When COVID-19 began turning everyday activities into life threatening choices, people at the economic and racial margins of American society felt the brunt of the pandemic most acutely. Khary, a 40-year old Black man who earns his living as an Uber driver in New York City, was one of millions of workers displaced by a reeling economy. “It seems like it’s a choice between money and your life,” he noted of the decision about whether to continue working as a rideshare driver (Michener Reference Michener2020). After a few days of wavering, he stopped taking passengers, explaining, “I’m just going to choose my health.” The difficulty of this choice hinged on Khary’s experience of the safety net as absent and unreliable. In pre-pandemic times, he earned slightly too much to qualify for most government benefits. After the pandemic, when his income had dropped precipitously, he spent hours on the phone trying to reach someone to help with his unemployment application. That effort was to no avail. He was not able to receive benefits. By May 2020, with COVID-19 still threatening the health of the country, he returned to work, concerned about his exposure to the virus but even more preoccupied with his material survival.Footnote 1

Khary’s story and so many others that have emerged in the wake of COVID-19 bring into sharp relief the stakes of properly conceptualizing and studying the welfare state. When tens of millions of people lose their jobs in an instant, when it is unclear how they will pay rent, keep food on the table, care for their children, heat their homes, and recover from the blow of a prolonged public health crisis—the welfare state is imperative. Placing the modifier “welfare” before “state” denotes emphasis on those institutions and structures most directly concerned with securing and protecting the economic wellbeing of members of the polity. The programs and policies associated with this facet of the state are supposed to provide for a minimum standard of living, a modicum of protection against the losses that result from the ebb and flow of the economy, and the resources for social mobility. These functions of the welfare state revolve around real people like Khary, their lived experiences, and the very meaning of citizenship and social rights in a democratic polity.

Because the welfare state is so vital, the ways scholars choose to study it are crucial. In particular, the tendency of mainstream political science to explore the welfare state from the perspective of elite actors and institutions in lieu of people like Khary has considerable consequences for our (mis)understanding of welfare state politics and the politics of marginalized groups in American society more broadly. To this end, we offer a reconceptualization of the welfare state, with an eye toward the limits of current scholarly approaches. Our reconceptualization does not provide a novel definition of the welfare state or recast it in new historical terms; we rely and build on prior work for such matters. Instead, at the heart of our contribution is the claim that political scientists ought to define the scope and empirical substance of their inquiries into the welfare state not solely from the vantage point of policy makers and elite institutions, but also from the perspective of denizensFootnote 2 like Khary, those at the proverbial “bottom,” who face substantial disadvantages within contemporary social structures and navigate a distinct constellation of public policies as they attempt to secure their welfare.

As we mean it here, “bottom” does not signify any judgment about value or significance. Instead, it indicates a difference in positioning. We conceive of this positional category capaciously, with a focus on two specific meanings. First, people at the “bottom” (or at the “margins”) are those for whom state power is marshalled in response to vital needs and to whom the repercussions of state power flow. They are those whose material lives are at stake. In this sense, a bottom up approach to welfare state scholarship begins by applying a person-centered lens: considering the welfare state through the eyes of those who experience it and not those traditionally understood to control it. Second, we use “bottom” to refer to those for whom the functions of the welfare state are most crucial for day to day survival and thriving. Most obviously this includes people who are marginal in various respects—those living in poverty, disproportionately beholden to economic shifts, and experiencing otherwise precarious lives (Pimpare Reference Pimpare2007a, Reference Pimpareb). Expanding even further, the “bottom” also comprises people who have secured “working class” or “middle class” status, but whose continued stability and economic positioning relies substantially upon the choices made by elites who determine the reach and generosity of welfare state provisions (Michener Reference Michener2017).

We argue that identifying and exploring the welfare state from the perspective of those who rely on it can productively reorient research on social policy and politics by expanding the boundaries of what we consider a part of the welfare state and its related political dynamics. The benefits of widening our theoretical ambit in this way are numerous and significant. A “bottom-up” view of the welfare state opens up new and less traveled policy terrain, illuminates how demands from below can catalyze policy innovation and diffusion, provides critical insight into how people perceive government and respond accordingly, prompts more varied and creative methodological and data collection approaches, and sensitizes us to a wider range of actors in the policy process. Altogether, studying the welfare state as we propose in this article enables political scientists to see, study, and understand parts of American political life that are often obscured.

Studying the Welfare State: Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches

The state, broadly speaking, is a category of analysis that provides scholars with conceptual leverage for more effectively understanding the political world, but it does not lend itself to simplistic characterization. Fundamentally, however, studying the state necessitates looking somewhere at something. The most crucial decisions scholars face when delineating the welfare state concern where to look and what to look for. We follow Sparrow, Novak, and Sawyer (Reference Sparrow, Novak and Sawyer2015, 5) in noting that scholars often (and understandably) search for the state “in the concrete and historical sites where power originates.” Indeed, as scholars have traversed the extensive and varied terrain of American state power, much of this work has emphasized what we consider a “top-down” approach, locating the state by identifying the origins of power seated in the hands of political and economic elites and manifested in the workings of formal political institutions (Skowronek Reference Skowronek1982; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2002; Sparrow, Novak, and Sawyer Reference Sparrow, Novak and Sawyer2015; but for a contrasting perspective see Nackenoff and Novkov Reference Nackenoff and Novkov2014, Pimpare Reference Pimpare2007b). By contrast, the bottom-up approach we propose roots analyses in the people whose needs (ostensibly) motivate the organization of a welfare state in the first instance. Charting the path of the welfare state by tracing the human needs that give rise to it points us away from elites and towards the people who actually live with the consequences of elite decision-making. This is a crucial step because it links theorization of the welfare state to the concrete realities that define and structure the lived experiences and political positioning of those who are most frequently the targets of its policies.Footnote 3

Often, these tasks have been divided along disciplinary lines. Sociologists, historians, and even economists have been most likely to attend to the details of how particular policies affect the lives of people at the margins (e.g., Currie Reference Currie2008; DeLuca, Clampet-Lundquist, and Edin Reference DeLuca, Clampet-Lundquist and Edin2016; Desmond Reference Desmond2016; Edin and Shaefer Reference Edin and Shaefer2015; Halpern-Meekin et al. Reference Halpern-Meekin, Edin, Tach and Sykes2015; Hays Reference Hays2004; Katz Reference Katz1996). Political scientists have produced distinct and largely disconnected research with a more macro-level, “top-down” focus (e.g., Hacker Reference Hacker2002, Reference Hacker, Binder, Rhodes and Rockman2006; Howard Reference Howard1997, Reference Howard2007; King and Lieberman Reference King and Lieberman2009; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2002; Mettler Reference Mettler2011; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992). To be sure, some political scientists have done work that centers people at margins, to advance knowledge of social policy and the welfare state (e.g., Jordan-Zachery Reference Jordan-Zachery2009; Soss Reference Soss2002; Michener Reference Michener2018; Pimpare Reference Pimpare2011; Thurston Reference Thurston2018). Nevertheless, the hallmark of much prevailing welfare state scholarship has been an emphasis on policies that elites define as serving a welfare function (broadly construed). For example, political scientists have followed elite cues by defining welfare state policies in terms of their fiscal form and impact, largely neglecting programs that do not appreciably affect taxation and spending (Mettler Reference Mettler2011; Faricy Reference Faricy2015).

We view such tendencies as shaped by two developments. The first is the intellectual lineage of much political science work on the American welfare state out of an earlier, comparatively oriented project. There, the welfare state was typically conceptualized as a state-managed response to a variety of economic, social, and political pressures. This orientation was aligned with the goals at the time: to understand the origins and features of a new type of social citizenship (Marshall Reference Marshall1950); to understand the diverse set of responses to common challenges posed by industrialization (and later deindustrialization) and urbanization (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944; Wilensky Reference Wilensky1975), as well as the complementarities that emerged between modern systems of social protection and political economic systems (e.g., Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Mares Reference Mares2003; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019); and to consider the role of various social actors, including labor movements, left-parties, corporatist bargaining partners, or religious actors in producing divergent social policy outcomes (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001). This large and luminous volume of work points to the fruitfulness of a top-down conceptualization of welfare, particularly when distinguishing across national models (e.g., Esping-Andersen and Korpi Reference Esping-Andersen and Korpi1984; Hicks Reference Hicks1999; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Mares Reference Mares2003; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019); Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990). And yet, political scientists have in recent decades come to recognize the limitations of an approach centering a specific Western European type of social provision and overlooking alternative modes of delivery including employers, the tax code, and credit systems (e.g., Howard Reference Howard1997, Reference Howard2007; Gottschalk Reference Gottschalk2000; Hacker Reference Hacker2002; Morgan and Campbell Reference Morgan and Campbell2011; Mettler Reference Mettler2011; Quinn Reference Quinn2019).

While this first development arose as a by-product of considering the United States in comparative (often Western European) perspective, the second appears more as a function of the U.S. context. The American system of social welfare evolved from one characterized by a patchwork of voluntary private agencies and social workers towards a larger and more rationalized form of bureaucratic provision (Katz Reference Katz1996; Trattner Reference Trattner1999). State actors turned toward new tools of management, rendering the diversity of users into commensurable categories, calling for the collection of statistics, and the development of practices and programs that could be carried out on a more generalizable scale (e.g., Gordon Reference Gordon1995). The need for a professional cadre of managers and providers, as well as for ways of measuring and providing services on such a large scale, may have in turn shaped scholars’ orientation towards the welfare state as something to be understood from the perspective of those doing the managing (Clemens Reference Clemens, Morgan and Orloff2017).

This orientation has consequences for how we describe and analyze welfare state politics. Descriptively, it tends to obscure aspects of the welfare state that are not connected to large or politically salient policies identifiably taken up by elites (like Social Security, Medicare, the GI Bill, tax credits, etc.). Many policies that are vital in the lives of people at the racial or economic margins of American society are too often obfuscated when scholars theorize the welfare state from the top down (notable exceptions include Canaday Reference Canaday2009; Soss Reference Soss2000; Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011).

One example is housing policy, whose cross-national variability and specificity led some of the most ambitious comparative welfare state scholars to overlook or consciously exclude it from their frameworks (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Wilensky Reference Wilensky1975, 7-9).Footnote 4 Yet ethnographic work has clearly revealed how housing access, affordability, and stability remain key sources of concern to lower income and marginalized citizens, and are tightly connected to individual and familial well-being (Desmond Reference Desmond2016; Edin and Shaefer Reference Edin and Shaefer2015). Recent insights on predatory inclusion—whereby groups who were previously excluded from homeownership and higher educational opportunities find themselves formally included, but on a risky basis—serve, moreover, as a reminder that simple metrics of inclusion can mask differences in risk protection and exposure (Addo, Houle, and Simon Reference Addo, Houle and Simon2016; Taylor Reference Taylor2019). In short, by examining the welfare state from the bottom up, we bring attention to these otherwise underattended policy areas and their distributional consequences, thereby opening up space for richer and more nuanced thinking about how policies and political institutions work in the lives of a wider set of people.

Beyond expanding the range of policies and their distributional outcomes, theorizing (and then studying) the welfare state from the bottom up can also improve our understanding of welfare state politics. As we will illustrate, answers to key questions may change when we center marginalized groups; first, by illuminating how demands from below can lead to policy innovation and diffusion; second, by providing new insights into how people perceive the role of the government in their lives and the political consequences thereof; and third, by opening up less-studied sites of policymaking and provision.

First, policy innovation, change and diffusion can emerge from the demands and actions of marginalized groups, a possibility that even more recent “policy-focused” examinations of American politics have tended to downplay (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2014; Bawn et al. Reference Bawn, Cohen, Karol, Masket, Noel and Zaller2012), despite a rich historical literature addressing such activism and entrepreneurial behavior from the margins (e.g., Orleck Reference Orleck2005; Nadasen Reference Nadasen2005; Kornbluh Reference Kornbluh2007). Political scientists have also begun to make inroads into some of these issues. To return to housing, Thurston (Reference Thurston2018, chap. 6) demonstrates the role of bottom-up work organized by the National Council of Negro Women in developing a program administratively through the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which enabled families poor enough to qualify for public housing to become homeowners, culminating in over 100,000 units of housing across the country by the early 1970s. This emerged out of local concerns raised in workshops convened across Mississippi in 1966 and 1967, and entailed navigating a political economy and “white power structure”—to quote one of the organizers—that was indifferent-to-hostile to the demands of poor, Black, largely female constituents (Blackwell Reference Blackwell2006, 186).

Second, a bottom-up approach can catalyze new insights into the feedback effects of public policies—especially for those at the margins. Political scientists have found ample evidence that public policies, particularly those that become durable features of the political landscape, have the capacity to shape the future politics of individuals, interest groups, and policy elites in a variety of ways (Lowi Reference Lowi1972; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992; Pierson Reference Pierson1994, Reference Pierson2001; Mettler and Soss Reference Mettler and Soss2004; Mettler and SoRelle Reference Mettler, SoRelle, Weible and Sabatier2017; Michener Reference Michener2019b). These policy feedback effects, which stem from the design, visibility, and implementation of government programs, can shape people’s conceptions of their own citizenship, their preferences for government intervention, and broader patterns of claims making.

A bottom-up approach draws attention to the way some of the assumed pathways of policy feedback, particularly government visibility and citizens’ attribution of the role of the government in their lives, may operate differently for citizens who are excluded, included on a predatory or coercive basis, or otherwise marginalized. For example, Barnes and Henly (Reference Barnes and Henly2018) find modest ethnic and racial differences in how citizens attribute administrative burdens in the case of childcare subsidies, while Rosenthal (Reference Rosenthal2020) recovers substantial heterogeneity in the areas of the government that are visible to white and nonwhite citizens.

Such divergent experiences can lead to forms of policy feedback that have been underexplored by top-down scholarship. For example, Thurston (Reference Thurston2015) uses a bottom-up approach to show that, while submerged state institutions may obscure the link between the government and on-the-ground outcomes for many policy beneficiaries, they can also heighten visibility and awareness of the government’s role in exclusion among people at the margins, opening new space for political mobilization. In short, organizations representing marginalized or excluded groups can and have drawn attention to submerged state institutions as a rallying call and basis for claims-making. Posey (Reference Posey2019), also by taking a bottom-up approach, arrives at the idea of “paradoxical feedback effects,” of fringe financial institutions for neighborhoods, whereby the increase in resources coming from having access to fringe financial institutions is offset by the sense of abandonment that their presence reinforces. And SoRelle (Reference SoRelle2020) uses this approach to demonstrate that socioeconomically marginalized borrowers are more responsive to appeals for political action to support lending reform than are their more affluent, white peers.

Finally, we maintain that a bottom-up approach can improve political scientists’ understanding of the politics of social policy by redirecting their attention towards overlooked arenas and forms of political conflict. Recent work in the legal field, for example, has noted how marginalized groups can leverage the notice and comment period of regulatory rulemaking to achieve political gains in the welfare state (Cortland and Tani Reference Cortland and Tani2019; Jarlenski et al. Reference Jarlenski, Rocco, Tipirneni, Kennedy, Gunturi and Donohue2017). Similarly, Michener (Reference Michener2019a) identifies the power that community organizers and their members have in shaping local welfare politics through grassroots movements to demand a right to civil counsel.

In the sections that follow, we offer a bottom-up theorization of the welfare state, and we discuss strategies and obstacles to implementing this approach in political science scholarship. A view of the American welfare state from the bottom helps us to see the many ways that the state multiplies in the lives of those who are less advantaged. This is already recognized by scholars of the carceral state as well as those focusing on the more coercive aspects of what is colloquially known as “welfare” (Piven and Cloward Reference Piven and Cloward1971; Page, Piehowski, and Soss Reference Page, Piehowski and Soss2019; Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2010; Pimpare Reference Pimpare2011; Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017; Wacquant Reference Wacquant2009). Going further, however, our arguments invite political scientists to contend with the operations of the state in the lives of people on the margins, even vis-à-vis its putatively “welfare enhancing” components (those believed to be non-coercive, non-punitive, and more focused on social provision than social control). Doing so pushes us to grapple most comprehensively with the reality that, “it is the multiplication of authority, not its reduction to one singular, centralized sovereign that most distinguishes American statecraft” (Sparrow, Novak, and Sawyer Reference Sparrow, Novak and Sawyer2015, 1).

Defining the Welfare State

We begin our exercise in constructing a bottom-up approach to the welfare state by considering what types of welfare policies and attendant politics emerge from prevalent top-down theorizations, why, and what is missing. While no single definition of the welfare state materializes across the literature, scholars collectively suggest three important aspects of welfare policy reflected in the answers to three key questions. First, what is welfare policy designed to do; what goal is it intended to achieve? Second, what role does the state play in creating and administering welfare policy? Third, who benefits from (or is burdened by) welfare policy?

Policy Goals

The first substantive question that theories of the welfare state grapple with is what, exactly, a welfare policy is designed to achieve. Scholars have imagined several positive policy goals consistent with promoting the general welfare of citizens.Footnote 5 Perhaps welfare policy is meant to meet basic needs. This, according to Esping-Anderson (Reference Esping-Andersen1990), was a common approach to defining welfare policies in early scholarship. Such studies focus on policies that provide basic income programs or transfers to assist with housing, food, childcare, and other essentials (e.g., Lubove Reference Lubove1968; Orloff Reference Orloff, Weir, Orloff and Skocpol1988; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992; Morgan Reference Morgan2006; Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011). Alternately, welfare could be something that helps secure against risk or life shocks (e.g., Titmuss Reference Titmuss1958; Wilensky Reference Wilensky1975). In the latter account of welfare policy, programs like unemployment and health care (e.g., Hacker Reference Hacker2002; Campbell Reference Campbell2003; Michener Reference Michener2018) take center stage. A third and most expansive goal for welfare policy is to promote socioeconomic mobility—either intra- or inter-generationally (e.g., Beller and Hout Reference Beller and Hout2006; Tranby Reference Tranby2006; Palme Reference Palme2006; Korpi and Palme Reference Korpi and Palme1998). This third kind of welfare policy might focus on educational benefits (e.g., Mettler Reference Mettler2005; Rose Reference Rose2018) or programs to assist homeownership (e.g., Thurston Reference Thurston2018). Each of these three goals can manifest in dramatically different public programs that share the moniker “welfare policy.”

The Role of the State

The next question scholars wrestle with is what role the state plays in making and implementing welfare policy. We might think of the state’s role in two distinct, but equally significant ways. First, to what extent is the state directly involved in the provision of welfare? Early accounts of welfare policy center government’s role both in creating programs and administering benefits directly to recipients. These accounts typically focus on the politics of cash transfer programs like public assistance (e.g., Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992; Soss Reference Soss2000), pension schemes like Social Security (e.g., Derthick Reference Derthick1979; Beland Reference Beland2005), and other forms of welfare wherein states directly interact with beneficiaries. More recently, however, scholars have challenged the notion that welfare policy requires a direct link between states and citizens, pointing to a variety of policies in which government resources are funneled to beneficiaries indirectly through market mechanisms (e.g., Howard Reference Howard1997; Hacker Reference Hacker, Binder, Rhodes and Rockman2006; Soss et al. Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011; Mettler Reference Mettler2011; Faricy Reference Faricy2015; Quinn Reference Quinn2019). Exploring a variety of welfare benefits provided through tax incentives, subsidies to employers, and other indirect pathways, these studies begin to paint a more complex image of the state’s role in providing welfare benefits.

The second way scholars consider the state’s role in welfare policy reflects the specific policy tools that lawmakers adopt. Lowi (Reference Lowi1972) articulates a typology whereby policies are differentiated based on their distribution of benefits and costs. This framework defines welfare policies as redistributive in nature. Redistributive programs, which involve the reallocation of resources from one group to another, are considered fundamentally different from distributive and regulatory policies that each have their own distinct power arrangement. In this scheme, a welfare policy is not defined by its goal but by its allocation of political and economic costs and benefits. The idea that welfare policies are those explicitly tied to redistribution remains a common assumption in the current literature on welfare states; it is difficult to find a scholarly account of welfare policy that would not fit within Lowi’s redistributive category. The consequence of this framework suggests that the state is only engaging in welfare policymaking when it creates redistributive programs.

Policy Beneficiaries and Burdenficiaries

The final feature scholars are attentive to when defining welfare policy is the question of benefits and burdens. Scholars have long acknowledged that some welfare policies are more universal in nature, providing assistance across the socioeconomic spectrum, while others are means-tested, intended to cover only a specific group deemed to be in need of assistance. Distinguishing between universal and targeted welfare policies has proven important because each generates different effects on inequality (e.g., Kenworthy Reference Kenworthy2011; Korpi and Palme Reference Korpi and Palme1998; Mettler Reference Mettler2011; Faricy Reference Faricy2015) as well as public buy-in for welfare programs (e.g., Esping-Anderson Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992). Beyond the specific tradeoff between universal and targeted policies, scholars have also demonstrated how welfare policies of both types can be stratified, disadvantaging the most vulnerable groups within an eligible population (e.g., Orloff and Skocpol Reference Orloff and Skocpol1984; Mink Reference Mink1995; Quadagno Reference Quadagno1994; Lieberman Reference Lieberman1998; Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011; Fox Reference Fox2012).

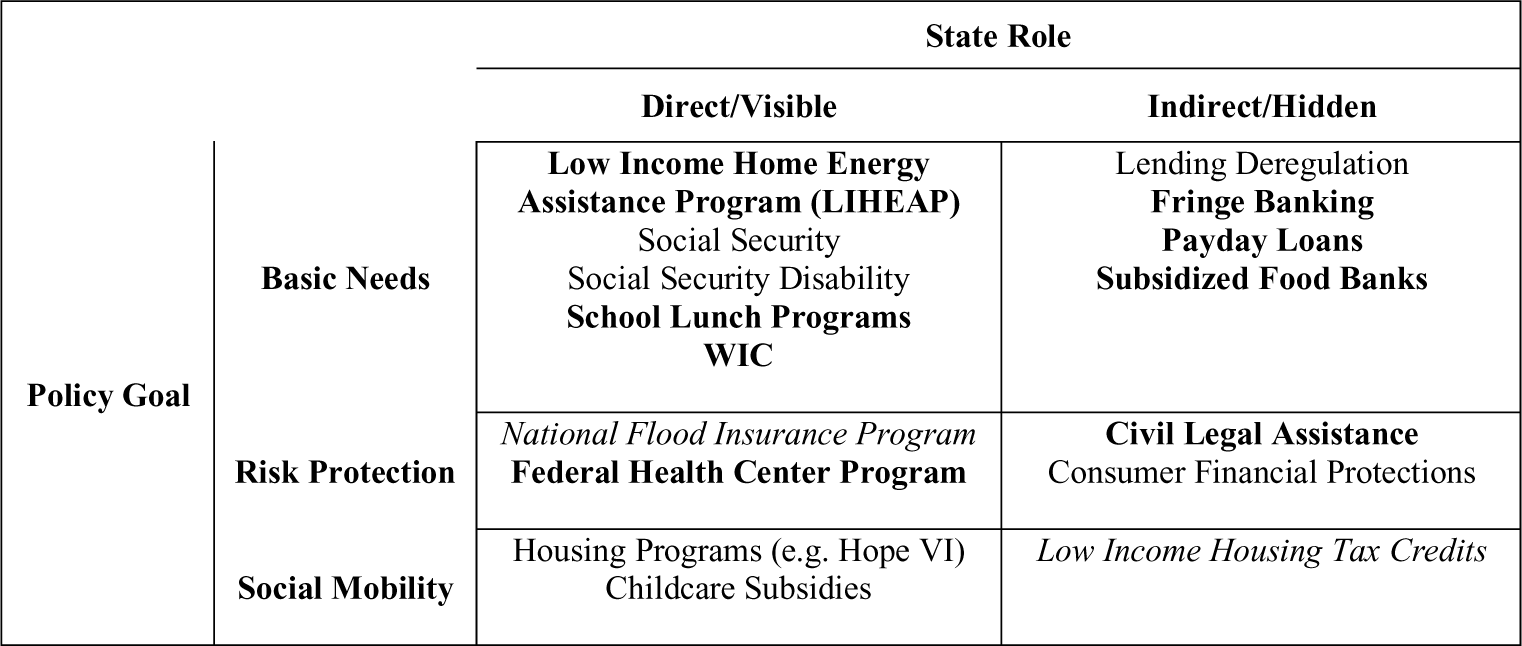

These three dimensions—policy goals, state role, and beneficiaries—overlap to produce an array of potential welfare policies. A full understanding of the U.S. welfare state ought to account for each of these dimensions. Figure 1 illustrates this multi-dimensional view of the U.S. welfare state, laying out how some of the welfare policies that are most commonly studied within the discipline of political science fit into that typology.Footnote 6 It is not intended to be an exhaustive list of all federal welfare policies; rather it captures some of the most frequent targets of (top-down) political science inquiry on the U.S. welfare state.

Figure 1 The multi-dimensional U.S. welfare state: Current scholarship

Note: Bold policies are downwardly redistributive; italicized policies are upwardly redistributive

When we arrange social welfare programs that are frequent targets of scholarly inquiry along these dimensions, the picture of the U.S. welfare state that emerges reflects specific trends. They are exclusively redistributive programs, and they represent the kinds of benefits that we expect a robust (European-style) welfare state to provide. Benefits that redistribute down versus those that provide benefits to better-resourced groups occupy different spaces in this framework. For example, most programs that affect lower-resourced households are direct, with a more visible role for government, while upwardly redistributive programs are more frequently privatized, or submerged. We argue that this picture is incomplete; it does not adequately incorporate the experiences of a comprehensive range of people. Most importantly, this view obscures crucial policies and related sites of implementation and political contestation that denizens of the U.S. state encounter when they attempt to secure and improve their socioeconomic circumstances.

Reimagining the Margins of the U.S. Welfare State

What if we were to reimagine welfare policies from the vantage point of people’s life experiences? What programs might we encounter when we look from the perspective of a specific individual who is seeking assistance to navigate, as President Roosevelt suggested, the inevitable “hazards and vicissitudes of life”? What policies, for example, exist to help someone secure a safe place to live, food on the table, and a way to get to work? What assistance could she secure in the event of an unexpected medical emergency, the loss of a job, the death of a family member, or the onset of a recession? What resources would be available to her to help her improve her situation—to become more educated, to get a better job, to afford a better home? What state institutions might she have to navigate to gain and protect access to such resources? What burdens would she face in doing so? How might the answers to these questions differ for a single mother versus a two-income family, or a schoolteacher versus a CEO?

Undoubtedly, figure 1 accounts for many programs that we would encounter while considering the welfare state through the eyes of a beneficiary, even one on the socioeconomic margins. But there are also striking absences. Figure 2 presents another layer of programs we might add to our original accounting if we asked these questions through a bottom-up lens—that is to say, if we considered what programs a person might encounter in their daily lives while trying to meet basic needs, secure against risk, and improve their circumstances.Footnote 7 Each policy ostensibly links to one of the three welfare goals articulated by existing welfare scholarship. The state has a role in each, either by providing benefits—directly or indirectly—to citizens, by delegating that authority to private actors (who both provide benefits and impose burdens), or by (de)regulating private support.

Figure 2 A bottom-up view of the multi-dimensional U.S. welfare state

Note: Bold policies are downwardly redistributive; italicized policies are upwardly redistributive

Notably, some key differences emerge between the policies in figure 2 and those in the more traditional, top-down framework presented in figure 1. While many of the programs in figure 2 fall under the visible spectrum of welfare support, the state’s role, from the perspective of ordinary folks, is less visible in many of those included when we consider a bottom-up view. In the top-down approach to welfare policy, most means-tested programs appear to be visible to beneficiaries, but a bottom-up analysis brings to light a greater number of hidden programs that assist low-income Americans. The programs in the traditional account (figure 1) are almost exclusively redistributive in nature, while several of the programs that emerge from our bottom-up approach (figure 2) include regulatory efforts. Other policies—like Social Security Disability—appear in both accounts, but the programmatic goal might look different—meeting basic needs versus ensuring against risk—if we consider how marginalized beneficiaries use the policy relative to their more affluent peers. Indeed, when considering welfare from the bottom up we more easily see how different policies are necessary for different people to achieve each of the three goals. Taking this approach also highlights welfare programs that are far more predatory in nature, for example, fringe banking and subprime mortgage programs (Baradaran Reference Baradaran2015; Taylor Reference Taylor2019).

While the list of policies in figures 1 and 2 are by no means comprehensive, engaging in this brief thought experiment suggests that a top-down, or traditional, approach to the welfare state overlooks a variety of critical, and in some cases uniquely American, programs. Such a narrow view of the welfare state also prejudices scholars against identifying and understanding key forms of politics and sites of political contestation that folks at the margins grapple with every day.

We propose that political science scholarship on the welfare state should broaden its boundaries to include the programs and sites of state-citizen interaction that are central to many Americans’ experiences of welfare—and thus, of the state. Of course, political scientists have produced valuable work on some of these policies already. For example, a growing literature addresses the political development and consequences of financial regulations and lending programs in housing (Thurston Reference Thurston2018), consumer credit (SoRelle Reference SoRelle2020; Wiedemann Reference Wiedemannforthcoming), and fringe banking (Posey Reference Posey2019). Others explore the politics of emergency relief benefits offered in the aftermath of disaster (e.g., Chen Reference Chen2013). New scholarship also expands our conception of the key sites of welfare policymaking to include frequently overlooked street-level bureaucrats (e.g., Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011; Barnes Reference Barnes2020; Barnes and Henly Reference Barnes and Henly2018; Zacka Reference Zacka2017).

While some of these studies might be considered part of the large corpus of welfare state scholarship, many are not, despite touching fundamentally on issues of public welfare. Still more relevant polices and their corresponding politics are left largely unexplored by political scientists, giving us an incomplete view of the relationship between state and citizen for many of the most marginalized Americans. Moreover, the elements of welfare policy we attune to are inevitably shaped by our orientation toward the welfare state and its targets. By approaching from the bottom up, we will be better equipped to differentiate (theoretically and empirically) between aspects of the welfare state that enact the positive goals delineated here (basic needs, risk protection, social mobility); those that instead enact predatory, punitive, or control oriented goals; and those that do both.

An Experiential View of the State

The theoretical shift we propose requires grounding our perspective in the lives of ordinary people. Our core logic is that the welfare state is better understood by grasping the ways it emerges in the lives of those it purports to protect and support. To instantiate that logic, we highlight two key but often overlooked dimensions of welfare state politics—civil legal assistance and consumer credit—that become visible when we center the bottom-up voices of people navigating the state in essential aspects of their daily lives. In taking this experiential tack, we demonstrate how conceptualizing the welfare state from the bottom up not only illuminates new policies, but also brings to the fore overlooked areas of political contestation and patterns of political engagement among people at the margins. An experiential route also reveals that the ostensibly positive aspects of programs articulated by political elites often fail to materialize benefits and instead impose burdens.

Welfare Politics and Civil Legal Assistance

The civil legal system provides an apt example of how a bottom-up view unearths the ways that ordinary people secure basic needs and navigate risk protection in their daily lives. This system is not incorporated into present conceptualizations of the welfare state, but it is a crucial tool in the lives of those who are most marginalized. The core functions of civil law include things like securing the rights of public assistance beneficiaries, preventing illegal evictions, and litigating matters involving debt and foreclosure. At the crux of civil law is that it “provides a remedy to individuals or entities harmed by other individuals or entities, in order to make them whole” (Klein Reference Klein1999). While criminal law is largely focused on punishment, civil law is nominally focused on protection and compensation (Mann Reference Mann1992).Footnote 8 Most importantly, since civil legal processes often determine who can obtain and retain resources from the state that protect against economic precarity and predation—including those benefits provided by many public welfare programs—a lack of access to civil justice can deepen poverty and reproduce inequality (Houseman and Minoff Reference Housman and Minoff2014; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2008).

Notwithstanding the vital position of civil law in the larger American political economy (over fifteen million civil cases flow through state courts each year), there is little theorization of the linkages between the civil legal system and the welfare state. Taking a bottom-up view of the welfare state—centering the voices of those at the margins—surfaces connections between institutions like the civil courts and more traditional welfare programs. These voices also call into question whether the stated (positive) goals of welfare-promoting policies and institutions are borne out in people’s lives. Consider, for example, a woman named Sora’s experience navigating the civil courts in order to protect her Section 8 benefits:

I got into some legal problems with the last house I was in. They were saying that…they ended their Section 8, that I needed to move out…. When [the landlord] did the eviction, I was by myself. And that judge was very, very nasty, you know? …I mean it left me crying out of the courtroom, you know, and I just cannot believe this just happened. Like I have all the proof of everything, and the judge won’t look at any…. I had over 50 pages and she wouldn’t look at none of my things, but she looked at everything for [the landlord]…. Like nobody was on my side. It’s like they belittle you because you don’t have a certain type of money…. You know, the state is supposed to help you when you’re on [Section 8]…. I’m getting help from the government and I’m feeling even lower because they treat you so low …it’s sad that the this the system works with the landlords instead of the people.Footnote 9

While civil legal institutions cannot be completely subsumed under the umbrella of the welfare state, Sora’s experience highlights how some aspects of the civil legal system clearly reflect foundational prerogatives and explicit programmatic efforts of welfare policy. Foremost is the critical role the civil legal system plays in navigating disputes over public benefits, making it a central institution in the implementation of welfare policy. In fact, problems with income-maintenance programs are one of the top three issues among low-income Americans seeking legal help through the Legal Services Corporation (2017). The civil courts also clearly fulfill (or fail to fulfill) a risk protection function for those like Sora facing eviction or other financial crises like bankruptcy, debt collection, etc.

Another notable connection between the civil courts and the welfare state that Sora’s description highlights is the role the state plays in providing civil legal representation as a means to improve the welfare of low-income Americans. There is no constitutionally guaranteed right to legal counsel in civil cases.Footnote 10 As a result there is a yawning “justice gap”—the difference between the level of legal assistance necessary to meet the needs of low-income Americans and the level of legal assistance actually available to them. Sora’s experience navigating the courts without counsel reflects that of the estimated 50% to 80% of people living in poverty in the United States who have difficulty obtaining civil legal representation (Rhode Reference Rhode2004; Chu, Greenfield, and Zuckerman Reference Chu, Greenfield and Zuckerman2013). Her story demonstrates how the absence of counsel to support marginalized claimants largely removes the expectation for protection or compensation from the courts.

In an effort to address this justice gap, policymakers first enacted a program of federally funded civil legal assistance for the poor as part of the War on Poverty, which eventually lead to the 1974 creation of the Legal Services Corporation. Their rhetoric suggests that such assistance was compatible with the goals of the welfare state, acknowledging that “providing legal assistance to those who face an economic barrier to adequate legal counsel will serve best the ends of justice and assist in improving opportunities for low-income persons” (Public Law 93-355). And the broader politics of welfare state expansion and retrenchment have since been tightly linked with providing low-income civil legal aid. Many proponents hoped to leverage civil legal assistance to low-income Americans as a tool to engage in welfare policy reform through the civil courts. Worried over early successes with this approach, opponents then sought to limit access to civil legal assistance as a means to curtail the welfare state. As a result of this tug of war, for every person who receives publicly funded legal assistance, another applicant is turned away because of insufficient capacity (Legal Services Corporation 2009).

The consequences of such inadequacies are not borne equally across groups. Just as men of color disproportionately experience the winnowing of their citizenship through the criminal justice system, women of color (and low-income women more generally) experience a similar winnowing of citizenship via the civil justice system. Once again, Sora’s experience clarifies in stark detail what the presence or absence of publicly funded legal assistance can mean in the lives of people struggling to navigate civil courts to secure access to the programs that are intended to help them provide for their welfare:

She’s like you need to call Legal Aid and I … never really dealt with Legal Aid before… . I had to answer for the eviction, and we ended up going to court … [Legal Aid] was busy when I called to make an appointment and they said we just don’t have an attorney to go with you. And the first time should have been when I really needed [Legal Aid] because everybody who read the judgment say this doesn’t sound right… . [The second time with Legal Aid] it was fine because the attorney knew exactly … it worked out perfect for me… . It was just, you know, that part went so smoothly.

Some local governments have begun to adopt policies providing civil legal representation in a welfare state-esque form. In 2017, New York City passed Intro bill 214-B, which guarantees legal representation for all tenants in housing court who fall at or below 200% of the poverty line. In 2018, San Francisco followed suit, but shed the means testing and pledged to provide representation for all tenants facing eviction. These and other cities are embracing a more capacious vision of the government’s role in the contemporary welfare state that includes civil legal representation as a resource that the state is responsible for providing—a trend that has accelerated amidst the economic damages wrought by COVID-19.

Importantly, such expansions have been driven by grassroots political action on the part of economically and racially marginalized communities (Michener Reference Michener2019a). This remarkable process of policy diffusion might be overlooked by top-down accounts of the welfare state, but it becomes visible through bottom-up scholarship. Ronald, a low-income resident of New York City, is a fitting example. He became a community leader in the fight to pass Intro Bill 214-B only after his own harrowing ordeal of nearly being evicted as a single father of five children. After being served his eviction papers, he noted:

I stood in that hallway of my apartment and tried to figure out where I’m going to put my stuff, where I’m going—what am I going to throw away? You understand that? Where am I going to go live? When I looked into my kids, their eyes, seen how frightened they were, you understand then how scared they were…the stress? And I don’t know if I faked it good enough, being strong, but I was just as scared and fearful as they were. So I said to myself [I want] to make sure tenants have lawyers, that this is the fight, something that I wanted to participate in because no family should ever go through what I went through for no reason. For no reason.Footnote 11

Shortly thereafter, Ronald found a community organization to work with, and years later, he remains involved in community organizing around housing rights. At present, most scholars of the welfare state barely recognize civil legal representation as germane. But it is not just that civil legal policy represents a domain that is left out of current discussions. Even more crucial is that scholars have not developed the capacity for explaining the significance of the bottom-up politics that bring people like Ronald into the political process. Though sociologists have offered critical work highlighting civil legal problems and the social processes underlying them (Desmond Reference Desmond2016; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2008), political scientists have paid much less attention to the political institutions involved (local housing courts, legal aid organizations, civil legal policies, etc.) and their political consequences (Michener Reference Michener2020).

Credit and the Welfare State

A top-down approach has also helped to obscure the ways in which ordinary people rely on government-supported and regulated credit to accomplish welfare-oriented goals including obtaining basic needs, risk protection, and investment for social mobility, leading to an incomplete understanding of the politics of credit. To the extent that credit programs have been theorized as a part of the American welfare state, they have generally been treated as part of the hidden or submerged state, with a focus on middle-class subsidies pertaining to the government’s promotion of homeownership (whether through the Federal Housing Administration or Government-Sponsored Enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, or implicitly through the home mortgage interest deduction) and education (through federal loan guarantees). Political scientists have found that these policy areas are largely out of the view of ordinary citizens, including their beneficiaries, making these issues less salient to the public while empowering business and other private interests (Howard Reference Howard1997, Reference Howard2007; Mettler Reference Mettler2011, Reference Mettler2014).

By contrast, a bottom-up approach presents a very different picture in terms of policy, policy effects, and political effects, as we render by drawing from extant historical and ethnographic work. Descriptively, a bottom-up approach reveals, first, that citizens rely on many different forms of credit in order to secure welfare goals. While these include the mortgage and student loan programs noted earlier, they also include financial products and services that are heavily influenced by government policy and regulation (or the lack thereof), including credit cards, and fringe banking services including check cashing and payday loans (e.g., Servon Reference Servon2017; Wiedemann Reference Wiedemannforthcoming; SoRelle Reference SoRelle2020; Posey Reference Posey2019).

In addition, a bottom-up approach draws attention to the considerable variation not only in the supply of policies and patterns of access and availability, but also on the demand. This includes the choices people make about why to use one form of credit over another or what they purchase on credit. For example, while working in the field at a payday lender, Servon (Reference Servon2017, 79) received a first-hand education from her co-worker, Ariane, about the role payday lending played in helping people meet basic needs:

Ariane told me that five months earlier, her car broke down. A young single mother, she took the bus for a few weeks, but her changing work hours made it impossible to take her child to daycare and then get her work on time… Ultimately she decided she had to repair her car or risk losing her job.

Sociologists have similarly examined individuals’ decisions to enroll in for-profit higher education programs despite their higher debt loads and worse outcomes. Holland and DeLuca find that young people in disadvantaged neighborhoods gravitate towards riskier two-year degree programs because their neighborhood context makes fast credentials linked to concrete job descriptions particularly appealing (“Why wait years to become something?” asks one of the interview subjects, a line that becomes the title to their article; Holland and DeLuca Reference DeLuca, Clampet-Lundquist and Edin2016, 261). McMillan-Cottom (Reference McMillan-Cottom2016) finds, likewise, that one reason for-profit institutions appeal to marginalized communities is that they do a better job than traditional colleges of accommodating their students’ life situations.

Relatedly, a bottom-up approach illuminates differences in outcomes from using credit programs. Taylor (Reference Taylor2019) explores how the new availability of federal mortgages for low income households and residents of previously redlined urban neighborhoods constituted a system of predatory inclusion:

In Philadelphia in 1970, an African American mother celebrated her move out of a public housing project into a “brand-new” home of her own. She, like millions of parents across the country in the postwar period, invested in homeownership and the American dream with the expectation of raising her children in a good neighborhood and sending them to a better school than the ones she had attended in her youth.

(Taylor Reference Taylor2019, 133)The similarity ended there. Instead of finding herself “in one of the sprawling bucolic spaces of suburbia, where most of the postwar housing boom had taken place”, the woman was one of thousands of borrowers who had found themselves underwater in overpriced but low quality housing pushed by real estate speculators, across the country:

In Berkeley and Oakland, California, an investigation found that dilapidated homes were sold to low-income families for three and four times more than they were worth. The houses were ‘largely incapable of passing honest FHA inspection and certainly failed to meet minimum FHA standards.’

(Taylor Reference Taylor2019, 134)As Taylor shows, the long fight for inclusion in homeownership was marked by an inversion of mortgage policies’ welfare function, from asset building, towards equity stripping.

While these examples broaden our description of the welfare state, they also have implications for political analysis. The first implication is that people’s political attitudes and behavior may be a reflection of how they are treated by these systems. Posey (Reference Posey2019) provides the most compelling account of this in examining the “paradoxical” ways that citizens react politically when their neighborhoods are cut off from mainstream sources of finance. Moreover, and challenging the idea of a submerged state, the absence of “good” government credit programs is at times highly visible to those most affected and articulated in terms that clearly speak to the role of policy and government, as seen in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s early detection of concrete rules for housing discrimination in the Federal Housing Administration in the 1930s (Thurston Reference Thurston2018), as well as (much more recently) the Movement for Black Lives’ explicit mention of both the legacy of housing discrimination and the positive need for new tax incentives and government loan programs to encourage economic development in Black communities in its platforms.Footnote 12

Finally, studies of credit from the bottom up can draw attention to alternative venues of politics, refocusing attention onto the role of state and local governments in regulating key aspects of the credit relationship and attendant politics at these levels; the discretion of lower-level political actors, including bankruptcy judges, in extending or restricting quasi-welfare state protections to citizens (Dickerson Reference Dickerson2012); and the less visible ways that social movement organizations have worked to alter the status quo (Thurston Reference Thurston2018).

Implementing a Bottom-Up Approach

In 2001, the American Political Science Association launched a task force to “review and assess the best current scholarship about the health and functioning of U.S. democracy in a time of rising inequality” (APSA Task Force on Inequality and American Democracy 2004, 1). In the edited volume emerging from that venture, Lawrence Jacobs and Theda Skocpol urged that “expanding research on society-government links thus requires changes in scholarly behavior… . What we need, in short, is a new generation of research devoted to critical studies of democratic life that reexamine what we study and how we do it” (Reference Jacobs and Skocpol2005, 231). Our proposal to reorient welfare state scholarship by grounding the research agenda in a bottom-up approach is consistent with this mission.

Jacobs and Skocpol note of the existing political science corpus that “what government does—or does not do—is obviously at the center of research on both government responsiveness and public policymaking” (Reference Jacobs and Skocpol2005, 224). The current welfare state literature embodies this logic; how we define the welfare state—and thus what we explore about its politics—emanates from the state itself. Here, we present a (complementary) alternative. We argue that in order to get a comprehensive understanding of the welfare state; its politics; and the inequalities it either produces, reproduces, or mitigates, scholars must develop and test theories of the welfare state that are cognizant of the lived experiences of its most marginalized beneficiaries.

To accomplish this, we have suggested changes in where political scientists look in their efforts to delineate the welfare state, shifting the targets of analysis from elites and elite-produced categories to the experiences, actions, and stated rationales of those who use and interact with it (Barnes and Henly Reference Barnes and Henly2018; Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal2020; Posey Reference Posey2019), or towards the organizations, political actors, and institutional structures that may help citizens make sense of their situations (Michener Reference Michener2019a; Thurston Reference Thurston2018; Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017). A bottom-up agenda also suggests changes in how political scientists go about studying the politics of the welfare state, whether by more use of ethnographic and interview methods to observe everyday processes (Michener Reference Michener2018, Reference Michener2019a; Campbell Reference Campbell2014), to reorienting historical/archival, survey, and experimental approaches towards these goals (see, for example, Kohler-Hausmann Reference Kohler-Hausmann2017; Barnes and Henly Reference Barnes and Henly2018; Thurston Reference Thurston2018; Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal2020).Footnote 13 Relatedly, political scientists might develop novel ways of observing citizens as they navigate state and local policies to secure the things they need to meet their basic needs, protect against risk, and secure new opportunities. Here, we draw inspiration from the Portals project, a recently developed platform for bringing together citizens in different locations to converse. Unmediated by an interviewer, participants nevertheless articulated their relationships to state institutions and theories of democracy grounded in those experiences (Weaver, Prowse, and Piston Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2019; Prowse, Weaver, and Meares Reference Prowse, Weaver and Meares2019).

These changes could be leveraged to help political scientists better do what they already do well. Political scientists need not replicate the high-quality work done in other fields that have centered marginalized groups (Edin and Shaefer Reference Edin and Shaefer2015; Seefeldt Reference Seefeldt2016; Desmond Reference Desmond2016; Halpern-Meekin et al. Reference Halpern-Meekin, Edin, Tach and Sykes2015; Wherry, Seefeldt, and Alvarez Reference Wherry, Seefeldt and Alvarez2019). Instead, our comparative advantage lies in explicating the political conditions underlying and generated by the economic and sociological realities facing marginalized groups. Doing so requires that we “recognize the special vantage point … marginality gives us” (hooks Reference hooks1984, 16) and draw on it to better understand oft overlooked policy terrain, historical and emergent areas of political contestation and engagement, and the manifold structures that shape marginalized groups’ political attitudes, beliefs, and action. Altogether, such a reorientation is part and parcel of understanding the problems and possibilities of American democracy.

Throughout this article, we have delineated ways that the “special vantage point” of marginality can enrich the study of the welfare state. Yet discerning that vantage point poses significant challenges and requires change in the scholarly status quo. Such changes include incorporating the voices and experiences of hard-to-reach populations (whether from the archives, from public comment data, from interviews and surveys, or other creative data collection methods); collecting (and valuing) descriptive research that tells us things we do not know about people’s lives; shifting our lenses so that scholarship focused on marginalized groups is not depicted as narrow or atheoretical; and then aligning incentives and rewards to reflect all of these changes. Such disciplinary transformations are no small feat—they require commitment of priorities and resources from individual scholars, academic departments, journal editors, funders, and professional associations. Yet a collective effort towards enacting them would allow for stronger statements about the role of government in citizens’ lives and the varying ways that American democracy responds, or fails to respond, to their demands.