“Godlike Erect”

In their seminal work Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson identify a type of metaphor that has “to do with spatial orientation: up-down, in-out, front-back, on-off, deep-shallow, central-peripheral.” Orientational metaphors, as Lakoff and Johnson call them, “give a concept a spatial orientation; for example, HAPPY IS UP.” They “arise from the fact that we have bodies of the sort we have and that they function as they do in our physical environment.”Footnote 1 One of the most fundamental orientational metaphors in Western culture gives the concepts of human and animal a spatial orientation: human is up; animal is down. This orientational metaphor derives from a certain understanding of the physical difference between humans and animals: namely, that upright posture allows humans to direct their gaze up and so contemplate heaven. A theological commonplace of Western thought, traceable to Plato, is that erect posture distinguishes humans from other creatures. The Roman poet Ovid writes in Book I of the Metamorphoses, “Whereas other animals hang their heads and look at the ground, [the Creator] made man stand erect, bidding him look up to heaven, and lift his head to the stars.”Footnote 2 The English poet John Donne echoes this thought in his 1624 text Devotions upon Emergent Occasions: “We attribute but one privilege and advantage to man’s body above other moving creatures, that he is not, as others, grovelling, but of an erect, of an upright, form naturally built and disposed to the contemplation of heaven.”Footnote 3

In the Christian tradition to which Donne belongs, upright posture is “foremost among the physical characteristics claimed as aspects of imago Dei.”Footnote 4 When John Milton introduces Adam and Eve in his poem Paradise Lost, he describes them as “Godlike erect” in relation to the other animals.

Notice how Milton here connects vertical orientation with majesty. He sees upright posture not merely as distinguishing human from animal but also as empowering human over animal. The first humans seem lords of all they survey because they stand erect with their faces toward heaven.

In the Western tradition, the problem of the relation between human and animal is, in some sense, a problem of posture. An extraordinary episode in the biblical Book of Daniel makes this point by telling of how the proud Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar loses his upright posture for failing to acknowledge the sovereignty of Heaven. When walking on the roof of the royal palace of Babylon one day, Nebuchadnezzar boasts: “Is not this the great Babylon I have built as the royal residence, by my mighty power and for the glory of my majesty?” God punishes the great king most severely for this act of hubris: “He was driven away from people and ate grass like cattle. His body was drenched with the dew of heaven until his hair grew like the feathers of an eagle and his nails like the claws of a bird.” Nebuchadnezzar remains in this bestial state, eating grass on all fours like cattle, for seven years. He only returns to his true human form in the story when he raises his eyes toward heaven and praises God: “At the end of that time, I, Nebuchadnezzar, raised my eyes toward heaven, and my sanity was restored. Then I praised the Most High; I honored and glorified him who lives forever.”Footnote 6

Nebuchadnezzar is made to lead an animal-like existence because he fails to orient himself upward toward God. Instead of acknowledging the sovereignty of heaven, he attributes the might and glory of Babylon to himself. God punishes this arrogance by physically reorienting the proud king toward the earth. Nebuchadnezzar falls from grace by literally falling onto his hands and knees. No longer upright, he is turned away not just from the human community but also from God. Nebuchadnezzar rectifies the situation by looking up – that is, by changing his physical orientation from downward to upward. Through the act of looking up and praising God, he recovers his sanity, his upright posture and thus, finally, his humanity.

The idea that uprightness and vertical orientation define the human is not bound by the religious tradition in which it arises and continues to find expression in modern philosophical and anthropological discourse. Immanuel Kant writes in the conclusion of his Critique of Practical Reason of how the “starry heavens above” fill the mind “with ever new and increasing admiration and reverence.” The act of looking up at the heavens, Kant continues, has the effect of annihilating, “as it were, my importance as an animal creature.”Footnote 7 “In the theater of modern philosophy,” the Italian philosopher Adriana Cavarero writes in her recent book Inclinations: A Critique of Rectitude:

center stage is occupied by an I whose position is straight and vertical. Words like righteousness and rectitude, which occur frequently in dictionaries of morals, and were often used already in the Middle Ages for the “rectification” of bad inclinations, are an important anticipation of this scenario. The “upright man” of which the tradition speaks, more than an abused metaphor, is literally a subject who conforms to a vertical axis, which in turn functions as a principle and norm for its ethical posture. One can thus understand why philosophers see inclination as a perpetual source of apprehension, which is renewed in each epoch, and which takes on even more weight during modernity, when the free and autonomous self celebrated by Kant enters the scene.Footnote 8

Cavarero makes two important points here. First, we connect the notion of morality with vertical posture and orientation. We use vertical metaphors to describe those who we see as conforming to societal norms – we speak, for example, of upright citizens or of upstanding members of society. The English word rectitude, meaning “[c]onformity to accepted standards of morality in behaviour or thinking,” derives in part from the post-classical Latin rectitudo, meaning “uprightness of posture.”Footnote 9 Second, verticality is gendered male. While we traditionally associate inclination – the shift away from the vertical axis toward the horizontal axis – with femininity, we associate verticality with masculinity.

The figure of the “upright man” remains central to philosophical and anthropological accounts of the human in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Sigmund Freud speculates in an often-cited footnote to his 1930 work Civilization and Its Discontents that “[t]he fateful process of civilization … would have been marked by man’s adopting of an erect posture.”Footnote 10 For Freud, the shift from quadrupedalism to bipedalism had a civilizing effect in causing the eye to replace the nose as the dominant organ of human perception. Humans began to feel shame, he reasons, when their genitals, which were previously concealed, became visible to them and in need of protection. According to the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard in his 1943 book Air and Dreams: “The positive dimension of verticality is so clear that we can formulate this aphorism: what does not rise, falls. Man qua man cannot live horizontally.”Footnote 11 In a similar vein, the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk (who is familiar with Bachelard’s text) remarks in a 2001 interview with Hans-Jürgen Heinrichs: “humans as users of lungs are air dependent; like all higher animals, they use oxygen as a metabolic drug, bringing them a high potential for ecstasy. … We thus bear already within ourselves, biologically, a dimension of elation, which is not perceived by existing schools of anthropology.” It is not possible, Sloterdijk tells Heinrichs, “to understand the human fact through down-to-earthness.”Footnote 12

But what if we were to challenge this conventional wisdom and think of the human not in terms of rectitude and verticality but rather through inclination and down-to-earthness? What if we were to seek the essence of the human not in the act of looking up at the starry heavens but rather in the act of looking down at the ground? In this book, I claim that the literary genre of the animal fable portrays the human in terms of down-to-earthness. The fable, I suggest, challenges the theological notion that the human subject expresses itself most truly in the act of looking up. Rather than orienting us up to the heavens, fables orient us down to the earth and its animal inhabitants. They do so by transforming humans into animals. “What would fable be without metamorphoses?” the French philosopher Michel Serres writes in his 1980 study The Parasite. “Men must be changed into animals with a wave of the magic wand. And how can that be? The secret of the fable is metamorphosis in the fable.”Footnote 13 According to Serres, the fable, like the fairy tale, depends on the idea of the metamorphosis of the body. As we saw in the story of Nebuchadnezzar, to be turned into an animal is to be turned away from the human community and from the divine. Whereas Nebuchadnezzar’s transformation is temporary, a sign of his spiritual madness, reversible through an act of theological penitence, the fable asks us to contemplate a more permanent and thus troubling transformation of human into animal.

Consider the famous example of Jean de La Fontaine’s 1690 fable “The Companions of Ulysses,” which reworks an episode from Homer’s Odyssey. Serres writes in Variations on the Body: “Fables, stories in which all living things give signs, teach profound things. La Fontaine began his last book with ‘The Companions of Ulysses’; metamorphosed into animals, these companions decline to become human again, confessing thereby that they have finally found their definitive point of equilibrium, their true character, their fundamental passion.”Footnote 14 In La Fontaine’s fable, the goddess Circe tricks Ulysses’ crew into drinking a delicious but baneful potion that transforms the men into various four-legged animals. Ever-resourceful Ulysses then charms Circe and makes her provide him with the remedy to the poison. In the Odyssey, Ulysses’ companions, who have all been turned into swine, allow Circe to transform them back into men. In La Fontaine’s fable, by contrast, the companions reject Ulysses’ offer of a remedy, claiming they are now happier in their newfound forms. Not only are they content to remain as nonhuman animals, but they also proceed to criticize the human from the perspective of their new species. The wolf, for example, draws a lesson from Plotinus and says: “Why, man, not seldom, kills his very brother; / What, then, are you but wolves to one another?”Footnote 15

Nebuchadnezzar stops being an animal when he recovers his sanity and realizes that to be human is to look up at the heavens and praise God. His is ultimately a story about the overcoming of the animal by the theological subject that stands “Godlike erect.” In “The Companions of Ulysses,” the crewmembers refuse to transform back into humans or readopt their upright posture and orientation. Their preference for animal over human form, four legs over two, enables them to criticize aspects of human society from below, so to speak. As Frank Palmeri notes:

It is true that in the moral that follows this fable, addressed to Louis XIV’s grandson, La Fontaine cites Ulysses’ crewmen as negative models, to be condemned and avoided because they chose to enslave themselves to their passions. However, the explicit, conventional judgment of the moral does not outweigh or negate the sharp challenge to human superiority in the narrative of the fable. The required expression of respect by the seventy-year-old poet for the eleven-year-old prince, like Ulysses’ expectation that his crewmen will defer to their king and captain, illustrates the constraints and artificial inequalities in human society to which the animals refuse to return.Footnote 16

Indeed, the contradiction between the fable’s narrative and moral only further accentuates the incompatibility of the human and animal perspectives.

For most readers, fables have little to do with real animals or with what we might call “the animal perspective.” According to Samuel Johnson in his Life of Gay, a fable “seems to be, in its genuine state, a narrative in which beings irrational, and sometimes inanimate, are, for the purpose of moral instruction, feigned to act and speak with human interests and passions.”Footnote 17 Likewise, for Thomas Noel, a fable is “a pithy narrative using animals to act out human foibles and a consequent moral, either explicit or implicit.”Footnote 18 In these definitions, rather than representing themselves, the animals in fables are subject to the allegorical tutelage of humans. This leads French philosopher Jacques Derrida in The Animal That Therefore I Am to censure the entire genre: “We know the history of fabulization and how it remains an anthropomorphic taming, a moralizing subjection, a domestication. Always a discourse of man, on man, indeed on the animality of man, but for and in man.”Footnote 19 But in Animal Fables after Darwin I argue against this critical commonplace that the anthropomorphized animals in fables are ciphers for purely human dramas. La Fontaine’s “The Companions of Ulysses” helps us to see how the form of the fable uses the transformation of human into animal to play with the vertical order of things and to imagine the difference between a human and a nonhuman perspective. Making the fable a subversive and ultimately antitheological literary genre, I suggest, is the fact that it unsettles the orientational metaphor that we have seen is fundamental to Western thought: “human is up; animal is down.” Ulysses expects his companions – now become lion, bear, wolf, elephant, and mole – to give up the “shame and pain”Footnote 20 of being animal and become human again. But the form of the fable exists precisely to disappoint this anthropocentric assumption that the human is the highest animal.

French novelist Marie Darrieussecq’s 1996 international bestseller Pig Tales: A Novel of Lust and Transformation provides a kind of updated, post-Darwinian version of “The Companions of Ulysses.” Pig Tales is told from the point of view of a woman who has gradually transformed into a sow. The novel’s unnamed first-person narrator resembles Ulysses’ companions in La Fontaine’s fable in that she comes to accept and even revel in her new physical form. She writes at the end of her narrative:

Now I’m a sow most of the time. It’s more convenient for life in the forest. I’ve taken up with a very handsome, very virile wild boar. … I’m not unhappy with my lot. The food’s good, the clearing comfortable, the young wild boars are entertaining. I often relax and enjoy myself. There’s nothing better than warm earth around you when you wake up in the morning, the smell of your own body mingling with the odour of humus, the first mouthfuls you take without even getting up, gobbling acorns, chestnuts, everything that has rolled down into the wallow while you were scrabbling in your dreams.Footnote 21

Darrieussecq’s porcine narrator critiques human behavior and standards by finding pleasure in the earthy grotesquerie of her newfound animal experience. As Mark Payne notes, “the pig derives its special authority from the pleasure it takes in substances human beings find repulsive, so that its pleasure interrogates the human delights with which it is analogous.”Footnote 22

“Four legs good, two legs bad!”Footnote 23 George Orwell’s famous formula in Animal Farm, another pig tale, encapsulates the fable’s critical attitude toward vertical or upright posture. Orwell’s 1945 novella, which was originally subtitled “A Fairy Story,” literally concerns the problem of vertical power relations: the exploitation of the four-legged by the two-legged. It makes this point in the opposite way to “The Companions of Ulysses”: by showing exploited animals turning into exploitative humans. In one of the most dramatic moments in the text, the pigs on Animal Farm adopt human bipedalism to signal their transformation into the exploiters of other animals:

Startled, the animals stopped in their tracks. … [O]ut from the door of the farmhouse came a long file of pigs, all walking on their hind legs. Some did it better than others, one or two were even a trifle unsteady and looked as though they would have liked the support of a stick, but every one of them made his way right round the yard successfully. And finally there was a tremendous baying of dogs and a shrill crowing from the black cockerel, and out came Napoleon himself, majestically upright, casting haughty glances from side to side, and with his dogs gambolling round him. He carried a whip in his trotter.Footnote 24

Napoleon emerges from the farmhouse, as Adam and Eve first emerge in Paradise Lost, “majestically upright” or “Godlike erect.” He is seemingly lord of all he surveys. (At the end of the novel, he will propose abolishing the name Animal Farm and returning to the original name of The Manor Farm.) Through their upright posture the pigs on Animal Farm assert their sovereignty, their majesty, their anthropomorphic grandeur. Where Orwell’s text shows itself to be a fable, I suggest, is in connecting the hypocrisy and corruption of the pigs to their fabulous anthropomorphization. This process is made complete in the final paragraph of the text when it becomes impossible for the curious animals looking into the dining room of the farm house, where the pigs are entertaining a deputation of neighbouring farmers, to tell the human guests apart from their animal hosts: “Twelve voices were shouting in anger, and they were all alike. No question, now, what had happened to the faces of the pigs. The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.”Footnote 25

“Going the Whole Orang”: The Post-Darwinian Fable

“We have to unpack the symbol of height,” the English philosopher Mary Midgley avers in her book Beast and Man. “And to do this, we have to see how it has become entangled in the notion of evolution.”Footnote 26 In his recent study on the evolution of visual metaphors for biological order, J. David Archibald demonstrates the persistence of height metaphors in popular representations of evolutionary theory. “One need not be a biologist to understand the meaning of ‘lower’ and ‘higher’ animals,” Archibald writes. “Images abound showing the march of primate evolution from the lowly, monkey-like ancestor to the pinnacle of humanness – Homo sapiens. We do, of course, deem ourselves as the highest animals – in the Western tradition, just below the angels.” Archibald here alludes to the idea of the great chain of being, a Christianization of Aristotle’s scala naturae or scale of nature, that organizes nature into a static vertical order rising from inanimate matter at the bottom to plants, animals, humans, angels, and finally, God at the top. The great chain of being is one of the most elaborate height metaphors in Western thought. It ranks all the forms of life according to their relative distance from God – or the Most High, as he is sometimes called in the Hebrew Bible. Archibald’s point is that evolutionary theory figures in the popular imagination as another scala naturae: “The scala naturae continues to the present day in any number of guises. While not inhabiting any serious works intending to elucidate evolutionary relationships, it is alive and well in advertising and satirical humor, usually portraying a progressive march of fish coming onto land, or a march of ape-like creatures to humans.”Footnote 27

Something that indicates how the symbol of height has become entangled in the notion of evolution is the sense of disgust we often feel toward so-called lower forms of life. We express this sense of disgust when we denigrate other people by calling them by the names of other animals: dog, snake, rat, pig, cat, weasel, cow, to mention just a few. We most commonly make women the victims of these metaphors of animalization. Darrieussecq reports being frequently asked about why she chose the figure of a sow in Pig Tales: “I haven’t really a reply,” she writes, “except statistically. We treat women as sow more often than mare, cow, monkey, viper, or tigress: more often still than as giraffe, leech, slug, octopus, or tarantula; and far more often than as a centipede, female rhino, or koala. It’s simple.”Footnote 28

In his philosophical fable Vampyroteuthis Infernalis, the Czech-born philosopher Vilém Flusser speculates that humans have incorporated into their collective unconscious “a hierarchy of disgust that reflects a biological hierarchy.” We find something increasingly more disgusting, Flusser thinks, the further removed it is from us on the phylogenetic tree: “Most disgusting of all are mollusks, ‘soft worms.’ Somewhat less disgusting are the most primitive chordates (Acrania), worms whose backs are supported by a cuticular fin. … Similarly, the chimpanzee disgusts us because it deviated from us at the last moment, just as we began our path from primate to human.” Flusser’s point here is that our biological criteria are anthropocentric. In seeing ourselves as made in the image of God or as “Godlike erect,” we make the human form nature’s endpoint. “As far as we are concerned, life – the slimy flood that envelops the earth (the ‘biosphere’) – is a stream that leads to us: We are its goal.”Footnote 29

The authors I examine in Animal Fables after Darwin produce animal fables that critique human verticality and rectitude by playing with this idea of a “hierarchy of disgust that reflects a biological hierarchy.” The name I give to this post-Darwinian type of fable is theological grotesque. I take this term from H. G. Wells, who uses it to describe his 1896 novel The Island of Doctor Moreau. Wells writes of Moreau in the preface to the 1924 Atlantic edition of the text:

It is a theological grotesque, and the influence of [Jonathan] Swift is very apparent in it. … This story was the response of an imaginative mind to the reminder that humanity is but animal rough-hewn to a reasonable shape and in perpetual conflict between instinct and injunction [morality]. … It was just written to give the utmost possible vividness to that conception of men as hewn and confused and tormented beasts.Footnote 30

As I understand it, the theological grotesque works by inverting the scala naturae or divine order of things, that is, by redescribing notions belonging to the upper dimension of the vertical vector such as the divine, the spiritual, and the rational in terms of notions belonging to the lower dimension of the vertical vector such as the animal, the physical, and the irrational. The Island of Doctor Moreau is a theological grotesque in the sense that it figures God as a cruel and remorseless vivisectionist and humans as confused and tormented beasts. The mad scientific experiment Moreau conducts on his remote Pacific island laboratory is to render nonhuman animals “Godlike erect” through a process of grotesque anthropomorphization. Moreau’s Beast Folk have been vivisected so that they walk upright and speak like humans. They have also internalized the idea of human verticality as a kind of divine law. “Not to go on all-fours; that is the Law,” they chant. “Are we not Men?” (IDM 114, original emphasis). But the effect of this grotesque mimicry of the human is to empty the concept of verticality of its significance. As a sign of the failure of Moreau’s experiments, the Beast People abandon bipedalism at the end of the novel and reorient themselves once more toward the ground. The theological grotesquerie of Wells’ novel flattens the vertical order of things, so that the human becomes associated with bestial confusion rather than divine rationality.

Disgust is one of the key affects expressed in Moreau. As a traumatic aftereffect of his encounter with the Beast Folk, the novel’s main first-person narrator, Edward Prendick, remains unable on returning home to England to reestablish his previous sense of the vertical order of things. Like his literary forebear, Lemuel Gulliver, returning home from the land of the Houyhnhnms in Swift’s 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels, Prendick now finds himself repulsed by his fellow humans. What disturbs him is the feeling that the people he encounters in London “were not also another Beast People, animals half wrought into the outward image of human souls, and that they would presently begin to revert, to show first this bestial mark and then that.” In a final attempt to preserve his sanity, Prendick retreats from “the confusion of cities and multitudes” to the solitude of the country:

I see few strangers, and have but a small household. My days I devote to reading and to experiments in chemistry, and I spend many of the clear nights in the study of astronomy. There is – though I do not know how there is or why there is – a sense of infinite peace and protection in the glittering hosts of heaven. There it must be, I think, in the vast and eternal laws of matter, and not in the daily cares and sins and troubles of men, that whatever is more than animal within us must find its solace and its hope. I hope, or I could not live.

And so, in hope and solitude, my story ends.

Prendick here seeks a Kantian solution to his problem with the Beast People. He hopes that looking up at the glittering hosts of heaven will help him to forget about his traumatic experience on Moreau’s island by annihilating as it were his importance as an animal creature. He tries to escape the grotesque orbit of Moreau’s island at the end of the novel by locating the origin of humanity beyond the earth: in the stars. But the reader recognizes the fragility of this final affirmation that vertical orientation remains proper to the human. Prendick’s experience of the Beast People has served precisely to dissociate human uprightness from divinity. In the preface to a 1933 edition of his scientific romances, Wells calls Moreau “an exercise in youthful blasphemy. Now and then, though I rarely admit it,” he continues, “the universe projects itself towards me in a hideous grimace. It grimaced that time, and I did my best to express my vision of the aimless torture in creation” (IDM 183). As John Batchelor notes, the grimace, “the grotesque or distorted facial expression, becomes a leading motif in the story.”Footnote 31 This motif of the grimace is another attack by Wells on the idea that humans are made in the image of God.

One of the arguments I develop in this book is that, in its operation, the fable resembles the grotesque. According to Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin in his classic 1965 study of the grotesque, Rabelais and His World: “The essential principle of grotesque realism is degradation, that is, the lowering of all that is high, spiritual, ideal, abstract; it is a transfer to the material level, to the sphere of earth and body in their indissoluble unity.” Degradation and the debasement of the higher, Bakhtin continues, “do not have a formal and relative character in grotesque realism. ‘Upward’ and ‘downward’ have here an absolute and strictly topographical meaning. ‘Downward’ is earth. ‘Upward’ is heaven.”Footnote 32 In fable, I claim, as in the grotesque, degradation and debasement of the higher acquire a strictly topographical meaning. Downward is earth. Upward is heaven. In Moreau, Wells uses fable to degrade the human. Rather than making us look up, Prendick’s first-person narration makes us look down and confront the disgust we unconsciously feel toward forms of animal life we deem as lower than us on the hierarchy of being. In particular, Moreau evokes what Susan D. Bernstein calls “the anxiety of simianation, a discomfort over evolutionary ties between humans and other primate species.”Footnote 33 The anxiety of simianation is the unscientific fear that humans might somehow degenerate to the level of apes or that apes might somehow ascend the ontological ladder to the level of humans.

Twentieth-century fabulist Franz Kafka makes this latter possibility – of apes climbing the ontological ladder to become human – the premise of his darkly humorous 1917 evolutionary fable “A Report to an Academy.” In Kafka’s story, to which I will continually return in the following chapters, the ape Red Peter, who has been shot and captured in the Gold Coast by a hunting party from the company of Carl Hagenbeck, tells a gathering of scholars in Germany of his incredible transformation into a human being. Although he undergoes no outward physical change, Red Peter has in the space of five short years learned to speak and act like a human. “Almost five years separate me from the time of my apedom,” he tells the academy, “not much time in calendar terms, but an eternity to have had to gallop through as I have done … To speak plainly … your apehood, gentlemen, inasmuch as you have something of the sort behind you, cannot be any remoter from you than mine is from me.”Footnote 34 As this final passive aggressive remark indicates, the purpose of Red Peter’s dramatic monologue is not just to make him seem more human to his audience, but also to make this captive human audience seem more apelike.

The geologist Charles Lyell wrote in 1859 that to accept evolution fully was to “go the whole orang.”Footnote 35 For Lyell, going “the whole orang,” a play on the expression “to go the whole hog,” meant painfully foregoing the biblical idea that humans were created separately from the rest of the animal kingdom. “To go the whole orang … meant not just to treat humans scientifically but to go all the way to making them animals like all the rest.”Footnote 36 One of the ways in which the post-Darwinian literary writer might “go the whole orang” or think the animality of the human without recourse to a divine order, I suggest in this book, is to produce animal fables. As I will show, the rise of the biological sciences in the second half of the nineteenth century provides writers with new material for the fable, new ways to exploit the grotesque comparison of human and ape.

Robert Louis Stevenson, whose fables I examine in Chapter 3, is perhaps the first to realize the significance of evolution for the literary form of the fable, when he observes in an 1874 review of Lord Lytton’s Fables in Song: “a comical story of an ape touches us quite differently after the proposition of Mr. Darwin’s theory.”Footnote 37 Writing some three years after the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Descent of Man as a twenty-three-year-old law student and neophyte author, Stevenson begins to theorize the idea of the post-Darwinian fable in his review of Lytton’s book. His main point is that the fable becomes less fabulous after evolution, as we start to recognize our own story in the story of an ape. “In the progressive centralisation of thought,” Stevenson writes, “we should expect the old form of fable to fall gradually into desuetude, and be gradually succeeded by another, which is a fable in all points except that it is not altogether fabulous.” This new form, he continues, “still presents the essential character of brevity; as in any other fable also, there is, underlying and animating the brief action, a moral idea; and as in any other fable, the object is to bring this home to the reader through the intellect rather than through the feelings; so that, without being very deeply moved or interested by the characters of the piece, we should recognise vividly the hinges on which the little plot revolves.” But the crucial difference between the old and new forms of fable is that “the fabulist now seeks analogies, where before he merely sought humorous situations.” The post-Darwinian fable, Stevenson thinks, is more serious and existential in focus than the traditional fable. The moral of the story becomes “more indeterminate and large.” One cannot “append it, in a tag, to the bottom of the piece, as one might write the name below a caricature; and the fable begins to take rank with all other forms of creative literature, as something too ambitious, in spite of its miniature dimensions, to be resumed in any succinct formula without the loss of all that is deepest and most suggestive in it.”Footnote 38 Stevenson’s 1886 novella Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, in which the respectable or “upright” Victorian gentleman Henry Jekyll transforms into the “troglodytic,” “apelike” Edward Hyde, perfectly illustrates his idea of the post-Darwinian fable.Footnote 39

As Stevenson notes, classic animal fables have a bipartite form. A fable is, precisely, a brief story with a moral. The moral of the story, which usually follows but sometimes precedes the fable narrative, enacts a shift from the animal to the human realm. According to Jill Mann: “The animal–human shift is the reason why the classic fable is bipartite in form – why the morality has to stand outside of and apart from the fable narrative. … It is only when the narrative is complete that the final shape of the story can be seen to yield a meaning that can be transferred to the human sphere.”Footnote 40 We can clearly see this animal–human shift take place in the twelfth-century fabulist Marie de France’s version of Aesop’s classic fable “The Wolf and the Lamb.” The fable narrative tells of how a wolf picks a fight with a lamb drinking downstream from him. The wolf falsely accuses the lamb of stirring up the water he drinks. “But, sire,” the lamb responds reasonably, “you drink upstream from me. / I drink the water you have had.” Eventually, after making further baseless accusations, the wolf seizes and strangles the lamb. Marie’s concluding moral sees the natural hierarchy of predator and prey reflected in human society.

Marie’s “The Wolf and the Lamb” eloquently refutes Stevenson’s charge that the traditional fabulist does not seek analogies between animal and human behavior. Her point in the fable is that humans become more predatory in their behavior the higher up they are on the social ladder. As we will see in more detail in Chapter 2, fables often seek to reduce human motivation to the logic or law of animal predation: “The nature of the beast and, by analogy, of the human animal is to eat or be eaten.”Footnote 42

While wrong on the point of analogy, Stevenson is right to identify a change in the fable’s form after Darwin. The post-Darwinian fable neither displays the bipartite form nor enacts the animal–human shift of the classic fable. Rather than guiding readers from the animal to the human realm as the classic fable does, the post-Darwinian fable implicates readers in the biological order by forcing them to contemplate and confront the existential fact of their apehood. As Marian Scholtmeijer notes, “In a post-Darwinian world, all stories are stories about apes told by other apes – or at least primates.”Footnote 43 What Darwin’s theory of evolution makes possible, I suggest in this book, is the idea of a scientific fable that critiques the human by grotesquely combining the discourses of philosophy, anthropology, theology, and science. Flusser presents his highly speculative 1987 study of the vampire squid, Vampyroteuthis Infernalis, as a kind of scientific fable. He writes: “What will be presented here is … not a scientific treatise but a fable. The human and its vertebrate Dasein are to be criticized from the perspective of a mollusk. Like most fables, this one is ostensibly concerned with animals. De te fabula narratur [About you the fable is told].”Footnote 44 The theoretical challenge set us by the idea of the post-Darwinian fable is to “go the whole orang” by trying to think the human predominantly in relation to its biological milieu, for example, from the perspective of a Beast Person or a mollusc.

Friedrich Nietzsche writes in an aphorism from Human, All Too Human (1878) titled “Circular Orbit of Humanity,” “Perhaps the whole of humanity is no more than a stage in the evolution of a certain species of animal of limited duration: so that man has emerged from the ape and will return to the ape, where there will be no one present to take any sort of interest in this strange comic conclusion.”Footnote 45 Whereas Nietzsche chooses the form of the aphorism to critique the theological pretensions of humans, other post-Darwinian writers like Wells, Stevenson, and Kafka choose the form of the beast fable. As we will see in the coming chapters, the fable offers these writers a readymade literary form with which to interpret, translate, and transform evolutionary and anthropological discourse of the mid- to late nineteenth century. The fable is ideally suited to this task of reconceptualizing the place of humans in nature not just because of its focus on the animal but also because of its un-novelistic features of narrative brevity and conceptual pithiness. As Stevenson recognizes, the object of the post-Darwinian fable is to bring the point of the story “home to the reader through the intellect rather than through the feelings; so that, without being very deeply moved or interested by the characters of the piece, we should recognise vividly the hinges on which the little plot revolves.”Footnote 46

The Darwinian Grotesque

Drawing literary authors such as Wells, Stevenson, and Kafka to Darwin, I suggest, is the spirit of the grotesque in his work – or what we might now call his biological existentialism. A number of critics have commented on Darwin’s use of the grotesque. Gillian Beer writes in her classic study Darwin’s Plots: “Darwin’s theories, with their emphasis on superabundance and extreme fecundity, reached out towards the grotesque. Nature was seen less as husbanding than as spending. Hyperproductivity authenticated the fantastic.”Footnote 47 According to Jonathan Smith in Charles Darwin and Victorian Visual Culture, “Much of Darwin’s work, and many of his illustrations, can be characterized as grotesque: the bizarre sexual arrangements of barnacles and orchids; the outré forms of fancy pigeons; the extravagant plumage, ornament, and weaponry of male birds; the hideous facial expressions of Duchenne’s galvanized old man; the elaborate traps of insectivorous plants.”Footnote 48 In Darwin, grotesque realism functions, as it does for Bakhtin, to reorient the human perspective away from the heavens and toward the earth. As George Levine notes in Darwin the Writer, “Darwin’s exploitation of the grotesque was a function of the nature of his task and his argument: the grotesque, it developed, was the best argument against the idea of a world entirely and rationally designed, and nature was full of grotesques.”Footnote 49

Nowhere is Darwin’s grotesque reorientation of human perspective more evident than in his final book, The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms (Reference Darwin1881), which ends with a tribute to the productive grotesquerie of the lowly worm. Darwin writes:

When we behold a wide, turf-covered expanse, we should remember that its smoothness, on which so much of its beauty depends, is mainly due to all the inequalities having been slowly levelled by worms. It is a marvellous reflection that the whole of the superficial mould over any such expanse has passed, and will pass again, every few years through the bodies of worms. … It may be doubted whether there are many other animals which have played so important a part in the history of the world, as have these lowly organised creatures.Footnote 50

Rather than as something insignificant to the human, Darwin here presents the lowly worm as a vital player in world history. As Adam Phillips realizes, Darwin’s paean to the earthworm implies a significant existential reorientation of the human. “What would our lives be like if we took earthworms seriously,” Phillips writes, “took the ground under our feet rather than the skies high above our heads, as the place to look, as well, eventually, as the place to be? It is as though we have been pointed in the wrong direction.”Footnote 51 The Darwinian grotesque functions, in other words, as an existential corrective: it points us in the right direction, which happens to be down rather than up.

When he went to have lunch with the Darwins at Down House in 1881, the atheist doctor and Darwin popularizer Edward B. Aveling expressed astonishment on being told about the imminent publication of The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms:

In my youthfulness I expressed a foolish surprise that he who had written the “Origin of Species” should deal with a subject so insignificant as worms. I see his face now, as he turned it on mine and said quietly: “I have been studying their habits for forty years.” I might have remembered better his own persistent teaching, that in Nature no agency can be regarded as insignificant, that the most stupendous effects have been produced by the ceaselessly repeated action of small forces.Footnote 52

Aveling wonders why the author of the Origin of Species would condescend to write on the insignificant topic of worms. But this is precisely the lesson of Darwin’s grotesque realism: “in Nature no agency can be regarded as insignificant … the most stupendous effects have been produced by the ceaselessly repeated action of small forces.”

One way to understand the Darwinian revolution is as a radical reevaluation of the status of the downward gaze. In English, the idiomatic expression looking down connotes condescension: to look down on something is to see that thing as unworthy or lowly. But Darwin’s grotesque realism challenges this negative connotation we usually attach to the idea and the act of looking down. “Other creatures look to the earth,” Donne writes in Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, “and even that is no unfit object, no unfit contemplation for man, for thither he must come; but because man is not to stay there, as other creatures are, man in his natural form is carried to the contemplation of that place which is his home, heaven.”Footnote 53 Darwin’s vision of the human is grotesque precisely for privileging the earthly over the heavenly, the act of looking down over the act of looking up.

We can observe this favoring of the mundane over the celestial in an often-cited passage from his autobiography, in which Darwin reflects on the existential implications of the doomsday theory put forward by William Thomson, Lord Kelvin in 1862 that the sun will eventually cool, thereby leaving the Earth too cold to sustain any form of life:

With respect to immortality, nothing shows me how strong and almost instinctive a belief it is, as the consideration of the view now held by most physicists, namely, that the sun with all the planets will in time grow too cold for life, unless indeed some great body dashes into the sun and thus gives it fresh life. – Believing as I do that man in the distant future will be a far more perfect creature than he now is, it is an intolerable thought that he and all other sentient beings are doomed to complete annihilation after such long-continued slow progress. To those who fully admit the immortality of the human soul, the destruction of our world will not appear so dreadful.Footnote 54

In the face of the thought of total extinction, Darwin eschews the consolatory possibility of personal immortality in order to express existential solidarity with other animals. As Beer notes, “What makes the idea of the dying sun so dreadful to him is that the ‘improved’ mankind ‘and all other sentient beings’ will share this extinction.”Footnote 55 Accompanying the existential turn away from the divine in Darwin’s thought is a turn toward the nonhuman animal in its biological milieu.

Darwin’s struggles with maintaining religious belief in the face of the mounting evidence he saw for the theory of evolution are well documented. In a famous January 11, 1844 letter to his friend, the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, he writes, “I am almost convinced (quite contrary to the opinion I started with) that species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable.”Footnote 56 In his 1838 notebook on the transmutation of species, he both expresses and recoils from the idea of radical materialism: “love of the deity effect of organization … oh you Materialist! … Why is thought being a secretion of brain, more wonderful than gravity a property of matter? It is our arrogance, it [is] our admiration of ourselves.”Footnote 57 Rather than atheist, the word Darwin preferred to describe himself with is the gentler one coined by his friend Thomas Henry Huxley: agnostic.

Extinction was a relatively new idea in natural history when Darwin was writing On the Origin of Species in 1858 and 1859. The French naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier had established the term at the end of the eighteenth century, and even then it was “a source of alarm since it implied that God’s sequence of special creations had not all survived.”Footnote 58 The extinction of species suggested by the fossil record represented a theological conundrum. Robert Plot, a professor of chemistry and early paleontologist, expressed the terms of the problem in 1677: “If it be said, that possibly these Species may now be lost, I shall leave it to the Reader to judge, whether it be likely that Providence, which took so much care to secure the Works of the Creation in Noah’s Flood, should either then, or since, have been so unmindful of some Shell-Fish (and of no other Animals) as to suffer any one Species to be lost.”Footnote 59 By presenting nature as the site of constant and destructive transformation, the notion of the extinction of species posed a direct threat to the Christian worldview. How could one maintain belief in the static order of the great chain of being if the survival of any one species could not be guaranteed? In the Origin, Darwin made extinction central to his theory of evolution: “The theory of natural selection is grounded on the belief that each new variety, and ultimately each new species, is produced and maintained by having some advantage over those with which it comes into competition; and the consequent extinction of less-favoured forms almost inevitably follows.”Footnote 60 In contrast to Cuvier, who argued that species went extinct in great catastrophes, Darwin suggested that extinction was a gradual process, the result of competition between species or of a species’ maladaptation to its environment. Six times in the Origin, Darwin cites “that old canon in natural history, ‘Natura non facit saltum’ [nature makes no leap].”Footnote 61

Just as Phillips does in relation to Darwin’s worm work, Beer draws out the existential implications of Darwin’s thinking about extinction: “Extinction is mortality writ large and human beings in current secular societies have – paradoxically – very contracted life spans compared with Victorian believers. We may live longer on earth, but there is no expectation of future life beyond death.”Footnote 62 In contrasting current secular attitudes toward extinction with those of Victorian believers, Beer quotes the English nature writer Richard Jefferies from his 1883 autobiography The Story of My Heart: “Only by the strongest effort of the mind could I understand the idea of extinction; that was supernatural, requiring a miracle; the immortality of the soul natural, like earth.”Footnote 63

Darwin’s theory of evolution distinguished itself not just from the static worldview of Christian theology but also from older understandings of transformation. Beer writes: “‘Omnia mutantur, nihil interit.’ Everything changes, nothing dies. Ovid’s assertion in Metamorphoses marks one crucial distinction between the idea of metamorphosis and Darwin’s theory of evolution. Darwin’s theory required extinction. Death was extended from the individual organism to the whole species. Metamorphosis bypasses death. The concept expresses continuance, survival, the essential self transposed but not obliterated by transformation.”Footnote 64 Underpinning Ovidian metamorphosis is the ancient doctrine of metempsychosis that “supposes the soul is a living principle not attached to the individuality of one specific existence or another.”Footnote 65 Pythagoras expounds his theory of the transmigration of the soul in Book XV of the Metamorphoses: “Our souls are immortal, and are ever received into new homes, where they live and dwell, when they have left their previous abode. … All things change, nothing dies: the spirit wanders hither and thither, taking possession of what limbs it pleases, passing from beasts into human bodies, or again our human spirit passes into beasts, but never at any time does it perish.”Footnote 66 In a famous anecdote from the history of philosophy, Pythagoras apparently once came to the aid of a dog that was being beaten in the street in Croton by saying to the dog’s tormentors that the creature was one of his old friends reincarnated in the form of an animal. Rather than reincarnation, the transformation of human into animal or of animal into human in the post-Darwinian fable is more likely to figure finitude and extinction.

While being inspired by evolutionary theory, the literary writers I examine in this book also break with Darwin’s conception of things in certain key respects. Not bound by the dictates of scientific method, these writers freely combine scientific with mythological and theological ideas about physical plasticity. As we will see, Ovid’s Metamorphoses continues to vie with the Origin of Species in the post-Darwinian literary imaginary. Many of the fables I discuss in this book pivot on the idea of a spontaneous and fantastic metamorphosis of a character or group of characters. In this way, they contravene that old canon of natural history and scientific realism to which we have seen Darwin cleave: that “nature makes no leaps.” Once again, I find Stevenson prescient in this regard, when he writes in his notebooks of 1874–5:

One would have thought that its [evolution’s] action was on the face of things; but on the other hand, one would have thought that the presence of other modificative and co-modificative principles in all the phenomena to be explained, was equally patent and unmistakable. And accordingly Darwin is reminding us every page that he postulates “spontaneous variations” or “compensations of growth” or “correlated variations” or something of the kind, as the material which his selection is to weigh in the balance and keep and cast away as useless; in other words, that all spontaneity, all inception, is independent of his own special doctrine.Footnote 67

While Darwin conceives of evolution as a slow and gradual process, the post-Darwinian fable presents physical transformation in far more dramatic terms: as a fantastic and spontaneous leap of nature and compression of evolutionary time.

Consider the example of Kafka’s 1915 text The Metamorphosis, perhaps the most famous animal fable of the twentieth century, in which Gregor Samsa wakes one morning from uneasy dreams to find himself suddenly and inexplicably transformed into “some sort of monstrous insect.” Susan Bernofsky, who has recently translated The Metamorphosis into English, explains the difficulty of rendering Kafka’s German epithet ungeheueres Ungeziefer: “Both the adjective ungeheuer (meaning ‘monstrous’ or ‘huge’) and the noun Ungeziefer are negations – virtual nonentities – prefixed by un. Ungeziefer comes from the Middle High German ungezibere, a negation of the Old High German zebar (related to the Old English tīber), meaning ‘sacrifice’ or ‘sacrificial animal.’ An ungezibere, then, is an unclean animal unfit for sacrifice, and Ungeziefer describes the class of nasty creepy-crawly things.”Footnote 68 Gregor’s fantastic transformation into a monstrous vermin indicates his alienation not just from the human community but also from God. Like Stevenson and Wells before him, Kafka uses fabulous metamorphosis to express the theological grotesque, the irreversible degradation of Homo erectus into some lower form of life.

Franz Kafka, Fabulist

Kafka is an important test case for some of the arguments I make in this book. A number of critics praise Kafka as a kind of literary zoographer – as a writer, that is, who genuinely wonders what it is like to be an animal and how this act of sympathetic identification with the nonhuman affects our idea of the human. Walter Benjamin set the tone for this scholarship when he famously remarked in a 1934 essay commemorating the tenth anniversary of Kafka’s death: “You can read Kafka’s animal stories for quite a while without realizing that they are not about human beings at all. When you finally come upon the name of the creature – monkey, dog, mole – you look up in fright and realize you are already far away from the continent of man.”Footnote 69 In discussing Kafka’s treatment of animals, recent critics of his often feel it necessary to dissociate him from the fable tradition. Thus, according to Jean-Christophe Bailly in his book The Animal Side, Kafka is the only writer “who has given animals speech (as he did in ‘The Burrow,’ but also in ‘Josephine the Singer’ and in many other texts) and succeeded in doing so in a register that was no longer that of the fable. Whereas in fables animals are presented only beneath the words, and play roles that provide a sort of allegorical tutelage, in Kafka’s texts animals seem to be resurfacing from some obscure depths, as it were, and appropriating human language for themselves in order to shed light on those depths.”Footnote 70 Similarly, in her classic 1985 study Beasts of the Modern Imagination, Margot Norris includes Kafka in the small circle of writers, thinkers, and artists she dubs the biocentric tradition. This tradition begins with Darwin, “the naturalist whose shattering conclusions inevitably turned back upon him and subordinated him, the human being, the rational man, the scientist, to the very Nature he studied.” Biocentric writers, Norris observes, are those who “create as the animal – not like the animal, in imitation of the animal – but with their animality speaking.” Animals appear in the texts of biocentric writers such as Kafka, she continues, “not as the tropes of allegory or fable, but as narrators and protagonists reappropriating their animality amid an anthropocentric universe.”Footnote 71

Norris opposes the biocentric to the anthropocentric: “The differences between biocentric and anthropocentric art correspond to the models of animal and human desire and the opposition they engender between creatural and cultural man.”Footnote 72 The fable is anthropocentric, for her, because it dresses animals in the cultural clothing of the human in order to act out purely human dramas. Likewise, for Bailly, “The conceit of the fable is to have animals talk, to bestow the gift of the logos upon them, not in order to get them into line, but rather to get us out of it … but ready to get back into it very quickly, as soon as it becomes apparent that the animals are stand-ins or effectively allegorical representations of the human comedy.”Footnote 73 What Norris and Bailly both fail to grasp about fables is that the animals in them are only partially humanized or allegorized. As Jeremy B. Lefkowitz notes, “rather than simply symbolizing this or that human behaviour, animal fables also draw attention to the animal part of the functional analogism of fable, which signifies that the animals have been only partially analogized to human beings, behaving in some ways like humans but retaining the outward appearance and eating habits of animals.”Footnote 74 This is clearly the case with Kafka’s animals. They are hybrid creatures: partly anthropomorphized by being endowed with the power of speech and reason, but also partly still animal bodies that eat and are eaten. Making Kafka’s animal stories fables is precisely the fact that they establish a productive tension between the human perspective and the animal perspective. As Vladimir Nabokov remarks about The Metamorphosis, “Kafka’s art consists in accumulating on the one hand Gregor’s insect features, all the sad detail of his insect disguise, and on the other, in keeping vivid and limpid before the reader’s eyes Gregor’s sweet and subtle human nature.”Footnote 75

Another reason why Kafka is vital to my argument in this book is that he critiques vertical posture in his work. What else is Kafka’s literature, we might ask, but a dismantling of the upright man of the theological and philosophical tradition? In a short text from 1923, he writes, “at the desk, that’s my place, my head in my hands, that’s my posture.”Footnote 76 In a well-known letter he wrote to his fiancée Felice Bauer on March 3, 1915, he speaks of “the terror of standing upright”: “However, I do want to interpret your dream. Had you not been lying on the ground among the animals, you would have been unable to see the sky and the stars and wouldn’t have been set free. Perhaps you wouldn’t have survived the terror of standing upright [die Angst des Aufrechtstehns]. I feel much the same; it is a mutual dream that you have dreamed for us both.”Footnote 77 Kafka here inverts the theological tradition I have been examining in this chapter by attributing the freedom to gaze up at the sky and stars not to the upright human, as tradition would have it, but rather to the prone animal. As Elias Canetti glosses the passage: “One must lie down with the beasts in order to be set free, or redeemed (erlöst). Standing upright signifies the power of man over beast; but precisely in this most obvious attitude man is exposed, visible, vulnerable.”Footnote 78

Time and again in his writing, Kafka shows us how changes in physical orientation bring about changes in existential orientation. Consider the following passage from an August 1904 letter to his friend Max Brod, in which he relates an incident that occurred one day while he was out walking his dog.

My dog came upon a mole that was trying to cross the road. The dog repeatedly jumped at it and then let it go again, for he is still young and timid. At first I was amused, and enjoyed watching the mole’s agitation; it kept desperately and vainly looking for a hole in the hard ground. But suddenly when the dog again struck it a blow with its paw, it cried out. Ks, ks, it cried. And then I felt – no, I didn’t feel anything. I merely thought I did, because that day my head started to droop so badly that in the evening I noticed with astonishment that my chin had grown into my chest.Footnote 79

The bent head is a recurring image in Kafka.Footnote 80 Here, it comically expresses the theological grotesque. As Canetti analyzes the scene:

Kafka, so exalted above [the mole and the dog], by his upright stance, his height, and his ownership of the dog, which could never threaten him, simply laughs at the desperate and ineffectual movements of the mole. The mole … has not learned to pray, and it is capable of nothing but its small screams. They are the only sounds that touch the god, for here he is the god, the supreme being, the zenith of power, and in this case God is even present. The mole screams Ks, ks, and the onlooker, hearing this scream, transforms himself into the mole.Footnote 81

The moment Kafka gives up the sense of godlike superiority that comes from being a large and upright animal in the scene, the vertical order collapses for him and he starts to feel what it is like to be a mole.

According to the first-person narrator of Kafka’s 1914 fragment “Memoirs of the Kalda Railway”: “You can see small animals clearly only if you hold them before you at eye level; if you stoop down to them on the ground and look at them there, you acquire a false, imperfect notion of them.”Footnote 82 Canetti thinks he recognizes in this passage an essential aspect of Kafka’s storytelling practice:

One must view small animals at eye level to see them accurately. This is tantamount to raising them to equal status. Stooping to the earth – a sort of condescension – gives one a false, incomplete conception of them. This raising of smaller animals to eye level makes one think of Kafka’s tendency to magnify such creatures: the insect in The Metamorphosis, the molelike creature in “The Burrow.” Through the closer approach to the animal and the animal’s resultant magnification, transformation into something smaller becomes a more plastic, tangible, credible process.Footnote 83

Kafka raises the ontological status of his small animal characters through a process of grotesque magnification. This act of magnification not only makes the fantastic transformation into a small animal more credible, but also has the effect of troubling the distinction between human and animal.

Scholars working in the field of animal studies have tended either to denigrate or to ignore the literary form of the fable. According to John Simons in his 2002 study Animal Rights and the Politics of Literary Representation: “the role of animals in the fable is almost irrelevant. They are merely vehicles for the human and are not, in any way, presented as having physical or psychological existence in their own right. … [They] can teach us nothing about the deeper relationships between the human and the non-human.”Footnote 84 It is perhaps for this reason that philosopher Kelly Oliver, in an otherwise excellent study, decides not to discuss the form of the fable in her 2009 book Animal Lessons: How They Teach Us to Be Human.

Animal Fables after Darwin attempts to recoup the fable for literary animal studies by presenting it as a biocentric story form that orients the human reader toward the nonhuman. The fable, I contend, closes the ontological gap between the human and the nonhuman animal in two related ways. First, it grotesquely magnifies nonhuman animals by granting them the power of speech and reason. Second, it existentially reorients the human perspective toward the earth and the nonhuman animal. As anthropologist John Hartigan notes in his book Aesop’s Anthropology:

[Fables] stage other species as capable of speaking to us. This is, of course, not unfettered or human speech; the fables can rightfully all be charged with ventriloquizing nonhumans in shamelessly moralistic manners. But they do present both the possibility and problem of how we might listen to and then learn from other species. As in species thinking, the predicaments of nonhumans are seen as having bearing on our situations and being entangled in our fate and livelihoods. The fables are an argument that other species are worthy of attention for more than their functional uses, because we may be able or need to learn something from them.Footnote 85

My claim in this book is that fables can and do teach us how to be human. To see how the fable has always exemplified a type of species thinking in which “the predicaments of nonhumans are seen as having bearing on our situations and being entangled in our fate and livelihoods,” we need to turn to the quasi-mythical figure often considered to be the progenitor of the genre: namely, Aesop.

The Aesopian Grotesque

It is still uncertain whether Aesop actually existed. No accounts of him survive from the period in which we believe him to have lived, the sixth century BCE. Details of his life appear from the fifth century BCE onward in canonical Greek authors such as Herodotus, Aristotle, and Plutarch. What is consistently reported about Aesop is that he was a hideously ugly slave of non-Greek origin. An anonymous second-century CE fictional account of the life of Aesop known as The Aesop Romance or The Life of Aesop begins thus:

The fabulist Aesop, the great benefactor of mankind, was by chance a slave but by origin a Phrygian of Phrygia [modern-day Turkey], of loathsome aspect, worthless as a servant, potbellied, misshapen of head, snub-nosed, swarthy, dwarfish, bandy-legged, short-armed, squint-eyed, liver-lipped – a portentous monstrosity. In addition to this he had a defect more serious than his unsightliness in being speechless, for he was dumb and could not talk.Footnote 86

Aesop’s physical grotesquerie and muteness make him seem more animal than human – precisely the opposite of the upright man of classical thought. As Peter W. Travis comments, “A chaotic mélange of body parts that may be imagined as having been assimilated from the very animals populating his fables, the anticlassical and subaltern misshapenness of Aesop’s body would seem to query the conventional definitions of what it means to be human.”Footnote 87 Throughout the Aesop Romance, Aesop finds himself being comically compared to various animals and objects. When he meets the people of Samos for the first time, they burst out laughing and shout: “What a monstrosity he is to look at! Is he a frog, or a hedgehog, or a potbellied jar, or a captain of monkeys, or a moulded jug, or a cook’s gear, or a dog in a basket?” (AR 148).

The fable as genre predates Aesop. It probably originated in Sumer and Mesopotamia sometime around 800 BCE. Archaeologists have discovered “didactic narrative works on clay tablets and in scripts that resemble the fable in form as well as subject matter, and these Sumerian and Babylonian texts were probably transmitted orally and through manuscripts to the ancient Greeks.”Footnote 88 But the myth of Aesop as the founder of the fable persists because we recognize the genre’s condition of possibility in the metamorphic grotesqueness of his body. According to Serres, Aesop’s “misshapen, potent, simian, hunchbacked and theatrical ugliness” allows him to project himself into every species in order to tell his fables: “The Life of Aesop, that’s the title of the founding apologue every fabulist must write; as if this canonical man’s body and language imitated the bodies and language of animals, plants, mountains, kings and cobblers. The fables’ corpus relates Aesop’s body in detail.”Footnote 89 Aesop shows in his fables that the human body can only simulate the life of the nonhuman things around it by first inclining itself toward the earth and becoming grotesque. In the fable, Annabel Patterson reminds us, “the mind recognizes rock bottom, the irreducibly material, by rejoining the animals, one of whom is the human body.”Footnote 90

Recognizing that the traditional fable operates under the sign of the grotesque allows us to see how the form challenges classical conceptions of the human. In her remarkable study Aesopic Conversations, Leslie Kurke argues that the Aesop tradition contests the established forms of high wisdom by embodying “a distinctive sophia of the abjected and the disempowered.” In her analysis of Aesopic parody, Kurke focuses on the de-hierarchizing power of the grotesque body:

Aesopic parody often mobilizes coarse, bodily, and obscene representations to undermine the high tradition from below. Thus we see the violent or indecorous eruption of the bodily deployed to challenge the tradition of sophia and to deny its practitioners’ claims to otherworldly sources of authority (whether divine or ancestral). From their claimed status as mediators between this and an other world, the practitioners of sophia are reduced and located in the realm of brute meat. At the same time, the Aesopic parody often works by exposing how such claims to high wisdom endorse and enable inequitable power relations and the oppression of the weak by the strong.Footnote 91

One of the examples Kurke provides as evidence for the Aesopian parody of high wisdom is particularly relevant to my study because it concerns the vertical orientation of the human. Kurke here compares two visual images. The first is the tondo of an Attic red-figure cup, found in Vulci and probably dating to the mid-fifth century BCE (Figure 1). Now housed in the Museo Gregoriano of the Vatican, the interior of this cup depicts a man with an absurdly large head in animated conversation with a fox. The two figures sit casually on outcroppings of rock facing each other. The deformed man is wrapped in a cloak and holding a walking stick. The fox is gesticulating emphatically with its right forepaw. Both have their mouths open. Neither figure is labeled. But the man’s deformity and the dialogue with the animal led the archaeologist Otto Jahn in 1847 to propose that this is a representation of Aesop talking with his fable character the fox. According to François Lissarrague, who accepts this speculative identification of the figures, “The image of Aesop and of the fox is presented, in this context, not as an honorific portrait of the classical type, but as the depiction of a speech situation, an amusing allusion not only to the fabulist himself, but to the game of the fable, of the animal endowed with speech.”Footnote 92

Figure 1 Aesop (?) in conversation with a fox.

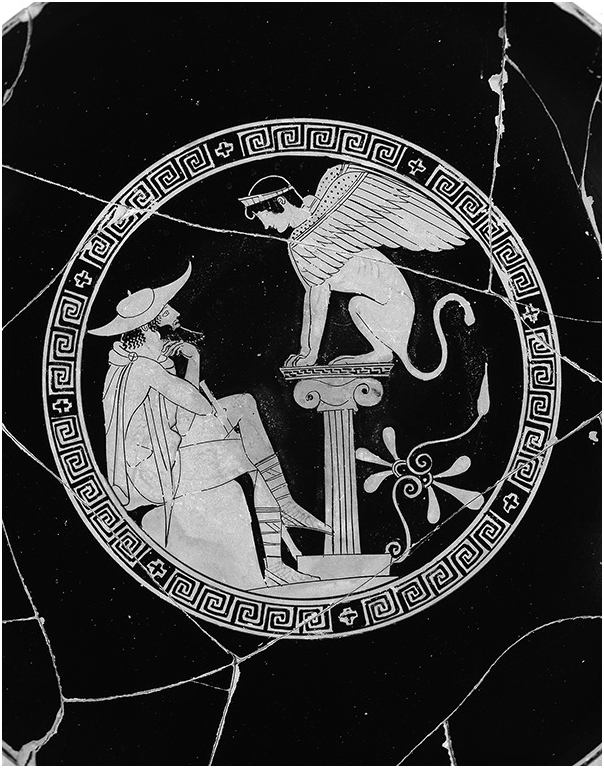

Kurke claims that this image of Aesop in colloquy with the fox parodies an earlier tondo of an Attic red-figured cup representing Oedipus confronting the sphinx (Figure 2). The Oedipus Painter produced the most famous version of this image around 470 BCE. Also housed in the Vatican, the interior of this cup depicts Oedipus sitting pensively with his legs crossed before the sphinx. This scene immediately strikes the viewer as more tense and formal than the one involving Aesop and the fox. In contrast to Aesop, who must look down in order to speak to the fox, Oedipus looks up at the sphinx, which perches close-mouthed on an Ionic column to the right above him. While Aesop sits with his mouth open, Oedipus sits with his lips just parted as if he is about to speak his answer to the sphinx’s riddle. Oedipus here represents human wisdom engaged in a contest with the otherworldly sphinx.

Figure 2 Oedipus in conversation with the Sphinx.

The image of Aesop and the fox parodies the image of Oedipus and the Sphinx in two ways. First, it inverts the orientation of the human in the scene. Where Oedipus’ upward orientation expresses a sense of awe and reverence toward the otherworldly, Aesop’s downward orientation expresses a sense of interspecies garrulity. Second, it replaces the classical body of Oedipus with the grotesque body of Aesop. As Kurke notes:

[Oedipus’] triumphant wisdom is figured and matched by his bodily perfection – he is the very paradigm of the mature Greek male, the “classical body” par excellence. … In radical contrast to this ideal figuration of human sophia, Aesop’s form is misshapen and grotesque. … His hair is receding, his forehead lined with wrinkles, his nose overlarge and protuberant, his beard scraggly. And perhaps in a gesture toward Aesopic makrologia or garrulity, both figures have their mouths wide open, in contrast to the largely closed forms of Oedipus and the sphinx.Footnote 93

The grotesqueness of Aesop’s body is conveyed not just by its lack of proportion but also by its metamorphic openness to the nonhuman animal. While Oedipus and the sphinx appear as closed, individuated forms, a mesmerized-looking Aesop appears to be channeling the fox. In comparing these two images, we see once more how existential disposition is a function of physical orientation. Oedipus seeks the truth of the human theologically by looking up at the sphinx; Aesop seeks it in the opposite direction by talking to a lowly critter.

Animal Fables after Darwin examines writers who are storytellers in the mode of Aesop. Making the authors of this study latter-day Aesops is the fact that they emphasize the deconstructive and de-hierarchizing power of the grotesque body. For each, the grotesque metamorphism – or theatrical ugliness – of the human body allows it to project fabulously into other species and so contest the established forms of high wisdom from below. “How is Aesop’s body able to project itself so easily into every species?” Serres asks in Variations on the Body. “Victor Hugo gave one of his main characters, who resembled the fabulist, a nickname which summarizes my words, Quasimodo, a name that means ‘as if’: like animals, like other men and things, by taking their place, by substituting oneself for them, by acting like them, by portraying them and simulating them. Deformed, the bell ringer’s body appears monstrous because it can take on a thousand forms.”Footnote 94 In the iconic twentieth-century image of Gregor Samsa transformed in his bed into a monstrous bug, of the animal somehow miraculously in the place of the human, of the human body deformed into another form, we recognize not just the fate of the literary character but also the practice of the Aesopic storyteller. My interest in tracing the evolution of the post-Darwinian fable is not simply philosophical or literary-theoretical but also technical. In the following chapters, I try to demonstrate that the animal is at the centre of the storytelling practice of my chosen authors: Stevenson, Wells, Kafka, Powys, Garnett, Carter, and Coetzee.

In thinking about how these post-Darwinian literary writers use animals to tell stories, it is important to recognize the family resemblance between the Darwinian grotesque and the Aesopian grotesque. As John Berger notes: “Darwin’s evolutionary theory, indelibly stamped as it is with the marks of the European 19th century, nevertheless belongs to a tradition, almost as old as man himself. Animals interceded between man and their origin because they were both like and unlike man.”Footnote 95 Humans turn so readily to animals as vehicles for telling stories because animals are both like and unlike us, because there is a fabulous space and tension between the human perspective and the animal perspective. This, I suggest, is a transhistorical literary truth that connects Aesop’s time and Darwin’s time to our own. My aim in what follows is to show how the post-Darwinian fable expresses a form of biological existentialism that problematizes traditional philosophical and theological conceptions of the human. But it would be wrong to think of this as the emergence of an entirely novel way of telling stories with animals. Unlike Stevenson, I do not see the post-Darwinian fable as breaking fundamentally with the traditional form. Can’t we detect a kind of biological existentialism and theological grotesquerie, for example, in the following two sentences from a tragedy by Euripides that the Roman emperor Claudius was known to recite from memory at his villa on the island of Capri? “There is no human dominion,” Claudius would apparently say. “Above me I see only seabirds.”Footnote 96 Here, in what is a nice counterpoint to the biblical story of Nebuchadnezzar with which I began this chapter, the human looks up at the sky to acknowledge not the divine or even the divine in the human, but rather the human’s place among the other animals.