Introduction

Many studies proved that in countries where primary care (PC) system is stronger, the healthcare system performs better (Macinko et al., Reference Macinko, Starfield and Shi2003). Strong PC has to response to the patients’ needs, expectations and preferences as well (Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Groenewegen, Hansen and Black2011). There is a big variation between individuals, therefore at the patients’ level as well. What do patients expect the general practitioners (GPs) to take within the consultation and to what extent are these expectations fulfilled? What factors influence the expectations of the patients and the actions of GPs? (Webb and Lloyd, Reference Webb and Lloyd1994). Why and when do patients visit doctors? They could have been different influence on daily activities and symptom burden, such as the total number of symptoms experienced by each person (Elnegaard et al., Reference Elnegaard, Pedersen, Andersen, de-Pont Christensen and Jarbøl2017).

In 2010, the three-year Quality and Costs of Primary Care in Europe (QUALICOPC) study was planned, aiming to compare and analyse how the primary health care systems of 35 countries perform in terms of quality, cost and equity. The study analysed three levels of PC. The service provision level, covering characteristics of the GP practice, organisation and the type of services that are delivered and the patient level, where the users of services experience whether the care provided responds to their needs and expectations (Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Boerma, Kringos, De Ryck, Heinemann, Greß, Murante, Rotar-Pavliⓒ, Schellevis, Seghieri, Van den Berg, Westert, Willems and Groenewegen2013).

Family physicians/GPs were chosen as one of the survey subjects. Beside GPs, their patients were also approached and questioned using 2 other questionnaires, to explore their expectations before and their experiences after using the services.

The aim of this paper was to describe and evaluate the expectations, personal values and experiences of Hungarian people who attended to PC services, based on the information collected within the Hungarian arm of the QUALICOPC Study, using two questionnaires. Two questionnaires, developed by the QUALICOPC researchers, were used. In each participating country, the response target was 220 GPs and 2200 patients (10 per each).

The questionnaires were translated in the respective national language(s) via an official forward- and back-translation procedure. The Patient Values questionnaire contained 19 questions (statements with multiple choice answers), four questions focused on communication between GPs and patients. Both questionnaires were previously tested and validated (Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Boerma, Kringos, De Ryck, Heinemann, Greß, Murante, Rotar-Pavliⓒ, Schellevis, Seghieri, Van den Berg, Westert, Willems and Groenewegen2013).

The Patient Experiences questionnaire included 41 multiple choice questions, asking to what extent the patient agrees with the statement given. There were questions on the patient’s background and socio-economic status, perceived constructed for patients.

Method

Structuring the questionnaires, study design

Health, reason for visiting the GP, and visits to medical specialists and hospitals, experiences with ‘continuity of care’, use of medical records and time slot, available for patient. Quality of care as experienced by patients, accessibility of care, divided into physical and financial access. There were inquiries on home visits and waiting times, towards equity in access and equity in treatment, experiences of coordination in the case of referral, on treatment by a practice nurse, about patient’s involvement in decision making and referrals, beside their adherence to the treatment plan. Comprehensiveness of services offered by the GP was also probed in a question about patients’ views on the breadth of the clinical task profile of services.

Distributing questionnaires, settings

The study centre of the Hungarian arm of QUALICOPC project was established at the University of Debrecen, with close cooperation with the other Departments of Family Medicine (Budapest, Pécs, Szeged). An advertisement was issued to recruit participating GPs in the whole country. Two hundred-twenty two GPs who wanted to participate were selected randomly, based on the order of application. Population density and expected geographically representativeness were also considered (Rurik et al., Reference Rurik, Boerma, Kolozsvári, Lánczi, Mester, Móczár, Schäfer, Schmidt, Torzsa, Végh and Groenewegen2012).

During the study period (2012–2014), the questionnaires were transported to the practices by educated fieldworkers, who were usually medical students. They gave one questionnaire per practice, to the nearest patients in the waiting room (Patients’ value) and contacted nine other patients consecutively, who left the surgery to summarise (Patients Experiences).

Presentation of data

The original order of questions was followed. There were 12 identical questions in the questionnaires; therefore, the overlapped answers were presented together. Distributions are always presented and statistical correlations, when found. In some columns, similar answers were merged. Options, with only a few number of responses were missed.

Statistical analyses were performed with STATA software.

Ethics

The Hungarian Research Ethical Committee in Medicine (TUKEB) approved the study assigned the number: 20024/2011-EKU (643/PI/11.).

Results

The Patient Values questionnaire was filled by 214 persons (139 men, 75 women). Their mean age was 47.2 years (SD ± 17.6).

Younger, more educated persons and women were satisfied better with their health status, when describing their own health in general. Men, older and secondary educated people reported more frequently chronic morbidities.

The Patient Experiences questionnaire was filled by 1935 persons; men: 701 (36%), women: 1234 (64%). Their mean age was 49.6 (SD ± 16.7) years.

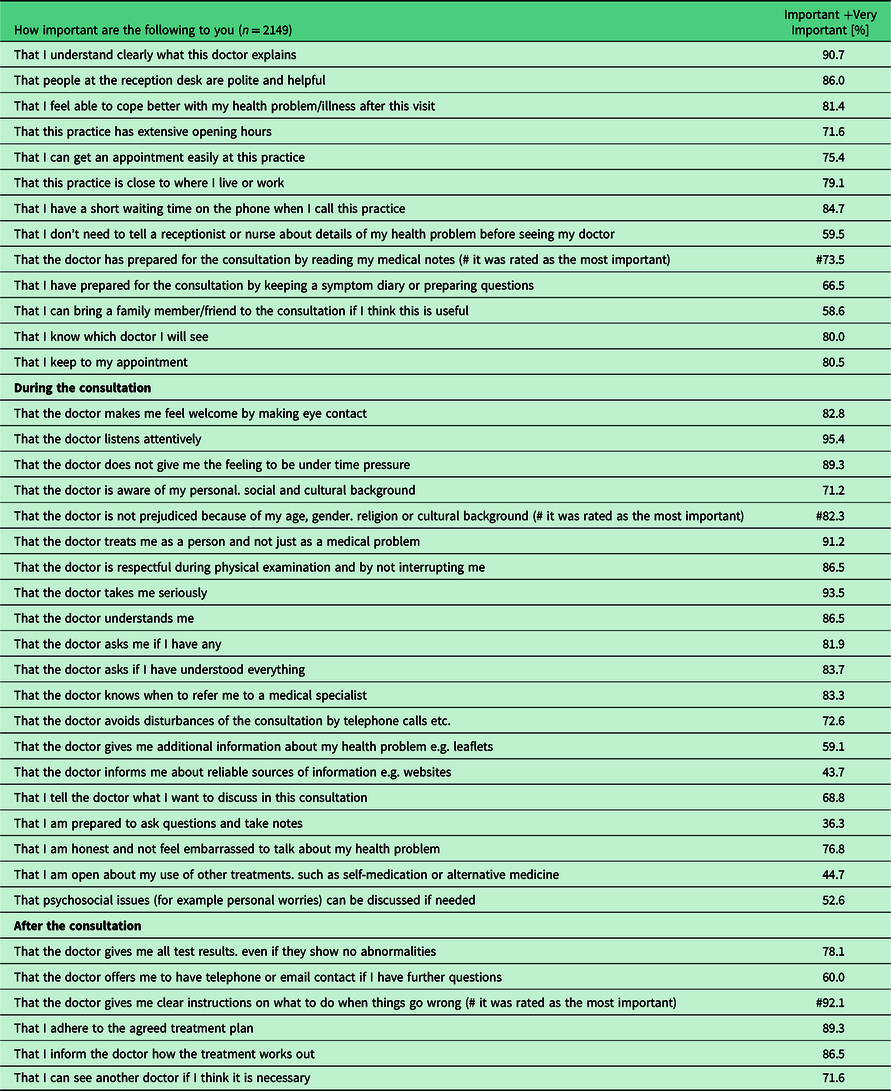

Answers options important and very important were merged into one column in Table 1.

Table 1. The experiences and expectations of patients regarding circumstances, services, provided information, behaviour and consultation’s skills of family physicians

Almost all participants of the two surveys (97.2%) and their mothers (96.3%) were born in Hungary. In the same household, 77.2% lived with adult family members and 33.4% with children under 18 years of age.

Regarding employment status, 37% worked in civil service, 8% as self-employed, 29% retired and 7% student, 8–8% were disabled and unemployed, 52 % estimated their income around and 42.6% below the average.

Women patients preferred significantly (P = 0.007) better to be accompanied by family members to the consultation, and according to their reports, they could cope better with health problems after the visit (P = 0.071). Longer opening was preferred better (P = 0.035) by patients with higher education.

Majority of patients (84.1%) visited their own, registered family physician. Presence of chronic or longstanding conditions (high blood pressure, diabetes, depression, asthma, etc.), description of own health in general, frequency of consultation with GPs in the last 6 months and consultations with specialist in the previous year are presented in the figures of Table 2.

Table 2. Rating own health, presence of chronic condition, frequency of visits by GPs and consultation with specialist, according to age cohort, gender and educational level [percent]

n = 1935.

Women rated their own health to be better. Logistic regression analysis was performed, for gender: correlation coefficient: 0.18, standard error: 0.3, P < 0.001 and 95% confidence interval: [0.11; 12:24].

Patients in the lowest educational category visited more often their GPs, females consulted more frequently, proved by logistic regression analysis. For gender, correlation coefficient: 0.13, standard error: 0.04, P < 0.001 and 95% confidence interval: [0.06; 0.20].

The main reason for actual practice visit was a recent illness (30.7%), medical check-up (24.4%), to get prescription (42.9%) or referral (9.8%), second opinion (12.4%), asking a medical certificate (6.9%). Other reason was mentioned by 16.7%.

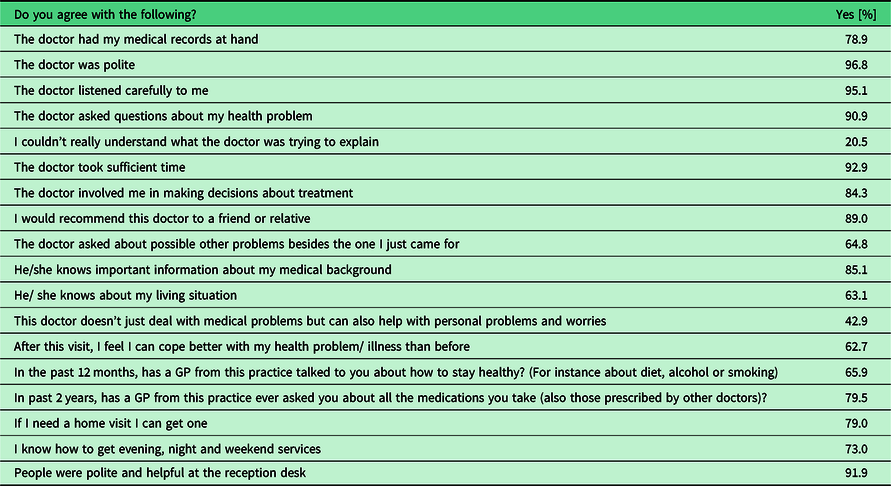

Experiences regarding the actual visit, content of consultation and agreement about the listed statements are described in Table 3. Doctors dealing with not medical problems only, giving more attention to personal problems and worries, were preferred better by patients with higher education (P = 0.01) and by women (P = 0.002). Listening carefully to the patients was requested better by women as well (P = 0.08). In 71.8% of the cases, the time of travel between the home and the GP’s office was less than 20 minutes. Twenty one percent of patients made an appointment, 85% of them got it easy, 29% made it the same day, 37% a day before, while 19% had to wait for 2–7 days. One third of patients had to wait less than 15 minutes, 29 % waited 15–30 minutes.

Table 3. Statements and opinion about the doctor, experiences regarding the actual visit, content of consultation and agreement about the listed statements [percent]

n = 1935.

Negative experiences of patients were listed in Table 4. Most of the patients were informed that there is an option to change their doctors, if not satisfied with manner or services.

Table 4. Negative experiences and feelings of patients

Within the whole study population, 507 persons did postpone or abstain from a visit to the GP in the past 12 months, despite they needed it. Forty four percent of the patients had to cancel their planned visits because she/he was too busy, 11.6% could not get there (physically). Financial reasons were mentioned by 12.8% and only 2.8% did not have insurance. Other reasons for missed visits were 34.7%.

In the case of consultations, 84% of patients believed that their GP was informed about the finding, 61% stated that specialist was informed by the GP appropriately and only 7% experienced difficulties during referral.

Six hundred fifty of the interviewed persons had personal experiences about using out of hour services or emergency departments. The most frequent reasons for encounter were morbidities or complain out of the scope of GP (46.5%), out of the opening time of GPs (21.7%), 5.5% expected a shorter waiting time, 6.8% mentioned that emergency department is more convenient to reach.

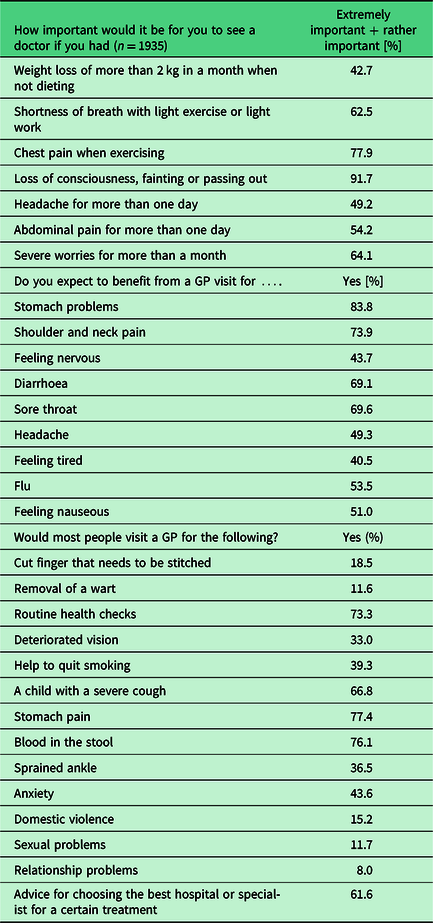

The preferences and expectations of patients with complaints, in the case of the listed symptoms are described in Table 5.

Table 5. Preferences and request for GP services in presence of the listed symptoms [percent]

Only 22.8% of patients were examined or treated by a nurse in the GP’s practice. Patients have a great confidence to their GPs. The statement ‘In general, doctors can be trusted’ were strongly agree by 33.5%, simple agree by 61.3% of the questioned persons

Discussion

Main findings

Patients’ expectations are mainly focusing on professionalism, comfort and accessibility of services.

In professional term: updated knowledge and good manners of doctors, wide scope of complaints to be able to solve, easy to get prescriptions, no barriers to referrals, common decision making about treatment, in respect of the clinical outcomes and also the emotional and human features of the consultation are the highlights of the patient’s expectations.

Preferences regarding circumstances, facilities, courteous communication, clear instructions, adequate information about living circumstances, social and cultural background of the patients were mentioned as well.

Easy access to services, availability and short waiting time, option for home visit, not pressured by time during consultations are also expected.

Limitations

Our study was focused only to the Hungarian characteristics; answers of the patients about their preferences and experiences should be evaluated by taking into consideration specific national traits and a variety of PC provision depending strongly from the personality and available infrastructure of the physicians.

It is not sure that questioned persons are representative in social and economic points of view.

After translating and launching the questionnaire, there was no option to clarify questions having different meanings in different countries.

Being part of an international study, we had to follow the original protocol, recruitments and presentations of the findings.

Before and after this study no such a survey was performed in Hungary. Since structure and utilisation of PC did no change in the past years, these findings could be valid nowadays as well.

There are no financial or administrative restrictions on the availability of PC services in Hungary. It can be used by all citizens, although a social insurance ID card is required before enrolment into a practice.

Hungary is relatively a closed country, hence almost all of the participants (also their mothers) were native Hungarians, and only small percent belonged to ethnic minority. According to the effective legislations in Hungary, it is strictly forbidden to register ethnic or national origin in any medical or official files. In the neighbouring Slovenia, where 6.5% of the PC population are migrants, often experiencing negative attitude from GPs (Jakič and Rotar Pavlič, 2016).

Walk-in accident and emergency services have been established in the Hungarian hospitals only in the last two decades; patients tend to visit them only if PC services are not available.

In the Hungarian primary care, there are no traditions of appointments; patients were served by the order of arrival. The ratio of appointments is continuously increasing due to the order of the Minister of Health. These scheduled services are becoming increasingly popular.

The time waiting for appointment is usually longer in Canada (Premji et al., Reference Premji, Ryan, Hogg and Wodchis2018) and in the Nordic countries (Tolvanen et al., Reference Tolvanen, Koskela, Mattila and Kosunen2018), especially for older patients.

There were only small differences between expectations of different age groups; older patients were more satisfied with the care, perhaps their expectations were lower (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Rowe and McKee2013). Higher scores of experience may not illustrate better consultations as such; it is the lower levels of initial expectations that determine the level of patient satisfaction (Ogden and Jain, Reference Ogden and Jain2005). The results revealed that patients with greater numbers of their expectations met reported significantly higher satisfaction with the consultation than those with lower numbers met (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Weinman, Dale and Newman1995). Generally, GP patients reported higher pre-visit expectations and post-visit met expectations, reflecting chiefly doctor-patient communication style and the doctor’s approach to providing detailed information (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Rowe, Lambert, Waddington, Mahtani, Kenten and Francis2012).

Referrals of patients from the primary to specialist care are important in all health care system. Patients were most positive if the physician had initiated the referral, which supports the gate-keeper role of the GP (Rosemann et al., Reference Rosemann, Wensing, Rueter and Szécsényi2006). As gate-keeping is very weak in Hungary, the preferences of patients are mostly respected. Some specialists could be accessed without referral. Obtaining a letter of referral is often the reason why GPs are contacted; the referrals to specialist are often requested by patients, mainly in the bigger cities. The preferences and expectations of Hungarian patients were not always in agreement with their experiences and values. Findings in the literature regarding the relationship between strong PC and the responsiveness to patient expectations and needs are inconclusive (Ashworth and Armstrong, Reference Ashworth and Armstrong2006). Patient satisfaction was found to be lower in countries where the access to specialist services was regulated through gate-keeping (Bensing et al., Reference Bensing, Deveugele, Moretti, Fletcher, van Vliet, Van Bogaert and Rimondini2011; De Maeseneer et al., Reference De Maeseneer, De Prins, Gosset and Heyerick2003; Schellevis et al., Reference Schellevis, Westert and De Bakker2005).

Not all of the PC patients need a medical check-up, regular prescriptions and some consultations are done by practice nurses (Cockburn and Pit, Reference Cockburn and Pit1997). However, ‘nurse practitioners’ are not yet involved in the Hungarian primary care.

In Hungary, smaller surgical procedures are routinely performed in rural or remote GP’s offices, while in cities, GPs usually prefer referring to the surgeons. The available equipment are less advanced than in Nordic countries (Eide et al., Reference Eide, Straand, Björkelund, Kosunen, Thorgeirsson, Vedsted and Rosvold2017).

Most of the professional reasons for encounters are expected to be managed by the GPs. Patients prefer to visit their own GPs because all of their health-related information is available there, while computerised data are not always available in other countries (Lionis et al., Reference Lionis, Papadakis, Tatsi, Bertsias, Duijker, Mekouris, Boerma and Schäfer2017).

Group practices do not yet exist in Hungary. The patient has a right to choose a GP, and GPs are obliged to accept all enrollers in the geographical area they cover. Patients usually visit their own GP in a single-handed practice. Differences in access between different practice models, like in Canada, do not exist in Hungary (Miedema et al., Reference Miedema, Easley, Thompson, Boivin, Aubrey-Bassler, Katz, Hogg, Breton, Francoeur, Wong and Wodchis2016).

In bigger villages and cities, PC offices are easy to approach. Positive behaviour of doctors is well accepted, including consultation’s skills and manner. Like in other countries, majority of patients felt better able to cope with their health-related problem after an appointment with GP, reflecting patients’ enablement (Tolvanen et al., Reference Tolvanen, Koskela, Helminen and Kosunen2017). Regarding communication between doctors and patients, no difference was proved, while it could be better in medium-sized practices (Eide et al., Reference Eide, Straand, Melbye, Rortveit, Hetlevik and Rosvold2016).

Unfortunately, preventive services are not appropriately implemented in the Hungarian primary care; the visits to doctors are mostly caused by chronic morbidities or acute complaints (Sándor et al., Reference Sándor, Kósa, Papp, Fürjes, Kőrösi, Jakovljevic and Ádány2016).

Population expectancy is influenced by national traditions and previous experiences (Janka, Reference Janka2017). Hungarian GPs are managing many social issues, including administrative tasks and for the past 60 years (including decades of Communism) they were considered as the only stable points in the health care, mainly in the years when ‘reforms’ were initiated in the health care system. In the future, more focus needed to person-centred care, to better involvement of patient in decision-making and appropriate delivery of preventative services (Lionis et al., Reference Lionis, Papadakis, Tatsi, Bertsias, Duijker, Mekouris, Boerma and Schäfer2017). Patients require equity, accessibility and good quality of PC services (Oleszczyk et al., Reference Oleszczyk, Krztoń-Królewiecka, Schäfer, Boerma and Windak2017).

Reasons for visits, medical problems to be solved and individual expectations were similar in the recent publications of other participating countries (Eide et al., Reference Eide, Straand, Melbye, Rortveit, Hetlevik and Rosvold2016; Reference Eide, Straand, Björkelund, Kosunen, Thorgeirsson, Vedsted and Rosvold2017; Miedema et al., Reference Miedema, Easley, Thompson, Boivin, Aubrey-Bassler, Katz, Hogg, Breton, Francoeur, Wong and Wodchis2016; Lionis et al., Reference Lionis, Papadakis, Tatsi, Bertsias, Duijker, Mekouris, Boerma and Schäfer2017; Oleszczyk et al., Reference Oleszczyk, Krztoń-Królewiecka, Schäfer, Boerma and Windak2017; Tolvanen et al., Reference Tolvanen, Koskela, Helminen and Kosunen2017). In Hungary and in most of the participating countries, the QUALICOPC study proved a high population satisfaction with the primary health care system (Lionis et al., Reference Lionis, Papadakis, Tatsi, Bertsias, Duijker, Mekouris, Boerma and Schäfer2017; Oleszczyk et al., Reference Oleszczyk, Krztoń-Królewiecka, Schäfer, Boerma and Windak2017; Sanchez-Piedra et al., Reference Sanchez-Piedra, Jaruseviciene, Prado-Galbarro, Liseckiene, Sánchez-Alonso, García-Pérez and Sarria Santamera2017; Tolvanen et al., Reference Tolvanen, Koskela, Helminen and Kosunen2017). We are still waiting for the findings of other countries where the study run.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the participating family physicians who contributed and gave access to their patients. The authors thank them for their expressed opinion and answers and also to the fieldworkers (mainly students of the University of Debrecen) who distributed and collected questionnaires. The authors also thank to Professor Ferenc Antoni (University of Edinburg) for his corrections in English.

Authors’ Contribution

A.N. literature search, analysis of data, text writing, T.U. data processing and analysis, K.L.R. study coordination, literature search, S.H., Z.J. and C.S. literature search, C.M., L.M., P.S., J.S., P.T. and M.V. data collection, local or regional network organisation, L.I.L. fieldwork organisation I.R. study design, literature search, text writing and final editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Commission Framework 7 Programme, EU FP7-Health 242141 QUALICOPC Evaluating Primary Care in Europe.