Introduction

Globally, access to substance use (SU) interventions remains limited, largely due to a lack of trained mental health providers (Bruckner et al., Reference Bruckner, Scheffler, Shen, Yoon, Chisholm, Morris, Fulton, Dal Poz and Saxena2011). The gap between the behavioral health care need and available services has led to the development of innovative delivery models, including task sharing, or the distribution of behavioral health care tasks to non-specialist workers (Hoeft et al., Reference Hoeft, Fortney, Patel and Unützer2018; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Raviola and Patel2018). The degree to which users of these interventions view them as acceptable (satisfactory in terms of content and complexity), feasible (practical to deliver), and appropriate (useful for their setting), is key to service users’ uptake and engagement in the intervention and providers’ continued implementation of the innovation (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger, Griffey and Hensley2011, Reference Proctor, Powell and McMillen2013; Mira et al., Reference Mira, Soler, Alda, Baños, Castilla, Castro, García-Campayo, García-Palacios, Gili, Hurtado, Mayoral, Montero-Marín and Botella2019). Yet, there remains a relative lack of evidence on patient and provider perspectives on the implementation outcomes of SU interventions delivered via task-sharing in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This represents a barrier to further intervention adaptation for scale up of services.

Further understanding patient and provider perspectives on the implementation outcomes of existing interventions may help inform future adaptations and intervention development. Within countries like South Africa, it is particularly important to understand perspectives on intervention components that are helpful for people living with HIV (PLWH). South Africa has the largest number of PLWH globally, more than 7.5 million (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Tanser, Tomita, Vandormael and Cuadros2021). There is also a high prevalence of SU problems among PLWH in the country (Kader et al., Reference Kader, Seedat, Govender, Koch and Parry2014; Necho et al., Reference Necho, Belete and Getachew2020), which has led to the development of interventions to target both psychological and health outcomes within this population (Kekwaletswe and Morojele, Reference Kekwaletswe and Morojele2014; Myers et al., Reference Myers, Joska, Lund, Levitt, Butler, Naledi, Milligan, Stein and Sorsdahl2018; Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Joska, Myers, Belus, Regenauer, Andersen, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2020b).

Prior research has documented far more intervention packages than intervention components, meaning many intervention packages actually utilize similar components in various configurations (Domhardt et al., Reference Domhardt, Geßlein, von Rezori and Baumeister2019; Boustani et al., Reference Boustani, Frazier, Chu, Lesperance, Becker, Helseth, Hedemann, Ogle and Chorpita2020). Therefore, there may be a greater value from examining the implementation outcomes of individual components than of the overall packages. Examining the implementation outcomes of specific components may lead to actionable findings not only relevant to that intervention package but also to others that include the same component. Examining how specific components are perceived may also help in developing more streamlined or personalized interventions. Moreover, when examining patient and provider perspectives on interventions, qualitative and quantitative data may add different information and be best used in combination (O'Cathain et al., Reference O'Cathain, Murphy and Nicholl2010).

In addition to adequately understanding perceptions of interventions and their components, it is important to understand perspectives on delivery models. Peer delivery models, in which an individual with lived experience of a condition delivers the intervention, are becoming increasingly common in high-income countries, particularly for SU interventions (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Carusone, Craig, Telegdi, McCullagh, McClure, Wilson, Zuniga, Berney, Ginocchio, Wells, Montess, Busch, Boyce, Strike and Stewart2019; Shalaby and Agyapong, Reference Shalaby and Agyapong2020). Yet few studies in LMICs have used peers to deliver task-shared interventions. Consequently, there is a knowledge gap on patient and provider perspectives of the acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of peer-delivered SU interventions in these settings (Satinsky et al., Reference Satinsky, Kleinman, Tralka, Jack, Myers and Magidson2021).

In a pilot randomized type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial of Khanya, an integrated, peer-delivered, behavioral activation (BA) and problem solving-based intervention to address SU and HIV medication adherence, participants experienced significant improvements in ART adherence compared to enhanced treatment as usual (Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Joska, Belus, Andersen, Regenauer, Rose, Myers, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2021). Participants also reported very high levels of acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of Khanya on a quantitative assessment (M = 2.98/3 for both feasibility and acceptability; 2.94/3 for appropriateness (Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Joska, Belus, Andersen, Regenauer, Rose, Myers, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2021). The current study presents the primary qualitative aim of this trial (Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Joska, Belus, Andersen, Regenauer, Rose, Myers, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2021) in which we examine patient and provider perspectives on the feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness of Khanya as an overall intervention and its delivery by a peer. Using mixed methods to triangulate qualitative and quantitative data, we also examine patient perspectives on specific intervention components (i.e. Life-Steps, BA, mindfulness training, relapse prevention strategies). Findings may aid future adaptations of Khanya and/or interventions using similar components.

Methods

Participants and procedures

As reported on previously (Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Joska, Myers, Belus, Regenauer, Andersen, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2020b, Reference Magidson, Joska, Belus, Andersen, Regenauer, Rose, Myers, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2021), a pilot randomized hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation trial (N = 61) was conducted to evaluate the Khanya intervention package; between August 2018 and October 2019, 30 participants were randomized to receive Khanya, and 31 participants to receive enhanced treatment as usual (facilitated referral to a local SU treatment program). Participants were recruited from a large, public primary care clinic in Cape Town. Participants were eligible for the trial if they were: (1) on antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV; (2) 18 to 65 years old; (3) reported at least moderate SU; (4) and had ART non-adherence in the past three months. For additional detail on Khanya's development and clinical outcomes, please see prior publications (Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Joska, Regenauer, Satinsky, Andersen, Seitz-Brown, Borba, Safren and Myers2019, Reference Magidson, Andersen, Satinsky, Myers, Kagee, Anvari and Joska2020a, Reference Magidson, Joska, Myers, Belus, Regenauer, Andersen, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2020b, Reference Magidson, Satinsky, Luberto, Myers, Funes, Vanderkruik and Andersen2020c, Reference Magidson, Joska, Belus, Andersen, Regenauer, Rose, Myers, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2021). Data used in the current study aim were collected at visits conducted at three- (post-treatment) and six- (follow-up) months after baseline. All procedures were approved by the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 187/2018) using an IRB Authorization Agreement (IAA) with the University of Maryland College Park.

Khanya intervention

Khanya was delivered by a single local peer interventionist with shared lived experience of SU and prior training in BA, over six sessions in a three-month period. Khanya included intervention components selected on two main criteria: (1) prior empirical support for improving both ART adherence and reducing substance use; and (2) feasibility of delivery by non-specialist health workers. These components included problem-solving strategies, BA, mindfulness training, and relapse prevention strategies. Each had also previously been delivered in isolation, in briefer interventions, and/or integrated with other skills (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Magidson, O'Cleirigh, Remmert, Kagee, Leaver, Stein, Safren and Joska2018; McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Elkonin, de Kooker and Magidson2018; Myers et al., Reference Myers, Petersen-Williams, van der Westhuizen, Lund, Lombard, Joska, Levitt, Butler, Naledi, Milligan and Stein2019; Safren et al., Reference Safren, O'Cleirigh, Andersen, Magidson, Lee, Bainter, Musinguzi, Simoni, Kagee and Joska2021). These were then adapted for the setting based on key stakeholder input (Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Joska, Regenauer, Satinsky, Andersen, Seitz-Brown, Borba, Safren and Myers2019, Reference Magidson, Andersen, Satinsky, Myers, Kagee, Anvari and Joska2020a, Reference Magidson, Joska, Myers, Belus, Regenauer, Andersen, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2020b, Reference Magidson, Satinsky, Luberto, Myers, Funes, Vanderkruik and Andersen2020c; Belus et al., Reference Belus, Rose, Andersen, Ciya, Joska, Myers, Safren and Magidson2020). The intervention manual was structured as a two-sided flipchart, providing the interventionist with reminders on key content and participants with visual aids (please contact authors for a copy).

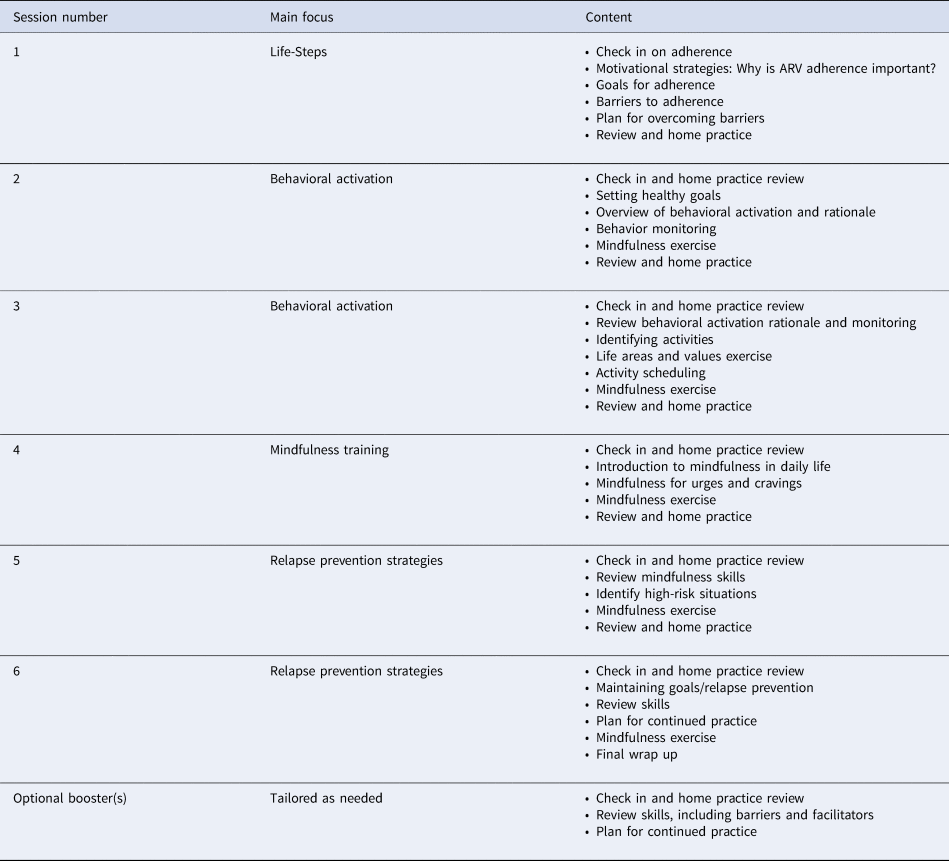

Khanya intervention components. Khanya begins with problem-solving strategies to address ART adherence using a single-session problem-solving intervention [‘Life-Steps,’ previously adapted for the South African context, (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Magidson, O'Cleirigh, Remmert, Kagee, Leaver, Stein, Safren and Joska2018)]. Specifically, participants (a) identify an adherence goal, (b) identify barriers to reaching the goal, and (c) create a plan and a back-up plan to support their goal (Safren et al., Reference Safren, Otto and Worth1999). It was developed to help support ART adherence among men living with HIV in the United States and has frequently been integrated with other interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy for depression (Safren et al., Reference Safren, Bedoya, O'Cleirigh, Biello, Pinkston, Stein, Traeger, Kojic, Robbins, Lerner, Herman, Mimiaga and Mayer2016, Reference Safren, O'Cleirigh, Andersen, Magidson, Lee, Bainter, Musinguzi, Simoni, Kagee and Joska2021). Life-Steps was further adapted for Khanya so that participants set a SU goal and to include a focus on how SU interfered with adherence (Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Joska, Myers, Belus, Regenauer, Andersen, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2020b), following prior work that has used problem solving to improve both ART adherence and SU in South Africa (Myers et al., Reference Myers, Petersen-Williams, van der Westhuizen, Lund, Lombard, Joska, Levitt, Butler, Naledi, Milligan and Stein2019). BA increases awareness of individual's daily activities, behavioral patterns, and the links between mood, cravings and behavior, with a focus on increasing participation of value-driven, substance-free rewarding activities (Daughters et al., Reference Daughters, Magidson, Anand, Seitz-Brown, Chen and Baker2018). BA has previously been adapted and implemented in South Africa using task sharing (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Magidson, O'Cleirigh, Remmert, Kagee, Leaver, Stein, Safren and Joska2018). Mindfulness training aims to increase awareness of the present moment with the aim of cultivating nonjudgmental awareness of negative affective states and reducing emotional avoidance (Miller, Reference Miller1999). In Khanya, this includes both formal and informal mindfulness exercises that had been adapted to the South African context to promote feasibility and acceptability (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Elkonin, de Kooker and Magidson2018). Finally, relapse prevention strategies focus on the identification and navigation of high-risk situations (e.g. friends encouraging SU) (Marlatt and Gordon, Reference Marlatt and Gordon1985) and specific skills for the continued practice of the intervention components. The interventionist provided optional home practice activities to complete between sessions and kept materials at the study office if participants were concerned about disclosure in the home. Participants were able to participate in optional booster sessions (up to six), tailored as needed to each participant, after their post-treatment assessment. Table 1 and other recent papers (Belus et al., Reference Belus, Rose, Andersen, Ciya, Joska, Myers, Safren and Magidson2020; Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Joska, Myers, Belus, Regenauer, Andersen, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2020b) provide more detail on Khanya and interventionist supervision.

Table 1. Khanya intervention manual key components by session

Procedures

Qualitative interviews

Semi-structured, individual interviews with participants who had received Khanya were conducted by trained research assistants who had not been involved in delivering the intervention and who had received both prior and study-specific interviewing training. The interview guide (supplementary materials) explored perceptions of the overall implementation outcomes of the intervention, defined by Proctor's model (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger, Griffey and Hensley2011) and of specific intervention components. Acceptability was defined as satisfaction with various aspects of the intervention. Feasibility was defined as practicality for regular use, and appropriateness was defined as the usefulness and relevance for the setting. Of the thirty Khanya participants, two were deceased and three could not be reached; we conducted audio-recorded interviews with the remaining 25. The sound quality was too poor to be transcribed for two interviews, resulting in a final sample of n = 23. Interviews were translated from isiXhosa (the dominant local language) to English before transcription.

We also conducted semi-structured individual interviews with providers working at the clinic or co-located SU treatment program (n = 9), including nurses, substance use counselors, adherence counselors, supervisors, and administrators. The interview guide (supplementary materials) focused on perceptions of Khanya and its suitability for their health system and patients.

Quantitative surveys

Participants were asked to rank order the treatment components that had been most helpful to them. The purpose of asking patients to rank components relative to one another instead of rate each component independently was to avoid potential ceiling effects, which are known to occur with patient satisfaction rating scales in health care (Salman et al., Reference Salman, Kopp, Thomas, Ring and Fatehi2020). Participants who did not receive all intervention components due to treatment non-completion were excluded; all four components were ranked by n = 20 at post-treatment and n = 22 at follow-up.

Qualitative analysis

Initial coding meetings included deductively identifying codes from the interview guide, while also inductively identifying additional codes. This allowed for coding to remain focused on perceptions of the intervention and its intervention components while ensuring any related, organically arising content was not missed (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, Reference Fereday and Muir-Cochrane2006; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Dowell and Nie2019). Qualitative interviews were then double coded by two members of the study team, working with a third team member who acted as an arbiter as needed. Coders obtained a Kappa score of 0.86 across transcripts, indicating good inter-coder reliability (O'Connor and Joffe, Reference O'Connor and Joffe2020). NVivo v.12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2020) was used for data management. Using a thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), relationships between codes were then examined and cross-cutting themes were identified in discussion among the coding team, both about the overall intervention (patient interviews and provider interviews) and for specific intervention components (patient interviews only).

Quantitative analysis

For quantitative surveys, descriptive statistics were calculated (count and percentage) to identify rankings, from first to last, for intervention components at both timepoints.

Triangulation of qualitative and quantitative data sources

After separately examining qualitative and quantitative findings, data sources were integrated to examine the convergence and divergence of patient perspectives using an integrated visual joint display table. Among mixed methods designs, triangulation is best used when qualitative and quantitative data are collected simultaneously and can each offer information on the same question. In this case, both quantitative and qualitative data were able to provide information on which intervention components patients found most salient. Triangulation of findings across methods therefore helps bolster confidence in findings when there is convergence between methods and identify areas where clarity is lacking when there is a divergence between methods (O'Cathain et al., Reference O'Cathain, Murphy and Nicholl2010). Convergence and divergence were examined at the group level, due to variable numbers of patients participating in qualitative and quantitative data collection (Fetters et al., Reference Fetters, Curry and Creswell2013). Results were compiled using an integrated visual joint display table in which qualitative and quantitative results are presented side by side to illustrate convergence and divergence (McCrudden et al., Reference McCrudden, Marchand and Schutz2021). Lastly, though qualitative data were not collected with the intention of explaining quantitative findings, qualitative data were able to provide preliminary complementary information on why intervention components were salient to patients and were examined for this purpose.

Results

Demographics

Patient participants were 48% female, 96% Black African, and had an average age of 39.2 (s.d. = 10.6). Provider participants were 56% female, 89% Black African, and had an average age of 40.8 (s.d. = 6.6).

Qualitative patient perspectives on the overall Khanya intervention

Almost all patients described the overall Khanya intervention package as being acceptable, feasible, and appropriate for their needs. Participants spoke of Khanya as transformational and having a large impact on their quality of life. One patient shared:

‘Now, I have a picture of a house that is tumbling down or it has been demolished. That's how my life was. And then when I came to Khanya it's like my, my, my, this house been built from foundation up.’

- Male, mid-30s

Delivery of Khanya by a peer reportedly enhanced its acceptability and appropriateness. Some participants described that knowing that the interventionist shared lived experiences with them both made it easier to share their experiences with her and helped them feel heard when doing so. One participant stated:

‘I was able to share whatever I wanted to share with her, you know, my problems… if I'm sharing something about myself, she would tell me that, you know, I've also experienced, um, something like that.’

- Female, mid-20s

Although overall participants described Khanya to be feasible to participate in, some challenges were noted. For instance, in some situations, participants struggled with finding private space or time to complete the home practice components of Khanya. In some cases, this was because participants had not disclosed their HIV status to those they lived with. One participant who had not disclosed her HIV status to her partner said:

‘At first I could not do things because my boyfriend was around… I did not do anything [home practice] at that time because my boyfriend was always you know around me’

- Female, early 30s

Some participants described difficulty with attending weekly Khanya sessions due to job schedules. One participant shared:

‘Since I'm self-employed, it did kind of get in the way of having to come to the sessions because I had to get jobs that I need to quickly take… because I need to get money.’

- Male, early 40s

Participants reported that Khanya largely met their needs. In addition, there were several topics that participants suggested it would be helpful to add in the future. These included additional information on both SU and HIV and support around disclosure of HIV status to close relations, which was not a focus of the intervention. One participant said:

‘I want to tell my partner but I'm not sure when to tell my-my partner about my status. I do not know when is the right time, or how-how to tell my partner. I'm not sure if this, uhm, in connection with the therapy. I don't know, but this is something I would like to get more advice on.’

- Female, early 40s

Qualitative provider perspectives on the overall Khanya intervention

Although none of the providers interviewed were directly involved with delivering the Khanya intervention, several noted that Khanya met the needs of their patients and noted improvements in HIV and SU outcomes among Khanya participants.

‘Yes, [the Khanya participants] have improved on the [ARV] default rate, they are able to adhere well. Some others they were helped so much that they are no longer using any substances now…’’

– Female, Clinical Nurse Practitioner in HIV care, early 50s

Providers noted the importance of the intervention being delivered by a peer. Not only does a peer bring vital shared lived experiences, but providers also reported that their capacity to deliver an intervention like Khanya was limited within the context of existing responsibilities. One provider said:

‘It's just the business of the clinic, you know, unless it can, like for instance, there could be allocated time for this and maybe make a plan on what, how much time or what will I be doing at a certain time because the clinic is busy and we are already short staffed.’

- Female, Enrolled Nurse in SU care, late 30s

Triangulation of qualitative and quantitative patient perceptions of specific Khanya intervention components

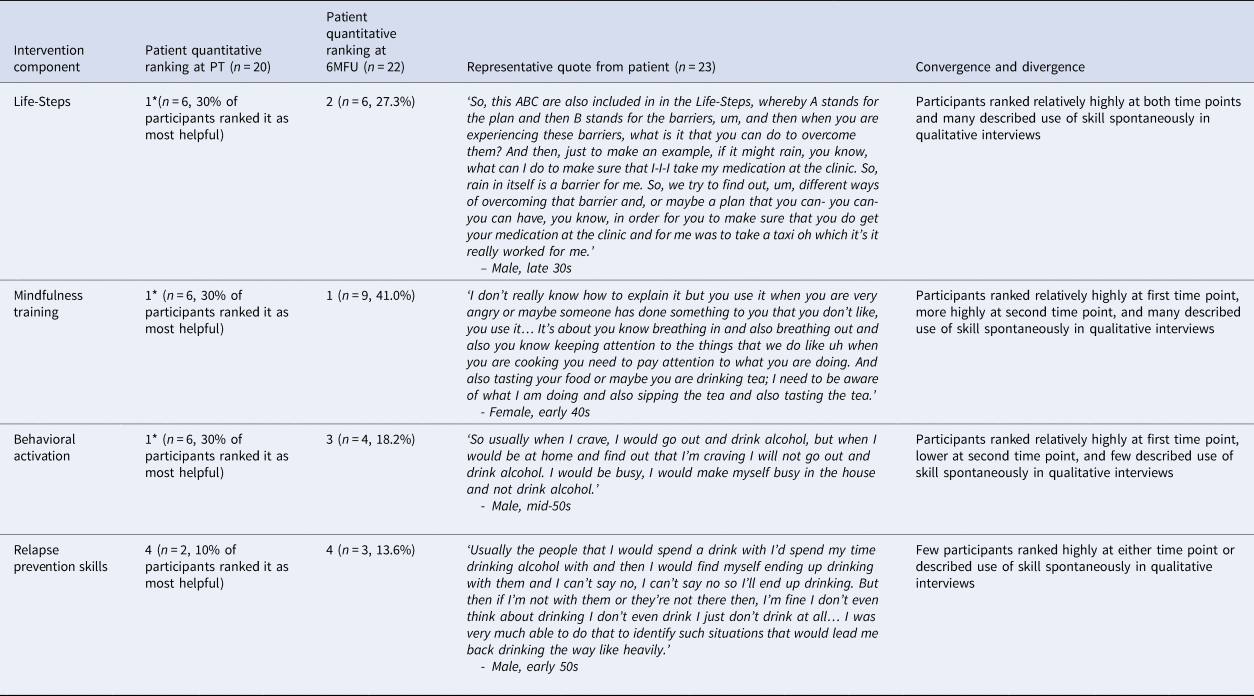

Table 2 presents an integrated visual joint display table with the quantitative rankings of Khanya intervention components alongside representative patient quotes on each intervention component and an assessment of convergence and divergence across methods.

Table 2. Integrated visual joint display table displaying quantitative and qualitative findings and convergence and divergence between qualitative and quantitative methods

PT, post-treatment assessment; 6MFU, six-month follow up assessment; *, tied with other components.

Mindfulness

Quantitatively, mindfulness training was tied with Life-Steps and BA for first (most useful) at three months (n = 6, 30.0%) and ranked first (n = 9, 41.0%) at the six-month follow up. Qualitatively, mindfulness training was also described in many interviews as being the most feasible, acceptable, and appropriate intervention component. For mindfulness training, feasibility and appropriateness were linked. Patients described the fact that they could integrate mindfulness training into their daily activities of living as being central to their perceptions of its appropriateness. Some patients also described that integrating mindfulness training directly into daily activities increased their enjoyment of the daily activities:

‘It has taught me to-to be focused and to be mindful of what I'm doing. For instance, if I'm cooking I need to, you know, focus on what I am doing at that time. If I'm stirring the pot and I would, you know, I would stir it properly and be aware that, okay I'm stirring my pot, this is what I'm doing at this moment… I was able to do these skills and to, you know, practice them and also finish what I was doing, you understand.’

- Female, early 40s

Patients also spoke of how it was easy to continue with mindfulness skills after the end of the intervention, because it fit well within their existing activities, reflecting its top ranking at the six-month follow up:

‘I try by all means even though it might not be the same as what she had taught me but I try by all means to use that one [mindfulness] also.’

- Female, mid-40s

Life-Steps

Quantitatively, Life-Steps was also ranked as a particularly helpful Khanya component, chosen first by six patients at both three-month (30.0%) and six-month (27.3%) follow ups. Qualitatively, Life-Steps was identified as a very acceptable, feasible, and appropriate aspect of Khanya in many of the interviews. Patients described that identifying their personal barriers to adherence was useful because it allowed for the development of individualized, instead of general, plans to support adherence. Patients also described that they appreciated the fact that Life-Steps allowed them to develop multiple plans to manage an adherence challenge. The development of plans and back up plans increased their confidence in their ability to manage a situation even in the face of an initial plan not working. Patients said:

‘I will figure something else, you see sister [Life-Steps] was…just to show that actually you are not just giving up, you keep on trying and have a plan, another plan, another plan, another plan over and over.’

– Male, early 30s

Behavioral activation and relapse prevention

All intervention components were ranked as most useful by at least one participant. BA and relapse prevention strategies were in general ranked less highly by participants and appeared less often in the qualitative interviews. However, some participants spoke of their value. Of BA, one participant said:

‘I also asked myself you know, certain questions like, what is it that I want from life? What is my purpose for life? You know what are my values? What is it that I want to have in this life, things like that.’

- Male, mid-30s

Of relapse prevention strategies, another participant said:

“They were drinking alcohol and then they would tell me, “[name] come, you should come and join us”. But since I knew .., I had gone there to do the job and to work so I was able to tell myself, “No. You're not supposed to drink you are here to work and you must finish your job and then go back home.”

- Male, late 30s

As indicated in Table 2, we found overall strong convergence of findings across methods. Mindfulness training and Life-Steps were quantitatively ranked as top intervention components and rich qualitative descriptions were provided by many patient participants about the acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of these components. Patients initially ranked BA the same as Life-Steps and mindfulness training yet provided fewer rich descriptions of their experience with BA, demonstrating some differences between quantitative and qualitative methods for this component. Relapse prevention strategies were ranked lowest at both time points and few patient participants discussed it qualitatively, again revealing strong convergence across methods on this topic.

Discussion

This study identified several key findings related to our primary aims of exploring perspectives on the implementation outcomes of Khanya and its specific components. Findings demonstrated that patients and providers perceived Khanya as overall acceptable, appropriate, and feasible. But some reported feasibility challenges, including with home practice. Second, mixed methods analysis demonstrated a range in how intervention components were perceived, with mindfulness training and Life-Steps identified as particularly acceptable, feasible, and appropriate by participants and relapse prevention strategies as potentially less so. Results on BA were less consistent across methods. Findings underscore the value of more granular examination of implementation outcomes and of examining outcomes of specific intervention components in addition to entire packages.

Although patient perspectives were overall positive regarding Khanya, a detailed analysis of implementation outcomes revealed variety in the patient perspectives of specific components and some difficulties with feasibility. Though brief quantitative measures, for instance the Applied Mental Health Research group (AMHR) measure used in our clinical trial (Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Joska, Belus, Andersen, Regenauer, Rose, Myers, Majokweni, O'Cleirigh and Safren2021), can help increase consistency and rigor of implementation outcomes reporting, there may also be ceiling effects within implementation outcome measures, in which ratings skew high. In general, better psychometric data is needed on quantitative implementation outcomes measures (Mettert et al., Reference Mettert, Lewis, Dorsey, Halko and Weiner2020). This also highlights the importance of qualitative data within implementation science (Hamilton and Finley, Reference Hamilton and Finley2019). Of note, the intervention's delivery by a peer contributed to positive patient and provider impressions. Providers reported they did not have the time to take on an intervention like Khanya. This suggests that not only are peer interventionists potentially acceptable and appropriate from a patient perspective but that they may offer a way of expanding the behavioral health workforce in LMICs. Leveraging the potential for peer interventionists to extend access to SU services will require the resolution of issues around the roles, training and funding of lay health workers within health systems (Masis et al., Reference Masis, Gichaga, Zerayacob, Lu and Perry2021).

Some intervention components were perceived more positively and as more salient than others. The positive patient response to Life-Steps is consistent with the broader HIV literature that has established the implementation outcomes of Life-Steps among several samples of PLWH, including samples using substances (Safren et al., Reference Safren, Otto and Worth1999; Magidson et al., Reference Magidson, Seitz-Brown, Safren and Daughters2014; Mimiaga et al., Reference Mimiaga, Bogart, Thurston, Santostefano, Closson, Skeer, Biello and Safren2019). In contrast, mindfulness training was the most novel psychotherapy component for the setting. Adaptation of mindfulness training to sub-Saharan Africa has been relatively limited to date and has focused on mental health outcomes (i.e. depression, anxiety, and stress) instead of SU or HIV outcomes (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Elkonin, de Kooker and Magidson2018; Geda et al., Reference Geda, Krell-Roesch, Fisseha, Tefera, Beyero, Rosenbaum, Szabo, Araya and Hayes2021; Musa et al., Reference Musa, Soh, Mukhtar, Soh, Oladele and Soh2021). Mindfulness training is infrequently included in task-shared psychological interventions in general (Wagenaar et al., Reference Wagenaar, Hammett, Jackson, Atkins, Belus and Kemp2020). The positive patient response to mindfulness training was seemingly driven by the feasibility of informally using these strategies within daily life and in settings where space and privacy may be a concern, a finding that echoes results of prior work in South Africa (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Elkonin, de Kooker and Magidson2018). In sum, the positive participant response to mindfulness training in this sample holds promise for the further exploration and testing of mindfulness-based approaches as part of task-shared behavioral interventions. However, there were also participants who ranked mindfulness training lowest. Better understanding the factors that contribute to the diversity of responses to intervention components may help guide the development of personalized task-shared behavioral health interventions (Ng and Weisz, Reference Ng and Weisz2016) and is an important direction for future research.

Though BA and relapse prevention strategies may have been less salient for Khanya participants, this does not necessarily mean that participants disliked these components. The use of forced-choice rankings, though intended to reduce ceiling effects, may have capped the results for these components. Notably, BA appeared to have stronger results quantitatively than qualitatively. It may be possible that patients had a harder time describing this intervention component. Using BA visuals during the interview, as was done during the intervention, may have yielded different qualitative results. Further, we included participants based on SU and not depression criteria, which may have somewhat undermined the salience of BA. There is other evidence in support of the implementation outcomes of BA in LMICs; a recent systematic review reported good acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of cognitive behavioral therapy, including BA, across ten countries (Verhey et al., Reference Verhey, Ryan, Scherer and Magidson2020). In contrast, there is somewhat less support for the implementation outcomes of relapse prevention strategies in LMICs. A recent narrative review of relapse prevention in LMICs including studies across eight countries identified the need to increase the acceptability of relapse prevention to female patients, to focus more on encouraging help-seeking, and to better tailor descriptions of SU patterns to local settings (Heijdra Suasnabar and Hipple Walters, Reference Heijdra Suasnabar and Hipple Walters2020). Within Khanya, relapse prevention strategies are only introduced in the final two sessions, so it is also possible there was insufficient time to practice this skill within the intervention. It is also possible that in a sample of participants with more severe SU, relapse prevention strategies would have had more salience.

There are several limitations to this study that are important to note. Among these is the fact that we have quantitative data from two timepoints, and qualitative data from only one, meaning we have a limited ability to draw conclusions on why patient rankings of specific components changed over time. We also had a limited sample size of intervention participants. However, our sample does represent slightly more than three quarters of those receiving Khanya and we use multiple methods convergently to bolster our findings. Additionally, as discussed above, the use of forced-choice rankings may have influenced findings. However, again we use qualitative data to reinforce quantitative findings. Lastly, only one peer interventionist delivered Khanya, which means we were not able to explore the acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of Khanya among peer providers. Future work will examine delivery by multiple peers, explore any challenges that might arise with broader peer delivery of Khanya, and explore strategies for articulating peer roles and supporting peers in South Africa.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the use of examining perspectives on the specific intervention components of behavioral interventions as well as on overall intervention packages. Perspectives on the components within Khanya vary, which should be further explored in future research and could inform future adaptations and delivery of Khanya and other similar packages. Findings suggest that peer models and other skills not typically included in task-sharing interventions, such as mindfulness training, may be well-perceived by patients and providers and indicate possible avenues for intervention innovation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.47.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the rest of the Project Khanya team and study participants, as well as the City of Cape Town Health Department and the staff at the study clinic, for their time, input, and contributions to this study.

Financial support

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA041901, PI: Magidson). ALR's time on this study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (F31MH123020, PI: Rose).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.