monument at Babi Yar was taken in 1995 by Anatoly Ignashchenko, the former chief architect of Soviet memorial. Ignashchenko discussed the design of the Roma genocide monument with Roma activists Mikha Kozimirenko and Volodymyr Zolotarenko (Yarmoluk “Kvitok do Romanistana,” Den’, May 30, Reference Yarmoluk1998; Zinchenko “Baron i kosmos,” Aratta, February 17, Reference Zinchenko2009). Kozimirenko was a genocide survivor and poet who published a poem “Babi Yar” devoted to Roma victims in which he protested against unmarked mass graves and the absence of a memorial. The monument, which was sponsored by different non-governmental organizations, was completed in 1996. It represents a life-size gypsy wagon made of wrought iron with bullet holes through it. Due to his knowledge of Romani memory practices at Babi Yar, Ignashchenko came up with a solution to overcome the de-personification of victims. He attached to the tent several photo frames in which relatives are encouraged to insert photos of murdered relatives (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk2014, 45). The inscription was made both in Ukrainian and Romani and was devoted “To the memory of Roma exterminated by the Nazis in 1940–1945. We remember!” The idea of the monument was inspired by the film A Roma directed by Alexander Blank and based on the novel written by Anatoly Kalinin. The film tells a story of a Red Army veteran and a gypsy baron Budulai who travelled with a caravan through the Soviet Union searching for his family who were killed by the Nazis, and their wagon that was lost in the war (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk, Friedman and Jacob2016a). However, when the monument was ready to be placed in Babi Yar the city authorities stopped the erection of the monument (interview with Tatiana Demina). What exactly it was that prevented the proposed monument is unknown. Ignashchenko had to donate the monument to the town of Kamyanets-Podilsky.

On Memorial Day, September 29, 1999, a simple stone foundation was erected in Babi Yar at the expense of different Roma non-governmental organizations. This time the city authorities sanctioned the erection of the stone. The setting up of the monument led to new memory practices. On the International Roma Day (April 8), activists and representatives of the Roma community started to arrange an annual ceremony at the foundation stone. They placed flowers and installed three flags behind the monument: those of the national Roma, Ukrainian, and European Union. The actors of memory used a public ceremony to share awareness about the Roma history and collective trauma with visitors of Babi Yar as well as through publication about the event in the press.

The 2005 resolution of the Ukrainian Rada, On the International Day of the Roma Holocaust, gave an impetus to further memorialization of the Roma genocide. The parliament instructed local authorities “to identify mass graves and commemorate deported and executed members of the Roma national minority” (“Resolution” 2005). The address of President Viktor Yushchenko on the occasion of the International Day of the Roma Holocaust, which was issued on August 2, 2009, marks a new line in the major narrative of World War II in Ukraine. For the first time, the political leader of the country devoted a statement to the Roma genocide. The president argued for including the Roma genocide into a national memory narrative of World War II. He stressed the exceptional nature of the Nazi extermination of Romani people and called for active participation of authorities and civil society in the commemoration of the Roma genocide (Yushchenko Reference Yushchenko2009, 11–12).

In 2011, some weeks before the International Roma Holocaust Memorial Day, the foundation stone at Babi Yar was totally destroyed by unknown vandals. The Roma Congress of Ukraine sent an open letter of protest to Prime Minister Mykola Azarov, who was the chair of the Committee for the 70th anniversary of Babi Yar. The Congress called for an end to “discrimination of their memory by the state” and required inclusion of Romani representatives in the Committee and constant dialogue between Roma and government regarding the construction of a Roma genocide memorial in Babi Yar (“Romi vimahaut′ vid Azarova vshanuvaty i ikhni Holocaust,” Ukrains’ka Pravda, July 13, 2011). The protest letter led to the erection of a new memorial stone at Babi Yar, this time funded by the state. A new inscription appeared: “In memory of Romani, who were shot in Babi Yar” (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk2014, 46). The reaction of the Romani community to a new monument was negative. They believed that the inscription meant that the state had constructed a final memorial at Babi Yar. The Roma non-governmental organizations protested and stressed the fact that the Roma people have been waiting almost twenty-five years for a memorial in Babi Yar, while about twenty other memorials have been built (interview with Raisa Nabarchuk).

In 2012, the Ukrainian government approved the concept of the National Historical Memorial Preserve in Babi Yar, which includes the building of a Roma memorial and commemoration of the genocide. In cooperation with the Roma, the National Preserve organized a public ceremony on August 2 dedicated to the Roma Holocaust Memorial Day (Babyn Yar National Historical Memorial Preserve 2019). The public ceremony of the Roma genocide at Babi Yar on August 2 marks the commencement of new memory practices.Footnote 8 Since 2012, a public ceremony on August 2 in Babi Yar unites the Ukrainian Roma, Roma activists from other European countries, authorities, and the general public (see figure 5).

Figure 5. Romani from Kyiv at the foundation stone in Babi Yar on the European Roma Holocaust Memorial Day, 2012. Photo by Andrej Kotljarchuk.

In 2016, Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman, the head of the Organising Committee for Preparation of the 75-year Commemoration of Babyn Yar, announced the opening of the Roma genocide memorial at Babi Yar (Organising Committee 2016). The gypsy wagon designed by Ignashchenko that had been rejected as a memorial in Kyiv has been renovated and transferred back to the city and erected in September 2016 at Babi Yar, near a Soviet memorial (see figure 6). The opening of a memorial in Babi Yar symbolizes the inclusion of the memory of the Roma genocide into the national narrative of World War II. In 2016, information panels about the Nazi genocide of Roma were installed at Babi Yar; however, very little information and photo material on these panels were dedicated to the local victims.

Figure 6. Genocide survivor Raisa Nabarchuk at the Roma Memorial in Babi Yar. 2017. Photo by Natalia Zinevych.

In September 2016, President Petro Poroshenko announced the building of a new museum and central memorial in Babi Yar that will be completed in 2023. The project is financed by an International Foundation established by oligarchs of Jewish descent from Russia and Ukraine (Zisels Reference Zisels2017). On behalf of the government, the Institute of History at Ukrainian Academy of Sciences developed The Concept of the Museum and Memorial Centre at Babi Yar that was published online in 2018 (hereafter the Concept). The research team of Ukrainian historians led by professor Hennady Boriak describes the future memorial and museum as a reunified site of commemoration for all victims of Nazism in Ukraine (Kontseptsiya 2018). The authors avoid speaking about the Roma as victims of genocide. The term Holocaust is used in the Concept only regarding the Jews. The authors ignore the facts that in many European countries the Roma genocide is included in the concept of Holocaust and the European Parliament calls August 2 The European Roma Holocaust Memorial Day (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk and Geverts2020). The Concept tends to glorify the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) presenting them as any other victims of Nazism (Kontseptsiya 2018, 51–53). This is problematic due to the collaboration of many nationalist leaders with the Nazis (Burakovskiy Reference Burakovskiy2011; Oldberg Reference Oldberg2011; Rossolinski-Liebe Reference Rossolinski-Liebe2012; Rudling Reference Rudling2016). The authors of the Concept are critical of the idea of dedicating a central memorial to the Jewish Holocaust and name this point of view “an incorrect vision, which is popular in Jewish, Western, Liberal-Russian, and other post-Soviet circles” (Kontseptsiya 2018, 5). The state-run concept of a new memorial and museum at Babi Yar and the use of the memorial for utilitarian political goals of Ukrainian leadership have sparked a very wary reaction from the Jewish diaspora (Briman Reference Briman2020).

The alternative project of a future memorial and museum is presented by the non-governmental Holocaust Memorial Centre, which is an academic section of the International Foundation Babyn Yar. The authors see a future memorial and museum as, first of all, a site of the Jewish Holocaust. This vision is supported by international Advisory Scientific Council represented by international and Ukrainian researchers within Holocaust studies (Scientific Council 2019). In November 2018, the Scientific Council led by Karel C. Berkhoff presented The Basic Historical Narrative of the Holocaust Memorial Centre Babyn Yar (hereafter The Basic Narrative, see Berkhoff Reference Berkhoff2018). The Basic Narrative has a section about the mass extermination of Roma in Kyiv (Berkhoff Reference Berkhoff2018, 224–230). However, the authors argued for exclusion of the Roma genocide from the term of Holocaust (Berkhoff Reference Berkhoff2018, 12–13, 225). It is known that many international researchers of the Jewish Holocaust rejected the claim that what had happened to the Roma during World War II could be termed Holocaust (Gaunt Reference Gaunt2016). A large part of the content of the Basic Narrative is devoted to the collaboration of local auxiliary police and many nationalists with the Nazis and their participation in the Holocaust (Berkhoff Reference Berkhoff2018, 58–95). Therefore, the authors argued for the exclusion of Ukrainian nationalists murdered by the Nazis in Kyiv from the memory narrative of victims of Babi Yar.

The existence of two alternative academic projects led to public debates. On one side, Oleksandr Kruglov, member of the Scientific Council and renowned researcher of the Nazi occupation in Ukraine, criticized the Concept of the Institute of History and argued that Babi Yar is a symbol of a Jewish catastrophe (Kruglov Reference Kruglov2019). On another side, Vitaly Nakhmanovich, renowned historian of Babi Yar, argued against the Basic Narrative pointing it out as a private project sponsored by oligarchs with focus on the Jewish Holocaust only. He believes that the national memorial and museum should be designed and constructed by the state-run agency, not by private actors (Nakhmanovich Reference Nakhmanovich2020). In an open letter signed by the authors of the Concept, they warn for plans of “privatisation of memory” by the International Foundation and call the Basic Narrative a “wrong attempt to link the site of Babi Yar with the history of Holocaust only, ignoring other victims and other dramatic moments of our past” (List-zasterezhennia 2017). The Basic Narrative has also been criticized by the Institute of National Remembrance – a central executive body operating under the government of Ukraine. Using conspiracy rhetoric, Volodymyr Viatrovych, then Director of the Institute, blamed the Holocaust Memorial Centre for having a “Russian connection” and accused the authors of the Basic Narrative of denial of the symbolic value of Babi Yar as an all-national pantheon remembering the Nazi occupation (Viatrovych Reference Viatrovych2019). The ongoing public debates over the future memorial and museum in Babi Yar could be interpreted in the terms of academic wars of memory. Neither the Concept nor the Basic Narrative are against the memory of Roma genocide. However, the Basic Narrative tended to see Romani as victims of a second-rate genocide and the Concept mentioned Romani among a long list of different groups of victims, together with Ukrainian nationalists.

The process of democratization in Ukraine, that started in the end of the 1980s and accelerated after the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, led to the consensus between various non-governmental and governmental actors to commemorate the Roma genocide. Ukraine is an exception in the intensification of memorialisation of the Roma genocide. About twenty Roma genocide memorials were erected in Ukraine during the last decade, compared with other post-Soviet states. Three Roma genocide memorials were erected in neighbouring Belarus, one in Russia, one in Estonia, one in Latvia, and two in Lithuania. The Memorial at Babi Yar became a central site for public commemoration of the Roma genocide in Ukraine. The memorial is visited regularly by various official and non-governmental delegations (My nikogda ne zabudem 2019). New memorials constructed in the countryside are often motivated by the existence of Roma memorials in the capital (Official News Portal of Sumy Region 2016). New genocide memorials have been erected in both western and eastern parts of Ukraine and memory work on the Roma genocide is supported in Ukraine by most of the parliamentary parties (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk, Andersen and Tornqvist-Plewa2016c). The previous studies show significant regional and political differences concerning memory narratives of World War II in contemporary Ukraine (Jilge Reference Jilge2006, Reference Jilge, Barkan, Cole and Struve2007; Katchanovsky Reference Katchanovsky2014, Plokhy Reference Plokhy, Fedor, Kangaspuro, Lassila and Zhurzhenko2017). The Nazi genocide of Roma is an exception here, due to the absence of essential regional and political differences in the ongoing process of commemoration. For the Ukrainian political left (Communist Party of Ukraine, which was banned in 2015, Party of Regions, and Opposition Platform – For Life), the Roma genocide is an example of cruelty inflicted by the Nazi regime that was defeated by the Red army. For ultranationalists, represented by the members of The All-Ukrainian Union Svoboda and other political organisations, this is a tool to downplay the Jewish Holocaust and to include the leaders of OUN into a national gallery of the victims of Nazism. As Yulia Yurchuk points out “at the level of national memory, the legacy of the OUN and UPA will surely continue to present grounds for disputes and discontent” (Yurchuk Reference Yurchuk, Fedor, Kangaspuro, Lassila and Zhurzhenko2017, 131). Another factor behind the inclusion of the memory of the Roma genocide into the major narrative of World War II is the integration of Ukraine into the European Union. The European Union regards commemoration of the Roma genocide as a tool for integrating the Romani minority into the major society (Baar Reference Baar2011). The European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) continuously monitors implementation of the 2005 resolution about memorialisation of the Roma genocide (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk, Andersen and Tornqvist-Plewa2016c). A principal actor in remembering the Roma genocide in Ukraine is a non-governmental Centre for Holocaust Studies in Kyiv. Academic and educational programmes on the Roma genocide are arranged by the Centre and are led by Mikhail Tyaglyy. There is no such institution in neighbouring Russia or Belarus. The Centre for Holocaust Studies organizes seminars and training for schoolteachers and others on the history and memory of the Roma genocide and cooperates with Roma activists and genocide survivors (Tyaglyy Reference Tyaglyy2013). In October 2019, at the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in World War II, the Centre opened one of the first exhibitions of the Roma genocide called The Neglected Genocide (“Vistavka Znevazhenii genocide” 2019). The cooperation of Romani representatives and academic scholars is the next factor behind the inclusion of the memory of the Roma genocide into the major memory narrative. As David Gaunt pointed out:

Bringing together Romani representatives and genocide scholars had been possible through two intellectual trajectories. One approach emerged from the growing insight among historians that memory, previously shunned, could enrich and deepen historical narrative based on archival sources… . Another, completely different, trend grew out of the Roma side, reacting to the fact that scholars who were not Roma dominated Romani studies, with an increasing demand to participate in research on all levels. The slogan ‘Nothing about us without us’, long expressed only informally, has now been formalized by leading Roma human rights activists.” (Gaunt Reference Gaunt2016, 38)

Conclusion

In the study of the commemoration of the Roma and Jewish genocides in Germany, Nadine Blumer analysed debates about the representation of the past at a Holocaust memorial in Berlin. Her research examined how the very idea of the Roma and Sinti genocide memorial arose as a response to the proposal to build a central, reunified memorial devoted to the Holocaust, and how this idea fell out of favour due to the competing interests of various memory actors (Blumer Reference Blumer and Weiss-Wendt2013). The case of Babi Yar is similar. The idea to build a new central memorial, devoted to all groups of victims, seems to be problematic due to competition between various memory actors with different visions of the past and for the content of future memorials and museums.

Slawomir Kapralski argues that the issue of the memory of the Roma genocide depends on changing dynamics of perceptions and memory practices, which are influenced by the development of the Roma genocide discourse and transformation of the past into a symbolic value of modern Romani identity (Kapralsky Reference Kapralski and Weiss-Wendt2013). As he has noted “through commemoration of the genocide, the Roma people focus on their common past in order to create a better future” (Kapralsky Reference Kapralski2012). Our study confirms this thesis. The revising of Soviet narratives of World War II in Ukraine opened possibilities for inclusion of the collective memory of the Roma people into the major narratives of World War II. As Andrii Portnov pointed out, the general memory narrative of World War II in Ukraine switched from the memory of heroes to the memory of the suffering of ordinary people (Portnov Reference Portnov2007). The political consensus between the Romani activists, Ukrainian genocide scholars, and the authorities created possibilities for inclusion of the Roma minor memory of the genocide into the major memory narrative of the Nazi occupation in Ukraine. The main obstacle for commemoration and memory practices of the Roma genocide in Ukraine is poor documentation. The lack of historical knowledge is a great challenge for memory actors who are trying to develop memory practices without a great number of oral testimonies and personal biographies of victims and survivors.

Examination of memory practices of the Roma community in Kyiv shows that they had always commemorated their relatives who were murdered by the Nazis. However, the content and day of commemoration has changed depending on the political context and development of the major narrative. After the war, memory practices relating to genocide victims were limited to family ceremonies on religious holidays inside the Romani community. The politics of liberalisation in the Soviet Union allowed the Roma to legitimate their memory practices and add new content. After 1976, the Roma visited the memorial at Babi Yar on Victory Day (May 9) – a principal Soviet holiday for the commemoration of the Great Patriotic War. After the erection of the first foundation stone in 1999, the Roma activists have moved the main day of commemoration from the 9th of May to International Roma Day (April 8), in order to mobilize the national movement and to share awareness about the Nazi persecution of Romani people. The parliamentary resolution on the Roma genocide and the creation of a National Preserve, as well as the process of integration of Ukraine into the European Union, led to the formation of new memory practices. For the first time, the authorities have been involved in the planning of the commemoration ceremonies. The day of commemoration has been moved again, this time, to International Roma Holocaust Memorial Day (2 August). The opening of a national memorial at Babi Yar in 2016 symbolizes the final inclusion of the memory of the Roma genocide into the major narrative of World War II. The positive decisions regarding the erection of the Roma genocide memorial at Babi Yar were taken by different presidents of Ukraine, belonging to different political parties. The construction of genocide memorials in Ukraine was supported by various political organisations, from the Communist Party of Ukraine to the nationalist Cossack associations (Kotljarchuk Reference Kotljarchuk, Andersen and Tornqvist-Plewa2016c).

The major narratives of World War II in Ukraine shaped and reshaped the memory and memory practices of the Roma genocide in the exchange and connection between different memory actors in a changing political context. The gradual entry of the memory of the Roma genocide into the major narrative of World War II could be explained by many factors: the switch of focus from the heroic soldiers of the Red army to the suffering of ordinary Ukrainian people, the democratisation process, and the integration of the country with the European Union. Today in Ukraine, the memory of the Nazi genocide is a key element of the Roma national movement and memory practices.

Disclosure

Author has nothing to disclose.

Financial Support

The Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies, 38/2015_OSS