Depression is a prevalent mental condition across the globe and a main contributor to the global burden of disease. Reference Murray, Vos, Lozano, Naghavi, Flaxman and Michaud1 Although the risk factors for depression are well described, less is known about factors that enable individuals to bounce back from depression or even to avoid it altogether. Reference Patel and Goodman2 Social support is hypothesised to protect mental health both directly through the benefits of social relationships and indirectly as a buffer against stressful circumstances. Social support is a multidimensional concept which broadly refers to the emotional (e.g. providing encouragement), instrumental (e.g. helping with housekeeping) or informational (e.g. notifying someone of a job opportunity) assistance that is received from others. Reference House, Umberson and Landis3 It may also be characterised by the provider of support, including support from a spouse, relatives or friends, each thought to have independent protective effects against depression. Several reviewers have discussed aspects of social factors and mood problems in adult and elderly populations. Reference O'Connell and Mayo4–Reference Bruce8 Previous reviews have been mostly narrative, however, and none focused specifically on depression. In spite of the wealth of literature on social support, several questions remain. It is not clear which sources or types of social support are most protective against depression, or whether the type and source of support that is optimal for mental health varies across the life course. For example, parental support may be more important during childhood than adulthood. Answers to these questions may be useful for both policy-makers and clinicians in crafting targeted messages and interventions on social support, and to orient future research in this area. The aim of this paper was therefore to conduct a systematic literature review to summarise existing knowledge on social support and protection from depression. We explored evidence for different types of social support and summarised findings according to broad life periods (childhood and adolescence, adulthood, older adulthood).

Method

We conducted a systematic search in February 2015 to identify relevant studies in the following databases: PubMed Medline, ISI Web of Science and PsycINFO. No limits were set on publication dates. Database-specific electronic search terms were developed in consultation with a librarian and included the following terms and their variants: social support, social network, social capital, social isolation, social contacts, social integration; depression, depressive symptoms. The PubMed search strategy (including MeSH terms) is given as an example in online supplement DS1. We further searched reference lists of primary studies and review articles to identify any additional eligible studies.

Study selection

We considered eligible any observational study from the general population, across any life period, that assessed the association between social support (independent variable) and depression or depressive symptoms (dependent variable). Papers were included if they were original publications based on individual-level data and provided a quantitative measure of association (risk ratio, odds ratio, etc.). We reported estimates from the fully adjusted model wherever available. Since we were interested in the inverse relationship between social support and depression in the general population, we excluded studies on specific subpopulations. Furthermore, since this association is likely to be culture-dependent, Reference De Silva, Huttly, Harpham and Kenward9 we also limited this review to Western countries, including the USA, Canada and Europe (EU and member states of the European Free Trade Association), Australia and New Zealand. We reviewed only publications that were in English, French or Finnish. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two investigators (G.G. and H.H.) and disagreements were resolved by consensus or a third reviewer (A.Q.-V.). Interrater agreement was calculated using the agreement rate, simple kappa score and kappa score adjusted for prevalence and bias. We reported the last because the simple kappa score is sensitive to the proportion of studies eligible, which was low in this review (0.6%). Reference Byrt, Bishop and Carlin10

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction and quality assessment of eligible studies were performed independently by two investigators (G.G. and H.H.). For each study we extracted study information, instruments used to assess social support and depression, and association estimates. The authors were contacted for additional information when necessary. We conducted a quality assessment of the studies using a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. Reference Wells, Shea, O'Connell, Peterson, Welch and Losos11 The modified scale includes nine items about comparability, selection bias, information bias and control of at least three important confounders (see online supplement DS2 for items and rating criteria). Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third party (A.Q.-V.). We analysed studies by life periods (children and adolescents, adults and older adults) and study design (cross-sectional, cohort or case–control). Adult studies included samples restricted to adults and those from the general population mainly composed of adults.

Statistical analysis

We used meta-analytic methods to provide a general quantitative synthesis of the literature. Pooled results should be interpreted with caution because of the known high level of heterogeneity between studies. We included studies for which standard errors could be extracted or calculated (62 studies). We conducted separate analyses for dichotomous and continuous depression outcomes since they provide different effect estimates. We used odds ratios for dichotomous outcomes and standardised beta coefficients for continuous outcomes. We pooled estimates using the DerSimonian & Laird random effects model. For studies that presented associations across categorical levels of social support (rather than linear scales) we included estimates comparing the highest and lowest level of support. For studies that provided results categorised by subgroups (e.g. gender) we combined results using a fixed effects model and included the pooled result in the analysis. We reverse-coded associations between absence of (or negative) social support, such that all estimates described the associations between presence of (or positive) social support and depressive symptoms or depression. High heterogeneity between studies was expected and evaluated descriptively by life period, broad categories of social support (general support; support from partner, from family, from friends and from work or school; emotional, instrumental and informational support) and type of study design. Publication bias was not assessed using quantitative methods because these are not recommended under conditions of high heterogeneity. Reference Almeida, Subramanian, Kawachi and Molnar12 Analyses were conducted in Stata version 12.1.

Results

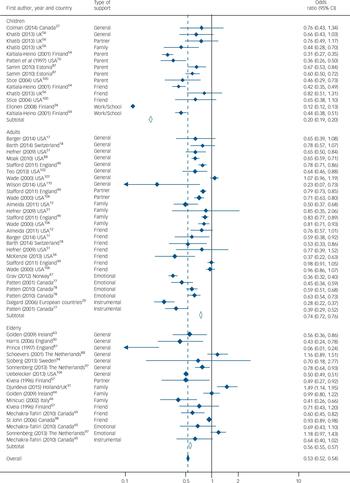

The final selection comprised 99 articles, of which one presented results from two studies, resulting in a total of 100 studies (Fig. 1). Reference Almeida, Subramanian, Kawachi and Molnar12–Reference Zunzunegui, Beland and Otero111 About two-thirds of studies were cross-sectional, a third longitudinal and none case–control (Table 1). These studies represent data from 504 966 individuals (sample sizes ranged from 83 to 95 103) and covered 27 years of published research (1988–2015). The majority of studies were from the USA (55 studies); the remainder were from Europe (33 studies), Canada (11 studies) and Australia (1 study). Interrater agreement for study screening was adequate (98%, κ = 0.41, adjusted κ = 0.97). Forest plots for the studies included in the quantitative analysis are shown in Figs 2 and 3. Online Table DS1 presents an overview of the social support and depression measures used in the research.

Fig. 1 Study selection.

Fig. 2 Forest plot of studies using a dichotomous depression outcome, categorised by life period.

Fig. 3 Forest plot of studies using a continuous depression outcome, categorised by life period.

Table 1 Studies reporting a significant association between social support and protection from depression, categorised by life period

| Children and adolescents a |

Adults and general population a |

Older adults a | All a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 84% (26/31) | 92% (33/36) | 94% (31/33) | 90% (90/100) |

| Study design | ||||

| Cross-sectional | 83% (15/18) | 89% (25/28) | 100% (23/23) | 91% (63/69) |

| Cohort | 77% (10/13) | 100% (8/8) | 80% (8/10) | 84% (26/31) |

| Study quality | ||||

| Low | 100% (5/5) | 100% (4/4) | 0% (0/1) | 90% (9/10) |

| Moderate | 80% (16/20) | 89% (24/27) | 96% (25/26) | 89% (65/73) |

| High | 67% (4/6) | 100% (5/5) | 100% (6/6) | 88% (15/17) |

| Gender | ||||

| Women | 100% (11/11) | 86% (6/7) | 71% (5/7) | 88% (22/25) |

| Men | 73% (8/11) | 80% (4/5) | 100% (6/6) | 82% (18/22) |

| Aspect of social support | ||||

| General perceived support | 33% (1/3) | 78% (14/18) | 83% (15/18) | 77% (30/39) |

| Source of social support | ||||

| Support from spouse | 100% (9/9) | 100% (6/6) | 100% (15/15) | |

| Support from family | 86% (6/7) | 88% (7/8) | 36% (4/11) | 65% (17/26) |

| Support from parents | 80% (12/15) | 80% (12/15) | ||

| Support from children | 67% (2/3) | 50% (3/6) | 56% (5/9) | |

| Support from friends | 56% (9/16) | 73% (8/11) | 71% (5/7) | 65% (22/34) |

| Support from teacher | 86% (6/7) | 86% (6/7) | ||

| Support from work | 100% (1/1) | 100% (1/1) | ||

| Type of social support | ||||

| Emotional support | 86% (6/7) | 50% (2/4) | 73% (8/11) | |

| Instrumental support | 67% (6/9) | 50% (2/4) | 62% (8/13) | |

| Informational support | 100% (1/1) | 100% (1/1) | ||

a. Proportion of studies with significant results; number of studies with significant results/total number of studies in parenthesis.

Children and adolescents

The search identified 31 studies that assessed social support and protection from depression in children and adolescents, ranging in age from 8 to 20 years (see online Tables DS2 and DS3 for study characteristics and details of ratings respectively). A significant association between at least one aspect of social support and protection from depression was reported in 84% of studies (Table 1). Evidence suggested a strong association between social support and absence of depression (pooled OR = 0.20, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.20). Odds ratios ranged from 0.12 to 0.82 (see Fig. 2). Findings from studies that used continuous depression scores were less consistent (pooled beta coefficient −0.06, 95% CI −0.09 to −0.03). Beta coefficients ranged from −1.73 to 0.06 (see Fig. 3). Estimates were generally stronger and more likely to be significant in cross-sectional studies than in cohort studies, and in low- or moderate-quality studies than in high-quality studies (Table 1). Removing low-quality studies from the meta-analysis did not affect pooled estimates. In studies that reported gender-specific estimates a significant association was found consistently for girls (all of 11 studies found a significant association) but not for boys (8 of 11 studies). Parents, teachers and family were sources of support most consistently found to be protective against depression in children and adolescents (80%, 86% and 86% of studies reported a significant association for each type of support respectively), whereas findings were less consistent for support from friends and general perceived support (56% and 33% of studies with significant findings respectively) (Table 1). In additional analysis we found that parental and family support was particularly important for girls (80% of studies reported a significant association) but less so for boys (40% of studies reported a significant association). No study on type of social support (emotional, instrumental, informational) in youth was found in this review. Measurement tools to assess social support varied broadly, with each of the 31 studies using a unique scale, of which less than half were validated (online Table DS1).

Adults

A total of 36 studies measured the association between social support and protection from depression in samples of adults (see online Tables DS4 and DS5 for study characteristics and details of ratings respectively). Ages ranged from 18 years and older, except for one study which included a general population sample of Germans aged 16 years and older, Reference Grumer and Pinquart48 and another of Canadians aged 12 years and older. Reference Patten, Williams, Lavorato and Bulloch78 A majority of studies (89%) reported a significant association between social support and protection from depression among adults. In studies that used binary depression outcomes (pooled OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.76) odds ratios ranged between 0.23 and 1.07 (see Fig. 2). In studies that used continuous depression scores (pooled beta coefficient −0.01, 95% CI −0.02 to −0.01) beta coefficients ranged between −4.90 and 0.21 (see Fig. 3). In studies that conducted gender-specific analyses findings were similarly significant in samples of women (86%) and men (80%) (Table 1). The numbers of statistically significant findings were also similar in cross-sectional and cohort studies and across studies of low, moderate and high quality. Excluding low-quality studies from the meta-analysis did not substantially change pooled estimates.

The source of social support most consistently associated with protection from depression in adults was spousal support (100% of studies reported a significant association) followed by support from family (88% of studies), friends (73% of studies) and children (67% of studies). The type of social support most consistently associated with protection from depression in adults was emotional support (75% of studies reported a significant association) followed by instrumental support (67% of studies); informational support was examined in one study and was not found to be significantly associated with protection from depression (Table 1). Each study used a unique instrument to measure social support, except for the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List, which was used in three studies (online Table DS1). About a third of studies used a previously validated social support scale.

Older adults

The search identified 33 studies examining social support and protection from depression specifically in samples of adults aged 50 years and older (see online Tables DS6 and DS7 for study characteristics and details of ratings respectively). Over 90% of studies found a significant association between some aspect of social support and protection from depression in older adults. In studies that modelled binary depression outcomes (pooled OR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.57), odds ratios ranged from 0.06 to 1.49 (see Fig. 2). In studies modelling continuous depression outcomes (pooled beta coefficient −0.11, 95% CI −0.13 to −0.08), beta coefficients ranged from −4.23 to 0.66 (see Fig. 3). Results were consistently significant in men (all of 6 studies found a significant association) but less so in women (5 of 7 studies). Cross-sectional studies found significant results more often than cohort studies (Table 1). Study quality did not affect consistency of significant results and removing low-quality studies did not affect pooled estimates. As in the adult studies, spouses were the source of social support most consistently associated with protection from depression (all studies), followed by support from friends (83% of studies) (Table 1). Evidence for support from children and family was less consistent (50% and 36% of studies respectively reported a significant association). Evidence for emotional support and instrumental support relating to protection from depression was supported in half the studies. Each study used a unique social support measurement tool, of which only about a third were validated (online supplement DS1).

Discussion

This study provides the most comprehensive systematic literature review to date on the association between social support and protection from depression. Further, it is the first to contrast evidence for this association across life periods and provide meta-analytic estimates of association within each of these periods. We identified 100 studies that reported on aspects of social support and protection from depression across all ages. Evidence is overall highly consistent and supports the notion that social support is an important protective factor against depression. However, the sources of social support that were most protective of depression varied across the life periods. Parental support was most consistently associated with protection from depression in children and adolescents, whereas spousal support was most salient for adults and older adults. Furthermore, the review identified large variations in the operationalisation and measurement of social support. Over ten different aspects of social support were investigated in the literature, measured with close to a hundred different measurement tools. Finally, an important limitation of this body of evidence is that most studies were cross-sectional, thus precluding inference of the direction of association between social support and protection from depression. This caveat is particularly salient for studies of children and adolescents, in which the cross-sectional estimates were larger and more significant than those of the cohort studies, suggesting that reverse causality (i.e. a perception of greater support among the least depressed) might be inflating estimates in the former set of studies.

Children and adolescents

Support from parents and family is most consistently related to a youth's protection from depression, more than any other source. Children and adolescents rely on their parents to meet their basic needs, such as emotional assistance and material resources. Parental support has been shown to affect a child's mental health development, Reference Boudreault-Bouchard, Dion, Hains, Vandermeerschen, Laberge and Perron113,Reference Holahan, Valentiner and Moos114 which in turn may contribute to protection from depression. In this review, parental support was particularly important for girls. This effect may be attributable to gender-specific parent–child dyads. Reference Ex and Janssens115 Among the three studies that investigated maternal and paternal support independently from each other, all studies reported maternal support to be a significant protective factor from depression in girls, but only one study reported this for boys, and only in the context of single-mother households. Reference Patten, Gillin, Farkas, Gilpin, Berry and Pierce76 These findings are supported by others that suggest maternal support is a particularly important component of development and mental well-being in girls. Reference Carlson116 Conversely, paternal support was associated with protection from depression in two-thirds of studies, equally for girls and boys. Others have demonstrated the importance of paternal involvement on child behaviours and outcomes. Reference Carlson116 Interestingly – and perhaps contrary to popular belief that views peer support as a substitute for parental support (particularly in adolescence) – social support from friends was not consistently associated with protection from depression in samples of children and adolescents. Peer support has been shown to be important in the psychological development of children. However, friendships during adolescence are more transitory and may be less reliable sources of support than parents and family. Reference Branje, Frijns, Finkenauer, Engels and Meeus117 Furthermore, cross-sectional studies do not permit assessment of the possibility that depression might also adversely affect the capacity to develop friendships in these crucial formative years. Reference Kennedy, Spence and Hensley118

Adults

In samples of adults evidence is strongest for spousal support as a protective factor against depression. Evidence also suggests that both social support (e.g. empathy) and social strain (e.g. criticism) from a spouse are significantly related to depressive symptoms in adults, although in opposite directions, Reference Okun and Keith70,Reference Simon and Barrett93,Reference Stafford, McMunn, Zaninotto and Nazroo119 and both giving and receiving support from a spouse is associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms. Reference Biehle and Mickelson19 Evidence was also highly consistent for family support as a protective factor against depression in adults, but was mixed for friend support. Adulthood is a time when family responsibilities are greatest and a main source of stress. In this context, spousal and family support to assist with parental obligations may be particularly important to mental health. Reference Pettit, Roberts, Lewinsohn, Seeley and Yaroslavsky120 In addition, as the composition of networks tends to shift across adulthood to include more family members than friends, family may therefore represent a more available source of support. Reference Walen and Lachman121

Emotional support is a highly consistent protective factor against depression in adults compared with instrumental support. Emotional support, such as having someone to confide in, attempts to directly reduce the negative emotions associated with a distressing situation, Reference Thoits122 whereas instrumental support such as having someone to help with chores or in case of a crisis may benefit mental health more indirectly, by providing respite from chronic and acute stress. Alternatively, given the dearth of longitudinal studies, these results could be indicative of reverse causality, whereby emotional support is mostly activated in situations of greater need, and thus could be spuriously found to be associated with greater distress and depression. Reference Seeman123 Emotional support could also be more easily provided, particularly when the provider and recipient are geographically distant, as instrumental support often requires a physical presence.

Older adults

In elderly samples spousal support is a consistent protective factor against depression, particularly in men. Results from two longitudinal studies suggest that having a poor relationship with a spouse, Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpela, Rantanen and Laippala54 or having no partner in the household, Reference Sonnenberg, Deeg, van Tilburg, Vink, Stek and Beekman97 were associated with depression in older men. This evidence supports established evidence that spousal support may be particularly important for the health of men. Reference Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton124 Cross-sectional evidence, however, shows spousal support to be significant for both genders. Reference Choi and Ha24 Unlike earlier life periods, evidence for a protective effect of family support was weak among older adults. Only a third of studies that examined family support reported a significant association. The role of family and relatives may change with older age, as relatives are also ageing (or may die) and may become less able to offer support. The type of social support that older individuals need from their family for mental health could also be different from that for younger adults. For example, Minicuci et al found that poor financial support from family members was associated with depression in older men, but poor emotional support was not. Reference Minicuci, Maggi, Pavan, Enzi and Crepaldi66 Further research on the type of social support that is relevant to prevent depression in older age is needed.

Across the different life periods support from friends was most consistently associated with protection from depression in older adults. Support from friends could be an adjunct to support from spouse and family. It is possible that friendship and companionship become more important with older age as spouses and family become less available due to illness and death. Reference Gupta and Korte125 This pattern of evidence is supported by studies that stratified their sample by age group. Fiori et al found that positive support from friends was significantly associated with less depressive symptoms in older adults (age 60+ years), but not in younger adults (35–59 years old). Reference Fiori, McIlvane, Brown and Antonucci37 Similarly, Okun & Keith found that support from friends and/or relatives (other than spouse or children) was significantly and strongly related to less depressive symptoms in older adults (60–92 years old) but not in younger adults (28–59 years old). Reference Okun and Keith70

Children could be an additional source of support against depression in older adults, yet evidence for this is weak and mixed. Only half of the studies investigating support from children found a significant association. However, support from children was measured in a variety of ways, such as getting help from children, receiving expressive or emotional support, or number of children seen weekly. The exact role of social support from children for their older parents is therefore not clear. Children may provide important instrumental support or companionship to their parents, but evidence for these types of support is absent. In addition, reverse causality may apply here as well, as children may come to be involved in providing support with increasing loss of autonomy, which is typically associated with increased risk of depression. Reference Cole and Dendukuri126

Limitations of the studies

Social support measurement

An important finding of this review is the large number of instruments researchers used to measure and operationalise social support, which limits the replication of findings. General perceived social support (e.g. ‘Do you have someone you can really count on to help you out in a crisis situation?’) was the most common measure of social support. Yet this measure does not fully capture the range of social support available to individuals, which may vary between individuals and over the life course. Additionally, perceived general social support may not be a reliable measure in children, who may not have the life experience or self-reflection to make a general assessment of their personal level of social support. Less than half of studies in the literature used a validated social support instrument. Scales that have not been validated may not accurately measure social support or might capture elements of life beyond social support, such as physical health, personality traits (e.g. extroversion) and living arrangement (e.g. living alone). Reference Rascle, Bruchon-Schweitzer and Sarason127,Reference Holden, Lee, Hockey, Ware and Dobson128 The concept of time in social support measurement has also been largely ignored up to now. Except for one study, Reference Dean, Kolody and Wood30 none of the scales used a time frame when assessing social support. Consequently, perception of social support may refer to various time periods depending on the individual, and may include future expectation of support. Social support may further change over time in response to life events, yet the majority of longitudinal studies examined social support at a single point in time. There may be a reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and social support, as social withdrawal may drive away social ties. There is also a dearth of evidence on the protective effects of social support against depression across the life course. In the only life course study to date, authors found that parental support during childhood decreased depressive symptoms in adulthood. Reference Shaw, Krause, Chatters, Connell and Ingersoll-Dayton90 Further high-quality longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these results.

Depression measurement

Depressive symptoms were generally measured from self-report screening depression scales. Although the majority of scales are validated instruments, they are screening tools and not clinical interviews, and may therefore overestimate the presence of mood problems. The time frame of reference for depressive symptoms ranged from current symptoms to lifetime depression. The strength of associations tended to be greater in studies that measured current or past-week depressive symptoms than in studies that used longer time frames. Current depressive symptoms might be more strongly associated with perceived social support because being depressed may affect the perception of social support. A shorter time frame might also rely less on recall and provide a more reliable assessment of depressive problems.

Limitations of our review

As with any review, publication bias is possible. Publishers and authors tend to favour the publication of significant findings over non-significant ones. We were only able to review papers in English, French and Finnish, potentially missing some studies. Nevertheless, we only found English studies to fit our criteria. We included only studies from Western countries; results may therefore have limited generalisability to other geographical areas, particularly low-income countries and/or other cultural contexts. Future research focusing on other cultures and countries is recommended. We restricted our search to samples from the general population. The association between social support and protection from depression may differ in vulnerable subgroups.

Strengths of the review

We used a rigorous methodology to search and assess the published research on the inverse association between social support and depression. Two reviewers independently examined the evidence. We favoured an in-depth analysis of the literature to explain current findings and trends, complemented by a meta-analysis to summarise findings. We carefully sought to assess the association between social support and protection from depression overall and across life periods, a topic that has not been specifically reviewed in the literature.

Future research

Our review provides consistent evidence of an association between social support and protection from depression in samples of the general population across all ages. Sources of support tended to vary in importance across life periods, with parental support being most consistently associated with protection from depression in children and adolescents, and spousal support in adults and older adults. Significant heterogeneity in social support measurement is a key finding of this review. Future studies using validated social support scales are recommended. As the contrast in magnitude and significance of effects between cohort and cross-sectional studies suggests the presence of reverse causation in these associations, research on the temporal dynamics of social support and protection from depression, particularly over the life course, is also strongly encouraged.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Operating Grant MIN127270, PI: Quesnel-Vallée). G.G. was supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; A.Q.V. was supported by a salary award from Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec and holds the Canada Research Chair on Policies and Health Inequalities.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.