Introduction

Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer between 15 and 39 years of age are complex and vulnerable as a result of the intersection of disease and their developmental stage (Kwak et al., Reference Kwak, Zebrack and Meeske2013a). The 15–39 age range is the standard used for AYA by the National Cancer Institute in the United States. AYAs are in various challenging situations related to physical and cognitive development, identity, body image, autonomy, and employment (Husson and Zebrack, Reference Husson and Zebrack2017; Kaul et al., Reference Kaul, Avila and Mutambudzi2017). A diagnosis of cancer could significantly disrupt or delay these aspects of development. Annually, more than 20,000 AYAs are diagnosed with cancer in Japan, most of whom become long-term survivors (>5 years post-diagnosis) (National Cancer Center, 2021). As more survivors reach long-term survivorship, cancer and treatment-related adverse late effects, such as endocrine disorders, cardiovascular disorders, secondary tumors/malignancies, central nervous system/peripheral nervous system disorders, renal disorders, pulmonary disorders, and long-term psychosocial effects, increase and require adequate interventions during long-term follow-up care (Langer et al., Reference Langer, Grabow and Steinmann2017; Hilgendorf et al., Reference Hilgendorf, Bergelt and Bokemeyer2021).

Cancer treatment and late effects can interfere with education or employment plans (D'Agostino et al., Reference D'Agostino, Penny and Zebrack2011), and those concerns might cause greater distress for AYAs with cancer. Research indicates that AYAs with cancer report significantly poorer physical and mental health status than the matched controls (Phillips-Salimi and Andrykowski, Reference Phillips-Salimi and Andrykowski2013), and that young adult cancer patients report more negative psychosocial outcomes than older patients (Stava et al., Reference Stava, Lopez and Vassilopoulou-Sellin2006). However, reports of the prevalence of clinically significant distress among AYAs are inconsistent. According to a review conducted by Sansom-Daly and Wakefield (Reference Sansom-Daly and Wakefield2013), rates of clinical distress among AYAs with cancer ranged from 5.4% to 56.5% depending on sample sizes, age range of samples, timing of data collection, and instrumentation. Clinical levels of distress were variously defined as either meeting criteria for the diagnosis of a mental disorder, or to scoring highly enough or beyond a clinical cutoff score on a particular measure. Previous research on AYAs with cancer shows that greater distress is associated with the female gender, older age, pain, less social support, having late effects, self-image, and identity issues (Hendström et al., Reference Hendström, Ljungman and von Essen2005; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, McNeil and Drew2016; Geue et al., Reference Geue, Brahler and Faller2018; Michel et al., Reference Michel, Francois and Harju2019). Most prevalence and associated factor studies target patients within a year of diagnosis or long-term survivors, and few studies include AYA patients at various time points, from immediately after diagnosis to more than 10 years after diagnosis.

There are three prevalence studies among Asian AYA cancer patients specific to cultural background. Those studies were conducted in China, Singapore, and Korea. They investigated the prevalence of psychological distress by the Distress Thermometer or the Brief Symptom Inventory-18, and the prevalence rates were 20.6%, 43.1%, and 89.1% (Kim and Yi, Reference Kim and Yi2013; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Ding and He2017; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Poon and Goh2018). However, there are no previous studies evaluating levels of psychological distress in AYA patients in Japan.

In order to help clinicians identify who is in need of psychosocial intervention and when to most effectively intervene, it is important to understand the predictors of distress and when distress in AYA patients over the course of cancer treatment is higher. However, the actual state of psychological distress over the course of cancer is not well understood in AYA patients. Therefore, the current study aimed (1) to examine the prevalence of psychological distress among AYA cancer patients within a year of diagnosis to long-term survivors and (2) to describe socio-demographic and cancer-related characteristics associated with psychological distress.

Methods

Participants and procedure

A web-based survey company (Macromill, Ltd.) recruited potential participants out of 10 million registered people across Japan and sent questionnaires to them online over five days in April 2017. Those who live in Japan and are 6 years old or older can register in the database of the survey company, if they wish. However, minors need parental consent. Eligible participants were those with cancer followed in an outpatient clinic and aged 16–39 years old at the time of survey. According to the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects formulated by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan, minors who have graduated from junior high school or are 16 years of age or older can be judged to have sufficient judgment ability regarding the conduct of the study. For these reasons, we set the eligibility age from 16 to 39 years. Potential participants first read introductory statements that summarized the contents of the questionnaire and explained they could withdraw at any time if they wished so. Responses were considered consent to participate. Because the legal adult age is 20 years old in Japan, those who were 16–19 years old were asked to confirm the consent of their parents. Responses to the questionnaire were voluntary, and confidentiality was maintained throughout all investigations and analyses. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of National Center for Neurology and Psychiatry (A2016-123) and was conducted in accordance with the principles laid down in the Helsinki Declaration.

Measures

Psychological distress: The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6)

The K6 scale is a population-based screening measure for psychological distress (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Barker and Colpe2003) and has been extensively validated in diverse populations including adolescents and cancer survivors (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, McCarthy and Recklitis2009; Green et al., Reference Green, Gruber and Sampson2010; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Hartoonian and Owen2010; Vigod et al., Reference Vigod, Kurdyak and Stewart2011). The K6 scale includes six questions regarding how frequently within the past 30 days respondents have felt sad, nervous, hopeless, worthless, restless, or fidgety and that everything was an effort. Responses are rated on a five-point scale ranging from “none of the time” (0) to “all the time” (4); scores range from 0 to 24. High scores indicate greater distress. The validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the K6 have been established (Furukawa et al., Reference Furukawa, Kawakami and Saitoh2008). Those who scored 5 or more were classified as having significant psychological distress (Sakurai et al., Reference Sakurai, Nishi and Kondo2011).

Social support: The short-version Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support measures social support from family, friends, and a significant other using 12 items (Zimet et al., Reference Zimet, Dahlen and Zimet1988). It has been widely used to assess perceived social support for adolescents and cancer patients (Naseri and Taleghani, Reference Naseri and Taleghani2018; Laksmita et al., Reference Laksmita, Chung and Liao2020; Oh et al., Reference Oh, Yeom and Shim2020). The short version consists of seven items (question numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, and 12); “There is a special person who is around when I am in need,” “There is a special person with whom I can share my joys and sorrows,” “My family really tries to help me,” “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family,” “My friends really try to help me,” “I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows,” “I can talk about my problems with my friends.” A 7-point Likert scale is used and a low score for a scale represents poor social support. The validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the short-version Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support have been confirmed (Iwasa et al., Reference Iwasa, Gondo and Masui2007).

Demographic and medical characteristics

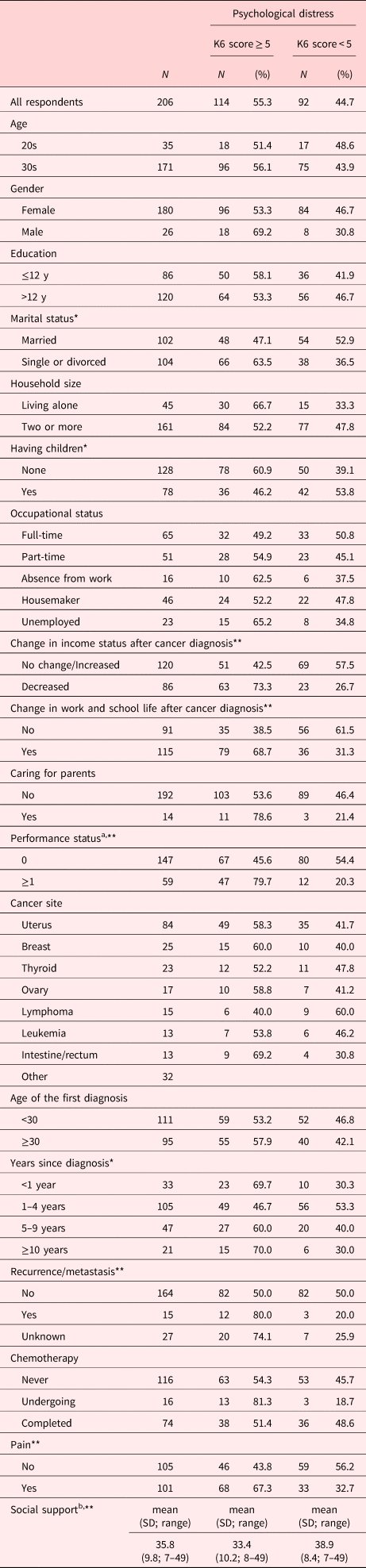

The participants were asked their demographic and clinical information, as listed in Table 1. For cancer diagnosis, duplicate answers were possible. Functional performance status was assessed using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status (PS) scale (Oken et al., Reference Oken, Creech and Tormey1982). The ECOG PS scale measures how the disease affects the daily living abilities of the patient. It is rated on a five-point scale with 0 being “fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction” and 5 indicating that the patient is deceased. Pain was assessed using an item of the EuroQol 5 Dimensions 5 Levels (Ikeda et al., Reference Ikeda, Shiroiwa and Igarashi2015) at the time of the survey. A 5-point Likert scale is used and a high score for a scale represents a high level of symptomatology and problems. In this study, level 1 was categorized as no pain and level 2 or higher as with pain.

Table 1. Patient characteristics and prevalence of psychological distress

K6, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale.

a Defined by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

b Assessed by the short-version Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

Sample size calculations

We planned to perform a multiple regression analysis to examine the factors related to psychological distress, and we calculated that 10 times as many subjects as the number of independent variables would be required (Peduzzi et al., Reference Peduzzi, Concato and Kemper1996). Considering the missing data, the planned number of subjects was 190.

Statistical analysis

First, we applied descriptive statistics. Second, the prevalence of psychological distress among all participants and also among participants within a year from diagnosis, 1–4 years from diagnosis, 5–9 years from diagnosis, and more than 10 years from diagnosis were calculated. Third, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by logistic regression analysis in order to examine association between the time since cancer diagnosis and the prevalence of psychological distress. Fourth, to identify potential demographic, biomedical, and social factors associated with psychological distress, a preliminary univariate analysis was conducted. Demographic and clinical variables and social support were entered as independent variables. For the univariate analyses, an unpaired t-test, a Mann–Whitney test and a chi-square test were conducted, as appropriate. After the univariate analyses, logistic regression was conducted to examine the final factors associated with patients’ psychological distress. Respondents with missing data were excluded from logistic regression analysis. Variables with a p-value less than 0.1 in the preliminary univariate analyses were entered into logistic regression as independent variables. Additionally, we also entered associated factors (sex and age) which were reported in previous research (Hendström et al., Reference Hendström, Ljungman and von Essen2005; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, McNeil and Drew2016; Geue et al., Reference Geue, Brahler and Faller2018) as independent variables. A backward stepwise selection method was used to explore factors related to the psychological distress (Baskaradoss et al., Reference Baskaradoss, Geevarghese and Al-Mthen2019). Data were analyzed with the SPSS version 26.0 (IBM). All the tests were two-tailed, with a p-value of <0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

One thousand and twenty-six cancer patients (75.6%; 776 female) aged between 16 and 39 were registered in the database in April 2017. Two hundred and six responded and completed the survey (87.4%; 180 female). The participants’ median age at the survey was 34.5 years (range: 22–39 years). There were no participants under the age of 20. The cancer diagnoses included uterus cancer (n = 84; 40.8%), breast cancer (n = 25; 12.1%), thyroid cancer (n = 23; 11.2%), ovary cancer (n = 17; 8.3%), lymphoma (n = 15; 7.3%), leukemia (n = 13; 6.3%), intestine or rectum cancer (n = 13; 6.3%), and others (n = 32; 15.5%). Thirty-three (16.0%) were diagnosed within a year, 105 (51.0%) were diagnosed between 1–4 years ago, 47 (22.8%) were diagnosed between 5–9 years ago, and 21 (10.2%) were diagnosed with cancer more than 10 years ago. Sixteen participants (7.8%) were undergoing chemotherapy, and 74 participants (35.9%) had completed it. Mean score of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support was 35.8 (SD 9.8; range 7–49). The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Psychological distress in young adult cancer patients

Mean total K6 score was 6.86 (SD 6.40; range 0–24). One hundred and fourteen (55.3%) of respondents score 5 or higher on the K6, indicating psychological distress. Of the 114 participants, 23 were diagnosed within a year (69.7% of this group), 49 were diagnosed between 1–4 years ago (46.7% of this group), 27 were diagnosed between 5–9 years ago (60.0% of this group), and 15 were diagnosed with cancer more than 10 years ago (70.0% of this group). The prevalence rate was high within a year since diagnosis, and at more than 10 years since diagnosis. Patients at 1–4 years since diagnosis had lower prevalent of psychological distress (OR = 0.38; 95% CI = 0.17–0.88) compared to those who were diagnosed within a year (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for prevalence of psychological distress at the time since diagnosis.

Factors associated with psychological distress

We compared socio-demographic and medical factors between patients with and without significant psychological distress in univariate analyses. The factors that were significantly correlated with the presence of psychological distress were: marital status (single or divorced) (p = 0.018); having children (none) (p = 0.038); change in income status after a cancer diagnosis (decreased) (p < 0.001); change in work/school life after a cancer diagnosis (yes) (p < 0.001); PS (p < 0.001); years since diagnosis (p = 0.041); pain (yes) (p = 0.001); social support (p < 0.001).

Using these significant correlated factors in univariate analysis and the associated factors (sex and age) which were reported in previous research, we conducted logistic regression analysis to identify independent associated factors for psychological distress. The results revealed that pain, change in income status after a cancer diagnosis, change in work/school life after a cancer diagnosis and poor social support were associated with psychological distress (Table 2).

a This model is Step 9 and Nagelkerke R Square is 0.274.

The models from step 1 to step 8 are as follows.

Step 1: sex, age, marital status, household size, having children, change in income status, change in work & school life, caring for parents, PS, years since diagnosis, pain, social support; Nagelkerke R Square: 0364.

Step 2: sex, age, marital status, household size, change in income status, change in work & school life, caring for parents, PS, years since diagnosis, pain, social support; Nagelkerke R Square: 0364.

Step 3: sex, age, marital status, change in income status, change in work & school life, caring for parents, PS, years since diagnosis, pain, social support; Nagelkerke R Square: 0364.

Step 4: sex, marital status, change in income status, change in work & school life, caring for parents, PS, years since diagnosis, pain, social support; Nagelkerke R Square: 0363.

Step 5: marital status, change in income status, change in work & school life, caring for parents, PS, years since diagnosis, pain, social support; Nagelkerke R Square: 0361.

Step 6: marital status, change in income status, change in work & school life, caring for parents, years since diagnosis, pain, social support; Nagelkerke R Square: 0331.

Step 7: change in income status, change in work & school life, caring for parents, years since diagnosis, pain, social support; Nagelkerke R Square: 0321.

Step 8: change in income status, change in work & school life, years since diagnosis, pain, social support; Nagelkerke R Square: 0309.

b Patients who had unknown variables were excluded.

c A low score for a social support scale represents poor social support.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional web-based survey, we observed a high prevalence of psychological distress among young adult cancer patients. Distress among patients diagnosed within a year and long-term survivors (≥10 years since diagnosis) was relatively higher than patients 1–4 years since diagnosis. In the case of adult cancer patients, it is common that psychological distress is high just after bad news, such as cancer diagnosis, recurrence or progression (Okamura et al., Reference Okamura, Watanabe and Narabayashi2000; Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Cornelius and Love2005; Saad et al., Reference Saad, Gad and Al-Husseini2019). However, it is worth noting that our results showed that the long-term AYA cancer survivors had a similar high prevalence to patients within a year of diagnosis. According to a 10-year follow-up longitudinal study among persons diagnosed with cancer during adolescence (Ander et al., Reference Ander, Gronqvist and Cernvall2016), levels of depression and anxiety were the highest at four to eight weeks after diagnosis, and a decreasing level of symptoms of depression and anxiety were shown up to 4 years after diagnosis. The findings also suggested an increasing level of anxiety from 4 to 10 years after diagnosis. Adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer are at risk for late occurring morbidities associated with their cancer and its treatment. Three-fourths of survivors will develop a chronic health condition within 30 years of diagnosis (Oeffinger et al., Reference Oeffinger, Mertens and Sklar2006). Late effects were a major correlate of psychological distress in AYA cancer survivors (Michel et al., Reference Michel, Francois and Harju2019), and poor physical health status was associated with increased risk of suicide ideation in adult survivors of childhood cancer (Brinkman et al., Reference Brinkman, Zhang and Recklitis2014). Lehmann et al. (Reference Lehmann, Gronqvist and Engvall2014) interviewed adolescent cancer survivors 10 years after diagnosis and reported negative cancer-related consequences including frustration about health care, and fertility concerns not reported previously during the disease trajectory. This suggests that survivorship of adolescent cancer is associated with specific challenges. The results indicate a need of long-term monitoring of the physical and psychological health of individuals treated for cancer during adolescence and young adult in order to detect their problems and those in need for psychological support.

Association between pain and higher psychological distress was consistent with the findings of a previous study among adolescents with cancer (Hendström et al., Reference Hendström, Ljungman and von Essen2005). Pain related to cancer or its treatment affects most cancer patients. Many studies on adult cancer patients have shown that pain is associated with psychological distress (Zaza and Baine, Reference Zaza and Baine2002), and point out the importance of pain assessment and adequate management.

Consistent with a previous literature (Geue et al., Reference Geue, Brahler and Faller2018), poor social support was associated with higher levels of psychological distress. A cross-sectional study has demonstrated that AYA cancer patients report greater challenges in social functioning compared with the general AYA population (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Parsons and Kent2013). AYA cancer patients frequently report difficulties in maintaining or making new social relationships because of the long-term effects of treatment or feeling anxious about fitting into their peer group again (Evan and Zelter, Reference Evan and Zelter2006; Zebrack et al., Reference Zebrack, Chesler and Kaplan2010a). Husson et al. (Reference Husson, Zebrack and Aguilar2017) found that AYA cancer patients who had low social functions reported more physical symptoms and higher levels of distress, and perceived themselves to receive less social support. Social support and social functioning are key issues in terms of development of supportive care programs and services.

Our finding that patients with reduced income and those with negative change in work/school life after a cancer diagnosis were more likely to have psychological distress is also important. Kim and Yi (Reference Kim and Yi2013) also reported that significant levels of psychological distress were associated with unstable economic status. Previous studies showed that work-related issues resulted in distress (Stone et al., Reference Stone, Ganz and Pavlish2017) and employment/school status was significantly predictive of distress (Kwak et al., Reference Kwak, Zebrack and Meeske2013b). The ability to return or to maintain occupational and educational pursuits after a cancer diagnosis has been demonstrated to improve the QOL of patients with cancer, reducing social isolation, and increasing self-esteem (Peteet, Reference Peteet2000; Spelten et al., Reference Spelten, Sprangers and Verbeek2002). In a study by Bellizzi et al. (Reference Bellizzi, Smith and Schmidt2012), approximately 40% of young adults with cancer (ages 21–29, 39.9%; and ages 30–39 years, 38.2%) reported that their cancer had a negative impact on their plans for work. Work-related issues are one of the major topics in studies on cancer survivors. It is necessary for employers, companies, and schools to understand their situation and cooperate. As the Japanese government has been focusing on improving the circumstances of the working population and children (Araki and Takahashi, Reference Araki and Takahashi2017), it is expected to improve their occupational and educational status. Dealing with education and employment issues after a cancer diagnosis is essential in order to improve psychological distress and QOL.

AYA cancer patients might benefit from regular screening to detect those at risk for psychological distress (Michel and Vetsch, Reference Michel and Vetsch2015) and to provide adequate support or interventions if needed (Zebrack et al., Reference Zebrack, Mathews-Bradshaw and Siegel2010b; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, McDonnell and DeRosa2016). A survey of cancer centers across Japan in 2018 found that AYA support teams were active in 7 of 32 hospitals (Nakayama et al., Reference Nakayama, Toh and Fujishita2020). The AYA support team network has been established, and multidisciplinary support teams are gradually spreading across the country. Our findings potentially contribute to the intervention components for distress management among AYA cancer survivors. We are planning a clinical study to evaluate usefulness of a screening and intervention program by AYA support teams.

This study has some limitations. First, because we used a convenience sampling and analyzed the 206 respondents through a web-based survey company, we could not identify the characteristics of non-responders. However, this study enabled a national survey among young adults with cancer in spite of relatively low prevalence. Second, there is a gender imbalance in that more women than men participated. According to the data of the Cancer Registry of Japan in 2016 and 2017, there are more female than male cancer patients over 20 years old and 80% of patients in the 20–39-year-old group are female (National Cancer Center, 2019). Cancers of the breast, cervix, and thyroid are by far the most commonly diagnosed malignancies in younger adults, affecting exclusively or predominantly women (Vaccarella et al., Reference Vaccarella, Ginsburg and Bray2021). A gender imbalance in our study might occur because of the difference of incidence. Third, 40% of the participants had uterine cancer, which is the second most common cancer among patients in their 30s in Japan (Katanoda et al., Reference Katanoda, Shibata and Matsuda2017). According to the data of the Cancer Registry of Japan, the prevalence of uterine cancer in patients aged 20–29 is 9%, and that in patients aged 30–39 is 13% (National Cancer Center, 2019). As the study participants had more uterine cancer compared to prevalence, it is considered that there may be a selection bias. We should be careful about generalizing the results. Fourth, we did not examine their developmental issues. Although the majority of the participants were female, we did not investigate issues specific to women, issues with their partners, or fertility issues. Fifth, there were no participants under the age of 20, probably because their parents’ consent was needed in order to participate this survey if they were under 20 years old. Further research is needed to investigate psychological distress among adolescent cancer patients and survivors of childhood cancer. Finally, the cross-sectional design provides no information on causal relationships.

Our findings show that psychological distress among patients diagnosed within a year and long-term survivors (≥10 years since diagnosis) was relatively higher than patients 1–4 years since diagnosis. Coping at each phase presents new challenges: diagnosis phase, treatment phase, and post-treatment/remission/palliative phase (Miedema et al., Reference Miedema, Hamilton and Easley2007). It is important to understand their problems in each phase and their individual needs. Critical elements of effective psychosocial services should include access to AYA-specific information and support resources, fertility and sexuality counseling, programs to maximize academic and vocational functioning, and financial support (D'Agostino et al., Reference D'Agostino, Penny and Zebrack2011).

Acknowledgments

MF and YU designed the study. MO and MF analyzed the data. MO, MF, AS, MK, KO, SG, and TH interpreted it. MO and MF were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.