Political polarization, the separation of voters into distinct and often antagonistic camps, has raised increasing concern in democracies around the world. Stronger in-group identification and out-group derogation along political lines poses a threat to collective interests that depend on compromise and cooperation. Chief among these is democracy itself, support for which has declined (Armingeon and Guthmann Reference Armingeon and Guthmann2014; Wuttke et al. Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022) while support for populist radical right parties (Mudde Reference Mudde2019) has grown (Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier, Haffert, Häusermann, Steenbergen and Zollinger2024; Valentim Reference Valentim2024; Vries and Hobolt Reference Vries and Hobolt2020).

Both observational and experimental research has connected polarization to the functioning and norms of democracy. Survey data have associated polarization with lower support for democracy (Torcal and Magalhães Reference Torcal and Magalhães2022), less satisfaction with democracy (Ridge Reference Ridge2022), increased support for extremist parties (Ezrow et al. Reference Ezrow, Tavits and Homola2013), and more frequent democratic backsliding (Orhan Reference Orhan2022). Similarly, some experimental studies have shown that polarized individuals are more likely to oppose compromise, hew to their party’s positions, discount contradictory evidence, and dismiss co-partisans’ inappropriate or corrupt behavior (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). These findings collectively suggest that there is a causal, non-trivial effect of political polarization on democratic norms.

But there are nevertheless reasons to question such a relationship and whether it extends beyond elections to other areas of collective interest. Regarding the relationship itself, survey data yield correlational rather than causal associations, while experiments want for external validity. Even survey experimental designs that recruit participants in the field sometimes lack realism in the experimental setting (Barabas and Jerit Reference Barabas and Jerit2010; McDonald Reference McDonald2020). Such skepticism is magnified by recent experimental studies that find notably little effect of one kind of polarization – affective polarization, that is, animus towards out-groups – on democratic norms (Broockman, et al. Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2023; Voelkel et al. Reference Voelkel, Chu, Stagnaro, Mernyk, Redekopp, Pink, Druckman, Rand and Willer2022). Does political polarization founded on in-group loyalty actually cause the erosion of democratic norms in realistic settings? And does such a relationship, should it exist, extend to other collective interests?

To address these questions and to probe for an upper bound on what partisans are willing to sacrifice, we designed and ran survey experiments in an exceptionally realistic setting with two bold but plausible treatment scenarios. Each probes the degree to which respondents will trade off collective welfare for in-group loyalty, the first focusing on the acceptance of an unexpected electoral defeat and the second on a proposed business deal by one’s own party that could jeopardize national security. Like other survey experiments, we impose a trade-off in which participants choose between in-group loyalty and the collective interest but, following Graham and Svolik (Reference Graham and Svolik2020), we increase external validity by measuring, rather than experimentally manipulating, individuals’ partisan sentiment.

To provide a setting with a high degree of political polarization in which both treatment scenarios are plausible, we ran our studies in Poland. As one of the most politically polarized democracies (Applebaum Reference Applebaum2020; Bill and Stanley Reference Bill and Stanley2025; Carothers and O’Donohue Reference Carothers and O’Donohue2019; Dalton Reference Dalton2008), Poland is an ideal case for the first study, given the high stakes of the 2023 election, in which a victory by the ruling populist far-right Party, PiS, threatened to entrench authoritarian rule (see, for example, Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2023; Markowski Reference Markowski2019). Moreover, its history of conflict with and occupation by Russia makes it especially suitable for an extension to our second collective good, national security, especially after the Russian invasion of neighboring Ukraine in 2022.

While previous work has shown that partisan attachments can trump adherence to democratic norms – especially in the wake of events such as the 2020 US presidential election and the January 6th insurrection (Mason and Kalmoe Reference Mason and Kalmoe2022; Vail et al. Reference Vail, Kalmoe, Carey, Helmke, Nyhan and Stokes2023) – our contribution is to extend this line of inquiry to a context in which both public goods – electoral integrity and national security – are highly salient. Specifically, we examine Poland to investigate and to compare the degree to which respondents trade off different public goods ‘when it really matters’. This allows us to ask whether democracy is treated as more fungible than another vital societal interest, security.

This research note finds that in-group loyalty motivates a surprisingly large proportion of individuals to make choices that jeopardize democratic norms, even in realistic contexts when the stakes are high – but less so for national security. Our findings bear at least two notable implications. First, the effects that we find for democratic norms are dangerously high. For example, 40 per cent of supporters with an average level of loyalty to either the far-right PiS party or the centrist PO party supported canceling and rerunning an election if their party unexpectedly lost, with this figure approaching a staggering 80 per cent for the most partisan supporters of PiS. This illustrates that partisan polarization is not only a threat to democracy in sanitized contexts or following experimentally induced partisan sentiment, but also with naturally occurring partisanship when democracy is in actual jeopardy. The failure of a large proportion of partisans to accept election results in the absence of evidence of fraud erodes a cornerstone of democratic legitimacy (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005).

Second, individuals might value different collective goods differently. While national security is not immune from partisanship, the effects are smaller and only statistically significant for each party in a certain range of partisanship. One could find it either disconcerting that co-partisans increase their support for selling a critical port to China (a Russian ally) shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine if their party is involved – or reassuring that well less than a quarter of supporters of either party at average levels of partisanship would support such a damaging act. While the weaker results for national security might also arise from a weaker treatment, the strong results in the first study could nevertheless suggest that there may be something particular about democracy.

Our findings suggest that democracy may be perceived by many citizens as a procedural and therefore more negotiable good, whereas national security is treated as existential and less negotiable. This distinction, should it exist, could stem from several mechanisms: (1) democratic norms often involve delayed or indirect consequences, while breaches in national security evoke immediate and concrete risks; (2) democracy is sometimes valued instrumentally (Ahlstrom-Vij Reference Ahlstrom-Vij2021) – as a process that delivers outcomes – whereas security is more often valued intrinsically, as a precondition for survival; and (3) the salience of threats differs: national security threats are cross-cutting and collectively existential, while democracy can be seen as procedural with harm and benefit accruing to different groups. Our study leverages this contrast to highlight how intrinsic versus instrumental valuation helps explain why polarization readily erodes democratic norms but less easily national security.

Research Design

In order to test whether partisanship drives support for harmful policies in realistic contexts, we conducted two survey experiments, ‘Acceptance of Elections’ (Study 1) and ‘National Security’ (Study 2).Footnote 1 The experiments differed only in the wording of the treatment and outcome questions. We fielded the experiments with the survey company Kantar in October 2023, just before the national election (Study 1), and in November 2022, during the first year of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Study 2).Footnote 2

Our experiments rely on two-treatment, between-subjects comparisons. That is, including the control, we use three versions of each questionnaire in each study. The survey experiments test policy preferences of partisans in polarized democracies by providing respondents with information about (1) an unexpected result of an election and a political proposal to rerun it, and (2) a political proposal to sell sensitive national assets to a foreign power. Each of these proposals is supported by one of the two main political rivals, the party of Donald Tusk, Civic Platform (‘PO’), or the party of Jarosław Kaczyński, Law and Justice (‘PiS’). We choose these two parties in particular and argue that this set-up compares well with the US context, in line with scholars such as Markowski (Reference Markowski2016), Szczerbiak (Reference Szczerbiak2025, Reference Szczerbiak2008), and Cześnik and Kotnarowski (Reference Czésnik and Kotnarowski2011), who have shown how Poland’s post-transition party competition has consolidated into a de facto two-party axis, despite the multiparty system.

Our design relies on observational, that is, non-induced, variation in partisan attachment. While this approach enhances ecological validity, it limits causal identification of the effect of the strength of partisan attachment. The partisan identity of the political party (PO or PiS) in each treatment, in contrast, is experimentally manipulated, allowing causal interpretation of the effect of, say, PO or PiS proposing an action as opposed to the control. We examine how the strength of partisan attachment conditions causal responses to treatments, rather than making strong claims about exogenous shifts in the strength of partisanship.

Treatments

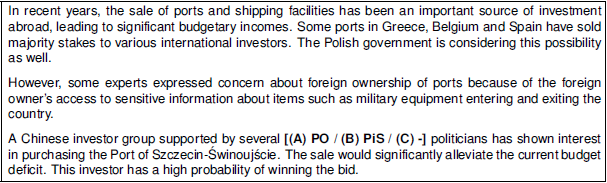

We crafted two concise narratives depicting hypothetical situations where one of the two primary political rivals backs a policy that could undermine democratic norms (Study 1, InfoBox 1) or jeopardize national security by allowing a foreign power access to an important shipping and naval port (Study 2, InfoBox 2). Participants were randomized into one of three treatment options that featured the PO, PiS, or a control that did not specify either of the rivals. The participants were instructed to read and imagine a hypothetical but plausible scenario of a way to tackle a political controversy.

InfoBox 1. Treatment (A, B) and control (C) conditions in ‘Acceptance of Elections’ (Study 1).

InfoBox 2. Treatment (A, B) and control (C) conditions in ‘National Security’ (Study 2).

One caveat is worth noting. In Study 1, we intentionally created a scenario in the treatment vignette (‘contrary to expectations’) that, with enough partisan-motivated reasoning, could justify rerunning the election, but would, objectively seen, be a violation of electoral integrity. The statement that election observers did not note any large-scale irregularities is meant to serve as the definitive statement about the integrity of the election itself, whereas prior expectations, even if based on polling, do not relate directly to the election.

Outcomes

We employed one outcome per experiment. The outcome question, measured on a 1–10 scale, elicited respondents’ support for canceling and then rerunning the election (Study 1) or for selling the port to the Chinese investor (Study 2) – the policies supported by either of the main rival parties (treatment conditions) or by no one in particular (control conditions).

Party Identification and Strength

Although this study is motivated by partisan polarization, what we measure, specifically, is variation in partisan identification and strength of attachment. Stronger partisan attachment, however, often strongly correlates with affective polarization (for evidence from the US context see Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015), and research in psychology suggests that in-group norm perceptions drive most of out-group hostility (You and Lee Reference You and Lee2024). We consequently focus on how levels of partisan attachment condition willingness to sacrifice collective goods and thereby treat partisan attachment as a proximate mechanism of polarization effects.

We asked a battery of questions including party identification, vote intention, and past voting behavior items that together elicited the respondent’s preference for one of the two rival parties. A small subset of the sample (approximately 5 per cent across both studies) was identified on the basis of their answers to the question ‘If you had to choose between only PiS and PO, which of the two parties would you say you feel closer to?’Footnote 3 Subsequently, to estimate the strength of that identification, we adapted the measure developed by Graham and Svolik (Reference Graham and Svolik2020) for the study of polarization in the US context.Footnote 4 These two measures enabled us to account for respondents’ potential co-partisanship with the party featured in the treatment.

Estimation

After splitting the data into two samples, PO and PiS supporters, we run different versions of the following specification with ordinary least squares:

where the dependent variable, Y i , denotes the respondent’s level of agreement with the presented policy measured on a 1–10 scale. T i stands for the randomly assigned experimental condition and Partisanship i denotes the level of agreement with the battery of partisanship strength questions meant to elicit how strongly each participant identifies with either the PO or the PiS party. To address concerns about potential pre-treatment and post-treatment effects, we randomize the order in which we show the demographic questions. We include the resulting treatment order variable, Torder, as a control. We also include NUTS-3 province (‘voivodeship’) fixed effects φ Vi in our models to account for regional time-invariant confounders. In both studies, we filter out respondents who did not pass the standard manipulation check. In our estimation, we compare each treatment arm against the control condition.

Results: Acceptance of Elections (Study 1)

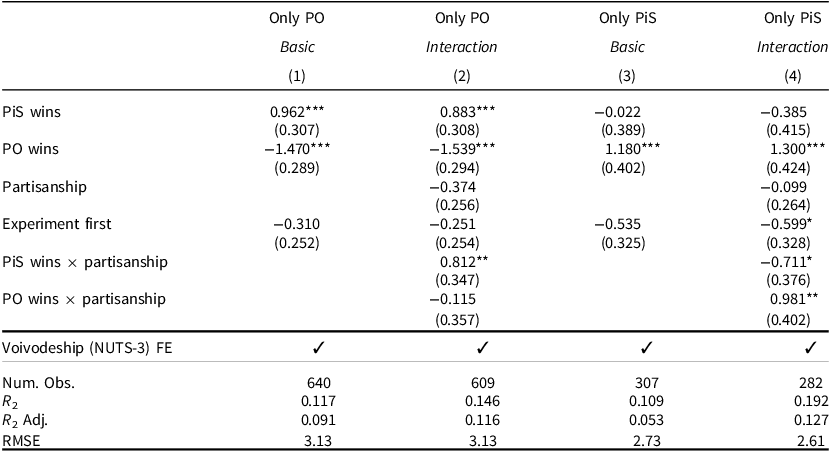

To estimate the effect of the treatment (PO, PiS, or an unspecified party winning) and the strength of partisanship on support for canceling and rerunning the election, we split the sample by respondents’ Party ID. Table 1 presents the results for PO (Models 1 and 2) and PiS (Models 3 and 4) supporters. Models (1) and (3) show that when the opposite party unexpectedly wins, both PO and PiS partisans support rerunning the election more than when an unspecified party wins, with support rising by roughly a full point on the ten-point scale. Models (2) and (4) add interactions of each experimental condition, respectively, with the respondent’s strength of partisanship in order to test how partisan sentiment affects the willingness to violate a democratic norm when one’s own party is disadvantaged. We see in both cases that a standard deviation increase in partisanship greatly increases support for rerunning the election – by 0.8 and 0.9 points, respectively. Relative to when an unidentified party lost, strong partisans (z = 2) for each party support rerunning the election when their party unexpectedly lost, by a three-point margin on the ten-point scale, as illustrated in marginal effects plots in SM Figure A2.

Table 1. Effect of partisanship on support for rerunning election (Study 1)

Note: Ordinary least squares. Robust s.e. in parentheses. RMSE: root mean square error. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

So how big a problem is partisan polarization for electoral integrity in this experiment, run shortly before a highly partisan election in which democracy was at risk? The substantive magnitude may be best communicated in this case by the probability of participants supporting the cancelation and rerunning of an election than by changes in support on a ten-point scale. Accordingly, we recode the outcome variable into a binary outcome (> 5 coded as 1, else 0), run a logit model based on the specification in Equation 1 (SM Table A8), and plot the predicted probabilities of support in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Predicted probability of wanting to rerun the election if the opposing party wins.

The model predicts that approximately 40 per cent of PO supporters with an average level of partisanship advocate canceling and rerunning the election when PiS unexpectedly wins, rising to over 50 per cent for the most partisan. Among PiS supporters, an average level of partisanship predicts a slightly less than 40 per cent probability of advocating for rerunning the election, rising to nearly 80 per cent for the most ardent supporters. Partisanship seems to have greater influence on PiS supporters, with weaker partisans expressing greater hesitancy to rerun the election than PO supporters of a similar partisanship strength in the opposite scenario. It is possible, although we cannot show this, that less partisan PiS supporters were sensitized by accusations that the incumbent PiS government had eroded democracy. Most noteworthy, however, is the large amount of support in general for canceling and rerunning an election that was not found to be flawed by impartial observers when one’s own party surprisingly lost. It seems that partisanship erodes democratic norms even in realistic contexts.

Results: National Security (Study 2)

Partisans in the first study were willing to violate a democratic norm when it was disadvantageous to their party, but would residents of Poland be willing to jeopardize national security for in-group loyalty? To investigate this question in a realistic setting, we ran a study in November 2022, during the first year of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. National security was highly salient, as indicated by a modal response of ten on a ten-point scale in our survey question asking whether national security was currently the most important political issue facing Poland (Figure A11 in the SM). Our intention was to find a limiting case to test the upper bounds of the strength of in-group loyalty, when the potential for harm to general welfare was high. In other words, how bad can it get?

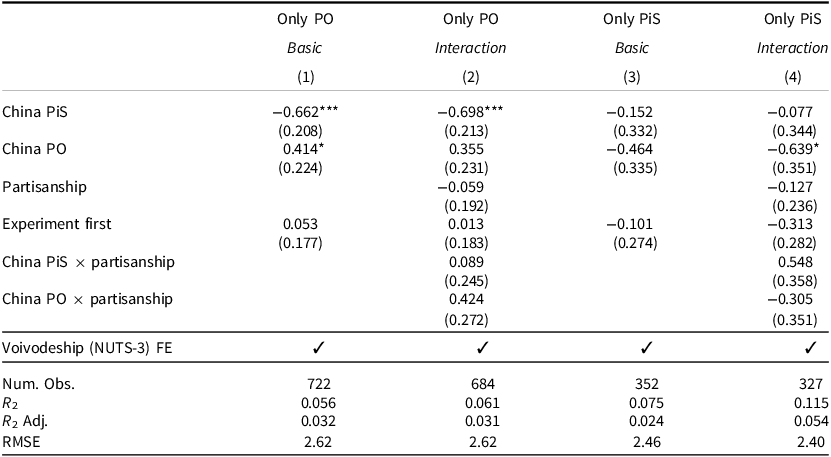

In Study 2, we again split the sample by respondents’ Party ID and run variants of Equation 1, as shown in Table 2, again including fixed effects at the voivodeship (NUTS-3) level. The dependent variable in this study is support for selling an important port to China, an act that would give a country that is friendly with Russia information about sensitive Polish military and industrial imports. There are two treatments in which the PiS and PO politicians, respectively, support the sale and a control group in which no politicians are mentioned. We estimate the effect of the treatment conditions (China-PiS and China-PO) vis-à-vis the control.

Table 2. Effect of partisanship on support for port deal (Study 2)

Note: Ordinary least squares. Robust s.e. in parentheses. RMSE: root mean square error. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Models (1) and (3) show only a modest to null effect of the involvement of one’s own party on support for a transaction that could undermine national security, selling a port to China. Conditioning the effects of the treatments on the strength of respondent partisanship in Models (2) and (4) does show larger effects among strong partisans. As the marginal effects plots in SM Figure A4 reveal, however, the treatment effect of one’s own party supporting the deal never reaches statistical significance for PiS co-partisans and only does so for above average partisans of PO.

As in Study 1, predicted probabilities better convey the substantive magnitude of the effects. What is the probability of a respondent supporting a decision that damages national security when one’s own party is involved, and how does this share increase with partisanship? Following Study 1, we again dichotomize our outcome variable (>5 coded as 1, else 0) and run the model specified in Equation 1, albeit as a logit (SM Table A11).

Figure 2 plots out the predicted probabilities of supporting the sale of the port when the respondent’s own party is involved. For neither party does the predicted probability of support reach 40 per cent, and for most partisans of both parties the predicted probability of supporting the sale remains near or below 25 per cent. PiS supporters, however, are more uniformly resistant to the idea, while support from the most partisan PO supporters breaches 30 per cent.

Figure 2. Predicted probability of wanting to sell the port to China.

Treatment strength could explain differences in effect sizes between Studies 1 and 2, as could the possibility that by discussing national security, Study 2 primed national as well as partisan identity. It remains likely, however, that at least part of the substantially weaker effect in Study 2 comes from a greater willingness to trade off electoral integrity (Study 1) than national security (Study 2) for partisan loyalty, especially given that the treatment in Study 2 made support for the sale of the port palatable by mentioning other countries that sold ports, the budgetary benefits, and a sale to China (rather than to Russia). If the weak support for selling the port might indeed suggest greater sensitivity to jeopardizing national security, we may have approached an upper bound on what partisans are willing to sacrifice for in-group loyalty.

Conclusion

Scholars have cataloged the risk of extreme partisanship for democratic norms and, ultimately, democracy itself. We know less, however, about how well these findings hold up in realistic contexts and how much other collective goods, other than democracy, could also be threatened. The findings of our first study suggest that previous research on the fragility of democratic norms in the face of partisan polarization are depressingly robust to more realistic contexts. Our second study, however, by showing that participants are largely unwilling to trade off national security for in-group loyalty, may suggest a limit on what citizens are willing to sacrifice. Although direct comparisons cannot be drawn between studies with different treatments, the contrasting results nevertheless invite questions about what explains the strong willingness of partisans to violate a democratic norm. An intriguing possibility is that individuals might value elections more instrumentally than innately.

Should this be the case, political debate and the campaign strategies of democratic parties in countries facing an electoral challenge from the far right might be misplaced. Political actors who raise the alarm about the danger of populist far-right parties for democracy, for example, may find that their calls have limited resonance, let alone electoral influence, among voters. A good strategy for gauging the substantive value of a collective good such as democracy to citizens is to see how readily they trade it off against other goods (see, for example, Chu et al. Reference Chu, Williamson and Yeung2025). We have seen in this research note that they are very willing to sacrifice electoral integrity for in-group advantage, but seemingly less so national security.

Our results carry implications for democratic resilience. If voters are indeed more willing to compromise on democratic procedures than on security, strategies that tie democracy to more existential and less procedural issues may reduce its perceived fungibility. Pro-democracy campaigns might frame institutional integrity as a bulwark against external threats or economic uncertainty. Similarly, media and civil society can emphasize that rule of law is not just procedural but foundational for national strength. More broadly, our findings suggest that institutional safeguards must be robust precisely because citizen support for democracy may be conditional.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425101257.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OD80AH.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nicolai Berk, Daniel Bischof, Elias Dinas, Bence Hamrak, Sara Hobolt, Markus Kollberg, Kristian Frederiksen, Lanny Martin, Marta Ratajczyk, and participants in seminars at the 2024 Civica Political Behavior and Institutions conference and ‘Sparks seminar’ at the EUI, the Hertie School PELS Workshop, and the annual meeting of the European Political Science Association, Cologne.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Standards

Hertie School Research Ethics Office has provided prior ethical approvals for conducting both studies (9 May 2022 and 19 September 2023; ID 20230917-67).