Introduction

Co-morbid mental health diagnoses are common, with studies estimating co-morbid diagnosis in approximately 22–27% of cases (e.g. Cairns, Reference Cairns2014; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler and Walters2005). Co-morbidity presents a challenge for services such as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), which are often structured around delivering disorder-specific models of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT). Processes such as intolerance of uncertainty (IU) appear both disorder specific (e.g. generalised anxiety disorder, GAD; Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur1994) and transdiagnostic in the maintenance of difficulties including social anxiety disorder (SAD; Mahoney and McEvoy, Reference Mahoney and McEvoy2012), panic disorder (PD; Carleton et al., Reference Carleton, Duranceau, Freeston, Boelen, McCabe and Antony2014), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD; Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Cohen1998), major depressive disorder (MDD; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Fontes and Marroquín2008) and psychosis (Mawn, Reference Mawn2018). IU ‘is an individual’s dispositional incapacity to endure the aversive response triggered by the perceived absence of salient, key, or sufficient information, and sustained by the associated perception of uncertainty’ (Carleton, Reference Carleton2016; p. 31), even in the absence of perceived threat or potential negative outcome. IU scores are higher in patients experiencing SAD, PD, GAD, OCD and MDD compared with normative samples (Carleton et al., Reference Carleton, Norton and Asmundson2007; Mahoney and McEvoy, Reference Mahoney and McEvoy2012).

Transdiagnostically, shared mechanistic processes are important to conceptualisation because they are associated with distress across diagnoses (Norton and Philipp, Reference Norton and Philipp2008). Some researchers have proposed that IU would probably improve following transdiagnostic CBT (e.g. Carleton, Reference Carleton2016). Talkovsky and Norton (Reference Talkovsky and Norton2016) provided initial research evidence to support this theory, finding that implementing transdiagnostic group-based CBT for anxiety decreased IU significantly following treatment. Decreases in IU predicted improvements in clinical presentation across diagnoses. Boswell et al. (Reference Boswell, Thompson-Hollands, Farchione and Barlow2013) investigated the impact of transdiagnostic CBT, observing a medium to large effect size in the reduction of IU. Targeting IU in interventions may be of benefit to both individual and co-morbid presentations; proof of concept has been established using single strand IU interventions in single case design research (Askey-Jones, Reference Askey-Jones2018; Tiplady et al., Reference Tiplady, Freeston and Meares2017).

The following article outlines the development and piloting of an approach targeting IU in a transdiagnostic CBT group setting: the ‘Making Friends with Uncertainty’ (MFWU) group. The conceptual underpinnings of the approach are presented, as well as therapist experiences of developing and refining a novel intervention within an IAPT primary care service setting.

Development

The group was developed in liaison with two clinical psychologists, one CBT therapist and researchers via ongoing collaborative research between Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (NUTH) and Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear Foundation Trust (CNTW). We sought diverse experiences by including those that were actively working with patients in the primary care setting as well as those with experience of group development and expertise in IU. The intervention approach was initially trialled by two researchers in one-to-one format with n = 6 patients, which aimed to increase tolerance of uncertainty and achieve symptomatic relief (e.g. Askey-Jones et al., Reference Askey-Jones, Tiplady, Thwaites, Meares and Freeston2017; Tiplady et al., Reference Tiplady, Freeston and Meares2017). This research suggested that single strand IU treatment could create clinically significant change (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) in people with anxiety disorders, which was sustained at 3-month follow-up. Refinements of this treatment are ongoing.

Following deciding on the approach (outlined below), we consulted a panel of experts via a special interest group (SIG) with respect to content, number of sessions, pacing and focus of each session. Permission was sought to implement groups as part of a standard care pathway in a primary care IAPT service. A framework was developed by the SIG with materials shared and iterated over a period of 3 months, prior to the initial pilot. Feedback was also sought from participants following each session on clarity, acceptability and face validity of the approach.

Approach

The transdiagnostic IU treatment approach assumes that at birth perceiving uncertainty as ‘unsafe’ confers an evolutionary advantage. Through learning and attachment infants learn to experience uncertainty as ‘safe’ and to engage with the world accordingly (Brosschot et al., Reference Brosschot, Verkuil and Thayer2018). Where this learning is disrupted, for example through attachment processes, life events or parenting (Beckwith, Reference Beckwith2016; McLean, Reference McLean2016; Wilkins, Reference Wilkins2016), individuals may struggle to distinguish ‘unsafe’ or threatening situations from ‘objectively-safe-but-unknown’ situations. Research on interventions targeting IU in an individual approach suggests that individuals who were high in IU are likely to take steps to reduce uncertainty in a range of life areas, not solely in relation to symptoms (Sankar, Reference Sankar2015; Tiplady et al., Reference Tiplady, Freeston and Meares2017).

To illustrate, in clinical practice an individual high in IU experiencing health anxiety symptoms might seek absolute certainty of ‘health’ by seeking a range of tests from their GP or reading information online. The same individual might also prefer to avoid uncertainty in everyday life by avoiding surprises, reading online reviews of restaurants or repeatedly follow the same driving routes. In the former example, the individual might be responding to the perceived threat of ill health; however, in the latter, reducing the discomfort of not-knowing is the main driver of behaviour. These uncertainty-reducing behaviours might take the form of ‘over-engagement’, i.e. over planning, preparation, trying to predict a range of possible outcomes or ‘under-engagement’, i.e. avoiding preparing for something or not turning up to an event to reduce uncertainty-related discomfort, or ‘impulsivity’, i.e. avoiding uncertainty and acting impulsively. Combinations of these behaviours are common in the management of uncertainty (Sankar et al., Reference Sankar, Robinson, Honey and Freeston2017).

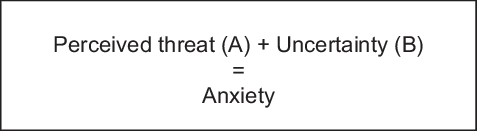

In anxiety disorders, where the majority of our understanding of IU has formed, we understand that for anxiety to be present, an individual must experience both (a) a perceived threat and (b) uncertainty (see Fig. 1). Where uncertainty is not present (e.g. where ‘threat’ is objective and definitive – ‘something bad is happening now’) the individual simply has a ‘certain’ threat, and therefore a problem to solve or escape from. When uncertainty is also present, problem solving can be impeded or ineffective, i.e. there are many possible courses of action, many possible outcomes, and even the presence or absence of the perceived threat is intangible, therefore anxiety is the response.

Traditional disorder-specific CBT aims to target the ‘threat’ component (A), through cognitive restructuring or weighing up the likelihood of the feared consequence, plus exposure to feared situations. Conversely, the MFWU group seeks to target the uncertainty component (B), to increase knowledge and awareness of the responses to uncertainty discomfort and to support individuals to build a new relationship with uncertainty, where safe uncertainty can be more accurately assessed and uncertainty discomfort can be tolerated, with a likely corresponding effect on symptoms. Previous research suggests that a reduction in IU can have a corresponding effect on symptoms of common difficulties (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Lomax and Freeston2019; p. 12).

An initial challenge in the development of this intervention is that if, as we theorise, relationships with uncertainty develop in infancy, that is pre-verbally and individuals high in IU may struggle to find a language around uncertainty or to even notice that uncertainty might be troubling to them. A key component of the approach is therefore in attuning participants to their own ‘uncertainty’ feeling, variously described as ‘the heebie-jeebies’ ‘the grumble of uncertainty’ or ‘moths rather than butterflies in the stomach’. Encouraging participants to experiment with uncertainty in areas of their life that do not relate to their specific concerns, but evoke objectively ‘safe’ uncertainty, is beneficial to activate these sensations. For example, we may ask participants to consider changing a routine or experiment with something new. Live examples of attuning to the ‘felt sense’ of uncertainty are also facilitated in the group (e.g. having people pick a random item from a bag and discuss it). In vivo activities were introduced in sessions, considered to represent non-threatening ways to ‘wake’ the sensations of uncertainty in participants. Examples of these in vivo activities included a game with a strong element of uncertainty (Pop-up-Pirate) and unusually flavoured or unlabelled foods brought to the group to provide informal and playful ways to experience uncertainty and begin to label and understand the bodily sensations associated with uncertainty.

While these tasks seem small, we observe that individuals who are intolerant of uncertainty find the activities provoking. As such, to create engagement and ‘buy-in’ we have developed the groups in a paced and scaled manner, structured to develop understanding in the following way. First, psychoeducation around uncertainty helps participants to explore how uncertainty affects us, the evolutionary underpinning of uncertainty, what does uncertainty ‘feel’ like, and telling the difference between ‘uncertain’ and ‘unsafe’. The concept of ‘low stakes’ and ‘high stakes’ was introduced to distinguish perceived threat from other factors which could add an element of value, such as cost or time (Tiplady et al., Reference Tiplady, Freeston and Meares2017). Second, participants were assisted to understand and experiment with ‘low stakes’ uncertainty. This process included making changes to behaviours which reduce uncertainty in ‘low stakes’ life areas and promote learning that the experience of uncertainty can be safe, (e.g. taking a new route to walk the dog). Third, attention was then turned to high stakes uncertainty experimentation, which encouraged participants to make changes to more resource-intensive uncertainty areas to increase ability to engage with ‘safe uncertainty’ (e.g. go on a day trip to somewhere totally new). Finally, we sought to help participants apply the learning to ‘threat-based’ scenarios by including psycho-education to support generalisation and opportunities to experiment with behaviours linked to the area of concern such as attending social events.

Method

Participants

Over a 10-month period the group ran three times. A total of 34 people accepted referral to the group, but ten participants did not attend. Of the remaining 24 participants, 20 participants completed treatment and four dropped out. More than half of the participants presented with symptoms of predominantly GAD, while the remaining participants presented with co-morbid difficulties including GAD, panic, OCD, specific phobia and depression.

Procedure

The MFWU group was established in Talking Helps Newcastle, an IAPT service in the North East of England. This service is designed to treat people with mild to moderate psychological difficulties with counselling, low and high intensity CBT interventions, psychology and primary care mental health worker interventions. The service experiences very high demand and little option to access extra resources, which has led to significant innovation and the development of group interventions to increase efficiency of throughput, while striving to deliver high quality psychological treatment. Measures were used as a part of standard care and participants opted-in for this course of treatment, so ethics approval was not needed. Approval for conducting a service evaluation was given by the hosting NHS trust research and audit service. Participants gave written consent for their data to be used.

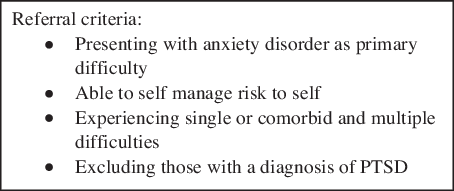

Participants were offered a routine telephone screening assessment. Screening identified the main presenting problem and associated risk assessment. Screeners were provided with referral criteria (see Fig. 2) and were invited to discuss potential referrals with the leading group therapists. Some participants may have stepped up to the waiting list for high intensity CBT following completion of a low intensity intervention.

Figure 1. The separation of threat and uncertainty in anxiety (Freeston, Reference Freeston2015).

Figure 2. Referral criteria for inclusion in the MFWU group.

All members of the group completed three questionnaires in the first and final group session, two of which are included in the recommended IAPT outcome measures (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2019).

Group programme

The first group ran for five consecutive sessions and each session was 90 minutes long. Following feedback from participants and reflection on the process by the group facilitators, the format was changed to six 2-hour sessions run over 8 weeks with the last two sessions occurring fortnightly. During the group sessions participants were offered the opportunity to have brief individual meetings with the facilitators in the breaks or at the end of the group. These meetings were used to review risk and to help consolidate the group content to individual circumstances.

Most participants joined the group ‘open-minded’, but having not identified uncertainty as a contributing factor to their difficulties, although some were openly sceptical. The facilitator approach was to encourage the individuals to ‘tolerate not knowing’ whether this approach was right for them, and framing this as an opportunity to practise the skills. Participants were advised that they could access additional intervention if required as per usual service protocol to counter ethical concerns. Additional intervention was sought by five participants within the service directly following the group.

Measures

Participants were asked to complete three measures during the group. The questionnaires measuring symptoms of depression and anxiety were completed every week and the IU measure was completed at the first and last group sessions.

Intolerance of uncertainty

The Intolerance of Uncertainty Short Scale (IUS-12; Carleton et al., Reference Carleton, Norton and Asmundson2007) is a derivative of the original 27-item Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS; Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur1994). Participants rate 12 statements about uncertainty on a 5-point Likert scale to assess emotional, cognitive and behavioural reactions to uncertain situations. Good internal consistency has been demonstrated (α = 0.85; Carleton et al., Reference Carleton, Norton and Asmundson2007). The total score was used rather than the prospective anxiety and inhibitory anxiety subscales (Carleton et al., Reference Carleton, Norton and Asmundson2007). Data collected by Carleton et al. (Reference Carleton, Norton and Asmundson2007) suggest a score of 35 as being the intersection between clinical and non-clinical samples, with people meeting the criteria for GAD, OCD, SAD, depression and panic disorder generally scoring higher than 35 on the IUS-12. Therefore a score of 35 or above has been used to demonstrate caseness in this study.

Depressive symptoms

Symptoms of depression were measured using the nine items of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001). The PHQ-9 is a depression module of self-administered diagnostic instruments for common mental disorders. The questionnaire has good psychometric properties and has been extensively used in other studies (Moriarty et al., Reference Moriarty, Gilbody, McMillan and Manea2015). Each item of the PHQ-9 is scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), resulting in the possible maximal score of 27. Scores of 5, 10, 15 and 20 are interpreted as mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe depression, respectively. Conforming to the previous suggestions, we use the cut-off point of ≥10 as the case of depression.

Anxiety symptoms

The seven items of the Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) was used to measure the anxiety-related problems. This scale has good psychometric properties in both primary care (Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Zamorano, García-Campayo, Pardo, Freire and Rejas2011) and general population (Löwe et al., Reference Löwe, Decker, Müller, Brähler, Schellberg, Herzog and Herzberg2008) settings. Each item of GAD-7 is scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), making a total score of 21. Score of 5, 10 and 15 are interpreted as mild, moderate and severe anxiety, respectively (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006). These categories are also used in IAPT to measure severity and here to interpret participant scores.

Qualitative data

Qualitative data were collected at the end of the group in the form of a brief questionnaire asking for participant comments on what had been most helpful, least helpful and what they would say to future participants of the group. A thematic analysis based on a structure described by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) was conducted and themes were agreed between the authors.

Results

Baseline severity

In terms of severity, one person scored in the severe range on both the GAD-7 and PHQ-9, ten people scored in the moderate to severe range on both the GAD-7 and PHQ-9, seven people scored in the moderate to severe range on either measure, and two people presented with mild scores on both measures. In summary, 18/20 participants demonstrated a clinically significant problem on either the PHQ-9 or the GAD-7. On the IUS-12, 17 out of 20 participants scored 30 or above. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 73 years old at the point of completing the group, and included 15 females and five males.

Symptom outcomes

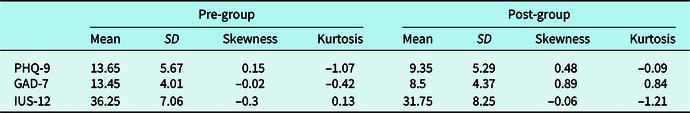

Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviation of scores on each of the measures used both pre- and post-intervention. Cronbach’s alpha was unable to be calculated.

Table 1. Mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis on outcome measures pre- and post-intervention

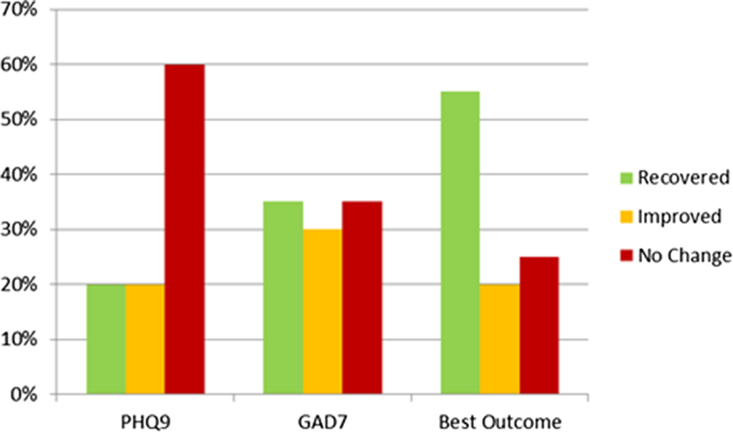

Figure 3 shows the percentage of participants who demonstrated clinically significant change (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) on measures of depression (PHQ-9) and generalised anxiety (GAD-7) from pre-group and post-group. Best outcome indicates the percentage of participants with clinically significant change in either depression or generalised anxiety. In summary, 85% of participants that were reporting a clinical problem on the IAPT measures prior to the group, and 75% showed reliable change on either the PHQ-9 or GAD-7. Furthermore, 55% showed recovery on one or the other.

Figure 3. Percentage of participants who showed clinically significant change on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7.

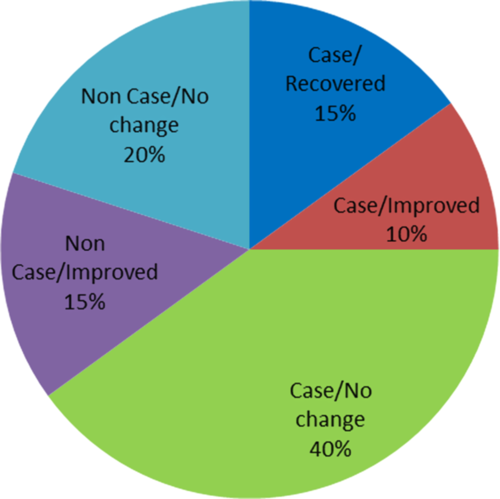

Figure 4 shows the percentage of participants who recovered, improved and showed no change based on scores of intolerance of uncertainty (IUS-12). Prior to the group, 65% of participants were experiencing IU at a level typically found in clinical samples using IUS-12 measure. Of the 20 participants who completed this measure pre- and post-treatment, 40% reported reliable change and 23.1% met the criteria for recovery.

Figure 4. Clinically significant change on the IUS-12.

Qualitative patient experiences

We identified three main themes: universality of the content; a sense of tolerance and acceptance of feelings; and how uncertainty affects group process particularly notable in the first session.

Universality of content

Participants commented that ‘everyone can relate to uncertainty in life’ and that ‘the acknowledgement of uncertainty in anxiety is very important’. In disorder-specific groups, it is sometimes difficult to manage co-morbidity and create real inclusivity when for some people their problem may not be entirely consistent or captured by the model presented. The benefit of the uncertainty group is that everyone can relate to it regardless of varying, mixed and co-morbid experiences of anxiety. In terms of group dynamics, a sense of universality can be achieved at an early stage in the course with great benefit (Yalom, Reference Yalom1995). Another participant commented that the most helpful part of the course ‘was to recognise what uncertainty is and how it connects to how I was feeling’. This feedback reflects the aim of having psychoeducation around uncertainty as the first focus of the group structure, as helping people to ‘tap in’ to the feeling of uncertainty will hopefully allow participants to share this with each other in the group, and recognise it outside of the room too.

Tolerance and acceptance

Participants commented that ‘I understand from the course that this will not immediately stop causing discomfort’ and ‘helped me realise that my problems could be tolerated’. This notion of ‘Making friends with Uncertainty’ rather than trying to eliminate it seemed to appeal to participants and thinking of the intervention as a work in progress rather than something with a finite ending helped to set people on a trajectory rather than become fixed on a specific end-point. People who remained symptomatic at the end of the course reported benefit and were satisfied with the treatment offered. One participant also commented ‘once I understood that I focused on uncertainty and tried to control it, it led me to understand that if I work on this it can help so that I don’t go down a spiral toward depression and anxiety’. Participants were encouraged to recognise the behaviours that they engage with in order to reduce or ‘control’ uncertainty. The comment from this participant reflects their understanding of working on the ‘control’ we can commonly aim for with uncertainty, which can often become unhelpful. By learning ways to tolerate uncertainty, participants will hopefully become more accepting of this feeling.

The uncertainty process manifesting in the group

Participants commented that ‘the first session was least helpful mainly because it was just an introduction and I felt too nervous to contribute’, ‘if you are uncertain about attending you are the ideal candidate to practise attending these sessions’ and ‘the least helpful session was the first when I was not sure what was going to happen’. These comments highlight how uncertainty about attendance at the group affects participants, how this uncertainty may inhibit learning in the first session and present a barrier to engaging with the group in the first place. However, this feeling can also helpfully activate some real uncertainty for the participants which we can reflect on in the group and offers a live opportunity to start explaining the model.

Discussion

Findings

The present evaluation reports on the implementation of a transdiagnostic group intervention targeting IU within an IAPT service. The data offer proof of concept and demonstrate that there may be significant clinical value in implementing a MFWU intervention, as 70% of participants demonstrated improvement in symptoms of depression or anxiety with 55% meeting criteria for recovery. Indeed, if such an intervention was further validated and scaled successfully, the group could also have benefits with respect to resource and cost efficiency.

Placing findings in the context of literature

While this intervention will require further evaluation, the focus on one process, that of IU alone, is novel and infers certain benefits. Talkovsky and Norton (Reference Talkovsky and Norton2016), found that IU decreased significantly following group treatment with transdiagnostic group CBT for anxiety (TGCBT). Furthermore, decreases in IU predicted improvements in clinical presentation across diagnoses of social anxiety disorder, panic disorder and generalised anxiety disorder. The TGCBT intervention consisted of 12 weekly 2-hour long sessions following a manualised protocol (Norton, Reference Norton2012) focusing on factors such as negative affectivity (NA), psychoeducation, self-monitoring of anxiety, stress and depression, cognitive restructuring of automatic thoughts, behavioural exposure and cognitive restructuring focused more broadly on underlying schemas or core beliefs. The MFWU group utilised in the current intervention demonstrated reliable change after only six sessions with a focus on one process, that of IU.

An additional benefit of the current intervention is the inclusion of participants with co-morbidity. Noyes (Reference Noyes2001) indicated that particularly with GAD, co-morbidity with other anxiety and mood disorders is the norm. In describing the origins of IAPT, Clark (Reference Clark2011) highlights how services were set up to treat specific disorders following NICE guidelines. As part of this initiative, therapists were trained in disorder-specific models and there is little mention of co-morbidity, making it less obvious for services and therapists to know how to parsimoniously and effectively treat people with co-morbid presentations. The ‘Making Friends with Uncertainty’ group offers a potential avenue for treatment of co-morbidity, which could be a welcome addition to some IAPT services framed around disorder-specific interventions and groups. The group presents an opportunity for services to incorporate more uncertainty into their structure and allow staff to work in a more creative and transdiagnostic way.

The ‘Making Friends with Uncertainty’ group was novel because it focused on a single transdiagnostic process for people with different and co-morbid anxiety disorders. Studies have shown that IU appears in ‘varying degrees from non-clinical to clinical populations … and is applicable to people in everyday life situations’ (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Lomax and Freeston2019; p. 8). Everyone, no matter their background or context, has experienced uncertainty at some point in their lives and many of us will have found it uncomfortable – perhaps waiting for the result of an exam or interview. As the transdiagnostic and universally experienced factor of uncertainty (as opposed to symptoms or ‘pathology’) sits at the core of the approach, facilitators found the group more conducive to sharing their own experiences of uncertainty. This contrasts with disorder-specific groups in which self-disclosure may feel less appropriate or applicable. Furthermore, in disorder-specific groups, some people with co-morbid presentations may find that aspects of their experience are not consistent with the group model. In contrast, the MFWU group is inclusive and allows for different responses to the same underlying process.

Strengths and limitations

This intervention has an emerging evidence base; however’ tolerating uncertainty is routinely only taught to those trained in high-intensity interventions. The facilitators observed that this limited socialisation to the uncertainty model could be a barrier for clinicians involved in screening in identifying individuals who may benefit from an IU-focused intervention. In the early stages of the group, limited socialisation was a barrier to recruitment. To combat this challenge, information was circulated service-wide and presented at local conferences. In addition, the researchers attended team meetings, facilitating case-discussion in order to both promote the profile of the intervention and increase socialisation to the model at a service level. Further, a psychological wellbeing practitioner with an existing special interest in uncertainty was recruited to more effectively embed the principles of the model into the screening team. The intervention appears to facilitate a sense of universality in the group in spite of different manifestations of uncertainty in different clinical presentations (Yalom, Reference Yalom1995). Supported by the universality of the uncertainty experiences, facilitators were able to move away from an ‘expert’ position. It was observed that participants began to scaffold their peers in developing an understanding of the approach (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1980), leading to greater group ownership and cohesion (Yalom, Reference Yalom1995). For example, on reporting back their experiences of uncertainty, group members would often highlight to each other different behavioural responses that had not been immediately obvious to the person recounting the story. Each of the groups facilitated have engaged in ‘outside group’ activities, including supporting each other with homework ideas and activities or starting social media groups. We theorise that the low stakes/low threat nature of the group was useful in destigmatising the group and encouraging group openness and cohesion at an earlier stage (Yalom, Reference Yalom1995).

The study of this group was small scale and as the group was in the development stages measures were only taken pre- and post-intervention. Work is underway to conduct more robust evaluation of the group using a single case design and including double baseline and follow-up measures. A limitation of the data in this study is that Cronbach’s alpha was unable to be calculated due to the nature in which the questionnaire scores were stored. The storage of this data as a total rather than as individual items precluded our calculation of this. As the group is a novel intervention it seemed prudent to reflect and evaluate its development prior to conducting more stringent evaluation. This also provided the opportunity to refine and improve the intervention and further develop the protocol.

A further limitation of this study was an unequal gender distribution, with five male participants compared with 15 females. In comparison, in the 2 years during which these groups ran, 62% of all referrals into the service and 60% of in-service referrals to group therapy were female. In addition to this, 69% of all referrals into a MFWU group in the service have been female. This would suggest that the gender split in this study is representative of the service users as a whole and is part of a sample too small to reflect on this intervention specifically. However, studies have suggested that women generally exhibit more favourable intentions to seek mental health support (Mackenzie et al., Reference Mackenzie, Gekoski and Knox2006) and potential barriers for men doing so may include gender ideology (Ellis, Reference Ellis2018) and difficulty recognising and communicating symptoms of mental health problems (Seidler et al., Reference Seidler, Dawes, Rice, Oliffe and Dhillon2016). It is possible that the distribution of gender observed in this study reflects this and supports further efforts to encourage more help-seeking behaviour in males.

Practitioner reflections

At a service level some clinicians expressed concern at ‘not knowing’ whether the intervention would ‘be right’ for the individual and the prospect of this ‘not knowing’ felt disconcerting. These concerns could be conceptualised as a parallel process to the experience of participants. It is interesting in this context to note that we seldom ‘guarantee’ the outcomes associated with the therapies that we offer, even when these are more established within the evidence base. This response was less prevalent as the group became more established within the service and the process and outcome of the group was more clearly understood. The perceived reduction in these concerns may suggest that increasing knowledge or ‘certainty’ in a helpful and proportionate way may help individuals to engage with novel or ‘uncertain’ situations.

The group facilitators both experienced and reflected on uncertainty following sessions. We actively formulated this experience using the group protocol. At times these experiences were shared in the group, and both facilitators felt that in order to connect with the group and truly learn the approach this self-practice self-reflection (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001; Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2003) was important. Such reflection facilitated competence building in terms of content delivery, interpersonal effectiveness in relating to the group participants, and a felt sense of attuning to uncertainty experiences (Bennett-Levy and Thwaites, Reference Bennett-Levy and Thwaites2007). We observed that learning trajectory in the groups delivered felt different from others that we have offered. By scaffolding individuals to explore and understand uncertainty in ‘low stakes’ areas of their lives, often unrelated to the presentation which led them to seek intervention, progress felt ‘slow’ initially. A more rapid pace of symptom reduction and behavioural change was then observed in the later sessions. The pace was contrary to our expectations of steady, initial or incremental gains.

Implications, future plans and future research

Delivering a group with a novel framework presented a number of challenges at a service and therapist level. The ability to be flexible and iterate the sessions, as well as to model the core message of the group by tolerating the uncertainty associated with a novel intervention (within a safe governance framework) was vital. Service level buy-in was also crucial. The majority of the participants who attended the sessions experienced outcomes comparable to other, more established high intensity CBT groups, and retention rates were high, with positive qualitative feedback. The group was feasible to develop and deliver in the context of a busy service, and although the initial therapists had grounding in the novel intervention, training has been delivered to extend the delivery team, increasing awareness of the model across the service.

The facilitators in this project had access to specialist training, supervision and consultancy, which helped to ensure fidelity to the uncertainty model. A potential barrier to roll out of this intervention in other services is that the model is not yet well established and a further training programme or protocol or training manual may be required to support implementation and replication.

There are many potential individual and service benefits to the implementation of the MFWU group. The MFWU group offers an opportunity for delivery of a focused and targeted intervention which is also transdiagnostic. The group offers a potential treatment avenue for those who may have previously not responded to traditional NICE-recommended CBT models for specific disorders, and who do not wish to attempt the same protocol again. For services, it is difficult for screening assessors to briefly and comprehensively assess multiple and inter-related disorders, and then precisely direct to a disorder-specific group. Finally, the MFWU group is less reliant on labelling of a specific disorder and so could be a very helpful adjunct to disorder-specific treatment.

In summary, the MFWU group appears to provide an acceptable and feasible option for individuals presenting to IAPT services with a broad range of difficulties including co-morbidities. Iteration and evaluation of the content and framework will continue in both group and individual formats and in a wider range of settings. Continued evaluation, development and increased access to training of this model could facilitate more therapists and services to offer an intervention like this. Learning from experience of the group so far will help us to improve our ability to articulate and understand the ‘uncertainty’ experience and to support individuals high in IU to develop a more helpful relationship with uncertainty.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Lauren Mawn for guidance and feedback, and the Newcastle Intolerance of Uncertainty Treatment Development Group, whose members include (in alphabetical order): Sally Askey-Jones, Alice Bentley, Mark Freeston, Lauren Mawn, Kevin Meares, Layla Mofrad, Danielle Payne, Richard Thwaites and Ashley Tiplady, for helping to develop clinical aspects of the group. We would also like to thank other practitioners who have facilitated the group: Dr Jade Ingram and Dr Mariam Majid. We are grateful to Dr Leahan Garratt as clinical lead of Talking Helps Newcastle for her support with this project.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

Mark Freeston has written books and receives royalties and provides training and receives honoraria on similar topics.

Ethical statement

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS (http://www.babcp.com/files/About/BABCP-Standards-of-Conduct-Performance-and-Ethics-0917.pdf). No ethical approval was needed: the group treatment was delivered within routine clinical practice and the participants consented for anonymised details of their therapy to be included.

Key practice points

-

(1) This evaluation suggests there may be clinical value in running a transdiagnostic treatment group focused on building tolerance to uncertainty in IAPT services, which usually offer disorder-specific treatments.

-

(2) The MWFU group demonstrates a potential avenue for treatment of co-morbidity in IAPT services.

-

(3) The universality of the experience of uncertainty in the group was valuable for both the practitioners and participants. Benefits of this included practitioners feeling more confident in content delivery and participants scaffolding each other’s learning despite varying clinical presentations.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.