Although an extensive body of research showcases the efficacy of authoritarian propaganda and censorship in manipulating the information environment and influencing public opinion during “normal” times (Huang, Reference Huang2015; Wedeen, Reference Wedeen2015; Mattingly and Yao, Reference Mattingly and Yao2022; Pan et al., Reference Pan, Shao and Yiqing2022; Carter and Carter, Reference Carter and Carter2023; Mattingly et al., Reference Mattingly, Incerti, Changwook, Moreshead, Tanaka and Yamagishi2024; Yang, Reference Yangforthcoming), limited attention has been given to whether the effects hold during political crises and policy changes (except, e.g., Bleck and Michelitch, Reference Bleck and Michelitch2017). This gap in the literature is particularly important because, during crises, citizens have greater incentives to critically scrutinize propaganda, and theoretical models suggest that propaganda is less effective in such contexts (Horz, Reference Horz2021). Consequently, the lack of studies conducted during crucial moments can lead to a “positive bias” in the propaganda literature. This study fills this gap by examining the effectiveness of different authoritarian propaganda strategies during crises and policy changes. We show that propaganda has significant limitations precisely when regimes need it most.

Existing research, primarily conducted during “normal” times, identifies two main objectives of authoritarian propaganda. The first goal, known as “soft propaganda,” aims to persuade the public to align with government policies (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Shao and Yiqing2022). More crucially, it seeks to indoctrinate the population regarding the merits of the regime (Adena et al., Reference Adena, Enikolopov, Petrova, Santarosa and Zhuravskaya2015; Rozenas and Stukal, Reference Rozenas and Stukal2019; Mattingly et al., Reference Mattingly, Incerti, Changwook, Moreshead, Tanaka and Yamagishi2024) or foster emotional attachment to it (Greene and Robertson, Reference Greene and Robertson2022; Mattingly and Yao, Reference Mattingly and Yao2022). For example, Adena et al. Reference Adena, Enikolopov, Petrova, Santarosa and Zhuravskaya(2015) find that pre-World War II German politicians used propaganda radios to cultivate support for their respective patrons, while Mattingly et al. Reference Mattingly, Incerti, Changwook, Moreshead, Tanaka and Yamagishi(2024) show that Chinese propaganda convinces a global audience of the superiority of the “China model” over the American one. Soft propaganda also involves broadcasting negative news about foreign countries to distract the public from domestic problems or to portray alternative regimes as undesirable (Rozenas and Stukal, Reference Rozenas and Stukal2019; Carter and Carter, Reference Carter and Carter2023; Deng, Reference Deng2024).

In contrast, some scholars argue that the primary purpose of authoritarian propaganda is not persuasion but intimidation, termed “hard propaganda.” Hard propaganda is designed to create cults of personality around supreme leaders, facilitating the domination of both the general public and junior officials (Shih, Reference Shih2008; Huang, Reference Huang2015; Wedeen, Reference Wedeen2015; Carter and Carter, Reference Carter and Carter2023). It can also signal regime capacity and deter potential rebellion. Rather than intending to persuade or indoctrinate, hard propaganda’s crude and heavy-handed content itself signals regime strength, which poses a threat to political oppositions (Huang, Reference Huang2015; Reference Huang2018; Carter and Carter, Reference Carter and Carter2023).

We theorize that both “soft” and “hard” propaganda strategies have significant limitations during crises when public dissatisfaction is mounting and the central government is under pressure to respond. Hard propaganda often emphasizes the central government’s unwavering commitment to its objectives, regardless of the costs. While such heavy-handed and top-down style slogans signal the regime’s overall strength and the central government’s policy resolutions, sudden shifts in direction can inadvertently legitimize citizen resistance, especially resistance against previous policy and local authorities that are lagging behind central policy changes. These grassroots contentions, a predominant form of collective action in authoritarian regimes, often harness the rhetoric and commitments of the powerful central government to resist the exercise of power at the local level (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien1996; O’Brien and Li, Reference O’Brien and Lianjiang2006). This issue becomes particularly acute during crises, when citizen resistance is more frequent, and the abandoned policy remains fresh in memory, with lingering effects at the local level. The reversal of hard propaganda from the party center can also retrospectively lend legitimacy to protests before the policy change.

When propaganda messages assume a “soft” tone with the intention to persuade, it often emphasizes that government policies are prudent and backed by scientific evidence. The efficacy of soft propaganda, if achieved, amplifies the public belief in the government’s policy-making expertise, consequently cultivating support for both the government and its policies. Yet, such rhetoric often leaves little flexibility for policy reversals because propagating the reversed policy direction needs contradictory scientific evidence. During crises, when the populace tends to exhibit dissatisfaction with the status quo, the government faces the dilemma of either defending an unpopular policy as prudent and rational or changing course and contradicting previous messages, harming the overall credibility of the government. To compound the issue, the more convincing the previous soft propaganda was, the harder it became to justify a policy change. Similarly, the more persuasive the current soft propaganda is, the more unreasonable the previous policy and its associated propaganda seem. Thus, even if soft propaganda effectively argues for policy changes during political crises, it often undermines public evaluations of the government due to the conflicting narratives it creates.

To test our theoretical expectations, we focus on China, a sophisticated autocracy with a highly institutionalized propaganda apparatus. Specifically, we leverage the turbulent period of China’s COVID policy reversals in late 2022 and conduct an original survey experiment in December 2022. For over 2 years since the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, China steadfastly implemented the most stringent “Zero-COVID” policy, with state propaganda relentlessly championing the superiority of China’s COVID responses through both soft and hard propaganda rhetoric. However, in November 2022, social unrest mounted against the draconian COVID restrictions, and the Chinese authorities swiftly reversed nearly all COVID restrictions in early December. Following this policy change, propaganda then shifted to downplaying COVID’s threat and promoting reopening, again using both soft and hard strategies.

Analyzing China’s COVID propaganda offers three unique advantages. First, the 3-year-long “Zero-COVID” policy profoundly disrupted daily lives, causing quarantines and city-wide lockdowns, and eventually led to protests across the country, a rarity since 1989. Consequently, COVID propaganda carries significant political implications. Second, the abandonment of “Zero-COVID” marks a dramatic reversal of a fundamental policy. By comparison, it took years to move from the initial relaxation to the final abolition of the “One-Child Policy.” This leaves both propaganda supporting and opposing “Zero-COVID” vivid in citizens’ minds, providing a rare window to study conflicting propaganda. Finally, diverse propaganda messages were used to promote COVID policies, ranging from hard to soft and from pro-lockdown to pro-reopening stances, offering a valuable opportunity to study various strategies on a single issue.

In our experiment, respondents randomly receive propaganda messages with either hard or soft rhetoric. We then measure three outcomes: evaluation of the government’s COVID response, willingness to protest local COVID restrictions, and COVID policy preferences. Conventional wisdom suggests that propaganda is effective, with soft propaganda expected to boost support for the government and its policies and hard propaganda likely to reduce protest willingness. However, we are skeptical. We predict soft propaganda will not improve public assessments of government performance, especially when contradictory. We also hypothesize that only contradictory hard propaganda will deter protests by seeming too heavy-handed, while non-contradictory hard propaganda might actually increase the perceived legitimacy of protests. We do not have specific expectations for soft propaganda’s effect on deterrence or hard propaganda’s persuasiveness.

1. Experimental design

The preregistered survey experiment took place in December 2022 in China.Footnote 1 We recruited 3,314 respondents through a Chinese online survey platform and then redirected them to an American-based survey website, Qualtrics. To protect our participants, all data related to the experiment are directly and securely stored in the United States, with the Chinese survey company and government having no access to it. Our sample’s gender distribution, age composition, and regional representation resemble the demographic makeup of Chinese Internet users.

The survey began by collecting information about the demographics and political predispositions before presenting the respondents with a short news report from Xinhua News Agency, a state-run media organization. Participants were randomly assigned to one of five groups, with four groups receiving different excerpts related to official propaganda on COVID policy, and the fifth group receiving a placebo vignette. All vignettes are actual excerpts from Xinhua news reports to preserve experimental realism.

1.1. Treatment

Figure 1 demonstrates the treatments in each experimental group. In treatment groups 1 and 2, we present respondents with a single vignette containing propaganda messages from December 2022 that advocate for the relaxation of COVID restrictions and the reopening of Chinese society. In the first group, the message is “soft,” rationalizing the reopening by referencing assessments from public health officials and medical experts, suggesting that the Omicron variant of SARS-COV-2 is now comparable to seasonal flu in terms of virulence. In contrast, in the second group, the rhetoric is “hard,” forcefully commanding the reopening and adjustment of epidemic control measures, using wooden language and threatening slogans.

Figure 1. Procedure of the survey experiment.

These two groups resemble existing propaganda and media exposure experiments conducted during “normal” times, where respondents are shown a single vignette (or sometimes video) about a piece of news (Huang, Reference Huang2018; Mattingly and Yao, Reference Mattingly and Yao2022; Pan et al., Reference Pan, Shao and Yiqing2022). We are particularly interested in the second treatment group as we theorize hard propaganda during crisis times might not effectively discourage political protests against local authorities. Specifically, exposure to hard pro-reopening rhetoric from Xinhua, a central news outlet, will heighten respondents’ belief that resistance against local COVID restrictions is “rightful” and justified (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien1996).

To further mimic the conflicting propaganda messages during crises and policy reversals, in treatment groups 3 and 4, before showing the December propaganda messages supporting reopening, we first present respondents with propaganda messages from November 2022 supporting the “Zero-COVID” policy. In other words, respondents in treatment groups 3 and 4 are shown two different vignettes—one promoting lockdown measures and then one supporting reopening. The timing of two propaganda messages is close enough during crises that seeing conflicting propaganda is still realistic. As in the earlier treatment groups, these messages adopt either a “soft” or “hard” rhetoric.

In treatment group 3, respondents first encounter “soft” propaganda promoting the “Zero-COVID” approach. This includes references to public health experts and scientific data on the mortality of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Afterward, they see the same pro-reopening soft propaganda shown to treatment group 1. In contrast, treatment group 4 is exposed to “hard” propaganda, which strongly endorses the “Zero-COVID” policy, featuring a speech by General Secretary Xi Jinping at a Politburo meeting that calls for unwavering commitment to the policy and the directives of the party center. It was then followed by the same pro-reopening hard propaganda message shown in group 2. Our primary interest lies in treatment group 3, where we anticipate that the conflicting messages will undermine the effectiveness of the soft propaganda, resulting in lower evaluations of the government. In sum, treatment groups 1 and 2 received only pro-reopening messages, while groups 3 and 4 received both pro-Zero-COVID and pro-reopening messages. Treatment groups 1 and 3 use soft propaganda strategies whereas groups 2 and 4 use hard language.

Finally, participants assigned to the control group are shown a placebo vignette: Xinhua’s report on the simultaneous appearance of the Moon, Mars, and Jupiter in the celestial expanse. While unrelated to COVID policies, this news was published in close temporal proximity to the COVID policy reversal. Thus, it serves as an ideal placebo. The details of all vignettes can be found in Online Appendix D.

1.2. Measurement

Following the vignettes, we measured respondents’ COVID Policy Preference and Assessments of Government Performance to evaluate propaganda’s persuasive power. COVID Policy Preference was assessed with three questions on strict lockdowns, restricting foreign arrivals, and using health code and contact tracing, with a principal component analysis compiling these into a single score. Assessments of Government Performance asked if respondents viewed the last 3 years’ COVID policy as a success or failure.

We also measured Willingness to Protest by presenting a hypothetical scenario of a 7-day lockdown, common during the Zero-COVID phase, and gauging respondents’ likelihood of participating in protests. This serves as the primary measure of propaganda’s deterrence effect. Additionally, we assessed Perceived Protest Rightfulness by asking if respondents believed the protest would be deemed rightful by the state. All outcomes were measured on a seven-point scale, and we used eight pre-treatment covariates to check for balance. The exact wording of the questions is available in Online Appendix E.

2. Results

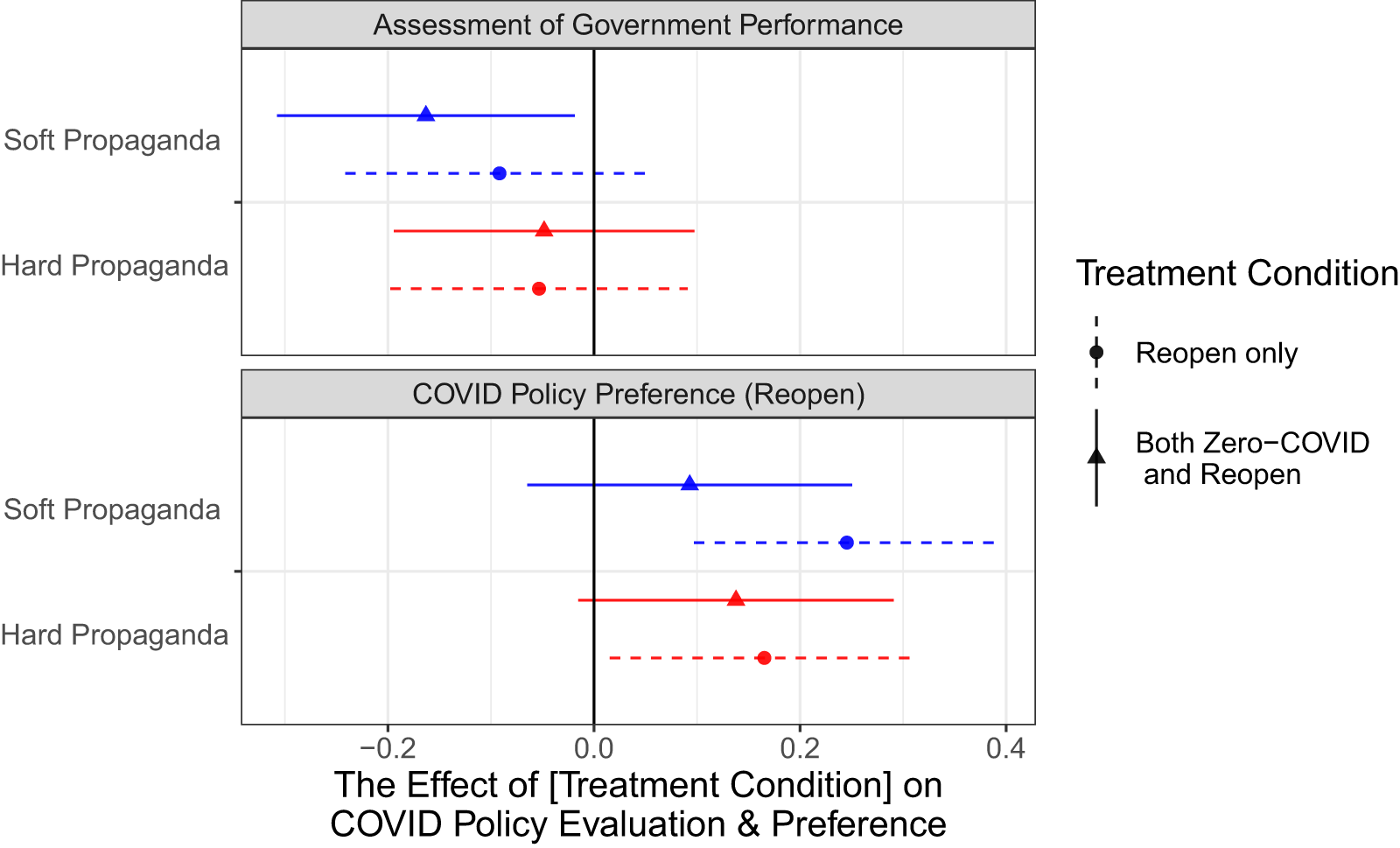

We first focus on the persuasive effects of authoritarian propaganda during crises and policy changes. The upper panel of Figure 2 demonstrates the treatment effects of different types of propaganda messages on individuals’ assessments of the Chinese government’s COVID response, while the lower panel presents the results for individuals’ COVID policy preference with higher values indicating higher preferences for relaxing COVID restrictions and reopening. Each treatment group is compared to the control group, and the plots display the mean differences for each outcome variable, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The dashed lines represent the treatment effects of pro-reopening propaganda messages (treatment groups 1 & 2), while the solid lines represent the treatment effects of conflicting propaganda messages (treatment groups 3 & 4) first advocating for stringent “Zero-COVID” restrictions and then promoting reopening.

As depicted in the upper panel of Figure 2, all propaganda messages, regardless of the rhetoric and content, fail to increase public evaluation of the government’s performance in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. All coefficients are negative, with the treatment effect of conflicting soft propaganda (treatment group 3) significant at the conventional level (![]() $\beta = -0.163$, p = 0.027). The magnitude of the treatment effect represents approximately 12.5% of the standard deviation of the outcome variable, indicating a sizable decrease in the assessment of government performance. Such a finding is consistent with the theoretical argument that soft propaganda has significant limitations during crises when the government is forced to produce conflicting propaganda messages, hindering their persuasiveness.

$\beta = -0.163$, p = 0.027). The magnitude of the treatment effect represents approximately 12.5% of the standard deviation of the outcome variable, indicating a sizable decrease in the assessment of government performance. Such a finding is consistent with the theoretical argument that soft propaganda has significant limitations during crises when the government is forced to produce conflicting propaganda messages, hindering their persuasiveness.

Figure 2. Treatment effects of propaganda on COVID policy assessment and preference.

Nonetheless, while propaganda during crisis times fails to boost support for the government, it is more successful in shifting revealed policy preferences. As shown in the lower panel of Figure 2, when respondents are only presented with pro-reopening propaganda (dashed bars), they become significantly more likely to prefer reopening than restrictions. Notably, these effects remain significant irrespective of the particular rhetorical approach employed. While the point estimate for the treatment effect of soft propaganda is indeed larger (β = 0.245, p = 0.001) than that of hard propaganda (β = 0.165, p = 0.031), the difference between the two estimates is not statistically significant. This suggests that the effect is less driven by the rhetoric being “soft” and persuasive, and more by the shift in the official policy position itself. Even when respondents are first exposed to previous propaganda advocating “Zero-COVID” and then to pro-reopening propaganda (solid bars), respondents still tend to favor reopening, albeit with reduced statistical significance. Thus, it is possible that propaganda does not alter actual policy support but instead makes respondents more comfortable expressing pre-existing support for reopening.

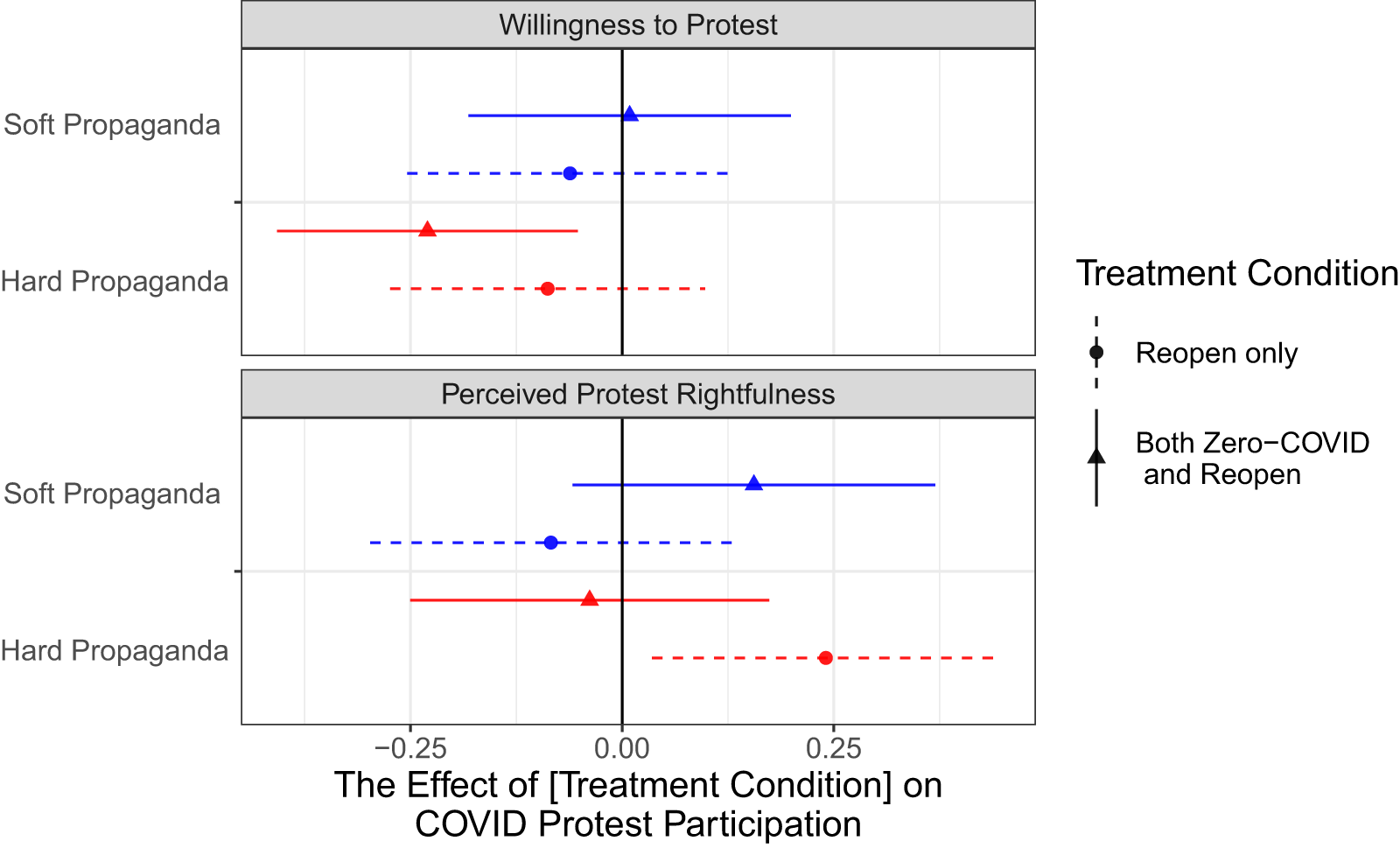

Next, we examine the protest-deterrence effects of authoritarian propaganda during crises. Figure 3 plots the treatment effects of different types of propaganda messages on individuals’ willingness to participate in the hypothetical protest against local lockdown measures (upper panel) and their perceptions of the “rightfulness” of such protests (lower panel). Consistent with existing theories, soft propaganda exerts little effect on deterring potential protest. All four estimates for soft propaganda are indistinguishable from zero.

Figure 3. Treatment effects of propaganda on COVID protest participation.

In contrast, hard propaganda demonstrates higher efficacy in shifting individuals’ beliefs and self-report behavioral tendencies regarding protests against local authorities’ COVID restrictions. Similar to the existing studies that underscore the intimidating effects of authoritarian propaganda (Huang, Reference Huang2015; Reference Huang2018; Carter and Carter, Reference Carter and Carter2023), when respondents are exposed to conflicting hard propaganda messages (solid bar in the upper panel), they become less willing to participate in a hypothetical protest (![]() $\beta = -0.230$, p = 0.011). This could be attributed to the contradicting hard rhetoric further reinforcing the apparent regime strength. Analogous to certain personalistic dictatorships, the unwavering yet inconsistent official stances paradoxically highlight the regime’s uncontested dominance in arbitrarily shaping public discourse (Wedeen, Reference Wedeen2015).

$\beta = -0.230$, p = 0.011). This could be attributed to the contradicting hard rhetoric further reinforcing the apparent regime strength. Analogous to certain personalistic dictatorships, the unwavering yet inconsistent official stances paradoxically highlight the regime’s uncontested dominance in arbitrarily shaping public discourse (Wedeen, Reference Wedeen2015).

Interestingly, these findings provide a micro-level understanding of the structure of China’s propaganda apparatus. Qualitative studies show that hard propaganda is mainly spread through print media to represent ideological orthodoxy, while soft propaganda is used on social media, where outdated content can be deleted (Wang, Reference Wang2024). After all, contradictory hard propaganda can appear deterring, while contradictory soft propaganda is just illogical and counterproductive.

Yet, hard propaganda has its limitations. When its inconsistency is less apparent, as in treatment group 4 (dashed lines) exposed only to pro-reopening propaganda, its protest-deterrence effect disappears (![]() $\beta = -0.088$, p = 0.354). The lower panel of Figure 3 shows this is likely due to an increased sense of protest righteousness against local authorities (β = 0.241, p = 0.022). Clear, heavy-handed propaganda reveals the central government’s policy intentions, leading citizens to view resistance against local authorities implementing the previous policy as more legitimate, thereby garnering public support for collective actions that trouble both central and local governments (O’Brien and Li, Reference O’Brien and Lianjiang2006; King et al., Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013).

$\beta = -0.088$, p = 0.354). The lower panel of Figure 3 shows this is likely due to an increased sense of protest righteousness against local authorities (β = 0.241, p = 0.022). Clear, heavy-handed propaganda reveals the central government’s policy intentions, leading citizens to view resistance against local authorities implementing the previous policy as more legitimate, thereby garnering public support for collective actions that trouble both central and local governments (O’Brien and Li, Reference O’Brien and Lianjiang2006; King et al., Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013).

2.1. Discussion

Before concluding, we address an important issue: Can we trust these survey responses to politically sensitive questions from an authoritarian regime like China? Are the significant outcomes artifacts of preference falsification (Kuran, Reference Kuran1997), resulting from respondents providing “politically correct” answers? Our response is threefold. First, we believe preference falsification is precisely part of the theoretically relevant outcomes. Authoritarian regimes often rule by fear (Young, Reference Young2019), and propaganda is one of the apparatuses autocrats frequently employ to disseminate fear among the population and deter rebellions (Deng, Reference Deng2024). Therefore, we might be more interested in citizens’ “public lies” than their “private truth” (Kuran, Reference Kuran1997), as the ability of propaganda to force the public to lie is sufficient for autocrats to maintain regime stability. Second, we do not believe preference falsification is the primary driver of our results. While propaganda messages demonstrate some efficacy in shifting individuals’ COVID policy preferences, they fail to improve individuals’ assessment of government performance. Such results precisely show that citizens are sophisticated and willing to update their beliefs about the best policy choice while not easily fooled by propaganda and punishing the government for their mismanagement. Finally, we leverage a rare moment of social unrest and a major policy shift in China to conduct our experiment. Due to the chaotic nature of the COVID policy reversal, there is a brief window of political uncertainty in late 2022. Therefore, we believe the social desirability bias, which is normally prevalent in China, might not be as severe during the survey period.

Additionally, we believe it is unlikely that the insignificant results are due to ceiling effects or insufficient statistical power. The average support for government performance within the control group is not overly high (5.13/7), alleviating concerns about inability to detect potentially positive effects. Additionally, our sample size, around 600 respondents per treatment group, is also significantly larger than similar propaganda experiments (e.g., Huang, Reference Huang2018; Pan et al., Reference Pan, Shao and Yiqing2022), alleviating concerns about lack of statistical power.

Finally, while the treatments are intended to remind citizens of official stances rather than create parallel realities, the contradictory propaganda during policy changes can genuinely confuse respondents, making their responses harder to interpret. We also acknowledge that we use a one-shot experiment to capture what could be a dynamic process, a potential limitation despite the ideal timing of this survey to study propaganda during political crises.

3. Conclusion

“Propaganda works.” While scholars debate the mechanisms behind its efficacy, there is broad consensus that authoritarian propaganda is indeed effective. However, most studies demonstrating propaganda’s efficacy were conducted during relatively stable periods, when citizens had little incentive to resist. Few have explored whether propaganda remains effective during crises and policy changes, precisely when regimes need it most. This type of scenario is not uncommon either as one liberty afforded by the monopoly of power to authoritarian regimes is the ability to alter policy and propaganda arbitrarily. This lack of attention to propaganda’s limitations is further exacerbated by the inherent challenge of showcasing evidence of inefficacy, as null results do not necessarily indicate the absence of theoretical and empirical relationships.

We offer a fresh perspective, highlighting the limitations of propaganda strategies. Leveraging the critical moment of China’s COVID policy reversal in late 2022, we use a survey experiment to provide evidence for the inability of both hard and soft propaganda to garner political support. Contradictory soft propaganda fails to persuade citizens to approve of government performance, while excessively one-sided hard propaganda for a new policy may lead citizens to view protests against the previous policy as justified. By showing that our propaganda treatments are effective in changing policy preferences, while concurrently failing to enhance governmental approval, we avoid the methodological challenge of demonstrating propaganda inefficacy and help document a nationwide crisis of political trust in China, rarely seen since 1989.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.10009. To obtain replication material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/57YGZM

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers and the participants at the 2023 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting for their helpful comments and suggestions.