Introduction

Depression and anxiety can affect up to one-fifth of the population in high-income countries worldwide (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas and Walters2005). From 2008 the Irish economy was in recession with national debt increasing from 20% of GDP in 2007 to 84% of GDP in 2012 [Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), n.d.] (https://www.esri.ie/irish_economy/). Many people are still affected by the financial implications of the 2008 crash. Research evidence suggests that economic recession is likely to impact those with pre-existing mental health problems as well as creating new mental health problems among people with financial problems (Mental Health Commission, 2011; Wahlbeck and McDaid, Reference Wahlbeck and McDaid2012). Men may be particularly affected (Gili et al., Reference Gili, López-Navarro, Castro, Homar, Navarro, García-Toro and Roca2016). Among men, job loss had a major negative impact on mental health during the recession (Barbaglia et al., Reference Barbaglia, ten Have, Dorsselaer, Alonso and de Graaf2015), as did long periods of unemployment (Aguilar-Palacio et al., Reference Aguilar-Palacio, Carrera-Lasfuentes and Rabanaque2015).

Self-help and psychoeducational groups as well as cognitive behavioural therapy are recommended for depression and anxiety [National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2011]. However, stigma is an issue that affects the uptake of mental health services, by men in particular (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko, Bezborodovs and Thornicroft2015). There is research evidence to suggest that those with stigmatising attitudes towards mental health problems are less likely to seek help for themselves (Cooper, Reference Cooper2003). Men may be less likely to seek help for mental health difficulties than women (Cleary, Reference Cleary2017; Lynch et al., Reference Lynch, Long and Moorhead2016). In a study on male suicide, 74% of women with depression reported that they had spoken to someone about it; the figure for men was much lower at 53% [Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM), 2015]. Important implications for service delivery following on from this research include exploring the delivery of services outside settings people associate with ‘mental illness’ and examining how to connect with hard-to-reach groups such as males (Reavley and Jorm, Reference Reavley and Jorm2013). Additionally, one recent study found that Irish men viewed mental health services as ‘inadequate, over-stretched and over-medicalised’ (O’Donnell and Richardson, Reference O’Donnell and Richardson2018; p.15). In their recommendations the Sax Institute cite the advantage of schools, tertiary education settings and workplace interventions in being more likely to reach males (Reavley and Jorm, Reference Reavley and Jorm2013). Working in an informal environment and using non-stigmatising terminology have also been cited as two key factors in engaging men in mental health services (O’Donnell and Richardson, Reference O’Donnell and Richardson2018).

‘Stress Control’ is a psychoeducational group-based intervention for anxiety and depression in adults. It employs a cognitive behavioural model and was designed by clinical psychologist Dr Jim White to address the issue of stigma preventing access to mental health services. Research evidence suggests that Stress Control and other large-scale didactic interventions are beneficial and cost effective for people who experience mild to moderate mental health problems (Delgadillo et al., Reference Delgadillo, Kellett, Ali, McMillan, Barkham, Saxon and Lucock2016; Main et al., Reference Main, Elliot and Brown2005). A randomised controlled trial (White et al., Reference White, Keenan and Brooks1992) found ‘Stress Control’ to have benefits similar to individual treatment methods for participants with generalised anxiety disorder. Wood et al. (Reference Wood, Kitchiner and Bisson2005) found that attending Stress Control led to significant improvements in anxiety, psychological wellbeing and depression for participants attending a variety of secondary care mental health services. Reductions in symptoms of stress, depression, anxiety and worrying have been found following attendance at Stress Control (linear trends p < .05), with gains maintained at 6 months and at 1-year follow-up. Participants for this study were recruited broadly including via local press and sports clubs (Van Daele et al., Reference Van Daele, Van Audenhove, Vansteenwegen, Hermans and Van Den Bergh2013). These studies highlight the potential for Stress Control to be a useful intervention for a number of common health difficulties and for the general population, as well as participants attending mental health services.

An important consideration in models of service delivery is cost effectiveness or best buy models of intervention. Characteristics of best-buy interventions include reach, affordability, feasability and flexibility [World Health Organization (WHO), 2011]. It is important to recognise that the research on the delivery of mental health interventions in unconventional settings is in its infancy (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Landsverk, Aarons, Chambers, Glisson and Mittman2009) and there are no controlled trials of best interventions demonstrating utility, scalability and impact relative to treatment as usual (Kazdin and Rabbit, Reference Kazdin and Rabbit2013).

The delivery of Stress Control in partnership with the Gaelic Athletic Association Healthy Clubs (GAA, 2013) can be seen within the context of a model of delivery in unconventional settings and as a best buy intervention. The GAA is an Irish and international amateur sporting and cultural organisation, with a large male membership, which promotes Gaelic games including football, hurling and camogie. In terms of research on delivering interventions in sporting organisations, Spandler et al. (Reference Spandler, McKeown, Roy and Hurley2013) reported increases in self-esteem, confidence and positive coping skills following a UK-based group therapeutic intervention for men that used soccer venues and sporting metaphors. In an Irish context, the Healthy Clubs initiative aims to support GAA clubs all over Ireland and beyond in promoting the health and wellbeing of their members and the wider community. This initiative provided a unique opportunity to evaluate the implementation of an evidence-based intervention delivered within a novel model of service delivery. With this in mind, the current study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of a Stress Control intervention delivered in partnership with the GAA in ameliorating mental health difficulties in a general population.

Method

Research design

A qualitative and quantitative research approach was employed in the current study. Outcome measures were administered before and after the Stress Control course to evaluate the impact of the intervention on participants’ levels of depression and anxiety and their overall quality of life. Additionally, semi-structured group interviews (focus groups) were conducted to gather further insights into participants’ experience of the Stress Control course

Methodology

All participants completed a questionnaire at the start of session 1 (Time 1) and at the end of session 6 (Time 2) of the Stress Control course. The questionnaire gathered basic demographic information (gender, age and employment status), general health information (smoking and exercise behaviours) and information about stress management skills. It also included four standardised measures that assessed feelings of depression, anxiety and perceived quality of life.

Brief Version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Scales (WHOQOL-BREF)

The WHOQOL is a 26-item measure that yields quality of life scores across the four domains of: physical health, psychological, social relationships and environment (WHOQOL Group, 1998). Items such as ‘How satisfied are you with your health?’ are rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The WHOQOL-BREF has satisfactory psychometric properties of reliability and validity based on tests of internal consistency item-total correlations, discriminant validity and confirmatory factor analyses (Skevington et al., Reference Skevington, Lofty and O’Connell2004).

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

The HADS is a 14-item measure of anxiety and depressive symptoms (e.g. ‘Worrying thoughts go through my mind’ rated on a 4-point Likert scale) developed for use in a general medical population (Snaith and Zigmond, Reference Snaith and Zigmond1994). However, the measure is also suitable for use in the general population (Smarr and Keefer, Reference Smarr and Keefer2011). Tests of reliability and validity as well as sensitivity and specificity demonstrate that the HADS performs well in several populations including primary care patients and the general population (Bjelland et al., Reference Bjelland, Dahl, Tangen Haug and Necelmann2002; Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Crawford, Lawton and Reid2008).

Patient Health Questionnaire-Depression Scale (PHQ-9)

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item measure of depression severity validated in primary care and medical populations (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001). Psychometric properties including measures of reliability and validity are considered robust for the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams and Löwe2010). Respondents are asked to rate on a 4-point Likert scale how much they have been bothered by symptoms such as ‘Little interest or pleasure doing in things’ over the past 2 weeks.

General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 is a 7-item scale developed as a screening and severity measure for generalised anxiety disorder validated in a primary care population (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006). Psychometric properties for detecting anxiety are satisfactory for the GAD-7 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams and Löwe2010). Respondents are asked to rate on a 4-point Likert scale how much they have been bothered by symptoms such as ‘Not being able to stop or control worrying’ over the past 2 weeks.

Focus group

The focus group consisted of nine people (six females, three males; age range 43–62 years) who discussed their experiences of the implementation model and how the intervention could be improved in the future. The facilitators guided the participants through specific topics and used follow-up probes where appropriate. The focus group lasted for approximately one hour and was audio recorded. The recordings were anonymised and were stored securely on an encrypted computer for analysis.

Procedure

The 6-week Stress Control Course was implemented via a partnership between the GAA and the Health Service Executive (HSE) under the unifying title of ‘Cork Beats Stress’ at two separate locations in County Cork (one course was run in each location). Participants were recruited for the course via local and national media campaigns, direct promotion to HSE employees, local university staff, a national business group and GAA club members. The intervention was delivered by HSE primary care psychologists. Participants were all aged 18 years of age and older. There were no other inclusion or exclusion criteria.

Data analysis

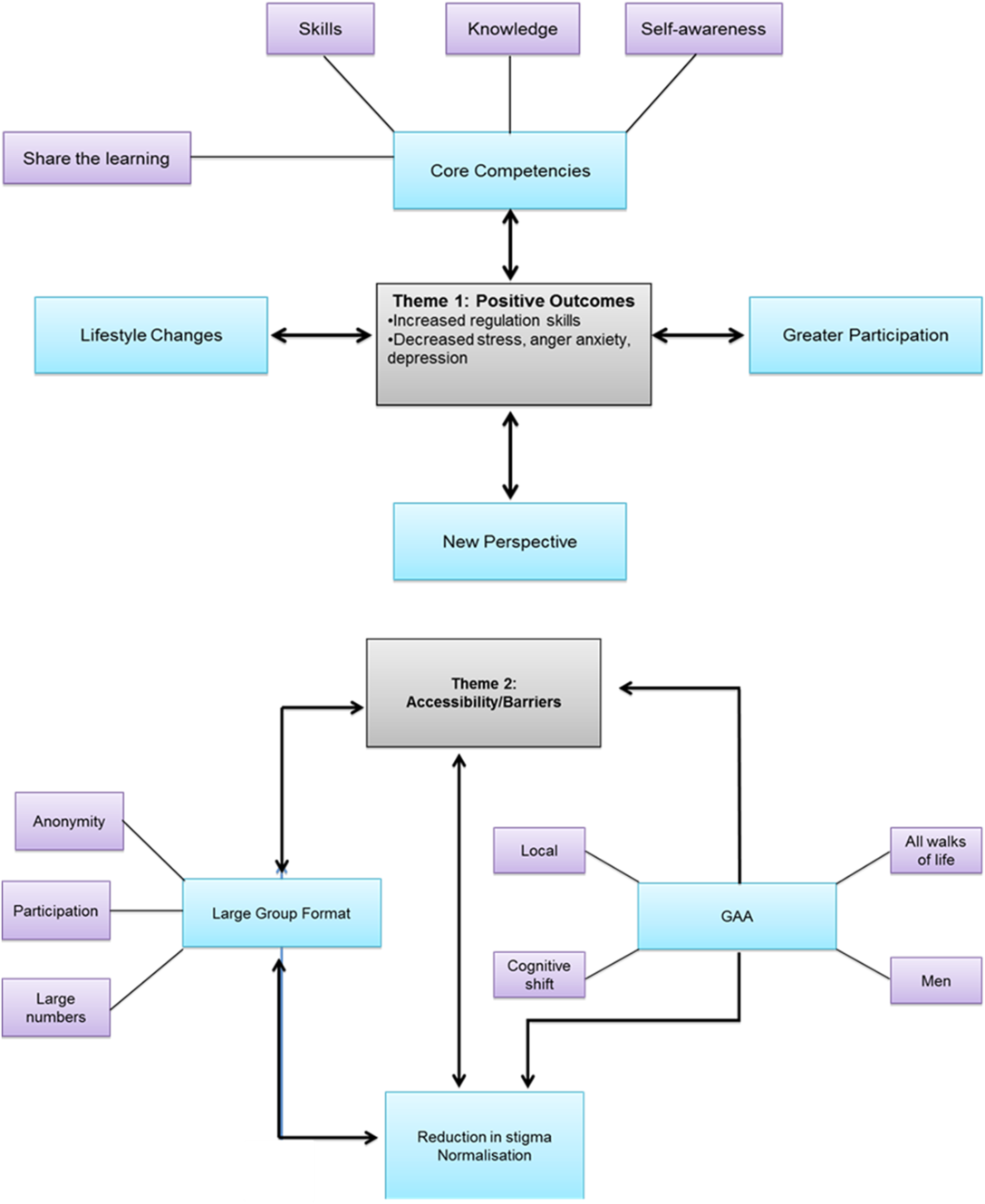

Ten per cent of questionnaire data was randomly selected to evaluate the accuracy of data entry. Descriptive statistics and quantitative data analysis techniques were used to describe patterns and trends in the questionnaire data, where appropriate (e.g. univariate analysis of variance, t-tests, Wilcoxon signed ranks, McNemar). Where multiple comparisons were made, a Bonferroni correction was applied. The transcripts generated from the focus groups were analysed by three team members using a thematic analysis, a qualitative method used for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). On analysis of the focus group interviews, a coding framework was devised. The key themes and subthemes emerging from the data were identified and labelled (see Fig. 1 for a summary).

Figure 1. Summary of key themes and subthemes emerging from thematic analysis of qualitative data.

Results

Sample

There were no significant differences in the demographic characteristics, in the proportion of stressful personal or family changes over the previous 12 months, in the formal help-seeking history or in the baseline levels of anxiety, depression or perceived quality of life in the Stress Control attendees at the two venues (all p > 0.05). Therefore, the data from the two venues were pooled to increase the statistical power for all additional analyses. On average, 246 people (range: 211–328) attended the Stress Control course each week across the two sites. Out of the 265 attendees who completed a questionnaire, n = 147 (55.5%) attended the course at one venue and n = 118 (44.5%) at the second venue. One hundred and ninety-eight participants completed a questionnaire at Time 1 and of these, 102 (52%) also completed a questionnaire at Time 2. Seventy-five per cent of respondents were female and 57% were aged between 41 and 60 years. While only 25% of the current sample was male, this represents a considerable improvement in male attendance which is typically 11% at non-GAA-linked Stress Control sites (see Table 1 for a summary of demographic information). Just over one-third of respondents had seen a mental health professional over the course of their lifetime and people were most likely to rate work, financial worries and day-to-day hassles as their most prevailing stressor. Participant self-reported scores on the PHQ-9 (depression) were higher in this study compared with general population studies (31% above clinical cut-off compared with 8.6% (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Strine, Spitzer, Williams, Berry and Mokdad2008). The anxiety levels at Time 1 were comparable to those found in general population studies employing the GAD-7 (23 and 22.5%, respectively; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006). Self-reported quality of life was higher in comparison with general population studies (with 52% of participants in the current study reporting that their quality of life was ‘good’ at Time 1 compared with 43.4% (Skevington et al., Reference Skevington, Lofty and O’Connell2004).

Table 1. Summary of demographic data, formal help-seek history and stressors for Stress Control attendees at the two venues

Impact of the Stress Control intervention on levels of depression, anxiety and perceived quality of life

Stress Control intervention results in lower levels of depression

Of the 102 attendees who completed the questionnaire at Time 1 and Time 2, 95 (93%) completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) at both time points. A paired-samples t-test indicated that the Stress Control intervention resulted in a decrease in HADs depression scores from Time 1 (mean = 6.41, SD = 3.69) to Time 2 (mean = 5.52, SD = 3.74; see Table 2), with the eta-squared statistic (0.5) indicating a large effect size. The reduction in the depression score on the Patient Health Questionnaire-Depression Scale (PHQ-9) was also significant, with more participants falling in the none–minimal or normal depression range following the Stress Control intervention (see Table 3).

Table 2. Summary of scores on Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) prior to and following the Stress Control intervention

aDependent samples t-test. bThis clinical cut-off is taken from ‘The Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review’ by I. Bjelland, A.A. Dahl, T.T. Haug and A. Necklemann (2001), Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52, 69. cMcNemar test.

Stress Control intervention results in lower levels of anxiety

The intervention also resulted in a decrease in HADS Anxiety scores from Time 1 (mean = 9.77, SD = 3.96) to Time 2 (mean = 8.12, SD = 3.83; see Table 2). An analysis of the impact of the intervention on anxiety severity classification revealed that there was an increase in the number of participants in the normal and mild categories from Time 1 to Time 2, and a concurrent decrease in the number of participants in the moderate and severe ranges from Time 1 to Time 2. There was a decrease in participants’ generalised anxiety scores following the intervention. While the mean GAD-7 scores were in the mild range at Time 1 and Time 2, there was a significant increase in the number falling in the normal range following the intervention (see Table 4).

Stress Control intervention results in higher perceived quality of life

Self-reported quality of life in the physical health, psychological health and environment domains all improved following the intervention. Although there was a concurrent increase in mean scores in the social relationships domain, the result did not reach statistical significance (see Table 5).

Table 3. Summary of scores on Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-9) prior to and following the Stress Control Intervention

Time 1, baseline; Time 2, end point. aDependent samples t-test. bThe clinical cut-off of 10 is at the moderate level of depression severity. This clinical cut-off is taken from the Instruction Manual: Instructions for the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) and GAD-7 measures. cMcNemar test. dFinal item on the PHQ-9, which is a single rated patient difficulty item: ‘How difficult have these problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people?’.

Table 4. Summary of scores on GAD-7 prior to and following the Stress Control intervention

GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder (7-item scale); Time 1, baseline; Time 2, end point. aWilcoxon signed ranks test. bThe clinical cut-off of 10 occurs at the moderate level of anxiety severity. This clinical cut-off is taken from the Instruction Manual: Instructions for the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) and GAD-7 measures. cMcNemar test.

Table 5. Summary of scores on Brief Version of the World Health Organisation Quality of Life Scales (WHOQOL-BREF) following the Stress Control intervention

Stress Control intervention results in enhanced personal skills/coping strategies and knowledge of stress

Participant’s mean self-reported personal skills/coping strategies and knowledge of stress increased following the intervention with the exception that participants did not report feeling significantly more self-confident at Time 2. The proportion of participants who reported using personal skills/coping strategies ‘mostly or always’ increased following the intervention. Participants also reported having a greater knowledge of their stresses, of the impact of their stress upon them and of how to effectively contend with the stress (see Table 6 for a summary).

Table 6. Summary of scores on personal skills and knowledge of stress following the Stress Control intervention

aDependent samples t-test or the non-parametric equivalent was used, where relevant.

Thematic analysis of qualitative data

The following sections outline the main themes and subthemes emerging from analysis of the interview data (see Fig. 1 for summary).

Theme 1: Positive outcomes

1. Lifestyle changes

Participants identified positive lifestyle changes that they had made following the Stress Control course from general self-care to making specific changes that help to combat stress such as exercise:

‘You are more conscious of doing good things for yourself.’

‘…And it’s only a 5K walk in fairness but you know I probably wouldn’t even have done that or looked into doing that before I did the course.’

2. Greater participation

The participants also reported trying out new activities following Stress Control:

‘I would never have thought about … going into a focus group before I actually did this course about stress.’

‘…It’s [Stress Control] given me a different way of looking at things and saying why not and getting out of my comfort zone.’

3. New perspective

Participants identified a change in perspective on stress in general. Participants were empowered to change negative thoughts and distressing emotions to taking a more positive or helpful outlook:

‘Sometimes in work I was very negative… I’m more positive about it all now and taking a different approach.’

‘The whole thing [Stress Control] has changed my view towards it all and I’m not frightened by it [stress] all.’

4. Core competencies

Participants reported acquiring a new set of skills which helped them to better contend with their stress. For example, they felt that the Stress Control course helped them to develop a better understanding of stress and increased self-awareness. Participants enjoyed sharing the Stress Control learning experience with those around them.

Skills

Skills refer to participants’ practical strategies for managing stress (a ‘tool kit’) which includes thought challenging, breathing retraining and compassionate self-talk:

‘It was like the tool kit when you need them they are there.’

‘I am wound up like a ticker but it was just taking a breath and saying ok, so is half the community and you have the tools now for it.’

‘I thought that the sections … about challenging your thoughts I really found that fantastic, on a practical level you know and carrying through and following it.’

‘You berate yourself if you’re not feeling good on a day but it’s ok not to you know and just accepting it yourself.’

Knowledge

The course equipped participants with knowledge about what stress is and how common it is, as well as practical information about the impact of caffeine and exercise on their levels of stress. The factual information along with the skills taught at Stress Control facilitated participants to make positive lifestyle changes:

‘One of the main things for me was to understand stress and finding out that I had stress.’

‘Well the thing I found really, really good and that was about drinking … not so much alcohol but things like coffee.’

‘I found then it was all the knock-on effects … from exercise which is so important to stress you know, it incorporates food … I’m just more conscious of everything.’

A further effect of knowledge was in facilitating participants’ self-awareness of their stress levels:

‘I mean for me personally all the time I thought there was something wrong with me … I found out exactly what was wrong down to the knowledge of the course.’

Participants talked about being able to share the skills and knowledge from Stress Control with others in their lives. Examples included lending the (relaxation) CD to others and modelling skills such as self-praise and thought challenging:

‘I have given the CD … to people.’

‘With my kids… I’ll praise them and I say praise yourself you’re after doing a great thing there whatever it is, you know.’

‘The girls say to me Mam I’m scared because of an exam tomorrow… and I say… do what you can do and if you don’t get anything what about it, in five years’ time we will all been after moving on.’

Self-awareness

One application of the course content was for participants to reflect on how it related to their own situation including becoming aware of their own stress, understanding the factors that can contribute to stress (anxiety and depression) in Irish society and the idea of becoming your own therapist:

‘I came to the course for a different reason and during the course I found that I had stress.’

‘We are very reluctant to self-praise.’

‘We can all help ourselves out of it.’

Theme 2: Accessibility/barriers

The second primary theme to emerge from the data was Accessibility/barriers, which was divided into further subthemes (1) GAA, (2) large group format and (3) de-stigmatisation of stress. These subthemes are factors identified by participants, which increased the accessibility of the Stress Control course and reduced the barriers to accessing the course. The GAA subtheme consisted of four components: Men, All walks of life, Local and Cognitive shift. The large group format subtheme consisted of three components: Anonymity, Participation and Large numbers.

1. GAA

Participants reported that the GAA being a community-based organisation contributed directly to the accessibility of Stress Control:

‘The GAA is a big part of the community.’

‘I thought it was a stroke of genius to be honest to link up with the GAA it works because it is so widespread.’

Men

According to participants, delivering Stress Control in partnership with the GAA was a critical factor in facilitating men to attend the course:

‘I think it’s [GAA] a good target because it … the whole idea of stress, mental health … it’s still a big taboo and there’s more of a taboo with [the] male side of it.’

‘I think bringing [it] into such a male dominated situation as well I just thought did an awful lot really.’

Delivering the course in what may be seen as a male-orientated environment may also have had the effect of reducing stigma for men in accessing a mental health intervention, thereby increasing accessibility for men.

All walks of life

Another theme evident in the data related to the GAA was that the organisation’s membership consists of people drawn from all facets of Irish society:

‘I think the GAA is unique in so far as you could have people from every walk of life in the GAA and still be sitting at the bar or talking to each other, or playing.’

Local

An important benefit of delivering the Stress Control with the GAA reported by participants was that it was based in their local community. Participants reported that it reduced the physical demands on them in terms of travel:

‘I didn’t have to drive so far.’

However, a key effect for participants appears to have been the impact in normalising stress and reducing stigma that may be attached to attending the Stress Control course locally:

‘Meeting as a group and it helped and the GAA I think the two of them mixed together takes it away from that stigma you know and makes it more visible more normal more sociable.’

‘…And I thought oh yea that’s quite good for the GAA, and like I said when I came in half the parish was there and then I said oh they’re not from the HSE [Health Service].’

Cognitive shift

It appears that delivering the course with an organisation embedded into the local community facilitated a cognitive shift for people in how they thought about common mental health problems such as stress, anxiety and depression, shifting the focus to well-being from an illness model:

‘I think it does normalise it because it rounds it, in my own opinion is that if it was coming directly from the HSE not linked to any kind of sport is kind of perceived as there [is] something wrong with you.’

‘When you announced it was in conjunction with the GAA I thought oh yea because it is all opening up that psychology thing you know and that people are linking it with health and fitness and you know out there and all the rest.’

2. Large group format

Delivering a group format intervention appeared to have impacted directly on accessibility and also operated to reduce stigma around seeking help for mental health problems and normalised the experience of stress:

‘You would have just thought about it but just to have somebody else expressing it and everybody else is there as well and you can see nodding heads.’

Stress Control is delivered in a didactic or lecture format to groups. Prior to the course those who had registered would have received an email explaining this format and that there would be no participation from attendees, a component identified by focus group participants as being critical to their accessing the course.

Participation

‘I know for me it was actually just going to some place and actually not having to take part.’

‘There would be no participation and she found that really beneficial.’

Anonymity

Furthermore, participants identified the anonymity of being in a group and not having to engage directly with the psychologist as also being important:

‘From my perspective the anonymity part of it was absolutely critical that I could just go and I could be in that situation and not have to talk to anybody and not have to say anything.’

Attendance at both venues was high, which surprised some of the focus group participants. Participants cited the large numbers as a component of the group format that helped to remove the stigma of attending Stress Control and normalise the experience of stress:

‘I couldn’t believe there were so many people.’

‘When I walked in there was my neighbor then there was my other pal from church and then I could see half the parish there and actually that very point in itself was actually very comforting … it was so nice to know, actually we are all here for the same thing, it was really powerful … I wasn’t afraid to tell people that I was doing it, and lots of people said I going to send so and so to that.’

3. Reduction in stigma/normalising the experience of stress

One of the key outcomes from the thematic analysis is that the reduction in stigma and normalising of the experience of stress were key factors in making the Stress Control course accessible for participants. As outlined, there were aspects related to the course content and format that reduced stigma. In addition, the community-based model of delivery in partnership with the GAA was critical. We will discuss these further in the next section.

‘I think it was the normalisation of everything showed that everybody had this.’

‘Everybody has it [stress] and almost every aspect of all courses shows how normal it all was you the more severe parts of it came across as been so normal.’

Discussion

Overall, both quantitative and qualitative findings demonstrate that participants experienced a reduction in levels of symptoms of anxiety and depression by the end of the 6-week course. As well as reducing mental health problems among the study population, the Stress Control intervention also increased self-perceived quality of life in the domains of physical health, psychological health and environment. Although the group mean in the social relationship domain increased from the beginning to the end of the course, the increase was not statistically significant.

That the Stress Control intervention can increase well-being is further evidenced by self-reported increases in participants’ life skills, coping strategies and knowledge of stress. Participants did not appear to gain skills in behavioural strategies such as decrease in the use of avoidance as a coping strategy. Reducing avoidant behaviours may require further support to implement, such as the modification of environmental factors. On average, participants did not report feeling more self-confident by the end of the course, which may also be attributed to the short duration of the intervention.

An unexpected finding was that participants shared the learning from Stress Control with others in direct and indirect ways, such as passing on the relaxation CD to others or in providing informal psychoeducation in how they spoke about stress to others, including their own children. This is a positive finding in terms of the reach of the intervention and strengthening the capacity of the community to provide informal support for common mental health problems. Along with high levels of attendance, the level of reach of the Stress Control intervention through participants sharing the learning indicates high levels of acceptability for the course.

The results of the current study are comparable to the randomised controlled trial of Mino et al. (Reference Mino, Babazono, Tsuda and Yasuda2006), where a CBT-based workplace stress management programme led to a significant improvement in symptoms of depression. However, the group size was much smaller compared with the current study (n = 58). Tan et al. (Reference Tan, Wang and Modini2014) reported in their meta-analysis that there is robust evidence that workplace mental health interventions can reduce the level of depressive symptoms among workers. They highlighted that there is more evidence for CBT-based programmes than for other interventions.

Evaluation of delivering Stress Control in partnership with the GAA

Focus group participants identified accessibility as a key outcome of delivering Stress Control in partnership with a sports organisation. The GAA as the social network for delivering the course and the large group format were the two factors participants identified that increased the course’s accessibility and reduced some of the barriers attached to accessing mental health interventions. Accessibility increased in two ways: first, there were structural factors related to the course and the model of delivery; second, social-cognitive factors related to the course and model of delivery operated to reduce stigma.

Structural factors that made the course more accessible were that the GAA is a local organisation and that membership consists of people from diverse backgrounds. Therefore, the burden on participants was lowered as they did not have to travel long distances. It is also important that the course was free of charge, which was highlighted by participants in the focus group. As financial worries were a top stressor for participants, this fact is worth highlighting. It is notable that these participants also displayed many factors which may be considered protective of good mental health including employment and high educational attainment. It is possible that there is a new cohort in Irish society experiencing mental health difficulties as a result of changes in financial, employment and social status.

The attendance rate for men in the current study was just above 25%, which represents an increase from the average attendance rate of 11% for males in HSE clinic settings in Cork. The quantitative data indicated higher rates of men attending the course compared with other community and health settings in Cork, which is supported by recommendations in the literature (Reavley and Jorm, Reference Reavley and Jorm2013). Delivering the course is partnership with an organisation with high levels of male membership may have had the effect of reducing stigma for men in accessing the course, thereby increasing accessibility. Embedding the course in a local sporting organisation appeared to shift the focus of the course from an illness to a well-being model, which would have removed the need for label avoidance (Corrigan, Reference Corrigan2004) among the population. Stigma reduction was one of the key recommendations of the Middle-Aged Men and Suicide report (O’Donnell and Richardson, Reference O’Donnell and Richardson2018) which also highlighted the value of avoiding complex language and using community and partnership based approaches. The current research meets a number of these recommendations.

Implications for service delivery and clinical practice

The methodology of this project provided a road map for health services and community organisations in the implementation of community-based models of mental health service delivery. The outcomes achieved support the use of a large group-based intervention for common mental health problems among adults from a treatment effectiveness and affordability point of view. These findings challenge services and professionals to reconsider their perceptions of what constitutes clinical practice and established ways of working and to engage with a more community-based, partnership approach to providing services.

The data suggests that Stress Control was effective for participants scoring in the mild range for anxiety and depression. Participants in the moderate/severe range did improve but are likely to need further intervention at the end of the course. There is a rationale for providing follow-up sessions and links to follow-on services. A final consideration for service delivery is that only five people who were younger than 30 years of age participated in the evaluation, suggesting that further work is needed to extend the reach of Stress Control to younger people.

Policy implications

This study progresses the aim of Ireland’s key mental health policy document ‘Vision for Change’(Government of Ireland, 2006) in developing a community-based model of service delivery. It is important that it has overcome many of the barriers to the delivery of community-based services including system inertia and lack of resources. Policy makers need to consider the merits of greater emphasis on large-scale interventions and a move away from over-reliance on one-to-one treatment approaches.

Research implications

This study provides a major contribution to the growing field of implementation research. It is the first study to evaluate the delivery of a mental health intervention in partnership with a sporting organisation in Ireland. The findings demonstrate the scalability, affordability and effectiveness of Stress Control, an evidence-based intervention, in the context of a novel, community-based model of service delivery. An interesting avenue for future research would be to investigate factors affecting participation rates. It would be interesting to see whether male attendance in particular would increase over time through delivery in organisations with high male membership such as the GAA. However, a crucial area for development would be to investigate factors that affect participation by younger people.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations in the current study, including the lack of a control group and the absence of longitudinal data (i.e. at 6- and 12-month follow-up). The research sample is also not likely to be representative given that participants self-selected by registering to participate in the intervention. The current study did not measure the rate of drop-out and possible reasons for this. The potential for unwanted effects of attendance needs to be explored. Efforts were taken in line with recommendations from Roback (Reference Roback2000) to avoid this (e.g. encouraging participants to have realistic expectations of the intervention), and there was signposting of participants to other services and resources as needed. However, the research did not specifically explore unwanted treatment effects.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study found that accessible psychoeducational interventions such Stress Control, delivered in contexts outside hospital or health service settings, demonstrate potential to have significant benefits for the mental health of the general population. A higher proportion of men attended Stress Control delivered as a large-scale intervention in partnership with the GAA, a national sporting organisation, compared with clinic settings. Delivering the course to the general population may have uncovered a new cohort experiencing mental health difficulties within the Irish population following years of economic recession. Levels of anxiety and depression were lower following participation in the intervention. Attendees also reported increased quality of life as well as other positive lifestyle changes. Delivering Stress Control in partnership with the GAA made psychological intervention accessible for a larger number of people than would be possible through traditional modes of service delivery. While physical aspects of accessibility were critical (the course was on in the evening, it was local, it was free) the most important aspect of accessibility was the reduction in stigma and normalisation of the experience of common mental health problems, thereby allowing more people and more men to access the service.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the hard work of the GAA club members in bringing this project about.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statements

The authors have abided by the Psychological Society of Ireland (PSI) Code of Ethics. The research was ethically approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals, reference number: ECM 4 (u) 07/01/14.

Key practice points

(1) Collaboration with community sports organisations has multiple benefits for delivering public mental health educational interventions.

(2) The large scale and location of the Stress Control interventions in this study served to increase male attendance and help to normalise the experience of stress.

(3) Local settings were also key to accessibility for attendees.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.