In the rapidly growing field of world history, global interactions and exchanges of goods and people are a major focus of attention. Much of Europe's exploration of the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds was intended to bypass the Ottoman Empire's near monopoly of East–West trade, not only through the Mediterranean but also over Asian and African land routes. Sitting astride the Bosphorus and Dardanelles and extending for thousands of miles into Europe, Asia, and Africa, the Ottoman Empire formed the nexus of world trade and travel. This fact has been obscured by decades of emphasis on the European voyages to the New World and China, and on the Ottomans as a Mediterranean power.Footnote 1 The Ottomans were also a major player in North–South commerce, the slave trade, piracy, smuggling, and the exchange of raw materials for finished goods. European trade with the Middle East in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries far outstripped that with more distant lands, and these proportions altered only gradually during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The commerce of the Ottoman Empire was an important research topic in the early and middle twentieth century, but it was studied almost exclusively from European sources (e.g., Popescu Reference Popescu1997/98; e.g., Heyd Reference Heyd1885; Masson Reference Masson1896, Reference Masson1911; Epstein Reference Epstein1908; Wood Reference Wood1935; Davis Reference Davis1967). The Ottomans, however, kept detailed records of their own, which have hardly been tapped, particularly for the later centuries of the empire. The study of these records could reveal aspects of trade outside the European purview and yield new insights into Europe's connections with the East. Ottoman customs registers (gümrük defterleri) are full of data on ships, seamen, merchants, goods, and prices. The records were kept at every major port by the men who collected customs dues on goods passing Ottoman frontiers. Because they include the names, origins, and owners of incoming commercial vessels; the origins of merchants; types and quantities of goods traded; amounts of customs dues paid at ports of entry; and the dispensation of revenues, these customs registers could yield an unparalleled look at trade and travel in and through the Ottoman Empire.

Who were the Ottoman merchants and with whom did they associate? How far did merchants from Asia or Europe travel within or across the Ottoman realm? As European trade increased and decreased, what happened to Ottoman trade? What alterations in taste affected commercial flows? How far did Ottoman goods spread around the empire or around the world? By what paths did foreign goods reach Ottoman subjects? What about Ottoman trade with Muslim countries to the east; with Russia, Poland, and Sweden to the north; or with countries to the south? The registers of customs dues (and those on market taxes, not examined here) contain information relevant to such questions. The sheer quantity of data lends itself to overall comparisons as well as detailed investigations. In the hope of stimulating further study, this preliminary article brings together the current scholarship on customs registers through a keyword search on the terms customs dues, customs duties, douane, and gümrük. It includes information on documents in the Prime Minister's Ottoman Archive in Istanbul (Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi; BOA) and provides a list of registers currently available there. It also explains the different types of registers and the information they provide.

Customs registers are available primarily in the Maliyeden Müdevver (MAD), Kamil Kepeci (KK), and Bab-ı Defteri (D) collections of the BOA, with some late registers in the Maliye Nezareti (ML) collection (see Appendix A for a provisional list). Their publication and study were promoted by Halil İnalcık and several Hungarian scholars whose works are noted below. According to Suraiya Faroqhi (Reference Faroqhi2005), however, most customs registers, mainly from the eighteenth century, remained uncataloged, and this had not changed by 2014. Of those cataloged, some registers are not yet digitized, and few are published or discussed. Faroqhi, however, is perhaps too pessimistic about what we can learn from these documents. If the right questions are asked, especially of a series of registers distributed over space or time, these documents can contribute greatly to our picture of Ottoman commerce.

Gümrük and Its Origins

Ottoman commerce was huge; customs dues in the fifteenth century totaled over 10 percent of state mukataa revenues (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1994, 55–56). The empire was divided into several customs zones. Merchants paid customs dues only once in each zone and received a document (tezkire) attesting to the payment (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1995, 91–92). Rates varied according to the type of goods and the identity and religion of the merchant; Muslims paid less than non-Muslims, and Ottoman non-Muslims less than foreigners. Customs were usually charged ad valorem (based on the estimated value of the commodity), but some goods were charged by measure, and later, specific tariffs were established. Exports to Europe paid more than exports to Muslim lands, but imports in demand paid less (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1995, 92, 95–96). Initially in kind, these dues were monetized probably in the sixteenth century.

Customs taxes have a long history prior to the Ottomans. The Turkish word gümrük comes from the Latin commercio and the Greek kommerkion, which suggests a Roman and Byzantine origin. Similar taxes were collected in the pre-Ottoman Islamic empires, also influenced by Roman-Byzantine practices.Footnote 2 As the Ottomans conquered former Byzantine territories and Italian trading posts, they absorbed existing relations with those ports’ Mediterranean trading partners (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1995, Thomas Reference Thomas1880–89, 1:313–18). For example, Aydın and Menteşe had trade relations with Venice in the fourteenth century, and when these places came under Ottoman control in 1390, Bayezid I confirmed the Venetian privileges and customs rates and extended them across the empire.Footnote 3 The first Ottoman capitulation, granted to Genoa by Orhan after the capture of Gelibolu in 753/1352, has been lost, but its renewal by Murad I in 789/1387 is extant.Footnote 4 The capitulations clearly resulted from negotiation, and the Venetians considered them peace or trade treaties, but the Ottomans couched them as unilateral grants of privileges in return for peace and friendship from a putative enemy (aman), an interpretation in accord with Islamic law (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1971, Grignaschi Reference Grignaschi1976, Zarinebaf, Shafir, and Griffith Reference Zarinebaf, Shafir and Griffith2014).

Although no actual customs documents from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries survive, the Venetian archives contain copies of trade agreements and correspondence with Ottoman rulers and other Turkish princes, especially Menteşe and Karaman.Footnote 5 Ragusa (Dubrovnik), which came under Ottoman suzerainty in 1433, preserved the old Byzantine customs rate of 2 percent, making it a major port for Ottoman trade with Italy and a terminus of the cross-Balkan route to Iran and the East (İnalcık 1994, 256–64). After conquering Constantinople, the Ottomans extended commercial privileges to the Genoese at Galata (1453) and later to the merchants of other Italian city-states (Heyd 1885, 2:293, 310, 336–39; İnalcık 1971; Bulunur 2009; von Hammer-Purgstall [Reference von Hammer-Purgstall1827–35] 1965, 675–77). The conquest of the Arab lands brought the Catalans and French into the picture, as they had long-established trade relations with Egypt and Syria. The draft Ottoman–French capitulations of 1536 were not confirmed, but the Polish received capitulations in 1553, the French definitively in 1569, and the English in 1580.

Mehmed II raised customs rates from 2 percent to as much as 5 percent and issued regulations specifying who should pay, where, and on what commodities.Footnote 6 In the sixteenth century, 5 percent was the general rate for foreigners, while Ottoman non-Muslims paid less and Muslims typically paid 2 percent. Over time, customs dues were charged on more goods, and taxes were adjusted according to the markets for different commodities. Since these amounts still varied according to location and type of commodity, ambassadors of foreign nations sought to negotiate fixed tariffs (Wood, 1935, 27). The English capitulations of 1601 established a general customs rate of 3 percent. This was repeated in the capitulations of 1675, which also listed tariffs for specific kinds of cloth and other commodities (summarized in Hurewitz 1956, 25–32). In later centuries fixed tariff schedules proliferated (e.g., KK4354 is a tariff register for the Istanbul customs in 1242/1826–27, and MAD 19522 is a tariff register for the Austrian trade in 1300/1882–83).

It used to be accepted that after a high point in the sixteenth century, there was a decline in Ottoman commerce resulting from Ottoman peripheralization in the emerging capitalist world system, either in the late sixteenth century or in the mid-eighteenth century. Faroqhi (Reference Faroqhi2005, 4) points out, however, that this view emphasizes oceanic commerce and neglects the overland caravan trade, which remained healthy into the early nineteenth century, and that the decline in Ottoman–European trade reflected a decline in European demand for Asian goods rather than a general decline in Ottoman commerce itself or in trade with other parts of the world. The Ottomans remained essential players in global commerce and exchange throughout the early modern period and did not totally lose their significance even during the nineteenth century. As a bureaucratic empire, they kept extensive records, the study of which will shed new light not only on their own trade but also on global flows and interchanges with Western and Eastern Europe and with other regions in Asia and Africa.

Ottoman Customs Records

From the seventeenth century on, customs rates for Europeans and European goods were stated in the capitulations.Footnote 7 The payment of customs left other types of records as well. Detailed registers or daybooks, called müfredât or ruznâmçe, recorded daily arrivals at the port, including names and types of ships, names of shipowners and merchants, and types of goods carried, their qualitative differences, quantities, and amounts paid in customs. Customs stations on land made detailed records of caravans and merchants, including the types of goods carried and their origins. Early registers also included the prices of goods. For descriptions of customs registers, see Kütükoğlu (1980a). For a list of customs registers and documents in the Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (BOA), see Appendix A. These detailed registers are the most interesting and useful of the Ottoman customs documents, but few of them are accessible in the archives, and apparently their production or preservation decreased over time. Other kinds of registers, however, were preserved in larger numbers.

Each port had regulations (kanunnames) for what taxes should be charged, including detailed lists of customs rates and goods liable for payment. Customs dues were usually farmed or outsourced to the highest bidder (Genҫ Reference Genç2000, Salzmann Reference Salzmann1993). The absence of detailed registers for the fourteenth-century Aegean ports may be due to the farming out of customs dues to Italian agents (Fleet Reference Fleet2003). Each tax farmer had a scribe who maintained mukataa documents of various types, including detailed registers or daybooks (müfredât or ruznâmçe), summary reports (muhasebe and icmal), and arrears registers (bakiye or bekâyâ). Although few detailed registers are available, many summarized registers survive in the archives, especially for the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The mukataa registers provide information on revenues collected, tax farmers, collectors and their scribes, brokers, and weighers. Some individual tax farmers’ accounts also survive and, most numerous of all, registers of expenditures of customs revenues on pensions and salaries (usually military). As Faroqhi (Reference Faroqhi2005) notes, however, tax farms often consisted of an amalgam of taxes for a particular area, and it may be difficult to separate out the amounts coming specifically from customs dues. The later re-centralization of tax farming produced summary registers recording customs totals on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis. When the esham (shares) method became prevalent in tax farming, esham registers of customs dues also appeared.

Beginning in the late eighteenth century there were also customs tariff registers specifying set import and export duties for certain commodities (gümrük tarifesi). The earliest tariff register for trade between the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies is transcribed into Ottoman print (Turan 1967). The document, dated 1216/1801, is taken from Ecnebi Defteri No. 96/1 (pp. 132–35), which covers the years 1153–1276/1740–1859. A tariff register of 1763 found in a manuscript of the dragoman Rodolpho Bragiotti has been translated into modern Turkish (Sahillioğlu 1968). A tariff register covering the period 1216–54/1801–38 (Register D.BŞM 42279/26.) contains tariff lists for several European countries that show the names of goods (e.g., broadcloth of London, high quality), the units of measurement, and the old and new tariffs (Matsui Reference Matsui2003). The register includes manufactured goods both Ottoman and foreign, industrial goods such as yarn and metals, raw materials, and foodstuffs. Edicts and regulations (hukums and kanunnames) record laws on trade and its taxation, while entries in ahkâm, kayit/kuyud, and mühimme registers, as well as kadı sicills, describe specific problems related to customs dues and their collection. Tax farmers encountering cheating turned to the state, generating orders and edicts on such problems (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1995, 97). Tensions between taxpaying merchants and tax collectors seeking to maximize revenue led to smuggling, which left few records but generated court cases. The court records of port cities provide information on commercial affairs, tax payment or non-payment, and problems with tax farmers and smugglers. All of these sources can be used to uncover Ottoman mercantile practices and relations.

Scholars have published only a few customs registers and only partial data from others; a great deal remains to be done, particularly with respect to the Ottomans’ non-European trade, since trade with Western Europe has been widely studied using European sources. A search of the archive catalogs yielded no additional detailed registers accessible as of summer 2014, but many summary registers are still unexploited, especially for the later period. These registers provide information on Ottomans and non-Ottomans involved in commercial interactions, goods exchanged, and patterns of trade through both space and time.

Detailed registers published in their entirety include a mukataa register of the Budin customs covering the periods 1550–51, 1571–74, and 1579–80 (catalog number Flügel #1356), published in 1962 in printed Ottoman script with a discussion in German (Fekete and Káldy-Nagy 1962). Another published register is a customs arrears register for the city of Kefe/Caffa in Crimea for the period 1487–1490 (KK5280m). It is detailed but partial, showing only customs dues unpaid at the register's date. This register is published in facsimile and in printed Ottoman script, with a translation and supporting studies in English (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1995, 97). An undated register for Trabzon, Samsun, and associated ports in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century is published in modern Turkish translation (Aygün Reference Aygün2009).Footnote 8 This register gives the names of merchants, the amounts and types of goods, and the sums paid in customs dues in the month of Şubat, with daily totals. Data from other registers, including customs registers of various types, treaties and agreements, regulatory codes, registers of important affairs (mühimme defterleri), and Islamic court registers (kadı sicilleri) appear in the scholarly articles discussed below.

Customs Registers and the Commercial World

The following survey of publications on customs registers focuses on cataloging information and the categories of data in each register type. Space considerations limit the discussion of Ottoman commercial interconnections, which would highlight the great potential of these registers. One of the oldest extant detailed customs registers is KK 5280m, an arrears register for Kefe in Crimea dated 892/1496–97 but covering the period 1487–90 and recording trade across the Black Sea (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1995). This register lists ships anchoring at Kefe with captains’ names and sometimes places of origin, the merchants on each ship, the goods imported with quantities and values, and the amounts of customs unpaid. It also lists the prices of different kinds of cloth and the cities from which or through which they were exported to Kefe. Cotton cloth and thread were brought from Anatolian towns and villages to specific mercantile centers for processing (weaving and dying) and subsequent resale (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1993, 265). Textiles and garments reaching Kefe, Kilia, and Akkirman were in turn exported northward in exchange for furs, Wallachian knives, and raw materials (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1993, 268).

Ships in the Kefe trade were owned by Muslims, Ottoman non-Muslims, and Italians, by sea captains, state officials, and merchants, and the merchants they carried were not limited to their owners’ faith or ethnicity (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1995, 113). Many of the same shippers and merchants also appear in a later register for Kilia and Akkirman (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1995, 135–137). This still unpublished register (MAD 6) is dated 899 in the catalog—and the section covering the Ahyolu salt works is from 899/1493–94—but it also includes the Kilia and Akkirman customs of 911/1505–06, with arrears from 909/1503–04 and 910/1504–05. The information it provides on who arrived when yields clues to shipping routes, which altered to avoid dangers and expenses and to maximize profits (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1995, 114–16). One unused register for the early sixteenth century, a collector's ruznamçe or daily register of 118 pages for the customs of Akkirman, would round out our picture of this region's trade (MAD 15649, dated 915/1509 in the catalog but covering the year 912/1506). The data on cotton exports have been used to trace the effect of Indian and European cotton imports on the Ottoman cotton trade. In the seventeenth century, Indian cotton began to flood the Ottoman market, and the Ottomans re-exported it to others. By the eighteenth century, imported fabrics dominated the luxury market, but cheaper cottons were largely Ottoman-made (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1993, 299). The Kefe registers have also helped interpret entries on merchants in the court records of Bursa, making possible a detailed description of early Ottoman trade through that city (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1960, 132 n1).

A customs register including the town of Tulça reveals changes in the Black Sea trade in the next few decades. Register MAD 30, which records the customs dues of several Danubian ports, is dated 888/1483 in the archive catalog, but the contents come from the years 902–03/1496–98, 912–14/1506–09, and 920–23/1514–17 (İnalcık Reference İnalcık1960, 132 n1). Systematic study of the information on Tulça has shown that by 1517 all merchants trading there were Muslims; after expelling the Genoese from the Black Sea in 1475, the Ottomans took over as intermediaries between the Black Sea ports and the Mediterranean (Hóvári Reference Hóvári1984). This register records the names of merchants, the dates of transaction, the quantities and values of each type of merchandise, and the amount of customs duty paid. It notes the salaries of the tax farmer, agent, and clerk, as well as the remission of receipts to the fortress of Akkirman. The register also records ferry fees for men and animals across the Danube; slaves paid no customs dues, but the ferry fees for slaves reveal a brisk traffic. Textiles were the principal items exported at Tulça. Foodstuffs were next in value, followed by manufactured goods such as metalware, glassware, soap, and raw materials for manufacturing. Although no spices appear in this register, spices were traded through other Danube ports, and these registers make it possible to trace the routes they followed through Eastern Europe.

Customs registers and documents may also survive in the archives of countries that formerly belonged to the Ottoman Empire, such as Egypt, Yemen, or Bosnia, or in the National Library of Bulgaria, which has a large but mostly uncataloged collection of Ottoman documents (Aktaş and Kahraman Reference Aktaş and Kahraman1994). Some customs registers for Hungary, for example, are in the archives of Vienna, preserved from destruction after the Ottoman loss of Budin (Hóvári Reference Hóvári1984; Flügel Reference Flügel1865–67, 2:459–67). Hungarian scholars Lajos Fekete and Gyula Káldy-Nagy published a large account register covering the mukataa of the iskele (docks) of Budin and Peşte for the period 1550–80, which incorporates several detailed registers of customs dues along with other market taxes (Fekete and Káldy-Nagy Reference Fekete and Káldy-Nagy1962). This register begins by reporting the totals of each tax collected, followed by a detailed, day-by-day listing of each ship that arrived, each merchant and his goods, and the taxes paid. On first glance, the ship-owners were mostly Muslim, but the merchants were quite diverse: Muslims, local Christians and the occasional foreigner, Jews, Gypsies, Janissaries, and Ottoman officials, and the occasional foreigner all took part in the trade. It would be interesting to track changes among them over time.

An example from the cattle trade suggests what can be done with this information. Anna Horváth studied the customs dues of the town of Szolnok in the sixteenth century from a register similar to that of Budin (Horváth Reference Horváth1971, 235–40).Footnote 9 After the Ottoman conquest in 1552, the customs dues and river crossing fees at Szolnok became a mukataa. The mukataa accounts for Szolnok in the years 1558–75 show that customs receipts increased from 5,500–7,500 akçes per month to 11,400–12,800, a doubling of trade. The primary items traded were animals (cows and sheep) and salt (Horváth Reference Horváth1969). The registers for 1558 and 1559 list payments for 603 and 1489 oxen, respectively, but the registers for 1573 and 1575 show that only fifteen years later, 28,365 and 15,011 oxen, respectively, were exported via Szolnok—a tremendous growth—along with equal numbers of sheep while the amount of salt exported in the same period increased more than sixfold. Most of the exporters seem to have been Christians, but a Muslim bey who built a bridge for the cattle may have been a partner in the trade. Thus, these registers inform us not only about trade but also about infrastructure, production, and social relations.

Customs registers for port cities provide a view of shipping through those ports. A register for Antalya in 968/1560–61 (MAD 102) lists thirty-three ships arriving in port over eleven months (Kütükoğlu Reference Kütükoğlu1980a). Of those, twenty-three were from Egypt. They imported slaves, rice, camel skins, and linens and exported carpets, fish, nuts, and opium. A register of the tax on slaves records the ebbs and flows of the slave trade. This is Istanbul register D.BŞM.128, dated 1016/1606–07 in the catalog and covering the year 1015/1605–06 (Yağcı 2013; see also Yağcı Reference Yağcı2011, Reference Yağcı, Erkut and Mitchell2007). It includes daily aggregate totals of slaves imported and taxes collected, as well as a detailed list of the arriving ships with their captains and ports of origin.

The customs registers for port cities clearly reveal the global character of Ottoman trade in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Registers for the port of Alexandretta/İskenderiye dated 1624, 1626, 1627, and 1628 were bound together as TK.MA 1306 and preserved in the Topkapı Sarayı archive and are now available in digital form in the BOA (Káldy-Nagy 1965, 300 n8). Káldy-Nagy's study of them reveals that besides merchants from Western Europe, there were some from Baghdad and Bukhara who sold their wares directly to Europeans in Aleppo. An undated customs register (Document No. 4139/53/1, presumably in the Egyptian national archives) studied by El Mouelhy, which may refer to the seventeenth or eighteenth century, shows goods from the Indies arriving at the port of Suez (El Mouelhy Reference El Mouelhy1952, 90–91). The register lists the customs due on each item and the quantity imported. A French memoir in 1790 stated that these customs brought in the equivalent of a million francs (El Mouelhy Reference El Mouelhy1952, 93). Eighteenth-century registers for İskenderiye and Izmir show ships from Europe, Malta, Crete, and Aleppo, as well as Anatolia (Kütükoğlu Reference Kütükoğlu1980a).

Customs registers from Erzurum (detailed, summary, and mukataa) survive in large numbers from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Erzurum was the entry point for trade from the east and northeast, and its registers on the trade to and from Iran and the Caucasus began to be studied in the 1980s (Erim Reference Erim1984, using numerous documents of all types relating to gümrük). Detailed customs mukataa and inspection (nezaret) registers provide copious information on tax farmers and their revenues (Pamuk Reference Pamuk2013). They also show that while the principal commodity on this route was silk from Iran, also imported were fur, leather, Indian cotton, tobacco, and Caucasian slaves (Erim Reference Erim1991). Exports included woolen and cotton textiles and large amounts of silver. The imported silk was carried initially to Aleppo and later to Izmir, where much of it was sold to Europeans. When imports of fine silk declined, Indian printed cottons rose to take their place. Of the merchants coming from Iran in a single year (1744), 70 percent were Armenians and 17 percent were Muslims. A monthly calculation of revenues in 1770 indicated that caravans arrived from Iran mainly in November, December, and February, while the low point came in July; trade going from Anatolia was more evenly distributed. The registers list Erzurum's connections with many eastern Anatolian and Arab cities, but only Istanbul and Bursa in the west, vividly illustrating how premodern international commerce was normally not composed of far-reaching and risky mercantile ventures, as we today imagine, but of many local transactions connected end-to-end.

The Aegean town of Kuşadası became a port in the seventeenth century after the harbors of Ephesus and Ayasoluk silted up. Cahit Telci translated a customs register from this port: Kuşadası gümrük defteri D.MMK 22754, a summary register from 1135/1722 covering four months (Telci Reference Telci1997).Footnote 10 This register does not contain as much detail as earlier registers; often the merchant is not listed, and the quality or value of the goods is never provided. It does, however, list the types of goods, usually their quantities, and their customs dues. Summary customs registers were also used by Ensar Köse, among other sources, to discuss Mediterranean commerce in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Köse Reference Köse2013; see also Köse Reference Köse and Demir2011). Although disappointed in the level of quantitative data in these summarized sources, Köse was able to see from the register which ports traded with which and what goods came over those routes. A similar register (KK 5252), a summary customs register for Kale-i Sultaniye (Çanakkale) for 1236/1820–21 gives the localities, names of ships, types of goods, and customs fees (Bulunur Reference Bulunur and Demir2008). Numerous summary registers like these survive from a variety of port cities large and small; they list the goods and amounts in some detail but omit other information. Put together, however, they would paint a detailed picture of the coasting trade and commercial relations between the coast and the hinterland that might challenge the common picture of stagnation.

Some customs ports were not on the coast. Mübahat Kütükoğlu studied a customs register of 1253/1838–39 for the province and city of Saraybosna, whose trade seems to have been mainly with Austria or places in Bosna. The register included Muslim, Christian, and Jewish merchants (although places of origin were rarely recorded). Kütükoğlu (1980b, using register MAD 19673) charted the communal identities and comparative tax liabilities of importers and exporters. The data in this register show periods when imports were greater, such as September and December, and periods when exports overtopped imports, such as November. Similar information gathered for a series of ports, or series of years, would graphically demonstrate patterns of local trade.

Necmettin Aygün (2009) used data from a customs register to illustrate the economic role of Trabzon in the nineteenth-century Black Sea trade. This register indicates that most merchants trading there were from the area between Giresün and Rize, but they included Greeks and Armenians as well as Muslims. The goods traded were foodstuffs, textiles, metals, and gunpowder (Aygün 2009, 57–74). These registers demonstrate that all of the empire's peoples engaged in its commerce and that the early modern Ottoman Empire did not become, like Europe's colonies, merely a source of raw materials; Ottoman-manufactured goods were eagerly sought after from the fifteenth century straight through to the nineteenth.

Conclusion

From these studies, we can see that the Ottoman customs registers will yield a sensitive record of the Ottoman Empire's interconnections with the world economy in the early modern period, revealing the materials traded and the people involved. For a truly global picture, Ottoman data must be brought into connection with information on trade in the countries linked to the Ottoman routes. In this way it is possible to gain an accurate picture of where these commodities came from and the many hands through which they passed on the way to their final destinations, as well as how these diverse merchants conducted their intercultural business and how goods were reworked and repurposed in different settings. Erim (Reference Erim1991, 136) points out that the merchants must not be seen as lone individuals but as members of networks that included small-scale local traders, businessmen based in distant cities, and traveling merchants who linked them. Network analysis and other modern techniques should help in developing a much finer and more interesting picture of Ottoman world commerce.

The more recent registers are less full and less interesting, and they must be studied in the context of other sources. They do, however, give information about how the Ottomans conducted commerce that is unavailable in European sources. If the analysis of imports and exports by month performed on the Erzurum and Saraybosna registers were done for more of these registers, for example, it would be possible to see in detail the rhythms of trade over the course of a year and how these rhythms changed over the centuries. Charting the places of origin of the goods traded would improve our map of Ottoman production and allow us to identify the real hinterlands of port cities and towns and their changes over time. These registers reveal the participation of the Ottoman Empire in global exchange both before and after the European explorations; its role in the flow of goods to the north and east as well as to the west; interactions between long-distance and local trade; the changing ownership of commercial shipping; the activities of Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and foreign merchants in Ottoman commerce; and the effects of overseas trade on local cultures.

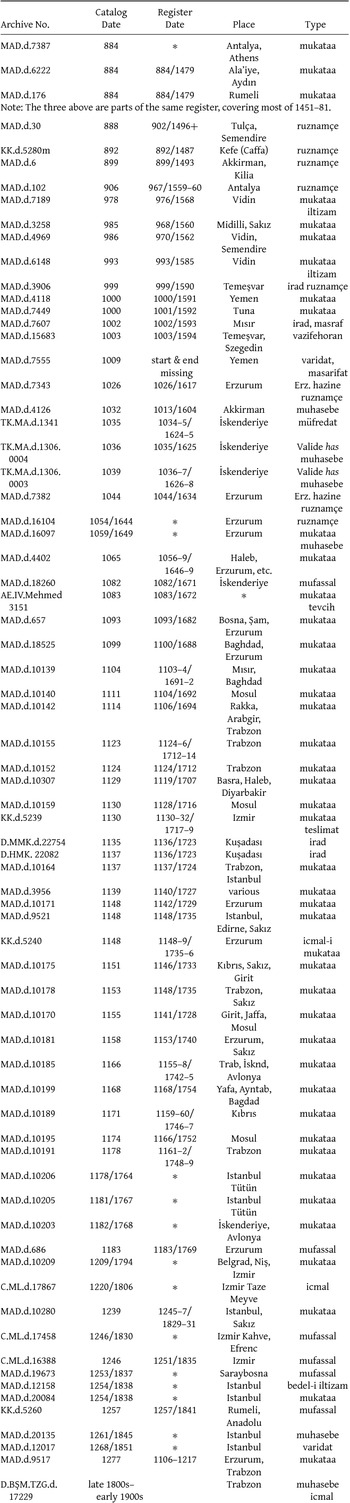

Appendix A: Provisional List of Customs Registers Accessible June 2014

This section lists customs registers, mostly detailed, in the Maliyeden Müdevver catalog of the Prime Minister's Ottoman Archives in Istanbul and some taken from publications. Other types of registers on customs, such as ahkam defterleri, are not included, and some of the summary registers may have been missed. Below this list are other collections containing documents and registers related to customs. The registers appear in order of catalog date, which often differs from the date(s) covered by the register. Some registers include information from several years. All digitized registers were checked. The date listed is usually the first year in the register (sometimes the first and last), and the number after the slash is the first Gregorian year corresponding to that Hijri year. The lists of places covered in these registers are suggestive, not exhaustive. Most of these registers have not been studied.

There are also registers and documents relevant to gümrük or customs dues in other archival collections. Similar documents await discovery in still other collections, but this list includes the major deposits as of June 2014:

-

Maliyeden Müdevver (MAD), 1,630 registers in addition to those listed above

-

Topkapı Sarayı (TS.MA), 758 items related to gümrük, dated 986/1578–1267/1850

-

Ali Emiri (AE), 6,687 documents from Mehmed III's reign to Mahmud II’s, 1574–1839

-

Former Ecnebi Defterleri, now Bab-ı Asafi Düvel-i Ecnebiye Defterleri (A.{DVNSDVE), 118 registers dated 975/1567–1307/1889

-

Evkaf Defterleri, 56 registers dated 1244/1828–1341/1922

-

Cevdet Maliye (C.ML.), 3,018 documents, all from the nineteenth century

-

Cevdet Darbhane (C.DRB.), a few related documents

-

Kamil Kepeci (KK), formerly separate categories for registers issued by different departments, now a single collection, 415 gümrük-related registers dated 892/1487–1270/1853

-

Bab-ı Defteri's numerous sub-collections contain many gümrük-related registers:

-

Avlonya Gümrüğü (D.AVG.), 23 registers dated 934/1528–1206/1792

-

Bursa Mukataası (D.BRM.), 24 registers dated 988/1580–1244/1828

-

Baş Muhasebe (D.BŞM.), 467 registers dated 992/1584–1254/1838

-

Duhan Dönümü (D.MMK.DHN.), 83 registers dated 1107/1695–1251/1835

-

Erzurum Gümrüğü (D.BŞM.ERG.), 67 registers dated 1135/1720–1255/1836

-

Haslar Mukataası (D.HSK.), 12 registers dated 1131/1718–1184/1770

-

Haremeyn Mukataası (D.HMK.), 191 registers dated 1061/1651–1254/1838

-

İstanbul Gümrüğü (D.BŞM.İGE.), 50 registers dated 1157/1744–1255/1838

-

İstanbul Mukataası (D.İSM.), 69 registers dated 974/1566–1255/1839

-

Maden Mukataası (D.MMK.), 248 registers dated 984/1576–1253/1837

-

İstanbul Gümrük Emini (D.MMK.İGE.), 346 registers, dated 1015/1606–1254/1838

-

Mevkufat (D.MFK.), 3 registers dated 1142/1729–1226/1811

-

Trabzon Gümrüğü (D.BŞM.TZG.), 3 registers dated 1036/1627–1209/1795

-

A few miscellaneous registers in other parts of the collection.

-

İbnül-Emin Maliye (¤E.ML.), 719 documents dated 923/1517–1259/1843

-

Hazine-i Hassa (HH.d.), 48 registers dated 1185/1771–1336/1917

-

Maliye (ML.), 309 registers dated 1252/1836–1290/1873 or dateless

-

Masarifat Muhasebesi (ML.MSF.), 162 registers dated 1254/1838–1299/1881

-

Varidat Muhasebesi (ML.VRD.), 115 registers dated 1255/1839 or dateless

-

Bab-ı Ali Evrak Odası İdare Kısmı Belgleri, Dosyas 78 and 79, post-1914

-

Hariciye Nezareti, Mektubi Kalemi (HR.MKT.), 7,130 documents dated 1261/1845–1929