INTRODUCTION

When in the summer of 1460 Ippolita Maria Sforza (1445–88) and her brother Galeazzo Maria (1444–76) were exercising their Latin skills through a humanist-style correspondence, Galeazzo painted a very positive picture of his sister in a letter written from his library on September 2. Both her character and her learning are praised:

But there is something else, too, on which I will not congratulate you, since you are so modest, but I will rejoice on my own. For I have seen on the front of your letter the name of Jesus written in Greek letters; this indicates to me that having intensely familiarized yourself with Latin letters, you now also take it upon you to become familiar with the Greek. I do not doubt that you understand what a great grace, what a great embellishment this will yield. I, in any case, am triumphant beyond joy, while I ponder that I have been blessed with a sister who, just as she shines among Latin maidens, will be illustrious among foreign ones by every virtue.Footnote 1

It was common in the correspondence between Ippolita and Galeazzo to put Jesus's name above their letters.Footnote 2 Galeazzo is impressed that his sister had done so in Greek, a language with which she was apparently developing a fascination. His admiration is likely to have been feigned in part, since Ippolita might have simply copied the Greek heading from a letter Galeazzo had sent her earlier that summer, on August 27.Footnote 3 This letter bears the Greek inscription ΙΗϹΟϹ (Jesus).Footnote 4 As such, it seems that in the summer of 1460 the fifteen-year-old Ippolita Sforza was not yet schooled in Greek but had plans to study the language in the near future. This piece of evidence, therefore, often overlooked in discussions of Sforza's learning, does not allow for any firm conclusions about the extent to which she really knew this language, rediscovered in Western culture during the Renaissance and at once promoted to invaluable cultural and intellectual capital.Footnote 5 What is more, in 1460 Greek had only been taught for about six decades on the Italian Peninsula, making Sforza an early case of female Greek learning.

In this paper, I look in detail at Ippolita Maria Sforza's Greek learning, adopting a double approach and focusing on two poorly studied Greek grammars dedicated to her by Constantine Lascaris (1434–1501) and Bonino Mombrizio (1424–78/82?). Two questions constitute my starting point. First, are there any material traces in these sources to confirm that Sforza studied Greek? Second, how did Lascaris and Mombrizio envisage Sforza as a learner of Greek? More specifically, I investigate to what extent gender played a role in devising these two learning tools. Was Sforza's gender a factor the grammarians reckoned with?

I argue that Ippolita Sforza was in an excellent position both to study Greek and to act as a patron of this new subject. What is more, whereas Sforza without a doubt fostered the creation of Greek manuals and the study of Greek texts, it is also very likely that she learned the language with Constantine Lascaris under the guidance of her trusted teacher Baldo Martorelli. I illustrate that the overall method adopted to teach Sforza Greek did not substantially differ from male-focused methods, even though there are subtle adaptations tailored to her worldview and interests. Along the way, I try to correct common misunderstandings in accounts of Sforza's Greek learning.

This paper joins in the enormous wave of scholarship devoted to women's learning and writing, which has greatly enriched the study of the history of humanism, literature, and classical scholarship in the past few decades. In particular, I attempt to make a small contribution to this ever-growing field by drawing in Greek studies, an aspect of Renaissance intellectual and pedagogical life that is attracting increasing attention itself, but where gender perspectives are still rather rare.Footnote 6 This paper also joins in recent developments in the history of language studies and teaching. Scholars in this field have been extending their interest to marginalized figures, including “the distant and neglected voices” of women, students, and informants.Footnote 7 Sforza's case has not yet received the attention it deserves, and I try to illustrate through it that, although “the learning of Latin and Greek—and the access to knowledge this implied—was largely considered a male preserve,” women were by no means categorically excluded from these languages, not even from Greek.Footnote 8

I proceed in four steps. First, I discuss the state of research on Sforza's Greek learning, while situating her activities in their historical, cultural, and intellectual context. I pay particular attention to the education of this cultivated Milanese noblewoman, and to traces of Greek competence in her writings and library. Then, I describe in detail the form and contents of the Greek grammar manuscripts dedicated to her. The main body of the article deals with the core questions set out above; it investigates the material traces of Sforza's Greek learning, and the ways in which she was imagined as a student of Greek. The focus of this part is whether the Greek grammarians adapted their didactic approach to the gender of their pupil, and if so, to what extent. Finally, I survey my main conclusions.

A CULTIVATED PRINCESS WITH NO GREEK?

Ippolita Sforza was the second-born child and eldest daughter of the Duke of Milan Francesco I Sforza and Bianca Maria Visconti. Her parents attached great value to a decent education for all their children, and they were, moreover, “thought of as well disposed to educated women.”Footnote 9 It is no wonder, then, that Sforza enjoyed a thorough and variegated training. Her education partly served to prepare her for her future life as the wife of Alfonso II of Naples (1448–95), the Duke of Calabria and son of Ferdinand I of Aragon, who eventually ruled as king of Naples for about a year (1494–95), long after Sforza's death. In her capacity as future queen, Sforza was expected to move to the Neapolitan court, at the time the Duchy of Milan's greatest rival for power on the Italian Peninsula. Evelyn Welch has described Sforza's education as follows: “In preparation for her position, she was, like most aristocratic girls of the period, taught to ride, to play musical instruments, to sing in French, to dance—a skill for which she was particularly renowned—and to read and write in both the vernacular and in Latin. As the eldest daughter, she had a personal tutor, Baldo Martorelli, whose Latin grammar book written on her behalf still survives. He also had Ippolita copy out works of Cato and Cicero and write her own composition in praise of her mother, a common literary activity amongst the Sforza children.”Footnote 10 She took many classes together with her brother Galeazzo Maria. Rather exceptionally for a woman in Quattrocento Milan, and rather aptly given the origin of her unconventional first name, Sforza came to express an interest in Greek during her late teens.Footnote 11 She did so while waiting for her marriage with Alfonso to occur, which it finally did in 1465, after ten years of engagement.Footnote 12 However, her Greek learning, for which I make a case in this paper, is not as generally accepted as Welch and others make it seem.Footnote 13 The caution expressed by M. Serena Castaldo, the modern editor of part of Sforza's correspondence, and Jeryldene Wood, her most recent biographer, is, in other words, justifiable.Footnote 14 A closer look at the grammars dedicated to her confirms the claims of scholars like Welch, who tend to mention her proficiency in Greek merely as a petty detail, or use it as a means for character-building.Footnote 15 Skepticism about her Greek competence is certainly in order, since, contrary to her Latin schooling, no substantial evidence has thus far been found that would support her studying Greek.

For instance, Sforza never produced a Greek manuscript as she did with Cicero's Cato the Elder on Old Age, which she finished copying and annotating on 8 July 1458, under Martorelli's guidance.Footnote 16 Despite numerous quotations in Latin from Greek authors, Cicero's work does not contain any actual Greek, so this manuscript does not help one assess her Greek competence. Probably it was nonexistent at the time of copying, since she had not yet met her presumed teacher of Greek, who arrived in Milan in late 1458. Sforza's own humanist writings do not offer any obvious evidence for knowledge of Greek either. The four edited Latin texts that are extant—three brief orations (1455, 1459, 1465) and a six-verse elegy on her father's death (1466)—undeniably prove that she had an excellent mastery of Latin, probably thanks to Martorelli's teaching and his grammar manual (ca. 1454–60).Footnote 17 It is not inconceivable that she was guided by the well-known Hellenist Francesco Filelfo (1398–1481) in writing her 1459 oration for Pope Pius II.Footnote 18 The earlier oration, from 1455, served to celebrate the wedding of her half-brother Tristano Sforza and Beatrice d'Este, whereas the 1465 oration was pronounced in her mother's honor and shows a stylistically more mature Ippolita Sforza than the two orations from the 1450s, when she was only in her early teens.Footnote 19

Sforza quoted from classical Latin authors in all three orations, but never from Greek ones, not going further than attributing a saying to the Greeks in the 1455 epithalamium, which she no doubt knew through Cicero's Letters to Friends.Footnote 20 This suggests that she knew this ancient letter collection, which abounds in Greek phrases and hence reflects the Latin-Greek code-switching of the Roman upper classes.Footnote 21 Yet it is unclear from her oration whether she was actually able to read these Greek passages. The use of Greek formulaic terms, such as “Telos” (for Τέλος, “the end”) at the end of the epithalamium, does not warrant the conclusion that she knew Greek either, but it does suggest an interest in the language.Footnote 22 Somewhat unexpectedly, there is no reference to Greece in her address to Pius II, even though she delivered her oration at the Mantuan congress, convened by the pope to mount a crusade against the Ottomans, where Filelfo also spoke and did refer to Greece.Footnote 23

Sforza perfected her Latin skills in the early 1460s, being capable of full-fledged Ciceronian periods in her last oration.Footnote 24 It was also in this time frame, the early 1460s, that she must have studied Greek, but a command of the language does not shine through in her 1465 praise of her mother. The same holds for her short elegy, except perhaps for the enigmatic word phar, which Jane Stevenson has taken as a noun meaning “light”: “Hiis igitur sevum phar est lenire dolorem / Hiis propria sunt magno vota ferenda deo [Therefore for these, there is a light to relieve severe grief, for these are proper prayers to be uttered to almighty God].”Footnote 25 At first glance, phar might seem like an oddly Latinized form of a Greek word like φάρος, “lighthouse,” but it turns out to be a misreading for the well-known Latin word phas (fas).Footnote 26 In sum, Sforza's writings do not reveal any Greek competence.

Of course, the absence of Greek from her writings does not necessarily mean that she had no Greek at all. There might be other explanations. It might not have suited a young woman's rhetorical and literary persona to insert exuberant Greek phrases into her orations and poetry—or, as Sforza put it herself in her 1459 oration to Pius II, “But why do I dare to commend your virtues? Is it so that I can render those golden and near-divine virtues of yours as though muddied with rude and girlish words?”Footnote 27 This passage might be read as more than just a “comic self-portrait” or a typical expression of the humility topos.Footnote 28 It may also count as young Sforza's stylistic directive, which had no place for Greek. Indeed, even if one disregards the fact that she probably did not study with Lascaris until 1459, it would have been excessive to use Greek at the Mantuan congress, especially since the renowned Hellenist Filelfo, her sparring partner in preparing her speech, had not used the language in his own oration. The use of Greek, although not inappropriate for this congress, where the misfortune of the Greek lands was intensely discussed, might have surpassed female decorum. It was remarkable enough that young Sforza had the opportunity to speak in public. Italian humanist pedagogues such as Leonardo Bruni, writing in a republican rather than an aristocratic context but addressing a noblewoman nonetheless, had argued earlier in the century that “public oratory and disputation” were “unbecoming and impractical for women.”Footnote 29 Then again, Greek as a subject was not excluded by Bruni, whose pedagogical program for girls “followed exactly the studia humanitatis proposed to and followed by boys,” with the exception just mentioned—rhetoric.Footnote 30 He did, however, suggest that the emphasis be on religious and moral literature. Later, in the sixteenth century, pedagogues were less liberal, with Ludovico Dolce even advising princesses and queens not to get involved with Greek; Dolce, who drew heavily on the ideas of Juan Luis Vives, said he wanted to avoid “plac[ing] such a heavy weight on the shoulders of women.”Footnote 31

Sforza, chronologically in between Bruni and Dolce, was still encouraged to pursue her Greek studies, although her reading corpus seems to have been much more limited than what Bruni had proposed. In addition to two Greek grammars, she can be associated with only one other Greek work. In 1465, her father included in her dowry fourteen books, mostly religious but also classical texts, in total worth 500 ducats.Footnote 32 Although this gift was in the first place intended for the Aragonese royal family, it can also be assumed to reflect the intellectual tastes and cultivation of Ippolita Sforza. Through their monetary value and textual contents, the books symbolized the financial and cultural capital of the Sforza family. The Duke of Milan's choice to include books in his daughter's dowry might also suggest that he knew she enjoyed reading, and that he wanted her to continue cultivating her interests after her wedding. The three secular books on the list exhibit both medieval tastes and humanist interests. On the one hand, the list includes Giovanni da Genoa's Catholicon, a thirteenth-century Latin handbook. On the other, it also includes the classical authors Livy and Virgil. The lavish Virgil manuscript, including Servius's commentary and still extant today, bears testimony to the great wealth of the Sforza family. Its impressive decorations, such as painted initials—the first of which represents Ippolita Sforza herself—stand in stark contrast with the sober ornaments in the Greek grammar manuscripts I discuss below.Footnote 33 The religious category on the list includes various texts, such as a Bible, probably the Latin Vulgate version; liturgical and prayer books; saints’ lives; works by Augustine; and, notably, an “evangelistario grecho.”Footnote 34 The presence of this Greek gospel manuscript, at 25 ducats one of the cheapest books on the list and thus probably in a sober execution, might suggest that Sforza did, in fact, read some Greek, especially since it was common to combine the reading of such relatively easy texts (large portions of which a pious woman such as Sforza would have known by heart in Latin) with the study of Greek grammar.Footnote 35 Indeed, differently from Latin, the Renaissance study of Greek often paired grammar education with basic reading skills—an inductive approach also emerging from Lascaris's manual.Footnote 36 The choice of a religious text for Sforza's Greek reading—whether it was at her teacher's instigation or of her own accord—would fit in nicely with her image as a pious woman, well versed in literature and scholarship, which was omnipresent in her writings. There is no other straightforward proof confirming that she indeed read the gospel manuscript, which is now presumably lost, but she was clearly in the material possibility to do so, as it was part of her dowry that accompanied her to Naples. Below, I illustrate that the authors of the grammars, no doubt accommodating to Sforza's reading preferences, indeed imagined her acting on this opportunity to study the gospel in Greek.

Sforza could have developed a fascination for Greek by strolling through her family library at their castello in Pavia, which had been built by her mother's family, the Visconti, in the Trecento. According to inventories from 1426 and 1459, this library contained Homer's Iliad and works by Plato in the original Greek, probably stemming from Petrarch's collection, although the overall number of Greek works was very limited.Footnote 37 Works by Greek authors in Latin translation were also sparse, with the obvious exception of Aristotle, whose works dominated scholarship at that time, mostly in medieval Latin translations.Footnote 38 These texts would have been much more difficult than the Greek gospel, so they might have been beyond Sforza's competence. Still, they could have easily sparked her Greek enthusiasm, as testified by, among others, her brother—an enthusiasm further fueled by the handbooks developed for her in the 1460s. To summarize, Sforza was very much in the material possibility to learn and read Greek, and is very likely to have had a basic competence in the language, even if her writings do not display any active engagement with Greek.Footnote 39 In the following sections I further corroborate this analysis.

Sforza can be said to belong “to the tradition of urban, classically educated Italian women who came of age as intellectuals in the later fifteenth century,” including other Greek students such as Isotta Nogarola, Cassandra Fedele, and Laura Cereta.Footnote 40 As I have mentioned, Sforza's classical schooling is evident in her writings.Footnote 41 Even though her more than six hundred extant letters, mostly written in Italian, are in the first place familiar and diplomatic exchanges with members of the Milanese and Neapolitan courts, they do exhibit humanist traits, abounding in eloquence, Latin phrases, and references to classical Latin literature.Footnote 42 She has shown herself to be a skillful diplomat and a pious woman, both qualities that, in combination with her physical beauty, have led her to be praised by early modern and modern commentators alike. Through these and other properties, including her rhetorical talent, Sforza became an exemplum of the ideal noblewoman in Renaissance female biographies, being one of those “learned women [who participated] . . . in the family business of education, who brought honor both to their natal families and to the larger civic family of their native cities.”Footnote 43 In this context, it is noteworthy that one of the two Greek grammar authors, Bonino Mombrizio, composed a lengthy poem about the vices of women (Momidos libri XII). Mombrizio dedicated this work to the wife of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Bona of Savoy (1449–1503), showing that he was concerned over the moral education of women in the Sforza family.Footnote 44 As to modern appraisals, I can quote from the introduction to Sforza's correspondence and orations by Robin and Westwater, who admire “her influence in affairs of state as a woman and her ability to move policy at the highest levels of government, undiminished by her sex. Intellect trumps gender in the roles she assumes in her letters as unofficial ambassador, adviser, and informant.”Footnote 45

Sforza's education in Milan, entrusted to several private tutors, first and foremost Baldo Martorelli, served to prepare her for her future as a leading noblewoman and queen. Such an education not only allowed her to gain practical skills but also served as a display of the cultural capital she, and, by extension, her family, possessed. For language and letters, Latin grammar was the obvious gateway, as witnessed by Martorelli's teaching of Sforza and her brother from 1454 to 1460. Martorelli often also assisted her in writing letters and moved to Naples with her in 1465, together with Constantine Lascaris.Footnote 46 Latin was vital for continuing her studies of Greek in the 1460s, since it served as the didactic metalanguage. Martorelli paved the way for Lascaris and Mombrizio, who could rely on Sforza's previous studies. By consequence, when Lascaris joined Martorelli as private teacher of the Sforza household, and certainly when Lascaris and Mombrizio were preparing their grammar gifts for her, Ippolita Sforza must have been at least fifteen years old, and probably older.Footnote 47

It seems that Sforza's humanist learning was largely restricted to her Milanese youth and her early years in Naples. Her pursuit of a humanist education dwindled as her marriage was finally contracted at age twenty. As a result, she did not really further develop her classical learning. The relative invisibility of her Greek competence was the obvious result, since she studied the language only in the years leading up to her marriage, and probably only for a relatively short period. McCallum-Barry observes that, for the earlier humanist Isotta Nogarola (1418–66), “the life of scholarship was more important to her than marriage,” a choice that Sforza appears to have made differently, or at least was encouraged to make as part of her family's political strategies and as a result of her key diplomatic role at the Neapolitan court.Footnote 48 Also unlike Nogarola, Sforza's classical learning apparently did not reach beyond exhibitory rhetoric, poetry, and letter-writing, as she did not produce any works with early feminist ideas such as Nogarola's De pari aut impari Evae atque Adae peccato (Of the equal or unequal sin of Adam and Eve, 1451). Instead, Sforza's position at the Neapolitan court demanded her full attention. In her diplomatic interactions, however, she did rely on her classical learning, and hence saw a great practical use for her education. Her interest in art and literature never petered out, as she welcomed artists and intellectuals at Castel Capuano, in addition to ambassadors and heads of state.Footnote 49 In sum, occupied by diplomatic and political tasks, she developed from student to patron, a change of role also perceptible in her engagement with Greek.

Although female decorum might have played a role in encouraging Sforza to tone down her humanist interests after her marriage to Alfonso and concomitant move to Naples, it would be too simple to conclude that her learning was considered transgressive. Not only did she set up a studiolo (study room) upon her arrival at the Neapolitan court but it was also there that she composed in 1466 the Latin elegy in memory of her father, perhaps using the books he had given as her dowry.Footnote 50 Transgression alone is too simple an explanation for the waning of her humanist learning, especially since other powerful female intellectuals such as Isabella d'Este did pursue their studies once married.Footnote 51 There are other factors to be reckoned with. Sforza was probably too busy managing court life, or simply lost interest in studying. Although loss of interest is less likely given her activities as patron, she might have become disillusioned to some extent by the new and difficult humanist subject—Greek. Whatever the case, her financially unstable situation in the south, where her court was an important place of mediation between Naples and Milan, certainly did not create an agreeable atmosphere for her to continue her studies.Footnote 52 In the end, it was probably a combination of the aforementioned factors that led to her abandonment of learning Greek in favor of patronage for Greek and the arts.

SFORZA'S TWO GREEK GRAMMARS IN THEIR HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Having sketched Ippolita Sforza as a cultivated Renaissance woman, and the scant traces of her Greek learning, I now turn to two key sources, which, oddly enough, have been largely disregarded in discussions of her engagement with the language: the two Greek grammar manuscripts dedicated to her. As far as I can tell, Sforza was the first woman in history to have dedicated to her no less than three different grammars, all in the decade around 1455–65.Footnote 53 The earliest was for learning Latin, procured by her teacher Baldo Martorelli around 1454 and finished by 1460 at the latest.Footnote 54 The two later manuscripts contain different versions of the Greek grammar by Constantine Lascaris, Sforza's Greek teacher, as I argue.Footnote 55 The earlier Greek grammar also provides what is probably the first extant textual witness of Lascaris's grammar epitome; this autograph manuscript, preserved in Paris, was the basis of Förstel's edition of the text.Footnote 56 The manuscript, henceforth referred to as “the Paris manuscript,” cannot be dated exactly, the earliest possibility being the final months of 1458, when Lascaris arrived in Milan. The latest option is mid-1466, when he left Naples and, hence, Sforza's entourage. Before his departure, Lascaris was probably supervising, in tandem with Martorelli, Sforza's education after her marriage in 1465, possibly at her own instigation, and perhaps also that of her father or King Ferdinand. In any case, Ferdinand also appointed Lascaris public professor of Greek and rhetoric in Naples on 1 June 1465.Footnote 57 The watermark evidence of the Paris manuscript suggests that Lascaris finished the manuscript toward the end of his Milanese period, since he used the same paper for a manuscript dated 1464.Footnote 58 This fact might suggest that the grammar manuscript, too, was finished around that time—so, later than is usually assumed.Footnote 59 A possible counterargument to this late dating might be the involvement, in the correction of the manuscript, of Demetrios Kastrenos, Lascaris's rival for the Greek chair in Milan in 1462–63, a position for which Kastrenos was backed by Francesco Filelfo. Lascaris, however, had the support of over forty local noblemen and humanists, and was eventually appointed public professor of Greek there in 1463. Kastrenos did not stand a chance, and after years of struggling for his livelihood—in Milan (1458–ca. 1466), Pisa (1466), Urbino (1466), and Milan again (1473)—he left Italy disillusioned, traveling back to the Ottoman-occupied Greek lands “because of lack of opportunity in Europe.”Footnote 60 But Lascaris's relationship with Kastrenos might have remained good after their competition in Milan. In a well-known letter Lascaris wrote from Messina to his friend Juan Pardo in the early 1480s, he pitied the fate of Greek migrants, including a certain Demetrios, probably Kastrenos: “Demetrios was forced to return to his country and serve the barbarians.”Footnote 61 Kastrenos's involvement with the grammar manuscript, therefore, offers no conclusive evidence for an early dating, although his correction does imply that it was finished before Lascaris left for Naples in mid-1465. The available evidence, in sum, suggests that the Paris manuscript must have been produced some time in the years 1463–65.

Except for the Latin dedication letter, which Lascaris had asked an unidentified local scribe to write—he wrote only the two Greek phrases in it himself—the main text of the manuscript is entirely written in Greek, as was customary among the first generations of Renaissance Greek grammarians of Byzantine descent.Footnote 62 This carefully produced manuscript has never been studied as a testimony to Lascaris's teaching, even though it contains numerous interlinear annotations in Latin and other basic learning materials, such as a Lord's Prayer in Greek, all suggesting a didactic use. The default view on the authorship of these notes is that they are anonymous, if they are discussed at all.Footnote 63 I will argue that the interlinear notes in this manuscript are likely to reflect Lascaris's teaching of Ippolita Sforza, either in Milan (ca. 1463–65) or in Naples (ca. 1465–66). In fact, I will put forward below the hypothesis that the notes are from the hand of Baldo Martorelli, suggesting a triangular teaching setup.

The slightly later Greek grammar manuscript is a Latin verse translation of Lascaris's Greek grammar epitome composed by the local humanist Bonino Mombrizio, and is currently preserved in Milan—henceforth referred to as “the Milan manuscript.”Footnote 64 Mombrizio studied in Ferrara with Vittorino da Feltre before arriving in Milan in 1458—the same year as Lascaris—and became especially anchored in the circle of Sforza's brother, Galeazzo Maria.Footnote 65 The manuscript's later date is confirmed by the fact that Mombrizio referred to Lascaris's presentation copy, as Raschieri has pointed out.Footnote 66 The text of the Milan manuscript has still not been edited in its entirety, despite its historical value for the history of language-learning, especially in relation to gender. Scholars have edited excerpts, particularly from the introduction, considered most interesting for historical reasons, and in one case also from the main body of the grammar for a superficial analysis.Footnote 67 It does not lie within the scope of this article to edit the grammar, nor to analyze it in great detail. Instead, I try to illustrate the relevance of this source for the history of women's language-learning in the Renaissance, even though the manuscript was probably never completed or presented to Ippolita Sforza, as I argue below.

Lascaris's autograph was decorated with a lavish initial, carefully corrected by his fellow countryman Demetrios Kastrenos before presentation, and—most likely at a later date—provided with marginal summarizing annotations by another countryman, George Hermonymus of Sparta (ca. 1430–after ca. 1508).Footnote 68 The Paris manuscript was, in other words, carefully prepared and completed by Lascaris, making it very plausible that it was actually presented to Sforza.Footnote 69 Mombrizio's version, although corrected in some places and modestly rubricated, lacks initials, even though space has been left for them throughout the manuscript. Does this unfinished state mean that it was never actually presented to Sforza? Given the fact that the Lascaris autograph might be much later than previously thought, dating to around 1463–65, it is not inconceivable that Mombrizio did not get his verse translation ready in time for Sforza's departure for Naples in mid-1465, and did not bother to complete it and have it decorated. The late dating of the two manuscripts might suggest that Lascaris and Mombrizio envisaged their works as wedding gifts, although they were not ornamented as exuberantly as some of the books that were part of Sforza's dowry.Footnote 70 Raschieri has suggested that Mombrizio's translation was indeed intended as a wedding gift, on the grounds that Sforza is already addressed as princess of Capua and duchess of Calabria in his dedicatory verses, but is at the same time still called uirgo, “maiden.”Footnote 71 She was already granted the titles her marriage had earned her before the actual marriage had occurred. However, the Latin noun uirgo might also be used in its general sense of “young woman,” whether married or not, making this piece of evidence inconclusive for the composition date of Mombrizio's grammar. In sum, Lascaris's autograph probably dates to the first half of the 1460s, most likely the years 1463–65, and Mombrizio's verse translation was started soon afterward but never completed.

If my hypothesis on the late dating is correct, the fact that the two manuscripts are preserved in different institutions today might reflect their different fates in the Quattrocento. Whereas the Milan manuscript seems never to have left its city of composition, the Paris manuscript probably traveled with Ippolita Sforza to Naples. It is impossible to find out what happened to Lascaris's autograph in the decades after Sforza's death, but it became part of the private collection of Jean-Jacques de Mesmes (d. 1569), who actively tracked down Greek manuscripts, and his offspring.Footnote 72 Eventually, the manuscript was donated in 1679 by the Duchesse de Vivonne, born Antoinette-Louise de Mesmes, to the book collector Jean-Baptiste Colbert. In 1732, the Colbert collection entered the French royal library, which later became the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Two other unidentified owners go by the names J. de Sanzay (or Sauzay?) and Simone Guerrero.Footnote 73

Lascaris and Mombrizio probably did not only see Sforza as a pupil, as seems to be the default view of many modern researchers.Footnote 74 In fact, their relationship also has characteristics of that of a burgeoning patron attracting scholars who were looking to sustain their livelihood, a hypothesis that can be backed by at least two arguments. First, the practice of offering luxurious presentation copies was usually reserved for influential noblemen or women whose patronage the author was seeking. Sforza may have stood proxy for her father, the Duke of Milan, in which case Lascaris and Mombrizio were using her as a patron by association.Footnote 75 However, the fact that Lascaris accompanied Sforza to Naples in 1465 may suggest that this picture is not entirely correct, and that Lascaris saw her as a patron of Greek studies, even if she would still be dependent on her husband Alfonso and her father-in-law Ferdinand I in her new home. In this context, it is relevant to mention that Constantine Lascaris arrived in the Duchy of Milan in late 1458 as a young migrant, only twenty-four years of age, who still had to make a name for himself and integrate into Italian intellectual and cultural life. Born in Constantinople in 1434, Lascaris was educated there by John Argyropoulos (1415–87), who, like his pupil, settled in Italy after the Ottomans captured the Byzantine capital in 1453. It took Lascaris over five years to reach the West, after captivity in Ottoman hands and wanderings through Greece.

Lascaris's young age and recent migration are often left unmentioned in accounts of his relationship with the Sforza family, but these are highly relevant to understanding what Lascaris was trying to achieve by dedicating his Greek grammar to Ippolita Sforza. He was not merely looking to teach his prominent pupil Greek but probably also trying to secure patronage for his work. Since 1460 at the latest, he was producing tools for Greek language learners, because there was a shortage of both instruments and teachers, as a colophon to his treatise on dialectal variation in the Greek pronoun reveals.Footnote 76 Lascaris was, in other words, capitalizing on a local demand for Greek. The fact that he became lavish in wasting paper, writing only two or three lines on one page, suggests that he had started to make a good living out of his activities as teacher, grammarian, and scribe by the end of his stay in Milan.Footnote 77 This stable position might have encouraged him to reach for the sky and address the Sforza family, whom he knew attached great value to education. His dedicatory letter to Ippolita Sforza, in any case, shows a Lascaris seemingly still trying to get into the family's favor:

To the most excellent lady Ippolita, greetings from Constantine Lascaris the Greek. After I had heard, most excellent lady, that you were not only busy with Latin literature but were also taking great delight in the Greek, from which every kind of science has sprouted, I considered it my duty to send you this summary of the eight parts of speech, which I have recently composed. I have some trust that this present, however small and unworthy of such a distinguished princess, could prove acceptable to your extraordinary humanity. Yet, one thing in particular I beg of you: please value the actual gift not as much as you do the good will of the giver, but do not reject the little work as unworthy of a close reading. For perhaps you will find something in it that you will take to be of use to you. Farewell and keep learning.Footnote 78

Lascaris's awareness of Sforza's interest in Greek is here apparently based on hearsay, not personal contact with the princess. His formulation recalls Galeazzo Maria Sforza's praise of his sister's start with the new subject of Greek, quoted at the outset of this article: “This indicates to me that having intensely familiarized yourself with Latin letters, you now also take it upon you to become familiar with the Greek.” In the summer of 1460 Galeazzo had insisted that his sister was only starting a new study that would bring great fame to the Sforza house, whereas Lascaris seemingly frames it in his dedicatory letter as a study already underway. Ippolita Sforza is said to be “taking delight” (oblectari) in Greek literature at his time of writing. The phrasing throughout the letter suggests that with his dedication Lascaris was spontaneously applying for the position of Sforza's private tutor in Greek. Perhaps he aspired to continue earlier Greek studies of hers—which might have been supervised by someone like Martorelli, Filelfo, or Kastrenos—and to support them with a better handbook than previously available. This interpretation, if correct, might suggest a dating for the Paris manuscript closer to 1463 than to 1465, since it was also in 1463 that Lascaris was appointed public professor of Greek in Milan. The earlier dating would also fit in with Lascaris's lack of confidence to write in Latin in the dedicatory letter, and with the fact that he was still seeking to secure Sforza patronage through Ippolita. The prominence of the modesty topos throughout the letter, especially its second half, seems to further support this analysis.

There is a second argument suggesting that Sforza might have been profiling herself as a patron in her later Milanese years. It is a fact that even in the often dire circumstances at the Neapolitan court, she tried to be a patron for scholars and artists after the example of her mother Bianca Maria Visconti in Milan—a dream she could not entirely realize because of financial problems, although quite some vernacular literary works were dedicated to her at her new home.Footnote 79 A lack of money might be one of the reasons, in addition to other bad experiences in Naples, that in 1466 Lascaris left his position there after only a year, thus effectively ending his close connection with the Sforza family. The émigré described his distaste for Naples as follows: “As soon as I hear about ungrateful Naples, I take flight. For I have been through a lot. . . . Naples is no longer the colony of the Chalcideans and Athenians, the school of Greek literature, to which the Romans came running. All is gone and changed.”Footnote 80 Like Lascaris, Mombrizio was trying to keep close ties with the Sforzas. As mentioned above, his verse translation was not the only work he dedicated to a Sforza. Moreover, Mombrizio's dedicatory verses contain a lengthy encomium on the Duke of Milan and his family, who is hailed for his success in attracting learned Greeks to Milan after their suffering at the fall of Constantinople.Footnote 81 Two passages in particular are marked in the margin as pertaining to Francesco Sforza, both relating to the duke's successful headhunting of learned Greeks.Footnote 82

In conclusion, it seems that Ippolita Maria Sforza was envisaged not only as a pupil but also as a patron of Greek studies, both by Lascaris and Mombrizio, who wanted to exploit the princess for their own career advantage. Indeed, whereas Lascaris's manuscript gift was suitable for language-learning, Mombrizio's clearly was not, seemingly being devised as an honorary present rather than as a didactic tool, as I illustrate below. Sforza herself seems to have welcomed the learning of Greek with open arms, not only out of a sincere interest in the Greek heritage but no doubt also to promote herself as a cultivated noblewoman destined to become queen in a kingdom with a rich Greek history. Studying Greek and fostering Greek learning helped her materialize the Sforza ideology of the educated ruler and gave extra weight to her cultural and intellectual capital, which she could exploit at her Neapolitan court in her numerous diplomatic and patronage relationships at the crossroads of the Duchy of Milan and the Kingdom of Naples.Footnote 83

TRIANGULAR TEACHING? SFORZA BETWEEN LASCARIS AND MARTORELLI

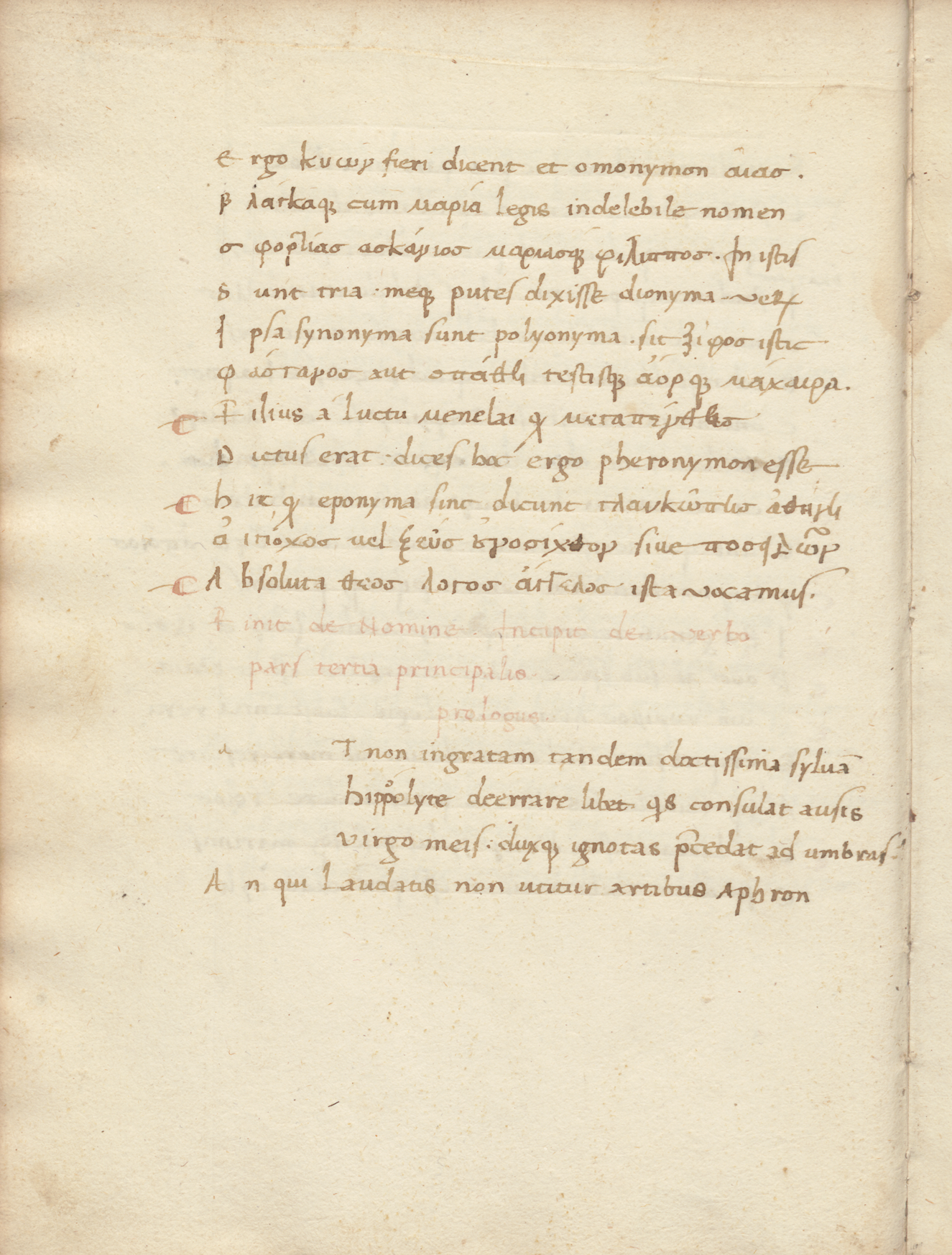

Do the Greek grammars dedicated to Ippolita Sforza reveal any material traces that she studied Greek? This question does not allow for a categorical answer, but calls for a meticulous analysis of the sources, especially Lascaris's autograph manuscript with its Latin annotations, since Mombrizio's Latin verse translation seems to have never been finished or presented to Sforza. The question, then, amounts to whether Sforza used the Paris manuscript to learn Greek. The short answer is that it is highly likely but impossible to know for sure. For a longer and more nuanced answer, the third page of Greek text offers a neat starting point:

And this goes on for another fourteen moral adages. I can be clear about the status of the two outer columns: on the left, I have reproduced Lascaris's Greek autograph, and on the right, I offer an English translation. But what is the Latin in between? These are the word-for-word translations of the Greek sayings present in the manuscript, the authorship of which has not yet been the subject of any scholarly study. Large portions of the manuscript contain such translations, especially in the beginning and at the end, most often interlinearly but also in the margins. They serve to make both the Greek examples and the grammatical metalanguage understandable to a student reader. The pages lacking any Latin translations usually contain long lists of paradigms, where the meaning of the words is already known. Looking at the eighty-eight pages (forty-four folios) of the Paris manuscript, Latin translations are lacking on twenty-nine of them.Footnote 85 In other words, two out of three pages are annotated in Latin.

The presence of verbatim Latin translations in a Greek manuscript points to its use in a teaching context, an observation repeatedly made in existing scholarship, most recently and convincingly by Federica Ciccolella.Footnote 86 I argue not only that these Latin annotations are more or less coeval with the production of the manuscript but also that they reflect Greek teaching from that time, most likely even by Lascaris to Sforza. Yet they must not have been alone in their classes, since it is not their Latin handwriting found in the Paris manuscript, as a comparison with autograph documents suggests.Footnote 87 Sforza's handwriting in the 1460s resembles that of the notes more closely than that of Lascaris; however, it seems they were authored not by her but by her teacher Baldo Martorelli, whose hand she seems to have closely imitated.Footnote 88 In other words, the interlinear and marginal annotations appear to reveal that Sforza studied Greek with Lascaris under the supervision of her trusted local teacher and secretary Martorelli, a Milanese citizen and a native of Serra de’ Conti in Central Italy, not far from Ancona.

There are other options for interpretation, although less likely ones. It is, for instance, possible that Martorelli taught Sforza Greek by means of Lascaris's manuscript. Martorelli, himself a former student of the Hellenist Vittorino da Feltre at his Casa Giocosa in Mantua, and a friend of Lascaris's rival Filelfo, probably knew Greek himself. Perhaps Lascaris had delivered the perfect tool to Martorelli, who no longer needed him, although the fact that Lascaris traveled to Naples around the same time as Sforza and Martorelli does suggest that they collaborated in a kind of didactic triangle. Moreover, the available evidence indicates that Martorelli was acquainted with Greek only superficially, and perhaps not enough to teach the language autonomously.Footnote 89 A third possibility, which cannot be fully excluded but seems implausible for similar reasons, is that Martorelli used the presentation copy of Lascaris's grammar to maintain his own Greek grammar knowledge in his spare time.

It seems therefore most plausible that Lascaris explained Greek grammar to Sforza by translating the Greek in his autograph manuscript into Latin with the help of Martorelli, who wrote a word-for-word translation as well as some of the more difficult letters of the Greek alphabet. However, there is the possibility that not Martorelli but Sforza practiced her Greek writing, although the ink of the Latin translations and the Greek letter exercises does seem to be the same, which would favor Martorelli as the writer of these practice letters. Perhaps he showcased to Sforza how the letters needed to be drawn. Or did he briefly pass her his pen, allowing her to exercise her Greek writing? The following excerpts (figs. 1–2) may suffice to illustrate the written result of the presumed triangular teaching between Lascaris, Martorelli, and Sforza.

Figure 1. Detail of Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF), Paris, grec 2590, fol. 3r. Constantine Lascaris, Ἐπιτομὴ τῶν ὀκτὼ μερῶν τοῦ λόγου, ca. 1463–65. © BNF. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 2. Detail of BNF, grec 2590, fol. 3v. © BNF. Reproduced with permission.

The triangle would have been a win-win situation for all parties: Lascaris taught Greek to Sforza under the guidance of her Latin teacher Martorelli, which would have allowed the Greek scholar to further polish his own Latin (a precious skill for a young and ambitious migrant intellectual in Renaissance Italy) and to gain the favor of the Sforza family. It would fit Sforza's standing and practice that Martorelli annotated the copy for her as a method of explaining the challenging subject of Greek grammar. Indeed, Sforza had Martorelli and her later secretary Giovanni Pontano write down many letters and other documents for her.Footnote 90 A comparison of Martorelli's Latin hand with that of the Latin annotator of the Paris manuscript illustrates that Sforza and Martorelli must have extended this practice to learning Greek, in order to render this didactic experience as comfortable as possible, enabling her to understand many of the Greek words and terms in Lascaris's grammar.

So Sforza is very likely to have studied Greek with Lascaris under Martorelli's guidance, but one final question remains. Did the teaching occur in Milan between ca. 1463 and 1465, or when she was already in Naples, from late 1465 to 1466? There is not enough evidence to definitively solve this issue, but seeing that Kastrenos was involved, and that Mombrizio mentioned in his dedication that Lascaris was Sforza's teacher, the tutoring must have started when they were still in Milan:

And hence, when I think about the past time by myself, and about the lost days, why oh why, most learned Lascaris, would you put off your arrival in our city?

Jupiter made you our teacher and had you guide the new people toward Greek books. With you as guide he settled the Academy in these lands, so that the Insubrian [Milanese] land would cede in nothing to the Attic world [Greece]. Here he was, Ippolita, whom you, although unknowingly, once wished for. The stars have favored just desires. The first results of his work are with you, he who saw that you were so worthy that he rightfully dedicated his firstling to you.Footnote 91

Be that as it may, the triangular teaching may have continued for a short while at Sforza's studiolo in Naples, since all three of them (Sforza, Lascaris, and Martorelli) relocated to this city at some point in 1465. But the new conditions there precluded her from continuing her studies with the same intensity as she had done in Milan, leading to her eventual abandonment of Greek studies.

There are other indications that the Paris manuscript was intended for student use. The manuscript opens with some basic reading texts: two prayers and the moral sayings mentioned above.Footnote 92 Granted, it has a lavish initial and some other decorations fitting for a princess, but the work was in the first place a schoolbook and not a luxurious display of cultural and economic capital like the copy of Lascaris's grammar dedicated to Sforza's nephew Gian Galeazzo (1469–94), the sixth Duke of Milan.Footnote 93 Contrary to the Paris manuscript, this exuberantly decorated copy, preserved in Milan, shows no traces of classroom use.Footnote 94 There is, of course, a chronological distance between the two manuscripts. Lascaris's grammar book for Ippolita Sforza was written in the first half of the 1460s, when Lascaris was in his late twenties, trying to get into the grace and patronage of the influential Sforza family, in collaboration with a companion in adversity, Demetrios Kastrenos. Aside from wanting to produce a schoolbook, they might have been short on money, precluding a luxurious decoration of the manuscript. More than ten years later, Lascaris, by then an established scholar, was probably working at the request of the duke himself, judging by the colorful execution of the manuscript, which also contains allusions to the duke's mother, Bona of Savoy, to whom Mombrizio had dedicated a work.Footnote 95

Like the manuscript for Gian Galeazzo, Mombrizio's Latin verse translation of Lascaris's grammar also seems to have been more a token of cultural and economic capital than a real schoolbook. It bears no traces of student use, and gives the overall impression of being an unfinished product, seemingly written with ever more haste as one advances through the folios. In addition, the text stops quite abruptly on folio 41r, without any explicit. The only traces of use are some interlinear and marginal annotations, mostly summaries or corrections, and three unrelated scribbles on folio 42v of an amorous, grammatical, and moral-philosophical nature, suggesting that the manuscript was used as scrap paper.Footnote 96 The final pages of the Milan manuscript furthermore offer a more extensive chapter on accents than Lascaris's Paris manuscript.Footnote 97 This and other differences, some of which are mentioned by Raschieri, suggest that Mombrizio translated Lascaris's grammar from a copy other than the Paris manuscript, which was probably already in Sforza's possession and could not serve as Mombrizio's exemplar.Footnote 98

IMAGINING SFORZA AS A STUDENT OF GREEK

Not only did Ippolita Maria Sforza study the Greek language and gain competence in it, as I have been arguing, but Lascaris and Mombrizio also clearly imagined her to be capable of doing so. There is excellent evidence for this in the two grammar manuscripts. These works provide plenty of information on how the grammarians envisaged Sforza as a learner of Greek, both in the dedicatory letters they addressed to her and through the methods of linguistic, literary, and visual presentation they adopted. What discursive and formal strategies did they work out to tailor the subject matter to a noblewoman with humanist Latin schooling? How did they address Sforza? Which layout choices did they make in service of their high-born pupil?

The annotations in the Paris manuscript provide a clue as to the method with which Sforza's tutors envisaged to teach her Greek: Latin, a language she had gradually gained competence in during the 1450s, was the main gateway, as it was for all Western students of Greek, male and female.Footnote 99 In particular, Latin translation was thought to be the key, as suggested not only by Martorelli's annotations but also by Mombrizio's ambitious project of translating Greek grammar into Latin verses. Mombrizio highlighted the importance of the Western language of learning in the liminary verses accompanying his grammar:

Anyone of you will indeed be able to learn Greek grammar without me, but without me it will not be easy. . . . I do not believe that there will be any tedium in Latin words, because the daughter language loves its motherly sound. . . . So we attracted youngsters with such plans, and we joined Greek mouths with Roman lips.Footnote 100

Latin was an apt gateway because it was a daughter language of Greek, and their sounds were akin. Mombrizio further explained the role of Latin by means of a Lucretian metaphor: the bitter medicine of Greek grammar is best consumed with honey, in this case the use of Latin in Greek teaching, and the use of didactic poetry.Footnote 101 Indeed, Mombrizio was a late humanist proponent of a medieval tradition of grammar versification, which reached its height of popularity in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, and he claimed—rightly so, it seems—to have been the first to translate Greek grammar into Latin verses.Footnote 102 His motivation to do so transpires from his address to the reader: poetry helped better than prose to commit knowledge to memory, because it ordered grammatical information into palpable pieces.Footnote 103 Mombrizio reunited medieval and humanist tastes in other ways as well. On the one hand, he compiled an extensive hagiographic work called Sanctuarium, which he refrained from adapting to humanist stylistic tastes. On the other, he translated Hesiod's Theogony into Latin.Footnote 104

In a sense, the two Greek grammars dedicated to Ippolita Sforza are compatible, since the Paris manuscript contains many Latin glosses of Lascaris's grammatical examples and to a much lesser extent of Greek grammatical metalanguage, whereas the reverse is true of the Milan manuscript, where one finds Greek paradigms explained in Latin metalanguage. In the sections on the accidents of the nouns in the two manuscripts, these approaches look as follows (figs. 3–6). In Lascaris's original, these sections are placed after the section on the verb; in Mombrizio's translation, before it, probably to enhance coherence by putting it together with the rest of the section on the nouns.

Figure 3. BNF, grec 2590, fol. 39r. © BNF. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 4. BNF, grec 2590, fol. 39v. © BNF. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 5. Biblioteca Ambrosiana (BA), Milan, Ambrosianus N 264 sup., fol. 17v. Constantine Lascaris, trans. Bonino Mombrizio, “Grammatica Græca a Bonino Mombritio uersibus et idiomate Latino conscripta,” ca. 1465. © BA. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 6. BA, Ambr. N 264 sup., fol. 18v. © BA. Reproduced with permission.

In the Paris manuscript (figs. 3–4), both metalanguage and examples have been translated into Latin: for instance, προσηγορικὰ → “appellatiua” (appellative nouns) and παρθένος → “uirgo” (maiden), with translations of examples dominating. In a sense, the manuscript could serve as a primitive Greek-Latin dictionary; in the chapter on the noun, there is even an entire list of Latin translations of Greek imparisyllabic nouns.Footnote 105 Mombrizio, in turn, adopted a double strategy for metalanguage, sometimes translating it literally into Latin, as with “appellare” (reflecting Lascaris's προσηγορικὰ) and “impositum” (Lascaris's ἐπίθετα), at other instances borrowing the Greek term, as with “dionyma” (Lascaris's διώνυμα) and “pheronymon” (Lascaris's φερώνυμα). As a rule, the Greek examples have not been translated in Mombrizio's verse grammar, so that users of the manuscript would have required a teacher in order to understand the meaning of these words and build up their vocabulary.

Mombrizio's greater flexibility in dealing with metalanguage is no doubt due to the poetic register, whereas in the Paris manuscript renderings in established Latin metalanguage are preferred, and borrowings from the Greek are avoided, as seems to have been customary in the early stages of Greek grammaticography in Renaissance Western Europe.Footnote 106 This purist attitude was stimulated by humanist ideas on classical Latinity and Ciceronianism, as well as by the firmly established tradition of Latin grammar and its terminology, with which the Paris annotator Martorelli was surely familiar. It cannot be entirely excluded here that it was also part of Lascaris's integration strategy; he wanted to avoid estranging his pupils by using unfamiliar grecizing words in his courses, which he as a rule held in Latin.

Overall, Mombrizio's attempt at versifying Greek grammar in Latin hexameters can, with Raschieri, be accused of “didactic inadequacy.”Footnote 107 By describing Greek grammar in often obscure Latin verses, with untransparent exemplification offering only the Greek original and no Latin translation, Mombrizio's work would have scared Ippolita Sforza into dropping Greek more than it would have encouraged her to pursue the topic. Mombrizio omitted Lascaris's sections on the Greek alphabet and other introductory paragraphs on the syllable, the word, speech, the noun, gender, noun kinds, number, case, and accent, as well as the brief elementary texts prefixed to Lascaris's grammar.Footnote 108 This omission can have several reasons. Most probably, Mombrizio found it too difficult to versify these parts, or perhaps he knew that Lascaris and Sforza had already treated these topics in their courses when he started his verse translation project.

In conclusion, Mombrizio's unique project of versifying Greek grammar proved too ambitious and probably missed its didactic goal. Even if it was ever finished and presented to Sforza, it seems unlikely that she relied on this text to refine her Greek competence. The only use I can see for it is that she would use some parts of the text to memorize certain declensions, rules, and examples, but this would only make sense after one or more rounds of teaching by Lascaris on the subject and under the supervision of Mombrizio himself. Otherwise, the hexametric cocktail of Greek grammar would have had as mind-numbing an effect on the student as it has on the modern reader, at least on this one.

Vivien Law makes the good point that the verse format served to order the subject materials for Latin grammar students, usually morphology and lexicon rather than syntax, as an alternative to visual aids. However, by Mombrizio's time of writing, the popularity of verse grammar had largely waned, giving way to diagrams, tables, and other means of visual presentation.Footnote 109 Mombrizio's Greek verse grammar is an excellent example of why the genre was abandoned: it too often resulted in incomprehensible verses, and ran the risk of confusing the students more than helping them. An anonymous author of a Latin syntax treatise in the fifteenth century, cited by Law and referring to Alexander de Villadei's hugely popular Doctrinale, aptly voiced this visual turn: “Since the rules of government and construction conveyed by Alexander in verse are incomprehensible to beginners, I decided to come to their rescue, so that what is so foggily presented in verse <will be set out> in prose and with diagrams as far as my abilities permit.”Footnote 110 In Greek teaching, too, visual aids would become the number one mnemonic device, with verse outlines being rare (though not nonexistent) throughout the early modern period.Footnote 111 One should not, however, forget that Latin verse grammars such as Villadei's were not superseded overnight. Indeed, at the Sforza court, the Doctrinale circulated, as evidenced by the fact that Baldo Martorelli followed it with his prose Latin grammar for Galeazzo and Ippolita Maria Sforza, and the fact that a manuscript copy of the Doctrinale, now preserved in Vienna, was produced for Bianca Maria Sforza (1472–1510), Ippolita Sforza's niece, around 1478.Footnote 112

Visual structuring is a technique that Lascaris, too, applied in his grammar book for Sforza, albeit rudimentarily. He inserted paragraph marks, rubrication—now largely faded—and marginal summarizing notes to help the student browse through the work. For instance, in the presentation of the Greek article, the alternation of black and red ink serves to distinguish the names of cases from the actual declension of the article (fig. 7).Footnote 113 Also, in the list of imparisyllabic nouns, mentioned above, each lexical item has its own line, starting with the article in red ink. Verb paradigms have a rubricated initial for each form of the verb: active present indicative, active imperfect indicative, and so on.Footnote 114

Figure 7. The prepositive article in BNF, grec 2590, fol. 4v. © BNF. Reproduced with permission.

All in all, of the two humanists, Lascaris seems to have been the better didact. There is, however, one aspect of Mombrizio's work that would have appealed more to Sforza than its equivalent in Lascaris's manuscript. In his choice of exemplification, the Italian humanist was more daring than his colleague of Greek extraction. Mombrizio tried to domesticate this element of his verse translation by offering examples tailored to his addressee, a procedure that Martorelli had already followed in his Latin grammar manuscript.Footnote 115 By the metaphor of domestication I mean the integration of Greek studies with the living environment of local students and scholars, where a relationship of interdependency existed. Just as a much more tangible good, the potato, was imported to Western Europe and became incorporated into local gastronomical cultures, Greek heritage became integrated and sustained in a Western context in order to preserve and reproduce it, restoring it alongside the ancient Roman heritage in a classical symbiosis.Footnote 116 At first, this interaction also involved non-Western human actors from the Byzantine Empire, as with Lascaris, but gradually became a more one-sided relationship where the domesticator (the Western scholar) adopted the domesticate (the Greek heritage) as part of their own identity. The domestication process involved generations of intellectual experiments and modifications, gradually resulting in new uses of Greek heritage and developing into Hellenisms sui generis—a wide range of idiosyncratic mixes of ancient Greek and early modern culture and thought.

As an example of Mombrizio's early domestication of Greek, I can mention the fact that he consciously introduced more female examples than Lascaris had done in his traditional migrant-Byzantine work. My discussion will be based on the two excerpts showcased above (figs. 3–6), on the classes of nouns, which provide a very interesting case study. To start with, the choice to replace Lascaris's example of the Greek god “Phoebus Apollo” (Φοῖβος Ἀπόλλων) by the goddess “bright-eyed Athena” (γλαυκῶπηςFootnote 117 Ἀθήνη) might not necessarily have been a strategy to adapt the subject matter to Sforza's gender but a matter of meter.Footnote 118 However, this can hardly be said about the following verse when compared to Lascaris's original:

Mombrizio: Adque aliud θυγάτηρ δούλη δέσποιναque dices.Footnote 119

Lascaris: τὰ δὲ πρός τι οἷον πατήρ, υἱός, δοῦλος, δεσπότης.Footnote 120

In his examples, Mombrizio substituted the Greek nouns for “father,” “son,” “slave,” and “master” by words for “daughter,” “female slave,” and “mistress.” The humanist's tailoring of the subject matter to Sforza's frame of reference went even further, as he introduced a new category of “absolute nouns,” absent from Lascaris's original: “We call those nouns—‘God,’ ‘Word,’ ‘angel’—absolute.”Footnote 121 These three words referred to core entities of Christianity, in particular the New Testament and the first chapter of John's gospel, which she might have read in the original Greek, as it was part of her dowry. Was Mombrizio capitalizing on Sforza's oft-praised piety and, perhaps, also subtly referring to her Greek readings? Whatever the case, it is clear that he sustained the image of the princess as a godly woman by adapting his examples to her environment. The moral sayings included in Lascaris's original suggest that he, too, was invested in the moral integrity of his pupil, even though moral readers were by no means restricted to female students.Footnote 122 In other words, these grammar books reveal the stereotypical picture of Sforza as a pious and virtuous woman, an image made explicit by Mombrizio in the extensive prologue to his discussion of the Greek verb, where he imagines himself as her guide in the “forest” (sylua), “labyrinth” (labyrinthus), and “desert” (heremus) of the Greek verb.Footnote 123

The last example of domestication I want to cite is the clearest one. It again concerns the section on noun accidents, in a passage in which Lascaris discussed the concept of dionymous nouns, a grammatical term referring to persons with two names. Lascaris exemplified this concept by means of “Alexandros” and “Paris,” two distinct names referring to the same Trojan prince from Homer's epic poems. In his verse grammar, Mombrizio substituted these names with references to members of the Sforza family: “And you read Bianca with Maria, an imperishable name, Ascanio Maria and Filippo Maria Sforza. In these there are three, and you would think I had said two-named words.”Footnote 124 The idea seems to be that many members of Ippolita Sforza's close family, including herself (Ippolita Maria Sforza), her mother (Bianca Maria Visconti), and two of her brothers (Ascanio Maria and Filippo Maria Sforza), had two first names. All these persons’ first names consisted of two names that are usually used together. Mombrizio's example might suggest that he played with the double meaning of the Greek term διώνυμος, which in antiquity also meant “named together” outside the context of grammar. Whatever the exact meaning of this obscure passage, Mombrizio's far-reaching domestication of Greek grammar for Sforza is clearly evident here.Footnote 125

The final question I want to address here is: To what extent was the teaching method envisaged for Sforza different from male-focused approaches? The issue of exemplification in Mombrizio suggests that there was at least some difference, but does a global assessment reveal any fundamental divergences? First of all, Mombrizio mentions the topos of the difficulty of Greek, when discussing the phenomena of contraction and crasis.Footnote 126 But its difficulty is unrelated to the learner's gender, and the topos frequently appears in texts tailored to a male audience as well.Footnote 127 Second, the use of Latin as a metalanguage is in itself not gender-specific either, although usually the students had to do the work themselves: that is, to note down the teacher's oral explanations. Sforza, however, is served hand and foot by her teachers. Mombrizio wrote his Latin verse translation for her, and Martorelli provided her in the Paris manuscript with a word-for-word translation both between the lines and in the margins. This interpretive service provided by her teachers seems to have been motivated more by Sforza's status and the private setting of the courses than by her gender.

Some terminological choices Mombrizio made might be interpreted as stronger gendered language than was customary in early modern grammar. To refer to the first two of the five grammatical genders of Greek, masculine and feminine, the Italian humanist could not use the traditional terms masculinus and femininus. The cretic sequence at the beginning of these words did not allow them to be inserted into his hexameters. Instead, he opted for adjectives such as femineus (spelled foemineus), “feminine,” and muliebris, “womanly,” and circumlocutions with mas, “male”—a practice that might strike the reader as odd grammatical language, dejargonized even. I have not been able to find a gender bias in Mombrizio's uses of these grammatical terms, which are about as controversial here as they are in other grammars, then and today. One could be tempted to claim that this nontraditional metalanguage might have sharpened the reader's sense of the binary distinction between male and female giving shape to the real, nonlinguistic world. This interpretation is more daring than the evidence allows, especially since the Greek grammatical tradition did not work with a binary distinction, or even a threefold one into masculine, feminine, and neuter. Their system also included the genders κοινός and ἐπίκοινος, referring, respectively, to words that can have two genders (e.g., ὁ and ἡ ἄνθρωπος, “(wo)man”), and to words that, although having one grammatical gender, designate two biological sexes (e.g., ὁ ἀετός, “eagle”). The system of gender in Greek grammar, therefore, was not as sexually binary as it would become in later grammatical traditions of vernacular languages such as French.

A final notable feature of Mombrizio's language for grammatical gender is that he was not afraid to meddle with the traditional order of gender presentation: in his verses, feminine forms sometimes preceded the masculine, but such choices were undoubtedly more metrically motivated than a revolutionary treatment of grammatical gender promoting the feminine.Footnote 128 In sum, Mombrizio's treatment of grammatical gender seems unbiased with regard to gender and sex in the extralinguistic world, and its oddities should be ascribed, in the first place, to the poetical medium of his work—the use of emphatic and figurative language typical to poetry—rather than to underlying biases. The same cannot be said of Ponticus Virunius's slightly later discussion of the Greek declensions, which “swarm[s] with lively metaphors.”Footnote 129 Revealing for Virunius's assumptions about female temper is his discussion of feminine nouns: “In the second declension only female nouns are declined. For the women are angry with the men, because the men threw the women out of the first declension, saying, ‘Let no female cross our threshold.’ And the women say, ‘No men allowed here. Procul ite profani.’ But they steal their husbands’ endings.”Footnote 130

Stronger proof for gender stereotyping can be found in the way Lascaris and Mombrizio conceived their female student-patron as a passive recipient of their teaching. Again, Mombrizio provides the most interesting evidence. In the opening lines of his grammar, he commands Sforza as follows: “So learn from this what the Greek grammatical rules teach, Ippolita, and lend me your apt ears in silence.”Footnote 131 It seems that Mombrizio envisaged Sforza as a passive learner, who would listen in silence and do no more than that, a common idea in fifteenth-century Italian female decorum.Footnote 132 The abundance of imperatives suggests that Mombrizio imagined his student as undergoing his current of commands under his obligation.Footnote 133 He was Sforza's guide and beacon in the labyrinth of the Greek language. He also knew her wishes, of which she was not conscious herself—namely, to have Constantine Lascaris as her teacher of Greek.Footnote 134

Then again, the image of a passive student was certainly not limited to women in the Renaissance. Male students, too, were typically viewed as being on the receiving end of the one-way transfer of knowledge from professor to pupil. The difference with the case of Sforza is that Mombrizio seems to have emphatically construed an image of the princess as a passive learner, who is not required to take notes nor do anything other than listen. The teaching of Lascaris and Martorelli seems to confirm this image, since it was not Sforza who made her hands dirty with ink but her two tutors—Lascaris, while composing his grammar manuscript, and Martorelli, while making notes for her. In other words, although Sforza had occasionally done some scribal work as part of her education, in 1460s Italy this craft was still regarded in part as lowly handiwork, not entirely fit for a princess and not yet “an essential humanist skill,” as it would be to Erasmus only a few decades later.Footnote 135 It is, therefore, not surprising that a substantial part of her letters was written not by Sforza herself but outsourced to her secretaries, including Martorelli.

In conclusion, from Lascaris's and Mombrizio's grammar books for Ippolita Sforza, no clear method for teaching Greek to women emerges. Sforza was supposed to study Greek through Latin, as was common in the Quattrocento, combining grammatical studies with basic reading exercises involving approved excerpts of religious and moralizing texts. Unlike Latin teaching, this inductive approach was widely applied to Greek—which was always learned after Latin, since much of the grammatical theory was the same, or highly similar, for both languages. Her reading does, however, seem to have been rather limited, focused on the New Testament, prayers, and moral sayings. In addition, unlike most male students, Sforza apparently did not study the language in group lessons, instead receiving private courses from her teachers. This practice was certainly not restricted to noblewomen. More generally, private teaching was the prerogative of the nobility, regardless of gender. Even though it is impossible to identify a distinct method for teaching women, it is nonetheless clear that the two Hellenists, especially Mombrizio, tweaked a number of details in their handbooks in order to make them more suitable to the young noblewoman, tailoring exemplification to her environment and imagining her as a passive recipient of Greek grammatical knowledge.

CONCLUSIONS: SFORZA'S PRIVATE HELLENISM

In her biography of Ippolita Maria Sforza, Maria Nadia Covini characterizes the Milanese princess as follows: “But more than an intellectual, Ippolita was a cultured and sensitive princess, capable of putting to good use the education she received, which was aimed more at political praxis than literary culture.”Footnote 136 Sforza expressed a sincere interest in Latin and Greek language and literature, fostered by her humanist teachers. In the end, though, she had to spend most of her time on political and family affairs, being married as a scion of the influential Sforza family to the son of a mighty Southern Italian king. In this sense, her interest in Greek, variously documented but probably never followed far through, seems to confirm this image of a cultured rather than an intellectual woman, a phenomenon typical of the upper echelons of Quattrocento Italian societies, especially in the North. Sforza pursued a humanist education at the instigation of her parents, in a courtly context where a marriageable and pious daughter with good schooling was valuable cultural and political capital.Footnote 137 Consequently, she probably knew the language less well than other educated women of the Quattrocento, such as Nogarola, even if she continued her humanist education after her move to Naples.

Ippolita Sforza's grammar studies were followed by rhetorical and moral-philosophical education, thus providing a counterexample to Joan Gibson's hypothesis that women's education in the Renaissance was often restricted to grammar in order to keep women silent.Footnote 138 This now widely contested hypothesis was based in part on the fact that Renaissance women writers did not compose many works on rhetoric and philosophy, but this is not the best evidence to assess the coverage of women's education. Student notes and handbooks tailored to women students are far better touchstones in this regard, as my case study has endeavored to illustrate. Even so, Sforza's Greek trajectory does seem to have stalled at the grammar and basic reading level, and she was imagined to be a silent and passive pupil by her teachers, explicitly so by Mombrizio. Nonetheless, the fact that she had access to a Greek gospel manuscript and perhaps read the New Testament in this language is quite remarkable for the mid-1460s, since only few Western scholars had at that time gone back to the original Greek text, favoring instead the official Latin Vulgate version. With Lorenzo Valla and Giannozzo Manetti, both of whom worked at the Neapolitan court in the 1440s and 1450s, she was in good company, even though her engagement with the Greek Bible did not reach the same level of meticulousness and detail as these earlier Italian humanist textual critics and translators, to say the least.Footnote 139

Sforza was able to profile herself as a pioneering and promising student of Greek in the 1460s, or at least to attract two scholars who thought of her that way. Her interest in Greek was widely praised, and apparently not perceived as transgressive, perhaps because she restricted it to her private quarters and to a passive engagement focused on religious texts. Her Greek studies mainly served to strengthen her cultural-intellectual capital and increase her attractiveness as a patron for intellectuals and artists in view of her role as future queen, even though she did not live to ascend the throne. The passive, private, and auxiliary nature of her Hellenism might also explain why there are so few material traces of her Greek studies, which she did not flaunt in public.