Introduction

Primary care is the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained relationship with patients and practising in the context of the family and community (Donaldson et al., Reference Donaldson, Yordy and Lohr1996). By virtue of its broad-based, frontline and holistic outlook, primary care is essential for the success and sustainability of any health care system. Family doctors form an important component of the primary health care team. In one study, ten industrialized countries were compared, on the basis of the primary health care system, 12 health indicators and population satisfaction, with overall costs of the systems. A general concordance was found among these three characteristics, highlighting the importance and impact of primary health care on health indicators and the costs of health care (Starfield, Reference Starfield1991). Despite such evidence, the future of primary care continues to be subject to debate (Sox, Reference Sox2003). Among the consequences of this internationally are recruitment problems, which aggravate shortages of primary care physicians despite increased demand.

Health care systems are comprised of all the people, structures, processes and actions, the primary purpose of which is to promote, protect, restore, maintain and improve the health of the population (World Bank, 1993). Changes in health care systems pose challenges for health care professionals. Family doctors need to be aware of the potential changes in health care systems for them to optimize patient care and develop plans to meet these challenges.

Collaborative enquiry

At the meeting of the International Federation for Primary Care Research Networks (IFPCRN) held at Orlando, Florida, USA, in October 2004, a decision was made to conduct a collaborative enquiry (Bray et al., Reference Bray, Lee, Smith and Lyle2000) on the present status and future role of family doctors among the network members. Following discussions, the three lead authors developed six questions to structure the enquiry:

1. How is primary care delivered in your country? How is it funded? What are the problems?

2. What is the role of family doctors in the delivery of primary care? How is their care integrated with care by others (quacks, traditional healers, sub-specialists)?

3. How will the system and needs of the population change within the next 10 years?

4. How can family doctors and organized family medicine help to meet these changing needs?

5. What challenges will this pose for family doctors and organized family medicine?

6. How can these challenges best be met through system change, education and research? What resources will this require?

We used the IFPCRN membership list to invite members to participate as contributors from their country or region. Thirty-seven participants from 23 countries contributed to the enquiry. The six questions were sent electronically to the participants. They were asked to provide information from their region, restricted to one page and within a specified period. The responses were reviewed on submission and integrated by the authors into a single manuscript in line with the study objectives. The lead authors verified the submitted information. More than one contributor was recruited from some regions/countries to help ensure accuracy of information provided. The contributors reviewed the draft before the paper was finalized. Country- and region-specific information provide examples of the broad range of issues identified.

Findings

The 37 participants were from 23 countries. Table 1 provides basic information on each of these countries. Table 1 illustrates the wide variation in health indicators across the participating countries. For example, life expectancy for men is 46 years in Nigeria compared with 78 years in Australia (World Health Organization, 2006).

The responses from the participants were grouped under a number of themes. Information under these themes is presented below with reference to the supporting literature.

Question 1. Present status of primary care

Delivery of primary care

Developed and functional structures for the delivery of primary care exist in several countries, eg, the United Kingdom (UK) and the Netherlands. In contrast, India and Pakistan have relatively well-organized but poorly functional primary health care systems. In Portugal, health services with primary care orientation exist but lack human resources (Biscaia et al., Reference Biscaia, Martins, Carreira, Fronteira, Antunes and Ferrinho2006).

Family doctors often practice solo or in small groups (Bindman and Majeed, Reference Bindman and Majeed2003). In the United States of America (USA), the corporate delivery of medical care plays a larger role. Other specialists provide primary care in several countries including Brazil and Hong Kong (The Harvard Team, 1999; Brasil, Ministério da Saúde, 2002) with alternative medical practitioners also practising primary care in many countries including Pakistan and Hong Kong (The Harvard Team, 1999).

Funding of primary care

In the UK, 80% of the revenue for the National Health Service (which includes funds for primary care) is raised from taxation. In the USA funding is 55% through private sources, mostly insurance. Government-supported insurance coverage is offered in Thailand (Towse et al., Reference Towse, Mills and Tangcharoensathien2004). In Nigeria, voluntary organizations play a large role since public funding is insufficient. An increasing out-of-pocket expenditure for health care is seen in Israel. The establishment of a general health insurance in Turkey will unify all official insurances. Lavish funding does not guarantee results. In the USA, which has the highest per-capita expenditures in the world (US$5711 in 2003), the life expectancy at birth is 77.3 years, which ranks it 23rd in the world (World Health Organization, 2006).

Problems in primary care

Quality is a problem

Evidence-based practice is poorly implemented even in developed counties (Ebell and Frame, Reference Ebell and Frame2001). Nearly 45% of Americans do not receive care meeting established standards (McGlynn et al., Reference McGlynn, Asch, Adams, Keesey, Hicks and DeCristofaro2003). Quality assurance in primary care is in its infancy (Lionis et al., Reference Lionis, Tsiraki, Bardis and Philalithis2004) but there is more emphasis on quality outcomes (Abyad et al., Reference Abyad, Al-Baho, Unluoglu, Tarawneh and Al Hilfy2007). The practice of evidence-based medicine is the norm in several countries including the USA, while Kazakhstan and Turkey are moving towards it (Nugmanova, 2003; Tani ve Tedavi Rehberi, 2003).

Policy and support

Policy changes relative to health care systems are made with little input from family doctors (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Ferrier, Woodward and Brown2001). Primary care is a priority in the national health policy of many countries, but often only on paper (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Okorafor and Mbatsha2005). For example, it was reported that the Federal Mental Health Authority in Pakistan implements health policies, but does not have representation from family doctors, who provide care to most patients with psychiatric disorders (Mental Health Ordinance for Pakistan, 2001).

In Turkey, the health system is based on a centralised national policy and structure but decentralization is anticipated. Family physicians impact policy and planning of primary care services through the General Directory of Basic Health Services. In Kazakhstan, the government mandates referral to specialists for many problems (National Program of Health Sector Reform and Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2005–2010, 2004). In Brazil, multiple uncoordinated gates exist for the patient to enter the health care delivery system (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Costa, Busnello and Rodrigues1999).

Governments often spend funds on hospital services at the expense of primary care, making it easier for people to seek treatment from hospitals (Branco and Ramos, Reference Branco and Ramos2001). Reimbursement for primary care is often less than that for other specialized medical care (Woolf, Reference Woolf2007). However, in some countries a reversal in this trend has been seen as in Thailand (Towse et al., Reference Towse, Mills and Tangcharoensathien2004).

Education and workforce development

Family doctors lack education and continuous professional development (CPD) opportunities in several countries (Yaman, Reference Yaman2002a; Reference Yaman2002b). In the USA, too few medical graduates select family medicine despite the country having good graduate programmes (Mackean and Gutkin, Reference Mackean and Gutkin2003). Family doctors are poorly distributed, most of them working in more affluent urban areas (Ransome et al., Reference Ransome Kuti, Sorungbe, Oyegbite and Bamisaiye1988), while in the Philippines they are retraining as nurses to secure jobs in developed countries (Choo, Reference Choo2003). The involvement of family doctors in administrative tasks takes them away from clinical services exacerbating problems. The high number of patient visits and aging patients with multiple problems results in a heavy burden on the health care system (Iversen et al., Reference Iversen, Farmer and Hannaford2002). In some countries the family doctor shortage is leading to overworked physicians, difficult access to care and longer waiting times (College of Family Physicians of Canada, 2004). In other countries HIV infection poses a serious challenge to health systems and hence sustainable development (Federal Ministry of Health, 2003).

Research in primary care

There is limited support for primary care research. The need for research in primary care is crucial, and developing the ability of family doctors to conduct it requires support (Beasley et al., Reference Beasley, Starfield, van Weel, Rosser and Haq2007).

Question 2. The role of family doctors in primary care and integration with other health care providers (alternative practitioners, traditional healers, sub-specialists)

The role of family doctors and the degree of coordination and integration with other health care providers is quite variable across different countries.

In most countries, family doctors provide only outpatient care but in, for example, the USA and Canada, they often provide inpatient care, intensive care, maternity care and emergency care services. The provision of palliative care including home-based care is a function of family doctors in several countries including Australia and the UK (Grande et al., Reference Grande, Farquhar, Barclay and Todd2004; Hiramanek and McAvoy, Reference Hiramanek and McAvoy2005).

In the UK, family doctors are first-contact physicians for individuals and families. Their role includes prevention, clinical diagnosis, treatment and the coordination of care with medical and social services. They act as a gateway for hospital care, with some exceptions such as direct access to accident and emergency, genitourinary medicine and family planning services. In general, family doctors are skilled community-based clinicians serving as a resource to a defined practice population with strong emphasis on doctor–patient relationships. They work closely with the community nurses, nurse practitioners and social workers.

The coordination of patient care between family doctors and other specialists needs improvement in many countries. A low referral rate may reflect either the effectiveness of the family doctors or reluctance to refer for fear of losing patients (Munro et al., Reference Munro, Lewis and Lam1991). In those countries where family doctors work closely with other specialists, the relationship is generally positive and constructive as in the USA (Berenson, Reference Berenson2005). In Pakistan, the Philippines and Hong Kong, respondents commented that family doctors lack working relationships with other specialists and patients are usually referred with reluctance.

The integration of alternative medical practitioners with family doctors is uncommon despite the frequent use of their services by patients (Ness et al., Reference Ness, Cirillo, Weir, Nisly and Wallace2005). Delay in seeking modern medical care has been attributed to alternative medical practitioners, resulting in adverse outcomes (Malik and Gopalan, Reference Malik and Gopalan2003). In the Philippines it was reported that patients seek treatment from alternative medical practitioners when modern medical care fails to offer cure. Some of the alternative therapies are considered dangerous and constitute modern day quackery (Magee, Reference Magee2002) but access to safe complimentary medical therapies is increasingly taking place through family doctors (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Nicholl and Fall2001).

Traditional birth attendants carry out the majority of deliveries in rural areas of Pakistan, but they are not integrated with other health care professionals (Safdar et al., Reference Safdar, Inam, Omair and Ahmed2002). Some steps are being taken to improve this situation (Fatmi et al., Reference Fatmi, Gulzar and Kazi2005). In rural Thailand, the shortage of family doctors has been partly compensated by provision of services by trained village health volunteers, midwives, sanitarians and nurse practitioners.

Question 3. Anticipated changes in the health care systems and population needs in the next decade

The conclusion from the respondents was that if no major initiatives are undertaken, the status of family doctors is unlikely to improve and government support for hospital care at the expense of primary care is likely to continue. New initiatives could contribute to increasing the recognition of the value of primary care for the health of populations.

Shortages of family doctors are likely to become worse, particularly in rural areas. Younger graduates (who include a higher proportion of women) are working fewer hours and providing a narrower range of services than their older colleagues (National Physician Survey, Canada, 2004). The growing population will put more pressure on health services, and the increase in the elderly population will pose special problems because of the number of co-morbidities and the complexity of problems (Anderson and Chu, Reference Anderson and Chu2007). The availability of diverse medical treatments is likely to increase the complexity of treating patient problems. Family doctors already manage multiple problems at each visit (Beasley et al., Reference Beasley, Hankey, Erickson, Stange, Mundt and Elliott2004) and the pressure for this is likely to increase worldwide.

Lifestyle changes will increase the prevalence of obesity and its consequent morbidities. The increasing cost of medical interventions may require rationing (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2001). The shift of hospital care to ambulatory settings will require a greater partnership with patients and their families and community resources. The appointment of specialist general practitioners in the UK to provide specialized community clinics for a cluster of practices is a debatable development. The advancement of information technology (eg, the Internet) will enable patients to participate more in their own care but may also raise patient expectations.

Increasing affluence in many areas will enable patients to visit other specialists for primary care problems, while increasing poverty in others will make the provision of even essential services a challenging task (Karkee et al., Reference Karkee, Tamang, Gurung, Mishra, Banez-Ockelford and Saunders2005).

The recognition of the need for, and the establishment of, formal training programmes for family doctors are likely to continue. The enforcement of certification/re-certification, CPD and quality improvement strategies will favourably impact on the prestige of family doctors.

The view was expressed that the financial support for primary care is unlikely to increase. The linking of payments to quality in relation to disease management in the USA and the UK is likely to spread to other countries. Non-governmental funding is likely to play a larger role in future in many countries, including developed western countries.

Questions 4, 5 and 6. Anticipated challenges and proposed actions for family doctors and organized family medicine

A. Service provision: address quality and related issues

Ensure audit and quality assurance

The principles and practice of continuous quality improvement should be fully enforced in primary care settings. Such activities should be transparent to enhance credibility.

Promote group practices

A move towards group practice will increase efficiency and improve patient care through collaboration and mutual learning, providing more time for CPD activities, teaching and research and reduce burnout among family doctors. Group practices involving other specialists will promote effective working relationships.

Promote multidisciplinary teams

Multidisciplinary teams that include nurses and pharmacists can provide a range of improved services while reducing family doctors’ workloads and should be promoted.

Incorporate information technology into practice

Information technology is becoming easier to use, powerful, less expensive and more readily available. Patient–physician email, remote monitoring and telemedicine consultation are opportunities available to family doctors (Heinzelmann et al., Reference Heinzelmann, Lugn and Kvedar2005). Information and communication technology (ICT) can serve as a tool to improve the delivery of primary health care, through ‘e-Health’. ICT includes patient and clinician communication, medical records, decision support and knowledge-based management (Ebell and Frame, Reference Ebell and Frame2001). There are concerns about time, cost, patient privacy, lack of reimbursement, liability, technology interoperability and disruption of the patient–physician relationship, reliability of online information and a lack of evidence for benefit (Bodenheimer and Grumbach, Reference Bodenheimer and Grumbach2003).

Ensure appropriate coordination of patient care

Other specialists need to recognize their role in supporting, not supplanting, primary care and developing a well-functioning referral system must be a priority for family doctors (Qidwai and Maqbool, Reference Qidwai and Maqbool2005). The family doctor should be the focal point for health care in the community (Souliotis and Lionis, Reference Souliotis and Lionis2004).

Ensure an ethical relationship with industry

Industry is a powerful stakeholder in health care and family doctors should develop a fruitful and ethical relationship. Conflicts of interest must be minimized and made transparent. Family doctors should participate in research and development activities with the industry.

B. Education: improve education and continuing professional development

Expand and improve academic education for family doctors

Future family doctors must address both the preventive and the curative needs of patients (Buchan and Dal Poz, Reference Buchan and Dal Poz2002). The training of family doctors should be by academic family physicians and conducted in both academic and community settings. A critical mass of academic family doctors is required. National and international collaboration in education and research should be promoted.

Promote CPD

Family doctors will have to keep up to date through CPD programmes (Yaman, Reference Yaman2002b). Electronic means of dissemination may be useful as exemplified by the World Organization of Family Doctors (Wonca) Website (Global family doctor, 2006).

Develop support for primary care in academic institutions

Academic institutions support the training and research of hospital specialists at the expense of primary care education and research. The ratio of academic to service practitioners in academic departments of family medicine should be increased and interaction with and support for family doctors in the community should be developed.

C. Research: develop a robust research enterprise among family doctors

Promote primary care research

Resources are needed to evaluate health services and health care outcomes to provide the most beneficial and cost-effective treatments. These projects can be facilitated in part by primary care research networks. A need exists in family medicine for more emphasis on research, and funding for research and journals for research publication, including a need to change the research culture (Weel and Rosser, Reference Weel and Rosser2004; Beasley et al., Reference Beasley, Starfield, van Weel, Rosser and Haq2007). Evidence-based practice guidelines should be based on research conducted in primary care settings.

D. Improve support for family doctors

Promote adaptability and flexibility among family doctors

Family doctors will be required to adjust to the organizational changes and demographic shifts (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Avant, Bowman, Bucholtz, Dickinson and Evans2004). They should adopt funding models that promote cost-effective management of chronic conditions, focus on the care needed by communities and avoid practices that primarily generate income.

Improve the status of family doctors

Vocational training in family practice, certification, CPD and re-certification will help improve the status of family doctors. Enhanced respect for family medicine will increase medical student interest in the specialty (Yaris and Dikici, 2004). Recognition should be sought for family doctors as the critical component of primary health care (College of Family Physicians of Canada, 2004). We need to study how stakeholders perceive family doctors and implement strategies to improve a family doctor’s status (Abyad, Reference Abyad1996).

Gain support of policy makers for primary care

Family doctors and their organizations should seek policy makers’ support for primary care by demonstrating the value of their services in health care delivery. The remuneration for family doctors must be similar to that of other specialists.

Promote public education

Family medicine is a new specialty in several countries (Nugmanova, 2002). The public needs to be educated about the role of family doctors and how to utilize their services.

Help prevent burnout

Organized family medicine should find ways to improve family doctors’ well-being and to prevent burnout (Yaman and Ungan, Reference Yaman and Ungan2002).

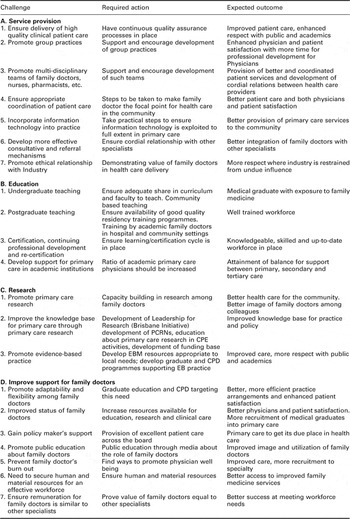

Table 2 lists the anticipated challenges, actions required and expected outcomes for future family doctors.

Table 2 Anticipated Challenges, Required Actions and Expected Outcomes for future family doctors

PCRN: Primary Care Research Network; CPD: continuous professional development; EBM: evidence-based medicine; EB: evidence-based.

Discussion and conclusions

This collaborative enquiry drew on the knowledge and experiences of the members of the IFPCRN. It is therefore limited by its use of a convenience sample, based largely on the opinions of contributors, limiting any claim to generalize the findings and recommendations. This exploration has highlighted, through responses to six key questions, several issues and potential solutions that appear to be relatively consistent across the responding countries and regions, although the specifics in terms of health care systems and role of family doctors vary widely.

Common problems relating to delivery systems, funding and policy, lack of evidence-based medical practice, education and research have been identified. There is a wide variability in the role of family doctors across countries and regions, often with poor interaction with other caregivers. Despite an anticipated expansion of the family doctor model, shortages of family doctors are expected, despite an increase in the health care needs of populations.

The foremost anticipated challenge includes addressing quality issues. This requires regular audit and quality assurance initiatives, promoting adaptability, group practices and teamwork, coordinating care, incorporating information technology into practice and ensuring ethical relationships with the industry. These measures can promote the delivery of high-quality services to the community.

Providing excellent patient care is essential for improving the status and support for family doctors. Achieving this requires continuing engagement with policy makers, academic institutions and the public. Improved education and continuing professional development opportunities are required as are measures to prevent burnout and retain the workforce. Research in primary care is fundamental to the development of relevant guidelines and to promote evidence-based medical practice.

In conclusion, it is the provision of high-quality competitive services that will ensure proper realization and utilization of the potential of family medicine to resolve common health problems at the community level. The recommended actions summarize the steps that are necessary to move the specialty forward in the coming decade.

List of contributors

A. Abyad, General authority for health services for the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; Tariq Aziz, Pakistan Society of Family Physicians, Pakistan; Isabela Benseñor, University of São Paulo, Brazil; Aya Biderman, Ben Gurion University, Beer Sheva, Israel; André Biscaia, Board of AGO, Portugal; Manzoor A. Butt, Family Physician, Rawalpindi, Pakistan; James A. Dickinson, University of Calgary, Canada; Mustafa Fevzi Dikici, Ondokuz Mayis University School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, Samsun, Turkey; Tamer Edirne, Family Physician, Turkey; Paulo Ferrinho, Instituto de Higiene e Medicina Tropical, Portugal; Susan T. Go, Family Physician, Philippines; Gustavo Gusso, University of São Paulo, Brazil; Paul Heinzelmann, Harvard Medical School, USA; Chris Hogan, Victorian Faculty, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Australia; Victor Inem, Lagos University Hospital and the Institute of Child Health and Primary Care College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Nigeria; Cindy L. K. Lam, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; Christos Lionis, School of Medicine University of Crete, Greece; Manfred Maier, Medical University of Vienna, Austria; Donna P. Manca, University of Alberta, Canada; Priyesh R. Modi, Family Physician, Bharuch, Gujarat, India; Mohamed Farouk Allam, Ain Shams University Cairo, Egypt; Mabel N. Nangami, School of Public Health, Moi University, Kenya; Azhar E. Nugmanova, Almaty Postgraduate Institute for Physicians, Kazakhstan; Maeve O’Beirne, University of Calgary, Canada; Peter Nyarang’o Orotta, School of Medicine, Asmara, Eritrea; Riaz Qureshi, Aga Khan University, Pakistan; Shvartzman Pessach, Ben Gurion University, Beer Sheva, Israel, Paula Silva Family Doctor, Portugal; Helen Smith, University of Brighton, Brighton, United Kingdom; Sung Sunwoo, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Songpa-gu, Seoul, Korea; Mehmet Ungan, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey; William Cayley, Faculty Community-based Family Medicine Residency, Rural Wisconsin, USA; Hakan Yaman, University of Akdeniz, Turkey; Fusun Yaris, Ondokuz Mayis University School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, Samsun, Turkey.

Note: In this paper the term family doctor is used as an inclusive term to include general practitioners and family physicians.

A summary of the paper was presented at the First Annual International Primary Health Care Conference, Emirate of Abu Dhabi, held in January 2006 at Abu Dhabi.