Background

In recent years there has been a growing awareness of the comorbidity experienced by people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), particularly regarding psychiatric conditions. (Throughout this report we used the term ‘comorbid/ity’, which we consider to be synonymous with the alternative terms of ‘co-occurring’, or ‘coexisting.) An umbrella review of psychiatric conditions in people with ASD published in 2020 found a very high burden of comorbidity across several conditions, reported in 26 systematic reviews and meta-analyses.Reference Hossain, Khan, Sultana, Ma, McKyer and Ahmed1 Physical conditions in people with ASD have received lesser research attention. An article in 2011 reported an urgent need for research in this area because of limited literature but probably greater comorbidity than in other people.Reference Emerson, Hatton, Hastings, Felce, McCulloch and Swift2

Two reviews in 2013 commented that research into comorbidity in people with ASD was of recent origin, and much more was needed.Reference Mannion and Leader3,Reference Matson and Goldin4 A scope of the literature in 2018 reported that people with ASD have high rates of physical comorbidity, but findings were based on few studies.Reference Cashin, Buckley, Troller and Lennox5 Since then, further studies and systematic reviews have been published, although this field of research is still relatively underdeveloped. Comorbid physical conditions can significantly affect quality of life, so it is important that practitioners and carers are aware of commonly occurring conditions to raise their index of suspicion and address differential diagnosis, thus resulting in earlier detection and, therefore, treatment, care and better outcomes.

Aims

The aim of our study was to identify what is and what is not known about comorbid physical conditions in people with ASD, through undertaking an umbrella systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (as these synthesise existing studies, resulting in a pooling of knowledge that is more exhaustive than that contained in single studies).Reference Aromataris, Fernandez, Godfrey, Holly, Kahil and Tungpunkom6 Our aims were designed to be of clinical relevance, not to delineate aetiology. The specific research questions were:

(a) How common are comorbid physical conditions in people with ASD?

(b) Are specific comorbid physical conditions more prevalent in people with ASD than in the general population?

(c) Are there gaps in the evidence base on comorbid physical conditions in people with ASD?

Method

This review was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, registration number: CRD42015020896).

Literature sources

A systematic search strategy was used to identify existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses relating to comorbid physical conditions in people with ASD. The search was conducted through five databases: PsycINFO, CINAHL, Medline, Embase and Cochrane databases. The search was performed on the 21 August 2019. No time limits were applied; all years of literature were searched. The search was limited to publications in English.

Search terms

A combination of the following search terms was used for PsycINFO, CINAHL, Medline and Embase databases:

(a) 1. ‘autis*’ AND ‘systematic review’

(b) 2. ‘autis*’ AND ‘meta-analysis’

(c) 3. ‘pervasive developmental disorder’ AND ‘systematic review’

(d) 4. ‘pervasive developmental disorder’ AND ‘meta-analysis’

(e) 5. ‘Asperger*’ AND ‘systematic review’

(f) 6. ‘Asperger*’ AND ‘meta-analysis’

(g) 7. ‘ASD’ AND ‘systematic review’

(h) 8. ‘ASD’ AND ‘meta-analysis’

(i) 9. 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8

Inclusion criteria

(a) ASD.

(b) All ages.

(c) Comorbid physical condition(s).

(d) Systematic review or meta-analysis of peer-reviewed research.

(e) For reviews which include people both with and without ASD, results for people with ASD are presented separately, and/or >50% of the total sample have ASD.

(f) English language.

Exclusion criteria

(a) Non-human studies.

(b) Brain-imaging studies.

(c) Genetic studies on syndromes.

(d) Studies on symptoms of ASD.

(e) Treatment studies of comorbid physical conditions.

(f) Reviews assessed as low quality using a quality assessment tool.

Procedures

Papers were selected if they met the predefined inclusion criteria. Papers were initially screened for suitability based on their title and abstract, and then candidate papers were read in full. A second reviewer also read a random 10% of titles and abstracts to ensure the selection approach was systematic. Any discrepancies were planned to be resolved through discussion. Two authors then read the full text of the potentially eligible studies to assess their eligibility. Using a structured database, data were then extracted from the selected review papers on the number and type of studies included in the review, size of studies, population types, definition of ASD, study designs, comparison groups, co-occurring physical conditions included and their definitions, findings and the quality of the review. Additional hand searches were performed to check for relevant reviews or meta-analyses in the references cited in the selected articles.

The Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for systematic reviews and research synthesis was used to assess quality.Reference Aromataris, Fernandez, Godfrey, Holly, Kahil and Tungpunkom6 It includes 11 items on: explicit statement of the research question, use of inclusion criteria, appropriateness of search strategy, adequacy of the sources and resources to search, criteria for appraising studies, double assessment, methods to minimise errors in data extraction, appropriateness of methods to combine studies, assessment of publication bias, whether policy and/or practice recommendations are supported by the data, and whether directions for new research are appropriate. We categorised studies as low, medium, or high quality if they received a score of 0–5, 6–8 and 9–11, respectively. Reviews that were of low quality on this measure were then excluded. The authors discussed together the quality assessment findings to reach agreement.

Results

Figure 1 summarises the number of reviews included/excluded at each stage. The search returned 5552 records, of which 223 papers were identified to be read in full. There were no disagreements between the first and second reviewer.

Fig. 1 Study selection process.

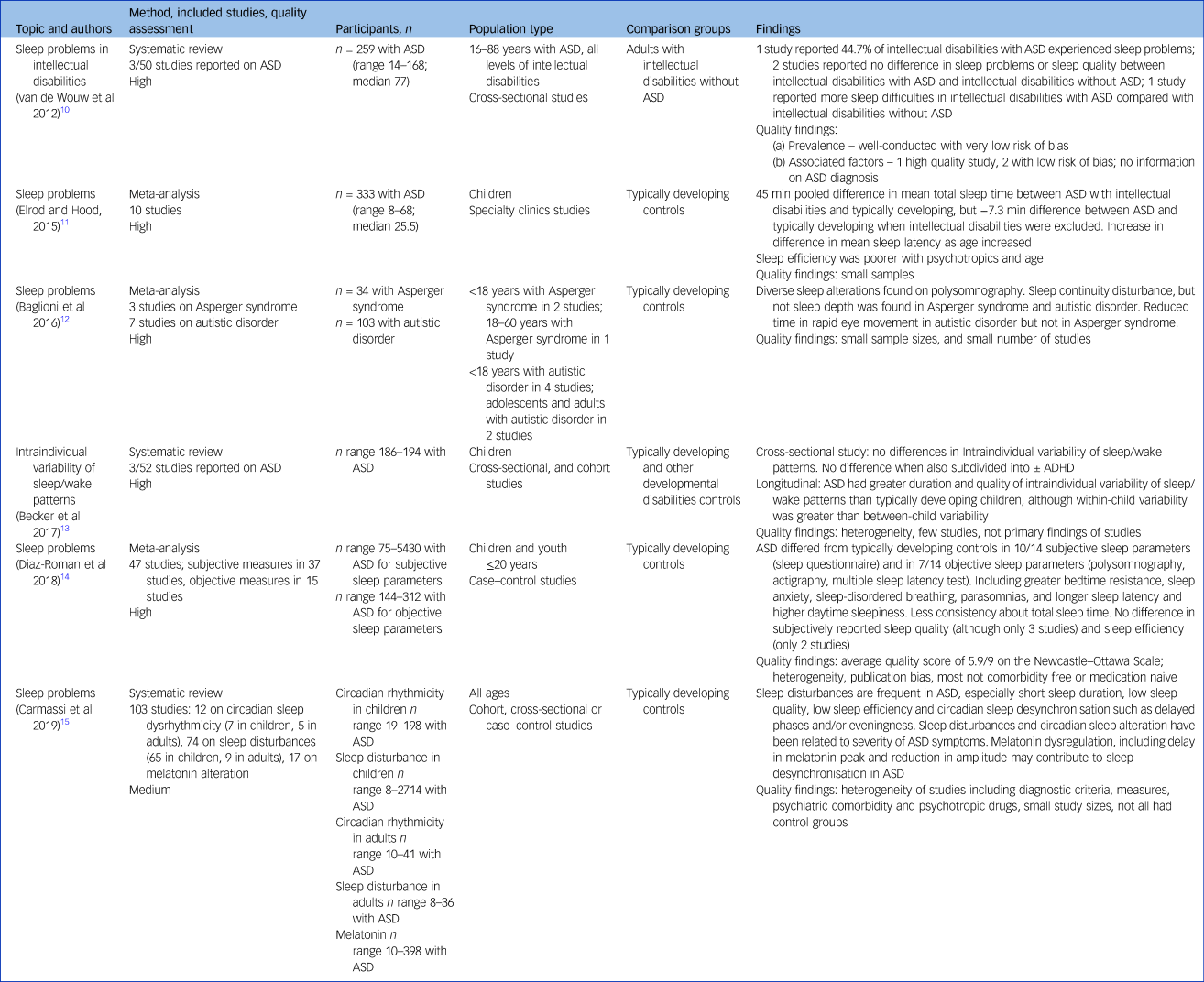

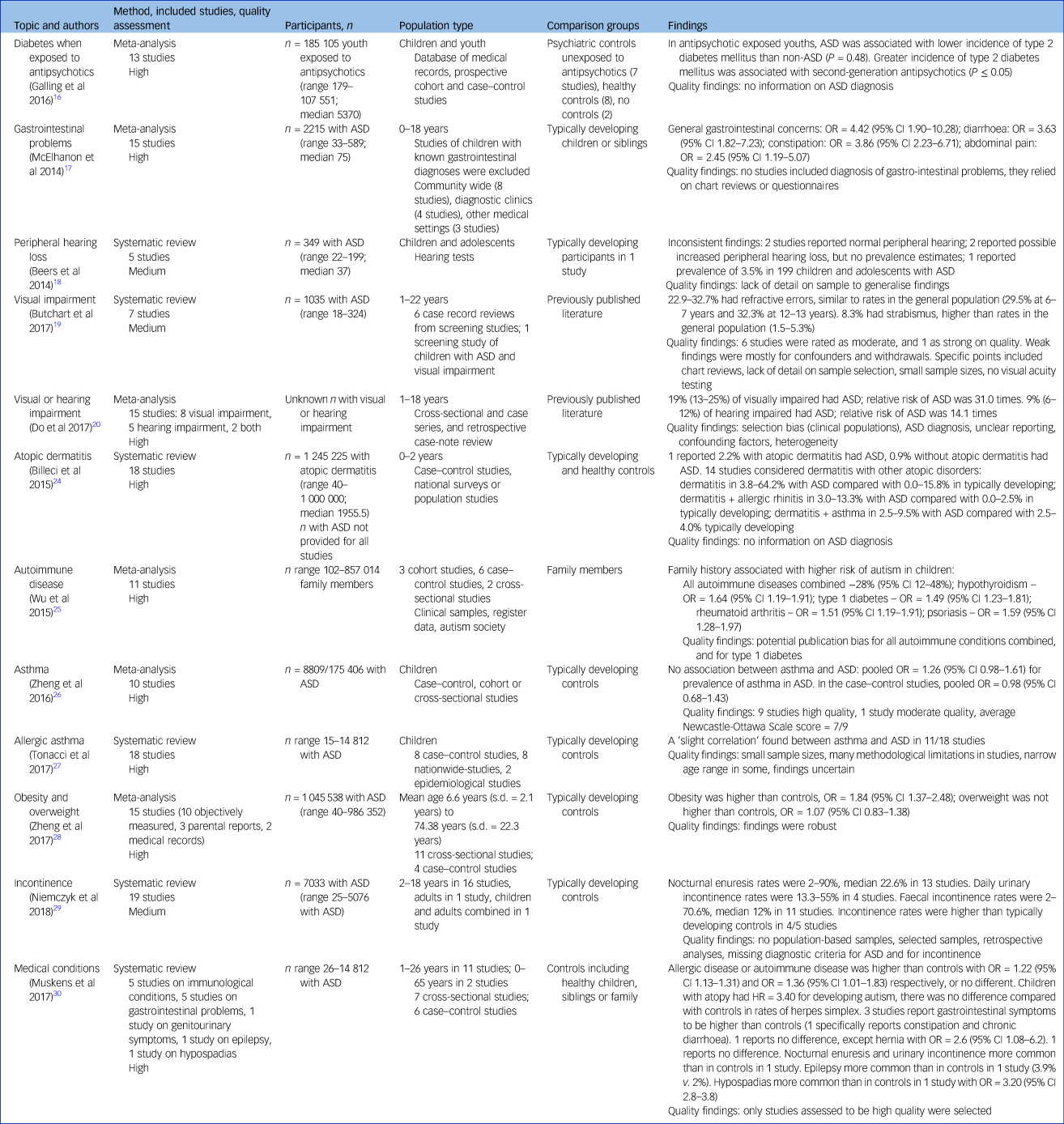

The 223 papers were carefully read and classified as either meeting or not meeting inclusion criteria. This resulted in 27 articles selected for data extraction. In general, the quality of the reviews was good. Sixteen studies were assessed as high quality, 8 as medium and 3 were assessed as low quality and excluded from the umbrella review, resulting in 24 studies being the final number selected for inclusion in the review.Reference Woolfenden, Sarkozy, Ridley, Coory and Williams7–Reference Muskens, Velders and Staal30 The most commonly noted omissions related to quality assessment, publication bias and methods used to minimise errors in data extraction. The 24 reviews included 12 meta-analyses and 12 systematic reviews without meta-analysis. The reviews are summarised in Tables 1–4.

Table 1 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on epilepsy in ASD

ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

Table 2 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on sleep in ASD

ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

Table 3 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on oral health in ASD

ASD, autism spectrum disorder; DMFT, decayed, missing and filled teeth index.

Table 4 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on diabetes, gastro-intestinal problems, hearing, vision, dermatitis, autoimmune disease, asthma, obesity, incontinence, and other conditions in ASD

ASD, autism spectrum disorder; OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio.

Of the 24 included reviews, 6 were on sleep;Reference Van de Wouw, Evenhuis and Echteld10–Reference Carmassi, Palagini, Caruso, Masci, Nobili and Vita15 3 on sensory impairments (not sensory sensitivities; 1 on peripheral hearing loss,Reference Beers, McBoyle, Kakance, Dar Santos and Kozak18 1 on visual impairment,Reference Butchart, Long, Brown, McMillan, Bain and Karatzias19 and 1 on visual or hearing impairmentReference Do, Lynch, Macris, Smyth, Stavrinakis and Quinn20 ); 3 on epilepsy;Reference Woolfenden, Sarkozy, Ridley, Coory and Williams7–Reference Strasser, Downes, Kung, Cross and de Haan9 3 on oral health;Reference Bartolomé-Villar, Mourelle-Martínez, Diéguez-Pérez and de Nova-García21–Reference Robertson, Schwendicke, de Araujo, Radford, Harris and McGregor23 1 on asthmaReference Zheng, Zhang, Zhu, Huang, Qu and Mu26 and 1 on allergic asthma;Reference Tonacci, Billeci, Ruta, Tartarisco, Pioggia and Gangemi27 1 each on diabetes,Reference Galling, Roldán, Nielsen, Nielson, Gerhard and Carbon16 gastro-intestinal conditions,Reference McElhanon, McCracken, Karpen and Sharp17 atopic dermatitis,Reference Billeci, Tonacci, Tartarisco, Ruta, Pioggia and Gangemi24 autoimmune disease,Reference Wu, Ding, Wu, Li, Guoming and Hou25 obesity,Reference Zheng, Zhang, Shiping, Zhao, Wang and Huang28 incontinence;Reference Niemczyk, Wagner and von Gontard29 and 1 review on 5 conditions – immunological, gastro-intestinal, incontinence, epilepsy and hypospadias.Reference Muskens, Velders and Staal30 Fifteen studies were on children and young people,Reference Elrod and Hood11,Reference Becker, Sidol, van Dyk, Epstein and Beebe13,Reference Diaz-Roman, Zhang, Delorme, Beggiato and Cortese14,Reference Galling, Roldán, Nielsen, Nielson, Gerhard and Carbon16–Reference Tonacci, Billeci, Ruta, Tartarisco, Pioggia and Gangemi27 8 were on children, young people and adults,Reference Woolfenden, Sarkozy, Ridley, Coory and Williams7–Reference Strasser, Downes, Kung, Cross and de Haan9,Reference Baglioni, Nanovska, Reynolds, Regen, Spiegelhalder and Feige12,Reference Carmassi, Palagini, Caruso, Masci, Nobili and Vita15,Reference Zheng, Zhang, Shiping, Zhao, Wang and Huang28–Reference Muskens, Velders and Staal30 and 1 study was on adults only.Reference Van de Wouw, Evenhuis and Echteld10

Although the quality of the included reviews was good, most, in their own quality assessments, reported several limitations in the papers they included, and also considerable heterogeneity that precluded meta-analysis for several of the reviews. Studies drew their samples from a range of settings, including several reliant on clinical populations, making comparisons difficult. There were also inconsistent findings reported between studies in some of the reviews, hence there is uncertainty in some of the conclusions that can be drawn. Additionally, as Tables 1–4 show, prevalences with confidence intervals, and odds ratios in comparison with the general population were often not reported nor possible to synthesise. Recognising these limitations, our results suggest that answers to our research questions are as follows.

How common are comorbid physical conditions in people with ASD?

Comorbid physical conditions are common in people with ASD. None of the studies enabled us to say how common physical comorbidities are overall, as the reviews studied specific conditions, or in one review five types of conditions (i.e. a limited number of conditions). We did not identify any systematic reviews on overall comorbidity or multimorbidity in people with ASD.

Are specific comorbid physical conditions more prevalent in people with ASD than in the general population?

Some specific comorbid physical conditions are more prevalent in people with ASD than in the general population.

(a) Sleep problems are more common in people with ASD than other people, with some of this attributable to co-occurring intellectual disabilities.Reference Van de Wouw, Evenhuis and Echteld10–Reference Carmassi, Palagini, Caruso, Masci, Nobili and Vita15 There are some inconsistencies in findings, for example regarding any differences in sleep quality and sleep efficiency.Reference Van de Wouw, Evenhuis and Echteld10,Reference Diaz-Roman, Zhang, Delorme, Beggiato and Cortese14,Reference Carmassi, Palagini, Caruso, Masci, Nobili and Vita15 The sleep studies included objective measures of sleep in people with ASD, and additionally most also considered sleep in relation to some or all of physical, psychiatric, behavioural, other neurodevelopmental, and intellectual abilities/conditions, and medication,Reference Van de Wouw, Evenhuis and Echteld10–Reference Diaz-Roman, Zhang, Delorme, Beggiato and Cortese14 or excluded these.Reference Carmassi, Palagini, Caruso, Masci, Nobili and Vita15

(b) Epilepsy is common.Reference Woolfenden, Sarkozy, Ridley, Coory and Williams7–Reference Strasser, Downes, Kung, Cross and de Haan9,Reference Muskens, Velders and Staal30 The reviews did not report a comparison with the general population (with the exception of one, which included only a single study on epilepsy),Reference Muskens, Velders and Staal30 but the estimated pooled prevalences are higher than those previously reported in the general population. Prevalence varies depending upon co-occurring intellectual disabilities, age and aetiology of epilepsy.Reference Woolfenden, Sarkozy, Ridley, Coory and Williams7–Reference Strasser, Downes, Kung, Cross and de Haan9 Epilepsy is more common in females with ASD than males with ASD.Reference Strasser, Downes, Kung, Cross and de Haan9

(c) Self-inflicted oral soft tissue injury is more common in people with ASD than the general population.Reference Bartolomé-Villar, Mourelle-Martínez, Diéguez-Pérez and de Nova-García21 Dental caries are common, but results are inconsistent as to whether they are more common than in the general population, and on comparisons of dental treatment for caries.Reference Bartolomé-Villar, Mourelle-Martínez, Diéguez-Pérez and de Nova-García21–Reference Robertson, Schwendicke, de Araujo, Radford, Harris and McGregor23

(d) Findings on peripheral hearing loss are inconsistent.Reference Beers, McBoyle, Kakance, Dar Santos and Kozak18 Among people with hearing impairment, the relative risk of ASD was high.Reference Do, Lynch, Macris, Smyth, Stavrinakis and Quinn20

(e) Refractive errors are common but no different to the general population, whereas strabismus may be higher than for the general population.Reference Butchart, Long, Brown, McMillan, Bain and Karatzias19 Among people with visual impairment, the relative risk of ASD was very high.Reference Do, Lynch, Macris, Smyth, Stavrinakis and Quinn20

(f) Diarrhoea, constipation, and abdominal pain appear to be reported more for children with ASD than for their siblings or general population, although there is some inconsistency.Reference McElhanon, McCracken, Karpen and Sharp17,Reference Muskens, Velders and Staal30 Hernia was the only gastrointestinal condition reported to be more common in one of the studies.Reference Muskens, Velders and Staal30

(g) Rates of ASD are higher in people with atopic dermatitis, and people with atopic dermatitis plus allergic rhinitis, than in people who do not have these conditions. Autoimmune disease is also more common than in the general population.Reference Billeci, Tonacci, Tartarisco, Ruta, Pioggia and Gangemi24,Reference Muskens, Velders and Staal30 Additionally, parents with autoimmune disorders (hypothyroidism, type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis) are at higher risk of their children having ASD, alluding to an association between these conditions and ASD.Reference Wu, Ding, Wu, Li, Guoming and Hou25

(h) Obesity is more common in people with ASD than in the general population.Reference Zheng, Zhang, Shiping, Zhao, Wang and Huang28

(i) Incontinence is more common in people with ASD than in the general population.Reference Niemczyk, Wagner and von Gontard29,Reference Muskens, Velders and Staal30

(j) Hypospadias might be more common in males with ASD, but the finding relates to only one study.Reference Muskens, Velders and Staal30

Conversely to the conditions above, which appear to be more common in people with ASD, asthma probably is not,Reference Zheng, Zhang, Zhu, Huang, Qu and Mu26 and in antipsychotic-exposed youth, incidence of type 2 diabetes was less common than in those without ASD.Reference Galling, Roldán, Nielsen, Nielson, Gerhard and Carbon16

Are there gaps in the evidence base on comorbid physical conditions in people with ASD?

There are substantial gaps in the evidence base on comorbid physical conditions in people with ASD. There is good evidence that sleep problems, epilepsy, sensory impairments, atopy, autoimmune conditions and obesity are common, more so than in the general population, despite some inconsistencies in findings. However, it is harder to draw conclusions on other conditions, because of fewer studies having been undertaken, and inconsistency in their findings. The results point to considerable comorbidity in several areas, but further research is needed. There were no systematic reviews that met our criteria in some areas, such as cardiovascular conditions, cancers, neurological conditions apart from epilepsy, and musculoskeletal conditions.

Discussion

Principal findings and interpretation

Our study has demonstrated that comorbid physical conditions are common in people with ASD. The study is important as its design enabled coverage of a wide range of physical conditions. There is evidence to suggest that people with ASD experience health inequalities compared with the general population, including higher rates of sleep problems, epilepsy, sensory impairments, atopy, autoimmune disorders and obesity, and probably also other conditions that have been studied to a lesser extent. However, evidence is limited regarding other conditions, and has inconsistencies in findings and methodological differences. There are also few studies on some conditions. As far as our umbrella review identified, some areas have not been systematically reviewed at all, such as cardiovascular conditions, cancers, neurological conditions apart from epilepsy and musculoskeletal conditions. We therefore conclude that comorbidity is common in people with ASD, but there remain considerable gaps in the evidence base. Information about the comorbid physical health of people with ASD is important in order to heighten awareness for clinicians to aid in their assessments and differential diagnoses, especially because of the added complexity of such assessments with people with ASD given their communication needs.

While we identified a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on comorbid physical conditions in people with ASD, and the quality of the reviews was good, they highlighted that the quality of many of the individual studies they included was limited. This included studies of small or highly selected samples, and with no power considerations. Detailed information on the samples’ recruitment was often not comprehensive or was lacking. In some cases, inconsistent results were reported as a result of varying study designs, different source populations and participant characteristics, as well as small samples. Some studies had unclear statistical methods or inclusion criteria. Some studies did not discuss how ASD and its comorbid physical conditions were assessed and operationalised. Reported prevalence rates varied considerably between studies because of different methodological designs and limitations.

Our umbrella systematic review does not include single studies that have not previously been subject to a systematic review. This does not devalue such studies, but highlights where further research endeavours would be useful. Our umbrella approach has the advantage of being suitable to answer the research questions we posed in one report.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review include its broad reach, the prospective registration of the review protocol, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, a comprehensive search strategy including searching multiple databases, and duplicate study selection and data extraction, and quality assessment. The review is limited by excluding papers not written in English. Our review was of systematic reviews only; hence, it does not include any physical conditions that have not been subject to systematic review.

Implications

People with ASD experience more comorbid physical conditions than other people (although we draw no conclusions on shared aetiologies as we did not investigate that). Clinicians require heightened awareness of these high rates of comorbidities in order to improve assessments and diagnoses so that people with ASD can receive the best possible healthcare and support they require. Some of their comorbidities are likely to compound health assessments and interventions if health professionals are unwary of their existence, such as sensory impairments, given the communication needs that people with ASD already experience. Other comorbidities, such as obesity, if not addressed, can lead to an array of other conditions, disadvantages and early death. Given the impact that ASD can have on the individual, it is essential that all other, potentially modifiable health conditions are identified and managed to ensure that people with ASD achieve their best outcomes.

Future research

Comorbid physical conditions occur more commonly in people with ASD compared with the general population, but the evidence is limited. Given that physical conditions can have substantial bearing on function, and quality of life, further robust research is needed. The prevalence of conditions and their associations needs to be more firmly established, including for physical conditions that have to date received little attention. This would form a basis from which a better understanding of the long-term impact on quality of life could be gained, a start towards improved understanding of causation, and development of interventions to improve health. Further studies are also warranted on physical conditions commonly diagnosed in the general population, such as cancers, cardiovascular disorders and on physical comorbidities in ageing populations, to investigate how they have an impact on people with ASD. This in turn will allow for informed decision-making around healthcare, service commissioning and provision for people with ASD.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable, as no new data were collected (all referenced studies are in the public domain).

Author contributions

E.R. and S.-A.C. jointly conceived, designed and conducted the study, interpreted data and wrote the first manuscript. K.D. double rated papers, and contributed to interpretation of data. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Medical Research Council (Mental Health Data Pathfinder Award, grant number MC_PC_17217).

Declaration of interest

S.-A.C and E.R. report grants from UK Medical Research Council, during the conduct of the study.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.167.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.