Self-harm presentations to hospital emergency departments are common and have serious consequences. Reference Bergen, Hawton, Waters, Cooper and Kapur1,Reference Bergen, Hawton, Waters, Ness, Cooper and Steeg2 In the UK, the risk of suicide has been reported to be approximately 50 times greater for patients in the year after a self-harm episode compared with the general population. Reference Hawton, Bergen, Cooper, Turnbull, Waters and Ness3 It may be even higher for those with repeated episodes. Reference Haw, Bergen, Casey and Hawton4,Reference Zahl and Hawton5 Good-quality assessment of people when they present to hospital with self-harm is a core part of clinical practice in many countries and can reduce risk of repeat self-harm. 6–Reference Bolton, Gunnell and Turecki8 Following an initial assessment by emergency department staff, liaison psychiatry clinicians may subsequently provide a more comprehensive evaluation of needs and risk, often including formal risk scales. 6,Reference Kapur, Murphy, Cooper, Bergen, Hawton and Simkin9,Reference Hawton10 The use of risk scales in the assessment of self-harm is contentious, 6,11,Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Steeg, Davies, Hawton and Gunnell12 with some clinical guidelines advocating the use of psychometrically tested scales over locally developed proformas 11 and others suggesting that risk instruments should not be used to predict outcome but may be used to help structure assessments. 6 Despite limited evidence for their effectiveness, risk scales are in widespread use in hospital services. Our recent study of 32 hospitals in England found over 20 tools in use, indicating uncertainty over which are the best scales following self-harm. Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Steeg, Davies, Hawton and Gunnell12 This reflects the situation internationally. Reference Bolton, Gunnell and Turecki8 This uncertainty concerning risk-prediction scales may be indicative of the inconsistency in the evidence base. 6,Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Davies, Hawton, Gunnell and Kapur13 Our recent systematic review of cohort studies evaluating the predictive accuracy of scales included 8 studies Reference Bilén, Ponzer, Ottosson, Castrén, Owe-Larsson and Ekdahl14–Reference Waern, Sjöström, Marlow and Hetta21 and 11 scales. Sensitivity for identifying repeat episodes ranged from 97% for the Manchester Self-Harm Rule Reference Cooper, Kapur, Dunning, Guthrie, Appleby and Mackway-Jones17 to 3% for the Modified SAD PERSONS scale, Reference Hockberger and Rothstein22 and positive predictive values ranged from 70% for the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Reference Patton and Stanford23 to 7% for the Modified SAD PERSONS Scale. Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Davies, Hawton, Gunnell and Kapur13 Other reviews report similarly variable performance across risk scales. Reference Bolton, Gunnell and Turecki8,Reference Randall, Colman and Rowe24–Reference Chan, Bhatti, Meader, Stockton, Evans and O'Connor26

On the basis of the published work it is not possible to identify the best performing scale. Direct comparison of different instruments between studies is not appropriate because of wide variations in methodological quality, case mix, study setting, scoring thresholds, follow-up and reporting. Analyses also tend to be restricted to those based on available contingency tables (for example, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values). Without access to raw data, it is not possible to investigate more comprehensive measures of performance such as the ‘area under the receiver operating characteristic curve’, which evaluates the performance of a scale at different thresholds. Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Davies, Hawton, Gunnell and Kapur13,Reference Bewick, Cheek and Ball27 In order to compare different risk scales, we tested the predictive utility of widely used instruments as well as clinician and patient-rated global measures of risk in a multicentre cohort study in England with a 6-month follow-up. Our overall aim was to compare the performance of the scales in people who were referred from the emergency department to psychiatric liaison services following self-harm. This evidence is important for clinicians, service providers, commissioners and policymakers in order to critically evaluate the use of risk scales. To increase the ecological validity of the study, the clinicians administered the risk assessments as close to the usual psychiatric assessment as possible. Our specific objectives were to: (a) estimate the predictive accuracy of the scales for repeat self-harm using published cut-offs; (b) plot receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and examine the area under the curve (AUC) for each of the scales; (c) estimate the predictive accuracy of the scales for repeat self-harm using data-determined optimal cut-offs that maximise sensitivity and specificity in this sample. We hypothesised that specific scales, which are often based on the most important epidemiological risk factors, 6,Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Davies, Hawton, Gunnell and Kapur13–Reference Waern, Sjöström, Marlow and Hetta21 would perform better than global measures of clinician- or patient-rated risk.

Method

We conducted a multicentre prospective cohort study to examine the diagnostic accuracy of risk scales for repeat self-harm. The study was reviewed and approved by the Central Manchester Research Ethics Committee (REC No: 13/NW/0838) prior to commencement.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants were patients aged 18 years or over who were referred from emergency departments to psychiatric liaison services for assessment following self-harm in five large teaching hospitals in England (Brighton, Bristol, Derby, Manchester and Oxford), between March 2014 and January 2015. We did not include people under the age of 18 years because, in the UK, service provision is different for younger people. Reference Kapur, Steeg, Webb, Haigh, Bergen and Hawton28,Reference Majid, Tadros, Tadros, Singh, Broome and Upthegrove29 We focused on people who received a psychiatric assessment because risk assessments are a key component of psychiatric practice and are in widespread use. 6,Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Steeg, Davies, Hawton and Gunnell12 People who are referred for psychiatric assessment may also be at higher risk of adverse outcomes than patients who are not referred. Reference Kapur, Steeg, Turnbull, Webb, Bergen and Hawton30,Reference Steeg, Haigh, Webb, Kapur, Awenat and Gooding31 Previous research suggests that patients who present with self-harm and receive a psychiatric assessment are older, and less likely to be unemployed or use self-cutting as a method of self-harm and more likely to have factors suggestive of current mental illness or treatment than those who were not assessed. Reference Kapur, Murphy, Cooper, Bergen, Hawton and Simkin32 People who were unable to understand English were excluded as the risk scales have not been translated or tested in non-English-speaking groups. People who were unable to consent (for example, because of impaired consciousness or active psychosis) or who were deemed too unwell or aggressive to participate by the clinical team were also excluded. Episodes where the patient did not stay for psychiatric assessment or treatment were also not included.

Service provision

The five research sites were based in urban areas and varied in population size (150 000–500 000), deprivation (from the 5th most deprived area out of 326 local authorities to the 166th), ethnicity (proportion of individuals from Black and minority ethnic groups 5.8–33.3%), and rates of unemployment (proportion unemployed 3.6–8.1%). The services for people who self-harm were provided by multidisciplinary psychiatric liaison teams that included psychiatric nurses, social workers, consultant psychiatrists and junior doctors. Junior doctors and/or crisis teams provided out-of-hours services at all sites. The teams varied in their hours of operation; three were available 24 h, 7 days a week, and two of the teams were available from around 07.00 to 21.00. The proportion of patients who received a psychiatric assessment ranged from 45 to 77%. Consistent with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, each patient episode of self-harm is treated in its own right as a one-time visit. 6 The duration of assessments is dependent on patient need but they usually have a modal duration of around 1 h.

Case definition

There are debates over nomenclature in suicide prevention research and several terms are used to denote self-harm and suicidal behaviour. Reference Silverman, Berman, Sanddal, O'Carroll and Joiner33,Reference O'Carroll, Berman, Maris, Moscicki, Tanney and Silverman34 Terms such as ‘non-suicidal self-injury’ (self-injury without intent) or suicide attempts (self-harm with suicidal intent) are frequently used to classify patients; Reference Andover, Morris, Wren and Bruzzese35 but focusing on specific methods and/or suicidal intent may be clinically problematic. Reference Kapur, Steeg, Webb, Haigh, Bergen and Hawton28,Reference Owens, Kelley, Munyombwe, Bergen, Hawton and Cooper36 Suicidal behaviour is often characterised by ambivalence and changeability, intent may vary both between and within episodes, and even apparently low-intent episodes are associated with high mortality risk. Reference Kapur, Steeg, Webb, Haigh, Bergen and Hawton28,Reference Owens, Kelley, Munyombwe, Bergen, Hawton and Cooper36,Reference Clements, Jones, Morriss, Peters, Cooper and While37 Therefore, consistent with national UK guidance 6 we included all presentations for self-harm in this study – defined as episodes of intentional self-injury or self-poisoning, irrespective of motivation or degree of suicidal intent. Reference Hawton, Zahl and Weatherall38 The same definition was used across all research sites.

We calculated that a sample size of 480 would provide adequate statistical power to estimate diagnostic properties with reasonable precision (for example, assuming a repeat rate of 15%, the 95% confidence interval around a sensitivity of 0.80 would be 0.69–0.89) and also to detect a difference between the accuracy of scales. We therefore had a target sample size of approximately 100 per centre. Reference Owens, Horrocks and House39,Reference Carroll, Metcalfe and Gunnell40

Procedure

The research team met with clinicians at all sites on several occasions to familiarise them with the study procedure and risk scales and to answer any queries. In all cases clinicians (largely nurses and psychiatrists) obtained informed consent from patients as well as conducting the assessments. The assessments generally took place in the emergency department or on a medical ward. We adopted an episode-based approach to analysis, that is, we investigated repetition subsequent to each episode of self-harm, which meant that some individuals were included more than once. This more readily reflects the clinical reality of presentation to services Reference Steeg, Kapur, Webb, Applegate, Stewart and Hawton19,Reference Cooper, Kapur and Mackway-Jones41 and is consistent with national guidelines that suggest each episode should be assessed in its own right. 6

Scales

The assessment scales were selected for inclusion in the study on the basis of a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of risk scales in previous studies Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Davies, Hawton, Gunnell and Kapur13 as well as practical service considerations (such as time taken to complete the scale – a scale with a large number of items would be highly unlikely to be adopted in routine practice). They included basic clinical and demographic information. The Manchester Self-Harm Rule, ReACT Self-Harm Rule, Modified SAD PERSONS scale, and SAD PERSONS scale comprised items collected as part of the clinical assessment. The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale included specifically collected data. Because of this, it was not possible to randomise the order of administration of the scales. On the advice of the clinical teams and in order not to disrupt the routine clinical assessments the study was in general introduced after the clinical interviews.

For the risk scales (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, Reference Patton and Stanford23 Manchester Self-Harm Rule, Reference Cooper, Kapur, Dunning, Guthrie, Appleby and Mackway-Jones17 ReACT Self-Harm Rule, Reference Steeg, Kapur, Webb, Applegate, Stewart and Hawton19 SAD PERSONS scale, Reference Patterson, Dohn, Bird and Patterson42 Modified SAD PERSONS scale Reference Hockberger and Rothstein22 ) a priori cut-offs were chosen on the basis of previous literature. Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Davies, Hawton, Gunnell and Kapur13 It was, of course, not possible to have full masking of the scales, but clinicians were masked to how they were scored and the scoring thresholds. We also included a clinician and patient global evaluation of risk scale. These each consisted of a single question, which asked the respondent to estimate the likelihood of repeat self-harm within 6 months on a 1–10 Likert-type scale (for example: ‘How likely do you think it is, that [you]/[the patient] will repeat self-harm within the next six months? Please indicate on this scale (with 1 as extremely unlikely and 10 extremely likely)’. We used the mid-point as our cut-off point (i.e. 0 to 5, low risk; 6+ high risk). Further details are available from the authors on request. Further details on all the scales, the assessment, and scoring are presented in online supplement DS1.

Reference standard

The outcome for the study was hospital-treated repeat self-harm within 6 months of presentation and was ascertained masked to index test results from hospital databases by linking National Health Service (NHS) and local hospital numbers where available. Where these were not available, cases were linked by using a combination of date of presentation, name and age. Teams in the individual centres carried out all data linkage and identifiable data were not passed to the research team. The date of each subsequent episode of self-harm was ascertained and clinicians used the standard definition of self-harm described above. The time frame of 6 months was selected, as this is a high-risk period and one that has often been used in previous studies. Reference Kapur, Cooper, Hiroeh, May, Appleby and House43,Reference Cooper, Steeg, Bennewith, Lowe, Gunnell and House44

Analysis

Predictive accuracy statistics

The diagnostic accuracy of each of the scales in Table 1 was evaluated using a range of diagnostic accuracy statistics and 95% confidence intervals, including: sensitivity, specificity, negative/positive predictive values, positive/negative likelihood ratios and the diagnostic odds ratio using predetermined published cut-off points where available (see online supplement DS2 for definitions). Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Davies, Hawton, Gunnell and Kapur13 Meta-analysis using random-effects modelling (DerSimonian–Laird method) Reference DerSimonian and Laird45 was used to explore variation by centre in sensitivity and specificity. Heterogeneity was evaluated as present if Cochran's Q was less than 0.10 and Higgins I 2 was greater than 50%. Reference Higgins and Green46 The scales were analysed separately. ROC curves, which plot sensitivity on the y-axis and 1 – specificity on the x-axis for all possible cut-off points, were constructed for each total scale score and overall discriminative ability was evaluated by the AUC. Reference Bewick, Cheek and Ball27 Higher values for the AUC indicate greater discriminatory power. An AUC of 1.0 indicates a perfect test and 0.5 indicates the result is no better than chance. Reference Hosmer, Lemeshow and Sturdivant47 We compared the formal scales to the clinician- and patient-rated global measures of risk by calculating the difference between the respective AUCs. Reference DeLong, DeLong and Clarke-Pearson48 For our third aim, optimal cut-off points for our sample were selected using Youden's J index, which maximises the difference between true and false positive rates (provides the point with the furthest distance from the diagonal line). Reference Bewick, Cheek and Ball27 Standard errors and exact binomial exact confidence intervals were calculated using the DeLong method. Reference DeLong, DeLong and Clarke-Pearson48

Table 1 The distribution of the seven scales' results and repeat self-harm by 6 months according to predefined cut-off points

| Scale, thresholds | Did not repeat (n = 338, 70%) |

Repeat self-harm (n = 145, 30%) |

Total (n = 483) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manchester Self-Harm Rule | |||

| Low risk (0) | 67 (94.4) | 4 (5.6) | 71 (14.7) |

| Moderate/high risk (1+) | 271 (65.8) | 141 (34.2) | 412 (85.3) |

| ReACT Self-Harm Rule | |||

| Low risk (0) | 79 (94.0) | 5 (6.0) | 84 (17.4) |

| Moderate/high risk (1+) | 259 (64.9) | 140 (35.1) | 399 (82.6) |

| SAD PERSONS scale | |||

| Low (0–4) | 303 (71.3) | 122 (28.7) | 425 (88.0) |

| Moderate (5–6) | 29 (58.0) | 21 (42.0) | 50 (10.4) |

| High (7–10) | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | 8 (1.7) |

| Modified SAD PERSONS scale | |||

| Low (0–5) | 267 (72.0) | 104 (28.0) | 371 (76.8) |

| Moderate (6–8) | 64 (61.5) | 40 (38.5) | 104 (21.5) |

| High (>8) | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | 8 (1.7) |

| Clinician global scale | |||

| <5 | 217 (85.1) | 38 (14.9) | 255 (52.8) |

| 6+ | 121 (53.1) | 107 (46.9) | 228 (47.2) |

| Patient global scale | |||

| <5 | 213 (82.9) | 44 (17.1) | 257 (53.2) |

| 6+ | 125 (55.3) | 101 (44.7) | 226 (46.8) |

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale a | |||

| <96 | 331 (70.3) | 140 (29.7) | 471 (97.5) |

| 97+ | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 12 (2.5) |

a. Cut-off based on Randall et al. Reference Randall, Rowe and Colman20

Scales were generally very well completed, with the exception of the 30-item Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, and we used multiple regression imputation for episodes that had less than 5% missing data on this scale. Reference Allison49 SPSS version 20, Stata 13.0 and OpenEpi (Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, www.OpenEpi.com) were used for the analyses.

Patient involvement

An expert-by-experience was a co-applicant on the NIHR Programme Grant and actively contributed to the study design. Patient advisors, carers and clinicians contributed to the research questions, scales (for example, we included patient and clinician global estimations of risk) and outcomes. There was also patient input into our dissemination plan, which includes dissemination to participants and the relevant patient community.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Participating clinicians considered 1301 patients referred to liaison psychiatry services after self-harm for inclusion in the study, of whom 421 were judged not to be appropriate (for example, they were too unwell, too distressed, intoxicated or in police custody) and 353 refused to participate. The consenting sample resulted in data on 514 separate episodes of self-harm that was reduced to 483 after exclusion of episodes with significant missing data on key scales. The 483 episodes of self-harm represented data from 464 separate individuals, with 12 individuals appearing in the data-set more than once. Psychiatric liaison nurses conducted the majority of the assessments (n = 374/483, 77.4%). Psychiatrists conducted 82/483 of the assessments (17%) and the remainder were conducted by junior doctors/nurses or other allied health professionals (such as social workers, therapists) that were attached to the clinical teams (n = 26/483, 5.4%). The assessor was unknown for one of the assessments (0.2%).

The median age for the sample was 33 years (interquartile range 22–42 years, range 18–88 years), and over half were women (298/483, proportion women 61.7%) and under 35 years of age (297/481, 61.7%). The majority of the sample was of White ethnicity (455/483, 94.2%). Many participants had a self-reported history of previous self-harm (359/483, 74.3%), and 245/483 (50.7%) had had an episode of self-harm in the past 12 months. Over half of the sample had a prior psychiatric history (310/483, 64.2%). The most common method of self-harm was self-poisoning (393/483, 81.4%), followed by self-cutting (71/483, 14.7%) and other methods (19/483, 3.9%) (for example drowning, asphyxiation). In the 6 hours prior to the self-harm episode just over half of the participants had used alcohol (248/470, 52.8%) and 11% recreational drugs (51/463). The episode-based 6-month self-harm repetition rate was 30% (145/483).

Scores on the risk scales and repeat self-harm

The distribution of the tested scale results using established cut-offs and for the clinician and patient global estimations of risk using the median cut-off points are presented in Table 1.

Performance of the scales

Diagnostic performance varied greatly. Sensitivity, which is the proportion of patients who repeated self-harm and were correctly identified by the scale as high risk, ranged from 1% for the SAD PERSONS scale using the moderate/high-risk threshold to 97% for the Manchester Self-Harm Rule and ReACT Rule at the recommended cut-off of one. Positive predictive values, which are the probability that a patient identified as high risk by the test actually went on to repeat self-harm, were low for the high sensitivity scales (Manchester Self-Harm Rule and the ReACT Rule) (34 and 35%). Positive predictive values were highest for the clinician global estimation of risk scale (47%), followed by the patient global estimation of risk scale (44%), using the mid-point cut-off for each. The full range of diagnostic accuracy statistics for the scales when using a priori cut-off points are presented in Table 2, and those for optimised cut-offs, which maximise sensitivity and specificity according to Youden's J index, in Table 3.

Table 2 Diagnostic accuracy statistics with 95% confidence intervals for a priori cut-off points

| Scales, cut-off | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) |

Specificity, % (95% CI) |

Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) |

Negative predictive value, % (95% CI) |

Likelihood ratio, positive (95% CI) |

Likelihood ratio, negative (95% CI) |

Diagnostic OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manchester Self-Harm Rule, 0/1+ | 97 (93–99) | 20 (16–24) | 34 (29–38) | 94 (86–98) | 1.2 (1.2–1.2) | 0.1 (0.1–0.3) | 8.7 (3.1–24.4) |

| ReACT Self-Harm Rule, 0/1+ | 97 (92–99) | 23 (19–28) | 35 (31–39) | 95 (87–97) | 1.3 (1.3–1.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 8.5 (3.4–21.6) |

| SAD PERSONS scale | |||||||

| 0–4/5–6 | 16 (11–23) | 90 (86–93) | 40 (28–53) | 72 (67–76) | 1.6 (1.0–2.6) | 0.9 (0.9–0.9) | 1.7 (0.9–2.9) |

| 5–6/7–10 | 1 (0–5) | 99 (96–99) | 25 (07–59) | 70 (66–74) | 0.8 (0.0–1.0) | 1.0 (0.1–1.0) | 0.8 (0.2–4.0) |

| Modified SAD PERSONS scale | |||||||

| 0–5/6–8 | 28 (21–36) | 79 (74–83) | 36 (27–45) | 72 (67–77) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 1.5 (0.9–2.3) |

| 6–8/8+ | 1 (1–7) | 98 (96–99) | 13 (2–47) | 70 (66–74) | 0.3 (0.0–3.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.3 (0.0–2.7) |

| Clinician global scale, a 0–5/6+ | 74 (66–80) | 64 (59–69) | 47 (41–53) | 85 (80–90) | 2.1 (2.0–2.1) | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) | 5.0 (3.2–7.8) |

| Patient global scale, a 0–5/6+ | 69 (61–77) | 63 (57–68) | 44 (37–50) | 83 (78–87) | 1.9 (1.8–1.9) | 0.5 (0.5–0.5) | 3.9 (3.3–5.9) |

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, b 0–96/97+ | 3 (1–8) | 98 (96–99) | 42 (19–68) | 70 (67–74) | 1.7 (0.0–1.8) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.7 (0.5–5.4) |

a. Mid-point cut off.

b. Cut-off used by Randall et al. Reference Randall, Rowe and Colman20

Table 3 Diagnostic accuracy statistics with 95% confidence intervals at optimal cut-off points using Youden's J Index

| Scales, cut-off | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) |

Specificity, % (95% CI) |

Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) |

Negative predictive value, % (95% CI) |

Likelihood ratio, + (95% CI) |

Likelihood ratio, − (95% CI) |

Diagnostic OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manchester Self-Harm Rule, 0–3/4+ | 69 (61–76) | 66 (61–71) | 47 (40–53) | 84 (78–87) | 2.0 (2.0–2.1) | 0.5 (0.5–0.5) | 4.4 (2.9–6.6) |

| ReACT Self-Harm Rule, 0–2/3+ | 79 (71–86) | 52 (47–57) | 41 (36–47) | 85 (80–89) | 1.6 (1.6–1.7) | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) | 4.0 (2.5–6.3) |

| SAD PERSONS scale, 0–2/3+ | 88 (82–93) | 22 (18–27) | 33 (28–37) | 81 (72–88) | 1.1 (1.1–1.1) | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | 2.1 (1.2–3.7) |

| Modified SAD PERSONS scale, 0–5/6+ | 50 (42–57) | 62 (57–67) | 36 (30–43) | 74 (69–79) | 1.3 (1.3–1.4) | 0.8 (0.8–0.8) | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) |

| Clinician global scale, 0–5/6+ | 74 (66–80) | 64 (59–69) | 47 (41–53) | 85 (80–89) | 2.1 (2.0–2.1) | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) | 5.0 (3.3–7.7) |

| Patient global scale, 0–5/6+ | 70 (62–77) | 63 (58–68) | 45 (38–51) | 83 (78–87) | 1.9 (1.8–1.9) | 0.5 (0.5–0.5) | 3.9 (2.6–5.9) |

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, 0–75/76+ | 63 (55–70) | 60 (55–66) | 41 (34–46) | 79 (74–84) | 1.6 (1.5–1.6) | 0.6 (0.6–0.6) | 2.6 (1.7–3.9) |

Heterogeneity between sites

The performance of the Manchester Self-Harm Rule, ReACT Self-Harm Rule, the patient global scale, the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale and the Modified SAD PERSONS scale using a priori cut-offs was similar across sites, with no statistical evidence of heterogeneity. For the clinician global rating of risk, specificity varied from 58 to 82% (τ2 = 0.16, χ2 = 13.4, d.f. = 5, P = 0.01, I 2 = 70.4%). Specificity also varied for the SAD PERSONS scale (between 74 and 96%), (τ2 = 0.46, χ2 = 14.6, d.f. = 5, P<0.01, I 2 = 73%).

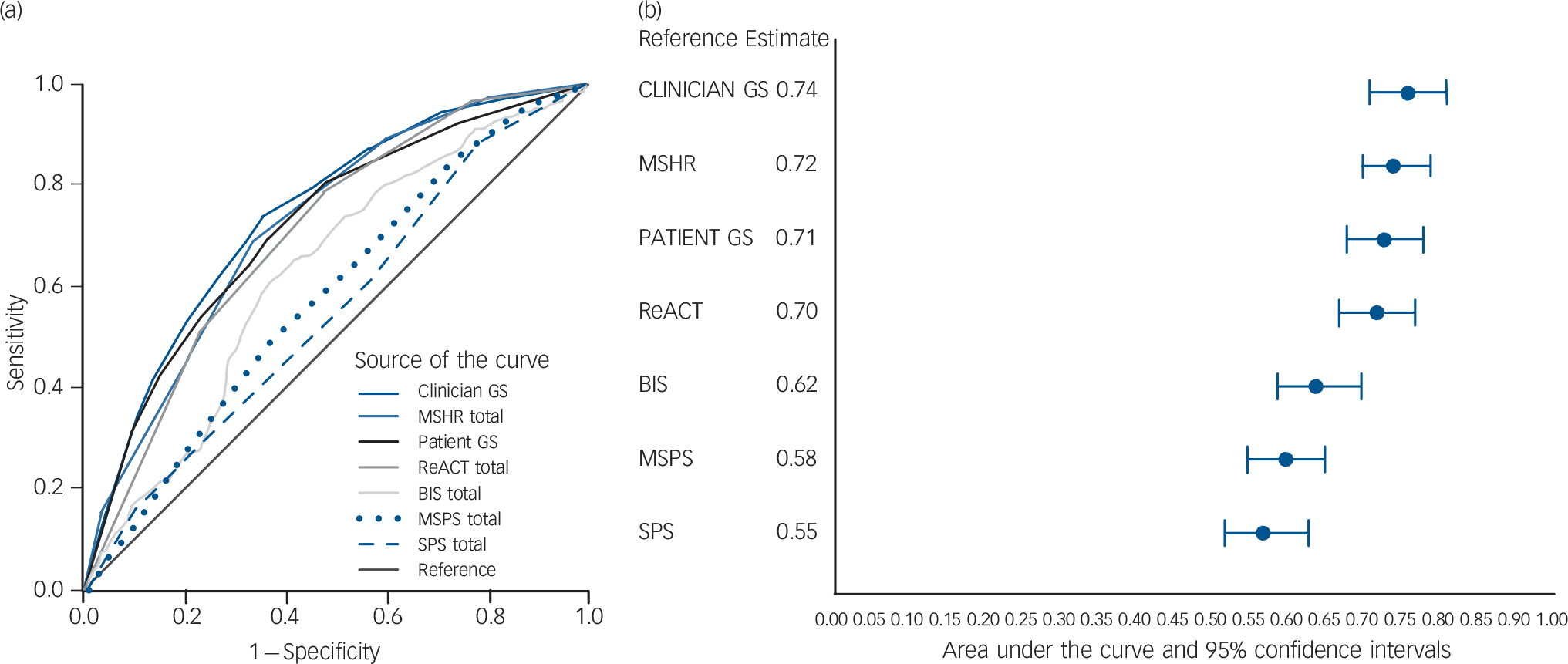

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curves

The ROC curves that show the relationship between the sensitivity and specificity for the respective scales are presented in Fig. 1(a) and 1(b) along with the AUC and 95% confidence intervals for the respective scales. The AUCs of the seven scales varied between bordering on no better than chance for the SAD PERSONS scale (0.55) and Modified SAD PERSONS scale (0.58), to poor for the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (0.62) and fair accuracy for the ReACT Self-Harm Rule (0.70), patients' estimation of risk (0.72), Manchester Self-Harm Rule (0.72) and clinicians' global estimation of risk (0.74).

Fig. 1 The receiver operator characteristic curves (a) show the relationship between the proportion of true positives (sensitivity) and the proportion of false positives for the seven scales. The forest plot (b) shows the area under the curve estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the scales.

Clinician GS, clinician global scale; MSHR, Manchester Self-Harm Rule; Patient GS, patient global scale; ReACT, ReACT Self-Harm Rule; BIS, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; MSPS, Modified SAD PERSONS Scale; SPS, SAD PERSONS Scale.

Regarding global estimations of risk, both the clinician and patient scales were significantly better than the SAD PERSONS scale (AUC difference: 0.19, P<0.001; AUC difference: 0.16, P<0.001, respectively), the Modified SAD PERSONS scale (AUC difference: 0.16, P<0.001; AUC difference: 0.13, P<0.001) and the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (AUC difference: 0.12, P50.001; AUC difference: 0.09, P<0.001). There were no significant differences between the global estimates of risk and the remainder of the scales.

Discussion

Main findings

The results of this multisite prospective cohort study indicate that risk scales generally performed poorly in terms of predicting repeat self-harm. High sensitivity scales tended to have poor specificity and vice versa. Possible exceptions to this were clinician- and patient-rated measures of global risk. Contrary to our hypothesis, formal risk scales performed no better than the global assessments and in some cases there was evidence (on the basis of ROC curves) that performance was significantly worse. Using our available study data to select optimal cut-offs in this sample resulted in better performance (Table 3), but these were essentially post hoc estimations of ‘best case’ predictive utility and would not be generalisable to other samples. Our findings suggest that risk assessment tools have limited clinical utility in the assessment of self-harm.

Strengths and limitations

This is one of the few studies to compare widely used risk scales following self-harm in a ‘head-to-head’ prospective cohort study. The risk scales were administered by treating clinicians and prospectively evaluated in a large real-world sample of patients referred to liaison psychiatric services for self-harm. We used clear consistent terminology across sites and had near-complete patient follow-up, although it is possible that some patients could have moved or died during the study period without the knowledge of the clinical services. We used a broad definition of suicidal behaviour consistent with UK research and clinical practice. In fact, a post hoc analysis involving the 357 self-poisoning episodes (which would be consistently included in most definitions of suicidal behaviour internationally) generated similar results.

There is a risk of sampling bias as patients who refused to complete the research assessments or who were deemed inappropriate to participate were not included in the study, which may affect the generalisability of the results. Recent large multi-centre studies of self-harm in England suggest our sample was similar to overall patient samples in terms of gender, Reference Steeg, Kapur, Webb, Applegate, Stewart and Hawton19,Reference Cooper, Kapur and Mackway-Jones41,Reference Ness, Hawton, Bergen, Cooper, Steeg and Kapur50,Reference Geulayov, Kapur, Turnbull, Clements, Waters and Ness51 method of self-harm, Reference Hawton, Bergen, Cooper, Turnbull, Waters and Ness3,Reference Steeg, Kapur, Webb, Applegate, Stewart and Hawton19,Reference Cooper, Kapur and Mackway-Jones41,Reference Ness, Hawton, Bergen, Cooper, Steeg and Kapur50 and age. Reference Cooper, Kapur and Mackway-Jones41,Reference Ness, Hawton, Bergen, Cooper, Steeg and Kapur50,Reference Geulayov, Kapur, Turnbull, Clements, Waters and Ness51 Our recruitment rates are comparable with trials that involve obtaining individual consent from patients who have self-harmed. 6,Reference Kapur, Steeg, Webb, Haigh, Bergen and Hawton28 However, the proportion of the sample with a prior history of self-harm (74.3%) and the repetition rate in our sample within 6 months (30%) was high, Reference Carroll, Metcalfe and Gunnell40 possibly suggesting comparatively high levels of underlying morbidity and need.

The results of our study should be applicable to other psychiatric services with a similar case mix and incidence of repeat self-harm but may not be applicable to people who present to emergency departments and do not receive a psychiatric assessment. Patients who do not receive a psychiatric assessment following self-harm are likely to be younger, unemployed and use self-cutting as a method of self-harm, and have an absence of factors that indicate current mental illness. Reference Kapur, Murphy, Cooper, Bergen, Hawton and Simkin32 Our results may also not be generalisable to people who engage in self-harm but do not present to hospital.

The repetition rate in these groups is likely to be lower, so it may be that the predictive performance of scales will be even worse. Our findings will also not be generalisable to patients who do not wait for assessment, who may be at higher risk than other patients who have self-harmed. Although we had a large sample from geographically dispersed sites this may not be representative of other hospitals in England or internationally. The five centres included in this study have an interest in self-harm management and research, and clinicians working in these sites may not be typical of those practising elsewhere. This could affect the generalisability of the results to other services, perhaps particularly those findings based on clinicians' global risk assessments.

This observational study was designed to mimic how risk scales would be completed in clinical practice. The effect of ordering is likely to be minimal as the items from the scales (Manchester Self-Harm Rule, ReACT Self-Harm Rule, SAD PERSONS scale, Modified SAD PERSONS scale) were extracted from the notes subsequent to the information already gathered from the assessment. Although clinicians were masked to the scoring of the scales and the scale results, their use could have changed patient management. For example, patients deemed at greater risk might have been offered more intensive interventions that may have meant that they were then less likely to repeat self-harm. This could lead to an underestimate of predictive performance – that is, our findings on the risk scales might be unnecessarily pessimistic. We do not think this will have had a major impact on our findings. The availability of suitable interventions following self-harm is poor 6,Reference Hawton, Witt, Taylor Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell and Hazell52 and even if patients receive them, the evidence from randomised trials is that effect sizes are relatively modest. 6,Reference O'Connor, Gaynes, Burda, Soh and Whitlock53

We focused on episodes rather than individuals in order to reflect the clinical reality of fluctuating risk Reference Steeg, Kapur, Webb, Applegate, Stewart and Hawton19 and to be consistent with national guidance that suggests each episode should be treated in its own right. 6 A small number of individuals contributed more than one assessment, which could potentially inflate the repetition rate and diagnostic accuracy statistics. There was a small decrease in the repetition rate for individuals when compared with the episode-based repetition rate (28.2% v. 30%), but this had little impact on our results. The order of the scales in terms of AUC was unchanged. The AUC values themselves were slightly attenuated (clinician global scale: AUC = 0.73; Manchester Self-Harm Rule: AUC = 0.71; patient global scale: AUC = 0.70; ReACT Self-Harm Rule AUC = 0.69, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale AUC = 0.62; Modified SAD PERSONS scale AUC = 0.59; and the SAD PERSONS scale: AUC = 0.56).

Our outcome was repeated self-harm rather than suicide. Suicide is a critically important outcome for research and clinical practice but a challenging area for diagnostic accuracy studies. The low base rate makes prediction difficult and the diagnostic accuracy of scales is generally poor. 6 Future research could examine the performance of risk scales in the prediction of suicide, which may be possible with very large multicentre prospective cohort studies. However, factors associated with future suicide may not be the same as those that are associated with risk of future self-harm. 6

Comparison with previous research

The performance of the scales using a priori cut-off points is consistent with previous research. The Manchester Self-Harm Rule had similar sensitivity (97%) and specificity (20%) to previous validation studies of the Manchester Self-Harm Rule, Reference Steeg, Kapur, Webb, Applegate, Stewart and Hawton19 but lower specificity than in the original study. Reference Cooper, Kapur, Dunning, Guthrie, Appleby and Mackway-Jones17 The ReACT Self-Harm Rule had an equivalent sensitivity (97%) but higher specificity (23%) in this sample than in the original study (97% and 20%, respectively). Reference Steeg, Kapur, Webb, Applegate, Stewart and Hawton19

Using the same cut-off as Randall et al, Reference Randall, Rowe and Colman20 the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale had a lower sensitivity (3% v. 20%) in this sample but similar specificity (98% v. 97%, respectively). The poor performance of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale may be a result of cultural differences as the scale was developed in the USA and may not be directly relevant for a clinical population in the UK; for example, the item ‘I squirm at plays and lectures’ caused queries and some respondents found it difficult to answer. Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Davies, Hawton, Gunnell and Kapur13 The length of the scale (30 items) may also have been an issue. It should also be noted that this scale was not developed as an instrument to predict repeat suicidal behaviour but as a measure of impulsivity, which is just one risk factor for suicidal behaviour. Reference O'Connor and Nock54 The poor performance of the SAD PERSONS scale and Modified SAD PERSONS scale in predicting repeat self-harm is consistent with previous cohort studies. Reference Bolton, Spiwak and Sareen15,Reference Saunders, Brand, Lascelles and Hawton55

Clinical implications

The use of risk scales is dependent on clinical context. Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Davies, Hawton, Gunnell and Kapur13 For example, clinicians may prefer scales with high sensitivity for screening or ruling out a risk of a condition, or scales high in specificity for later stages of assessment or ruling in patients for treatment. Reference Quinlivan, Cooper, Davies, Hawton, Gunnell and Kapur13 However, our findings suggest that risk scales on their own have little role in the management of suicidal behaviour. For example, one of the best performing scales, the Manchester Self-Harm Rule, captured 97 out of every 100 repeat episodes, but incorrectly classified 80/100 of episodes that did not lead to repetition as high risk. Of 100 episodes rated as high risk only 30 resulted in repetition. The scales performed no better (and in some cases significantly worse) than simply asking clinicians or patients what they thought of the future risk. The usefulness of the scales might improve if the cut-off points were tailored to local clinical settings, but the results would then not be generalisable and the cut-offs may not be stable over time.

It was perhaps surprising that the crude global estimates of risk performed comparatively well. On the other hand, clinicians in this study were generally experienced and may have used all the available clinical information and direct observation to come to a more balanced judgement of risk than a score on a simple scale. Of course, it could also be that the clinicians used the scales themselves to inform their overall judgement, but they were not provided with the scoring schedule for the scales and much of the data consisted of items that would be collected as part of routine assessment. These explanations would of course not apply to the patient assessment of risk.

Is there scope for using global estimation of risk scales as a useful part of routine assessments? We think this is unlikely since the positive predictive values for the clinician global scale indicated that for every 100 patients rated as high risk, fewer than half would go on to repeat. Of 100 patients who did not repeat, 36 would be incorrectly classified as at high risk.

Of course, risk scales might be useful in ways other than prediction. For example, to help structure assessments, to ensure crucial items are not missed or as measures of change. Can risk scales do any harm? Some observational evidence suggests that routine aspects of clinical care such as psychosocial assessment and psychiatric admission could contribute to a reduction in risk. Reference Kapur, Steeg, Webb, Haigh, Bergen and Hawton28,Reference Kapur, Steeg, Turnbull, Webb, Bergen and Hawton30,Reference Carroll, Metcalfe, Steeg, Davies, Cooper and Kapur56 Risk scales may have a negative impact on the beneficial aspects of routine psychosocial assessments. 11,Reference Smith, Bouch, Bradstreet, Lakey, Nightingale and O'Connor57 They may be perceived as a negative tokenistic ‘tick box’ exercise by both clinicians and patients and erode the potential to collaboratively evaluate risk of future self-harm and determine appropriate management. Reference Hunter, Chantler, Kapur and Cooper58 At a time of increased service pressures it might even be argued that the use of risk scales to determine patient management actually wastes valuable resources. Reference Bolton, Gunnell and Turecki8

Future research

Consistent with clinical guidelines, our data suggest that risk scales should not be used to determine patient management or risk of future self-harm. 6 One relatively unexplored area is the use of risk assessment as an intervention. In forensic settings, randomised trials of formal risk assessment have had conflicting results. Reference Abderhalden, Needham, Dassen, Halfens, Haug and Fischer59,Reference Troquete, van den Brink, Beintema, Mulder, van Os and Schoevers60 Randomised controlled trials could test the impact of using risk scales v. assessment as usual on patient management and repeat self-harm, including adverse events and cost-effectiveness. We are currently undertaking health economic modelling work that will provide an indication of how good risk tools might need to be in terms of predictive ability in order to be cost-effective.

Given the poor performance of scales, it is possible that the scales may be missing important aspects relevant to repeat suicidal behaviour (for example social, cultural, economic or psychological processes). Reference Carroll, Metcalfe, Steeg, Davies, Cooper and Kapur56,Reference Coope, Donovan, Wilson, Barnes, Metcalfe and Hollingworth61,Reference Haw, Hawton, Gunnell and Platt62 Future research should include patients in the development of appropriate measures and assessments and could also consider suicide as an outcome. It is likely that the predictive ability of assessment varies according to clinician factors (such as level of experience, professional background), patient factors (history of suicidal behaviour or psychiatric treatment), and assessment factors (received a psychiatric assessment or did not wait for assessment), and these could also be investigated. Studies might examine the role of global clinician and patient assessments of risk, with a focus on their predictive performance but also an examination of the factors that contribute to these complex judgements.

Funding

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (Grant Reference Number ). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. K.H. and D.G. are NIHR Senior Investigators. K.H. is also supported by the Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust and N.K. by the Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rosie Davies at the University of Bristol and our other patient, carer, and clinician advisors for their input into the study. We would also like to thank the Research and Development departments for hosting the research and the NIHR Clinical Research Network staff who helped set up the study and assisted with local recruitment and monitoring. We are grateful to the staff from the mental health liaison teams at each site who collected the data and the patients for completing the assessments.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.