Anna Höstman: Hello and thank you for this interview. How did you begin composing?

Keiko Devaux: I have always considered myself a later composer. I started seriously composing at 28. I think a lot of other artists I have affinities with have gone this more circuitous route. I was going to be a piano performer and then I was in a rock band and we started a label and we decided to move across the country (to Montréal), play music, put out CDs and compose our own music. It was kind of nerdy math rock, prog post-rock stuff with live video.

I did that for quite a while and played in other indie/rock/various other bands. I enjoyed the recording studio process of being in a band and working on the sonic compositional product and so I became more and more interested in doing things like the string arrangements for us, and working for film and working with dancers, and I did music for a documentary. I wanted to improve my French, so I went back to university for very practical reasons. I went back to get a degree so I could teach at a Cégep and make enough money to compose moderately throughout the year. And then I just did what I do, which is reach out to people, collaborated and worked, and then I got steered more towards being a focused composer and less based on someone else's artwork… my own commissions, my own ideas. It wasn't really planned out that way. I just knew I wanted to be making art.

I'm into all sorts of facets of it. I'm interested in electroacoustic music and mixed music. I could be happy doing instrumental for a long time. I like sound installation. I know I have a sound and I have a way that I compose, but I'm very interested in the artistic profile of someone who can explore very different aesthetics and styles and approaches. I like artists who do that, who are chameleons and don't feel they have to develop a certain kind of super-consistent aesthetic. I think what's interesting about certain voices is that they can question themselves, and then they can do drastically different things. I like that kind of dynamic artistic profile.

AH: You are originally from British Columbia?

KD: I'm from BC. Born in Castlegar, but from Nelson. When I was in that rock band, we all went to the Selkirk College of Music technology programme. I was in piano performance doing jazz and all kinds of contemporary pop piano stuff. I was practising all the time, and I made friends with this guitar player and this drummer and we formed a trio, a band called People for Audio. We played post-rock, prog-rock, whatever you want to call it.

I got very overwhelmed with the idea of striving to be a performer. It doesn't really fit my personality. I feel like it's hyper-competitive, although being a composer is also hyper-competitive, but there's a way to approach composing where you can resist it more. And I know there's lots of camaraderie and community in the performance world, but I think when I was young and wanting to be a performer I got scared out of it because I'm not cut-throat. I mean, I like obsessing. I will obsess about practising something but in a more exploratory, creative way. I didn't understand this idea of trying to achieve finesse. It didn't appeal to me. I liked error and I liked improvising and I liked approximating things. I would constantly take scores that were much too difficult for me and look at the top line and look at the bottom line and look at the general texture, and then just make it up.

AH: This leads me to ask you about the idea of translation that you've written about with regards to your composing.

KD: Yes, it didn't consciously come from that, but I totally see the link now. When I first started composing on paper, I found myself writing lots of things with motors and drones, like rhythmic motors, because I was playing in rock bands, and I thought, oh, I sound like Steve Reich – I felt really trapped.

I wasn't calling it a translation at the time but the first thing I did was give myself an exercise to force me out of this habit. I could just tell myself put a silence, or make an irregular rhythm, or make something arrhythmic, but, when I recognise a pattern or a restraint or a crutch in my composition, I have a hard time just doing the opposite. I need to represent something. I don't want to just do anti-something; I want to do something.

The first thing I did was watch a bunch of film scenes with these conversations that were well edited. The tone of the voice and the pace of the conversation was really interesting. And it was a very clear exercise: I'm going to transcribe this scene; I'm going to transcribe the rhythm of their speech. I'm going to map out my subjective experience of their emotional expression, both explicit and implicit. I'm also going to include specific framing points, eye-contact and other non-verbal points of expression. I had this layered map. Conversation I Footnote 1 and Falling's just like Flying Footnote 2 are examples of works that followed this process quite closely. These are older pieces, in a very different style from what I do now, but were an important step in the process to get where I am now.

I then chose parallel musical representative parameters to match with these various layered elements of the film scene. For example, I would map the pitch to the vocal prosody, or the change in focus in aural framing to how characters were situated visually. It was an experiment in thinking about the organic matter of this experience of listening to this scene, the visual and auditive experience. Could I translate if I just matched them to other parameters? I did this for three conversations. I don't know if I loved what came out of them, but it shook up the way I wrote because it forced me to have these stronger gestures and contrasting juxtapositions of gestures and silences.

That was the first translation I did, and then I started doing things around the auto-organisation of birds and any kind of swarming material. I didn't make mathematically literal translations through software. It was more like I'd read a book about swarming of starlings and then I would make rules for pieces and I would make certain gestures that would be more representative, so there's a slight mimetic quality to it. But it was mostly about the behavioural patterns, sound representing physical movement. So that was the second stylistic approach to translation.Footnote 3

But these are all translations of extra-musical experiences. Eventually I became more involved with what I'm doing now, which is a mix of extra-musical and intra-musical interests, interacting with this idea of the memory of sound, including the memory of musical performance, holding on to melody, these more complex experiences we have associated not just with sound but also with pieces from the past. All my current works are focused on this theme of memory and experience, but in particular Tenebrae, Dust and Echoic Memories.Footnote 4

AH: Why has memory become important to you and how does it shape your current practice?

KD: My primary interest in considering the memory of sound, or of listening, lies in the sensorial experience and emotional affect linked to these memories. How do we remember sound? How do we hold on to and recognise complex sounds, patterns and styles, and how does that find its way into our compositional voice? I am interested in exploring how auditory memory can be a tool in the recreation of an experience. As a composer I have always actively listened to works in progress as a way to create this imagined sonic or narrative experience. More recently, engaging in pre-existing music allows me to experiment with my own aural experiences and sensations within my own voice. Connectivity, ghosts, excavation and the intangible, invisible and inaudible have all become very prevalent themes in the pieces I have composed over the last four years.

The first time I really began consciously thinking about memory was for my string quartet Tenebrae, for Ensemble Musica Assoluta in Germany. As the commission asked me to engage with my relationship with Mozart, I was reading and thinking about Mozart, not just his works, but his interests and life. I came across the famous story of how he visited the Sistine Chapel as a young boy, heard Allegri's Miserere Mei, Deus and immediately went back to where he was staying to transcribe it by memory. This story is often told to express the virtuosic ability of Mozart, but I find it more touching than anything. He became much more three-dimensional for me when I considered works that touched him. As I composed this piece that expresses this act of Mozart transcribing Allegri I became more and more interested in the blurred boundaries between composition, auditory memories, audiation and transcription.

In terms of how these new interests have shaped my practice, perception and human-centred engagement with tools has become important, finding this particular spot where I can explore the personal, but present it with more abstracted universal gestures, sounds and language. I have embraced the more vertical chaos and complexity of pieces, allowing different imagined sounds and layers to coexist without having to control their alignment visually on the score. This has wildly opened up new sounds and textures for me.

AH: Can you take me through an example of your process for creating a piece, from the spark of the idea forward?

KD: Ebb Footnote 5 is a really interesting piece because I would consider it a pivot piece, from me being interested in auto-organisation to also being interested in interacting with pre-existing musical material in a conscious way. I had written maybe three pieces about bird-flocking and it gave birth to a lot of new gestures in my music to do with the proliferating and fading out of things. We create new musical gestures and new sounds and layers based on a specific musical material, but it's not like they belong to that; now they become part of my voice.

I thought I'd be interested to explore a piece about auto-organisation but under water. And when I started reading about it, about shoaling, I realised it's quite similar to flocking; it's not going to sound very different. So I decided to be a little less literal about it. Also, the way sound actually travels under water is very different from how we humans experience it.

I read about the science of sound underwater, made a bunch of recordings, and listened to various sounds underwater. I wrote descriptive text to describe how I perceived it and what it felt like. For me, it's much more interesting to depict the experience rather than follow the strict facts. I didn't want it just to be about fish shoaling underwater; I wanted it to be about that feeling of how sound changes, how the experience of sound changes when we go underwater versus when we go into the air, and sort of lightness and heaviness. I wanted to have another parameter to distinguish between these two states that wasn't just harmony or tempo change or a concrete musical technique, but something a bit more subtle.

I decided to have two musical works that have made an impression on me (but in very different ways) associated with these two different sections. For the air section, I took Moon River, which has all these rising sixths and thirds and romantic and lifting melodies, and this kind of lightness to it, yearning to it. It's a piece I like and that I've always wanted to pay some kind of tribute to. And I was listening to lots of Georgian singing and I love that in a very different way. It's very static but super-vibrant, and very tense and then very rich and thick. For me, they were interesting examples of things that I would never juxtapose normally: one had a lot of harmonic predictability, and movement forward because of all the syntax that my ears understood, and one was just a bit more uncertain and static because of the fourths and the fifths and these microtonal interventions. And, again, it was an experiment.

I chose those two pieces and assigned them to their sections, came up with a form and the overall narrative: I'm going to start underwater, go into the air for a moment like an arm, and then back underwater, etc., and I would continue developing the piece like this, playing with the density and lightness of the two sonic environments.

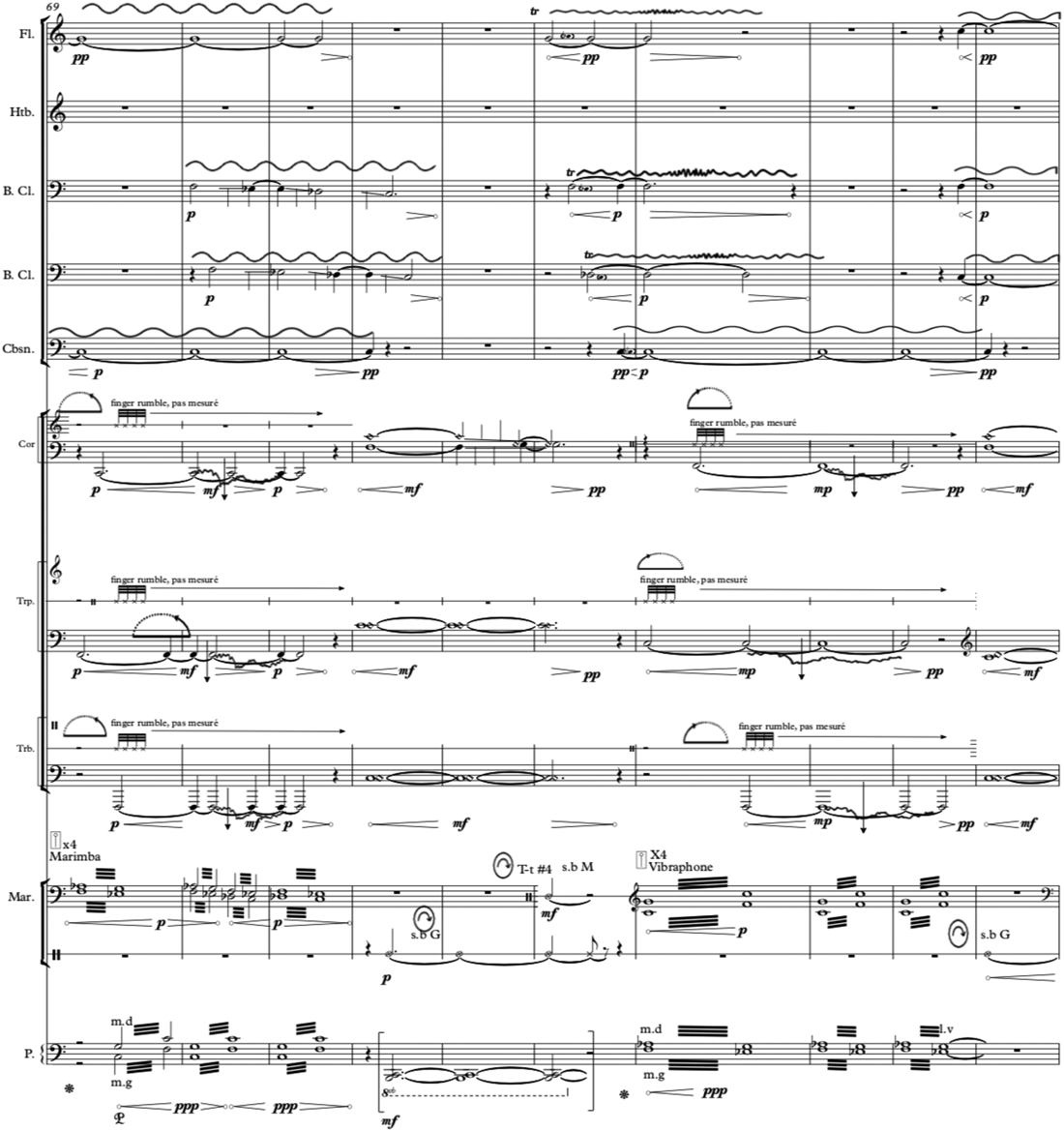

I map out what I think is an interesting experience in terms of what these two environments represent to me and the timing. This is going to be really short because it's going to move quickly and be free-falling, and that's going to be long. I decided about those things right at the beginning. I know that for five minutes I want it to be static and rich in terms of timbre, but not a lot of harmonic movement (see Example 1). And I want it to get thicker and thicker and thicker. Those things are clear to me. Even if I'm writing (I write on paper), I'll either do a maquette if I'm doing something complex, or I'll literally take underwater sounds from some kind of audio archive and I'll make a rough simulation. I'm listening to this kind of sound: how long is that interesting for? Does it get annoying? It's like creating these little musical therapy things. I map out the form and then I go to the scores and abstract… OK, what's interesting about the score? What makes it free falling?

Example 1: Keiko Devaux, Ebb, p. 8.

I take these parameters that I find, that give a certain sensation, that give a certain feeling but are not citations. I take those and transpose them into whatever I want, and I do the same thing for the other musical material, and so I have these pages that are just headless musical seeds and gestures with adjectives.

Then I decide on roles: the brass is going to represent the Georgian choir, the strings are going to represent the Mancini, but the winds are going to act as the go-between. What's everybody's roles? And then I do global mapping. And then I put the score on the wall or on the floor and take post-its, and then… first seed arrives here [sings string melody fragment]: OK, it's going to drown for about ten seconds and then it's going to come again but louder and there's going to be tension. And I'll put the next post-it. I just kind of audialise my way through the piece, conducting and singing vague things, even if it's just like [sings 3 seconds of loud white noise].

And then I write the score, left to right. I spend way too much time listening to audio recordings and putting them into AudioSculpt and analysing them. That's a nice underwater sound: can I get that on the gong? Or what are the timbres that give it that kind of foggy sound? OK, I want all the low sounds, so choosing the instruments that are going to make it work. And making a master list of what are all the gestures that are going to represent the blurriness and distortion of being underwater, and what are all the gestures that are going to represent this, and what are the hybrid transitional gestures. [Laughing] It sounds very dry and organised when I talk about it!

AH: No! It sounds very physical, kinaesthetic, even dramaturgical…

KD: I'm currently working on a piece that includes dramaturgy and it's natural for me to picture things – oh, I need low light. And can you project waves at this point? And I want us to be up there, and can we do this inside of a pool? Give me carte blanche and I will spend way too much time thinking about everything.

AH: Who are you influenced by as a composer?

KD: I'm influenced a lot by all my talented colleagues. Also, I went to Italy and studied with Sciarrino for three years and it was really significant – because he is one of my favourite composers, but I actually also felt a surprising connection with him, despite the language barrier. But I connected with his stuff before I met him. I went to see a series of his solo works here and it was at a time when I was feeling kind of jaded about contemporary music and the scene, and everything has to sound complex.

And I went to hear his works and, now, I'm sure you've seen his scores, so it's going to sound surprising, but I thought his stuff sounded so simple. Now, to be clear, I'm aware that they're far from simple. But if you close your eyes and you listen, I consider it simple. Simple is not the right word. I mean direct and honest, and generous. Like there's something very personable about his works considering who he is. And I was moved and really, really drawn in by these solo works. And then I went and looked up the scores the next day. I was quite taken aback – because I'd listened with my eyes closed – I was taken aback by how profoundly he finds a way of making something simple detailed, like he's taken a microscope to it.

When I met him and he looked at my stuff and finally started to understand what I was trying to do, he said something quite profound to me. He said, just because what you want to express is simple doesn't mean you have to do it in a simple manner. Just go deeper… and it was just like this: very, very direct… .

And it's funny, this advice has helped me so greatly, but I don't always agree with the sentiment. I think composers can present things simply, or in an open-ended way to create a more collaborative relationship with the performer. I think there's nothing wrong with collaborating with performers and leaving things open on purpose. I love improvisational stuff; I love open imagery; I love graphic scores. I don't necessarily practise them a lot, but I appreciate them, and I think they bring a whole different kind of beauty. But what it inspired me to do was… I didn't feel any pressure any more to change the sounds in my head that I wanted to express. If I want to listen to just a single held note for ten minutes… then maybe another note enters at one point, a little flutter, that's what I want to make. And it just made me realise that I need to search for different tools.

I know that my stuff doesn't look simple and I'm still working towards shedding excess stuff, but he's been a huge grounding anchor for me. He has a very modest but deep confidence, and I think for a long time I lacked confidence as a composer. Like he would make notes on my score or give me feedback, and I would go to erase and change things and he would say, no, no, no… just think about it. He had so much respect for what I had written, and I am just so touched by that.

I'm influenced by Ana [Sokolović] and Pierre [Michaud], who've been great mentors and are great composers. Saariaho is another composer I really admire; David Lang, and Jürg Frey, and, in general, sounds from the electroacoustic world. There's Italian artist Alessandro Bosetti that I love that does very different things than what I do – he works with speech a lot.

AH: In 2020, you were the inaugural winner of the $50,000 Azrieli Commission for Canadian Music, which is now the largest prize for contemporary music in Canada. That must have been so completely thrilling for you! What came about as a result of that prize?

KD: It was shocking. I wrote the piece Arras Footnote 6 that was premiered last October in Montréal. Everything has been kind of pushed forward because it's been so complicated to organise shows for obvious reasons. It's going to be played in New York this October (2021) by the Talea Ensemble, and by the Israel Contemporary Players in Tel Aviv in December. It was recorded by the Nouvel Ensemble Moderne a couple weeks ago for its release on Analekta. This is the Azrieli Music Prizes album that will have Arras as well as two works by the other AMP composers, Yotam Haber and Yitzhak Yedid, as well as a piece by Pierre Mercure.

I really did not expect to win. Two years ago I started applying to things and I had a hard time, a really hard time with the prompt.

AH: What was the prompt?

KD: The prompt was, because it's the inaugural prize of Canadian music, to write a proposal on ‘what is Canadian music?’ To talk about Canadian music you have to say what is Canada, which is, of course, a loaded question. The colonial history, the oppression… For me, to contribute to a canon of Canadian works means to create something that is not meant to represent Canadian music, but something personal and unique to me. This way, the works will be very diverse, contrasting and maybe even dissonant with each other. It's to realise that the voices are made up of individuals with very different stories and experiences.

My father immigrated from France, and my mother is Japanese-Canadian – this is who I am. And I was born and raised in a region that some people call Canada, and this is the sound I make. I was kind of curious to see how the jury would react. I think they realised when they put that call out that it's a hard question to answer… and that's part of the interest.

AH: Do you have any further thoughts on the ongoing process of coming to terms with Canada's history?

KD: The way I think about Canada has changed drastically, constantly. Growing up, like most settlers, I wasn't very critical because we weren't taught to be critical; we were sheltered from information. I grew up in a small region that was made up of Doukhobors, the Ktunaxa First Nation, Japanese-Canadians and other settlers of various diverse backgrounds. I grew up with a very subjective perspective of feeling ‘other’-ed myself. I feel differently about it now.

So I wasn't focused enough on my role as a settler. I was focused on me feeling not part of something, as opposed to potentially part of something unhealthy on a much larger scale. I wanted to move to Montréal because I felt isolated and sheltered from what was going on in the world. I'm really grateful for the life I had as a kid, and I lived in a beautiful region, but I remember having this feeling that there was a lot more going on in Canada that I wanted to discover.

I visited Montréal and I remember being on a metro or a bus and there being four languages spoken around me and just seeing all these different cultures and it was so fascinating. I was drawn to Montréal and I wanted to learn French and then I moved here, and what's interesting about Québec is people are quite politically engaged here. People are upfront, very political, and I appreciate that about Montréal.

I think I started to get curious when I was in my early twenties and I did music for my cousin's film called A Sorry State.Footnote 7 It's a very first-person, subjective film focused on the experience of growing up and attending these government apologies, this redress (the Japanese internment, Chinese head tax, the residency schools), and being basically, like, who is this for, these redress movements? – and all these various opinions and relationships with it, people who want to let it go, people who want to talk about it.

I did the music for this film and so I became quite interested and started reading and catching up on all my Japanese-Canadian history – the camps and all the separations of families – and talking to my family more and trying to understand it. Naturally, when you start to confront things that are directly in your family, you want to learn more about what happened before us. What happened in the region I grew up in with the Ktunaxa? You begin to realise how much you are not taught growing up.

My current narrative is… it's very broken. There's a big gap between how Canada likes to represent itself and the actions it actually takes, so it's important to stay engaged, informed and critical no matter what your opinion is.

AH: Do you explore your own personal history and family background in your music or have you an interest in doing this?

KD: Well, in Arras, the piece that I wrote for the Canadian prompt… I thought it's pretty significant that the Canadian commission could become a collection of works that could represent Canada in a very different way from how people have tried to do it in the past – and pretty significant that the first person who won is a woman and Japanese-Canadian. This is already something. I specifically wanted to make a piece that played with these musical histories, sonic histories, that wove together the Japanese-Canadian and French sonic histories. And I did grow up with Buddhism – and vinyls of these French singers. It's this very weird mix of sounds in my head, so I kind of leaned into it.

I also did a collaboration with [flautist] Mark McGregor because we're both Japanese-Canadian.

I'm a very small slice in a very beautifully complex and problematic pie of what is Canada. But there is a lot of positivity and people who live in Canada who can appreciate the land they live on, while working towards repairing damage and creating better politics moving forward. I feel grateful to live here and also have a complicated relationship with it, which makes talking about it very complex.

AH: You mentioned a piece you're working on with Mark McGregor (see Figure 1). Can you describe this?

KD: Mark commissioned a solo flute mixed piece from me. We worked on it during the pandemic and I was supposed to go (to Vancouver) and we were going to work together but that didn't end up happening. But we did record a video that will eventually be released for a public audience, and we will have a live show eventually. The piece is called Hōrai.

Figure 1: Hōrai, Mark McGregor (flute). Photo: Mike Southwork.

Mark and I are both Japanese-Canadian. We talked about different rituals we grew up with and we both had butsudans, which are these altars where you give offerings and you burn incense and have pictures of people in your family who have died. And it was a very normal thing to me. It's not like you'll go in there and chat with your past ancestors, but you're keeping them physically in your space and I like that. And you have your little bowl that you ring and there's a particular smell of incense.

So Mark and I have bonded about that and the piece ended up being about this idea of connecting and speaking with ancestors. I structured the piece around four significant people in my family who have passed, and then the form is run in the order in which they have passed, so my father, my stepfather, my grandmother and my grandfather, with a focus on my Japanese side.

I had pieces of music they liked, that they sang, representing them. And I worked the abstracted material of what represents them into the mixed material. Then Mark as a soloist represents this neutral state of something that exists, like the space that we are in now. And then we connect with this invisible other person who is there and is influenced by it. These melodies kind of seep into what [Mark's] doing, the timbre seeps in, the patterns seep in, and it leaves, and he continues, and his shape, his sounds kind of evolve, and he encounters the next spirit.

It's not meant to be this narrative, like I'm talking to a spirit, but it's kind of like he's a medium, moving through these old atmospheres. That's how I imagined it. Literally, in the score there's Phantom I, Phantom II. I want to give it this kind of ghostly element.

Hōrai is the name of this mountain. It comes originally from a Chinese fable history of a mountain called the Penglai. The Japanese have a version of it called Hōrai. It's basically this land where the oxygen in the air is different, the weight is different. It's like this other kind of world that you can seep into. So these interventions with the mixed material are meant to be more like an atmosphere, treating this idea of past people as atmospheres (see Figure 2).

AH: While working on Hōrai, you were posting on Instagram some very striking visual images that you were developing. What were these?

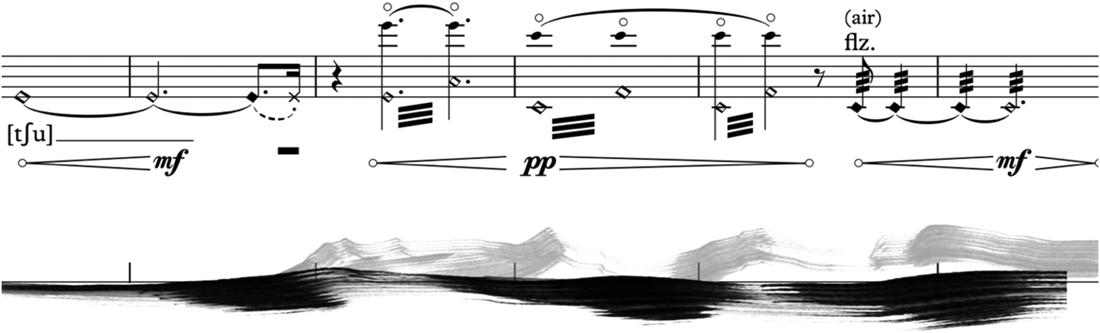

KD: It kind of evolved. We're going to record it and we'll have a video performance. I offered to send video material. I recorded a bunch of smoke machines, and I used my vaporiser and a fan. It was…[laughing]… such a simple idea in my head and ended up taking so much time, just to get these simple lighting gestures. I wanted it to be secondary behind [Mark], but I wanted to create something otherworldly, very intimate… I didn't want it to be this stark and formal concert experience. I also experimented for the first time with different kinds of score notation inspired by Japanese calligraphy (see Example 2).

AH: You are currently in residence with the National Arts Centre Orchestra (NACO) as a Carrefour composer, a wonderful project. What are you focusing on during your residency?

KD: This is the second year they've done it. The first year were [composers] Ian Cusson and Remy Siu. And this year it's me and Alison Yun-Fei Jiang. The idea was we'd spend seven weeks out of the year there, interacting with the musicians, maybe both of us at the same time, and do a chamber piece and an orchestra piece. I wrote the chamber piece last year, after I wrote the flute piece. It's called Bioluminescence. I‘ve always wanted to think more about bioluminescence and how to represent it musically, even if it's just on an impressionistic level. I find it beautiful and there's something hyperreal about it, so I approached it with a very strong interpretive brush stroke.

Figure 2: Keiko Devaux, Hōrai, video still.

Example 2: Hōrai, ‘Phantom 1’, p. 1.

I wanted to do a piece for just brass. I love working with homogenous instrumentations; I love doing things for just one section or just one instrument. Give me ten French horns! Give me ten piccolos! I love thinking about orchestration, but I love having that taken away from me and thinking about orchestration in a very different way. And organisation: especially when I'm working with flocking and swarming and pulsing and different kinds of patterns in nature, it's really natural to think about a limited resource. So it's a brass septet. It started as a sextet but it became a septet because the tuba player was too good not to include. Two trumpets, two trombones, two French horns and tuba.

Imagine underwater bioluminescence mixed with pulsing patterns of fireflies but very, very slowed down. It's quite challenging to play because it's 90% multiphonics. It's basically a study of multiphonics. I wanted to challenge myself and do something a bit more vulnerable, a little weird and limited.

AH: How has the experience of Covid-19 been for you?

KD: I feel grateful because I have a lot of work. I am in a great point in my career in the sense that I have a lot of opportunities But at the same time I would say that my career took this big pivot or upswing right before Covid – I received a commission from the OSM (Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal), the National Arts Centre Orchestra residency and the Azrieli commission and then… Covid. So my OSM piece was never performed. I wrote this huge piece, a 50-voice choir and ten-piece wind section, and it, of course, couldn't be performed [laughing].

I think what I appreciated about the OSM commission was it came out of nowhere. Orchestras do not commission very frequently and so it was such an honour. They just said OK, we're going to give you a piece and we're going to work with Dany Laferrière;Footnote 8 we'd like you to write something on one of his works on the theme of exile. It was this huge career turning point, and I wrote this piece which I'm very proud of. I'm looking forward to when it will eventually be performed.

So that was how Covid started with me. The other piece I wrote was for string orchestra and qanun. Then I did a piece for Trio Fibonacci, and then I was working on the OSM piece and then Covid happened and everything became a big question mark; tons of things got pushed. NACO's been virtual, and I find the level of organisational/administration work is just… tenfold.

AH: Do you mean keeping in touch with people?

KD: Keeping track of how schedules are constantly changing, and, because you're not meeting anyone personally any more, everything's in email, which some people like but I feel makes extra work. Just going out and seeing people and going to shows or having a coffee with friends after five days of working straight – we realise how important those little things are.

AH: How do you replenish yourself?

KD: I've got a garden. I like planting. We have a backyard here. I don't know what I would do without it. I have a couple friends that I'm quite in contact with who I have nice conversations with. I use video chat with my family. If I'm feeling exhausted after working on a piece, I honestly don't want to go to a show.

I'm a big one-on-one person, or I garden; that's really it. Before Covid, travelling for shows was a kind of forced vacation – packing and organising and going there, having a meet and greet with the musicians and going for a beer with them after the first rehearsal – those kinds of social things that get woven into the process that are just non-existent now. They were kind of our natural breaks and now they're not there. Like when I go to a recording session and they record, and then everyone sanitises their hands and goes home; [laughing] it's not quite the same thing.

AH: Do you have a dream project or ideal project that you haven't realised yet?

KD: There's a project I've been wanting to do for a while and I approached Architek [percussion] and they were interested and then my schedule just got chaotic and the planning of it has been postponed. I'll just say it is a project that embraces my love of the drumkit and auto-organisation patterns. I'm making a bigger effort to carve out time for these self-propelled projects, so hopefully it will happen in the future.

I have another piece I've always imagined doing. It's a very abstract idea: composing a piece or multiple pieces that are recorded and then put into the ears of conductors and the piece becomes about the imagined sound, the interior sound. I won't say too much more about it as it is very conceptual still at this stage. I want to keep an element of mystery to it.

AH: Keiko, thank you very much.