While conflicting worldviews are of the essence of democracy, an “us versus them” logic in politics can endanger democracy. Indeed, in the electoral arena, if supporters of a losing candidate perceive the winner as a threat, they may be less willing to accept the results of the election. Since Iyengar et al. (Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012)’s seminal article, the democratic risks of affective polarization are a matter of increasing concern in the USA. An influential strand of the literature argues that affective polarization arises from strong social identities built around political parties, which may be as strong as religious identities and often lead to a division of the world into an ingroup and an outgroup (e.g., Green et al., Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002). It is easy to see how such social identities could emerge in a bipartisan country with strong—or even radical—forms of partisanship, such as the USA (e.g., Kalmoe and Mason, Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022). But can the “us versus them” logic in politics undermine support for democracy even in contexts where parties are multiple and weak? Our evidence from Chile shows that affective polarization is a pervasive phenomenon, despite low party identification, and our experimental results reveal that it can erode democratic support. This underscores the need to examine “us versus them” politics beyond partisanship.

Graham and Svolik (Reference Graham and Svolik2020) show that the U.S. public’s viability as a democratic check decreases with various measures of polarization, including the strength of partisanship, policy extremism, and candidate platform divergence. These findings do not point to affectively polarized citizens preferring undemocratic candidates per se, rather than being willing to sacrifice democratic principles for proximity to their party (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Green and Iyengar2023). Likewise, Simonovits et al. (Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022) conclude that extended “democratic hypocrisy”—the tendency to support democratic norm-eroding policies only when one’s own party is in power—is further amplified in the USA according to two indicators of polarization: strong expressive partisanship and the perceived threat from the opposing party (also see Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021). To the extent that the public plays a role in sustaining democracy (e.g., Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Ajzenman, Aksoy, Fiszbein and Molina2024), this evidence suggests polarization erodes democracy.Footnote 1

However, we know little about how affective polarization influences democratic attitudes in Latin America, a region that has exhibited the greatest increase in polarization in recent decades, according to Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) scores (UNDP, 2023; also see Segovia, Reference Segovia2022). The region poses a measurement challenge given its multiparty systems, although there are approaches to deal with this (e.g., Wagner, Reference Wagner2021; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023). Yet, the weakness of political parties in Latin America can be more challenging to our traditional understanding of polarization based on party identification. In Chile—where identification with parties, and even coalitions, is extremely low (LAPOP 2018)Footnote 2—it is unclear that parties or even coalitions are the main dividing line in politics.Footnote 3 Still, the absence of party identification does not rule out animosity between political camps, which may travel through other political divides that separate citizens into opposing camps. For instance, affective polarization can be based on opinion groups, as has been found for Brexit (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021) or secessionist conflicts, like in Catalonia (Balcells and Kuo, Reference Balcells and Kuo2023).

We study the case of Chile’s September 4, 2022 plebiscite, when voters had to approve (Apruebo) or reject (Rechazo) a new constitution drafted by a Constitutional Convention. Trust in parties and party identification were at minimum, and there were various salient issues, some cross-cutting traditional party divides or generating intra-party division, thus blurring “party positions” associated with the plebiscite vote. We conducted an experiment embedded in an online survey 2 weeks before the plebiscite. The experiment induced (short-lived) affective polarization using an unobtrusive primer (based on Simonovits et al., Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022) on randomly selected respondents, which proved effective in increasing animosity along multiple dimensions that produce an “us vs. them” logic. We find that individuals who were primed to be more affectively polarized strongly decreased their support for democracy, in line with prior research for the USA. However, we emphasize that, unlike in other studies, this effect represents a direct erosion of democratic ideals rather than a compromise of democratic principles for ideological proximity. This result highlights the importance of studying polarization, particularly in the current global context of democratic backsliding and in regions where democracy has been vulnerable in the past.

1. Context

Starting on October 18, 2019, Chile experienced a severe social outburst. It started over an increase in subway fares and evolved into violence, massive protests, and a deep political crisis.Footnote 4 On November 15, parties from the entire political spectrum (except the Communist Party) signed an agreement that opened the way for a new constitution. The entry plebiscite was approved with 78% of the vote in October 2020 and a Constitutional Convention was elected in April 2021, with a record share of members from the left, anti-system, and independents.

The first presidential election after the 2019 protests was held in November 2021. For the first time since the return of democracy in Chile in 1990, neither runoff candidate belonged to the two main coalitions that dominated the country’s politics for three decades. Gabriel Boric, a founder of the young left-wing Frente Amplio coalition, unexpectedly won a primary of voters from his coalition and the Communist Party, and traditional center-left parties backed him in the runoff. The other runoff candidate, José Antonio Kast, had founded the far-right Republican Party in 2019, and more than doubled the traditional right’s candidate. The runoff, held under voluntary voting, had a record turnout of 56% and Boric won with 56% of the vote.

The binary organization of Chilean politics around two coalitions that had prevailed since 1990 had given place to an increasingly complex scenario, and around 20 parties won seats in the concurrent parliamentary election. Despite this greater diversity, at the time of our study (CEPFootnote 5 2022) only 24% of the population identified with a political party, a dramatic decline from around 70% in the early 1990s (CEP 1994). A slightly higher share identified with a political coalition (30%) in 2017, the last time CEP asked this question (CEP 2017). According to Meléndez and Rovira (Reference Meléndez and Rovira2019)’s analysis of attachments to and rejections of the two traditional coalitions in Chile, negative partisanship was stronger than positive partisanship: people identified more against a coalition than in favor of one. Identification on the left–right ideological spectrum has, to some extent, provided more solid and stable political identities, rooted in the experience of the 1973–1990 dictatorship, as shown by Argote and Visconti (Reference Argote and Visconti2024). Yet, nearly a third of Chileans (31%) do not position themselves on the left–right axis (CEP 2022), and, as argued by de la Cerda (Reference de la Cerda2022), the cleavage based on the dictatorship has faded over time.Footnote 6 Neither is Chilean politics organized around religious or family lines, or a specific political figure, as occurs elsewhere. And while there are multiple contested policy issues, it is hard to pick one or two as the main dividing lines. Thus, when thinking of affective polarization in Chile, it is not even clear how the ingroup/outgroup should be defined. Moreover, Meléndez and Rovira (Reference Meléndez and Rovira2019) found that the most prevalent group, as defined by negative and positive partisanship, was “apartisans,” that is, people who do not hold positive nor negative partisanship and are rather politically disengaged.

The constitutional discussion involved a wide range of issues, from the rights of nature, collective rights for indigenous peoples, reproductive rights, and gender diversity, to the role of government, labor rights, and private property. The Constitutional Convention gradually lost support, and most polls conducted since April 2022 indicate majority support for rejecting the draft constitution. Voting was mandatory for the September 4, 2022 plebiscite, and 86% turned out; the Reject option won with 62% of the vote.Footnote 7

Given the high level of contestation of the plebiscite, our treatment exploits variation along the divide produced by this election. As manipulation checks, we also include different measures of affective polarization since we are agnostic about which political division is most relevant in Chile: along the lines of the two last elections (the plebiscite and presidential runoff) and along the traditional left–right divide. In all cases, we ask respondents to evaluate groups of people who voted for or support a certain stance.

2. Research design, implementation, and estimationFootnote 8

In our survey experiment, we activated affective polarization with an open-ended unobtrusive primer based on Simonovits et al. (Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022). They asked respondents to “List a few things that make you feel threatened about the Democrats/Republicans” and thus activated respondents’ animosity toward the outgroup by relying on their own views about what their animosity is based on. We first asked respondents how they planned to vote in the upcoming plebiscite; the primer for individuals assigned to treatment read:

Thinking of [outgroup]Footnote 9 voters, please list a few things you dislike about them. Please note that we are not asking you about the constitutional proposal, but about the people who vote for the proposal. We are very interested in your views on this. Please take at least thirty seconds to answer this question without rushing.

The control group received a placebo question (about promotional phone calls)Footnote 10 to avoid inducing different levels of fatigue and negative thoughts between the groups. We pretested the treatment and placebo and established that respondents understood them and did not feel uncomfortable. After the treatment (or placebo), we measured affective polarization in different ways as a manipulation check and then measured support for democracy.

The survey was conducted by Netquest, an experienced online polling firm with a presence in over 20 countries, and was programmed in Qualtrics. We conducted it 2 weeks before the election. To ensure we had a sufficient sample size for every relevant demographic group, we requested specific quotas based on socioeconomic groups, geographic areas, gender, and age group. Supplementary Appendix Table B.1 shows population vs. sample distribution of demographics, suggesting an underrepresentation of the least educated and younger groups. Still, our treatment effects are not statistically different by these groups (Supplementary Appendix Table B.4), reducing the chances of a composition bias.

Following a standard approach to measuring affective polarization at the individual level, we use respondents’ feeling ratings toward groups of people. We take advantage of the plebiscite’s binary setting to construct two opposing political groups. Respondents were asked to rate groups of people on a scale from 0 (very negative) to 10 (very positive). We included questions on Approve and Reject voters, on voters in the recent presidential runoff (Boric and Kast), as well as people from the left and right (Supplementary Appendix Table B.2 lists the full question wordings). We randomized the order of appearance of these pairs, as well as the order of each group within each pair. We calculate affective polarization as the distance between the ratings of groups within each pair (e.g., Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012). This gives us three measures of affective polarization based on voters in the plebiscite (“plebiscite voters”), voters in the presidential election (“presidential voters”), and political position (“left–right”). Among respondents who had a vote choice, the levels of affective polarization for the two electoral dimensions are of the same order of magnitude as those found for Democrats vs. Republicans among partisans in the USA (56 for Democrats and 63 for Republicans, on a 0–100 scale; ANES 2020); those for left-right are much lower (∼30). Finally, we included two additional affective polarization outcomes along the plebiscite divide, based on Kalmoe and Mason (Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022): whether the outgroup voters are “a threat to Chile and its people” and if they are “downright evil.” We further put together the different measures in an Affective Polarization Index based on Kling et al. (Reference Kling, Liebman and Katz2007). In turn, our outcome of interest is support for “democracy as the best system of government” on a 0–10 scale.

To estimate the effects of receiving the open-ended priming question intended to activate animosity toward outgroup voters on support for democracy, we use ordinary least squares (OLS) reduced-form estimates with different strategies for covariate adjustment.Footnote 11 The estimated treatment effects correspond to intent-to-treat. Our dependent variable is standardized, and the errors are robust. We posit that our priming treatment should affect support for democracy outcomes only or mostly through affective polarization.

3. Results

Our treatment elicits individual affective polarization along the plebiscite divide, which allows us to causally identify its effects in an unobtrusive way. The treatment asked respondents to list at least three things they dislike about outgroup voters. Almost all treated respondents engaged with the promptFootnote 12 and on average spent more time on the question than the required minimum 30 seconds: the average was 121 seconds for the treatment and 107 for the placebo. The average number of words for the treatment was 16 and 15 for the placebo. In Supplementary Appendix C, we present the manipulation checks. The open-ended priming question effectively increased the Affective Polarization Index among the 85% of the sample who had a vote choice, with a statistically significant effect (Supplementary Table C.1). We thus zoom in on the results for this group, distinguishing by Approve and Reject voters.Footnote 13 The answers to an open-ended question about feelings toward the outgroup, asked at the end of the survey, also suggest that the treatment activated animosity toward outgroup voters among those with a vote choice (Supplementary Figure C.1).

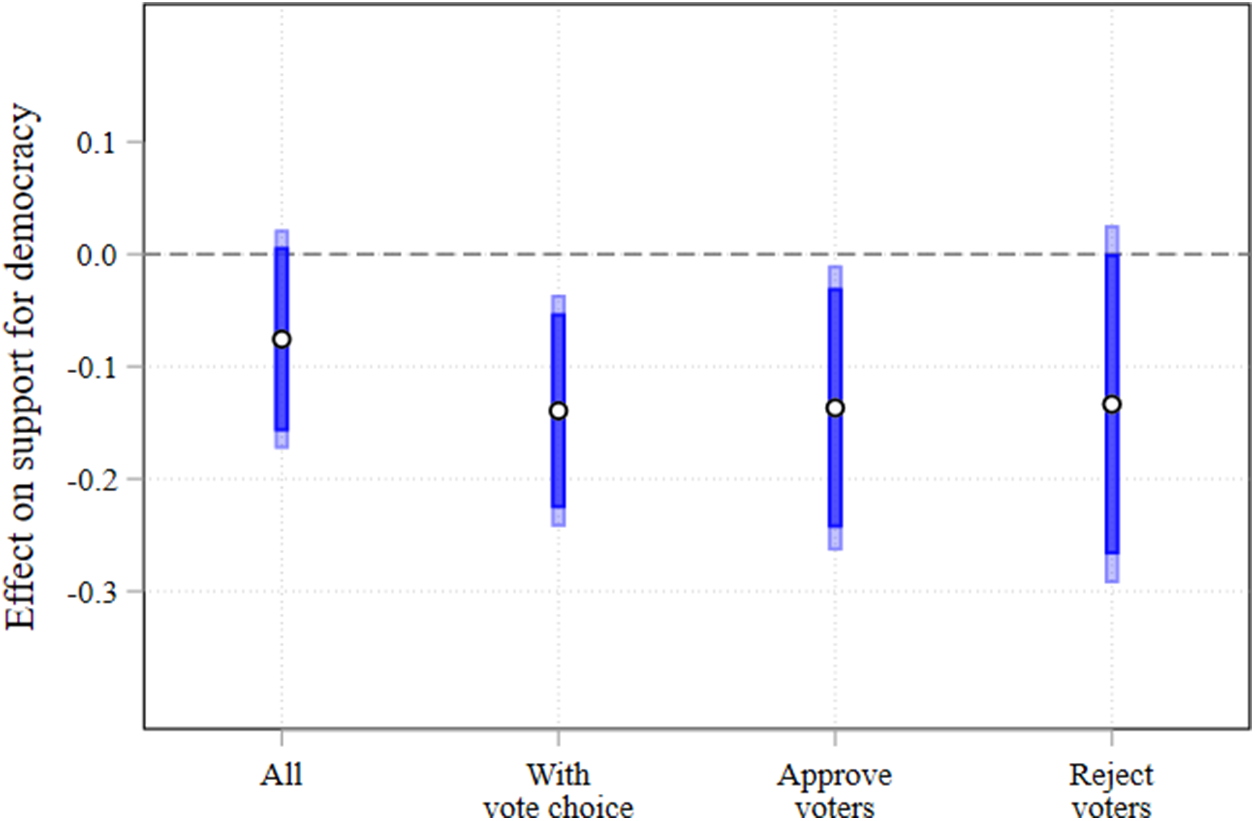

Now, how does affective polarization shape democratic commitment? Figure 1 presents the results of the priming experiment for support for “democracy as the best system of government” for the full sample, those with a vote choice, and Approve and Reject voters (see Supplementary Appendix Table B.3, Panel B). Although the results are not statistically significant for respondents at large, we consistently identify a negative treatment effect among subgroups with a clear voting choice. Among the 85% of the sample with a vote choice in the plebiscite, the treatment reduces support for democracy by 0.12–0.14 standard deviations, significant at the 95% level, which is a substantively relevant effect that is very robust across estimation strategies. Thus, we causally show that abstract democratic convictions are undermined simply when individuals become more affectively polarized, in line with previous research.

Figure 1. Treatment effect on support for democracy, by group.

4. Discussion and conclusion

We broaden the comparative lens and study a context of low party identification: the 2022 constitutional plebiscite in Chile, a high-stakes binary election with multiple issues at play. Our experiment provides strong causal evidence that affective polarization undermines citizens’ commitment to democracy. Notably, we find erosion in abstract democratic norms; not only a preference for undemocratic candidates when they are the only option that shares the respondent’s ideological position. Contrary to the studies reviewed by Druckman et al. (Reference Druckman, Green and Iyengar2023), our study shows a direct impact on democratic support, not a choice in a difficult trade-off.

Recent research by Broockman et al. (Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2022) and Voelkel et al. (Reference Voelkel, Chu, Stagnaro, Mernyk, Redekopp, Pink, Druckman, Rand and Willer2022) establishes that decreasing affective polarization does not enhance citizens’ commitment to democracy. Our findings, together with those of Graham and Svolik (Reference Graham and Svolik2020) and Simonovits et al. (Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022), among others, indicate that affective polarization does erode citizens’ commitment to democracy. Overall, this evidence may suggest that affective polarization has an asymmetric effect, in line with loss aversion theory (e.g., Kahneman and Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979): greater affective polarization may harm democratic commitment, without a commensurate improvement for reducing it. Future research should study this asymmetry further, especially because it highlights the difficulties of rebuilding institutional trust and sustaining democracy.

Our study is one of the first to address the causal relationship between “us vs. them” politics and democratic erosion in Latin America. Future research should assess the external validity of this finding, especially considering that our treatment exploited a very particular political divide. Yet, we show that even a salient but recent divide, in a context of weak partisan identities, can produce high levels of affective polarization, to a point that can be harmful for democratic commitment. Thus, political identities may lack an institutional, long-standing ground, as in the USA, and are still capable of generating strong group belonging dynamics. In the lines of Argote and Visconti (Reference Argote and Visconti2024), perhaps the divide produced by the plebiscite had some common roots with older ideological cleavages (the correlation between affective polarization based on the plebiscite and ideology is 0.40, according to CEP 2022).Footnote 14 Yet, the plebiscite is far more polarizing than ideology (see footnote 6), suggesting that “us vs. them” politics does not require historical, deeply socialized political identities.

Recent research has found that support for democracy matters for political stability (Claassen, Reference Claassen2020; Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Ajzenman, Aksoy, Fiszbein and Molina2024); thus, our negative effects of affective polarization on support for democracy should be of concern, especially for a region with poor democratic records and indications of a rise in authoritarianism.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.10019. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EA4TCN.

Acknowledgements

We thank the outstanding research assistance of Paula Araya, Angelo Bernales, and Hernán Carvajal. We also thank Damian Clarke, Natalia Garbiras-Díaz, Javier Nuñez, two anonymous reviewers, and seminar participants at PolMeth, APSA, Escuela de Gobierno UC, LAPolMeth, and the Economics Alumni Workshop UC for helpful comments. This research was funded by Proyectos Fondecyt Iniciacion 11201279 and 11251113 and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Centro de Estudios Públicos on August 12, 2022 (protocol 8.12.2022). A pre-analysis for this study was registered with EGAP, ID: 20220425AD (https://osf.io/jympr; see the PDF file for the second survey). All errors are our own. Data and replication material are available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/EA4TCN.