Introduction

Clinical supervision (CS) is an integral part of the working life of a cognitive behavioural therapist. It provides an opportunity for qualified supervisees and those in training to reflect upon their clinical skills and for supervisors to assist in skill development and refinement (Liness et al., Reference Liness, Beale, Lea, Byrne, Hirsch and Clark2019; Pugh and Margetts, Reference Pugh and Margetts2020) and the monitoring of safe and ethical practice (Milne, Reference Milne2017). CS has been defined as ‘the formal provision, by senior/qualified health practitioners, of an intensive, relationship-based education and training that is case-focused and which supports, directs and guides the work of colleague/s (supervisees)’ (Milne, Reference Milne2007; p. 440). It is also a mandatory requirement for achieving and maintaining cognitive behavioural therapist (CBT) practitioner accreditation with the British Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) in the United Kingdom (Armstrong and Freeston, Reference Armstrong, Freeston and Tarrier2006; Corrie and Lane, Reference Corrie and Lane2015).

Given the importance that is placed on supervision by training institutions, employers, governing bodies and therapists themselves it is of concern that supervision in everyday practice does not always mirror the recommendations in the expert literature (Alfonsson et al., Reference Alfonsson, Spännargård, Parling, Andersson and Lundgren2017; Townend et al., Reference Townend, Iannetta and Freeston2002; Weck et al., Reference Weck, Kaufmann and Witthöft2017: Younge and Campbell, Reference Younge and Campbell2013). For example, an online survey of 170 BABCP-accredited CBT therapists carried out by Townend et al. (Reference Townend, Iannetta and Freeston2002) found that only 18% of respondents reviewed video or audio footage of therapy sessions with their supervisor. Other ‘active’ supervision methods such as role play were also comparatively uncommon (19%) and the direct observation of skills (i.e. supervisor sitting in during a therapy session) was even rarer (6%). In other studies, an over-reliance on case discussion has been identified (e.g. Weck et al., Reference Weck, Kaufmann and Witthöft2017; Younge and Campbell, Reference Younge and Campbell2013).

Supervisory drift

One of the potential consequences of inconsistent supervision practices is ‘supervisory drift’ (SD) (Grey et al., Reference Grey, Deale, Byrne, Liness, Whittingham and Grey2014; Pugh and Margetts, Reference Pugh and Margetts2020). Whilst the issue of ‘therapist drift’ has received some attention in the extant CBT literature (Rameswari et al., Reference Rameswari, Hayes and Perera-Delcourt2021; Waller Reference Waller2009), supervisory drift remains poorly understood in terms of its definition, prevalence, reasons for occurrence, identification in routine practice and potential solutions. This paper is an attempt to summarise what is known about this topic and to hypothesise potential causal mechanisms by drawing on existing supervision and interpersonal processes literature. It is also the intention to provide supervisors, supervisees and those that supervise supervisors, referred to henceforth as ‘meta-supervisors’ (Newman, Reference Newman2013) with a resource to reflect on their practice or use of supervision.

Section 1 seeks to assist supervisors and supervisees in recognising the hallmarks of good quality supervision; in other words, how it should be done according to expert recommendations and the limited evidence base that exists thus far. By drawing upon general supervision literature and evidence-based CBT supervision, readers will be able to reflect on their own supervision practices and begin to identify indicators of drift. Section 2 will introduce a range of contextual and pre-disposing factors that both supervisor and supervisee bring with them into the supervisory relationship and which are hypothesised to play a role in the origins or maintenance of SD. By utilising the literature on therapist skill development, therapist drift and therapist schemas, a number of maladaptive assumptions involved in supervisory drift are hypothesised to lead to problematic supervisor and supervisee cognitions, emotions and behaviours (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006; Leahy, Reference Leahy2001; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Leck and Choudhri2009; Waller, Reference Waller2009). The term ‘supervision dyads’ will be used to refer to the relationship between supervisor and supervisee, whilst also recognising that certain formats such as peer supervision often include more than two parties. Section 3 will then introduce a novel interpersonal process model of supervision to assist in formulating difficulties by using a number of fictional case studies to illustrate this. Finally, Section 4 will offer a range of potential solutions for how drift can be rectified.

Section 1: Defining and recognising supervisory drift in everyday practice

Little has been written specifically on drift within CBT supervision, with a search of the electronic databases PsycARTICLES, Medline, CINAHL and Academic Search Complete using the terms ‘cognitive behavioural therapy’ and ‘supervisory drift’ generating only one result. Pugh and Margetts’ (Reference Pugh and Margetts2020) summary of action-based methods is the nearest to a clear definition where they suggest that supervisory drift ‘refer to instances in which core components of supervision (e.g outcomes monitoring, direct observation, mutual feedback) are omitted, avoided or deprioritised, resulting in a gap between supervisory theory and practice’ (p. 5). Hand searching by the author also found a Milne et al. (Reference Milne, Leck and Choudhri2009) case study on collusion which helps to provide a useful example of one way that drift may present in clinical practice. Using Pugh and Margetts (Reference Pugh and Margetts2020) as a working definition, this section will seek to define what these core components are in everyday supervision and how they might be intentionally or unintentionally omitted.

The core components of supervision

Kadushin (Reference Kadushin1968), writing in relation to social work supervision, was one of the first to offer a definition of the main purpose of supervision. Kadushin suggested that it serves three functions which are educative, supportive and managerial. Proctor (Reference Proctor1994), applying these concepts to the counselling arena, described them as normative, formative and restorative. Within the realm of psychotherapy, the aim of the supervision process is to produce therapists that have ‘confidence, competence and creativity’ (Proctor, Reference Proctor1994; p. 309). In the process of fostering confident, competent and creative supervisees, the supervisor is likely to encounter doubt of their own and their supervisees’ abilities, ethical challenges, organisational pressures and role conflicts, differences of opinion, training background, impasses and at times, ruptures in the supervisory relationship (Moorey and Byrne, Reference Moorey, Byrne, Moorey and Lavender2019; Pugh, Reference Pugh2019a; Watkins, Reference Watkins2020; Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020).

This suggests that on a day-to-day basis, the role of a clinical supervisor is one which requires a dynamic approach, where several ‘hats’ need to be rotated at any given time in response to the challenges that emerge. A competent supervisor will therefore be aware of when tensions might arise between the need to attend to restorative aspects of the role whilst maintaining a focus on the normative and formative elements. Based on these concepts, it is hypothesised that drift may be evident when there is too little focus on one of these domains (e.g. too little formative aspects) or too much of a restorative focus (e.g. allowing the supervisee to ‘let off steam’ about their organisation).

Defining good quality CBT supervision

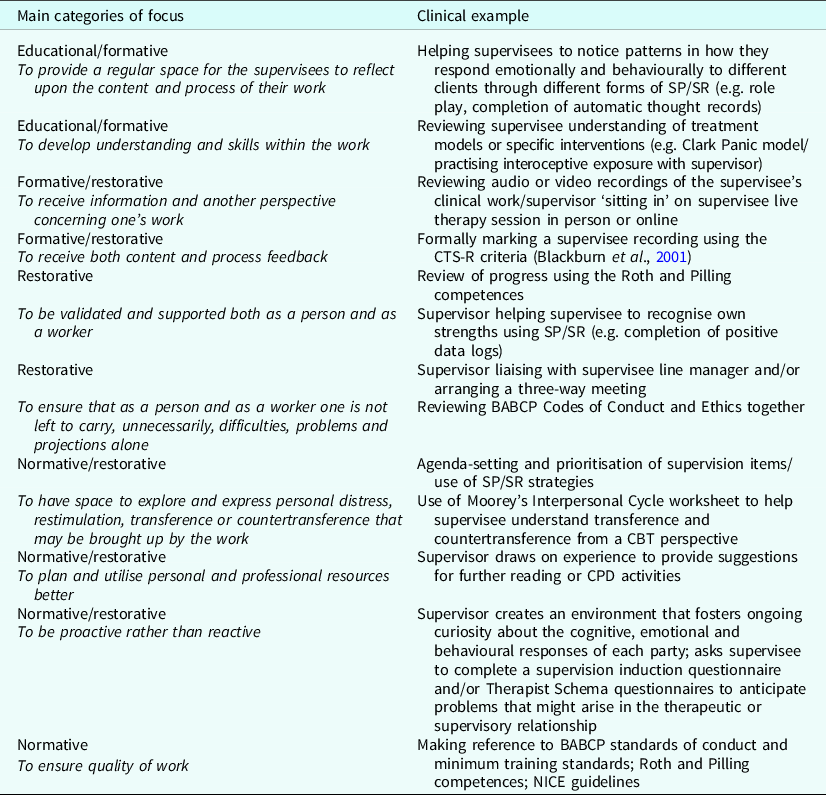

Historically there has been a reliance upon expert consensus (Kennerley et al., Reference Kennerley, Kirk and Westbrook2017) and ‘reflexivity’ (Milne, Reference Milne2008) whereby the process of supervision should mirror the process of therapy, with a clear and collaborative agenda, defined problems, specific goals and a review of learning (Beck and Beck, Reference Beck and Beck1995; Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Ballantyne and Scallion2015). To illustrate this in action, Gordon (Reference Gordon2012) produced a helpful ‘ten steps to supervision’ paper and Pretorius (Reference Pretorius2006) conducted a literature review to establish some markers of best practice with his findings indicating that good quality supervision would include three main elements: (i) a recognised format, (ii) sessions tailored to the experience of the therapist, and (iii) the cognitions and emotions of supervisees would be explored. Examples of normative, formative and restorative duties that a CBT supervisor may undertake in line with the Gordon and Pretorius recommendations are captured in Table 1 adapted from a format presented originally by Hawkins and Shohet (Reference Hawkins and Shohet2000).

Table 1. Primary foci of CBT supervision (adapted from Hawkins and Shohet, Reference Hawkins and Shohet2000)

Evidence based clinical supervision (EBCS)

Replicating many of the principles of CBT therapy has an appeal due to its apparent simplicity; however, there is the potential to overlook the key differences between the role of therapist and supervisor (Prasko et al., Reference Prasko, Vyskocilova, Slepecky and Novotny2012) and supervisee and client (Milne, Reference Milne2017). Furthermore, without a testable theory as to how supervision works, it is difficult to argue for the concrete benefits of certain supervision methods (e.g. role play) over others (e.g. case discussion). The work of Milne and colleagues (e.g. James et al., Reference James, Milne, Marie-Blackburn and Armstrong2006; Milne and Dunkerley, Reference Milne and Dunkerley2010; Milne and Reiser, Reference Milne and Reiser2012) has been instrumental in developing a systematic fidelity framework that includes both a theory of how supervisees learn and an instrument to test adherence to evidence-based supervision (Johnston and Milne, Reference Johnston and Milne2012; Milne, Reference Milne2017).

Incorporating adult learning theory (e.g. Kolb, Reference Kolb1984) and through applying evidence-based principles to our understanding of supervision (Milne and Dunkerley, Reference Milne and Dunkerley2010; Milne and James, Reference Milne and James2000), EBCS provides the most robust framework available for measuring supervisor competence (Milne, Reference Milne2017). The supervision process is likened to supervisor and supervisee as two cyclists on a tandem bicycle with the front wheel representing the supervisor behaviours and the rear wheel capturing the experiential learning cycle (Milne and Dunkerley, Reference Milne and Dunkerley2010). Within EBCS, successful supervision can be identified through the supervisor taking the supervisee around the experiential learning cycle (acting, reflecting, conceptualising, experimenting and experiencing) during a supervision session. The Supervision Adherence and Guidance Evaluation (SAGE) is a tool that can be used to assess this process (the ‘supervisee learning cycle’). It also measures the skills that are displayed by the supervisor (the ‘supervison cycle’) and a range of ‘common factors’ such as the ability to successfully relate to the supervisee, collaborate with them on agreed goals and effectively manage the session. It has been shown to have good content and construct validity (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011).

Potential characteristics of drift

Utilising SAGE

SAGE appears to be the only recognised tool for measuring CBT supervisor skill and therefore is a highly valuable facet of CBT supervision and more specifically in detecting signs of drift. Using the Dreyfus scale and Likert ratings similar to the CTS-R (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) it is used to measure the presence or absence of a range of supervisor and supervisee behaviours as featured in the tandem model (Milne and Dunkerley, Reference Milne and Dunkerley2010) and as with the CTS-R, a cut-off score is given to indicate a minimal degree of supervisor competence. The SAGE can be used during Supervision of Supervision (SoS) to watch a video recording of a supervision session and mark the supervisor against the different criteria. It could also be used as a self-supervision activity where a supervisor may watch or listen to a recording of their own supervision session where they mark their performance formally or informally. Examples of where a supervision session indicates signs of drift using SAGE include a failure to demonstrate adequate teamwork with the supervisee (the ‘common factors’), little evidence of focusing the supervisee by setting an agenda (the ‘supervision cycle’) and an absence of the supervisee reflecting on what they have learned during the session (the supervisee cycle) (Milne and Reiser, Reference Milne and Reiser2014).

How prevalent is supervisory drift?

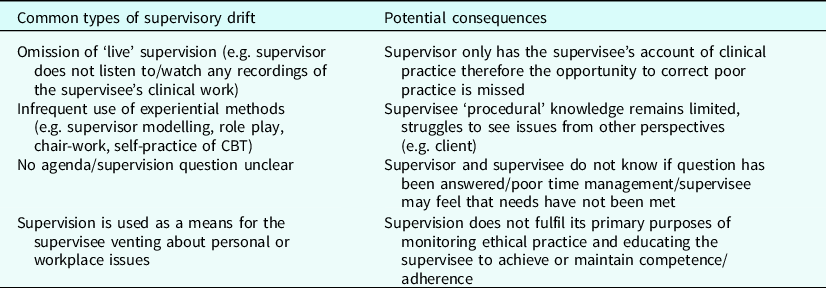

Having established a benchmark for high quality, effective supervision and a reliable means of measuring supervisor competence, we can consider that sub-optimal forms of supervision will be defined as those practices where experiential methods are avoided or deprioritised and form the basis of supervisory drift (Milne, Reference Milne2017; Pugh and Margetts, Reference Pugh and Margetts2020). Sub-optimal supervision can then be categorised as either ineffective (e.g. does not deliver on intended outcomes such as supervisee skill development) or harmful (e.g. there is a clear detrimental effect on the supervisee’s confidence or skill development) (Ladany et al., Reference Ladany, Mori and Mehr2013). Table 2 provides examples of sub-optimal forms of supervision that may indicate supervisory drift in practice and the potential consequences that may stem from this.

Table 2. Examples of sub-optimal forms of supervision

Ineffective or harmful supervision

Whilst drift and harm are not one and the same, it could be argued that they sit along a continuum of ineffective forms of supervision. Large scale surveys of supervisory practice are rare (e.g. Milne, Reference Milne2016; Townend et al., Reference Townend, Iannetta and Freeston2002), therefore the current prevalence of ineffective supervision is difficult to determine although recent research suggests that avoidance of ‘live’ supervision (e.g. audio or video recordings) continues to be an issue (Roscoe et al., Reference Roscoe, Taylor, Wilbraham and Harrington2019). Collusion between supervisor and supervisee to avoid mutually undesirable aspects of supervision such as viewing oneself on video may prevent crucial learning from occurring (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Leck and Choudhri2009).

Conversely, a number of supervision experts have written about the implications of poor supervision where harm may arise to the supervisee or their clients (e.g. Ladany et al., Reference Ladany, Mori and Mehr2013; Milne, Reference Milne2020). Harmful supervision per se is not the focus of this paper and therefore readers are directed to the recent work of Milne for a more thorough grounding.

Behaviours associated with the best and worst supervisors

In a study involving 128 participants, Ladany and colleagues (2013) identified behaviours that were suggestive of the best and worst supervisors. Supervisors that were highly rated by supervisees demonstrated high self-disclosure, interpersonal sensitivity and an agreement on the tasks of supervision, all of which resulted in a strong emotional bond. In contrast, the worst supervisors were perceived to lack technical and interpersonal skills, rarely utilised video or audio observation, and were punitive in their feedback to supervisees, all of which resulted in a weak supervisory alliance. Whilst not specific to CBT, it is likely that similar processes occur in all supervisory relationships (Watkins, Reference Watkins2020). Even if this does not amount to harm, ‘supervisees may be at risk of receiving supervision which is at best banal and at worst less effective than it could be’ (Pugh and Margetts, Reference Pugh and Margetts2020).

Section 2: Potential reasons for drift arising

The challenges in mandating specific supervision components

Whilst supervision is often highly rated by practitioners (Townend et al., Reference Townend, Iannetta and Freeston2002; Weck et al., Reference Weck, Kaufmann and Witthöft2017) and championed as being an essential activity by both organisations providing CBT (e.g. National Health Service) and leading figures within CBT (e.g. Padesky, 2006) the evidence base to support the proposed outcomes remains fairly weak (Alfonsson et al., Reference Alfonsson, Spännargård, Parling, Andersson and Lundgren2017; Grey et al., Reference Grey, Deale, Byrne, Liness, Whittingham and Grey2014). Roth and Pilling (Reference Roth and Pilling2008) state ‘the purpose of supervision should be to enhance client outcomes, but detecting a causal link is challenging, requiring that there is evidence that supervision impacts in some way on the supervisee, that this is translated into a change in their behaviours as therapists, and that this change improves outcomes’ (p. 5).

Client outcomes – the holy grail of supervision

A troublesome question for those that wish to determine good versus bad supervision is whether there are any measurable consequences to supervision which is for example, overly restorative? Where supervisors, trainers, managers and accrediting bodies can hold a therapist to account for failing to adhere to or demonstrate competence in a particular evidence-based model or treatment (e.g. Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) through the use of widely adopted measures such as the Cognitive Therapy Scale Revised (CTS-R) (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) or through a series of caseload reviews that indicate poor patient recovery, the same cannot be said for what should and should not be done in supervision. Research on supervisee satisfaction (Ladany et al., Reference Ladany, Mori and Mehr2013), therapist skill development (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006) supervisee learning (James et al., Reference James, Milne, Marie-Blackburn and Armstrong2006) and accrediting body regulations (e.g. BABCP) can loosely be used to define good quality supervision yet may be insufficient grounds to challenge a supervisor’s practice on the grounds of incompetence. Furthermore, the degree to which expert developed manuals and instruments influence routine supervisory practice remains to be seen (Gyani et al., Reference Gyani, Shafran, Rose and Lee2015; Milne, Reference Milne2016). From the author’s anecdotal experience, tools such as SAGE are not being applied routinely within supervision or Supervision of Supervision (SoS), which raises questions about the consistency and quality of CBT supervision.

When and where is drift most likely to occur?

Pugh and Margetts (Reference Pugh and Margetts2020) speculate that supervisory drift may occur due to limited supervisor knowledge (of supervision approaches including experiential methods), negative beliefs about these methods or their ability to utilise them, anxiety or shame around enactment, a desire to protect rather than risk the supervisory alliance through potentially challenging conversations and concerns about having the time to incorporate certain methods within a supervision session. This section seeks to expand on these ideas by hypothesising how a range of contextual, historical, intrapersonal and interpersonal factors may create the conditions under which supervisory drift develops. In addition to these reasons, the author proposes that a lack of familiarity with SAGE amongst CBT supervisors could be a significant factor, although further research is required to establish how widely it is used.

Contextual factors

The context in which supervision takes place might be an important factor to consider in the genesis and maintenance of drift. There is a dearth of research which captures how supervision is delivered and used outside of research trials (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Pilling and Turner2010). In randomised control trials (RCTs) supervision is often carried out by experts with considerable experience as clinicians and supervisors (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2008). Supervision is usually weekly and supervisees are closely monitored for their adherence to treatment protocols (Turpin and Wheeler, Reference Turpin and Wheeler2011). In contrast, BABCP only require accredited therapists to receive 90 minutes per month, supervisors might be peers or of a similar level of experience to their supervisees and research on therapist drift suggests that adherence to protocols is variable (Townend et al., Reference Townend, Iannetta and Freeston2002; Sherman, Reference Sherman2021; Waller, Reference Waller2009).

Furthermore, in routine clinical practice, service demands may lead to time pressures with an over-emphasis on the normative (case management) tasks at the expense of more reflective or experiential methods (e.g. Bennett-Levy and Thwaites, Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Gilbert and Leahy2007; Pugh and Margetts, Reference Pugh and Margetts2020; Scott, Reference Scott2018). Conversely, private practice may allow for less intrusive forms of supervisions yet at the same time create the conditions for supervision that becomes too relaxed, lacking the essential hierarchical component (Milne, Reference Milne2017).

During CBT training, the aims of supervision and the requirements of the supervisor and supervisee tend to be clear and rigorous. This reflects the demands of the training curriculum where training courses typically utilise competence measures such as the Cognitive Therapy Scale Revised (CTS-R) (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) and adhere to the BABCP minimum training standards (Liness et al., Reference Liness, Beale, Lea, Byrne, Hirsch and Clark2019). The challenge is that the role of supervision for qualified and experienced therapists is more open to interpretation owing to the fact that they may have less obvious formative or normative needs and there is less scrutiny than during training (Younge and Campbell, Reference Younge and Campbell2013). This opportunity for interpretation is frequently reported to be guided by the supervisor’s own experience as a supervisee rather than any formal supervision guidelines (Townend et al., Reference Townend, Iannetta and Freeston2002; Milne, Reference Milne2008; Younge and Campbell, Reference Younge and Campbell2013). Furthermore, this ambiguity might not be assisted by the absence of a unified model of supervisory practice (Armstrong and Freeston, Reference Armstrong, Freeston and Tarrier2006; Milne, Reference Milne2008).

Potential contributing factors

Pre-disposing factors – training and past experiences of supervision

It is hypothesised in this paper that both the supervisee and the supervisor enter the supervisory relationship with unique expectations of what supervision will entail and attitudes towards the ongoing purpose of supervision sessions. The format of supervision that one receives during their therapist training is likely to influence what one continues to expect from supervision in the future (Roscoe, Reference Roscoe2021a). For example, a supervisee that receives supervision which incorporates a range of methods such as self-practice of CBT methods, role-play, modelling, video feedback and case discussion is likely to expect future supervisors to offer these formats. Conversely, the supervisee who has experienced restricted methods may not know what they are missing and therefore have low expectations from future supervisors.

Supervisor cognitions

Supervisors enter into the supervisory relationship as they do any other relationship with a set of beliefs about themselves and the world (as Bennett-Levy terms ‘person-of-the-therapist’, 2006) and a set of beliefs about therapy (the ‘self-as-therapist’ schema) derived from their clinical knowledge and skills that they have accrued in their therapeutic practice. It is hypothesised henceforth that the personal and therapist ‘selves’ influence a ‘supervisor self’ (Corrie and Lane, Reference Corrie and Lane2015) which is derived from experiences of supervision (including but not limited to any supervisor training that has been attended, how they were and are supervised and the culture of supervision within the contexts in which they are employed).

It is not yet known which cognitions are specifically linked to supervisory drift (personal self, therapist self or supervisor self); however, there are likely to be parallels with those associated with therapist drift. For example, it has been suggested that many therapists find exposure-based activities aversive (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Farrell, Kemp, Blakey and Deacon2014), and given that supervisors are usually practising therapists themselves, individual beliefs held by the supervisor may also influence the direction and content of supervision, resulting at times in collusion with the supervisee to avoid mutually aversive aspects of treatment (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Leck and Choudhri2009). It has also been theorised that specific beliefs held by supervisors might influence the degree to which they retain fidelity towards evidence-based practice (EBP). For example, Simpson-Southward et al. (Reference Simpson-Southward, Waller and Hardy2018) found that when more diffuse cases of depression were brought to supervision the advice supervisors would give tended to drift from EBP.

Some supervisors may also feel uncomfortable with the normative functions of their role, for example raising concerns about safe, ethical or competent practice with their supervisees. This may reflect certain therapist schemas held by the supervisor, for example ‘need for approval’ (see Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006; Leahy, Reference Leahy2001). Such is their need to be liked by the supervisee that they may place too much emphasis on the restorative aspect of supervision and deprioritise normative and formative tasks.

Supervisee cognitions

As supervisory drift may also be supervisee-led, it is useful to consider what types of problematic supervisee cognitions could influence their decisions within supervision. A range of ‘personal self’ core beliefs may be activated within supervision (e.g. ‘I’m stupid’ in response to corrective feedback from a supervisor on their technical execution of an intervention such as a worry script),’therapist self’ rules and assumptions (e.g. ‘I must always know what I am doing’/’If I show my supervisor my weaknesses in my practice then they will judge me harshly’) and situation specific negative automatic thoughts (e.g. ‘The supervisor will see how rubbish I am at agenda setting if I agree to doing role-play with them’). Beliefs such as ‘The supervisor is always right’ might prevent a supervisee from suggesting a variation to how supervison is structured (e.g. being reluctant to suggest that the supervisor include more modelling in sessions).

Supervisor emotions

Newly appointed supervisors may feel anxious about being seen as knowledgeable enough to perform in the role (Corrie and Lane, Reference Corrie and Lane2016). They might also feel embarrassment or shame in relation to their own clinical work if they perceive that the supervisee is likely to criticise their level of skill during a modelling or role play task.

Supervisee emotions

Supervision, whether group or one-to-one, involves the supervisee having to let others see and evaluate their clinical work. This is likely to trigger a range of emotions such as anxiety (anticipatory) fear (during the session), shame (believing that the supervisor or peers can see how bad they are), embarrassment (at being the centre of attention) and sadness (where ruminative self-critical thoughts may arise post-supervision). Failing to normalise and name these emotions within supervision could lead to supervisees engaging in a range of safety-seeking behaviours to protect themselves (see Milne et al., Reference Milne, Leck and Choudhri2009).

Supervision-interfering behaviours

Just as therapist and client may knowingly or unknowingly engage in therapy-interfering behaviours (Waller, Reference Waller2009), supervision dyads may hold within them a range of supervision-interfering behaviours that are either supervisor-led, supervisee-led or a result of collusion between both parties (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Leck and Choudhri2009). Kadushin (Reference Kadushin1968) proposed that supervisors and supervisees may engage in various ‘games’ within the supervision process, as highlighted in Table 3.

Table 3. Supervisor and supervisee gameplay adapted from Delano and Shah (Reference Delano and Shah2006)

Described as ‘recurrent interactional incidents between supervisor and supervisee that have a payoff for one of the parties in the transaction’ (p. 55) these games are not necessarily in the immediate awareness of each party; however, their presence may lead to ineffective supervision or ruptures emerging when one party refuses to ‘play’. Gameplay could be considered as a means of protecting either or both parties from difficult cognitions and emotions that may arise within supervision.

To summarise, it is hypothesised that a range of pre-disposing factors including one’s history of being supervised and the context in which supervision is delivered may give rise to a number of problematic supervisor and supervisee cognitions and emotions that are perpetuated through the use of gameplay within supervision. This may include attitudes towards the use of certain aspects of supervision such as role play, modelling or video feedback. Drift may arise or continue due to these cognitions, emotions and behaviours going unnoticed or unchallenged. The next section will provide examples of how supervisors, supervisees or meta-supervisors can identify signs of drift in routine practice.

Section 3: Getting back on track in supervision using a bespoke formulation

Identifying drift in routine practice

Recognising and responding to drift is the responsibility of all parties involved in supervision, therefore drift could be identified by the supervisee, supervisor, meta-supervisor or line manager. This could be recognising behaviours within oneself as a supervisee that indicate drift (e.g. only bringing questions rather than recordings to supervision), recognising the receipt or provision of restricted supervision methods through the formal or informal use of the SAGE (e.g. verbal case discussion every session). Once drift has been identified either through a discussion between supervisor and supervisee, through self-supervision or within supervision of supervision (SoS), it is necessary for there to be a means of making sense of why this has occurred, a benchmark for what supervision has strayed from (e.g. Tandem model, Gordon’s ten steps, BABCP guidance) and how to get supervision back on track. Whilst macro-skills such as setting out a supervision contract at the start of the relationship is one way of determining if one or both parties have neglected their agree duties, it is the ‘micro-skills’ of the supervisor (James et al., Reference James, Milne and Morse2008) that help to successfully manage this. Three hypothetical examples are presented below to illustrate where drift could be identified and how solutions might be explored and initiated.

Case example 1

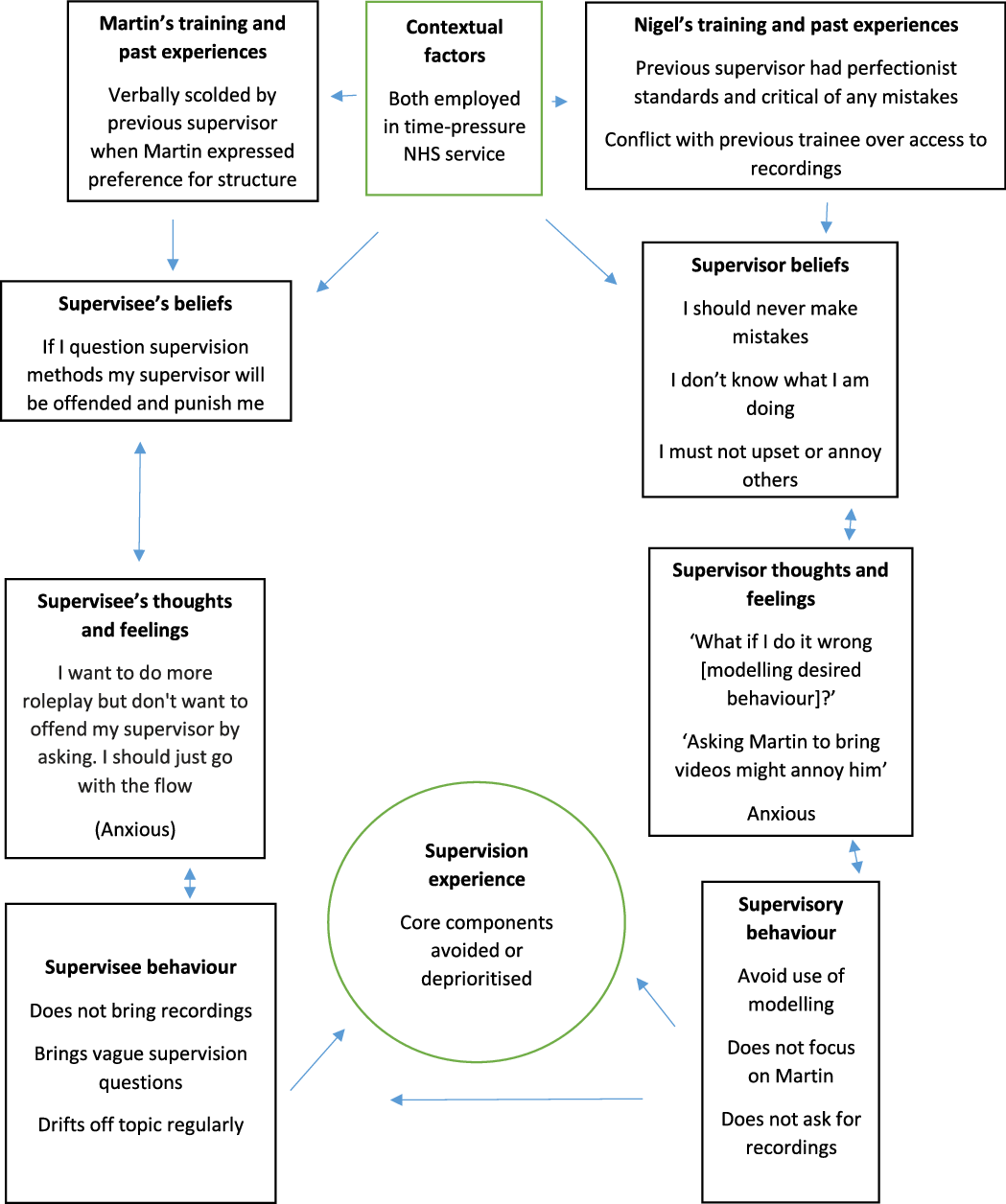

Martin (supervisee) and Nigel (supervisor) both worked in an NHS service. Martin noticed that his supervision with Nigel felt rushed and that he tended to only receive advice from him when he was stuck with clinical cases. Martin had read the Gordon (Reference Gordon2012) paper and wanted to have more chance to engage in role plays during supervision but had felt reluctant to bring this up with Nigel for fear of offending him or being punished. Their sessions would often drift off topic to become more restorative (e.g. mutual rants about service targets) with little focus on the normative and formative tasks. Furthermore, Nigel did not ask Martin to bring recordings to supervision, so he only had the word of his supervisee that he was practising competently. It could therefore be argued that in this supervision dyad there was a lack of agreement on the tasks of supervision (Ladany et al., Reference Ladany, Mori and Mehr2013). In a SoS session, Nigel’s meta-supervisor, Lisa, asked him to bring a recording of a supervision session to jointly review his practice. When they watched the footage, Lisa applied the SAGE rating scale (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011) and noticed several missed opportunities where Nigel could have taken a more experiential approach with Martin. Using Socratic dialogue Lisa asked Nigel about what he noticed about the session content and structure. Watching the session back allowed Nigel to ‘reflect-on-action’ (Schön, Reference Schön1987) and he immediately realised that the session felt more like a ‘chat’, lacked clear supervision questions on the part of the supervisee and there was an absence of ‘active’ methods such video review, modelling or role play. Using Kolb’s (Reference Kolb1984) learning cycle, Lisa checked if Nigel had the knowledge and skills to make changes to his supervisory practice based on what they had identified. Nigel possessed the declarative knowledge about how to do modelling and role play but lacked confidence in the procedural application of these methods. Lisa modelled these methods and then asked Nigel to swap roles and to model introducing role play. Following this, Nigel developed a plan for addressing the loose structure to his supervision sessions including a review of Martin’s bespoke needs. Furthermore, Nigel aimed to vary how he responded to supervisees by modelling rather than simply telling them what to do.

Case example 2

Maureen and Pat were both working in private practice and had been engaged exclusively in a peer supervision arrangement for the last 18 months. Ian had asked to join them and immediately noticed significant differences from the supervision he had experienced prior to this. Whilst Ian welcomed a greater sense of autonomy compared with what he felt was micro-management previously, he was concerned that there was no one ‘in charge’ to oversee structure to the peer supervision group. There was no agenda set at the start of the sessions and from what Ian had observed, it appeared as if Maureen and Pat used the time to predominantly ‘offload’ about their clients. No constructive criticism was provided by either party, which led to Ian feeling awkward about sharing feedback with Maureen or Pat. Having recently attended some supervisor training, Ian recognised that Maureen and Pat appeared to be caught up in the game ‘Evaluations are not for friends’ (Delano and Shah, Reference Delano and Shah2006; Kadushin, Reference Kadushin1968). Reflecting on how this might lead to ineffective supervision at times, Ian suggested that one person take the lead each session, rotating between the three of them. This would ensure that a clear agenda was set and there would be a reminder of times being allocated to each supervisee to discuss items. Ian also suggested that they review the SAGE document at their next meeting to see how this could be used to inform the quality of their supervision experience. Maureen and Pat initially held some reservations but agreed to try this new format going forward.

Case example 3

Alicia would often come to supervision unprepared and proceed to give her supervisor Waseem lots of details about the client’s history, often meaning that they were unable to finish the session with a clear understanding of what she was going to do differently based on supervision. Furthermore, Waseem was often unsure what Alicia’s declarative knowledge or procedural understanding were of various problems due to having insufficient time to review this. When asked to generate some specific supervision questions by Waseem, Alicia would become defensive, stating that she did not have sufficient time to prepare questions in advance. Alicia would also accuse Waseem of being too ‘business like’ when he tried to set a clear agenda. Waseem was concerned that if he continued to push Alicia to be more structured, this would strain their relationship and cause a rupture.

Formulating the problem

Relating these three vignettes to Pugh and Margetts’ (Reference Pugh and Margetts2020) definition of drift, various aspects of supervision had been unintentionally ‘omitted, avoided or deprioritised’ (p. 5). Martin’s unspoken needs, Nigel’s lack of confidence, Alicia’s inefficiency and Maureen and Pat’s dislike of too much structure and discomfort with giving each other critical feedback had inadvertently led to supervision that was potentially lacking in at least one aspect of the primary functions (normative, formative, restorative). Without a CBT specific means of raising this, for Martin, Ian and Waseem as supervisors or for Lisa as a meta-supervisor, highlighting these concerns could potentially lead to defensiveness from the other parties or at worst a rupture (Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006).

How then can a supervisor, supervisee or meta-supervisor bring these issues to light in a way that fosters curiosity and collaboration rather than defensiveness? Given that ‘in many respects, the exchanges occurring within supervision are more complex than those occurring within therapy’ (James et al., Reference James, Milne and Morse2008; p. 29), consideration is needed around how and when to raise concerns within the supervision dyad. A tool already familiar to CBT practitioners, formulation is one such means of developing a shared understanding of potentially problematic behaviour such as drift. A cognitive conceptualisation of within-supervision behaviours should assist the supervisor and supervisee or meta-supervisor and supervisee evaluee (Newman, Reference Newman2013) in ‘de-centring’ from their typical dynamic (i.e. to take a step back from habitual behaviours such as the supervisee venting about their employer and the supervisor passively allowing this).

It should also provide a shared language for the dyad to discuss problematic behaviours in a curious and non-confrontational way. To do so, it should draw upon existing CBT formulations and terminology so that it is accessible for the supervisor to draw out with the supervisee during a supervision session. The information that is captured in the formulation might start with a simple five areas model (see Wright et al., Reference Wright, Williams and Garland2002) and progress to an interpersonal or longitudinal version including relevant background information should the need arise. Both versions would include the cognitions, emotions, physiology and behaviours of one or both parties, together with an appreciation of their respective learning histories.

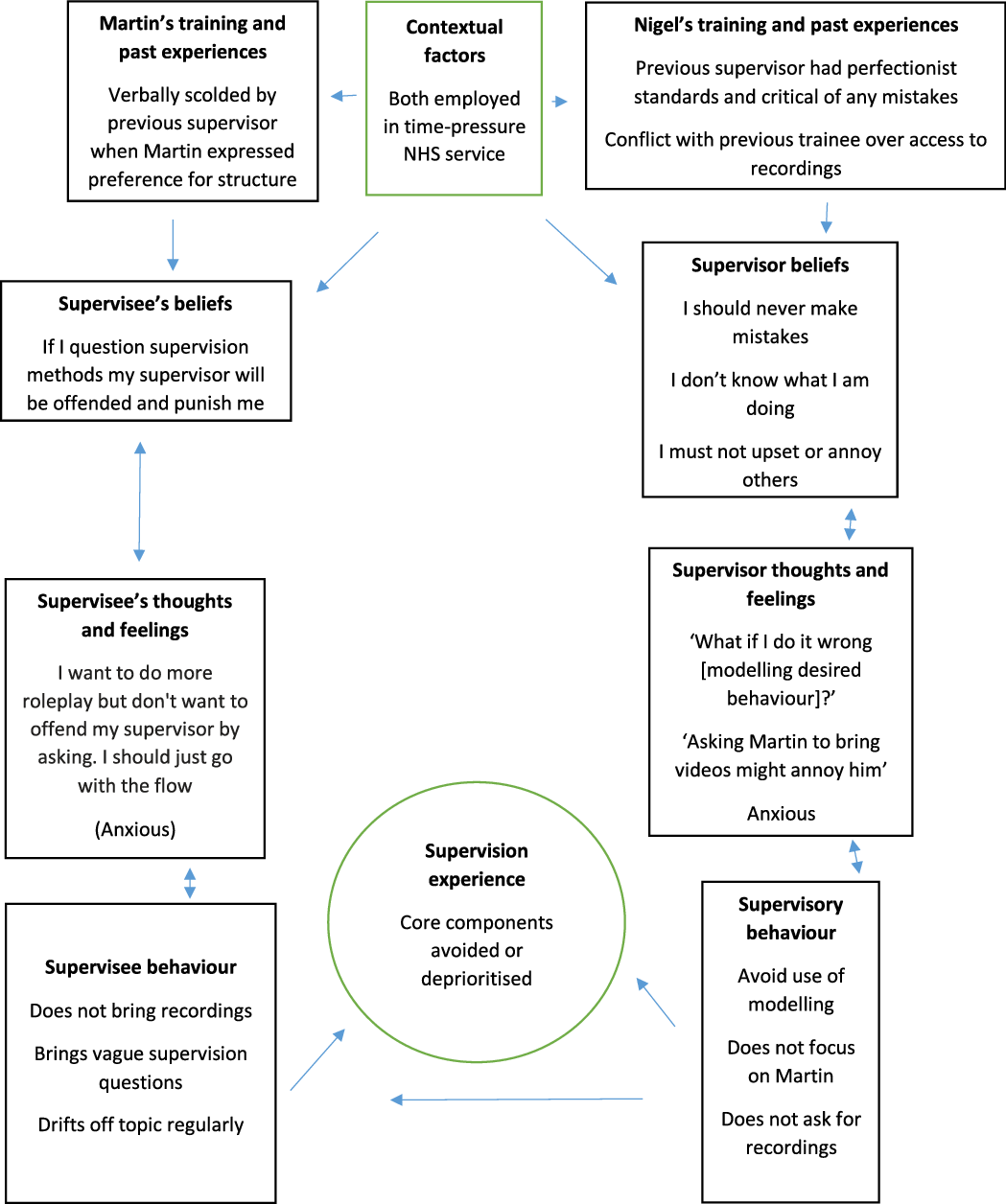

The formulation presented below in Fig. 1 is one of way of conceptualising supervisory drift and is a modified version of Moorey’s (Reference Moorey2013) Interpersonal Cycle worksheet to illustrate how supervisory drift may arise. Past experiences and contextual factors are added to help both parties make sense of the reasons why they have developed specific beliefs and behaviours within supervision. Using Nigel and Martin as an example, it demonstrates how Lisa drew out the problem behaviour during a SoS session. Longitudinal information such as ‘personal self’ information about the supervisor or supervisee might not be known by the person drawing out the model and, in this case, Lisa worked with what she knew of Nigel’s therapist and supervisor ‘selves’ and his knowledge of Martin’s history. The formulation helped Nigel to understand that he needed to know more about what Martin was experiencing within supervision (his cognitions and emotions about supervision) and how his previous experiences of supervision might be influencing how he behaves with Nigel.

Figure 1. Supervisory drift formulation (based on Moorey, Reference Moorey2013) used in Supervision of Supervision (SoS) to help supervisor-evaluee Nigel make sense of his restrictive use of supervision methods.

Section 4: Potential solutions

Staying on track

Avoiding drift at the outset is preferable; however, all supervisors and supervisees are only human and therefore susceptible to making mistakes. As Waller (Reference Waller2009) aptly puts it, ‘errors are unavoidable and to be expected. The key is whether we spot them and respond to them appropriately’ (p. 121). Having a clear idea of where one needs to be is a useful starting point and therefore becoming familiar with best practice guidance and becoming familiar with SAGE and regularly using it within supervision, SoS or self-supervision is essential (see Armstrong and Freeston, Reference Armstrong, Freeston and Tarrier2006; Bennett-Levy and Thwaites, Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Gilbert and Leahy2007; Corrie and Lane, Reference Corrie and Lane2015; Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Ballantyne and Scallion2015; Gordon Reference Gordon2012; James et al., Reference James, Milne, Marie-Blackburn and Armstrong2006; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011; Pretorius, Reference Pretorius2006) is recommended. From the author’s prior research and experience as a trainer of supervisors, not all who practise do so with knowledge of SAGE or these best practice principles (Roscoe et al., Reference Roscoe, Taylor, Wilbraham and Harrington2019). The availability and content of supervisor training and the importance that employers place on ensuring their supervisors have access to it could be crucial to this (Culloty et al., Reference Culloty, Milne and Sheikh2010; Younge and Campbell, Reference Younge and Campbell2013).

Furthermore, as previously stated, supervision is not yet at a stage where a specific protocol can be mandated in the way that evidence-based protocols for CBT treatment are. In the absence of this, effective CBT supervision is guided by the combination of an emerging evidence base (Milne, Reference Milne2017), expert recommendations (e.g. Pretorius, Reference Pretorius2006) and accrediting body standards (e.g. BABCP). By having these principles in mind, supervision dyads can jointly reflect on whether supervision sessions have included these facets on a regular basis.

Formulation might capture different types of games that supervisor or supervisee have been playing. For supervisors, SoS would appear to be the most obvious setting to review supervision structure and content. Using the Milne and Dunkerley tandem analogy (Reference Milne and Dunkerley2010), reviewing the supervisory dynamic could be seen as both cyclists ‘pulling over’ to rest, review where they have been so far and where they are heading. Potential or actual indicators of drift can then be discussed and problem solved.

Anticipating problems before they arise

To normalise interpersonal and intrapersonal reflection within supervision it can be helpful to gather a basic overview of the supervisee’s personal self and therapist self history, in order to construct a ‘psychological contract’ (Clohessy, Reference Clohessy2019). Using either a written questionnaire or a pre-supervision interview, the supervisor can ascertain important aspects of how to manage the supervisory relationship by asking the supervisee questions such as ‘what background information (either personal or therapist self ) do you think it is important for me to know about you?’ or ‘how might we address differences of opinion?’. Supervisor and supervisee can then use the responses to these questions to anticipate instances in supervision where these might be relevant. This might involve mapping out some of the boxes in Fig. 1 and building a written formulation up over several supervision sessions. For example, if Nigel had asked Martin to complete an induction questionnaire, then he could have established his learning preferences and past experiences of supervision earlier in their supervisory relationship. Similarly, if Waseem had completed this with Alicia, they would have recognised from the beginning that they have very different styles and could have planned for how they might work together to reach a compromise.

Recommendations

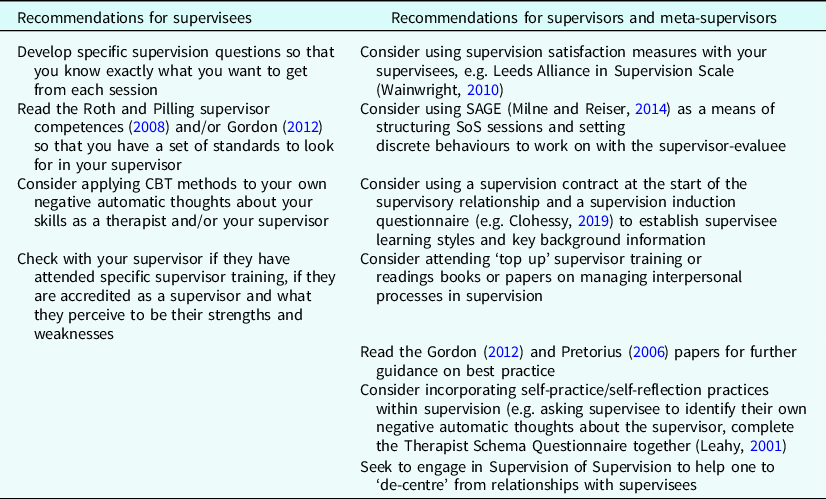

Table 4 provides a range of suggestions for ways in which supervisors and meta-supervisors can introduce a range of safeguards to minimise the risk of supervisory drift. Similarly, supervisees would benefit from knowing how to be an effective supervisee (Bliss et al., Reference Bliss, Convery, Kellet and Spark2018) and a summary of recommendations for both members of the dyad are provided below, which might reduce the likelihood of drift occurring if these are in place.

Table 4. Ways to reduce likelihood of drift

Adapting supervision to the needs of the supervisee

It could be argued that a competent supervisor will not only move between normative, formative and restorative tasks based on the emotional and learning needs of the supervisee, but also consider the learning style preferences and context in which the supervision takes place (Grey et al., Reference Grey, Deale, Byrne, Liness, Whittingham and Grey2014; James et al., Reference James, Milne, Marie-Blackburn and Armstrong2006). For example, qualified therapists may have fewer formative needs than trainees having grasped the basics of formulation and disorder specific treatment and therefore supervision may require a greater focus on the normative (e.g. addressing ethical challenges), or restorative aspects (where the supervisee needs to emotionally process a challenging therapy session with a hostile client). Conversely, inexperienced therapists may require a greater formative focus (e.g. teaching the supervisee an intervention through modelling or role play). Furthermore, the Declarative-Procedural-Reflective (DPR) model of therapist skill development and refinement by Bennett-Levy (Reference Bennett-Levy2006) can usefully inform the educative functions of supervision. Whilst a detailed explanation of this model is beyond the scope of this paper, in summary, supervisors might gauge the declarative knowledge of their supervisees (e.g. by asking what they know about the diagnostic criteria for a given disorder, what the model and interventions are and in what order) and also the procedural knowledge (e.g. how often the supervisee has put into practice their declarative knowledge by applying these interventions with clients). In doing so, supervisors can try to tailor supervision to the stage of development of their supervisee (Pretorius, Reference Pretorius2006).

Using active supervision methods to better understand drift

Drawing on the concept of ‘self-multiplicity’ (Pugh, Reference Pugh2019a), supervisors can bring to life the different selves of the supervisee (the personal self, therapist self and supervisee self) and their relative contributions to supervision (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Pugh, Reference Pugh2019a; Pugh Reference Pugh2019b; Pugh and Margetts, Reference Pugh and Margetts2020). Utilising the examples and format of in-person or online cognitive behavioural chair work (Pugh, Reference Pugh2019a; Pugh and Bell, Reference Pugh and Bell2020), the supervisor might ask the supervisee to embody the three ‘selves’ at different points during a supervision session using ‘intrapersonal role-plays’ (Pugh, Reference Pugh2019b; p. 5) with the aim of developing meta-cognitive awareness of the motivations that belong to each ‘self’. For example, the supervisor might suggest interviewing the part of the supervisee that is resistant to certain aspects of supervision (e.g. showing recordings of therapy sessions). The supervisee intake questionnaire might be a useful document to refer to when setting up this exercise. See Fig. 2 for a fictional example of this method in action.

Figure 2. Using chair work to identify factors involved in drift.

In the above vignette, the supervisor clearly links the rationale for the exercise to a potential difficulty that was flagged up at the start of the supervision contract (handling any form of criticism). The supervisor then proceeds to interview the supervisee’s ‘personal self’ who as it transpires is very sensitive to any perceived criticism and tends to personalise and ruminate on negative feedback. Following this, they also interviewed the supervisee’s therapist self (by switching chairs to embody the other part of them) who was able to put forward several useful reasons for making video feedback a more integral part of supervision. The supervisor concluded the chair work by asking the supervisee to open a dialogue between personal and therapist selves by getting the supervisee to move back and forth between different chairs. Adding a playfulness to supervision potentially reduces the likelihood of conflict between supervisor and supervisor, instead allowing them both to team up to better understand normal processes that can get in the way. The supervisor could help to normalise this by modelling what their own resistant self thinks about bringing videos to supervision. Finally, completing the Therapist Schema Questionnaire (Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006; Leahy, Reference Leahy2001) during supervision could be another way to normalise problematic beliefs and behaviours that both supervisor and supervisee could be vulnerable to. Recent research suggests that CBT trainees may be receptive to learning about interpersonal and intrapersonal processes and bringing related to questions to supervision (Roscoe, Reference Roscoe2021a), therefore incorporating this within standard CBT training could assist in self-reflective skills.

Supervision of Supervision

Similarly in SoS, the meta-supervisor facilitates a process of reflection to allow the supervisor-evaluee to consider how their various selves contribute to their supervisory practice. As demonstrated in the earlier vignette with Nigel, supervisors may struggle to be objective about their supervisory competence or blind spots. For this reason, engaging in SoS is essential for developing and improving the capacity to ‘de-centre’ from supervision (Barton, Reference Barton2015). A fresh set of eyes allows an impartial observation of the dynamics that are in operation between supervisor and supervisee. The meta-supervisor can also use recognised frameworks on which to offer feedback on the supervisor-evaluee skillset (see Gordon, Reference Gordon2012; Milne and Reiser, Reference Milne and Reiser2014). There has been little written on SoS (as an exemplar, see Newman, Reference Newman2013) to guide those who might provide it or look to access it. From the author’s experience, manuals such as SAGE (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011; Milne and Reiser, Reference Milne and Reiser2014) provide a benchmark for the formal marking of supervision sessions against a recognised set of criteria. A significant benefit of SAGE is that due to it using the Dreyfus scale, those already familiar with the CTS-R (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) are likely to be able to adapt to it reasonably quickly. By reviewing video or audio footage with a meta-supervisor or as a self-supervision exercise (Bennett-Levy and Thwaites, Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Gilbert and Leahy2007), SAGE scores 18 supervisor behaviours and five supervisee behaviours, and this might assist the supervisor in recognising patterns in how they behave during supervision sessions (e.g. a tendency to collude with avoidant supervisees).

Alliance measures

A strong supervisory relationship has been shown to predict our current understanding of what constitutes successful or highly effective supervision (Moorey and Byrne, Reference Moorey, Byrne, Moorey and Lavender2019). Frequently measuring how strong the alliance is would seem sensible; however, it is difficult to establish from the existing literature how widely used alliance measures are within routine CBT supervision. Capturing the supervisee’s overall satisfaction with supervision using a validated measure may facilitate the disclosure of helpful negative feedback which might otherwise not be volunteered (Ladany et al., Reference Ladany, Mori and Mehr2013; Yourman, Reference Yourman2003). A measure triggers a discussion of the feedback and may provide a useful opportunity for a mutual exchange of feedback about each party’s experience of supervision. If Nigel had used an alliance measure with Martin, then the dissatisfaction with supervision structure could have been detected earlier. Whilst there is no widely endorsed CBT-specific alliance measure for supervision, the Leeds Alliance in Supervision Scale (Wainwright, Reference Wainwright2010) is an example of a measure that is brief enough to be administered at the end of a supervision session and can be reviewed as part of the next session agenda. Specific scales designed to elicit therapist cognitions which relate to drift have been proposed (Rameswari et al., Reference Rameswari, Hayes and Perera-Delcourt2021) and referring supervisees to literature such as this and other related concepts (e.g. Leahy’s Therapist Schemas) may help to normalise discussion of therapy-interfering beliefs and behaviours within supervision (Leahy, Reference Leahy2001; Moorey and Byrne, Reference Moorey, Byrne, Moorey and Lavender2019).

Discussion

The aim of this paper was twofold. Firstly, it aimed to draw together the minimal existing knowledge about the identification and management of supervisory drift within CBT. This involved a review of the extant literature on the functions of supervision, the state of play in supervision research and extracting potentially relevant concepts from neighbouring literature (e.g. therapist schemas, skill development and drift). As a result, this is the first CBT-specific paper to propose a set of pre-disposing factors that seek to explain the origins and maintenance of supervisory drift.

Secondly, it aimed to be a practical resource for supervisors and supervisees to relate to their supervisory practice by reflecting on their use of supervision and the reasons for this. Examples of where drift might be occurring have been provided, together with a summary of best practice recommendations that might reduce the possibility of drift occurring. It is hypothesised that drift is often an unintentional process, characterised by a lack of emphasis on the formative and normative aspects of supervision arising from a combination of supervision context, supervisor and supervisee beliefs, emotions and safety-seeking behaviours.

Future directions

The hypothesised causes of supervisory drift presented in this paper lack empirical data at present and consist of existing ideas about therapist skill development (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006), supervision research and interpersonal processes (Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006; Kadushin, Reference Kadushin1968; Moorey and Byrne, Reference Moorey, Byrne, Moorey and Lavender2019; Thwaites and Bennett-Levy, Reference Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2007; Roscoe, Reference Roscoe2021b; Watkins, Reference Watkins2020). Further research is required to test both the components of the model (e.g. the presence of specific maladaptive supervisor and supervisee cognitions) and the face validity and acceptability of this amongst practising supervisors.

The refinement of the model will require input from supervisors and supervisees through presenting it in supervisor training workshops, focus groups or questionnaire-based feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of the model. A lack of familiarity with therapist schemas by supervisors could be a barrier to the immediate accessibility of the model and therefore consideration is needed in terms of how much training will be needed. It would also be necessary to establish the most appropriate platform for its use (e.g. within a standard supervision review or within SoS).

Many questions remain unanswered therefore, and to better understand supervisory drift (SD) more generally it is necessary to answer several questions that we still know little about, including but not limited to, the following:

-

When is SD most likely to occur in a supervisee’s career? (e.g. in training or when one has been qualified for over 10 years)

-

Is SD more likely in novice or highly experienced supervisors?

-

Are certain supervision formats more susceptible to SD than others? (e.g. webchat/peer supervision)

-

Is there a relationship between engaging in supervisor training and being less likely to drift as a supervisor?

-

Is there a measurable relationship between certain therapist schemas (e.g. need for approval) and SD?

-

Does SD negatively impact the quality of therapy delivered in clinical practice by the supervisee?

-

Does supervision of supervision and the use of related tools (e.g. SAGE) reduce the frequency of drift?

Suspicions of drift should always be raised gently and without jumping to conclusions. Returning to Pugh and Margetts’ (Reference Pugh and Margetts2020) definition of drift where core components are ‘omitted, avoided or deprioritised’, what might appear to be drift, could be highly responsive supervision that is tailored to the needs of the individual at a particular moment in time rather a rejection of the manuals. The SAGE, for example, allows for the marker to omit certain criteria if they are not deemed applicable to the needs of the supervisee in any given session (Milne, Reference Milne2017).

Moreover, as Kennerley et al. (Reference Kennerley, Kirk and Westbrook2017) caution, ‘embarrassingly for an approach that values empiricism as CBT does, there is not yet a significant body of evidence about whether CBT supervision actually makes a difference, either to the supervisee’s skills or to the outcomes for clients’ (p. 428). In other words, for supervisory drift to be considered a serious problem that requires addressing, there needs to be tangible ‘real world’ consequences to poor supervision. Whilst it is relatively easy to see the consequences of therapist drift (e.g. therapist delivers incorrect or ineffective treatment to a client who then fails to recover from their episode of depression or anxiety disorder), the measurable effects of supervisory drift are arguably more difficult to establish.

Furthermore, drift does not necessarily equate to harmful supervision for the supervisee (for a description of unethical and harmful experiences in supervision, see Reiser and Milne, Reference Reiser and Milne2016). In the supervision vignettes that were used earlier it could be speculated that the absence of a set of basic over-arching principles (e.g. Pretorius, Reference Pretorius2006) made it more likely for drift to arise. In light of this and to work effectively with the array of challenges that can emerge in the supervisory relationship, a range of supervisor ‘micro-skills’ are required to identify, formulate and work through drift when it arises. SAGE offers a validated tool to supervisors to self-reflect on their own work or for meta-supervisors to work within an evidence-based framework when giving feedback on supervisor skill. Finally, humility and curiosity rather than an authoritarian and judgemental approach are key interpersonal pre-requisites for supervisors and meta-supervisors when raising this topic.

Key practice points

-

(1) CBT supervisors and meta-supervisors can draw upon existing CBT principles including self-practice and self-reflection (e.g. Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001; Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006) to help supervisees make sense of supervisory drift and why it occurs.

-

(2) A bespoke formulation of supervisory drift enables the supervisor and supervisee to have a shared language for examining drift with curiosity rather than criticism and defensiveness.

-

(3) There is an EBCS framework and range of existing best practice resources that meta-supervisors can draw upon to assist less experienced supervisors in evaluating and improving their skills and self-reflection (e.g. Gordon, Reference Gordon2012; Milne, Reference Milne2017; Milne and Reiser, Reference Milne and Reiser2014) and which supervisors can introduce to their supervisees to promote more effective use of supervision time (e.g. Grey et al., Reference Grey, Deale, Byrne, Liness, Whittingham and Grey2014; Kennerley et al., Reference Kennerley, Kirk and Westbrook2017; Padesky, Reference Padesky and Salkoskis1996).

-

(4) Further research is needed to test the acceptability of the proposed model in routine practice by supervisors, meta-supervisors and supervisees.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Julie Taylor, Rhiannon Blackley and Mathew Pugh for general support with preparing this paper, and the supervisors who have attended supervision training and contributed to discussions which led to the development and refinement of several ideas within the paper.

Financial support

The author received no funding for this piece of research.

Conflict of interests

The author has no conflict of interests with respect to this paper.

Ethics statements

The author has abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Ethical approval was granted by University of Cumbria (reference number 17/59).

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article, as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contribution

As sole author, Jason Roscoe takes full responsibility for all aspects of this paper.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.