Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective and relatively safe form of treatment for severe psychiatric states, including major depression, mania and schizophrenia. ECT has become a safe procedure due to advancements in technology and improvements in anaesthesia. Despite a strong evidence base, it is the most controversial form of medical treatment in the field of medicine. Reference Gazdag and Ungvari1 The practice and standards of ECT vary widely across countries, with regional variations found even within a single country. Reference Leiknes, Schweder and Høie2

Nepal is a low- and middle-income country (LMIC) in South Asia. The first psychiatric out-patient service started at Bir Hospital, Kathmandu, in 1961. Nepal’s only mental hospital was established in 1984, marking a significant milestone in the country’s mental health history. Reference Rai, Gurung and Gautam3 In Nepal, ECT is used as a primary option rather than a last resort. Reference Upadhyaya and Joshi4 However, comprehensive data are lacking regarding the number of facilities offering ECT or the number of treatments performed annually. The use of unmodified ECT has been a topic of controversy in Nepal due to serious ethical concerns, despite its life-saving potential in certain circumstances. Reference Upadhyaya and Joshi4 Resource limitations in the past have led several institutions to administer unmodified ECT; however, this has gradually been replaced by modified ECT as the preferred treatment. Reference Upadhyaya and Joshi4,Reference Upadhyaya5

There are no national guidelines for administration of ECT in Nepal, and therefore a pressing need exists to understand current practices of ECT in the country. We conducted a nationwide survey using a comprehensive, 33-item questionnaire to fill this existing knowledge gap. The primary objective of this study is a thorough evaluation of the characteristics of ECT practice in Nepal. We also aim to comprehensively explore the availability of ECT in psychiatric services and determine the highest standards and most effective techniques of ECT practice. Our study provides an extensive overview of ECT services in Nepal, informing the further development of ECT services and policy in the country. The potential impact of our findings on shaping the future of ECT in Nepal is significant and promising, offering hope for improved psychiatric treatment practices.

Method

This was a cross-sectional and descriptive study (quantitative study) conducted via online survey. Ethical approval was obtained from Nepal Health Research Council (reference no. 2352). We identified and compiled a list of all hospitals and medical colleges offering in-patient psychiatric services following consultation with the Psychiatrists’ Association of Nepal (PAN) and discussion among the authors. We then established telephone contact with a psychiatrist to obtain consent for participation, and emailed the questionnaire to only those who had consented to participate. Data were collected online using Google Forms with a URL link. Only one response from each site was considered, and we requested that participants not forward the questionnaire to anyone else to prevent snowballing, which can affect sample representativeness. Personalised email reminders were sent fortnightly, with a maximum of two reminders, to enhance response rates. The survey takes approximately 20 min to complete. We took written informed consent via the Google form. The questionnaire was developed based on existing literature Reference Tor, Gálvez, Ang, Fam, Chan and Tan6 and the consensus of all authors. The questionnaire focused on governance, pre-ECT work-up, prescription and application, and ECT practice standards and techniques.

Results

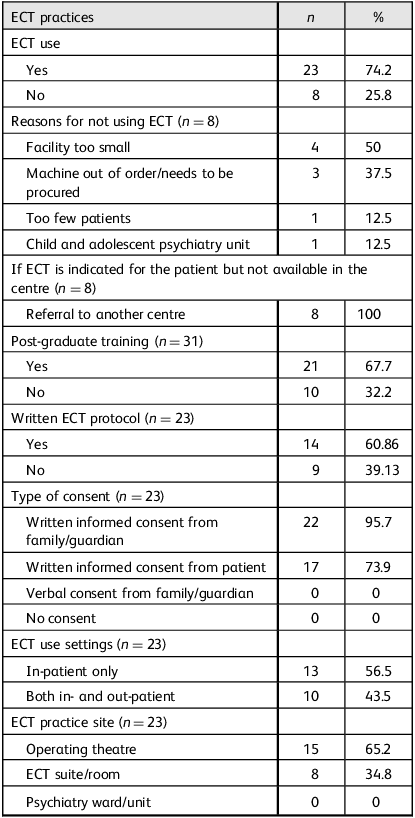

A total of 31 centres completed the survey, with a response rate of 96.9%. Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2025.10080 provide a summary of the results. The majority of centres (23, 74.2%) used ECT, indicating its widespread use as a psychiatric treatment option. Pre-ECT evaluations were found to be a routine part of clinical practice. Twenty-two centres reported the use of pre-ECT monitoring scales, most frequently the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (54.5%). Only half of the centres reported cognitive assessments to monitor the cognitive side-effects of ECT, predominantly using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). The brief-pulse ECT device was the main type of ECT machine and bitemporal placement was the most frequently applied tenchnique in Nepal. Only one centre reported electroencephalographic (EEG) monitoring of seizures, while more than two-thirds assessed motor seizures through the cuff method. Nevertheless, a third of centres reported the continuing practice of unmodified ECT. The most common diagnostic indications were catatonia (95.7%), schizophrenia (82.6%) and depression (73.9%). The clinical indication for ECT use was either medication failure (87%) or in high-risk situations.

Table 1 Institutional characteristics and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) practices

Discussion

Response rate and ECT use

A total of 31 out of 32 centres responded, denoting a response rate of 96.87%. The findings of this survey provide valuable insight into the current state of ECT practices across psychiatric hospitals in Nepal. There were no ECT services offered in about a quarter of the centres surveyed (n = 8), mainly due to small facility size, equipment issues and the low number of eligible patients. These constraints are also reported in other LMICs and include logistics, finance and infrastructure, which often hinder the consistent delivery of ECT services. Reference Andrade, Shah and Tharyan7,Reference Kellner, Knapp, Husain, Rasmussen, Sampson and Cullum8 These findings underscore the ongoing need for targeted investment in psychiatric infrastructure and training to ensure comprehensive coverage of ECT services across Nepal.

ECT protocol and consent

There are no national guidelines or protocols for the standard use and uniform practice of ECT; instead, a practical approach is employed based on the context of resource constraints. Reference Subedi, Aich and Sharma9 Among the countries of South Asia, only India and Pakistan have laws that govern ECT practice, while ECT practice guidelines are available only in India. Reference Menon, Kar, Gupta, Baminiwatta, Mustafa and Sharma10 Written protocols for ECT administration were available in 14 (60.86%) centres, while the remaining 9 (39.13%) lacked such protocols, probably reflecting the absence of standardised national guidelines for ECT practices. Despite the lack of formal protocols, it is encouraging that 95.7% of centres obtained written informed consent from family members or guardians before administering ECT. However, there is no mental health legislation in Nepal and no legal framework, particularly for those patients who are unwilling or unable to consent to ECT. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance – and there is an urgent need – to develop national clinical practice guidelines under the initiative of professional organisations such as PAN, to address these pertinent issues and safeguard the vulnerable population.

Pre-ECT work-up, monitoring scales and diagnostic indication

In the context of Nepal, comprehensive studies focusing on pre-ECT evaluations and assessments are limited. The existing literature primarily emphasises the effectiveness of ECT in treating various psychiatric conditions, rather than detailing procedural practices. In our study, 95.7% of centres offering ECT reported routinely performing pre-ECT assessments, with 87% conducting blood tests, 78.3% performing ECGs and 69.6% ordering chest X-rays. While earlier studies have noted that some form of investigation is typically conducted before ECT, they have not specified which tests are commonly used. Reference Subedi, Aich and Sharma9,Reference Ahikari, Pradhan, Sharma, Shrestha, Shrestha and Tabedar11,Reference Neupane, Pahari, Lamichhane and Thapa12

In this study, the most commonly used pre-ECT monitoring scale was YMRS, by 54.5% of centres. Other scales used include the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), each used in 45.5% of centres, while 36.4% used the Beck Depression Inventory. Assessments conducted before and after ECT treatment sessions help clinicians measure its effectiveness for various psychiatric disorders. The frequent use of YMRS is surprising, considering that mania is not among the most common diagnostic indications for ECT in Nepal. This finding may be attributed to limitations in our study design, particularly respondent bias and issues with the questionnaire format. Specifically, the questionnaire section on pre-ECT monitoring scales did not include an ‘other’ option, which may have restricted participants from reporting alternative assessments such as scales for catatonia, despite this being one of the most common diagnostic indications for ECT. Almost half of centres (43.5%) performed cognitive assessments to monitor the cognitive side-effects of ECT, with MMSE being the most common tool. However, it is essential to note that there are no cognitive assessment tools available in the Nepali language, nor have they been validated in the Nepali population. This lack of tools underscores the need for the development and validation of Nepali-specific cognitive assessment tools for ECT monitoring.

The most commonly reported diagnostic indications for ECT included catatonia (95.7%), schizophrenia (82.6%), unipolar depression (73.9%) and bipolar depression (65.2%). Previous studies from Nepal have identified schizophrenia as the primary indication for ECT, followed by depression and mania. Reference Subedi, Aich and Sharma9,Reference Ahikari, Pradhan, Sharma, Shrestha, Shrestha and Tabedar11–Reference Pant, Upadhyaya, Ojha, Chapagai, Tulachan and Dhungana13 This intriguing shift can be attributed to an increase in awareness and knowledge among ECT prescribers. This finding also remains consistent with the broader trend observed in Western clinical settings, where ECT is primarily used for mood disorders such as major depression and bipolar disorder, with catatonia also recognised as a key indication. 14 In addition to that, the NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance on the Use of Electroconvulsive Therapy (TA59; NICE, 2009) 15 states that ‘The current state of the evidence does not allow the general use of ECT in the management of schizophrenia to be recommended’. However, there is an increasing evidence base for use of ECT in treatment-resistant schizophrenia following the failure of multiple antipsychotic trials. Reference Tharyan and Adams16,Reference Prudic, Olfson, Marcus, Fuller and Sackeim17

Type of ECT and electrode placement

In our study, modified bitemporal ECT, delivered using brief-pulse devices, was most commonly offered across centres. This finding aligns with the review by Menon et al on ECT in South Asia. Reference Menon, Kar, Gupta, Baminiwatta, Mustafa and Sharma10 Although some studies suggest that the use of bifrontal electrode placement is effective, as such it causes fewer cognitive side-effects, Reference Hekmatara, Ghorishizadeh and Amiri18 bitemporal electrode placement has been shown to result in a more rapid decrease in symptom severity. Reference Kellner, Knapp, Husain, Rasmussen, Sampson and Cullum8 This is particularly significant in a country like Nepal, where the majority of the population has a lower socioeconomic status and faces out-of-pocket mental health care expenses. There is thus a need for rapid response and effective treatment without imposing a significant financial burden on patients and their families.

Our study revealed that 69.6% of the centres administer modified ECT, while only 13% offer unmodified ECT and 17.4% provide both. The use of modified ECT is on a clear upward trend in current practice, accelerated by the expansion of psychiatric services, availability of specialists and the development of the necessary infrastructure for administering ECT with appropriate patient monitoring. This shift signifies a positive future trend for ECT administration in Nepal. Furthermore, modified ECT has been shown to have a higher margin of safety profile, with fewer musculoskeletal complications and less vigorous convulsions. Reference Narayan and Deepanshu19

The practice of unmodified ECT is not legally prohibited in Nepal, and its administration continues in about a third of its centres. Two respondents indicated that unmodified ECT is safer than modified ECT, reflecting a common misconception; in general, modified ECT is a safer procedure than unmodified ECT. Reference Andrade, Shah and Tharyan7 The risk of physical injury, such as muscle, bone and tooth injury associated with unmodified ECT, outweighs the minimal risk of anaesthesia, Reference Andrade, Shah and Tharyan7 underscoring the need for continued education, identify knowledge gaps and training among Nepalese psychiatrists. This practice of unmodified ECT can be attributed to limited resources and a lack of anaesthetic support. It is indisputable that unmodified ECT is a suboptimal treatment option in contemporary psychiatric practice. However, in resource-constrained settings such as Nepal, this practice is preferable to no intervention at all. Reference Andrade, Shah and Tharyan7 Furthermore, the absence of specific laws related to ECT in Nepal highlights the urgent need for legal considerations in ECT administration, particularly in areas such as capacity and consent, as well as involuntary ECT administration. However, there has been a gradual shift toward modified ECT as infrastructure and anesthesiology services become more generally available. Reference Menon, Kar, Gupta, Baminiwatta, Mustafa and Sharma10

Anaesthetic agents

We found that propofol, followed by ketamine and thiopental sodium, were preferred for anaesthetic induction, while succinylcholine as a muscle relaxant was the choice in all centres. This is similar to findings from other studies. Reference Menon, Kar, Gupta, Baminiwatta, Mustafa and Sharma10,Reference Neupane, Pahari, Lamichhane and Thapa12 Although methohexitol is regarded as gold standard as an induction agent, Reference Salik and Marwaha20 this was found to be used at only a single centre, which might be due to its availability and to the use of ketamine as an anaesthetic induction agent, which can have added benefits, particularly in patients with depressive disorders, owing to its antisuicidal and antidepressive properties. Reference Andrade21

Seizure monitoring, ECT population and frequency

In our study, EEG monitoring of seizures was found to be rare (4%; i.e. used in only one centre). Instead, seizure monitoring during ECT was primarily conducted through the cuff technique in 16 centres, and observation of visible generalised motor seizures was practiced in 12. This practice aligns with reports from neighbouring countries, where similar methods are commonly employed. Reference Menon, Kar, Gupta, Baminiwatta, Mustafa and Sharma10

Our study showed that two-thirds (72.2%) of centres administered ECT to pregnant women and elderly patients. One study, conducted in a teaching hospital in Kathmandu, Reference Neupane, Pahari, Lamichhane and Thapa12 found that ECT administered to pregnant women had no adverse outcomes in regard to both maternal and fetal outcome; similarly, an elderly population with comorbid conditions, including hypertension, stroke or other neurological conditions, could safely have ECT administered.

Administration of ECT three times per week was noted in 69.6% of centres. More than half (56.5%, n = 13) of the centres conducted between 6 and 9 ECT sessions; maintenance ECT was practised in nearly half (47.8%, n = 11) of centres. It is encouraging to note that maintenance ECT is being practiced, because previous studies have demonstrated that continuation and maintenance ECT appears effective in reducing the severity of illness and shortens hospital stays. Reference Sombatcharoen-Non, Yamnim, Jullagate and Ittasakul22

The nationwide survey reveals that ECT is widely used across psychiatric centers in Nepal, predominantly as modified bitemporal ECT with standardised pre-ECT evaluations. Despite the absence of national guidelines, many centers follow written protocols; however, several still use unmodified ECT due to limited resources and lack of anaesthetic support.

Key recommendations, particularly relevant for LMICs, include the following: (a) establishing national ECT guidelines to ensure standardised and safe practices; (b) investing in infrastructure and securing anaesthesiology support to phase out unmodified ECT; and (c) promoting standardised, safe and evidence-based ECT practices across all treatment centres.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several limitations. Being an online survey, both selection bias and respondent bias are common. Data were reported by psychiatrists, which may have been influenced by recall and social desirability biases. Second, only hospitals providing in-patient psychiatric services were included, potentially overlooking smaller private clinics or centres that might also provide ECT. Third, the study focused on service characteristics rather than patient-level outcomes, limiting the ability to assess the effectiveness and safety of ECT practices.

Despite the above limitations, the study has notable strengths. It achieved a high response rate of 96.9%, a nationwide scope that provides a comprehensive and representative overview of ECT practices in Nepal. This is the first national-level survey in Nepal to document ECT standards and procedures, filling a critical knowledge gap to guide future policy and training efforts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2025.10080

Data availability

The anonymised data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data will be shared in accordance with institutional and ethical guidelines, and are subject to approval from the Nepal Health Research Council, ensuring that the confidentiality and privacy of participating centres are maintained.

Author contributions

U.K., D.B. and Y.R. designed and conceptualised the study. U.K. and A.A. prepared the initial manuscript and were involved in data acquisition. U.K., D.B. and Y.R. contributed to data analysis and statistical analysis. U.K., A.A., D.B. and Y.R. contributed to intellectual content, literature search, manuscript editing and manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive a specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.