Introduction

Scandinavia today represents much-celebrated models of sustainable democratic governance characterized by a peculiar political culture of compromise (Hilson Reference Hilson2008; Knutsen Reference Knutsen2017). This culture took shape over the long nineteenth century (Hilson Reference Hilson2008: Ch. 1). Although the pace and timing of democratization differed across Scandinavia and employer–employee conflicts were pronounced, particularly in Sweden (Berman Reference Berman2006), a pattern of tolerance of political opponents and successful labor market reforms made sure that democracy progressed relatively peacefully and with comparatively few setbacks (Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017: 15; Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli, and Nyzell Reference Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018; Andersen Reference Andersen2021). Most importantly, a compromise was embodied in relatively well-organized and moderate associations that first developed among farmers and later industrial workers (henceforth “workers”) (e.g., Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991: Ch. 8; Ertman Reference Ertman1998: 498–99).

However, little is known about why Scandinavia’s political societies developed this propensity to compromise when compared to other countries (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2012: 14; Møller, Skaaning, and Cornell Reference Møller, Skaaning and Cornell2020: 118–20). Those international studies that include Scandinavia place Denmark and Sweden on separate paths or more general paths comprising several other countries (e.g., Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991; Rueschemeyer et al. Reference Rueschemeyer, Stephens and Stephens1992; Ertman Reference Ertman1998; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019). Scandinavian-based literature tends to downplay comparisons within and beyond Scandinavia, typically focusing on one country (e.g., Trägårdh Reference Trägårdh2007; Karpantschof Reference Karpantschof, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018; Myhre Reference Myhre2018; Bengtsson Reference Bengtsson2019). Substantively, the few explanations of compromise in Scandinavia based on comparative analyses tend to emphasize class coalitions (e.g., Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991) or the qualities and strategies of specific social groups, most often farmers (e.g., Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009; Stråth Reference Stråth, Árnason and Wittrock2012) or workers (e.g., Rueschemeyer et al. Reference Rueschemeyer, Stephens and Stephens1992; Sejersted Reference Sejersted2011; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019), but they overlook why different social groups could organize and behave the way they did. A few intra-Scandinavian comparisons suggest a state-peasant sense of community rooted in a particular version of Protestant Enlightenment as an explanation for the stability of democratization in the nineteenth century (e.g., Sørensen and Stråth Reference Sørensen, Stråth, Sørensen and Stråth1997; see also Alapuro Reference Alapuro, Alapuro and Stenius2010: 18), but this does not explain why peasants could forcefully demand any democratization in the first place.

In explaining Scandinavia’s political societies of compromise, I take stock of two recent contributions. One shows that at least Denmark’s democratic stability can be attributed to the development of vibrant civil societies and institutionalized parties in the long nineteenth century (Møller, Skaaning, and Cornell Reference Møller, Skaaning and Cornell2020: 118–28). Another one shows that the region’s deeper foundations of democracy were forged through contingencies of warfare in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which created a central-level meritocratic state in control of local administration with high levels of impartiality that in turn drove peaceful agrarian reforms in the eighteenth century and arguably created auspicious state-society relations in the nineteenth century (Andersen Reference Andersen2023).

My argument builds on but also challenges these two accounts. Explaining democratic stability, as Møller, Skaaning, and Cornell (Reference Møller, Skaaning and Cornell2020) do, by the strength of political societies approaches an endogenous or trivial claim: Because strong political societies are at least a close-to logical requirement of a functioning democracy, such an explanation invites further analysis of what caused strong political societies in the first place. Conversely, tracing the origins of Scandinavia’s nineteenth-century political societies back to pre-1789 state-administrative legacies and peaceful agrarian reforms, as Andersen (Reference Andersen2023) does, is problematic for two reasons. One is that Scandinavia comprised substantial political-institutional differences well into the nineteenth century between Denmark (an absolutist monarchy until 1849), Norway (a young nation with a liberal-democratic constitution from 1814), and Sweden (an oligarchic regime until 1866), which should have created widely different trajectories of their political societies. Another is that the radicalizing potential of Scandinavia’s late industrialization in the latter half of the nineteenth century (Elvander Reference Elvander2002; Berman Reference Berman2006) should have brought the region onto more authoritarian, revolutionary courses. In answering these puzzles, Andersen (Reference Andersen2023: 2–3, 12–13) merely hypothesizes but does not systematically investigate whether nineteenth-century Scandinavia was, in fact, characterized by “auspicious state-society relations” or whether and how these relations were affected by pre-1789 state-administrative legacies and in turn affected political society developments.

I argue that more meritocratic state administrations tend to act more impartially, treating equal cases alike in policymaking and implementation. Such impartial state administrations did not necessarily imply support for liberal democracy in the long nineteenth century. Yet by their propensity to serve public rather than private interests, impartial civil servants tended to support also the under-privileged, which unintendedly empowered oppositional political societies while also moderating their resistance to the state and facilitating class compromise.

To examine these propositions, I exploit underappreciated native-Scandinavian historiographies and use a comparative-historical approach, contrasting the three Scandinavian countries with Prussia as the most suitable negative case, which shared with Scandinavia several important preconditions, but ended up with a troubled and revolutionary political society.Footnote 1 I find supportive evidence that over the long nineteenth century, Scandinavia’s farmer and worker political societies developed to become relatively moderate and well-organized. This was most crucially shaped by state actions, based on a pre-1789 foundation of impartial administration. Out of a spirit of public service, civil servants tended to support those peasants who had become freeholders due to the eighteeneth-century agrarian reforms. In turn, these farmers carved out autonomy and resources, which, in a context of massive socioeconomic and sociocultural changes, enabled them to form strong civic associations and, later, oppositional political parties. Although initially more repressive, the supportive state approach basically recurred with industrialization and the emergence of a working class. Thus, both farmers’ and workers’ movements thrived and saw the benefits of working together as well as with rather than against public authorities.

The importance of impartial administration in Scandinavia becomes clear when comparing with Prussia, where a patrimonial local administration of landlords, established before 1789 despite central-level meritocracy, impeded significant agrarian reform and political organization and was therefore a major reason why liberal opposition movements of farmers never took off. Because of the continued political-administrative powers of landlords after 1848, central-level bureaucrats could ally with landlords in staunchly repressing workers’ associations and parties, including their political and socioeconomic demands. Thus, the peasantry was eventually mobilized by proto-fascist, militant forces, while significant parts of the otherwise strongly organized workers’ movements turned to violent, revolutionary Marxism.

Impartial administration does not offer a complete explanation for the differing outcomes, as other factors intervened and contributed, but my analysis shows it to be the most convincing one. Socioeconomic, political-institutional, and ethnocultural factors fall short in accounting for the similarities between the Scandinavian countries and their differences vis-à-vis Prussia. Most notably, the first civic associations and political liberalizations emerged after the mid-eighteenth century when the countries’ state-institutional characteristics had already settled. Next, while different modes of nation-building – ethnocultural integration in Scandinavia and militarization and assimilation in Prussia – augmented divergencies in political society formation, these modes only emerged in the latter half of the nineteenth century after the basic pathways toward compromise in Scandinavia and conflict in Prussia were established.

These findings support the importance of state impartiality for building stable democracy in Scandinavia, thereby vindicating findings of Andersen (Reference Andersen2023), among others. However, in contrast to Andersen (Reference Andersen2023), I provide two contributions. First, eighteenth-century agrarian reforms were not a bearing factor since state impartiality drove these reforms as well as the nineteenth-century auspicious state-society relations. Second, I show, rather than simply hypothesize, how state impartiality produced auspicious state-society relations. This suggests that impartial administration yields unmediated influence in avoiding the pitfalls of populism and polarization and constructing democratic governance during times of social and economic upheavals.

Historical setting

My analysis begins in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries but primarily spans the long nineteenth century in Western Europe from the French Revolution in 1789 to around 1913, the year before World War I broke out. For several reasons, this setting is particularly suitable for illuminating the causes of Scandinavia’s political societies of compromise.

The long nineteenth century saw the emergence and settlement of different trajectories of civil society and party formation with lasting consequences, notably for political regime developments. On the eve of the interwar period, both the degree of party system institutionalization and civil society density varied considerably across Western Europe, with many countries only having high levels on one of the two, and this variation greatly shaped democratic stability in the 1920s and 1930s. Those countries that scored high on both before World War I experienced democratic survival; those that lacked one or both experienced democratic breakdown (Ertman Reference Ertman1998).

Moreover, the French Revolution offers a clear critical juncture that serves to handle important alternative explanations. Andersen (Reference Andersen2023) documented that meritocratic and impartial state administration, originating in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century warfare, was the earliest and most convincing explanation for peaceful agrarian reform and stable democratization in Scandinavia. Based on Andersen’s work, I can therefore anchor my analysis in Scandinavia’s and Prussia’s state-institutional differences in 1789 and then investigate their relationship with political society formation after 1789.

This also contributes to handling potential endogeneity. As is well established, the French Revolution marked the onset of the modern political era and mass democracy. Over the next approximately 130 years, popular pressures for liberalization and democratization became the center of politics. Furthermore, although in Prussia and Scandinavia clubs and societies did exist before 1789, they only acquired a mass-level, national character from the early nineteenth century (Blackbourn Reference Blackbourn, Blackbourn and Eley1984a; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009). In this way, because no modern form of political society or democracy existed before 1789, these factors do not challenge any pre-1789 legacies of impartial administration as explanation.

Case comparisons

With this historical setting, the study takes its outset in puzzling similarities between the Scandinavian countries in terms of how civil societies and parties developed and equally puzzling differences when compared to contemporary Prussia. Across Scandinavia, farmers were first movers in building organizationally sophisticated, densely populated, and autonomous associations and parties that were generally moderate in the sense of advancing reforms through negotiation (e.g., Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009). The timing differed. Swedish farmers developed parties earlier, but their liberal mass-based movements played a less prominent role. As second-movers, workers’ associations and parties developed in similarly well-organized and emollient ways from industrialization and settling in the first decade of the twentieth century (e.g., Bryld Reference Bryld1992; Sejersted Reference Sejersted2011) Prussia, which lacked Scandinavia’s civil society and party traits. Prussian farmers only began developing significant, nation-wide movements in the final decades before World War I, by then conducive to right-wing paramilitary extremism (e.g., Blackbourn Reference Blackbourn, Blackbourn and Eley1984a), whereas the workers built a strong associational landscape similar to their Scandinavian counterparts but both associations and parties remained significantly challenged by dogmatic and violent Marxism (e.g., Berman Reference Berman2006).Footnote 2 Prussia’s political society traits additionally coincide with revolutionary outcomes. In contrast to Scandinavia, democracy only came with violent revolution – i.e., in 1918 (Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017: 15).

I employ two types of comparison. The Scandinavian countries were “most similar” in many respects but also surprisingly different on some of the potential explanatory conditions of civil society and party formation (see Przeworski and Teune Reference Przeworski and Teune1970; but see the critique by Mayrl Reference Mayrl, Wilson and Mayrl2024 and the defense by Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013). By comparing across such divergent conditions, I can reject them as explanations for the similar outcome in Scandinavia. Yet, one thing is to explain Scandinavia’s convergence; I also need to explain the region’s divergence from other cases where political societies took a different path from a similar point of departure. I therefore compare the Scandinavian countries with Prussia, rendering probable causation by controlling for similar conditions. Prussia thus shared with Scandinavia a homogenous Protestant population, a church subordinated to the state (Gorski Reference Gorski2003; Stenius Reference Stenius, Alapuro and Stenius2010), and late industrialization from the 1870s (Gerschenkrohn Reference Gerschenkrohn1989; Elvander Reference Elvander2002). On these parameters, Prussia is the only suitable negative case to compare with.Footnote 3 The logic of comparison is insufficient for establishing causality. Thus, for all four cases, I enlist within-case evidence of the effect of the decisive conditions.

While there are quantitative, panel data indicators on state-administrative characteristics back to 1789, they do not extend further back. Nor do I have separate quantitative indicators for farmers’ and workers’ associations and parties or their interaction with the state administration. Instead, the analysis relies on dense but underappreciated native-Scandinavian historiographies of civil society and party developments.Footnote 4 I do not contribute with new insights on the Prussian case but use the well-covered historiographies of modern political development and civil society and party formation in Prussia and the German Empire to gain insights on Scandinavia.

Alternative explanations

Among alternative explanations of civil society and party formation that are prominent in cross-country literatures, I consider the status of rural inequality, political institutions (legacies of constitutionalism and channels for popular participation), and religious-institutional setting (state-church relations and dominant religion) by 1789. Rural inequality before 1789 could have undermined the creation of an independent class of farmers to build political societies and radicalized the rural poor or tenants aspiring for emancipation (e.g., Tuma Reference Tuma1965: 200; Moore Reference Moore1966). Pre-modern legacies of constitutionalism and regularized popular participation via petitions, assembly, or court representation (Sørensen and Stråth Reference Sørensen, Stråth, Sørensen and Stråth1997) could have made the transition to liberal democracy easier, including the integration of mass movements. A predominantly Protestant population could have strengthened civil society and party formation because of the secularism and individualism that emerged from Protestantism. Likewise, church subordination to the state could have removed obstacles for Protestant movements to grow, gain influence, and de-radicalize (Sørensen and Stråth Reference Sørensen, Stråth, Sørensen and Stråth1997). Neither of these factors accounts for the different outcomes of political society between the four cases.

Due to high levels of rural inequality, Denmark’s political societies should have suffered the same fate as Prussia’s. Based on significantly higher levels of constitutionalism and access to political participation for peasants, Sweden should have been able to develop much stronger political societies than the rest of Scandinavia, and, given that levels of constitutionalism and peasant participation were relatively lowest in Denmark and Norway, their political societies should have been even weaker than Prussia’s. Finally, although the Protestant majority was smaller in Prussia, and the Swedish church was more autonomous from the state than in Denmark and Norway (Claesson Reference Claesson2004), all four countries had predominantly Protestant populations with Protestant churches fundamentally subordinate to the state by 1789, Prussia’s political societies should have taken the same fruitful path as Scandinavia’s over the long nineteenth century (Andersen Reference Andersen2023: 6–7).

Prussia’s military campaigns to unite Germany in the 1860s, which successfully concluded in 1871, introduced significant religious divides between Protestants and Catholics into society and politics, weakening the formation of farmer and workers organizations and radicalizing segments of these heterogenous groups (Blackbourn Reference Blackbourn, Blackbourn and Eley1984a: 195–96). However, as I will show later, the important building blocks of weak and extremist political societies were laid in Prussia already in the early nineteenth century, much before German unification and the resulting religious heterogeneity. Most importantly, the Protestant church, rather than working as an independent force, was coopted by the landed elite and state patronage, which hindered agrarian reform from the 1810s and made sure that the church’s hold on the peasantry was used to prevent it from organizing in the 1830s and 1840s (Gould Reference Gould1999: 71–72). A major reason for peasants’ ability to form organizations was their socioeconomic autonomy from landlords (Gundelach Reference Gundelach1988: 102–4; Dyrvik and Feldbæk Reference Dyrvik and Feldbæk1996a: 72–73; Amnå Reference Amnå and Trägårdh2007: 168) for which Protestantism and church subordination do not provide credible explanations.

Although rarely intended as such, except by important nation-builders like Grundtvig in Denmark, key initiatives like folk high schools contributed to what in hindsight could be observed as civic integration. Favored by ethnic homogeneity, this nevertheless only took shape from the latter half of the nineteenth century, particularly in Sweden and Denmark (Glenthøj and Ottosen Reference Glenthøj and Ottosen2021). Comparing with Denmark’s nation-building path is most instructive. In 1789, both Denmark and Prussia had weak national identities. If anything, Denmark, with her possessions in Norway and the German-oriented duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, inhabited more ethnic groups than Prussia with, potentially, different national aspirations, while this conglomerate state also gave the elite a strong sense of belonging among the imperial great powers (Stråth Reference Stråth, Árnason and Wittrock2012: 25). The loss of Norway in 1814 diminished Denmark to a small, more homogenous country, but the monarchy and much of the bourgeoisie remained focused on great power preservation. Until Denmark’s defeat to Prussia in the Second Schleswig War of 1864, there was a firm ambition to keep the German possessions right, and only afterward did popular culture turn inwards to build a nation through more civic and peaceful virtues (Glenthøj and Ottosen Reference Glenthøj and Ottosen2021). Thus, the famous Denmark’s national landscape was prone to moderate political society building only formed in 1864. As I will show, this was much after the state administration had become impartial and farmers had consolidated their first movements.Footnote 5

Key questions thus remain. Why did the Scandinavian countries converge in building well-organized and moderate political societies given their different socioeconomic and political-institutional points of departure – i.e., in 1789? Why did the Scandinavian countries diverge from Prussia given their similar political–religious points of departure? The next sections present a theoretical framework that explains these developments.

The role of impartial administration

Rather than factors pertaining to society or political institutions, my explanation focuses on the state. I argue that a pre-1789 legacy of impartial state administration was the vital precondition for strong and moderate political societies in long nineteenth-century Scandinavia. Skocpol (Reference Skocpol, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985: 22) once noted that autonomous state actions “influence the behavior of all groups and classes.” Historically, such state action comes in two versions: infrastructural power, understood as the enforcement of state rules by penetrating civil society, and despotic power, which is the arbitrary state coercion of civil society. Where the former supersedes the latter, political societies are more easily accommodated and more likely to prosper, which means that democratic governance is more likely. However, if combined with despotic power, infrastructural power can also be associated with the refinement of coercion and dictatorship, such as in Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union (Mann Reference Mann1993: 59–60).

My point is that infrastructural power is more likely to build if the state administration is characterized by an impartial bureaucracy. Impartiality means that civil servants try to serve what they perceive as the public good by valuing equal treatment, inclusive interest representation, and expertise. Values of impartiality do not equal liberal-democratic or emancipatory values – indeed, as Andersen (Reference Andersen2023: 8–10) demonstrated, impartial administration developed under absolute monarchy in Scandinavia. Rather, they are associated with state-administrative norms and the rule of law (Rothstein and Teorell Reference Rothstein and Teorell2008), which should integrate diverse social groups, such as farmers and workers, in mainstream politics. I propose that while impartial administration, given its focus on the public good, removed fundamental obstacles for peasants to organize through agrarian reform that granted civil rights and economic autonomy, it was also vital in integrating both farmers and workers in modern economy and society by perceiving them as important socioeconomic actors to be supported rather than repressed. In turn, farmers and workers would feel better represented, more favored, and increasingly trust that state authorities and the existing political system could improve their situation (Linde and Dahlberg Reference Linde, Dahlberg, Bågenholm, Bauhr, Grimes and Rothstein2021).

Specifically, I expect two mechanisms to manifest empirically. In the first “top-down” mechanism, impartial administration supports farmer and worker political societies by accepting their presence, facilitating their prosperity, rights, and influence, and/or offering public–private partnerships by including broad interests and experts in policymaking and implementation. The second “bottom-up” mechanism is two-sided as farmer and worker political societies, first, thrive on state support and, second, express satisfaction with state initiatives and/or engage in state cooperation. By contrast, a biased central and/or local administration where socioeconomic or political criteria staffed officialdom closed off farmers and workers from influence and rights, excessively targeted repression against them, and limited their public roles to a minimum and under strict state control. This, in turn, undermined and radicalized farmer and worker political societies. For the top-down mechanism, indicators include civil servant advice and implementation of freedom of religion, speech, assembly, and association, incorporation in local and national politics, and financial/business assistance. For the bottom-up mechanism, they include number and breadth of associations and parties, their membership and size of public gatherings, their attitudes to and cooperation with public authorities and other social groups and parties in municipalities, parliaments, and state commissions.

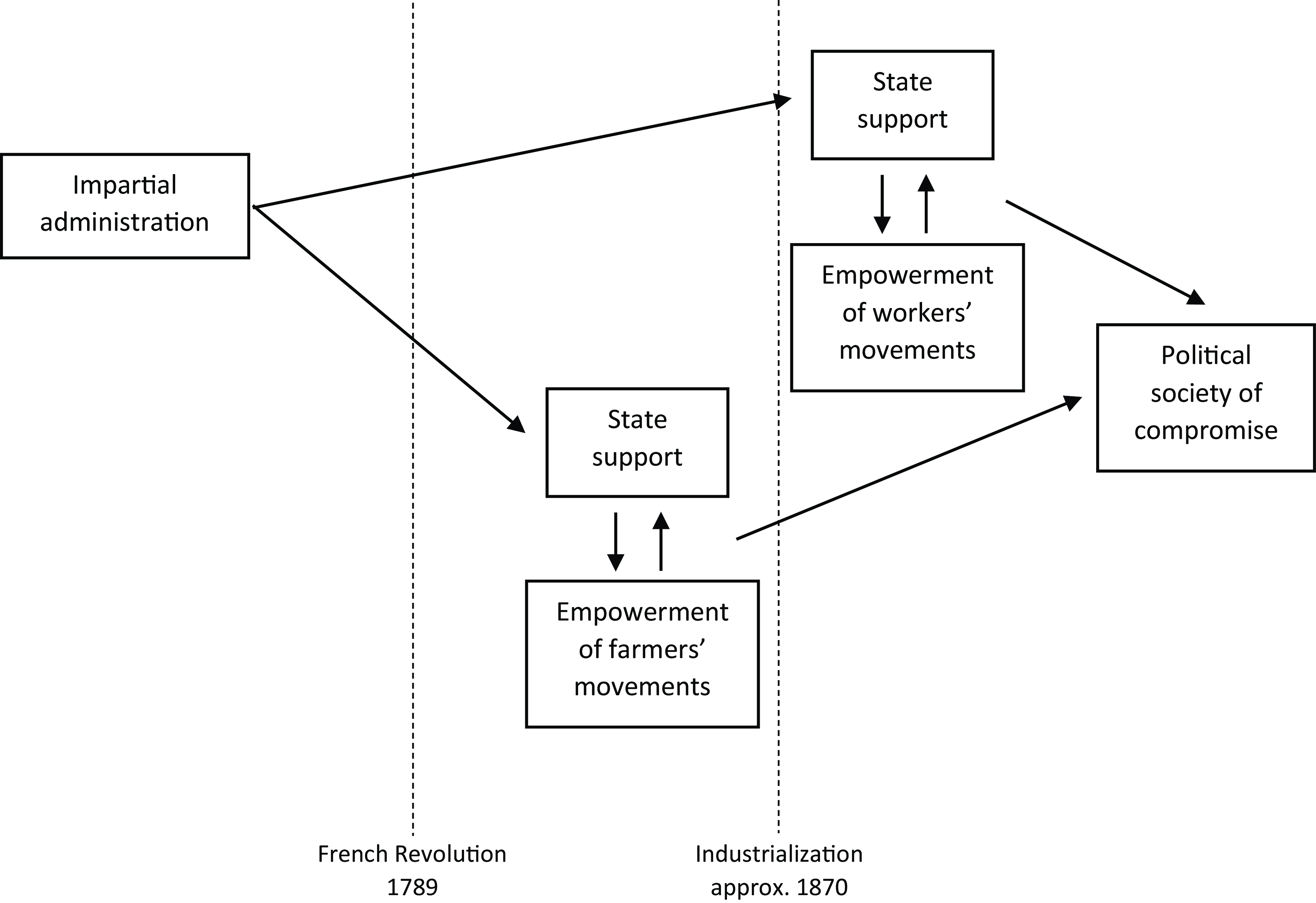

The next sections present within-case analyses of the three long nineteenth-century Scandinavian countries and Prussia. I examine the existence of the two mechanisms, structured before and during industrialization to focus separately on the associations and parties of farmers and workers. As shown in Figure 1, the results of the within-case analyses support the existence of the two mechanisms in all three Scandinavian countries.Footnote 6 Later, I show that the opposite mechanisms were present in Prussia.Footnote 7

Figure 1. Explanation of political society of compromise in Scandinavia.

The state and pre-industrial society

Denmark

The work ethics of both bureaucratic elites and local state officials in nineteenth-century Denmark focused on impartiality. Loyalty, integrity, and legality with a strong sense of responsibility for the state and its people were the key ingredients (Rüdiger Reference Rüdiger, Peder Pedersen, Ilsøe and Tamm1994: 51; Jensen Reference Jensen2013: 50). To some extent, these norms clashed with the state’s actual handling of revivalist movements. Neither wholehearted support nor uniform repression but rather a form of skeptical, tacit acceptance characterized the state church agency’s attempt to balance the mobilizing powers of the revivalist preachers against the loyalty of the clergy (Ingesman Reference Ingesman, Ilsøe, Knudsen, Ladewig and Tamm2000: 444; Sevelsted Reference Sevelsted, Brink Lund, Byrkjeflot and Christensen2024: 65). Although not necessarily intended to strengthen new religious movements, the state in practice tolerated them while standing firm on criminalizing the few movements, such as De Stærke Jyder, who wanted to break out of the state church (Ingesman Reference Ingesman, Ilsøe, Knudsen, Ladewig and Tamm2000: 445–46; see also Larsen Reference Larsen2022: Ch. 1).

The constitution of 1849 formally, and to a great extent in practice, secured freedom of religion and church, although it established a Lutheran-Evangelical state church. Partly because of pressure from peasant MPs, the state financially supported the folk high schools from 1851, adding grants for needy students from 1868 (Manniche Reference Manniche1969: 130). Despite initial skepticism in the Ministry of Education, it drafted what was passed as Sognebåndsløsningen in 1855, which ensured freedom to choose parish affiliation (Larsen Reference Larsen2022: Ch. 2).

Despite the initially stalling approach of the Danish state authorities, the interplay between Lutheran state officials and religious movements was relatively frictionless during the nineteenth century. Revivalists and even the Inner Mission to a great extent stayed within the Lutheran state church, while free-church societies thrived from cooperation with the state-supported folk high schools in a quasi-religious educational community (Gundelach Reference Gundelach1988: 110–11; Larsen Reference Larsen2014: 31–32).

Farmer–state political–economic relations developed in the same auspicious direction, albeit with more conflicts. The idea of urban and rural municipalities, respectively, created by law in 1837 and 1841, constituted a public–private partnership between state and farmers, formed among central-level bureaucrats from the 1820s to deal with emerging social tasks, notably the handling of the rural destitute (Kolstrup Reference Kolstrup, Henrik Petersen, Petersen and Finn Christiansen2010: 180–98). The municipal idea revealed tensions between liberal and conservative bureaucrats, but also the absolutist state’s sensitivity to public opinion, as the government presented its draft for an ordinance on municipalities and debated it in commissions from the early 1800s and with the provincial assemblies through the 1830s (Jørgensen Reference Jørgensen, Ilsøe, Knudsen, Ladewig and Tamm2000: 398).

Leading civil servants saw municipalities as providing channels of influence for peasants that would put them in charge of municipal councils and administration and exploit their associations to solve public tasks, thus making them into self-serving citizens. Likewise, the Chancellery developed a public school system in which each municipality substantiated its own school plans and organized teaching under state supervision – as settled in the Ministry of Church and Schooling after 1848 (Jørgensen Reference Jørgensen, Ilsøe, Knudsen, Ladewig and Tamm2000: 365). Finally, financing and running hospitals was decentralized to the municipal level from 1842, after negotiations between royal expert commissions and the provincial assemblies (Jørgensen Reference Jørgensen, Ilsøe, Knudsen, Ladewig and Tamm2000: 370), and the state granted loans to municipalities from 1838 to establish workhouses for the poor (Kolstrup Reference Kolstrup, Henrik Petersen, Petersen and Finn Christiansen2010: 208–44).

The state also directly supported and facilitated peasant-born economic growth. Based on similar motives as for the municipal arrangements, sporadic credit unions and savings banks were created by state initiative, frequently with civil servants as board members (Kaspersen and Ottesen Reference Kaspersen and Ottesen2001: 110–11). In 1846, the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural College led the removal of grain tariffs, making it cheaper for farmers to feed animals. Moreover, Næringsfrihedsloven of 1857 de facto abolished the guilds and guaranteed universal property rights and rights of association, making it possible to establish the first dairy cooperatives outside state control (Lampe and Sharp Reference Lampe and Sharp2018: 165).

The municipal acts accelerated associational density, triggering sick-help organizations, voluntary poor relief, and educational societies (Kaspersen and Ottesen Reference Kaspersen and Ottesen2001: 108–9; Lin and Carroll Reference Lin and Carroll2006: 348). Although mistrust of local officials certainly existed during most of the nineteenth century, peasants took great pride in their new public tasks, and municipal cooperation with the central administration was generally relatively well-functioning, suggesting that these institutional bonds tied peasants to the state (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009: 49; Stenius Reference Stenius, Alapuro and Stenius2010: 54–55). Likewise, the growth initiatives strengthened peasants’ economic autonomy and increased their tax payments, thus tying together the economic interests of peasants and state (Kaspersen and Ottesen Reference Kaspersen and Ottesen2001: 114; Clemmensen Reference Clemmensen2011: 289–91).

Explicitly political peasant movements were more severely repressed, but accommodation was often used, and legal guarantees almost always applied. The state elite constantly feared revolution from the 1810s to the end of the 1860s, from secessionism in Holstein to peasants and others demanding political rights or a Scandinavian union (Glenthøj and Ottosen Reference Glenthøj and Ottosen2021). The so-called Trykkefrihedsordningen, severely limiting freedom of speech, was discussed and fiercely defended by legal scholars and civil servants (Mchangama and Stjernfelt Reference Mchangama and Stjernfelt2016) and effectively implemented against strikes and journeymen’s associations in the 1810s, 1820s, and 1850s (Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018: 20; Karpantschof Reference Karpantschof, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018: 43–45).

However, the approach of the authorities was more balanced than purely repressive. Freeholder demands for some form of popular representation built up through the 1820s (Gundelach Reference Gundelach1988: 102–4), but the provincial assemblies were only established by the “granting” of the king and Chancellery as a preventive measure against revolution (Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018: 26). Communicating the state’s responsiveness to the people, the purpose was “for the King to present law drafts” on which the assembly deputies could “comment and propose” (Karpantschof and Mikkelsen Reference Karpantschof and Mikkelsen2013: 54, my translations). Let alone continued debate between liberal and conservative forces on how to deal with revolutionary pressure, the king’s attempt at reinstating censorship in 1834 and the so-called Bondecirkulæret of 1845 were quickly withdrawn. In both cases, the government calculated that it had to partner with the provincial assemblies rather than repressing them (Jørgensen Reference Jørgensen, Ilsøe, Knudsen, Ladewig and Tamm2000: 398; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009: 219).

Although Bondecirkulæret drove a wedge between king and people, a collection of academics, clergy, and Chancellery civil servants handled this threat by pushing the king to begin constitutional drafting in March 1848, becoming the first in Europe to react to the events in France. This at least temporarily satisfied the well-to-do farmers, who achieved the vote. More generally, the provincial assemblies of the 1830s and 1840s provided the peasantry with a repertoire of peaceful, collective action that lasted beyond 1848 (Karpantschof and Mikkelsen Reference Karpantschof and Mikkelsen2013: 55; Nørgaard Reference Nørgaard2023).

Norway

From 1814 to 1884, the central- and local-level civil servants in Norway were keen on being innovative while preserving the rule of law as guiding principle (Slagstad Reference Slagstad2011: 170–71). They managed the so-called Embetsmannsstaten, dominating policymaking processes via their expertise and membership of parliament, although checked by increasingly powerful peasant MPs and representatives of local commissions (Myhre Reference Myhre2018: 39). Although Norway’s 1814 constitution secured de jure freedom of religion (Jansson Reference Jansson1988: 334), it privileged the Lutheran-Evangelical state church as in Denmark, and the Conventicle Act criminalized free churches. Nevertheless, from the early nineteenth century, the state, as a matter of rational-minded care for the well-being of the people, was actively involved in forming early public–private partnerships by encouraging temperance movements to perform tasks neglected by official bodies, such as controlling commoners’ alcohol consumption (Sevelsted Reference Sevelsted, Brink Lund, Byrkjeflot and Christensen2024: 66). In turn, the temperance movements grew steadily and accepted state support, believing that care for alcoholics was better managed with government help (Kuhnle and Selle Reference Kuhnle, Selle, Gidron, Kramer and Salamon1992: 82). Tellingly, they always stayed within the Lutheran state church (Sevelsted Reference Sevelsted, Brink Lund, Byrkjeflot and Christensen2024: 66).

Much like in Denmark, a new generation of reformist, more liberal and scientifically oriented civil servants, born and raised in Norway, began superseding the old jurists and initiated a massive modernization of economy and society in the 1820s (Slagstad Reference Slagstad1998: 37). Although the conservative-liberal split within the bureaucracy remained vibrant throughout most of the nineteenth century (Gran Reference Gran1994: 132), liberals gradually won out. The Conventicle Act was lifted in 1842, and village and town municipalities were created in 1837. Negotiated in an expert-led commission (Den Store Lovkommisjonen) headed by state councilor Jonas Collett, the municipalities were granted unusual autonomy in view of tying peasants to public responsibilities and turning them into the state’s “right-hand man” (Hovland Reference Hovland, Næss, Hovland, Grønlie, Baldersheim and Danielsen1987: 32–33). Thus, under the control of the county governor, the common peasantry was reserved seats in local councils, which managed the economy, poor relief, public schooling, hospitals, and roads. Farmers, broadly enfranchised, chose representatives among the local population to act as judges, settlement commissioners, and commission members (Næss Reference Næss, Næss, Hovland, Grønlie, Baldersheim and Danielsen1987: 23–28). Over the next decades, the municipalities were granted more public tasks, cemented in the poor law of 1845 and the reformation of schools in 1860 (Dyrvik and Feldbæk Reference Dyrvik and Feldbæk1996a: 42; see also Bjerkås Reference Bjerkås2017: 478).

Pro-peasant growth policies complemented provisions of political influence as in Denmark. Aided by increasing influx of agriculturalists and engineers in the ministries, public support for infrastructure and industry accelerated from the 1850s, such as subsidizing fisheries, forestry and mining, and marine transport, as well as investing in postal and medicine systems, roads, and canals (Gran Reference Gran1994: 126). Additionally, civil servants were instigators of savings banks and credit unions in the 1820s, deliberately meant to help peasants become economically independent. The abolition of guilds in Håndværkerloven of 1839 and liberalizations in 1842 further enabled trade between towns and villages (Pryser Reference Pryser1999: 142, 156, 159).

These growth measures laid foundations for agricultural cooperatives and created common interests whereby bureaucrats reliably protected property rights in return for peasants’ hard work and ingenuity, filling the state coffers with tax incomes (Pryser Reference Pryser1999: 213–16; see also Sørensen and Mordhorst Reference Sørensen, Mordhorst, Brink Lund, Byrkjeflot and Christensen2024). Moreover, the state’s encouragement of voluntary organizations to take part in providing welfare services in cooperation with local governments further increased membership and strengthened organizational structures of temperance movements alongside educational and biblical societies (Jansson Reference Jansson1988: 334–36). Although peasants generally often identified themselves in opposition to the bureaucratic elites in parliament, numerous speeches of farmer MPs and petitions from local councils show how the municipal arrangements strengthened the farmers’ willingness to invest and work within the mainstream political system (Myhre Reference Myhre2018: 49, 297–306). In particular, the granting of political-administrative influence on and local rooting of welfare services were seen as major concessions from the old state elites, recognition of old peasant institutions, and proof of the effectiveness of the parliamentary system (Næss Reference Næss, Næss, Hovland, Grønlie, Baldersheim and Danielsen1987: 13; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009: 51; Stenius Reference Stenius, Alapuro and Stenius2010: 37–40).

As in Denmark, state officials contributed to auspicious political farmer–state relations in Norway. The 1814 constitution was structured by young civil servants, such as Supreme Court judge Christian Magnus Falsen, in coalition with farmers (Dyrvik and Feldbæk Reference Dyrvik and Feldbæk1996a: 188–89). Vicegerent Løvenskiold and his cabinet of top civil servants did orchestrate espionage, waves of arrests, and imprisonments against Thrane’s movement, but the purpose was to protect the unusually liberal-democratic constitution rather than some autocratic status quo (Myhre Reference Myhre2018: 139). While the legal grounds of Thrane’s own imprisonment were questionable (Kjeldstadli Reference Kjeldstadli, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018: 204), he was, quite remarkably given the strength of his movement, allowed three years of campaigning before imprisonment (Castles Reference Castles1978: 14), general rights of association and speech were never withdrawn, and state actions generally followed the law (Dyrvik and Feldbæk Reference Dyrvik and Feldbæk1996a: 189; Sevelsted Reference Sevelsted, Brink Lund, Byrkjeflot and Christensen2024).

The handling of Thrane’s movement is further illustrative of the appeasing effects of impartial administration. The creation of public schools from the 1830s taught the new generations of peasants and artisans to contribute to “the nation’s development” in civilized ways (Dyrvik and Feldbæk Reference Dyrvik and Feldbæk1996a: 127–29; Skinningsrud and Skjelmo Reference Skinningsrud and Skjelmo2016). While showing of pure military force occasionally worked preventively, Thrane’s strong oppositional agitation never disappeared until channeled via petitions and special workers’ commissions in the 1850s, which eventually led to debt reliefs and other smallholder aids, satisfying minimum demands for change (Dyrvik and Feldbæk Reference Dyrvik and Feldbæk1996a: 190).

Sweden

After the reinstallation of constitutional rule in 1809 in Sweden, state officials could not dominate the much older parliament as much as in Norway. Moreover, patrimonial recruitment patterns and corruption were more widespread. Nevertheless, state officials remained essential policymakers, and the majority of them respected the rule of law, considering themselves as contractually obliged to secure the freedom and welfare of the people (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009: 52).

Support for temperance movements was thus similar to that in Norway. The tentative beginnings of the movements were based on biblical societies funded by royal patronage in the 1800s and 1810s (Jansson Reference Jansson1988: 335). Furthermore, state clergy were active preachers in the Swedish Temperance Society, which was initiated by the leading conservative politician and state official Hartmansdorff from the 1820s (Kuhnle and Selle Reference Kuhnle, Selle, Gidron, Kramer and Salamon1992: 86; Sevelsted Reference Sevelsted, Brink Lund, Byrkjeflot and Christensen2024: 67). The Lutheran state church in Sweden generally played a more conservative role in clerical matters than in Norway and Denmark, resisting integration of free churches, but there is no evidence that the church actively counteracted the political-economic influence of farmers (Claesson Reference Claesson2004), and freedom of religion was codified and respected from 1860. Although some religious movements broke with a perceivably paternalistic state church, this was one of the reasons why state–farmer relations remained relatively peaceful (Micheletti Reference Micheletti1995: 32–33; Sevelsted Reference Sevelsted, Brink Lund, Byrkjeflot and Christensen2024: 67).

The stronger legacies of local peasant participation in Sweden meant that including more commoners in decision-making was less acute. Nevertheless, building on a centuries-old legacy of broad tax capacity and peasant-born local government, Swedish bureaucrats already from the first decades of the nineteenth century successfully consolidated peasants’ rights and duties in parish administration as part of modernizing the economy and building public services (Zink Reference Zink1957: 14–15; see also Nistotskaya and D’Arcy Reference Nistotskaya, D’Arcy and Steinmo2018: 47–48). The 1809 constitution preserved the parish meetings as providers of poor relief while making the state-ordained priest a born member to stabilize debates. By reform in 1842, parishes were required to establish a common school based on state finance and their own selection of school boards (Norrlid Reference Norrlid1983: 135; Westberg Reference Westberg, Westberg, Boser and Brühwiler2019: 195), voting procedures were formalized to secure the practical inclusion of freeholders, and subordinated boards were established to manage organizational issues (Scott Reference Scott1977: 352; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009: 233–34).

In several expert-bureaucrat commissions from the 1840s and 1860s, local self-government was presented as an administrative instrument to secure economic modernization and integrate rural populations. Liberal ideas to separate ecclesiastical from secular duties thus gained ground, resulting in a commission report that formed the basis for the establishment of municipalities in 1862 (Norrlid Reference Norrlid1983: 24; Åberg Reference Åberg2011: 57–62). The parishes were split in two communes, one ecclesiastical and another secular, each with their own policymaking and executive organs and overseen by the county governor. Directly elected county councils were established to secure compliance with general standards, intended not only to continue control of local government but also to strengthen conditions of the peasantry and channels for voicing complaints (Lidström Reference Lidström, Tanguy and Eymeri-Douzans2021: 263). While landlords could not capture the administration of elections, landlords certainly mistrusted freeholders and tenants and frequently used their socioeconomic powers to dominate local politics (Uppenberg and Olsson Reference Uppenberg and Olsson2022: 274, 282–83). In fact, although the 1862-reform installed broad and equal rights of participation, including for tenants, de facto voting rights depended on income and taxes until at least 1919 (Nydahl Reference Nydahl2010; Uppenberg and Olsson Reference Uppenberg and Olsson2022: 272). Yet, continued inequalities can hardly be blamed on the state administration.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the so-called harmoniliberale dominated politics and the state, liberalizing the economy based on rule of law principles (Nilsson Reference Nilsson1994: 27; Stråth Reference Stråth, Árnason and Wittrock2012: 57). Among them were civil servants, of which many were also members of the Diet, who saw it as a primary task to avoid state capture by sectional interests, primarily those of the peasant estate, and instead bridging conservative and liberal divides. Thus, the primary state organ on economic matters, Kommerskollegiet, retained its role as a brake on the most radical proposals but also increasingly valued “public” interests, which included those of industrious freeholders and merchants (Nilsson Reference Nilsson1994: 197).

State initiatives for economic modernization helped integrate peasants (Schön Reference Schön2012: 26–27). Town guilds were abolished in 1846 and extended to villages and the general population by 1864 (Scott Reference Scott1977: 410), the state financed country-wide railroads (Kilander Reference Kilander1991), a forest agency (Skogstyrelsen) of 1859 carefully regulated logging for the benefit of middle-sized and smaller farmers (Nilsson Reference Nilsson1994: 147), and the Royal Swedish Academy of Agriculture and models developed by the state-owned Hushållningssällskapen helped cooperatives to organize and peasants export their produce (Johansson Reference Johansson and Bager1985: 86). Top civil servants and county governors even frequently collaborated with entrepreneurs and signed applications for stock exchange listing, thereby forming and legitimizing emerging middle classes (Nilsson Reference Nilsson1999).

Due to remaining inequalities, local suffrage reforms did not significantly increase participation among peasants in rural communes until the decisive democratization in 1919 (Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson1989; Nydahl Reference Nydahl2010). However, freeholders in local councils, being able to positively form their own lives outside the church and school spheres, did express a new sense of autonomy and influence (Palme Reference Palme, Anderberg, Mehr, Petri, Thapper, Dahlman, Dahlgren and Järdler1962: 108; Åberg Reference Åberg2011: 51–52). Moreover, the fact that appeals over taxing or production rights to the county governor or King in Council often turned out favorably for the protesting landless brought the broader peasantry closer to the state because it established a mutually beneficial relationship (Stenius Reference Stenius, Alapuro and Stenius2010: 37–40; Uppenberg and Olsson Reference Uppenberg and Olsson2022: 286).

Initially, because of their old estate representation (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009: 213), handling the political demands of peasants in Sweden was more an assembly than a state matter. Nevertheless, direct farmer–state interactions did occur that reflected the state’s moderate approach. Police at least attempted to negotiate with crowd leaders on the day of Ambassador Axel Von Fersen’s assassination; riots in 1848 were repressed by a violent showdown of the police; the Tullberg movement died out as police arrested Tullberg himself; and food riots in 1867 were handled immediately by sending in armed guards to scatter violent crowds and more permanently as the magistrate established a weekly day for peasants to trade (Berglund Reference Berglund, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018: 294, 298, 303–4, 308). Finally, although the 1866 reform granted the aristocracy privileged positions, it also included farmers in the committee and commission system, which marked the legitimation by the state elite and tied the farmers to parliamentary politics (Valocchi Reference Valocchi1992: 195). Thus, in hindering revolutionary build-up, repression was important but almost always legally sanctioned, and negotiations and concessions were more often decisive in the longer term (Stråth Reference Stråth, Árnason and Wittrock2012: 73–78).

PrussiaFootnote 8

The handling of political society in Prussia originated in administratively privileged landed elites. The Stein–Hardenberg reforms of the early nineteenth century formally emancipated peasants, but the Junker landlords used their control over local administration and courts to preserve important ties to manorial land by contract and market competition without labor protection (Eddie Reference Eddie2013). Local self-government in municipalities was introduced in 1808, but political influence remained thoroughly oligarchal with few deliberative activities (Blackbourn Reference Blackbourn1998: 124; Caruso and Töpper Reference Caruso, Töpper, Westberg, Boser and Brühwiler2019: 49–55). This was augmented by the central administration’s conservative turn, beginning with the general pushback against associational rights in the Karlsbad decrees of 1819. From that point, resistance to allowing any liberal or peasant-born public sphere hardened (Anheier and Seibel Reference Anheier and Seibel2001: 38–39; Brooks and Guinnane Reference Brooks, Guinnane, Lamoreaux and Wallis2017: 302–6).

In turn, significant civic associations only formed by government initiative and control over the next decades (Tenfelde Reference Tenfelde, Bermeo and Nord2015: 113). Moreover, the political awareness and, thus, willingness to organize was limited by the lack of agrarian reform, which left much of the peasantry with a mixed subservient-reactionary attitude (Eddie Reference Eddie2013).

The restoration of absolutism in the 1850s put bureaucracy in charge politically, yet in a strengthened alliance with the landed elite of Junkers, which preserved de facto powers over local politics and administration (Gillis Reference Gillis1971: 163; Stern Reference Stern and Sprng2020: 55) and increasingly enrolled their sons into the central-level bureaucracy with similar conservative values rather than concerns for individual rights (Anheier and Seibel Reference Anheier and Seibel2001: 39; Stern Reference Stern and Sprng2020: 55–56). In turn, the police frequently engaged in arbitrary arrests, the state prosecutor’s office became a willing instrument of systematic political oppression (Gillis Reference Gillis1971: 156–60; Kocka Reference Kocka, Katznelson and Zolberg1986: 291), and local and central-level policy committees remained exclusively bureaucratic with no public participation or hearing (Beck Reference Beck1995: 128). As a result, although associations eventually mushroomed, they lacked political experience, alliances, and coherent programs, and only owned a dramatically decreasing respect for the state (Gillis Reference Gillis1971: 169; Anheier and Seibel Reference Anheier and Seibel2001: 38–44; see also Tenfelde Reference Tenfelde, Bermeo and Nord2015: 108–9).

Until German unification, state economic policies liberalized (Kocka Reference Kocka, Katznelson and Zolberg1986: 289) but focused on building major industries rather than supporting a diverse farming sector. Led by the Ministry of Agriculture, state support for agriculture was exclusively targeted at large-scale farms including protective tariffs (Koning Reference Koning1994: 53; Stern Reference Stern and Sprng2020: 59). Likewise, agrarian cooperatives were only allowed under the Reich Law of 1889 and, until then, faced shutdowns and officials’ harassment (Brooks and Guinnane Reference Brooks, Guinnane, Lamoreaux and Wallis2017: 314–15).

In pre-industrial society, I find support for both mechanisms: 1) state support for political societies, and 2) the empowerment and cooperation of these societies in return. Due to greater access to become freeholders and a more economically helpful and less repressive state, Scandinavian peasants built more autonomous organizations and achieved stronger political influence, most clearly at the national level.

The state and industrial society

Denmark

As everywhere else in Europe, the Paris Commune terrified the state authorities in Denmark. This was the background for banning the first meeting of the Danish International in 1872, dissolving the party by court ruling, and attacking worker demonstrations with military units at Slaget på Fælleden (Karpantschof Reference Karpantschof, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018: 47). More generally, governments did not shy away from employing police violence and arrests when gatherings of workers were deemed “revolutionary,” such as under the conservative Estrup governments, 1875–1894 (Bryld Reference Bryld1992: 147; Knudsen Reference Knudsen2006: 124). A gendarmerie was organized to confront rebels in several, sometimes violent, skirmishes while some opposition politicians and newspaper editors were imprisoned under provisional laws (Karpantschof Reference Karpantschof, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018: 51–52).

However, although many civil servants openly supported the conservatives in the late nineteenth century, no clear biases could be seen in the handling of worker movements. In the 1880s and 1890s, civil servants furthermore gradually withdrew from political agitation as their conservative inclinations and Estrup’s provisionary governments were questioned (Knudsen Reference Knudsen, Ilsøe, Knudsen, Ladewig and Tamm2000: 538, 547–48). Partly due to poorly functioning parliamentary channels and because civil servants in the Ministry of the Interior saw the most active worker associations at the time, the trade unions and later the Social Democratic Party, as outgrowths of rural popular movements rather than anarchists or dogmatic communists, shifting ministers and the civil service were rather more interested in accommodating the new organizations (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2006: 144–45).

Such state motivations drove the development of the welfare state, aimed at improving workers’ socioeconomic conditions, employment rights, and corporatist interest representation. The Ministry of the Interior began including unions in commission works from the 1890s and established a joint committee in 1898 to solve labor market conflicts (Due et al. Reference Due, Steen Madsen, Strøby Jensen and Kjerulf Petersen1994: 86; Knudsen Reference Knudsen2006: 144). A general lockout was solved in 1899 through state mediation with the so-called Septemberforliget (Grelle Reference Grelle2013: 14). This marked an era of collective agreements or settlements by arbitration, resulting in the government’s initiative, led by Jurist Carl Ussing, to establish a permanent court for industrial arbitration in 1910 (Hertz Reference Hertz, Ilsøe, Knudsen, Ladewig and Tamm2000: 455–57). Wage and working conditions were supposed to be settled between employers and employees, but a neutral public conciliator was appointed to mediate between the parties in case of deadlock. The government appointee sat as chairman while each party could elect a representative (Due et al. Reference Due, Steen Madsen, Strøby Jensen and Kjerulf Petersen1994: 86–88).

At the same time, the ministries continued building public services based on experiences from the municipalities. The period 1850 to 1901 saw an explosion of commissions of experts and civil servants working to improve health care and social security systems. The advent of workers and social democrats on the political scene accelerated concerns for solving challenges of urban poverty. Commissions thus anchored welfare provision for workers within the existing framework of municipalities and local administration in cooperation with civic associations; voluntariness rather than state control guided matters (Kuhnle Reference Kuhnle1983: 120–22, 132; Christensen Reference Christensen, Ilsøe, Knudsen, Ladewig and Tamm2000: 665–66). The policies included laws of the poor (1891), old age support (1891), health insurance (1892), and accident insurance (1898), provided universally yet after a means test (Andersen Reference Andersen, Petersen, Petersen and Christiansen2010). More often than not, civil servants drove policymaking processes and facilitated inter-party compromise. Leading examples include the official commission’s proposal for accident insurance, which was turned down in parliament in 1885 but later agreed on as the commission removed compulsion from the proposal (Lin and Carroll Reference Lin and Carroll2006: 354), and the farmers’ turn to the Commission on Workers’ Conditions in 1878 to harness funds for welfare expenses after which voluntary contributions were included as part of the funding (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1990: 66–67).

Workers’ political societies thrived in this environment. The stability of associational rights removed obstacles to their continued industrial and political organization, albeit within the legal, corporatist framework (Castles Reference Castles1978: 13). While the 1899 compromise confirmed workers’ right to organize, it also disciplined local units to follow the more predictable strike policy of the nationwide trade union (Bryld Reference Bryld1992: 46). Moreover, the Social Democratic Party’s adjustment to support democracy wholeheartedly was driven by broad-based ties of ordinary workers to public unemployment and health insurance funds managed by civil servants or trade unions under state supervision (Bryld Reference Bryld1992: 454). There were cases of administrative inefficiency, fear of anti-socialist laws, and hatred of the gendarmerie (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2006: 124), but union representatives and party leaders frequently expressed trust in parliament decisions and communicated this to their members, not least because of the reliability of municipal structures, the broad access to ministerial committees and commissions, and the institution of neutral state arbitration (Bryld Reference Bryld1992: 449; Hertz Reference Hertz, Ilsøe, Knudsen, Ladewig and Tamm2000: 453; Knudsen Reference Knudsen2006: 146; Christiansen Reference Christiansen2024: 32). The fact that workers could now rely on life-long state support further strengthened this support (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1990: 71).

In relation to the folk high schools and cooperative movements, the state continued its supportive approach from pre-industrial times, preserving also good relations with farmers. Several conservative governments feared the predominantly liberal schools. Yet, the permanent state inspector appointed to visit and control the folk high schools “was himself a true friend and a good defender of them” (Manniche Reference Manniche1969: 131). For instance, this meant that government failed where it based attempts to exclude from grants lists schools threatening public order on gut feelings (Manniche Reference Manniche1969: 131). Likewise, the state never put in place obstacles to farmers’ associations, even during the Estrup years. Instead, this period saw the first state-funded welfare aid to help farmers pay for the old and sick left in rural areas (Kaspersen and Ottesen Reference Kaspersen and Ottesen2001: 114; Sørensen and Mordhorst Reference Sørensen, Mordhorst, Brink Lund, Byrkjeflot and Christensen2024: 135–37) and the inclusion of rural interest organizations in the ministerial committee system (Bager Reference Bager1992: 359; see also Christiansen Reference Christiansen2024).

The relationship between folk high schools and the state grew even closer in 1892 with the passing of the first Folk High School Act, marking the state’s legal responsibility for supporting needy students. This weakened the schools as breading grounds for extremist political views (Manniche Reference Manniche1969: 132; Larsen Reference Larsen2022: Ch. 2). More generally, the relationship between agrarian and consumer cooperatives and the state gave way to reformist cooperation (Hilson Reference Hilson2019: 474). Finally, the immense success of the arbitration institution in settling industrial disputes and moderating worker tactics also strengthened the mobilizational basis for the consumer cooperatives (Grelle Reference Grelle2013: 14).

Norway

After the 1884 transition to parliamentarism in Norway, a system emerged in which party representatives filled parliamentary seats while civil servants withdrew from politics and generally acted impartially (Christensen Reference Christensen2003: 164–67). Socialist agitation was met with state repression, such as in scattered episodes in 1878, 1880, and 1892 where crowds were motivated by perceived socioeconomic injustices or rumors of police harassment. Yet, there was no evidence of systematic biases in police behavior. Moreover, the police, organized under the Ministry of Justice, only suppressed illegal and violent working-class activities, so there was no systematic effort to prevent a social democratic party from organizing (Gran Reference Gran1994: 139, 156; Kjeldstadli Reference Kjeldstadli, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018: 219–20).

In the early 1880s, Prime Minister Sverdrup formed a commission to address social problems among workers in particular (Dyrvik and Feldbæk Reference Dyrvik and Feldbæk1996b: 199). The aim was not only to contain ongoing waves of protest but also to build a more productive and harmonious working class (Kuhnle Reference Kuhnle1983: 120–22; Myhre Reference Myhre2018: 155–60). This resulted in laws for industrial supervision (1892) and accident insurance (1894) (Dyrvik and Feldbæk Reference Dyrvik and Feldbæk1996b: 199). Parliament’s permanent social committee, formed in 1894 of civil servants, experts, and party and interest group representatives, became the main forum for social policy formulation in the next decades (Espeli Reference Espeli2019: 42–44). Time and again, social policies came as reactions to employer–employee conflicts or worker protests, such as the passing of work environmental protection schemes in 1892 (Kuhnle Reference Kuhnle1983: 120–22; Falkum Reference Falkum, Engelstad and Hagelund2015: 58), and they were anchored in existing municipal and civic organizations (Myhre Reference Myhre2018: 160).

The development of corporatism was a few years delayed in comparison to Denmark, but the outcome and factors driving it were very similar. Triggered by strikes and lockouts, major employer–employee agreements (hovedavtaler) were made in 1902 and 1907, with state authorities as mediators, of which the latter (Verkstedsoverenskomsten) was the first general regulation recognizing arbitration courts. In 1916, this was institutionalized with the formal establishment of a national arbitrator institution, organized with a state-appointed mediator and interest group representatives (Falkum Reference Falkum, Engelstad and Hagelund2015: 60).

Between 1870 and 1920, the interest groups and parties of conservatives, liberals, and social democrats increasingly preferred social policymaking lifted beyond party competition with the state as the primary welfare provider rather than voluntary associations (Nerbøvik Reference Nerbøvik1999: 222–23). Yet, the state, specifically the municipal civil service and national arbitration organs, was rarely seen as outright paternalistic but rather as strong and impartial enough to take on the new tasks and solve political conflicts (Dahlen and Skirbekk Reference Dahlen and Skirbekk2020: 27–28). Not least, this was because the welfare policies secured social progress in the countryside as well as among urban workers. Moreover, the preservation of associational rights and the state’s mediating role ensured that the social democrats had the upper hand against the Marxist offspring of the worker movement (Gran Reference Gran1994: 50). Finally, it ensured that the moderate, reformist agrarian and consumer cooperatives had an overwhelming influence on politics (Castles Reference Castles1978: 13; Hilson Reference Hilson2019: 474).

Sweden

Several reforms in late 19th-century Sweden rooted out institutional corruption and aristocratic reservations for higher state offices and installed a neutral ministerial system, thereby indirectly consolidating meritocracy (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2011: 243–44). As industrialization also came a few years later and at a steeper rate than in Denmark and Norway, the state’s handling of emerging labor conflicts seemed more compressed and dramatic. Some examples indeed document this, but also the state’s impartial mode of operation. The Sundvall strike in 1879 was crushed by thousands of soldiers supported with reference to the old vagrancy laws, and the Åkarp law of 1899 punishing people for striking was implemented without judicial discrimination or harassment (Fulcher Reference Fulcher1991: 84). Confrontations between strikers and strikebreakers escalated numerous times, such as in Malmö and Norberg in 1890–1892. Although in Malmö, police protected strikebreakers and thus seemed to confirm its conservative leanings, it generally tried to address protesters peacefully on the basis of law provisions, and in Norberg, mediation dissolved the crowds and gave way to smaller pay cuts than initially planned (Greiff and Lundin Reference Greiff, Lundin, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018: 322–25).

Welfare expansions were even closer related to these revolutionary upheavals than in Denmark and Norway but were likewise driven by bureaucrats (Lundqvist Reference Lundqvist and Palm2013: 22–23). Parliament reacted to the Sundvall strike by setting up two commissions: the Workers’ Insurance Commission in 1884 and the New Workers’ Insurance Commission in 1891, famously composed of a dominion of professors alongside civil servants and representatives of employers and employees (Rothstein and Trägårdh Reference Rothstein, Trägårdh and Trägårdh2007: 236; Stråth Reference Stråth, Árnason and Wittrock2012: 68). Even if some leading MPs saw welfare as serving only conservative, preventive purposes (Scott Reference Scott1977: 415), the two commissions were established with liberal votes on the basis of humanitarian and social ideals and concluded accordingly that the state had the responsibility to universally protect workers from unemployment (Scott Reference Scott1977: 417; Rothstein and Trägårdh Reference Rothstein, Trägårdh and Trägårdh2007: 236). The commission’s first proposal on an old-age pension insurance favored the industrial elite. However, the parliament’s permanent committee system made sure that negotiations and debates kept going. Thus, with the Liberal Party government in 1905, the old-age pension reform was adjusted to accommodate criticisms of employees (Valocchi Reference Valocchi1992: 195).

What was later known as corporatism grew out of these commissions, leading the way to universal social and health insurance (Kuhnle Reference Kuhnle1983: 120–22). Notably, the Workers’ Insurance Commission proposed a new, universal insurance system for workers led by a new government agency with a corporate advisory board consisting of experts and representatives of both employers and employees in equal shares (Rothstein and Trägårdh Reference Rothstein, Trägårdh and Trägårdh2007: 237). This corporative arrangement then diffused to city and municipal governments and established arbitration institutions mediating employer–employee conflicts. Interestingly, social democrats were not the central actors behind these institutional innovations; rather, the permanent establishment of the corporatist principle with the National Board for Social Affairs in 1912 was initiated by the state-led National Board of Trade in the famous agreement, Decemberkompromissen, of 1906 between LO and the employers’ union, SAF (Rothstein and Trägårdh Reference Rothstein, Trägårdh and Trägårdh2007: 238–40; Bengtsson Reference Bengtsson, Millan and Saluppo2020: 72).

Compared with their counterparts in Denmark and Norway, the Swedish civil service was more closely affiliated with conservative interests. For instance, the so-called Munkorgslagen of 1889 that criminalized certain, often socialist, agitations as incitement of violence and subversion was drafted by the conservative bureaucrat, Minister of Justice Örbom (Bengtsson Reference Bengtsson, Millan and Saluppo2020: 66), and civil servant commission members tended to show some restraint in terms of social reform (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1990: 89). However, on balance, bureaucrats led the way in social policy innovations and their approach to state mediation and commission works showed that they had general interests in mind (Rothstein Reference Rothstein and Putnam2002: 20; Lin and Carroll Reference Lin and Carroll2006: 354; Lundqvist Reference Lundqvist and Palm2013: 22–23).

Blunt repression certainly contributed to pacifying revolutionary workers, notably in the early 1900s and the great 1906 industrial conflict specifically (Bengtsson Reference Bengtsson, Millan and Saluppo2020: 64–65). However, the state’s continued interventions and the establishment of arbitration boards and courts decisively showed a path for peaceful solutions to employer–employee conflicts, thereby rooting out remaining elements of dogmatic Marxism (Rothstein Reference Rothstein and Putnam2002: 296–98; Stenius Reference Stenius, Alapuro and Stenius2010: 59). Moreover, corporate interest representation contributed to the bureaucratization of party and union apparatuses, which facilitated the mobilization of pragmatic leaders and knitted together worker and state interests and mentalities (Olofsson Reference Olofsson1979: 20). Finally, corporatism was a form of repeated game that created path dependencies in which union representatives sought change within existing agreements and state-centered, civilized structures (Valocchi Reference Valocchi1992: 194; Greiff and Lundin Reference Greiff, Lundin, Mikkelsen, Kjeldstadli and Nyzell2018: 324).

The state’s more general approach to associations underpinned its specific relations with workers. Despite their many oppositional ideas, the popular meetings and rural and consumer cooperatives were celebrated and facilitated by state authorities, seen as a way of building a stronger national identity (Hilson Reference Hilson2019: 474). The creation of an agricultural ministerial agency in 1889 and a departmental superstructure in 1900 consolidated the corporatist arrangement with farmer organizations (Johansson Reference Johansson and Bager1985: 86). Moreover, the temperance movement became a crucial partner of the state in initiating the Bratt System or Systembolaget to control and ration alcohol consumption; the state funded education to members of cooperatives; and state assistance in the National Own-Home Fund of 1906 kept housing prices relatively low and available for common people (Brunnström, Håkansson, and Uppenberg Reference Brunnström, Håkansson and Uppenberg2021: 361).

The state’s signals related to popular meetings and the Bratt System affirmed religious groups that dialogue and participation could change governance structures (Stenius Reference Stenius, Alapuro and Stenius2010: 61). Corporate inclusion and the educational and housing initiatives made small farmers and unemployed choose to stay within the contours of the democratic popular meetings and cooperatives (Hilson Reference Hilson2019: 474). These forces, in turn, formed the conservative Swedish Farmers Union rather than some militant-fascist alternative (Bengtsson Reference Bengtsson and Wawrzeniuk2004: 149).

Prussia

The Junker-landed elite preserved de facto influence on local courts and privileged diet representation until 1918 (Holborn Reference Holborn1969: 255; Stern Reference Stern and Sprng2020: 59). This left the bureaucracy with the landed elite as a viable alliance partner against social democrats and accentuated its conservatism (Bonham Reference Bonham1983: 636; Stern Reference Stern and Sprng2020: 57–59). During the Bismarckian era in particular, the policies of the state bureaucracy tended to favor industrial at the expense of agrarian elites (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz and Eley1996), but this did not imply a strengthening of a freeholder class or bourgeoisie, and the bureaucracy, the Junkers, and big industry remained close allies in fiercely controlling workers (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz and Eley1996: 295; Smith Reference Smith2008: 229; Kocka Reference Kocka2018: 140).

Accordingly, state repression of workers was unforgiving. Assembly rights were scarce and police brutality and preventive surveillance was intense from the first strikes of the 1850s and 1860s (Tenfelde Reference Tenfelde, Mommsen and Husung1985: 207). Although some of these measures were lawful, there was systematic over-implementation. Among all German states, Prussia led this trend. Its police, staffed by the conservative jurists of the Ministry of the Interior who were employed in the restoration period, routinely, disproportionately, and often without specific grounds used harassment and prohibition against trade unionists, journalists, and editors with socialist connections (Guttsman Reference Guttsman1981: 60–61). The era of anti-socialist law (1878–1890) simply codified an accelerated version of this state-led policy (Berger Reference Berger1994: 26; Thomson Reference Thomson2022: 625). Thus, the application of these laws by Prussia’s predominantly noble Landräte constantly favored employers and rarely used arbitration courts (Hall Reference Hall1974: 366; Stern Reference Stern and Sprng2020: 59). Moreover, until World War I, these Landräte also worked as election overseers on behalf of the state, using their local social status to suppress voters and manipulate elections to the benefit of pro-government conservative and national-liberal parties at the expense of SPD and minority parties (Sperber Reference Sperber1997: Chs. 4–5; Anderson Reference Anderson2000: 39, 155–56).

Prussia also did not share the local and public anchoring of welfare policies with Scandinavia. The welfare progression of the 1870s was a solely preventive arrangement by Bismarck’s conservative, partly Junker-born bureaucracy to contain the socialist threat (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz and Eley1996: 295). Thus, the municipal and national consultation systems systematically favored and often only included representatives of big industry and large-scale farming, and private organizations and provincial administrations were excluded from policymaking and implementation processes (Holborn Reference Holborn1969: 256; Kuhnle Reference Kuhnle1983: 54–57). In turn, the pathbreaking national social insurance laws of the 1880s heavily favored industrial employers, tying benefits to employment at the expense of rights to strike and collective bargaining (Tenfelde Reference Tenfelde, Mommsen and Husung1985: 208; Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz and Eley1996: 295).

The anti-socialist repression had two effects. First, it weakened the organizational spread of trade unions and worker parties from localities to center, hindering strong voter associations, but primarily affected political strategies as workers resorted to blunt violence instead of peaceful negotiation (Guttsman Reference Guttsman1981: 58; Tenfelde Reference Tenfelde, Bermeo and Nord2015: 115–22). Second, the state bureaucracy, especially the courts and the police, came to be seen as instruments of the ruling classes and enemies of socialism, expressed in worker demonstrations, strikes, and trade union and (social democratic) party programs (Berger Reference Berger1994: 26–28). These were the emotions and rationalities that made the Communist Manifesto spread like wildfire in the factories, spurring revolutionary activity but also a strong party-wing of theoretical Marxism that for long hindered SPD’s entry into practical politics (Kuhnle Reference Kuhnle1983: 54; Tenfelde Reference Tenfelde, Mommsen and Husung1985: 209–14).