Introduction

Background

People exposed to adversities (including experiences of sexual, physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and bullying) in childhood (e.g. Varese et al., Reference Varese, Barkus and Bentall2012a) or adulthood (e.g. Shevlin et al., Reference Shevlin, O'Neil, Houston, Read, Bentall and Murphy2013), are more likely to experience psychotic symptoms such as auditory verbal hallucinations. Auditory verbal hallucinations or voices are understood to result from a person confusing their own internal experience (thoughts or inner speech) with external events such as hearing someone speak (Bentall, Reference Bentall1990). The exact mechanisms responsible for this ‘misattribution’ are still debated in the literature (e.g. Brookwell et al., Reference Brookwell, Bentall and Varese2013) but dissociation, either at the time of the trauma or in response to current cues or reminders of past trauma, could increase this confusion between inner and outer experience, making voice experiences more common (Pilton et al., Reference Pilton, Varese, Berry and Bucci2015).

Whilst trauma is increasingly understood as an important contributory factor for psychotic experiences and voice-hearing, there is less consideration of how to treat features, and the consequences, of trauma in cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for psychosis manuals (e.g. Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Frame and Larkin2003b; Kingdon and Turkington, Reference Kingdon and Turkington1994). To address this gap a number of case studies (Callcott et al., Reference Callcott, Standart and Turkington2004; Hamblen et al., Reference Hamblen, Jankowski, Rosenberg and Mueser2004), case series (Callcott et al., Reference Callcott, Dudley, Standardt, Freeston, Turkington, Hagen, Turkington, Berge and Grawe2010; Keen et al., Reference Keen, Hunter and Peters2017) and feasibility trials (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Hardy, Smith, Wykes, Rose and Enright2017) have been undertaken. A particularly valuable study used treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) including prolonged exposure and eye movement desensitization reprocessing (EMDR) for people with psychosis who also meet criteria for PTSD (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh and Van Minnen2015). Both treatments reduced PTSD symptoms but notably had a greater effect on delusions than on voices, and only 55% of the sample had psychotic symptoms at the time of entry to the study. So, whilst encouraging, research is needed to understand how best to target and treat psychotic symptoms and particularly voices, in the context of trauma (e.g. Sin et al., Reference Sin, Spain, Furuta, Murrells and Norman2015).

Trauma-focused therapy is important as the presence of PTSD symptoms in people with psychosis has been linked to more severe psychotic symptoms, poorer response to anti-psychotic medication and worse outcomes (e.g. Hassan and De Luca, Reference Hassan and De Luca2015). However, a relatively small proportion of people with psychosis meet criteria for PTSD and core PTSD symptoms such as cognitive/behavioural avoidance, hyperarousal and intrusions/relieving represent only a sub-set of the possible consequences of traumatic life experiences that could influence psychosis vulnerability and maintenance. Consequently, the high prevalence of trauma and dissociative experiences among psychotic patients with voices highlights the need to offer psychological interventions targeting these potentially disabling experiences. However, as noted, dissociation is rarely addressed in manualized CBT interventions for psychosis. Dissociation is a particularly important process to address as in clinical populations it can include disabling experiences of depersonalization and derealization, as well as the identity alteration and dissociative amnesia observed in the severe dissociative disorders (Waller et al., Reference Waller, Putman and Carlson1996).The acceptability of cognitive behavioural change strategies for the management of dissociative experiences, and the ‘added value’ of considering dissociation in the context of CBT for distressing voices interventions has not been carefully examined to date. The current case study, part of a larger case series (F. Varese et al., in preparation) examined the impact of a CBT approach to the treatment of voices (Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Frame and Larkin2003a) specifically modified to include therapeutic techniques suitable for individuals with trauma and dissociative experiences (Kennerley, Reference Kennerley1996; Larkin and Morrison, Reference Larkin, Morrison, Larkin and Morrison2005; Newman-Taylor and Sambrook, Reference Newman-Taylor, Sambrook, Kennedy, Kennerley and Pearson2013). The aim of the current report is to illustrate the process of therapy with one of the participants in the study.

Aim

The primary aim of this intervention was to reduce the distress associated with experiencing dissociation, and voices.

Method

Participant

Mary (a pseudonym) is a 30-year-old woman experiencing her first episode of psychosis. She reported hearing voices for over 12 months, and reported them as occurring daily and being very distressing. She was diagnosed as suffering with a psychotic disorder with social anxiety. She was prescribed Quetiapine.

Procedure

This case report is part of a larger case series (n = 19) gathering preliminary data as to whether a modified CBT protocol can produce symptom relief for dissociative experiences, voices and trauma-related symptoms in voice-hearers with diagnoses of psychosis and a history of interpersonal traumatic experiences (F. Varese et al., in preparation). Participants met a number of inclusion criteria including: ICD-10 diagnosis psychotic disorder or meeting entry criteria for an Early Intervention in Psychosis service; history of voice-hearing for a minimum of 6 months; report hearing voices daily that were distressing; and clinical levels of dissociation. Importantly, participants had to identify voices or dissociation as a key presenting issue and something that they wanted help with.

Participants then received up to 24 sessions of treatment. The first 12 sessions focused on helping manage voices, and dissociation in order to reduce frequency and/or distress associated with these experiences. The latter 12 sessions focused on understanding and processing trauma experiences using imagery modification, imagery re-scripting and exposure to trauma memories (full details of the inclusion criteria and treatment are available from F. Varese).

Measures

The participant met an independent researcher to complete standardized measures listed below on four occasions: prior to treatment, approximately 3 months after the onset of therapy (at 12 sessions), at the end of therapy (at 24 sessions), and at 6-month follow-up.

The standardized measures included:

The Dissociative Experiences Scale, time bound (DES-t; Carlson and Putnam, Reference Carlson and Putnam1993) is a 28-item questionnaire assessing the frequency with which participants have had particular dissociative experiences during the past month. Respondents select a percentage ranging from 0 to 100% to indicate how frequently each item is experienced. The overall DES score is obtained by averaging the 28 item scores, yielding a score ranging from 0 to 100. Scores above 20 suggest the presence of frequent dissociative experiences, possibly suggestive of pathological levels of dissociation, whereas scores below 10 fall within the normal range of dissociative experiences (Carlson and Rosser-Hogan, Reference Carlson and Rosser-Hogan1993). However, as noted, we have adapted the measure to focus only on the last month, which may affect the reliability and validity of the measure.

The auditory hallucinations subscale of the Psychotic Symptoms Rating Scale (PSYRATS-AH; Haddock et al., Reference Haddock, McCarron, Tarrier and Faragher1999) is a widely used interview assessing physical, cognitive and emotional features of the auditory hallucinations experienced by the respondent in the week preceding the interview. The scale has demonstrated good validity and reliability in previous studies with first episode psychosis (Drake et al., Reference Drake, Haddock, Tarrier, Bentall and Lewis2007). Recently, a voice related distress scale has been identified based on five items from the PSYRATS and is recommended for use in therapy trials so it is also reported here (Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Jung, Hwang, Yin, Taylor, Menon and Erickson2014)

The Impact of Events Scale Revised (IES-R; Weiss and Marmar, Reference Weiss, Marmar, Wilson and Keane1997) is a 22-item self-report measure that assesses subjective distress caused by traumatic events. Respondents identify a specific stressful life event and then indicate how much they experienced hyperarousal, intrusive experiences and avoidance in relation to the event during the past 7 days on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 4 = extremely). A score of 24 or above indicates that PTSD is a concern, 33 or more and there is probable PTSD (Creamer et al., Reference Creamer, Bell and Falilla2002).

The Interpretation of Voices Inventory (IVI; Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Wells and Nothard2002) is a 26-item questionnaire assessing three separate types of voice appraisals: positive beliefs about voices (‘They help me to cope’), metaphysical beliefs about voices (e.g. ‘They mean I am possessed’), and beliefs about loss of control (‘They will make me lose control’). Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 4 = very much so). Higher sub-scale scores indicate higher endorsement of specific types of voice appraisals. The IVI has been found to be reliable and valid in previous studies with voice-hearers with psychosis (Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Turkington, Pyle, Spencer, Brabban, Dunn, Christodoulides, Dudley, Chapman, Callcott, Grace, Lumley, Drage, Tulley, Irving, Cummings, Byrne, Davies and Hutton2014).

The short Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond, Reference Lovibond and Lovibond1995) is a 21-item questionnaire designed to assess emotional distress, including symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress. Participants rate the extent to which they experienced each of the symptoms described in the items in the past week on a 5-point Liker scale (0 = did not apply to me at all; 4 = applied to me very much, or most of the time). Higher scores indicate greater levels of distress.

The Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR; Neil et al., Reference Neil, Kilbride, Pitt, Nothard, Welford, Sellwood and Morrison2009) is a 15-item self-report questionnaire assessing perceived recovery from psychosis-related difficulties. Higher scores indicate greater recovery.

The short-form of the CHoice of Outcome In CBT for psychosEs (CHOICE; Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Sweeney, Williams, Garety, Kuipers, Scott and Peters2010), is a service user-led outcome measure developed to evaluate outcomes for CBT for psychosis and assess therapy-related goals. Higher scores indicate greater benefit.

Session-by-session measures

At each therapy session, a short self-assessment form consisting of 12 items adapted from the PSYRATS, IVI and the DES was completed to monitor variations in voices frequency, distress, perceived control and dissociative experiences over the course of therapy (see copy in Appendix).

Ethical approval

A favourable opinion was received from an NHS ethics committee, and the project was registered with the local NHS Trust Research and Development Department. The participant gave informed consent for participation in the study and for information to be included within the write-up of this study. To protect confidentiality, non-essential details have been changed or removed. The write-up was shared with the participant prior to submission and feedback was incorporated into the final version.

Presenting issues

At assessment, Mary described her main difficulties as distressing voices, dissociative phenomena and panic. She described hearing two voices: one offering supportive and encouraging comments, the other being negative and derogatory, often commanding her to harm herself or others. The voices occurred daily, and could last for hours. Mary believed she heard voices as she was being punished by a deity and believed the voices were a sign she was losing control; she held these beliefs with 100% conviction. As a consequence of the distress of the voices, Mary would feel scared and would dissociate for hours at a time. Her scores on the PSYRATS and DES at baseline (see Table 1) indicate high levels of voices and dissociation.

Table 1. Total (and mean) scores and RCI for the standardized measures

DES, Dissociative Experiences Scale (norms derived from Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer and Bentall2012b; supplementary data). PSYRATS-AH, the Psychotic Symptoms Rating Scale Auditory Hallucination sub-scale (norms derived from Varese et al., Reference Varese, Morrison, Beck, Heffernan, Law and Bentall2016). Distress scale calculated according to Woodward et al. (Reference Woodward, Jung, Hwang, Yin, Taylor, Menon and Erickson2014). IES, the Impact of Events Scale Revised (cut-offs derived from Creamer et al., Reference Creamer, Bell and Falilla2002). DASS, the short Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (norms from clinical group from Varese et al., 2016; controls, Henry and Crawford, Reference Henry and Crawford2005). IVI, Interpretation of Voices Inventory (norms based on Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Nothard, Bowe and Wells2004). QPR, the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery. CHOICE, the short-form of the Choice of Outcome in CBT for Psychoses.

Conceptualization

In terms of her trauma history, Mary described a difficult childhood reporting experiences of neglect, physical and emotional abuse, and bullying. Through the conceptualization [based on the CBT psychosis model of Morrison et al. (Reference Morrison, Renton, Dunn, Williams and Bentall2003b); see Fig. 1] Mary recognized how post-traumatic intrusions and critical voices were trauma reactions and that her main response was to dissociate, a skill that she had developed as a child as way of coping with unbearable situations. It was hypothesized that Mary's experience of early abuse and bullying had led to the development of beliefs that the world is a dangerous place and others can hurt you and are untrustworthy. As a consequence of these beliefs she had developed strategies that would prevent others becoming close to her. This was an understandable and protective response given her childhood and the unpredictable environment.

Figure 1. Conceptualization of Mary's presenting issues

The formulation identified developmental as well as maintenance factors and although Mary could see the benefit of dissociating when she was younger, she recognized that engaging in dissociative phenomena as an adult was reinforcing the idea she was losing control and preventing her from processing the trauma and regulating affect.

Course of therapy

Therapy initially focused upon targeting dissociation. After providing the rationale for this approach, specific grounding techniques such as smelling perfume and looking at photographs of a key parental figure were demonstrated in session to help Mary gain the skills to be able to be in the present. Mary could refocus her attention upon the environment around her and therefore less upon her internal experiences and consequently, ‘drifting off’ reduced. Gaining control over the dissociative phenomena and working through maintenance formulations allowed Mary to re-appraise the voices. She no longer believed that she was being punished by a deity, moreover she believed that these were her own thoughts as a consequence of her early experiences and not a sign that she was losing control. As this work continued over the initial 12 sessions, she reported having full control over the dissociative phenomena and was able to ‘switch it on and off’ as she required.

Around this time, Mary was exposed to situations involving active and serious threat from others, and she did not rely on dissociation to cope. With the increased control over dissociation she reported increased frequency of voices, and intense and distressing post-traumatic intrusions. She experienced daily flashbacks and although she could ground herself, these were distressing and she appraised them as happening now (100%) and that she felt she was going to die (100%). Perhaps owing to the lack of reliance on dissociation, Mary began to feel overwhelmed and struggled to deal with any emotion that she was experiencing. Mary described feeling that ‘the floodgates have opened’ and therefore it was necessary to spend time normalizing her current experiences through developing surveys regarding emotion and through self-disclosure. Throughout these sessions, emotional regulation skills such as listening to sad music or watching a funny movie were practised to help Mary tolerate and manage affect.

The second phase of the treatment deliberately involved exposure to trauma memories to allow emotional reprocessing and with Mary imagery modification helped to change the images of specific physical assaults. Mary could change the image which reduced the emotional intensity and led to a re-appraisal of the image. She reported feeling empowered by this, having control over the post-traumatic intrusions and no longer feeling distressed by them. Similarly, in the latter stages of treatment (sessions 14–22) more attention was paid to the longitudinal elements of the formulation. This allowed Mary to see that it was understandable that she had developed these views about herself, others and the world around her, given the difficulties and adversities she had experienced.

Data analytic strategy

The pertinent session-by-session measures were graphed and subjected to visual inspection and, where helpful, for the standardized measures where possible the Leeds Reliable Index change calculator was used to calculate reliable (Morley and Dowzer, Reference Morley and Dowzer2014) and clinically significant change (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) from baseline to end of treatment (accessed at http://medhealth.leeds.ac.uk/info/2692/research/1826/research/2). Relevant norms for each calculation are reported in Table 1.

Results

Session-by-session measures

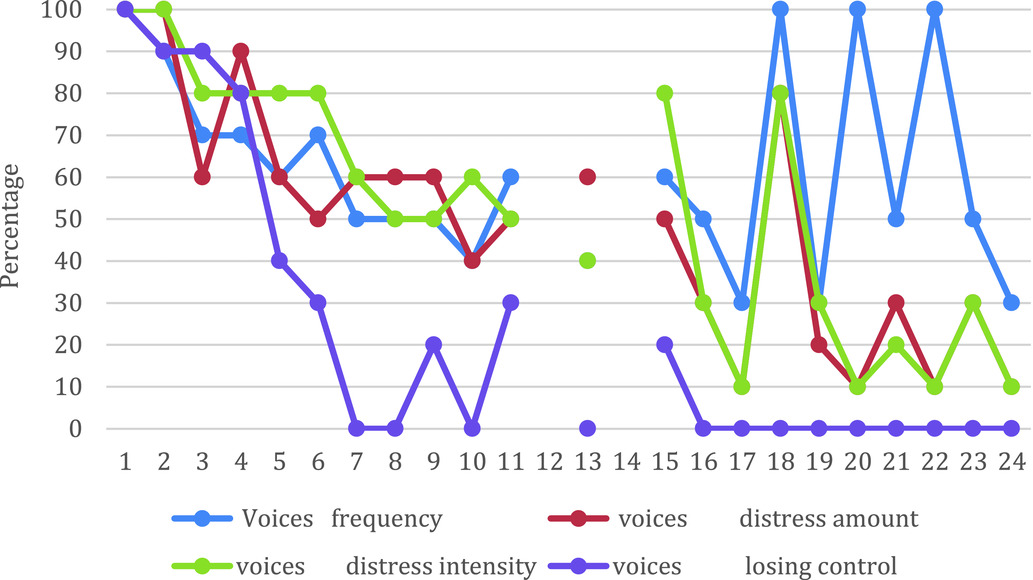

As can be seen on the graphs that show change in frequency/distress/conviction over the course of treatment there were reductions in voice frequency and voice distress over the initial 10 sessions (Graph 1). As noted about mid-way through treatment, Mary's voice frequency increased but notably the voices were not appraised as a sign that she was losing control, and hence, the distress was quite low, and independent from frequency.

Graph 1. Session ratings of voice frequency, distress (amount, intensity) and appraisal of voice as the person is losing control

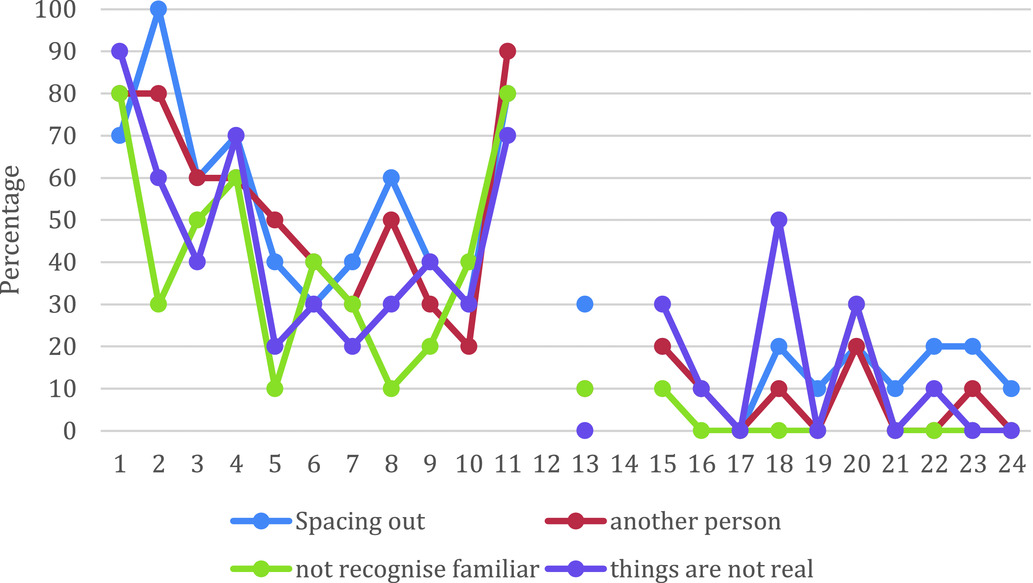

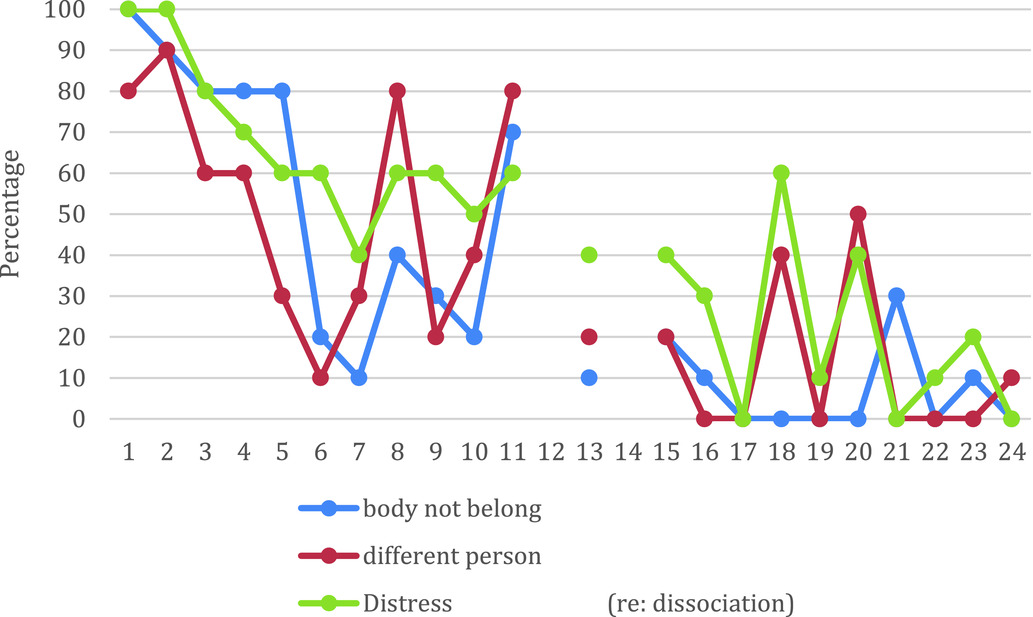

By Mary's account there were also notable and sustained reductions in frequency and distress associated with dissociation (see Graphs 2 and 3). The graphs show the scores from the six dissociation variables and the measure of dissociation distress (see Appendix 1 for the original items).

Graph 2. Session ratings of dissociation frequency and amount

Graph 3. Session ratings of dissociation frequency and distress

In terms of the standardized measures, Mary's scores are reported in Table 1. These showed significant improvements during treatment on measures of the primary targets of therapy of dissociation and voice hearing and voice hearing distress. There were also marked improvements in terms of mood and in perceived recovery and achievement of goals. At 6-month follow-up there was evidence of continued improvements in dissociation, trauma symptoms, and in perceived recovery; however, voices experiences were reported as the same as at the start of treatment, although distress was still lower than at the start of treatment.

Discussion

This targeted, theoretically driven approach appears to have led to substantial reductions in dissociation, and voice hearing frequency, and distress at the end of treatment. The changes are demonstrated on both standardized measures and session-by-session measures. The change on the session-by-session measures is consistent with the theory that reductions in dissociation will reduce voice impact. The method by which reductions in dissociation led to reductions in voice experiences is unclear, but it is possible that less reliance on dissociation allowed greater opportunity to challenge appraisals about the controllability and origin of the voices. The sustained improvement of dissociation would suggest that the voice experiences would not return, but this was not the case at 6-month follow-up where there was an increase in voice difficulties but notably distress was still lower than at the start of therapy. Nevertheless, it may be that the duration of treatment was inadequate or that other approaches that help a person change the relationship with their voices may have been helpful (Longden et al., in press).

We have to be alert to the possibility that the intervention itself led to the period of worsening of symptoms (around session 12). Therapists have had understandable reservations about exposure-based therapies in case they lead to de-stabilization, and service users can experience initial worsening of PTSD symptoms when undertaking eventually beneficial exposure-based interventions. However, we would attribute the worsening in this instance to the genuine and current threat Mary unexpectedly experienced during the treatment. It is obvious that we need to avoid over-interpreting this one case study, and the findings demand replication in larger scale studies (F. Varese et al., in preparation). We are also aware that we have adapted the DES to focus on the past month, and we cannot assume that the demonstrated psychometric properties apply to this adapted version. However, even with reservations in mind about the temporary increase in voices, given the improvement at the end of therapy, it provides some evidence that we can target dissociation and voices in people with psychosis.

Van Minnen et al. (Reference van Minnen, van der Vleugel, van den Berg, de Bont, de Roos, van der Gaag and de Jongh2016) have shown that in people with psychosis with high levels of dissociation there is no requirement for a period of stabilization before treating the trauma. The focus of this work was slightly different to this in that dissociation was seen to be a central process in the experience of voices and that strategies to manage dissociation such as the use of grounding was deemed essential. Previous work on CBT for trauma in psychosis has emphasized the need for an element of exposure to a traumatic experience for there to be value (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Hardy, Smith, Wykes, Rose and Enright2017). In this current case report, there was direct exposure to past trauma, and imagery modification appeared to be valuable in this case example, as well as cognitive restructuring of the meaning of the experiences.

Summary of main points

(1) People with psychosis report high levels of trauma and dissociation.

(2) These processes may be important in the experience of voices but are given scant attention in treatment manuals.

(3) This case study reports the direct targeting of dissociation and voice hearing in a person with a history of adversity and trauma.

(4) The approach appeared to be acceptable and helpful, and led to changes in voice experiences and dissociation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Louise Maule and Helen Spencer who helped with recruitment and assessments in this case study. Negar Khozoee assisted with preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

R.D., D.T. and T.M. have received royalties from CBT texts and R.D., T.M., D.T., M.D. and L.M. for workshops on the topic of CBT. The other authors have no conflict of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statements

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA. A favourable opinion was received from an NHS ethics committee (REC reference number 13/NW/0703), and the project was registered with the local NHS Trust Research and Development Department. The participant gave informed consent for participation in the study and for information to be included within the write-up of this study. To protect confidentiality, non-essential details have been changed or removed. The write-up was shared with the participant prior to submission and feedback was incorporated into the final version.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Learning objectives

(1) To understand the way that trauma can contribute to psychosis and especially how dissociation may be important in voice hearing.

(2) To understand how to develop and share a formulation with a service user that incorporates a role for dissociation, and trauma in voice hearing.

(3) To understand how dissociation and voice hearing can be targeted in CBT for psychosis.

(4) To understand the responsiveness of this sub-group to CBT modified to work with dissociation and trauma.

Appendix 1: Session-by-session monitoring form

Please answer the following questions about the voices you experienced in the past week

Over the past week, how often did you have experiences like. . .

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.