Introduction

Education plays a key role in reproducing both social inequalities and group identities and is central to understanding minority policy regimes. Despite its importance, however, no systematic comparative analysis of Central and Eastern European cases has been conducted.Footnote 1 Our study takes a step in this direction, providing a framework for comparative inquiry and four illustrative case studies: Turks in Bulgaria, Russian speakers in Estonia, Albanians in the Republic of North Macedonia, and Hungarians in Romania. Our main focus is on how different models of minority education produce inequalities between majorities and linguistic minorities and how education shapes systems of ethnic stratification and the well-being of minorities. Although empirically oriented, our article is also of normative interest and can be useful for scholars and practitioners engaged in minority rights advocacy and monitoring processes of international conventions and multilateral treaties.Footnote 2

In our understanding, educational equity, the key term of our analytical framework, has a dual meaning. On the one hand, in line with the literature of international student assessment (PISA - Programme for International Student Assessment, TIMSS - Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, PIRLS - Progress in International Reading Literacy Study), we focus on distributive aspects and cross-group differences of individual opportunities of social mobility. From this angle, equity “does not mean that all students have equal outcomes; rather, it means that whatever variations there may be in education outcomes, they are not related to students’ background, including socio-economic status, gender or immigrant” (OECD 2019, 15). Although this literature rarely focuses on language,Footnote 3 few would explicitly deny that linguistic minorities also desire equal opportunities of individual social mobility. On the other hand, however, educational equity is also connected to cultural recognition.Footnote 4 Linguistic background and cultural staff associated with minority groups are rooted in earliest socialization (May Reference May2008, 43–48) and can be perceived as part of one’s habitus in the sense employed by Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1990). Through the term habitus, Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1990, 63) emphasizes that members of social groups acquire enduring and embodied dispositions that cannot be changed easily. If the educational system exclusively values the habitus of the dominant group (in this case, the language and cultural staff of the majority), this will inevitably lead to the reproduction of the existing structure of dominance. Minorities might certainly adapt to the linguistic and cultural habitus of the majority, but this is a costly and time-consuming process and an educational system that denies the special educational needs of minorities and externalizes unilaterally costs of cultural adaptation to minority groups cannot be perceived as equitable (Tollefson and Tsui Reference Tollefson and Tsui2017).

To construct our analytical framework, we turn to literature on minority rights and diversity management. While minority rights research aims to define standards in minority protection and investigates how realities deviate from those standards, diversity management, minority policy regimes, as well as minority protection are broader terms that embrace a larger set of legal, political, and social rules. Ultimately, they refer to the institutional order of the state and the ideologies and discourses governing intergroup relations. Interestingly, both approaches focus more often on the role of minority education in identity reproduction than on its importance in providing equity for minority students. Moreover, it is widely assumed that a trade-off exists between the requirements of equity and the preservation of minority identities (Laitin and Reich Reference Laitin, Reich, Kymlicka and Patten2003; Ringelheim Reference Ringelheim2011). Influential legal scholars emphasize the distinction between “substantive equality” and the right to identity as two “foundational principles” of minority protection (Henrard Reference Henrard2009). We argue that these dimensions should be studied in a framework that recognizes their mutually constitutive relationship. Substantive equality, as a just outcome of distributive processes, cannot be achieved by individuals on their own without institutions that protect their rights to preserve and develop their cultural identity or, at least, recognize their special culturally and linguistically rooted needs. Thus, in our framework, the distinction between these aspects is only analytical.

Another important aspect of the proposed framework is that it analyses minority education as part of larger institutional settings that shape intergroup relations in different states. To conceptualize different macro-approaches, we define a fourfold typology comprising accommodation, integration, assimilation and ethnic hegemony. We first discuss these ideal typical macro-models, and then we outline the educational policies they tend to be coupled with.

Our article is not purely conceptual, but, next to proposing a framework for comparative analysis, it also provides four illustrative case studies in Central and Eastern Europe. The empirical part of our article does not rely on the usual comparative methodology, but it aims to illustrate the usefulness of the analytical framework in investigating to what extent educational policies under different macro-approaches are conducive to educational equity and, ultimately, to minority well-being. Case selection was limited to Central and Eastern Europe, but next to trying to cover all of the macro-models, we included countries from different subregions, from the ex-Yugoslav space to the Baltics. The selected countries inherited different legislative and institutional designs of minority policies from state socialism and experienced different challenges of state- and nation-building and regional security threats during the post-socialist period (Csergő et al. Reference Csergo, Kallas and Kiss2025). Although we do not provide an exhaustive historical institutional analysis in this article (see Pierson Reference Pierson2000; Thelen Reference Thelen1999), we employ a diachronic perspective in order to identify major shifts, as well as gradual changes of educational policies.

Our focus on the relation between models of minority policy and educational equity necessitates a holistic approach combining the review of national-level educational legislation with statistical analysis. While diachronic legal analysis helps to show to what extent positive minority rights concerning the language of education, curriculum content, institutional settings, decision-making (Thornberry Reference Thornberry and Weller2007) are characteristic and promote group reproduction, it is less useful in investigating educational equity. The quest for equity (or substantive equality) is strongly connected to the universalist language of individual right and to what legal scholars regard as the “first pillar” (Henrard Reference Henrard2009) of minority protection, offering “uniform solutions” (Alfredsson Reference Alfredsson, Caruso and Hofmann2015), or “negative freedoms” (Arzoz Reference Arzoz2007), protecting minorities against discrimination, certain forms of forced assimilation and providing a regime of linguistic and cultural tolerance. As Central and Eastern European states legally protect individual rights and are constitutionally committed to combat discrimination, discriminative elements rarely figure openly in educational legislation. Thus, instead of de jure (direct and legally codified forms of) discrimination, we focus on structural-institutional processes and de facto discrimination. This is connected to a more “groupist” approach of anti-discrimination focusing on cross-group differences of the outcomes of distributive processes (for example, educational equity and substantive equality) (Ringelheim Reference Ringelheim2011). To investigate this aspect, we use the 2022 PISA assessment database as an obvious but underutilized source in the comparative investigation of equity in minority education.

Toward a Comparative Framework of Minority Education

Macro-approaches to minority policies

Until recently, most important normative debates in the field referred to possible options of diversity management in liberal democracies. In such states, individual rights are legally protected, while the question of whether and how the state should support institutions that reproduce diverse group identities is a matter of political contestation and policy choice. Thus, debates tended to revolve around dichotomies such as majoritarian democracy versus consociation (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977), politics of universalism versus politics of difference (Taylor Reference Taylor and Gutmann1992); civic state versus binational state (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996); universal citizenship versus minority rights (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka1995); unitary citizenship versus multiculturalism (B. Barry Reference Barry2001), integration versus accommodation (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O’Leary, Simeon and Choudhry2008) and civic integration versus multiculturalism (Joppke Reference Joppke2017). Our universe of analysis is not limited to liberal democracies, however, but it also includes states that move toward illiberal and authoritarian directions, as well as to those which, in the context of the rise of extreme right populism and securitization of international environment (Csergő et al. Reference Csergo, Kallas and Kiss2025), started to employ more repressive policies relying on the dominance of the core group over minorities. According to McGarry (Reference McGarry2024, 1), these states usually deny ethnic dominance and, in order to gain international and internal legitimacy, produce narratives that depict their model of diversity management as being either accommodative or integrative. The latter narrative, or as McGarry (Reference McGarry2024, 5–8) calls it, “domination under integrationist guises,” is of particular interest to us. European transnational organizations rely increasingly on integrationist rhetoric (see OSCE 2023), and, thus, it is not surprising that in a growing number of Central and Eastern European states references to equal citizenship, ethnic blindness and civic nationalism are used to mask regimes of ethnic domination.

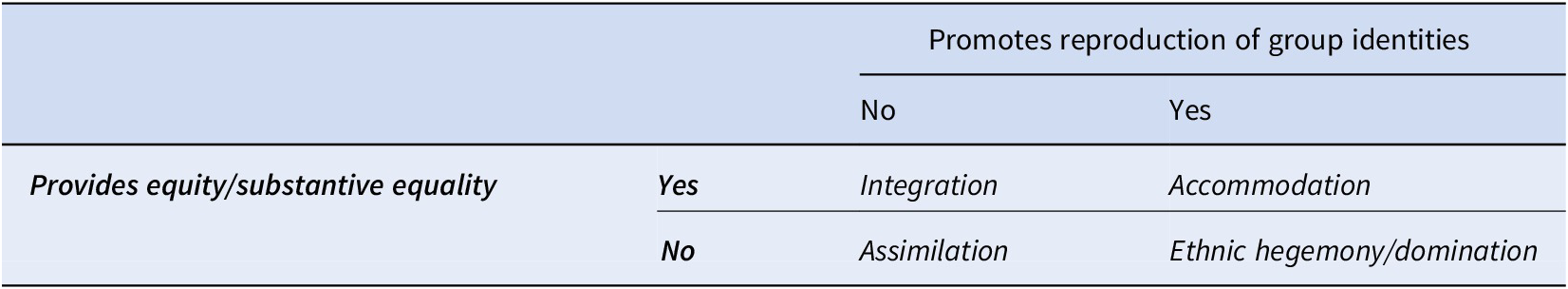

Our framework distinguishes between minority policy regimes along two axes, namely, whether states provide equity/substantive equality for minority group members and whether they promote the reproduction of group identities. As a simple bivariate distinction along these two axes,Footnote 5 one can define the four macro-models mentioned earlier (Table 1). We discuss these models first, and then, in the upcoming section, we outline the educational policies they tend to be coupled with.

Table 1. Macro approaches to minority policies

Disestablishment or neutrality (blindness) of cultural differences in the private realm is at the heart of the integrationist approach. Indeed, integrationist regimes do not prohibit people from using any language in private conversations or minorities to establish their own privately funded institutions. Nevertheless, public institutions cannot be built entirely on disestablishment, and, thus, states cannot be culturally neutral: public services are provided in specific languages, and public education inevitably promotes certain cultural content. According to Patten (Reference Patten and Choudhry2008, 97–101), these aspects belong to the principle of nation-building, aiming to construct a common political identity, a unitary public sphere, and inclusive state institutions. Indeed, the cultural criteria required for integration should be contested. Republican integrationism, for instance, defines these criteria quite broadly, approaching assimilationism (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O’Leary, Simeon and Choudhry2008), whereas other variants of integrationism relax them. Constitutional patriotism, for instance, pushes for thin/minimalist cultural criteria of integration, including functional knowledge of the state language(s) and the acceptance of basic liberal values (Joppke and Morawska, Reference Joppke and Morawska2003). Moreover, although integrationist regimes do not promote the reproduction and political activation of group identities, they are not incompatible with but arguably necessitate certain forms of cultural recognition. Nancy Fraser (Reference Fraser2000), for instance, argues against the “identity political model” of recognition, this being conducive to separate minority institutions. She proposes the so-called status model of recognition, which is connected to a more integrationist vision aiming to create shared institutional spaces in which minorities and subordinated groups can participate on an equal footing. In her status model, cultural recognition means the eradication (deinstitutionalization) of cultural codes and norms that put minorities in a subordinate position, a process also called destigmatization (Lamont Reference Lamont2018). From this angle, integration necessitates profound transformation of cultural canons and majority-dominated institutions or, at least, mutual adaptation between minorities and majorities (Alba and Foner Reference Alba and Foner2015, 6–8).

Accommodation relies not only on the public recognition of substate ethnic, linguistic, or religious identities but also promotes their reproduction and political activation. While integrationists believe that only shared political identities and common institutions can lead to enduring peace, advocates of accommodation argue that substate political loyalty does not necessarily lead to conflict. Accommodationists consider that politically salient ethnic identities tend to be durable, resilient, and difficult to change. Consequently, existing institutional-political arrangements should provide opportunities for minority groups to publicly express their identities, protect themselves from the majority, and manage their own community issues (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O’Leary, Simeon and Choudhry2008, 51–67). Although not a mainstream model, most of the historically rooted and territorially concentrated minority groups of the Western core (Canada, Finland, Italy, the UK, Belgium, Spain, and Switzerland) are accommodated, while international organizations, although generally supporting integration in the case of violent conflicts, routinely propose accommodation as part of peace resolutions (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka2007; Fontana Reference Fontana2017).

Even if states try to frame their policies as either accommodative or integrative, political elites are still engaged in what Brubaker (Reference Brubaker1996) called “nationalizing projects,” relying on majoritarian “ownership” over state institutions (Wimmer 2019) and majority ethnic domination over minorities (McGarry Reference McGarry2024). Aims of nationalizing policies might be either assimilatory or dissimilatory (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 83–93), the two remaining options in our typology.

Assimilation was and, according to some analysts (Favell Reference Favell2022, 33–48), still is a well-established tool of diversity management in Western liberal democracies, although today not only accommodationists but also many adepts of integration reject (forced) assimilation. When describing assimilation, it is helpful to differentiate it from integration, which was initially introduced in the literature as a “polemical alternative” of it (Joppke and Morawska Reference Joppke and Morawska2003; Alba and Foner Reference Alba and Foner2015). Importantly, assimilatory policies lack the principle of “disestablishment” and foster cultural homogeneity in the private realm, too. Although the distinction between public and private is never clear, in an integrationist regime, laws prohibiting the private use of minority languages or banning private schools in minority languages constitute impermissible state intrusions into one’s privacy, violating the freedom of expression and association of minorities. Furthermore, nation-building in assimilationist terms refers to the unilateral adaptation of minorities to the majoritarian cultural core.Footnote 6

The term of hegemonic control was developed by Lustick (Reference Lustick1979) and called the historically most widespread macro-model of diversity management by McGarry and O’Leary (Reference McGarry, O’Leary, McGarry and O’Leary1993, 23–26) in one of their earlier typologies. Next to hegemonic control, Smooha’s (Reference Smooha2001; Reference Smooha2002) concept of ethnic democracy should also be mentioned here, as both were found relevant for the CEE region, control being used in cases of Estonia (Pattai-Hallik Reference Pettai and Hallik2002), Romania (Medianu Reference Medianu2002; Horváth Reference Horváth2002), and state-socialist Bulgaria (Mahon Reference Mahon1999), with ethnic democracy concerning Estonia (Järve Reference Järve2000), pre-Ohrid Macedonia (Holliday Reference Holliday, Smooha and Järve2005), and Bulgaria (Johnson Reference Johnson2002). We will use ethnic hegemony and domination interchangeably to denote cases where “nationalizing” states do not opt for assimilating minority populations, either because they perceive this impossible or because minorities are considered inferior (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 88). Thus, they do not aim to eliminate diversity but try to prevent the mobilization of the subordinated group and provide privileged access to majority group members to valuable economic and symbolic resources. Such policies often aim at altering the system of ethnic stratification in order to marginalize minorities. From a normative point of view, ethnic hegemony is obviously problematic; nevertheless, it is compatible with a rude, formal-procedural form of majoritarian democracy if those monopolizing the power constitute a demographic majority (McGarry 2024).

The options along the two axes we discussed are not dichotomous but rather continuous; consequently, intermediate categories can also be found. Limited public recognition of group identities can be placed between integration and accommodation, while “republican integration,” with its thicker cultural criteria of integration between assimilation and integration (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O’Leary, Simeon and Choudhry2008, 68). Softer forms of hegemonic control can also turn to accommodation, with Romania’s unequal accommodation (Kiss et al. Reference Kiss, Toró, Székely, Kiss, Székely, Toró, Bárdi and Horváth2018), for instance, being such an intermediate category. In addition, assimilation and hegemonic control are not mutually exclusive policies; nationalizing states often implement both simultaneously.

Minority education under different macro-approaches: A fourfold typology

In the following section, we describe educational policies under the four macro-approaches of minority policy outlined above. Before discussing them, we present briefly Thornberry’s (Reference Thornberry and Weller2007) framework on educational rights.

In line with the more general distinction between the “first and the second pillars” of minority rights protection (for example, universal requirements connected to human rights treaties vs. particular solutions and positive minority rights), Thornberry (Reference Thornberry and Weller2007) distinguishes between two groups of educational rights of minorities.

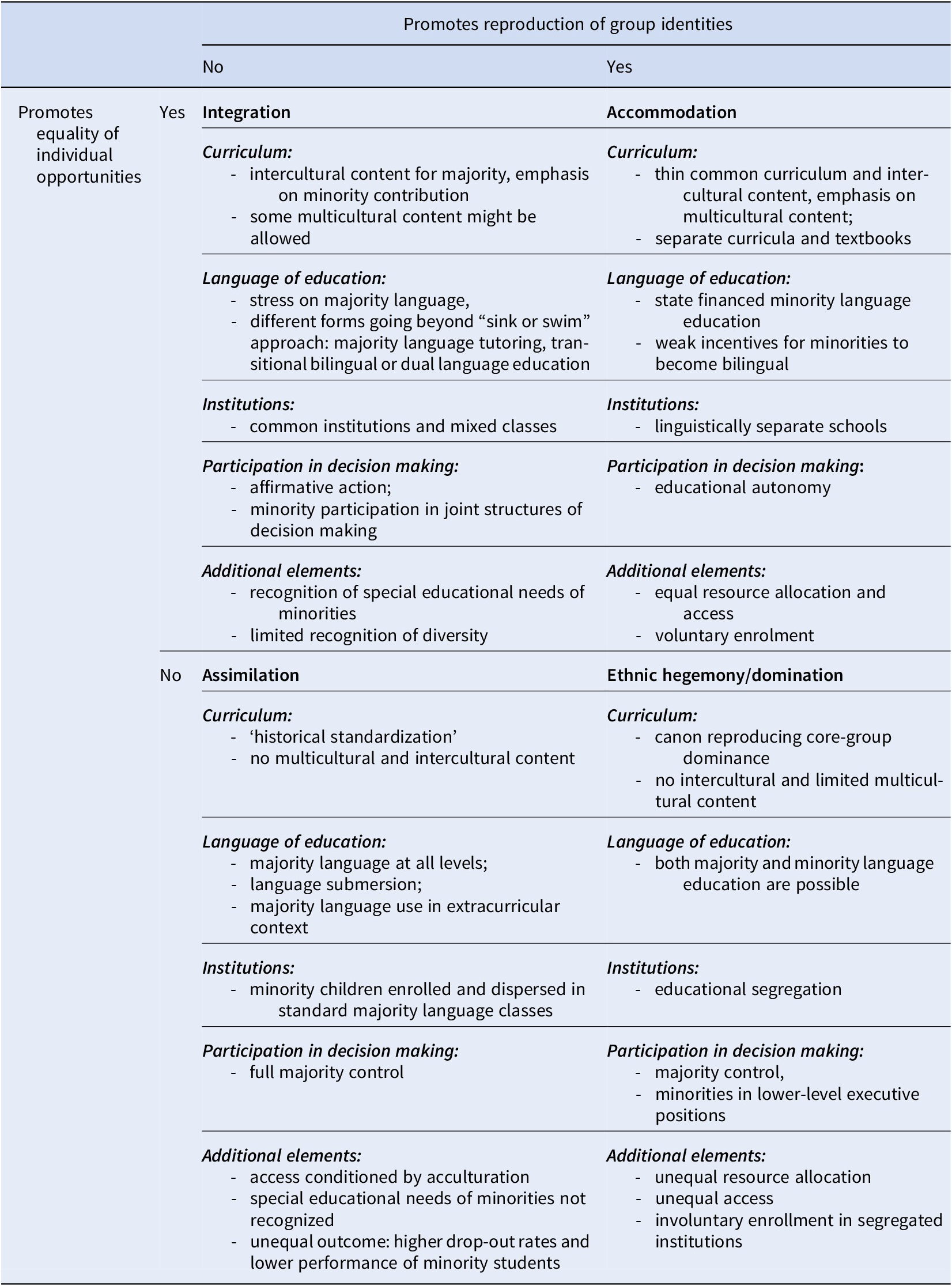

The first group of rights, which can be derived from basic human rights treaties, includes the right to education, the principle of non-discrimination, and equal access to all levels of education for minorities. Free and compulsory elementary education and equally accessible higher education are codified in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 26), and secondary education is accessible to everyone in the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (Article 13), while the principle of non-discrimination can be found in most human rights documents. The second group refers to positive rights and is related to four distinct areas of educational policy: curriculum content, language of education, institutional design, and participation in decision-making (Figure 1). Although they are addressed in a wide range of international documents,Footnote 7 there is no consensus on the content of these rights. Thus, educational policies regarding the abovementioned domains vary according to more general approaches of minority policies of individual countries.

Figure 1. Basic human rights and positive minority rights in the field of minority education (based on Thornberry (Reference Thornberry and Weller2007).

As for curriculum content, Thornberry (Reference Thornberry and Weller2007, 340) distinguishes between multicultural and intercultural curricula; the former allows minorities to reproduce their distinct identity and cultural canons, and the latter promotes knowledge about minorities among the majority. The language of education is certainly one of the most important domains, where policy aims vary from language submersion through subtractive or additive bilingualism to the maintenance or revitalization of minority languages (Baker Reference Baker2006; Churchill Reference Churchill1986; May Reference May2008, 177–198). The rights of minorities to establish and maintain their own educational institutions Footnote 8 can be deduced from the freedom of association. Nevertheless, no international legal document obliges states to finance separate minority educational institutions (Thornberry and Gibbons Reference Thornberry and Gibbons1996). In the case of minority participation in educational decision-making, institutional solutions may also vary, ranging from educational autonomy to the inclusion of minority group members in the unitary structure of educational decision-making. In what follows, we outline the educational policies characterizing the four minority policy regimes described above (see Table 2).

Table 2. Educational policies under different macro-regimes of minority policies

In assimilatory regimes, mass education is among the most important tools for national homogenization. At the level of curriculum, “historical standardization” is characteristic, enforcing not only a core group conforming cultural canon but also persuading children that they share a common ancestry, that of the core group (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O’Leary, Simeon and Choudhry2008, 68). Core conformity and acculturation are regarded as preconditions for educational opportunities, in particular, and (equal) societal participation in general. Thus, education is provided only in the majority language at all levels, typically without considering the special educational needs of minority students. Thus, minority language speakers are enrolled in standard majority language classes, a model called language submersion or the “sink or swim” approach. Certainly, not all minority students will be able to “swim,” thus, lower academic performance and high drop-out rates of minority students are rather common characteristics of assimilatory regimes (Baker Reference Baker2006, 216–219). Majority language use is fostered in an extracurricular context, too. Thus, official documents are unilingual, while the majority language dominates the linguistic landscape inside and outside the classroom. Minority students might be banned from using their native language in school, both inside and outside the classroom. Majority control over educational processes is preferred, and (as in other societal domains) participation in the decision-making of minorities is conditioned by “complete” acculturation and core-group loyalty.

Integration policies extend the principle of educational equity to minority students and aim to provide equal opportunities for them, recognizing their special educational needs and the fact that they usually struggle with learning deficits, lower academic performance, higher dropout rates, and so on. Integrative education aims to combat discrimination and negative stereotyping of minorities. Thus, the main focus is on intercultural education, but some special curricula might allow minority students to strengthen their self-esteem (Churchill Reference Churchill1986). The majority language plays a pivotal role in the educational process; nevertheless, language policies in education depart from the “sink or swim” approach and vary from tutoring through additional majority language classes to different forms of bilingual education, such as transitional bilingual education or even dual-language education (Baker Reference Baker2006, 233–235). Integrationists generally prefer to disperse minority students into mixed classes with majority students and tend to refuse their separation (Churchill Reference Churchill1986, 65). Minority participation in educational decision-making is also regarded as important and might be facilitated; however, even in the case of affirmative action, integrated structures are maintained.

Separate educational institutions are considered the main meso-level pillars underpinning accommodation (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1969) and the reproduction of minority identities (Churchill Reference Churchill1986). Therefore, in accommodative regimes, publicly financed and institutionally separate minority language education is characteristic. Importantly, accommodationist regimes also tend to grant official status to minority languages; thus, linguistically separated educational systems are not only tools of private cultural reproduction but also reproduce official bi or multilingualism. In some cases, binational states are composed of monolingual segments with English as a lingua between the substate communities (May Reference May2008, 178), while in others, knowledge of the majority language is still regarded as a key factor shaping individual mobility opportunities; therefore, special curricula are provided for minority students to learn it. Accommodation requires only a thin common curriculum and allows for the reproduction of separate cultural canons of different communities. Thus, multicultural content predominates over intercultural content, and different groups practically use different textbooks (Fontana Reference Fontana2017). Without entering into details concerning models of ethnic power-sharing in accommodative regimes, educational autonomy is the characteristic form of minority participation in decision-making (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1969).

Minority education under ethnic hegemony is segregated, while access to education and resource allocation are unequal. In several cases, this is a result of nationalizing policies aimed at reproducing the economic, political, and social dominance of the majority or altering systems of ethnic classification perceived as unfavorable and intolerable by majoritarian elites. Apartheid South Africa is an often-cited extreme example (Baker Reference Baker2006, 22) of de jure educational segregation. In post-socialist CEE, however, policies aimed at hegemonic control are unlikely to be codified explicitly, but they are more side effects of existing legislation or implicit consequences of discriminative policy implementation (Cianetti Reference Cianetti2019). In this respect, examples range from minority schools receiving fewer resources and attention to the discriminatory forms of examination. The consequences of these policies include lower minority participation in education and lower educational performance. For instance, it is widespread that graduation examinations are elaborated for the majority monolinguals, considerably limiting the success rate of minority students, thus limiting their further educational participation (Huszti et al. Reference Huszti, Csernicskó and Bárány2019; Menken Reference Menken2008). However, these are output indicators that cannot be examined solely through legal analysis. Under hegemonic control, enrollment in separate classes or schools is not (entirely) voluntary. Again, explicit apartheid-type legislation is unlikely to be found; nevertheless, (involuntary) educational segregation has been reported not only in the case of Roma (Messing Reference Messing2017; O’Nions Reference O’Nions2010) but also among Russophones in Latvia (Silova Reference Silova2006). Under hegemonic control, curricula (for both minority and majority students) aim to reproduce the dominance of the majority; thus, no intercultural elements are introduced. Nonetheless, some multicultural elements (for example, special subjects for minority students) may be allowed. Language policies of education may vary. In some cases, majority language education is fostered, while in others, minorities are allowed (in extreme cases forced) to learn in their native language. Hegemonic control does not allow for effective minority participation in educational decision-making, and minority participation is typically limited to lower-level executive positions.

Minority education in Central and Eastern Europe: Four illustrative case studies

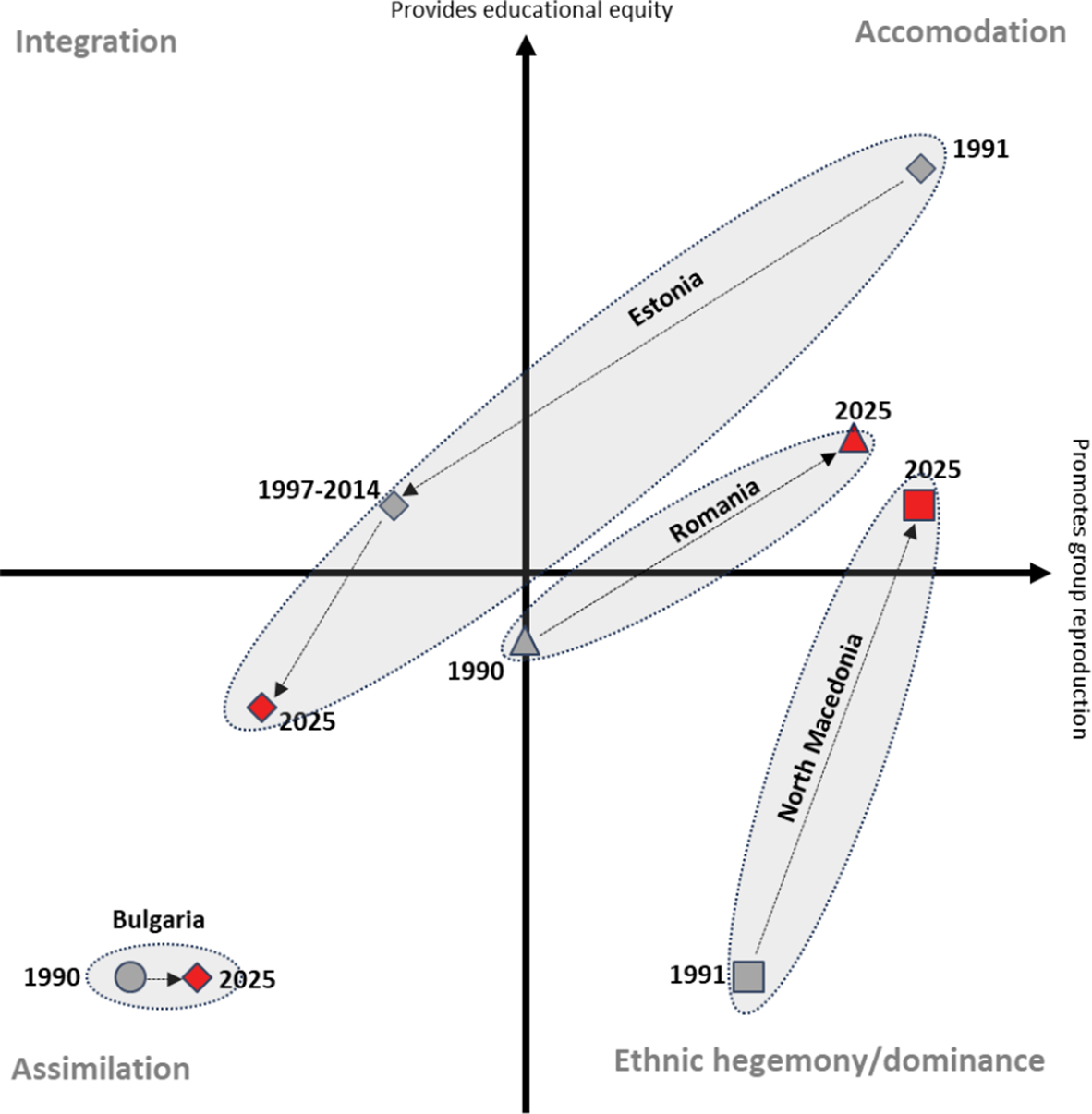

In what follows, we illustrate the usefulness of our typology by focusing on four CEE states, home countries of large, territorially concentrated minority communities. The selection of the cases was guided by our intention to describe how different types of minority policies emerge, how educational policies evolve under different macro-models and how different educational policies affect educational equity for minorities. We focus mostly on the time period following regime change and, in the case of Estonia and the Republic of Macedonia, the beginning of independent statehood. The four countries inherited different regimes of minority policies, and minority education was also different, accordingly (Figure 2). In our diachronic analysis, we try to show continuities, path-dependent gradual chances and to identify critical junctures resulting in more radical shifts in legislative and institutional processes. It is also important to understand how some governments consolidate one type of minority and educational policy over time while others combine different approaches or change one type to another.

Figure 2. Institutional pathways of educational policies in Bulgaria, Estonia, North-Macedonia and Romania.

Bulgaria can be regarded as a consolidated ethnic democracy that combines the assimilationist approach with ethnic hegemony (Johnson Reference Johnson2002; Mahon Reference Mahon1999). In its educational policies, the regime change was not conducive to any radical shift, while subsequent political events caused only minor changes. Thus, its assimilationist educational policies, dating back to the 1960s, have remained practically unchanged. In Estonia, an asymmetric form of binationalism was characteristic during the Soviet period, with a high degree of educational parallelism between the Estonian and Russophone segments of society. After gaining independence, Estonian elites were engaged in nation- and state-building, securing the socio-economic and cultural dominance of the titular core (Järve Reference Järve2000; Pettai and Hallik Reference Pettai and Hallik2002). Until recently, however, the state put a strong emphasis on the special educational needs of Russian speakers and, thus, integrative elements were quite significant in the educational system. It was after Russia’s repeated aggressions against Ukraine in 2014 and 2022 that a radical securitization of minority policies occurred, and Russian language education was abolished altogether (Csergő et al. Reference Csergo, Kallas and Kiss2025), placing Estonia in the cluster of assimilationist regimes. The Republic of North Macedonia moved in the opposite direction after its independence, the 2001 Ohrid Agreement representing a radical historical juncture and transforming majority domination into accommodation (Holliday Reference Holliday, Smooha and Järve2005) and increasing Albanian access to secondary and, especially, tertiary education. Romania has gradually developed into an accommodationist regime, lacking, however, constitutional guarantees of power sharing and relying on informal political bargaining and meso-level institutional parallelism (Kiss et al. Reference Kiss, Toró, Székely, Kiss, Székely, Toró, Bárdi and Horváth2018). It is illustrative for states with robust forms of minority education but under majoritarian nation-building and continuous majority dominance in the public realms.

The upcoming four sections focus on changes and continuities in national legislation and present country level educational statistics. All of our case studies follow the same analytical logic. We focus on positive minority rights referring to curriculum content, language of education, institutional design and educational decision-making, and we also provide data concerning the access to different levels of education of minorities (see Table 2). Given the diversity in national-level data gathering, however, our case-by-case analysis does not provide standardized comparable quantitative data on this latter aspect. The last section focuses on educational equity and, using 2022 PISA data, presents the educational performance of minority students in comparison to that of their majoritarian peers.

Bulgaria: An assimilationist approach and majority control in education

In the case of Bulgaria, the late 1960s and the 1970s represented the major institutional turning point in minority education, when, after merging Turkish language schools with Bulgarian ones, Turkish language education was abolished altogether (Eminov Reference Eminov2000; Mahon Reference Mahon1999, 156). In spite of the Bulgarian discourse of “restoration of minority rights” in the framework of a “Bulgarian ethnic model” (Vassilev Reference Vassilev2010), in the domain of educational policies, there were only minor changes following 1990. The Pre-school and School Education Act (79/13.10.2015) puts emphasis on national identity, national values and “Bulgarian educational traditions”Footnote 9 and gives the possibility for schools to introduce subjects “in the field of defense of the Motherland, (…) which strengthen national awareness, patriotic spirit, and love for the Motherland.”Footnote 10 There are no special subjects or curricula for minorities, and multicultural content is limited to religious education. This subject was introduced as an elective course in 1997; however, despite this development, few school directors were eager to implement it, and only a small number of Turkish students received religious education (Yildririm et al. Reference Yildririm, Ozlem, Çaglar and Rodoplu2016).

Bulgarian legislation, including the Constitution, discusses the issue of learning Bulgarian in disproportionate detail. While education is in Bulgarian only, the Pre-school and School Education Act insists further not only on the right but also on the “obligation of every Bulgarian citizen”Footnote 11 to learn the state language. It is a clear sign of the assimilatory approach that the law defines Bulgarian as the sole form of communication, not only inside but also outside classes, allowing teachers to act in protecting these language norms.Footnote 12 This element was introduced for the first time by the 2/2009 Ordinance of the Ministry of Education (Lazarova and Rainov Reference Lazarova, Rainov and Stickel2011, 102) and criticized by the ACFC because it “bans teachers from talking to pupils in their minority languages outside the classroom, has a chilling effect as it creates a sense of shame.”Footnote 13 The edict was included in the 2015 Pre-School and School Education Act as well.

Although the Constitution recognizes the right of minorities “to study and use their language alongside the compulsory study of Bulgarian,”Footnote 14 the educational system actually does not provide any robust institutionalized solution for putting this right in practice. Turkish language classes were introduced in primary and lower-secondary schools during the 1992/93 semester with 144,000 enrolled students. In the long run, however, the program “has fallen short of expectations,” with the number of those learning Turkish as an optional subject being only 7,565 in the 2015/2016 semester (Eminov Reference Eminov2000). There are multiple causes for the failure. Many school directors proved hostile toward the program and refused to implement it (Eminov Reference Eminov2000). Mutlu and Kavanoz (Reference Mutlu and Kavanoz2010) and Eminov (Reference Eminov and Tasheva2019) argued that Turkish was in the same package as English and other international languages, which is why many students did not opt for the former. Furthermore, Bulgaria did not provide high-quality textbooks and teacher training for Turkish language teaching, and when Turkey offered textbooks, Bulgaria refused to accredit them (Vassilev Reference Vassilev2010, 304). Demand-side factors are also important. Turkish elites did not elaborate on an “educational paradigm” favoring native language education and did not formulate claims regarding more elaborate forms of Turkish language education. Furthermore, many Turks associate mastering standard Turkish with a willingness to emigrate to Turkey. While lacking a well-established minority institutional system, they do not associate any instrumental value with their stigmatized vernacular in Bulgaria (Kyriazi Reference Kyriazi2016).

Bulgaria not only does not provide publicly financed education in minority languages but also bans private forms of minority education, including informal educational institutions such as Sunday Schools. Participation in the educational decision-making of minorities was not facilitated, and majority dominance over the educational process was strengthened by centralizing measures. While previously mayors could nominate at least the management of municipal kindergartens, this license was returned by central authorities under the 2015 Pre-school and School Act. The same act centralized the selection of committees, representatives of the regional divisions of education, local administration, and public oversight boards of the schools.Footnote 15 Thus, the Turkish majority municipalities have lost the possibility of limited informal control over educational processes.

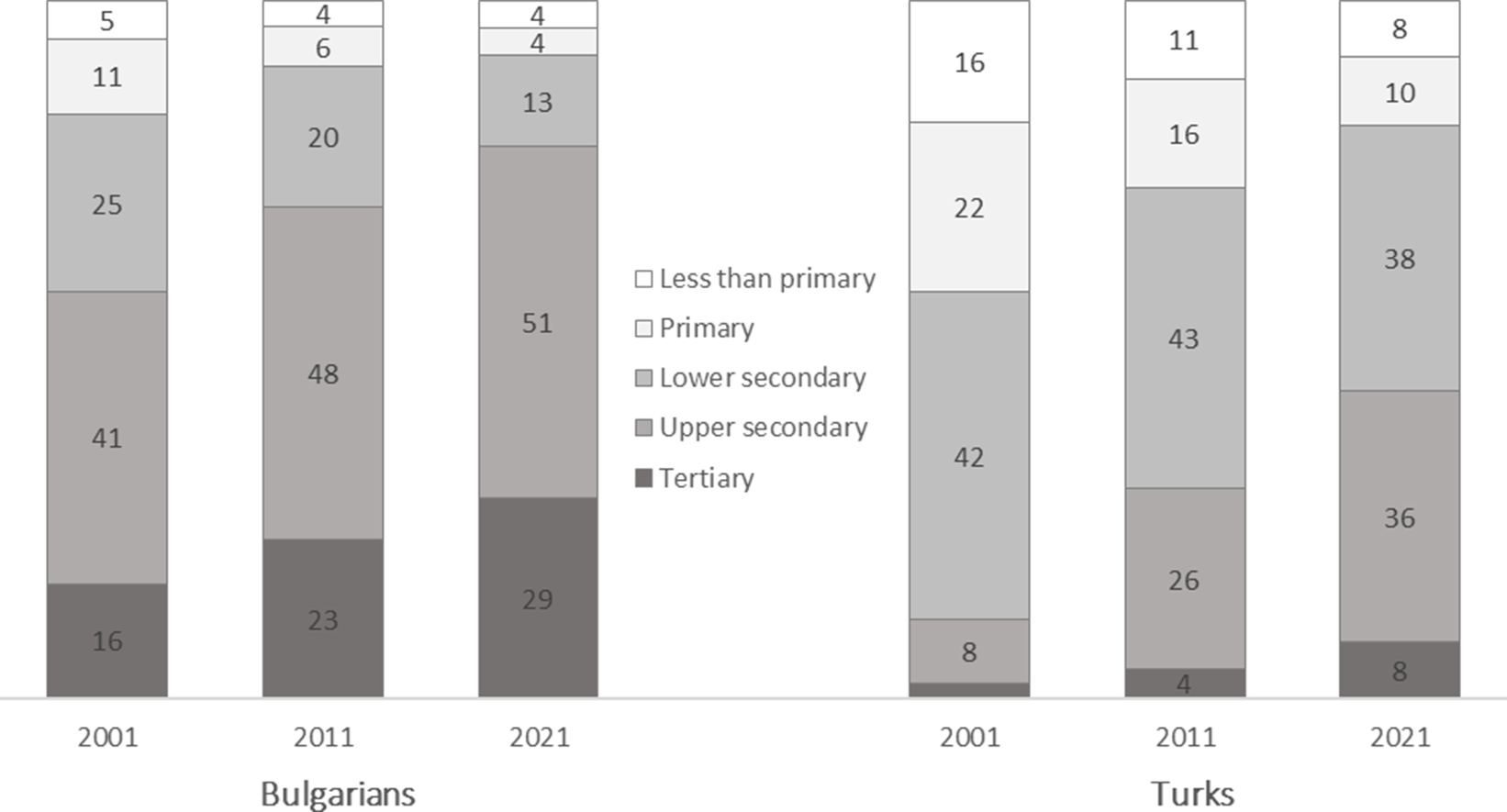

Bulgaria’s system of ethnic stratification is certainly shaped by multiple factors, among others the concentration of the Turkish minority in rural areas and economically peripheral regions. Nevertheless, it is also a consequence of educational policies that Turks are hugely underrepresented among both tertiary and upper-secondary graduates and overrepresented among those with less than lower-secondary and lower-secondary education (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Educational attainment by ethnicity in Bulgaria.

Source: Bulgarian Census results.

Estonia: From linguistically separate education to integration and assimilation

Estonia’s educational system transformed profoundly following 1991, when the small Baltic country gained independence. The direction of these changes was settled in the early 1990s, along with legal restorationism designed to reestablish interwar Estonian statehood under the demographic, socio-economic and cultural dominance of the titulars (Cianetti Reference Cianetti2018; Järve Reference Järve2000; Pettai and Hallik Reference Pettai and Hallik2002). Csergo et al. (Reference Csergo, Kallas and Kiss2025) argue that Estonia’s approach to diversity management was governed by a radical form of titular ontological insecurity, perceiving existing post-Soviet ethnic landscape and social realities (for example, large proportion of Russophones, asymmetric bilingualism with Russian as a lingua franca and the system of ethnic stratification, with Russians concentrated in urban centers and key economic sectors) as an “anomaly” and being against titular national aspirations.

In 1991, a linguistically separate educational system existed, with both Estonians and Russian speakers studying in their native languages, but with the majority of Estonians becoming proficient in Russian and the majority of Russian speakers not learning Estonian. From early on, educational policies were shaped by more general attempts of language planning and ideas concerning the “(re)integration” of Russian speakers into the Estonian nation state. In the early 1990s, Estonia switched from official bilingualism to Estonian as the sole official language. This shift did not only aim to improve the status of the Estonian language but also to strengthen titular positions in social and economic life (Skerrett Reference Skerrett2013). After realizing that Russian speakers became truly marginalized, however, policy solutions were elaborated to “reintegrate” them, primarily through the medium of the Estonian language (Tavits Reference Tavits, Cheneval and Ferrín2018).

In line with these developments, learning the Estonian language has become the cornerstone of “educational reform.” The 1997 Educational Law introduced a model of bilingual education, with Russian children starting learning in their mother tongue and learning two subjects in Estonian from an early age. This was changed to a transitional bilingual model in 2007, when it was decided that from 2011 in upper-secondary schools, at least 60 percent of subjects would be taught in Estonian. Five compulsory subjects were nominated, but natural sciences and mathematics were kept in Russian (Skerrett Reference Skerrett2013). Some schools were also engaged in so-called early and late immersion programs, providing bilingual education for Russian students from younger ages (Tavits Reference Tavits, Cheneval and Ferrín2018). The transition to Estonian language education was pushed forward in 2022 when the Estonian parliament amended the law, initiating the transition of Russian schools at all levels to full Estonian language education from 2024 (Csergo et al. Reference Csergo, Kallas and Kiss2025).

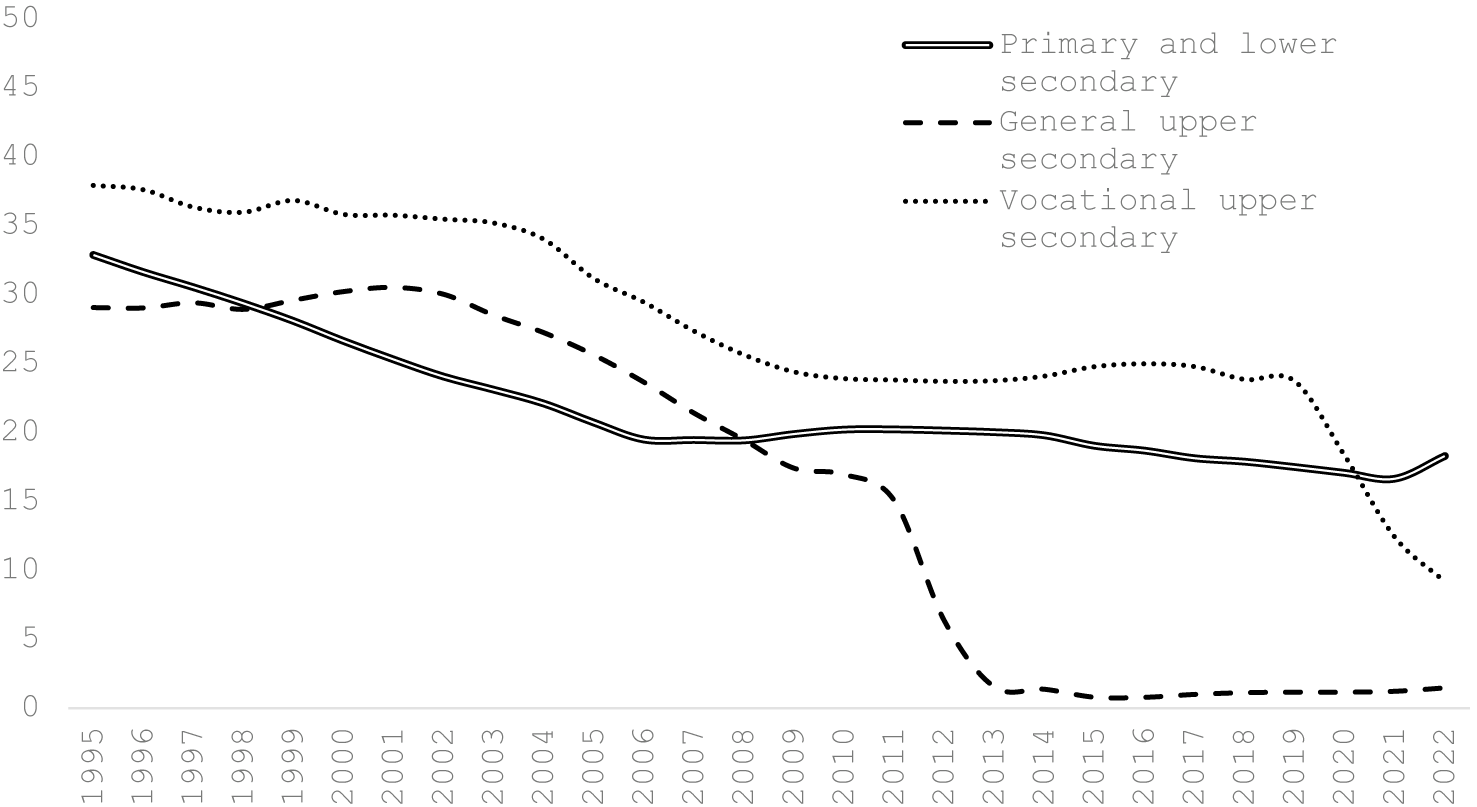

Importantly, the 2007 changes did not apply to vocational schools, where Russian language education was maintained until 2019, thus channeling Russian students in that direction and excluding them from tertiary education (Musset et al. Reference Musset, Field, Mann and Bergseng2019). These developments can be observed in Figure 4, showing that a large proportion of students learned in Russian in vocational schools, while in upper-secondary education, everybody switched to (dominantly, 60 percent) Estonian language education in 2013.

Figure 4. The proportion of students learning in Russian by educational level in Estonia.

Source: Estonian Statistical Institute.

The transition to bilingual education did not affect the final examination. At the end of the upper-secondary level, in addition to mathematics and foreign language, Estonian native speakers take an exam in Estonian as a first language, while minority students take Estonian as a second language exam (Skerrett Reference Skerrett2013). The 1997 Educational Law also made Estonian language proficiency compulsory for teachers, established a centralized monitoring body, the Language Inspectorate, and regularly screened the Estonian language knowledge of Russian-speaking teachers (Poleshchuk and Semjonov Reference Poleshchuk and Semjonov2009; Tavits Reference Tavits, Cheneval and Ferrín2018).

The 2007 Educational Law not only envisions Estonian language proficiency but also a transition toward “traditions of Estonian culture and common European values.”Footnote 16 Consequently, the national core curriculum aimed to reproduce the Estonian cultural and historical canon. Subsequent switches to new curricula, however, have also materialized in increasing ethnic inequalities, as the new textbooks, methodologies, and teaching materials were usually produced in Estonia only, making it difficult for Russian schools to take steps with the consecutive waves of reform. It was in this context that some Estonian observers criticized the incapability of Russian schools to adapt, stressing that they resisted new teaching methods because of their fidelity to old and scholastic “Soviet methods” (Asser et al. Reference Asser, Pedastsaar, Trasberg, Vassilchenko, Lauristin and Kheĭdmets2002).

While altering the language of education, reform initiatives never planned to abolish institutional parallelism along ethnic lines, leaving the separate organizational structure of Russian education untouched (Talal Reference Talal2020). According to official statistics, the share of dual-stream schools grew radically after 2011; however, this was not the result of merging Russian and Estonian schools but rather a change in their labeling (for example, schools teaching in 60 percent of Estonians were considered Estonian language organizational structures) (Helemäe Reference Helemäe and Vetik2015).

Liberalization, democratization, and decentralization led to relatively large leverage over the educational process of Russian elites at the municipal level in the early 1990s, including influence over managerial, financial, and curricular aspects (Heidmets et al. Reference Heidmets, Kangro, Ruus, Matulionis, Loogma and Viktorija2011). However, beginning with the 1997 Educational Law, the decisional power of municipalities was limited to influencing the nomination of school management, teaching staff, and budgetary issues, whereas curricular and linguistic issues were centralized.

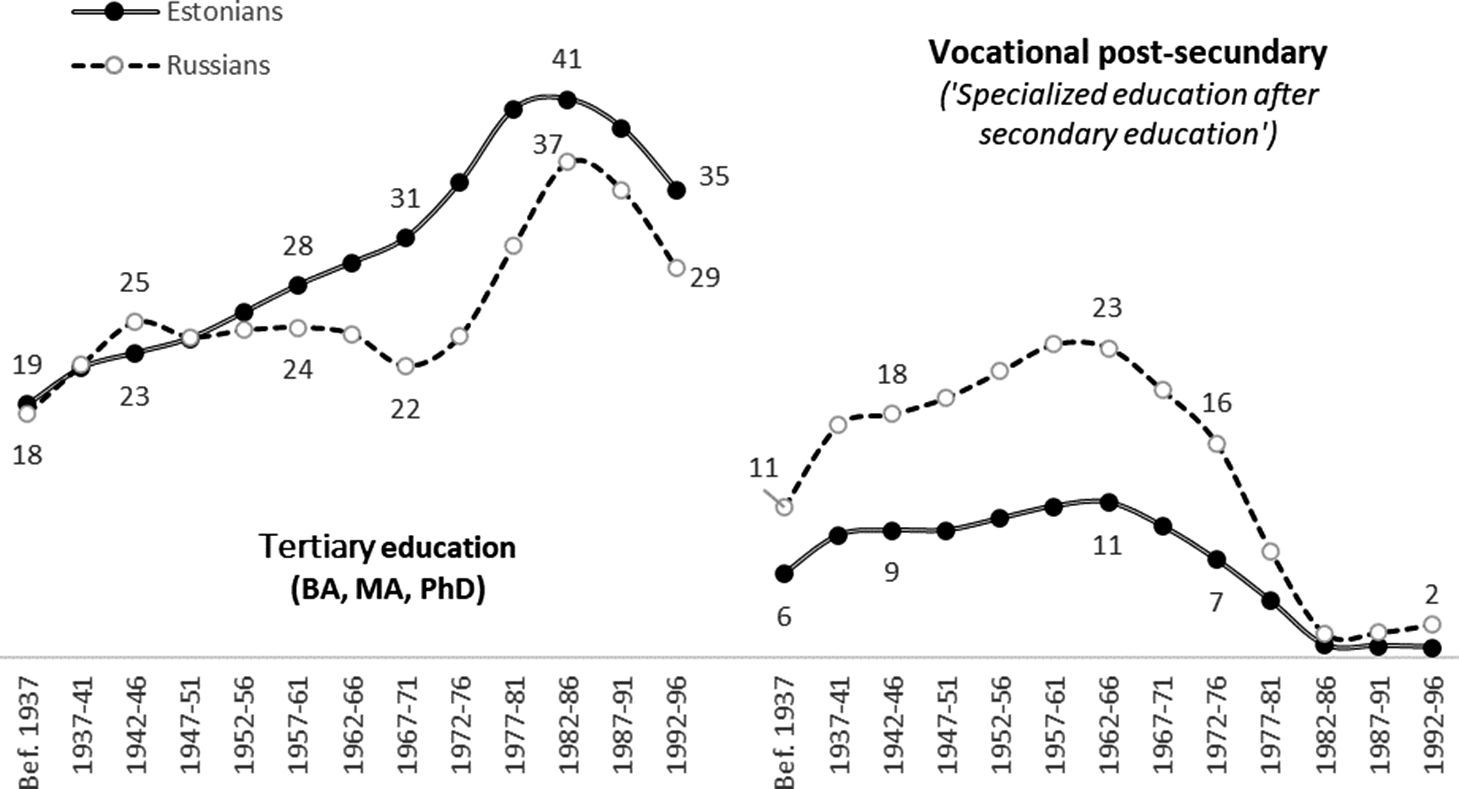

The Estonian education system does not ensure equal access of minority speakers to education, especially at the tertiary level. While the proportion of university graduates is similar in the case of those born before 1956, Russians increasingly lag behind Estonians in younger cohorts. Meanwhile, Russians are overrepresented among those with “specialized education after secondary education,” a term used by the Estonian Statistical Institute to mean post-secondary vocational education (Figure 5). This possibility, unlike tertiary education, is open to those finishing vocational upper-secondary education. As previously mentioned, Russian speakers were hugely overrepresented in this educational form (available in Russian until 2019). Although Russians were concentrated in the industrial sector before independence, the decision to keep Russian language teaching intact at the vocational level, while introducing Estonian in academic upper-secondary education resulted in further channeling of Russian speaking students in secondary and post-secondary tracks offering only limited possibilities of social mobility.

Figure 5. The proportion of tertiary education and vocational post-secondary by birth-cohorts and ethnicity in Estonia.

Source: 2021 Estonian Census results.

The Republic of North Macedonia: Providing access under accommodation

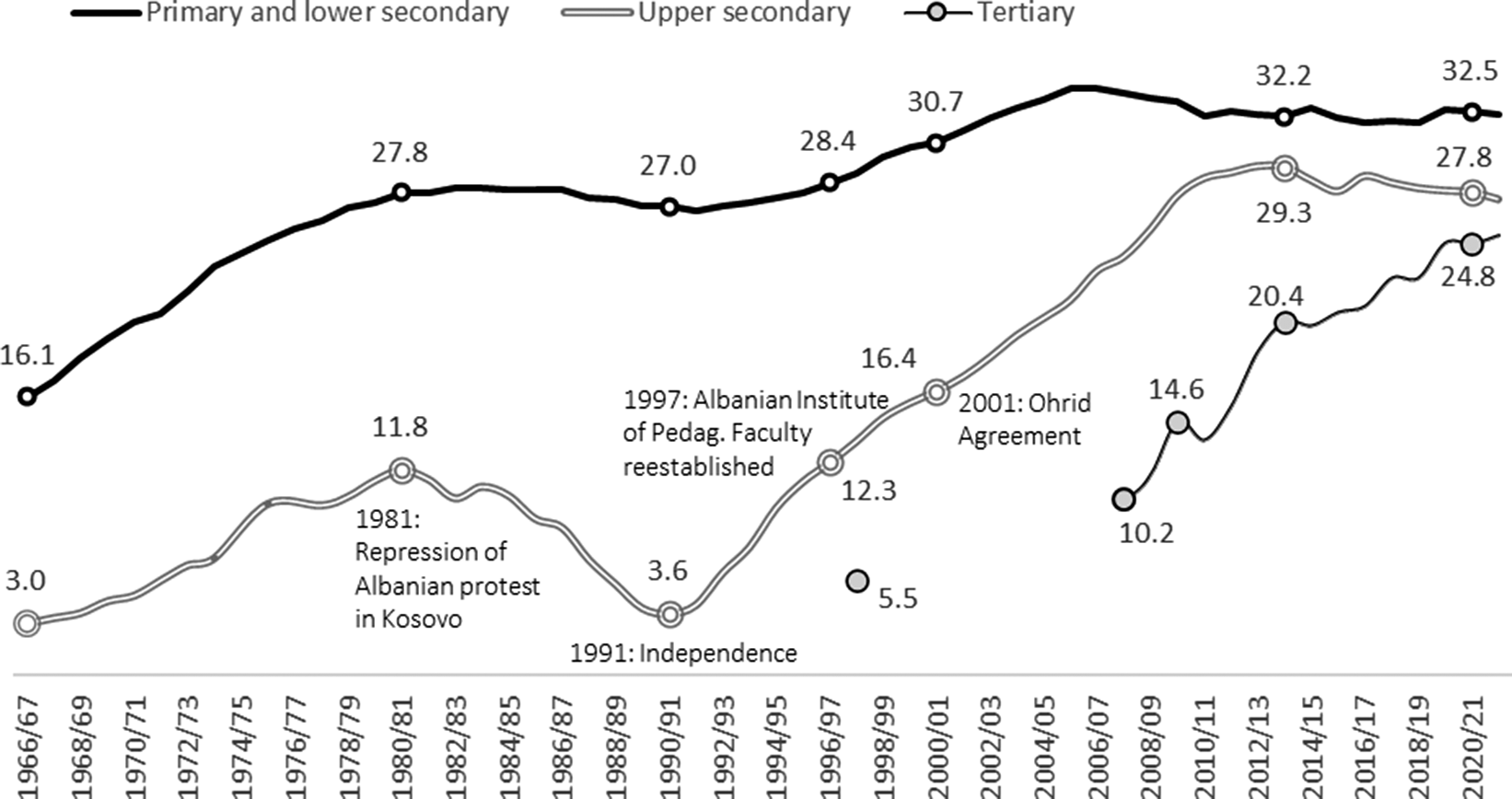

The institutional pathways of diversity management in the Republic of North Macedonia are unique among our cases, turning the country from a regime of ethnic hegemony into accommodation (Holliday, Reference Holliday, Smooha and Järve2005). From a macro-perspective, the 2001 Ohrid AgreementFootnote 17 should be regarded as the most important turning point. In the domain of educational policies, however, processes seem to be more gradual, with 1981 (the repression of Albanian protests in Kosovo) and 1991 (gaining independence) as important junctures as well. The crux of educational policies in the Republic of North Macedonia was the limited access of Albanians to upper-secondary and tertiary education (Figure 6). After a period of expansion (1968–1980), Albanian language education was significantly curtailed beginning in 1981. The Albanian Institute of the Pedagogical Faculty at the University of Skopje was abolished in 1985. As a result, the proportion of upper-secondary school students learning in Albania fell from 11.8 percent in 1981 to 3.6 percent in 1991. This issue, along with an almost caste-like system of ethnic stratification, was among the factors leading to the 2001 Albanian armed insurgency.

Figure 6. The proportion of students learning in Albanian by educational level in North-Macedonia.

Source: Yearbooks of the State Statistical Office of North Macedonia 1999-2022.

Following independence, Albanian language secondary education began to expand again, and the Albanian Institute at the renamed Cyril and Methodius (formerly Skopje) University was reestablished in 1997. The 1991 Constitution guaranteed native-language education at the primary and secondary levels;Footnote 18 however, it did not guarantee Albanian language universities. Additionally, Albanians remained severely underrepresented not only among university students but also at the upper-secondary level. Thus, in the 1990s, one of the central claims of Albanians was the recognition and state financing for the (illegally established) Tetovo University and the further expansion of secondary education. The 2001 Ohrid Agreement and subsequent educational legislationFootnote 19 fulfilled these Albanian claims, providing state funding for Albanian language universities and positive discrimination (quotas) in university enrollment. Consequently, the accelerated expansion of Albanian language education, including tertiary education, began after 2001.

The Ohrid Agreement was followed by curriculum reforms. A new history curriculum based on the so-called “proportional approach” was introduced in 2005. This has left the (ethnically focused) Macedonian national historical narrative practically intact while introducing additional lessons on the history of different ethnic groups. Teaching history had to follow the new curriculum in all classes, irrespective of the language of instruction. Theoretically, the result is a symmetric (even if not integrated) intercultural approach. Nevertheless, additional regulations practically allowed for teaching history according to different curricula in Albanian and Macedonian language classes. First, the curriculum allowed teachers to choose thirty-six out of forty-eight lessons. This meant that Macedonian teachers could avoid lessons concerning the Albanians altogether, while Albanian teachers could focus mostly on the history of their ethnic group (Fontana Reference Fontana2017, 144). Second, history textbooks in different languages were written simultaneously by different (Albanian, respectively Macedonian) groups of authors. Consequently, Albanian and Macedonian students use different textbooks despite the seemingly uniform curriculum (Fontana Reference Fontana2017, 142).

The rather limited role of the majority language in the education of Albanian children is another characteristic of the Republic of North Macedonia. First, the proportion of Albanian students enrolled in majority-language education is extremely low, and choosing Macedonian language education is limited to smaller minority groups, including Turks, Bosniaks, and Serbs. Second, although the Constitution guarantees the right to learn the Macedonian language at all levels of education,Footnote 20 since 2008, Albanian children have learned it only from grade four and only two hours per week. The 2010 Strategy for Integrated Education employed by the Ministry of Education in cooperation with the OSCE tried to reintroduce the Macedonian language in lower grades; however, it failed to be implemented because of the heavy resistance of Albanian ethnic parties. Third, Macedonian language knowledge of Albanian children has not been examined in practice. A uniform State Matura was introduced in 2008 (Murchan et al. Reference Murchan, Shiel and Mickovska2012) with three compulsory exams in the native language or a foreign language, mathematics, and an elective subject, with Albanian students rarely opting for Macedonian (Kitchen et al. Reference Kitchen, Maghnouj, Li, Bethell, Fordham and Fitzpatrick2019, 95–96). It should also be emphasized that ethnic Macedonians are even more intransigent in learning the Albanian language (Fontana Reference Fontana2017, 130).

The Republic of North Macedonia’s educational system is institutionally separated along ethnic lines. In the 2018/2019 academic year, there were 265 primary and lower-secondary schools and 22 upper-secondary schools teaching exclusively minority languages (most of them in Albanian). This means that most Albanian students are educated in separate units, whereas the number and proportion of mixed schools have decreased over time. Moreover, even in these formally integrated educational units, Albanian and Macedonian students learn in separate buildings or “ethnic shifts.” There are several often-discussed and widely celebrated initiatives for bilingual education (Fontana Reference Fontana2017, 134). However, only a few dozen Albanian and Macedonian students are enrolled in such institutions, and the presence of these integrated forms of education has hardly altered the trend of increasing institutional separation.

Before 2001, central-level decision-making in education (similarly to defense or interior affairs) was considered by Macedonian political actors “too sensitive to be headed” to Albanians (Koneska Reference Koneska2012, 38). Following 2001, however, several Albanian politicians served as ministers of education, while informal practices also helped power-sharing in educational decision-making (Fontana Reference Fontana2017, 224). Over time, it became a well-established practice that a Macedonian-Albanian minister-vice-minister tandem led the portfolio and each of the parts dealt with their “own schools.” Additionally, after the Ohrid Agreement, many responsibilities concerning education were given to local municipalities (Lyon Reference Lyon2011). Municipalities became school founders and owners (Fontana Reference Fontana2017, 213) and gained the power to decide on resource allocation to schools, appoint school directors, and abolish, merge, or separate educational institutions. All of these competences significantly increase local-level minority control over educational processes, especially in Albanian majority municipalities.

Romania: Education under unequal accommodation

In the Eastern European context, Romania represents a case of gradual accommodation, even if, unlike the Republic of North Macedonian case, without constitutional guarantees for power sharing. The Romanian case also highlights the limitations of accommodation relying mostly on informal rules (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2019; Dodge Reference Dodge2020), as relations between Romanians and Hungarians, the largest minority community, remain highly asymmetrical. In this setting, the reproduction of Hungarian identity relies on a strong network of meso-level minority institutions (schools, churches, media outlets, cultural institutions, etc.) that is described by some observers as institutionally sustained ethnic parallelism (Kiss et al. Reference Kiss, Toró, Székely, Kiss, Székely, Toró, Bárdi and Horváth2018). Hungarian elites, acting through a robust and unitary ethnic party, play a pivotal role in governing minority institutions (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1969), even if their decisional power remains mostly informal and relies more on ad hoc and informal processes of political bargaining than on constitutional or legal guarantees.

In this ambivalent context, the aims of minority education are not well-defined. The rather strong form of minority language education, characterized by the dominance of the Hungarian language, the predominance of separate Hungarian language schools, and the stress on certain elements of the Hungarian national canon is in line with the “educational paradigm” of the Transylvanian Hungarian elites (Kyriazi Reference Kyriazi2016), and goes far behind the goal of private language reproduction (Churchill Reference Churchill1986). Nevertheless, given the predominance of the Romanian language in the public sphere (Csergő Reference Csergő2007) and less emphasis on aspects of equity, it also helps to reproduce the subordinate position of Hungarians and leads to an increasing marginalization of the minority community.

The process of democratization beginning in 1990 also marked important changes in minority education; however, legal and institutional changes in 1948, when the state socialist regime established the still functioning system of state-financed minority language education, constitute a far more important historical juncture in educational policies. Indeed, in the late 1950s, a process of merging Hungarian language educational institutions with Romanian ones began, and the possibilities of learning in Hungarian at the secondary and tertiary levels narrowed considerably during the 1970s and the 1980s. Nevertheless, the process of revitalizing and reorganizing native language education, pushed by Hungarian elites, relied on the legal and institutional framework established by Romania’s Communist Party.

Following 1990, a gradual accommodation of Hungarian educational claims was characteristic to the point that Béla Markó, former president of the dominant Hungarian ethnic party, described the 2011 Law on Education as “an endpoint of a long, long process through which we established the legal framework of native language education” resolving “most problems of Hungarian language education,” with the exception of educational autonomy (see Csergő et al. Reference Csergo, Kallas and Kiss2025). This declaration is also indicative of the fact that Hungarian elites care more about identity reproduction than about equity in education and substantive equality.

Indeed, the 1/2011 Law on Education reaffirmed Romania’s commitment to sustaining state-financed minority language education from nurseries to tertiary education.Footnote 21 The law makes it possible to teach all subjects in minority languages, apart from the Romanian language and literature, which has been taught according to a specific curriculum since 2011. There is a strong emphasis on multicultural curriculum in minority education, as minority language and literature, musical education, the history and tradition of minorities, and religion (in the case of cults practiced overwhelmingly by Hungarians) are taught according to specific curricula. On the contrary, intercultural elements are rather weak; textbooks used by majority students reproduce the Romanian ethno-national canon and even negative stereotypes concerning minorities (Kiss et al. Reference Kiss, Toró and Jakab2021).

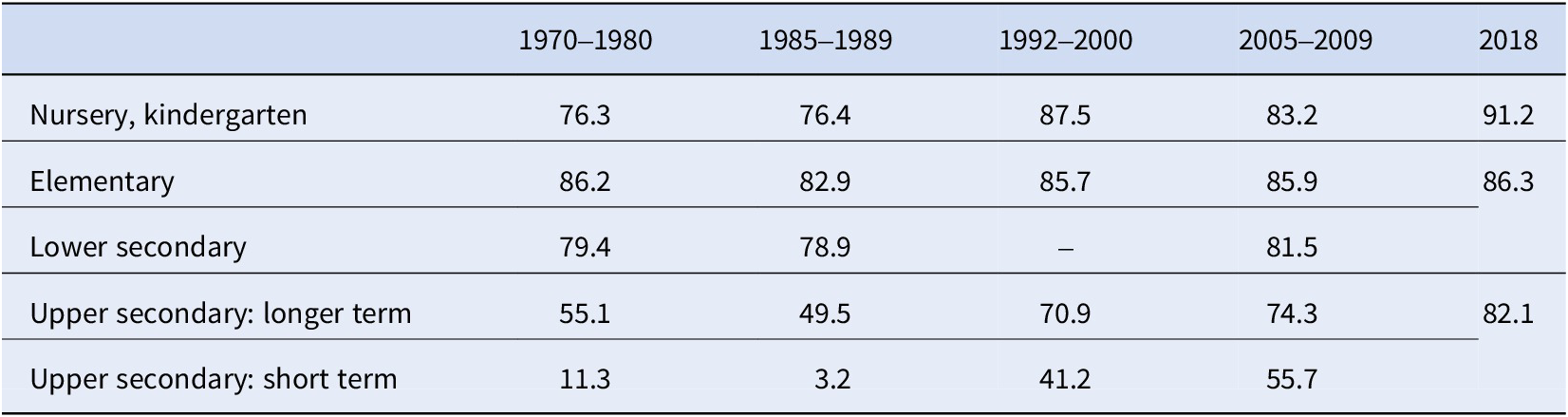

Following the regime change, the proportion of Hungarian children studying in Hungarian continuously increased, reaching 91.2 percent in kindergarten, 86.3 percent in elementary and lower-secondary education, and 82.1 percent in upper-secondary education (Table 3).

Table 3. The proportion of Hungarian students enrolled in native language education in Romania (1970–2018)

Source: Ministry of Education: 1970-1980; 1985-1989; 1992-2000; 2005-2009; ARACIP (Romanian Agency for Quality Assurance in Public Education): 2018.

The 2011 Law on Education also accelerated the existing process of institutional separation,Footnote 22 and the proportion of Hungarian students learning in Hungarian-only schools reached 65 percent in 2019. One explanation for why Hungarian elites and parents prefer separate institutions is the highly asymmetric position of Hungarian streams in dual-stream schools, including unequal resource allocation, an asymmetric linguistic landscape, and limited institutional decision-making (Kiss and Toró, Reference Kiss and Toró2024).

The law guarantees limited forms of educational decision-making in an otherwise over-centralized institutional framework. In minority language and dual-stream schools, the director or the deputy director should belong to the minority group and should be recommended by “minority organizations” representing the given community (for example, ethnic parties).Footnote 23 Minority personnel should also be employed in school inspectorates, while at the central level, there is a State Secretariate for Minority Education in the Ministry of Education. Through this multilevel system, Hungarian elites have considerable leverage over the educational processes. Nevertheless, their decisional competencies are poorly formalized and rely to a great extent on informal (thus unaccountable and often ad hoc) institutional practices (Gáll and Keszeg Reference Gáll and Keszeg2014).

Although Romania’s educational system seems highly effective in reproducing Hungarian national identity, it is far less effective in producing equality in terms of resource allocation, access to higher education, and cultural recognition through intercultural education. As already mentioned, resource allocation inside dual-stream schools is unequal, a process not even officially monitored but evidenced only by exhaustive surveys on minority language education (Kiss and Toró Reference Kiss and Toró2024). The weaknesses of intercultural education, as well as the lack of any institutionalized possibility for majority students to learn minority languages, are factors that reproduce status inequality mediated primarily by language hierarchies. The most significant form of institutional discrimination, however, is connected to the baccalaureate examination and results from the fact that the passing rates for Hungarian students are far below the national average. Hungarian students overperform their majority fellow in native language and literature, compulsory subjects (either mathematics or history depending on the profile of the upper-secondary education), and elected subjects. Nevertheless, many of them fall short in Romanian language and literature exams, using the same tests as for Romanian monolinguals.

Inequities resulting from the baccalaureate examination evidently limit access to higher education among Hungarian students compared to their majoritarian counterparts, resulting in consistently lower proportions of higher education graduates across all birth cohorts (Figure 7), even if not to the same extent as in the case of Bulgarian Turks or the Republic of North Macedonian Albanians. Unequal access to tertiary education evidently limits labor market opportunities of young Hungarians.

Figure 7. The proportion of tertiary education graduates by birth cohort and ethnicity in Romania.

Source: IPUMS dataset, Census 2011.

Comparative assessment of equity outcomes: PISA 2022 results from a minority perspective

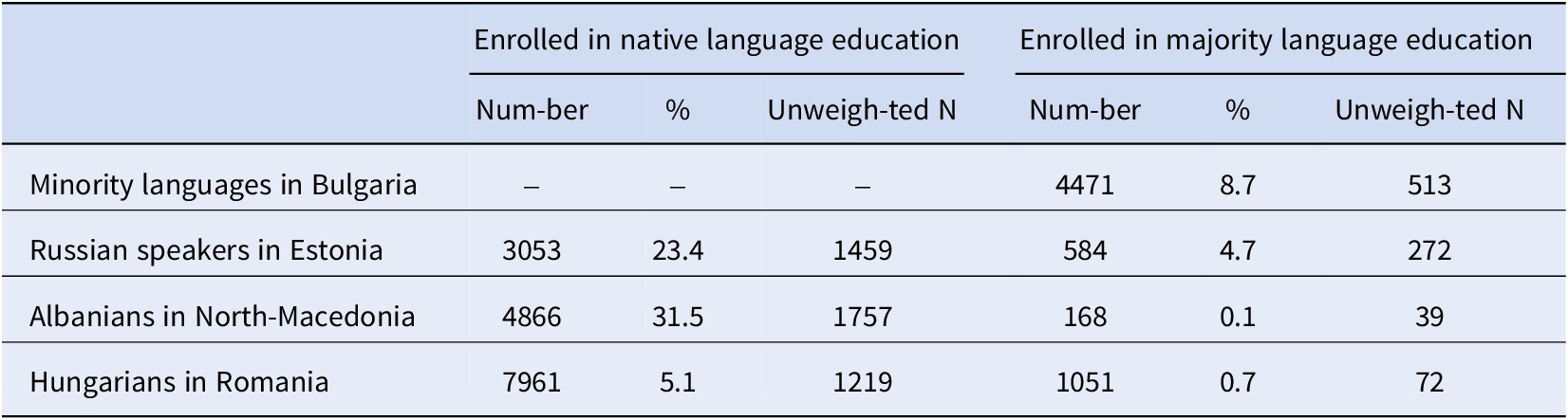

Although rarely utilized in this direction, PISA results represent a comparative tool for investigating educational inequalities affecting linguistic minorities. The 2022 wave is especially useful for our purposes, as, for the first time, a representative subsample was elaborated for students learning in Hungarian in Romania, while for Estonia and the Republic of North Macedonia, given the large proportion of those learning in Russian and Albanian, there are by default enough cases for a detailed analysis (Table 4).

Table 4. 15-year-old minority students enrolled in native and majority language education according to 2022 PISA assessment

Source: 2022 PISA database.

Moreover, even if unweighted case numbers are lower (especially in Romania and the Republic of North Macedonia), PISA offers data concerning minority language speakers enrolled in majority language education, too. As already mentioned, in Bulgaria, majority-language education is the only option, whereas in the Republic of North Macedonia, Romania and, until recently, Estonia, minority parents could choose between majority- and native-language education. According to PISA results, the majority of the 15-year-old nontitular students (83 percent of Russian-speakers, 97 percent of Albanians and 88 percent of Hungarians) were enrolled in native language education; however, some minority parents chose to enroll their children in majority-language classes. Most likely because they would like to ensure better career prospects for their offspring.

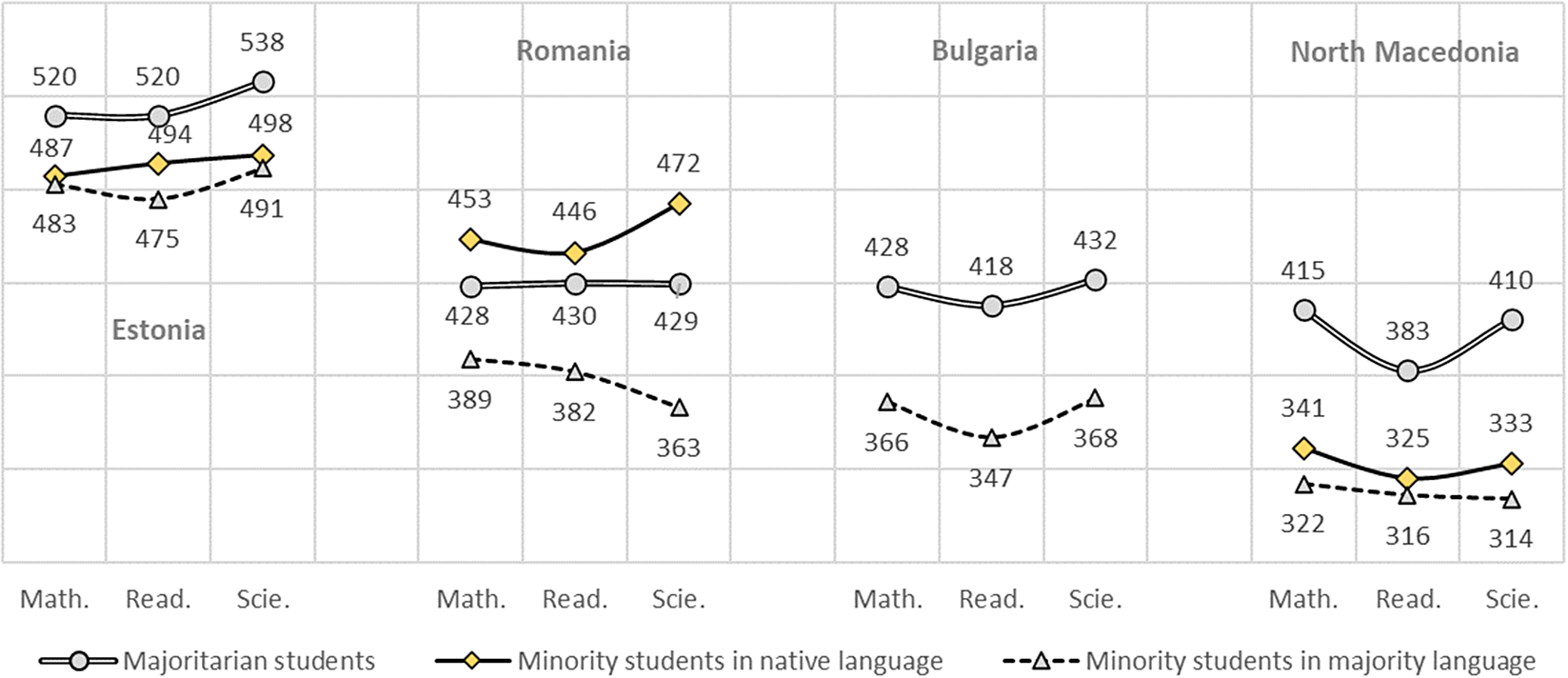

Enrollment in majority language education involves a rather high price in terms of academic performance, however. In all our cases, except Estonia, the so-called “sink or swim” approach is applied to minority children opting for majority language education, meaning that their special educational needs are not taken into account, the educational process completely lacks inclusive and intercultural elements and externalizes all the costs of adaptation to minority families, thus leading to significant disadvantage of minority students during their academic carrier. According to PISA results, they underperform both their majority fellow and minority counterparts enrolled in native language education (Figure 8). According to our linear regression analysis, there is a causal relationship between language used at home and academic performance. Although in the case of Bulgaria, this effect became somewhat weaker, it remained significant in all cases even after controlling the effects of settlement size and economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS)Footnote 24 (Table 5).

Table 5. The effect of language spoken at home and language of tutoring on performance in mathematics in Bulgaria, Estonia, North-Macedonia and Romania according to PISA 2022 results (country level linear regression models)

Source: 2022 PISA database.

Figure 8. 2022 PISA results in Estonia, Romania, Bulgaria and North Macedonia by the language spoken at home and the language of instruction.

Source: 2022 PISA database.

Estonia seems to be the only partial exception because the assessment results of Russian-speakers learning in the majority language are not only closer to that of their majority counterparts but, according to regression analysis, are above that of Russian-speakers learning in their mother tongue. As already mentioned, in this country, several schools have introduced early and late immersion programs to provide transitional bilingual education for Russian speakers. This approach differs significantly from submersion-type majority-language education that characterizes the CEE region. Obviously, transfer to the majority language, even if in a gradual manner, might undermine the cultural and linguistic reproduction of Estonia’s Russian-speaking minority; nevertheless, it seems to reduce the personal costs of integration/assimilation and, consequently, provides more equitable education.

As for minority students learning in their native language, results differ significantly among the three countries we examined (Figure 8). In Estonia, Russian speakers slightly underperform their titular peers, and these differences persist even when we control for the effect of ESCS. Previous analyses suggested that this tendency is related to the consecutive waves of the “educational reform” and the discriminatory and/or unprepared manner of their implementation (Khavenson and Carnoy Reference Khavenson and Carnoy2016). In the Republic of North Macedonia, the PISA results show that the country is still far from providing education of equal quality to Albanian students. The gap between majority and minority students is even larger than that in Bulgaria, where minority students are enrolled in language submersion education. Hungarian students in Romania are the only ones among our cases who outperform their majoritarian counterparts in mathematics, reading, and science. Assessment results show a valuable aspect of Romanian educational policies, as well as an important achievement of Hungarian elites and educational personnel.

Summary

Although it would be an indispensable tool in monitoring international conventions and multilateral treaties such as FCNM, ECRLM and ECRI, and in performing minority rights advocacy, no systematic comparative analysis of minority education in Central and Eastern Europe is available. Our article took a step toward this direction by offering a conceptual framework for such an analysis and providing four illustrative case studies to prove its usefulness. The most important elements of the framework we propose are the following:

First, a comparative analysis of minority education should focus on educational equity that, in the case of linguistic minorities, is strongly connected to both distributive processes (individual opportunities of social mobility) and cultural recognition. Without recognizing the linguistically and culturally rooted educational needs of minority students, educational systems cannot be perceived as equitable. The so-called “sink or swim” approach aiming at language submersion is conducive to lower academic performance of minority students, thus systematically marginalizing them and undermining their well-being. Our illustrative case-studies and PISA results concerning minority students enrolled in standard majority language classes showed that neither Central and Eastern Europe is an exception in this respect.

Second, the tradeoff between distributive outcomes and identity reproduction cannot be taken for granted, but their relationship should be investigated empirically through a model that focuses on interrelations between these elements. Our article proposed such a framework, also arguing that education should be analyzed as part of larger institutional and discursive settings defining interethnic relations. From this perspective, minority education cannot be understood on its own but only as part of minority policy regimes or macro-approaches of diversity management employed by each state. Our article offered a fourfold typology defined along two axes, namely, whether states provide equity/substantive equality for minority group members and whether they promote the reproduction of group identities. We argued that each of the four macro-approaches, integration, accommodation, assimilation, and ethnic hegemony/dominance, tend to be coupled with certain educational policies concerning school curriculum, language of instruction, institutional design, and participation of minorities in decision-making. The four illustrative case studies were selected in order to show how these macro approaches shape educational policies, how they affect educational equity, and how they reproduce or alter ethnic inequalities.

Third, a systematic comparative analysis of minority education in CEEs should rely on a historical institutional approach. Although in this article we did not provide an exhaustive analysis of our cases from this angle, we took a diachronic perspective and, by reviewing changes in national legislations following the regime change, we tried to identify the major historical junctures of the legal-institutional processes. Further research is needed to show why political elites opt for different macro-approaches and educational policies and how these approaches are consolidated. Nevertheless, our illustrative case studies showed that changes are rather significant and are far from being unidirectional. In Estonia, a linguistically separate education has changed to a more integrated one. Later, in the context of securitization, the assimilationist approach prevailed. In the Republic of North Macedonia, a regime of ethnic control/dominance was changed to accommodation, and Romania also took steps toward accommodation, although more cautiously. It was only in Bulgaria that no significant change has occurred in minority education, in spite of the Bulgarian rhetoric of “restoring minority” rights. The case studies also show that regime change cannot be taken as a starting point without any consideration and that, in some cases, continuity of minority education between political regimes might be characteristic.

Fourth, in order to investigate educational equity, a more holistic approach is needed, and diachronic analysis of legal and institutional changes should be completed with statistical analysis of distributive outcomes. At a conceptual level, we relied on de facto discrimination, focusing exactly on cross-group differences of distributive outcomes. This focus is indispensable when evaluating institutional processes from an equity perspective. At an empirical level, relying on international student assessment databases seems to be rather promising. PISA, for instance, is a highly legitimate tool for measuring educational inequalities and offers comparable data for linguistic minorities in CEEs. As already mentioned, data show that students enrolled in majority classes lag far behind their titular peers and why the performance of minority language students enrolled in native language education varies from country to country. Hungarians in Romania represent the only case where minority students overperform their majority language-speaking fellows. However, neither of these performances is enough to prevent the marginalization of young Hungarians because of their poor Romanian language results in official examinations, unequal access to tertiary education, and, as an ultimate factor, lack of official bilingualism.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Annamária Biró and Evelin Verhás for their support and guidance and Zsuzsa Csergő and the two anonymous reviewers for their empathetic reading and valuable comments.

Financial support

Our comparative analysis was made possible by the financial support provided by the Tom Lantos Institute.

Disclosure

None.