Patriotism in Putin’s Third Term

Much has been written about the Russian government and media’s preoccupation with discussing and shaping ideas of national identity during Putin’s third presidential term. In this article, I seek to contribute to the discussion by arguing that the Russian government’s shaping of patriotic discourse, and efforts at legitimation, involved utilizing history to assimilate and co-opt representations of ostensibly bottom-up everyday nationalism into their production of banal nationalism. I define everyday nationalism as how nationalism is represented and reproduced at the grassroots level through everyday activities.

This article focuses on (pro-)government patriotic discourse from 2012–2018; following the 2011–2012 Bolotnaya protests against Putin and Edinaya Rossiya, the government moved toward conservatism and embraced illiberal values-based discourses of legitimacy (Sharafutdinova Reference Sharafutdinova2014). Arguably, the government’s shift towards patriotic and nationalist discourse emerged in response to the protests, and the failure of Vyacheslav Surkov’s notion of “managed democracy” that they represented, as well as the undermining of the “social contract” between the Russian people and the ruling elites (Teper Reference Teper2016). This shift both contributed to and was exacerbated by increased tensions with the West relating to the so-called “gay propaganda law,” the Pussy Riot affair, and the Magnitsky Act. However, these events were soon overshadowed by Russia’s response to Ukraine’s Maidan Revolution in February 2014, which escalated into the annexation of Crimea, the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 (MH17) by Russian-backed rebels, and the imposition of sanctions. In September 2015, it was followed by a similarly consequential event when Russia intervened militarily in the Syrian civil war.

To trace how the government (and supportive media) connected history with everyday patriotism, I first explore how politicians underlined the importance of historical memory to Russian national identity, even securitizing historical interpretation. Second, I consider how history was rendered an everyday concern by examining the conflation of current events with past triumphs and traumas. In particular, I analyze how the government and media used coverage of the Ukraine Crisis, sanctions, and the Syrian conflict as an opportunity to present and promote patriotism. Using framing analysis of pro-government Russian media coverage of these events, I argue that a pervasive sense of historical narrative accompanied these three defining moments in post-Soviet Russia’s relations with the West and understanding of itself. The Russian media interpreted each event through a cyclical notion of history, turning contemporary issues into a direct reliving of past episodes of patriotic history that required Russia to reassume a mantle of past greatness.

This emphasis on replaying a heroic Russian past (e.g., the Great Patriotic War, post-1945 Soviet leadership) through the present facilitated the government’s argument that Russia was witnessing a rebirth of patriotism and awareness of its cultural worth. Thus, historical framing was a means of harnessing the emotional power of these cultural memories for political legitimacy. It was also pivotal to the government and pro-government media’s co-opting of everyday nationalism. In the penultimate section, I examine how the government and friendly media outlets used apparent examples of everyday patriotism to depict ordinary Russians as undergoing a groundswell of patriotism, spurred by historical awareness. While some examples explicitly included an element of historical awareness, historical framing’s conflation of the government’s actions with (alleged) historical precedents meant that, by showing support for government policy, one implicitly also showed one’s “correct” (i.e., Kremlin-aligned) understanding of history.

Banal and Everyday Nationalism

Although I examine the government and state-aligned media’s discursive models, traditionally seen as a top-down approach, this study is relevant to everyday nationalism in that I focus on how the government and media managed depictions of everyday nationalism. In so doing, I connect banal and everyday nationalist approaches by drawing attention to the state’s stake in encouraging Russians to enact its version of patriotism in the latter’s daily lives (or at least in convincing them that this was happening).

The roots of everyday nationalism as a sub-field date to Michael Billig’s efforts to shift attention from the traditional concern of nationalism studies with the emergence of the phenomena of nations and nationalism (Billig Reference Billig1995) to the reproduction of nationalism in everyday life and mass culture (Edensor Reference Edensor2002). However, the continued focus on top-down approaches to constructing the nation led to a distinction between studies of “banal nationalism” and analyses of everyday nationalism, which examined how people consume and (re)construct nationalism from the bottom up (Antonsich Reference Antonsich2016; Skey Reference Skey2011). Eleanor Knott (Reference Knott2015) supplies a thorough overview of the development of everyday nationalism into a sub-field that focuses on ordinary people and their agency in the reproduction of nationalist symbols.

There have been numerous studies of everyday nationalism in the Russian context (Kosmarskaya and Savin Reference Kosmarskaya, Savin, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016; Pilkington Reference Pilkington2012; Ruget Reference Ruget2018); however, most of these works have focused on ethnic minorities or local identities rather than the Russian (russkii) ethnic majority or pan-Russian identity (rossiiskii). Paul Goode and David Stroup discuss how everyday nationalism’s overemphasis on ethnic minorities (Goode and Stroup Reference Goode and Stroup2015) diverted attention from studying nationalism in the Gellnerian sense of “a doctrine of political legitimacy” (Gellner Reference Gellner2008), an issue I seek to address in this article by examining how the methods employed by the government and media could be interpreted as legitimacy-seeking activities.

Recent studies of Russian nationalism have unsurprisingly paid great attention to patriotic rhetoric, activities, and interventions in Putin’s third term (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2018; Kolstø and Blakkisrud Reference Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016, Reference Kolstø and Blakkisrud2018; Roberts Reference Roberts2017). Although the Ukraine Crisis in 2014 had a dramatic impact on the increase in nationalistic and patriotic rhetoric, the government had begun its rhetorical shift toward issues of identity somewhat earlier; for example, President Putin began his third term by presenting Russian identity as under threat from internal and external enemies (Putin Reference Putin2012). Many scholars have underscored the importance of history and nostalgia to this securitized political discourse in the later Putin era (Becker Reference Becker, Resende, Budryte and Buhari-Gulmez2018; Walker Reference Walker2017; Boele, Noordenbos, and Robbe Reference Boele, Noordenbos and Robbe2019; Gaufman, Reference Gaufman2017). Such an interest reflects the media and government’s intense “political use of history” (Kangaspuro Reference Kangaspuro and Elina2011) to color interpretations of the present during Putin’s third term, with Todd Nelson (Reference Nelson2019) even describing how history performs ideological functions in contemporary Russia.

This preoccupation with history existed alongside an increased commodification of patriotism across the population (Digital Icons Reference Icons2017) and a considerable growth in patriotic movements, especially those aimed at children (Sanina Reference Sanina2017; Dahlin Reference Dahlin2017). However, if previously the government encouraged people to demonstrate their national identity in a way that legitimized the derzhavnost’ (the idea of Russia as a great power) worldview (Sanina Reference Sanina2012), in Putin’s third term the state and pro-government media placed increasing emphasis on how citizens were developing this historically aware patriotic instinct from the grassroots, a topic I explore in this article.Footnote 1 While this did not mean that the for-show (pokaznoi) patriotism of Victory Day was abandoned, it did suggest that the government and media were managing and appropriating grassroots patriotic tendencies. In so doing, the government sought to harness and politicize the legitimacy inherent in ordinary patriotic activities, which have tended to be apolitical in the Russian context (Goode Reference Goode2016).

Ostensibly mundane, a performative element was apparent in most of the patriotic activities covered by the media. Ilya Kukulin described such behavior as a form of active conformism, which “functions as a performative example of correct public behavior” (Reference Kukulin2018, 228). These demonstrations of patriotism built on the performative culture that had grown under Putin, particularly in the sphere of public memory (Oushakine Reference Oushakine2013; Wood Reference Wood2011). It also borrowed from Soviet media traditions of depicting collective loyalty to the state by matching representations of social unity with “a manifest reality” of participation (Platt Reference Platt2016, 3). By examining the approaches used to project these activities, I will explore how the government co-opted and curated examples of everyday nationalism to make them correspond to their banal nationalist messages.

Methodology

Given the significance of historical references in political discourse, I focus my efforts onto how historical memory was used by the government to project an image of a good or true Russian patriot. I then demonstrate how history was rendered an everyday reference point, conflated with current affairs for the purposes of legitimizing the government’s policies and co-opting the patriotic energy inherent in supporting or protesting the historical episodes invoked.

In delineating these arguments, I have sought to answer two research questions:

-

1. How did the government emphasize the importance of history and historical memory in their discursive construction of patriotism?

-

2. How did the government and state-supportive media render historical interpretation an issue of everyday patriotism? How was this conveyed?

To answer the first question, I conducted a qualitative reading of documents and transcripts published on Kremlin.ru between 2012 and 2018 and in the Ministry of Culture’s annual reports, which detailed efforts to promote Russian patriotism, as well as interviews with Vladimir Medinskii (Minister for Culture) between 2012 and 2017, from various sources.Footnote 2 I then conducted a qualitative content analysis of the references to Russian identity or patriotism to find keywords or ideas that emerged repeatedly. In particular, I paid attention to equivalence framing, whereby patriotism is defined as a concrete action or belief (Cacciatore, Scheufele, and Iyengar Reference Cacciatore, Scheufele and Iyengar2016). To illustrate my finding that familiarity with a certain interpretation of history functioned as evidence of patriotism, I provide examples from these documents and interview transcripts. This affords insights into the type of examples used, although it does not provide a comparative approach, to compare whether history was cited more or less than other patriotic elements.

To consider how the government and state-supportive media made history an everyday reference point, I first analyze how the government and pro-government media utilized historical framing to present current events within supposed historical analogies, with the latter functioning as the historical schema (or point of comparison). To identify historical framing, I conducted qualitative content analysis of potentially contentious political events from 2012–2018, using the first ten days of pro-government media coverage.Footnote 3 In this analysis, I attempted to identify repeated references to historical events, whereby the current event was conflated with a supposed historical precedent. I succeeded in identifying this historical framing only in the coverage of the Ukraine Crisis, the imposition of third-wave sanctions, and military intervention in Syria. Consequently, I continued frame analysis of each article, broadcast, and piece relating to the current event for a 100-day period, starting from the beginning of, or from an important turning point in, media coverage of the event. This provided ample research material, although sometimes the narrative ended before the 100-day period (Syria) or extended beyond it (Ukraine and sanctions).

I selected the following government and media sources for my frame analysis: Vesti nedeli, Voskresnoe vremya, Komsomol’skaya pravda, Rossiiskaya gazeta, Lenta.ru, Argumenty i fakty, Kremlin.ru, and Mid.ru.Footnote 4 I chose the first six sources due to their large audience reach (Poluekhtova Reference Poluekhtova2015; Khvostunova Reference Khvostunova2013) as well as their close relationship to the government. These sources are either owned by the government or have an owner who is closely connected to the government. Until 2014, Lenta.ru was editorially independent of the government, but the editor-in-chief was sacked as a result of their coverage of the Ukraine Conflict (Fredheim Reference Fredheim2016). Although all (eventually) supported the government, the sources do vary in style; for example, Komsomol’skaya pravda is a tabloid, whereas Argumenty i fakty is more considered in tone. The Mid.ru and Kremlin.ru websites are the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and Presidential Administration websites, selected to represent purely political discourse. In selecting sources, I did not include opposition news coverage, as I was focused on state-supportive media. I also avoided social media because of issues of scope, an interest in analyzing state-supportive media (the RuNet was much freer in this period), and research suggesting that the RuNet is highly impacted by narratives in federal news (Cottiero et al. Reference Cottiero, Kucharski, Olimpieva and Orttung2015).

Analyzing over 8,000 news pieces over two years, I identified one historical episode that functioned as the schema (or point of comparison) for each discourse (Ukraine, sanctions, and Syria) and then gathered all references that conflated the current event with the historical schema. Here, “reference” is used to denote a conflation or comparison of the historical and present-day event. I adapted the framing analysis approach used by Mark Miller that is based on the idea that frames are constructed through the strategic use or omission of certain words and phrases (in my case, ones that compared the contemporary event to a past one) (Miller Reference Miller1997). However, to ensure I did not miss more nuanced references, I employed manual textual analysis, collecting all references within a large spreadsheet. I then adapted a methodology used by Bruce Etling et al. in their analysis of the Russian blogosphere, applying a similar cluster technique to group references by keywords and phrases, thus delineating the frame’s development over the 100-day period (Etling et al. Reference Etling, Alexanyan, Kelly, Faris, Palfrey and Gasser2010).

This historical framing analysis illustrated that the media, like the government, was promoting a view of patriotism that emphasized a particular understanding of current political events and key historical episodes. Moreover, it showed a practical way in which the government and media rendered history an everyday concern by juxtaposing history to events that were a major contemporary topic of discussion. In theory, this should have allowed the government to derive political legitimacy from their political use of history, as they and the media could harness the emotive power of, for example, the Great Patriotic War, ascribing it to the Ukraine Crisis to color audience’s interpretations of the government’s reaction to events there.

Given the conflation of past with present and the everyday representation of history in media and political discourse, I also wanted to examine how the media and government sources depicted such historically informed everyday patriotism outside the purely discursive realm. To do so, I examined the way in which the media supplemented their historical framing of current events with depictions of ordinary people performing patriotism in a way that demonstrated awareness of history and support for government policy. I identified these practices during my framing analysis of the sources’ coverage of Ukraine, sanctions, and Syria. I counted such representations as any nonpolitical or nonstate actors, presented as members of the public, expressing an active response (that was aligned to the government’s view of current events and history) to the political event being covered. Through this final method, I aim to show how the media encouraged audiences to practice, and so realize, the historically preoccupied definitions of patriotism provided by the government as well as to demonstrate support for government policy.

Using History to Paper Over the Discursive Cracks

In 2012, President Putin announced that strengthening national consciousness would be a national priority while also acknowledging the need for Russians to refine their definition of Russian identity (Russia 2012). The Russian idea, or what it means and should mean to be Russian, has long been the topic of heated debate and disagreement, from the Russian empire through to the present day (Seton-Watson Reference Seton-Watson2017; Riasanovsky Reference Riasanovsky2005; Billington Reference Billington2004). Conceptualizations of Russian identity between 2012 and 2017 borrowed from several of these traditions simultaneously and contradictorily; for example, the Russian media, especially Vesti nedeli, readily combined references to Catherine the Great, Stalinism, and the Great Patriotic War in single episodes when covering events in East Ukraine (Poslednie Novosti Reference Novosti2015; Vesti nedeli s Dmitriem Kiselevym 2014b).

In his third presidential term, Vladimir Putin placed great importance on the role of a shared history in maintaining a healthy society. Emphasizing the pivotal role of historical memory in building Russian society, he explained the power of historical memory: “Historical memory is the most important component of our culture, history, our present […] And our future will be made with reference to these historical experiences” (RT na russkom 2014a). In this quotation, President Putin placed historical memory at the forefront of what it means to be Russian, making any national development dependent on remembering the past. The National Security Strategy contained similar claims: “The basis of the general Russian identity of the nations of the Russian Federation is the system, established through history, of united spiritual, moral, and cultural and historical values” (Prezident Rossii Reference Rossii2015). The values from the above quotation were defined in terms that grounded them very firmly in history, which was stressed as the source of unity: “The historical unity of the nations of Russia is the continuity of the history of our Motherland” (Prezident Rossii Reference Rossii2015).

Similar sentiments also emerged in other government documents and reports, such as the 2015 annual report for the Ministry for Culture, which justified and detailed the Ministry’s activities as well as discussing the meaning of Russian identity: “A clear position has been formulated with respect to the identity of Russian (rossiiskogo) society, in which respect for the heroic past […] has played the part of a unifying strength” (Ministerstvo kul’tury 2015, 155). History is presented as the source of unity and, as such, the source of national identity, cohering disparate peoples around a shared interpretation of the past. Evidently, this is not an academic understanding of history but one centered on mythologized historic episodes, be they “heroic,” as above, or traumatic “historical ruptures and the most difficult experiences that have befallen Russia,” as referenced in Putin’s 2018 address to the Federal Assembly (Prezident Rossii Reference Rossii2018).

As such, the government encouraged and promoted a set “correct” view of history (and of history’s relevance to current events). A correct version of history already implied a tacit disapproval of non-government-aligned views of history as incorrect, but there were also more explicit, moralistic condemnations, as in the words of the Minister for Culture (Vladimir Medinskii), who argued that, if your son tells you he read a different version of history to the Russian one, “you need to explain to him that there is good, and there is evil, ideally through your own example” (Rossiiskaya gazeta 2015). The quasi-religious tone of the language contributed to delegitimizing the idea that a good Russian could interpret Russian history differently from the government’s set narrative of approved historical interpretations (what I term its “cultural historical standard narrative”). By extension, one’s understanding of current events and one’s understanding of history reverberated onto one’s patriotism and right to belong (Brusnev Reference Brusnev2015; Grachev Reference Grachev2015; Arsyukhin Reference Arsyukhin2014; Vesti nedeli s Andreem Kondrashovym 2014, 34:00).

Given the above and the political importance placed on a united historical memory, politicians had harsh words for those who challenged state-approved versions of politics and history too openly. They were accused of the worst form of treachery. Vladimir Medinskii’s commentary on those who identified factual inaccuracies in Russian historical myths exemplified this divisive approach: “In fact, they are not very different from the Nazi collaborator Sviridov, who betrayed [Zoya] Kosmodemyanskaya to the Germans. As everyone knows, the Germans saved their thirty pieces of silver because they rewarded him with a bottle of moonshine for that. I hope he burns in hell! Just like those who spread doubt about or dig around and try to disprove the achievements of our ancestors will burn in hell” (BBC Russian Reference Russian2016). This hyperbolic diatribe reflects the lack of acceptance of other views and the securitized treatment of history, whereby voicing alternative opinions was presented as a threat to Russia comparable to collaborating with the Nazis.

In important political documents, disagreements over history were portrayed as geopolitical struggles, with talk of “brigades” to describe Russia’s struggle against alleged falsifiers of history (Lenta Reference Lenta2015a). The notion that people were trying to falsify Russian or Soviet history contributed to the narrative that there was an urgent need to preserve state-approved memories. This militarization of historical interpretation also featured in the Russian information warfare doctrine released at the end of December 2016. The doctrine explicitly connected supposed historical falsifications of Russian military history with current defense policy, describing as a main aim “the neutralization of [hostile] activities in the information and psychological realms, including those aimed at tearing apart the historical foundations and patriotic traditions linked to defending the Fatherland” (Rossiiskaya gazeta 2014). The text implied that an assault on history was an assault on the very foundations of the nation, once again justifying the shrill and intensive invocation of history in political discourse.

The treatment of historical interpretation as a security matter reinforced the importance the government afforded historical memory in their descriptions of patriotism. However, defining patriotism through such nebulous concepts as historical memory or historical truth could have been too abstract an approach. To make such concepts more relevant and persuasive, history would need to be rendered a topic of everyday discussion—hence, the media and government websites’ use of historical framing.

Historical Framing

The media and government websites’ historical framing of major events contributed to rendering history an everyday reference, of direct relevance to events happening at that time. Thus, it supported and reinforced the historical preoccupation found in the government’s discussions of Russian identity (whether this was planned or not). Rather than the sometimes vague invocations of history found in the previous section, historical framing explained complicated current crises by interpreting them through specific and time-limited alleged historical precedents. This process emerged in coverage of contentious events that could pose a risk to regime legitimacy—for example, coverage of the Maidan anti-corruption protests in Ukraine, which some could easily have interpreted as relevant to the Russian political situation. I found repeated comparisons of selected historical events with the Ukraine Crisis, sanctions, and military intervention in Syria while conducting qualitative content analysis (with some quantitative elements, such as counting of terms) over 100-days, collecting all references that compared the present event with a past one. Table One provides an overview of my key findings.

Table 1. Overview of historical framing narratives.

* This denotes the number of references to the historical frame.

Table One provides an overview of how the narrative was used based on findings from my analysis of all the sources; however, as Figures One, Two, and Three show, there were differences in the extent to which the sources utilized the historical framing narratives. The variation in the sources’ use of the frame reflects that the narrative was far from uniform: different sources applied it in different ways. This suggests that the media sources were not simply government mouthpieces but tailored the government’s message to their audience.Footnote 5

Figure 1. Sources’ use of the historical frame in coverage of the Ukraine Crisis. Source key for Figures One through Three: KP (Komsomol’skaya Pravda); RG (Rossiiskaya gazeta); Gov (kremlin.ru and mid.ru); VN (Vesti nedeli); VV (Voskresnoe vremya); AIF (Argumenty i fakty); Lenta (Lenta.ru). The unusually low number of references by Lenta.ru can be explained by the sacking of the editor and other senior journalists in March 2014 as a result of their coverage of events in Ukraine, which had angered the Russian government.

Figure 2. Sources’ use of the historical frame in coverage of the imposition of third-wave sanctions.

Figure 3. Sources’ use of the historical frame in coverage of military intervention in Syria.

A detailed investigation of each source’s use of historical framing and each individual historical framing narrative lies beyond the scope of this article. However, I will review some typical examples to illustrate how the historical framing discourses functioned, especially in relation to their depiction of patriotic actors and the government. In the case of the Ukraine Crisis, which pro-government media sources conflated with the Ukrainian experience of the Great Patriotic War (Voskresnoe vremya s Iradoi Zeinalovoi, 2014 58:00; RT na russkom 2014b; Bas Reference Bas2014), pro-Russian separatists were characterized as heirs to the Red Army. In the sarcastic words of Igor Strelkov, a military commander in East Ukraine, “My grandfather was here in Krasnoarmeisk, fighting to get out of the encirclement for a week in February 1943, defending his country and his people. But, of course, I’m the aggressor” (Bas Reference Bas2014).

By contrast, those who supported the aims of the Maidan protestors were depicted either as Nazis or as the equivalents of the Ukrainian nationalists of the 1940s and 1950s, many of whom had collaborated with the Nazis. Journalists and politicians referred to the threats facing Russian speakers by (alleged) Ukrainian nationalists: “The “black hundreds” […] [are] destroying property, beating and humiliating those who do not support the fascist regime and do not pronounce banderite slogans. This is a repeat of the fifties (the height of the debauchery of the banderite underground in the post-war years of the 20th century– Ed.)” (Latartsevii Reference Latartsevii2014). Likewise, another source comments that “it was already pretty clear to everyone what the ideological heirs to Bandera, Hitler’s helper during World War Two, intended to do in the future” (Prezident Rossii Reference Rossii2014). Such comments were typical of the complete elision of different time periods, a technique that emphasized the threat posed by the repetition of traumatic episodes of history. Coverage also abounded in hyperbole, as with Ul’yana Skoibeda’s article decrying pro-Maidan Ukrainians as mere extensions of the Nazis, which described Kyiv streets “covered in swastikas” and with “destroyed Jewish shops” (Skoibeda Reference Skoibeda2014). Vladimir Putin supported such narratives when he declared that “Crimea will never be Banderite!” (Prezident Rossii Reference Rossii2014).

Following the descent of the Ukraine Crisis into war and the downing of MH17, Russian media portrayed the imposition of harsher sanctions by the EU and USA (and some other countries) as an attempt by the latter to humiliate Russia (as in the 1990s) or even destroy it as a state (as allegedly with the USSR in the 1980s): “The USA continues to realize its geopolitical doctrine for Russia, which is known by the name “Anaconda.” The first snake loop tightened when they destroyed the Warsaw Pact, the second when they destroyed the Soviet Union” (Boiko Reference Boiko2014).

As in the Ukraine Crisis discourse, the media connected these emotive memories to the idea of a fifth column working inside Russia for the interests of other states: “Today’s “fifth column,” working inside Russia in the interests of the USA and other Western countries […] is a loose conglomeration, made up of different parts. The first part comprises those same bankrupt politicians of the 1990s who made their career precisely when Russia was in decline and who now dream of returning to this period” (Mironov Reference Mironov2014). Such comments reinforced the notion that disagreeing with government policy was deeply unpatriotic and, by extension, that diverging from the government view of the 1990s also made one’s loyalties suspicious. This reflected the seemingly dual purpose of historical framing to conflate both the past with the present and one’s view of the past with one’s interpretation of present political events. In this case, the author was exploiting memories of the difficult 1990s to delegitimize criticism of the government response to sanctions and Western criticism.

Thus, Vladimir Putin’s decision to impose countersanctions on EU and US agricultural produce and implement a policy of import substitution was characterized as resistance to alleged Western attempts to replay the economic troubles of the 1990s and collapse of the USSR. This defiance facilitated a metaphorical return to the stability of the Brezhnev era (Tseplyaev Reference Tseplyaev2014; Lenta Reference Lenta2014), as reflected in the following quotation that sought to elicit the views of ordinary people: “In Soviet times, we had 500 hectares, but we only have 100 left. You can see even those aren’t being used. But now [after countersanctions] there’s a chance to restore all that” (Ovchinnikov Reference Ovchinnikov2014). One commentator declared their support for the policy of import substitution by arguing that “nothing bad will happen if we take all the good things from the USSR because there were a lot of good things, more good than bad” (Lenta Reference Lenta2014). In this way, the media presented agreement with a government policy as akin to rejecting the repeat of a traumatic memory for many Russians (the collapse of the USSR) and allowing a return to an imagined era before the collapse.

The media also applied historical framing to the Syria conflict, although in most sources the tone was more self-confident and messianic in comparison with the two 2014 discourses described above. This was reflected in the media’s use of the early Cold War years, including the USSR’s post-1945 global prominence, as the historical schema through which to interpret Russian military intervention and alleged American aggression (Argumenty i fakty 2015; Prezident Rossii Reference Rossii2015a; Voskresnoe vremya s Iradoi Zeinalovoi, 2015, 55:00). Such nuances were especially evident in discussions of the USA’s disagreements with Russia over its intervention in Syria: “The military measures taken by the United States are directed at the so-called containment of Russia […] The USA stated that it had no intention of returning to the Cold War times [but] when US nuclear rockets and hundreds of thousands of American soldiers are situated in Europe then these actions initiated by the Americans de facto lead right in that direction” (MID 2015). Comments such as these presented the USA’s reactions to Russian foreign policy as mere continuations of Cold War enmity.

The Cold War was also invoked as a positive historical precedent elsewhere. This was partly because it provided a precedent for superpowers’ ability to communicate even in the middle of the crisis, a comment made in the context of simultaneous US and Russian airstrikes in Syria in 2015: “Surely the military men of both countries can agree to avoid unpleasant incidents, like they did after the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the military of the USSR and USA opened a special red line to prevent nuclear war” (Argumenty i fakty 2015a). Another positive aspect was seen in the media’s depiction of Russia as resuscitating old alliances from the days of the USSR, such as Syria and Cuba (Lenta Reference Lenta2015; Borisov Reference Borisov2015). This more outward-looking representation of Russian identity (as a global leader) built on the notion that Russia’s strength lay in its patriotic awareness of its own past, history, culture, and traditions (Fedyakina Reference Fedyakina2014). Such arguments depicted Russians as providing an alternative force to the West and leading the way for the people of other nations to regain their sense of themselves, their origins, and their history.

As such, through sheer volume of references, historical framing made history, and especially certain historical analogies, an everyday topic of discussion in media and political discourse. The conflation of the government’s current actions with these past triumphs—or the presentation of the government as remedying past traumas—reverberated onto one’s historical understanding: to support the government in Ukraine or Syria was, respectively, to profess a view of history that celebrated the Great Victory or Soviet Union’s great power status. This conflation of one’s view of history with one’s view of political events in the present was central to the government’s media-supported legitimization of its policies. If having the “correct” interpretation of history was presented as necessary for being a patriotic Russian, and if espousing “incorrect” history was deemed a security threat, then this made it difficult to be a patriot and to disagree with the government. This argument is important not only on the level of producing banal nationalism; it also resonates in the practices of everyday nationalism, or at least the depiction of these practices as curated by the media and government websites.

Performing Policy-Specific Patriotism

To further realize the potential for political legitimization provided by political uses of history, the government and media sources also curated and created images of ordinary people actively supporting the government’s policies. Such actions often explicitly involved demonstrating historical awareness. As such, these images presented the Kremlin’s ideal demonstration of patriotism, whereby historical awareness coincided with support for the government. By way of example, Komsomol’skaya pravda detailed patriotic bloggers who called on audiences to support government policies on countersanctions. At the same time, the newspaper underscored how the bloggers “remember the Soviet Union with nostalgia” (Chernyak Reference Chernyak2014), linking the two points. As such, the media supplemented their and the government’s production of banal nationalism (e.g., discussion of patriotism, historical framing) with examples of everyday nationalism as practiced by citizens. 40 percent of articles and broadcasts referencing the historical schema also included evidence of active demonstrations of patriotism and government allegiance. However, this was much higher for the Ukraine discourse (62 percent) and sanctions (49 percent) than for Syria (11 percent). Through this presentation, the media not only provided a template of how to perform patriotism but also led audiences to believe that their fellow citizens were becoming more patriotic in their daily lives (Greene and Robertson Reference Greene and Robertson2017; Robertson and Greene Reference Robertson and Greene2017). As such, the coverage itself was one way the media encouraged demonstrations of patriotism, seeking to make the audience feel less comfortable with not participating, lest they stand out as unpatriotic.

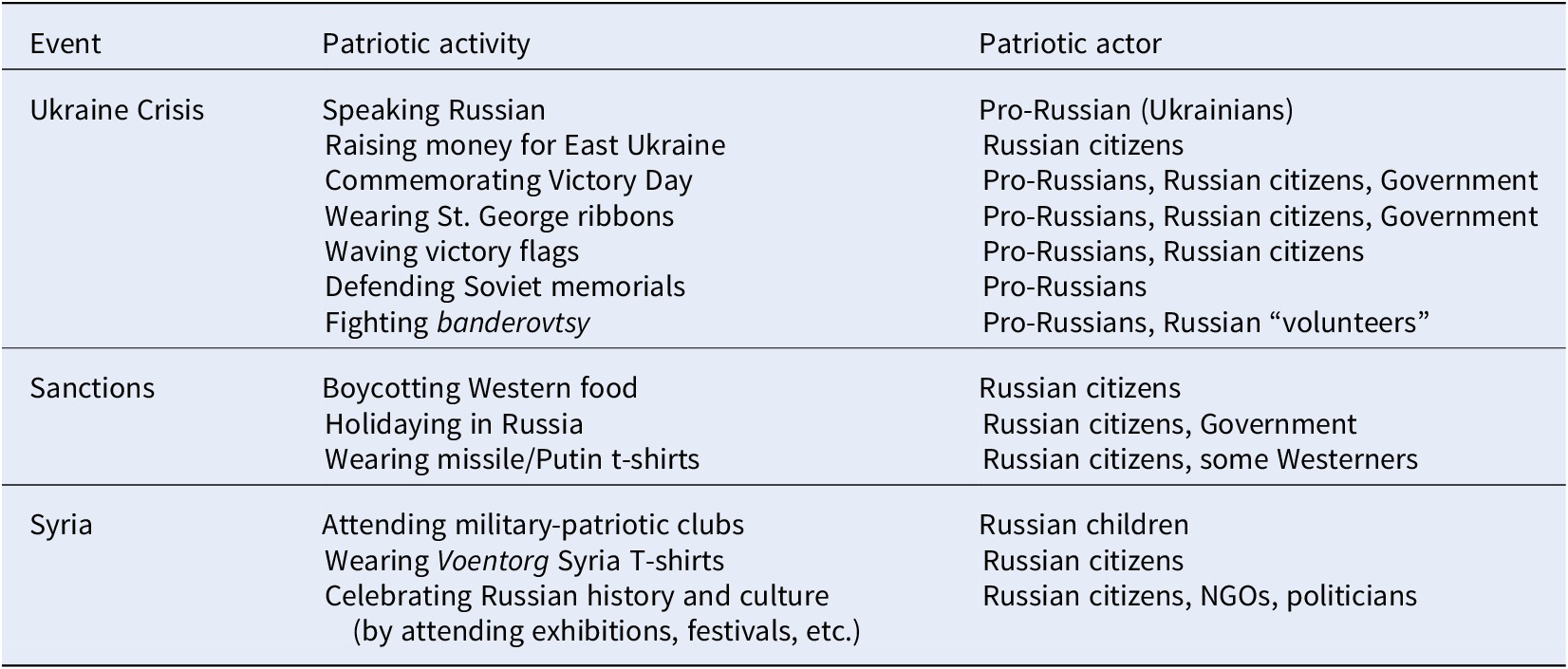

Table Two shows various everyday activities that media sources repeatedly presented as evidence of patriotism and support for government policy within the historical framing discourses. It is far from an exhaustive list as the media were presenting such images of patriotism as examples of individual responses rather than mass identical actions. However, the examples included in Table Two were patriotic activities reproduced across at least ten news pieces in two or more sources during the research period (see Table One). In the case of some activities, such as boycotting Western food or wearing a St. George Ribbon, they were reproduced across hundreds of news articles and broadcasts.

Table 2. Positive patriotic performance in media coverage of the Ukraine Crisis, sanctions, and Syria.

The findings are taken from my framing analysis of media coverage of the three discourses (Ukraine, sanctions, and Syria). In the case of the Ukraine Crisis, these practices were often closely linked to the Great Patriotic War, the event within which Russian media framed the Ukraine Crisis. This had the effect of conflating one’s respect for veterans with one’s position on Ukraine, thus appropriating commemorative practice for political ends (Grishin Reference Grishin2014). However, alongside the repurposing of symbols such as the St. George Ribbon (Poslednie Novosti Reference Novosti2015, 17:33), there were more dramatic examples of demonstrating one’s patriotism, including the media’s glorification of those fighting in Ukraine (Aslamova Reference Aslamova2014; Bas Reference Bas2014a). These more dramatic examples of performing patriotism, while not limited to the Ukraine Crisis, proved the exception rather than the rule.

Instead, there tended to be a projected congruence between ordinary people’s everyday nationalism and the state’s own policies, as was notable in coverage of responses to sanctions. Patriotic boycotts of Western products, and the embrace of domestic products, were presented as the antidote to the decadent 1990s and wild capitalism (Saltykova Reference Saltykova2014; Lenta Reference Lenta2014a). The media and government also accentuated the involvement of Russian citizens in reporting Western restaurants to the authorities and the support of ordinary people for the Russian countersanctions on Western produce: “eighty percent of respondents are confident that the Russian embargo [on Western produce] will work in the country’s favor” (Domcheva Reference Domcheva2014). Thus, methods of resistance to Western symbols reoccurred across the media and were emphasized as grassroots phenomena, creating a sense of camaraderie, as with claims that government officials were replacing their foreign cars with Russian ones (Argumenty i fakty 2014).

Many of the activities listed in Table Two explicitly referenced history. Some of these were obvious, such as with the wearing of St. George Ribbons,Footnote 6 while others were more subtle, such as the boycotting of Western food for its symbolism of the 1990s. For other activities included in the table, there is no explicit historical connection. However, even if there was no explicit reference (e.g., wearing Voentorg T-shirts to show support of government policy in Syria), historical framing had rendered the reference to history implicit within any act of support for the government.

Whether explicitly or implicitly referencing historical awareness, most of the activities in which patriotic actors engaged were mundane and accessible to ordinary people, from eating domestic produce to holidaying at home: “I feel very sorry for people who consider the availability of a wide range of sausages a victory for democracy. What a pity we can’t divide society: on the right, those who want the return of the USSR with all its pluses and minuses; on the left, those who want sausages. Тhe only thing to do with that type of democrat is tell them to leave: it’s a big world [and] there are a lot of countries with sausages” (Skoibeda Reference Skoibeda2014a). In fact, as in the examples above, it was only through media framing that some of the so-called patriotic activities were signposted as such. Most Russians holiday at home and eat domestic produce; by turning the latter into patriotic acts of allegiance with government policy, the media could politicize the apolitical.

This politicization of the everyday had assumed a more comprehensive character by 2015, reflecting a shift in government discourse from a defensive presentation of Russian identity to a more confident, offensive one. This shift toward a more messianic and organized understanding of patriotism focused on forming the Russian fighters of the future through military patriotic clubs, patriotic camps, and so on (Fedotova Reference Fedotova2015; Granina Reference Granina2015). Despite being forward-looking in its orientation toward children, these activities still centered on the past by privileging the teaching of military history and emulation of earlier fighter heroes: “The Soviet education system’s main objective was to raise patriots, ready to defend their homeland. This was its entire purpose […] It’s time we stopped following Western standards and returned to the best traditions of Russian and Soviet schooling (Lenta, Reference Lenta2014). This quotation shows how the media also emphasized the military patriotic element required if Russia was to reassume Soviet greatness.

As noted by Vera Skvirskaja, many of the patriotic demonstrations at this time were highly commodified and commercialized, creating patriotic branding that modern citizens could embrace, like attending exhibitions, wearing vatniki (padded jackets), and consuming salads (Digital Icons Reference Icons2017). The most well-publicized patriotic branding exercise was the marketing stunt-cum-protest by two young entrepreneurs selling pro-Putin T-shirts bedecked with Iskander missiles and mocking the West in 2014 (Khozhaleteva Reference Khozhaleteva2014). In this way, the media encouraged audiences to affirm a certain interpretation of the Soviet Union, 1990s, or the Great Patriotic War by wearing brands and copying heroes held up for emulation. Once successful, these stunts, or aktsii, tended to be repeated across events, such as the wearing and designing of political statement T-shirts during the Syria and sanctions episodes (Ovchinnikov Reference Ovchinnikov2015; Khozhaleteva Reference Khozhaleteva2014, Reference Khozhaleteva2014a).

Such activities and active remembering underscored the importance of patriotic performance in media depictions, which turned the action itself (be it wearing symbols or blogging) into a key aspect of belonging (Novikova Reference Novikova2014; Chernyak Reference Chernyak2014). This prioritization of form over content privileged experience and entertainment above exploration of political fact and was reflected in Putin’s call for “living forms of inculcating patriotism” (Prezident Rossii Reference Rossii2012), namely, a more active approach to patriotism and making it relevant or appealing to people.Footnote 7 As the government had underscored the significance of historical memory to Russian identity, this relevance was (at least partly) dependent on historical framing and the references to history sometimes contained within the patriotic acts themselves. This approach encouraged people to perform the sort of mundane acts of government allegiance described above by presenting them as evidence of contiguity with epic heroes of the past. By rewarding patriotic actors with a flattering historical comparison, the media further incentivized such demonstrations of patriotism.

Conclusion: Why Did the Government Adopt This Approach to Patriotism?

In conclusion, the Kremlin’s vision of patriotism often relied on abstract concepts such as historical truth and memory, with the government positioned firmly on the “right” side of historical interpretation. Through historical framing, the government, along with the media, rendered history an everyday concern and issue of patriotism by conflating it with current events. Through historical framing, the media and government websites also conflated a person’s view of history with their view of government policy and politics, thereby indirectly reducing patriotism to whether a person supported the government, albeit arguably in a manner that was more persuasive than this statement suggests. Moreover, by depicting ordinary people performing their patriotism in a way that implicitly or explicitly demonstrated a level of historical awareness, the media legitimized the government’s actions by creating a sense of resonance between the top-down production of banal nationalism and (allegedly) authentic practices of everyday nationalism.

The centrality of historical interpretation to the media’s discourse and presentations of performed patriotism should be contextualized within the government’s need to emphasize stability in the face of a crashing currency, food sanctions, and a slumping economy. This stability had to be accompanied by a sense of progress, however, to counteract accusations of economic and political stagnation. This was achieved by formulating patriotism as an active process, a type of coming to cultural and historical consciousness rather than ideology. This sense of momentum and dynamism worked as a partial counter-narrative to economic stagnation that also distracted people from seeking other forms of political progress.

The media’s depictions of performed patriotism were presented as organic efforts, organized by ordinary people as a spontaneous reaction to the events they were seeing on their television screens. The claim inferred by this—namely, that large numbers of Russians were demonstratively aligning themselves (often in similar ways) with government policy and its interpretation of history—seems unlikely when viewed against research into everyday nationalism in Russia. Such research has revealed it to be largely apolitical and varied in comparison with government forms of pokaznoi patriotizm (demonstrative patriotism) (Goode Reference Goode2016, Reference Goode, Skey and Antonsich2017, Reference Goode2018). Consequently, it is improbable these images were entirely genuine. Perhaps they should be seen instead as part of a campaign to suggest Russians were demonstrating their patriotism and allegiance with government policy and history.

In their management of everyday patriotism depictions, the media not only curated or covered patriotic activities (creating T-shirts with missiles) but also co-opted normal everyday activities (holidaying in Russia, eating domestic produce) and politicized them, invoking them as examples of patriotic reactions to policies and events. By appropriating apolitical elements of people’s everyday lives, they also made it difficult for people to avoid reproducing these top-down patriotic tropes. Theoretically, this could place ordinary Russians in the difficult position of having to choose whether to accept the co-opting of everyday activities into demonstrations of patriotism, turning the decision over where to holiday or which film to watch into a political act (Argumenty i fakty 2015b; Govorukhin Reference Govorukhin2015). This has implications for the hitherto apolitical nature of everyday patriotism, but it could also create opportunities for people to engage in less overt, more everyday forms of opposition to government policy at a time when the state is restricting the voicing of opposition views.

Disclosure

Author has nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for helping me to improve the article. I would also like to thank my supervisor, Polly Jones, for her comments on the early drafts of this article, and the Editor, Paul Goode, for his support throughout.

Financial Support

I received funding from CEELBAS (the Centre for East European Language Based Area Studies) and from a Santander Fellowship.