Introduction

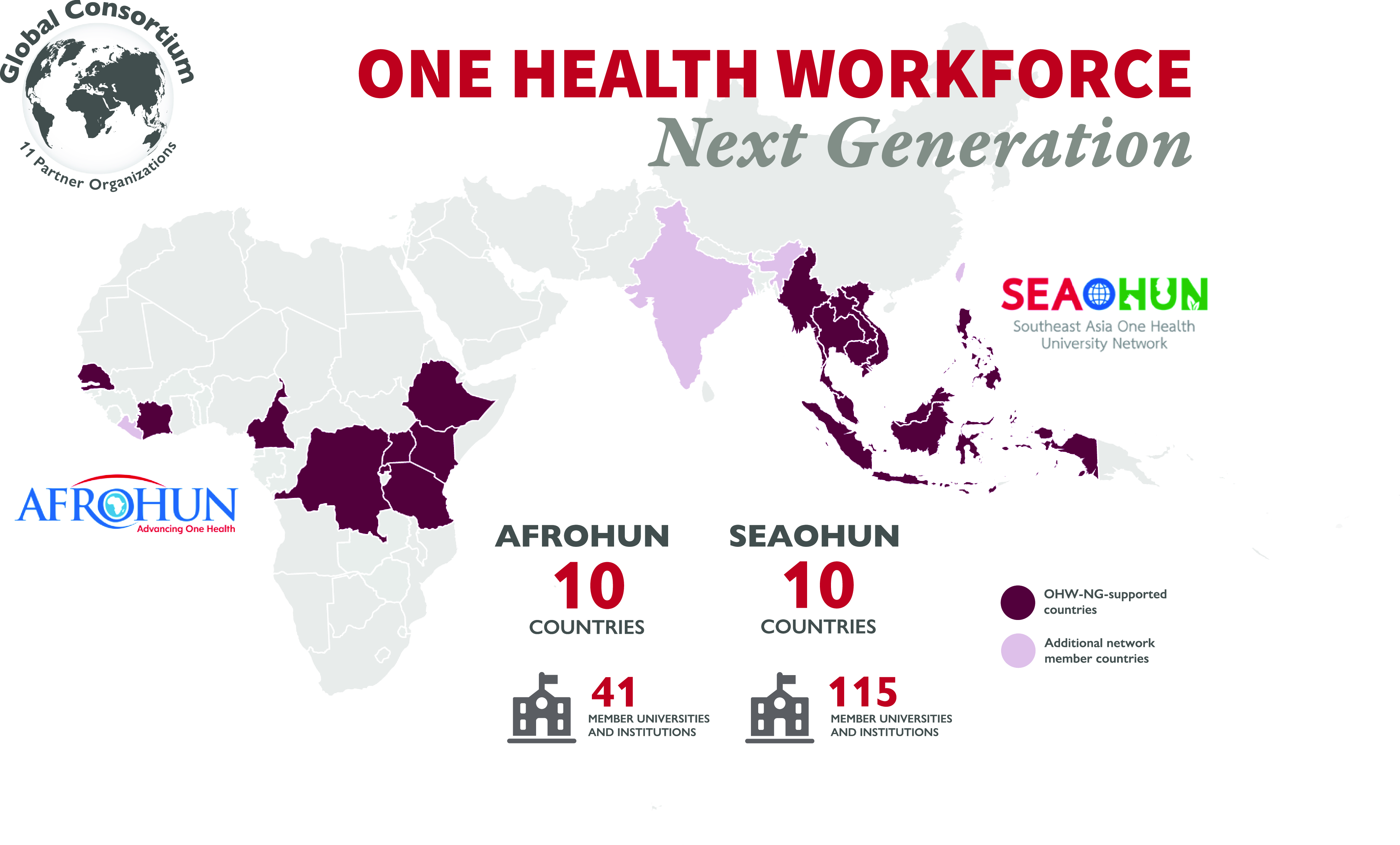

University networks are uniquely situated to contribute to the development and strengthening of a One Health Workforce. Globally connected, university networks harness the collective power of their faculty and staff expertise, innovative potential, student enthusiasm and infrastructure resources to inform policy makers, catalyze multidisciplinary partnerships and represent local stakeholders. A vision and product of the USAID-Emerging Pandemic Threats division, the One Health University networks, consisting of the African One Health University Network (AFROHUN, formerly OHCEA) and the Southeast Asia One Health University Network (SEAOHUN), have a track record of achievements focused on training, educating and empowering international human resources across domains that have often been under-resourced, creating a reinforced transdisciplinary workforce that is critical for achieving global and national health security. This effort has benefited from visionary leadership, dedicated One Health champions and a consistent investment of resources. Fifteen years in, the networks are an established, trusted regional resource working alongside others to train a One Health workforce capable of responding to global health challenges. Now representing over 120 universities in 17 countries across Africa and Southeast Asia, since 2010 AFROHUN and SEAOHUN have trained more than 85,000 individuals, representing faculty, staff, students, health care workers and in-service professionals (See Figure 1). Rooted in One Health core competencies, training modalities span the spectrum of online, hybrid, in-person, residential and experiential learning. Peer exchange, south-south capacity building, communities of practice and locally adapted curricula and teaching practices have helped connect stakeholders, transcend traditional classroom applications and foster knowledge exchange while simultaneously building skills, extending professional networks and advocating for transdisciplinary approaches to health challenges. As the networks have matured, these efforts have also translated to helping countries improve national capacities related to international health regulations, while simultaneously training current and future generations of OH practitioners.

Figure 1. Member countries represented across AFROHUN and SEAOHUN. A global consortium of 11 different organizations provided leadership and technical support over the project period. A full list of network member institutions and the global team are available at https://ohi.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/programs-projects/one-health-workforce-next-generation.

As the current funding cycle supporting the One Health Workforce – Next Generation Project (OHW-NG) comes to a close in 2025, it provides a natural opportunity to take stock of the last 15 years of USAID-funded One Health University networks and to reflect on their power and potential to contribute to global health security through training One Health practitioners. What has emerged from a decade and half of work are key lessons and takeaways for existing and prospective networks dedicated to One Health, Planetary Health and complementary disciplines. The following commentary, compiled through literature review, first-hand accounts and experience from the authors illustrates key historical moments of the Networks, framed by global events and milestones in the evolution of the One Health approach at a global scale, describes current perspectives on core competencies for One Health teams and practitioners, summarizes the pedagogical frameworks that have informed OHW-NG content generation, highlights impactful network activities, illustrates the importance of OH Champions and suggests options for future directions for OH university networks.

Defining the “One Health Practitioner”

While One Health as defined by the United Nations Quadripartite is now broadly accepted, the concept of One Health in practice and definition of a “One Health Practitioner” is more elusive, given the diversity of disciplines, roles and responsibilities required to address complex planetary and health challenges that extend beyond zoonotic and infectious disease response. Here, we consider One Health practitioners as members of a cross professional team equipped with diverse yet complementary technical, social and leadership skills necessary for effective collaboration and intervention (Steele et al., Reference Steele, Toribio, Booy and Mor2019). Universities, workforce education and training centers are uniquely positioned to equip learners with the knowledge, skills and core competencies for cross professional transdisciplinary problem solving and for catalyzing the potential of One Health practitioners and teams.

A history of the networks

Networks play a critical role connecting people through a medium of exchange enabling communication and sharing of information, trade, economic growth and development. The value of a network is typically analyzed by metrics and laws designed to quantify size and the impact of network connections on members and society, but which fail to adequately account for non-economic or financial “value” for network members (Scala and Demastro, Reference Scala and Delmastro2023). One Health University Networks connect member institutions both within university faculties and colleges and across national borders increasing the intellectual and institutional power for transdisciplinary collaboration necessary for tackling complex global challenges. The intrinsic value of One Health University Networks therefore, is in their capacity to bridge disciplinary silos, foster multi-sectoral collaboration, inform and drive policy agendas, engage national and subnational actors and catalyze public/private partnerships. Through networking (globally, regionally, nationally), universities grow stronger, providing the necessary foundations for training, education and even surge capacity support to address health emergencies and fill workforce gaps.

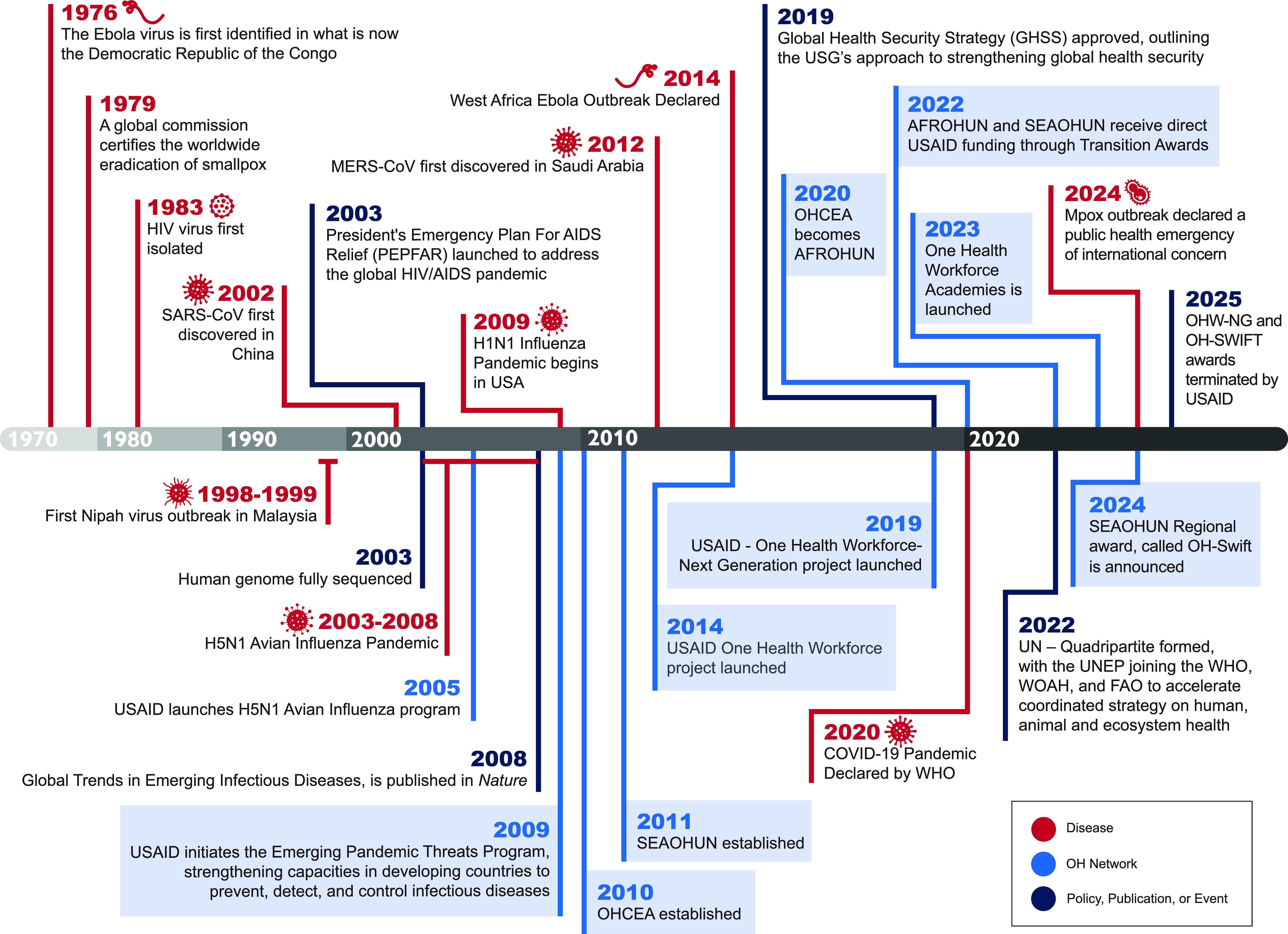

The following timeline highlights influential global events that have shaped our collective history and simultaneously informed the inception and maturation of the One Health University Networks (See Figure 2). Unravelling the historical component of the Networks, and their deep connections to, and relationships with other partners that have assisted the networks in their growth and development, is important when reviewing their history and acknowledging the visionary leadership and investment by USAID. Initiated in 2009, the Emerging Pandemic Threats program focused on mitigating impacts of high consequence zoonotic diseases, such as highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza. The EPT program built on earlier USAID experience in disease surveillance, training and outbreak response. Initially led by DAI, with contributions from University of Minnesota and Tufts University, the USAID RESPOND Project was part of the EPT portfolio of networked activities that also included programs such as USAID PREDICT-1. RESPOND activities built a strong foundation for local universities to train future leaders in the One Health approach and saw the formation of the SEAOHUN and OHCEA (now AFROHUN) networks. Following RESPOND, in 2014, the EPT-2 program launched the original One Health Workforce (OHW) Project, with leadership from University of Minnesota and Tufts University. Directly supporting SEAOHUN and AFROHUN, OHW scaled up workforce development efforts and the networks’ operational capacities. This five-year window was also a time of tremendous global effort towards improving global health security and evidence supporting the economic argument for the One Health approach, catalyzed in part from the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa and consolidation of the WHO’s International Health Regulations into a standardized Joint External Evaluation tool in 2016 (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Tappero, Ijaz, Bartee, Fernandez, Burris, Sliter, Nikkari, Chungong, Rodier and Jafari2017; Machalaba et al., Reference Machalaba, Smith, Awada, Berry, Berthe, Bouley, Bruce, Cortiñas Abrahantes, El Turabi, Feferholtz and Flynn2017). Building on this momentum, in 2019 a third round of USAID investment funded the current One Health Workforce-Next Generation Project. Led by the University of California, Davis in collaboration with AFROHUN, SEAOHUN and global partners, the OHW-NG Project saw huge gains in the numbers of professionals trained, along with continued growth and independence of the networks, with each network successfully receiving direct USAID funds beginning in 2022.

Figure 2. Timeline illustrating the development of USAID-funded One Health University Networks, contextualized with significant global health events over the last six decades. The timeline highlights key milestones in the establishment and growth of AFROHUN and SEAOHUN, aligned with relevant global health initiatives.

The current funding period for the One Health Workforce-Next Generation Project began in October 2019, meaning that project leadership quickly had to adapt to the realities imposed by the COVID-19 outbreak during its first year of implementation. The shift to online learning modalities catalyzed the development of the online One Health Workforce Academies (OHWA) platform. Aligned with One Health competency domains, this platform offers free, high quality One Health training content accessible to anyone in the world. As the world reckoned with the many challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the strength, relevance and importance of the One Health core competencies was illuminated on a global scale.

The evolution of One Health core competency domains

Over the last two decades, substantial intellectual effort and resources have been devoted to the development and refinement One Health frameworks and identification of core competency domains and competencies. A product of the RESPOND Project was the refinement of sixteen One Health Core Competency Domains considered critical for improving multisectoral workforce capacity; this work built on years of previous efforts documented by others (Frankson et al. Reference Frankson, Hueston, Christian, Olson, Lee, Valeri, Hyatt, Annelli and Rubin2016; Amuguni et al., Reference Amuguni, Bikaako, Naigaga and Bazeyo2019). These domains then informed the development of various training modules under the OHW project used by both SEAOHUN and AFROHUN (Amuguni et al., Reference Amuguni, Bikaako, Naigaga and Bazeyo2019). Adaptation to new and emerging topics have resulted in the evolution of the core competency domains that a One Health practitioner should be capable of.

As part of foundational activities related to the OHWA, in 2022 the OHW-NG technical team reviewed and updated One Health Competency Domains. This process was informed by published efforts from the EPT-Respond and OHW projects, academic publications, authors’ experiences, over a decade of curriculum development by AFROHUN, SEAOHUN and other global institutions, an extensive process of resource mapping, an eDelphi Panel, a stakeholder survey and technical review by OHW-NG Project team members (Frankson et al. Reference Frankson, Hueston, Christian, Olson, Lee, Valeri, Hyatt, Annelli and Rubin2016; Togami et al., Reference Togami, Gardy, Hansen, Poste, Rizzo, Wilson and Mazet2018; Amuguni et al., Reference Amuguni, Bikaako, Naigaga and Bazeyo2019; Ogunseitan et al., Reference Ogunseitan2022; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Ogunseitan, Epstein, Kuruchittham, Nangami, Kabasa, Bazeyo, Naigaga, Kochkina, Bikaako and Ahmad2023).

The result is an updated set of twenty domains.Organized in a logical sequence for scaffolding content and skill development, the domains are divided into two groups: Technical and Functional. Technical Domains include competencies related to the acquisition and application of discipline-specific principles and procedures essential to One Health interventions (Amuguni et al., Reference Amuguni, Bikaako, Naigaga and Bazeyo2019; Gennari et al., Reference Gennari, Bizier, Petracci and Kalamvrezos Navarro2021). Complementing the Technical Domains, Functional Domains include competencies that enhance organizational and individual effectiveness and maximize the overall impact of One Health interventions (Gennari et al., Reference Gennari, Bizier, Petracci and Kalamvrezos Navarro2021) (See Figure 3). The domains will be used to guide the refinement and organization of competencies and as such, will establish a framework for the development of curricula and evaluation strategies associated with the OHWA. The domains will be subject to periodic review by OHWA collaborators and undoubtedly, this list will continue to evolve over time in response to emerging educational needs, global priorities and advances in One Health research and implementation.

Figure 3. Diagram of 20 One Health Core Competency Domains. (* indicates a new or revised domain).

Pedagogical framework for OHW-NG competency-based education and experiential learning

The One Health approach emphasizes the interconnectedness of human, animal and environmental health, necessitating a workforce adept in interdisciplinary collaboration to solve problems. To cultivate such a workforce, educational programs must adopt pedagogies that promote active learning and practice. The OHW-NG project adopted competency-based education (CBE) that empowers learners to demonstrate mastery of specific, measurable skills and competencies (Togami et al., Reference Togami, Gardy, Hansen, Poste, Rizzo, Wilson and Mazet2018; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Ogunseitan, Epstein, Kuruchittham, Nangami, Kabasa, Bazeyo, Naigaga, Kochkina, Bikaako and Ahmad2023). These included programs such as the Environmental Literacy Institute, offered by the Thailand One Health University Network (a SEAOHUN member), and AFROHUN’s Mentored Experiential Learning and Training program, which built on years of experiential education activities at One Health Demonstration Sites. In addition, through collaboration of subject matter experts and curriculum designers across networks, the OHW-NG consortium generated a suite of competency-based asynchronous online courses, case studies and facilitator guides which are hosted on the OHWA website (https://onehealthworkforceacademies.org). To date the OHWA has engaged over 6,000 learners representing 95 countries. Building upon this model, each of the networks established their own online academies to highlight regional topics and offer training in local languages. (SEAOHUN – https://academy.seaohun.org and AFROHUN – https://academy.afrohun.org). While the educational offerings developed as part of OHW-NG were broad with respect to subject matter, audience and delivery mode, they were grounded by a consistent set of pedagogical systems, which together form the theoretical framework for instructional design and teaching practices.

Constructivist and experiential learning theories support OHW-NG’s approach to CBE by emphasizing active, learner-driven engagement in real-world contexts where knowledge is constructed through experience and reflection (Berrian et al., Reference Berrian, Smith, van Rooyen, Martínez-López, Plank, Smith and Conrad2017). These theories support CBE’s focus on mastery by enabling learners to demonstrate competencies through tasks that require critical thinking, problem-solving and application of skills in realistic settings (Kolb, Reference Kolb1984; Shepard, Reference Shepard2000; Togami et al., Reference Togami, Gardy, Hansen, Poste, Rizzo, Wilson and Mazet2018).

OHWA’s application of constructivist principles in CBE

OHWA’s training and empowerment programs exemplify the integration of constructivist principles within a CBE framework. For example, while all OHWA courses are asynchronous, they promote active learning through real-world scenarios, enhancing the relevance and applicability of the educational content. The courses offer self-paced, competency-based progression, which allows learners to navigate the material at their own pace, ensuring mastery of each competency before advancing. Collaborative learning through communities of practice fosters peer-to-peer learning and knowledge sharing, reflecting the constructivist emphasis on social interaction in knowledge construction. Across all OHWA offerings, there is an emphasis on reflective practice, where learners are encouraged to apply new insights and integrate new knowledge to their lived experiences.

Case studies are a core pedagogical strategy used throughout OHWA’s curriculum to immerse learners in real-world scenarios that mirror the complexity and interdisciplinarity of One Health challenges. Their use is deeply grounded in constructivist learning theory, which emphasizes learning through authentic, context-rich experiences.

In a constructivist framework, case studies allow learners to actively tackle problems, apply prior knowledge and develop new understandings through exploration, reflection and dialogue. Rather than passively absorbing facts, learners work through scenarios that demand critical thinking, ethical reasoning and decision-making – skills central to professional success in the One Health field. From a competency-based education (CBE) perspective, case studies provide a structured yet flexible means of demonstrating mastery. They are particularly effective for assessing learners’ ability to apply knowledge across domains – such as epidemiology, environmental science, risk communication and public health policy.

Field-based learning

As part of the OHW-NG Training and Empowerment objective, AFROHUN developed a series of field-based learning activities aligned closely with both Constructivist Learning Theory and Experiential Learning Theory in its approach to preparing One Health practitioners for complex, real-world challenges (https://academy.afrohun.org).

In these activities, multidisciplinary and multiprofessional teams of learners are immersed in field sites that require them to collaborate, analyze community health challenges and co-develop interventions with stakeholders. These activities emphasize engaging communities in planning and implementing field activities at demonstration sites, creating learning that is socially grounded, contextualized and co-constructed through participation.

Experiential Learning Theory, particularly Kolb’s (Reference Kolb1984) model, is evident throughout the process. Learners engage in concrete experiences such as conducting community assessments and interviews, followed by reflective observation through discussion, logbook writing and debriefings. They then engage in abstract conceptualization, as they analyze data and develop intervention strategies and finally active experimentation, applying those strategies within the communities.

By embedding learners in real-world community settings and fostering collaborative, interdisciplinary engagement, OHW-NG’s field-based learning exemplifies a constructivist and experiential learning approach that prepares One Health practitioners not just to know, but to do – bridging theory and practice in authentic, high-stakes environments.

Student engagement

A powerful example of the impact of experiential learning and student engagement has been the activities and efforts of Student One Health Innovation Clubs (SOHICs). Initiated by AFROHUN and later adopted by SEAOHUN (colloquially known One Health Student Clubs), SOHICs are self-organizing platforms with chapters at many AFROHUN and SEAOHUN member institutions and have expanded beyond that as informal clubs by enthusiastic students. In 2024 alone, there were over 5000 SOHIC members from 30 clubs across Africa and more than 1,700 SOHIC members from 55 clubs across Southeast Asia. SOHIC alumni often credit their participation in such club activities as instrumental in influencing their career trajectory and professional aspirations, highlighting the impact of diverse learning opportunities and meaningful community engagement experiences offered through these platforms (Ssekamatte et al., Reference Ssekamatte, Mugambe, Nalugya, Isunju, Kalibala, Musewa, Bikaako, Nattimba, Tigaiza, Nakalembe and Osuret2022).

SOHIC activities frequently center on community engagement, support breaking down disciplinary silos and often help fill gaps in outreach and communication efforts. Examples of activities include community rabies vaccination efforts that bring together many stakeholder groups, Hackathon competitions that challenge students to design innovative solutions to local challenges, environmental cleanup initiatives that promote sustainable practices and zoonotic diseases education events in rural communities.

AFROHUN Kenya’s Hackathon events nicely illustrate experiential education in action. Each featuring a different theme, a recent event empowered over 100 students to brainstorm healthcare waste management solutions. Over several weeks, student teams collaborated in a hackathon-style competition, guided by expert mentors across various fields to rapidly prototype, test and refine innovative solutions. The competition exemplified how youth-led innovation, mentorship and multidisciplinary collaboration can generate scalable solutions for pressing challenges, while fostering partnerships between academia, industry and government to transform prototypes into impactful initiatives.

“I think that exercise for me was what made me really good at my job. Because when I started working, I didn’t have the ramp up period. You know, I didn’t have to start to learn on the job [because] I’d already learned that in school. I got to the job on the day one, and I’m ready to hit the ground running. So, for me, I think AFROHUN and the Hackathon truly, honestly impacted my career.” - AFROHUN Kenya Alumni, now works at the World Health Organization.

Other approaches to SOHIC engagement can be seen across SEAOHUN, where SOHICs are often engaged in field trip style activities that expose students to real world One Health challenges. For example, LAOHUN SOHIC members travelled to the capital city for hands-on learning at three locations, focusing on food safety, communicable disease prevention and waste management. The experience enhanced students’ One Health skills, deepened their understanding of zoonotic disease prevention and inspired their commitment to improving public health and environmental sustainability.

SOHIC activities have also played important roles in community engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic and other regional outbreak responses. For example, with supplemental funding provided by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), AFROHUN Côte d’Ivoire mobilized SOHICs to support the national COVID-19 vaccination strategy and combat misinformation across six university campuses and training hospitals. SOHIC messaging reached nearly 2,500 community members with important COVID-19 vaccination messaging. AFROHUN Uganda, with support from the Mbarara University SOHIC, played a crucial role in responding to an anthrax outbreak in Ibanda District by working alongside local authorities to address the outbreak and engage the community in risk communication and education. Their efforts were pivotal in dispelling myths, reducing stigma and preventing further infections, highlighting the power of community engagement and the One Health approach in managing zoonotic diseases. In collaboration with Boehringer Ingelheim and local stakeholders, the Malaysia SOHIC team led the STOP Rabies Initiative to eradicate human-dog-mediated rabies through vaccination campaigns and risk communication and outreach. The team administered 740 vaccine doses to cats and dogs across three districts in Sarawak fostering collaboration between the public health and veterinary sectors.

The role of One Health champions

The role of One Health champions cannot be underscored enough. While the One Health Approach is increasingly recognized as a useful framework for addressing complex health challenges, dedicated vision, leadership and unflagging enthusiasm for the One Health approach and its benefits has been critical for the success of these networks; students and faculty alike pick up on this enthusiasm. Numerous AFROHUN and SEAOHUN alumni have gone one to become One Health influencers, hold leadership positions and are driving One Health agendas in their organizations and nations. Examples of the individuals that embody the principles of authentic One Health professionals, reflected in their professional activities and community service from a local to global scale include:

-

An AFROHUN Uganda alumni who is a WHO One Health High Level Expert Panel member, while simultaneously pursuing a PhD at University of Cambridge, focused on the mathematical modeling of Rift Valley Fever disease transmission in Uganda.

-

An AFROHUN Tanzania alumni who is a physician, an aspiring epidemiologist, a passionate advocate for reproductive health, a 2024–2025 Mandela Rhodes Foundation Scholar and a 2022 graduate of Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences. She credits her participation with SOHICs and community outreach activities during her time in school in shaping her career as a public health enthusiast.

-

A Malaysian One Health University Network (MYOHUN) alumni who is a Public Health Specialist currently serving as Special Officer to the Minister of Health Malaysia. A 2018 graduate from the DrPH program at Universiti Putra Malaysia, at the Ministry of Health he is committed to ensuring the One Health agenda remains a key pillar of the nation.

-

A Thailand One Health University Network alumni and 2018 Environment Literacy Institute participant as an Environmental Management PhD student who now runs her family’s Agri-nature educational center in Thailand.

Empowerment considerations

From the outset, the OHW-NG prioritized gender and empowerment as a cross-cutting theme across project objectives, which was innovative and strove to provide transformative leadership for the project activities. Through the direction of a dedicated lead on the OHW-NG Global Team, content on gender and empowerment was infused throughout project activities, delivered through direct trainings and workshops and informed university curricula development. Guided by an annual Gender Action Plan, the OH networks integrated gender as a core competency across their programming efforts, which is critical given the centrality of gender to disease impacts and health outcomes. Member universities benefited through access to experts and professional programs, such as the Master of Public Health program at the Kinshasa School of Public Health in DRC, were able to develop policy recommendations for consideration in their degree programming.

Conclusion - future directions for One Health university networks

In an era marked by political changes, looming climatic catastrophes and the ever-present risk of infectious diseases and global pandemics, the stability of well-connected One Health University networks are increasingly appealing. Durable to political turnover and grounded in the scientific method and academic integrity, the social capital of the relationships built within One Health University Networks have tremendous continued potential. What is clear is that for these networks to remain relevant and viable, sustainable, robust and flexible funding is necessary for network survival. To accomplish this, illustrating the value of networks to university leadership and their stakeholders is critical so that funding can shift to domestic and regional sources, rather than relying solely on international funding agencies.

As the networks have matured, their regional relevance and position of influence with national governments has increased. Faculty from member universities are now routinely invited to contribute to national level One Health action plans, human resource mapping and workforce strategy development initiatives, support outbreak preparedness and response efforts, develop and deliver accredited continuous professional development education for ministry personnel and inform national research agendas. These activities often directly support of national JEE targets, particularly related to multisectoral workforce capacity, human resources and risk communication and community engagement during health emergencies.

Aligned with the USAID Localization strategy, both the SEAOHUN and AFROHUN networks have independently and successfully secured external funding for their activities, critical for their long-term future (Zuber et al., Reference Zuber, Yawe, Krurchittham, Naigaga, Nannyanzi, Meeyam, Halabi, Romero-Hernandez, Edison, Castillo, Martins, Saylors, Wolking and Smith2025). Recognizing the importance of locally lead initiatives to meet local priorities, each country chapter/network has also built durable communication pathways with local USAID missions and other donors while simultaneously taking steps to strengthen their own organizational capacities. Proof of this is exemplified by the new One Health SWIFT award, which represents continued funding for SEAOHUN activities originating from USAID’s Regional Development Mission for Asia. Other partnerships with organizations such as Chevron and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) have proven fruitful for the networks to continue One Health training and other global health efforts.

As this chapter of investment sunsets, USAID and the university networks it has supported over the last fifteen years, can confidently claim that they have contributed to improved global health security and the development of strong and resilient public health systems, and their personnel and the future generations of One Health practitioners are ready and capable to respond to current and future global challenges.

Data availability statement

Data used for this project were extracted from literature sources cited in the reference section of this paper, publicly available program reports, or gleaned through conversations and interviews with programmatic staff and alumni.

Acknowledgements

We extend a sincere appreciation to the AFROHUN and SEAOHUN networks for your partnership on the OHW-NG project over the last five years. To Professor William Bazeyo, Dr. Irene Naigaga, Dr. Vipat Kuruchittham and Dr. Tongkorn Meeyam; your leadership, vision, and dedication to training the next generation of One Health professionals and promoting global health security in your countries and regions is admirable. To the thousands of faculty, staff, alumni, and professionals who are part of the extended One Health University Network, thank you for your continued efforts in making this world a healthier place to call home. And to the many partners within the OHW-NG Consortium, and Global Team, thank you for your time, contributions to this project, and unflagging enthusiasm for One Health.

Author contributions

The concept was agreed by all authors; JL, DJW, MK, and CM created a first draft, all authors then contributed to adding to and editing the final submitted version. All authors read and approved this manuscript before submission to this journal.

Financial support

This study was made possible by the generous support of the American people through US Agency for International Development (USAID) One Health Workforce - Next Generation (OHW-NG) Award 7200AA19CA00018; and funding from the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID or the United States Government. The sponsor did not play any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Competing interests

None.

Ethics statement

This project was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of California, Davis (IRB Number 2,246,686–1). Interview participants gave verbal informed consent to take part in the study.

Comments

No accompanying comment.