Mainstream political science literature on clientelism tends to focus on specific types of exchanges (instrumentalist types, such as vote-buying), and specific types of actors (parties, patrons, and brokers). Less research has been dedicated to clients and their diverse experiences when interacting with clientelism. Prospective clients have generally been conceptualized as rather passive and, if poor enough, willing vote sellers. Possibly as a result of this focus, this mainstream literature generally holds a negative view of clientelism (Stokes Reference Stokes, Boix and Stokes2007; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013).

In contrast, political ethnography records a rich set of experiences, motivations, and views by poor people in clientelistic settings. Whereas some work echoes an instrumentalist view of the exchange, where clients have cynical attitudes towards clientelism and politics in general (e.g., Lazar Reference Lazar2004) other work shows the social embeddedness of some forms of clientelism where clients conceptualize the relationship in friendship-style terms (e.g., Auyero Reference Auyero2000). Ethnographic work also emphasizes the agency of clients and shows that clients often deliberately approach patrons or brokers rather than being targeted by them (e.g., Auyero Reference Auyero1999; or Hilgers Reference Hilgers2009). Possibly because of this more diverse picture and higher client agency, ethnographers portray clientelism in a more positive light, at least in certain contexts (e.g., Shefner Reference Shefner and Hilgers2012).

In recent years, mainstream political science has started to pay more attention to the role of citizens for clientelism. This emerging literature sees citizens as more active participants in the exchange than in previous literature (Auerbach and Thachil Reference Auerbach and Thachil2018; Gonzalez Ocantos, Kiewiet de Jonge, and Nickerson Reference Ocantos, Ezequiel and Nickerson2014; Kao, Lust, and Rakner Reference Kao, Lust and Rakner2017; Mares and Young Reference Mares and Young2019; Nichter Reference Nichter2018; Nichter and Peress Reference Nichter and Peress2017; Pellicer et al. Reference Pellicer, Wegner, Benstead and Lust2017; Zarazaga Reference Zarazaga2014). In a recent review article, Hicken and Nathan (Reference Hicken and Nathan2020) argue that understanding client behavior is a core future research direction of work on clientelism.

While interest in the client side is increasing, we still lack a systematic perspective on that side of clientelism. Fundamental questions remain unanswered. What are the main types of clientelism that clients experience? What are their welfare implications for clients? What are the trade-offs clients face when engaging in these forms of clientelism?

Answering these questions requires a typology of clientelism that emerges from the perspective of clients—a typology that can be used to theorize about what different types of clientelism mean for clients. Although the literature has proposed numerous typologies or classification schemes (e.g., Kitschelt and Wilkinson Reference Kitschelt, Wilkinson, Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Mares and Young Reference Mares and Young2019; Nichter Reference Nichter2008, Reference Nichter2014; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013), there is no consistent, universally agreed upon, typology. Moreover, these typologies are usually informed by the patron side of clientelism and are mostly used to investigate patron trade-offs.

We seek to contribute to a systematic study of the citizen side of clientelism by conducting a meta-analysis of ethnographic literature on clientelism featuring the client’s perspective. Our meta-analysis is based on forty ethnographic (or area study) articles featuring the client’s point of view on clientelism in different world regions. We apply a coding scheme to record the characteristics of clientelistic exchanges described in the articles. We code characteristics such as the type of goods exchanged, the frequency and hierarchy of interactions between patrons and clients, and the extent of client agency, among others.

We perform two types of systematization analyses on our data: cluster analysis and principal component analysis (PCA). The cluster analysis groups clientelistic exchanges into subtypes, delivering a typology of clientelism. The PCA combines the characteristics of exchanges into two core dimensions that distinguish between different types of clientelism in a parsimonious way.

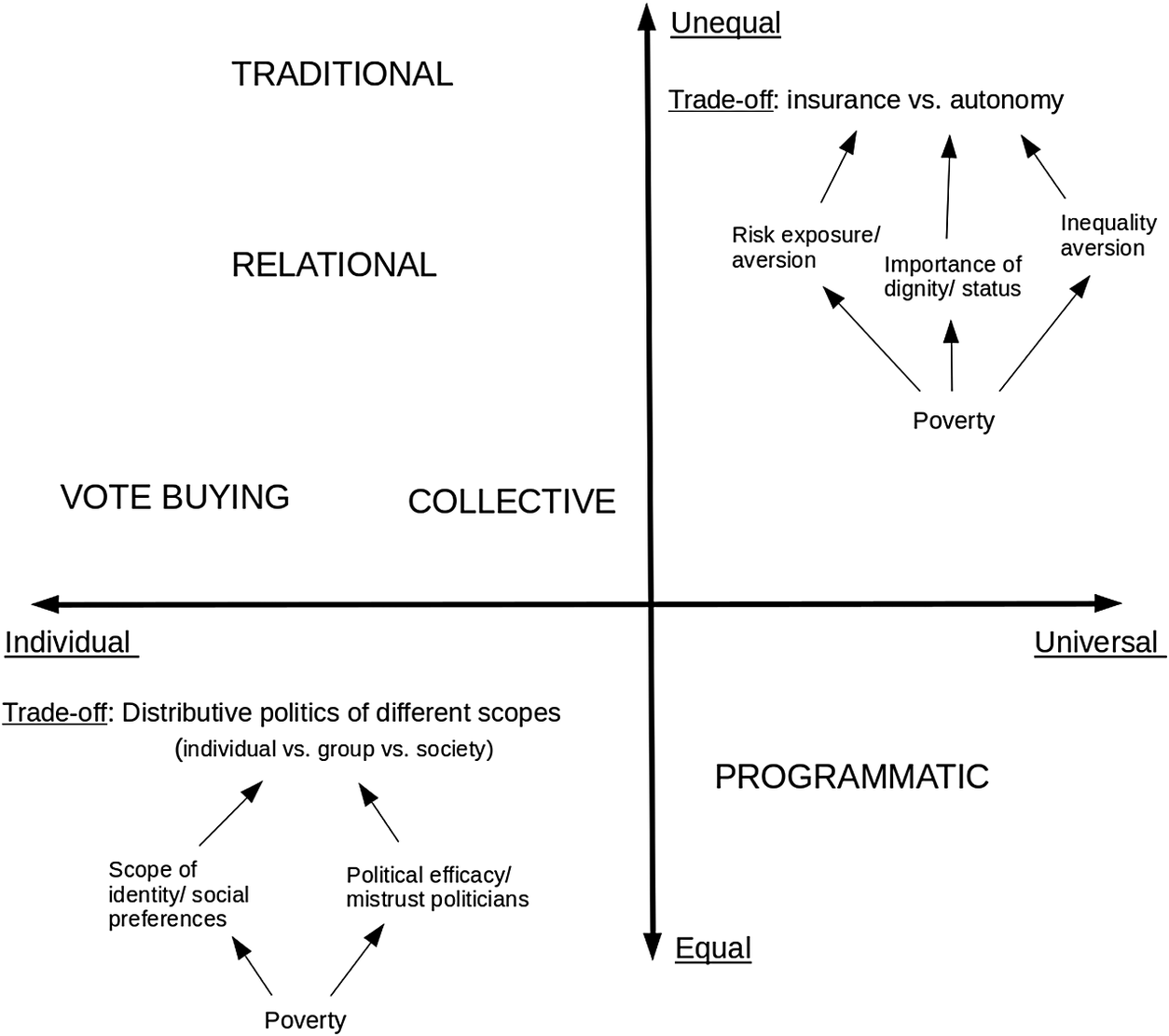

These two analyses provide answers to the first question, on what distinguishes different types of clientelism from the client’s perspective. The cluster analysis uncovers three main types of clientelism, which we label vote-buying, relational, and collective clientelism. We also find two smaller clusters that correspond to traditional and to modern coercive clientelism. The cluster analysis describes the types in quite some detail, distinguishing these types in terms of the goods clients and patrons exchange, the level of the exchange, the characteristics of the relationship, and the role of brokers. In turn, the PCA uncovers two basic dimensions that can distinguish between most of the types. We label these two dimensions the “Equal-Unequal” and “Individual-Universal” dimensions of clientelism. The equal-unequal dimension taps into how hierarchical and thick the clientelistic relationship is. Traditional and relational clientelism are characterized by high inequality and thickness. The individual-universal dimension taps into how large the group of the beneficiaries is. Collective clientelism denotes exchanges involving a group of beneficiaries as opposed to individual ones. Vote-buying, in turn, displays comparatively little universality and little inequality.

We use these types and dimensions of clientelism to engage with the second set of questions, regarding the welfare implications and trade-offs associated with subtypes of clientelism from the client’s point of view. Our data suggest that each dimension of clientelism matters for client welfare in a different way. The equal-unequal dimension is related to client agency in the sense that more unequal types of clientelism are associated with less client agency. The individual-universal dimension is related to how good a deal the client gets: clients get a better deal in more universal types of clientelism. We then use these two dimensions to theorize in an empirically grounded way about the trade-offs that clients face when engaging in different types of clientelism. We propose that the equal-unequal dimension represents a trade-off between protection/insurance, and autonomy; the individual-universal dimension represents a trade-off about the value of supporting distributive politics of different scopes.

Our meta-analysis reaffirms and reconciles major types of clientelism that have been derived mostly deductively in the existing literature. Our analysis shows that the types of exchanges that are observed at the micro level in ethnographic work in different world regions aggregate into familiar categories emphasized in current typologies, such as vote-buying, relational clientelism, or collective clientelism. Moreover, by providing a thick but systematic description of these types, our analysis clarifies and unifies types of clientelism conceptualized by different researchers under different labels and with an emphasis on different aspects of the exchange.

Our typology is particularly relevant for the client perspective on clientelism. Whereas most typologies in the literature are informed by research mostly on the patron side and emphasize aspects that are relevant for the patron (e.g., whether the resources are private or public or the payoffs of targeting specific types of voters), ours emerges from empirical work on the client’s perspective. This implies that the types of clientelism we uncover are relevant for the client, as shown by our results on client welfare.

More generally, our analysis provides the basis for a structured study of the “demand side”Footnote 1 of clientelism. The standard model of clientelism focuses on a single trade-off for citizens between the expressive benefits of programmatic politics and material benefits from clientelism (Dixit and Londregan Reference Dixit and Londregan1996; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013). In contrast, our study highlights two dimensions of clientelism that involve different trade-offs for the client. The trade-offs point towards previously unexplored factors that can matter for the demand side of clientelism, such as autonomy, social preferences, or group identity.

Conceptualizations of Clientelism

Defining and Delimiting Clientelism

Based on research on “traditional societies” in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, clientelism originally denoted a relatively narrow phenomenon. It was defined as “a long term relationship between two people of unequal status who have relatively regular personal interactions” and exchange “goods and services” (Hilgers Reference Hilgers2011, 570). The patron provided goods and services such as material resources, advice, or protection/insurance, and the client provided services that enhanced the status of the patron, such as political support or labor. This definition separates clientelism from a host of other forms of particularistic exchanges such as vote-buying or club goods.

In more recent definitions of clientelism, the unequal status and strong personal relationships are no longer mentioned, and the concept of clientelism has come to refer purely to an instrumental exchange between a politician or broker and a citizen. This is apparent in Kitschelt and Wilkinson’s definition, according to which clientelism is a “transaction, the direct exchange of a citizen’s vote in return for direct payments or continuing access to employment, goods, and services” (Reference Kitschelt, Wilkinson, Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007, 2; emphasis added), or Stokes’s definition as “the proffering of material goods in return for electoral support, where the criterion of the distribution that the patron uses is simply: did you (will you) support me?” (Reference Stokes, Boix and Stokes2007, 605). These definitions capture a much wider set of empirical phenomena than the older clientelism literature envisaged. In the current literature, the key criterion to establish that a political linkage is clientelistic is whether it involves conditionality: the citizen votes for the politician because the politician gives benefits and the politician gives benefits because the citizen votes for him or her (Nichter Reference Nichter2014; Stokes Reference Stokes, Boix and Stokes2007; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013).

Another strand of research, mostly in economics, has an even broader conception of clientelism. In his widely cited work, Wantchekon (Reference Wantchekon2003) considers clientelism anything that is not a public good or serves all citizens, such as national unity or peace. Thus, clientelistic goods include local public goods, such as schools, in addition to offers of individual patronage.

The most common conceptualization of clientelism at present is as a contingent, or conditional, exchange. However, there is a certain ambiguity regarding how literally conditionality should be taken. If it is taken literally, it requires that the reason the patron gives resources to a given citizen is because she receives political support in exchange, and the reason a citizen provides political support is because she receives benefits in exchange. These conditions are hard to fulfill, let alone to identify for an external observer. Possibly the only type that fulfills this criterion is vote-buying with monitoring: the citizen receives goods just before or at the moment of the election, and the patron is able to monitor that the citizen reciprocates.

A broader view of clientelism that moves beyond vote-buying requires to make the criterion less stringent. Indeed, in a recent review article on clientelism, Hicken and Nathan (Reference Hicken and Nathan2020) argue that it is time for research to abandon the focus on commitment problems and to relax the contingency criterion. In line with this, we interpret the criterion of conditionality more loosely, considering that there is conditionality when the main rationale for the actions of the two actors is an expectation of reciprocity but that this reciprocity is not necessarily monitored or enforced.

This looser conception of conditionality allows us to consider a broader set of clientelistic relations, including those considered by older work and economists. In the long-term relations described by the scholars of clientelism in the 1960s and 1970s, it is difficult to be sure that the only reason why a traditional patron provides favors or goods to the citizen is because she provides political support, and vice versa. There may be social norms, economic reasons, or even genuine affection contributing to the patron’s and client’s actions. Similarly, an exchange involving local public goods as patron goods would not be considered to be clientelism under a literal definition of conditionality, because local public goods are not excludable. Under our looser conception of conditionality, we will include both forms of exchange as clientelistic if it appears that an exchange logic is a driver of the behavior of patrons and clients.

To summarize, we restrict our attention to interactions where the main rationale for the interaction is conditional (i.e., an exchange) and where citizens provide some form of political support (possibly in addition to other things such as labor). This embeds our definition in the current literature, but makes it flexible enough to consider a great variety of possible clientelistic exchanges/relations.

Typologies and Subtypes of Clientelism

Recent literature on clientelism has proposed numerous typologies or classifications attempting to distinguish between contemporary subtypes of clientelism, as well as between clientelism and other forms of non-programmatic or programmatic politics.Footnote 2 In a non-exhaustive search, we identified fourteen such endeavors in the past twenty years (refer to the overview in table A.1 in the online appendix).

Many typologies start with the distinction between programmatic and non-programmatic politics. Further, many scholars make distinctions between collective and individual exchangesFootnote 3 and between exchanges that are concentrated at election time or go beyond campaign periods. There is some broad agreement about these core distinctions even if the labels used are often different or the same label is applied to somewhat different phenomena. Beyond this, scholars have introduced further distinctions between different forms of electoral clientelism (Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter Reference Gans-Morse, Mazzuca and Nichter2014; Nichter Reference Nichter2008, Reference Nichter2014) or between coercive and non-coercive forms of clientelism (Mares and Young Reference Mares and Young2019).

These recent typologies show a growing awareness that there is a need to understand the mechanics and implications of different subtypes of clientelism. However, at present there is no universally accepted typology. The existing typologies are not well integrated as they are often developed in relation to a particular geographic region, particular forms of political organizations (e.g., machine politics in Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter Reference Gans-Morse, Mazzuca and Nichter2014; Nichter Reference Nichter2008; and Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013), empirical projects (Hutchcroft Reference Hutchcroft, Brun and Diamond2014; Mares and Young Reference Mares and Young2019; Nichter Reference Nichter2008, Reference Nichter2018; Yıldırım and Kitschelt Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020), or edited volumes (Berenschot and Aspinall Reference Berenschot and Aspinall2020; Kitschelt and Wilkinson Reference Kitschelt, Wilkinson, Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Piattoni Reference Piattoni2001).

These current typologies have arisen in the context of mostly patron-oriented work on clientelism in the past twenty years. While types of clientelism are, per se, not tied to a patron or client perspective, in practice, the current typologies are typically informed by research on the patron side and have been used to theorize about factors that are especially relevant from the patron perspective.Footnote 4 Thus, there is a strong emphasis on contingency, client defection, and the monitoring of client votes (e.g., in the typologies of Kitschelt and Wilkinson Reference Kitschelt, Wilkinson, Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Nichter Reference Nichter2008, Reference Nichter2014; or Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013). Much effort has also been invested into understanding the trade-offs for patrons when engaging in different forms of electoral clientelism such as abstention, turnout or vote-buying (Nichter Reference Nichter2008; Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter Reference Gans-Morse, Mazzuca and Nichter2014). Several typologies also consider the origin of patron resources as an important discriminating factor (Berenschot and Aspinall Reference Berenschot and Aspinall2020; Hutchcroft Reference Hutchcroft, Brun and Diamond2014; Mares and Young Reference Mares and Young2019; Yıldırım and Kitschelt Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020). Contingency/monitoring, patron trade-offs, and resources as well as differentiations between abstention, turnout, and vote-buying are sensible foci if the research focus is on the patron. However, they are likely to be less relevant for the citizens’ view and actions regarding clientelism.

With the inductive typology we develop in this paper, we aim to bring existing typologies together and reconcile them with the insights gained from decades of political ethnography on clientelism. Most importantly, by relying on ethnographic work on the client’s point of view, we aim to build a typology that is relevant for the client perspective on clientelism and can be used to derive implications for client welfare and the trade-offs.

Coding Ethnographic Literature on Clientelism

Selection Procedure

Our objective is a meta-analysis of ethnographic work that focuses on the clients’ perspectives. Our sample is not intended to be representative of all ethnographic work on the citizen perspective on clientelism. Rather than aiming for representativity of scholarship, which is particularly concentrated in certain countries and regions, we sought a more balanced representation of different countries and world regions.

To select work for the meta-analysis, we adopted the following procedure.Footnote 5 First, we identified potential papers for coding. We started with a literature search with “clientelism” (or patronage, informal political exchange, caciquismo, neopatrimonialism), and our perspective (“client point of view,” “demand side,” or “micro”) as keywords. An important challenge in identifying relevant scholarship was that authors of relevant work do not necessarily conceive of their research as work on clientelism and hence do not use this term anywhere in the text let alone as a keyword. Much relevant work is conceptualized as studies of elections and democratic representation or of socio-political relations. To address this problem, we sought additional article recommendations from authors of ethnographic papers on clientelism, and screened journals where relevant studies had been published as well as the references of those studies. This resulted in a body of literature of approximately 300 articles, books, and book chapters.

Second, we screened each paper to check its suitability for our analysis using three criteria. First, the papers had to fall under our definition of clientelism. Thus, we excluded literature which uses the term clientelism, but addresses non-contingent politics, corruption (clients providing no political support), or closed political regimes. Second, in line with our focus on the client perspective, we looked for exchanges that involved common citizens. Thus, we excluded literature on political intra-elite exchanges (e.g., elite clientelistic networks, linking a country’s rulers to economic elites). Third, we excluded papers that did not provide any detail on how clients viewed the exchange. This third criterion was relaxed in order to obtain representation from different world regions. This procedure reduced the amount of suitable papers dramatically to only 40 papers or chapters.

Our meta-analysis is based on these forty pieces of ethnographic scholarship. The geographical focus of these papers is fairly balanced between Latin America, Asia, and Africa (refer to table D.1. in the online appendix). It leans strongly towards contemporary clientelism with 83% of the papers published after 1990.

The unit of analysis of our study is a clientelistic exchange (not a paper or a country or area case). Papers sometimes describe more than one type of clientelistic exchange. When this is the case, we consider these exchanges as separate observations. Overall, our meta-analysis comprises sixty separate clientelistic exchanges.

Coding Scheme: Characteristics of Clientelistic Exchanges

We designed a questionnaire asking about characteristics of clientelistic exchanges in the papers.Footnote 6 The choice of which characteristics to code is crucial for our study. Once these characteristics are chosen, the analysis is mainly data driven. We make this choice following the literature as much as possible.

We start with some obvious characteristics of clientelistic exchanges, such as the type of goods being exchanged: what type of political support does the client provide? A vote or labor? What does the patron provide? Money or small gifts, employment, local infrastructure?

Other characteristics were less obvious; for these we relied on the literature, and particularly on Hicken (Reference Hicken2011). Hicken discusses four main dimensions of clientelism: contingency, dyadic relationships, hierarchy, and iteration. As mentioned earlier, we take contingency (or conditionality) as a definitional characteristic of clientelism and focus on the others.

The notion of dyadic is prominent in early scholarship about clientelism. We follow the seminal work of Landé (Reference Landé, Schmidt, Guasti, Landé and Scott1977) to define a dyadic relationship as a “direct relationship” that “connotes a personal attachment”: a relationship between client and broker/patron is dyadic if it is based on a personal attachment rather than on the office people hold. Different clientelistic relations may be more or less dyadic.Footnote 7 We also consider another characteristic related to but distinct from dyadic: how affective (versus pragmatic) the relation is. A personal (clientelistic) relation may incorporate affective links such as respect and mutual care or may be totally pragmatic and instrumental.

Another feature emphasized by Hicken (Reference Hicken2011) is hierarchy. Hierarchy denotes the difference in power between the patron and client. It builds on the idea that the relations between clients and patrons are generally perceived to be asymmetric to the patron’s advantage. We expand on this idea to consider other relevant features related to this. We consider if the broker is important in the community and if the interests of the broker and clients are aligned.

The last feature emphasized by Hicken is iteration. Iteration refers to the recurrent nature of a relationship. Clientelistic relations may be iterative (ongoing), or not (one-off). We therefore assess the frequency of interactions between client and patron/broker. Additionally, we consider a measure of intensity of the relation: the domains of interaction of the client and her patron/broker—in particular whether the client and her patron/broker interact over and above the political realm that constitutes the clientelistic exchange. For instance, is the client an employee of the patron? Is the patron a particularly important social figure in the community, such as a chief?

In addition to these characteristics, we consider two other characteristics emphasized in recent literature. The first is coercion, as in Mares and Young (Reference Mares and Young2019). We distinguish between two types of coercion to pressure clients: threats of violence, and threats of withdrawal of government benefits. The second characteristic is the level of the exchange, namely whether the exchange happens at the individual level (with individual rewards) or at the collective level (with local club goods).

In addition to these core characteristics, we are interested in the welfare implications of the exchange from the client point of view. For this, we record the coder’s subjective evaluation of the clientelistic relation, such as how much “agency” the client seems to have or how good a deal she gets. Finally, we code some basic features of the environment, such as the decade where the fieldwork took place, whether the setting was urban or rural, and what alternatives there seem to be to the clientelistic exchange. Welfare and environmental variables will not be included in the cluster analysis or the PCA. The welfare variables will be used to investigate the implications of types of clientelism with client welfare.

The coding process generates a dataset where the observations are specific clientelistic exchanges and the variables are characteristics of these exchanges.Footnote 8

Coding Challenges

There are several challenges in the implementation of our coding scheme. First, there is ambiguity in how many clientelistic exchanges to code in one paper. Papers may describe different types of exchanges with varying detail, and it is not straightforward to decide which of these types warrant a separate coding. For instance, a paper may describe a broker engaging in different types of exchanges but may not specify if each exchange occurs with separate clients or with the same client. Are these exchanges coded as one observation or two? In our data, of all the exchanges we identified (sixty), in almost 70% of the cases (forty-one) the same exchange was identified by the two coders independently. This suggests that the problem of identifying specific clientelistic exchanges, while real, is not that acute. The exchanges that are coded twice are aggregated by taking the average of the values of the two coders. The rest of the exchanges are kept as separate observations.

Second, there is ambiguity in coding specific variables. Some of the concepts we seek to measure are subjective (e.g., how good a deal the client gets). Even for concepts that are more objective, the papers are not always detailed enough in their description of the clientelistic relation. Table A.2 in the online appendix provides several common measures (Cohen’s Kappa, Krippendorff’s alpha), to study intercoder reliability for each variable, using the forty-one double-coded exchanges. All measures deliver similar results.Footnote 9 In general, variables report moderate to high levels of agreement, according to commonly used rules of thumb (Landis and Koch Reference Landis and Koch1977). Unsurprisingly, the worse-performing variables tend to be the most subjective ones, particularly the subjective evaluations of the exchanges (for example, whether clients get a good deal). While we will still use them to explore the welfare implications of different types of clientelism, these results need to be treated with care.Footnote 10

Types and Dimensions of Clientelism

Types of Clientelism

Our first objective is to derive a typology of clientelism from the data. This involves consolidating the sixty different exchanges into distinct subtypes. This can be achieved by cluster analysis. Cluster analysis takes observations with given characteristics and breaks the observations into groups that are similar among themselves, but different from other groups. There are different approaches to cluster analysis. We choose hierarchical clustering because this approach does not require the user to pre-specify the expected number of clusters in the data, as some other techniques do. This makes it best suited for an inductive, exploratory analysis like ours. As online appendix F explains, it is sensible to choose five clusters. Three of them are fairly large (with fourteen to eighteen exchanges each) and two of them are small (with three exchanges each). We proceed with discussing all clusters but place special emphasis on the three larger ones.

The cluster analysis simply groups similar observations into clusters. The key question is whether these clusters represent recognizable types of clientelism. To investigate this, we compute the average characteristics of each cluster. Table 1 lists the most prominent characteristics of each cluster. Columns 1–3 correspond to the three largest clusters, columns 4–5 to the two small clusters. Characteristics that start with the word “No” are characterized by the explicit absence of the characteristic in a cluster, if a characteristic is not mentioned, it means that values of that characteristic are similar to those in other clusters.Footnote 11 Naturally, cluster analysis does not “tell” us a label for a cluster, but to connect it to the existing typologies in the literature, we will label each of them with a commonly used name to the extent that this is possible.Footnote 12

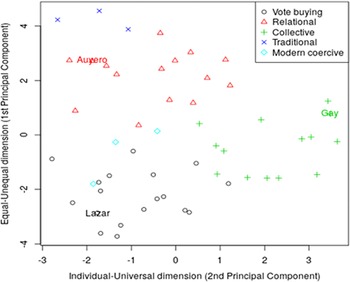

Table 1 Characteristics of clusters

Note: Most prominent characteristics of clusters; characteristics for which the cluster average of the corresponding standardized variable is higher than 0.33 in absolute value. Characteristics in bold have an average above 0.8 in absolute value. Characteristics that start with the word “No” are characterized by the explicit absence of the characteristic in a cluster, if a characteristic is not mentioned, it means that the values of that characteristic are similar to those in other clusters.

The first cluster is characterized by an individual, explicitly infrequent, interaction that is restricted to the political exchange; that lacks dyadic, affective, or hierarchical components; and is with a broker who is less important in the community and whose interests are unrelated to those of the client. The client simply gets money and gives the vote. She certainly does not give loyalty and does not obtain insurance, protection, or infrastructure. With these features, the cluster corresponds quite clearly to a one-shot, thin, instrumental type of clientelistic interaction. Following the literature, we thus denote it the vote-buying cluster.

The second cluster features an individual relation that is frequent, affective, hierarchical, and dyadic, where client and broker often interact beyond the strictly political realm. The client gets insurance and employment and gives the vote in exchange. The broker or patron is an important member of the community, but broker interests are neither aligned nor un-aligned with those of the client. Following Nichter (Reference Nichter2018), we label this cluster relational clientelism.Footnote 13

The third cluster displays a type of clientelism that takes place at the group level (“No individual”). Clients get mainly infrastructure, as opposed to anything else, and give in exchange the vote. The interests of the broker are aligned to those of the clients. The relation is not particularly hierarchical or frequent. This cluster corresponds to a collective type of clientelism, where the broker appears to be a community leader that represents the community’s interests and bargains for local infrastructure.

Clusters four and five are far smaller. However, we believe that they are still recognizable and convey meaningful types of clientelism. The fourth cluster is quite similar to the relational one, but with some additional features. The relation is also hierarchical, dyadic, and frequent, and the client obtains protection/insurance. But the relation has also a darker side: it involves coercion, mainly in the form of threats of violence. Moreover, the client does not provide a vote, but rather labor and loyalty. This cluster seems to capture a traditional type of clientelism, as discussed in Pellicer et al. (Reference Pellicer, Wegner, Benstead and Lust2017) and is related to “economic coercion” in clientelism as discussed by Mares and Young (Reference Mares and Young2019). This interpretation is reinforced by the context in which these relations take place: exchanges in this cluster are more likely to be rural, and to have been recorded in older papers (from the 1970s as opposed to the 1990s and 2000s as the other exchanges; refer to online appendix table G.2).

The fifth cluster shares with the traditional cluster the presence of coercion, but coercion in this case is mainly about threats of withdrawing benefits, rather than about threats of violence. Also, contrary to the traditional cluster this one is rather thin, not dyadic or affective and is restricted to politics. We believe this cluster seems to capture a modern form of coercive clientelism, similar to “policy coercion” studied in Mares and Young (Reference Mares and Young2019). Consistent with this interpretation, what the client tends to receive in this exchange more than anything else are government services. Because this is not a unique characteristic of this type of clientelism it is not salient enough to appear in table 1, but its importance can be seen in table G.1 in the online appendix.Footnote 14

The Individual-Universal and Equal-Unequal Dimensions of Clientelism

Our data contain eighteen variables. These are characteristics, or dimensions, of clientelism that describe a specific exchange with a fair amount of detail. To theorize about the welfare implications and trade-offs for clients, we need a more tractable framework. Our objective is to reduce the number of dimensions while preserving as much of the original richness as possible. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) achieves this, by combining variables into a few distinct components that together account for as much variation in the data as possible.

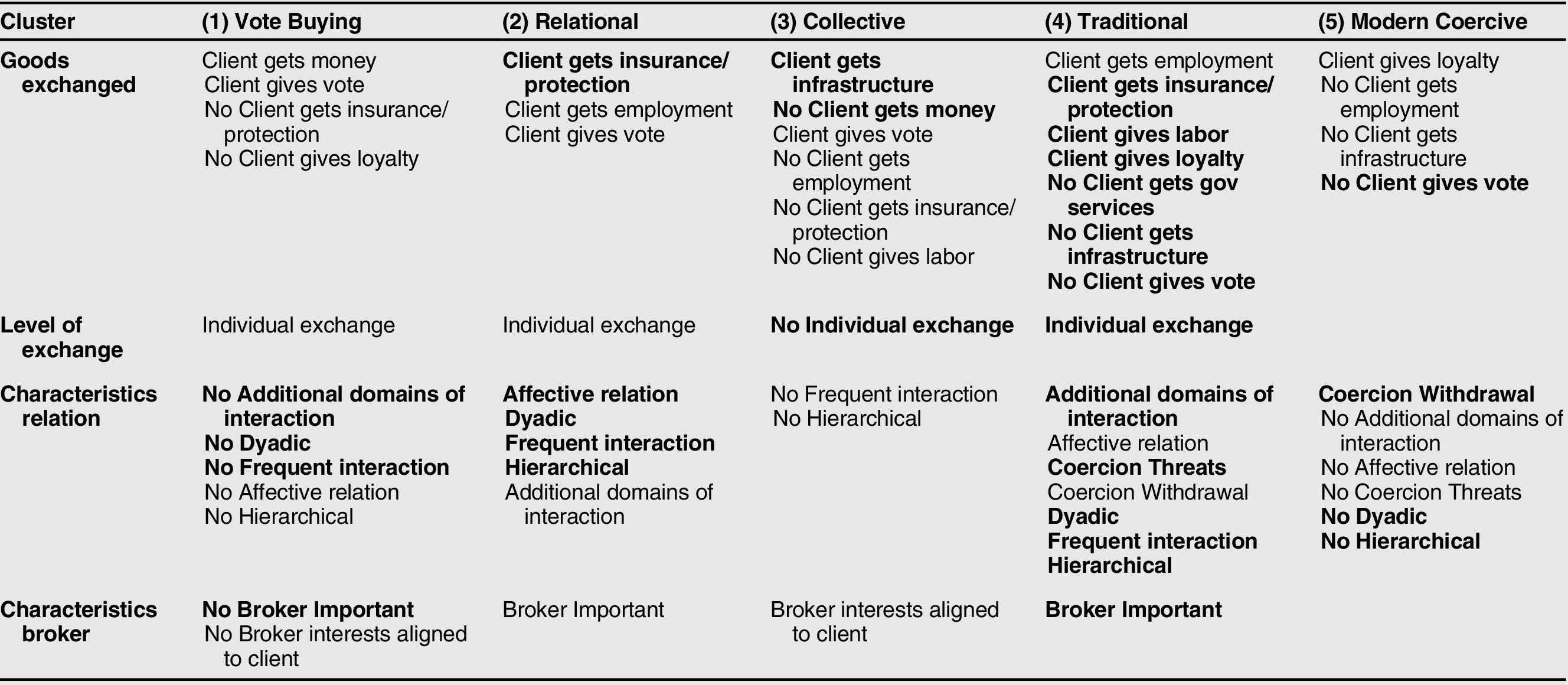

The PCA shows that two dimensions (down from eighteen) are sufficient to characterize the data while preserving a lot of its richness (refer to figure H.1 in the online appendix). The first two components of the PCA explain a large amount variation, while the third one adds comparatively little. We thus select the first two components of the PCA.

What do these two dimensions represent? Table 2 lists the variables that contribute most strongly to each of the two new dimensions.Footnote 15 We denote the first dimension, corresponding to the first component of the PCA, the Equal-Unequal dimension of clientelism. At the unequal endpoint of this continuum, clientelistic relations are hierarchical (the relation is judged as hierarchical, the broker is important); thick (frequent, dyadic, over several domains, involving affection); and the goods exchanged are valuable (clients get insurance/protection). At the equal endpoint of the continuum, relations are the opposite: non-hierarchical, thin, and with exchanges of less value. The fact that thickness and hierarchy combine into a single dimension (i.e., tend to go hand in hand) is a relevant result of the PCA. This makes sense in the context of political clientelism, where a key feature of the exchange is political support. There is only so much political support that a regular client (a citizen) can give to a patron/broker. When the relation is strong and the goods exchanged are valuable, it is difficult for the client to reciprocate. Accepting a clearly inferior position can be a way for the client to help fulfill her side of the exchange.

Table 2 PCA: Most important loadings

Note: (+) indicates that a variable loads positively on the component, (-) that it loads negatively on the component.

The second dimension of the PCA mainly captures the size of the client beneficiary group. We denote this dimension the Individual-Universal dimension of clientelism. More universal exchanges are at the group level;Footnote 16 clients get a collective good (infrastructure) and do not provide labor to the broker/patron. Interestingly, in the data, the larger size of a beneficiary group goes together with having brokers with interests close to those of the clients. This points to exchanges where clients are able to act collectively. In contrast, exchanges that are low on the individual-universal dimensions exchanges are individual and have brokers with political interests unrelated to those of the clients.

By construction, the two dimensions of clientelism arising from the PCA are linearly independent. This means that the two dimensions are entirely distinct: Clientelistic exchanges can simultaneously be high on the equal-unequal and individual-universal dimensions or low on both. For instance, a fully individual relation that is thin and non-hierarchical will be low on both the equal-unequal and individual-universal dimensions.

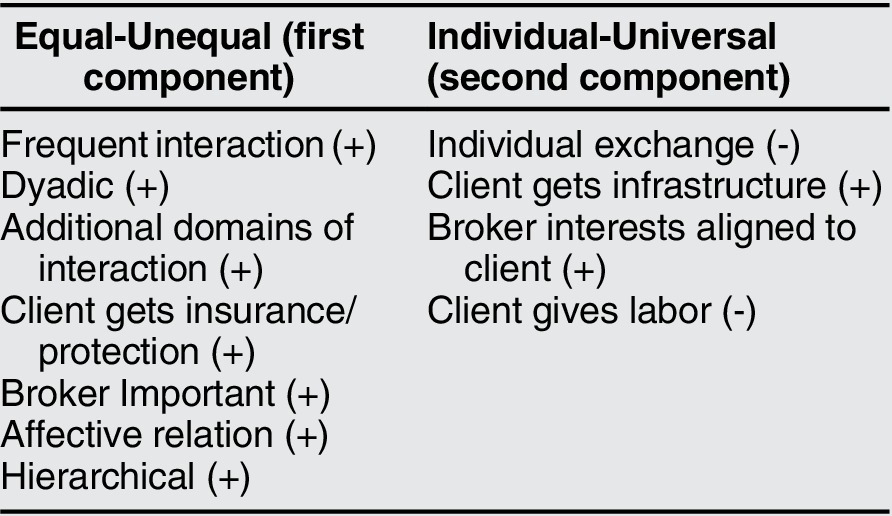

Putting it Together: Types of Clientelism on Two Dimensions

We put together the two types of analysis and represent the different types of clientelism that emerge from the cluster analysis on the two dimensions extracted from the PCA. Figure 1 shows the results. The figure shows that the three main clusters are placed at specific locations on the two dimensions. The placement is very sensible. The vote-buying cluster is placed at the bottom-left. This corresponds to a type of clientelism where the exchange has little inequality, but also little universality. Collective clientelism is placed at the right side: an exchange characterized by a higher degree of universality. Relational clientelism, a thicker and more hierarchical relation than vote-buying, is sensibly placed towards the top of the equal-unequal dimension. To make the dimensions and clusters more concrete, we identify well-known ethnographic works in the graph. We show the location of accounts of Auyero’s (Reference Auyero2000) “inner circle” clients in Argentina as a paradigmatic example of relational clientelism; of Gay (Reference Gay1999) on Brazil as an example of collective clientelism; and of Lazar (Reference Lazar2004) on Bolivia as an example of vote-buying. The figure shows that these paradigmatic accounts indeed represent relatively “pure” cases of each of the three types of clientelism.

Figure 1 The location of clientelism clusters on the two first PCA dimensions

Of the two smaller clusters (traditional and coercive clientelism), only the traditional cluster is placed clearly: this is the thickest and most hierarchical type of relation and is consequently placed even higher than relational clientelism at the very top of the equal-unequal dimension. The coercive cluster, in contrast, appears placed around the middle. The equal-unequal and individual-universal dimensions of clientelism do not seem to characterize coercive clientelism well. Footnote 17

Overall, the two dimensions perform well in distinguishing between the main subtypes of clientelism, even if our reduction of dimensions has been quite radical, from eighteen to two. The equal-unequal and individual-universal dimensions of clientelism seem to capture the essential features that distinguish the main types of clientelism. The clusters are of course not separate “islands” in the figures, implying that real instances of clientelism often share features of different types (for instance, clients often receive both money or little gifts for their vote and also some promise of infrastructure). This multi-faceted nature of clientelistic exchanges is reflected in our coding and thus appears in figure 1. The clusters may best be thought of as “ideal types” that embody a type of clientelism, as illustrated by the placement of paradigmatic ethnographic works.

The combination of our typology and the PCA results relates in a very sensible way to existing typologies in the literature. It is noteworthy that our fully inductive typology that is based on ethnographic work in different world regions gives rise to forms of clientelism similar to those identified in deductive approaches. The comprehensiveness and richness of our typology moreover allows us to reconcile different labels that have been applied across typologies. For example, our typology shows that from the point of view of the client, what Nichter (Reference Nichter2018) or Yildirim and Kitschelt (Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020) call relational clientelism and Stokes et al. (Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013) and Schaffer (Reference Schaffer2007) “patronage” corresponds empirically to a single broad type of clientelistic relation that has frequent interactions between patrons and clients and where relatively high-value goods such as insurance and employment are exchanged. In turn, collective clientelism combines pork (Schaffer Reference Schaffer2007; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013), meso-particularistic clientelism (Hutchcroft Reference Hutchcroft, Brun and Diamond2014), and ethnic/lobby exchanges (Hopkin Reference Hopkin2006), in that clients get local public goods and broker interests are aligned with that of the community.

Implications for Client Welfare and Client Trade-Offs

Client Welfare

Our systematization allows us to provide insights into the implications of different types and dimensions of clientelism for client welfare. There are two variables in our data that capture different aspects of the welfare evaluation of clients: the extent to which the client has agency and the extent to which she gets a good deal. It must be recalled, however, that these two welfare variables are very subjective and indeed showed lower inter-coder reliability. Therefore, the results should be considered as suggestive.

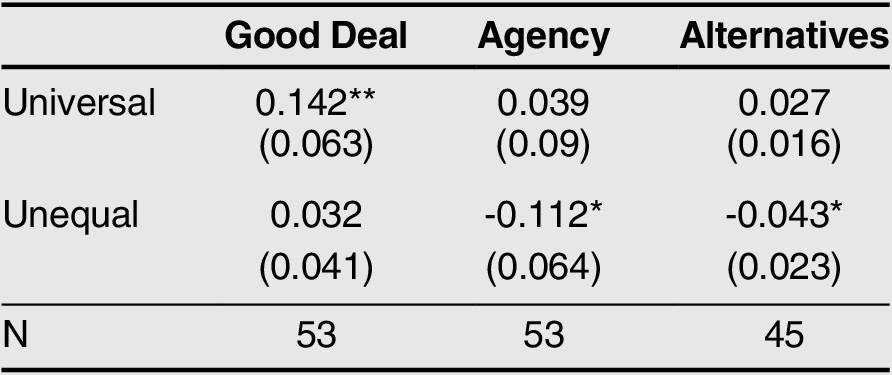

Table 3 shows how these two client welfare variables vary along the two dimensions of clientelism. The table also adds a third variable (whether the client has alternatives to the existing clientelistic relation or not) which we discuss later. The table shows the result of simple OLS regressions of the welfare evaluation variables on the equal-unequal and individual-universal dimensions. The patterns in the table are quite striking. Different dimensions are associated with different welfare aspects of clientelism. The equal-unequal dimension is negatively associated with client agency: unequal exchanges imply less agency. The individual-universal dimension is associated with clients obtaining a better deal out of the clientelistic relation. These results imply that different types of clientelism are associated with different welfare outcomes. And indeed, table A.3 in the online appendix shows that relational, traditional (and coercive) clientelism, which score high on the unequal dimension, feature less agency than the other two subtypes, whereas clients in collective clientelism get a particularly good deal.

Table 3 Clientelism dimensions and client welfare

Note: Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Signif. Codes: ** 0.05; * 0.1. “Universal” corresponds to high values on the Individual-Universal dimension (2nd component of the Principal Component Analysis). “Unequal” corresponds to high values on the Equal-Unequal dimension (1st component of the Principal Component Analysis). “Good deal” refers to how good a deal the client gets; and “Agency” refers to the agency of the client. “Good Deal” and “Agency” are coded with a scale from 0 to 4; Alternatives is coded as 1 if the client has alternatives to the current clientelistic relation, and 0 if not.

These results are insightful. Exchanges that score high on the individual-universal dimension involve a collection of clients voting for a patron via a broker with interests aligned to theirs. For the patron, these exchanges are valuable: the patron obtains a sizeable block of votes rather than one or a few. Moreover, since the broker interests are aligned with those of the clients, it is more likely that clients will indeed vote as a block. Since this is valuable for the patron, she needs to reciprocate with a fairly good deal for the clients as well.

Exchanges that score high on the equal-unequal dimension are characterized by a higher closeness and depth of the relation between clients and patrons; a relation in which better-quality goods are exchanged. It makes sense that this limits the agency of the clients in practice because such a bond effectively ties the client to the patron (see Zarazaga Reference Zarazaga2014 for a related point). Indeed, the third column in table 3 shows that unequal (and thick) exchanges also display fewer alternatives to the existing relationship for the client. In contrast, in more equal (and thinner) clientelistic exchanges, such as vote buying, the client has access to more alternatives.

What is possibly surprising in table 3 is that “agency” and “good deal” seem unrelated. We typically expect agency to be associated with a better deal for the client: agency would be associated with more choice, more bargaining power, and thus a better deal for the client. Indeed, the literature has shown that more competition among patrons implies more agency and a better deal for the client (Corstange Reference Corstange2016, Reference Corstange2018; Shami Reference Shami2012). A priori, we would expect exchanges that restrict the agency of the client (unequal, thick exchanges) to be associated with a worse deal.

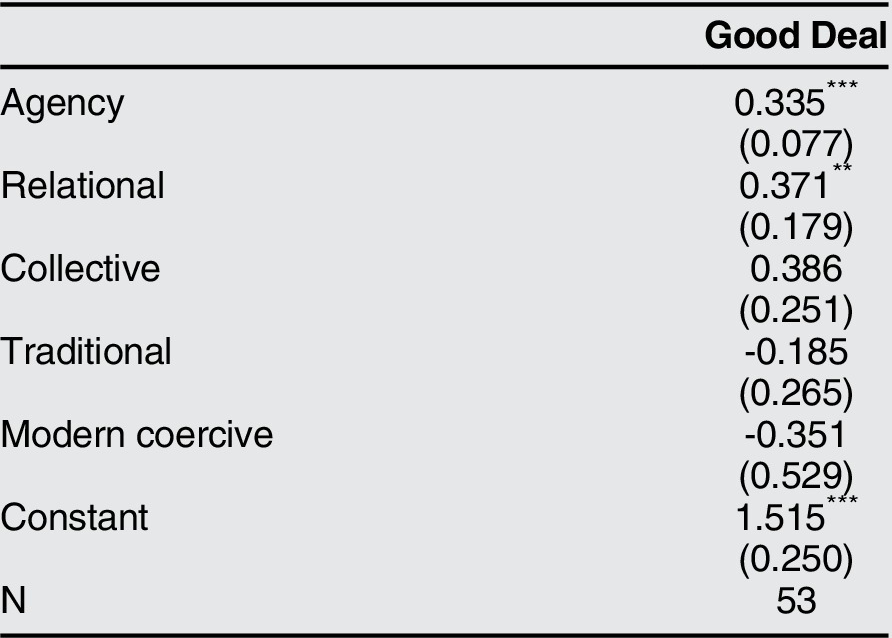

Interestingly, in our data, we find that this argument holds within types of clientelism, but not between types. Table 4 shows how agency and “good deal” correlate within clientelistic types. This is operationalized as a OLS regression of good deal on agency, controlling for the different clusters. The table shows a strong positive relation between the agency and the good deal variables within clientelistic types, implying that for a given type of clientelism, more client agency indeed results in a better deal.

Table 4 Agency and good deal within types of clientelism

Note: Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Signif. Codes: * 0.1; ** 0.05; *** 0.01. Omitted type: Vote-Buying.

Given this, why is it then that more unequal and thicker clientelistic types involve less client agency, but this does not get translated into a worse deal for the client? We argue that the very nature of the exchange, in particular its thickness, enables for better quality goods to be exchanged. The patron provides better quality goods to the client because the patron can trust the reciprocity of the client (Nichter and Nunnari Reference Nichter and Nunnari2019). This implies that in unequal exchanges, clients do not get a particularly bad deal despite their lower agency.Footnote 18

Client Trade-Offs of the Equal-Unequal and Individual-Universal Dimensions of Clientelism

Our analysis allows us to theorize about the trade-offs that prospective clients face and about the factors that affect these trade-offs and choices. In the standard model of clientelism, the main trade-off for the client is between deriving an expressive benefit from supporting a political program versus obtaining individual material goods from engaging in clientelism (Dixit and Londregan Reference Dixit and Londregan1996; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013). This characterization implies that a crucial factor affecting citizens’ preferences and attitudes towards clientelism is poverty, and to a certain extent, risk aversion and mistrust of politicians: poorer citizens would be more prone to engage in clientelism because their higher marginal utility of income makes them value the material benefits from clientelism more strongly.

While poverty, risk aversion and trust are likely to impact demand for clientelism, the ethnographic work provides little evidence that giving up the expressive benefit of supporting a different party matters for clients; less than 10% of the ethnographic papers considered in our study mention such a trade-off. Our analysis allows us to move beyond the simple trade-off between expressive benefits and clientelism. Most crucially, our analysis implies that different dimensions of clientelism involve different trade-offs and are thus driven by different factors from the client point of view.

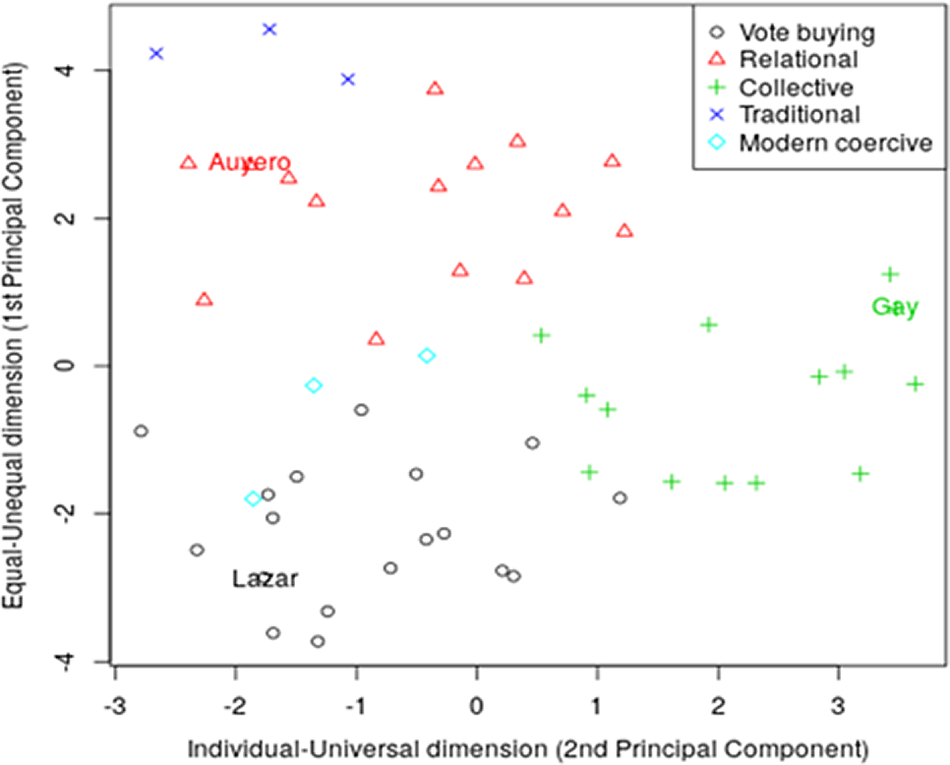

Figure 2 depicts a schematic representation of the two dimensions of clientelism, including the subtypes of clientelism, and the trade-offs and factors associated with each dimension. Again, we leave coercive clientelism aside because it is not well captured by the two main dimensions.

Figure 2 Trade-offs of the equal-unequal and individual-universal dimensions of clientelism

Equal-unequal dimension trade-offs

We propose that the equal-unequal dimension is associated, from the client point of view, with a trade-off between insurance and autonomy/subordination. For clients, the benefit of more unequal types of clientelism is that they can provide clients with very valuable goods: employment, insurance, or protection as shown in the clusters that scored high on the equal-unequal dimension. The cost for the client is that these types of clientelism require the client to be in a subordinate position and to relinquish autonomy (less agency, as shown in the results on client welfare). Thus, relative to relational and traditional clientelism, vote-buying gives little to the clients but also affords them more autonomy and less subordination.

This conceptualization of the equal-unequal dimension can also incorporate programmatic politics, at the very bottom of the equal-unequal axis (see figure 2). Programmatic politics ideally represents even less subordination and more autonomy than vote-buying. In programmatic politics, the pattern of subordination between politicians and citizens is (ideally) reversed: instead of the client serving the patron, it is the politician who is supposed to “serve” the people.

This conceptualization implies that demand for types of clientelism that are high on the equal-unequal dimension will be high in contexts where insurance and protection are very valuable, or when autonomy is not feasible or not very valuable. Accounts of relational and traditional clientelism, the two types of clientelism that are higher on the unequal dimension, suggest that this interpretation of the trade-off for clients is sensible (Landé Reference Landé, Schmidt, Guasti, Landé and Scott1977; Nichter Reference Nichter2018).Footnote 19

This suggests that demand for unequal types of clientelism is driven by factors that relate to risk, or to autonomy/subordination. Risk-related factors include the presence of strong political and economic risks, the absence of social insurance mechanisms, and a citizen’s general risk aversion (Landé Reference Landé, Schmidt, Guasti, Landé and Scott1977; Nichter Reference Nichter2018). Autonomy-/subordination-related factors can have a material/practical side, such as the isolation that renders clients economically dependent on patrons (Shami Reference Shami2012); and a psychological/attitudinal side, such as aversion towards subordination or inequality (Pellicer et al. Reference Pellicer, Wegner, Benstead and Lust2017; Shefner Reference Shefner2001).

Individual-universal dimension trade-offs

For citizens, the individual-universal dimension is associated with a trade-off about the value of supporting distributive politics of different scopes. At the narrowest level at the left side of the horizontal axis is a strictly personal benefit (see figure 2). This corresponds to vote-buying. The next level concerns one’s own group, leading to demand for local particularistic goods, as in collective clientelism. This axis can be extended further to the right to accommodate a situation where the policy change considered is the broadest, about society in general, which corresponds to programmatic politics.Footnote 20

For the client, the main trade-off associated with the individual-universal dimension is between certain concrete but small rewards of narrow scope versus uncertain, diffuse, but potentially large rewards of broader scopes. This trade-off accommodates the standard model of clientelism. The standard model focuses on the extremes of the horizontal axis: the individual (usually small) material benefits of vote buying vs. the expressive benefits from programmatic politics. Our characterization focuses on the entire axis, and this allows us to conceptualize this trade-off more broadly.

What factors contribute to demand for a narrow scope of politics such as vote-buying as opposed to broader politics, such as collective clientelism or programmatic politics? First, attitudes towards the self versus the community versus society, group identity and social and political preferences are likely to affect demand for different scopes of politics. If individual utility weighs very strongly relative to social preferences, then broader scope politics are less rewarding, and this drives demand for narrow forms of politics. This can be because of high individual marginal utility (from poverty) as in the standard model, but it can also be because of low altruism, a belief that politics is about “dividing the pie” rather than the common good, or weak group identity (Van Zomeren, Postmes, and Spears Reference Zomeren, Martijn and Spears2008).

A second important driver of the individual-universal trade-off relates to the supply side of formal politics. For citizens to choose programmatic offers over individualistic ones, they must believe that the political system is responsive to their demands (political efficacy) and that politicians can be trusted. Crucially, citizens must also believe that there are credible programmatic alternatives to clientelism. In this respect, it is worth emphasizing that in less than 10% of the exchanges we coded from ethnographic work, a non-clientelistic party with an attractive program was mentioned as an alternative. So even if citizens view programmatic politics as superior to particularistic exchanges, beliefs about the responsiveness and the existence of alternatives will impact strongly on their evaluation of the trade-offs of the individual-universal dimension.

Collective clientelism is located towards the middle of the individual-universal dimension and corresponds to the intermediate cases of the mentioned factors. Collective clientelism implies intermediate social identities and social preferences (group-based, in between individual and society). And collective clientelism requires more citizen coordination and greater trust in politicians than selling a vote in a direct exchange. It would thus be more likely in situations where citizens are able to engage in some degree of collective action and where there are politicians capable and willing to make good on their side of the deal and deliver collective goods.Footnote 21 However, because the group is smaller and the exchange more localized, collective clientelism requires less coordination and trust than voting for policy changes at the society level.

Poverty and Clientelism

As mentioned earlier, poverty emerges from the standard framework of clientelism as a crucial determinant of demand for clientelism. It is indeed widely observed that clientelism is positively associated with poverty (although see Kao, Lust, and Rakner Reference Kao, Lust and Rakner2017). However, there is to our knowledge no direct evidence that such connection is mediated by the higher marginal utility of individuals with less income, as suggested by the standard model.

Our framework implies that poverty can affect the demand for different types of clientelism through various channels in addition to the standard channel via the marginal utility of income (or risk aversion; see Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013). In the individual-universal dimension, poverty is related to several factors driving preferences over narrow versus broad scope politics, such as political efficacy or group identity. For political efficacy, poverty would typically lead to preferences for narrow, as opposed to broad, scope of politics, and thus go in the same direction as the standard channel. However, the effect of poverty through group identity can be different and non-linear. This is indeed what research on the psychology of poverty suggests: Poverty is associated with stronger group cohesion (or group identity), but also with more suspicion towards outsiders (Sheehy-Skeffington and Rea Reference Sheehy-Skeffington and Rea2017). Thus, poverty could be associated with a heightened demand for collective clientelism as opposed to either vote-buying or programmatic politics. This perspective could reconcile some contrasting findings in the literature on how poverty is linked to the demand for clientelism. Most studies linking poverty and vote-buying find a positive effect of poverty on vote-buying (Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013; Stokes Reference Stokes, Boix and Stokes2007). Kao, Lust, and Rakner (Reference Kao, Lust and Rakner2017) in contrast, find that the poor tend to dislike vote-buying more than the middle classes when compared to a platform that resembles collective clientelism. Our perspective can reconcile these findings by noting that poverty may increase the demand for vote-buying relative to fully programmatic politics but decrease it relative to the demand for collective clientelism.

Our framework also implies that poverty can affect demand for clientelism along the equal-unequal dimension. Poverty may heighten the vulnerability to negative shocks and make protection/insurance more valuable. Or poverty may lead to psychological adaptations conducive to legitimize inequalities and accept hierarchical relations (Pellicer Reference Pellicer2018; Pellicer et al. Reference Pellicer, Wegner, Benstead and Lust2017; Van der Toorn et al. Reference Toorn, Jojanneke, Jost, Kay, Tyler, Willer and Wilmuth2015). Through these two channels, poverty would increase demand for equal-unequal types of clientelism (traditional, relational) as opposed to vote-buying.Footnote 22

This discussion on the role of poverty for demand for clientelism illustrates how the richer framework of client choice that emerges from our meta-analysis can bring a fresh perspective to perennial questions in the study of clientelism.

Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we have conducted a meta-analysis of more than forty ethnographic papers on clientelism with a focus on the client perspective. Applying cluster analysis to the coded data, we have provided a typology of clientelism. Our systematization naturally entailed a great loss of richness relative to the original ethnographic works and cannot account for the dynamic nature of many clientelistic relations and settings. However, we believe that uncovering important commonalities between clientelistic exchanges described by different authors in different parts of the world is a useful contribution. The typology we have derived from these exchanges comprises specific subtypes of clientelism that are similar to those emphasized by different authors in the recent literature, such as relational, traditional, and coercive clientelism. Different from these existing typologies, our typology is derived inductively from exchanges described by many different authors in different contexts. Moreover, contrary to other typologies that are mostly inspired by the patron side, our typology captures aspects of the clientelistic relation that matter for clients.

An important novel aspect of our work is the identification of two fundamental dimensions of clientelism from the client perspective: the equal-unequal dimension and the individual-universal dimension, capturing the hierarchy and thickness of the relation on the one hand, and the extent of its collective nature on the other. Together, these dimensions explain much of the variation in the eighteen variables we originally used to describe clientelistic exchanges. Moreover, these two dimensions seem analytically powerful. As we have shown, these dimensions intuitively disentangle the different types of clientelism derived in the cluster analysis, are linked to different welfare implications for the client, and imply different trade-offs for the client.

Recent evidence on vulnerability and clientelism by Bobonis et al. (Reference Bobonis, Gertler, Gonzalez-Navarro and Nichter2017) lends some additional empirical support to our distinction between the two dimensions of clientelism. They find that reducing the vulnerability of citizens to negative weather shocks in Brazil reduces needs for insurance and consequently has an impact on the equal-unequal dimension (reduces relational clientelism). However, they also show that such intervention does not lead to a higher demand for public goods and thus has no obvious impact on the individual-universal dimension. This provides support for our basic contention that the two dimensions of clientelism are driven by different factors. More generally, this evidence underscores the idea that, from the client perspective, clientelism involves more than a single trade-off between material benefits versus expressive benefits from programmatic politics.

The distinction between the two dimensions of clientelism can also put structure into the different ways in which clientelism is usually considered to be normatively negative. First, clientelism is often evaluated negatively because of its association with inequality (Pellicer Reference Pellicer2009). This corresponds to the equal-unequal dimension. At one extreme are unequal types of clientelism (relational and traditional) where relations are very hierarchical, the client loses autonomy, and is supposed to serve her patron. At the other extreme is programmatic politics where, as we have argued, the hierarchy is reversed, with the politician “serving” the voter. Second, clientelism is often evaluated negatively for its particularistic nature and the resulting under-provision of public goods (Keefer and Khemani Reference Keefer and Khemani2004, Reference Keefer and Khemani2005). This corresponds to the individual-universal dimension. Here vote-buying is one extreme case, an exchange where rewards are purely individual. The other extreme is again programmatic politics, which are driven by the pursuit of the common good and associated with the provision of public goods.

The research in this paper was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the project “The Demand Side of Clientelism”. The authors would like to thank participants and discussants of the 2018 Workshop “The Demand Side of Clientelism: Agency, Trade-Offs, and Welfare Implications” at the University of Duisburg-Essen, the 2018 ECPR Joint Sessions, and at the 2018 EPSA, APSA, and PSAI Annual Meetings for very helpful comments and suggestions. They would also like to thank the editor of Perspectives on Politics and four anonymous reviewers for excellent feedback on the original manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A. Tables

Appendix B. List of Coded Articles and Description of Selection Procedure

Appendix C. Coding Ethnographic Literature—Codebook

Appendix D. Descriptive statistics

Appendix E. Data Interpretation Challenges

Appendix F. Choosing the Number of Clusters

Appendix G. Clusters

Appendix H. PCA results

Appendix I. Cluster Analysis without Indonesia Chapters

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S153759272000420X.