Sleep problems are commonly reported in psychotic spectrum disorder patients.Reference Reeve, Sheaves and Freeman1 Traditionally, sleep problems have been viewed as secondary to mental distress, with troubling thoughts, feelings and physiological hyperarousal seen as responsible for keeping people awake.Reference Kalmbach, Cuamatzi-Castelan, Tonnu, Tran, Anderson and Roth2 However, recent evidence suggests that sleep difficulties and psychotic symptoms are bidirectionally related.Reference Waite, Sheaves, Isham, Reeve and Freeman3 Freeman’s cognitive model identifies sleep problems as a causal factor in the development and maintenance of paranoia.Reference Freeman4,Reference Freeman, Garety, Kuipers, Fowler and Bebbington5 Lack of sleep can increase anomalous perceptual experiences, such as hearing voices or seeing figures (i.e. hallucinations), which may subsequently be misinterpreted in line with threatening delusional beliefs.Reference Reeve, Sheaves and Freeman6,Reference Waters, Chiu, Atkinson and Blom7 Sleep deprivation is linked to negative emotion, mood dysregulation and poorer reasoning, which may limit processing of alternative explanations and maintain a sense of threat.Reference Dudley, Taylor and Wickham8–Reference Westermann and Lincoln10 Nightmares are also hypothesised to maintain persecutory beliefs by interrupting sleep and triggering feelings of threat and negative affect upon waking. Moreover, nightmares typically depict paranoid fears (e.g. physical assault) in vivid detail which may be mistaken for reality, rather than a dream, and may directly reinforce patients’ worst fears.Reference Sheaves, Rek and Freeman11 Of note, it is not only psychotic symptoms that can be exacerbated by poor sleep. There are wide-ranging consequences for people’s daytime functioning, work, family and social relationships.Reference Batalla-Martín, Martorell-Poveda, Belzunegui-Eraso, Miralles Garijo, Del-Cuerpo Serratosa and Valdearcos Pérez12 Accordingly, poor sleep is linked to an overall reduced quality of life.Reference Ishak, Bagot, Thomas, Magakian, Bedwani and Larson13 It increases susceptibility to developing other mental disorders such as depression and anxiety, and has strong associations with suicidal ideation.Reference Li, Lam, Zhang, Yu, Chan and Chan14,Reference Neckelmann, Mykletun and Dahl15

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for sleep problems in psychosis

Sleep difficulties are increasingly identified as an important target for treatment. Patients with psychosis report desiring this support.Reference Waters, Chiu, Janca, Atkinson and Ree16,Reference Waite, Myers, Harvey, Espie, Startup and Sheaves17 Cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is the first-line recommended treatment for difficulties falling and staying asleep.18 Sleep is largely regulated by two processes, a homeostatic system (‘sleep pressure’) and a circadian timing system (circadian rhythms).Reference Borbély19 Sleep pressure rises with waking and falls during sleep and correlates with alertness. Circadian rhythms are directly influenced by environmental cues, especially light, by which they are entrained to a day–night cycle. CBT-I draws from this theory to modify dysfunctional behaviours and beliefs, with the premise that thoughts, feelings and behaviours are linked.Reference Walker, Muench, Perlis and Vargas20 For example, people with insomnia may believe they need to nap during the day to catch up on missed sleep. However, this makes it harder to fall asleep at night and leads to a vicious cycle. People may be encouraged to identify and challenge these unhelpful cognitions and reduce napping so that sleep pressure reaches a maximum at night-time. For nightmares, imagery rescripting treatment (IRT) is advised in best practice guidelines.Reference Aurora, Zak, Auerbach, Casey, Chowdhuri and Karippot21,Reference Casement and Swanson22 IRT is a CBT technique that uses imagery-based techniques to reimagine nightmares with alternative, less threatening endings.23

There is growing interest in whether CBT for sleep problems can alleviate psychotic symptoms and prevent clinically high-risk individuals from developing full-blown psychosis. Several trials have shown promising results.Reference Freeman, Waite, Startup, Myers, Lister and McInerney24–Reference Batalla-Martin, Martorell-Poveda, Belzunegui-Eraso, Marieges Gordo, Batlle Lleal and Pasqual Melendez37 Strict adherence to the CBT-I protocol involves elements of sleep restriction and setting a consistent sleep window, which is associated with side-effects such as sleep deprivation, fatigue and impaired vigilance.Reference Kyle, Miller, Rogers, Siriwardena, MacMahon and Espie38 There is evidence that sleep deprivation can be associated with psychotic symptoms in healthy controls.Reference Reeve, Emsley, Sheaves and Freeman39 Studies therefore describe making adaptations to facilitate engagement and mitigate risks of exacerbating patients’ symptoms in the context of psychosis.Reference Waite, Myers, Harvey, Espie, Startup and Sheaves17,Reference Freeman, Waite, Startup, Myers, Lister and McInerney24–Reference Waite, Černis, Kabir, Iredale, Johns and Maughan27,Reference Bradley, Freeman, Chadwick, Harvey, Mullins and Johns29,Reference Haynes, Parthasarathy, Kersh and Bootzin30,Reference Myers, Startup and Freeman32–Reference Taylor, Bradley and Cella35,Reference Batalla-Martin, Martorell-Poveda, Belzunegui-Eraso, Marieges Gordo, Batlle Lleal and Pasqual Melendez37

Review questions

This review seeks to address the following:

-

(a) What are the elements of CBT for sleep problems in people with or at high risk of psychosis-related disorders, and what adaptations are made to facilitate engagement and maximise effectiveness?

-

(b) What is the effectiveness in terms of sleep-related outcomes and psychotic symptoms (including delusions and hallucinations)?

-

(c) What are the effects on other clinical outcomes, such as depression, anxiety and quality of life?

-

(d) What is the acceptability of treatment?

Method

Search strategy and selection criteria

This review adhered to the updated version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. It was pre-registered on PROSPERO (ID CRD42023434097)Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman40,Reference Page, Moher, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow41 and was later updated to include the addition of qualitative studies. A systematic search was performed across Embase, Medline, PsycInfo and PubMed for articles published from inception to 12 December 2024. The search terms aimed to capture three main concepts: (a) sleep disorders (e.g. insomnia and nightmares), (b) CBT treatments and (c) psychosis (e.g. symptoms and diagnoses). Keyword searching of titles, abstracts and medical subject headings (MeSH) was undertaken following consultation with a librarian (see Supplementary Material for search terms, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.86). Several research groups were contacted to find out if they were intending to publish any new articles that would be relevant. The decision was made to include non-randomised studies because of the low numbers of randomised controlled trials investigating CBT for sleep problems in people with psychosis.

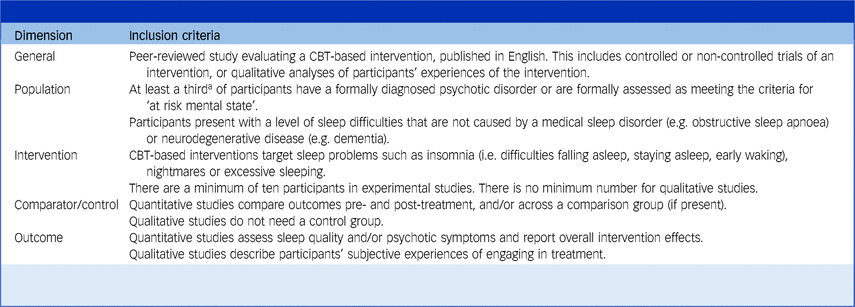

Screening was performed by two trainee clinical psychologists (H.W., first reviewer; R.B., second reviewer). Papers were excluded if they did not meet the criteria presented in Table 1. After searching across the databases, the studies were first screened using their titles and abstracts. The second reviewer screened 20% of these. Cohen’s kappaReference Cohen42 showed an almost perfect level of agreement (k = 0.85), and disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Table 1 Summary of inclusion criteria

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy.

a The criteria of a third of participants with psychotic disorder or at-risk mental state were chosen because of the lack of research in this area and seeking to be as inclusive as possible of papers that had the potential to be clinically relevant.

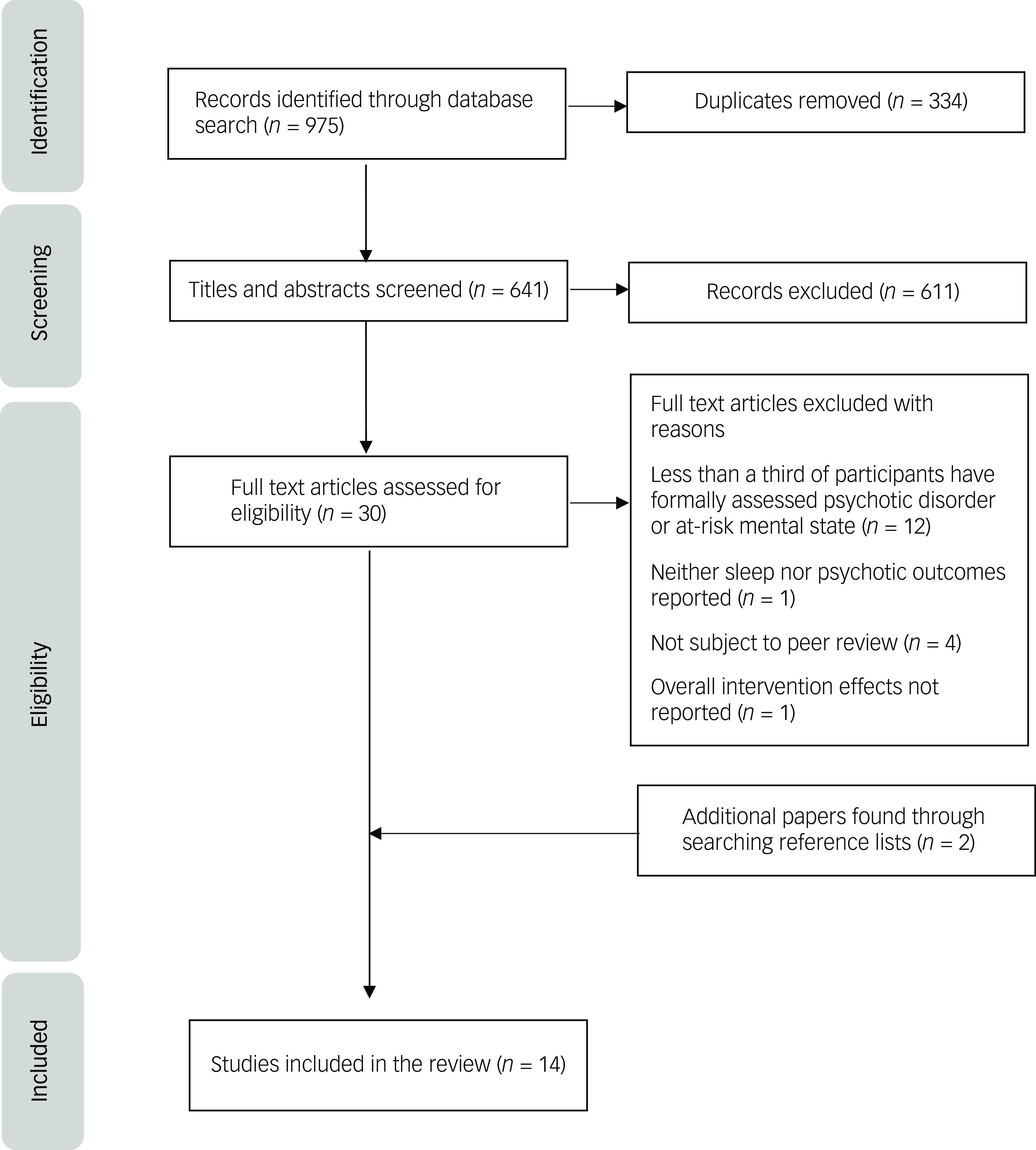

At the next stage, the first reviewer screened eligible papers at the full-text level and the second researcher screened 25% of these. There was a perfect level of agreement (k = 1). Reference lists of included papers were searched to identify any further relevant studies. The study selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 PRISMA flowchart of the study selection process. The reason given for the exclusion of studies reflects the first criterion for exclusion that the author identified. It is possible that some studies met several criteria for exclusion.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were systematically extracted by the first reviewer starting on 30 October 2023. The second reviewer independently extracted 50% of the data to ensure accuracy and reliability. Information was gathered regarding publication date, study design, treatment focus, protocol adaptations, geographical location, participant demographics, drop out, adverse events, means and standard deviations of clinical outcomes and questionnaire outcomes pertaining to treatment acceptability or satisfaction. Supplementary materials were checked for additional clinical outcomes that were not reported in the main papers. For trials comparing clinical outcomes across a treatment and control group, Cohen’s d standardised between-group effect sizes were calculated.Reference Cohen43 For uncontrolled trials, only the direction of the effect was reported since precise estimates were unlikely to be reliable because of the lack of a control group.

Previous research has defined and assessed ‘acceptability’ using a variety of different means. Sekhon et al’sReference Sekhon, Cartwright and Francis44 systematic review devises a theoretical framework of intervention acceptability comprising seven components: affective attitude, burden, perceived effectiveness, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs and self-efficacy. This review attempted to capture acceptability using a multifaceted approach. Themes and quotes that related to these constructs were extracted from qualitative studies by the first author (H.W.). Since there were only two studies, no formal analytic procedure was used; instead, common ideas and quotes were organised into themes, and two supervisors (A.L.-Z. and L.C.J.) were consulted to check their credibility. Drop-out was defined in this review as the number of participants who discontinued after having attended at least one session, during the intervention period.Reference Lewis, Roberts, Gibson and Bisson45 A narrative synthesis was used to interpret these findings together with data from drop-out rates, adverse events and relevant questionnaires.

Quality appraisal

The Revised Cochrane ‘Risk of Bias’ (RoB)Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe and Boutron46 tool was used to assess all randomised controlled trials (RCTs). The Cochrane ‘Risk of Bias In Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions’ (ROBINS-I)Reference Sterne, Hernán, Reeves, Savović, Berkman and Viswanathan47 tool was used to assess risk of bias in the remaining non-randomised controlled trials (non-RCTs). These tools yield a risk of bias judgement across several domains (e.g. selection of participants) and for the overall paper. To appraise the quality of qualitative studies, a checklist was developed from Braun and Clarke’s guidelines for reviewers to assess the rigour of thematic analysis.Reference Braun and Clarke48

The second researcher independently appraised 30% of papers after calibrating their ratings with one of each kind of paper (RCT, non-RCT and qualitative). In previous research, both Cochrane tools have demonstrated slight interrater agreement for the overall final judgement of risk of bias and poor-to-moderate agreement for single domains.Reference Couto, Pike, Torkilseng and Klemp49–Reference Minozzi, Cinquini, Gianola, Gonzalez-Lorenzo and Banzi51 The current review found perfect agreement (k = 1) both overall and at the level of single domains for the RoB. Agreement was perfect (k = 1) overall and fair (k = 0.60) at the level of single domains for the ROBINS-I. Agreement was moderate (k = 0.76) on the qualitative quality checklist. Differences between the reviewers were resolved through discussion.

The ‘Measurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews 2’ (AMSTAR)Reference Shea, Reeves, Wells, Thuku, Hamel and Moran52 was used to evaluate the quality of the overall review (see Supplementary Material).

Results

Fourteen studies were identified as eligible for inclusion. The results are organised by (a) study characteristics, (b) quality appraisal, (c) treatment effectiveness and (d) treatment acceptability.

Study design, participant and intervention characteristics

Study design and participants

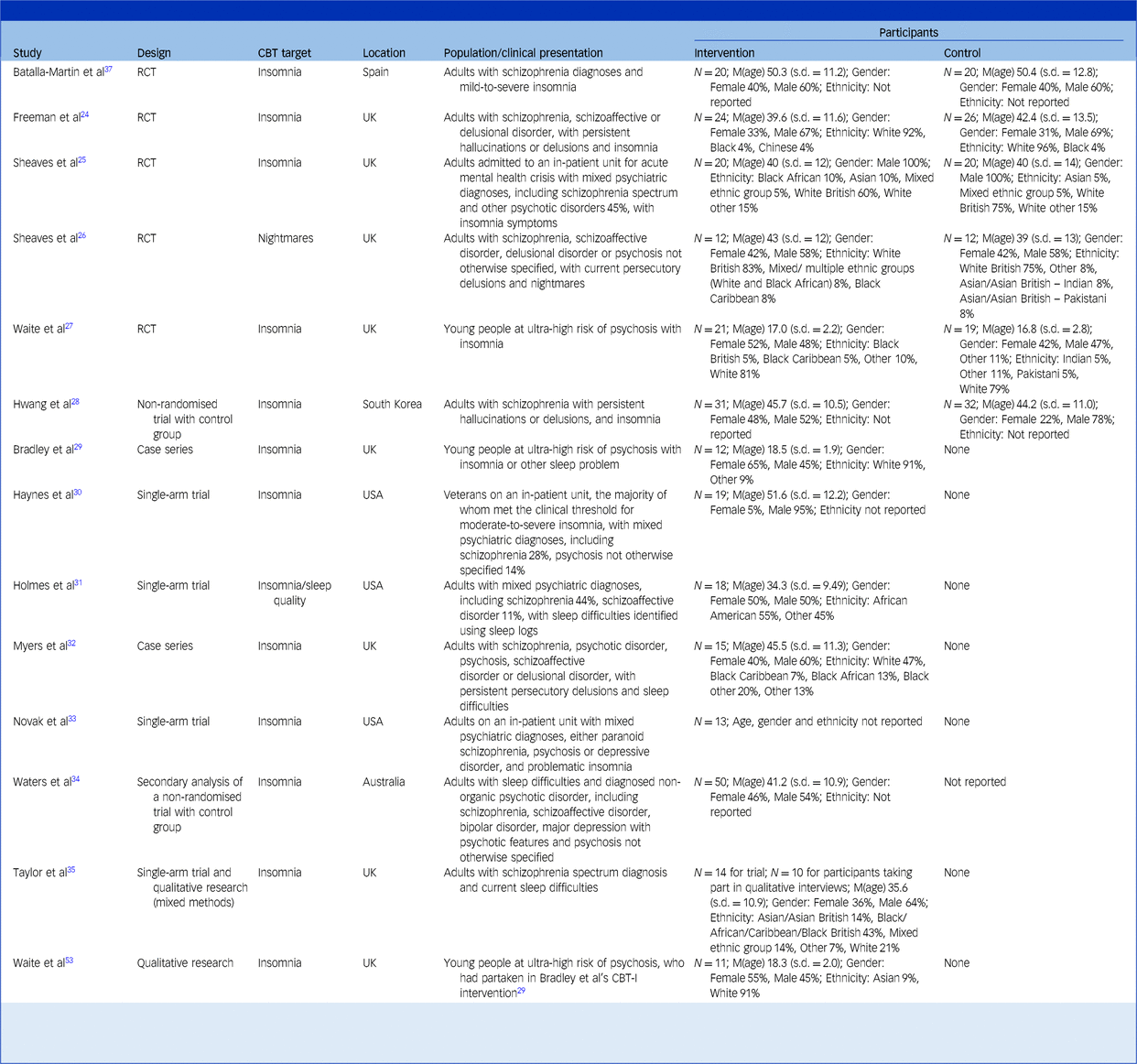

The study and participant characteristics are shown in Table 2. The majority (57.1%) of studies were conducted in the UK with the remainder being conducted in the USA, Spain, South Korea and Australia. There were five RCTs, seven non-RCTs and a mixed-methods study combining a non-RCT and qualitative design. There was also a qualitative paper that used thematic analysis to understand participants’ experiences of treatment in one of the non-RCTs.Reference Bradley, Freeman, Chadwick, Harvey, Mullins and Johns29,Reference Waite, Bradley, Chadwick, Reeve, Bird and Freeman53

Table 2 Study design and participants

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; RCT, randomised controlled trial; CBT-I, cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia.

This table presents all studies that are included in the review, both qualitative and quantitative. Studies are ordered by type (RCTs, non-randomised trials with a control group, single-arm trials, mixed methods, qualitative).

N, number of participants; M(age), mean age of participants; where possible data is reported to one decimal place.

All papers reported meeting the inclusion criteria of a third of participants having a psychotic disorder or at-risk mental state. The only exception was Novak et alReference Novak, Packer, Paterson, Roshi, Locke and Keown33 where it was confirmed in an email from one of the authors that 66% of participants had a diagnosed psychotic disorder (S. Watson, personal communication, January 2025).

The total number of participants was 398 across trials (RCT and non-RCT studies) and 21 across qualitative studies. The average age of participants ranged from 18.5 to 51.6 years. Participants were mostly adults with a diagnosed psychotic disorder; however, three studies recruited young people aged 14–25 years who were at risk of developing psychosis.Reference Waite, Černis, Kabir, Iredale, Johns and Maughan27,Reference Bradley, Freeman, Chadwick, Harvey, Mullins and Johns29,Reference Waite, Bradley, Chadwick, Reeve, Bird and Freeman53 All participants received CBT-I, except in one study where nightmares were the focus of treatment.Reference Sheaves, Holmes, Rek, Taylor, Nickless and Waite26 All studies had a relatively even split between males and females, excepting one with only male participantsReference Sheaves, Isham, Bradley, Espie, Barrera and Waite25 and another study of USA veteransReference Haynes, Parthasarathy, Kersh and Bootzin30 in which most of the participants were also male.

It was challenging to summarise ethnicity and race because of a lack of consistency in the categories used. Where this information was reported, studies indicated that the highest proportion of participants identified as White, except for one study where participants predominantly identified as African AmericanReference Holmes, Corrigan, Knight and Flaxman31; 35.7% of studies did not report ethnicity or race.

Elements of CBT and adaptations

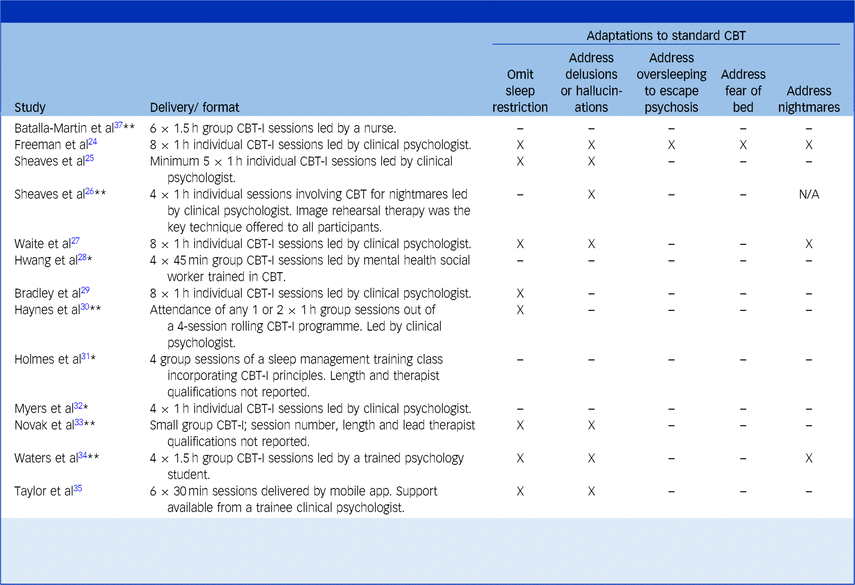

Table 3 gives an overview of the interventions. Standard components of CBT-I protocols include psychoeducation, stimulus control, sleep hygiene (e.g. avoiding screen use before bed), relaxation, worry-management and techniques that address circadian rhythm disruption, such as sleep/wake cycle realignment and daily activity.Reference Walker, Muench, Perlis and Vargas20,Reference Edinger, Carney, Edinger and Carney54 The studies that used CBT-I either explicitly described these elements, or reported following specific protocols that were known to feature them. Boosting daily activity was described as a key feature of several protocols because many psychotic patients have sedentary lifestyles. One study described greater scaffolding, for example, by first educating patients about the efficacy of CBT-I to enhance their motivation to engage, and by linking in with community resources to increase opportunities for structured activity and social connection.Reference Batalla-Martin, Martorell-Poveda, Belzunegui-Eraso, Marieges Gordo, Batlle Lleal and Pasqual Melendez37 Interventions in young people made further adjustments for the social, biological and environmental differences between adolescents and adults (e.g. involving parents, if appropriate).Reference Waite, Černis, Kabir, Iredale, Johns and Maughan27,Reference Bradley, Freeman, Chadwick, Harvey, Mullins and Johns29 Only one study investigated IRT for nightmares.Reference Sheaves, Holmes, Rek, Taylor, Nickless and Waite26 They also incorporated strategies for limiting worry, sleep window stabilisation, relaxation and grounding.

Table 3 Elements of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and adaptations

CBT-I, cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy.

‘X’ indicates that this adaptation was made to treatment. Papers have been marked by a single asterisk (*) where an attempt was made to contact their authors to clarify further details about adaptations, but contact was not achieved. Papers have been marked by a double asterisk (**) where the authors responded to enquiries.

Waite et al’s paperReference Waite, Bradley, Chadwick, Reeve, Bird and Freeman53 is not included here since it is a qualitative analysis of participants in Bradley et al’s trial,Reference Bradley, Freeman, Chadwick, Harvey, Mullins and Johns29 and thus reports the same intervention.

Studies are presented in order of type (randomised controlled trials, non-randomised trials with a control group, single-arm trials, mixed methods, qualitative).

Interventions were delivered in a variety of settings, formats and timeframes. Most interventions took place within a community mental health setting, although three took place on a psychiatric ward.Reference Sheaves, Isham, Bradley, Espie, Barrera and Waite25,Reference Haynes, Parthasarathy, Kersh and Bootzin30,Reference Novak, Packer, Paterson, Roshi, Locke and Keown33 The majority were delivered by clinical psychologists (53.8%) and as one-to-one sessions (53.8%). The number of intended sessions ranged from four to eight and typically occurred on a weekly basis. One study differed by providing sessions more intensively within a 2-week period to ensure participants received the specified dose before being discharged from acute in-patient admission.Reference Sheaves, Isham, Bradley, Espie, Barrera and Waite25 Of note, one study reported outcomes after participants received only one or two sessions of a four-session programme because they were limited by the duration of participants’ in-patient admission.Reference Haynes, Parthasarathy, Kersh and Bootzin30

The most common adaptation was omitting formal sleep restriction from CBT-I protocols (66.7% of CBT-I studies). Other adaptations included addressing problems of delusions and hallucinations interfering with sleep, oversleeping to escape from psychotic experiences such as voices and fears of going to bed caused by past adverse experiences.

Quality appraisal

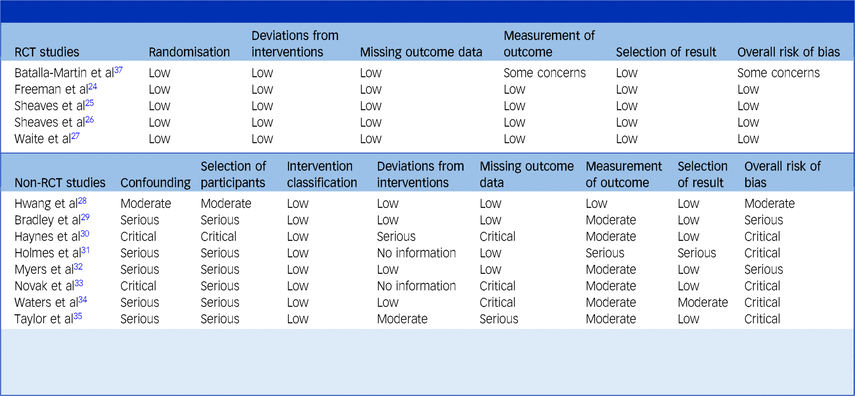

Table 4 shows risk of bias ratings for RCT and non-RCT studies. Four RCTs were rated as low risk across all the Cochrane domains because of rigorous procedures in their design and analysis.Reference Freeman, Waite, Startup, Myers, Lister and McInerney24–Reference Waite, Černis, Kabir, Iredale, Johns and Maughan27 Strengths included that they were pre-registered and used blinded assessors. One RCT was evaluated as having ‘some concerns’ because assessment was not blinded.Reference Batalla-Martin, Martorell-Poveda, Belzunegui-Eraso, Marieges Gordo, Batlle Lleal and Pasqual Melendez37 The non-RCTs fell almost entirely into ‘serious’ and ‘critical’ categories. Their greatest area of weakness was the potential for confounding. All studies but two lacked a control group,Reference Hwang, Nam and Lee28,Reference Waters, Chiu, Dragovic and Ree34 and of these two, only one attempted to deal with confounding by controlling for differences in baseline characteristics between the treatment and control group.Reference Hwang, Nam and Lee28 This study was also the only non-RCT to be use a blinded assessor and hence to be rated as ‘low’ on the domain of outcome measurement.Reference Hwang, Nam and Lee28

Table 4 Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) appraisal of randomised and non-randomised trials

Studies are grouped by whether they are randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or non-randomised trials (non-RCTs). Non-RCTs are further ordered by type (controlled, single arm, mixed methods).

The Cochrane ‘Risk of Bias‘ (RoB) tool was used to assess RCTs and the Cochrane ‘Risk of Bias In Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions‘ (ROBINS-I) tool was used to assess non-RCTs. Both tools rate studies based on their risk of bias across specific domains and overall. The RoB rates each study using three categories: low, some concerns or high risk of bias. The ROBINS-I tool rates the risk of bias for each study using five categories: low, moderate, serious, critical or no information.

Another area of weakness in the non-RCTs was the selection of participants. Without random assignment to a control, bias was likely introduced by participants self-selecting into the study or being selected by clinicians. Risk of bias caused by missing data was highly variable across the non-RCTs; while several studies reported zero drop-out, two studies had critically high levels of drop-out, presumably reflecting the lack of control in the acute in-patient setting regarding patients’ prognosis and discharge.Reference Haynes, Parthasarathy, Kersh and Bootzin30,Reference Novak, Packer, Paterson, Roshi, Locke and Keown33 These two studies also suffered greater potential for confounding where it was likely that patients were receiving psychiatric stabilisation and medication changes alongside CBT-I.Reference Haynes, Parthasarathy, Kersh and Bootzin30,Reference Novak, Packer, Paterson, Roshi, Locke and Keown33

Checklist ratings for the two qualitative thematic analysesReference Taylor, Bradley and Cella35,Reference Waite, Bradley, Chadwick, Reeve, Bird and Freeman53 are found in the Supplementary Material. A strength they shared was that themes were well evidenced and gave rise to actionable outcomes – they highlighted participants’ experiences of CBT-I, which led to practical implications for how treatment could be improved. However, neither paper specified what kind of thematic analysis was used or explained their theoretical orientation. The authors also did not ‘own their perspectives’ regarding their social and personal positioning, which was arguably important where they were representing the voices of a marginalised group to which they may not have belonged.

Treatment effectivenessFootnote a

Sleep problems

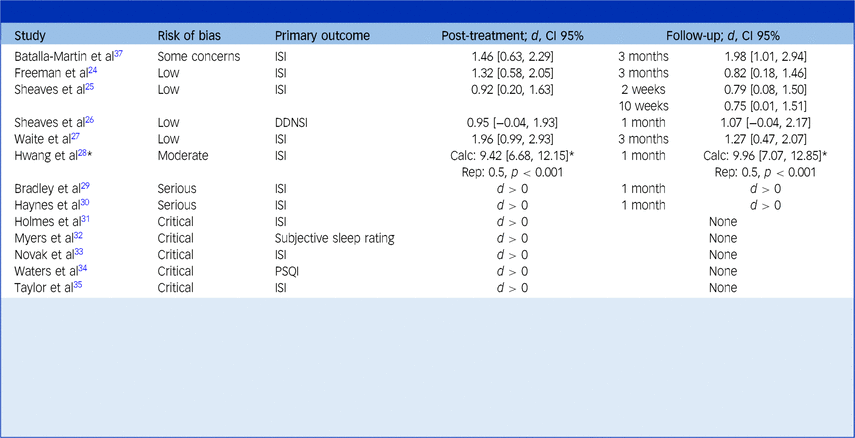

Table 5 shows the effectiveness of targeting sleep problems using the primary sleep measure, with studies organised by their risk of bias category rating. The sign of effect sizes has been changed such that a positive effect (d > 0) indicates an improvement in symptoms over the course of treatment. If the study includes a control group, a positive effect size indicates a relative improvement in symptoms in the treatment group compared to the control.

Table 5 Effect of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) on sleep problems

This table reports the effect of CBT in alleviating sleep problems as assessed by the primary sleep measure. Studies are organised by their risk of bias category, from low to increasingly severe.

Cohen’s d between-group effect sizes are shown for controlled studies, whereas the direction of the effect (pre-treatment versus post-treatment) is simply shown for uncontrolled studies. Results have been transformed such that an improvement in sleep problems in the treatment group (relative to the control group, if present) over the course of treatment is represented by a positive change score (i.e. d > 0). A deterioration in sleep problems in the treatment group (relative to a control group, if present) is represented by a negative score (i.e. d < 0).

The text in brackets refers to the 95% confidence interval of the effect size.

For Hwang et al’s study,Reference Hwang, Nam and Lee28 ‘Calc’ refers to the Cohen’s d effect size calculated from their reported means and standard deviations, whereas ‘Rep’ refers to the Cohen’s d effect size reported in their paper. The asterisk (*) indicates the need to treat their findings with caution given the large discrepancy between these estimates.

Primary measures include the following: ISI, Insomnia Severity Index,Reference Bastien, Vallières and Morin55 DDNSI, Disturbing Dream and Nightmare Severity IndexReference Krakow56 and PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.Reference Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman and Kupfer57 Holmes et alReference Holmes, Corrigan, Knight and Flaxman31 report a subjective sleep rating that is extracted from a sleep log published elsewhereReference Hauri and Linde58 but provide minimal further details. Where studies did not specify a single primary sleep measure, the most relevant measure to evaluate the intervention (e.g. an insomnia measure for a study of cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia) is reported.

Most studies (76.9%) chose the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)Reference Bastien, Vallières and Morin55 as their primary measure, whereas other studies chose to measure sleep quality or nightmares. Every study demonstrated positive effects, suggesting improvement in sleep problems following treatment. Effect sizes were calculated for studies with a control group, and ranged from medium to very large immediately post-intervention (d = 0.50–1.96). These calculated effects were all significant (i.e. confidence intervals did not overlap zero), except for one studyReference Sheaves, Holmes, Rek, Taylor, Nickless and Waite26 where the lower boundary of the wide confidence interval was marginally negative. This was the smallest RCT (only 12 participants in each group) and was likely underpowered. It was also the only study to investigate IRT, as opposed to CBT-I, and its primary outcome was the Disturbing Dreams and Nightmares Severity Index (DDNSI)Reference Krakow56 (a measure of nightmare frequency and severity), which may not be directly comparable to the other studies whose primary outcomes were sleep quality and insomnia. Over follow-up periods, effect sizes were broadly maintained (d = 0.50–1.98), with the longest follow-up taking place at 3 months.

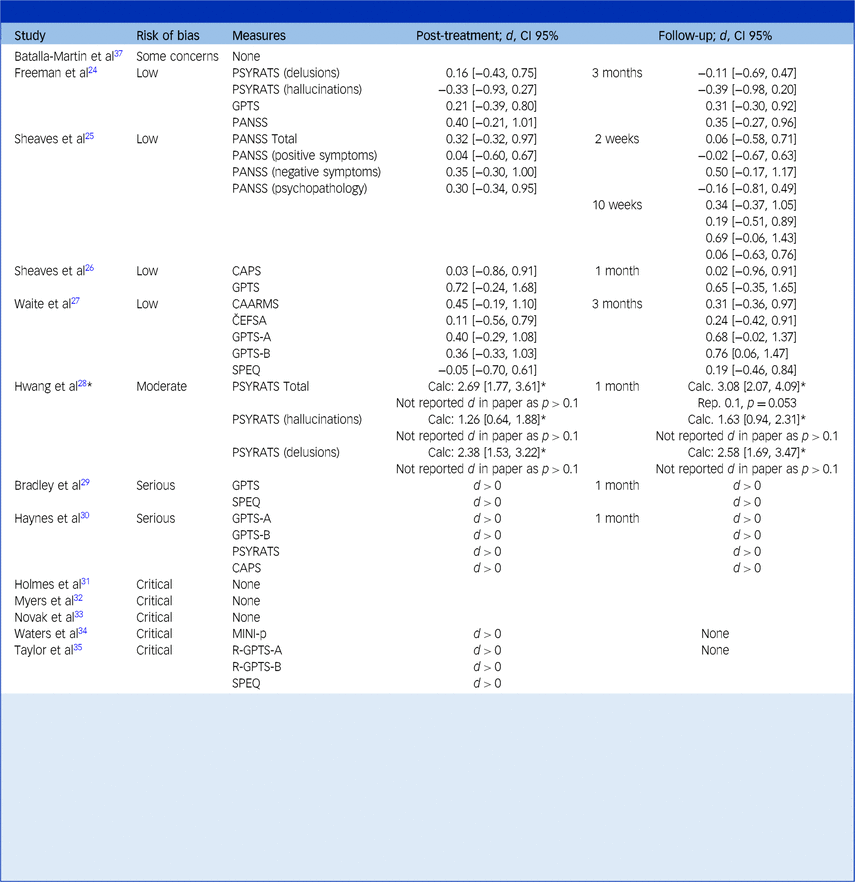

Psychotic symptoms

The impact of CBT-I on psychosis is presented in Table 6. Psychosis was assessed in nine trials using a variety of measures relating to delusions, hallucinations and other symptoms. The effects were almost entirely positive, in the direction suggesting a relative improvement of symptoms. Indeed, most studies reported solely positive results (66.7%); however, three of the studies found a mixed direction of effects across multiple measures or time-points.Reference Freeman, Waite, Startup, Myers, Lister and McInerney24,Reference Sheaves, Isham, Bradley, Espie, Barrera and Waite25,Reference Waite, Černis, Kabir, Iredale, Johns and Maughan27

Table 6 Effect of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) on psychotic symptoms

This table reports the effect of CBT in alleviating symptoms of psychosis. Studies are organised by their risk of bias category, from low to increasingly severe.

Cohen’s d between-group effect sizes are shown for controlled studies, whereas the direction of the effect (pre-treatment versus post-treatment) is simply shown for uncontrolled studies. Results have been transformed such that an improvement in psychotic symptoms in the treatment group (relative to the control group, if present) over the course of treatment is represented by a positive change score (i.e. d > 0). A deterioration in psychotic symptoms in the treatment group (relative to a control group, if present) is represented by a negative score (i.e. d < 0).

The text in brackets refers to the 95% confidence interval of the effect size.

For Hwang et al’s study,Reference Hwang, Nam and Lee28 ‘Calc. d’ refers to the Cohen’s d effect size calculated from their reported means and standard deviations, whereas ‘Rep. d’ refers to the Cohen’s d effect size reported in their paper. The asterisk (*) indicates the need to treat their findings with caution given the large discrepancy between these estimates.

All reported assessment measures of psychosis in each paper are presented. Brackets denote subscales in the measures column of the table; for example, ‘PSYRATS (delusions)’ refers to the delusions subscale of the PSYRATS.

Psychotic measures include the following: Cardiff Anomalous Perceptions Scale (CAPS)Reference Bell, Halligan and Ellis59; Černis Felt Sense of Anomaly (ČEFSA)Reference Černis, Beierl, Molodynski, Ehlers and Freeman60; Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMs)Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Phillips, Kelly and Dell’Olio61; Green Paranoid Thoughts Scale (GPTS),Reference Green, Freeman, Kuipers, Bebbington, Fowler and Dunn62 which contains subscales of ‘Ideas of Reference’ (GPTS-A) and ‘Ideas of Persecution’ (GPTS-B); Adapted Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview – Psychosis section (MINI-p)Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller63; Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS),Reference Kay64 which contains subscales relating to positive symptoms, negative symptoms and general psychopathology; Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale (PSYRATS),Reference Haddock, McCarron, Tarrier and Faragher65 which contains subscales relating to delusions and hallucinations, Revised-Green Paranoid Thoughts Scale (R-GPTS),Reference Freeman, Loe, Kingdon, Startup, Molodynski and Rosebrock66 which contains subscales of GPTS-A and GPTS-B; Specific Psychotic Experiences Questionnaire (SPEQ).Reference Ronald, Sieradzka, Cardno, Haworth, McGuire and Freeman67

Calculated effect sizes ranged between d = −0.39 and d = 0.79 across post-intervention and between d = −0.39 and d = 0.79 across follow-up and confidence intervals were generally very wide, which suggests high levels of uncertainty around these estimates. These effects were almost entirely non-significant since confidence intervals overlapped zero.

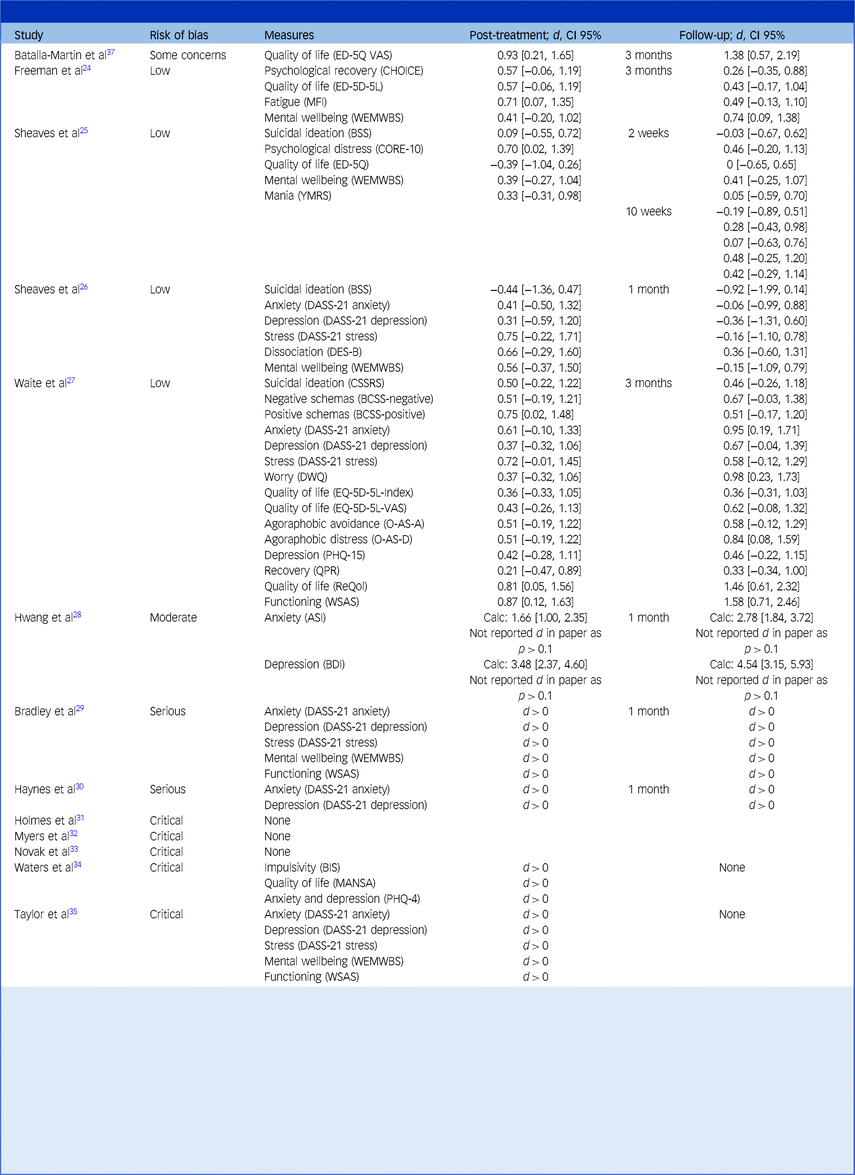

Other clinical outcomes

Ten trials evaluated whether CBT-I led to clinical improvements beyond sleep and psychosis. The most commonly assessed domains were anxiety, depression, quality of life and well-being. Table 7 displays effect sizes where a positive sign denotes a relative improvement in outcomes following treatment. Most effect sizes were positive, suggesting that participants’ outcomes improved. Nevertheless, these effects were largely non-significant. Confidence intervals were very wide and overlapped zero, suggesting that estimates were quite uncertain.

Table 7 Effect of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) on other clinical outcomes

This table reports the effect of CBT in alleviating other clinical symptoms. Studies are organised by their risk of bias category, from low to increasingly severe.

Cohen’s d between-group effect sizes are shown for controlled studies, whereas the direction of the effect (pre-treatment versus post-treatment) is simply shown for uncontrolled studies. Results have been transformed such that an improvement in clinical symptoms in the treatment group (relative to the control group, if present) over the course of treatment is represented by a positive change score (i.e. d > 0). A deterioration in clinical symptoms in the treatment group (relative to a control group, if present) is represented by a negative score (i.e. d < 0).

The text in brackets refers to the 95% confidence interval of the effect size.

For Hwang et al’s study,Reference Hwang, Nam and Lee28 ‘Calc. d’ refers to the Cohen’s d effect size calculated from their reported means and standard deviations, whereas ‘Rep. d’ refers to the Cohen’s d effect size reported in their paper. The asterisk (*) indicates the need to treat their findings with caution given the large discrepancy between these estimates.

The Measures column states the clinical symptom that was assessed, followed by the assessment measure in brackets. Assessment measures include the following: Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI)Reference Reiss, Peterson, Gursky and McNally68; Barratt Impulsiveness Scale - Brief (BIS)Reference Steinberg, Sharp, Stanford and Tharp69; Brief Core Schema Scale (BCSS)Reference Fowler, Freeman, Smith, Kuipers, Bebbington and Bashforth70; Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)Reference Beck, Steer and Brown71; Beck Suicide Scale (BSS)Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman72; CHoice of Outcome In CBT for psychoses (CHOICE)Reference Greenwood, Sweeney, Williams, Garety, Kuipers and Scott73; Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation 10-item scale (CORE-10)Reference Connell and Barkham74; Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (CSSRS)Reference Posner, Brown, Stanley, Brent, Yershova and Oquendo75; Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale–21-item (DASS-21)Reference Lovibond and Lovibond76 version with subscales for anxiety (DASS-21 anxiety), depression (DASS-21 depression) and stress (DASS-21 stress); Brief Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-B)Reference Dalenberg and Carlson77; Dunn Worry Questionnaire (DWQ)Reference Freeman, Bird, Loe, Kingdon, Startup and Clark78; Euroqol 5D questionnaire (ED-5Q)Reference Brooks, Rabin and de Charro79; Euroqol 5D questionnaire visual analogue scale (ED-5Q VAS)Reference Brooks, Rabin and de Charro79; Euroqol 5D questionnaire 5 Level version (ED-5D-5L)Reference Herdman, Gudex, Lloyd, Janssen, Kind and Parkin80; Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA)Reference Priebe, Huxley, Knight and Evans81; Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI)Reference Smets, Garssen, Bonke and De Haes82; Oxford Agoraphobic Avoidance Scale (O-AS)Reference Lambe, Bird, Loe, Rosebrock, Kabir and Petit83 with subscales for avoidance (O-AS-A) and distress (O-AS-D)Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams and Löwe84; Patient Health Questionnare 15-item version (PHQ-15)Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams85; Brief Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4)Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams and Löwe84; Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR)Reference Law, Neil, Dunn and Morrison86; Recovering Quality of Life (ReQol)Reference Keetharuth, Brazier, Connell, Bjorner, Carlton and Taylor Buck87; Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS)Reference Tennant, Hiller, Fishwick, Platt, Joseph and Weich88; Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)Reference Mundt, Marks, Shear and Greist89; Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS).Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer90

The magnitude of effect sizes ranged from around zero to very large. The largest positive effect size was d = 1.58 on a measure of functioning at 1-month follow-up.Reference Waite, Černis, Kabir, Iredale, Johns and Maughan27 Of note, a large negative effect size of d = −0.92 was obtained on a suicidal ideation subscale at 1-month follow-up.Reference Sheaves, Holmes, Rek, Taylor, Nickless and Waite26 This negative effect size resulted from the control group having a much higher starting mean suicidal ideation at baseline that decreased, whereas the suicidal ideation for the treatment group remained relatively stable from week 0 to week 8.

Across trials, there were a wide variety of outcomes and measures making it relatively challenging to synthesise. Depression and anxiety were measured in seven papers (53.8% of trials). A positive direction of effects was observed at all time-points immediately post-intervention for depression (range: d = 0.31–0.37) and anxiety (range: d = 0.41–0.61), suggesting in an improvement in symptoms. These all remained positive at follow-up, except for one study,Reference Sheaves, Holmes, Rek, Taylor, Nickless and Waite26 which found negative effects. At 1 month follow-up the range was d = −0.36 to 0.67 for depression, and d = −0.06 to 0.95 for anxiety.

Mental well-being was assessed in five papers (38.5% of trials) and, similarly, all effects were positive immediately post-intervention (range: d = 0.39–0.56), which suggests that participants’ mental well-being improved. They were also positive at follow-up except for one studyReference Sheaves, Holmes, Rek, Taylor, Nickless and Waite26 and ranged from d = −0.15 to 0.74. Finally, effect sizes for changes in quality of life (measured in five papers, representing 38.5% of trials) were all positive except in one studyReference Sheaves, Holmes, Rek, Taylor, Nickless and Waite26 at both post-intervention (range: d = −0.39 to 0.93) and follow-up (range: d = 0–1.46).

Treatment acceptability

Qualitative evidence

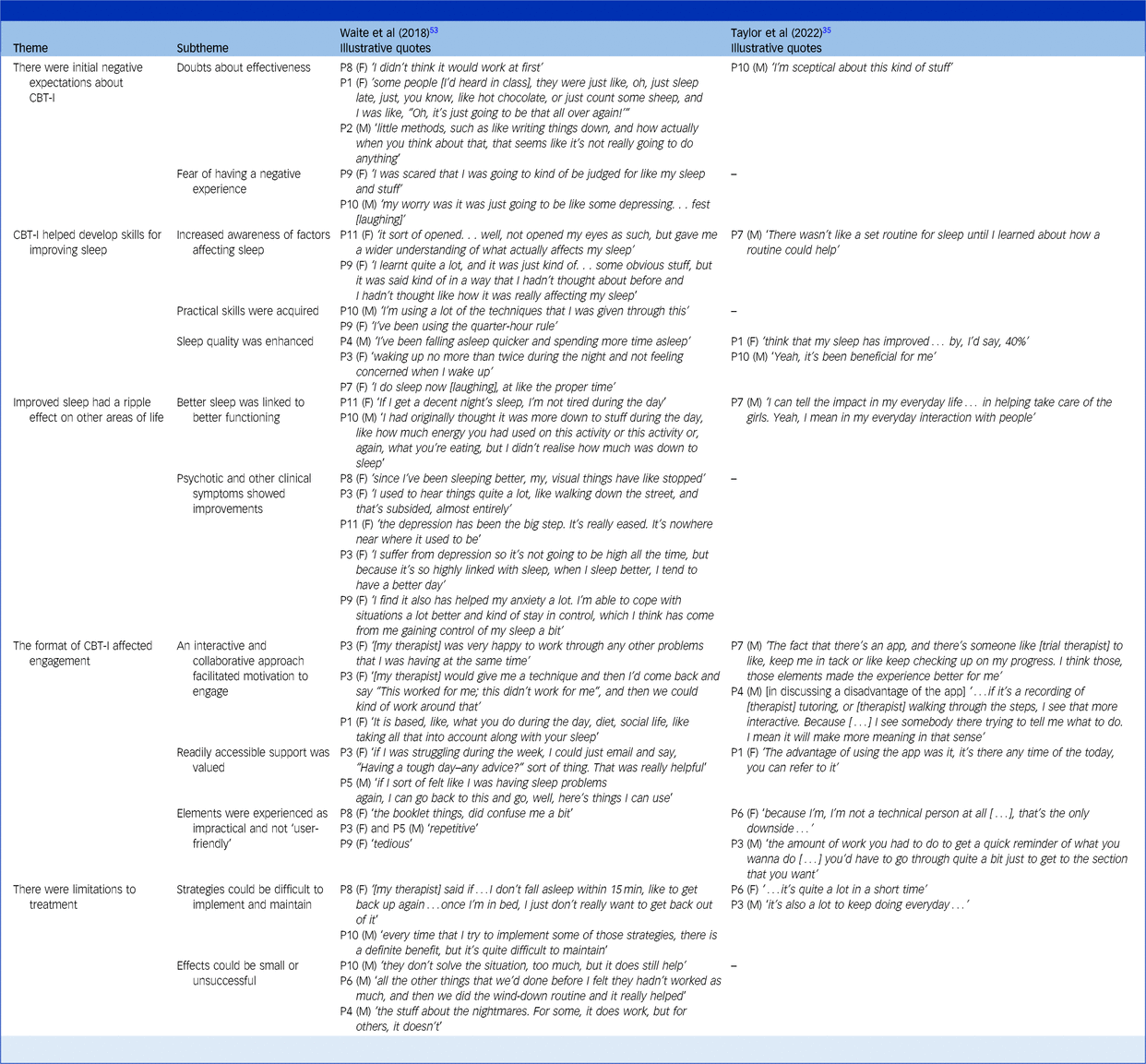

Treatment acceptability was evaluated through several different means. Relevant themes and quotes from two thematic analyses are organised in Table 8.Reference Taylor, Bradley and Cella35,Reference Waite, Bradley, Chadwick, Reeve, Bird and Freeman53 When organising themes, a realist philosophical orientation was adopted. Quotes were interpreted literally in relation to the question, ‘what does the data tell us about participants’ experiences of CBT-I treatment?’

Table 8 Qualitative themes and quotes regarding acceptability

CBT-I, cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia.

Themes and subthemes based on the research of Waite et alReference Waite, Bradley, Chadwick, Reeve, Bird and Freeman53 and Taylor et alReference Taylor, Bradley and Cella35 with accompanying participant quotes. Participant number and gender are indicated.

Five themes and 12 subthemes were developed from the data. The first theme was ‘initial negative expectations about CBT-I’. It appears that some participants were initially apprehensive about engaging in treatment. They were concerned about being prescribed ‘little methods’ such as counting sheep, and it was hard to see what difference treatment could make. In addition, some participants feared being ‘judged’, and that the content would be ‘depressing’.

The themes ‘CBT-I helped develop skills for improving sleep’ and ‘improved sleep had ripple effects on other areas of life’ show that many participants benefitted from treatment. Participants described learning what factors influenced their sleep and acquiring strategies to enhance their sleep quality. The consequences of better sleep could be widespread. Increased energy allowed them to engage in meaningful tasks, and they noticed improvements in mood, anxiety and psychotic experiences.

Participants also mentioned a theme of ‘limitations’. Strategies were not always successful and could require trial and error. Some strategies demanded high commitment, which could be difficult to maintain long term. These issues related to the theme that ‘the format of CBT-I affected engagement’. Some participants found booklets repetitive to completeReference Waite, Bradley, Chadwick, Reeve, Bird and Freeman53; while others found that technical aspects of a mobile app could pose a barrier.Reference Taylor, Bradley and Cella35 Across both studies, participants appreciated when treatment was collaborative and interactive. Participants in one studyReference Waite, Bradley, Chadwick, Reeve, Bird and Freeman53 praised how therapists tailored therapy to accommodate their preferences and lifestyle in one study when sessions were delivered in-person. By contrast, participants in the other studyReference Taylor, Bradley and Cella35 saw the lack of interaction with a therapist as a disadvantage of receiving treatment through a mobile app. Participants in both studies commented on how they valued regular access to support. One studyReference Waite, Bradley, Chadwick, Reeve, Bird and Freeman53 achieved this by allowing participants to email therapists and access workbooks, whereas participants in the other studyReference Taylor, Bradley and Cella35 mentioned the benefits of being able to access resources at any time via the app.

Drop-out and adverse events

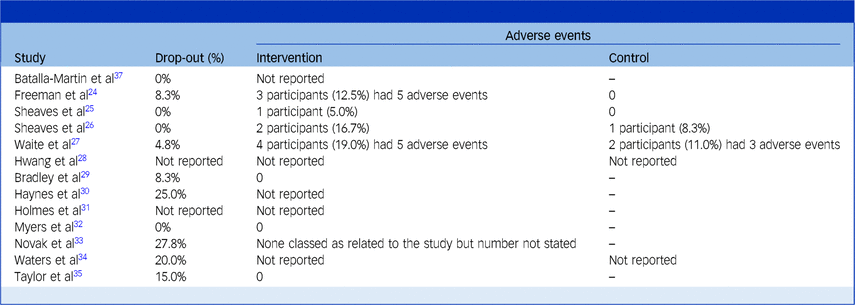

Table 9 presents rates of drop-out and adverse events. Drop-out was reported in 76.9% of trial studies. Three studies observed 0% drop-out from treatment.Reference Sheaves, Isham, Bradley, Espie, Barrera and Waite25,Reference Sheaves, Holmes, Rek, Taylor, Nickless and Waite26,Reference Myers, Startup and Freeman32 The highest rates were 25% and 27.8% in two studies that were set in acute in-patient wards and had weaker control for extraneous variables and follow-up with participants.Reference Haynes, Parthasarathy, Kersh and Bootzin30,Reference Novak, Packer, Paterson, Roshi, Locke and Keown33 Reasons for drop-out were not generally stated, and it was unclear whether any studies sought to follow-up with participants who withdrew to find out the reasons for this.

Table 9 Rates of drop-out and adverse events

Adverse events were commonly defined by papers as serious incidents that led to in-patient admission or disability, or were life-threatening. The proportion of participants who had adverse events in the treatment group was slightly numerically higher (7.6% of participants) than in the control (4.8%). However, it is not possible to draw conclusions from this as total numbers were low, and few studies reported this data. All studies deemed adverse events were unrelated to treatment.

Questionnaire data

Three studies offered treatment satisfaction questionnaires. Participants in one studyReference Sheaves, Holmes, Rek, Taylor, Nickless and Waite26 provided therapy satisfaction ratings to an independent assessor regarding their experiences of IRT. The median score was 9 out of 10 (interquartile range (IQR) 6.75–10), suggesting high satisfaction. These participants were also given a client satisfaction questionnaire; 56.2% were ‘very satisfied’ and the remainder responded that they were ‘mostly satisfied’. Another studyReference Waite, Černis, Kabir, Iredale, Johns and Maughan27 adopted the Abbreviated Acceptability Rating Profile (AARP)Reference Tarnowski and Simonian91 to evaluate CBT-I in young people at ultra-high risk of psychosis. The average score was 45.8 (s.d. 4.1) and the median was 48 (IQR 46–68), out of a possible maximum of 48. Participants in the third studyReference Taylor, Bradley and Cella35 used the ‘Experience Feedback Questionnaire’.Reference Edwards, Cella, Tarrier and Wykes92 The proportion of participants who rated the app-based CBT-I intervention as ‘enjoyable to use’ was 81.8%, ‘not disruptive to life’ was 72.7%, ‘not stopping usual activities’ was 81.1%, ‘not embarrassing’ was 100% and ‘easy to remember to use’ was 45.4%.

Discussion

This review addresses several gaps in the research literature regarding the evidence-base for CBT interventions for sleep problems in people with, or at risk of, psychosis. We first summarise the content of these CBT interventions, before proceeding to discuss their clinical effectiveness and acceptability.

CBT interventions

Insomnia (i.e. difficulties with falling or staying asleep) was the primary focus of all CBT interventions except for one study in which nightmares were targeted. Standardised protocols were frequently adapted by omitting sleep restriction on the basis of research linking sleep loss to psychotic experiences.Reference Waters, Chiu, Atkinson and Blom7,Reference Reeve, Emsley, Sheaves and Freeman39 Sleep compression (slowly delaying the earliest bedtime) is a standard component of CBT-I and may be a useful alternative to reducing time in bed and increasing sleep efficiency. Other adaptations included strategies to manage delusions and hallucinations that were preventing patients from falling asleep at night-time, problems with oversleeping to escape voices and fears of bed caused by past adverse experiences. Several CBT-I trials also offered to address nightmares, which reflects that insomnia and nightmares can be co-occurring problems for people with psychosis.Reference Sheaves, Isham, Bradley, Espie, Barrera and Waite25

Effectiveness on sleep outcomes

The results indicate that CBT is an effective treatment for sleep problems in people with psychosis. All studies observed an improvement on their primary sleep measure, although the quality of studies was highly variable. Out of the four RCT studies that were judged to be at low risk of bias, effect sizes ranged from medium to very large post-treatment and largely persisted at 3-months’ follow-up. These effects were also all significant except for the smallest RCT, which may have been too underpowered to detect this. The results are congruent with meta-analytic evidence that CBT-I and IRT are effective for healthy adults.Reference van Straten, van der Zweerde, Kleiboer, Cuijpers, Morin and Lancee93,Reference Yücel, van Emmerik, Souama and Lancee94 CBT is the recommended first-line treatment for insomnia and nightmares in clinical guidelines,18,Reference Aurora, Zak, Auerbach, Casey, Chowdhuri and Karippot21 and the findings lend support to its use for people with psychosis.

Effectiveness on psychotic outcomes

Eight studies measured psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions and paranoid thinking. Study quality ranged from low to critical risk of bias. Out of the four RCTs judged as low risk, effect sizes were small to medium in size and mostly positive. Yet, they were not significant, and some negative effects were obtained (i.e. suggesting either a deterioration in symptoms, or that the treatment group did not improve by as much as the control group). Accordingly, the evidence is inconclusive regarding whether CBT directed at sleep problems leads to improvements in psychotic symptoms.

Of note, in the research literature, a large-scale RCT involving a non-clinical student sample of 3755 participants found that CBT-I led to significant improvements in paranoia and hallucinations.Reference Freeman, Sheaves, Goodwin, Yu, Nickless and Harrison36 Their mediation analysis supported this interpretation, as improvements in sleep accounted for almost 40–60% of the change in hallucinations and paranoia after treatment. Given that it reported small effect sizes for paranoia and hallucinations, it is possible that the studies included in this review were insufficiently powered to detect significant results (the largest RCT had a sample size of only 50 participants). Alternatively, it is also possible that the link between sleep problems and psychosis is weaker than anticipated. This would have theoretical implications for Freeman’s modelReference Freeman4 in which sleep dysfunction is a putative cause of persecutory delusions.

Effectiveness for other clinical outcomes

In relation to other clinical outcomes, the findings are harder to interpret, partly because of the range of outcomes and measures. The most popular clinical domains were depression, anxiety, mental well-being and quality of life, but each domain was only captured in a small number of studies. Effect sizes were frequently in the direction suggesting an improvement in clinical symptoms, but were mostly non-significant, and thus the evidence is not conclusive.

Many studies in the wider research literature report that poor sleep is linked to depression and anxiety.Reference Hertenstein, Trinca, Wunderlin, Schneider, Zust and Feher95 People who are sleep deprived often describe increased negative emotions such as anger, frustration, sadness and irritabilityReference Killgore, Weber, Killgore and Weber96,Reference Tomaso, Johnson and Nelson97 and reduced ability to engage in meaningful activities.Reference Ben Simon and Walker98–Reference Wade100 Chronic lack of sleep is also associated with a reduced immune system functioning and other physical health problems.101 Given these findings, we hypothesised that there would be widespread ripple effects to treating people’s sleep problems. A possible explanation for why this was not clearly found is that studies were underpowered to detect effects. Another possibility is that the intervention requires time to improve people’s outcomes. If people have experienced years of sleep deprivation and consequently withdrawn from important areas of their life because of fatigue and low mood, it may take time for people to regain their energy, confidence and social networks and re-engage with meaningful activities. Future research should investigate longer-term outcomes.

Acceptability

The findings of this review indicate that CBT for sleep is acceptable. None of the adverse events that occurred across studies were related to treatment. A meta-analysis has estimated that ∼13% of people with schizophrenia drop out from psychosocial treatments,Reference Villeneuve, Potvin, Lesage and Nicole102 yet the majority of studies included in our review reported lower rates, suggesting that engagement was reasonably good. While drop-out rates ranged from 0 to 27.8%, the highest rates were found in studies with weaker methodological designs where researchers may have struggled to follow-up participants. Of note, no studies consulted participants regarding their reasons for dropping out. This would have been helpful to determine the degree to which drop-out was a valid measure of acceptability or was affected by other changes in participants’ circumstances.

The feedback from questionnaires and qualitative interviews provides stronger evidence. All, or nearly all, participants rated treatment acceptable, enjoyable and satisfying. Qualitative themes suggested that they found it useful and experienced widespread improvements in other areas of life. Participants valued an interactive approach in which support was readily accessible and user-friendly. The high levels of commitment required (e.g. in maintaining a consistent sleep window) could be a challenge when implementing strategies long term. A process of trial and error was sometimes required to find out what strategies worked for each participant personally.

Considerations around implementation

An individualised, biopsychosocial formulation-based approach is important to clarify what factors are maintaining each patient’s difficulties.Reference Persons, Brown, Diamond, Dobson and Dozois103 The clinical picture on sleep problems in psychosis is complex and the underlying causes can be varied. Erratic sleep patterns have been documented among patients with psychosis.Reference Wulff, Dijk, Middleton, Foster and Joyce104 Often, patients lack daytime activities and are socially isolated. Limited exposure to natural daylight and use of screens at night can result in circadian rhythm disruption where patients go to sleep too early (advanced phase) or too late, (delayed phase), or they oversleep (hypersomnia).Reference Wulff, Dijk, Middleton, Foster and Joyce104,Reference Strassnig, Harvey, Miller, Depp and Granholm105 Lifestyle factors such as napping, poor diet and nicotine can also be disruptive. Some patients experience high levels of night-time worry (including paranoid fears), which can result in insomnia by increasing hyperarousal.Reference Riemann, Spiegelhalder, Feige, Voderholzer, Berger and Perlis106 It is also important to note that medical sleep disorders may be present, such as sleep apnoea, which shows elevated rates among schizophrenia patients.Reference Myles, Myles, Antic, Adams, Chandratilleke and Liu107 Hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations can be caused by sleep disorders, particularly narcolepsy, or can be a part of psychosis. Patients’ medications may further affect their sleep.Reference Waite, Myers, Harvey, Espie, Startup and Sheaves17 For example, there are reports of certain antidepressants intensifying nightmares.Reference Tribl, Wetter and Schredl108 Sedative side-effects of antipsychotic medications can cause daytime fatigue. Hypnotics are commonly prescribed alongside antipsychotics but issues with tolerance and rebound can occur.

Unlike the full range of sleep problems described, the reviewed studies focused on insomnia and nightmares. Indeed, most trials required participants to be stabilised on medication and excluded anyone with a medical sleep disorder. No studies analysed the influence of comorbid sleep disorders and/or medication effects. Clinicians should assess for other sleep disorders and consider the impact of any medications. CBT is unlikely to be indicated or effective for all sleep problems in psychosis, and its appropriateness should be considered in conjunction with existing good clinical practice, including working within a multidisciplinary context and a wider biopsychosocial formulation. We refer to a helpful guide for treating sleep problems in schizophrenia patientsReference Waite, Myers, Harvey, Espie, Startup and Sheaves17 that advises linking in with the wider clinical team to establish if a medication review is required and collaborating with relevant organisations (e.g. supported living to implement lifestyle changes). For certain sleep disorders, clinical guidelines advise medical interventions rather than CBT (e.g. continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines for sleep apnoea).23

Strengths and limitations

We provide a pre-registered, rigorous, systematic review of CBT interventions directed at sleep in people with psychosis. Our scope was comprehensive as we considered the full range of psychotic symptoms from at-risk state to full-blown disorders, both quantitative and qualitative methods, a wide range of outcomes and both efficacy and acceptability assessments. A further strength of our study is that a rigorous methodology was used to search for and critically appraise studies, with a second reviewer duplicating several stages of the analysis to ensure interrater reliability. A mixed-methods approach allowed us to triangulate different forms of evidence and strengthen the credibility of our conclusions. We note a recent quantitative-only review with fewer included studies, which was not pre-registeredReference Ugurlu, Ugurlu, Sahin, Kamis and Caykoylu109 and likely had inflated estimates, because of an inclusion of the same data-set twiceReference Waters, Chiu, Atkinson and Blom7,Reference Chiu, Ree, Janca, Iyyalol, Dragovic and Waters110 and an error in the reporting of another paper that we highlighted.Footnote a The robust, converging and accurate results of our review have clear clinical implications for healthcare professionals seeking to support people with psychosis.

There were nonetheless several limitations in the ability to draw conclusions regarding treatment effectiveness, feasibility and acceptability. There were few high-quality studies. Sample sizes were small, resulting in large confidence intervals that may have meant they were underpowered to detect significant results. The wide variety of measures to assess psychosis and other clinical symptoms made it difficult to generalise. Discharge was a barrier to accessing the full course of treatment in some of the in-patient studies, which made it difficult to compare community versus in-patient treatment. As stated in our pre-registered analysis plan, we intended to conduct a meta-analysis; however, there were too few comparable studies to yield meaningful results. Low numbers of studies also meant we could not identify factors influencing treatment effectiveness including patient-status (full diagnosis versus at-risk mental state), treatment focus (insomnia versus nightmares), specific adaptations, settings, comorbidity and medication effects.

The two qualitative studies included in this review added rich insights into participants’ experiences. However, they did not explain the kind of thematic analysis they were performing or its theoretical underpinnings. This is a widespread problem in thematic research.Reference Braun and Clarke111 The current review adopted a realist/essentialist position in seeking to ‘stay close’ to participants’ literal meanings when evaluating treatment acceptability. However, limitations affecting the generalisability of our findings include small numbers of participants and researcher subjectivity influencing the selection of themes. It is unknown whether the results replicate across different settings, modes of treatment, and so on.

Finally, White Western participants tended to be over-represented, and ethnicity was not reported for some studies. This reflects wider problems of underrepresentation of ethnic groups in clinical research.Reference Redwood and Gill112 Migrant and ethnic minority status is associated with increased odds of psychotic disorder.Reference Termorshuizen, van der Ven, Tarricone, Jongsma, Gayer-Anderson and Lasalvia113 It would have been useful to investigate treatment effectiveness and acceptability across cultural contexts.

Future directions

Large-scale RCTs are necessary to establish psychotic and other clinical outcomes. Further investigations of treatment effectiveness and acceptability are also needed for people at risk of psychosis, people from a range of cultural and ethnic backgrounds and CBT for nightmares. It would be helpful to understand reasons for treatment drop-out, and longer-term consequences of treatment (i.e. greater than 3 months’ follow-up). Many clinical practitioners do not routinely ask about patients about their sleep problems.Reference Rehman, Waite, Sheaves, Biello, Freeman and Gumley114 Indeed, clinical guidelines for psychotic disorders, including those by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence,115 do not focus on sleep. Thus, it would also be useful to investigate how to bridge the research–practice gapReference Robinson and Moghaddam116 and engage practitioners in assessing and offering CBT for sleep problems in this patient group.

In conclusion, this review shows that CBT is highly effective and acceptable in treating sleep problems in people with, or at risk of, psychosis. However, results were inconclusive regarding the wider impact of treatment on patients’ psychotic and other clinical symptoms. Clinicians should be aware that adaptations to standard treatment protocols are commonly made for this population (e.g. omitting sleep restriction) and that certain adjustments may enhance acceptability (e.g. adopting a collaborative approach). High-quality, large-scale RCTs are required to understand the full benefits of treatment and explore what factors influence these.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.86

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Author contributions

H.W. took a lead role in formulating the research questions, analysing the data and writing the article, as part of her clinical doctorate. A.L.-Z. and L.C.J. were supervisors and were involved in formulating research questions and providing guidance and feedback in the write-up of the article. R.B. supported the analyses and write-up of the article.

Funding

H.W. and R.B. are funded by Oxford Health National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust for doctoral training in clinical psychology. A.L.-Z. also reports funding from a Medical Research Council Clinician Scientist Fellowship (MR/Y009460/1), John Fell Fund from the Oxford University Press (0014097), National Institute of Health Research Imperial Biomedical Research Centre hosted at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (PSP955) and Committee for Children Junior Research Fellowship at Linacre College.

Declaration of interest

None.

Transparency declaration

The authors affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported and that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.