Ahead of the 2022 US midterm elections, an article appeared in The Economist titled “Why Are American Lawmakers So Old?” It presented statistical data showing the rapid aging of US Congress members: 200 years ago, three in four parliamentarians were under the age of 50, in 2022 three in four were over 50, and half of the members of Congress are now older than 60 (The Economist 2022b). In fact, the US Congress has aged much faster than the people they represent (Roberts and Wolak Reference Roberts and Wolak2022). Consequently, Congress has become “uniquely unrepresentative of the country,” as Business Insider points out (Fu, Hickey, and Gal Reference Fu, Hickey and Gal2022), and the public debate on age and politics is gaining momentum.

With many liberal democracies across the world going through fundamental demographic changes (Goerres and Vanhuysse Reference Goerres and Vanhuysse2021), questions of potential implications for the democratic system arise more frequently. Terms such as “gerontocracy,” “Rentnerdemokratie” (pensioners’ democracy, coined by Roman Herzog, former president of Germany), “Altenrepublik” (elderly republic), or “silver democracy” (McClean Reference McClean2020) have moved beyond the narrow borders of academic discourse and become buzzwords in the wider political debate on the future of liberal democracies. The dilemma seems to be the same everywhere: it is hypothesized that the shift toward a graying society has overrepresented the elderly’s interests and underrepresented the younger generation’s interests (Berry Reference Berry2014; Stockemer and Sundström Reference Stockemer and Sundström2022; Vanhuysse Reference Vanhuysse2013). Potential consequences include not only intergenerational conflict (Esping-Andersen and Sarasa Reference Esping-Andersen and Sarasa2002; Hess, Nauman, and Steinkopf Reference Hess, Nauman and Steinkopf2017; Kotlikoff and Burns Reference Kotlikoff and Burns2012) but also society’s diminished capacity to reform itself and retain its economic and cultural dynamism (Goodhart and Pradhan Reference Goodhart and Pradhan2020). Normative questions address the issues of intergenerational equity (Katō Reference Katō2011; Pickard Reference Pickard2019) and societal sustainability, in particular concerning the social welfare system, national debt, or the environment (Castles Reference Castles2005; Sternberg Reference Sternberg2019). Regarding politics, it is conjectured that an aging democracy creates a structural dilemma in which politicians cater more to the older part of the electorate, possibly leading to short-sighted policies (Sinn and Uebelmesser Reference Sinn and Uebelmesser2003; Terashima Reference Terashima2017).

The Effects of Population Aging on Democracy

For a liberal democracy, the consequences of population aging are twofold. First, on a policy level lawmakers must address the structural challenges that this dynamic poses to social welfare, healthcare, elderly care, infrastructure, public finances, and so on. Second—and this consequence has received less attention—population aging technically alters the way our democratic system works or does not work. Potentially, it changes the essence of democracy and therefore requires a rethinking of the premises on which our basic democratic principles are built. Most fundamentally, the theory of democracy often presumes that democratic ideals are best represented if the majority’s political will is fulfilled. However, what happens, as Berry (Reference Berry2014) suggests, when the will of a graying electorate results in a “tyranny of the majority” (Tocqueville Reference Tocqueville2000 [1835]) and no longer complies with the goal of building a sustainable future for the nation?

Some consider population aging to be a severe threat not only to economic prosperity but also to the functioning of democratic systems because it potentially poses fundamental challenges to political processes and thus political legitimacy (Arnesen and Peters Reference Arnesen and Peters2017; Buchanan Reference Buchanan2002). Berry (Reference Berry2014) argues that in a society with a pyramid-shaped age distribution it is taken as an “unwritten rule” of representative democracy that those voters who would be most likely affected by electoral outcomes the longest would be overrepresented. However, population aging has turned this idea upside down. It leads to what is generally referred to as “gray power,” suggesting that the elderly have a larger weight within the democratic process, particularly in elections, and are therefore more strongly represented in political decision-making processes (Stockemer and Sundström Reference Stockemer and Sundström2018; Takao Reference Takao2009; Topf Reference Topf, Vanhuysse and Goerres2013).

Berry is not alone in emphasizing the problematic effects of an aging democracy. Based on a quantitative calculation model, Sinn and Uebelmesser (Reference Sinn and Uebelmesser2003) predicted that, from the perspective of numerical voter majorities, reforms of the pension system would no longer be feasible. Referring to British society, Willetts (Reference Willetts2010) argues that by their sheer demographic power the baby boomer generation lives at the expense of future generations who will have to pay more taxes, work longer hours, and have lower social mobility. Kotlikoff (Reference Kotlikoff2011) goes as far as calling the high levels of public debt “fiscal child abuse” and criticizes a short-sighted financial system (in this case: the US one) based on consuming rather than on saving and investing (Kotlikoff and Burns Reference Kotlikoff and Burns2012).

There are studies, however, that emphasize the positive aspects of demographic change and question the political power of the “gray vote.” Davidson (Reference Davidson2014, Reference Davidson2016) disagrees with the pessimistic notion of population aging and maintains that the negative political and economic aspects of aging are regularly overemphasized in the debate. The discourse tends to be oversimplified by assuming an age-based majority rule and a monolithic elderly voting bloc while disregarding the fact that age is only one variable (next to others such as class, gender, ethnicity, etc.) that shapes political attitudes. Instead, it is necessary to consider intergenerational redistribution and intrafamily solidarity in the discourse (Arber and Attias-Donfut Reference Arber and Attias-Donfut2000; Brandt, Haberkern, and Szydlik Reference Brandt, Haberkern and Szydlik2009; Davidson Reference Davidson2014; Prinzen Reference Prinzen, Hank and Kreyenfeld2016). In his research on the political participation of elderly citizens in Europe, Goerres (Reference Goerres2009) disagrees with the view that in times of demographic aging the needs of elderly voters dominate policy making. He and other scholars argue that even if the elderly were to agree along generational lines on policy issues, one still has to look closely at how problems are framed, how electoral will is translated into policy, and which institutional frameworks shape policy outcomes (Esping-Andersen and Sarasa Reference Esping-Andersen and Sarasa2002, 6; Goerres and Vanhuysse Reference Goerres, Vanhuysse, Vanhuysse and Goerres2013; Tepe and Vanhuysse Reference Tepe and Vanhuysse2009, Reference Tepe and Vanhuysse2010).

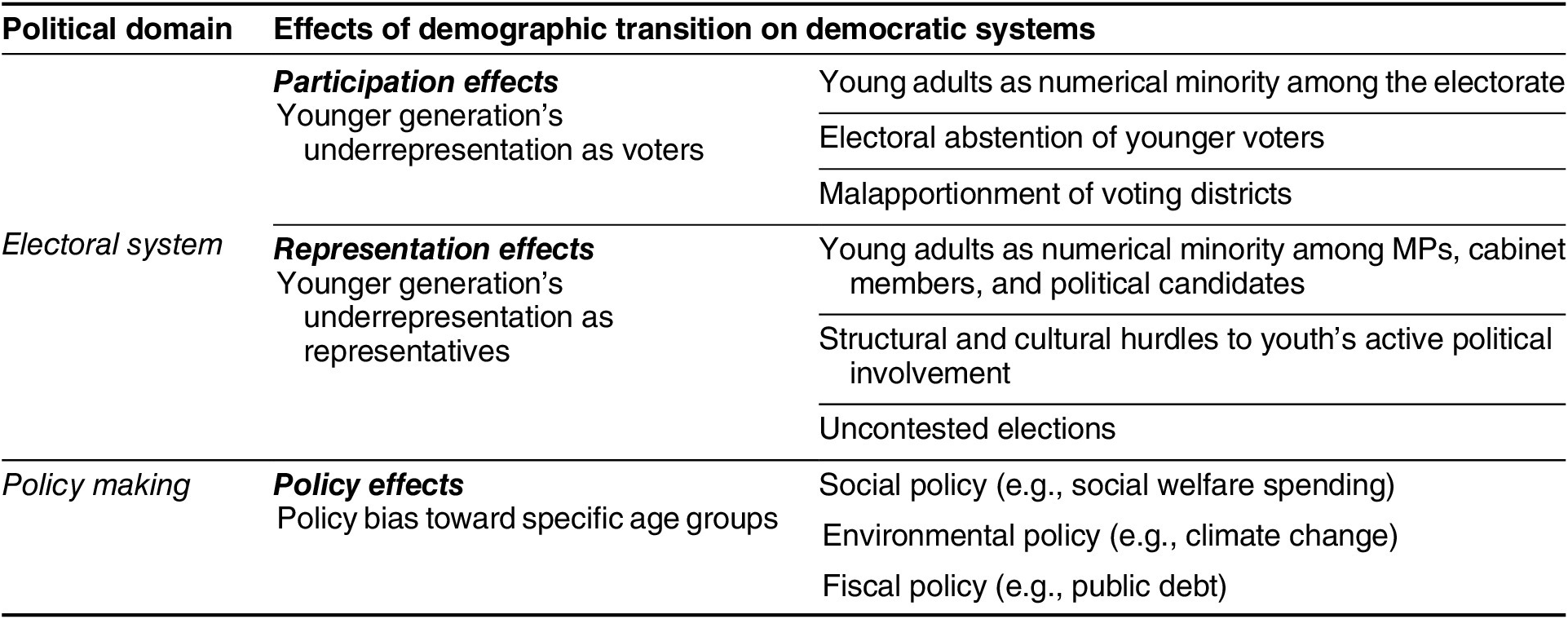

Although scholars are divided on how to interpret the different implications of demographic aging, they do agree on the challenges that a graying society poses to established political, social, and economic frameworks. Drawing on evidence from liberal democracies, with a focus on Japan, the democracy with the oldest electorate, we identify and analyze three types of potential demographic effects on the democratic system (table 1): participation effects deriving from the aging voters’ majority and the marginalization of young voters among the electorate, representation effects demonstrated by a dominance of elderly lawmakers and an underrepresentation of young people inside the parliament and government, and policy effects that manifest in an imbalance in policy making caused by a preference for policies catering to an aging majority.

Table 1 Effects of Demographic Transition on Democratic Systems

By examining the case of Japan and relating this to democratic theory, this article contributes to the discourse on how population aging alters political participation, representation, and policy making and how these effects challenge questions of democratic legitimacy as the political equilibrium between the generations shifts toward the elderly share of the constituents. Although our rationale is primarily based on evidence from Japan, where population aging is more advanced than in any other liberal democracy, we argue that thinking through the consequences of aging demographics on politics is relevant to most liberal democracies. In this regard, Japan provides a harbinger for what democracy may look like in years to come (Lipscy Reference Lipscy2022).

Japan’s Aging Democracy

With 29.1% of its population older than age 64 in 2021, Japan is the democracy with the oldest electorate in the world (Coulmas et al. Reference Coulmas, Conrad and Vogt2008; Statistics Bureau of Japan 2022), and the trend continues: its old-age population (65 years and older) is estimated to increase to about 38% by 2050 (NIPSSR 2017, 81), while during this century its population is estimated to shrink from 127 million (in 2019) to 75 million (in 2100; United Nations 2019, 17). Within the old-age population, the share of people over 75 is expected to double within a time span of less than 50 years (from 12.8% of the overall population in 2015 to 25.7% by 2060; NIPSSR 2017, 82). Not only will senior voters make up a growing share of voters within the electorate but also their voter turnout is higher than that of all other age groups (MIC 2022, 8).

Under the mounting pressures of demographic transition, the financial sustainability of the public pension and healthcare system has increasingly been characterized as critical (Campbell Reference Campbell, Coulmas, Conrad, Schad-Seifert and Vogt2008; Estévez-Abe Reference Estévez-Abe2008; Hieda Reference Hieda2012). However, previous policy attempts to reverse the trend of population aging have shown no substantive effects (Yamada Reference Yamada2020). Although the public and policy makers have been aware of the declining birthrate—one major indicator for Japan’s demographic transition—since the so-called 1.57-shockFootnote 1 of 1989/90, policies have not been able to substantially boost the total fertility rate (TFR; it stood at 1.33 in 2020, according to the Statistics Bureau of Japan [2022, 16]). The fact that Japan has so far rejected immigration as a means of supplementing the domestic population on a permanent basis (Liu-Farrer Reference Liu-Farrer2020; Vogt Reference Vogt2013, Reference Vogt2018) reinforces the downward dynamics of the country’s demographic trajectory.

Against this background we set out to ask what the transition to a “silver democracy” implies for the democratic system and its fundamental workings, specifically political participation, political representation, and policy making.

Participation Effects

A hyper-aging society results in increasing structural imbalances in the electoral system: it produces an overrepresentation of the elderly and correspondingly an underrepresentation of young adults both as voters and as political representatives. Young people in Japan account for an absolute numerical minority among the electorate. This means that 57% of voters (59.6 million) are 50 years or older, and 43% (44.4 million) are younger than age 50.Footnote 2 This imbalance is going to grow in the decades to come. By 2060, around two-thirds of all voters (67.5% or 54 million) are estimated to be 50 years or older, and only around one-third (32.5% or 26 million) will be younger than age 50 (Oguro Reference Oguro2017, 54).

This situation is exacerbated by the electoral abstention of younger voters. In most consolidated democratic systems, we see a similar tendency: the younger the voters, the lower the electoral turnout (Wattenberg Reference Wattenberg2020). In the case of Japan, the disparity in voter participation is particularly pronounced. For instance, the relative voter participation of young people in their twenties is less than half of that of people in their sixties.Footnote 3 Combining the old-age population’s absolute numerical weight with their higher participation in elections, nearly two of three votes stem from voters who are 50 years or older (64% of 50 years or older vs. 36% of under 50 years). If we apply the same ratio of voter turnout to the estimated age demographics in 2060, nearly four of five votes (79%) will be from voters older than 50 years.Footnote 4 And these voters under 50 do not even represent “youth” in a narrow sense.

Another issue aggravating the disequilibrium in voter participation is the malapportionment of voting districts. This issue is termed “inequality of the votes” (ippyō no kakusa) in the Japanese case; it derives from an electoral system that apportions disproportionately more parliamentary seats to rural regions than to urban areas (Reed Reference Reed, Pekkanen and Pekkanen2022). Thus, a vote in a rural area “is worth” two, three, or even up to six times more than a vote in an urban area. This situation has repeatedly been found unconstitutional by the Japanese Supreme Court (Sunahara Reference Sunahara2015). It ruled that five of eight elections on the national level (both Upper and Lower House) between 2009 and 2019 violated the constitutional demand for each vote to be represented equally in the Diet. Although this inequality is certainly related to an original design flaw in the electoral system, the situation is compounded by demographic change. It creates an unequal balance in favor of rural Japan, and because the rural areas experience a disproportionately faster aging of the population, it indirectly favors an elder electorate. This aspect is rarely mentioned in the debate on “unequal votes”: they are unequal both in a general democratic sense—they violate the “one person, one vote” principle—and from the perspective of intergenerational justice because young people gather more in urban areas where their votes are worth less.

To summarize, the younger population is underrepresented in the electorate in several ways: first, through their numerical minority due to their low and continuously declining share among the population; second, through youth absenteeism in elections, which is generally more salient the younger the voters are; and third, through malapportionment caused by the design of electoral districts resulting in a relative overrepresentation of sparsely populated rural regions with a high share of elderly voters. Without any reforms, an aging society necessarily leads to a structural marginalization of youth in the electorate.

Representation Effects

The absence of young parliamentarians, cabinet members, and political candidates is increasingly recognized as a serious democratic deficit worldwide (Stockemer and Sundström Reference Stockemer and Sundström2022). Japan constitutes a particularly striking case of youth marginalization in political representation: young people make up a numerical minority in parliament, government, and candidacies. The nation’s rapid aging of its electorate has been accompanied by an even faster aging of its political representatives. The average age of lawmakers at the time of elections has been steadily on the rise. At the most recent general election in 2021 it reached 55.5 years (Jiji Press 2021). In fact, lawmakers in their twenties play no role in Japanese politics on the local, regional, or national level. Although there have been 53 parliamentarians in their twenties in the national Diet from the end of World War II until today (Senkyo.com Editorial Team 2021), in the 2017 general election there were no successful candidates in that age group, and in the 2021 election there was only one. In 2021, only 4.7% of the successful candidates were in their thirties (Jiji Press 2021). This absence of young Diet members correlates with the decline in candidacies by young people. Although there was a slight upward trend until 2012, candidacies by people in their twenties and thirties have been significantly decreasing since; this corresponds with a notable rise in the average age of candidates from 50.4 to 54.2 years between 2012 and 2021 (Murohashi Reference Murohashi2022). In short, a rejuvenation of the Diet has not taken place: quite the contrary, the demographic aging of political representation continues. The gap in terms of age—and gender (Steel and Martin Reference Steel, Martin, Pekkanen and Pekkanen2022)—could hardly be bigger between those in the parliament and those represented by them.

Certainly, there are structural hurdles regarding the youth’s active involvement in Japanese politics: passive suffrage—the right to run for office—is only granted to those older than 25 years of age for the Lower House elections and to those older than 30 for the Upper House elections. In addition, the election deposit of 3 million yen (about USD 25,000) required by everyone standing for election is considered one of the highest, if not the highest, in the world. But there are other hurdles rooted in the political culture. Despite changes in the electoral system (Reed Reference Reed, Pekkanen and Pekkanen2022) and the media landscape, backing by (local) supporter groups and a candidate’s high profile continue to matter considerably. A recent study by the Nikkei Shimbun revealed that “hereditary politicians”Footnote 5 have an 80% chance of electoral victory compared to nonhereditary politicians, who may only have a 30% probability of winning. The Nikkei team analyzed election results from the 1996 general election onward, the first one after the major electoral reform in 1994. They concluded that the “3 Ban”—backing by local supporter groups, candidate publicity, and financial resources—are still vital factors for electoral success and a major hindrance to increased political competition (Nikkei Editorial Team 2021). Thus, it does not come as a surprise that second- or third-generation politicians play a significant role in Japanese politics. Hereditary politicians account for up to 30% of the members of the Lower House and up to 40% of the parliamentarians of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Of 32 postwar prime ministers, 28 were second- or third-generation politicians as of 2023 (Scartozzi Reference Scartozzi2017).

Another effect of population aging on the political system is the rise of uncontested elections due to a lack of candidates competing for office. The number of uncontested elections has reached a record high since the beginning of official records in 1951 (NHK 2019). In the 2019 Japanese regional elections, 39% of all electoral districts were decided by uncontested elections. For instance, in Gifu Prefecture, 48% of elected parliamentarians were elected automatically because they had no opposition; in Okuizumo town in Shimane Prefecture, the sole LDP candidate has been uncontested for more than three decades. Concerns are raised that the electoral will is no longer reflected under these circumstances, revealing a fundamental problem of democratic representation and legitimacy.Footnote 6

Policy Effects

Given the structural imbalances in political participation and representation, the questions arise how they are related to each other and whether they are reflected in policy making: Is there a policy bias toward a specific age group? In an initiative to measure the age orientation of the welfare state, Julia Lynch (Reference Lynch2006, 4) developed the elderly/non-elderly spending ratio (ENSR), which provides an approximation of “the relative weight of spending on the elderly […] versus that on working-age adults and children.” She found that the US and Japan welfare states lead the list of countries with the highest relative social spending for the elderly while neglecting the working-age population (social policy).

When comparing OECD data on social expenditures, we see that whereas more than 9% of the GDP is used for the elderly (old age and survivors) in Japan, only 1.6% is used for families and children: thus, the Japanese government spends about six times more for the elder than for the younger generation. This imbalance is even more pronounced in the United States where old people receive 11 times more government spending than young families. In contrast, OECD countries on average spend 3.6 times more government funds on the elderly. Government spending is more balanced across different generations in the Nordic and Anglo-Saxon countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.Footnote 7

In a large-scale analysis of local politics in Japan, McClean (Reference McClean2021) recently found a correlation between politicians’ age and their preferred welfare spending. Younger mayors increase long-term public investments in child welfare, whereas older mayors allocate funds toward short-term benefits for the elderly. This study reinforces the assumption that the political underrepresentation of young people leads to policy outcomes that affect them negatively (McClean Reference McClean2021).

As a result of “politics made by the old for the old,” issues disproportionately affecting the younger generations remain unaddressed. This may explain why environmental policy and climate change generally receive little salience in Japanese election campaigns, although these are issues that mobilize young voters elsewhere (see the Fridays for Future movement). Other, more tangible social issues often go unheeded in national debates. Experts regularly emphasize that child poverty has become a serious problem in Japan; one in seven children now live in relative poverty, a high rate among the developed nations. Child poverty is particularly prevalent in single-mother households: about every second such household lives below the line of relative poverty. From a policy point of view, it is striking that the tax and social welfare systems have no noticeable effect on alleviating child poverty. Although government redistribution programs do reduce poverty among the elderly, they have had little effect on poverty among working-age groups (Abe Reference Abe2018, 35–38).

The exceptionally high government deficit, an effect of Japan’s fiscal policy, also constitutes a burden for future generations. With its national debt exceeding more than 250% of its GDP, Japan has the highest debt level in the world (International Monetary Fund 2021, 123). Prior to the COVID pandemic, the trajectory of Japanese national debt was criticized as the result of a populist government policy catering primarily to senior voters and coming at the expense of younger generations (Katō Reference Katō and Funabashi2017; Katō and Kobayashi Reference Katō and Kobayashi2017; Yashiro Reference Yashiro2016).

In this context, intergenerational (in-)equality is receiving more attention. The theme of intergenerational justice and the normative notion of an obligation toward the younger generation have been part of modern political discourse since Rawls (Reference Rawls1971). In recent years initiatives have been put forward to systematically measure intergenerational justice to enable cross-national comparisons and develop policy reforms. A cross-national study of 29 OECD countries found that the United States and Japan ranked at the bottom in terms of intergenerational justice. One major factor contributing to this position was the overwhelming amount of public debt per child (Vanhuysse Reference Vanhuysse2013, 6).

The Dilemma of Legitimacy in the Aging Democracy

An aging democracy raises fundamental questions of democratic legitimacy. Based on conventional premises, a democracy is seen as legitimate if the electorate and parliament represent the population according to their demographic composition (age, sex, ethnicity, religion, etc.). This “one person, one vote” principle of proportional representation constitutes one of the fundamental pillars of modern democratic societies. In the United States, it is secured by the equal protection clause of the US Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment. From this perspective, it is fair that as the population is aging, older people should also disproportionately participate in and represent politics. However, from the perspective of pluralism (Baghramian and Ingram Reference Baghramian and Ingram2014; Dahl Reference Dahl2005 [1961])—another major democratic principle—proportional representation implies that young people’s voices become increasingly marginalized in the democratic process as societal graying advances. Hence, this ethical dilemma of an aging democracy challenges our notion of democratic legitimacy. What is legitimate in a democratic sense? The “one person, one vote” principle was established based on the assumption that the population structure showed a pyramid shape. Now that it has turned into an onion shape, the question arises whether proportional representation still does justice to the democratic claim of equal representation of the generations.

In this context, it is useful to distinguish descriptive from substantive representation. We believe that descriptive representation matters (Phillips Reference Phillips, Rohrschneider and Thomassen2020; Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). In the discourse on the political implications of an aging population, some argue that an aging electorate in fact does not pose a major issue because older people are not a homogeneous bloc, and differences exist both among older generations; in addition, values are shared between older and younger people. Moreover, participatory impact varies across time and depends on the social context (Goerres Reference Goerres2009, 170–75; Goerres and Tepe Reference Goerres and Tepe2010; Vanhuysse and Goerres Reference Vanhuysse and Goerres2013). Therefore, the elderly may not necessarily vote along generational lines and may be altruistic enough to consider their grandchildren’s perspective.

We certainly acknowledge the differences among the elderly in terms of income, ethnicity, gender, political attitudes, and other variables. Nonetheless, the notion of intragenerational heterogeneity does not constitute an argument against achieving a sounder equilibrium of political power across the generations. Following the logic of heterogeneity of a particular group (older voters in this case), and thereby implying there is no actual need for a representation that mirrors a broad societal spectrum (descriptive representation) amounts to arguing that there is only a limited need for women to be represented in parliaments because male politicians already account for a sufficiently heterogeneous group whose members in fact do not (always) follow their own self-interest but advocate for minority groups as well (substantive representation). Over the last decades the need for a certain level of descriptive representation has become a common understanding of liberal democracy; indeed, there has been a paradigm shift described as the transition from a “politics of ideas” to a “politics of presence” (Phillips Reference Phillips1995). To reform the democratic system it is necessary to change not only structures but also personnel because “who does the representation can be as important as the ideas or visions they represent” (Phillips Reference Phillips, Rohrschneider and Thomassen2020, 176). So far, descriptive representation has been discussed primarily in the context of gender and ethnicity; however, there is no (obvious) reason why age should be exempted.

After all, the question is neither whether a particular dominant group, be it older voters or a male-dominated parliament, is diverse itself nor whether this group is willing or capable of implementing “policies for all.” We believe this question is irrelevant from the theoretical viewpoint of intergenerational justice. It is simply the democratic claim that political participation and representation need to be inclusive (Young Reference Young2000), and thus a certain level of pluralism is required to successfully sustain legitimacy (Arnesen and Peters Reference Arnesen and Peters2017; Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). An aging democracy urges us to think and deliberate legitimacy beyond sheer numerical majorities and instead negotiate ways of effectively increasing generational pluralism in politics. Contemporary research both in the field of business and public administration, as well as diversity politics, unanimously demonstrates that pluralism matters, that it makes for better decision making, and that it results in improved political efficacy (Evans Reference Evans2016; Hunt, Layton, and Prince Reference Hunt, Layton and Prince2015; Smole and Sinclair-Chapman Reference Smole and Sinclair-Chapman2022; Williamson and Scicchitano Reference Williamson and Scicchitano2015).

Another argument that has a rather positive take on aging democracies notes the intrafamilial support and solidarity seen between the generations. Again, we do not seek to challenge this intergenerational support within families, which has been well researched, especially in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in the European context (SHARE; Börsch-Supan et al. Reference Börsch-Supan, Brandt, Litwin and Weber2013; Brandt, Haberkern, and Szydlik Reference Brandt, Haberkern and Szydlik2009). Yet we argue that intergenerational support structures and political representation need to be looked at separately. Help within families does not diminish the necessity for a healthier generational equilibrium in democratic governance. What should also not be forgotten is that, even though we observe remarkable levels of intrafamilial solidarity, these vary significantly within single societies and across different societies (Albertini, Tosi, and Kohli Reference Albertini, Tosi and Kohli2018; Isengard, König, and Szydlik Reference Isengard, König and Szydlik2018). Hence, one major question is how those young people who lack sufficient familial support fare, financially or emotionally. This is a relevant issue, giving rising inequalities worldwide (The Economist 2022a), the association between family status and the financial ability to provide intergenerational help, and the persistent correlation between family background and educational outcomes (Deindl and Brandt Reference Deindl, Brandt, Börsch-Supan, Kneip, Litwin, Myck and Weber2015). In addition, a lack of familial support may not always be due to a lack of financial resources but also may stem from intrafamilial conflict. This is particularly true for families belonging to minority groups within their respective mainstream societies (Guo, Lemke, and Dong Reference Guo, Lemke and Dong2021; Pittaway, Riggs, and Dantas Reference Pittaway, Riggs and Jaya2022).

Making adolescents rely on intrafamilial ties puts them into a precarious position of dependence and turns child-rearing and education into a family-dependent endeavor, the outcome of which is likely to eventually reflect existing social inequalities—unless there exists adequate extrafamilial, public support for the young (Furstenberg et al. Reference Furstenberg, Hartnett, Kohli and Zissimopoulos2015; Toguchi Swartz and Bengtson O’Brien Reference Toguchi Swartz, Brien and Furlong2016). However, social policy in advanced welfare states is oriented only slightly toward the needs of young families (Vanhuysse and Gal Reference Vanhuysse, Gal, Gilbert, Daly, Effinger and Besharov2022). In short, the argument that intergenerational support outweighs the shifting power equilibrium in democratic representation falls short because it tends to neglect social inequalities among families of different social status and presumes a particular, yet limited, type of well-off Western European or North American middle-class family with intact and supportive family structures. By emphasizing intergenerational solidarity instead of public redistributive mechanisms, the upbringing of young people relies on familial benevolence rather than legitimate claims guaranteed by legislative frameworks. Ultimately, intrafamilial support does not supplant an equal distribution of political power.

To be clear, we do not advocate a rule by the young; what we feel is needed is a healthier balance of political power distribution between the generations. This is why we make the case for an enhanced debate on potential correctives to the logic of sharing political representation between the generations in a democratic system that is increasingly becoming unbalanced in the face of dynamic population aging. As the demographic composition undergoes substantial change, democratic institutions and processes should be adjusted accordingly.

Where Do We Go from Here?

The inherent political dilemma of the aging democracy is now well recognized, and approaches to restoring an equilibrium between the generations have been put forward. Most focus on making changes to the logic of the electoral system by proposing alternatives that go beyond a mere majority vote. For instance, several scholars advocate a voting system in which future generations are represented via a proxy (Ekeli Reference Ekeli2009; Goodin Reference Goodin2007; Kavka and Warren Reference Kavka, Warren, Elliot and Gare1983; Sanderson and Scherbov Reference Sanderson and Scherbov2007). One contested proposition, the so-called Demeny-voting (named after demographer Paul Demeny), assigns additional votes to parents as proxies for their not-yet-enfranchised children. The basic idea is that, in doing so, voice is given to those who must live with the consequences of policy outcomes the longest, which by extension lowers the share of elderly voters (Oguro Reference Oguro2017, 75–79). Demeny-voting has been part of the discourse, particularly in Germany (Sanderson and Scherbov Reference Sanderson and Scherbov2007, 548–49; Vanhuysse Reference Vanhuysse2013). Slightly more daring is the idea to forfeit the voting process altogether and have members of parliament selected by lottery. This proposal was introduced by the Belgian historian David Van Reybrouck (Reference Van Reybrouck2016), who considers this a remedy for reviving democracy in times of rising populism, widespread distrust in the establishment, and political apathy.

Another approach proposes a voting system structured by age/cohort instead of geography: a “generational election system.” Originally suggested by the economists Toshihiro Ihori and Takero Doi, this proposal would allocate districts to certain age groups, ensuring that each generation is equally represented regardless of voter turnout or absolute numbers (Doi Reference Doi, Ihori and Terai2015; Oguro Reference Oguro2017, 74–75; Seo Reference Seo2017). Democratic education as a strategy to enhance voter turnout in the young generations has increasingly come to policy makers’ attention and holds great potential, as Nishiyama (Reference Nishiyama2021) shows.

The Aging Democracy: A Bleak Outlook?

One of the regrettable paradigms of dealing with the political implications of demographic change is that we are often left with quite a pessimistic outlook of the future, which at times leaves us overwhelmed and at a loss. However, here it helps to remember that, as Gietel-Basten (Reference Gietel-Basten2021, 437) points out, demographic change per se is not bad: in many cases it represents the “downstream outcome of various other processes or institutional malfunctions,” and the actual causes need to be sought in the broader socioeconomic context. Therefore, studying political demography provides the “bigger picture” beyond apparent demographic problems by comprehending the underlying social, political, and economic challenges, which eventually inform effective policy responses (Vanhuysse and Goerres Reference Vanhuysse, Goerres, Goerres and Vanhuysse2021). Political demography research can also highlight normative implications of population change, enabling us to collectively debate and develop visions of not only probable but also preferable futures.

The discourse on demographic aging tends to spark fierce reactions, picturing dystopic visions here and placating alarming voices there. There is a fine line to tread between painting not-too-dire scenarios while not trivializing the repercussions of age demographics on politics. As Kersten and colleagues (Reference Kersten, Neu and Vogel2012, 129) emphasize, it is crucial that democratic leadership does not shy away but confronts the debate on the conflict potential of an aging society; at the same time, leaders must convey to the public their commitment to just redistributive politics and to alleviating intergenerational inequities and social disparities.

This is why exploring in-depth case studies—with their presentations of varying age gradients and democratic practices in different polities—can be illuminating. The Japanese case suggests that a significant structural imbalance in political participation and representation between the generations has taken root and that this imbalance is increasingly reflected in policy outcomes. After all, it is not only about senior voters’ choice at the ballot box or political party manifestos during elections; ultimately it is about whether, in the fierce competition over fiscal resources, governments are willing to make concrete policy decisions in favor of all generations. The disequilibrium in political power between the generations is not easily changed by electoral will but is structurally and thus deeply entrenched in the entanglement of demographic aging and democratic processes described earlier. With the passage of time, this democratic aging process is likely to increase and perpetuate itself with little perspective for change.

Yet, there do exist positive tales showing us that the outlook on population aging and politics does not necessarily have to be bleak: rejuvenation, or diversification in a broader sense, is possible as the German case of the 2021 Bundestag federal elections demonstrates. Long dominated by old white men, the German parliament has now become the youngest and most diverse in its history. Around 30% of parliamentarians are 40 years or younger, doubling the number in this age group from the previous election in 2017. For the first time two openly transwomen, an openly bisexual woman, and more lawmakers with a “migration background” were elected (Nöstlinger Reference Nöstlinger2021). It is still too early to tell whether the diversification of political representation in Germany can be upheld in the long term and how it plays out in concrete policy measures, but it seems to provide an instructive case for further inquiry into the interplay between societal aging and politics.

Toward Generational Pluralism

We should keep in mind that, although democratic principles of political representation were taken for granted in their respective age, they were always highly contingent on the sociohistorical context. Let us take the principle of equal representation, for instance. Even though “equal representation” was claimed at the beginning of modern democracy worldwide, not even half the population was represented because the principle was literally saying “one (white) man, one vote”: women and ethnic minorities were excluded from voting. As far as women’s suffrage in the United States is concerned, it took more than a century from the very first federal elections in 1788–89 until women were effectively enfranchised for national elections in 1920. For nineteenth-century society, women’s suffrage was unthinkable, even among female citizens themselves, and advocating women’s voting rights was considered something radical. This is how deeply ingrained were the normative values and beliefs of that time (DuBois Reference DuBois2020).

The historical trajectory of democratic norms and principles is clearly dependent on the sociopolitical context. Democratic institutions and processes are always changing and so do the values underlying these institutions and processes. Democratic principles are contingent, are open to reinterpretation, and often must adapt to sociopolitical circumstances for the system to retain its legitimacy. Ideas that appear disconcerting to us today may seem normal tomorrow. Proxy votes for children or a generational election system could be such a normality one day.

While reflecting on the aging of our politics, we should be aware of our own sociohistorical positioning. Eventually, we must acknowledge that the twenty-first-century dynamics of demographic aging are unprecedented in history. There has never been an era in history in which old people outnumbered young ones. The onion-shaped population pyramid has only become possible because of modern medical progress and changes in social values and norms. In this sense the expansion of life expectancy needs to be seen as a success story of modernization, but at the same time it is accompanied by the reflexive undercutting of the founding principles of the modern nation-state (Beck, Giddens, and Lash Reference Beck, Giddens and Lash1994): it is beginning to call into question the institutions and processes that enabled this very success story. While national subsystems such as welfare or healthcare are struggling to adapt, the democratic system itself, which has to govern them, largely remains unchanged. But how should a political system find appropriate answers to demographic challenges if it has not even adequately addressed the demographic challenges the system is facing itself? Therefore, going forward we should reconsider our understanding of democratic procedures and values and start negotiating actual rearrangements of our democratic framework.

To devise a system in which all generations are more equally represented, we must come up with new parameters reflecting the call for generational pluralism and societal sustainability. We may have to go beyond conventional premises of proportional representation. The question of how democratic governance can concretely adapt to the profound tidal turn in age demographics exceeds the scope of our reflections. But what we do know is that these questions require more public and academic scrutiny, and it is imperative to set about reimagining the political equilibrium between the generations.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Karen Shire, David Chiavacci, Klaus Vollmer, and Celeste Arrington for their insightful comments on previous versions of this article. We also thank Michael Bernhard and the anonymous reviewers for their highly engaging and constructive feedback.