17β-oestradiol, progesterone and testosterone are potent neurosteroids with both neuro- and psychoprotective effects. Reference Barth, Villringer and Sacher1–Reference Siddiqui, Siddiqui, Khan, Kalam, Jabir and Kamal3 Fluctuating and declining hormone levels during peri- and early menopause are associated with mood symptoms, including low mood, anxiety and irritability, in between 10 and 65% of women. Reference Freeman4,Reference Maki, Kornstein, Joffe, Bromberger, Freeman and Athappilly5 In a recent analysis using data from the UK Biobank (N = 128 294), the risk of first-onset mental disorder was increased 1.52-fold in perimenopausal women compared with pre- and postmenopausal women (major depressive episode: relative risk 1.30, 95% CI 1.16–1.45; mania: relative risk 2.12, 95% CI 1.30–3.52). Reference Dolman and Shitomi-Jones6 Although perimenopause was not associated with an increased risk of new-onset schizophrenia, previous studies have demonstrated that pre-existing mental illness may worsen in perimenopause and, while younger women with schizophrenia are at lower risk of relapse, peri- and postmenopausal women are at higher risk of hospital admission for psychosis compared with age-matched men. Reference Perich, Ussher and Meade7,Reference Sommer, Brand, Gangadin, Tanskanen, Tiihonen and Taipale8 Menopausal negative mood symptoms have a detrimental impact on women’s personal and professional lives, Reference Dibonaventura, Wagner, Alvir and Whiteley9 and may contribute to higher suicide rates in midlife. 10–12

Justification for the current study

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) effectively relieves menopausal symptoms and has osteo-, cardio- and neuroprotective effects. Reference Levy and Simon13–Reference Piette15 For most women with bothersome symptoms, the potential benefits of MHT are many and the risks are few when initiated within 10 years of menopause. Reference Baber, Panay and Fenton16,17 MHT is not currently licensed to treat menopausal depression and anxiety, because randomised clinical trial (RCT) data supporting its use in this context are limited and conflicting. Reference Toffol, Heikinheimo and Partonen18 However, guidelines recommend that MHT be ‘considered’ for the relief of menopausal mood symptoms because, overall, the available evidence supports a beneficial effect. Reference Baber, Panay and Fenton16,17,Reference Hamoda, Panay, Pedder, Arya and Savvas19,20 Nevertheless, around a third of women who consult their doctor are instead offered antidepressants, Reference Glynne, Reisel, Lewis and Newson21 despite no clear evidence of benefit in this patient population 20 and the associated risks. Reference Edinoff, Akuly, Hanna, Ochoa, Patti and Ghaffar22–25

Data concerning the impact of MHT on menopausal mood symptoms are mainly derived from studies in which women were treated with synthetic hormones alien to the female body. Reference Toffol, Heikinheimo and Partonen18 Women were commonly prescribed conjugated equine oestrogen (CEE), either alone or in combination with a synthetic progestin, usually medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). CEE is extracted from pregnant mare’s urine and contains at least ten different equine and human oestrogens in their sulphate ester form. The content of 17β-oestradiol, the most potent natural oestrogen in humans, is only about 1%. Reference Ruan and Mueck26 The various oestrogenic compounds have different binding affinities for human oestrogen receptors and exert a range of pharmacodynamic effects. Similarly, synthetic progestins each have unique pharmacodynamic activity and do not share a class effect with progesterone, the primary progestogenic hormone synthesised in the ovaries of premenopausal women. Reference Piette15,Reference Ruan and Mueck26

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of body-identical MHT on negative mood symptoms in a real-world cohort of peri- and postmenopausal women. Women using the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) were also included. Levonorgestrel is a synthetic progestin but, compared with oral progestins, systemic absorption and the risk of side effects are lower. Reference Panay and Studd27 We hypothesised that the use of transdermal 17β-oestradiol ± micronised progesterone or the LNG-IUS, with or without transdermal testosterone, would have a beneficial effect on menopausal mood symptoms (reduction in symptom frequency and severity).

Method

Study design

This was a single-centre, UK-based, retrospective cohort study. The Newson Health Clinic in Stratford-upon-Avon is the largest specialist menopause clinic in the UK, conducting more than 3000 consultations every month. All patient data are recorded and stored in a secure, web-based clinic management system (Semble Ltd, UK 28 ). This has created a unique, large, electronic data-set that is used for clinical research and audit purposes.

Inclusion criteria

All peri- and postmenopausal women attending the clinic between 5 September 2023 and 5 April 2024 were included if they: (a) initiated MHT (‘MHT-naïve’) or were already using MHT and attended to have their MHT dose and/or regimen optimised (‘MHT users’); (b) used only body-identical MHT formulations or the LNG-IUS; (c) attended the clinic twice during the study period – an initial consultation followed by a review consultation, usually 3 months later; (d) completed the Meno-D symptom questionnaire at both baseline and follow-up; and (e) provided written informed consent for their data to be used in clinical research.

Perimenopause was diagnosed if women had typical menopausal symptoms Reference Greene29 but were still menstruating, or less than 12 months had elapsed since their last menstrual period (LMP). Menopause was diagnosed if more than 12 months had elapsed since the LMP in women with a uterus, or following hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy (‘surgical menopause’). Amenorrhoeic women who had retained their ovaries after hysterectomy, or with the LNG-IUS, were defined as menopausal if over the age of 55 years, or ‘unsure of menopausal status’ if <55 years.

Women were categorised as ’MHT-naïve’ if they were not using MHT at baseline and had initiated MHT during the study period. Women were categorised as ‘MHT users’ if they were already using MHT at baseline but had persistent symptoms and attended Newson Health to have their MHT regimen optimised – this usually entailed an increase in oestradiol dose or change in formulation to overcome poor transdermal absorption and/or the addition of testosterone. At first presentation, women using the LNG-IUS only (to treat menorrhagia or for contraceptive purposes) were categorised as MHT-naïve; women using the LNG-IUS in combination with oestrogen replacement therapy were categorised as MHT users.

All women received transdermal 17β-oestradiol (E2 patch, gel or spray) with or without a progestogen (P) – body-identical progesterone (P4) or the LNG-IUS, and/or transdermal testosterone (10 mg/mL testosterone cream, usual starting dose 0.5 ml daily; or 40.5 mg testosterone/2.5 mL gel, usual starting dose 1/8 sachet daily). Dosage was individualised in keeping with menopause guidelines that recommend dose customisation to account for differences in pharmacokinetics (absorption, metabolism and clearance) and pharmacodynamics (tissue sensitivity). Reference Baber, Panay and Fenton16,17,Reference Hamoda, Panay, Pedder, Arya and Savvas19

Meno-D is a validated 12-item questionnaire designed to measure and rate the severity of 12 menopausal mood symptoms: energy, paranoia, irritability, self-esteem, isolation, anxiety, somatic symptoms, sleep, weight, sexual interest, memory and concentration. Reference Kulkarni, Gavrilidis, Hudaib, Bleeker, Worsley and Gurvich30 Patients rate the severity of each symptom using a five-point Likert scale, from 0 (asymptomatic) to 4 (severe symptoms); total score range is 0–48.

Characteristics of the study population, including age, menopausal status, MHT regimen (type, formulation), antidepressant use and Meno-D scores, were extracted from the medical records.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was change in global Meno-D score from baseline to first follow-up appointment. Secondary outcomes were change in Meno-D scores stratified by menopausal status (peri- versus postmenopause); concurrent antidepressant use (antidepressant-naïve versus non-naïve); MHT regimen (E2-only versus combined MHT, where combined MHT refers to E2 + P4 or E2 + LNG-IUS, ± transdermal testosterone); progestogen type (P4 versus LNG-IUS); and MHT treatment strategy: (a) women who initiated MHT – ‘MHT-naïve’ versus those already using MHT who attended to have their dose and/or regimen optimised – ‘MHT users’; (b) MHT-naïve women initiated on E2 ± P versus E2 ± P + transdermal testosterone; and (c) MHT users who received a higher E2 dose/change in formulation versus the addition of transdermal testosterone versus both a higher E2 dose/change in formulation and transdermal testosterone. It was not possible to compare other MHT treatment strategies because subgroup sizes were too small. Change in individual symptom scores was also analysed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R 4.3.1. Counts and percentages were used to summarise categorical data. Mean (s.d.) and median (interquartile range, IQR) were used to summarise continuous normal and non-normal variables, respectively. Mean percentage change in Meno-D score and 95% CI was calculated for the whole cohort and for each subgroup. A paired t-test was used to compare mean global and subgroup Meno-D scores at baseline versus follow-up. Linear models were applied to each subgroup comparison to test for differences in mean percentage change in Meno-D score stratified by secondary outcome (for example, to compare mean percentage change in Meno-D score in peri- versus postmenopausal women). For individual symptom scores, a chi-squared test of association was applied to the frequencies of patients who selected each Meno-D score at baseline and follow-up. Hypothesis testing was performed at the 5% level.

Ethics and consent statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2013. All procedures involving patients were approved by the University College of London Research Ethics Committee (UCL REC ID: 9093.008).

Results

Patient demographics

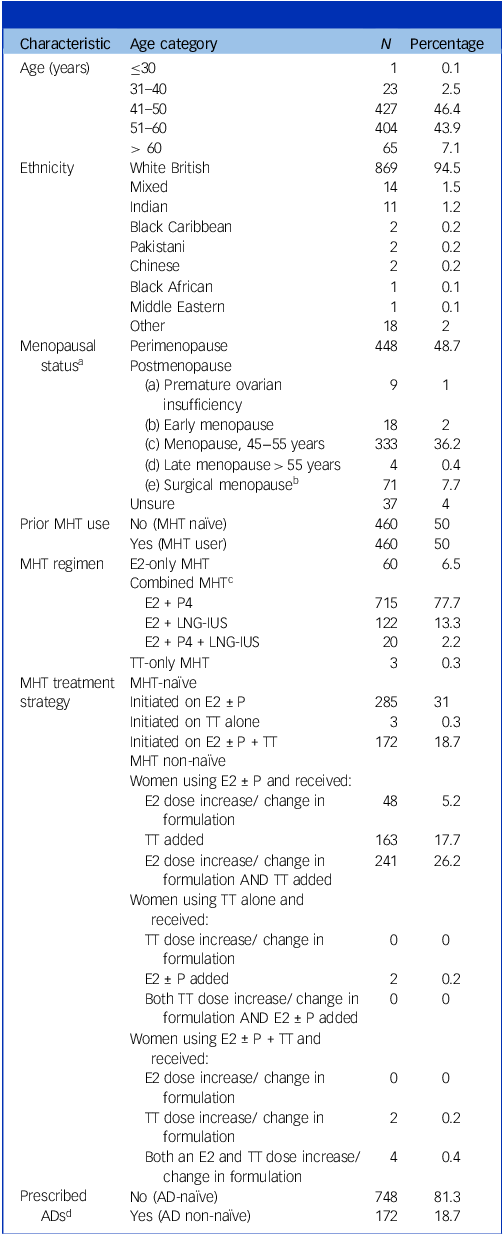

In total, 920 women were eligible for inclusion in the study cohort. Patient demographics are presented in Table 1. Most clinic attendees were White British (n = 869, 94.5%) and aged 41–60 years (n = 831, 90.3%); 448 women (48.7%) were perimenopausal, 435 (47.3%) were postmenopausal and 37 (4.0%) were unsure of their menopausal status. Half the cohort (n = 460, 50.0%) were MHT-naïve at the time of their initial consultation; half (n = 460, 50.0%) were already using MHT and attended to have their dose/regimen optimised. Most women (n = 857, 93.2%) used combined MHT – E2 combined with P4 (n = 715, 77.7%) or the LNG-IUS (n = 122, 13.3%). Twenty women (2.2%) used both the LNG-IUS (for endometrial protection and/or contraception) and P4 (for beneficial effects on mood and sleep). All women using the LNG-IUS used the Mirena® coil, which contains 52 mg levonorgestrel; three women (0.3%) received transdermal testosterone monotherapy.

Table 1 Patient demographics

E2, 17β-oestradiol; P, progestogen; P4, body-identical progesterone; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine system; TT, transdermal testosterone; AD, antidepressant; MHT, menopausal hormone therapy.

a. Women were categorised as perimenopausal if they presented with menopausal symptoms while still menstruating, or within 12 months of their last menstrual period (LMP); women were categorised as postmenopausal if ≥12 months since their LMP. Some women, such as those hysterectomised or using an LNG-IUS, were unsure of their menopausal status.

b. Twenty-three women were <40 years of age, 26 were aged 40–45 and 20 were aged 45–55 at the time of surgery. Age at surgical menopause was unknown for two women.

c. All women using the LNG-IUS were using the Mirena® coil, which contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel.

d. Women prescribed antidepressants at baseline (time of initial consultation); 85 of 172 AD users (49.4%) were MHT-naïve at baseline (MHT initiated); 87 of 172 AD users (50.6%) were already using MHT and attended to have their dose and/or regimen optimised.

Concerning participants’ psychiatric history, 281 women (30.54%) reported a current or past history of depression and 17 (1.85%) reported a history of severe mental illness (unspecified). Two hundred and twenty women (23.91%) reported a history of premenstrual syndrome, 13 (1.41%) reported a history of premenstrual dysphoric disorder and 77 (8.37%) reported a history of postnatal depression; 172 women (18.7%) were using antidepressants at baseline.

The mean time from initial consultation to the first review appointment was 107 days (s.d. 21 days, range 21–201 days).

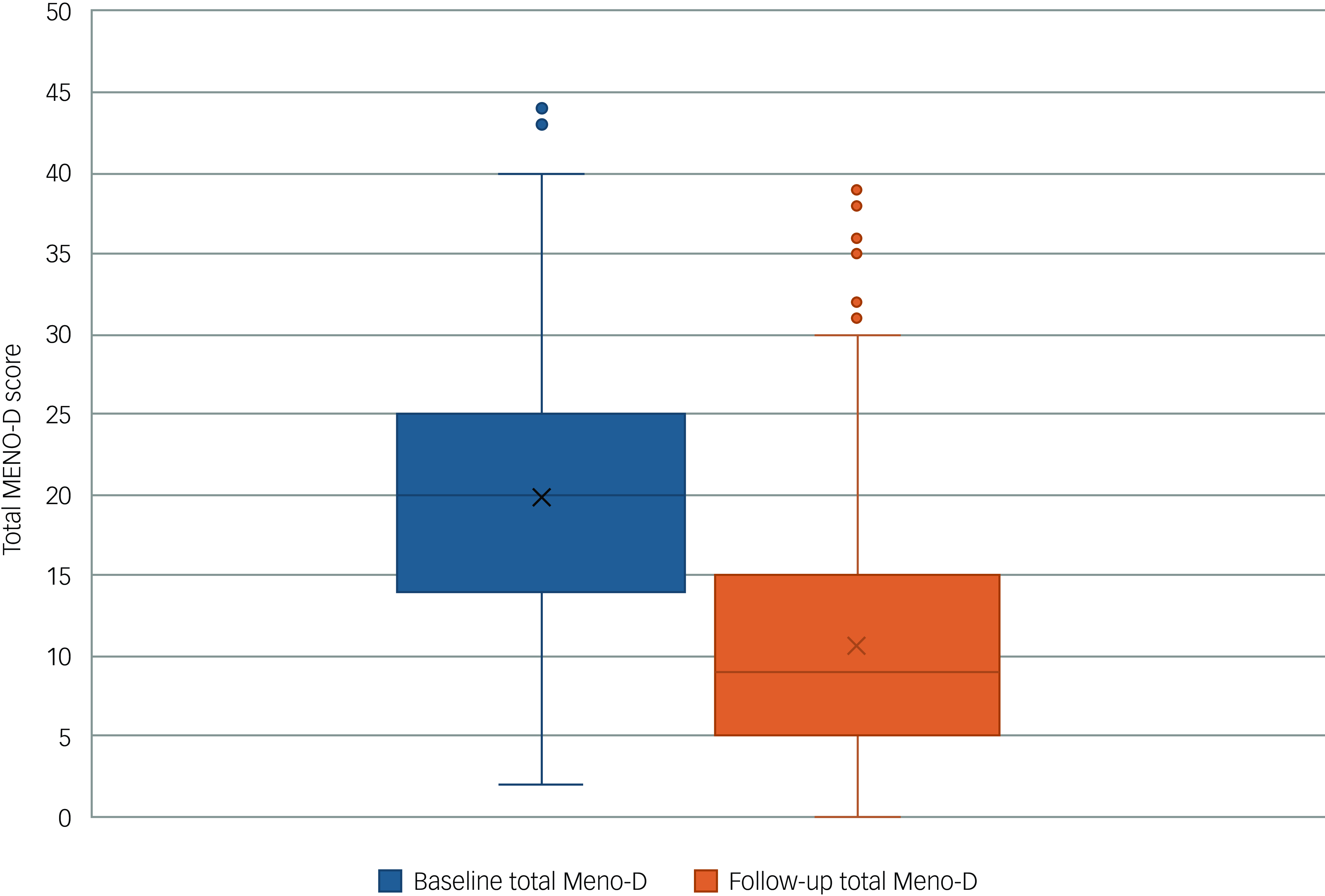

Change in Meno-D score for the whole cohort

Figure 1 illustrates the change in Meno-D score for the whole cohort across the study period. Mean and median Meno-D scores at baseline were 19.86 (s.d. 7.71) and 19.86 (IQR 14–25), respectively. Mean and median Meno-D scores at follow-up were 10.62 (s.d. 6.97) and 10.61 (IQR 5–15), respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The Meno-D score for the whole cohort reduced by, on average, 44.59% (95% CI −46.83 to −42.34%, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Tables 2b and 3).

Fig. 1 Box-and-whisker plot comparing global Meno-D scores at baseline and follow-up for all patients (N = 920). The horizontal line is the median, the box is the interquartile range and the whiskers represent values above and below the upper and lower quartiles. Outliers are represented as individual dots. Cross denotes the mean Meno-D score.

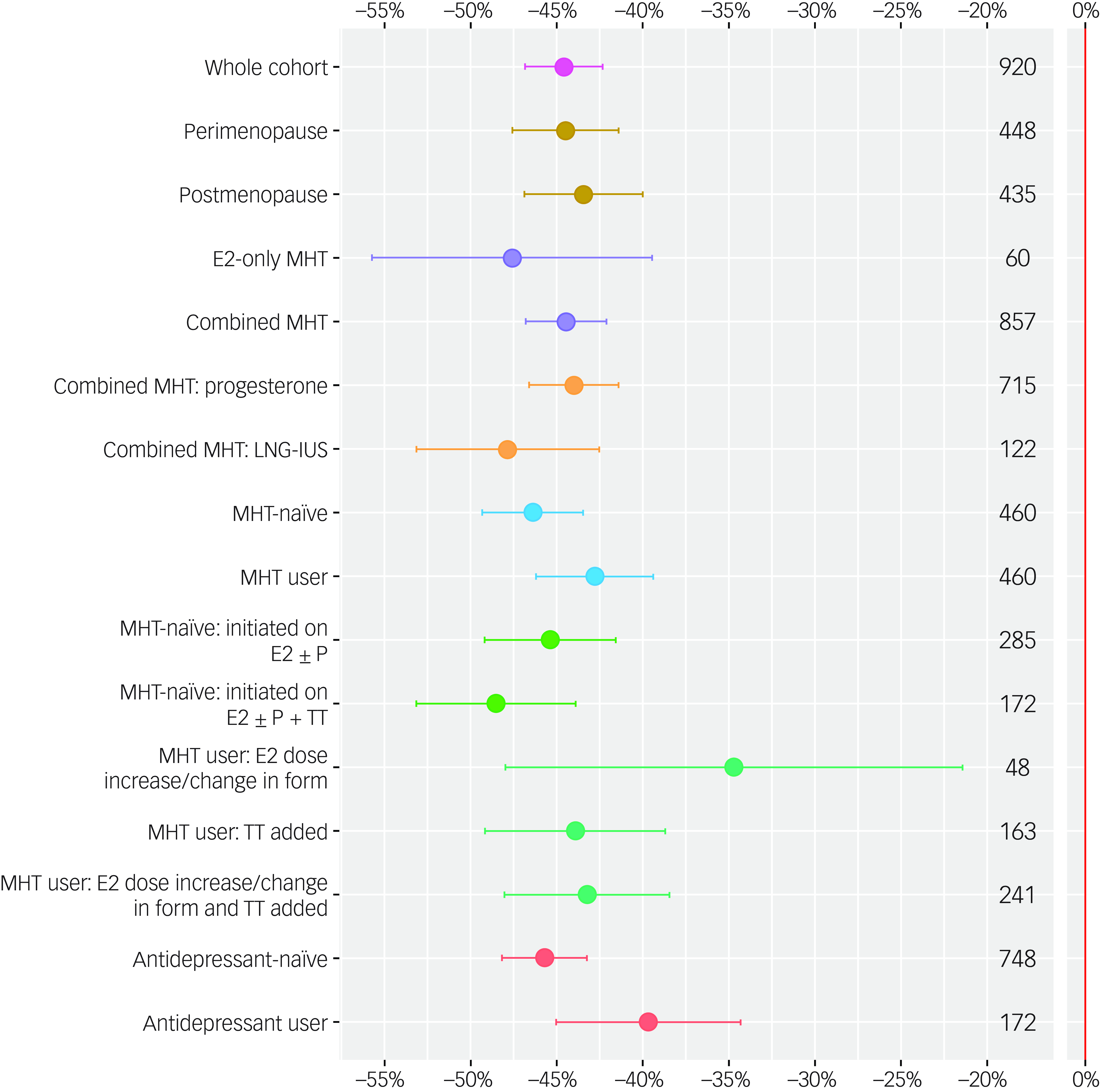

Comparison of change in Meno-D score among subgroups

Figure 2 compares mean percentage change in Meno-D scores from baseline to follow-up for the whole cohort, stratified by subgroup (Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 2 Mean percentage change in Meno-D scores (points), together with 95% CIs (error bars) for the whole cohort (pink), and for the following subgroups: menopause status (peri- versus postmenopausal, mustard yellow); menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) regimen (oestrogen only versus combined MHT, lilac); progestogen type (progesterone versus levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine system [LNG-IUS]), orange); use of MHT at baseline (MHT-naïve versus MHT users, blue); use of antidepressants (ADs) at baseline (AD-naïve versus AD users, coral); and MHT treatment strategy (women initiated on oestradiol [E2] with or without progestogen (progesterone or LNG-IUS [P] versus women initiated on E2 with or without P + transdermal testosterone [TT], light green); women already using MHT who received a higher E2 dose or change in formulation versus TT added versus a higher E2 dose/change in formulation and TT added, dark green. The number of patients in each group (n) is shown on the right-hand side of the plot. MHT, menopausal hormone therapy; E2, 17β-oestradiol; P, progestogen (progesterone or the LNG-IUS); P4, body-identical progesterone; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel-releasing system; TT, transdermal testosterone; AD, antidepressant.

Percentage change in Meno-D scores ranged from −34.70% (95% CI −47.98 to −21.41%) in women who were already using MHT at baseline and received a higher oestradiol dose and/or change in formulation, to −48.53% (95% CI −53.15 to −43.90%) in women who were MHT-naïve at baseline and initiated on all three hormones (E2 ± P4 + TT). Statistically significant reductions in mean Meno-D scores were observed in all subgroups (P < 0.001 for the reduction in each subgroup symptom score) (Supplementary Table 2a).

Linear modelling revealed that there was no evidence of a difference in percentage change in Meno-D score between peri- versus postmenopausal women (−44.49 and −43.45%, respectively, P = 0.81); in women who received E2-only MHT versus combined MHT (−47.61 and −44.47%, respectively, P = 0.72); in women who received body-identical progesterone versus the LNG-IUS (−44.01 and−47.84%, respectively, P = 0.31); in women initiated on E2 ± P versus E2 ± P + transdermal testosterone (−45.38 and−48.53%, respectively, P = 0.47); or in women already using MHT who received a higher E2 dose/change in formulation versus transdermal testosterone added versus a higher E2 dose/change in formulation and transdermal testosterone (−34.70,−43.93 and −43.25%, respectively, P = 0.38) (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

There was evidence at the 10% level of a greater reduction in Meno-D score in women initiated on MHT (MHT-naïve) versus following optimisation of dose/regimen (MHT users), but not at the 5% level (−46.38 and −42.79%, respectively, P = 0.09). The reduction in percentage change in Meno-D score was significantly greater in women not using antidepressants versus those prescribed concurrent antidepressant therapy (−45.71 and −39.68%, respectively, P = 0.0057) (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

Analysis of Meno-D individual symptom scores

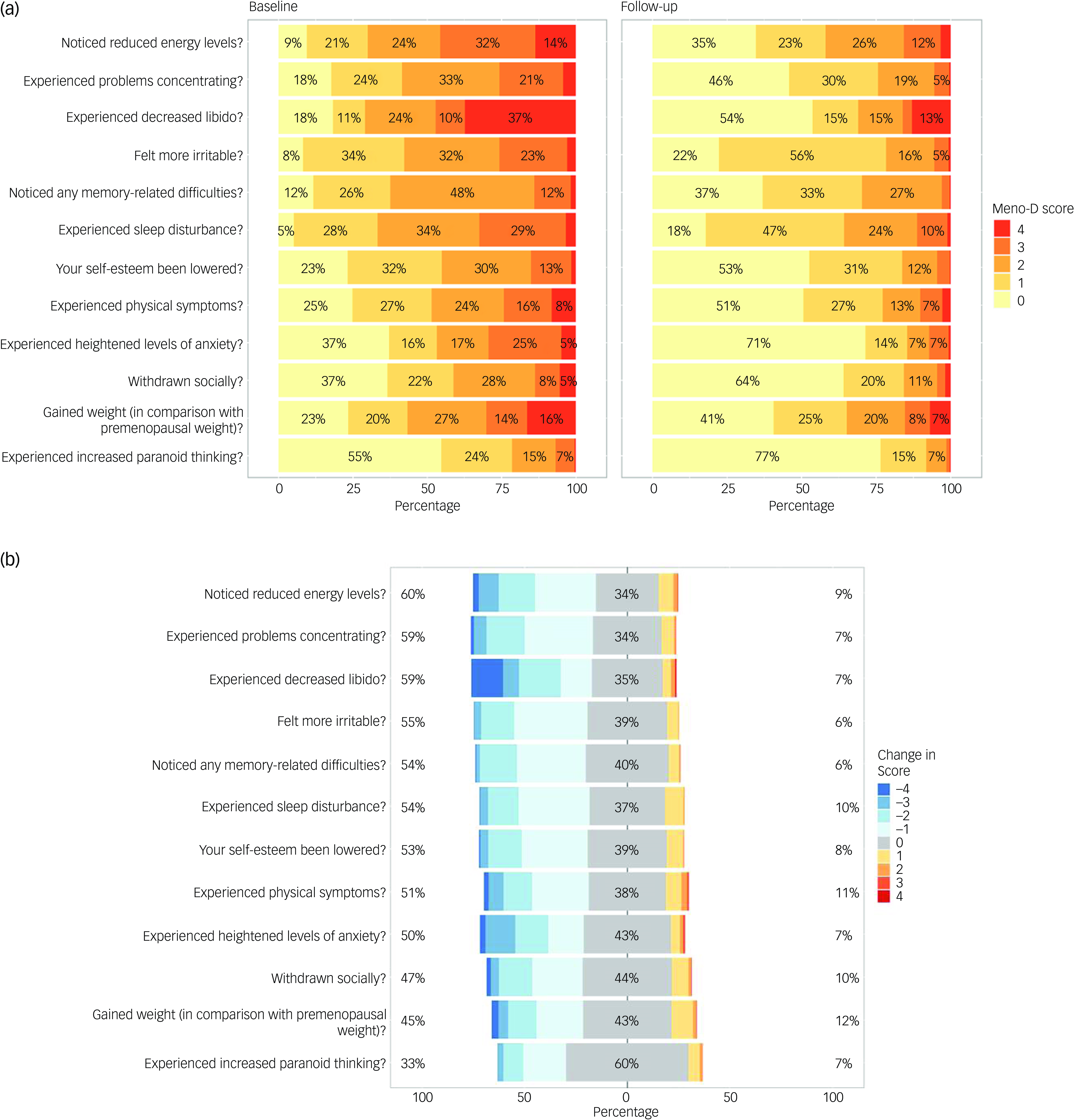

Figure 3(a) illustrates the number (%) of women who assigned symptom scores of 0 to 4 to each Meno-D symptom at both baseline and follow-up. Figure 3(b) illustrates the percentage change in each symptom score, from −4 to + 4, across the study period.

Fig. 3 (a) Percentage of patients who assigned symptom scores of either 0 (asymptomatic, shaded in yellow), 1, 2, 3 or 4 (severe, shaded in red) to each Meno-D item at baseline (left) and follow-up (right). (b) Number (%) of patients whose scores either decreased (shown in blue), increased (shown in yellow to red) or remained the same (shown in grey) across the study period, categorised by symptom. Left, percentage of women whose scores decreased (–1 to –4); right, percentage whose scores increased (+1 to +4). Symptoms are ordered from the highest to lowest percentage improvement.

With the exception of paranoid thinking, more than half the cohort experienced each mood symptom at baseline (Fig. 3(a)). Sleep disturbance was the most prevalent symptom at baseline (n = 873, 95%), followed by irritability (n = 844, 92%) and reduced energy (n = 833, 91%). Paranoid thinking was the least prevalent symptom (n = 417, 45% of women).

Across the study period, all 12 symptoms significantly improved (score reductions ranged from 33 to 60% (Fig. 3(b); P < 0.001 for each symptom score reduction; Supplementary Table 5). Reduced energy, difficulty concentrating and decreased libido improved the most – a reduction in symptom severity was reported by 60, 59 and 59% of women, respectively. Paranoid thinking was the symptom least likely to improve (33% of women reported a score reduction), which is consistent with the lower baseline prevalence.

Between 31 and 60% of women reported no change in individual symptom score during the study period (Fig. 3(b)). This was mainly because the majority of women without a particular symptom at baseline did not develop that symptom during the study interval (rather than a lack of treatment effect). For example, 503 women did not experience ‘paranoid thinking’ at baseline, and 463 did not report paranoid thinking at follow-up (only 40 women developed new-onset paranoid thinking during the study period) (Supplementary Table 6). Between 6 and 13% of women reported a worsening of symptoms (an increase in symptom score) during the study period (Fig. 3(b)). ‘Weight gain’ was the symptom most likely to worsen (n = 114 women, 12.4%), followed by ‘somatic symptoms’ such as pain or headaches (n = 104, 11.3%) (Fig. 3(b) and Supplementary Table 7).

Discussion

Following a mean follow-up of 107 days, global Meno-D score almost halved (44.6% reduction, P < 0.001) and all 12 individual mood symptoms significantly improved following initiation or optimisation of MHT (E2 ± P with or without transdermal testosterone). In subgroup analyses the reduction in Meno-D symptom scores ranged from 35 to 49%, with little difference between groups (peri- versus postmenopausal women, 44 and 43%, respectively, P= 0.81; E2-only versus combined MHT, 48 and 44%, respectively, P = 0.72; P4 versus LNG-IUS, 44.01 and 48%, respectively, P = 0.31; women initiated on E2 ± P versus E2 ± P + transdermal testosterone, 45 and 49%, respectively, P = 0.47; and MHT users who received a higher E2 dose/change in formulation versus testosterone added versus both a higher E2 dose/change in formulation + testosterone, 35, 44 and 43%, respectively, P = 0.38). There was a trend towards greater improvement in women initiated on MHT compared with those who attended for optimisation of oestradiol dose and/or regimen, but even women already using MHT at baseline significantly improved following customisation of dose/regimen (Meno-D score reductions of 46 and 43%, respectively, P = 0.09). Women using concurrent antidepressant therapy improved significantly less than those not treated with antidepressants (40 and 46% reduction in Meno-D score, respectively, P = 0.0057).

Research in context

Our results are consistent with previous data that demonstrate a beneficial effect of oestrogen-only MHT on mood in both peri- and postmenopausal women. Reference Toffol, Heikinheimo and Partonen18 In a narrative review of 17 studies including ten RCTs, benefit was more consistently seen in women treated with E2 versus CEE. Reference Toffol, Heikinheimo and Partonen18 This contrasts with the findings of a meta-analysis that pooled data from ten clinical trials (N = 1208) and found that body-identical E2 had no clinically significant effect on depressive symptoms. Reference Whedon, KizhakkeVeettil, Rugo and Kieffer31 However, the pooled studies were highly heterogenous; 1037 of the women included (86%) had no or minimal depressive symptoms at baseline (and were therefore unlikely to benefit), and half of the included studies failed to exclude or document concurrent antidepressant use, a potentially important confounder. Furthermore, most study participants were postmenopausal – including 417 women in the largest included study (mean age 67 years) who received just 14 mcg E2 daily (an ultra-low dose). Reference Yaffe, Vittinghoff, Ensrud, Johnson, Diem, Hanes and Grady32 The authors of this meta-analysis acknowledged that a potential benefit in perimenopausal women may have been diluted by studies including older postmenopausal women whose depressive symptoms were unrelated to menopause (and/or undertreated).

Transdermal E2 absorption is highly variable: up to 25% of women are ‘poor absorbers’ and need either higher than standard doses or a change in formulation to achieve therapeutic blood levels and relief of symptoms. Reference Glynne, Reisel, Kamal, Neville, McColl, Lewis and Newson33 Benefit is therefore likely to have been underestimated in clinical trials in which women received standardised on-label doses. In a small RCT, depressive symptom scores significantly decreased in women treated with transdermal E2 at 50 mcg/day (n = 27) and those assigned to placebo (n = 14), with no significant difference between treatment groups. Reference Joffe, Petrillo, Koukopoulos, Viguera, Hirschberg and Nonacs34 However, higher serum oestradiol concentration predicted mood improvement in perimenopausal women, suggesting that those who failed to improve may have been undertreated. In a 12-week RCT in which 50 perimenopausal women with moderate depressive symptoms were randomised to either transdermal E2 at 100 mcg/day (the highest licensed dose) or placebo, remission of depression was observed in 68% of women treated with E2 compared with 20% of those in the placebo group (P = 0.001). Reference de Novaes Soares, Almeida, Joffe and Cohen35 This highlights the importance of tailoring the dose to the individual, to ensure that all women achieve therapeutic levels, and may account for the substantial improvement in mood that was seen even in women already using MHT at baseline in our study following customisation of the MHT regimen (dose and/or formulation).

Women with an intact uterus using oestrogen therapy additionally require a progestogen for endometrial protection. The afore-cited review included 13 studies (8 RCTs) evaluating the effects of combined MHT on menopausal mood symptoms. Reference Toffol, Heikinheimo and Partonen18 The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) clinical trial was by far the largest study. According to the WHI, combined MHT did not result in a significant effect on mental health or depressive symptoms either at 1 year (N = 16,608) or after 3 years of treatment (N = 1511). Reference Hays, Ockene, Brunner, Kotchen, Manson and Patterson36 However, WHI participants were all postmenopausal (mean age 63 years), most reported no or minimal depressive symptoms at baseline and all women received oral, synthetic hormones (CEE and medroxyprogesterone acetate – a progestin). Progestogenic side-effects, including negative mood symptoms, occur in 20% of women and are usually associated with synthetic progestins; side-effects were less common in women treated with body-identical P4. Reference Piette15,Reference Panay and Studd27

The remaining 12 studies Reference Toffol, Heikinheimo and Partonen18 varied in size from 22 to 246 participants (mean N = 73). Perimenopausal women were included in only two studies (combined N = 82). Women were treated with different (fixed) doses of CEE or E2 combined with different synthetic progestins, either sequentially (cyclical progestin) or continuously (daily progestin), and followed up over periods ranging from 7 days to 2 years. Among women using continuous combined MHT, or during the progestogen phase in women using sequential MHT, mood improved in two studies, worsened in six and did not significantly change in four. The authors concluded that progestogens (synthetic progestins) in combined MHT may counteract the beneficial effects of oestrogen on mood, and even induce negative mood symptoms in some women.

In the current study, 86% of progestogen users received body-identical progesterone. In most women, P4 has beneficial hypnotic, anxiolytic and antidepressant effects and, compared with synthetic progestins, is less likely to cause side-effects including mood symptoms. Reference Piette15,Reference de Lignieres37 Fourteen per cent of women used the LNG-IUS. First-time use of an LNG-IUS is positively associated with a small increase in incident depression, Reference Larsen, Mikkelsen, Ozenne, Munk-Olsen, Lidegaard and Frokjaer38 but the daily release dose is small and the risk of side-effects is lower versus oral progestins. Reference Panay and Studd27 Use of progesterone or the LNG-IUS by study participants may have accounted for the improvement in mood in combined MHT users in our study, which contrasts with previous studies in which women received oral, synthetic progestins.

Very few studies have assessed the effects of body-identical E2 plus P4 on mood symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women. In a RCT of 172 euthymic peri- and early postmenopausal women, the incidence of new-onset depressive symptoms was halved in women randomised to transdermal E2 (100 mcg/day) plus P4 versus placebo for 12 months (incidence 17.3 and 32.3%, respectively, P = 0.03). Reference Gordon, Rubinow, Eisenlohr-Moul, Xia, Schmidt and Girdler39 In a second RCT, 693 peri- and early postmenopausal women were randomised to receive either oral CEE plus P4 (n = 220), transdermal E2 50 mcg/day plus P4 (n = 211) or placebo (n = 262). Depressive and anxiety symptoms improved in women treated with CEE + P4, but not in those treated with E2 + P4 versus placebo. Reference Gleason, Dowling, Wharton, Manson, Miller and Atwood40 However, the prevalence of mood symptoms at baseline was low: 8.25% of women treated with E2 + P4 (mild, 8.1%; moderate, 0.15%) versus 12.7% in the CEE + MP group (mild, 9.5%; moderate, 3.2%) and 9.5% in the placebo group (mild, 7.6%; moderate, 1.9%). A therapeutic effect is unlikely in women with no or minimal mood symptoms. Furthermore, around half of women treated with transdermal E2 at 50 mcg/day had subtherapeutic serum oestradiol levels. Reference Glynne, Reisel, Kamal, Neville, McColl, Lewis and Newson33 It is therefore also possible that women in the E2 + P4 group failed to improve because the dose was suboptimal.

In the current study, mood symptoms significantly improved in women using MHT and concurrent antidepressant therapy, but the percentage reduction in Meno-D score was significantly lower in antidepressant users versus non-users (40 and 46%, respectively, P = 0.0057). Our findings contrast with those of previous studies that have mainly demonstrated greater improvement in mood in women co-prescribed MHT and antidepressants. Reference Toffol, Heikinheimo and Partonen18 This may be because the women treated with antidepressants in our study had more severe symptoms at baseline (baseline Meno-D score for antidepressant users 22.23 versus antidepressant-naïve, 19.29): the absolute reduction in Meno-D score in each group was similar (−9.27 and −9.22 points, respectively; Supplementary Table 2(a)), but percentage change was lower in antidepressant users because the baseline score was higher. Until more data are available, the prevailing view is that combined antidepressant and hormone therapy is a valuable therapeutic option, especially for women with severe symptoms, those with a past history of clinical depression and/or those who do not achieve depressive symptom relief with either antidepressant therapy or MHT alone. Reference Herson and Kulkarni41

In the current study, the greatest improvement in symptom score was observed in MHT-naïve women initiated on transdermal testosterone alongside E2 ± P4 or the LNG-IUS (49% reduction in Meno-D score).

There is a paucity of data concerning the impact of testosterone on menopausal mood symptoms. In early studies, surgically menopausal women treated with testosterone, either alone or in combination with oestrogen, reported more positive effects on mood than those treated with oestrogen alone or placebo/untreated controls. Reference Sherwin and Gelfand42,Reference Sherwin43 However, women received parenteral (intramuscular) synthetic hormones that caused supraphysiological testosterone levels, meaning that the superior efficacy of testosterone could have been a pharmacologic rather than a physiologic effect.

In 2006, a 24-week, double-blind RCT randomised 72 women with postmenopausal depression to one of four treatment groups: venlafaxine plus placebo, venlafaxine plus CEE + MPA, venlafaxine plus methyltestosterone and venlafaxine plus methyltestosterone and CEE + MPA. Reference Dias, Kerr-Corrêa, Moreno, Trinca, Pontes and Halbe44 A trend towards higher remission rates was observed in women treated with synthetic hormones, but only women in the venlafaxine plus methyltestosterone group were significantly more likely to remit. Unfortunately, the study lacked power because a third of the women discontinued treatment – mainly due to side-effects that are typically associated with venlafaxine, and it was not possible to draw definitive conclusions.

In 2019, a meta-analysis pooled data from four RCTs in which the primary outcome was the effect of body-identical testosterone on sexual function, concluding that the available data did not show an effect of testosterone on depressed mood in postmenopausal women. Reference Islam, Bell, Green, Page and Davis45 The studies included were small (combined N = 636), short (median study duration 12 weeks) and varied considerably in design. Only one RCT included perimenopausal women, but this was designed to assess the impact of testosterone on antidepressant-emergent sexual dysfunction (rather than menopausal mood symptoms). The prevalence of depressive symptoms at baseline was either low (three RCTs) or unreported (one RCT), and none of the studies were sufficiently powered to detect an effect on mood. The authors of this meta-analysis concluded that the effects of testosterone on mood and well-being warrant further investigation.

Because data are limited, national and international guidelines recommend testosterone only for the treatment of hypo-active sexual desire disorder in peri- and postmenopausal women. 20,Reference Davis, Baber, Panay, Bitzer, Cerdas Perez and Islam46,Reference Parish, Simon, Davis, Giraldi, Goldstein and Goldstein47 However, transdermal testosterone in physiologic doses is very safe, Reference Davis, Baber, Panay, Bitzer, Cerdas Perez and Islam46,Reference Parish, Simon, Davis, Giraldi, Goldstein and Goldstein47 and women with menopausal mood symptoms can be offered a trial of testosterone therapy provided they understand that supporting evidence is limited and that they have been supported to make an informed decision (off-licence use).

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. In contrast with most previous studies, the sample size was large and depressive symptoms were highly prevalent at baseline. Furthermore, the real-world setting enabled us to assess the effect of both MHT initiation and optimisation of dose and/or regimen in established MHT users. A treatment effect may have been underestimated in previous studies that enrolled women with no or minimal mood symptoms and/or treated all women with the same on-label dose and formulation. In the current study, all women received body-identical transdermal oestradiol ± testosterone, and most (86% of combined MHT users) received body-identical progesterone. Compared with oral, synthetic hormones, transdermal 17β-oestradiol and progesterone are usually better tolerated and have fewer associated risks; in observational studies, transdermal 17β-oestradiol has not been shown to increase the risk of thrombosis or stroke, and progesterone has not been shown to increase the risk of breast cancer, but randomised clinical trials are lacking. Reference Levy and Simon13 Consequently, transdermal 17β-oestradiol and body-identical progesterone are usually considered the optimal MHT regimen, Reference Ruan and Mueck48,Reference L’Hermite49 although patient preference and individualised care are key. Reference Baber, Panay and Fenton16,17,Reference Hamoda, Panay, Pedder, Arya and Savvas19 Assessing the impact of body-identical hormones on mood enhances the generalisability of our results, because 17β-oestradiol and micronised progesterone are the most frequently prescribed MHT formulations in the UK. 50 Regarding testosterone, there is a dearth of data concerning the effects of testosterone on menopausal symptoms beyond reduced libido. Our findings add to the available literature, and signal a need for further research in this area. Finally, we used a validated outcome measure, the Meno-D scale, to measure change in mood symptoms across the study period. The Meno-D scale is the only questionnaire specifically designed to measure the presence and severity of perimenopausal mood symptoms. Reference Kulkarni, Gavrilidis, Hudaib, Bleeker, Worsley and Gurvich30 Questionnaires were completed in real time, at baseline and at review consultation, reducing the risk of recall bias.

Our study also has several limitations. First, 94.5% of study participants were White British women able to access private healthcare. Women who access private healthcare are generally less deprived, healthier and subject to different life stressors that can influence mood. Reference Remes, Lafortune, Wainwright, Surtees, Khaw and Brayne51 Both these factors limit the generalisability of our findings. Second, this was a retrospective cohort study with no control arm. Clinical improvement may therefore represent a placebo effect, or spontaneous symptom resolution over time. In a systematic review of 24 RCTs, hot flush frequency was reduced by 57.7% (95% CI 45.1–67.7) in women randomised to placebo, Reference MacLennan, Broadbent, Lester and Moore52 and a placebo effect may also account for the improvement in mood recorded in our study. Third, we did not collect data concerning other menopausal symptoms (e.g. disrupted sleep, vasomotor symptoms, joint pain or sexual dysfunction) that negatively impact mood and also improve with MHT. The improvement in mood recorded may therefore have resulted from confounding factors not adjusted for in our analysis. Fourth, women with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) and surgical menopause are more likely to experience negative mood symptoms Reference Rocca, Grossardt, Geda, Gostout, Bower and Maraganore53,Reference Sarrel, Sullivan and Nelson54 and usually require higher oestrogen doses and/or testosterone for symptom relief. Reference Sarrel, Sullivan and Nelson54,Reference Panay, Anderson, Nappi, Vincent, Vujovic, Webber and Wolfman55 In the study cohort, 9 women (1.0%) had POI and 71 (7.7%) experienced surgical menopause (surgical menopause <40 years, n = 23; surgical menopause >40 years, n = 48). These numbers were too small to permit subgroup comparisons, and it is possible that the beneficial effects of MHT on mood among the whole cohort may have been diluted by the inclusion of younger and surgically menopausal women with more frequent and/or severe mood symptoms (optimisation of dose and regimen can take longer in women with high dose requirements). Fifth, antidepressant use was recorded at baseline but not at the review consultation. It is possible that some women initiated (or discontinued) antidepressant therapy or received other treatment for psychological symptoms during the study interval. Sixth, the use of real-world data is a limitation, as well as a strength. For example, although the mean duration of follow-up was 107 days, it ranged from 21 to 201 days. Menopausal symptoms fluctuate in peri- and early menopause, clinical response to MHT may take several months and optimisation of the dose/regimen may take even longer. Furthemorer, although compliance with MHT is generally good, up to 25% of women may not take their MHT as prescribed. Reference Serfaty, de Reilhac, Eschwege, Ringa, Blin and Nandeuil56 Both the short period of follow-up and poor or suboptimal adherence may have underestimated treatment benefit.

In summary, our real-world retrospective cohort study found that menopausal mood symptoms significantly improved following the initiation or optimisation of body-identical 17β-oestradiol ± progesterone or the LNG-IUS, with or without testosterone. This supports the notion that MHT including testosterone has psychopharmacological benefits, and highlights a need for high-quality, adequately powered clinical trials to further investigate the long-term efficacy of body-identical hormone therapy when administered in physiologic doses.

Based on our study findings, perimenopausal women with new-onset negative mood symptoms (not meeting the criteria for a diagnosis of major depressive episode) can be offered a trial of body-identical MHT for symptom relief. The LNG-IUS can also be used to provide endometrial protection in combined MHT regimens, but may exacerbate psychological symptoms in some women. Postmenopausal women with significant mood symptoms may also benefit from body-identical hormone replacement, but more research is needed to confirm this finding. Clinical guidelines recommend that women with major clinical depression should receive antidepressants and/or proven psychotherapies (e.g. cognitive-behavioural therapy). MHT may augment the clinical response to antidepressants and/or psychotherapy, Reference Baber, Panay and Fenton16,17 but should not be used in isolation for midlife and older women with major clinical depression.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.101

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of the study are available within the article and/or its Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants for granting us permission to use their data for the purposes of this study. We thank Jo Morrison, Select Statistical Services Ltd, for her assistance with data analysis.

Author contributions

S.G., D.R., A.K. and L.N. conceived and designed the study. A.K. and D.R. collected the data. S.G. and L.M. analysed the data. S.G. led interpretation of study findings. All authors contributed to the interpretation of findings. S.G. led the draft of the work. All authors read, commented on and approved the final version of the paper. S.G. is the lead author. J.K. is the senior clinician. S.G. and J.K. act as guarantors.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

J.K. is part of the guest editorial team and did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper; has received funding for other clinical trials from pharmaceutical industries not related to the work presented in this paper: Boehringer Ingelheim, Spinogenix and Jansen-Cilag, and receives funding from the Australian NHMRC for work related to the development of Meno-D, which is used in this study. All other authors have no interests to declare.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.