Introduction

The United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS; Washington, DC USA) defines cultural awareness as having “the ability to honor and respect the beliefs, languages, interpersonal styles, and behaviors of individuals and families receiving services, as well as staff members who are providing such services.” Reference Wong, Jacobs, Kenyon and Gashel1 The most common definition of cultural awareness refers to an understanding of the differences that exist between the cultures and how those differences, together with socio-political realities, frame one’s interactions with members of other groups. Reference Hart, Toma, Issa and Ciottone2 In the literature, cultural awareness refers to understanding of either inherited or learned patterns of human behavior, such as verbal behavior including language and communication, private events such as thoughts, and public events such as actions or customs. Another important aspect is an understanding of the beliefs held and promoted by religious, racial, ethnic, or social groups. 3 Cultural self-awareness refers to the extent to which one’s own heritage influences perception of self and interaction with others. Reference Lu and Wan4

The subject of cultural awareness has received more attention in the literature since the benefits of cultural diversity became a more prominent focus within many large organizations or institutions, even including militaries. Reference Mackenzie and Miller5–Reference Johnson, Lenartowicz, Apud and Graduate8 Achieving cultural awareness was found to be an important step towards achieving understanding and acceptance of differences leading to effective operations or services. Reference Kealey and Protheroe9 Cultural competence has been argued to be defined by the ability to utilize knowledge and cultural awareness and shape that into practical and effective interventions. Reference McPhatter and Ganaway10 Recent studies have found that despite the push among many organizations to train their staff to improve multicultural cooperation, there has been a lack of such training among non-governmental organizations (NGOs) whose work consists of international humanitarian aid across countries and cultures. Such cultural training, if provided, is often brief, lacking robust, evidence-based curriculum and cultural specificity, due to time or other barriers specific to a mission. Reference Hart, Toma, Issa and Ciottone2 Such non-standardized cultural awareness training may not be as comprehensive and can result in redundancy and miscommunication.

This study aimed to create a list of cultural awareness topics which a consensus of cultural awareness and NGO experts believe would be necessary in the development of a standardized, comprehensive NGO cultural awareness education program.

Methods

Modified Delphi Process

A modified Delphi process was selected to develop an evidence-based expert-consensus curriculum for cultural awareness education of international NGO field staff. This established academic research approach has been used to create curricula for other educational programs, including geriatric medicine and dignitary medicine. Reference Hsu, Kessler and Parker11,Reference Al Mulhim, Darling and Sarin12 It is thus well-suited to the development of a consensus curriculum in the field of cultural awareness and was employed in this study using a pre-determined protocol.

Focus Group

A focus group of experts in cultural awareness, identified by their history of teaching and publication, as well as decision makers in prominent international NGOs, identified by their current or former leadership positions, was identified. This group included academicians, educators, administrators, and leaders of field deployments (Table 1). This study was determined to be exempt by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board (Boston, Massachusetts USA; Protocol # 2020P000107) as well as the Simmons University Institutional Review Board (Boston, Massachusetts USA).

Table 1. Expert Demographics

Note: Years of experience in each category only asked of those who reported that was their field of expertise.

Abbreviations: NGO, non-governmental humanitarian organization; ABA, Applied Behavior Analysis; ASD, Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Rounds of Survey

Experts were initially contacted by email and invited to participate in the Delphi process. Those who agreed to participate were provided with a link to an online questionnaire for the demographics questionnaire, followed by the first round of the Delphi process. The first round of the survey contained a single question asking participants “What topics do you feel are necessary in the creation of a comprehensive cultural awareness curriculum which would benefit all staff of humanitarian non-governmental organizations?” Participants were asked to propose between 10 and 15 individual curriculum competencies.

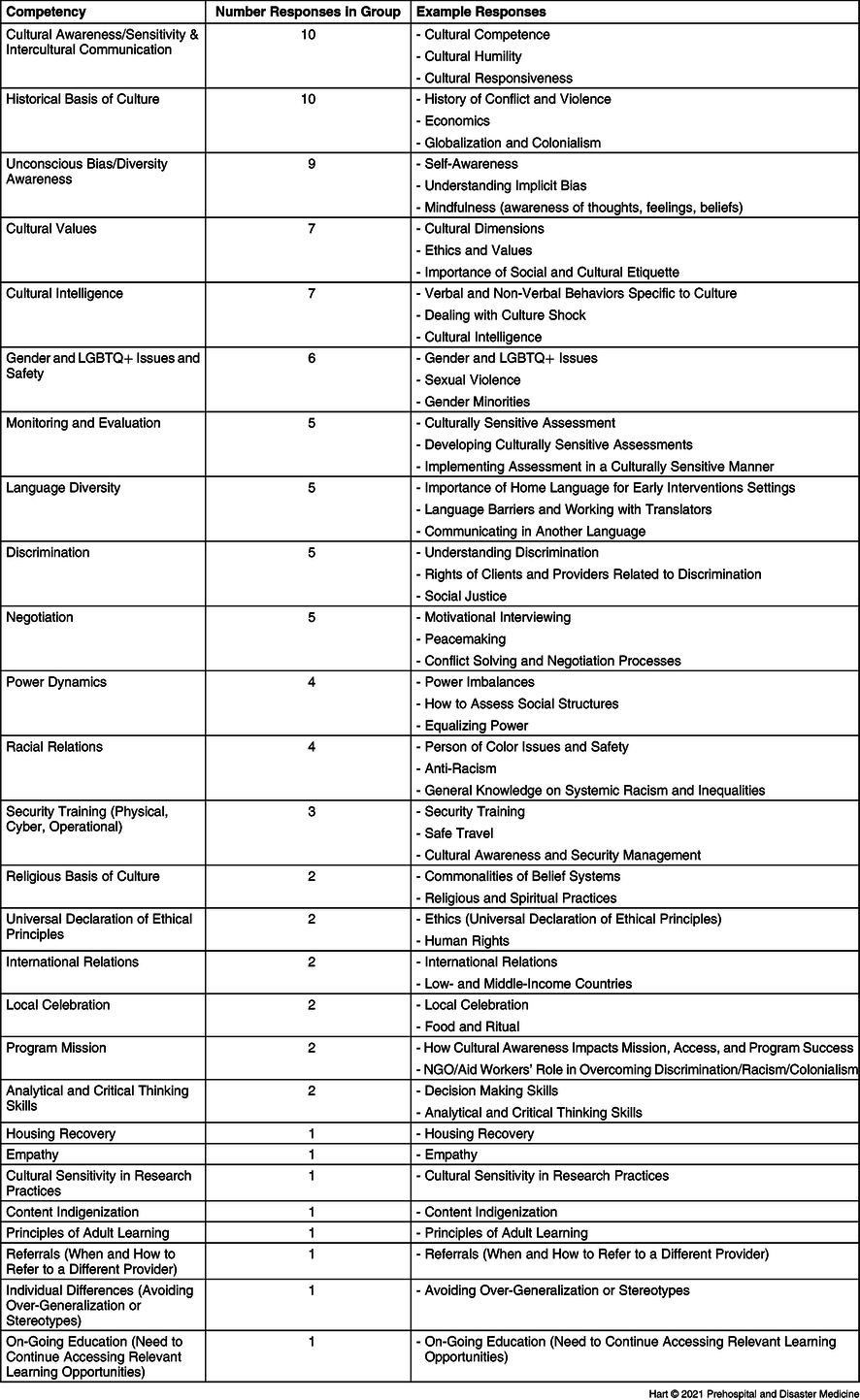

The results of the first round of the Delphi process were reviewed by the research team. Items suggested by the expert panel were grouped by topic and then turned into individual curriculum competencies. These were then reviewed for agreement by the entire research team to determine that there were no expert suggestions which were not represented, and that the suggestions were appropriately grouped (Table 2). These curriculum competencies were then used to create the questions in the second-round questionnaire.

Table 2. Round 1 Responses as Organized into Curricular Competencies

Abbreviations: LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other sexual identities; NGO, non-governmental organization.

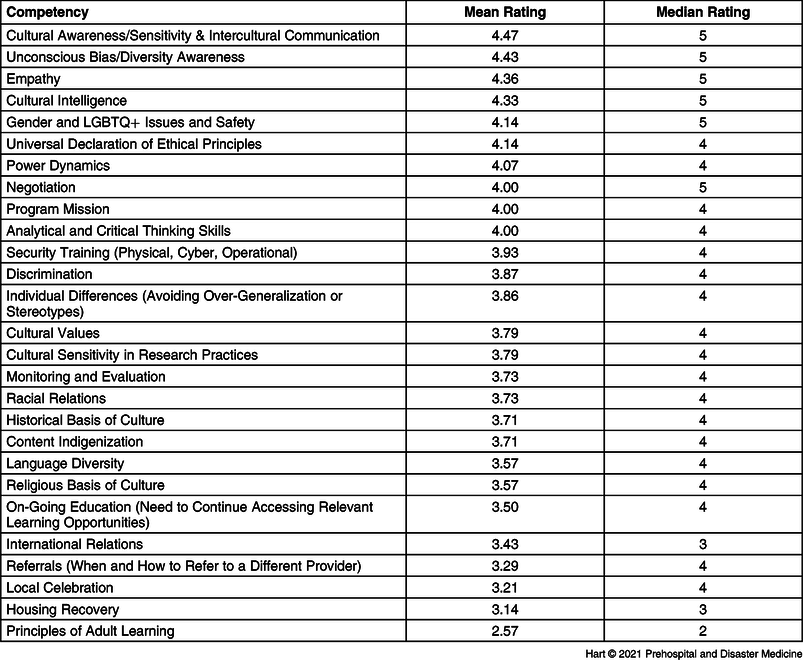

In the second round, participants were asked to rank each curriculum competency on a five-point Likert scale, with five signifying “Very Important” and one being “Not Important.” Emails were sent individually, and results were collected anonymously. Each item was pre-determined to need an average rating of 4.0 or greater to be considered “Important” for inclusion in a proposed curriculum. The mean was chosen as opposed to the median value due to the fact that all of the competencies were proposed by an expert on the panel, and so were expected to have relatively high and similar median responses. Both mean and median values are given in Table 3.

Table 3. Average Round 2 Ratings of Curricular Competencies on 5-Point Likert Scale

Abbreviation: LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other sexual identities.

Results

A total of 19 of the 30 experts who were contacted agreed to participate in the study, with 16 completing all rounds of surveys. Table 1 contains demographics demonstrating the depth and breadth of experience of the experts surveyed. The majority of participants had five or more years of experience in their field, with nine having ten or more years of experience. None of the organizations where the participants work had a specific religious mission.

Table 2 contains the results of the first round of the survey of the expert panel, which lead to 27 curriculum competencies after all responses were analyzed and collated. “Cultural Sensitivity and Intercultural Competence” and “Historical Basis of Culture” were the most proposed topics. Additional highly proposed items included “Unconscious Bias,” “Cultural Values,” and “Cultural Intelligence.”

Ratings of each curriculum during the second round are listed in Table 3. After the second round of the survey, expert consensus on the curriculum created a list of ten competencies, which are reported in Table 4. Of note, although there were curriculum competencies related to gender, race, religion, and language diversity, only “Gender/Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Other Sexual Identities (LGBTQ+) Issues” met criteria for inclusion in the final curriculum. The experts also included competencies in “Power Dynamics,” “Universal Declaration of Ethical Principles,” “Empathy,” and “Critical Thinking Skills.”

Table 4. Curricular Competencies which Achieved at least a 4.0 Average Rating on a 5-Point Likert Scale

Abbreviation: LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other sexual identities.

Discussion

A recent study confirmed that a sample of global NGOs did not have formal cultural awareness staff training programs available. Reference Hart, Toma, Issa and Ciottone2 This finding is potentially problematic given the nature of international humanitarian work. Without formal cultural awareness training, NGO staff tasked with supporting people globally may lack the necessary skills to properly assist individuals from different cultures. For example, cultural awareness may impact humanitarian work focused on supporting efforts to contain viral outbreaks, as seen with the Ebola and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemics. For each health crisis, it is evident how critical knowledge and best practices related to interacting with local communities assists with mitigating the transmission of a fatal disease. With Ebola, humanitarian workers required knowledge of local religious practices that may have contributed to the spread of this disease. Reference Manguvo and Mafuvadze13 With COVID-19, efforts related to addressing reduced health education may serve to be vitally important when attempting to reduce transmission risk. Reference Shah, Karimzadeh, Al-Ahdal, Mousavi, Zahid and Huy14

This study’s results identified several primary content areas for a cultural awareness training program. Areas include: general knowledge of fundamental vocabulary and ethical principles, self-awareness considerations, equity promotion practices, communication and rapport-building standards, problem solving, and understanding cultural intelligence. Each topic may be addressed using a variety of documented training methods that include a combination of preceptor and practical exercises which incorporate immersion, case analysis, role play, journaling, and self-assessment. Reference Benuto, Singer, Newlands and Casas15 Curriculum recommendations by topic area are presented.

Cultural Awareness/Sensitivity and Intercultural Communication

This refers to the integration of best practices related to understanding and acknowledging cultural variables that impact a particular group’s way of accessing care. Without cultural awareness, provider bias may influence decision making and in turn, the provider may fail to accommodate service recipients in a manner that is culturally sensitive. Reference Padela and Punekar16

Cultural Intelligence

This topic incorporates a cultural anthropological approach to studying and understanding different groups. In particular, NGO practitioners may examine common beliefs, family structure, gender or sex standards, and religious practices of the population served. For instance, spiritual beliefs have been identified as a variable that may influence a patient’s willingness to seek and adhere to treatment. As a result, practitioner training on clinical practices evaluating the role of spiritual beliefs for a given population contributes to delivering culturally sensitive care. Reference Ezenkwele and Roodsari17,Reference McMinn, Bufford and Vogel18

Unconscious Bias/Diversity Awareness

Awareness promotes recognition of biased responses toward specific characteristics valued by a social group (eg, race/ethnicity, age, gender, weight). Reference FitzGerald and Hurst19 Acknowledging that this is an implicit phenomenon is an initial step toward identifying behavior that can be changed. Reference De Houwer20 Mindfulness may be an effective method to bring awareness and help in recognizing the activation of unconscious bias and its relevance to clinical practice. Reference Teal, Gil, Green and Crandall21

Universal Declaration of Ethical Principles

A declaration addresses fundamental assumptions and standards related to protecting service recipients. Instruction centered on core principles and identifying how ethical standards in practice may differ from other cultures should be provided. This includes giving the utmost attention to the upholding of basic human rights. Reference Irvine, McPhee and Kerridge22

Gender and LGBTQ+ Issues and Safety

Recognition of gender issues is also a fundamental aspect of rendering culturally relevant care. Emphasis should be placed on understanding social-justice-related matters, such as anti-genderism movements, while also examining systemic failures to distinguish between health care needs of cis-gendered and non-cis-gendered persons. Reference Corredor23,Reference Namer and Razum24 Other gender-related health care matters such as the correlation between experiencing discrimination and the onset of post-traumatic stress should be examined. Reference Alessi, Martin, Gyamerah and Meyer25

Analytical and Critical Thinking Skills

Addressing practice issues related to cultural awareness is closely tied to the critical thinking skills of humanitarian workers. Decision making and analytical skills are a cornerstone of high-quality professional training programs. A fundamental aspect of critical thinking includes self-awareness skills. Self-awareness skills may prevent bias in decision making. As such, training programs should consider methods for introducing critical thinking skills and evaluating outcomes. Reference Papp, Huang and Lauzon26,Reference Levy27

Negotiation

Given that culturally-related differences may influence negotiation, decision making that incorporates cultural considerations is also important. For example, regional social norms may influence conflict resolution or resource allocation. In which case, approaches to trust building in a given relationship may serve as a valuable intervention. Motivational interviewing is a useful technique for supporting this approach. Reference Brett, Gunia and Teucher28,Reference Sommers-Flanagan29

Program Mission

Organizational mission statements are a recognized indicator of a commitment to and appreciation of diversity. Many NGO humanitarian programs may also wish to incorporate mission statement analysis and/or development exercises into training efforts. In addition to highlighting how cultural variables are valued within an organization, program missions may also address the importance of anti-racism efforts. Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies30–Reference Meacham and Barrett32

Power Dynamics

Confronting power dynamics present in humanitarian efforts is a documented phenomenon. Reference Wosinska, Cialdini, Barrett and Reykowski33 Cultural capital is a variable that may influence power imbalances and resource allocation. Humanitarian organizations should consider assessing social structures and evaluating acculturation as part of organizational operating procedures. Taking this into account may assist with mitigating risk based on the cultural practices or beliefs of a given region. Reference Siawsh, Peszynski, Young and Vo-Tran34

Empathy

The reliable demonstration of empathy has been cited as an important variable in many relationships. While this construct varies widely depending on the source, the notion of empathetic compassion is generally accepted as an expected interpersonal skill. How cultural awareness is related to empathy should be emphasized throughout the training process. Doing so may ensure that humanitarian workers are skilled at conveying empathy, recognizing and alleviating suffering, and demonstrating self-compassion. Reference Sulzer, Feinstein and Wendland35

Limitations

In this study, the response rate overall for the modified Delphi process was lower than initially anticipated, with 67.9% of those approached agreeing to participate. However, among those, 84.2% completed all rounds of the survey. The COVID-19 pandemic spread rapidly during the time when this study was performed, and the increased need for humanitarian aid during this period generated unprecedented demand for the services of experts in the field. It is also unclear if consensus opinion would change post-COVID-19.

The dearth of current literature discussing cultural awareness in NGOs could also be problematic. Although the participants were chosen for being leaders in their field, the lack of current consensus and evidence-based educational material could prevent otherwise important topics from having been proposed. It is anticipated that future research may build on and confirm notable findings from this study.

Conclusions

This study employed a modified Delphi approach to establish expert consensus regarding a suggested core set of cultural awareness curricular competencies for NGO staff. Given that NGOs serve communities internationally, and that there is a lack of consensus regarding minimum cultural awareness training requirements, a core curriculum is of great importance. A suggested set of competencies would include Cultural Awareness/Sensitivity, Unconscious Bias/Diversity Awareness, Empathy, Cultural Intelligence, Gender and LGBTQ+ Issues and Safety, Universal Declaration of Ethical Principles, Power Dynamics, Negotiation, Program Mission, and Analytical and Critical Thinking Skills. While this study highlights these content areas based on a consensus rating of 4.0, future investigations should explore additional topics with a consensus rating of 3.5 or higher.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Jescah Apamo-Gannon, PhD, BCBA, LABA; Robyn M. Catagnus, EdD, LBS, BCBA-D; Peter Lundgren; Breeda McGrath, PhD; Pamela Olsen, PhD, MSEd, BCBA; Guitele J. Rahill, PhD, LCSW; Kenny Kurdvin Rasool; Rocio Rosales, PhD, BCBA, LABA; Kylan Turner, PhD, BCBA-D, LBA; Simone Palmer, PhD, BCBA-D, LABA; and many others without whom this study could never have been completed.

Conflicts of interest/funding

There was no funding used in this study. None of the authors report any conflict of interest.