The alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable: greenhouse gas emissions from fossil-fuel burning and deforestation are choking our planet and putting billions of people at immediate risk. … The solutions are clear. Inclusive and green economies, prosperity, cleaner air- and better health are possible for all if we respond to this crisis with solidarity and courage.

1.1 Introduction

A child born in the world today can expect to live until the end of the century – global life expectancy at birth is now around seventy-three years (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2022). What will that child’s life be like from infancy and adolescence to adulthood and old age? What opportunities will be available to them and what challenges will they have to navigate? What role can education play in providing the knowledge and skills to enable them to thrive? This manifesto argues for the critical role of education in cultivating informed and capable planetary citizens who can critically analyse complex issues and drive change by advocating for, developing and deploying just and sustainable solutions.

It is clear that the future lives of all children will be profoundly affected by human-induced environmental change, including climate breakdown; species extinction; pollution of the air, soil, freshwater and oceans; and resource depletion. Sadly, it makes a difference where a child is born – some are at greater risk than others. Nearly half of the world’s children (1 billion) live in countries that are at extremely high risk from the impacts of climate change. Other societal inequalities are intertwined. Today, the disparity between the country with the highest and the country with lowest life expectancy at birth is more than thirty years; and within countries, income and wealth inequalities have risen nearly everywhere since the 1980s (Chancel et al., Reference Chancel2022). In a global population of 8 billion, around three-quarters of a billion people faced hunger in 2022, double that number did not have enough water to meet their everyday needs and conflict left more than 100 million displaced from their homes.

The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate (Watts et al., Reference Watts2019) has traced the possible impact of fossil fuel use and climate change through the life of a child born today. Infants can be permanently affected by undernutrition resulting from crop failures and are at risk from extreme heat; children are very susceptible to diarrhoeal diseases propagated by flooding and are especially vulnerable to dengue fever as mosquitos encroach into new regions. Through adolescence and beyond, air pollution causes an accumulation of damage to the heart and lungs, which today results in 7 million premature deaths globally each year. Families and livelihoods are put at direct risk from extreme weather and sea level rise, and indirect risk through the knock-on impacts on food, freshwater, disease, habitation and critical infrastructure. The elderly are particularly vulnerable to deadly heatwaves, which are increasing in frequency and severity. Climate change will have widespread social implications with some areas of the planet becoming unliveable. Thus, today’s children will experience a world which looks dramatically different to the present. This raises questions such as how do we prepare young people for such a future, and how can we train them to design novel solutions to mitigate these problems and to adapt to a changing environment in resilient and creative ways?

1.2 Unsustainable Consumption

We currently use more resources and burn more fossil fuels than the Earth’s systems are able to regenerate and adsorb the emissions from. In the past fifty years, the human population has doubled, the global economy has grown nearly four-fold and global trade has grown ten-fold, together driving up the demand for energy and materials. The term the Anthropocene is sometimes used to describe our current epoch. This gives us a frame of reference to say that there has been a profound change in the way in which we, as humans, are impacting the fragile planet that we happen to inhabit. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2023) put things in stark terms in its most recent report, stating that there is a ‘rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all’. That is a startling phrase and one that immediately leads to questions as to what a sustainable future for all means in the context of debates around justice and injustice.

The challenge of controlling the global consumption of resources is often referred to as the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’. This idea, based on a parable of over-grazing of livestock on common land, describes a scenario where there is some shared resource which individuals can benefit from using but where the costs of using it accrue to a group. The simplistic description indicates the challenge could be overcome through regulation and enforcement to constrain individual excesses. Yet the challenge is not simply one of overcoming self-interest – issues such as equity, justice and good governance are equally important. In recognition of this, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change has since its inception in 1992 enshrined the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’.

1.3 The Climate Crisis

Human-induced climate change is driving extreme weather and climate events in all regions of the world, including deadly heatwaves, wildfires, floods and droughts (IPCC, 2023). In 2023, the annual average global temperature was 1.45°C higher than it was in the latter half of the nineteenth century, which is often termed the ‘pre-industrial’ era.

Society in many parts of the world has been transformed through industrialisation but this has generated greenhouse gas emissions, largely by burning fossil fuels, deforestation, intensive farming and industrial processes. Greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane and nitrous oxide act to trap heat from the sun in the atmosphere. As greenhouse gas concentrations rise, so do global temperatures, leading to sea level rise, ice loss and extreme weather, with increasingly devasting consequences. Today’s levels of CO2 are around 420 ppm, having increased by 50 per cent since the start of the industrial revolution. This is far outside natural variability which has seen CO2 slowly oscillate between about 180 and 280 ppm as the Earth has in the past moved in and out of ice ages over hundreds of thousands of years. Methane and nitrous oxide have also seen huge, abnormal increases as the world has industrialised (over 150 per cent and nearly 25 per cent increases, respectively).

One prominent sign of warming has been the dramatic melting of ice. In the last decade, ice mass loss from Greenland has doubled in comparison to the previous decade, and in Antarctica it has tripled, leading to an acceleration of sea level rise. At the end of the summer melt season each year, Arctic sea ice now covers a little over half the area it did at the start of the satellite record in 1979, while Antarctic sea ice reached its lowest extent in the satellite record in 2023. Glaciers around the world are retreating rapidly, with those in Switzerland losing 10 per cent of their remaining volume in just two years from 2021 to 2023. In the ocean, marine heatwaves have increased in frequency and intensity, and the waters are becoming more acidic as carbon dioxide dissolves in the seas, with major implications for marine life.

Climate-related risks to health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security and economic growth are projected to increase with global warming of 1.5°C and even more so above that. There exist many potential tipping points in the climate that could lead to catastrophic change, including collapse of ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland, changes in ocean circulation, release of frozen methane from the Arctic and the rapid dieback of the Amazon rainforest. The destabilisation of areas of the Antarctic polar ice sheet and/or the irreversible loss of the Greenland ice sheet could cause a rise of several metres in sea level on time scales ranging from centuries to millennia. These instabilities could be triggered by around 1.5°–2°C of sustained global warming. A large fraction of warm-water corals may be lost at 1.5°C of warming and nearly all at 2°C. This is highly consequential as over half a billion people rely on them for their livelihoods (e.g. fishing, tourism) and over a quarter of marine species for part of their life cycle. Overall, two to three times more plants and animals are anticipated to suffer severe habitat loss at 2°C versus 1.5°C of warming. Increases in heat and humidity mean that, increasingly, the threshold of human physiological survival could be passed in some locations: regions at greatest risk include India and the Indus River Valley (population 2.2 billion), eastern China (population 1.0 billion) and sub-Saharan Africa (population 0.8 billion); at 3°C of global warming, parts of North and South America risk passing survival thresholds.

This is a devastating picture of the future. Mitigating the dangerous effects of climate change requires deep, rapid and sustained emissions reductions and bringing CO2 emissions to net zero that will be challenging to achieve. Yet there is hope – the IPCC has highlighted that feasible, effective and low-cost nature-based, social and technical solutions are already available. But they need to be deployed at a grand scale, while maintaining a pipeline of new innovations. That requires the right finance and policy support, but it also requires people who have the relevant technical, managerial and vocational skills. In other words, it requires the right support from our educational system.

In parallel to the development and implementation of mitigation solutions, we need to understand the weather extremes that are already impacting communities and build resilience to them – for example through early warning systems or flood defensive measures. Skills training associated with adapting to climate change has its own set of priorities and will likely be very different in different places. In small island developing states, for example, adaptation education may include strategically preparing young people for migration; in other countries it may include supporting young people to be compassionate towards climate migrants.

1.4 The Ecological Crisis

Today we face an ecological crisis that is inextricably linked to the climate crisis. Exploitative human activities mean we are currently experiencing a sixth mass extinction which is taking place more rapidly than the extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Previous mass extinctions – generally defined to be periods when over three-quarters of species on Earth have been lost in 2 million years or less – were caused by extreme temperature changes, rising or falling sea levels and catastrophic, one-off events such as huge volcanic eruptions or an asteroid hitting Earth.

Today the largest single driver of biodiversity loss is habitat destruction by people through changes in land and sea use, including by cutting down rainforests to provide land for agriculture and urbanisation. The space left for nature is increasingly small, and biodiversity loss is further exacerbated by direct exploitation of organisms, pollution, invasion of alien species and climate change. Outside of a few special places, such as Antarctica, there are few places of ‘wilderness’ left. This has led to criticism that television nature documentaries sometimes portray a world that for the most part no longer exists. However, humans and nature have co-existed for thousands of years, and there have long been very few completely pristine locations. Instead, problems for biodiversity have arisen in recent times, not simply through the presence of humans but through our destructive actions on a grand scale (e.g. Thurstan, Brockington and Roberts, Reference Thurstan, Brockington and Roberts2010).

The global rate of species extinction is already at least tens to hundreds of times higher than the average rate over the past 10 million years, and it is accelerating. Meanwhile the World Wildlife Federation’s Living Planet Index (Almond et al., Reference Almond2022), which tracks the abundance of vertebrate organisms (everything from fish to elephants to birds to frogs), has shown that global wildlife populations have plummeted by two-thirds since 1970. These losses are not distributed evenly – some regions experience more loss than others and particular sets of organisms have challenges that make them especially vulnerable. For example global amphibian populations are collapsing due to reductions in freshwater, which is needed for reproduction, plus the emergence of multiple disease threats.

Reflecting on this picture of extinction and habitat degradation, one might ask: how or in what way does this matter for humanity? Beyond the implicit value of these organisms, and the fondness we may hold for them, what is their functional value? People are fundamentally linked to, and a part of, ecological systems and we rely on them one way or another for the majority of our needs – they provide vital ‘ecosystem services’. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (Brondizio et al., Reference Brondizio2019) notes, ‘Nature is essential for human existence and good quality of life. Most of nature’s contributions are not fully replaceable, and some are irreplaceable.’

Pollination is an example of an ecosystem service upon which humanity relies. Pollinators contribute to the agricultural yield for an estimated 35 per cent of global food production and are directly responsible for up to 40 per cent of the world’s supply of some micronutrients, such as vitamin A. Yet there is growing evidence of wild pollinator population declines due to changes in land management, climate change and agrochemical use (Dicks et al., Reference Dicks2021). There are a vast number of other ecosystem services, ranging from flood prevention to the regulation of air quality, climate and freshwater quantity and location; the formation, protection and decontamination of soils and sediments; and the regulation of ocean acidification and energy – not to mention the many medical innovations humanity has taken from the natural world and the effects that nature has on people’s psychological well-being. Ecosystem services are fundamental to human existence and well-being but are themselves dependent on the organisms and ecology, which we are losing at scale.

Education is essential for people to understand the critical importance of these systems and our reliance on them, and to develop the skills required to halt and reverse the damage.

1.5 The Planetary Crisis

In 2015, the United Nations adopted a set of Sustainable Development Goals to be achieved by 2030. These included ambitions to realise human rights of all, eradicate poverty, end world hunger and ensure access to clean energy, clean water and sanitation for all. The 2024 update demonstrates that the majority of the goals are not on track and more than one-third are stalled or regressing (UN, 2024). This isn’t only a climate crisis or an ecological crisis – it is a planetary crisis directly impacting human well-being that is connected to a broad set of planetary injustices.

The global food system faces explicit threats from a changing climate, meaning weather-sensitive food production centres may need to shift. This provides additional challenges in that pollinators may not be able to shift their range as fast as the arable crops they pollinate, leading to potential further system breakdown. The current meat consumption of Western culture remains aspirational at a global scale. This is a challenge, as animal agriculture is far less efficient than arable – each gram of protein produced using animal agriculture requires a far greater input of land, resources and energy – essentially because animals use energy to move around, breathe and reproduce. Also, some common livestock animals, such as cows and sheep, produce high volumes of methane, a highly warming greenhouse gas. The heavy use of fertilisers drives emissions of nitrous oxide, another greenhouse gas, while intensive farming practices can lead to a loss of pollinators and soil microbe diversity, both of which are essential for the continued good functioning of the food system. Climate, environmental and societal dimensions are intertwined.

Usable fresh water represents only 1 per cent of all water on the planet, with the majority either in the oceans or frozen as ice. We get fresh water from rivers, lakes, groundwater and rain, and this water supply is dependent on the water cycle. In the water cycle, water evaporates from multiple sources, including the oceans and evapotranspiration from plants, and turns into water vapour. Water vapour then rises and cools to form clouds, and the water eventually falls back to Earth in the form of rain. Increasing temperatures due to climate change are increasing the rates of evaporation and precipitation, but these changes are not evenly distributed around the world with implications for water supplies. Melted snow and glacial ice from the Himalayas and other mountains feed the Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra river systems, providing water for communities, agriculture, industry and hydropower stretching from India to China and beyond. The region provides water to 2 billion people, but climate change is threatening the supplies.

Climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental damage can also directly impact human health. Higher temperatures are leading to the geographic spread of some diseases, for example as new locations become viable for the mosquitos that carry diseases such as malaria and dengue. The effects of severe weather incidents can also have impacts on human health, for example drought leading to famine and malnutrition, flooding leading to poor sanitation and increased spread of disease, high variation in summer temperatures leading to heat stress induced mortality and storms leading to injuries, fatalities and mental health issues. Air pollution increases the risk of asthma and cardiovascular disease. Environmental degradation can lead to forced migration and can exacerbate tensions leading to civil conflict. As we continue to encroach on habitats for agriculture and housing, there is also an increased likelihood of zoonotic disease, where diseases in animal reservoirs are transmitted to humans.

Overall, we are already seeing devastating effects arising from our overuse of the world’s resources, from our emissions of greenhouse gases and through habitat destruction, which severely impacts the ecosystems that provide us with the essential resources that humans need for life. When these effects are coupled with a set of global economic constraints that prioritise continued overextraction and resource use, and interact with underlying social inequalities, the challenges we face are severe.

The Dasgupta Review (Reference Dasgupta2021) on the economics of biodiversity highlighted a paradox which is about how we measure human prosperity. Compared to being alive in 1750, being alive today, for most people, is better. Average incomes have gone up, and the likelihood that you might live in absolute poverty is significantly reduced. Life expectancy is much better; mortality rates have dropped. As a human, perhaps we’re living in the best of times. But from a planetary perspective, we’re living in a pretty terrible time. Extinction rates are up, ecosystem services are declining and global temperatures are increasing. The framework of planetary boundaries suggests that a number of the constraints that we have around human existence in terms of the planet’s ability to sustain us are being breached. So what’s going on here? On one hand, measured prosperity, especially gross domestic product, tells us that everything is great. And all the other indices say that the world is actually in serious crisis. That begs the question, Are we measuring the wrong thing?

1.6 An Unequal World

Different people in different parts of the planet are experiencing these changes in very different ways. This justice perspective is easily hidden in an aggregated description of the challenges. Why does inequality matter? Human-induced greenhouse gas emissions are not caused by “people” in general, but by specific human activities by specific people or groups of people.’ This is something Indian scholars Anil Argarwal and Sunita Narain (Reference Argarwal and Narain1991) discussed thirty years ago in their book Global Warming in an Unequal World. There is a similar narrative for biodiversity. The decline of the biosphere creates enhanced inequality with a circular relationship where enhanced inequality is contributing to further declines in the biosphere.

The numbers demonstrate this inequality clearly. Today, one-tenth of the global population is responsible for close to half of all carbon emissions, and the top 1 per cent emits about 50 per cent more than the entire bottom half of the population. The top six emitters by country in 2022 covered 67 per cent of global emissions: China 31 per cent, the US 14 per cent, India 8 per cent, the EU 7 per cent, Russia 4 per cent and Japan 3 per cent. Per capita emissions in Europe (6.3 tonnes/person) are more than half those of the US (14.9 tonnes/person) but now less than China (8.0 tonnes/person), which has seen a rapid increase in recent years. Within country inequalities are great: the top 10 per cent in the US emit 3.5 times the average, and in China the top 10 per cent emit 4.5 times the average. In India the top 10 per cent emit four times the average, with a similar per capita emissions to the European average. Talking about emissions in an undifferentiated way is not really drawing adequate attention to the different consumption patterns of different people. This question of extreme inequality matters – the overconsumption of the rich is constraining the space for the legitimate consumption needs of the poor.

In addition to the inequality between people and between nations there is also, obviously, an intergenerational inequality. As we think about the role of education, it is really important to see how the consumption actions of the present high-consuming generation are constraining the space available for future generations. The remaining ‘carbon budget’ can be considered to be the total future emissions that give a 50 per cent likelihood of limiting warming to 1.5°C. For someone born in 2024, the carbon budget available to them, assuming it was equally shared, would be one-fifth that of a parent born in 1994. We tend to think about human prosperity as future generations being better off than ourselves, and yet this a context in which we are constraining the space for the youth of today.

1.7 The Role of Education

On the basis of the foregoing assessment of the state of the world and the challenges of the coming decades, what role can education play in supporting an appropriate response that ensures the planet remains survivable and society thrives?

Perhaps the most important thing that is needed is engagement with a positive vision of what is possible. Of course, many young people today have an acute understanding of the climate and environmental crises we face, how they have come about, the danger of inaction, and in broad terms what can be done to address the threat. But action at scale requires widespread awareness of and engagement with the issues which can in turn drive governments and markets to change the way in which they devise policy and conduct business to ensure sustainability is at the heart. It also requires a common belief that we can catalyse the change that is needed for a resilient and sustainable future. If an example is needed that it is possible, the rapid decrease in the cost and useability of solar power is a clear illustration of how policy and innovation can drive meaningful change.

The citizen’s voice is becoming more and more visible, in particular, the voice of young people. But how do we create space for informed citizens to be part of the dialogue rather than for that dialogue to be dominated by experts sitting in conferences convened well outside of everyday discourse? One interesting approach that has been attempted in the UK is a Citizens Assembly, where a group of people come together and deliberate with each other. In the face of evidence that is presented to them, as you might have in a criminal trial, they are expected to come up with a reasoned judgement about the next step forward. And how can we, especially in the Minority World, ensure we are open to the rich knowledge that already exists across the globe? We don’t need to educate people in Bangladesh about the impact of climate change – they are experiencing it on an everyday, visceral level. But as we mentioned earlier, people like Anil Argarwal and Sunita Narain have provided profound insight for decades – how can we embrace this, rather than us rediscovering and misappropriating or re-appropriating the language and the knowledge which already exist?

Context-specific education which enables and empowers young people to gain the knowledge and skills they need to be resilient to the climate crisis is essential. One such example, Pani Pahar, described in detail in Chapter 14 (see also Figure 1.1), started as a research programme on water and water scarcity in Indian mountain areas and developed through collaboration with educators in India into a free resource across three stages of the school curriculum in relation to climate, water, justice, equity and activism. In a further example, Cambridge Climate Quest is a climate literacy programme, launched in India in 2024, which aims to help young learners aged fourteen to sixteen in their journey of climate awareness, literacy and action. The focus of the programme is to develop youth awareness of climate-related issues and to facilitate climate action at a grassroots level.

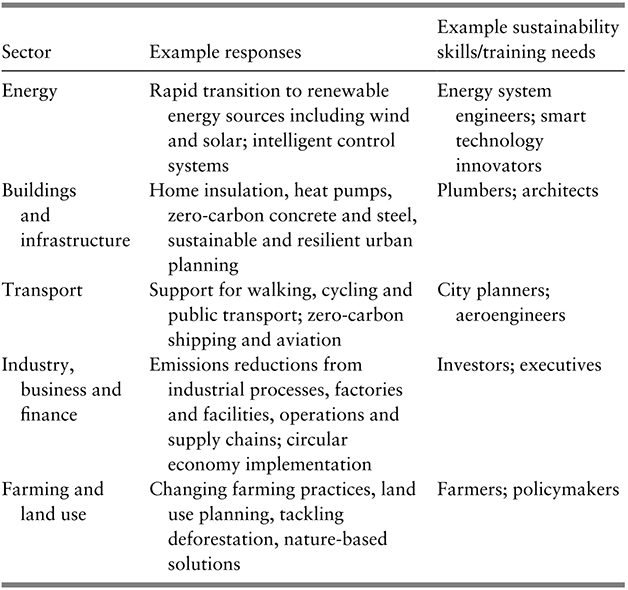

The solutions that have the potential to deliver a climate-resilient net zero future, and the skills and training required to support this vary between countries and sectors of the economy. Several examples relevant to the UK are provided in Table 1.1.

We need to reinforce the notion that every action counts. The challenges posed by climate breakdown and the destruction of nature are global and can therefore appear overwhelming – too great in scale for individual action to make a difference. Yet, while governmental response is required at an international level, much of the impact will ultimately come from a multitude of actions by individuals at a local level. This manifests in multiple ways; for example, in the UK, subsidies that supported the uptake of solar energy were enacted at a national scale, but the experience of having solar panels on a roof or in a field and the economic changes that the owner of the roof or field may experience are experienced locally. Similarly, whilst local projects can feel as if they are meaningless in the context of the whole challenge, they can in fact serve as meaningful and tangible beacons for change that can be replicated again and again.

This sense that individual actions matter is highlighted in the Ladybird Book on Climate Change (HRH The Prince of Wales et al., 2023): ‘Everyone must work towards stopping climate change and protecting and restoring nature. On our own and together, young and old, we can all help. Every day we can decide to do things that cut the amount of carbon dioxide we put into the atmosphere. Every day we can take positive steps to keep the natural world healthy. We have had a bad effect on the natural world for too long, and we need to stop now and instead work towards a better future’ (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Artwork from children at Fawcett Primary School Cambridge, inspired by page 42 from the Ladybird Book on Climate Change.

As a global society, we need people who have a variety of different skills, including a capacity for innovation, who can collaborate to respond to the challenges we face and to turn them into opportunities. This applies across business, finance, agriculture, policymaking and more, and it must encompass both technology and ideas. Market mechanisms have been developed to address disparities in consumption, for example through trading of carbon credits, but it has been argued that this can create an instrumental attitude towards nature and undermine a spirit of shared sacrifice. Radical new thinking is required to set a value framework for decision-making in a sustainable and equitable world. Human history is full of examples where we’ve done that: the debates around universal suffrage, the abolition of slavery, child labour and gender equality were not driven by cost benefit analysis. They were driven by a value framework that enables us to say this is the right thing to do.

In response to these challenges, we point to the importance of six key underpinning concepts, which could be supported through education:

1) Active citizenship. The voices of citizens need to be part of the decision-making framework. Education has a role in supporting people’s ability to make critical judgements and their ability to have a value-based framework which enables them to act in the face of knowledge. A values-led education would give people the tools and the ability to act when they are confronted by the realities and injustices that that trigger the need to act. In this way people around the world can be empowered to be responsible and informed citizens who can actively participate in the debate.

2) Creativity and resilience. We need people who can devise novel solutions to the challenges we face, and who can confront traditional orthodoxies and provide fresh approaches and frameworks. Young people need to have had the opportunity to develop their imagination and the technical skills which will enable them to turn innovative concepts into reality. Resilience is also key – the challenges we face are potentially devastating and existential in nature. This provides an emotional challenge as well as a practical one – we are going to need people who can be courageous in the face of adversity.

3) Knowledge and understanding. People need to have a clear understanding of the sustainability threats we face to enable them to be informed democratic citizens. Curricula need to be clear on the evidence base for the next decades’ challenges and the current thinking on how they might be addressed. People must acquire the relevant knowledge and skills to support future solutions, whether that is the knowledge required to support greener lifestyles (e.g. through dietary choices) or to install and use new technologies (e.g. heat pumps in homes) or practical skills required for new green jobs.

4) Listening and compassion. Widespread systemic change is required, varying according to geography and the socio-cultural factors at play in any one place. Understanding the impacts of policies required to enact this change on diverse groups of people will require radical listening. The existential nature of the environmental crises routinely inspires anxiety and fear for the future. We need people who can provide compassionate reassurance and empathy in challenging conditions.

5) Systems thinking and interdisciplinarity. The challenges we face are systemic and require holistic thinking that identifies root causes and solutions that address many different problems simultaneously. Whilst certain disciplines, like engineering, have very clear applications in this context, identifying robust and effective solutions will require adopting multiple disciplinary lenses. For example the social sciences can enhance understanding of how a new public transit system might be used, and the arts and humanities can help us understand our fundamental relationship with the environment.

6) Local action with global impact. Tackling the planetary emergency is going to require the global aggregation of many local actions. Everyone experiences the world at the local level, so policy changes enacted on a global scale are also experienced locally. This provides an important opportunity to develop a sense of individual agency and practical experience of instigating change. For example persuading a local authority or parish council to enact a policy change is excellent preparation for motivating change at larger scale.

The challenge that faces us as a global society is enormous, but it is not impossible. The responsibility to solve the interlinked environmental crises doesn’t and shouldn’t fall only on young people; however, they are the ones who will be most affected. Everyone can make a difference by helping to protect and preserve the natural world upon which we depend for our own survival. Educators have an opportunity to inspire and support young people with the understanding, confidence and optimism they will need to be active citizens, with the knowledge and skills to help design solutions and with the creativity and compassion needed to navigate a world that is changing rapidly and unequally.