Introduction

The evidence-based psychological therapy for treating obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) that includes exposure and response prevention (ERP) (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Sookman, Neziroglu, Wilhelm, Stein, Kyrios, Matthews and Veale2015). CBT with ERP is a theoretically and empirically grounded therapy in which patients with OCD gradually expose themselves to situations without safety seeking behaviours. They learn to tolerate the distress and test out their expectations. The evidence is derived from controlled trials where the CBT is delivered by trained therapists, who receive supervision.

This evidence is then generalised to developing competencies for the delivery of CBT for OCD and training of therapists (Clark, Reference Clark2018; Sookman et al., Reference Sookman, Phillips, Anholt, Bhar, Bream, Challacombe, Coughtrey, Craske, Foa, Gagné, Huppert, Jacobi, Lovell, McLean, Neziroglu, Pedley, Perrin, Pinto, Pollard and Veale2021). Cognitive behaviour therapists come from a variety of professional backgrounds, but especially psychology. Some will have postgraduate training in cognitive behaviour therapy, and some will have specialist experience in obsessive compulsive disorder. They may be employed in the NHS in the UK to deliver therapy which is free at the point of access. They may also be employed in a private clinic or in other countries may be re-imbursed by a state insurance. Alternatively, qualified therapists work in the private sector and may be directly paid by the client or by a private medical insurance. Qualified psychologists and cognitive behaviour therapists across the world are nearly always regulated by a professional standards authority. The standards will vary internationally but usually involves (a) attending continuous professional development, (b) adhering to a code of conduct or ethics, and (c) space for reflection and receiving supervision. There will also be a complaints system related to errors in clinical care or unprofessional conduct. This may be investigated, and therapists may have to go before a disciplinary board and ultimately lose their licence to practise. There is increased recognition of the value of involving clients and the public in working with regulators to tackle poor practice and strengthen confidence in health and care services.

People with OCD may find it difficult to access good quality cognitive behaviour therapy. Various solutions such as web-based programs and apps are being developed (Pozza et al., Reference Pozza, Andersson and Dèttore2016; Salazar de Pablo et al., Reference Salazar de Pablo, Pascual-Sánchez, Panchal, Clark and Krebs2023). Therapy might be enhanced by supporting a family member as a coach or co-therapist (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Baucom, Wheaton, Boeding, Fabricant, Paprocki and Fischer2013; Renshaw et al., Reference Renshaw, Steketee and Chambless2005). The term ‘coach’ for people with mental health difficulties grew out of the recovery movement, with a coach adhering to good practice defined as someone who works under the supervision of a mental health professional, upholds professional standards through continuous professional development, and aims to help individuals build resilience, strengths, and a meaningful life beyond their mental health condition (Bora et al., Reference Bora, Leaning, Moores and Roberts2010). Mancebo et al. (Reference Mancebo, Yip, Boisseau, Rasmussen and Zlotnick2021) have described the use of training behavioural therapy teams to deliver ERP. Many in-patient and residential units may use trainees and students as assistants to help deliver intensive CBT (Veale et al., Reference Veale, Naismith, Miles, Gledhill, Stewart and Hodsoll2016). However, such individuals are closely supervised by qualified mental health professionals, who take responsibility for the assistant or coach.

There are many sources where people seek mental health treatment, including friends, family, and traditional and faith-based healers. For example in Ujung Pandang, Indonesia, 54% of patients presenting at a psychiatric service had their first point of call with a native or religious healer and 18% with a primary care physician, whereas in Manchester, Setubal, Granada, Benesov-Kromeriz and Havana, 66–81% initially consulted a general practitioner (Gater et al., Reference Gater, de Almeida e Sousa, Barrientos, Caraveo, Chandrashekar, Dhadphale, Goldberg, al Kathiri, Mubbashar and Silhan1991). A broad spectrum of healthcare and community resources exists for people with mental health difficulties. Sources may vary across contexts, shaped by accessibility, cultural values, and local mental health resources.

For people with OCD, where access to high-quality CBT may be limited, in the UK we noticed an increase in the number of clients consulting unregulated and unqualified coaches. Such coaches often had a personal experience of OCD and may be costly to consult. Many have a large following on social media. Thus, it is important to understand what might constitute this coaching so that charities and people with OCD are able to make informed decisions. It may overlap with the harm identified in psychotherapy. Curran et al. (Reference Curran, Parry, Hardy, Darling, Mason and Chambers2019) reviewed studies on the harmful effects of psychotherapy including CBT and identified various factors in the harm of clients. These involved a range of unhelpful therapist behaviours (e.g. over-control, lack of knowledge) associated with the clients feeling disempowered, silenced, or devalued. These were coupled with issues of power and blame by the therapist.

We are not aware of any reports on the harm or benefit of coaches in OCD. The aim of this study was therefore to explore the experiences of people who have received help for OCD from unqualified and unregulated coaches who claim to be experts by experience, and the effect this had on them. It was hoped that defining the characteristics could help to draw up red flags and possible aspects of the coaching that participants benefited from. We use the term ‘coach’ in this paper to refer to the unregulated and unqualified individual that is the subject of this study, while the term ‘therapist’ is used to describe a qualified, regulated professional trained in cognitive behavioural therapy.

Method

Due to the lack of research in this area, we explored the topic and the personal experiences of people with OCD who have undertaken sessions with an unqualified or unregulated individual or group (referred to as a ‘coach’), using interviews to allow qualitative exploration of this topic. Thematic analysis was used to identify common themes in participant experiences (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). By exploring the perspectives and subjective interpretations of participants, we aimed to provide an understanding of the experience that participants had while working with unqualified coaches. Interviews were conducted online in private office spaces via Microsoft Teams at a time and place of the participants’ choosing.

This study employed a purposive sampling strategy to recruit participants through advertisement on websites and social media of OCD charities. The Participant Information Sheet started the purpose of the project was to investigate ‘the experiences and effects of receiving treatment for OCD from unqualified and unlicensed individuals who claim to be experts by experience or coaches’. This was used to reach the specific target population required and increase the likelihood of recruiting individuals who met the inclusion criteria for the study.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were to be aged over 18 years and having received treatment for OCD by individuals who are unqualified and unlicensed to be providing such treatment. The coaches claimed to be experts by experience, with no reference to any formal training or licence. The individuals were identified on their websites and checked that they did not appear on any professional registers and were not accredited in CBT. People with OCD were self-identified and screened at interview as having been diagnosed by a health professional. There were no other exclusion criteria.

Data collection

Interviews were carried out by two female mental health nursing trainees (J.-E.L. and M.C.) who received training in thematic analysis. Neither researcher had prior relations with any of the participants interviewed. D.V. has a record of research and clinical practice in OCD and is a trustee of a charity for people with OCD and may be biased against the use of unqualified coaches. U.F. is an academic researcher. Participants were aware of the reasons for doing the research and were keen to share their experiences for the benefit of others in the OCD community.

Interviews were carried out over a 4-week period beginning in March 2023. Semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions were used to gain an understanding of the participants’ experience. The interview guide (see Supplementary material) was first outlined by the first author with the purpose to understand what constitutes the treatment used by the coaches, how they are advertised, and to explore their effects by using core and associated questions relating to the central question. This was then discussed with the two nursing trainees before a pilot interview was carried out, from which minor adjustments were made prior to participant interviews. Interviews were video and/or audio recorded with written and verbal consent obtained. Interviews lasted between 42 and 102 minutes (average duration = 70 minutes). The audio was transcribed verbatim, firstly by the trainee nurses who carried out the interview before being checked against the audio by the other. Respondent validation was employed, and each participant was given the option for completed transcripts to be returned for correction or comment to ensure further rigour in both accuracy of data reported and participant involvement. Participants were also given the opportunity to submit written material at their discretion, such as correspondence, digital messages, or proof of expenditures to provide further evidence to support the participants’ statements. These were not used in the thematic analysis. Letters were assigned to each participant during transcription and identifying information removed to ensure anonymisation and confidentiality.

Participants

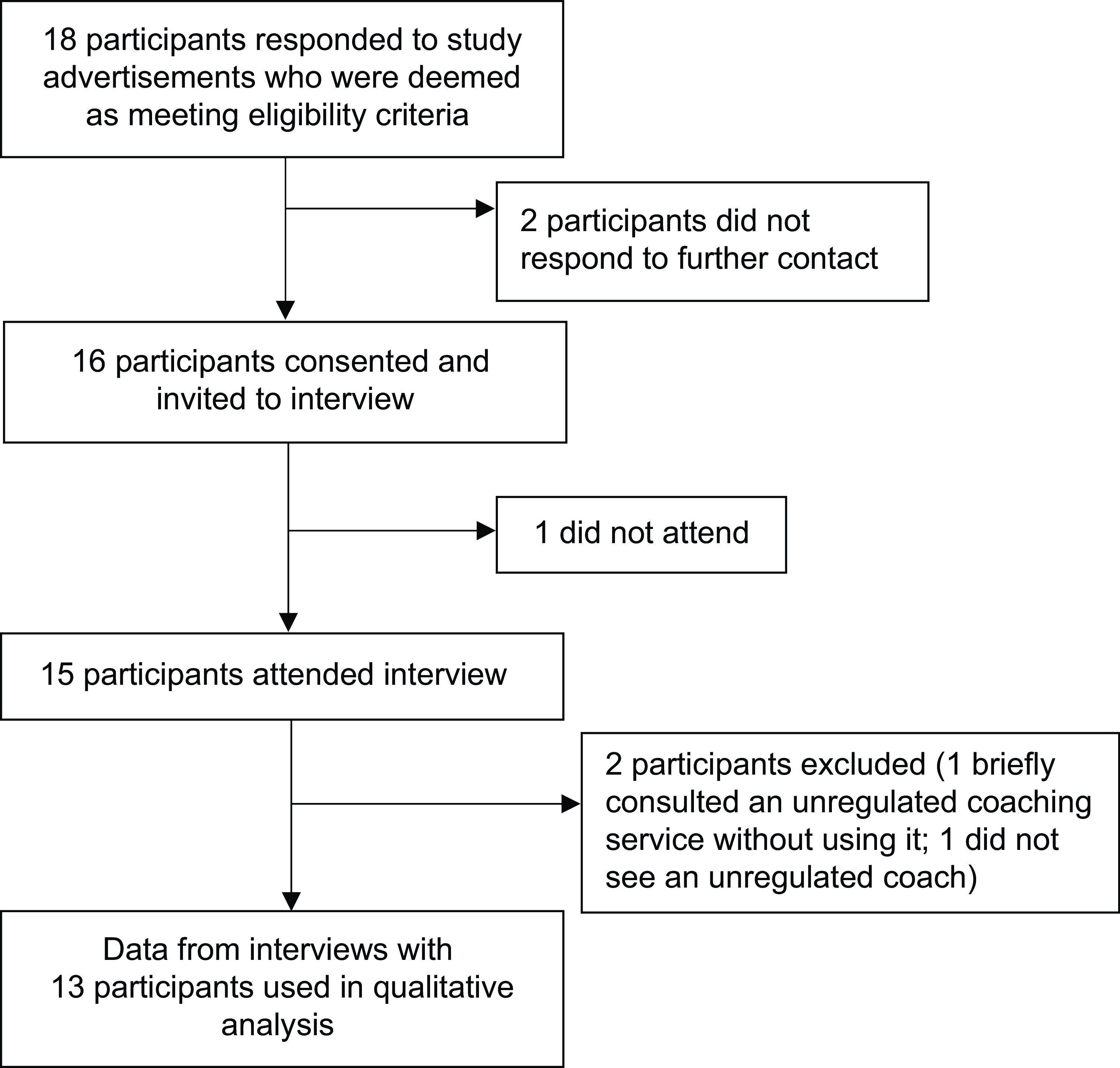

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants throughout the study from recruitment to data analysis. Data saturation had occurred after interviewing 13 eligible participants. None of the participants was receiving treatment.

Figure 1. Participant flow chart.

Participants were aged between 23 and 67 years. Eight were female, and five were male. Ten were in professional or semi-professional employment, two were students and one was unemployed. Two ethnicities were reported (10 white, 3 Asian).

Five different coaches were identified by name and by their website. Nine participants (A, B, D, E, G, H, I, K, N) identified the same coach. Two participants (L and O) identified one coach, and two participants (J and C) identified two different coaches. Prior to the interview participants were provided with an information sheet about the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interview. Participants were debriefed immediately after the interview had ended and were encouraged to contact the first author should they experience any distress post-interview.

Analysis

Interviews were double-transcribed before being analysed using the reflexive thematic analysis framework (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2023). The two trainee nurses open coded each transcript independently line-by-line using paper, Microsoft Word and Excel. Initial codes were generated and documented before being grouped into categories. From the categories initial themes were generated independently by the trainee nurses and over-arching themes were developed from shared patterned meaning collected from the dataset. Unified common codes were then compared and contrasted to identify a series of candidate themes. Subordinate and superordinate themes were developed and reviewed from the candidate themes. Quotations were independently extracted from the full dataset, reviewed by the team, and assigned to corresponding themes. Extracts were compared and evaluated for their suitability and relevance to the central organising concept of each theme. All steps of analysis were carried out by the trainee nurses with formative feedback by the first author throughout, before the fifth step where the first author and trainee nurse were involved in the formulation, synthesis and demarcation of superordinate and subordinate themes until a final agreement was reached.

Results

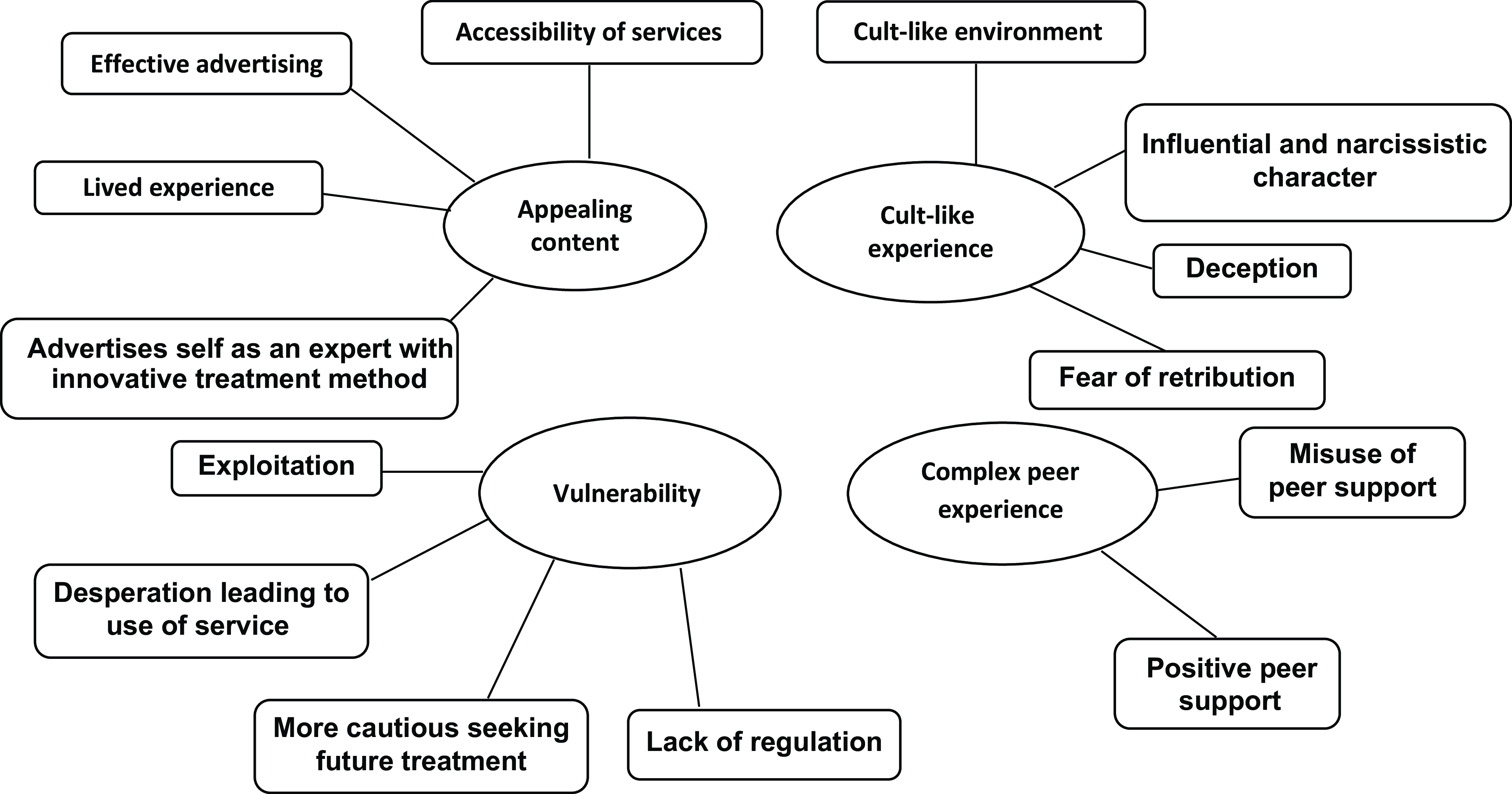

Each participant had one coach each. Of the five coaches (3 male, 2 female) identified in total by participants, four coaches were rated as negative and one participant rated their coach positively (this coach did not treat any other participant). There were no other positive reports made from other participants, and it could not therefore become a theme. Four over-arching themes were identified in the four other coaches who were rated negatively: (1) Appealing content, (2) Vulnerability, (3) Cult-like experience, and (4) Complex peer relationships. A theme diagram can be found in Fig. 2. Each of these themes and their sub-themes with examples will now be described. In all the material, we have replaced gender to help preserve anonymity.

Figure 2. Theme diagram.

Theme 1: Appealing content

This theme relates to the way that the coaches were effective at hooking in their clients by their credibility, uniqueness, and effective promotion of their service. The following subthemes were found:

1.1 Effective advertising

Participant O highlighted the contrasting assurances from their coach of a quick and guaranteed recovery from OCD with their services, versus claims of traditional therapy being slower progress and less effective:

‘They kept pushing it that after three, two weeks, you will be cured. That’s something they kept saying. You can go see a therapist once a week for as long for 6–7 months and maybe you’ll get better, or you can stick with us, and you’ll be cured from OCD’ [Participant O]

Others talked about the quality of the advertisements on Instagram and also said that they talked with what appeared to be high competency about OCD:

‘Her/his Instagram’s really like appealing and s/he’s very good at like, you know, s/he looks as though s/he gets OCD. And it, to be fair like, s/he, s/he, s/he talks about it really, really well’ [Participant H]

1.2 The coach having a lived experience of OCD

Several participants expressed their initial attraction to the service due to the coach having lived experience of OCD. There was some desperation for help, and some emphasised their willingness to overlook qualifications in favour of seeking help from someone who had experienced and overcome similar challenges firsthand:

‘That’s what hooked you in. Yeah. S/he’d been treated. S/he said he was recovered; s/he was fully recovered s/he said’ [Participant D]

‘I didn’t care that s/he wasn’t qualified at that point I was like s/he knows what I’m going through. S/he’s been through this, this his/herself, and s/he’s gotten through it. I need her/his um, her/his services, I guess’ [Participant N]

1.3 The accessibility of the service

In reflecting on their experiences, Participant J praised the convenience of daily text support, while Participant B highlighted their preference for accessible options over traditional in-person therapy due to perceived barriers:

‘But that availability with the, the daily text, that was fantastic’ [Participant J]

‘It just seemed very accessible to me … I think it was the kind of inaccessibility that threw me away from seeing someone in person who was qualified’ [Participant B]

In addition, there was the prospect of frequent support.

‘After the end of the webinar, s/he said, if you want to join a WhatsApp group with people who have OCD all around the world, like you can join it, and I was like, oh, cool, like, you know, I’ll be in a group you know setting’ [Participant A]

1.4 The coach advertises as an expert with an innovative treatment method

Participant I remembered the coach claiming to have rare insight into OCD, which gave the impression that they held special knowledge and control over their condition:

‘I remember her/him even saying there’s only a handful of people who truly understand OCD in the world. So, all of this language is like: I hold the key’ [Participant I]

‘And s/he was like hundreds of comments saying we’re the best place for OCD and no therapists compare to what we are doing. These people are a tiny number, look at the huge numbers who say we’re changing the game’ [Participant A]

Participant D highlighted that the treatment methods were poorly conducted and taught incorrectly.

‘s/he told me … that s/he’d been treating cancer patients, trauma patients. I’ve seen evidence later on with him/her claiming s/he can basically deal with anything psychologically using this Albert Ellis method. And I’m not even sure it is Albert Ellis’ method, but it’s a twisted version of his method’ [Participant D]

Theme 2: Vulnerability

This theme covered topics such as the vulnerability of person with OCD to being exploited by coaches who were unregulated. They were desperate for help and had become more cautious about seeking further help. The following subthemes were found.

2.1 Exploitation

Participant C describes a troubling dynamic where blame is shifted onto the client, suggesting they are not exerting an appropriate effort. This attitude fostered an environment of toxicity within the coach–client relationship:

‘It is the client’s fault and what might be happening is they’re not putting in the right amount of effort or they might not be putting in the right type of effort. So, then there will be conversations about that, which is basically abuse. You know, it’s very it’s very toxic. It’s very abusive’ [Participant C]

‘The promise that, that her/his therapy could help me succeed in my career, was something that he/she used to kind of keep me in her/his therapy’ [Participant B]

Participant K described their experience with exposure with the coach as lacking in meaningful support:

‘Or like you know, what to do after you’ve done exposures or any, any kind of guidance on that. It was just like okay, go do these, these exposures. Great. So that lasted all of about 15 minutes, and then s/he f****d off’ [Participant K]

Participants K and B further recount the misuse of exposure:

‘Then the other thing was s/he made someone do an exposure in the group, made this person say a racist word like, and everyone was like, going like, congratulations! You said the N word and that’s really good, because you’re scared of being a racist. It’s so weird how that logic worked’ [Participant K]

‘Like … s/he sent me porn. Um, like pornographic pictures to look at … Um, and s/he would say I think like … really weird stuff that I feel quite embarrassed to even say. Um. Like s/he, would like sexualise me as a form of exposure. well, s/he told me I should be masturbating as exposure’ [Participant B]

Participant N described the misuse of exposure for suicide-related OCD as well as the coach’s suggestion for participant N to stop taking medication:

‘s/he’s like, OK, so you’re terrified of killing yourself. So, what we’re going to do is we aren’t going to have a therapy session for 6 to 8 weeks … and you’re not going to go on your meds for 6 to 8 weeks. And yeah … s/he’s like oh, just watch these two docos on, um, suicide … So yeah, I watched them. Obviously it was like, quite distressing …’ [Participant N]

Participant N continues to explain the coach’s rationale for suggesting stopping medication and therapy.

‘s/he’s like … you have to bring yourself closer to that feeling of, like, the suicide. You know, like, you know, sit in that uncertainty of it. Like, if it happens, it happens, you know, how is it the worst thing in the world?’ [Participant N]

2.2 Desperation leading to use of the service

Participant I noted common experiences in therapy, where individuals receive talk therapy instead of exposure response prevention for OCD, leading to feelings of desperation:

‘So, people have a lot of adverse experiences in the NHS, um, or privately with therapists like you know, like I had talk therapists who aren’t trained to treat OCD with exposure and response prevention. And it’s more just talking about what their anxieties are. So, they come from that very desperate, feeling like they’re untreated, they’re, they’re untreatable or treatment resistant’ [Participant I]

2.3 Becoming more cautious seeking future treatment

Participant N emphasised the importance of having a clinician with the appropriate qualifications, having learned from personal experience:

‘Yeah, I spent like a, now I really look for like are they qualified firstly, because that actually f**king matters like, you know. Like they really need to be qualified because otherwise they’re just going from their own personal experience … But having said that, I, I think it has made it, it made me a lot more cautious of like, you know, believing anything like from influencers on the internet. But now, like, I just, I guess I’m more critical of it’ [Participant N]

2.4 Lack of regulation

Participant J noted the risk for vulnerable individuals paying for unhelpful services, emphasising the benefit of accountability within regulated therapy where unethical behaviour can be reported:

‘But, but there’s also is a risk, isn’t there, for vulnerable people. Being, paying a lot of money to someone that isn’t helpful, you know, just takes the money and then doesn’t come up with the stuff. But that’s the same for therapists really? But at least, at least you can complain to someone or have them struck off, or you know, asked to have some struck off if they’ve behaved really badly’ [Participant J]

Other quotes for the Vulnerability theme can be found in the Supplementary material.

Theme 3: Cult-like experience

This theme covered topics such as a cult-like environment and having a coach who was described as having a narcissistic character and was able to effectively deceive and control clients.

3.1 Cult-like environment

Participant B described a cult-like atmosphere in therapy, where trust in the coach’s infallibility led to isolation from external perspectives.

‘That’s why, you know the word kind of cult kind of keeps coming back to me … And I think it like he/she was a, definitely was a degree of like, brainwashing, um, in the sense that I thought that s/he was this person who, you know knew more than anyone and everything that s/he said was correct and s/he was going to make me better and so. Even if my parents’ kind of they did, you know, start picking up as I told them things they were like, this doesn’t sound right, but I would defend him/her’ [Participant B]

Participant A noted their coach’s tendency to reduce any input from outside sources:

‘S/he, you know, shuts you down from other outside sources’ [Participant A]

3.2 An influential and narcissistic character

Participant A noted the coach’s self-centred attitude, dismissing questioning, and aspirations for public recognition:

‘It’s all about her/him. S/he’s right and s/he’s the only one that has answers, and anyone else who questions her/him is wrong, because s/he would say things too, like, s/he’s like, I’m gonna do a TED Talk, I’m writing a book’ [Participant A]

Participant D perceived the coach as lacking compassion and elevating her/himself above others, even top psychologists in OCD:

‘My impression of her/him changed a lot over time, as I saw how s/he treated people who left as the exposures got a bit extreme. S/he didn’t seem to have any compassion. S/he felt it was like s/he thought it was a godlike figure. You know, it was a bit like s/he would put himself on a pedestal, and if we, if, s/he was never wrong, and s/he could debate about OCD with the top psychologists and wipe the floor with them s/he would say’ [Participant D]

3.3 Deception

Participant D recounted the coach’s assertion of treating diverse conditions beyond OCD. Participant C noted their surprise at the coach’s use of the word ‘cure’, something they had not heard before from therapists:

‘S/he treated OCD, s/he said, but s/he told me on the phone that s/he’d been treating cancer patients, trauma patients, erm, I’ve seen evidence later on with her/him claiming s/he can basically deal with anything psychologically’ [Participant D]

‘So the first thing that comes up is they’re using the word cure, right, which I’d never heard of, experienced, no therapist had ever said it was possible’ [Participant C]

3.4 A fear of retribution

Participant K expressed fear of retaliation from the coach after sharing personal information, which they stated evolved into an OCD-like obsession:

‘I was sh****ng myself leaving, because I told in this group and shared so much, I was terrified that s/he was going to use the things that I told them against me or somehow take, erm, revenge on me that like, that’s what I felt, and it actually became a little bit of an OCD thing. That s/he was going to like, attack me in some way and actually, from speaking to other people, that seems to be quite a common experience’ [Participant K]

Participant O reflected on the vulnerability they felt after their coaching, with similar fears to participant K of what the coach might do with their personal information:

‘It’s like I haven’t gone after them because they after you’ve gone through something like this with coaches and therapists, they’ve got your secrets. They’ve got your most intimate details and fears in a document on paper. So, it’s almost like you feel as though they’ve got them hostage if you do anything to upset or shake their tree, even if they’ve done you wrong’ [Participant O]

Theme 4: Complex peer relationship

This covers both positive peer support and the misuse of relationships with peers who had OCD. There were two sub-themes:

4.1 Misuse of peer support

Participants reflected on how the use of messaging group chats intended for peer support with others with OCD, led to communications that could ultimately worsen their symptoms:

‘They put you in a WhatsApp group and so it’s constant like [pause] Like it’s kind of like a support group, but it’s really just offering a lot of reassurance most of the time to OCD sufferers or giving them like, damaging advice?’ [Participant D]

‘But when you’re stuck in a group chat with 30 plus people who, who are not recovered, uh, giving you advice it’s a bit backwards because ultimately like no one really knows the real scientifically backed methods and tools to help. They’re just regurgitating what they’ve been told by ***, who, who doesn’t actually know how to treat OCD effectively’ [Participant I]

4.2 Positive peer support

One participant reported a positive experience with the messaging group chat as it fostered a sense of community:

‘Well, I did like the group aspect of the WhatsApp group. So, people in the WhatsApp group were great, and like, honestly, I thought it was like, so cool. I was talking to people from like, all around the world and I did make friends in the WhatsApp group. So, I was like, I mean, I liked the community aspect of it’ [Participant A]

The full data can be viewed in the Supplementary material.

Discussion

There have no previous reports of the experience of people with OCD with experience of unqualified coaches in the field. We interviewed 13 participants with self-reported OCD about their experience with five different unqualified coaches. We identified four main themes in 12 participants who reported a negative experience: (1) Appealing content, (2) Vulnerability, (3) Cult-like experience, and (4) Complex peer relationships. People with OCD are vulnerable to such exploitation and their experiences were often characterised as driven by a charismatic individual often in a cult-like environment. Participants described the coach’s unethical misuse of exposure and incorrect application of psychological theory, and being advised to stop medication and therapy. Furthermore, the reported claims of a ‘cure’ of OCD from coaches can mislead individuals, creating unrealistic expectations and potentially delaying effective care. However, there were some features of coaching that were identified as helpful, for example such as the encouragement from a daily text. This may be used in dialectical behaviour therapy (Oliveira and Rizvi, Reference Oliveira and Rizvi2018). There was a sense of community and belongingness that was fostered by a WhatsApp group for people with OCD. However, it was also noted that these WhatsApp group chats may have encouraged unhelpful communications between clients, such as reassurance seeking. Many individuals with mental health conditions may seek support online via forums but it may not be possible to adequately moderate private messaging groups compared with online mental health forums, meaning unhelpful communications may be more likely to occur. Peer support in a supportive environment where there is a moderator who receives could potentially be helpful. This is often found in OCD groups both online and that meet face-to-face.

Given the predominance of negative comments from participants, this suggests that the OCD community should be aware of unregulated coaches offering help and the risks associated with this. However, there may be some positive aspects to unregulated coaching which were not explored by participants. Indeed, one participant was pleased with the help of her coach. Coaches may also effectively work under the supervision of a therapist (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Baucom, Wheaton, Boeding, Fabricant, Paprocki and Fischer2013; Renshaw et al., Reference Renshaw, Steketee and Chambless2005). Equally there are helpful and unhelpful qualified therapists and our finding have similarities with poor practice in psychotherapy (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Parry, Hardy, Darling, Mason and Chambers2019). In a survey of patients’ experiences of psychotherapy, approximately 5% of patients reported a lasting bad effect from the treatment they received (Crawford et al., Reference Crawford, Thana, Farquharson, Palmer, Hancock, Bassett, Clarke and Parry2016). Estimates of ‘unwanted effects’, including long-lasting effects, of psychotherapy have ranged from 3 to 15% (Berk and Parker, Reference Berk and Parker2009; Mohr, Reference Mohr1995). On the part of the people providing mental health treatment, lack of empathy, under-estimation of the severity of the patient’s problems, negative counter transference, poor technique, high concentrations of transference interpretations, and disagreement with the patient about the therapy process are all associated with negative outcome. A coach or a therapist who is exploitative, overly narcissistic, patronising, uncaring, or inattentive (e.g. not remembering key details of the patient’s history) is especially likely to create an adverse outcome (Berk and Parker, Reference Berk and Parker2009). Some of our participants were in coaching groups online, which combined with a charismatic but confrontational coach who demands self-disclosure, emotional expression and change in attitudes is likely to lead to adverse outcomes (Yalom and Lieberman, Reference Yalom and Lieberman1971). There were, however, some new themes emerging in the coaches including fears of retribution, deception, and a cult-like environment. These characteristics of online coaches may particularly affect those who are most isolated and in desperation for seeking help.

Good practice is for therapists to receive supervision and attend continuous professional development (CPD). This is often a condition of their employment or accreditation. Unqualified coaches would not have received supervision from a qualified therapist or attended CPD. If a regulated clinician acts badly or incompetently, a person with OCD has the ability to complain to their employer or a regulator. If a coach acts badly or incompetently, then there is no recourse.

The study has implications internationally where it may be possible for anyone to call themselves a coach or a therapist and promote themselves on a website and in social media. In instances where there is less accessibility to regulated psychological treatment, it is plausible that a higher proportion of individuals may seek help for their symptoms through unregulated coaches, potentially posing substantial problems. There is therefore a need to provide appropriate and evidence-based treatments to these individuals in a timely manner. Furthermore, unregulated coaches may offer their services to individuals with other disorders, which poses substantial ethical issues. We recommend that coaches for psychological disorders should be regulated, attend CPD and work under the supervision of a qualified mental health professional. In the absence of regulation, people with OCD are advised to seek the help of a mental health professional that is registered with a professional body. The exact professional body will depend on the country. People treating OCD should be trained and accredited in CBT and receive regular supervision. Good advice on seeking a private or state mental health professional can be sought from OCD charities websites (International OCD Foundation, 2023; OCD Action, 2023; OCD UK, 2023). They highlight the importance of providing clients with a supportive structure that offers clear information, choice, and involvement in decision-making. Explicit contracting at the beginning of treatment and clarity about sessions and progress are also important in managing client expectations throughout. Opportunities for client feedback should be provided. There is no evidence that the participants in our study had any such safeguards. Only state regulation will be able to prevent unqualified and unregulated coaches from promoting their service. Furthermore, for services offering CBT with regulated therapists, long waiting lists or a previous unhelpful experience may lead individuals with OCD to seek help from alternative sources such as unregulated coaches. Such services could tailor education on evidence-based resources and strategies and highlight to patients the risks and potential vulnerabilities associated with unregulated coaching. This may empower patients to make more informed choices. Clinicians should consider routinely discussing any alternative supports patients are using or have used in the past. Public awareness campaigns should emphasise the credentials, ethical standards, and evidence-based practices that distinguish regulated professionals, further helping individuals with mental health problems such as OCD make informed choices.

Limitations

Inevitably this study will be influenced by the authors who are professionally qualified and regulated. The study came out by people with OCD who wanted to talk about their experience and help to warn other people with OCD. Individuals with more favourable and positive experiences of unregulated coaches may be less likely to take part in our study and our advertisements may have been biased to recruit people with negative experiences of coaches. All the interviews were, however, conducted by nursing staff who had not had prior contact with the participant. Four out of the 12 had had previous contact with the first author and were asked by him if they wanted to participate but did not conduct the interviews, thus minimising the chance of biasing the interview content due to prior discussions. We were limited by that fact that nine out of the 13 participants identified the same coach. Furthermore, some participants received both individual and group coaching, making it challenging to distinguish the unique impact of each format. Future research could consider using a two-arm design to separately examine the impact of individual and group coaching.

Another limitation of the present study is that participants had self-reported OCD and were receiving OCD treatment. However, all said they had been diagnosed by a health professional and had received treatment for OCD in the past. Our results might not be generalisable to the OCD population, who may have different experiences with unregulated coaches in general. Furthermore, the cross-sectional interview design meant we did not track changes in participants’ OCD symptoms, depressive symptoms, or quality of life over time. Given participants’ generally negative experiences, coaching may have been linked to worsening in some outcomes, but we could not capture this.

Finally, richer data on the content and nature of the coaching sessions and the impact that coaching had on the participants’ wellbeing and symptoms could have been elicited.

Future research

Future research could explore the experience of participants with diagnosed OCD when using unregulated coaching, how unregulated coaching impacts the severity of OCD symptoms, and whether participants report changes in their quality of life and functioning. A greater emphasis could be placed on identifying the reasons people sought coaching in the first place (as opposed to regulated therapy) and explore in greater depth the content and nature of the coaching sessions they received. For people who have received both regulated CBT for OCD and unregulated OCD coaching, their experience of both could be explored qualitatively in order to identify key differences in their perception of the different treatments.

Conclusions

In people with self-report OCD seeking treatment from unregulated coaches for their symptoms, we found that participants were generally negative towards their experience. This highlights a need for increasing awareness from patients and clinicians of the potential risks and disadvantages for patients when seeking treatment from unregulated coaches, such as exploitation and unrealistic coaching expectations from coaches of patients.

Key practice points

-

(1) Be aware that patients may turn to unregulated coaching for mental health support due to barriers in accessing regulated CBT. Such coaches may be exploitative and offer unrealistic expectations for recovery.

-

(2) Educate patients on the differences between evidence-based CBT and unregulated approaches, including the risks of claims promising ‘cures’ for conditions like OCD.

-

(3) Routinely enquire about any alternative mental health support that patients are using alongside CBT to identify possible conflicts in treatment approaches.

-

(4) Where possible, provide patients with interim evidence-based support options whilst on waiting lists, potentially helping to reduce the number of patients seeking support from unregulated sources.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X25000157

Data availability statement

Research data are not shared. Due to the personal nature of the questions asked in this study, all individuals who participated were assured that the data would be anonymised; the original full-length transcripts of the interviews are therefore not available to be shared outside of the research team.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

David Veale: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, review and editing; Jennifer-Elizabeth Lomax: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing review – original draft and editing; Michelle Cooke: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing review – original draft and editing; Charles Beeson: Methodology, Review and editing. Una Foye: Methodology, Supervision, Review and editing.

Financial support

This study presents independent research part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was received by King’s College London ethics board prior to commencement (reference number: LRS/DP-21/22-28535). Participants who were currently receiving treatment by a mental health professional were asked to liaise with them before consenting to participation to ensure that the interviews did not impact on the therapy they were receiving.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.