No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 March 2013

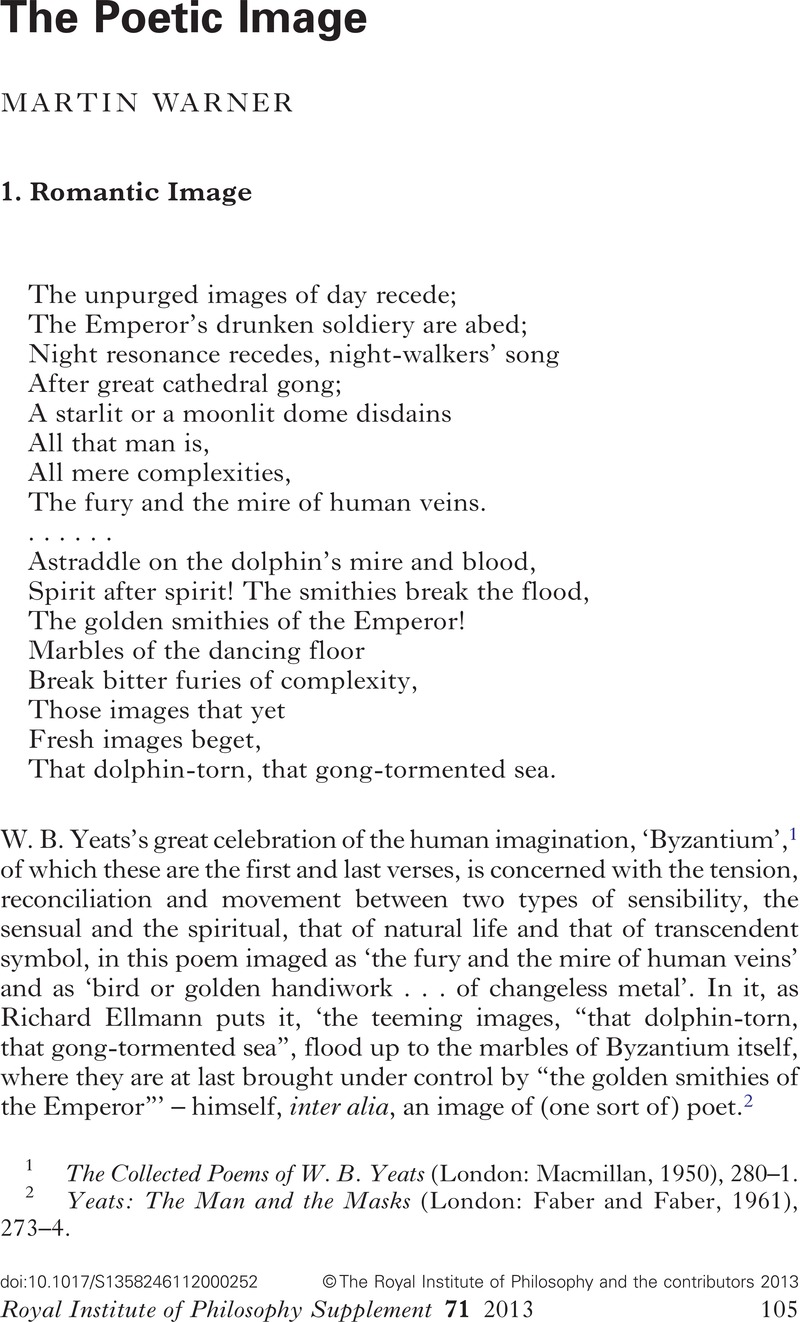

1 The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats (London: Macmillan, 1950), 280–1Google Scholar.

2 Yeats: The Man and the Masks (London: Faber and Faber, 1961), 273–4Google Scholar.

3 F. A. C. Wilson, drawing on Yeats's ‘heterodox mysticism’, takes the Emperor to symbolize God and interprets the passage from natural life to transcendent symbol as that from this life to the next. (W. B. Yeats and Tradition, London: Victor Gollancz, 1958; 231–243Google Scholar, esp. 242; also 15). On my account this ‘mystical’ dimension of the poem images a form of human creativity. ‘Byzantium’ contains both aspects; it is the nature of the Romantic Image to be multifaceted in such ways.

4 Romantic Image (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986), 92Google ScholarPubMed.

5 A Course of Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature, trans. Black, John and Morrison, A. J. W. (New York: AMS Press, 1965), Lect. VI, 88Google Scholar.

6 Romantic Image, op. cit., 5.

7 ‘Baudelaire’, in his Selected Essays (London: Faber and Faber, 1961), 426Google ScholarPubMed.

8 Oeuvres complètes, 2 vols., ed. Marchal, Bertrand (Paris, 1998–2003)Google Scholar, II. 700. A ‘principle’ summarized by Symons, Arthur as ‘to name is to destroy, to suggest is to create’. (The Symbolist Movement in Literature, London: William Heinemann, 1899, 132)Google Scholar

9 The Symbolist Movement in Literature, op.cit, 129.

10 Lustra of Ezra Pound with Earlier Poems (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1917), 50Google Scholar.

11 The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams, Volume I 1909–1939, ed. Litz, A. Walton and MacGowan, Christopher (Manchester: Carcanet, 1987), 224Google Scholar. For convenience, I on occasion refer to this poem using its conventional designation, as above, but strictly it is untitled.

12 See especially ‘Logic and Conversation’ in his Studies in the Way of Words (Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 1989) 22–40Google Scholar.

13 Kermode's word, Romantic Image, op. cit., 85.

14 Anabasis: A Poem (London: Faber and Faber, 1959), 10–11Google Scholar.

15 Romantic Image, 152.

16 ‘The Author's Apology for Heroic Poetry and Poetic Licence’, in Essays of John Dryden, 2 vols. (ed.) Ker, W. P. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1900)Google Scholar, I. 186.

17 On the Sublime xv. §§ 1–2.

18 Lewis, C. Day, The Poetic Image (London: Jonathan Cape, 1947), 18–19Google Scholar.

19 ‘Imagination and Perception’, in his Freedom and Resentment and Other Essays (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), 50Google Scholar.

20 Imagination (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1961), 70Google ScholarPubMed.

21 Living Forms of the Imagination (London & New York: T&T Clark, 2008), 46Google ScholarPubMed.

22 The Concept of Mind (London: Hutchinson, 1949), 247–8Google ScholarPubMed.

23 Imagination', in Williams, Bernard and Montefiore, Alan (eds) British Analytical Philosophy (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966), 160Google Scholar.

24 Ibid., 177, 172.

25 Philosophical Investigations. trans. Anscombe, G.E.M. (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1958)Google Scholar, II, §xi, 200e, 207e, 213e.

26 Warnock, Mary, Imagination (London: Faber and Faber, 1976), chap.IVGoogle Scholar; Scruton, Roger, Art and Imagination: A Study in the Philosophy of Mind (London: Methuen, 1974), chaps. 7 & 8Google Scholar.

27 Imagination, op. cit., 192, 194.

28 ‘Imagination and Perception’, op. cit., 69.

29 Art and Imagination, op. cit., 91, 97–8, 117.

30 Ibid., 94, 100–101, 103, 104.

31 Ibid., 105–6.

32 Ibid., 105.

33 The Poetic Image, op. cit., 23; the quotation is from John Middleton Murry's essay ‘Metaphor’ in his Countries of the Mind: Essays in Literary Criticism (London: Oxford University Press, 1937), II. 4Google Scholar.

34 Ibid, 25. Compare O'Hear, Anthony, The Element of Fire: Science, Art and the Human World (London and New York: Routledge, 1988), 104–5Google Scholar: ‘A literal description of a feeling or attitude I have will not precisely delineate it, nor will it bring out the way in which it is not an object for me, but something I feel, something constitutive of what I am. It is at this point that one can have recourse to metaphor or symbol, transferring certain terms from the public realm to indicate the nature of one's inner state. . . . [T]he metaphor, precisely because it is not literal, awakens intimations and a free flow of associations, where the literal closes and confines one's thought. . . . [T]he criterion of success will be to produce a metaphor which evokes the right sort of experience in one's audience.’

35 The Poetic Image, op. cit., 25, 35. If, as some suppose, Nashe's “air” is an error for “hair” this does not weaken the point; the received line has stood the test of time in a manner the proposed alternative could hardly have done.

36 Ways of Worldmaking (Hassocks, Sussex: Harvester, 1978), 58Google Scholar.

37 Knowledge, Fiction & Imagination (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987), 198–203, 192Google ScholarPubMed.

38 A Course of Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature, op. cit., 88.

39 The Statesman's Manual: or The Bible the Best Guide to Political Skill and Foresight, in his Lay Sermons. Ed. White, R. J., Collected Works, Vol.6, Bollingen Series LXXV (Cambridge and Princeton: Routledge & Kegan Paul and Princeton UP, 1972), 30Google Scholar. Compare: ‘The allegorist leaves the given . . . to talk of that which is confessedly less real, which is a fiction. The symbolist leaves the given to find that which is more real.’ Lewis, C. S., The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1958), 45Google Scholar.

40 ‘On Beauty as the Symbol of Morality’, in his Critique of Judgment, trans. Pluhar, Werner S. (Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett, 1987)Google Scholar, §59, ¶¶ 351–2, 226–7.

41 The Figure of Beatrice: A Study in Dante (London: Faber and Faber, 1943), 7Google Scholar. Williams's use of “image” appears to have significant affinities with that later proposed by Novitz.

42 The Lives of the Poets, 3 vols. (ed.) Middendorf, John H. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010)Google Scholar, I, 26.

43 C. Day Lewis, The Poetic Image, op. cit., 57.

44 Eliot, T. S., Collected Poems: 1909–1962 (London: Faber and Faber, 1974), 13–17Google Scholar.

45 C. Day Lewis, The Poetic Image, op. cit. 93.

46 T. S. Eliot, Collected Poems: 1909–1962, op. cit., 189–95.

47 ‘Imagery and Movement: Notes in the Analysis of Poetry (ii)’, in his A Selection From Scrutiny, Vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), 231Google Scholar. He adds that in considering certain types of poetic effect ‘we find “imagery” giving place to “movement” as the appropriate term for calling attention to what has to be analysed’. (237)

48 From Tennyson's ‘Break, break, break’; compare Eliot's ‘The dancers are all gone under the hill' (‘East Coker’ II).

49 T. S. Eliot, Collected Poems: 1909–1962, op. cit., 210.

50 The Poetic Image, op. cit., 65.

51 A Course of Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature, op. cit., Lect. VI, 87–8.

52 Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, trans. Pears, D. F. and McGuinness, B. F. (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1961)Google Scholar, §3.032.

53 Poetic Argument: Studies in Modern Poetry (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988), 42Google Scholar.

54 Ibid., 51.

55 See, for example, Raine, Kathleen, ‘On the Symbol’, in her Defending Ancient Springs (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), 105–22Google Scholar, and ‘The Vertical Dimension’, Temenos 13, 1992, 195–212Google Scholar. Also Bodkin, Maud, Archetypal Patterns in Poetry: Psychological Studies of Imagination (London: Oxford University Press, 1934)Google Scholar. Symons advocated ‘that confidence in the eternal correspondences between the visible and the invisible universe, which Mallarmé taught’ (The Symbolist Movement in Literature, op.cit, 138).

56 C. Day Lewis's list, The Poetic Image, op. cit., 141.

57 ‘The Rhetoric of Temporality’, in his Blindness and Insight: Essays in the Rhetoric of Contemporary Criticism, 2nd edn, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983)Google Scholar, §I. ‘Allegory and Symbol’, 208.

58 A vigorous response to de Man's essay has been mounted by Douglas Hedley (Living Forms of the Imagination, op. cit., 136–40). For de Man ‘the prevalence of allegory always corresponds to the unveiling of an authentically temporal destiny’, where ‘self’ and ‘non-self’ can never ‘coincide’ (‘The Rhetoric of Temporality’, 206–7), and he downplays the contrast between allegory and symbol as being of ‘secondary importance’, arguing that Coleridge implicitly allows figural language as such to be understood in terms of ‘translucence’ (192–3). Hedley replies, with some plausibility, that this in effect collapses a crucial distinction, pointing out that for Coleridge there is an ‘ontological link between symbols and the reality symbolized [which] becomes transparent in the image’, but that with allegory there is ‘a different relationship between the means of expression and the objects of that expression’ (Living Forms, 138–9). De Man's rejection of any such ontological link, and hence resistance to claims for a symbolic, synecdochal, ‘translucence’ of the eternal through and in the temporal, appears to be in part a consequence of his accepting the self's ‘authentically temporal destiny’ as being crucial to the ‘truths’ supposed to have ‘come to light in the last quarter of the eighteenth century’, and coming close to implying that the associated ‘secularized thought . . . no longer allows a transcendence of the antinomies between the created world and the act of creation’ (‘The Rhetoric of Temporality’, 206–7). Such a position is, of course, incompatible with Coleridgean panentheism. De Man's assault on ‘this symbolical style’ as lacking ‘an entirely good poetic conscience’ (208) looks suspiciously like a form of petitio in the guise of analysis.

59 St.-John Perse, Anabasis, trans. and ed. T. S. Eliot, op.cit., 10–11. These coordinates suggest an affinity with Ezra Pound's ‘ideogrammic method’, with concepts built up from combining concrete images; see his ABC of Reading (London: Routledge, 1934)Google ScholarPubMed.

60 In Defense of Reason (Chicago, Swallow Press,1947), 62–63Google ScholarPubMed.

61 Romantic Image, op. cit., 152, 85.

62 In Anabasis, op. cit., 94.

63 Ibid., 9–10.

64 Ibid., 10.

65 ‘The Music of Poetry’, in his On Poetry and Poets (London: Faber and Faber, 1957), 26Google ScholarPubMed.

66 On the Sublime xv. §2.

67 In terms of genre, Anabase is plainly epic.

68 The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats, op. cit., 245.

69 My thanks to my brother, the poet Francis Warner, for comments and reminders.