World War II is an important “remembered” time in Hawai‘i because even in the current decade, the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese Imperial Navy is a dramatic historic event that marked the US entry into global conflict. This event is highlighted within the State of Hawai‘i by a wide variety of historical sites, cultural/military museums and archival collections, and the continued military presence of operational US military bases. It cannot be overemphasized that the battleships USS Arizona and the USS Missouri are the alpha and omega of the World War II Hawai‘i experience—one representing the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the other representing the location where the Empire of Japan signed the surrender documents in 1945.

The local remembrance of the war goes well beyond these tangible reminders because the community remembers the intangibles of US military governance, the impacts of the incarceration of local citizens, and the presence of prisoners of war (POWs) within the community. After World War II, these reminders created a strong emphasis on social justice, including multiethnic labor movements called “The Democratic Revolution” of 1954 (Nakamura Reference Nakamura2020). This social justice milieu continues to shape debates in the state concerning issues that are in the forefront of US national and international concerns, such as taxation, land reform, environmental protection, human/women's/LGBTQ+ rights, collective bargaining, and comprehensive health insurance, to name a few (Falgout et al. Reference Falgout, Nishigaya, Palmero, Falgout and Nishigaya2014).

Largely forgotten until recently, however, has been the World War II–era incarceration story of the Hawaiian Islands, particularly the Honouliuli Internment and POW Camp (now designated the Honouliuli National Historic Site, or abbreviated as the Honouliuli NHS). The site was only recently rediscovered in the late 1990s by members of the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i, more than half a century after its closure. After its rediscovery, the University of Hawai‘i West O‘ahu (UH West O‘ahu) was encouraged to become involved, due to the site's proximity to the campus and its relevance to the history of the leeward (western) side of the island of O‘ahu. The faculty was known for conducting interdisciplinary research relating to the impacts of World War II within the Pacific Islands. Additionally, many members of the faculty, staff, and student body identified with the ethnicities of the incarcerated and imprisoned populations and their descendant families who were impacted by these events. Consequently, through the very nature and presence of the Honouliuli NHS, we had an opportunity to do something more expansive and considerably different from many university experiences that combined history, social justice, and democratic principles, and to offer an archaeological field school where students can develop a broad perspective of the World War II incarceration of some of Hawai‘i's residents as well as the imprisonment of captured enemy POWs.

Our faculty's archival and oral history research provided the pedagogical benefit of teaching our archaeological field school students the wider historical and ethical contexts relating to the Honouliuli NHS. The proximity of the site to both our campus and other World War II–era or earlier sites created a powerful experiential learning environment. The students could walk through the chronology of immigration and the growth of racism that led to the incarceration of longtime legal immigrant residents and US citizens. They also learned about the conditions faced by POWs. Finally, the understanding of the site's historical context in terms of fragile democratic principles and social justice was enhanced by partnerships within our community, including cultural centers, judicial history organizations, and state and national park systems. The National Park Service (NPS), now the primary land manager of the site, maintains the property for public education. The field school and UH West O‘ahu curriculum tied into their larger historical and education mission as part of the Valor in the Pacific Park system.

UH West O‘ahu's research and education at the Honouliuli NHS provided an opportunity to add local knowledge to its history, with the centerpiece of this effort being the summer course in Anthropology 381: Historical Archaeology Field Techniques (see Supplemental Text 1). The primary goals were to not only teach our students archaeological fieldwork but also explore these various topics related to social justice through experiential learning. With the large number of local interests and human resources and the very community-oriented societies of Hawai‘i, we were easily and increasingly able to develop community partnerships. Field trips and guest lectures enhanced experiential learning of the Honouliuli NHS and led to the development of a campus certificate-granting program on democratic principles and social justice.

Words do matter. The terminology of the period of forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans can be confusing and contradictory (Burton et al. Reference Burton, Farrell, Lord and Lord2002). We avoid the euphemisms used by the various US government offices to describe these situations, such as “evacuations,” “relocations,” and “internments.” The Japanese American Citizens League (2013) has provided guidance on more accurate terminology to describe the actions against legal immigrants and US citizens during this “period of shame” during World War II. The following are the terms of primary concern along with their proposed replacements:

• Internment/internees or evacuation/evacuees vs. incarceration/incarcerees or imprisonment/prisoners

• Relocation centers vs. American concentration camps

• Persons of Japanese ancestry / US citizens of Japanese ancestry vs. nonaliens.

However, due to the unique nature of the Honouliuli Internment and POW Camp (for housing legal immigrants and American citizens detained under martial law as well as POWs), we follow the discussion of Kurahara and colleagues (Reference Kurahara, Niiya, Young, Falgout and Nishigaya2014). Given that only a small number of Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans were detained and incarcerated, these individuals are properly referred to as “internees” or “detainees.” The camps they were held in were administered by the US Army and the Department of Justice, and they are referred to as “internment camps” or “detention camps.” However, in a general sense throughout our discussion, we use the terminology outlined above to avoid the euphemisms of the past.

SITE DESCRIPTION AND LAND USE HISTORY

The Honouliuli NHS is located on the island of O‘ahu, Hawai‘i, about 24 km (15 miles) northwest of Honolulu. Encompassing approximately 81 ha (200 acres), the site is located roughly 9.6 km (6 miles) mauka (inland) from the coast and sits within the deep Honouliuli Gulch. The Gulch varies between 150 and 215 m (500 and 700 ft.) wide at the camp location. Its steep slopes are surrounded by a relatively flat floodplain that today is mostly commercial agricultural land (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Overview of the Honouliuli National Historic Site, facing north. This is almost the same viewpoint as in Figure 3. (Photograph courtesy of William R. Belcher.)

Land Use

The Honouliuli NHS property has seen at least a thousand years of use as part of the ahupua‘a (traditional Hawaiian land division) of Honouliuli. Land divisions usually extend from the makai (seaward) areas and mauka to the uplands, allowing family groups access to agricultural lands and resources from several ecosystems. Honouliuli is Hawaiian for “dark bay” or “blue harbor,” referring to the seaward portion of this ahupua‘a. Honouliuli is one of 13 divisions of the moku (district) of Ewa, which includes the entire watershed from Honouliuli Gulch to Kaihuopalaʻai (West Loch, Pearl Harbor). Local traditions clearly associated the fishponds of Kaihuopalaʻai and mullet aquaculture as well as kalo (taro) production with this ahupuàa (Cordy Reference Cordy2002; Kane Reference Kane2011:175–184). Although we recognize the ancient Hawaiian subdivision of this ahupuàa, no definitive ancient or Native Hawaiian features or sites have yet been located within the property of the Honouliuli NHS (Basham Reference Basham, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Burton et al. Reference Burton, Farrell, Kaneko, Maldonato, Altenhofen, Falgout and Nishigaya2014).

One of the most transformative uses of the land came about through European occupation and development of the Pacific region for plantations after the 1860s, particularly for sugarcane and pineapple. Environmental, demographic, and linguistic changes occurred in response to the development of plantation and irrigation systems, catalyzed by the immigration of thousands of people from China, Japan, Okinawa, Korea, the Philippines, and other areas, who came as field laborers. These early settlers and the indigenous Hawaiians were the ancestors of many of our UH West O‘ahu students and staff, and some of our faculty.

Starting in the late 1800s, much of the Honouliuli ahupuàa was controlled by the Oahu Sugar Company and was part of the James Campbell Estate (Burton et al. Reference Burton, Farrell, Kaneko, Maldonato, Altenhofen, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Jones and Osgood Reference Jones and Osgood2015; Lodge Reference Lodge1949; MacClennan Reference MacClennan2014). The area, which includes the present-day historic site, was tied into the island-wide Waiāhole Ditch irrigation system through a tunnel structure in the southern area of the property. The Waiāhole Ditch System transported large volumes of water from the windward side of the island to the drier, leeward side of O‘ahu for sugarcane cultivation (Wilcox Reference Wilcox1997).

WORLD WAR II INCARCERATION IN HAWAI‘I

For this current discussion, the most significant historical period of the Honouliuli NHS is the Internment and POW Camp between 1943 and 1946. In the panic following the attacks on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, US citizens and resident immigrant—primarily of Japanese and Okinawan but also German, Italian, and other European nationalities—were arbitrarily suspected of disloyalty, both on the US mainland and in the Territory of Hawai‘i. The bombing of Pearl Harbor, other major US military installations, and even surrounding civilian businesses and residences in Hawai‘i was thought by the US military to be a precursor to a pending land invasion. This wartime hysteria led President Franklin D. Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which ordered the mass imprisonment of over 110,000 persons of primarily Japanese and Okinawan descent in the western United States (Falgout Reference Basham, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Falgout et al. Reference Falgout, Nishigaya, Palmero, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Scheiber and Scheiber Reference Scheiber and Scheiber2016).

Wartime incarceration in Hawai‘i, however, was both earlier and unlike that on the mainland United States. Within only a few hours of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt issued a proclamation of martial law in Hawai‘i that remained in effect until October 24, 1944. Martial law gave the US military the legal authority to arrest and incarcerate civilians (Scheiber and Scheiber Reference Scheiber and Scheiber2016).

Almost a decade earlier, the US Department of Justice / Federal Bureau of Investigation (DOJ/FBI) developed a list of civilian residents whose past or current personal ties or life circumstances linked them to “enemy groups.” Others on the list were those suspected of questionable loyalty or who were believed to have acted suspiciously. By the end of the day on December 8, 1941,some 430 local civilians were arrested. They, and others who followed, would be hastily “tried” (most without legal representation, but instead by hearing boards dominated by wartime authorities), and then held in at least 17 detention sites in Hawai‘i. Eventually, the number swelled to approximately 2,000 Japanese and Okinawan residents, plus approximately 140 of European descent. Over 300 detainees would be held at the Honouliuli Camp, which became Hawai‘i's largest and longest-used temporary incarceration camp, occupied between 1943 and 1946. Other incarcerees and POWs were held at smaller facilities throughout the islands in Hawai‘i or transferred to camps on the US mainland (Burton et al. Reference Burton, Farrell, Kaneko, Maldonato, Altenhofen, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Falgout et al. Reference Falgout, Nishigaya, Palmero, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld, Falgout and Nishigaya2014).

Mass incarceration of local Japanese, Japanese Americans, and Okinawan peoples did not occur in Hawai‘i. With their population making up around 40% of the Territory of Hawai‘i and serving as most of the labor for the plantation agricultural systems, a mass incarceration of these people would have devastated the territorial economy. As a result, 1%–2% of those populations were incarcerated, with a focus on men who were religious, political, and educational leaders, and a few women religious leaders and their assistants (Burton et al. Reference Burton, Farrell, Kaneko, Maldonato, Altenhofen, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Falgout et al. Reference Falgout, Nishigaya, Palmero, Falgout and Nishigaya2014).

Incarceration at Honouliuli

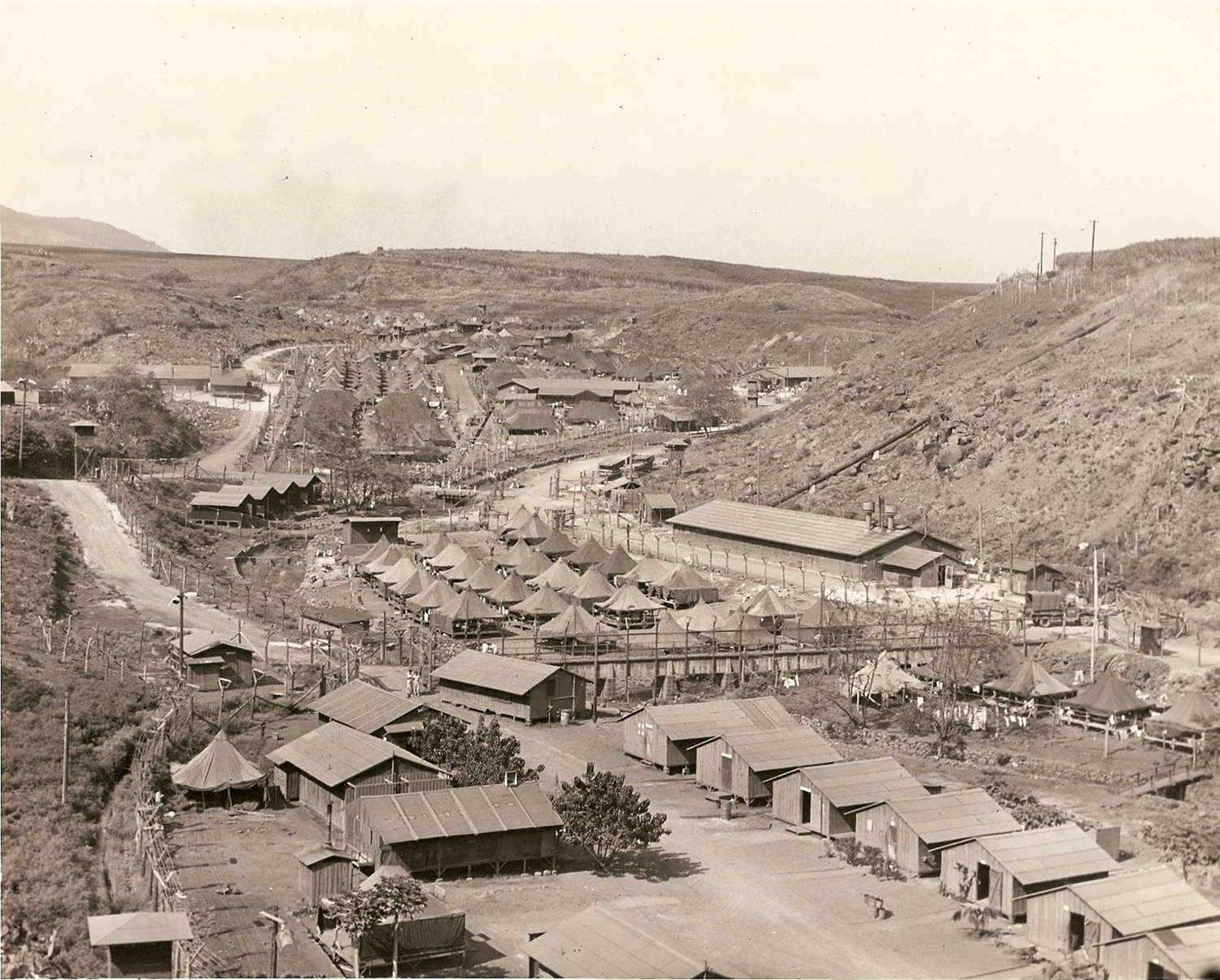

Construction of the Honouliuli Camp began in late 1942, and the camp opened on March 2, 1943. From the blueprints (US Army ca. 1943; Figure 2) and historical photographs (Figure 3), we see that the camp was composed of approximately 175 buildings, 14 guard towers, and over 400 pyramidal canvas tents. More than 300 adult civilian incarcerees were held in the central area of the camp, which was subdivided by ethnicity. The Japanese and Okinawans were held together but divided by gender. Europeans were housed as family groups.

FIGURE 2. Map overview of the Honouliuli National Historic Site. Overview of compounds and features based on map from undated US Army Corps of Engineer Sewage system blueprints (US Army ca. 1943).

FIGURE 3. Historical photograph of the middle areas of the Honouliuli National Historic Site showing the main internment compound with the main aqueduct as a dividing area between components of the internees (to the south) and the prisoners of war (to the north). (R. H. Lodge Collection, Hawaii Plantation Villages.)

Honouliuli was also the largest of at least 13 POW camps in Hawai‘i, holding captured soldiers, labor conscripts, and a few individuals who were simply in the “wrong place at the wrong time” when seized. Honouliuli held nearly 4,000 POWs (of the estimated more than 16,000 total in Hawai‘i), but not all were present in the camp at the same time. The largest group imprisoned were Okinawans, but the camp also held relocated Italians, Koreans, Japanese, and a few Filipinos. Japanese POWs were considered to be dangerous, and the US officials sent most of them to other Allied nations or to mainland POW camps. Most of the Japanese POWs sent to Hawai‘i were subsequently transferred to the mainland (Burton et al. Reference Burton, Farrell, Kaneko, Maldonato, Altenhofen, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Chinen Reference Chinen, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Dakujaku Reference Dakujaku2016; Falgout Reference Basham, Falgout and Nishigaya2014). The all-male POW areas were subdivided by ethnicity, with the Japanese eventually separated from the Okinawans. The Japanese section was also subdivided by military rank. The largest Japanese POW holding area was in the northernmost Compound I. Smaller areas in the southernmost region (Compound VII and possibly Compound VIII) were used for Korean POWs (Ch'oe Reference Ch'oe2009).

Little is known of the closing and dismantling of the camp, although photographs from 1948 show a relatively denuded valley with many of the concrete facility platforms still visible. In 1958, the land was leased to a local rancher, who planted the guinea grass for use as fodder to sustain livestock. Archaeological features such as corrals and chicken coops, as well as the bones of horses and cows, have been found in several areas of the property.

REDISCOVERY AND RESEARCH

Hidden deep within Honouliuli Gulch, the Honouliuli NHS lay largely forgotten after its official closure in 1946. The site was only rediscovered by chance in 1998 by members of the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i (JCCH; Kurahara et al. Reference Kurahara, Niiya, Young, Falgout and Nishigaya2014). The University of Hawai‘i's involvement began in 2009, at the invitation of the Society for Hawaiian Archaeology (SHA) and the JCCH. The brief, initial site exploration conducted by Drs. James Bayman (University of Hawai‘i–Mānoa), Jeffrey F. Burton, and Mary M. Farrell also included several UH West O‘ahu students as volunteers. UH West O‘ahu was encouraged to begin in-depth research on this site, including several summer archaeological field schools.

The rediscovery of this little-known site generated tremendous interest, especially within the local Hawai‘i community. As a result, the early field schools were supported with funding from a wide variety of sources: the NPS's Japanese American Confinement Sites (JACS) grants program, Pacific Historic Parks, and UH West O‘ahu grants and stipends. An oral history and archival research program was funded by a JACS grant, which formed the core of the edited volume Breaking the Silence (Falgout and Nishigaya Reference Falgout and Nishigaya2014). UH West O‘ahu received funding for student scholarships from the Valor in the Pacific National Monument, the University of Hawai‘i Foundation, and several local foundations and private donors. Previous survey reports for Honouliuli provided the NPS with information such as archaeological base maps, feature descriptions, and historical background information, but they were focused primarily on the interment portion of the Honouliuli NHS—especially those areas associated with Japanese and Okinawan incarcerees—as well as the administrative areas (Burton and Farrell Reference Burton and Farrell2008, Reference Burton and Farrell2009; Farrell and Burton Reference Farrell and Burton2012). In 2012, Burton and Farrell submitted a National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) Registration Form for Honouliuli that culminated in a Special Resource Study and Environmental Assessment of the camp property (National Park Service [NPS] 2015).

The key purpose of the UH West O‘ahu archaeological field schools was to conduct research and provide training for students. The educational goals were focused on introducing students to basic archaeological methods, expanding their knowledge of World War II incarcerations that included civilian incarcerees and POWs, as well as the social impacts in Hawai‘i of the civilian incarceration (Figure 4). Specific goals over the four years of the field schools varied, but they focused on parcel survey and documentation, artifact collection, and excavation of a POW mess hall area in the northern part of the property (Belcher Reference Belcher2018, Reference Belcher2019a, Reference Belcher2019b, Reference Belcher2021).

FIGURE 4. Student of the 2019 field school at the excavation of Feature I-7, a possible prisoners of war mess hall platform (concrete). (Photograph by William R. Belcher.)

COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY OF INCARCERATION ON O‘AHU

Community archaeology began as a form of research and community outreach associated with cultural resource management studies. This form of community engagement originated in the 1970s to engage the general lay public, but it quickly began to engage the descendant populations to assist in archaeological data collection as well as the understanding and interpretation of the archaeological record (e.g., Colwell Reference Colwell2016; Derry and Malloy Reference Derry and Malloy2003; Marshall Reference Marshall2002; Moyer Reference Moyer2015; Samuels and Daugherty Reference Samuels, Daugherty and Samuels1991). For our purposes, the most important contribution to community archaeology of incarcerees is the work of Burton (Reference Burton2017).

Burton (Reference Burton2017) summarizes a long history of collaboration with descendant and local communities around the Manzanar National Historic Site in California. By drawing on intimate stories, local knowledge, and personal connections to the region and the Manzanar Camp, Burton and colleagues created a rich tapestry for the interpretation of life in and outside of Manzanar. This raised an awareness that allows visitors and the next generation of park goers to connect with the interpretations and understand the importance of public participation. Active collaboration also included the archaeology of Japanese gardens (modifying the landscape), the use and creation of barracks basements (playing cards, making sake), playing baseball, the activities of the administration officials and their families, and stories that the local community wanted to be told.

The University of Hawai‘i West O‘ahu serves the western side of the island of O‘ahu, including a large Indigenous population. It embraces Native Hawaiian culture and traditions while promoting the success of students of all backgrounds. The campus fosters excellence in teaching, learning, and service to the community while being a premier, comprehensive, Indigenous-serving institution dedicated to educating students to be engaged global citizens and leaders in society. These goals of the university fit well with the mission of the archaeological field school, and the students (of many ethnic backgrounds) took to the site as “their own.” They embraced the history and archaeology, and they attempted to understand the broken promises to these US residents and citizens during World War II and the earlier colonial period.

How did the populations of Native Hawaiians and Asian immigrants fit into the archaeology of this “place of shame”? One important expansion of archaeological understanding and connection comes from involving descendant populations through archaeological work and material culture. Although several incarcerees were still living at the time, very few of their children or grandchildren were involved in the archaeological field school. Additionally, although people of Japanese and Okinawan heritage comprised 40% of the population of the territory during World War II, today they are make up only about 17% of Hawai‘i's population. Like many residents of Hawai‘i, most of our students, despite their Japanese and Okinawan heritage, had never heard of the Honouliuli NHS. They knew that there had been camps on the mainland, but they did not know about the extent of the incarceration in the Territory of Hawai‘i. In addition, many of the incarcerees had been placed in mainland camps (where they could live as families), and they never returned to the Islands. Finally, after release, many of the incarcerees would not talk about their experiences due to the stigma of having been incarcerated. This was based on the idea that since not everyone had been imprisoned, those who had been incarcerated must have done something “wrong” (Adler Reference Adler, Falgout and Nishigaya2014; Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i 2012; Sato and Harada Reference Sato and Harada2018; Tsuru Reference Tsuru, Falgout and Nishigaya2014).

To create an encompassing learning experience for our students, we worked with several community partners, particularly the NPS, Pacific Historic Parks (PHP), the JCCH, the Hawaii Korean Cultural Center (HKCC), the Hawaii Okinawa Center, and the King Kamehameha V Judicial History Center. Each entity brought a unique contribution to the pedagogy related to social justice, democratic principles, and the wrongful imprisonment of legal immigrants and US citizens. Through those community resources and partnerships, we expanded the students’ understanding of how the archaeological field techniques segued into an understanding of the site's importance to social justice. Contextualization of incarceration and POW imprisonment within its broader sociopolitical context were also emphasized through experiential learning in field trips to the NPS Valor in the Pacific Memorials and to exhibits at the JCCH and the King Kamehameha V Judicial History Center. Field trips were conducted in a rough chronological order to allow the students to develop a deeper understanding of the social and cultural events that led up to the targeted incarceration on O‘ahu.

For those students who had relatives, friends, or members of their own ethnic groups who had been held in a variety of camps, or who had participated in some other way with the incarceration, these visits helped forge a personal connection to the story of World War II. Also, connections were forged due to ethnicities of the students and faculty that overlapped with those of the POWs who were held in the camp (e.g., Korean, Filipina/Filipino, and Okinawan).

National Park Service and Pacific Historic Parks

Field Schools

The Honouliuli NHS is maintained and overseen by the NPS as part of the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument. Consequently, no fieldwork would be possible at this important site without their involvement. Although funding for earlier field schools had been provided in part through the NPS's JACS grant program, more recent NPS engagement focused on the use of the Hawaiʻi Pacific Islands Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (HPI CESU, or CESU) as a partnership and funding agreement. Pacific Historic Parks (PHP) is a nonprofit 501(3)c organization that provides support and education related to four national parks, one state park, and one historical site (Honouliuli NHS). The 2016–2019 field schools were supported by an HPI CESU P14AC00637, Task Agreement P16AC0172.

The CESU is a national network that provides research, technical assistance, and education to federal agencies to support better stewardship of natural and cultural resources, with the HPI CESU being regionally specific. This process links federal agencies to a nonfederal partner to accomplish a specific agreed-upon project. These programs must include substantial involvement of the federal agency, and the project must show a public purpose. With this CESU, the NPS provided professional support and oversight as well as training in the principles and standards of the NPS archaeology program, particularly in relation to data collection, input, and management. Public presentations provided UH West O‘ahu and the NPS with an opportunity to share new information directly with the wider public, who cannot yet access the site.

The PHP also provided internship programs that supported the university's senior capstone experiences, as well as real-world training in federal and nongovernmental organization (NGO) experience in cultural resource stewardship, historical research, and management. A large part of PHP involvement in the field school was initiating outside volunteer help.

This support of NPS and PHP offered students an educational opportunity that gave them experience in archaeological field techniques and enhanced their prospects for obtaining locally applicable field experience that would improve their eligibility for employment opportunities both on the island or in the federal government.

Field Trips

All the monuments associated with the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor are part of the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument system. The USS Arizona and USS Utah Memorials include remnants of the actual vessels (which are under jurisdiction of the US Navy), which are still lying where they sunk. However, the USS Utah is relatively inaccessible to individuals who do not have military base access to the Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam (Ford Island). The USS Arizona Memorial complex has a superb museum that displays the buildup to World War II, including the attack on Pearl Harbor. Adjacent to the USS Missouri battleship on Ford Island is the USS Oklahoma Memorial, an abstract vision of the battleship with its crew in formation on the deck “manning the rails,” honoring the 429 sailors and US Marines who died that day.

Besides offering a view of the remnant of a battle that instigated the incarceration, these field trips also encouraged students to think about the ethics and politics of replacing indigenous names with anglicized versions (i.e., Pu‘uloa versus Pearl Harbor). The field trips to the USS Missouri and USS Bowfin Submarine Museum provided opportunities to examine the representation of the parties or actors in the historical narrative. For example, the USS Missouri's primary representation is as the site of the US victory over Imperial Japan (where the surrender documents were signed), but it does not recognize its participation in the bombardment of Okinawa, where between one-quarter and one-third of the island's population was killed. Similarly, the USS Bowfin Submarine Museum mentions the record of success in the sinking of the ship Tsushima Maru, but it does not consider the fact that the passengers killed included several hundred Okinawan schoolchildren who were trying to escape to the main islands of Japan.

Finally, a broader goal of the project was to expand the national understanding of the abrogation of civil liberties that occurred in the United States and its territories during World War II. The project laid the groundwork for this effort through NPS presentations that discussed and interpreted incarceration. Presentations by Dr. Jadelyn Moniz-Nakamura in a classroom setting maximized opportunities for discussion among peers and for preparation for the field portion of the project. The discussions highlighted World War II activities across the Hawaiian Islands. The objective was to instill a sense of place and meaning for students prior to entering the site. It was hoped that as students entered the Honouliuli NHS and encountered the physical remnants of the past, coupled with the physical isolation and history of the place, their experiences would provide them with a more fully informed encounter.

Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i

The JCCH was chartered in 1987 with the mission of educating and expanding the understanding of the Japanese experience in Hawai‘i associated with immigration and agricultural and civic contributions, and especially how that experience changed with the events of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Exhibits

The exhibits at the JCCH display the entire sequence of Japanese immigration to the Kingdom of Hawaii, beginning in 1868 with the gannenmono, or first arrivals. These individuals began the tradition of immigration to supply labor for the intensive agricultural plantations of sugarcane and pineapple. The exhibit goes through the development of racial discrimination and the lead up to the incarceration of World War II.

Archives

The JCCH houses the Tokioka Heritage Resource Center, one of the largest extant archives related to the Honouliuli NHS, which includes oral histories/interviews, memory maps, archival documents, photographs, and artifacts. Students visiting the archives were able to see tangible memories of incarcerees and artifacts associated with their incarceration (such as jewelry made from toothbrush handles). UH West O‘ahu student interns also worked at the JCCH as part of their senior capstone projects.

Volunteers and Activism

As discussed above, the JCCH was instrumental in rediscovering the site and in funding the initial fieldwork by Burton and Farrell (Reference Burton and Farrell2012), which became the basis for the nomination of the site to the NRHP. The JCCH has worked with volunteers to conduct tours at the Honouliuli NHS and has a long history of activism associated with expanding the visibility of this archaeological site. Prior to 2016, access to the site was gained through a paved road, and the JCCH members volunteered for fieldwork on a regular basis. Thereafter (due to changing land use agreements between UH West O‘ahu and Bayer of Hawai‘i née Monsanto Hawaii), access was only available via an unimproved road with an arduous walk over rough and steep terrain. This situation made participation difficult for many of the elderly volunteers and docents of the JCCH. However, they maintained their enthusiasm to hear about our results every year.

Hawaii Korean Cultural Center

The Hawaii Korea Cultural Center helps to recognize the contributions of Korean immigrants to the Kingdom of Hawai‘i. Its primary interest in the Honouliuli NHS was the presence of Korean POWs, who were held in the southern areas of the camp. These POWs were part of the Japanese military, primarily as nonconsenting conscripts, and they were captured throughout the Pacific theater during World War II (see Cho'e Reference Ch'oe2009).

Hawaii Okinawa Center

The Hawaii Okinawa Center, administered by the Hawaiian United Okinawa Association, opened in 1990 to celebrate the ninetieth anniversary of the first Okinawan immigrants to Hawaii in 1900. One UH West O‘ahu senior served as an intern as part of her senior capstone project.

King Kamehameha V Judiciary History Center

This center is housed on the first floor of the Ali‘iolani Hale (the former capitol building of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i) and was founded in the 1970s to provide learning opportunities related to Hawai‘i‘s legal systems from pre-European to modern times. Through static displays, reproductions of houses, and detailed video presentations, the Martial Law exhibit at the King Kamehameha V Judiciary History Center offers a glimpse of island life during World War II, particularly the period of martial law.

DISCUSSION

Because of UH West O'ahu's location and the community partnerships, the involvement of its faculty in the multidisciplinary research seemed natural. As local residents of Hawai‘i, people of Native Hawaiian ancestry or of Japanese or Okinawan heritage, and family members of individuals who had been incarcerated at the Manzanar War Relocation Center in California, the 10 members from seven different academic disciplines (anthropology, economics, English, Hawaiian studies, history, psychology, and sociology) each had unique ties to the story of World War II incarceration (Burton Reference Burton1996).

Democratic Principles and Social Justice

The faculty quickly discovered that the UH West O‘ahu staff and students, whose backgrounds overlapped with those incarcerees and POWs held at the camp, had a wide variety of direct and/or indirect ties to the story of World War II incarceration. Summer field schools not only taught our students archaeological methods but also allowed them to focus on an aspect of the site relevant to their own backgrounds or interests, including floral and faunal aspects of the property, analysis of historic artifacts outside of the fieldwork, and comparison to other US concentration camps. Several students from the US mainland and abroad participated in the field school.

Research efforts over the years have been propelled by the Honouliuli NHS's inherent significance as well as its relevance to the local Hawai‘i community. The larger story of the Honouliuli NHS, especially with the discovery of the wide range of peoples held and differences in treatments experienced by different ethnic categories of incarcerees and POWs, holds significant lessons about democratic principles and social justice. It teaches about the dangers of xenophobia and prejudice, especially during times of fear and chaos that can accompany the threat of attack. It highlights the value of global perspective, cross-cultural understanding, and mutual respect in international relations. It promotes reflection on the broader issues of our shared humanity and the need for justice and peace around the world today.

Recruitment of faculty into the research component included such scholars as Dr. J. Leilani Basham, whose research provided the Hawaiian pre-European history of the westside moku and ahupua‘a of Honouliuli. Her extensive knowledge as a kumu hula and ‘olelo Hawai‘i (teacher of Hawaiian dance and language) helped us to see beyond the US culturally biased focus on democratic principles and to expand our exploration of social justice, given that Indigenous Hawaiian society was not a democracy but did emphasize mutual responsibility within social justice.

The faculty of UH West O‘ahu continued to developed course sections and even whole courses that focused on research findings about the Honouliuli NHS. Later, a 21-credit multidisciplinary program called the Certificate in Democratic Principles and Social Justice was developed. The archaeological summer field school efforts continued with formal collaboration with the NPS until 2019.

Different components of the certificate program included original, collaborative research by faculty and students; collection of materials (oral histories, documents, artifacts); and education on the topics of democratic principles and social justice (see Supplemental Text 2). The curriculum required background in both theory and methodology, plus relevant courses focused on “The Local Context” of these issues (in the United States, Hawai‘i, Asia, and/or the Pacific; see Supplemental Text 3). They also required students to complete courses that addressed wider applications, such as those that addressed colonialism, conflict, and globalization; development, labor, and law; and/or race, class, gender, and sexuality. Students also gained firsthand experience in community outreach and service activities and in advocating for the rights of others at local, national, regional, and international levels. The primary goals were for students to learn from the past and act as informed citizens to develop new ways of advancing these important tenets of US society. In addition, students were also encouraged to participate in relevant NPS student conservation and volunteer programs as well as study abroad programs.

One of the main thrusts in curriculum development was related to ethical reasoning (Vasquez et al. Reference Vasquez, Andre, Shanks and Meyer2015) because facts (in this case, tangible archaeological observations) intersect with values. Consequently, ethical reasoning involves examining one's perspective from a variety of approaches, including the following five:

(1) The “Utilitarian” approach, which identifies costs and benefits in the determination of ethical action;

(2) The “Rights” approach, which locates some basic rights of individuals (e.g., privacy, truth) and asserts that such rights be uniformly applied;

(3) The “Fairness” or “Justice” approach, which identifies and stresses notions of equality and/or equity and nondiscrimination;

(4) The “Common Good” approach, which emphasizes both the distribution of resources in society and the interconnection between and among individuals or subgroups in society;

(5) The “Virtue” approach, which focuses on ideals or characteristics for which citizens should strive.

This certificate included specific courses related to the peoples of Hawai‘i. These courses included discussion of issues related to the transformation of the Indigenous peoples, landscape changes related to colonization, development of new economic systems (such as plantation-based agriculture of sugarcane and pineapple), development of an ethnically stratified labor force (and corporate development), and hotel and tourism development.

Since at least 1998, archival collections and research as well as the collection of oral histories have been spearheaded by the JCCH. The multidisciplinary oral history and archival work of the UH West O'ahu team, which commenced in 2008, culminated in the publication of Breaking the Silence: Lessons of Democracy and Social Justice from the World War II Honouliuli Internment and POW Camp in Hawai‘i (Falgout and Nishigaya Reference Falgout and Nishigaya2014). The UH West O‘ahu collection of materials is being curated in the James and Abigail Campbell Library. Graduate student research at the University of Hawai‘i–Mānoa combined archaeological and archival study in several master's theses (e.g., Dakujaku Reference Dakujaku2016) and one dissertation (Tatsomi Jo Ann Sakaguchi, Hawai'i English Language Program, University of Hawai'i Mānoa, in progress).

The creation of the archaeological field school at UH West O‘ahu provided an opportunity for students to understand the physical manifestations of the fear and paranoia that overtook the United States after the attack on Pearl Harbor. With the tangible remnants of sewage lines, mess hall platforms, showers, pit latrines, World War II–era equipment, and earlier remnants of plantation irrigation systems, the story of the precursor to and aftermath of the incarceration of Americans and legal immigrants resonated with the students, many of whose family members were directly affected by President Roosevelt's invocation of martial law in Hawai‘i and/or Executive Order 9066 on the US mainland.

After the publication of Breaking the Silence (Falgout and Nishigaya Reference Falgout and Nishigaya2014), many of the consortium members ended their research programs due to time constraints related to teaching or administrative duties as well as movement away from UH West O‘ahu. Falgout and Chinen, the two leads on both the research and Certificate in Democratic Principles and Social Justice, retired in 2015 and 2017, respectively. Without these two individuals to recruit students for the certificate program, the Social Sciences Division voted to eliminate the certificate as part of the curriculum offerings, effective spring 2018. As of March 2020, the archaeological fieldwork portion of the HPI CESU agreement with UH West O‘ahu reached the agreement terminus. However, the Anthropology Concentration is now working to continue another HPI CESU, primarily based on the development of story maps and an online “museum” experience—an effort led by Dr. Christy Mello (Reference Mello2021).

In our experience, today's students seek out socially relevant experiences, regardless of disciplinary focus. Archaeology can appear very formulaic and technical, so we, as instructors, need to find ways to create connections between the archaeological record and the lives of our students—beyond inherent interest or the reconstruction of cultural lifeways. With the importance of current sociopolitical movements, such as Black Lives Matter or anti-racism awareness for Asians and Pacific Islanders, it behooves us to attempt to engage students. It is important to show how anthropology can be relevant to student populations from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds.

The following are some of the takeaway points for instructors:

(1) Anytime we can connect local populations to the past populations of an archaeological site, our understanding of the archaeological record is enhanced.

(2) Field trips beyond the excavation give students temporal, social, and cultural contexts for the materials they are excavating or surveying.

(3) Whereas historical sites tend to lend themselves to the examination of issues related to social justice and democratic principles, literature and museum displays can provide an opportunity to critically examine the portrayal of native populations and the role of descendant populations (in general) in understanding the precolonial archaeological record.

(4) Museum and online displays are a significant source of understanding social justice, even with precolonial archaeological materials. What story is trying to be told? Do we know of any aspects that are being left out to promote (or negate) a certain narrative?

CONCLUSION

Although the Certificate in Democratic Principles and Social Justice emerged from the results of the Honouliuli Field School, its seeds—recruitment of the faculty and the diversity of disciplines participating in the Honouliuli research—can be traced back to the UH West O‘ahu's institutional changes in the first decade of the twenty-first century. The certificate and research agenda changed the face of the university for almost a decade.

One student, R. Kalani Carriera, was supported by the HPI CESU as a field school student in 2016 and as a paid research assistant in 2017. In his words,

Honouliuli was unique among the internment camps that spread across the United States following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. It was the only camp that separated families, choosing and segregating many of the prominent male members of the Japanese American community here in Hawai‘i to be imprisoned. To be at a site so important in both Hawaii's and the United States’ history was, at the very least, an incredible experience. As a Native Hawaiian and a descendant of Japanese lineage, working at Honouliuli still holds a special significance to me.

As a student, being able to use classroom-learned archaeological techniques in real-time fieldwork applications was invaluable. Being in a historical space, physically working on sites and features, feeling the heat of Jigoku-Dani, makes Honouliuli's history tangible, current, and relevant.

Later, as a student research assistant, I was given two tremendous opportunities. First, I had the privilege of guiding students, passing on Honouliuli's legacy to the next generation of anthropologists. Second, I had the honor of working with the National Park Service, locating and documenting sites and features for the purposes of developing an action plan to someday turn Honouliuli into a working visitors’ park. This part of my experience is a future imperative as I feel Honouliuli's history needs to be shared with the general public, educating generations about its place within the context of WWII and U.S. History.

For over a decade, the archaeological field school at Honouliuli National Historic Site held the interest of students both academically and because of its connection to their own personal heritage and family history. Additionally, it helped form a major component of two academic certificates—forensic anthropology and democratic principles and social justice.

Not only did students learn the basic skills of the archaeological field research component, but through formal lectures and informal discussions in the field during lunch, they gained an understanding of this site and its unique position in American history at large and Hawai‘i history in particular. The students walked away with a better understanding of the historical circumstances of wartime paranoia that led to the incarceration of US citizens. This continues to be important due to the fact that many of principles of social justice and democratic principles that we hold dear are again being challenged by incidents in our political and social environments, both nationally and globally.

Acknowledgments

The authors represent a wide range of individuals involved in the UH West O‘ahu field schools, but we would like to thank our colleagues over the years within the Social Sciences Division and Humanities Division at UH West O‘ahu, including Drs. Orlando Garcia Santiago, Jennifer F. Byrnes, Alan Rosenfeld, Susan Adler, and Christina Mello. Mr. Alphie Garcia is the Honouliuli Archive Collections manager at the UH West Oahu Library. Facilities, Security, and the Business Office at the Kapolei campus were amazing in facilitating the field school and addressing its various issues pertaining to transportation and logistics. The Chancellor's Office at UH West O‘ahu always provided incredible support for this project over the years, particularly Gene Awakuni, Rockne Freitas, Doris Ching, and Maenette Benham. We would also like to thank the leadership of World War II Valor in the Pacific, including then Park Superintendent Jacqueline Atwell, Katie Bojakowski, and Jade Ortiz-Nakamura. The education and docent staff of the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i, particularly Jane Kurahara, Betsy Young, and Brian Niiya (now of the Densho Encyclopedia Project), were extremely important in the students’ understanding of the Japanese experience in Hawai‘i. The King Kamehameha V Judicial History Museum staff kindly arranged a full tour of their Martial Law exhibit for the students each year and took time out of their busy day to guide us through this difficult period in Hawai‘i's history. Finally, we want to thank Drs. Jeff Burton and Mary Farrell for their diligence in documenting the World War II internment story for the islands of Hawai‘i (and elsewhere!) and for all of their original survey work for Honouliuli National Historic Site. Without their vision, none of this would have been possible. There are many other scholars who participated in community and academic lectures as well as numerous academics and administrators in the UH West O‘ahu. The authors apologize for not being able to acknowledge everyone's contribution to the development of this research program. Ms. Anna Riddells provided the Spanish translation of the abstract.

All fieldwork between 2016 and 2019 was supervised by William R. Belcher (at the time, assistant professor in the Social Sciences Division, UH West O‘ahu), with field assistance provided by Johanna Fuller, former resource specialist with Pacific Historic Parks. Additional field training and project oversight was provided by Jadelyn Moniz-Nakamura, integrated resource manager at Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Historic Site, who served as the agency technical representative on the HPI CESU Task Agreement. Initial logistical support and spatial resources were provided by Rebecca Rinas, planner at HNHS in 2016 and 2017; Ms. Rinas also served as project manager for the 2017 field school. Fieldwork was conducted by various student classes during the formal summer field schools from 2016 to 2019 and by volunteer groups during the interim periods between classes. These volunteers were composed of various citizen and veterans groups as well as students.

Data Availability Statement

No original data were presented in this article.

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2021.23.

Supplemental Text 1. Archaeological Field Techniques Syllabus.

Supplemental Text 2. Certificate in Democratic Principles and Social Justice.

Supplemental Text 3. Micronesian Cultures Syllabus