Romantic Afterlife in a Modern Century

We began this book with the long tail of Romantic nationalism in post-1918 Europe, from ‘Die Wacht am Rhein’ to Alexander Nevsky, tempered in the fire of wartime experiences; Chapter 11 ended with the war that gave those memories their enduring stature and their ambivalent nature as ultranational and unpolitical at the same time. That war ended with the Paris Peace Treaties, governed by the Wilsonian principle of national self-determination. The assertion of national identity – something that had been aspirational in the century of empires – became a default in the century of nation-states. What had been an agenda became a habit, subsisting in a post-1918 dominated by technological modernity and rejecting Romanticism and its (re-) enchantments.

Even so, a century after the Paris Peace Treaties, nationalism is once again the strongest ideology worldwide, as it was in 1914. These days, it is accompanied by new forces such as neoliberalism and political Islam and proves capable of inflecting both. From Trump’s USA to Xi’s China, from Putin’s Russia to Erdoğan’s Turkey, from Modi’s India to Netanyahu’s Israel, we see how nationalism rides high, regardless of the specifics of states, their histories and local politics.

The way nationalism survived into the twenty-first century is astounding. Across the totalitarian ideologies of Communism, Fascism and Nazism; across a World War that dwarfed even the ruinous frenzy of the first one, with an unprecedented wholesale slaughter of entire populations; across, also, a half-century of liberal internationalism in the West and anticolonial self-liberation in the Global South, nationalism has proved its resilience and adaptability.

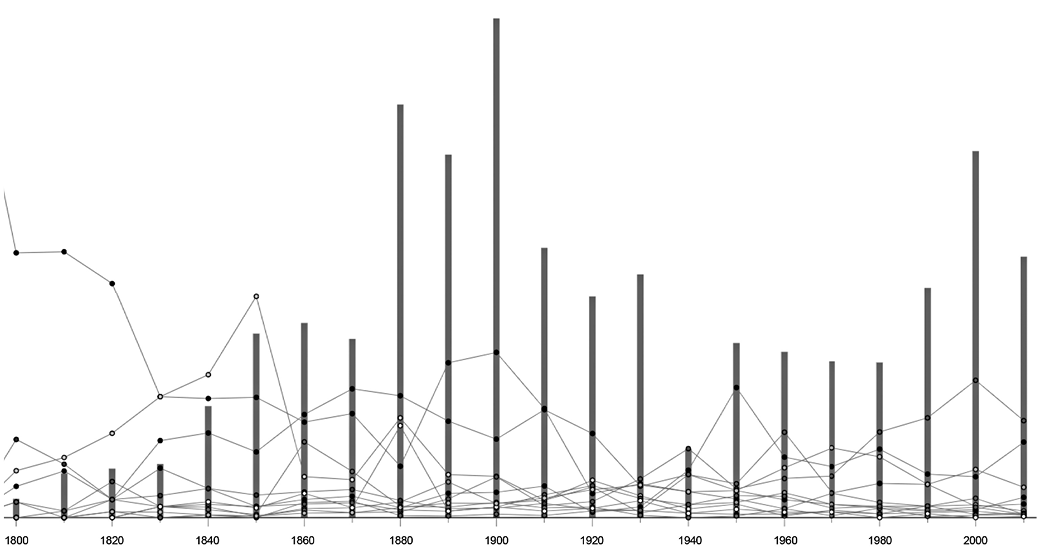

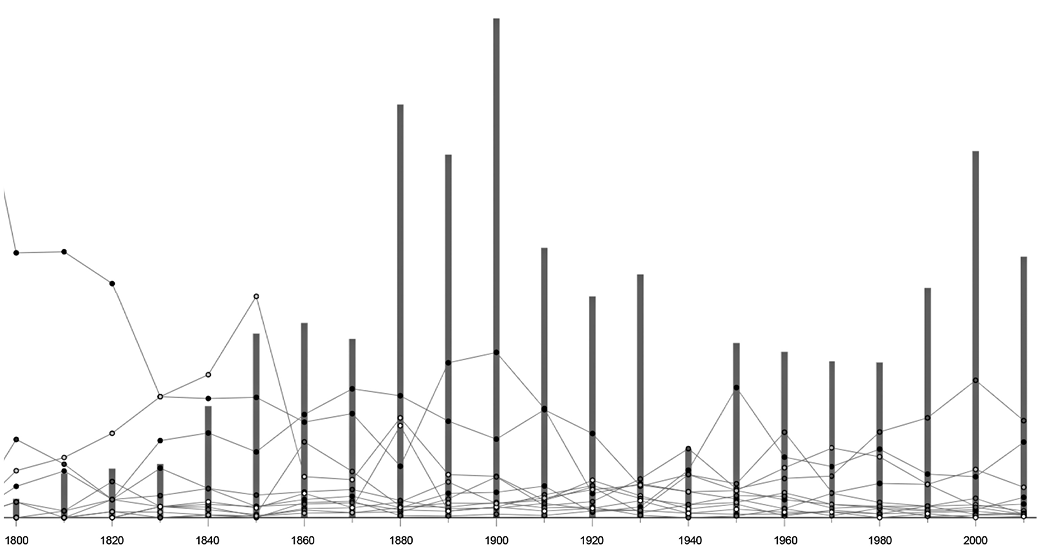

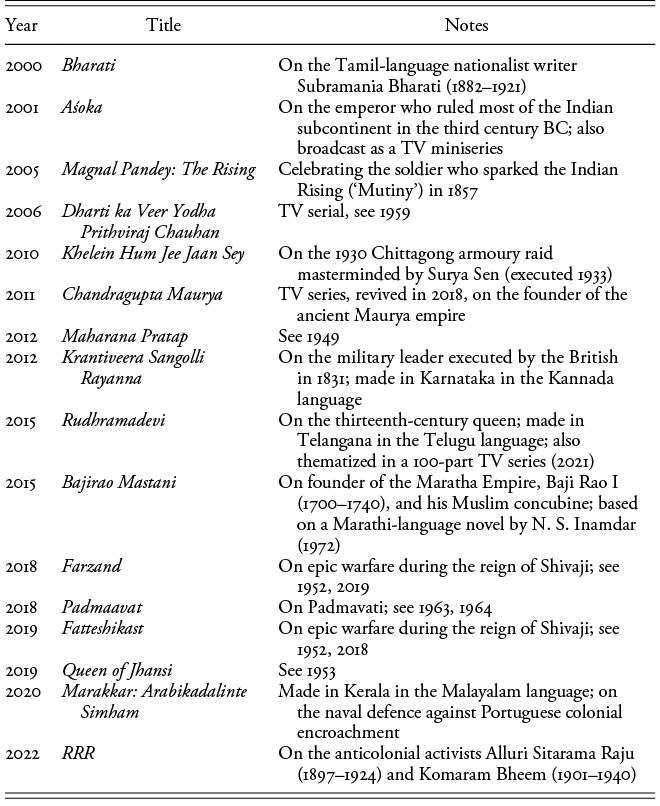

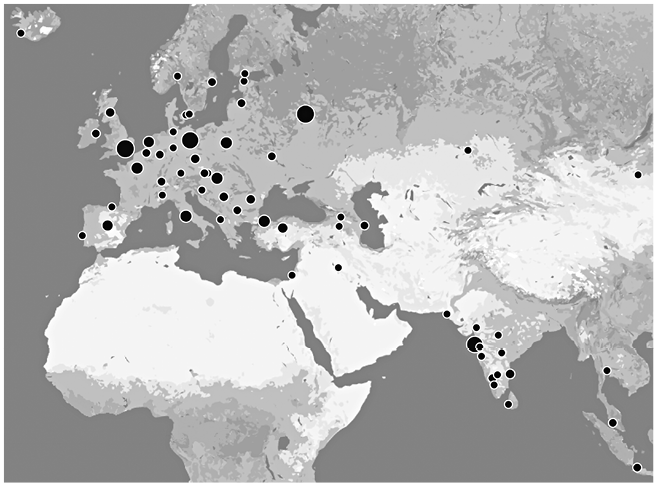

The resurgence of nationalism in public culture is aptly illustrated by plotting, on a timeline, the erection of national commemorative monuments (Figure 12.1). The graph visualizes the distribution of around 7,500 monuments; the bars represent the totals per decade (highest: 841 in 1900–1910, 279 of which in Germany), the lines the proportional share of the various nationalities.

The totals offer a profile something like a suspension bridge. A sudden rise after 1800 peaks between 1880 and 1910; then the curve descends to a low point in the 1940s, followed by restrained productivity into the 1980s; and then a renewed rise into the 2000s and after. Production is dominated in the nineteenth-century heyday by German, Italian and French statues and in the period 1980–2010 by Hungarian, Russian and Polish ones. Obviously, the post-communist countries went through a ‘catching up’ exercise in public-space historicism when, belatedly, they were in a position to do so, and at a time when the fashion had already passed in Western Europe. That offers a vivid illustration of the often-noted asymmetry between the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ Europe, the ‘old’ being the western half that was liberated from totalitarian dictatorships in 1945 and the ‘new’ being the eastern half, which would have to endure tyranny until 1989. But there is also a deeper asymmetry between the two halves: in the west, the state system continued much as it had been in 1913; whereas most of the states of Central and Eastern Europe were carved out of dismembered empires in 1919.

The American delegation had come to the 1918 Paris peace conference charged with Wilson’s ‘Fourteen Points’ agenda, stipulating the right of ‘peoples’ to self-determination. How those ‘peoples’ could be mapped onto territories had been intensely studied, by way of preparation, by geographers and other scholars (a group known as ‘The Inquiry’, including Walter Lippmann). We have seen the comments of one of their collaborators, Leon Dominian, concerning Serbia as ‘the country of the gusle’ (Chapter 5). The self-determination principle was applied somewhat selectively: mainly in order to dismember the empires on the losing side (Hohenzollern, Habsburg, and the Ottoman Empire, at least its European portion). The situation was more chaotic for the outlying provinces of Russia (the southern Caucasus, the Baltic lands, Ukraine), which had gone through a revolution and a separate peace treaty with the central powers (Brest-Litovsk, March 1918). Warfare in fact continued after 1918 from Finland to Armenia as new states consolidated themselves under contested regime choices and then tried to stave off incorporation into the new USSR. The states of Western Europe were on the whole left intact; Norway was confirmed in the independence from Sweden that it had peaceably obtained in 1904, the foundations for Icelandic self-government under the Danish crown were laid, and Ireland was engaged in a war of independence that would lead to a self-governing Irish Free State with dominion status in 1922. Cultural minorities in the west, such as Brittany, the Basque country and Catalonia, continued an agenda of identity-assertion in a spectrum ranging from regionalism to separatism.

The newly sovereign states all asserted their status by proclaiming their national distinctness and authenticity, fully in the mode of the Romantic nationalism of the preceding century, but of course in a drastically modernized climate. Most of them in their new constitutions prefixed a clause affirming that the state was predicated on the nation’s identity and established the national language as its language of affairs and education. Indications of how Romantic nationalism was expressed in a modern century can be inferred from the examples of Latvia, Ireland and Poland.

In Latvia, an epic silent film was made in 1930 under the title Lāčplēsis. It celebrates the heroic vindication of the national cause in a story set during the recent War of Independence and its aftermath. A wicked German attempts to rape a young woman but is thwarted by a hero-figure, the independence fighter Jānis, who saves the day. That action is presented, however, as the contemporary iteration of a deeply underlying myth: that of the legendary hero Lāčplēsis freeing the medieval heroine Laimdota from the evil Black Knight. The same actors play the mythical and the contemporary roles, and the film creates visual overlays, double-exposure transitions and echoic repetitions between the modern and the mythical. The film made use of the Latvian epic of the same name (‘the bear-slayer’), one of those many national epics that had been produced across Europe (Chapter 4); the Latvian author Andrejs Pumpurs had begun his version of Lāčplēsis in order to create a counterpart to the Estonian Kalevipoeg, and after toying with the idea of a pseudo-ancient counterfeit presented it in 1880 as a modern text based on local legends. Pumpurs’s Lāčplēsis looks back to the medieval Livonian crusades, when the Teutonic Order subdued the Baltic lands; the incorporation of that tale in the modern anti-German film brings history around full circle. The young hero Jānis, whose imagination has been fired by reading a dog-eared copy of Pumpurs’s epic, has magically been made receptive to the spirit of the mythical hero and recognizes in the arrogant Prussian the ancient wicked Black Knight. The epic hero is, in the most literal sense, an inspiration for modern freedom fighters. And so a modern melodrama of national independence and evil rapists is calqued onto the Romantic-national epic; this is done, however, in a film drawing heavily on the modern, avant-garde stylistic techniques of German expressionist cinema (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari) and Sergey Eisenstein (Battleship Potemkin) and intercut with newsreel footage.

This remarkable film is only one example of the many ways in which modern, independent Latvia was channelling the spirit of Lāčplēsis.1 Lāčplēsis memorials dot the country and testify to its historical vicissitudes. One, on the façade of the Riga parliament building, replaced an earlier statue of the Teutonic Landmeister Walter von Plettenberg; it was itself removed under Communist rule in the 1950s and a replica was put up in 2007. Similarly, Lāčplēsis defeating the Black Knight was the subject of a 1932 statue (inscribed ‘To the liberators’) honouring the Latvian troops that had taken Jelgava in 1919; erected in 1932, it was destroyed in or after World War II and restored in 1992.2

A statue of Lāčplēsis was also included in 1935 on the plinth of the remarkable symbolist/art deco ‘Freedom Monument’ that towers over downtown Riga. Here, the bear-slayer is rendered much as in the film (woollen skullcap, bobbed haircut). He was similarly represented on a postage stamp of 1932, where, as in the film, his face hovers in the clouds above the Riga skyline like a protective spirit (Figure 12.2).Footnote * Thus we see the national hero remediated from epic poem to statuary to film and postage stamps. The first step in that progress moves within the established ambit of traditional art forms. Then film and stamps provide new, twentieth-century distribution media.3 The postage stamp in particular was a ubiquitous platform. Signifying the independence of the state, its currency and its postal service, it habitually featured the nation’s semi-official iconography and provided it with possibly the deepest and widest social penetration ever achieved by the graphic arts. The trend started in 1896 when Greece issued classically themed stamps to celebrate the Olympic Games held in Athens. Only in the decades of post-1945 internationalism, when many small countries and newly independent colonies began to make use of stamps as a cheap but popular marker of international presence, do we see an internationalization of philatelic icons – Marie Curie, Leonardo and in the Communist world Karl Marx.4

Figure 12.2 Latvian postage stamp of 1932, part of a series based on the 1930 film Lāčplēsis.

Similar dovetailings of historicism and modernity are noticeable at the presence of newly independent states such as Ireland and Poland at world fairs of the interwar period. Both countries considered themselves to be anciently rooted states now restored to their erstwhile sovereignty. Both used the modern, forward-looking and even futuristic platform of the world fair to showcase both their modern viability and their ancient rootedness. The Irish self-presentation was more traditionalist. At the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago, a ‘Pageant of the Celt’ was held, harking straight back at the legendary-historicist repertoire of the Irish Literary Revival (which remained popular anyway among the Irish-American diaspora); more pragmatic was the distribution of an instructive Handbook of the Irish Free State, with geographical and statistical information, presented in a sumptuously neo-Celtic design modelled on the country’s greatest cultural heirloom, the medieval Book of Kells.5

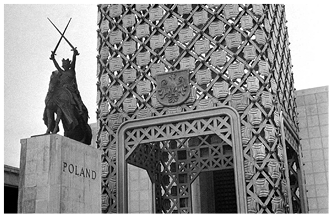

The Polish state, well aware of its parlous position between Germany and the USSR, saw in the world fairs of the 1930s a necessary tool of cultural diplomacy and invested much in its pavilions; it opted for a modernistic pavilion style replete with references to the rich Polish past. On the very eve of Hitler’s invasion, in 1939, it marked its presence at the New York World’s Fair with a striking flat-roofed prefab building, fronted by an openwork tower constructed out of 1,200 gilded shields and overlooking an old-school, traditionally academic-style equestrian statue of the medieval king Jagiello I brandishing two crossed swords (Figure 12.3). The New York public failed to get the historical reference in this modern building, some people believing that the statue represented the contemporary Polish strongman leader Marshal Piłsudski – as well they might, since some of the material had been transported to New York on a freight ship named Piłsudski.6

Figure 12.3 Polish pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

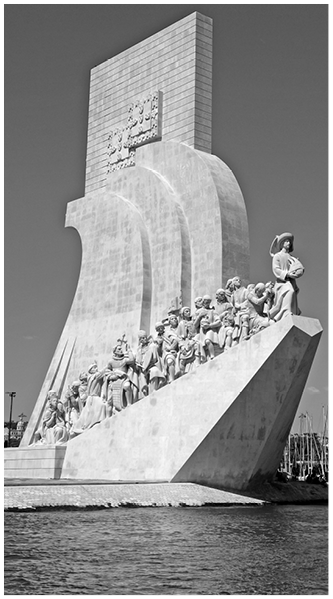

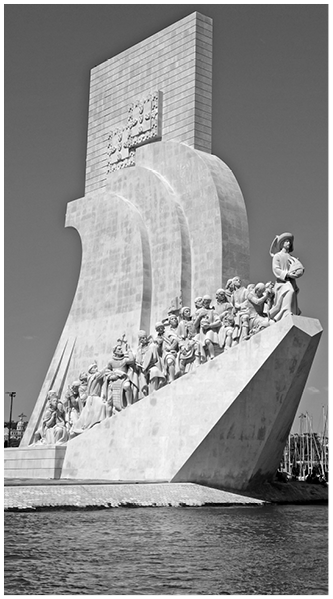

And so world fairs resumed their function after the Great War had ended. The former imperial peripheries of Europe as sovereign state participants continued their Romantic-nationalist identity affirmations by other means, embedding it in modernist forms and shapes. And it was not only the new states; even the very oldest caught the tide of post-Romantic cultural nationalism. In Lisbon, a World Exhibition was held in 1940 to mark 800 years since the foundation of Portugal and 300 years since the restoration of independence from Spain. The fair was a publicity exercise of the authoritarian regime, the Estado novo; it was opened by Marshal Carmona, the country’s nominal president, with de facto dictator Salazar also in attendance. Various streets around the fair grounds were renamed in the following years to evoke the period of colonial discoveries; but the eye-catcher was a large monument glorifying the nation’s achievements in the colonial voyages of discovery – perpetuating the triumphalism of the Columbus monument at the Barcelona Universal Exposition of 1880. In 1960 it was replaced by a stone successor, still one of Lisbon’s main landmarks (Figure 12.4). Portugal in 1960 still considered itself a colonial empire, and Salazar was still in power.7

Figure 12.4 Monument to the Portuguese Discoveries, Belém, Lisbon (António Pardal Monteiro and Leopoldo de Almeida, 1960).

Democracy and Ethnocracy

Names such as Piłsudski and Salazar alert us to the fact that the continuance of Romantic nationalism in the twentieth century was not only affected by a modernist shift in aesthetics and media technology; the political ground was shifting as well. Our view of the interwar years tends to be dominated by the twin juggernauts of Hitler and Stalin, with, as afterthoughts, Mussolini and Franco. But the cases of Poland, Portugal and Latvia alert us to the fact that those dictators were not an anomaly: they represented a general European trend. We have encountered the strong, indeed charismatic leaders of former war commanders in the post-war states, Piłsudski among them. In some cases, they represented a continuity from the imperial pre-1914 days: Hindenburg in Germany, Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk) in Turkey, Horthy in Hungary. In other cases, they had used their military know-how to ensure their new country’s independence: Mannerheim in Finland, Piłsudski in Poland. Mannerheim honourably relinquished power after losing the 1919 elections, but in Poland Piłsudski abolished parliamentary government and became de facto dictator as of 1926. Other coups d’état involving military leaders were those of Primo de Rivera (1923) and Franco (1936) in Spain, Óscar Carmona in Portugal (1926) and Ioannis Metaxas in Greece (1936). We may even include France’s Philippe Pétain in that list; his rise to power in Vichy France was dictated by war circumstances, but he undoubtedly used his charisma (having been the heroic defender of Verdun) as a springboard towards running a nationalist dictatorship.8

If we add to those generals the other autocratic leaders of nationalist non-democracies, the list grows to dismal proportions. The poet-turned-pilot Gabriele D’Annunzio started the trend by proclaiming himself duce of the Istrian city of Fiume/Rijeka; Italy’s Mussolini followed suit in 1922. Then came Zogu in Albania (1925, ‘King Zog’ as of 1928), Antanas Smetona in Lithuania (1926), Engelbert Dollfuß and Kurt Schuschnigg in Austria (1932 and 1934), Konstantin Päts in Estonia and Kārlis Ulmanis in Latvia (both 1934), Boris III in Bulgaria (1935), Carol II in Romania (1938, followed by Ion Antonescu in 1940), Vladko Maček in Yugoslavian Croatia (1939). Hitler’s power grab in 1933 was only one in a series. From 1917/1922 (the coups of Lenin and Mussolini) to 1975/1989 (the deaths of Salazar and Ceauşescu), the European twentieth century is mostly one of dictatorships.

That is how the application of the Wilsonian principle of national self-determination derailed. The notion of national self-determination, involving the people’s liberation from alien overlordship and imperial oppression, had originally been meant as a democratic gesture. Sieyès, the champion of the tiers-état and godfather of its assemblée nationale in 1789, would have firmly approved of Wilson’s programme. But the newly constituted nation-states, many of them liberated from the rule of imperial overlords, eagerly ditched their democratic freedoms in favour of authoritarianism or dictatorships.Footnote * Many countries in Eastern and Central Europe, which subsequently got mangled between Hitler’s Third Reich and Stalin’s USSR, recall those succeeding tyrannies with anguish but with a historical foreshortening that makes it seem as if this Nazi–Bolshevik double whammy put an end to their recently acquired liberty and self-determination. Not so: almost all of them had already, of their own volition, imposed dictatorships on themselves in the run-up to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

Many of these anti-democratic movements justified their power grabs by claiming that the imminent threat of a communist revolution had to be averted; we even encounter this, bizarrely, in Ireland’s Blueshirt movement. Surely Ireland in 1930, a self-governing, Catholic, agricultural and traditionalist country, was almost as impervious to a communist takeover as the Vatican; in the end, the Blueshirt movement remained quixotic, though it inspired the national poet W. B. Yeats to write anti-democratic ‘marching songs’ for it, and the spectre of a Bolshevik threat was widely used as a scare tactic. In fact, Ireland is, like Finland, one of the few new (post-1918) countries where democratic stability prevailed and manifested itself in the peaceful transfer of power following general elections – even though both had gone through ruinously divisive internal wars in the early days of their independence. As of 1933, the government of Ireland, though by no means authoritarian, was under the strongly paternalistic leadership of Eamon De Valera. A deeply committed Irish nationalist, he had been an anti-British separatist insurgent and was prone to a type of Catholic integralism also practised in Spain and Portugal. Still, that was not ipso facto anti-democratic: a similar national paternalism characterized anti-Fascist leaders such as Charles De Gaulle, Winston Churchill and Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, strong-willed personalities who all believed in their transcendentally imposed (rather than democratically mandated) stewardship of the nation.Footnote *

Not all nationalists, then, were authoritarians; but all authoritarians (west of Stalin, that is) were nationalists. The B-list of European dictators of the interwar years all invoked a mission to vouchsafe the survival of the nation and the fatherland. Overtly so, as we can tell by the names and mottos of the movements they headed: the Patriotic Union for Primo de Rivera, the falangists with their shouted call-and-response España: una – España: grande – España: libre, the Lithuanian Nationalist Union for Smetona, the Fatherland Front for Dollfuß and Schuschnigg, the Action française and so on. From the days of the Ligue des patriotes to the Front national, the invocation of the nation and the flag-waving assertion of national identity is massively overrepresented on the right wing of the political spectrum. It is among the political right that that national flag is the most sought-after cloak to wrap one’s politics in.9

The track record of post-imperial European nation-states in the 1920s in retrospect appears like a prefiguration of the more recent drift (usually linked to the notion of ‘populism’) towards strongman authoritarian leaders with a charismatic media presence and a nationalist agenda. Once liberated from foreign-imposed tyranny, the newly independent Central European governments turned, as Spain, Portugal and Italy had done, to homegrown nativism and xenophobic nationalism, invoking it if necessary to derogate the powers of parliament, the independence of the judiciary, the international rule of law as established by treaties and the freedom of the press. All this was rationalized by the categorical imperative of national identity, and the legacy of Romantic historicism was heavily drawn on, instrumentalizing a national past as canonized by nineteenth-century historians and artists.

That inter-war trend has been echoed across Europe in recent decades, Italy under Berlusconi leading the way to Boris Johnson and Victor Orbán and their ilk. What this parallel across the intervening decades suggests is that there may well be an inherent instability in the very concept of the ‘nation-state’, even though now it is often accepted as the default model for a democracy.

Scholars in nationalism studies are keenly aware of the heuristic distinction between civic and ethnic nationalism. It has been overworked in the past but is nevertheless an indispensable distinction since, as we have repeatedly seen in the foregoing pages, the very concept of the nation hovers between two connotations: the nation as the common society that derives a sense of shared purpose and solidarity from being co-responsible for the state and its governance; and the nation as the cultural community that derives its sense of joint identity from a shared descent and inherited culture (language and memories). In most cases, the two are intermingled; but the proportion in which the two are commingled can be established only if we have a sense of the ideal-typical, civic versus ethnic nature of the ingredients that make up the mix. Those components are habitually called by the two Greek names for ‘the people’ in a political or a cultural sense: demos and ethnos. The shifting emphases with which nationalism presents itself as civic or ethnic reflects the way in which the nation is defined, or self-defines, as demos (the citizen stakeholders of a state) or ethnos (the people sharing the same culture).

The ambivalence in the very concept of the nation-state is a direct consequence of the vacillation in the self-definition of the nation as demos or ethnos. As stated before, the Wilsonian self-determination of peoples was initially meant as a democratic principle. It is for that very reason that Churchill, an old school imperialist, resisted its readoption, post-1945, in the Atlantic charter and by the United Nations: it could be invoked by colonially subjected peoples and Churchill, as a British imperialist, was not prepared to allow that.

Although the idea of national self-rule was meant democratically, as citizens’ freedom from foreign overlordship, we note that in many cases it gravitated in a direction we may call ethnocratic: the rule not of the demos (the people as a social body) but of the ethnos (the people as a cultural community). The rhetoric of contemporary populism oscillates between demotically motivated anti-elitism and ethnically motivated nativism. The denunciation of over-educated, smugly liberal elites, out of touch with the worries that affect the common people, can always emerge out of, or shade into, the warnings against swarms of immigrants or unassimilated denizens from a culturally hostile world, aided and abetted by those cosmopolitan elites.10

The nation-state may be inherently vulnerable to a gravitation from democracy towards ethnocracy. And despite the intervening totalitarian dictatorships and a World War, and despite the horrified recoil from totalitarianism in post-1945 internationalism, that ethnocratic gravitation, away from democracy, affects the nation-state today as much as it did a century ago.

Nationalism after Decolonization

Studying the ‘afterlife’ of Romantic nationalism after 1918 would require a multi-volume work rather than this single chapter – given the seismic intensity, the magnitude and the ongoing duration of the political turbulence in the century since the Treaty of Versailles. Globalization, and the decentring of Europe’s position in the world, had been announced in the world’s trading economy (witness the world fairs) and was now vastly amplified by the end of the European empires. The break-up of the Romanov, Habsburg, Hohenzollern and Ottoman Empires in 1917–1919 was accompanied in Western Europe by the imperial breakdown of Spain (Cuba and the Philippines, 1898), Britain (Ireland 1922, South Africa 1931, India and Pakistan 1947, Kenya 1964), Denmark (Iceland 1944), the Netherlands (Indonesia 1948), Belgium (Congo 1960), France (Indochina 1954, Algeria 1962) and Portugal (Angola and Mozambique, 1975). Each of those dates (and the list is only indicative) represents a hugely complex process. Remarkably, that imperial break-up was a process that spanned across the worst and most ruinous war in human history.

Nationalism in Europe’s former colonies was, on the whole, driven less by a ‘cultivation of culture’ than by political and economic independence. Asserting the right to self-determination among disenfranchised colonials is primarily a struggle against political and economic injustice rather than Romantic identity assertion as in nineteenth-century Europe. Identity-driven, nativist nationalism can, however, be encountered globally: a drift towards ethnocracy was as noticeable outside Europe as it was within Europe’s new nation-states. By way of example (random but telling) I point readers to places as far apart as South Africa, Israel and India. In South Africa, a mythology emerged during the Boer Wars of stalwart, biblically devout Boer intransigence, exemplified and commemorated in events such as the ‘Great Trek’ and the exodus of the Boers in trains of ox-drawn wagons to a new home in the Transvaal. Afrikaner nationalism was the result; it combined post-defeat grievance politics with equal measures of fundamentalist Calvinism and white supremacism. Afrikaner nationalism found a radical champion in Oswald Pirow, a Nazi sympathizer who in 1940 published a ground plan for a ‘New Order’ in South Africa, ambiguously inspired by Salazar’s Estado novo and/or by Nazi Germany. The political figurehead of Afrikaner nationalism, the Calvinist preacher Daniel François Malan, leader of a Reunited National Party, formalized South Africa’s system of apartheid in 1948. In 1958, Pirow acted as chief prosecutor in the ‘treason trials’ that saw Nelson Mandela arraigned for the first time, accused not of just of sedition but of high treason against the South African republic. In Israel, the two-state Zionism of David Ben-Gurion vied with the Jewish supremacist revisionist Zionism of Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the Mussolini-inspired intellectual godfather first of the Hatzohar and Herut movements and ultimately, indirectly, of Likud. In India, Gandhi’s anticolonialism was accompanied by a wide palette of Hindu nationalist movements. Many of these were inspired by the Hindutva (‘Hindu-ness’) nationalism of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, who after 1938 became an admirer of Hitler; the Bharatiya Janata Party eventually issued from that Hindutva-inspired tradition.11

Within the European heartlands of the former empires, post-imperial nostalgia took hold. The loss of colonies and of trans-European power coincided with, or amplified, a more general nostalgic undercurrent under the surface of high modernity. Miguel de Unamuno’s journeys inwards to the various regions and villages of the Spanish heartland (recounted in Paisajes, 1902; De mi país, 1903; Andanzas y visiones españolas, 1922) were part of a cultural reaction to the calamitous colonial losses of the (proverbially traumatic) year 1898. In Germany, the tradition of the idyllic Dorfgeschichte continued in force after 1918 and engendered the rustic tales of ‘blood and soil’ as well as the first cinematic versions of rustic idylls.Footnote * These Heimatfilms became all-dominant in the post-1945 period of defeat and Wiederaufbau (‘economic reconstruction’).12

In Britain, the nostalgic mode of ‘Englishness’ similarly drew on nineteenth-century sentimental idyll, continued in the downmarket fiction of the 1920s known as ‘love and loamchild’, as well as the magic realism of John Cowper Powys and various Powell and Pressburger films, hinting at the lingering presence of ancient memories encoded within the English landscape itself.13 An eternal England, remembered from childhood and outlasting history and the Empire itself, was evoked by Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin in his famous lecture to the English nationalist Society of St George in 1924:

The sounds of England, the tinkle of hammer on anvil in the country smithy, the corncrake on a dewy morning, the sound of the scythe against the whetstone, and the sight of a plough team coming over the brow of a hill, the sight that has been in England since England was a land, and may be seen in England long after the Empire has perished and every works in England has ceased to function, for centuries the one eternal sight of England.14

That evocative, practically verbless conspectus of sights and sounds leads naturally enough to the conclusion that ‘The love of these things is innate and inherent in our people.’ Fichte would have approved. The sentiments were echoed (with some sarcasm, but still) in George Orwell’s reflection on the war effort, The Lion and the Unicorn (1941), from which Conservative Prime Minister John Major cherry-picked one soundbyte in 1993 and inserted it in a neo-Baldwinesque context:

Fifty years from now Britain will still be the country of long shadows on county grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and pools fillers and – as George Orwell said – ‘old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist’ and if we get our way – Shakespeare still read even in school.15

Reading Shakespeare in school: that sting in the tail is, of course, a dogwhistle to a national, traditionalist educational policy. It also circles back to the fountainhead of this type of English nationalism: Thomas Carlyle’s celebration of Shakespeare as a cornerstone of English identity in On Heroes and Hero-Worship.

National nostalgia is still with us, and it, too, alternates between salience and dormancy. The Heimatfilm dropped steeply out of fashion in Germany in the mid-1960s, to the point of becoming proverbial as the nadir of kitsch after 1968. As such it was evoked in 1984, with ironic back-handedness, as a point of departure for Edgar Reitz’s experimental film/TV series Heimat (with sequels in 1992 and 2004), which combined a coming-of-age story with a regionalist exploration of the communal and generational memories of a fraught German century. Since then, the layered ironies of the 1980s have evaporated, and the Heimatfilm has become once again, straightforwardly, a romance genre for undemanding mass consumption (now, of course, featuring strong female characters). Such are the alternations and dialectics of cultural taste.

Similarly, in France, after the nouvelle vague had trashed the cinéma de papa (their term for the complacent commercial movies of the 1950s) and had produced, across the 1960s and 1970s, an edgy, urban avant-gardism, the 1980s saw mellow regionalism return in force: the twin films Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources (1986, based on works by the regionalist author and film-maker Marcel Pagnol). A similar resurgence of nostalgic comfort viewing occurred around the same time in British cinema: after the ‘swinging sixties’, period costume drama returned in the 1980s, lovingly evoking Victorian or Edwardian England (Chariots of Fire, 1981), with at best some vestigial ironies inherent in the source material (the Merchant-Ivory productions of E. M. Forster’s A Room with a View, 1985, and Howards End, 1992). The BBC produced many idyllic costume dramas, drawing on canonical works of Victorian vintage (George Eliot, Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell, Anthony Trollope), and serialized the rural memoirs of Flora Thompson (Lark Rise to Candleford, published 1939–1943, broadcast 2008–2011). In the 2010s, marked by austerity and leading up to Brexit, there was the remarkable vogue of Downton Abbey (TV series 2010–2015, film spin-offs 2019, 2022 and 2025), with its mellow afterglow of a Baldwin-style harmony of squires and servants, castles and cottagers.Footnote *

These examples, few and somewhat randomly chosen as they are, do have indicative value and offer food for thought. For one thing, the dates of Heimat, Chariots of Fire and Jean de Florette suggest that a return to a nostalgically national cultural repertoire preceded the downfall of communism in 1989, coinciding with the Falklands War and the growth of Rambo-style martial action-hero movies in the US; and that therefore it is problematic to explain the revival of nationalism at the end of the twentieth century purely and simply as a response to ‘1989’. The new nationalism is often represented as a palliative to the agoraphobia of globalization and the disintegration of a bipolar world system post-1989; but the cultural material suggests the gestation a new nationalism starting in the 1980s. When communism vanished from the political landscape as an ideological presence, and well before globalization went into overdrive by the end of the century, the feel-good factor of national identity was already there, poised, standing by.

The Nation at the Movies

In flagging the post-1918 alternating dormancy/salience cycles of national nostalgia, I have drawn on examples from cinema and television, the twentieth-century’s new media par excellence. Those particular new media proved their power in many genres: documentaries, love stories, adventure romance, psychological drama and so on. Among all those things, it was highly suitable for dramatizing and visualizing the nation, uniting the narrative and the spectacle of national identity, either as a foregrounded theme or as an underlying frame. As such, cinema offered a new platform for Romantic nationalism in a technological, post-Romantic age.

Given that function, we can use film history data as an Ariadne’s thread through the mixed, mashed-up track record of the twentieth century. Instead of attempting, in these closing pages, an exhaustive conspectus of cultures of nationalism in twentieth-century Europe, I trace instead a single cultural tradition through the labyrinth, tracking post-Romantic nationalism in its cinematic articulation. Cinema, the century’s stand-out new art form, has been encountered numerous times across the pages of this book, from Casablanca to Birkebeinerne. Of all narrative genres, cinema was and is truly representative of the twentieth century: high-tech, mass-audience, global, reaching from downmarket commercialism to art-house aesthetics.16

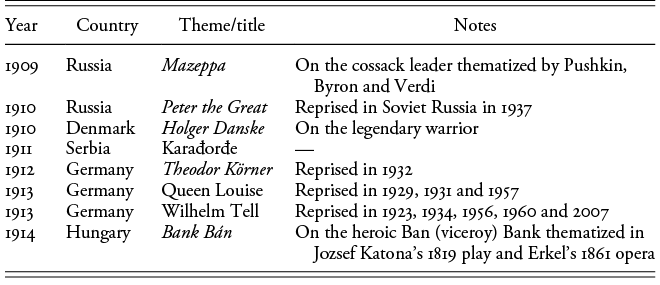

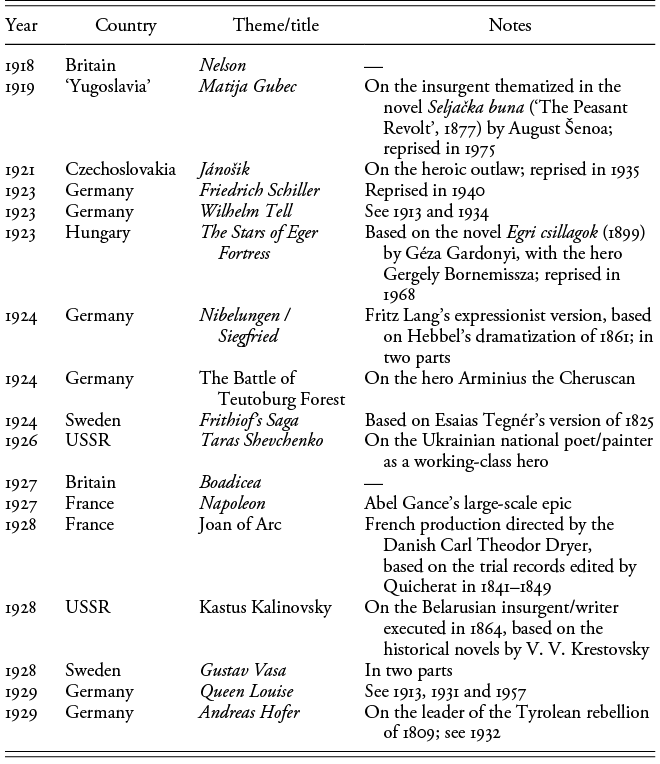

We have seen how the Latvian film Lāčplēsis recycled national-Romantic legends in the new medium of film, even with its avant-garde aesthetics. Even before 1918, cinema had proved its suitability for patriotic, Romantic-historical narratives, largely in the mode of the dramatization of great national figures. Tables 12.1a, 12.1b and 12.1c indicate a productivity that is fairly evenly distributed across Europe.Footnote *

| Year | Country | Theme/title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1909 | Russia | Mazeppa | On the cossack leader thematized by Pushkin, Byron and Verdi |

| 1910 | Russia | Peter the Great | Reprised in Soviet Russia in 1937 |

| 1910 | Denmark | Holger Danske | On the legendary warrior |

| 1911 | Serbia | Karađorđe | — |

| 1912 | Germany | Theodor Körner | Reprised in 1932 |

| 1913 | Germany | Queen Louise | Reprised in 1929, 1931 and 1957 |

| 1913 | Germany | Wilhelm Tell | Reprised in 1923, 1934, 1956, 1960 and 2007 |

| 1914 | Hungary | Bank Bán | On the heroic Ban (viceroy) Bank thematized in Jozsef Katona’s 1819 play and Erkel’s 1861 opera |

| Year | Country | Theme/title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1918 | Britain | Nelson | — |

| 1919 | ‘Yugoslavia’ | Matija Gubec | On the insurgent thematized in the novel Seljačka buna (‘The Peasant Revolt’, 1877) by August Šenoa; reprised in 1975 |

| 1921 | Czechoslovakia | Jánošik | On the heroic outlaw; reprised in 1935 |

| 1923 | Germany | Friedrich Schiller | Reprised in 1940 |

| 1923 | Germany | Wilhelm Tell | See 1913 and 1934 |

| 1923 | Hungary | The Stars of Eger Fortress | Based on the novel Egri csillagok (1899) by Géza Gardonyi, with the hero Gergely Bornemissza; reprised in 1968 |

| 1924 | Germany | Nibelungen / Siegfried | Fritz Lang’s expressionist version, based on Hebbel’s dramatization of 1861; in two parts |

| 1924 | Germany | The Battle of Teutoburg Forest | On the hero Arminius the Cheruscan |

| 1924 | Sweden | Frithiof’s Saga | Based on Esaias Tegnér’s version of 1825 |

| 1926 | USSR | Taras Shevchenko | On the Ukrainian national poet/painter as a working-class hero |

| 1927 | Britain | Boadicea | — |

| 1927 | France | Napoleon | Abel Gance’s large-scale epic |

| 1928 | France | Joan of Arc | French production directed by the Danish Carl Theodor Dryer, based on the trial records edited by Quicherat in 1841–1849 |

| 1928 | USSR | Kastus Kalinovsky | On the Belarusian insurgent/writer executed in 1864, based on the historical novels by V. V. Krestovsky |

| 1928 | Sweden | Gustav Vasa | In two parts |

| 1929 | Germany | Queen Louise | See 1913, 1931 and 1957 |

| 1929 | Germany | Andreas Hofer | On the leader of the Tyrolean rebellion of 1809; see 1932 |

| Year | Country | Theme/title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1931 | USSR | The Koliivščyna Uprising | On an insurgency, based on Shevchenko’s epic poem Hajdamaky (‘The Outlaws’) of 1841 |

| 1931 | Germany | Louise, Queen of Prussia | See 1913 and 1929 |

| 1932 | Germany | The Rebel | The protagonist is based on Andreas Hofer (see 1929); allegory of refusal to abide by the terms of the Versailles Treaty; highly appreciated by the Nazi leadership |

| 1932 | Germany | Theodor Körner | See 1912 |

| 1934 | Germany | Wilhelm Tell | See 1913 and 1923 |

| 1934 | Netherlands | William of Orange | — |

| 1934 | Italy | Villafranca | Risorgimento-themed film based on a play by Mussolini |

| 1934 | Italy | The 1,000-Man Army of Garibaldi | — |

| 1935 | Czechoslovakia | Jánošik | See 1921 |

| 1935 | Belgium | Ulenspieghel Still Lives | On the abiding spirit of the trickster folk hero (celebrated in Charles de Coster’s 1867 novel) in the Flemish character |

| 1935 | Italy | Ettore Fieramosca | After the 1833 novel by Manzoni |

| 1936 | Britain | Rhodes of Africa | Celebrating the imperialist Cecil Rhodes |

| 1937 | USSR | Peter the Great | See 1910; in two parts |

| 1938 | Poland | Kosciuszko at the Battle of Racławice | — |

| 1938 | France | The Marseillaise | On the anthem’s nation-building effect in 1792 |

| 1938 | Italy | Giuseppe Verdi | — |

| 1938 | USSR | Alexander Nevsky | — |

| 1939 | USSR | Minin and Pozharsky | On two anti-Polish resistance heroes in 1611–1612 |

A few striking patterns emerge from this list. The production spread was pan-European (albeit skewed towards Germany, Central–Eastern Europe and Italy). The themes are almost invariably of nineteenth-century vintage. Even when themes or heroes from an earlier period are thematized, the film versions tend to follow the canonized version of events as laid down by Romantic writers and historians (Schiller being the main conduit for Wilhelm Tell). In that sense, most of these films are remediations of nineteenth-century Romantic historicism in a new, high-tech medium. What is also noticeable is the thematic repetitiveness: many of these films return to the themes of earlier ones. That is partly due to the technical innovations of the medium. Sound film would return to topics covered previously in silent movies, now obsolete, and the later advent of colour or extra-large formats would stimulate similar recyclings.

On the other hand, that pattern is also characteristic of canonicity as such. Whatever enjoys canonical status is, almost by definition, a repeatedly reactivated – not a dormant or inert – cultural presence: like repeated performances of Shakespeare plays or reprints of Les Misérables. What is more, canonicity seems to project these repetitions and reactivations across different media and makes use of new media as they emerge: operas and films based on Shakespeare plays; graphic-novel renderings of Les Misérables as well as audio books and films and musicals, and musicals turned into films. And so we can phrase the principle both ways: film is a new habitat for classics of Romantic-nationalist vintage; and also the cultural canon established by Romantic nationalism was successfully remediated into the emerging new media of cinema and television.

In the present century, DVD and then streaming video have become the dominant platforms for viewing, eroding the centralized distribution of the twentieth century (cinemas, broadcasting corporations); at the same time, this more diffused mode of home-viewing distribution has been counterbalanced by a collectivized, internet-based mode of reviewing (websites, blogs, discussion channels, social media). But ‘cloudification’ (domestic consumption, online discussion) affects only the distribution and reception patterns of cinematic drama. Production costs have remained high, and studios and broadcasting corporations remain important producers.

Even in the 1920s and 1930s, the signs of globalization were there. In India, a film was produced about the nation-building King Harishchandra as early as 1913. Post-1918, the foundations were laid for what later would become the largest film industry worldwide. Some early films are already national consciousness-raisers invoking the subcontinent’s proud past and rich heritage. Bhakta Vidur (‘The devotion of Vidura’, 1921) dramatized an episode from the classic Mahabharata epic, but it was banned by the British authorities because they felt it to be an allegorical endorsement of Gandhi. Gandhi’s presence was also noticeable in the first Indian talking movie in Tamil and Telugu, Kalidas (1931, now lost), which celebrated the Sanskrit poet of that name but included publicity songs of the Congress Party and in praise of Gandhi. The first Marathi talkie, The King of Ayodhya (1931, with a Hindi-language version in 1932) returned to the figure of King Harishchandra. The 1933 historical drama Sinhagad was an adaptation of a 1903 historical novel by Hari Narayan Apte celebrating the inspiring figure of the Marathi warrior-monarch Shivaji, a widespread lieu de mémoire in modern India’s developing national consciousness; he would be thematized again in films in 1952, 2018 and 2019. The 1936 biopic of the seventeenth-century Saint Tukaram (Marathi, again) marked the breakthrough of Indian cinema on the international scene: it won high praise at the 1937 Venice film festival. Inside India it was seen as an exemplification of the non-violent values of Gandhi-style nationalism.

And there was, of course, Hollywood. The films discussed here are from a period that is bracketed by two American classics. The earlier one was D. W. Griffiths’s Birth of a Nation (1915), a landmark of American cinema and, be it added, a diatribe of southern states resentment, white supremacism and Ku Klux Klan glorification (it was based on Thomas Dixon’s racist novel The Clansman, 1905). The American south was also the setting of the period’s later-date bookend: Gone With the Wind (1939), in which cinema exploded into full-colour large-screen spectacle. The premiere took place in Atlanta, the city whose burning marks the film’s dramatic high point midway; a screening was held in 1961 to mark the centenary of the Civil War’s outbreak. In successive reissues, its format was enlarged to widescreen and then to 70mm. Its status as a national classic stands at odds with the middlebrow book that provides the screenplay: Margaret Mitchell’s 1938 novel was typical of the bodice-ripping romances into which the Scott format of the historical novel had declined. No War and Peace this; yet it aptly caught the most incisive crisis in American history in a passionate combination of private, feminine-focused romance and national historical epic. Its enduring persistence in post-war American culture was compounded and reinforced by a similarly constructed television series, North and South (1985–1994), based on the 1980s trilogy by John Jakes.Footnote *

The cases of India and the US indicate strong lines of continuity across World War II. Within Europe, the years 1940–1945 marked a caesura.

Cold-War Asymmetries

The years 1940–1945 saw some historicist propagandistic films in the ‘Great Men’ mode: Soviet films on the Cossack hetman Khmelnitsky (1941), on the victorious general Suvorov (1941), on the Armenian hero Davit Bek (1944). The Third Reich produced films on Schiller and Bismarck (both 1940) and – embracing Dutch/Afrikaans – Rembrandt (1936) and the Boer leader Kruger (1941); Portugal chipped in with a biopic on Camões (1941).

The most notable nationalist film to come out of the war years was Goebbels’s massive pet project Kolberg (1945), a lavish full-colour production completed even as the Third Reich was collapsing. Its storyline, set in the days of Napoleonic hegemony, was meant to encourage the German public in its dire straits: how a town held out against overwhelming odds, mobilizing the population one and all, until as if by a magic dispensation the fortunes of war turned and the mighty foes were vanquished. The anti-Napoleonic wars of liberation were a favourite point of reference for Goebbels, with frequent references to the verse of Theodor Körner.Footnote * But the film, like the Reich itself, sank in ruination.

The years of the Cold War show a remarkable asymmetry in production on the two sides of the Iron Curtain. Much propagandistic English-language movie entertainment, increasingly enmeshed in a Hollywood-dominated anglosphere, celebrated the heroism of the bygone war effort, first during the war years and afterwards as well. Wartime propaganda continued to be produced well after the war had actually ended and became a form of popular celebratory remembrance. In the Netherlands, the 1971 memoirs of a resistance hero were filmed by Paul Verhoeven, first as film (Soldier of Orange, 1977) and then as a television miniseries (For Queen and Country, 1979). The film in turn was made into a musical that premiered in 2010; Soldaat van Oranje has been on an uninterrupted run since then, with 3.5 million tickets sold, and is arguably the country’s most important mnemonic platform in its remembrance of the Nazi occupation.

War commemoration was couched and made popular in dramatic action tales – also, in the G. A. Henty tradition, for boys, witness the ‘Biggles’ series by Captain W. E. Johns, and comic strips with such titles as Commando, Warlord and Battle Picture Weekly – pulp comics that rendered shouts of Achtung! and Schnell, schnell, Schweinhund! widely familiar.17 For Johns, the war never really ended: to the initial Biggles stories, set in the Great War, were added tales of the plucky pilot battling first the Nazis and then, after 1945, international communists and criminals. The timeline of military-hero comics also gravitates from the 1960s to the 1980s: War Picture Library ran from 1958 to 1984, Commando from 1961 to the present, Warlord from 1974 to 1986 and Battle Picture Weekly from 1975 to 1988. As those dates indicate, this mass-produced cartoon view of history continued right up to the moment when cinema took up the cue, Indiana Jones snarled his ‘Nazis! I hate those guys!’ and Rambo ‘got to win this time’.

Throughout these Cold War decades, John Wayne starred multifunctionally, either as a sheriff in the Wild West or as an officer fighting the Nazis or the Japanese; British cinema evoked the exploits of navy vessels under their benign paternalist captains, from In Which we Serve (1942) and We Dive at Dawn (1943) to The Cruel Sea (1953). World War II movies morphed into heroic action in the 1960s (The Guns of Navarone, 1961; The Longest Day, 1962; The Great Escape, 1963; The Dirty Dozen, 1967). The genre then moved into the cheaper domain of television serials (the comedy Dad’s Army, 1968–1977; Colditz, 1972; Secret Army, 1977–1979; the spoof ’Allo ’allo, 1982–1992). National self-glorification in the epic pre-1940 mode took a back seat to a simple scheme of ‘we the heroes’ versus ‘them the villains’. At best these productions deployed, seriously or comically, standard ethnotypes to characterize heroes and villains in the national-characterological clichés of 1914 vintage: sadistic, technocratic or rigidly unimaginative Germans versus mercurial French charm, quietly courageous English ‘pluck’ and energetic American ‘can-do’.

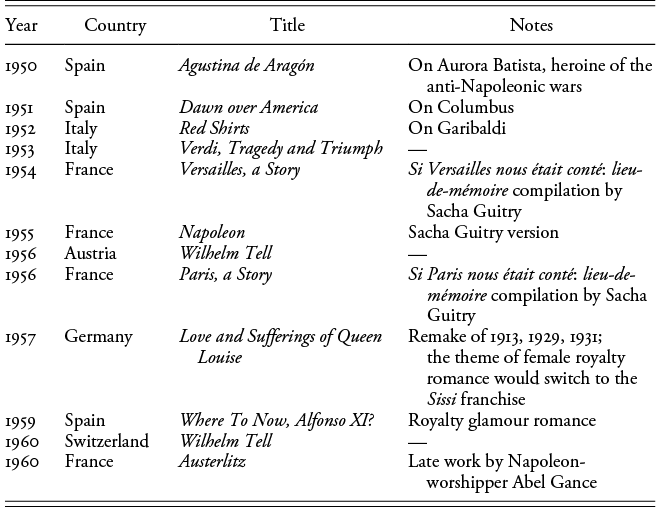

In the West, war movies such as these largely supplanted the patriotic-heroic epic of earlier decades. Still, a steady trickle of Romantic-historicist dramas continued in Western Europe after 1945, with Franco’s Spain as an added production area (see Tables 12.2a and 12.2b). The genre subsided into ambient unobtrusiveness.

| Year | Country | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Spain | Agustina de Aragón | On Aurora Batista, heroine of the anti-Napoleonic wars |

| 1951 | Spain | Dawn over America | On Columbus |

| 1952 | Italy | Red Shirts | On Garibaldi |

| 1953 | Italy | Verdi, Tragedy and Triumph | — |

| 1954 | France | Versailles, a Story | Si Versailles nous était conté: lieu-de-mémoire compilation by Sacha Guitry |

| 1955 | France | Napoleon | Sacha Guitry version |

| 1956 | Austria | Wilhelm Tell | — |

| 1956 | France | Paris, a Story | Si Paris nous était conté: lieu-de-mémoire compilation by Sacha Guitry |

| 1957 | Germany | Love and Sufferings of Queen Louise | Remake of 1913, 1929, 1931; the theme of female royalty romance would switch to the Sissi franchise |

| 1959 | Spain | Where To Now, Alfonso XI? | Royalty glamour romance |

| 1960 | Switzerland | Wilhelm Tell | — |

| 1960 | France | Austerlitz | Late work by Napoleon-worshipper Abel Gance |

| Year | Country | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Italy | Viva l’Italia! | On Garibalidi, by Rosselini |

| 1964 | Scotland | Culloden | Dramatized documentary |

| 1965 | Sweden | Gustav Vasa | — |

| 1966 | Germany | Nibelungen | In the sword-and-sandals style; in two parts |

| 1967 | Spain | The Adventures of Cervantes | — |

| 1967 | Germany | Arminius the Cheruscan | — |

| 1969 | Britain | Alfred the Great | — |

| 1973 | Britain | Bequest to the Nation | Romantic drama about Nelson’s relationship with Lady Hamilton |

| 1980 | Basque country | Sabino Arana | Now possible in the post-Franco years |

| 1981 | Spain | Cervantes | — |

| 1981 | Britain | Chariots of Fire | Pan-British ‘band of brothers’ win medals at Parisian Olympics of 1924 |

| 1982 | Italy | Verdi | TV miniseries |

| 1983 | Wales | Owain Glendower | Made for Welsh television (Channel 4 Cymru) |

| 1984 | Germany | The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest | TV production of Kleist’s Die Hermannsschlacht (1808) |

| 1984 | Flanders | The Lion of Flanders | After the 1838 historical novel by Hendrik Conscience, De Leeuw van Vlaenderen; produced both as film and as TV miniseries |

| 1984 | Netherlands | William of Orange | TV miniseries |

| 1987 | Italy | Garibaldi | TV miniseries |

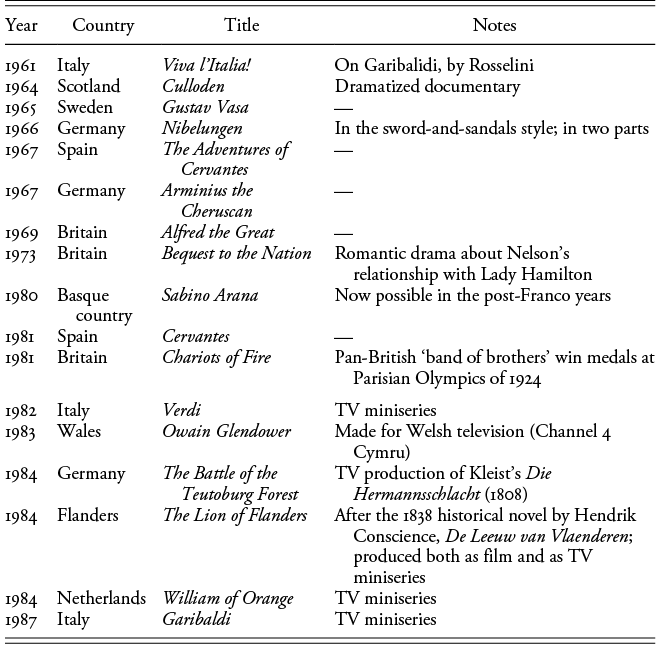

The decline of French cinematic productivity after the end of the Fourth Republic in 1958 is striking – coinciding with the vehement rejection of the cinéma de papa. The temporal dynamics here are almost exactly in tandem with the periodicity of the decline and revival of idyllic rusticism as noted earlier, reaching a low ebb in the 1960s and 1970s and reviving in the 1980s with a shift towards TV. Heroic historicism goes into an almost total eclipse in the 1970s, which may perhaps be correlated with the coming of age of a baby-boom cohort that combined anti-authoritarianism with an anti-historicist turn. There is, however, an emergence of sub-national, regionalist films on Basque, Scottish, Welsh and Flemish themes, extolling the subaltern. And here as in the case of rusticism, a pronounced revival of patriotic history films begins in the 1980s, drawing markedly on the medium of television.Footnote *

As the mention of the nouvelle vague indicates, there was a general shift in tastes. Westerns and war movies were receding as well, overtaken by contemporary-set drama, thrillers, romantic comedies both urban and rustic-idyllic, and magic realism and science fiction. Even the war movies, dedicated to heroism in the national service, situated this heroism in a struggle not against other nations but against Nazism. In Western Europe’s post-1945 ideological landscape, nationalism was, for once, a weak force – as we can also see from the steep drop in national commemorative monuments around this time (Figure 12.1). Internationalism thrived instead. The trend for multinational co-productions and multinational all-star casts became pronounced, and politically international relations were dominated by multilateralist organizations such as the United Nations, the European Economic Community and NATO – for the main enemy was now the Communist bloc.

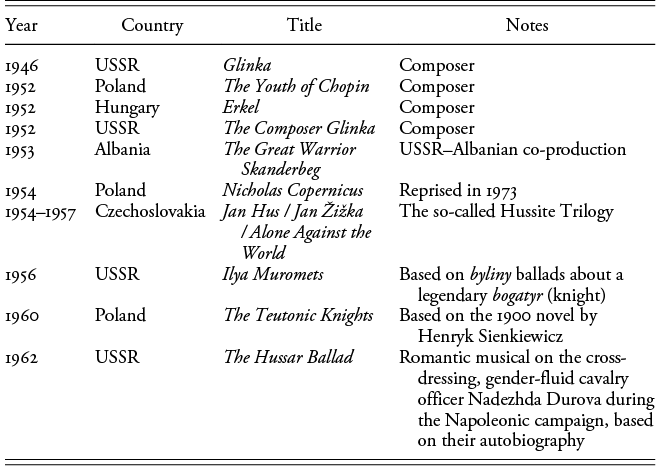

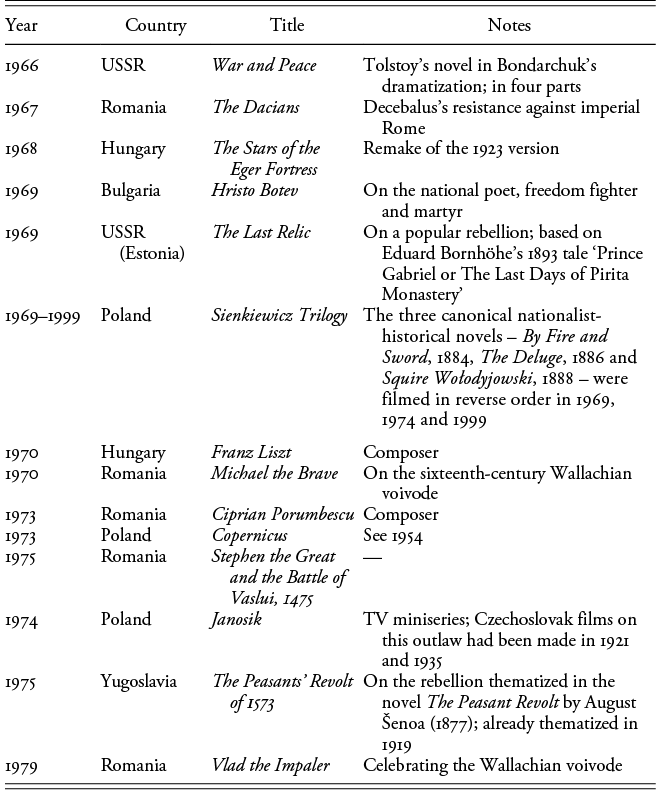

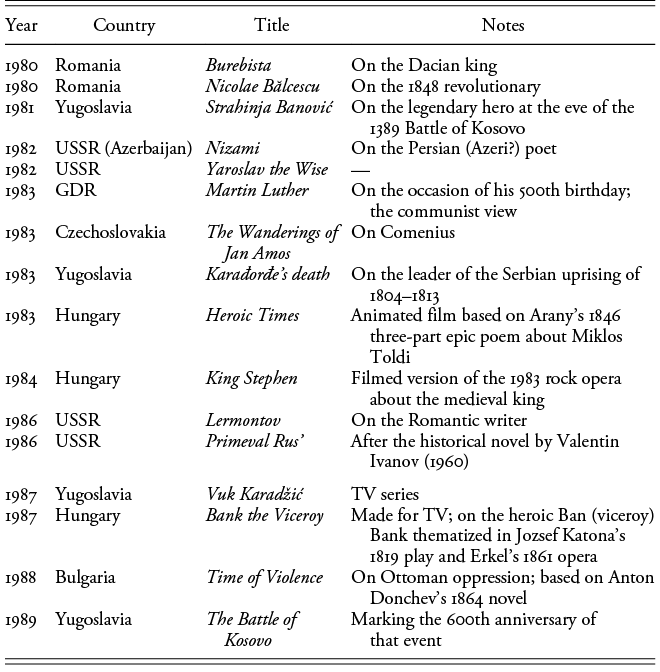

The cinema of the Communist eastern bloc presents a different aspect, with a more intensive and sustained productivity that patently continues the cinematic remediation of Romantic nationalism (nineteenth-century heroes, and themes made familiar by nineteenth-century novels). For the Cold War years, Tables 12.3a, 12.3b and 12.3c list a lone Albanian film (on the nation’s über-hero Skanderbeg) and a single East German one, two films from Bulgaria, four from Czechoslovakia (including a bizarre trilogy where Jan Hus appears to be motivated by a Stalinist class consciousness), five from Yugoslavia, six each from Hungary and Romania, eight from Poland and ten from the USSR (including the Soviet republics of Estonia and Azerbaijan). That total of forty-two national-heroic film productions is fifty per cent higher than that of Western Europe during the same period.

| Year | Country | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | USSR | Glinka | Composer |

| 1952 | Poland | The Youth of Chopin | Composer |

| 1952 | Hungary | Erkel | Composer |

| 1952 | USSR | The Composer Glinka | Composer |

| 1953 | Albania | The Great Warrior Skanderbeg | USSR–Albanian co-production |

| 1954 | Poland | Nicholas Copernicus | Reprised in 1973 |

| 1954–1957 | Czechoslovakia | Jan Hus / Jan Žižka / Alone Against the World | The so-called Hussite Trilogy |

| 1956 | USSR | Ilya Muromets | Based on byliny ballads about a legendary bogatyr (knight) |

| 1960 | Poland | The Teutonic Knights | Based on the 1900 novel by Henryk Sienkiewicz |

| 1962 | USSR | The Hussar Ballad | Romantic musical on the cross-dressing, gender-fluid cavalry officer Nadezhda Durova during the Napoleonic campaign, based on their autobiography |

| Year | Country | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | USSR | War and Peace | Tolstoy’s novel in Bondarchuk’s dramatization; in four parts |

| 1967 | Romania | The Dacians | Decebalus’s resistance against imperial Rome |

| 1968 | Hungary | The Stars of the Eger Fortress | Remake of the 1923 version |

| 1969 | Bulgaria | Hristo Botev | On the national poet, freedom fighter and martyr |

| 1969 | USSR (Estonia) | The Last Relic | On a popular rebellion; based on Eduard Bornhöhe’s 1893 tale ‘Prince Gabriel or The Last Days of Pirita Monastery’ |

| 1969–1999 | Poland | Sienkiewicz Trilogy | The three canonical nationalist-historical novels – By Fire and Sword, 1884, The Deluge, 1886 and Squire Wołodyjowski, 1888 – were filmed in reverse order in 1969, 1974 and 1999 |

| 1970 | Hungary | Franz Liszt | Composer |

| 1970 | Romania | Michael the Brave | On the sixteenth-century Wallachian voivode |

| 1973 | Romania | Ciprian Porumbescu | Composer |

| 1973 | Poland | Copernicus | See 1954 |

| 1975 | Romania | Stephen the Great and the Battle of Vaslui, 1475 | — |

| 1974 | Poland | Janosik | TV miniseries; Czechoslovak films on this outlaw had been made in 1921 and 1935 |

| 1975 | Yugoslavia | The Peasants’ Revolt of 1573 | On the rebellion thematized in the novel The Peasant Revolt by August Šenoa (1877); already thematized in 1919 |

| 1979 | Romania | Vlad the Impaler | Celebrating the Wallachian voivode |

| Year | Country | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Romania | Burebista | On the Dacian king |

| 1980 | Romania | Nicolae Bӑlcescu | On the 1848 revolutionary |

| 1981 | Yugoslavia | Strahinja Banović | On the legendary hero at the eve of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo |

| 1982 | USSR (Azerbaijan) | Nizami | On the Persian (Azeri?) poet |

| 1982 | USSR | Yaroslav the Wise | — |

| 1983 | GDR | Martin Luther | On the occasion of his 500th birthday; the communist view |

| 1983 | Czechoslovakia | The Wanderings of Jan Amos | On Comenius |

| 1983 | Yugoslavia | Karađorđe’s death | On the leader of the Serbian uprising of 1804–1813 |

| 1983 | Hungary | Heroic Times | Animated film based on Arany’s 1846 three-part epic poem about Miklos Toldi |

| 1984 | Hungary | King Stephen | Filmed version of the 1983 rock opera about the medieval king |

| 1986 | USSR | Lermontov | On the Romantic writer |

| 1986 | USSR | Primeval Rus’ | After the historical novel by Valentin Ivanov (1960) |

| 1987 | Yugoslavia | Vuk Karadžić | TV series |

| 1987 | Hungary | Bank the Viceroy | Made for TV; on the heroic Ban (viceroy) Bank thematized in Jozsef Katona’s 1819 play and Erkel’s 1861 opera |

| 1988 | Bulgaria | Time of Violence | On Ottoman oppression; based on Anton Donchev’s 1864 novel |

| 1989 | Yugoslavia | The Battle of Kosovo | Marking the 600th anniversary of that event |

Again, in many cases, the screenplays were based on pre-1914 novels or history books (Sienkiewicz, Bornhöhe, Šenoa, Arany, Donchev). The heroes represent a peculiar sociological selection: monarchs/warlords, proletarian outlaws/revolutionaries, and a slew of composers, poets and intellectuals.

Readers are probably bewildered by this array, some of whose names (Chopin, Copernicus) stand out amidst the numerous unfamiliar ones. But none of the names in Tables 12.3(a-c) are obscure. The monarchs, warlords, insurgents and artists/intellectuals: all have monuments and thoroughfares named after them in their countries’ capitals, and they appear on banknotes and postage stamps. The films merely add to the commemorative cult that for each and every one of them had begun in the Romantic historicism of the nineteenth century. Much more remarkable is their sociological background, which emphatically includes and celebrates the elite, and which follows in the footsteps of a canon established by pre-socialist, ‘bourgeois-liberal’ authors, lacking class consciousness. That wholesale adoption by the communist regimes is puzzling. To account for this apparent anomaly, we should realize that in Marxist literary and cultural criticism ‘bourgeois patriotism’ was seen as an unobjectionable albeit obsolete stage in society’s historical progress towards class consciousness and class struggle. These ‘bourgeois-patriotic’ productions apparently were acceptable enough for the communist regimes to be recycled as entertainment, if necessary draped in some class-consciousness or as prefigurations of the present-day leaders. Many of these films became popular and were fixtures, broadcast annually on TV on public holidays. (And a turn towards TV production is noticeable here, as elsewhere, in the 1980s.) Some of the productions were instrumentalized by post-1968 communist leaderships (gestures towards youth culture during the later Kadar regime in Hungary; Ceauçescu’s Romanian exceptionalism and his leadership cult). Others laid the foundations for what after the fall of communism would become foregrounded preoccupations in the new cultures of nationalism, for example the Kosovo myth in Serbia or the Polish sense of being surrounded by enemies on all sides (the dominant self-image in Sienkiewicz’s novels).

The ongoing cultural presence of post-Romantic national historicism during the Cold War years stands in contrast to the genre’s decline in the West in the decades of the baby-boomers’ counter-culture. The sudden resurgence of nationalism as the leading ideology after the downfall of communism in Eastern Europe cannot be seen in isolation from the latent persistence of ‘bourgeois patriotism’ and the ongoing affirmation of the nation as a feel-good factor under communist rule. While in the West between 1945 and 1989 nationalism was frowned upon, or at best ambient and ‘banal’, it remained discreetly influential in communist Eastern Europe.18

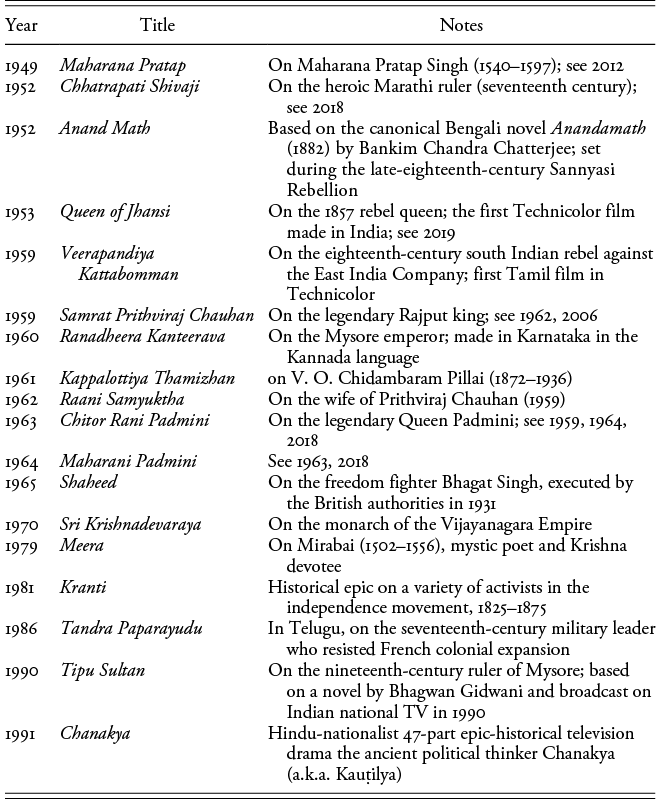

Meanwhile, outside Europe

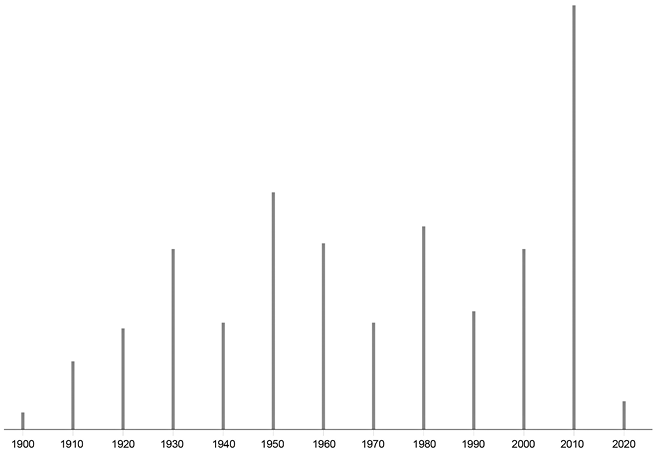

In India, now an independent country, cinematic nationalism was neither dormant nor latent but very much present. Here the film industry was burgeoning, and the dominance of patriotic content continued in the early post-independence decades.19 This persisted without much discontinuity across the 1989 divide and intensified after 2000 in a climate of growing Hindu nationalism (Tables 12.4a and 12.4b).

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1949 | Maharana Pratap | On Maharana Pratap Singh (1540–1597); see 2012 |

| 1952 | Chhatrapati Shivaji | On the heroic Marathi ruler (seventeenth century); see 2018 |

| 1952 | Anand Math | Based on the canonical Bengali novel Anandamath (1882) by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee; set during the late-eighteenth-century Sannyasi Rebellion |

| 1953 | Queen of Jhansi | On the 1857 rebel queen; the first Technicolor film made in India; see 2019 |

| 1959 | Veerapandiya Kattabomman | On the eighteenth-century south Indian rebel against the East India Company; first Tamil film in Technicolor |

| 1959 | Samrat Prithviraj Chauhan | On the legendary Rajput king; see 1962, 2006 |

| 1960 | Ranadheera Kanteerava | On the Mysore emperor; made in Karnataka in the Kannada language |

| 1961 | Kappalottiya Thamizhan | on V. O. Chidambaram Pillai (1872–1936) |

| 1962 | Raani Samyuktha | On the wife of Prithviraj Chauhan (1959) |

| 1963 | Chitor Rani Padmini | On the legendary Queen Padmini; see 1959, 1964, 2018 |

| 1964 | Maharani Padmini | See 1963, 2018 |

| 1965 | Shaheed | On the freedom fighter Bhagat Singh, executed by the British authorities in 1931 |

| 1970 | Sri Krishnadevaraya | On the monarch of the Vijayanagara Empire |

| 1979 | Meera | On Mirabai (1502–1556), mystic poet and Krishna devotee |

| 1981 | Kranti | Historical epic on a variety of activists in the independence movement, 1825–1875 |

| 1986 | Tandra Paparayudu | In Telugu, on the seventeenth-century military leader who resisted French colonial expansion |

| 1990 | Tipu Sultan | On the nineteenth-century ruler of Mysore; based on a novel by Bhagwan Gidwani and broadcast on Indian national TV in 1990 |

| 1991 | Chanakya | Hindu-nationalist 47-part epic-historical television drama the ancient political thinker Chanakya (a.k.a. Kauṭilya) |

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Bharati | On the Tamil-language nationalist writer Subramania Bharati (1882–1921) |

| 2001 | Aśoka | On the emperor who ruled most of the Indian subcontinent in the third century BC; also broadcast as a TV miniseries |

| 2005 | Magnal Pandey: The Rising | Celebrating the soldier who sparked the Indian Rising (‘Mutiny’) in 1857 |

| 2006 | Dharti ka Veer Yodha Prithviraj Chauhan | TV serial, see 1959 |

| 2010 | Khelein Hum Jee Jaan Sey | On the 1930 Chittagong armoury raid masterminded by Surya Sen (executed 1933) |

| 2011 | Chandragupta Maurya | TV series, revived in 2018, on the founder of the ancient Maurya empire |

| 2012 | Maharana Pratap | See 1949 |

| 2012 | Krantiveera Sangolli Rayanna | On the military leader executed by the British in 1831; made in Karnataka in the Kannada language |

| 2015 | Rudhramadevi | On the thirteenth-century queen; made in Telangana in the Telugu language; also thematized in a 100-part TV series (2021) |

| 2015 | Bajirao Mastani | On founder of the Maratha Empire, Baji Rao I (1700–1740), and his Muslim concubine; based on a Marathi-language novel by N. S. Inamdar (1972) |

| 2018 | Farzand | On epic warfare during the reign of Shivaji; see 1952, 2019 |

| 2018 | Padmaavat | On Padmavati; see 1963, 1964 |

| 2019 | Fatteshikast | On epic warfare during the reign of Shivaji; see 1952, 2018 |

| 2019 | Queen of Jhansi | See 1953 |

| 2020 | Marakkar: Arabikadalinte Simham | Made in Kerala in the Malayalam language; on the naval defence against Portuguese colonial encroachment |

| 2022 | RRR | On the anticolonial activists Alluri Sitarama Raju (1897–1924) and Komaram Bheem (1901–1940) |

These films from various parts of India celebrate a mix of historical nation-builders (from ancient and more modern periods) and anticolonial activists. Production seems to have stagnated somewhat in the decades 1970–2000 (six noteworthy productions in thirty years). This period was marked by the Congress Party’s decline (first election loss in 1977, the assassinations of Indira and of Rajiv Gandhi in 1984 and 1991). Post-2000, another surge in production occurred: fifteen noteworthy productions in twenty years, culminating in 2022 with the extravaganza RRR, which received worldwide fame through Netflix. In the panoply of glorified national heroes, old monarchs and modern insurgents alike, the post-2000 production was able to pick up from the pre-1970 tradition: there were remakes of the films dedicated to Shivaji, Maharana Pratap Singh, Prithviraj Chauhan and the fighting Queen Lakshmibai of Jhansi.

RRR, for all its intensely Indian, Hindutva content, achieved global fame on a newly burgeoning, transnational video streaming platform; it deserves a brief extra comment. A lavish action-hero extravaganza, the film fictionalizes the imagined interaction between two historical figures, anticolonial activists from the 1920s. A Telugu production (the initials in the title stand for Raudraṁ Raṇaṁ Rudhiraṁ, ‘Rage, War, Blood’), but co-produced by companies from various parts of India, the film focuses on the plight and resistance of the Adivasi tribal communities of Southern India. The film portrays the representatives of British rule as cartoonishly evil; the resistance triumph is almost literally an apotheosis, as one of the heroes takes on the looks and guise of the mythical Rama, hero of the Ramayana epic. The finale celebrates a selection of personalities as a veritable lineage, from various parts of India, in the tradition of anti-British resistance: twentieth-century activists such as Subhas Chandra Bose, Vallabhbhai Patel and Bhagat Singh, and canonical historical figures such as Queen Lakshmibai and Chhatrapati Shivaji. That tableau de la troupe is set to a song-and-dance exhortation to honour the national flag. The flag that is featured visually is the 1907 flag of Indian independence, emblazoned with the long-standing nationalist Vande Mataram mantra/slogan, which is repeatedly chanted in the course of the film.20

The visual spectaculars and song-and-dance interludes are pure Bollywood (stretching that term to include Telugu ‘Tollywood’ and other production hubs in the subcontinent outside Mumbai); and the heroes and historical memories are as homegrown Indian as the Bollywood production style. Even so, I would venture to suggest that RRR is also an example of what Bob van der Linden has termed ‘Romantic nationalism in India’.21 It displays all the hallmarks: linking together a series of activists from different periods and regions into a transcendental lineage asserting une certaine idée de l’Inde (for what is Hindutva other than such an ideal essence of cultural identity?); the invocation of national myth (Rama and the Ramayana) as the ultimate validator of national authenticity; the positioning of culture and its lieux de mémoire as an inspirational and motivating force in the resistance against foreign rule – and doing so, to boot, in a movie that tightly dovetails narrative and spectacle. In all those respects RRR answers to the very definition of Romantic nationalism. It would be simplistic to reduce RRR to ‘the influence of Walter Scott and Jules Michelet’; but it would be equally wrong to deny that influence altogether. The Romantic historicism of Scott and the national idealism of Michelet entered not only into a European circulation of ideas but into a global one, and it reached not only Latvia and Iceland but also the US and India, inflected meanwhile by a multitude of local and global circumstances. Specific to India were the repertoire of a prestigious historical culture native to the subcontinent and a lineage of Indian intellectual and artistic activists with an anticolonial agenda. But inflected and assimilated as it was, the mode of Romantic nationalism forms part, and recognizably so, of the style and substance of such films as RRR. Romantic nationalism after the century of globalization can no longer be studied in European isolation.

Epic Nationalism: Outrage into Charisma

Plotting a timeline of the worldwide production of nationally themed entertainment cinema offers a curve that is highly reminiscent, albeit on a different timescale, to the one illustrating the production of commemorative statues (Figure 12.1): a sudden onset, a mid-twentieth-century dip, and a remarkable resurgence post-1990 (Figure 12.5).

Figure 12.5 Production of films with national-heroic content per decade.

‘Romantic nationalist’ cinema comes in a variety of styles and genres. There are the reverent recyclings of national classics; the historicist celebrations of the lives of national heroes (such as Queen Lakshmibai of Jhansi, or Winston Churchill, or Napoleon); the fictionalized/narrative evocations of critical turning points in the nation’s history (often based on classics in the Walter Scott tradition). There is also a much more ‘unpolitical’ genre, where the nation is unobtrusively present only as a mellow feel-good factor, as in period dramas (Chariots of Fire), royalty glamour (the various Queen Louise iterations) and the rustic-idyllic register (Jean de Florette). And finally, there is the strident genre of the national action-hero movie. That, I would suggest, is the way in which national epic is nowadays presented to mass audiences. In many cases, epic lies at the heart of it: not only through cinematic versions of the Nibelungenlied or Beowulf, but also in that an entire sub-genre is dedicated to Hegelian hero-figures and how they brought the nation into being (Gustav Vasa and Wilhelm Tell) or ensured its survival at a critical juncture (King Stephen of Hungary).

The sheer number of these films post-1989 is overwhelming. From 1991 (yet another Alexander Nevsky version, Russian) to 2020 (yet another thematization of Arminius the Cheruscan in the German Netflix series Barbaren), the total comes to something like seventy-five (excluding almost twenty Indian productions). Many of the post-1989 instances revert to canonical figures already celebrated in earlier thematizations. Between them, they are a heterogeneous lot,Footnote * but all of them exemplify the enduring power of hero-worship almost two centuries after Carlyle. National epics share a small twenty-first-century world, with DVDs marketed through Amazon and streaming services wrapping the globe in a single cloud, pooling the heroic resources of all nations into a single entertainment market.

Small wonder, then, that despite the huge cultural and geographic span of these national epics, there should be a strong stylistic family likeness between all these action movies. A certain global convergence of the format is noticeable, favouring similar production values and marketing strategies for similar products. The posters, for instance, tend to follow a highly standardized iconography. A stern, defiant figure is foregrounded against a stormy sky or scenes of battle, symbolizing both the heroic stature of the protagonist and the crisis in which his (or in some cases her) heroism manifests itself. The hero’s facial expression is aggressively battle-ready to match the occasion.

More importantly, perhaps, similarities can be explained from a common thematic DNA. We can trace these common elements through the focusing lens of Mel Gibson’s Braveheart (1995). Gibson came out of a generation of masculine action stars in a genre that, following Rambo, had already begun to make use of patriotism and family values to motivate and ethically justify their blood-soaked violence. William Wallace, title hero of Braveheart, is marked as a ‘good guy’ by his tender attachment to his fiancée and his happily integrated life in his home community; the rape and murder of that fiancée are what drive him into berserker mode, painting his face blue and inspiring his armies with the roar of ‘Freedom!’ It is in fact a remarkable dramatic transmutation: the cruel depiction of outraged and violated women is transmuted into righteous anger against invading armies, and the spoliation of the home community provokes a nationwide war to cleanse the country as a whole. Private affect is evoked in painful, lingering detail; the horribly evil villains, the heart-rendingly innocent and vulnerable victims and the admirable, outraged heroes are depicted in stark black-and-white contrast. Epic meets melodrama: neither does ‘subtle’, and mixed feelings and moral dilemmas are left to more high-minded genres. Black-and-white contrast is also applied to the happy, harmonious and familial scenes of the homeland community and its hideous disruption by sadistic invaders. The technique of the fête interrompue is frequently applied: scenes of cheerful festivity precede the sudden disaster that interrupts them. The powerful, primary emotions that are depicted are easily empathized with by popcorn-snacking audiences; these passions then trigger and motivate a revenge campaign, in which the private becomes political and the agitated viewer shares the heroes’ anguish and glory.22

All this emotive sound and fury cloaks a political sleight of hand. The communitarian man of the people, even as he takes up the banner of freedom, becomes an authoritarian leader. ‘Freedom’ becomes a battle cry for commanders barking orders and imposing discipline. Moral outrage about individual fates morphs into a territorial strategy about a fatherland. The innocent victims may or may not be individually avenged on the actual perpetrators, but the anger at their fate serves to invest their self-appointed avenger with the authority of righteousness and the power to command his followers in the territorial crusade to cleanse the country. Outrage is transfigured into charisma.

That rhetoric is not exclusively cinematic, of course; readers will have no trouble thinking of examples from populist politics. And Braveheart did not invent it – we can find the tropes already in the epic followers of Walter Scott, such as Sienkiewicz and Conscience, and in early epic films such as The Birth of a Nation and Alexander Nevsky. In the former, liberated slaves (played by actors in blackface) chase and rape terrified young women (white, of course); in the latter, morose Teutonic Knights ritually throw toddlers into a fire. The screams of the innocent are transmuted into roars of vengeance: raised by the Ku Klux Klan in Griffiths’s film, by the title hero in Eisenstein’s (liberating Russkaya Zemlya, the Russian Land). Braveheart’s rousing call to ‘Freedom!’ segues into a roared Alba gu bragh (‘Scotland for ever’).

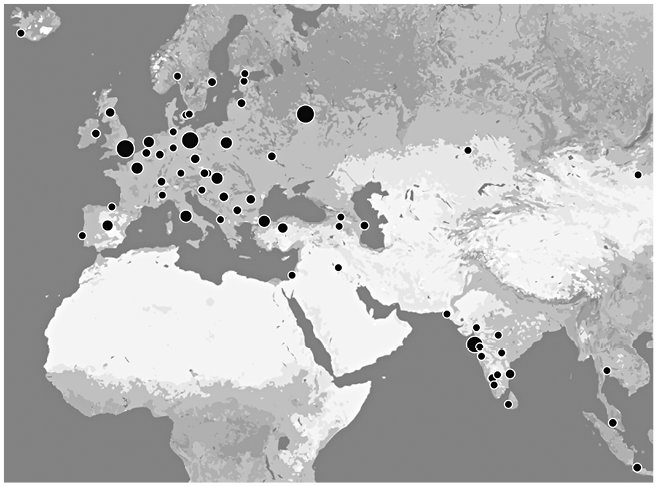

The dramatic scheme is crude (as it is in epic by nature) but effective, and post-Braveheart it is applied again and again in the national action movie. The ERNiE checklist gives close to 100 titles post-1990 answering to this description, with a worldwide distribution concentrated in Britain, Russia and India and in a forked belt reaching from Turkey to the Baltic (Figure 12.6).

Figure 12.6 Eurasian geographic distribution by production location of 100 epic-heroic national action movies since 1990.

Like statues, such films are expensive to produce but cheap to get access to; in their distribution they are as ‘unrestricted’ as postage stamps or banknotes (to recall Bourdieu’s terms as discussed in the Introduction). On the whole, they target not art-houses but large audiences seeking entertainment, and they rely on a commercial investment-and-return model rather than on cultural subsidies.

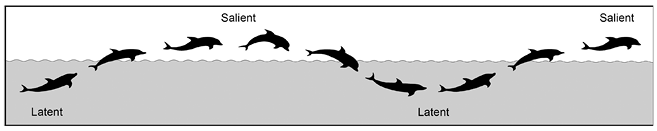

All this turns commercial mass-entertainment cinema into a congenial habitat for popularized nationalism. In noticing the worldwide prevalence of nationalism in the twenty-first century, it is impossible not to take account of this widespread, sustained and deeply penetrative cinematic presence. These films are not in themselves remarkable – they do not often figure in the film festivals and awards presentations; outside their country of origin they are often marketed direct-to-DVD or by streaming services, and their cultural presence is unobtrusive. That unobtrusiveness has been described as ‘banal’ by Michael Billig. Such terms have been used across the pages of this book to hint at that unobtrusiveness of nationalism: diffuse, unpolitical, latent. It is now time to focus more sharply on this aspect.

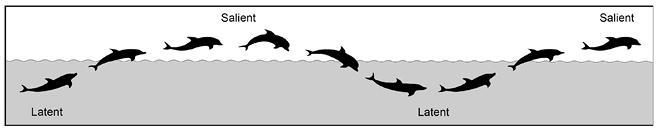

Diffusion Condensed