Introduction

Personal practice has long been advocated as an important part of psychotherapy training across theoretical orientations (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019; Orlinsky et al., Reference Orlinsky, Schofield, Schroder and Kazantzis2011). While not necessarily recommended as intensively as within other orientations, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has traditionally promoted the use of self-practice (Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Thwaites, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2019). This can be seen even in the early efforts of Ellis and Beck in developing their respective approaches to CBT. For instance, Ellis credits his use of behavioural challenges with helping him to overcome forms of social anxiety (Ellis, Reference Ellis1994b) and Beck noted that his self-analysis of automatic thoughts helped him to appreciate the relationship between such thoughts and emotions (Beck, Reference Beck2019). This resulted in recommendations that training therapists engage in self-practice to gain an experiential understanding of the cognitive behavioural model and its application to treatment (Beck, Reference Beck1995; Padesky, Reference Padesky1996). It is only since the turn of the century that there has been a concerted effort to develop a framework for implementing such experiential training, and efforts to empirically validate such training methods (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014).

Emerging out of this literature has been the self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR) framework (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015). It was initially developed to help trainees bridge the gap been declarative knowledge gained from didactic teaching to the development of skills and expertise with CBT theory and interventions (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001). To do this, the SP/SR model of training incorporates exercises focused on practice as a therapist, self-practice as a client, pair work in a client–therapist dyad, and an emphasis on self-reflection for the trainees about their experience in both client and therapist roles (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015). The interventions typically included in these programmes incorporate a range of cognitive interventions, workbook/journal exercises, and behavioural experiments (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001; Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Thwaites, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2019; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Cairns, Bennett-Levy, Johnston, Lowrie, Robinson and Perry2015).

The SP/SR framework has demonstrated positive outcomes in developing trainee cognitive behavioural therapists. It has shown benefits in helping trainees to develop a greater and more nuanced appreciation of cognitive behavioural theory, enhanced skill in the application of interventions, and improved confidence in providing therapy (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015; Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Thwaites, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2019; McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Yap, Bunch, Haarhoff, Perry and Bennett-Levy2021; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Davis, Chaddock, Whittington and Grey2014). It has also been shown to promote the development of interpersonal skills, with trainees reporting an improved ability in attuning to clients and enhanced empathy for their psychological difficulties (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015; Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Thwaites, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2019; McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Davis, Chaddock, Whittington and Grey2014). The benefits of SP/SR for trainee therapists have also been shown to assist with self-development more generally. For instance, improvements to self-awareness and the trainees’ own psychological wellbeing have been outcomes of engaging in SP/SR training (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001).

While often viewed as an interesting and engaging form of training, engagement in the process of SP/SR can be more challenging than more declarative training methods. This is important to be mindful of when developing such programmes, as the trainee’s level of engagement with the process directly impacts on the benefits attained from such training (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014). Anxiety has been found to impact on such engagement, with worries about negative judgement by others and worries about losing control during the experience negatively influencing engagement (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014; Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016). Factors that enhance positivity and motivation towards the model of training include expectations of benefit from the experiences, structure, positive group dynamics, links to course outcomes, and a positive perception of general coping resources at the time (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014). Factors that provide a sense of control over the experience can also mitigate related anxiety, with self-selection, control over the content of exercises, and control over the level of sharing about experiences promoting a greater willingness to engage in SP/SR training (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014).

SP/SR may also provide a useful method for introducing competency-based assessment for trainees, that is a way to measure competency in a vocational skill. With psychological practice involving competencies in assessment, evidence-based treatment planning, the application of interventions, and evaluation of treatment outcome (von Treuer and Reynolds, Reference von Treuer and Reynolds2017), it has been suggested that the SP/SR frameworks can provide an avenue for the early assessment of such skills in trainees (Collard and Clarke, Reference Collard and Clarke2020). The SP/SR provides trainees with a chance to practise and develop these skills on themselves prior to engaging in client work, and provides opportunity for external feedback to help with the development of such skills. This may be an important element that contributes to, or enhances, the development of self-reflective practice, which has been described as a metacompetence that allows therapists to learn from their experiences and to further develop their clinical skills (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock and Davis2009).

Consideration of the specific learning and skills taken from the discrete exercises in SP/SR programmes has been limited to date, with most SP/SR studies evaluating the benefits of entire programmes. Two exceptions to this include a paper by Bennett-Levy (Reference Bennett-Levy2003) contrasting the benefits of SP/SR for automatic thought records and behavioural experiments and a study by Collard and Clark (Reference Collard and Clarke2020) investigating the learning taken from trainees’ engagement in an exposure intervention for social anxiety. While these studies helped to demonstrate the different types of learning that can be taken from thought records and behavioural experiments (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2003) and the potential for improving trainees’ appreciation for, understanding of, and application of exposure strategies for social anxiety (Collard and Clarke, Reference Collard and Clarke2020), there is still great scope for examining the potential learning trainees could take from other SP/SR exercises.

An important clinical issue that would be important to target with such training methods is frustration intolerance (Harrington, Reference Harrington2005c). This concept can be further broken down into components of discomfort intolerance, emotional intolerance, entitlement, and achievement perfectionism (Harrington, Reference Harrington2011). Frustration intolerance has been related to emotional difficulties with depression, anxiety and anger (Harrington, Reference Harrington2005a). Behaviourally, it has been associated with issues such as aggression, procrastination, avoidance, substance use and self-harm (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Dixon-Gordon and Walters2011; Harrington, Reference Harrington2005b; Harrington, Reference Harrington2006; Leyro et al., Reference Leyro, Zvolensky and Bernstein2010). It has also been linked to the ability to pursue valued goals, intelligence quotients, socio-demographics, self-control and resilience (Meindl et al., Reference Meindl, Yu, Galla, Quirk, Haeck, Goyer and Duckworth2019), including the ability to cope with chronic pain (Suso-Ribera et al., Reference Suso-Ribera, Jornet-Gibert, Ribera Canudas, McCracken, Maydeu-Olivares and Gallardo-Pujol2016). Unsurprisingly, distress and frustration tolerance issues and exercises have become common aspects of treatment programmes for substance use issues, anxiety-related difficulties, and complex disorders such as borderline personality disorder (Clark, Reference Clark2013; Fassbinder et al., Reference Fassbinder, Schweiger, Martius, Wilde and Arntz2016; Leyro et al., Reference Leyro, Zvolensky and Bernstein2010; McHugh et al., Reference McHugh, Hearon and Otto2010). Therapist capacity for distress tolerance has also been suggested to be a factor in the skilled delivery of support to suicidal clients, the processing of trauma, and the application of exposure interventions (Waltman et al., Reference Waltman, Frankel and Williston2016; Waltz et al., Reference Waltz, Fruzzetti and Linehan1998), while from the SP/SR literature it has been observed that frustration tolerance can help therapists to manage unhelpful expectations of clients (Haarhoff et al., Reference Haarhoff, Gibson and Flett2011).

Study aims

This project aimed to review the use of the SP/SR framework in facilitating competency-based assessment. It also sought to apply the SP/SR framework to assess the usefulness of a behavioural experiment [i.e. a low frustration tolerance (LFT) exercise] in teaching trainees cognitive behavioural therapy. The training included a focus on the benefits of engaging in such exercises to promote the understanding and appreciation of cognitive behavioural principles; their application to practice; and common difficulties with psychological and behavioural change. It also aimed to assess how use of such exercises in therapist training may facilitate personal development.

Method

Participants

Participants for the study were drawn from a postgraduate clinical psychology programme. They were in their first year of the course and enrolled in a semester-long CBT unit. Participants had been enrolled in the unit in either 2018 or 2019. In total, 41 (34 female, 7 male) student trainees (out of a possible 47) participated in the study. Their ages ranged from 23 years to 35 years old.

Course requirements

The CBT unit had been developed with a number of experiential exercises to help promote trainees’ understanding of cognitive behavioural theories and principles. Such teaching strategies were developed in line with principles suggested for implementing SP/SR-based training (Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2019). The three key experiential exercises included were a LFT exercise (behavioural experiment), a shame attack exercise (a social anxiety exposure task), and real plays (i.e. where training therapists take turns ‘playing’ a client and a therapist using a real issue from their own life, instead of using constructed issues or pretending to be someone else; Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers, 2014). The LFT exercise, shame attack, and written reflections on these formed part of the assessment requirements for the unit. The LFT exercise was chosen as a behavioural task to provide trainees with insights into frustration/discomfort intolerance due to its suggested contribution to common interpersonal difficulties, self-control issues, and avoidant coping behaviours (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Dixon-Gordon and Walters2011; Harrington, Reference Harrington2005a; Leyro et al., Reference Leyro, Zvolensky and Bernstein2010). Theory explaining the basis of LFT exercises and examples of these were provided within classes. Based on SP/SR guidelines, the students developed their own LFT exercise to provide a sense of control over the task (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014), and to address a personalised aspect of frustration/discomfort intolerance. When providing the written reflection component of the task, participants were instructed to present a summary ‘demonstrating a formulation of the issue being addressed (i.e. ABC cognitive-behavioural model), your expectations about the experiences, any strategies employed to cope with the task and what you learnt from the exercises’. The learning reflection was further emphasised in the second cohort, with further verbal direction to comment on learning from both a professional and personal perspective in the written reflections. Individual guidance and clarification on the task were also offered for those seeking extra support. There was also verbal clarification of the task requirements given in class and a marking rubric was provided. This highlighted that the written component of the assignment would be assessed on the appropriateness of the behavioural task that was devised, the detail and depth of the formulation presented, and based on the description of the expectations, observations, and learning taken from undertaking the exercise.

Procedure

Research was approved by the Cairnmillar Institute Human Research Ethics Committee. Once students had completed the course, and marks had been released, students enrolled in the courses were asked to voluntarily participate in the study by providing consent for their written reflections of the LFT exercise to be included as data for the study. The retrospective collection of data was used to reduce any potential for coercion or dual relationships between the researchers and the participants.

Data analysis

A mixed methods approach was taken to analyse the data. As part of the evaluation of the exercise as a form of competency-based assessment, simple quantitative analysis was used to assess the frequency with which key skills were demonstrated or discussed (i.e. ability to develop an LFT exercise, formulation skills) in the participants’ written reflections. The frequency with which key themes were noted by participants are also noted. Examples of the qualitative data are then presented to illustrate the reported themes. For the qualitative analysis, a thematic analysis was conducted using a hybrid inductive-deductive model in line with recommendations by Fereday and Muir-Cochrane (Reference Fereday and Muir-Cochrane2006) and Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006). For more information on this model, refer to Collard and Clarke (Reference Collard and Clarke2020). With regard to the LFT exercise, previous literature on frustration intolerance (e.g. Harrington, 2005; Harrington, Reference Harrington2007; Meindl et al., Reference Meindl, Yu, Galla, Quirk, Haeck, Goyer and Duckworth2019; Rodman et al., Reference Rodman, Daughters and Lejuez2009) was incorporated into the model.

Results

Activities undertaken

All the exercises developed by the students were appropriate behavioural challenges for frustration and discomfort tolerance. The behavioural challenges developed were grouped into four themes. Eighteen (43.9%) engaged in travel-related activities, tending to focus on impatience (e.g. consistently driving below the speed limit, tolerating others’ driving behaviour, walking behind ‘slow’ walkers). Ten (24.4%) worked on tolerance for others’ behaviour (e.g. others leaving clothes or dishes around the house, how others expressed themselves). Ten (24.4%) worked on changing their own behavioural habits (e.g. not biting/pulling nails, not washing hair, setting time to relax, not checking phone/social media, using opposite hand for a task) and three (7.3%) worked on tolerance of sensory stimuli that caused them discomfort (e.g. smells, sounds/misophonia). The duration of the exercises set by the students for themselves ranged from a single event up to prolonged efforts at changing habits, with the longest being for 1 month.

Formulations

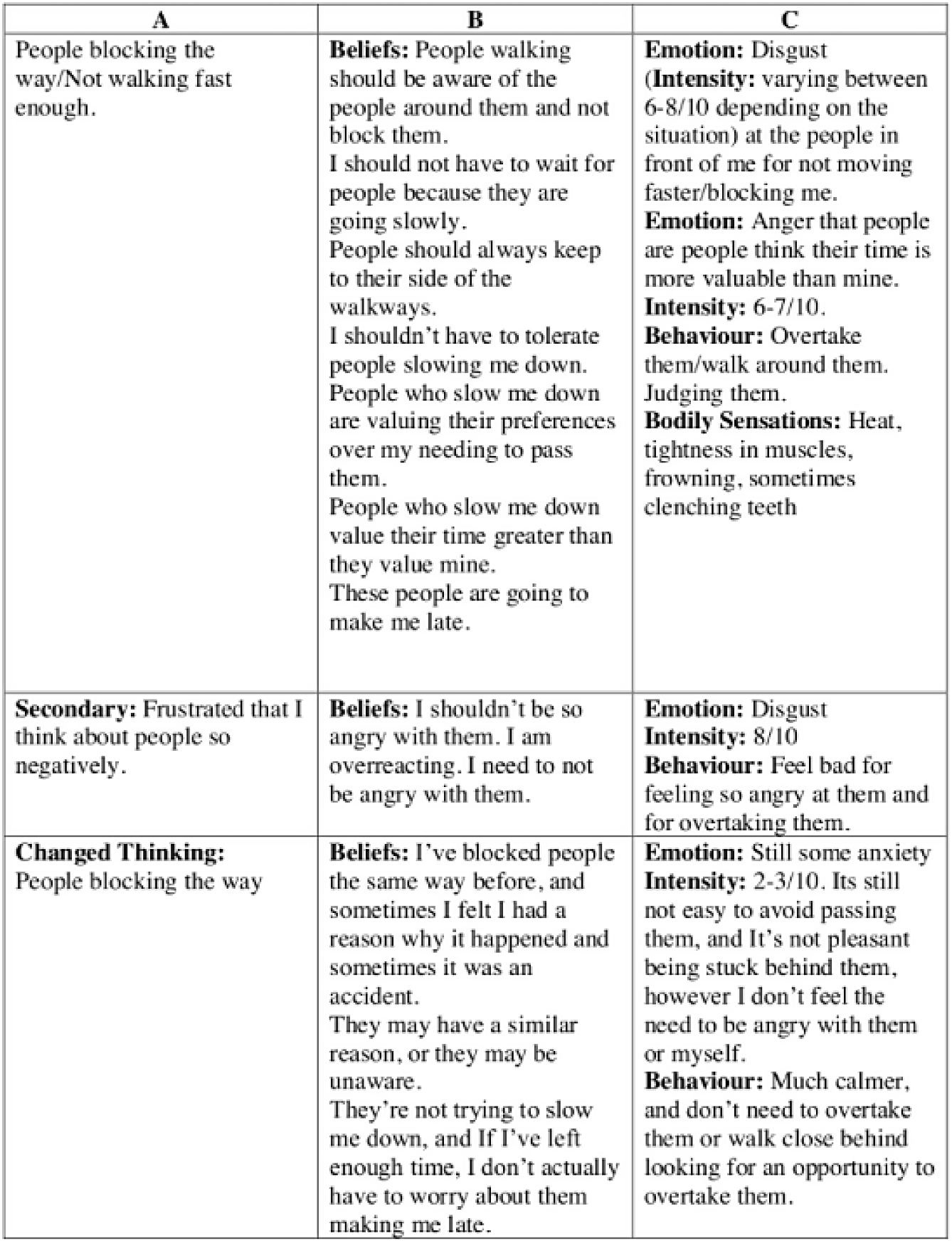

The formulations were reviewed from a competency-based perspective. This assessed the congruence of the formulation across cognitive, emotional, physiological and behavioural domains. They were also assessed in relation to the different levels of cognitive processing identified (i.e. automatic thoughts/inferences, conditional assumptions/demands, core beliefs/evaluations). In terms of the SP/SR, the formulations and the related reflections were analysed in terms of how they promoted a deepened appreciation of the cognitive behavioural model. An example of the formulations presented by the students is provided in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Example of participant formulation

Thought, feeling, behaviour interactions

In presenting their formulations of the LFT exercises, 41 participants (100%) presented congruent formulations of their emotional reactions to their chosen tasks. In their reflections, participants typically reported that with the behavioural challenges they experienced anger and/or anxiety. All the reflections also included notes on actively observing the relationship between cognitions, emotions, physical symptoms, and behavioural urges during the exercise. This was observed in the following quotes:

-

‘On the second day of this exercise, I realised the impact my awfulizing thoughts were having on my feelings of anger.’

-

‘I found the first day to be the most difficult because the more I focused on my anxious thoughts the worse they became (in context of misophonia).’

-

‘On the first day when I entered into the traffic, I began to have several unhelpful thoughts such as, “it is going to take a long time to arrive home”. As I continued the drive and the traffic was building, I began to get angry, particularly when the cars were moving very slowly, and the traffic lights were appearing to change frequently. I experienced a great deal of heavy breathing and became overheated when I began to feel angry.’

-

‘I was angry during the LFT due to my beliefs that I should not need to be this stressed about driving. My beliefs during the LFT centred around my demand on others that “people should just drive better”. This anger was then followed by a later emotion of guilt, for my level of anger towards others.’

Depth of cognitive formulation

In analysing the formulations for the LFT exercises, the models presented by the participants were assessed in terms of the three levels of cognitive processing commonly identified in emotional reactions. These were either identified in the moment or suggested as relevant hypotheses afterwards. The possible combinations of cognition types and the number of participants that identified these is demonstrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Number of participants and their identified cognitive profiles

Observed secondary responses

In presenting the formulations of their reactions to the LFT exercises, ten (24.4%) identified a primary and a secondary response. For some, they became aware of the underlying primary response while undertaking the exercise (e.g. becoming aware that anger at other drivers was a reaction to anxiety about running late) or identified a problematic secondary reaction to their initial reaction (e.g. shame or guilt, with self-deprecating thoughts in response to feeling anger at someone else or not better controlling their behaviour).

Coping strategies

While engaging in the LFT exercises, 29 (70.7%) of the participants applied one or more coping strategies to help get through the experience. The types of coping strategies and reported effects are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Coping strategies used with LFT exercise

Observations on efforts to make change

When reflecting on the LFT exercise, participants provided a range of observations on their experiences. These included comments showing an appreciation and understanding of the maintaining cycles of their cognitions, emotions and behaviours. They also commented on the process of change

Observations on maintaining cycles of dysfunction

In the observations on the maintaining cycles of dysfunction, 14 (34.1%) commented on difficulties they had in managing thoughts, emotions and behaviours. Examples of these comments included:

-

‘I immediately noticed how easy it was to simply revert to old habits. It was genuinely difficult to stick to such a simple commitment – far more difficult than I had originally anticipated. I found myself rationalising why I needed to drive at the speed limit, with thoughts such as, “It would be better to beat the traffic”, or “Everyone else is driving faster than me”.’

-

‘Prior to doing the exercise I planned to utilise breathing strategies to calm me down when I began to feel angry. However, while I was stuck in traffic, I completely disregarded this, and my irrational thoughts took over.’

-

‘I was surprised with how anxious and restless it made me feel. When I felt anxious or frustrated, I had to leave the house or focus on something else that would take my mind off it (e.g. study, watch a movie, call a friend). I was also hostile or passive aggressive to my house mates, which I did not like.’ [not cleaning up after house mate]

-

[in response to sleeping without a fan on] ‘For the first two nights it did take a while to fall asleep. I was tossing and turning a lot and ruminating about the consequences of not getting much sleep.’

-

[reducing time spent on phone] ‘At first, I found it very difficult and my mind would wander to whether I should check my phone in case someone had contacted me.’

There were also seven (17.1%) participants who commented on how their emotional states related to the focus of their attention. Some of these are referenced in the above quotes. Further comments on attention included:

-

[in response to working on tolerance for partner leaving glasses around the house] During the exercise, I did notice the glasses and I was tempted to put them away or to say something to my partner. I found myself noticing the glasses frequently.

-

[working on nail biting] On day of success, ‘there might have also been less attention to these experiences, as she was absorbed in other tasks.’

In discussing their experiences during their given task, five (12.2%) highlighted the role of dysfunctional coping strategies in maintaining their issue. This was reflected in comments that:

-

[working on reducing nail biting] ‘Replacement behaviours occurred more often during experiences of anxiety, compared with frustration. This might have indicated that there was a lower tolerance for the physiological discomfort associated with anxiety. Nail-biting might have taken on more of a habitual, unconscious quality during anxiety (e.g. becoming aware, first, of the behaviour), compared with frustration (e.g. becoming aware, first, of the urge to nail-bite). Avoidance (e.g. TV watching) also occurred during times of frustration with study. This reinforced demands that studying should not be frustrating, and that assignments had to be done well, or not at all.’

-

‘Although I knew that avoiding the task in the beginning was not ideal, it served to manage the frustration that I was feeling.’

-

‘At times, I went against the exercise and had to clean to reduce my anxiety and receive that immediate satisfaction’ [not cleaning up after house mate]

Three participants (7.3%) also explicitly commented on how their initial reactions contributed to problematic secondary reactions. This is demonstrated in the following quotes:

-

‘What I learnt from this is that when I’m angry and frustrated, I like to overly express it to the point that it becomes comical, I think it helps me from progressing my emotions into actual, uncontrollable anger. I also think that there is an element of laughing at my pain to make it okay. However, I do know that if I try to laugh off my frustration and pain, then I’m invalidating my emotions and almost stigmatising anger. But I guess my fear is that if I become angry, then I won’t have control and might do something reckless.’

-

[using cutlery with opposite hands] ‘The avoidance strategy where I ate foods that did not require the use of cutlery made me feel at ease for a short amount of time (i.e. when I initially started eating and was feeling my hunger was satisfied), however, after some time, I began to feel guilty that I was “cheating”, and not engaging in the LFT task that I set out for myself.’

Observations on the change process

Nineteen (46.3%) of the participants commented on how they observed their reaction to their chosen behavioural challenge change during the exercise. For instance, these included statements that:

-

[in response to working on tolerance for partner leaving glasses around the house] ‘Although I was initially frustrated, my reaction did begin to change. After about day 3, I noticed that I was no longer having the same irritated reaction and my thoughts were related more to me noticing the glass and thinking about the experiment.’

-

[in response not sleeping without a fan on] ‘After the first two nights this anxiety response quietened down a little, as I had proved to myself that I still could get a bit of sleep, and could make it through the day regardless. This helped me sleep better, and by the last night I don’t think I experienced an anxiety response at all and had a great night sleep without the fan.’

-

[working on misophonia] ‘As the week went on, I was able to proactively think of more helpful thoughts until the chewing became a non-issue.’

-

‘While I still felt frustration with slow drivers, I did notice that this frustration became less intense toward the end of the week and that I was able to just sit with the frustration rather than acting on it.’

-

[reducing fidgeting] ‘After the first week, I found it easier to stop the fidgeting. I was also able to catch the fidgeting sooner. The task would become less stressful to carry out and would require less time to become aware of it in the first place.’

There were four (9.8%) participants who made observations on the level of effort required to persist with their attempts at change. They made comments that:

-

‘During the car trips on the third and fourth day I focused on replacing my negative thoughts of “I will get home so late”, to more positive thoughts such as “there is no rush to get home, I will get there eventually”. Initially, I found this extremely challenging to maintain.’

-

‘In order for me to manage until the end of the week without washing my hair, I found that I had to challenge my negative thoughts to, “I will be able to get through this week” and “I don’t look awful with oily hair” and found that I was more calm and did not need to focus my attention on my hair.’

Three (7.3%) participants included comments on how their behavioural goals for the exercise helped them to persist through their distress and achieve their goal. For instance, they stated that:

-

‘I also noticed the power of committing to a goal, and the level to which this influences your ability to endure uncomfortable experiences.’

-

‘The task certainly caused me a lot of frustration and at times feelings of anxiety where I just wanted to give up, but I am proud of myself in succeeding.’

Two (4.8%) of the participants, who engaged in activities to work on tolerating behaviours of other family members, identified that by changing their own behaviour there was a positive impact on the others’ behaviour as well. This was reflected in comments that:

-

[working on tolerance for children leaving toys out] ‘On the fourth and fifth day, I noticed that I was more calm and able to negotiate with the children to help me put the toys away at the end of the day. Surprisingly, this worked well, as I noticed that the children were motivated to do this, partly because they saw the benefit of not losing the toys but also due to my calm demeanour.’

Key learning

In reflecting on their experiences engaging in the LFT exercise, all of the participants reported key learnings about themselves and their understanding of cognitive behavioural principles. These included themes relating to cognitive, emotional and behavioural change, increased self-awareness, and improved interpersonal interactions. Some of these comments also indicated awareness of the interactions between these factors (specific quotes will only be reported under one relevant heading). Two (4.9%) of the participants did note they struggled to make effective change in the time they had set themselves for the task, but did note increased self-awareness and an appreciation of the importance of persistence with working on such change.

Cognitive change

With regard to cognitive changes, 28 (68.3%) explicitly reported that engaging in the LFT exercise provided learning that promoted a cognitive shift. This was demonstrated in the following comments.

-

‘By changing my beliefs, I then understood that my previous beliefs had allowed my frustration to escalate and that my perception of the event made it much worse than it needed to be.’

-

[in relation to misophonia] ‘I do feel that doing this activity allowed me to dispute one of the main beliefs I had being “I can’t stand that noise”. It turns out I can tolerate it!’

-

[not washing hair for a week] ‘I learnt through this exercise that once I was able to change my negative self-appraisals and enact positive coping strategies that I was able to manage successfully through the week with this particular exercise.’

-

[not tidying up after house mates] ‘Upon reflection, the beliefs that I had at the time of the exercise seem petty and silly and made me realise that I should not waste my energy ruminating over something that is so meaningless.’

-

[working on sleep habits] ‘This demonstrated to me that sleeping with the fan on is more of a preference – it’s not a requirement or a need.’

In a more general manner, seven (17.1%) of the participants reported that from engaging in the exercise they developed an enhanced belief in the capacity for psychological change, typically in relation to themselves. For example, participants stated that:

-

[coping with busy traffic] ‘I was pleasantly surprised by my ability to calm myself down throughout the development and exacerbation of associated negative symptoms.’

-

‘I learnt from the low frustration task that tolerance can certainly be built when it comes to making positive changes in behaviour.’

-

[reducing fidgeting] ‘Outside of the task itself, completing the LFT task made me better able to cope with other potentially frustrating activities. For example, when voting, there was a line and where I would usually have been frustrated by the circumstance, I was better able to deal with it. I was aware of the thought process in my head that would get me frustrated and was able to deal with them.’

Three (7.3%) participants also noted that from engaging in the behavioural exercise, they achieved a sense of liberation and/or achievement that positively enhanced their self-concept.

-

‘I actually found it liberating as I didn’t waste time washing and styling my hair.’

-

[nail biting] ‘I completed this exercise successfully and following the seventh day my initial thought was that I finally achieved some self-control.’

Emotional change

In terms of emotional change, 25 (61.0%) focused on how the exercise promoted positive emotional changes. For instance, it was stated that:

-

‘This has demonstrated to me the benefit of engaging in an LFT exercise and the importance of altering irrational thoughts to elicit a long-term and consistent change in feelings of anger and frustration.’

-

[tolerating mother’s opinions] ‘By recognising that it is okay for her to not agree with me all the time, this significantly reduced the amount of frustration or agitation I would usually feel.’

-

[not cleaning up after housemate] ‘A week was not enough time for me to learn this new behaviour but it is something that I continue to work towards, however, I know that I am not as frustrated as I was when I started.’

-

‘More helpful thoughts … ultimately allowed me to be significantly calmer on my drives.’

-

[tolerating sensitivity to smells] ‘I did not allow myself to have a panic attack as I kept disputing the unhelpful belief that I smelt. Although this was a challenge, we were still able to have a nice day in the city.’

Self-awareness

Seventeen (41.5%) of the participants reported that the experience increased their level of self-awareness and emotional responsibility. Such increased insight into their functioning was demonstrated in comments that:

-

‘I then understood that my previous beliefs had allowed my frustration to escalate and that my perception of the event made it much worse than it needed to be.’

-

[tolerance for husband sneezing] ‘Identifying these thoughts made me realise how irrational these were, which made me feel quite guilty (secondary emotion) for being angry at my husband. What I found very interesting is that up until that time, I had never thought that I was getting angry at him, I just thought I was getting annoyed by him.’

-

‘Although I always knew I valued being timely, I didn’t realise just how much of an impact it could have on me if I risked being late anywhere. I had always attributed my feelings of anxiety in slow traffic to other drivers being slow, however, this exercise has helped me to identify that the fear of being late is the main thought that induces anxiety within me.’

-

[working on learning to relax] ‘I realise I do not allow myself the chance to relax as I tend to associate relaxing with being lazy and unproductive, and I associate being lazy and unproductive with a failure to reach my career goals.’

-

‘I have realised I’m quite rigid when it comes to the way I like things set out and struggle to compromise when it comes to cleanliness.’

Behavioural change

While a number of the LFT exercises may not have involved a specific focus on longer term behaviour change, or such change may have been secondary to cognitive and emotional changes, 12 (29.3%) of the participants commented on a significant shift in their behavioural patterns from the exercise. Statements reflecting such changes were:

-

[tolerance for others walking slowly] ‘I also learnt that slowing down isn’t so bad, at least I won’t barrel into any more tables.’

-

[reducing time on phone] ‘I was then actually able to put more time aside for my friends/family without worrying about studying because I had spent more time prior focused on university work.’

-

[tolerating sensitivity to smells] ‘Instead of leaving we decided to sit inside. The kitchen was close by and there was poor ventilation. This was very challenging for me. In the past we would not have stayed. However, this time was different as I had insight, I knew the anxiety I felt was a product of what I was thinking about being inside the cafe.’

-

[driving below the speed limit] ‘I started to leave earlier and played podcasts to make my drive more enjoyable, and found I was more relaxed upon arriving at my destination.’

Interpersonal relationships

From the exercise, six (14.6%) of the participants reported that by working on tolerance for others it had improved their social interactions, often also increasing empathy for others. This is reflected in the following quotes:

-

[tolerating children not tidying their toys] ‘This helped me to cope with the frustration but ultimately also had a positive effect on the children’s behaviour.’

-

[tolerating mother’s opinions] ‘I learned that it is possible to have a discussion with my mother without getting so easily frustrated.’

-

[driving under the speed limit] ‘This made me reflect on my own thought towards slow drivers and made me realise that it’s not a big deal if someone drives very slowly, and that you don’t need to get frustrated with these drivers. By completing this task, I learnt to be more tolerant of slow drivers on the road.’

Thinking of their future clinical work, three (7.3%) reported that the exercise enhanced their empathy for potential clients. They stated:

-

‘I realised how hard it might be for someone with OCD to manage their compulsions, or people struggling with addiction to break a habit.’

-

‘It also gave me insight into the difficulties and barriers a client might face when starting the CBT model for treatment.’

-

[nail biting] ‘I also understood that many other people may lack self-control sometimes and it does not make them any less worthy.’

Discussion

This study examined the use of a LFT exercise to help educate trainee psychologists in cognitive behavioural theory and practice. The use of this exercise as a behavioural challenge, with reflective journalling, also allowed for a level of competency-based assessment with regard to the trainee’s abilities to assess, formulate, design and conduct interventions, and to evaluate their outcomes. The trainees reported a number of key learning processes from the experience that were consistent with principles relevant to frustration/distress tolerance. In line with the SP/SR literature, this training strategy helped to deepen the trainees’ appreciation of the interplay between cognitions, emotions and behaviours. It also enhanced their appreciation for the challenges and effort required to change habitual patterns, particularly those that have involved negative reinforcement processes (i.e. avoidance and venting). Learning taken from the experience also had implications for the development of interpersonal skills, helping to enhance empathy and tolerance for other individuals.

SP/SR as a form of competency-based assessment

The provision of training within a SP/SR framework has typically demonstrated an increased perception by trainees in their ability to apply CBT techniques, but there has generally not been a focus on independent assessment of such competence (McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015; Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016). The framework does, however, appear to provide a method for assessing competency. As suggested in our previous paper (Collard and Clarke, Reference Collard and Clarke2020), the inclusion of behavioural interventions with reflective journalling within such training provides a basis for assessing competence in formulation skills, intervention design and application, and analysis of outcomes. These have all been highlighted as key competencies for psychological practice (von Treuer and Reynolds, Reference von Treuer and Reynolds2017). For this LFT exercise, the formulation models and reflections provided an avenue for assessing, and giving feedback on the depth of analysis of the cognitive components involved, the congruence in perceived interactions between cognitions, emotions and behaviours, and on the self-maintaining processes of dysfunction (i.e. problematic secondary responses, negative reinforcement processes). These are all key areas highlighted by declarative teaching in early cognitive behavioural training (Beck, Reference Beck2020; David et al., Reference David, Lynn and Montgomery2018; Ellis, Reference Ellis1994a). Similarly, the development of the individualised LFT exercises allowed for the assessment of competency in setting an appropriate behavioural challenge for addressing issues with frustration/distress tolerance. The reflection also provided the opportunity for the trainees to highlight and integrate learning taken from the experience, a key process in the effectiveness and reinforcement of such behavioural interventions (Craske et al., Reference Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek and Vervliet2014; Harrington, Reference Harrington2011; Pittig et al., Reference Pittig, Treanor, LeBeau and Craske2018). The verbal instruction for the SR element of the task also prompted consideration of how the exercise could be improved, allowing for assessment of self-reflective learning, which is considered a meta-competence that is important for a practitioner’s ongoing development (Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Davis, Chaddock, Whittington and Grey2014; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Cairns, Bennett-Levy, Johnston, Lowrie, Robinson and Perry2015; von Treuer and Reynolds, Reference von Treuer and Reynolds2017). Finally, conducting the exercise in the SP/SR framework provided an opportunity for individualised feedback to the trainees on their development of these skills.

As previously suggested, further development of reflective questions could enhance the focus on the development of core competencies for psychological practice (Collard and Clarke, Reference Collard and Clarke2020). In line with von Treuer and Reynolds’ (Reference von Treuer and Reynolds2017) focus on competency in evidence-based interventions and evaluation of their application, prompts could be provided for participants to reflect on ways the behavioural experiment could have been tailored more specifically to the presenting issue or deepened, how safety or avoidant behaviours could be addressed, and how key learning could be reinforced or generalised. Such prompts would be in line with principles highlighted by inhibitory learning processes (Craske et al., Reference Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek and Vervliet2014).

Learning from the LFT exercise

In the written reflections on the LFT exercise, the trainees indicated that the exercise had the capacity for assisting with both personal and professional development. These outcomes included a deepened understanding of CBT theory, enhanced empathy for client struggles, and improved interpersonal functioning.

Declarative and procedural learning

In summarising and reflecting on the formulations of their reactions to engaging in the LFT exercises, the participants reported a deepened appreciation for cognitive, emotional and behavioural cycles. This included observations of how such factors interacted in self-maintaining patterns, comments on how automatic and strong such cycles could be, how these cycles could trigger other secondary cycles of dysfunction, and on the effort required to change these patterns. In addition to the behavioural task itself, many of the participants utilised other interventions to assist them with the change processes; this allowed for a greater appreciation for the utility and challenges of applying such strategies. In terms of the change process itself, participants noted a deepened appreciation for how engaging in the LFT exercise helped to create cognitive, emotional and behavioural changes for themselves. A number also noted that by focusing on changing their usual habits, they gained improved self-awareness and some also commented that by focusing on changing themselves they were able to develop greater interpersonal skills and improve interpersonal dynamics.

Such learning from SP/SR training has consistently been reported in the literature (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019; Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Thwaites, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2019; Gale and Schröder, Reference Gale and Schröder2014; McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015; Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016). In particular, it has been reported that SP/SR training leads to an enhanced appreciation for the cognitive behavioural model and the process of change (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001; Haarhoff et al., Reference Haarhoff, Gibson and Flett2011; McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015). The increased appreciation of urges and behaviours to reduce emotional discomfort, whether related to anxiety or frustration and anger, is also in line with previous findings from the SP/SR literature relating to anxiety and avoidant and compensatory behaviours (Collard and Clarke, Reference Collard and Clarke2020; McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015). The reflections on the additional coping strategies to assist with going through the behavioural challenge are also consistent with the existing literature, which has shown that practice in a SP/SR framework deepens the appreciation of such techniques, their limitations, and contributes to an enhanced ability to adapt them (Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Thwaites, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2019; Gale and Schröder, Reference Gale and Schröder2014; McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015). This has been found to subsequently increase trainees’ confidence in their competence with these techniques (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Thwaites, Freeston and Bennett-Levy2015).

Self-awareness

By engaging in the exercise, a significant number of participants directly reported that they developed increased self-awareness. This included a greater understanding of tolerance beliefs, and their relationship to worries, expectations of self and others, related emotional experiences of anxiety, anger and guilt, and behavioural habits. Such increases to self-awareness are in line with previous research, which has consistently found this to be an outcome of SP/SR training programs (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019; Gale and Schröder, Reference Gale and Schröder2014; McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015; Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016). This has been suggested to be a mechanism through which SP/SR training can help trainees to develop their competence, their therapy style, and for the development of skill in managing more complex presentations (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001; McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015).

Interpersonal skills

In the SP/SR literature, increased empathy for client difficulties is a frequently cited outcome of such training, with subsequent improvements to interpersonal skills thought to result from this (Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Thwaites, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2019; Gale and Schröder, Reference Gale and Schröder2014; Spendelow and Butler, Reference Spendelow and Butler2016). For many of the exercises, this may be an indirect outcome of the trainee being able to relate their own personal experiences with that of clients or increased confidence with a technique. Such an outcome was demonstrated in this study, with some of the participants highlighting an increased awareness for the difficulties with behaviour change. While a smaller number of participants directly commented on the translation of this to empathy for future clients, this may have been drawn out further if there had been more guidance provided in the directions given to the trainees. The structure of SR guidelines has previously been suggested to influence the type and depth of reflections provided by participants (Collard and Clarke, Reference Collard and Clarke2020; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Cairns, Lowrie, Robinson, Haarhoff and Perry2017).

As noted above, SP/SR has been suggested to increase interpersonal skills required for treating more challenging presentations (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019). Based on the reflections provided by some of the participants, LFT exercises may potentially develop such skills in a more direct manner than other similar training techniques. For instance, for those that targeted interpersonal frustrations with the exercise, it challenged them to directly address beliefs relating to tolerance and acceptance of others’ behaviour. This also promoted prosocial behaviour changes, which may have been planned or occurred as a response to a shift in cognitive and emotional processing of interpersonal frustrations. As a result, some participants directly noted improvements to their interpersonal skills and interpersonal relationships as an outcome of the exercise. This may have subsequent benefits for managing challenging client presentations where clients struggle to make progress or behave in a more confronting manner.

Challenges with using a LFT exercise for SP/SR

None of the participants in the sample reported a negative evaluation of the LFT exercise overall. While many noted challenges in breaking negative reinforcement cycles or noted increased emotional discomfort, either from abstaining from their usual habits or from becoming more aware of them, they all noted positive learning from the experience. This may have been a result of the design of the task, giving participants control over the developed exercise, which has been shown to facilitate greater engagement in SP/SR training (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014). The focus on frustration may also have mitigated the risk of negative responders, compared with a pure exposure exercise.

Limitations and future directions

The limitations of this study are in line with those reported in a previous paper where we assessed the utility of a social anxiety exposure exercise for CBT training on the same cohort (Collard and Clarke, Reference Collard and Clarke2020). This included design limitations based on the subjective trainee reports, the short-term focus of the study, potential for further direction with the reflective component, the use of the task as an assessment task, and potentially confounding factors provided from the overall course. There was even a wider range of exercises selected for the LFT task than for the social anxiety exposure task, which while important for providing trainees with a sense of control over the exercise (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014), does provide for a greater heterogeneity of experiences. This was somewhat addressed by providing voluntary opportunities for sharing of experiences, but the outcomes of such sharing were not assessed. Sharing could also have potentially been enhanced by encouraging or structuring opportunities for anonymous sharing in the course (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015).

The ability to generalise the findings to other behavioural exercises is limited, but these findings were consistent with previous research utilising such strategies within a SP/SR training program (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2003; Collard and Clarke, Reference Collard and Clarke2020). The study was also limited to novice trainees. It would therefore be important to assess outcomes for more experienced trainees.

Conclusion

The application of an LFT exercise within a SP/SR training programme was reported to provide for a ‘deeper’ appreciation of CBT theory and practice. The exercise provided for an enhanced appreciation for how behavioural exercises can improve self-awareness, a deepened appreciation for cognitive, emotional and behavioural cycles of dysfunction, appreciation for the effort required to break negative reinforcement cycles, and promoted a greater belief in capacity for change. The exercise was challenging for participants, but well received. Participants noted positive outcomes in terms of personal and professional development. In particular, it was reported to directly contribute to improvements in interpersonal tolerance and social skills for those selecting exercises with an interpersonal focus. Finally, using these exercises within a SP/SR framework appears to have the potential to provide a method of competency-based training for psychological assessment, formulation, intervention delivery, and review.

Key practice points

-

(1) Use of an LFT behavioural exercise within a SP/SR framework assists trainees in developing a ‘deeper’ level of understanding of CBT theory and its application to anxiety, frustration and anger issues.

-

(2) Practice of an LFT exercise within a SP/SR framework provided trainees with a greater appreciation of the utility of behavioural interventions for working with anxiety, frustration and anger.

-

(3) Although initially considered challenging by trainees, the use of the technique as a form of experiential learning was well received.

-

(4) With experiential learning exercises it appears important to provide bridging questions to assist trainees to shift from reflection on personal development to professional development.

-

(5) Use of behavioural experiments within a SP/SR framework provides for the application of competency-based assessment in relation to formulation and intervention skills.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

James Collard: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal); Michael Clarke: Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethics statements

Authors have abided by the APS Code of Ethics as set out by the Psychology Board of Australia. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants in the study. The study was approved by the Cairnmillar Institute Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number 2019/0207CMI).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, J.C., upon reasonable request.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.