W. E. B. Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1903: 19) was famously prescient when he wrote, “[T]he problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” The hundred-plus years that followed were marked by searing conflicts over racial oppression. As hard-won political victories established new legal protections and more egalitarian norms, many hoped that racial inequalities would dissipate (Gamoran Reference Gamoran2001; Grusky and Szelenyi Reference Grusky and Szelenyi2014; Patterson Reference Patterson1997). The historical record of gains and reversals, however, has turned out to be far less straightforward. Few scholars today would deny that racial inequality remains a powerful feature of American life (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva1997; Massey Reference Massey2007; Omi and Winant Reference Omi and Winant1986). Alongside celebrated victories and new opportunities, research reveals ever-shifting patterns of racial subjugation and inequity (Bonilla-Silva and Ashe Reference Bonilla-Silva and Ashe2014; Dawson and Francis Reference Dawson and Francis2016; Klinkner and Smith Reference Klinkner and Smith1999; Reskin Reference Reskin2012).

Confronted with a complex historical record, how should scholars assess the evolution of American racial inequalities over time? Most research in this vein focuses on national trends in group resources and statuses. Important as it is, this story masks substantial differences across states and regions and ignores a fundamental structure of inequality in American life. Under federalism, the policies and practices that govern racial inequalities have always been subject to significant subnational control. Partly for this reason, the structure and severity of racial inequalities have varied greatly across regions, states, and localities. Despite the celebrated expansion of federal rights and protections in the 1960s, such variations remain, today as in the past, a basic structural feature of racial relations organized by a federal system of governance.

Against this backdrop, the field’s emphasis on aggregate national trends appears decidedly incomplete. In response, we measure racial inequalities in this study by aggregating individual-level data at the state level and analyzing subnational trends over time. This approach makes it possible to reveal distinct state and regional trajectories, capturing subnational shifts in racial configurations as well as dynamics of subnational convergence (or divergence) over time.

Our analysis also departs from the distributional conception of racial inequalities that typically frames trend studies in the field. Drawing on relational theories of racial inequality rarely used in quantitative studies, we pursue a novel approach to conceptualization and measurement. Departing from the distributional view of racial inequalities as differences in group possessions, we focus on the different positions that actors occupy in relation to one another and vis-à-vis the boundaries that organize social life (see e.g., Fox and Guglielmo Reference Fox and Guglielmo2012; Lamont and Molnár Reference Lamont and Molnár2002; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2014).

To do so, we conceptualize racial relations along two dimensions, each tied to a key mechanism in the reproduction of “categorical inequalities” (Tilly Reference Tilly1998). The first, exclusion, captures the degree to which a group is positioned inside or outside the boundaries that delineate and organize societal institutions and relations. The second, subordination, captures the degree to which a group occupies superior or inferior positions within these institutions and relations.

Focusing on the key domains of housing and work, we develop a novel framework for operationalizing group positions and measuring subnational trends in racialized group positions over time. Our state-level measures capture the relative positions of whites and blacks from 1940 to 2010, an era of critical transformation in black-white relations in the United States. This era includes the latter years of the Great Migration (Boustan Reference Boustan2016; Wilkerson Reference Wilkerson2010), massive social policy investments that disproportionately benefited whites from the 1930s to the 1970s (Fox Reference Fox2012; Katznelson Reference Katznelson2005, Reference Katznelson2013), uneven labor incorporation in the years surrounding World War II (Klinkner and Smith Reference Klinkner and Smith1999; Sugrue Reference Sugrue1996; Wright Reference Wright1985), the legal and socioeconomic achievements of the civil rights movement (Grofman Reference Grofman2000; Wright Reference Wright2013), and the dynamics of “advanced marginalization” that emerged as the black middle class grew and racial subjugation persisted alongside egalitarian laws and norms (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva1997; Cohen Reference Cohen1999; Wilson Reference Wilson1987).

Underscoring the value of a relational approach that attends to boundaries and positions, we find that between 1940 and 2010 racial inequalities rooted in boundary-based dynamics of social closure (i.e., exclusion) proved far more durable than inequalities tied to inferior positions alone (i.e., subordination). Underscoring the value of subnational analysis, we find a significant “nationalization” of US racial relations, in which the relative positions of blacks and whites have grown more similar across states and regions over time. This shift toward a more uniform structure of racialized relations, which has remained invisible in previous studies of national trends, has been driven by convergences both across regions and within regions.

Conceptualizing Racial Inequalities in Housing and Work

Housing and work play foundational roles in social stratification, positioning individuals in social relations, defining their access to opportunities, and shaping their life trajectories. Throughout the twentieth century, government policies and market practices limited where blacks could live (Katznelson Reference Katznelson2005; Massey and Denton Reference Massey and Denton1993; Roithmayr Reference Roithmayr2014) and set distinctive terms and conditions for black homeownership (Ross and Yinger Reference Ross and Yinger2002; Yinger Reference Yinger1997). The effects persist today through dynamics Daria Roithmayr (Reference Roithmayr2014) has compared to “monopoly lock in,” and can be seen in dramatic black-white inequalities in both average home value (Collins and Margo Reference Collins and Margo2003), and the rates, terms, and security of homeownership (Collins and Margo Reference Collins and Margo2011; Faber Reference Faber2013).

In the domain of work, long-standing patterns of occupational segregation and inequality have combined with shifts in the mix of available jobs (e.g., declines in manufacturing) to underwrite substantial racial differences in labor market opportunities and earnings (Fossett et al. Reference Fossett, Galle and Kelly1986; Tolnay and Eichenlaub Reference Tolnay and Eichenlaub2007; Wilson Reference Wilson1987, Reference Wilson1996). While dropping substantially after 1940, with notable progress following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, progress on the black-white wage gap began to stagnate in the 1980s and has persisted ever since (Couch and Daly Reference Couch and Daly2002; Donohue and Heckman Reference Donohue and Heckman1991; Grodsky and Pager Reference Grodsky and Pager2001; Smith and Welch Reference Smith and Welch1989; Wilson and Rodgers Reference Wilson and Rodgers2016).

Yet as scholars have documented these trends, few have stepped back to revisit two basic questions: What are racial inequalities, and how should one assess their evolution over time? These questions appear straightforward. Race, in the commonsense view, is a socially given attribute of groups and individuals. Whatever its historical origins, “race” in the United States refers, first, to a collection of social groups such as Native Americans, Asian Americans, whites, blacks, and LatinxFootnote 1 and, second, to an individual trait—that is, where an individual “belongs” among the racial categories. An “inequality,” in this view, refers simply to the uneven way some good is distributed across groups. The study of racial inequalities, then, entails determining group memberships and estimating how group possessions are distributed.

Scholarship in this tradition has been more than fruitful enough to demonstrate its value but, like any analytic approach, it advances some ways of understanding at the expense of others. In recent decades, a focus on distributive questions has isolated quantitative research in the field from relational approaches to racial inequalities that have become well established among social theorists (Emirbayer Reference Emirbayer1997) and historical and ethnographic sociologists (Desmond Reference Desmond2014; Somers Reference Somers1994). In relational analysis, “race” and “inequality” do not refer to attributes of actors or distributions of goods. Rather, they refer to the terms that organize social relations among actors (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004; Tilly Reference Tilly1998). From this perspective, for example, scholars ask how social and political practices construct social boundaries that delineate “racial groups”; how such boundaries distinguish racialized social kinds in “bright” or “blurred” ways; how some social objects and relations come to be viewed in racial terms while others do not; how social actors come to be perceived as belonging to particular racial groups; how the terms of racial relations regulate social interaction; and how these regulatory structures get reproduced and transformed over time (Alba Reference Alba2005; Barth Reference Barth1969; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004; Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz1998; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2014, Reference Wimmer2008).

Given the constructivist nature of this approach, it is not surprising that scholars have made less use of it in quantitative studies. Arguments that racial boundaries and groups constitute a shifting terrain are hard to square with analyses that measure racial attributes as stable values of a variable. In recent years, however, scholars have begun to question this opposition (e.g., Sen and Wasow Reference Sen and Wasow2016), as new studies have demonstrated the utility of statistical analyses for clarifying how racial classifications shift over time and racial identities get attributed in fluid ways (e.g., Saperstein and Penner Reference Saperstein and Penner2012). Here, we emphasize a complementary point: Relational theories offer powerful insights for the statistical analysis of racial inequalities that go beyond their emphasis on social construction and fluidity.

Most important for our purposes is the shift from studying distributions of goods to studying how actors are positioned in fields delineated and structured by social boundaries (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984, Reference Bourdieu1990; Fox and Guglielmo Reference Fox and Guglielmo2012; Lamont and Molnár Reference Lamont and Molnár2002). From this perspective, racial inequality can be empirically analyzed as a real social structure—a complex of boundaries and positions in which rules, norms, practices, and ideologies regulate relations between dominant and subordinate actors (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva1997; Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1990; Fields Reference Fields1990: 110; Wilson Reference Wilson1996: xii–xiv). Thus, scholars may ask how political life is structured in concrete ways by evolving “racial orders” (King and Smith Reference King and Smith2005), how racial structures reflect and shape the economic structures of capitalist relations (Cox Reference Cox1948; Dawson and Francis Reference Dawson and Francis2016), and how racial boundaries structure access and position across a wide range of institutional and informal arenas (Fox and Guglielmo Reference Fox and Guglielmo2012).

To pursue a relational approach to racial inequalities, one must adopt some framework for specifying the structure of relevant social relations. In this article, we draw on a long history of scholars who have distinguished two key mechanisms of inequality: exclusion and subordination. Elaborating on Du Bois’s (Reference Du Bois1903) concept of “the color line,” Herbert Blumer (Reference Blumer1965: 322) writes that “the color line expresses and sustains the social position of [racial] groups along two fundamental dimensions—an axis of dominance and subordination, and an axis of inclusion and exclusion.” Drawing on Blumer, empirical researchers can develop quantitative measures of relative group positions (1) vis-à-vis the boundaries of social institutions (exclusion) and (2) vis-à-vis one another as actors in structured fields (subordination). Rather than treating all racial inequalities as distributional matters of “more versus less,” one can identify the boundaries that delineate key arenas of social life and analyze unequal patterns of access and exclusion. Exclusion in this sense captures the degree to which groups can participate in an institution, whereas subordination captures relative placement within the institution.

Similar distinctions recur across leading efforts to theorize relational inequalities. Charles Tilly (Reference Tilly1998), for example, develops a general model of categorical inequalities rooted, on one hand, in Max Weber’s analysis of social boundaries and social closure and, on the other, in Karl Marx’s analysis of positioning in exploitative socioeconomic relations. Theorists of stigma, from Erving Goffman (Reference Goffman1963) to Glenn Loury (Reference Loury2002), stress the dual functions performed by discrediting markers: establishing boundaries that exclude actors with “spoiled identities” and defining hierarchical terms for social interaction. Claire Jean Kim (Reference Kim1999) similarly argues that the “field of racial positions” in American culture operates along the dual dimensions of “civic ostracism” (a form of exclusion) and “relative valorization” (a form of subordination). Cathy Cohen (Reference Cohen1999) conceptualizes “marginalization” in terms of exclusion from dominant institutions and in terms of subordination within such institutions.

Drawing on this distinction, then, we develop separate measures of positions defined by social boundaries (exclusion) and relative positions within a given field (subordination). In so doing, we make a deliberate effort to bridge the gap between distributive and relational approaches to the study of racial inequalities. Relational theories are typically and appropriately paired with relational methodologies, such as social network analysis or relational ethnography. As we show, however, the relational theorist’s emphasis on relative positions can also provide a distinctive basis for statistical analyses of inequality trends.

Racial Inequalities in a Federal System

In addition to clarifying and operationalizing “racial inequality,” empirical researchers must also confront a second question: At what level of scale should one observe its variations over time? Different levels of analysis yield distinctive insights, with a richer overall portrait emerging as scholars complement national trends in household and individual inequalities with evidence regarding neighborhood patterns (Sampson Reference Sampson2012; Sharkey Reference Sharkey2013), organizational dynamics (Stainback et al. Reference Stainback, Tomaskovic-Devey and Skaggs2010; Tomaskovic-Devey Reference Tomaskovic-Devey2014), and population-level process (Bloome Reference Bloome2014; Maralani Reference Maralani2013).

Scholars typically use summary measures of individual- or household-level data to analyze aggregate trends and draw conclusions about changes in racial inequalities across the nation as a whole. Important as it is, this national story obscures important subnational differences and ignores two essential features of American inequality. First, the United States has a federal system of governance in which variations across subnational units are the norm. As Aaron Wildavsky (Reference Wildavsky1985) famously put it, “federalism means inequality” across jurisdictions. The state in which one resides has significant consequences for one’s opportunities and life conditions and, as we shall see, for the structure of racial relations one must traverse.

Second, as a historical matter, the governance of racial inequalities in America has always been subject to significant subnational control. Historically, state governments have played a critical role in defining racial categories and policing their boundaries. Thus, in nineteenth-century America, for example, the racial conceptions, categories, and regulatory norms constructed in Alabama (Novkov Reference Novkov2008) differed considerably from the frameworks created in nearby Louisiana (Dominguez Reference Dominguez1986). As Julie Novkov (Reference Novkov2008: 13) explains in a critique of nationally focused scholarship on American citizenship:

When we note that for most of the history of the United States, such significant issues as voting, education, marriage, familial relations, and residence have been primarily within the province of state law, we see that the states are far from irrelevant in establishing the grounding context for citizenship and identity, especially when the focus is on subordinated identities and their legal status. This matters if we wish to understand race and the legacy of formal racial subordination in the United States. The bargain on race worked out after the end of the Reconstruction era was to allow local (meaning state-based) control over race relations.

Partly for this reason, regional differences have played a central role in American racial relations from the slavery era of the early Republic to the present day. The distinctive racial history of the South provides only the most glaring example (Katznelson Reference Katznelson2013; Key Reference Key1949). In the twentieth century, racial rule in the Southwest (Fox Reference Fox2012) followed a different logic than urban systems centered on housing segregation in the North (Gordon Reference Gordon2008; Hirsch Reference Hirsch1983; Sugrue Reference Sugrue1996). “Categorical mechanisms of racial inequality prevailed throughout the United States until the 1960s, [but] the means by which exploitation and exclusion were achieved differed in the North and the South” (Massey Reference Massey2008: 55).

Regional differences can be traced, in part, to the policy authority subnational jurisdictions possess under a federal system. Subnational control has been a signature feature of criminal justice and welfare policies, for example, which have long played outsized roles in governing racial relations and exhibit highly racialized patterns of state variation (on welfare, see e.g., Fellowes and Rowe Reference Fellows and Rowe2004; Fox Reference Fox2012; Lieberman 1998; Soss et al. Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011; on criminal justice, see e.g., Beckett and Western Reference Beckett and Western2001; Yates and Fording Reference Yates and Fording2005). Indeed, from housing (Goetz Reference Goetz2013; Massey Reference Massey2007, Reference Massey2015) to education (Orfield et al. Reference Orfield, Frankenberg, Ee and Kuscera2014; Reardon and Owens Reference Reardon and Owens2014) to labor markets (Glenn Reference Glenn2002; Wilson Reference Wilson1987, Reference Wilson1996) to tax systems (Einhorn Reference Einhorn2008; Newman and O’Brien Reference Newman and O’Brien2011), and beyond, the key policy tools that regulate racial inequality in America have remained subject to significant state and local control. Federal interventions, such as those won by the civil rights movement, remain exceptions to the rule, imposing limits on state and local modes of governance that organize racial relations in more primary and proximate ways.

In response, we investigate racial inequalities by aggregating individual-level data at the state level. This approach illuminates distinctive state and regional trajectories, clarifies state and regional dynamics of divergence and convergence, and produces summary estimates of national trends that capture the shifting of populations across state regimes over time.

Data and Measures

In any social field, analysts will find a number of boundaries and statuses that could serve as a basis for exclusion, as well as various axes of position relevant to subordination. Acknowledging that valid alternatives exist, and no measure will be exhaustive, researchers should select boundaries and axes based on assessments of (1) their significance for social inequalities and (2) data availability and quality. Our measurement choices reflect tradeoffs among these considerations, seeking to produce valid indicators of significant inequalities sufficient to illustrate the utility of a relational approach. Toward this end, we use data from the US Decennial Census, 1940–2010, to create state-level measures of subordination and exclusion for blacks and whites in the domains of work and housing.

Guided by theories of social closure, we measure exclusion in each domain by specifying a socially meaningful and regulatory institutional boundary and then estimating the relative degree to which black and white state residents have been able to traverse it. In the area of work, full-time employment provides a key threshold in “the quest for inclusion” (Shklar Reference Shklar1991) and economic citizenship (Kessler-Harris Reference Kessler-Harris2003), which animated the two marches on Washington (Chen Reference Chen2009; Jones Reference Jones2014). To measure access to full-time employment, we rely on the employment-to-population ratio in each state-year, which indicates the proportion of each racially defined population, 16 and older, that is working full-time. In the area of housing, homeownership marks access to property and operates societally as a “moral nexus between liberty, privacy, and freedom of association” (Radin Reference Radin1982: 991). Our exclusion measure compares homeownership rates in a given state-year for whites and blacks, 25 years and older.

To measure relative positions within the work domain (subordination), we rely on median levels of wage and salary income for individuals 16 years and older. For housing, we calculate median values of homes owned by blacks and whites 25 years and older.Footnote 2

Following relational theories’ emphasis on relative positions, we construct state-level ratios (e.g., the white homeownership rate in California divided by the black homeownership rate in California). On the resulting measures, numbers greater than one indicate the degree to which whites occupy a superior position relative to blacks.

Because they capture varied aspects of a common construct (i.e., state-level racial inequality), our measures should be seen as rooted in shared social processes. Consider, for example, how residential segregation might matter for housing exclusion (diminishing black access to ownership) and subordination (channeling black owners into lower-value neighborhoods) and also for work subordination and exclusion (through the effects of spatially organized labor markets). One could likely tell a similar story of shared origins for education. The measures employed here can be seen as products of complex, interrelated causal configurations. But these social origins are not the subject of our analysis and have little bearing on whether a given measure offers a valid indicator of relative positions in a field.

Likewise, measurement validity in the present study stands independent of the empirical relationships observed among indicators. Subordination and exclusion may work together as a tight configuration in one instance yet work quite independently in another (Tilly Reference Tilly1998). But the observed correlation between two variables (e.g., education and income) has little bearing on how well the two constructs can be distinguished and measured. The analytic distinctions between exclusion and subordination, and potential for valid measurement of each, do not depend on their empirical relationship in any particular time and place.

Research Strategy

Our analysis proceeds in three parts. We begin by describing overall levels and trends of white-black subordination and exclusion, as indicated by 50-state median values. These values reveal central tendencies among states, as opposed to more familiar estimates for national populations. In creating national-level estimates, scholars rightly account for the fact that California’s population is more than 23 times the population of Idaho. In contrast, because our goal is to analyze differences in racial positions across political jurisdictions (i.e., states), we follow the norm in scholarship on US federalism, treating California and Idaho as distinct and equal units of analysis.Footnote 3 In this manner, we estimate state-level trends in racial subordination and exclusion, compare magnitudes of change across these dimensions, and clarify the extent to which changes in relative measures reflect developments for blacks versus whites. State-level measurements across multiple decades also allow us to distinguish exclusion and subordination and assess changes in their relationship to a degree that would not be possible with a single national-level estimate observed at multiple time points.

We then examine patterns of convergence and divergence. Due to political, ideological, demographic, and economic differences, state’s regimes often move in different directions over time (Gelman Reference Gelman2009). Yet states are also subject to shared national and global pressures that promote conformity (Lieberman and Shaw Reference Lieberman and Shaw2000). In the present study, both dynamics should be expected. The terms of American federalism changed considerably over the period from 1940 to 2010. Federal laws, judicial opinions, and administrative rules imposed powerful new constraints on racial relations in the states, creating an environment less hospitable to subnational variations (Derthick Reference Derthick2001). At the same time, a prolonged era of policy devolution worked to expand possibilities for subnational variation (ibid.).Footnote 4 To explore the products of these conflicting developments, we use the coefficient of variation (COV, a measure of variability relative to the mean) to analyze the extent to which state patterns of subordination and exclusion have converged over time under a national framework of rights and protections or, alternatively, diverged from one another under the expanded state freedoms of policy devolution.

The final analysis examines regional differences in state trajectories.Footnote 5 A variety of developments—the Great Migration, the demise of Jim Crow, the nationalization of party politics, and so on—suggest that the regional patterning of racial inequalities in the United States may have changed considerably over time. Have trends across the 50 states been driven more by some regions than others? To what extent have the trends reflected changes in within-region heterogeneity versus changes in between-region differences? To what extent have shifting racial positions (inequalities) tracked differences in racial compositions (population sizes) across regions? To address these questions, we analyze region-specific trends, analyze how these trends correlate with the size of the black populations, and, finally, use ANOVA to decompose variance in each decennial census year to isolate within- versus between-region changes.

Empirical Results

State Levels and Trends, 1940–2010

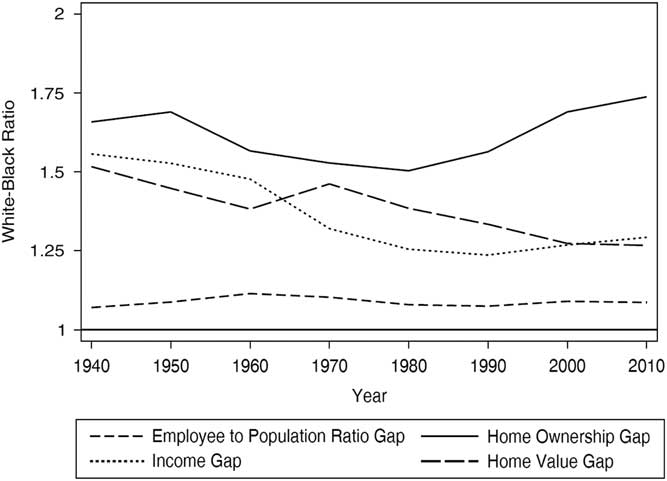

We begin with state-level trends. Figure 1 shows median state values for subordination and exclusion in housing and work, 1940–2010. Table 1 offers elaboration by providing separate 50-state median values for whites and blacks, 50-state median values for inequality ratios (i.e., subordination and exclusion), and the absolute and percentage changes across three time points: 1940, 1970, and 2010.Footnote 6 Perhaps the most striking pattern is the durability of racial exclusion in each domain, relative to more substantial reductions in racial subordination.

Figure 1 Trends in racial exclusion and subordination, 1940–2010 (50-state median).

Source: US Decennial Census Data.

Table 1 Exclusion and subordination: 50-State Median over Time for Selected Years

Source: US Decennial Census.

Note: The 50-state median ratio represents the median state’s white-black inequality ratio. All dollar values (for wages and home values) are inflation adjusted to appear in 2010 dollars.

From 1940 to 2010, homeownership rates increased substantially for blacks, whose 50-state median rose from 34 to 44 percent, and for whites, whose median rate grew from 55 to 76 percent. These trends likely reflect the growing effects of the Federal Housing Administration and the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 (Collins and Margo Reference Collins and Margo2011; Massey Reference Massey2015). The relative positions captured by our measure of housing exclusion, however, held steady. After falling less than 7 percent, 1940–70, exclusion rose by almost 14 percent, 1970–2010, yielding a net change of only 6 percent. Indeed, the 50-state median ratio of white-black homeownership rates rose from 1.63 in 1940 to 1.74 in 2010. Recent events, such as the disproportionate targeting of black communities in predatory lending practices, may help explain why greater progress has not been made in this area (Faber Reference Faber2013; Rugh and Massey Reference Rugh and Massey2010).

Racial inequalities in full-time employment exhibit even greater stability, with slight increases for both blacks and whites yielding just a 2 percent change in work exclusion from 1940 to 2010. This persistence of relative positions likely reflects a number of factors, including differential access to employment opportunities, hiring discrimination, and occupational segregation (Gradin et al. Reference Gradín, Río and Alonso-Villar2015; Shepard and Pager Reference Shepard and Pager2008; Wilson Reference Wilson1987).

In sum, exclusion-based racial inequalities have proven remarkably durable across the labor-market and housing domains, even as both groups attained absolute gains in homeownership and full-time employment rates. Boundaries regulating access to significant housing and work statuses operated with about as much racial skew in 2010 as in 1940.

By contrast, levels of housing and labor market subordination fell significantly from 1940 to 2010. Racial wage inequalities declined during the years of broadly shared prosperity that marked the heyday of postwar growth, 1940 to 1970 (Goldin and Margo Reference Goldin and Margo1992), before suffering from disproportionate black losses in the era of deindustrialization (Wilson Reference Wilson1996). Across the whole period, 1940 to 2010, black median-wage increases (54 percent) outpaced white increases (32 percent), reducing labor-market subordination by 16 percent. Housing subordination also declined by 16 percent over this period—mostly after 1960, due to the durable impact of residential segregation on housing assets (Collins and Margo Reference Collins and Margo2003).

Reasonable people may disagree about whether a decline of 16 percent is “substantial” relative to the goals and expectations of racial equality. But the considerable contrast of trends for exclusion and subordination in these two areas underscores both (1) the value of a relational approach to gauging changes in group positions and (2) the potential for analytic distinctions between subordination and exclusion to yield empirical insights. In this instance, we see that racial inequalities rooted in boundary-based exclusions proved far more durable than inequalities tied to subordinate positions alone.

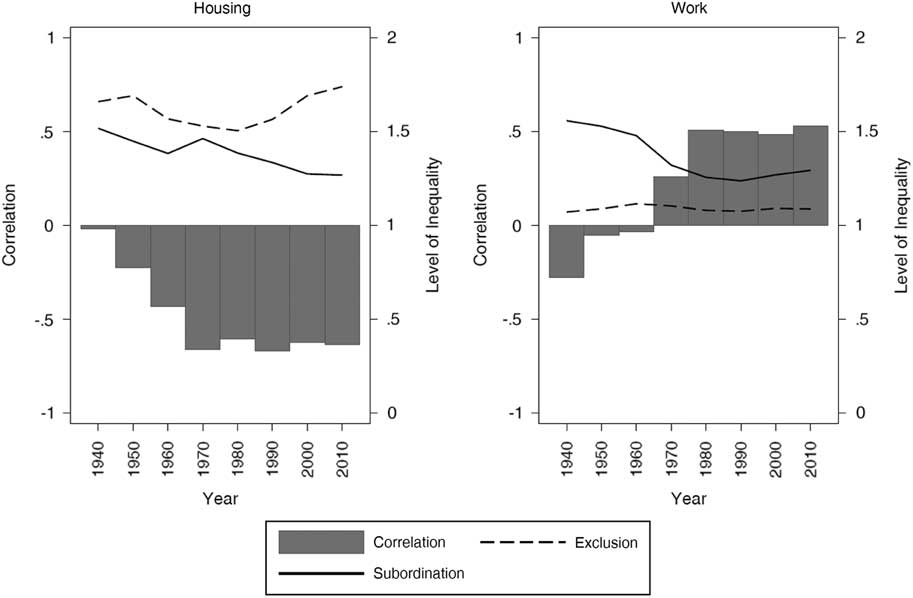

Indeed, the relationship between subordination and exclusion within each domain (housing, work) is either equivalent or weaker than the relationships between analytically defined measures across domains (e.g., housing subordination and labor subordination). Throughout the whole period, 1940–2010, exclusion and subordination exhibit only modest correlations within each domain (housing r=−0.26, work r=0.04) compared to the correlations within each dimension (exclusion r=−0.02, subordination r=0.67). Further, the within-domain correlations also vary greatly in their associations over time. Figure 2 displays correlations in each domain, 1940–2010. For work-based exclusion and subordination, for example, the negative relationship observed in 1940 (r=−0.28) becomes positive by 1970 (r=0.26) and then strengthens by 2010 (r=0.53). Thus, by the end of this period, states with larger racial inequalities in full-time employment had become also far more likely to exhibit larger racial inequalities in wage/salary income. For housing, by contrast, substantial independence in 1940 (r=−0.02) gave way to a strongly negative association by 1970 (r=−0.66), which remained through 2010. Over time, then, states with more racially unequal patterns of homeownership became less likely to exhibit higher levels of racial inequality in the values of owned homes.

Figure 2 Within domain correlations and trends in racial exclusion and subordination.

Source: US Decennial Census Data.

These patterns reinforce the view that subordination and exclusion can operate as distinct but interrelated dimensions of racial inequality, providing a robust analytic basis for assessing how racial inequalities vary in their structures and evolve over time. Absent this distinction, the observed trends might be easily viewed as a jumble of contradictory results. By drawing on relational theories of unequal positioning, however, one can see a more coherent pattern of evidence in which axes of inequality (exclusion, subordination) share historical trajectories to a greater degree than domains of inequality (housing and work). Moreover, instead of finding false comfort in a story of modest progress (based on subordination trends alone) or despairing over the absence of change (based on exclusion trends alone), scholars are forced to grapple with a varied and nuanced historical record in which social and institutional boundaries have made some forms of racial inequality more resistant to change than others.

State-Level Variation and Convergence, 1940–2010

As federal involvement in civil rights grew, did states converge on a shared structure of racial relations? Or alternatively, did the growing embrace of policy devolution pave the way for greater state divergence? To illuminate such dynamics, we use the COV to estimate levels of cross-state variability over time.

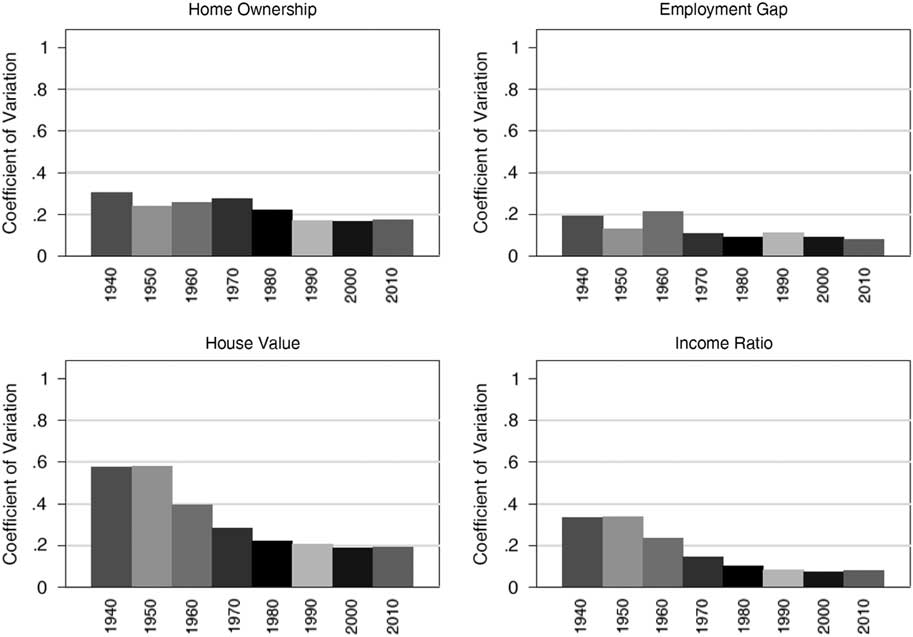

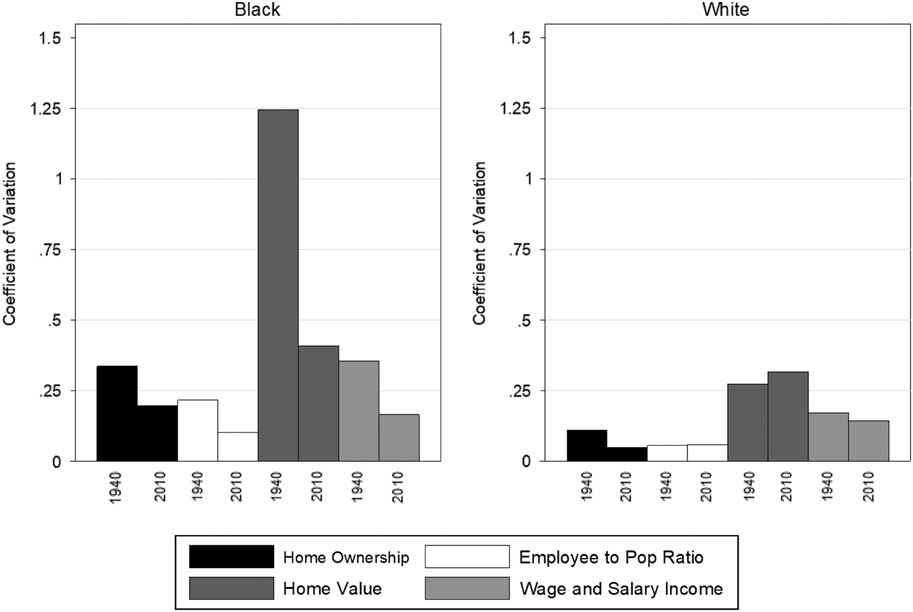

Figure 3 shows trends in cross-state variability for subordination and exclusion in housing and work from 1940 to 2010.Footnote 7 Cross-state variation clearly declined from 1940 to 2010, along both axes of inequality (exclusion, subordination) and in both domains (work, housing). Convergence, however, was greater for subordination than exclusion. Cross-state variation in housing exclusion (homeownership) only declined from 0.31 in 1940 to 0.18 in 2010 (an absolute decline of 0.13), as variation in housing subordination (home value) declined from 0.57 in 1940 to 0.19 in 2010 (an absolute decline of 0.38). Cross-state variation in work exclusion (full-time employment) declined from 0.20 in 1940 to 0.08 in 2010 (an absolute decline of 0.12), as variation in work subordination (wages) fell from 0.33 to 0.08 (an absolute decline of 0.26). In percentage terms, state variation in subordination fell by 66 percent (housing) and 76 percent (work), while differences in exclusion fell by just 43 percent (housing) and 59 percent (work).

Figure 3 Trends in cross-state variation in racial exclusion and subordination, 1940–2010 (coefficient of variation).

Source: US Decennial Census Data.

Two points merit note here. First, the contrast between exclusion and subordination observed earlier for median trends holds for variability trends. In every decade and across both domains, we observe greater variation (a larger COV) for subordination than for exclusion. Moreover, cross-state variations declined far more for subordination than exclusion (29 percent more for work, 56 percent more for housing). Second, on the exclusion dimension, declines in variation (COV) exceed declines in level (median-value ratios). For work exclusion, 1940–2010, the COV falls 59 percent, while the median ratio declines by only 2 percent. For housing exclusion, the COV falls by 43 percent, while the median ratio declines by just 6 percent.

Together, these trends suggest that boundary-based racial inequalities (i.e., exclusion) went through a process of consolidation, 1940–2010, converging around relatively stable levels of inequality. Patterns of racial subordination, by contrast, exhibited a more fluid process of equalization—that is, greater convergence around larger reductions in inequality.

The contrasting patterns of consolidation and equalization clearly illustrate the empirical value of a relational theoretic approach. In more substantive terms, however, did declines in cross-state variation represent a nationalizing trend toward uniformity in the absolute positions occupied by blacks? To answer this question, figure 4 presents trends in cross-state variation separately for blacks and whites. Indeed, declining state differences in the positions occupied by blacks account disproportionately for state convergence in racial inequalities over this period. Across all four measures, black residents’ positions exhibit less cross-state variability over time and, in every case but one, declining variation in black positioning contrasts with greater persistence among whites.Footnote 8 Consistent with our other results, convergence over time in black positions is also greater for subordination than for exclusion.

Figure 4 Coefficient of variation by race, 1940–2010.

Source: US Decennial Census Data.

In sum, racial inequalities became substantially more uniform across the states, 1940–2010—as political changes (especially the collapse of Jim Crow and dramatic growth of federal involvement) combined with demographic changes in an era of sustained internal migration. Indeed, across the whole period, percentage changes are far greater for cross-state variability (i.e., 50-state COV values) than for levels of inequality (i.e., 50-state median values). This point bears special note because the greater form of historical change in this period, convergence, cannot be observed in studies that rely on aggregate national data alone. The same may be said for the contrast of “consolidation” and “equalization” observed here, which reinforces the view that exclusion has proved to be “stickier” over time than subordination.

Regional Levels and Trends, 1940–2010

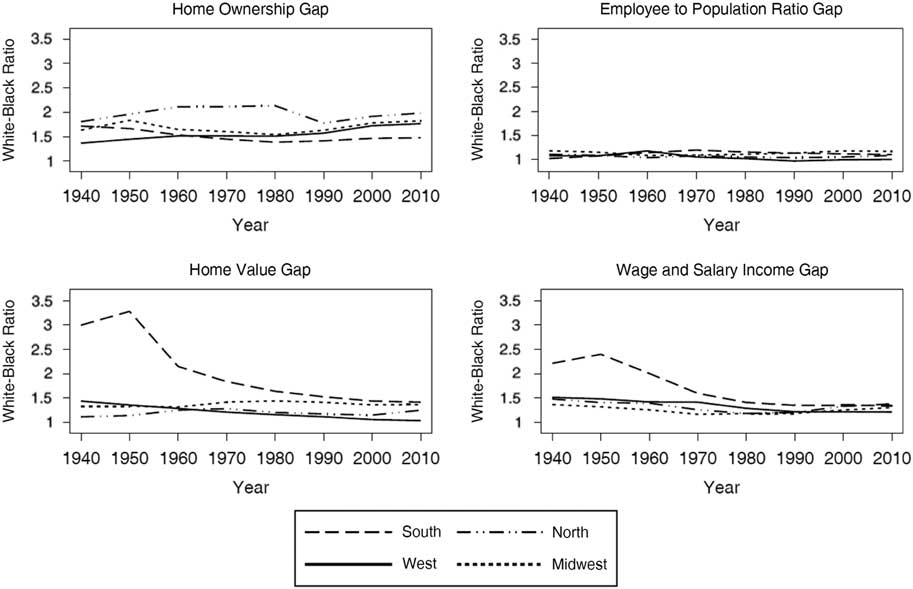

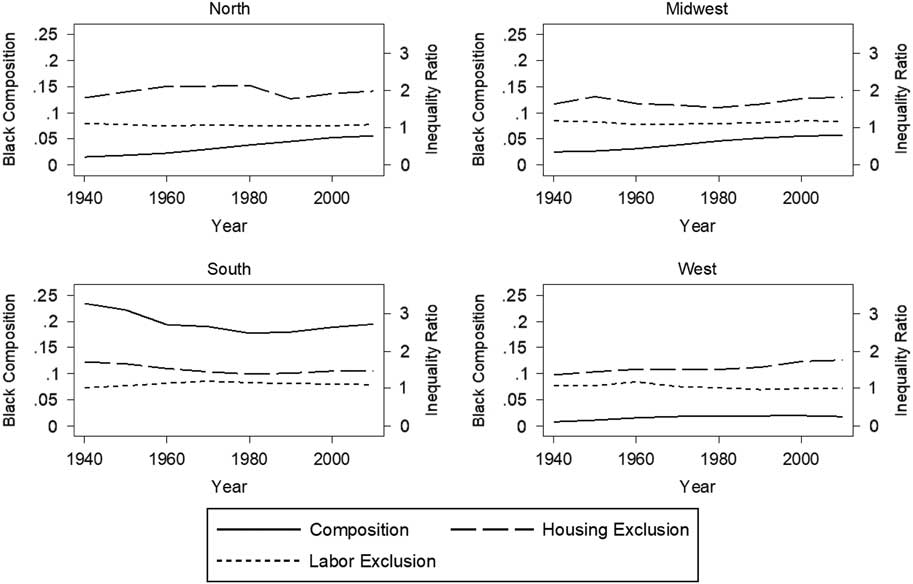

To what extent do region-specific changes help to explain the observed national patterns of state-level convergence? To explore this question, figure 5 shows region-specific medians for exclusion and subordination in housing and work (see table 2 for specific values for 1940, 1970, and 2010 and absolute and percentage change).

Figure 5 Regional trends in racial exclusion and subordination.

Source: US Decennial Census Data.

Table 2 Exclusion and subordination: Regional medians over time for selected years

Source: US Decennial Census.

Note: The regional median ratio represents the median state’s white-black inequality ratio within each region. All dollar values (for wages and home values) are inflation adjusted to appear in 2010 dollars.

Turning first to subordination, we can see that the trends toward convergence reported in the preceding section were primarily driven by the declining distinctiveness of the South. In both domains of inequality, levels of subordination declined in the South by roughly twice as much as in any other region (39 percent for work; 53 percent for housing). Because the South began the period with such high levels of subordination, disproportionately large declines brought the South into line with other regions. In 1940, median wage/salary incomes and home values among southern whites ($18,107 and $51,597, respectively) were more than double those of southern blacks ($7,882 and $15,576, respectively). Subsequent declines in southern inequalities were driven more by black advancement than white decline, with blacks experiencing a nearly 150 percent increase in wage/salary income from 1940 to 2010 ($7,882 to $19,492) and a striking 421 percent increase in home values ($15,576 to $81,125). Even with these absolute improvements, however, southern blacks in 2010 continued to fare worse than blacks elsewhere in the United States in both domains, and subordination in the South remained either the highest (housing value) or second highest (wage/salary income) observed.

As subordination in the South declined, work and housing subordination rose in the primary destination-regions of the Great Migration: the North and Midwest, which had been the most equal regions in 1940 but also possessed deeply segregated cities. Levels of work subordination declined across all US regions from 1940 to 1970 but, in the North and Midwest, this trend was substantially reversed from 1980 to 2010. In the case of housing, levels of subordination increased in the North and Midwest mostly from 1940 to 1970, as subordination declined in the South and West. Thus, region-specific trajectories go far toward explaining the nationalization of subordination patterns, 1940–2010. Larger declines in the South combined with moderate increases in the Midwest and North to produce a nation that is far more homogeneous in levels of subordination than it was in 1940.

Countervailing regional trends also contributed to the “consolidation” of exclusion across the states observed earlier (i.e., more moderate convergence around a more stable median). In all regions except the South, where we observe modest declines in white-black access to homeownership, levels of housing exclusion rose during this period. Similar dynamics emerged in the work domain, where an 8 percent increase in the South contrasted with a 7 percent decline in the West.

To what extent did these changes in cross-regional differences correspond to changes in racial composition and/or shifts in within-region differences? Figures 6 and 7 display black population sizes and subordination and exclusion levels by region, 1940–2010.

Figure 6 Racial subordination and racial composition by region, 1940–2010.

Figure 7 Racial exclusion and racial composition by region, 1940–2010.

Regional changes in racial composition were substantial over this period, driven especially by the Great Migration of blacks from the South to the North and Midwest. Yet our analysis suggests no simple relationship between regional changes in racial group compositions (i.e., population percentages) and regional changes in racial group positions (i.e., subordination and exclusion). Three patterns stand out. First, substantial declines in black population in the South, especially from 1940 to 1970, correspond with declines in southern inequalities across all four of our measures. The lone exception here is work exclusion, where inequality increased from 1940 to 1970. In the Midwest and North, we observe separate, domain-specific patterns. As the percentage of black residents rose, levels of housing subordination and exclusion between blacks and whites also increased. By contrast, growing black populations corresponded with declines in black-white subordination and exclusion in these two regions. The relationship between racial compositions and relative racial positions, we conclude, is far from straightforward. In these data, it varies considerably across region and socioeconomic domain.

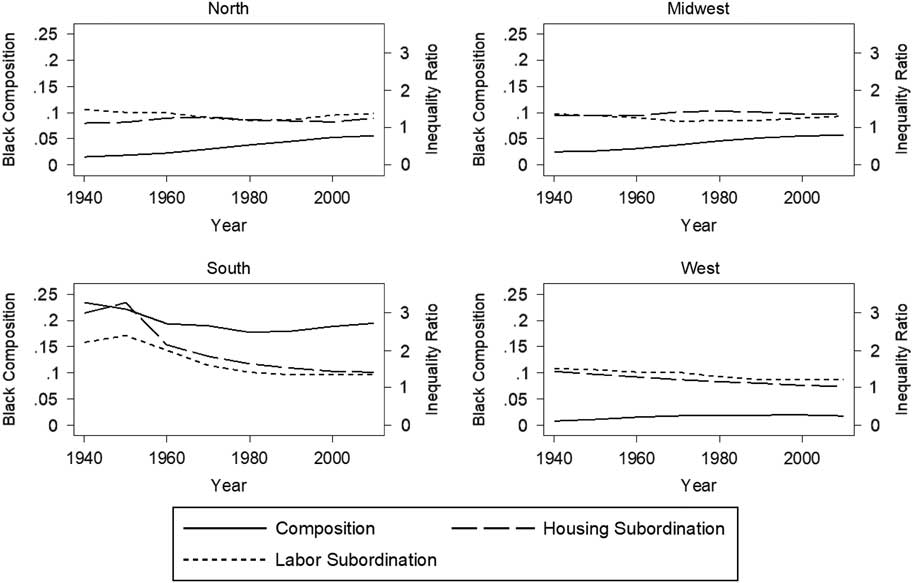

Turning finally to within-region differences, results presented in table 3 yield several insights into the nationalization of state-level racial relations, 1940–2010.

Table 3 Between and within region variance over time

Source: US Decennial Census.

Note:Values come from the application of ANOVA to regional groups.

First, consistent with our COV analysis, we find greater convergence for subordination than for exclusion: Across the two domains, declines in total within-region variance range from 92 to 97 percent for subordination and from 25 to 82 percent for exclusion.Footnote 9 Second, in both domains, we find that state-level convergence on the exclusion dimension was driven almost exclusively by trends toward uniformity within regions; cross-regional convergence plays a limited role. Third, this pattern does not hold for subordination, where between- and within-region trends both contribute and, in fact, between-region trends account for slightly more of the total decline (52 percent for work, 60 percent for housing). Fourth, additional analysis shows that across our two domains, within-region convergence on the exclusion dimension was greatest in the West, while convergence on subordination was greatest in the South.Footnote 10 Here, as in other parts of our analysis, we see dimensions of inequality (subordination and exclusion) moving together across domains (housing and work) more than we see domain-specific trends encompassing both dimensions of inequality.

In sum, regional analysis underscores the importance of subnational variation in US racial relations and bolsters the conclusion that subordination and exclusion operated empirically in this period as distinct dimensions of racial inequality. Across regions, we find different historical trajectories, with the greatest changes observed for subordination and for the South. Racial inequalities in the 50 states converged considerably from 1940 to 2010, producing a more uniform structure of racial relations across subnational units. Even in this story of convergence, however, our analysis counsels against a single story of national change. The consolidation of exclusion occurred mainly because states within regions came to look more alike. By contrast, the equalization of subordination was driven by a combination of declining differences both between and within regions.

How, then, should one specify the contributions of within- and between-region trends? We find that larger declines in total variance were strongly associated with larger declines in between-region differences (r=.90). Within-region differences declined across all four of our measures; the greatest amounts of state-level convergence are set apart by the addition of larger between-region declines.

Conclusion

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, racial inequality remains a painful feature of daily life in the United States. The aspirational march toward racial progress has been unsteady, as Philip Klinkner and Rogers Smith (1999) observe, not only because advances have been so halting and subject to reversal but also because they have been so uneven across the nation’s states and regions. In this article, we have shown how the empirical study of racial inequalities can be advanced by combining a relational focus on boundaries and positions with attention to state and regional variation. The resulting shift in perspective generates fresh insights into dynamics of equalization, consolidation, and convergence in the American racial order.

Focusing on work and housing, our results demonstrate the empirical value (in this case) of making an analytic distinction between subordination and exclusion. Inequalities within institutional arenas (subordination) are conceptually and empirically distinguishable from inequalities that are organized by institutional boundaries and regulated through social closure (exclusion). From 1940 to 2010, boundary-based racial exclusion proved to be far more durable than inequalities of subordination. These results offer a first step toward thinking more precisely about the mechanisms that regulate persistence and change in racial inequalities, highlighting the critical importance of institutional boundaries for efforts to achieve racial justice.

Against a backdrop of scholarship focused on aggregate national trends, we have also sought to reinvigorate attention to federalism as a key structural feature of racial inequality in the United States. The methodological shift to state-year observations offers substantial analytic advantages: The larger observational samples that result are more capable of distinguishing changes across time, space, and dimensions of inequality. Perhaps more important, however, the shift to subnational units affords a far greater ability to deepen the dialogue between quantitative trend studies and works of historical sociology that have long emphasized the importance of state-level governance and “group- and region-specific histories of citizenship” (Glenn Reference Glenn2002: 40).

From 1940 to 1970, state-level developments did less to reduce actual levels of black-white inequality than to promote national convergence around a shared structure of racial relations. The erosion of subnational differences was driven by a small number of distinctive regional developments that operated primarily through the shifting fortunes of blacks. Moreover, subnational differences in subordination declined more than differences in exclusion. Thus, even amid a significant nationalization of racial relations, we find a story that is fundamentally about how state and regional trajectories varied over the past 70 years. Now as in the past, racial inequality remains a national feature of the United States that is reproduced, transformed, and sustained through a variety of subnational dynamics. More than a mere distribution of possessions, racial inequality remains a fundamental structure of social transaction that positions racially defined groups in relation to institutional boundaries and one another.

Notes

We thank Geneva Cole for research assistance and gratefully acknowledge support from the Russell Sage Foundation, and the University of Minnesota’s Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program (5K12HD055887) and the Minnesota Population Center (5R24HD041023), both funded through grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2018.36