Introduction

The Senior Wellbeing Practitioner (SWP) postgraduate certificate is the most recent of the Children and Young People’s Psychological Training (CYP-PT; previously CYP-IAPT) programmes, commissioned by NHS England Workforce, Training and Education, with the first courses commencing in January 2023. The training is intended to extend the skillset of qualified Child Wellbeing Practitioners (CWPs) and Educational Mental Health Practitioners (EMHPs), both of whom deliver low-intensity guided self-help for young people with mild to moderate mental health conditions in CAMHS, Mental Health Support Teams based in schools (MHSTs), and third sector organisations across the country.

The current workforce of CWPs and EMHPs is also relatively new, with these programmes having been first commissioned in 2017 and 2019, respectively. Data relating to the effectiveness of their low-intensity, manualised interventions is still emerging, but with encouraging results so far. In one of the few peer-reviewed studies, Turnbull et al. (Reference Turnbull, Kirk, Lincoln, Peacock and Howey2023) reported statistically significant improvements with moderate to large effect sizes following completion of interventions for depression and anxiety, delivered by CWPs across four services. These outcomes are reflective of a national audit of CWP outcomes (Fuggle and Hepburn, Reference Fuggle and Hepburn2019) which summarised data collected over a 2-year period (between 2017 and 2019) from over 50 services across the country. Improvements in symptoms and functioning on a range of outcome measures showed moderate to large effect sizes.

In comparison with CWPs and EMHPs, SWPs will deliver a broader range of brief, low-intensity cognitive behavioural interventions, in an effort to improve access to support for a wider range of young people and their families in both educational and community settings. Training therefore includes modules in enhanced practice for early intervention and adaptations to low-intensity interventions for neurodivergence (in addition to training in supervision which will not be discussed here). We were two of the first higher education institutions (HEIs) to be commissioned to run this new programme, having been involved in Children and Young People’s (CYP) psychological training since its infancy, beginning with the first trainings in high-intensity psychological therapies as part of the CAMHS Transformation Project in 2014, and as such are established providers of the full suite of CYP-PT programmes.

The SWP training programme was developed at pace, with the first cohorts of trainees starting their training just months after the course was commissioned. There is limited established agreement about the competencies required in low-intensity practitioners generally (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Egan., De Valle, Davey, Carlbring, Creswell and Wade2024), much less this new workforce of SWPs. Despite this, in order to support training, we needed a method of operationalising and assessing the skills and competencies required of these practitioners. In this paper we focus on the preliminary development of a new framework intended to outline the full range of competencies necessary to deliver effective, CBT-informed, low-intensity interventions, and outline how this new framework may be used to support training, supervision and reflective practice in this specific workforce.

The curriculum

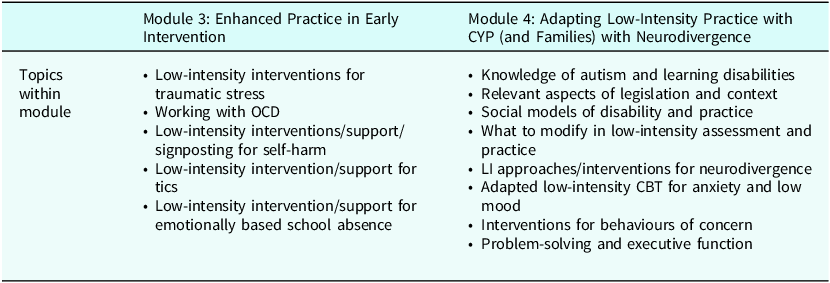

The SWP national curriculum consists of four modules: two modules focusing on supervision skills, which we will not be discussing here, and two modules focusing on enhanced low-intensity practice, the structure and content of which are shown in Table 1. The aim of the ‘Enhanced Practice in Early Intervention’ module (Module 3) is to expand the scope of conditions that low-intensity practitioners can work with, enabling them to deliver interventions to a broader range of young people and their families. Specifically, the module consists of training in low-intensity interventions for obsessive-compulsive disorder, tics, deliberate self-harm, emotionally based school absence, as well as training in trauma-informed practice. Trainees are expected to deliver at least four of these interventions over the course of their training.

Table 1. Structure and content of intervention modules within the SWP curriculum

The final module, ‘Adapting Low-Intensity Practice with CYP (and Families) with Neurodivergence’ (Module 4) provides trainees with an introduction to autism and learning disability, again in the context of low-intensity work. Trainees are taught how to recognise autism, ADHD and learning disabilities, and how to adapt their interventions to enhance accessibility for children and young people with diagnosed or suspected neurodevelopmental profiles. Trainees are expected to see at least three such cases over the course of their training.

Development of a framework to assess clinical competence

For the first year of this new training, we were keen to establish the clinical competencies required to effectively deliver the range of interventions covered by the SWP curriculum. We needed a way of operationalising and assessing the skills and techniques necessary to work with the range of presentations SWPs are required to treat, whilst retaining fidelity to the low-intensity intervention approach. Our model for training is to supplement formal teaching and workshops with reflective practice and supervision, with trainees bringing tapes of their clinical work to supervision sessions both in their service and at university. A preliminary competency framework was therefore developed to provide a structured approach to help SWPs reflect on their practice, and for trainers and supervisors to assess skill development and competence.

The CBT in Children and Young People Skills and Competency Framework (CBTCYP-SCF; Curry et al., Reference Curry, Fuggle and Dunsmuir2012) is already in use by staff and trainees on high-intensity therapy CYP-PT postgraduate diploma courses. Similarly, an adapted version (unpublished) is in use to support and assess skill development in low-intensity practitioners (CWPs and EMHPs) who are trained to deliver guided self-help with the use of low-intensity therapy manuals. For both high- and low-intensity practitioner training, the respective frameworks provide a method of operationalising the clinical skills being developed, and are used as a tool to assess competency as well as to encourage trainees’ self-reflection. The frameworks are referred to in tutor groups in which trainee practitioners share videos of their practice, but also used by markers to assess clinical competency in videos submitted for examination. The original framework was developed by a group of experienced CBT practitioners and trainers from the Anna Freud Centre at UCL (CBTCYP-SCF; Curry et al., Reference Curry, Fuggle and Dunsmuir2012) and further refined following rating of approximately 100 video recordings of CBT sessions with children and young people, as well as consultation with other experts in the field of CBT with children and young people. In contrast to the adult Revised Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTS-R; Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standard, Garland and Reichelt2001), the CBTCYP-SCF pays greater attention to core therapeutic skills necessary for working with children, such as their developmental level, the potential impact of the power imbalance on the therapeutic relationship and the need to incorporate the system around the child (such as family and school) into the CBT formulation and the way therapy is delivered. As such, the framework is consistent with the CAMHS competency framework (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Calder and Pilling2011) as well as the competency framework for CBT with adults (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007).

The CBTCYP-SCF was chosen as the basis for the developing a relevant competency framework for use specifically within the SWP training programme for several reasons. First, it already captures a range of generic competencies necessary for the delivery of effective low-intensity CBT-informed sessions. For example, ethical practice, working with power and difference, empathy, providing a rationale for the work, frequent summarising, joint session planning, session focus and time management, and setting between session tasks are all skills expected of SWPs and so these competencies were retained in the same format but with minor changes to the way the practitioners were referred. SWPs are not trained as cognitive behavioural therapists and so references to CBT were replaced with ‘practice’, and ‘CBT therapist’ was replaced with ‘practitioner’. ‘Treatment’ was replaced by ‘intervention’.

The second reason for adapting the CBTCYP-SCF was because SWPs are expected to deliver a number of disorder-specific interventions, many of which, at the time of writing, have no established low-intensity manuals. In contrast to CWPs and EMHPs, who follow a structured manual to deliver their sessions, SWPs will need to apply their therapeutic skills in a more formulation-driven way, tailored to the needs of their clients. Therefore, specific competencies are crucial to teach and assess, and many of these are already captured within the CBTCYP-SCF. We adapted these sections by removing explicit reference to CBT techniques in which SWPs will not necessarily have been trained, whilst retaining the descriptions of core therapeutic skills that would nevertheless be expected for effective practice. For example, the CBTCYP-SCF refers to the CBT therapist’s use of the Socratic approach. In the SWP-SCF, this was adjusted to emphasise the use of a collaborative style to facilitate engagement, without necessarily requiring a purely Socratic approach to do this. However, many of the examples of how this might be demonstrated in practice remained the same, including asking open-ended questions where developmentally appropriate, scaffolding questions for younger children to aid their thinking, and offering choices to facilitate active involvement in the session. In a similar vein, the examples listed for competency ‘Discovering Cognitions’ were adjusted to remove an example specific to high-intensity CBT practice, namely exploration of assumptions and beliefs using cognitive techniques such as the downward arrow. Instead, the SWP-SCF included an example of how an SWP might demonstrate this competency at a low’intensity level: ‘the practitioner considers the role of the young person’s cognitions in the formulation and considers when further work on thoughts/images is indicated’.

Whilst SWPs carry out many interventions directly with young people, their remit also includes therapeutic work with parents and carers, including for example psychoeducation around tics or neurodivergence, as well as working with schools and other agencies to support children and young people, for example in cases of emotionally based school absence, or young people who have experienced a trauma. Therefore we added references to the consideration of broader systemic factors, as well as adding in references to working with parents/carers in addition to children and young people. For example, to demonstrate the competency of ‘Developing a Shared Formulation’ we added the example: ‘The Practitioner incorporates systemic factors into the formulation where appropriate e.g. parent/carers/teachers’ thoughts, feelings and behaviours and how these link together to maintain child/young person’s current difficulties’. Similarly, to demonstrate the competency ‘Psychoeducation’, we added the example: ‘The Practitioner works with the system around the child/young person to convey the importance of psychoeducation e.g. tics, trauma informed work and neurodivergent conditions’. Furthermore, a competency specifically relating to working in groups was added.

A number of competencies were added to capture the skills necessary to work effectively with children and young people with neurodivergent presentations and learning disabilities, in line with Module 4 of the SWP curriculum. Rather than adding in a separate section outlining competencies specifically relating to this, examples of how the different elements of a session might be appropriately adapted were included throughout the competency framework to reflect the need to adjust practice at all stages of an intervention. For example, to demonstrate competence in being child/young person centred, thus contributing to the development of a strong therapeutic alliance, an SWP working with a neurodivergent child might show this competency by ‘using specific adaptations for neurodivergent child/young person that meets their specific needs, e.g. visual strategies; information presented in short discrete sections; clear and concrete language used’. Similarly, consideration of a client’s neurodevelopmental profile, and appropriate accommodation of neurodivergence and learning needs were specified as an examples of skilful practice for the following competencies: ‘Summarising’, ‘Joint Session Planning’, ‘Session Focus and Time Management’, ‘Between Session Tasks’, ‘Discovering Cognitions’, and ‘Developing a Shared Formulation’.

To capture the importance of adapting materials when working with neurodivergent presentations, we added the competency ‘Creativity’, defined as ‘The practitioner is creative in their therapeutic work demonstrated by using modified and individualised methods that enable the child/young person to access and understand the intervention model and facilitate active involvement. This is particularly relevant for those with neurodivergent presentations, e.g. drawing and using visuals; information presented in short discrete sections; movement/sensory breaks; concrete and clear language adapted to the young person’s learning difference and needs’. This also included some examples previously listed in the CBTCYP-SCF under ‘Being child/young person centred’ but which felt relevant to creativity (using drawing, role-play, puppets) and specified that this is one of the competencies which should always be demonstrated when working with a child or young person with neurodivergence.

The competency ‘Recognising Emotions’, which is part of the CBTCYP-SCF, is particularly relevant when working with neurodiversity and so the examples of skills relating to this competency were expanded to include helping children and young people recognise and identify triggers for specific emotions in addition to understanding intensity of emotion and developing vocabulary for this. We added a further example of how this might be demonstrated: ‘the practitioner flexibly considers and accommodates the cognitive skills and thinking styles of the CYP within a neurodiverse umbrella’.

Furthermore, we anticipate that SWPs should, where appropriate, be able to identify the need for environmental adaptations to support children and young people with neurodivergent presentations. We incorporated this under the competency ‘Specific Behavioural Change Techniques’, defined as using ‘appropriate behavioural methods to facilitate change, e.g. psychoeducation on the CYP’s differences, benefit of adjustments and adaptations to the environment; positive reinforcement, functional analysis, developing hierarchies, graded exposure, behavioural activation, contingency management’. Examples of how this might be demonstrated included ‘When working with carers and teachers this may also include review meetings to monitor the impact of adjustments and accommodations to address the CYP’s learning difference’.

Tutor experience of SWP Skills and Competency Framework

We have now had some experience of using the new SWP-SCF with the first cohorts of SWP trainees at our respective institutions. The competency framework has been used flexibly in practice tutor groups as a tool to support trainees’ skill development when reviewing session video clips relating to Module 3 (Enhanced Practice in Early Intervention) and Module 4 (Adapting Low-Intensity Practice with CYP and Families with Neurodivergence). Six practice tutors across both institutions have used the SWP-SCF with a total of 37 students from Cohort 1. Tutors have reported initial face validity with the framework which they viewed as useful to help students identify and rate competencies relevant to their work, with one tutor describing using it to support giving feedback, saying ‘it’s been helpful for me as a tutor to have this framework to identify competencies … specifically what they did well in a session and “even better ifs”’. Another tutor highlighted its role in ‘increasing student awareness of the key skills relevant to low intensity practice…[and] providing a tangible focus for development’.

The SWP-SCF has also been used for Module 3 and 4 assessments, and in this context utilises competency ratings for each skill outlined within the framework (‘not competent’, ‘partially competent’ or ‘competent’). As part of their formal assessment, SWPs are required to submit a recorded session during which they demonstrate a number of required competencies at a minimum of a ‘partially competent’ level, including specific skills aimed at facilitating therapeutic change (e.g. a cognitive or behavioural change technique such as exposure and response prevention), along with a written reflective account of that session, and a copy of a fully self-rated SWP-SCF. The SWP-SCF descriptors and competency ratings provided tutors with a useful framework to evaluate trainees’ clinical competency in these assignments and there was a good level of consistency between markers (evidenced by standard second marking processes and one tutor who marked assignments from both HEIs).

Feedback from the practice tutors resulted in some adjustments to the SWP-SCF for Cohort 2. These amendments included adding detail to the specific adaptations being made for neurodivergent client presentations (as outlined above) and clarity and consistency of language used.

Student feedback on use of SWP Skills and Competency Framework

We surveyed our SWP students for their views on the SWP-SCF. The small sample size and brief nature of the questionnaire responses meant that a formal qualitative analysis was not carried out. However, all respondents (n=15) indicated that they found the SWP-SCF a helpful tool to guide their clinical practice and to reflect on their own learning within the context of their assignments. For example one respondent stated that the SWP-SCF provided a ‘clear structure to follow with examples’ of each competency. All respondents had used the SWP-SCF very regularly (more often than not or almost always) in their skills practice sessions at university but only eight out of 15 reported using it regularly within their clinical supervision on site, with the remaining seven reporting that they had used it rarely or not at all. When asked what they found helpful about the framework, three students described finding it a useful aid for identifying their skills and areas of development, for example telling us: ‘reviewing it alongside videos in practice tutor groups [has been helpful]’. Similarly, six students described finding it a helpful way to understand and operationalise which skills were being taught and assessed, for example reporting: ‘It is good to see details of what we need to achieve in each section of the competencies’. Similarly, another student stated that ‘the bullet points to describe each competency [are the most helpful aspect] as it gives examples of what to look for’.

Students were asked about the comprehensiveness and relevance of the range of skills outlined in the framework. Three respondents reported that they found all skills described in the SWP-SCF relevant to their work (e.g. stating ‘I think they are all relevant’) and a further nine specifically highlighted Competency F: Facilitating Coping, Acceptance and Change (which includes cognitive and behavioural change skills) as being particularly relevant, for example reporting: ‘F competencies as these can vary so much for each individual case and often need careful consideration’.

Six respondents also highlighted Competency E: Facilitating Understanding, (consisting of skills in psychoeducation and formulation) as of particular relevance to their clinical work as SWPs, with one student stating: ‘E and F mainly, as the other competencies feel like things we have already learnt during [previous] training’.

None of the respondents identified any additional competencies that were missing from the framework. However, eight respondents reported that they found the framework very long, for example telling us: ‘It is very thorough [but] difficult to navigate [which] can be off-putting to use. It would be good to have a shorter summary version alongside it’. In response to this feedback, we have now added an additional summary sheet to the competency framework document.

Summary and conclusions

The SWP-SCF is a new tool designed to be used in teaching, supervision and in assignments to aid the development of skills required to be a clinically competent SWP. It is intended to help operationalise and assess the skills required to deliver effective low-intensity interventions for the range of presentations within the SWP remit. Whilst early feedback from tutors and students provisionally indicates good face validity and utility, a larger formal qualitative study into its utility with a range of stakeholders, including trainees, trainers and clinical supervisors, would be helpful in exploring this further. Similarly, further work is necessary to establish aspects of the framework’s reliability, including internal consistency, criterion validity, and inter-rater agreement.

It was noted that while students regularly used the SWP-SCF in university tutor sessions, only around half of our students reported using it in their clinical supervision on site, which perhaps reflects the fact that the framework is new to this workforce. As a result, we plan to run training sessions with clinical supervisors of SWP trainees to ensure that they are familiar with the SWP-SCF and as a way of encouraging them to use this tool within service-based clinical supervision.

Key practice points

-

(1) The SWP-SCF has the potential to be a useful framework for operationalising the skills necessary to deliver effective psychological interventions consistent with the demands of the SWP remit.

-

(2) The framework gives supervisors a tool for assessing clinical competence and skill development in trainee SWPs.

-

(3) The SWP-SCF also provides SWPs with a framework to guide their own reflective practice.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X25000133

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, CS, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Iris Varela and Stuart Lansdell for their contributions to the SWP-SCF framework.

Author contributions

Caroline Stokes: Project administration (equal), Resources (equal), Validation (equal), Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (lead); Siobhan Higgins: Resources (equal), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Carolyn Edwards: Resources (equal), Validation (equal), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Vicki Curry: Resources (equal), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Freena Tailor: Resources (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Susanna Payne: Resources (equal), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Jessica Richardson: Project administration (equal), Resources (equal), Writing - review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

All authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.