Salina, Kansas – small-town America. 1993. I’m in seventh grade, and kids all across town are walking out of school, marching down Main Street to city hall in protest of local government’s failure to fund public schools. In the United States, forty years of defunding public education has cultural consequences. Twenty years of defunding the humanities has consequences. American citizens have received less training in the arts of interpretation at a time when life – namely the internet – gives individuals an information overload every day. Scholars writing for public venues return education to the people that government has taken it away from.

Flash forward a bit: I had some dark days in my teen years. I didn’t fully process them until twenty years later when I wrote a piece called “Hamlet Is a Suicide Text – It’s Time to Teach It Like One.”Footnote 1 Public writing can bring our academic work back to the very human experiences and questions that brought us to academia in the first place.

In college, I fell in love with John Milton’s poetry. When teaching now, I start my Milton classes with a close reading of the first epic simile in Paradise Lost – which compares Satan to a sleeping whale that a sailor has anchored his skiff to, thinking it’s an island, and then the whale wakes up and goes plunging down, dragging the sailor along. I didn’t expect this classroom activity to become an essay unprovocatively titled “Trump is Satan.”Footnote 2 Public writing allows us to find the personal and the political in the academic work we do.

1. Public writing: From why-to to how-to

Public writing for mainstream newspapers, magazines, and websites makes the world of ideas accessible to people outside the hallowed halls of higher education – how dare you. It disrobes the habits of academic writing and respects the skills of the journalist who can turn complexity into clarity for non-specialist readers. It takes many forms – from the 800-word op-ed in a local newspaper to the 3,000-word feature story in a national magazine, from the short-form listicle to the long-form blogpost, from the timely intervention where research-backed expertise provides informed commentary on an unfolding news story to the timeless think piece that’s a quick hit of intellectual thought for someone’s morning coffee or commute.Footnote 3

Public writing is scholarship for the folks we grew up with.

People are hungry for knowledge. Most live busy lives outside the academic circuits of knowledge production. Public writing creates opportunities for education – both general education for readers who aren’t specialists on a topic and continuing education for people who aren’t in school anymore.

The value proposition of public writing has skyrocketed in recent years as scholars have helped societies around the world interpret the use and abuse of political power. It soars higher every time people find a little relief from the onslaught of awfulness in the joys of reading, thinking, and talking about human creativity in all its diversity.

Beyond service to society, two reasons to do public writing stand out. First, at a time when education is under attack, public writing is one of the best ways to demonstrate – to show not tell – the social value of scholarly work. Second, from the perspective of pure self-interest, public writing makes you a better scholar – a better thinker, writer, researcher, and teacher who can convey knowledge with maximum impact.

Society’s longing for knowledge does not disappear even if, somewhere along the way, scholars cloistered on their campuses have become complacently detached from the worlds they study. It doesn’t disappear when governments defund the humanities. Admittedly, for professors, there’s a structural incentive system – tenure – discouraging junior scholars from public writing.Footnote 4 Yet these recent trends have created a rift between people looking for knowledge and scholars ready to serve at a time when the interpretation of human activity has never been more urgent. That’s why writer Devoney Looser has called for “a new academic normal in which virtually every piece of scholar-facing humanities work generates a public-facing writing component.”Footnote 5

But how to do public writing is a mystery. You learn through trial and error. No one ever teaches you. And fear of the unknown prevents scholars from public writing.

2. Calibrating for public writing

Many academics have had the experience of reading an article about their area of expertise in a major national venue that gets things about half-right. It’s usually a journalist (who knows how to do public writing) dipping into content that they are not deeply familiar with. Academics can and should defend the integrity of their fields; those same academics should also learn the journalist’s skills of mass media communication. Public writing works best when subject-matter experts do it themselves.

Public writing must come in addition to – not in place of – our academic work. The strength of our public writing depends on the strength of the academic work it grows from.Footnote 6

If you don’t want to do public writing, that’s fine. No worries. It’s not for everyone. No one is going to force you. But don’t get in our way. You need us, even if you hate us, mock us, critique us – just as those of us interested in public writing desperately need the scholarly work of people who aren’t.

The only way to do public writing successfully is to stop worrying if your colleagues think you’re smart enough. Public writing is not for scholars. I don’t try to please my retired fire-fighter father-in-law when writing for Shakespeare Quarterly.

Public writing isn’t financially profitable, but it will be rewarding for you and your communities emotionally. Public writing is how people in your support system – friends and family – can access and engage with your intellectual work.

Don’t make the mistake of thinking that public writing is easier than academic writing. Successfully conveying an important idea in 800 words to an audience that has no specialized training is much more difficult than having 9,000 words for colleagues who hold the same PhD as you.Footnote 7

3. Ten style tips for public writing

-

1. Humor is an important route into education for public audiences. Embrace the absurd. Foreground the comical. Give the cool, quirky evidence. If there’s something in your research that is wild and hilarious, get that in your public piece, even if it’s not central to the issue.

-

2. Make it jokey. But not hokey. Don’t try to make jokes if you’re not funny.

-

3. Use lists, metaphors, analogies, memes, and other creative gestures.

-

4. It’s OK to write in the first person. Ask how your own story and experiences relate to your material.

-

5. Write with joy. We’re all desperate for happiness. How can your article offer a corner of delight in a weary world? Public readers love a feel-good story, and your enthusiasm for the importance of your topic will be contagious.

-

6. Rain down fury on the forces of badness in the world, if needed. Call them out. Put them on blast. But be prepared for anyone you discuss to read your article and, if they’re unhappy, send a sharply worded letter. Don’t cower from speaking the truth, but make sure you are accurately representing people and their ideas.

-

7. Make sentences snappy and short.

-

8. Chunk your article into sections. Titles and headings should be short and punchy: no colons and no more than eight words.

-

9. Write with confidence. This is your research. You know it forwards and backwards, and your audience doesn’t. You don’t need to argue a position (persuade someone to accept it). You simply need to educate someone (convey knowledge that you have but they don’t).

-

10. Content is king. Without content, style is just fluff. The standard length for op-eds and much other public writing is 800–1,000 words, which is about three double-spaced pages. Your goal is to pack as much content as possible into that space. No wasted words, no repetition, and no mercy in editing your sentences to get to the point.

4. What not to do in public writing

Don’t start a public writing project until you’ve got some clearly defined knowledge that your audience doesn’t have. Start with a completed or developed research project – it might be a book, article, or conference presentation (if you’re a professor) or a term paper or presentation (if you’re a student). Often the occasion for public writing is some unfolding news story that can be illuminated by your long-established expertise. The challenge then becomes how to re-package your academic knowledge to be accessible to someone outside your field and to be applicable to current events.

You won’t have space for academic meta-discourse – e.g., a text statement (“This essay explores…”) or a flag for the thesis (“In this essay, I argue that…”). Cut the chatter; keep the substance.

You’ll probably leave out any “literature review” where you discuss previous scholarship in the field – though there are some exceptions, especially if you’re making an intervention in a field. If so, you might only have about four sentences to map the terrain of the field, provide key quotations, and carve out your intervention.

You probably won’t include citations with full bibliographic information. Often, online writing uses hyperlinking to cite sources and further reading.

Throughout your essay, you won’t have much space for quotations, so select quotes wisely, and summarize the rest in your own words. There’s also not much room for analysis. Keep the focus on your amazing evidence and the idea that holds it all together. Trim back the analysis. Thesis, evidence, and what’s at stake – that’s what matters most in public writing.

5. Structuring public writing

Structurally, plan to spend about 20% of your essay on the introduction, 70% on the body, and 10% on the conclusion. You can develop a cap-and-trade system (e.g., take 10% from the body for the conclusion). Keep in mind that your first paragraph(s) will be the most read, the last paragraph(s) the least. Structure where you put what’s most important accordingly.

5.1 Introduction

In the introduction, consider what journalists call “pegging” your argument to something happening now: an upcoming event, recent headline, current controversy, anniversary, the yearly holiday cycle, and so forth. It may be a smaller story that’s made the rounds in the past week, a larger story that’s been in the news for a month, or an ongoing issue that keeps showing up year after year.

Try to start with something shocking or surprising: some amazing statistic(s), a cool quotation, or a funny anecdote. Or start with your thesis as the first sentence. You need a thesis statement within the first three paragraphs. And those should be very short paragraphs: two or three sentences each. Your thesis should be tweetable: that means 280 characters or less, which equals about 25 words.

In public writing, introductions tend to follow one of three possible structures:

-

1. The Cannonball: Give the thesis immediately at the start of the article.

-

– Paragraph 1 (3 Sentences): Peg, Thesis

-

– Paragraph 2 (2 Sentences): Orientation, What’s at Stake

-

-

2. The Exemplar: Start with some stunning evidence or a vivid scene; then comes the thesis.

-

– Paragraph 1 (3 Sentences): Stunning Evidence or Vivid Scene

-

– Paragraph 2 (3 Sentences): Thesis and What’s at Stake

-

-

3. The Q&A: Develop a driving question in the first paragraph and answer it in the second.

-

– Paragraph 1 (4 Sentences): Peg, Orientation, Evidence, Analysis, Question/Problem

-

– Paragraph 2 (2 Sentences): Thesis and What’s at Stake

-

Note that editors love The Cannonball.

5.2 Body

Apart from your thesis, what matters most in public writing is evidence and what’s at stake. Your piece will succeed or fail based on the quality and density of the evidence: the more specific the better. Amazing statistics, captivating stories, and quotes that stop readers in their tracks to say, Wow! That’s what public writing is all about.

Here’s the most important tip in this entire how-to: Don’t make an argument; tell a story. The way you tell the story should make your argument for you. Illustrate – rather than argue – your points.

The story you’re telling should structure the body of your article. Here’s a four-step process for planning out the structure of the body of an essay:

-

1. Define the Details: Identify five pieces of key evidence. These may be amazing statistics, great quotations, bizarre facts, unknown texts, and so forth. The more specific the better. Anything wild that will make your readers say, Wow!

-

2. Find the Story: Identify what story you’re telling (“This is the story of …”). Who are the main characters? What is the central conflict? Who’s the hero? The villain? Break the story down into parts. It may be three parts: Beginning, Middle, and End. It may be more, using Freytag’s Pyramid: Exposition, Inciting Incident, Rising Action, Crisis, Climax, Falling Action, and Denouement.

-

3. Place the Details: Figure out where in this story – chronologically – each of those key pieces of evidence that you identified should appear. The goal is to use those captivating details to texture the overarching narrative.

-

4. Write the Story: Write out the body of the article – the story – moving from start to finish. Paragraphs should be short (three to six sentences each). You’ll probably want to chunk out sections with short headings (no more than eight words, no colons).

5.3 Conclusion

With respect to what’s at stake – meaning the bigger picture that you gesture toward in your introduction and address in full in your conclusion – be ambitious in connecting the details of your argument to life today. You can go personal or political if you like, but that is not the only way to have big implications. It’s possible to remain in an analytical register (I prefer it), asking how your central idea brings us to understand our world differently, in contrast to obnoxious moralizing.Footnote 8

Some questions to consider for a conclusion include:

-

1. What are the policy implications that follow – what practices or rules should be adopted and by whom?

-

2. Are there common misconceptions that your argument challenges?

-

3. How does your argument illuminate the tradition to which your topic belongs?

-

4. What are the lingering questions that need further thought or research?

-

5. Are you able to theorize outward – to create a model that explains evidence you haven’t analyzed in depth?

-

6. Does your argument allow you to predict the future (if so, what is likely to happen)?

The key to writing a good conclusion: don’t try to do it all. Pick one strategy and develop that idea in depth.

6. Editing public writing

On the paragraph level:

-

– Reduce the number of quotations: Summarize in your own words or just cut.

-

– Reduce the length of quotations: Just include the key words, not whole sentences.

-

– Reduce the amount of analysis: Cut the thinking out loud to get to the takeaway.

-

– Eliminate repetition: Cut sentences that say the same thing in different ways.

-

– Remove tangents and digressions: They may be interesting but aren’t needed.

-

– Remove ancillary ideas and information: Interesting, not needed.

On the sentence level:

-

– Shorten long, flowery sentences into simple snappy statements.

-

– Remove adjectives: They distract from substantive nouns.

-

– Remove adverbs: They frequently distract from nouns and verbs.

-

– Remove qualifying phrases: Indeed, they often draw attention away from the substance of your sentences.

-

– Reduce nominalizations: The use of verbs should be done as an indication of action. Use verbs to indicate action.

-

– Cut meta-discourse: For example, when we look at academic writing, we see that it often buries substantive information in meaningless prose.

-

– Trim transitions: Writers want to use them; in contrast, readers don’t need them.Footnote 9

7. Submitting public writing

Most public writing gets published because a writer has some sort of established relationship with a venue or editor. Do you have any relationships? If so, that’s the first place to submit to.

Have you published multiple award-winning books and essays? Do you have 250,000 followers on social media? If not, then avoid major national venues like The New York Times and The Atlantic. These venues publish people who bring an audience along with them. Or they look for someone with personal involvement in national news.

Look for the tightest fit between what your essay is about and the topics that a venue covers. Seriously consider local venues: hometown newspapers, outlets at your college, and so forth.Footnote 10

Most venues have instructions for submissions on their websites.Footnote 11 Look for a “Submissions” or “Contact” page. But know that impersonal submission portals are where good ideas go to die. You’ll be much more successful sending your piece to someone’s personal email, which may be listed on the venue’s “Masthead” or “About Us” page or may require some internet sleuthing to find. Submissions to editors’ personal emails (where a person with decision-making power will read your pitch and often respond quickly) are more successful than submissions to depersonalized online portals (where the decision-making process is vague and lengthy), but submissions to online portals (where there is at least a formal system in place for receiving, tracking, and responding to submissions) are more successful than submissions to depersonalized email portals (where complete silence is the most common response to submissions).

To create a submission plan, make a list of possible venues. Then order that list according to where you most want to see your essay appear. Submit your essay to your first choice. If they don’t respond (which is what happens 85% of the time) or pass on your essay (10% of the time), then just move on to the next one on your list. You’ll need to have thick skin. It is not uncommon for articles to be submitted unsuccessfully to several – if not dozens of – venues before finding the right home.Footnote 12

But also be prepared for the response to be: “Great: it will be live on our website in an hour.” Oh crap, I thought the first time I got this. I’m used to nine months of revise-and-resubmit. Only send out writing that you’re confident in and would be proud to have your name attached to.

Brace yourself for line editing and fact-checking, which are more microscopic at the sentence level than in academic writing: the more prominent the venue, the more rigorous the editing will be. That’s a good thing. It’s much better to catch mistakes prior to publication than afterward. And venues that can pay editors for extensive fact-checking can also pay for marketing that ensures a wide readership for your article.

In a recent article, I included a few paragraphs about my daughter performing in a play. The editor cut those paragraphs: those were good edits that nicely kept the discussion focused, but talk about killing your darlings.

With public writing, editors often re-title your piece (to include keywords that exploit search engine optimization). They often pick the worst title imaginable.

Working with editors is an art. They will try to radically condense length, and often those edits are for the better. Sometimes they will simplify ideas to the point of changing the meaning of what you’ve said, and it’s important to hold your ground in the face of bad edits. It is perfectly reasonable to withdraw a piece from consideration if you and the editor cannot agree on a vision. These are your ideas, and you’ve got to protect them.

8. Celebrating public writing

Publication day should be a celebration. Treat yourself to something special to mark the moment. Send your published pieces to family and friends, who will want to celebrate you.Footnote 13

Writers get queasy around promoting their writing. Jeffrey J. Williams chides “the promotional intellectual.”Footnote 14 Setting aside how darling it is for a tenured professor with job security at a prestigious institution to tell precariously employed junior scholars trying to build careers and put food on their tables to adopt the cool indifference of a bygone era’s academics (under whose watch the current jobs crisis in academia came about), it is fundamentally wrong to view the purpose of promotion as self-aggrandizement. It’s not about you. Promotion is about creating avenues of access to knowledge for people who, unlike you, might not live every day in the world of ideas. If you center other people’s hunger for knowledge rather than your own desperate need to look cool to your colleagues, promoting your writing becomes less fraught.

Rolling up your sleeves to do the work of community building through marketing and media relations is central to public humanities. Doing the work of spreading the word shifts you from the sage on the stage who says, Here’s an idea – you’re welcome, to the public intellectual who is actually interested in making education more accessible for more people in more places and at different ages and stages of life.

If you work for an organization that employs people with titles like “Director of Marketing” or “Public Relations Manager,” tell them about your public writing. They may help promote your piece because you are making your employer look good (unless you’re pointing out how awful your employer has been, which is an excellent use of public writing).

Remember that comment sections are not where good intellectual discussions happen: expect the worst, smile, ignore, and move on. Getting hate mail is often unintentionally hilarious. Getting death threats is not funny at all, but it does happen. The risks of public writing are real, but the risks of silencing ourselves are much greater.Footnote 15

One joy of public writing, which I didn’t see coming, is having talented people make art based on your ideas (Figures 1– 3).

Figure 1. Artwork by Mark Shaver for Jeffrey R. Wilson, “Why I Write on My Mobile Phone” (2015).

Figure 2. Artwork by Isabella Akhtarshenas for Jeffrey R. Wilson, “Something Is Rotten in the United States of America: Mass Shootings as Tragedy” (2015).

Figure 3. Artwork by Bruce Gore for Jeffrey R. Wilson, Shakespeare and Trump (2020).

Author contributions

Writing – original draft: J.R.W.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Appendix A: Sample outlines for public writing

The cannonball

In this outline, the first sentence – a definition of the humanities – is the thesis statement. That one sentence is the entirety of the first paragraph and the whole introduction. The body of the essay moves through an enumerated list of five alternate definitions of the humanities and then defines the sciences to set up an elaborated definition of the humanities at the start of the conclusion. The conclusion then teases out two implications of this argument (one related to the disciplines included and another related to funding).Footnote 16

Jeffrey R. Wilson, “A New Definition of the Humanities”

Introduction

Paragraph 1: Thesis Statement

-

– Thesis: The humanities study the things humans make.

Body

Section 1: The most commonly offered alternative definitions.

-

– Paragraph 1.1: First, defining the humanities as a set of disciplines.

-

– Paragraph 1.2: The National Endowment for the Humanities definition.

-

– Paragraph 1.3: Second, defining the humanities as the study of the human condition.

-

– Paragraph 1.4: Uncertainty from Rens Bod and Neal Lester.

-

– Paragraph 1.5: Third, the “arts and humanities” formulation.

-

– Paragraph 1.6: I stand against “the arts and humanities.”

-

– Paragraph 1.7: Fourth, definitions that are true but embarrassingly articulated.

-

– Paragraph 1.8: Fifth, defining the humanities in contrast to the sciences.

-

– Paragraph 1.9: The emergence of the humanities in reaction to the modern sciences.

Section 2: Distinguishing the sciences from the humanities.

-

– Paragraph 2.1: Sciences associated with quantitative analysis, humanities with qualitative.

-

– Paragraph 2.2: It makes more sense to define these disciplines by what they study, not how.

-

– Paragraph 2.3: Definition of the sciences.

Conclusion

Paragraph 1: Argument Statement

-

– Argument: Definition of the humanities.

Paragraph 2: Counter-Argument

-

– Counter: Definition of the social sciences.

Paragraph 3: What’s at Stake

-

– Stakes: What disciplines are included in this definition?

Paragraph 4: Implications

-

– Implications: Clearly humanities disciplines.

Paragraph 5: Implications

-

– Implications: Borderline cases.

Paragraph 6: Implications

-

– Implications: Unexpected humanities disciplines.

Paragraph 7: Counter-Argument

-

– Counter: Some humanities disciplines do not self-identify as such.

Paragraph 8: Response

-

– Response: These disciplines are on the same team.

Paragraph 9: Implications

-

– Implications: Funding competition and advantages in the new definition.

Paragraph 10: Implications

-

– Implications: How closely does the institutional organization of academia align with this new definition?

The Q&A

This outline begins with a timely peg (the yearly Father’s Day holiday) as an entryway to a deeper discussion (about Shakespeare’s character Polonius as a father). After a three-paragraph introduction, the body of the essay tells the story of Polonius as a dad struggling with work-life balance, and the conclusion extends the discussion into other modern resonances of the family dynamics in Hamlet. Footnote 17

Jeffrey R. Wilson, “In Defense of Polonius”

Introduction

Paragraph 1: The Question

-

– Peg: Father’s Day.

-

– Orientation: Depersonalized story of Polonius’s life.

Paragraph 2: Brief Literature Review

-

– Hate Polonius Because of His Foolishness: Stubbes, Warburton, Johnson, Hazlitt.

-

– Hate Polonius Because of His Misogyny: Dreher, Robinson.

Paragraph 3: The Answer

-

– Method: Viewing Polonius through the lens of the common challenges of twenty-first-century parenting.

-

– Question/Problem: Polonius is a good character, more complex and sympathetic than critics usually recognize.

-

– Thesis: Polonius is a single father struggling with work-life balance who sadly chooses his career over his daughter’s well-being.

-

– Stakes: Other modern resonances of the family dynamics in Hamlet.

Body

Section 1: Polonius’s Possible Prehistories.

-

– Paragraph 1.1: Polonius as a Polish Immigrant

-

– Paragraph 1.2: Polonius as a Danish War Hero

-

– Paragraph 1.3: Polonius as a University Actor

-

– Paragraph 1.4: Polonius as a Widower

-

– Paragraph 1.5: Polonius as a Danish Government Official

Section 2: Polonius as a Single Father.

-

– Paragraph 2.1: His Wordiness as Dad Jokes

-

– Paragraph 2.2: Sending His Son Off to College in a Different Country

-

– Paragraph 2.3: His Daughter Romantically Involved with the Prince

-

– Paragraph 2.4: His Decision to Put His Career Before His Family

-

– Paragraph 2.5: His Attempt to Save the Queen

-

– Paragraph 2.6: The Effect of His Death on His Family

Conclusion

Paragraph 1: Argument Statement

-

– Counter: Stimpson on Poloniuses in Society

-

– Response: Public Poloniuses vs. Private Poloniuses

-

– Argument

Paragraph 2: What’s at Stake

-

– Stakes: Parenting in Hamlet

Paragraph 3: Implications: The Big Idea

-

– Implications: The Hamlets as a Step Family

Paragraph 4: Implications: The Concrete Examples

-

– Implications: King Hamlet, Queen Gertrude, King Claudius

Appendix B: Sample edits for public writing

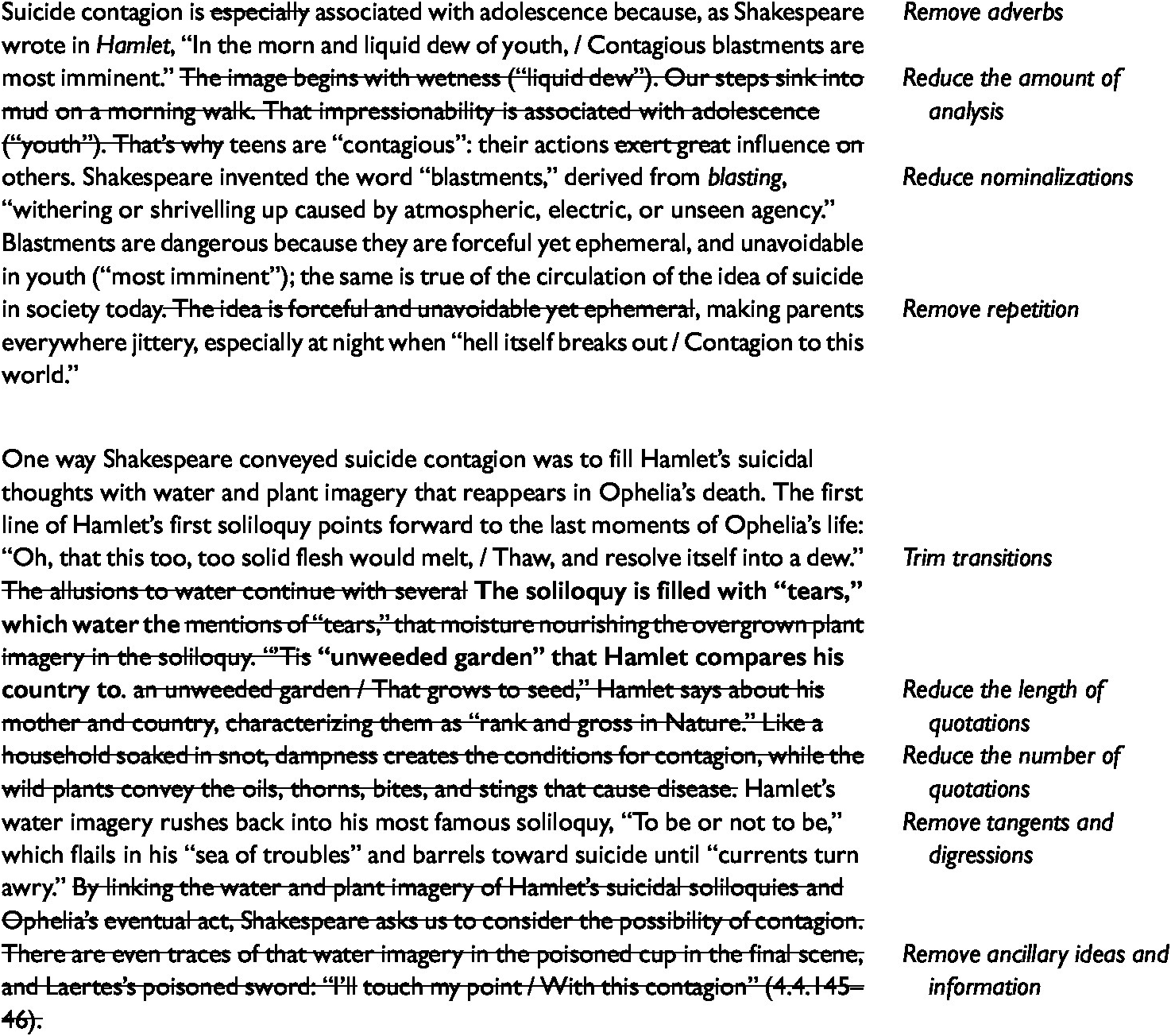

This page illustrates the strategies for editing discussed in the “Editing public writing” section.Footnote 18

Jeffrey R. Wilson, “Hamlet Is a Suicide Text – It’s Time to Teach It Like One”

Appendix C: Venues for public writing in the humanities

This list includes major newspapers, magazines, and online venues. Familiarize yourself with articles previously published at a venue that you’re submitting to or pitching. Don’t just pluck names off this list and spam them with your submission. One key to success in public writing is finding a venue whose scope and history align with the content and purpose of your article.Footnote 19

-

1843 Magazine

-

A Public Space

-

Academe

-

Aeon

-

American Conservative

-

American Prospect

-

The American Scholar

-

Antioch Review

-

Arcade

-

ArtForum

-

Arts & Letters Daily

-

The Atavist Magazine

-

The Atlantic

-

Atticus Review

-

The Baffler

-

Belt Magazine

-

Bloomberg

-

Book Riot

-

BookForum Magazine

-

Boston Globe

-

Boston Magazine

-

Boston Review

-

BuzzFeed

-

Cabinet Magazine

-

Chicago Tribune

-

The Chronicle of Higher Education

-

The Chronicle Review

-

CNN

-

Commentary Magazine

-

Commonweal Magazine

-

Contingent Magazine

-

The Conversation

-

The Conversation US

-

CounterPunch

-

Current Affairs

-

The Daily Beast

-

Daily Kos

-

Dissent Magazine

-

The Economist

-

Ed Surge

-

Education News

-

Education Week

-

Eidolon

-

Electric Literature

-

Esquire

-

First Things

-

Forbes

-

Foreign Policy

-

Fortune

-

Fox News

-

The Good Men Project

-

Granta

-

Grantland

-

The Guardian

-

Guardian Books

-

Guernica Magazine

-

Harper’s Magazine

-

Harvard Crimson

-

Harvard Political Review

-

Harvard Review

-

Hazlitt

-

The Hedgehog Review

-

History Today

-

The Hollywood Reporter

-

Huff Post

-

HuffPost Books

-

Humanities Magazine

-

The Hudson Review

-

The Humanist

-

In These Times

-

Inside Higher Ed

-

Jacobin

-

Jezebel

-

JSTOR Daily

-

Kenyon Review

-

LA Review of Books (LARB)

-

LA Times Books

-

Lapham’s Quarterly

-

Left Forum

-

Literary Hub

-

Literary Review

-

London Review of Books

-

Longform

-

Longreads

-

Los Angeles Times

-

Mashable

-

Mental Floss

-

Merrimack Valley Mag

-

Mic

-

The Millions

-

Minnesota Star Tribune

-

MLA Profession

-

The Morning News

-

Mother Jones

-

MSNBC

-

MTV

-

MTV NEWS

-

n+1

-

Narratively

-

The Nation

-

National Interest

-

National Review

-

The New Criterion

-

The New Inquiry

-

New Philosopher Magazine

-

The New Republic

-

New Statesman

-

New York Daily News

-

New York Magazine

-

The New York Review of Books

-

New York Times

-

New York Times Books

-

New York Times Magazine

-

The New Yorker

-

The New Yorker Page-Turner

-

Newsweek

-

NPR

-

NPR Books

-

Nursing Clio

-

Observer

-

OpenDemocracy

-

Orion Magazine

-

The Paris Review

-

Philosophy Now

-

Ploughshares

-

The Point Magazine

-

Politico

-

The Progressive

-

ProPublica

-

Prospect Magazine

-

Psychology Today

-

Public Books

-

Public Domain Review

-

Public Medievalist

-

Public Seminar

-

Publishers Weekly

-

The Quietus

-

Quillette

-

The Rambling

-

RealClearPolitics

-

Reason

-

The Ringer

-

Rolling Stone

-

The Root

-

The Rumpus

-

Salon

-

Seattle Times

-

The Sewanee Review

-

Slate

-

The Smart Set

-

Smithsonian Magazine

-

The Spectator

-

The Spectator USA

-

Standpoint Magazine

-

The Sun Magazine

-

The Sundial

-

Tampa Bay Times

-

Time

-

Times Higher Education

-

Times Literary Supplement

-

Truthout

-

Vanity Fair

-

Variety

-

Vice

-

Vogue Magazine

-

Vox

-

Vulture

-

Wall Street Journal

-

Washington Examiner

-

Washington Monthly

-

Washington Post

-

Words Without Borders

-

World Literature Today

-

The Yale Review

-

Zócalo Public Square

Appendix D: Sample submission letter

The letter below is emailed and addressed to a specific editor. It provides a title and peg in the first paragraph, a short summary in the second paragraph, and some info about the author in the third paragraph. The full piece is then included in the email itself, not as an attachment, which is preferred by some venues (especially newspapers).Footnote 20

Jeffrey R. Wilson, “What ‘The Northman’ Is Really About”

Dear Richard,

I’d like to see if CNN is interested in a piece I’ve written titled “Shakespherean Adaptations” – note the spelling – which might be pegged to the release of Robert Eggers’s The Northman on April 22. Since it’s a timely piece, I’d appreciate an expression of interest within two days, if possible.

Written below in full at 800 words, the piece uses The Northman and Spielberg’s West Side Story to mark a new era of Shakespearean adaptations filled with elisions (that jump over Shakespeare to go to his sources) and refractions (adaptations of adaptations).

I’m a faculty member in the Writing Program at Harvard University, where I teach a course called “Why Shakespeare?” My research has been featured on National Public Radio, New York Times, MSNBC, and Literary Hub, and I’ve written for public venues including The Chronicle of Higher Education, Academe, Salon, Zócalo Public Square, and MarketWatch. My first book, Shakespeare and Trump, was reviewed in venues such as The Guardian, Times Literary Supplement, Inside Higher Ed, and Shakespeare Survey. A second book, Shakespeare and Game of Thrones, was made into an online course called Bard of Thrones and featured on the Folger Shakespeare Library’s podcast, Shakespeare Unlimited. My third book, Richard III’s Bodies from Medieval England to Modernity: Shakespeare and Disability History, will arrive from Temple University Press in October 2022 and has been previewed on podcasts such as The State of Shakespeare.

Here’s the piece:

Shakespherean Adaptations

By Jeffrey R. Wilson

The Northman isn’t an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. It’s an adaptation of one of Shakespeare’s sources, a story told in Saxo Grammaticus’s History of the Danes. The Northman overleaps Hamlet.

Yet English-speaking people today usually only know of Saxo because of Shakespeare. The Northman’s audience derives from the popularity of Hamlet. That’s why the film is being released on April 22, one day before the annual celebrations of Shakespeare’s birthday on April 23. The Northman exploits the same Shakespearean text it avoids.

The Northman is a Shakespherean adaptation – note the spelling. It’s a different kind of Shakespherean adaptation than Stephen Spielberg’s West Side Story. That’s a remake of an earlier film adaptation of an earlier stage adaptation of Shakespeare’s play, which itself was a stage adaptation of an earlier English poem that was a translation of an earlier Italian novella. Where The Northman elides Shakespeare’s text, West Side Story is a refraction of adaptations.

The twenty-first century will be an era of Shakespherean adaptations filled with refractions and elisions – retellings inspired by materials that aren’t Shakespeare’s texts but are widely known today in relation to Shakespeare.

Joel Coen’s Macbeth is a straightforward adaptation. It just gets bonus points because Denzel. Succession and Empire are King Lear in the corporate world – regular adaptations. Nothing to see here. The Hogarth Shakespeare series that commissioned popular novelists to retell Shakespeare’s stories; the Public Theater’s all-Black performances of Much Ado About Nothing and The Merry Wives of Windsor; Teenage Dick and Fat Ham, which retell Richard III and Hamlet in modern American settings; and The Show Must Go Online’s pandemic series performing Shakespeare’s complete works on Zoom: all amazing but, in terms of the form of adaptation, not new. They employ strategies pioneered and perfected in Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957), Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead (1966), Sulayman Al-Bassam’s Richard III: An Arab Tragedy (2007), Toni Morrison’s Desdemona (2011), Ian McEwan’s Nutshell (2016), and Preti Taneja’s We That Are Young (2017).

But the 2009 zombie flick Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Undead? That’s Shakespherean, an adaptation of an adaptation. There’s also adaptation refraction in the Netflix House of Cards, an American streaming television adaptation of a British cable adaptation of a novel adaptation of Richard III.

Game of Thrones worked like both West Side Story and The Northman. There’s refraction: HBO made a television adaptation of George R.R. Martin’s novels, which adapted the English history that Shakespeare wrote several plays about, called the Wars of the Roses. But there’s also elision: Martin didn’t adapt Shakespeare but went around the playwright to his sources, even if that history is unavoidably inflected for the modern world by Shakespeare’s version. Similarly, The King on Netflix exploited Shakespearean associations with Henry V while shunning Shakespeare’s actual text.

Or Shakespherean adaptations overleap his texts to draw from his lives and afterlives. Television shows like Upstart Crow and Will riff on his personal life, adopting the approach of Shakespeare in Love. Like Maggie O′Farrell’s Hamnet, each reads plots and characters from the plays back into the biography of their author. This new era of adaptation goes beyond the questions and themes in Shakespeare’s stories to wrestle with the very idea of Shakespeare as the English language’s most celebrated author.

Station Eleven has both elision and refraction. The show is a television adaptation of a novel that doesn’t adapt one of Shakespeare’s plays but tells the story of a post-apocalyptic Shakespearean acting troupe. Likewise, plays like Lauren Gunderson’s The Book of Will and Carlyle Brown’s The African Company Presents Richard III stage moments from Shakespeare’s afterlives, a tradition including Julie Schumacher’s The Shakespeare Requirement (2018), Keith Hamilton Cobb’s American Moor (2015), the television show Slings and Arrows (2004), and older films like Theater of Blood (1973), Shakespeare Wallah (1965), and To Be or Not To Be (1942).

The twentieth century was largely an age of straightforward Shakespearean adaptation: performing his plays in business casual, remediating them from theater into new formats, rewriting his stories in modern settings, riffing on the hidden backstories of characters. Authors sought to write stories both connected to tradition and newly conceived for the present.

These new Shakespherean adaptations pursue this same double desire, but now that earlier age of adaptation has been enshrined as tradition. What once was radical is now passé. How will writers do something new with Shakespeare when adaptation has been done to death?

The push and pull of Shakespeare in these adaptations reflects the simultaneous nausea and enthusiasm many in the English-speaking world feel toward the author. His stories are captivating, the language beautiful, the performances inspiring, but Shakespeare is also crammed down our throats in school. Many who love Shakespeare are also suspicious of what’s been done in his name. Shakespherean adaptations allow authors and audiences to simultaneously embrace and reject Shakespeare.

General audiences can enjoy these stories without feeling like – without knowing – they’re being force-fed Shakespeare. Fans of Shakespeare revel in the opportunity to explore niche knowledge that goes beyond the plays to their sources and afterlives. And scholars love Shakespherean adaptations because they nicely illustrate the complex ways literature moves through history.

–

Jeffrey R. Wilson is a faculty member in the Writing Program at Harvard University, where he teaches the “Why Shakespeare?” course. He is the author of Shakespeare and Trump and Shakespeare and Game of Thrones. On Twitter @DrJeffreyWilson.

Thanks for your consideration.

Regards,

Jeff Wilson.

–

Jeffrey R. Wilson, Ph.D.

Harvard College Writing Program.

Appendix E: Sample pitch

Some venues ask for pitches rather than fully written submissions. A pitch is a short (two- to four-paragraph) overview of an article that you would like to write, allowing the venue to provide guidance and shape the piece. When a topic is timely, you may send a pitch (not the full piece) to multiple venues and let them know you’re doing so.Footnote 21

Jeffrey R. Wilson, “Is Donald Trump a Tyrant? Yes and No – Aristotle and Euripides would Disagree”

Dear Patrick,

I’d like to see if you’re interested in a piece I’ve written titled “Is Trump a Tyrant?” It grows out of my upcoming book, Shakespeare and Trump, appearing on Friday from Temple University Press. That book stems from the course I teach at Harvard University, called Why Shakespeare?, which grapples with the playwright’s prominence in modern life.

Here’s a quick overview of the piece:

Is Donald Trump a tyrant – based on historical definitions of that term? Not to Euripides (“there will be no public laws”), Socrates (“government of unwilling subjects and not controlled by laws”), or Hobbes (“They that are discontented under Monarchy, call it Tyranny”).

Trump is implicated, however, in Aristotle’s definition: “Tyranny is a kind of monarchy which has in view the interest of the monarch only.” Milton Christianized Aristotle: “A Tyrant whether by wrong or by right coming to the crown, is he who regarding neither law nor the common good, reigns only for himself and his faction.” I am convinced that this is the case with Trump, who is also implicated in the tactics of tyranny Aristotle laid out: “(1) he sows distrust among his subjects; (2) he takes away their power; (3) he humbles them.”

Ultimately, Trump both is and is not a tyrant. He is to Aristotle, Milton, and Locke, not to Euripides, Hobbes, and Madison. He is a tyrant in personality but not in policy. Legally, Trump is not a tyrant, but morally he is. He and his lawyers hew closely to the laws he cannot break – or that will not be enforced – while bucking the unwritten norms of presidential behavior. Or, put differently, Trump is not a tyrant, but he acts like one.

A bit more about me: I also have a book called Shakespeare and Game of Thrones forthcoming from Routledge. Articles of mine have appeared in academic journals such as Modern Language Quarterly, Genre, and College Literature. And my work has been featured in public venues such as National Public Radio, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Profession, Academe, Public Seminar, The Smart Set, The Spectator USA, CounterPunch, and Shakespeare and Contemporary Theory.

If possible, I’d love to time the appearance of the piece to the book’s release date on April 20, 2020. Since it’s a timely piece, I’d appreciate an initial expression of interest within three days, if possible.

Thanks for your consideration.

Regards,

Jeff Wilson.

–

Jeffrey R. Wilson, Ph.D.

Harvard College Writing Program.

Appendix F: Sample submission plan

This submission history of an article shows many unsuccessful submissions as well as some offers to publish the piece that ultimately fell through because the venue wanted to change or shorten the piece too much. Some submissions were to individual editors’ email addresses (which have been anonymized). Some were to general submission email accounts. Some were to online portals.Footnote 22

Jeffrey R. Wilson, “Businesses Have a Lot to Learn from the Impromptu ‘Teaming’ That Happens in Theater”

Appendix G

Examples are better than rules. Below is a collection of short-form models (op-ed pieces at around 800–1,000 words) and long-form models (feature articles running 2,000–8,000 words) that illustrate effective public writing in action.

Short-form models

-

Picq, Manuela. 2014. “The Failures of Latin America’s Left.” Al Jazeera, November 7.

-

Greenblatt, Stephen. 2016. “Shakespeare Explains the 2016 Election.” New York Times, October 8.

-

Mbembe, Achille. 2016. “The Age of Humanism Is Ending.” Mail & Guardian, December 22.

-

Cartledge, Paul. 2016. “Democracy: A User’s Guide.” History Today, July, vol. 66, no. 7.

-

Rutherford, Emily. 2018. “Dare to Speak Its Name: Pederasty in the Classical Tropes of Call Me by Your Name.” EIDOLON, February 12.

-

Shahvisi, Arianne. 2019. “‘Men Are Trash’: The Surprisingly Philosophical Story Behind an Internet Punchline.” Prospect, August 19.

-

Deloria, Philip. 2019. “The Invention of Thanksgiving.” The New Yorker, November 18.

-

Olusoga, David. 2020. “The Toppling of Edward Colston’s Statue Is Not an Attack on History. It Is History.” The Guardian, June 8.

-

Kaba, Mariame. 2020. “Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police.” New York Times, June 12.

-

Dodd, Emlyn. 2023. “A Newly Uncovered Ancient Roman Winery Featured Marble Tiling, Fountains of Grape Juice and an Extreme Sense of Luxury.” The Conversation, April 17.

-

Peña, Lorgia García. 2023. “A Different Border Crisis Mirrors What’s Happening in the U.S.” New York Times, October 22.

-

Guha, Ramachandra. 2024. “Why 2024 Is India’s Most Important Election Since 1977.” Scroll, April 21.

Long-form models

-

Coates, Ta-Neihisi. 2014. “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic, June 15.

-

Ahmed, Sarah. 2015. “Against Students.” The New Inquiry, June 29.

-

Morris, Wesley. 2016. “Last Taboo: Why Pop Culture Just Can’t Deal with Black Male Sexuality.” New York Times Magazine, October 27.

-

Anderson, Kurt. 2017. “America’s Gun Fantasy.” Slate, October 5.

-

Dederer, Claire. 2017. “What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?” The Paris Review, November 20.

-

Whitmarsh, Tim. 2018. “Black Achilles.” Aeon, May 9.

-

Rich, Nathaniel. 2018. “Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change,” New York Times Magazine, August 1.

-

Altman, Rebecca. 2021. “Upriver: A Researcher Traces the Legacy of Plastics.” Orion Magazine, June 2.

-

Manshel, Alexander, and Melanie Walsh. 2023. “What 35 Years of Data Can Tell Us About Who Will Win the National Book Award.” Public Books, November 6.