0.1 A Greek Aeneid in the First Century CE

There are two competing starting points for the translation history of Virgil’s poems. One is Rome in the first century CE, the other in Ireland, at the far western edge of Europe some ten centuries later. Both translations are in prose. Seneca the Younger’s words in his Consolatio ad Polybium indicate that Polybius, the eminent freedman who served the emperor Claudius as secretary and researcher, produced a prose translation of the Aeneid in Greek, as well as a Latin translation of Homer.Footnote 1 Seneca refers to Homer and Virgil reaching a wider audience thanks to Polybius’ initiative (Ad Polybium 8.2); the significance of this becomes clear when Seneca praises

those poems of both authors [Homer and Virgil] [illa … utriusque auctoris carmina] which have been made famous by the industry of your genius [ingenii tui labore] … which you rendered in prose, keeping their attractiveness, even though their form disappeared [quae tu ita resoluisti ut, quamuis structura illorum recesserit, permaneat tamen gratia], because you achieved that hardest goal of transferring them from one language into another [illa ex alia lingua in aliam transtulisti] in such a way that all their fine qualities have followed you into foreign speech [omnes uirtutes in alienam te orationem secutae sint].

There is no other record of this early translation, but it accords with Pliny the Younger’s explicit recommendation of translation from Latin into Greek in Epistles 7.9, a practice which persisted through the centuries well into the Renaissance, as manifested in three sixteenth-century Greek translations of Virgil by English Catholics, for example.Footnote 2 It is noteworthy that in this brief mention Seneca raises many of the theoretical questions about translation that persist throughout the translation history of Virgil and indeed in the theorization of translation in general. These include the translator’s effort and talent, the choice of prose or verse to translate poetry, the distinction between form and appeal, and the question of what is lost in translation and what qualities of the original can still be conveyed through compensation. These issues will recur often in my discussion.

0.2 The Translation History of Virgil in the Western Tradition: How to Organize Such a Huge Topic

Before I discuss the second possible starting point of the translation history of Virgil, the eleventh-century Irish Imtheachta Aeniasa (‘Wanderings of Aeneas’), I set out the aims of this introductory chapter. My first aim is to give a sense of the geographical, linguistic and chronological ranges of my study. The translation history of Virgil is, obviously, an enormous topic extending to several thousand existing translations. Witness the number of items in Craig Kallendorf’s catalogue, A Bibliography of the Early Printed Editions of Virgil 1469–1850: he records about 2,500 translations down to the year 1850.Footnote 3 The seventeen decades since then have not seen any slacking in the rate of production, and indeed an ever-wider range of world languages is represented in more recent years. The linguistic scope of my project includes translations in Afrikaans, Argentinian and Colombian Spanish, Basque, Bulgarian, Castilian, Catalan, Croatian, Czech (Bohemian), Danish, Dutch, English, Esperanto, Finnish, French, German, Greek (Homeric, Doric and Katharevousa), Hebrew, Hungarian, Icelandic, Irish, Italian, Maltese, Middle Scots, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese (including that of Brazil), Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, Swedish, Turkish, Ukrainian and Welsh; I also mention dialect versions in Agénois, Burgundian, Corsican, Friulian, Narbonnais, Neapolitan, Occitan, Sicilian and Tuscan. While I am aware of translations in Arabic,Footnote 4 Armenian,Footnote 5 Bengali,Footnote 6 Chinese,Footnote 7 FarsiFootnote 8 and Japanese,Footnote 9 these are beyond my range in this study, which deals with the Western tradition of translation produced in European languages in Europe and the Americas.Footnote 10 Likewise, I exclude the fascinating question of engagement with non-European languages of the Americas, because this does not constitute translation as such; nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that Virgil is a critical tool of colonialism, as explored, for example, by Andrew Laird.Footnote 11 And not every language tradition of Europe exhibits translations of Virgil: I have searched in vain for a Yiddish Virgil.Footnote 12

It is important to recognize the limitations of even such a big book as this. In his introduction to Vertere: Un’antropologia della traduzione nella cultura antica (2012: vii–xvii), Maurizio Bettini does excellent service in unpacking the significance of the words for ‘translation’ in non-Western traditions, including those in India (ix–xi), in Arabic (xi–xii), in Nigeria (xi–xii) and in China (xii). He argues that the Western preoccupation with the ‘fidelity’ of translation(s) is not at all replicated in these four traditions, where ‘translation’ is metaphorized as ‘renewal’, ‘definition’, ‘narration’ or ‘disintegration’, and ‘turning’ or ‘change’, respectively; the Chinese imagery of the source text as the right side of the embroidery and the translation as the reverse is particularly striking. In other words, Bettini offers a salutary reminder of paths not travelled in the Western translation tradition. Moreover, he argues that the Western tradition conceptualized the practice of translation in an economic framework of minting and exchange (xv), which generated a concern with fidelity as the transference of value, a concern which is not an invariable parameter in world translation traditions.

Kallendorf’s scholarship is central to my project.Footnote 13 His careful recording of reprints and later editions allows the researcher to see patterns in the translation history of Virgil. For example, in the cases of landmark translations such as those of Joachim Du Bellay (French, 1552–60), Annibal Caro (Italian, 1581) and John Dryden (English, 1697), it is easy to discern which translations were repeatedly reissued by publishers over periods of years, decades or even centuries (names in bold have biographical entries in Appendix 1, pp. 827–45). This is doubtless an index of popularity, although without details of print run, format and price, one must be careful not to leap to conclusions. Once we have this added information, we are in a position to measure the relative success of different translations. We can be confident that printers did not go to the trouble and expense of reissuing books that were unlikely to bring them a good return. Kallendorf’s material also highlights peculiarities such as the different national tastes, for example, among the poems of the Appendix Vergiliana: virtually all the Italian translations from the Appendix are of the Moretum, while the French prefer the Culex, and the English and German traditions effectively ignore this material.Footnote 14

A brief overview will give a sense of the immense potential range of this project. Virgil’s poems, especially the Aeneid, had been translated many times long before the advent of printing, and they continue to be translated to the present day. A word on my definitions is in order here: I use ‘translation’ in the humanistic sense to denote a version that follows the Latin without significant additions or omissions, and I reserve ‘adaptation’ for medieval versions that show no such scruples and for later versions that take remarkable liberties with the Latin, including the travesties I discuss briefly in Chapter 4. I generally use the word ‘version’ as a larger, neutral category that can include translations and adaptations; I sometimes use it interchangeably with ‘translation’ for variety, and sometimes to indicate my scepticism about whether a particular translation deserves that label.Footnote 15 I trust that context will make clear my intentions.

Medieval adaptations of the Aeneid include the Middle Irish Imtheachta Aeniasa from the eleventh or twelfth century (Section 0.3), the mid-twelfth-century Roman d’Enéas in Old French (Section 0.4) and Eneit by Heinrich von Veldeke in Middle High German (Section 0.5), and Icelandic versions from the early thirteenth century. Italy produced fourteenth-century prose versions of the Aeneid, including one attributed to the Sienese Ciampolo di Meo degli Ugurgieri, written during 1316–21, and a compendium ascribed to the Florentine notary Andrea Lancia, but probably composed by several people during the years 1310–50, which derived not directly from Virgil’s text, but from a Latin prose reduction attributed to a monk named as Anastasio (or Nastagio).Footnote 16 The first verse translation is that of Tommaso Cambiatore (1430), although we can glimpse earlier versions of the Aeneas story in ottava rima in chronicles and narratives of human history starting with that of Armannino, a Florentine judge, written in 1325.Footnote 17 At the same moment in Spain, Enrique de Villena wrote his version in Castilian prose, divided into 366 chapters, while the ‘Lancia’ version generated a Sicilian Istoria di Eneas truyanu by Angilu di Capua di Messina. The earliest printed Aeneid, a loose adaptation in the medieval mode, was the printing in 1476 of the ‘Lancia’ Italian version, which was turned into French in 1483, which in turn was put into English by William Caxton in 1490 as The Eneydos of Vyrgyl. These versions followed on the heels of the editio princeps of the Latin text, which appeared in 1469.Footnote 18 These three remaniements (‘rehandlings’) all take striking liberties with the Latin text. For example, in the French Livre des Eneydes, printed by Guillaume Le Roy (who is sometimes cited as the translator), the author reorders the episodes into chronological sequence, relocates the journey of Aeneas to have him arrive in Lombardy, includes material not covered in Virgil, such as Aeneas’ wedding and Ascanius’ succession, organizes the material into chapters, thus obliterating the twelve-book construction, and amplifies the material devoted to Dido.Footnote 19

More rigorous translations of the Aeneid – versions recognizable as translations thanks to their hewing more or less closely to the Latin – soon appeared as Renaissance humanism took off: into French in 1500 (Octovien de Saint-Gelais, published 1509), into mid-Scots in 1513 (Gavin Douglas, published 1553), into German in 1515 (Thomas Murner), into Italian in 1534 (Book 4 by Niccolò Liburnio), into English in the 1540s (Books 2 and 4 by Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey, published 1554 and 1557), into Spanish in 1555 (Gregorio Hernández de Velasco), into Dutch in 1556 (Cornelis van Ghistele) and into Polish in 1590 (Andrzej Kochanowski).Footnote 20 The first complete Aeneid in English is that of Thomas Phaer and Thomas Twyne (1573). The production of Aeneid translations remained prodigious, even while Virgil was eclipsed by Homer during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and it continues apace.

Similar, though not identical, narratives apply to the Eclogues and the Georgics too, which, because of their subject matter, move in and out of favour more dramatically. The earliest versions of the Eclogues offer a snapshot of the range of possibilities.Footnote 21 The Italian translation by Bernardo Pulci, dedicated to Lorenzo de’ Medici, begun around 1470 and published in Florence in 1481/2, shows precision and concision in its terzine – for example, Pulci renders eleven Latin lines in six terzine – and is a competent attempt to render the Latin faithfully. This contrasts with the earliest Spanish attempt, that of Juan de Encina in 1496. His Imitación de las Églogas de Virgilio, included in his collection of poems called Cancionero (‘Songbook’), which was dedicated to the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, expands considerably, for example using three strophes of twelve lines for the first seven lines of Eclogue 2.Footnote 22 His domestications include what he calls ‘estilo rústico’ (‘rustic style’), with his shepherds sometimes using the dialect of Salamanca.Footnote 23 In the argumentos to the individual poems he applies the content to his own world; for example, in Eclogue 1 he interprets Meliboeus as representing rebel landowners displaced for conspiring with the king of Portugal; in Eclogue 2 he proposes that Corydon is the poet and Alexis the king, and in Eclogue 9 that Menalcas is the dethroned king of Grenada. Encina is typical of his moment: his version shows humanist and Italian elements blending with national Spanish characteristics, but in definitely Hispanized form.Footnote 24 The first Italian version of the Eclogues, then, looks ahead to Renaissance humanist principles, while the first Spanish version makes Virgil a fifteenth-century Cancionero. The first complete French Eclogues, published in 1516, mixes these characteristics. The author is Guillaume Michel de Tours, like Octovien de Saint-Gelais, one of the Grands Rhétoriqueurs who are precursors of the Pléiade literary movement.Footnote 25 But Michel’s book has a medieval look, with its Gothic characters and woodcuts, as well as a medieval mindset: each poem is followed by commentary offering exposition of its hidden sense. The translation itself, in bumpy decasyllables, is almost incomprehensible, bristling with Latinisms and padding – an example from Eclogue 5 shows two Latin lines expanded into seven in the French; without the Latin, which is printed as side notes, one would be lost. The first complete Eclogues in German offers yet another model. Johann Adelphus Muling’s translation, dating from 1508/9, is explicitly aimed at schoolchildren and adopts the same layout as Latin schoolbooks, presenting a literal prose translation with interlinear paraphrase and marginal commentary in smaller type and supplemented with Sebastian Brant’s woodcuts. This translation has no literary pretensions, but aims to be didactically functional within the institutional framework of contemporary schools, making the teaching and learning methods transparent for users.Footnote 26

The earliest Georgics are Foresi’s Italian version (1482) and Guillaume Michel’s French version (1519). The second half of the sixteenth century offers translations of the Eclogues in Spanish (1574), English (1575), Polish (1588) and Dutch (1597), and of the Georgics in German (1571), Spanish (1586) and English (1589). The earliest collected Works that I can identify is the French from 1529, consisting of Guillaume Michel’s Eclogues and Georgics with Octovien de Saint-Gelais’ Aeneid. The earliest single-authored collected works appear to be by Diego López (Spanish, 1600–1), Joost van den Vondel (Dutch, 1646) and John Ogilby (English, 1649). Even this selection of data hints at the dizzying possibilities for research on this topic. So it is proper that I indicate the parameters of my study.

My geographical scope extends from Russia and Ukraine in the east to the Americas in the west, including Brazil, formerly part of the Portuguese Empire, Argentina, formerly part of the Spanish Empire, and America during the era when it was a British colony; and in the north from Iceland, Norway and Finland southwards to North Africa, where a French translation of the Georgics was penned by a Parisian farmer in Tunisia. Another Georgics translation was undertaken in Changi Gaol and Sime Road Camp in Singapore during World War II. The presence of translations of Virgil in languages and dialects including Basque, Catalan, Neapolitan and Sicilian speaks to the cultural capital residing in Virgil’s poetry. Because of the wide geographical spread of my project, I have preferred to refer to individuals often known by Latinized names in their native forms because this reminds us of their location and nationality. For example, I refer to the Flemish scholar-printer Ascensius (Jodocus Badius Ascensius) as Bade (his name in French was Josse Bade), and to the Italian Aldus Manutius as Manuzio. Complexities have included the changing geopolitical denomination of territories, for example the interrelationships of the courts of Castile and Aragon with Catalonia, Naples and Sicily in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries; the fact that the countries we know as ‘Germany’ and ‘Italy’ did not exist until the nineteenth century; the encroachments by neighbouring powers that resulted in Poland and Lithuania being removed from the map for 123 years until 1918; the emergence of South Slavic states from ‘the former Yugoslavia’ in recent years, and so on.

My chronological range embraces the earliest extant adaptations, from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, down to translations of the present day, an era of continuing productivity: since the year 2000 at least eleven new English translations of the Aeneid have been published, including three by women, a phenomenon which raises questions of gender that I tackle later.Footnote 27 I use this chapter to register and reflect on the earliest adaptations of the Aeneid, dating from before printing in the West, but in the body of the book my main concern will be translations produced during the print era down to the present day, because the print era coincides with versions we can recognize as translations rather than adaptations. This will not preclude attention to a few translations that survive only in manuscript; these represent an important but as yet understudied area in which Stuart Gillespie and Sheldon Brammall are pioneers.Footnote 28

My second aim in this chapter is to indicate my framework and methodology (Section 0.6). Essentially, I use a model of reception theory as a development of reader-response theory which values translators as especially close and careful readers. I have learned much from the work of Lorna Hardwick in particular, whose Translating Words, Translating Cultures (Reference Hardwick2000) remains essential reading for anyone concerned with the translation of classical texts.Footnote 29 I am convinced of the bidirectionality of the process of classical reception theory, as articulated influentially by Charles Martindale in his seminal 1993 study Redeeming the Text: Latin Poetry and the Hermeneutics of Reception. We can ask questions about the influence of classical texts on later eras, but we must not underestimate the extent to which later remakings of classical texts affect our view and appreciation of those texts. This applies especially to translation.Footnote 30 To put it another way, the original text and its reworking in the form of translation operate ‘in a fruitful relationship of reciprocal enlightenment’.Footnote 31 The case for viewing translation as a crucial element within reception studies is made by Stuart Gillespie and developed by Craig Kallendorf when he argues for the value of ‘transformation methodology’, which views translation as a transposition from a ‘reference culture’ into a ‘reception culture’ that invariably involves fundamental change.Footnote 32 Both of these scholars have exercised a fundamental influence on my thinking about translation and both have also offered me enormous help and support. I devote a later part of this chapter to situating my approach theoretically, especially in relation to contemporary translation studies, a field which exhibits a particular concern with issues of ethnicity, gender, colonialism and empire, but also in relation to book history and intellectual history more widely. I shall indicate to what extent these issues are useful in the study of the translation-as-reception of Virgil.

My third aim is to account for the organization of the book by considering what it might have been (and is not), as well as what it is (Section 0.7). This section will indicate the principles of organization I settled upon and will include summaries of the ten following chapters, along with indications of the major and minor translations tackled in each. Already the reader will have gleaned that this book comprises numerous case studies. The biggest hermeneutic challenge of all is how to rise above the case study (Section 0.8). My interdisciplinary investigation attempts to generate a larger picture that contributes to Western intellectual history as well as challenging classicists and other scholars of literature to reassess the features of Virgil’s poems to which the translators respond. I therefore close this chapter by indicating the interpretative gains of this study and ways in which it opens up further avenues for exploration by other scholars.

But first I return to what can be regarded as the earliest extant translations of Virgil’s Aeneid, in Middle Irish, Old French and Middle High German, from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, if the term ‘translation’ is granted considerable latitude; as noted earlier, I regard these versions as adaptations. And here I should alert the reader that in this study I shall make several claims of ‘firstness’ for different translations with different qualifications. I discuss these three early versions here as a way of foregrounding some of the choices available to the translator and some of the issues that will be developed later in the book. Will the translation be in prose or poetry? If in verse, in what metre? Does the translator seek to domesticate the original to his/her own culture or does s/he prefer to make the translation sound foreign? While the metre-or-not decision is a simple binary, the domesticating-foreignizing decision evokes a spectrum or axes that might be plotted on a graph. Other axes include archaizing versus modernizing; expansion for clarity versus concision and precision; grandeur and elevation versus economy and naturalization; deferential literalism versus confident appropriation of the original. Some translators supplement the original with explanatory materials, while others operate with a notion of compensation in translation. It is always crucial to interrogate these terms and to trace the implications of any particular set of choices. With those issues in mind, I will now indicate the ways in which my three opening cases sample some of the central issues of the book as a whole.

0.3 Translation as Domestication: Aeneas in Ireland

It is a long way from Polybius’ translation in first-century Rome to eleventh-century Ireland, yet, as is well known, in those intervening years the island of Ireland played a major role in the preservation of classical learning in western Europe, thanks to its energetic missionary activity in founding monasteries in Britain and continental Europe, including Iona in Scotland, Luxeuil in Burgundy, Bobbio in Italy and St Gall in Switzerland.Footnote 33 Given that Virgil had long been a subject of monastic study in Ireland, it should be no surprise to discover that the earliest extant European version of the Aeneid is the Irish Imtheachta Aeniasa (‘Wanderings of Aeneas’), which dates from the eleventh or twelfth century.Footnote 34 Like most translations of the Aeneid, the Imtheachta Aeniasa heavily domesticates the Aeneid to the receiving culture, adopting the native prose form. Because Irish culture suffered less than most European cultures from the anxiety of influence of pagan literature, it was able to settle Greco-Roman material into the familiar native modes.Footnote 35 The Imtheachta Aeniasa was not alone: there were also Middle Irish versions of the De Excidio Troiae (Togail Troí), the Odyssey (Merugud Uilix), Statius’ Thebaid (Togail na Tebe) and Lucan’s Civil War (Cath Catharda), all of which are assimilated into the Irish narrative tradition. But the domestication of the Aeneid in Imtheachta Aeniasa goes a lot deeper than turning the ‘tawny jasper’ on Aeneas’ sword (fulua iaspide, Aen. 4.261) into red Irish ‘carbuncles’ (‘carrmogail’, IA 770) or having the Latins engage in the characteristic Irish sport of hurling (‘liathroiti’, IA 1553).Footnote 36 In this chapter I now devote attention to manifestations of the domestication performed in the Imtheachta Aeniasa because the phenomenon anticipates many of the domestications I discuss later.Footnote 37 Once I have outlined some of the features of the earliest appropriations of the Aeneid, I shall broaden my discussion to indicate the scope of my book and the methods deployed.

The author of Imtheachta Aeniasa is certainly capable of following the Latin very closely, as seen, for example, in the Polyphemus episode (IA 140–95, translating Aen. 3.588–683) or the games in Sicily (IA 970–1144, translating Aen. 5.104–544). But there are some significant omissions, abbreviations and additions, which reflect the Irish audience’s expectations. Episodes which would attract special attention in the later translation history of the Aeneid, such as the death of Priam, the death of Dido and parts of Aeneas’ visit to the Underworld, are abbreviated, with the first of these being mentioned only in passing (IA 589–91). The author is not interested in Virgil’s teleological view of Roman history, as Erich Poppe shows in his analysis of how the content of Book 8 is rendered in the Imtheachta Aeniasa: the description of the future site of Rome and the Venus and Vulcan episode are omitted and the description of the shield cut to just a few lines (IA 1960–4).Footnote 38 Surprisingly, given the Irish predilection for narratives of cattle-raids, the Hercules and Cacus story is omitted; this may be attributed to its delaying the narrative progression.Footnote 39 The author mostly ignores Roman customs and omits Virgil’s similes.Footnote 40

On the other hand, the Imtheachta Aeniasa makes notable additions to Virgil’s text.Footnote 41 Immediately striking are the alliterative phrases, often combined with doublets or triplets of adjectives in asyndeton, which are characteristic of older Irish narratives.Footnote 42 One example is the phrase ‘lúirech trebraid tredúalach’, denoting a breastplate, which occurs at least six times in the Imtheachta Aeniasa.Footnote 43 Extravagant strings of alliterative adjectives describing fierce fighting are typical: ‘robai cathugudh feigh feochair faeburda fergach fuilech foindmethi guinech crechtach crolinteach andsin’ (IA 2012–14; ‘and there was fighting sharp, wild, keen, ireful, bloody, reckless, incisive, wounding, gory’).Footnote 44 This powerful alliteration is found throughout, but especially in descriptions of warriors and their weapons, in compensation for the loss of Virgil’s similes. Thus Nisus and Euryalus are described in terms often used of warriors in native Irish sagas as ‘two points of contest and manslaying, two pillars of a battle, and two hammers for smiting and crushing foes’ (IA 2063–4).Footnote 45 The description of Pallas setting off with his Arcadian cavalry to accompany Aeneas back to the battlefield is a supreme example of expansive description replacing a simile.Footnote 46 The Latin is relatively brief (Aen. 8.587–91):Footnote 47

Ruden’s revised translation (Reference Ruden2021), which I use often, reads:

In the Imtheachta Aeniasa, as scholars observe, the opening of this passage is taken directly from the old Irish romance, Tochmarch Ferbe (Courtship of Ferbe), which narrates how Mani, son of Queen Maev, courts his beloved, the fair Ferb (IA 1924–9):Footnote 48

Comely was the youth that was in their midst. Golden hair upon him, slightly curling; a clear blue eye in his head; like the prime of the wood in May, or like the purple foxglove was each of his two cheeks. You would think that it was a shower of pearls that rained into his head. You would think his lips were a loop of coral. As white as the snow of one night, were his neck and the rest of his skin.

The passage continues (IA 1929–37):

There are fine [robes] long, almost white, to the extremities of his hands and his feet. A purple fringed mantle about him. A pin of precious stone set in gold upon his breast. A necklace of gold about his neck. A filmy silken smock close to his white skin. A girdle of gold with gems of precious stones about his loins. A gold-hilted sword on his body, its blade, having been bent back from point to hilt, straightens itself like a rapier. It would cut a hair on water; it would sever a hair upon a head, and would not cut skin; it would make two halves of a man, and he would not hear it till long afterwards.

The description of the sword here resembles the language used in Irish sagas to describe the sword of Socht, a noble youth in the court of Cormac whose sword, named ‘The Hard-headed Steeling’, was exceptionally sharp and had magical qualities.Footnote 49

Another feature familiar in medieval Irish texts was the incitement to battle. This inspires another addition: before the Trojans and Rutulians join battle in Book 10, the Imtheachta Aeniasa has Aeneas and Turnus addressing their troops where there are no such speeches in the Latin (Aen. 10.308–9).Footnote 50 Part of Aeneas’ speech illustrates characteristic linguistic features of Irish narratives, including alliterative phrases, multiple adjectives and colour terminology in descriptions and, according to Edgar Slotkin, is ‘composed entirely of formulas or formulaic expressions’ (IA 2454–63):Footnote 51

It is like you to show bravery. Royal, furiously-routing are your kings; mighty, unflinching are your heroes [‘Ad rigda ruaigmhera ba[r] riga, trena talchara bar taisigh’]; prudent and wise are your counsellors; heroic, eager, fiercely rough, your valiant warriors; sanguinary, brave, daring your battle-soldiers. Moreover, good is your collection of arms unto the battle; many are your beautiful, brazen hauberks. They are triple-braided, triple-linked with truly beautiful gilded helms [‘at iat trebraidi tredualacha co cathbarraib firailli forordhaib’].

Another important feature of native Irish sagas which is manifest in the Imtheachta Aeniasa is a deep interest in genealogy. This sees Aeneas often called ‘Ænias macc Ainichis’ (‘Aeneas son of Anchises’) and Ascanius’ genealogy stated in full (IA 2365–6) where Virgil just calls him Dardanius (10.133, ‘Dardanian’, i.e. Trojan). Most remarkable of all, Latinus’ ancestry is traced all the way back to Noah (IA 1478–80):Footnote 52

Laitin mac Puin meic Picc meic Neptuin meic Saduirn meic Pal loir meic Pic meic Pel meic Tres meic Trois meic Mesraim meic Caimh meic Noe.

Latinus, son of Faunus, son of Picus, son of Neptune, son of Saturn, son of Apollo[?], son of Picus, son of Pel, son of Tres, son of Tros, son of Mizraim, son of Ham, son of Noah.

I will return shortly to the possible significance of this.

So far the changes and additions mentioned are somewhat generic and apply to the Middle Irish versions of all the Greco-Roman epics listed earlier. More significant perhaps is the author’s intervention which sees Aeneas ‘transmuted into a traditional Irish hero’ with ‘the qualities of an Irish hero like Finn or Oisin’, which render him ‘more chivalrous and more faultless’ than in the Latin.Footnote 53 Thus in the Imtheachta Aeniasa Aeneas’ speech of despair in Book 1 is eliminated; Iarbas’ unflattering remarks in Book 4 are converted into praise; and in Book 10 Aeneas’ berserk rampage after the death of Pallas is rendered ferocious but not beyond moral bounds, by the omission of his taking captives for human sacrifice. In addition, the epilogue has him return Turnus’ body and weapons to the dead man’s father, Daunus.

Domestication manifests in form as well as content. The prose form of the Imtheachta Aeniasa assimilates it to Irish sagas, a genre which includes narratives that can be classified as ‘Destructions, Cattle-raids, Courtships, Battles, Cave-stories, Voyages’ and more.Footnote 54 The context of the preservation helps us understand the alterations in the translation. The only complete version survives in the fourteenth-century Book of Ballymote, where it appears at the end of the collection along with other classical stories in chronological sequence:Footnote 55 first the Togail Troí (Destruction of Troy, adapted from the De Excidio Troiae attributed to Dares Phrygius), then the Merugud Uilix (a version of the Odyssey), then the Imtheachta Aeniasa, and finally the Scéla Alaxandair (a compilation of the deeds of Alexander the Great).Footnote 56 The Book of Ballymote starts with Leabhair Gabhála (Book of Invasions) and includes Irish genealogical, historical and legal texts. This context argues for a desire to integrate the Imtheachta Aeniasa into a chronological assemblage of narratives about antiquity which privileges the narration of events over their interpretation (by contrast, for example, with Virgil’s teleological view of Roman history), and thoroughly adapts the work to the interests of the medieval Irish audience.Footnote 57

This appropriation explains why the Imtheachta Aeniasa presents the narrative largely in chronological sequence, instead of leaping in medias res, as Virgil does. It has a brief prologue and a briefer epilogue which appear to provide context and closure, respectively. The prologue, which depicts a debate among the Greeks about what to do with the Trojan survivors, presents the oddity (to our eyes, anyway) of introducing Aeneas along with Antenor as betrayers of Troy, a theme which is at odds with the presentation of Aeneas in the body of the work.Footnote 58 The epilogue starts by having Aeneas take Turnus’ body to his father Daunus for burial and concludes with genealogy and world history (IA 3213–17):

And from the seeds of Æneas, Ascanius and Lavinia have sprung Roman lords, and king-folk and rulers of the world from thenceforward till the judgment-day shall come. So that these are the wanderings of Æneas son of Anchises, as above. Finit [It is finished], Amen, finit. Solomon O’Droma nomine scripsit [by name wrote].

This framework manifests typical Irish concerns. Moreover, it explains why Latinus’ ancestry is traced all the way back to Noah: the author wishes to accommodate and integrate the classical texts into a comprehensive worldview that comfortably sets biblical and pagan material side by side.

The first translation of the Aeneid, then, certainly ‘naturalizes’ the text into ‘a thorough literary acculturation’ of the original.Footnote 59 While mostly keeping close to the Latin text, in both form and content, the author of the Imtheachta Aeniasa ‘has attempted to bring the Aeneid into the recognizable form and shape of an Irish saga’; the result is ‘not so much a translation from one language to another but from one culture to another’.Footnote 60 This domesticating process is repeated over and over in later translations, but always with differing particulars of domestication. Thus the Imtheachta Aeniasa presents a classic case of a translation situated towards the domesticating end of the domesticating-foreignizing spectrum proposed by translation theorist Friedrich Schleiermacher in the early nineteenth century, according to which the translator either moves the reader towards the author or the author towards the reader.Footnote 61 My study confirms that most translators set out to ‘domesticate’ Virgil’s poems, appropriating them to their own national literary conventions for a mixture of aesthetic, moral, ideological and patriotic reasons and often obscuring the quintessentially Roman features of the original. A few translators, preferring the foreignizing approach, have been brave enough to make their translations difficult in order to remind readers that they are engaging with literature produced by an alien culture; but, for the majority, the cultural capital gained from appropriating Virgil outweighs any such considerations. I address foreignizing translations in Chapter 9. For now, I shall glance at two further early versions of the Aeneid to indicate some of the varying manifestations of domestication: the Old French Roman d’Enéas and Heinrich von Veldeke’s Eneit in Middle High German.

0.4 Camille the Knight and Cerberus the Poison-Dripping Monster in the Roman d’Enéas

Like the Imtheachta Aeniasa, the Old French Roman d’Enéas domesticates the Aeneid, but in different ways, which reflect the concerns of its cultural milieu. And like the Imtheachta Aeniasa, the Roman d’Enéas was one of several classical reworkings, alongside the Roman de Thèbes (c.1150) and the Roman de Troie (1165). The Roman d’Enéas is an anonymous twelfth-century romance of about 10,000 octosyllabic rhyming couplets, written at or for the Plantagenet court of Anjou, probably between 1155 and 1160.Footnote 62 It follows the structure of the Aeneid but makes significant changes, including resequencing events into chronological order and adding 341 lines of epilogue. It is not a translation in the humanistic sense, but a typical medieval adaptation which eliminates much of the mythological schema, including dreams and visions, makes some Christianizing moves and is above all adapted for the medieval courtly context.Footnote 63 For example, it curtails Aeneas’ wanderings and omits the funeral games of Book 5, but expands the Judgement of Paris episode; it renders the duel between Aeneas and Turnus as a joust, with Lavine watching from her tower window; and it continues the narrative beyond Turnus’ death to the courtship and marriage of Eneas and Lavine. The poem is important for its focus on love, especially married love:Footnote 64 it inserts love dialogues between Eneas and Lavine, under heavy Ovidian influence, and thus turns Aeneas the warrior into Eneas the lover, reflecting the standard derivation of hērōs (‘hero’) from eros (‘love’) in this period.Footnote 65 In this way, the Enéas serves up material designed to be familiar and welcome to its audience.

The ideological freighting of the Enéas has been studied in depth. It has been argued that the poem contributes ‘to the myth of continuity that the Anglo-Norman ruling class promoted and to the privileging of lineage, and of primogeniture, that was so crucial to the Norman social and economic structure’.Footnote 66 On another, largely complementary, reading it is ‘the maturation of the knight Eneas’,Footnote 67 ‘fundamentally a narrative of a knight’s fulfillment of himself’ in a secular pilgrimage which sees him achieve ‘joi [joy] through love and war’.Footnote 68

To illustrate the kind of domesticating performed in the Enéas, I discuss two episodes, starting with the catalogue of the allies of Turnus (7.641–817) with which Aeneid 7 closes, which culminates in fifteen lines on the virago Camilla (7.803–17):Footnote 69

Here is Ruden’s translation (Reference Ruden2021):

By contrast, in the Enéas (which is not divided into books) the poet devotes about 150 lines to a lavish description of Camille (RdE 3959–4106). In this tour de force he takes Virgil’s bellatrix (Aen. 7.805, ‘female warrior’), who receives the same attention as the other allies, and renders her instead a female knight who receives as much detail as all the other knights combined. Clearly, the Enéas poet notices that Virgil’s Camilla processes on horseback, since she is agmen agens equitum (7.804, ‘leading the cavalry’), and he takes this as a cue for a memorable and influential domesticating elaboration which includes lavish attention to her horse.Footnote 70

Virgil’s description falls into three parts: first, Camilla as virago who prefers warrior-like to womanly pursuits (7.803–7); second, her speed, conveyed with a double simile (7.807–11); third, the reaction of amazement at her regal and warlike appearance (7.812–17). The Enéas poet starts on roughly the same track as Virgil, but immediately makes her a knight (RdE 3971–6): ‘She had no interest in any women’s work, neither spinning nor sewing, but preferred the beauty of arms, tourneying, and jousting, striking with her sword and the lance: there was no other woman of her bravery.’Footnote 71 Likewise, the poet ends by describing the people’s amazement as they seek vantage points to catch sight of her (RdE 4085–98). But most of the 150 lines are devoted to a long description of her beauty (RdE 3987–4084), a feature not even mentioned by Virgil. This is the most heavily domesticating section: it incorporates a highly conventional feature which would have been familiar to the twelfth-century audience, namely a detailed physical portrait starting from the top of the head and proceeding methodically down the body.Footnote 72 In the case of Camille, because she is represented as a female knight, this description extends to include her horse too, who receives thirty-eight lines. The description of Camille begins: ‘No mortal woman was her equal in beauty. Her forehead was white and well formed, the part of her hair straight on her head, her eyebrows were black and very fine, her eyes laughing and full of joy.’ It proceeds to detail her nose, mouth, teeth, hair, hair-braid, dress, belt, hose, shoes, shoelaces and cloak.Footnote 73 Then her palfrey receives a similar treatment, likewise from head to foot: ‘its head was white as snow, the foretop black, its ears both all red. Its neck was bay and very large, its mane blue and gray in tufts, the right shoulder all gray and the left, wholly black’ (RdE 4050–6) and so on, including its bridle, reins, saddle and stirrups.Footnote 74 This gorgeous description completely replaces the middle section in Virgil which depicts Camilla’s speed in running (Aen. 7.807–11). This treatment of Camille by the Enéas poet, along with his lavish description of her tomb and casket (RdE 7531–724), which corresponds with nothing at all in Virgil, illustrates eloquently how the Aeneid is readily adapted to contemporary concerns by translators.Footnote 75

My second episode from the Enéas, the description of Cerberus, not only reflects domesticating tendencies but also shows how the poet elaborates his text using accretions from other sources, in this case from Ovid, but elsewhere from commentators including Servius.Footnote 76 At Aeneid 6.417–25 Virgil offers the briefest description of Cerberus in his narrative of how the Sibyl drugs the dog with a honeyed cake:Footnote 77

But, as Raymond Cormier shows, the Enéas poet expands the description massively and vividly to make Cerberus revoltingly monstrous, before having the priestess charm him to sleep with a spell (RdE 2557–86):Footnote 78

Caro steered and rowed until he set them on the other shore. They left the skiff and arrived at the gate where Cerberus was gatekeeper. His duty was to guard the gate. He was ugly beyond all measure, and of a very horrible shape. His legs and feet were all hairy, with hooked toes and talons like a griffon. He had a tail like a bulldog, a pointed and twisted back, and a fat, swollen belly. On his back was a hump, and his chest was sunken and withered. He had narrow shoulders, but great arms with hands like hooks, three large, serpentlike necks, hair of snakes, and three heads like those of a dog: there was no creature so ugly. His habit was to bark like a dog. From his mouth would fall a froth, from which grew a deadly and evil plant. No man drinks of that plant without being drawn to death: no man can taste it without death. I have heard it called aconite; it is the herb which stepmothers give their stepchildren to drink.

The amplification is achieved by working in material from Ovid’s Metamorphoses 7.406–20, where Medea mixes poison for Theseus; Ovid explains the origin of the poison from the flecks of foam that flew from Cerberus as Hercules hauled him from the Underworld. Passages like this give a glimpse of the working methods of the poet: clearly, the strangeness of this description appealed to the medieval audience.Footnote 79

Like the Imtheachta Aeniasa, the Roman d’Enéas naturalizes the Aeneid to meet the expectations of its own audience, but the alteration of the original is more profound. This is evident particularly in its dissatisfaction with the ending of the Aeneid, which leads to the addition of a much longer epilogue than in the Irish version. Most of the epilogue of the Enéas is devoted to the love agonies of Lavine and Eneas: after Turnus’ death, the barons quickly submit to Eneas (9815–38); then comes Lavine’s long monologue (9839–914), followed by Eneas’ lovesick monologue (9915–10078) as they pine for one another (10079–90); finally, the joyful wedding and coronation take place (10091–130), and a brief coda glances towards the future foundation of Rome (10131–56). In other words, 250 of the additional 341 lines deal with the churned-up emotions of Lavine and Eneas. As I shall show in Chapter 7, dissatisfaction with the ending of the Aeneid leads to other kinds of supplement by later translators.

0.5 Veldeke’s Middle High German Eneit: Achieving Closure

My third early version of the Aeneid is the Eneit or Eneasroman, the first courtly romance in a Germanic language. This was closely based on the Roman d’Enéas and written within a couple of decades, during the years 1170–85.Footnote 80 It thus introduces the important and complex phenomenon of translations of translations, sometimes referred to as retranslations or secondary translations, a topic mentioned in Chapter 4.Footnote 81 The author was a knight from the hamlet of Veldeke, not far from Maastricht (modern Netherlands) and Hasselt (modern Belgium), both of which display statues celebrating the poet. He is claimed by both Dutch and German literary critics as Hendrik van Veldeke or Heinrich von Veldeke, respectively.Footnote 82 Veldeke (c.1145–c.1210), who also wrote a religious poem in Low German and love songs which idealize courtly love (‘Minnesang’), is celebrated for his importance in Middle High German literature and praised as the founder of German courtly literature by the author of the Tristan romance, Gottfried von Strassburg (Tristan 4734–43):Footnote 83

I hear him praised by the best poets, the masters of his time and of the present. They maintain that it was he who made the first graft on the tree of German verse and that the shoot put forth the branches and then the blossoms from which they took the art of fine composition.

The number of manuscripts of the Eneit that survive bear this out.Footnote 84 This claim for the foundational status of a version of the Aeneid in a national literature is the central topic of my first chapter.

The Eneit shows knowledge of Virgil and Ovid, Servius, Dares and Dictys, as well as earlier German poetry, but its dominant point of reference is the world of twelfth-century French romances, including the Roman de Thèbes and Roman de Troie.Footnote 85 The Eneit thus epitomizes the phenomenon of ‘Germany [being] flooded by the influence of the fashionable courtly poetry of France’ at the turn of the twelfth into the thirteenth centuries, which manifested in fashion, clothing and armour as well as literary forms.Footnote 86 To give one example, in the case of memorial architecture, Veldeke follows his model closely. His handling of the tomb of Camille (9385–574) resembles that in the Enéas (7531–724) in length and in many features, including the red lamp hanging from the gold chain and the mirror on top, but with different emphases. Veldeke adds the information that Camille had her tomb constructed by an architect called Geometras and he catalogues in loving detail the valuable gems and materials used, including jasper, marble, porphyry, rubies, sapphires, emeralds, chrysolites, sards, topazes, beryls, sardonyx, gold and copper,Footnote 87 whereas the Enéas poet is more interested in the stone carvings than in the materials used and includes a lavish description of Camille’s clothing, coffin and epitaph. But the two medieval versions share a deep interest in wondrous architecture.

Veldeke’s Eneit follows the Roman d’Enéas but is significantly longer (13,528 lines opposed to 10,156).Footnote 88 He abridges some episodes, in particular mythological passages; for example, the Judgement of Paris is reduced from ninety-nine to thirteen lines. In other places he expands, developing the knighting of Pallas from five lines in the Enéas (4810–14) to twenty-nine (Eneit 6265–93), for instance. He thus continues the Enéas’ process ‘of giving the story a medieval orientation in that he further suppressed classical material that was foreign to his audience and expanded scenes, such as those dealing with festivals and military operations, with which it was familiar’.Footnote 89 All this despite his claim in his epilogue that ‘he undertook to tell it just as he found it. That is how he presented it, and he said nothing that he did not read in the book’ (13519–23).Footnote 90 I will return to this locus of expansion in a moment.

Like the Enéas, the Eneit is in rhymed couplets, mostly of seven or eight syllables, in an adaptation of the French romance epic line.Footnote 91 It deploys the alliterating word-pairs which are characteristic of older German poetry, such as ‘von siten und von sinnen’ (3663, ‘in manner and in thought’), ‘habe unde bihalte’ (5393, ‘have and hold’, of Latinus’ land and daughter), ‘als vmbe den lewen vnd vmbe daz lamp’ (11330, ‘between the lion and the lamb’, of uneven pairing in battle) and ‘slege grimme vnd groz’ (12367, ‘raging and intense blows’, of the duel between Eneas and Turnus); it has been suggested that the alliterating pairs reflect the rhymes of the Enéas.Footnote 92 The style and syntax of the Eneit are more casual and conversational, with more filler rhymes than the Enéas, and with chatty suggestions to his readers to refer to the Latin for more details, for example:

It would take too long to tell how the fortress was built, so we shall leave out much that Vergil says of it in his books and shorten the account to a moderate length. … Whoever is surprised at this and wants to look it up should go to the books that are called The Aeneid: he can be sure of it after reading such testimony as is written there.

The most significant difference between the two medieval poems is that Veldeke’s translation becomes more independent as it proceeds, a point I will return to shortly.

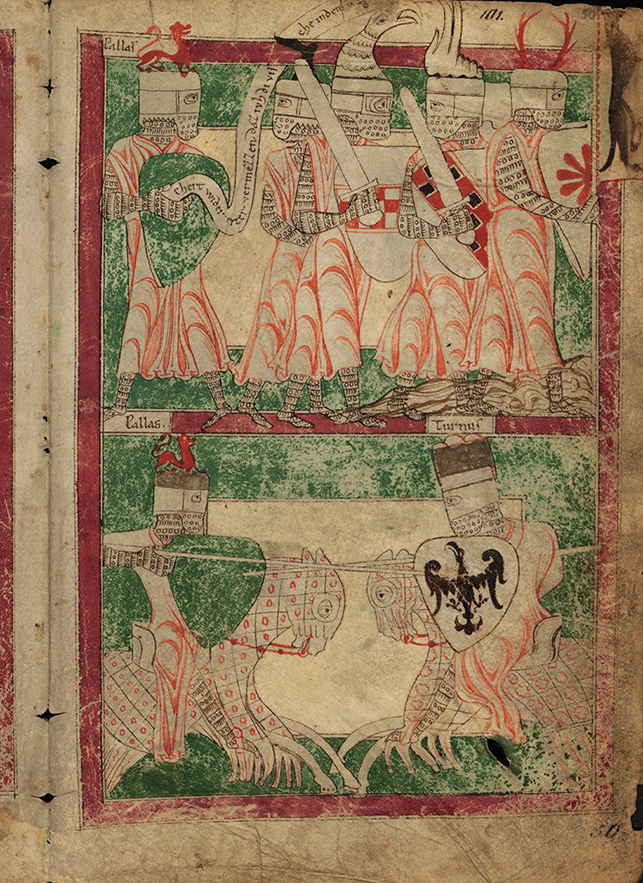

Veldeke’s central concern is to situate his knight Eneas, along with other ‘heroic seekers’ including Dido, Pallas, Camille and Turnus, within the new value system of courtly love and courtly ideals and generally to construct the idealized warrior-courtier in terms familiar to his audience.Footnote 93 Eneas has thus been seen as the prototype of the ‘Ritter’ (‘knight’) – even his horse is ‘ritterliche’ (7787) – and the Eneit as an apologia for the values associated with ‘Geblütsadel’ (‘nobility by blood’).Footnote 94 This is partly done by using familiar titles, such as ‘Herr Eneas’ (37), ‘frǒwe Dido’ and ‘herre Cupido’ (863–4), and accessories, for example the Castilian and Arabian horses given as gifts (686–9), the tapestries and quilts in the ladies’ quarters (12932–9), and the processions accompanied by fifes, trumpets and stringed instruments (e.g. 12847–9). The beautifully illustrated Berlin manuscript, which dates from the early thirteenth century, offers wonderful depictions of the central characters rendered in contemporary mode, including the image of Pallas facing TurnusFootnote 95 (Figure 0.1). Significantly, the eagle on Turnus’ shield, which could be termed the Reichsadler (‘Imperial Eagle’), was in the twelfth century associated with the Holy Roman Empire (Figure 0.2).Footnote 96

Figure 0.1 Turnus’ shield in Heinrich von Veldeke’s German version of the Aeneid. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

Figure 0.2 Analogies from German heraldry for the eagle on Turnus’ shield. Volborth 1981, illustrations 280 and 310.

Veldeke likewise embeds the story in the German legal context which would be familiar to his audience: he emphasizes that Latinus had promised his daughter to Turnus in a legal contract which he then breaks, thus perjuring himself; Turnus refers repeatedly to the contract and persists in the conflict because he believes himself to be in the right.Footnote 97 For Veldeke, the male ideal is a noble man with self-control (‘mâze’), discipline (‘zuht’) and refinement of manners (‘höveschiet’) in both wartime and peacetime.Footnote 98 As John Yunck remarks, in his concern for ‘the external decorum of courtly life’ Veldeke makes characters’ conduct ‘more correct or more gracious’ than in the Enéas, so that he, for example, ‘suppresses the grosser parts’ of Amata’s conversation with Lavine about Trojan homosexuality, ‘curtails Tarc[h]on’s insulting address to Camille’ and ‘repeatedly stresses Eneas’ courtly … qualities of graciousness, generosity, and Festlichkeit’ (‘joy’).Footnote 99

That said, he uses a lighter touch in two episodes which are not central to Eneas attaining his kingdom, which is Veldeke’s main narrative goal, namely the journey to ‘hell’ (the Underworld) and the Lavinia romance. In the latter, Veldeke’s Amata is ‘coarse and crude’, Lavinia is ‘unbelievably naïve’ and ‘the middle-aged warrior Aeneas fits the role of the passionate suitor so poorly that even his own men laugh at him’.Footnote 100 In the former, Veldeke entertains his audience ‘with monsters and horrors that are so grotesque as to be comical, and with a hero who is sufficiently frightened to be downright amusing’.Footnote 101 His Cerberus fills Eneas with such dread that he dares not approach (3206–38):

You would not believe how horrible he appeared with his three large and terrible heads. … His eyes glowed like coals; fire shot from his mouth and reeking smoke from his nose and ears: take note of that. How strong and hot was he? Enough so that Sibyl and Aeneas were scalded by the heat. His teeth gleamed in the fire like iron. This devil was monstrous. He was shaggy all over; not as the other beasts one sees, but as I shall tell you. His body was covered with snakes: long and short, large and small, even on the arms, legs, hands, and feet. We can tell you, because we have read it in books, that he had very sharp claws instead of fingernails. He spewed foam from his mouth that was hot, pungent, and bitter. He would have been a poor neighbor.

Comparison with the Enéas version (see earlier, pp. 22–3) reveals similarities and differences; for example, Veldeke excludes the aconite of the Old French poem.

Veldeke’s handling of the end of the poem manifests well his domestications of the material along with important differences from his Old French model. First of all, consider the duel between Turnus and Eneas to decide who will wed Lavine and become the next king of Italy. For Veldeke, the duel is an ordeal consisting of trial by combat, in which God will reveal the law (‘daz got daz rehte bescheine’, 8614), and which reflects measures taken in twelfth-century Germany to limit feuding and codify conflict.Footnote 102 In both medieval versions, as in the Aeneid, Eneas is tempted to grant Turnus’ request for mercy until he sees the spoils Turnus took from the corpse of Pallas. In the Enéas the earlier despoiling of Pallas’ ring is represented as an act of folly (‘Por fol le fait’, RdE 5770), but in the Eneit it is portrayed as an evil act (‘bosliche’, Eneit 7617) and ‘one of the worst crimes imaginable’: it broke a German law that viewed theft from a corpse as heinous.Footnote 103 Thus Turnus is represented as morally culpable and lacking in self-control, while Eneas changes from a flawed to a flawless hero in the final pages.Footnote 104 In the Old French poem, when Eneas sees Pallas’ ring he turns ‘all flushed with anger’ (‘toz teinst d’ire’, RdE 9800)Footnote 105 before he kills Turnus, whereas in the Eneit he behaves calmly, saying:

It won’t do. There can be no peace between us here, for I see the ring I gave to Pallas, whom you sent to his grave. There was no need for you to wear the ring of one you killed while he was aiding me. It was evil greed, and I tell you truly that you must pay for it. I shall not berate you or speak with you any longer, but only avenge the brave Pallas.

He then decapitates Turnus. Within Veldeke’s German framework, Eneas exercises the right to punish Turnus for his crime in the manner of a judge enacting divine law and his victory confirms that he is a divinely elected king.Footnote 106

The differences between the Enéas and the Eneit are still more evident in the epilogue. Veldeke appears much more dissatisfied with Virgil’s ending than the Enéas poet is and his epilogue is nearly three times as long (921 lines instead of 341) as he sets out to tie the loose ends and bring the poem to a suitable close. After Turnus’ death, he includes an encomiastic lament for Turnus (Eneit 12607–34). He drastically reduces Eneas’ love agonies from 172 to 38 lines and instead has Eneas, escorted by 500 knights, call on Lavine and present gifts, an episode of pomp and largesse extending for more than 200 lines (Eneit 12781–13006). He shortens the conversation between Amata and her daughter (Eneit 13012–92), and then devotes 200 lines to a lavish description of the wedding, especially the feast, games, songs, dancing and gift-giving (13093–286), including a comment, piquant given that this is an addition to the original (13133–49): ‘It was a great feast with a very large number of seats, and it began in splendor …. If someone wanted to take the trouble to tell about all that was served there, it would be a long story. I shall say only that they got too much to eat and drink.’ Veldeke reports Eneas’ happiness as he becomes king and constructs his castle at Albane, then devotes 100 lines (13321–420) to cataloguing his descendants, including Romulus and Remus who ‘together founded the city of Rome’ (13370–1), Julius Caesar ‘who conquered much of the world’ (13389) and Augustus under whom ‘peace and justice prevailed’ (13406). The climax of this section is highly domesticating for his Christian readership in the way it links the story of Eneas with the birth and death of Christ:

In those days the Son of God was born in Bethlehem and crucified at Jerusalem, which saved us all, for he freed us from terrible distress by overcoming through his own death the eternal death that Adam passed down to us. He thus redeemed us. This is a great support for us if we will hold fast to it. May his grace ordain this and strengthen us to such works as our souls need. Amen. In nomine domini. [In the name of the lord.]

Veldeke is the first of many translators to yoke his translation to his religious beliefs.

But this closural gesture is not yet the close of Veldeke’s poem. He wraps up with a personal assertion, so strong as to betray defensiveness, of the reliability of his account of ‘Herr Eneas’ as derived from the French book (he calls it ‘der … welschen büchen’, 13507), which, he indicates, was itself based on the Latin text (13491–528); he appears to wish to share responsibility for any errors with his models.Footnote 107 At the end of this section he declares, ‘hie sei der rede ein ende’ (‘Let this be the end of the story’). But we are still not at the end. There follows a final section (13529–44), which maintains the shift from first to third person in the previous section, which describes the circumstances of composition, including the theft of the book for nine years. We will later (in Chapter 7) encounter other versions that evince a similar concern with closure.

What is especially significant in Veldeke’s closural moves is his linking the story of Aeneas with his own world. I have already noted his chronological alignment of Augustus and Christ, which reflects his Christian milieu. A little earlier, he compares the wedding of Eneas and Lavine to the feast of Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa at Mainz in 1184:

Indeed, I never knew of a celebration anywhere else that was as large as that held by Aeneas except the one at Mainz where Emperor Friedrich knighted his sons. We don’t need to ask about it because we saw it for ourselves. It was matchless: goods worth many thousand marks were consumed or given away. I don’t believe anyone alive has seen a festival more grand; of course, I can’t tell you what may happen in the future. Truly, I never heard of a knighting ceremony that was attended by so many princes and people of all kinds. There are enough still who remember it well. It brought Emperor Friedrich such honor that one could indeed keep saying more wondrous things about it until doomsday, and without lying. Over a century from now they will still be telling and writing accounts of it, but we cannot know what they will report.

Earlier still, he permitted himself a similar reference to contemporary events in his extended description of the tomb of Pallas (8273–408), in a close imitation of the Enéas (6409–536). Both descriptions pay lavish attention to the materials used, although the gems and materials they name differ somewhat (the Eneit has crystal, jasper, coral, ivory, porphyry and sard; the Enéas has jacinth, beryl, silver, ebony and copper) in addition to the marble, gold and amethyst found in both texts, and both pay special attention to the red lamp hanging from a gold chain with an asbestos wick, which is claimed to burn forever. But Veldeke adds additional material from the source, William of Malmesbury, that the flame lasted until the day Pallas was found by Emperor Friedrich after his coronation in Rome (8392–408):Footnote 108

It was a great wonder that this should keep burning as long as he [Pallas] lay there under the earth and still not burn out, for we know that more than two thousand years had passed before Pallas was found. However, as soon as they opened the tomb and lifted the casket lid, the wind rushed in, and they saw the light fade away as the wick turned at last to ashes and smoke.

In other words, Veldeke is clearly competing with, and correcting, his model and at the same time asserting Friedrich’s era as the culmination of history.

These three early cases of Virgil adaptations illustrate vividly some of the manifestations of domestication, by which I mean that they move the original text closer to new readers rather than attempting to move the readers towards the ancient text. These early domestications contributed powerfully to the Aeneid’s survival and influence on European vernacular literature, a topic explored in Chapter 1. Translation as domestication is one of a number of fruitful frameworks offered by translation theory, to which I now move.

0.6 Theorizing Translation

It is tempting, when discussing translations within a theoretical framework, to construct binary oppositions, such as ‘domesticating’ and ‘foreignizing’, to name the important reformulation of Friedrich Schleiermacher’s ideas offered by Lawrence Venuti.Footnote 109 In Table 0.1 I present a number of such binaries that have been proposed. Translations can be ‘literal’ or ‘free’, ‘alien’ or ‘native’, ‘difficult’ or ‘accessible’; they can involve ‘under-translation’, when the individual elements of the text are privileged over the whole in a more or less literal rendering, or ‘over-translation’, which involves a focus upon the whole at the expense of its parts.Footnote 110 In essence these are reworkings of the antithesis proposed by Cicero when, in a discussion of his own translations from Greek into Latin, he says nec conuerti ut interpres sed ut orator (De optime genere oratorum 14). By ‘I did not translate them as an interpreter but as an orator’, he distinguished literal translation from free translation, preferring the latter.Footnote 111 While these binaries may offer useful starting points, it is preferable to think in terms of a spectrum which allows for middle ground. This middle ground is, according to Australian theoretician Anthony Pym, neglected by some translation theorists, although it constitutes the ‘intercultures’ that translators typically inhabit.Footnote 112 As context for my study of Virgil there follows an overview of some influential theoretical frameworks for understanding European translation practices. There are many books that tackle this complex topic; here my purpose is to provide an orientation for readers not deeply familiar with this material.Footnote 113

Table 0.1 Binary typologies of translation

I start with the schemata offered by three major authors who themselves wrote translations, Dryden, Goethe and Nabokov, schemata which consist of different threefold divisions. I will come to theoreticians shortly, but given the tensions and contradictions between translation theory and translation practice, I privilege the views of authors with personal experience of translation.Footnote 114 First, I look at John Dryden (1631–1700), whose 1697 Works is one of the leading translations of Virgil. In his ‘Preface to Ovid’s Epistles’, published in 1680, Dryden identifies three main types of translation, with exemplars:Footnote 115

All Translation I suppose may be reduced to these three heads. First, that of Metaphrase, or turning an Authour word by word, and Line by Line, from one Language into another. Thus, or near this manner, was Horace his Art of Poetry translated by Ben. Johnson. The second way is that of Paraphrase, or Translation with Latitude, where the Authour is kept in view by the Translator, so as never to be lost, but his words are not so strictly follow’d as his sense, and that too is admitted to be amplyfied, but not alter’d. Such is Mr. Waller’s Translation of Virgils Fourth Aeneid. The Third way is that of Imitation, where the Translator (if now he has not lost that Name) assumes the liberty not only to vary from the words and sence, but to forsake them both as he sees occasion: and taking only some general hints from the Original, to run division on the ground-work, as he pleases. Such is Mr. Cowley’s practice in turning two Odes of Pindar, and one of Horace into English.

Dryden’s category of ‘Metaphrase’ can be identified with what I will call ‘literal’, ‘literalist’ or word-for-word translations, which I discuss in Chapter 9 (pp. 674–90 and 726–68). What he calls ‘Imitation’ amounts to versions that are too freely inventive to merit the label ‘translation’, which applies to the medieval texts surveyed in this chapter. He proceeds to expand upon these ‘two Extreams’. He proposes that the ‘servile, literal Translation’ involves difficulties that make the experience ‘much like dancing on Ropes with fetter’d Leggs’, while ‘Imitation’, which he glosses as ‘this libertine way of rendring Authors’, entails ‘the greatest wrong which can be done to the Memory and Reputation of the dead’.Footnote 116 Dryden’s middle way, which he espouses in at least some of his translations, including The Works of Virgil, he calls ‘Paraphrase’. While ‘Paraphrase’ is perhaps a misleading term in the twenty-first century, we can easily enough see what it denotes in practice. Dryden indicates that by ‘Paraphrase’ he means that he works ‘with Latitude’ but not with excessive ‘liberty’.Footnote 117 Certainly in his Virgil translations he follows the Latin text closely enough to count as a translation, while at the same time taking certain liberties with the original that he felt were warranted.

Two other poet-translators add different categories, though each proposes a threefold division. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) in Noten und Abhandlungen zum besseren Verständnis des West-östlichen Divans (Notes and Treatises for a Better Understanding of the West-Eastern Diwan, 1819) ranked in a hierarchical sequence three different methods of translating poetic works: ‘identische Übersetzung’ (‘identical translation’), ‘parodistische Übersetzung’ (‘transformative translation’) and ‘schlicht-prosaische Übersetzung’ (‘simple prose translation’).Footnote 118 The choice of ‘simple prose’ I discuss in Chapter 8; Goethe’s spectrum between ‘literal’ (‘identische’) translations and much freer ones (‘parodistische’) is reflected in my discussion in Chapter 9 (pp. 674–90) of the tension between the literalists and ‘les belles infidèles’. Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977), in the introduction to his controversial English translation (1964) of Alexander Pushkin’s Russian verse novel Eugene Onegin, identifies three different types of poetic translation:Footnote 119 (1) paraphrastic, (2) lexical and (3) literal. Nabokov appears to use ‘paraphrastic’ in the same sense as Dryden, and his category of ‘literal’ translation matches Dryden’s category ‘Metaphrase’. What is new here is his middle category, which involves rendering the basic meaning of words and their order, which is work that a well-programmed machine can do. For Nabokov, only the third category, the ‘literal’ translation, is a true translation.

These three different frameworks by major author-translators between them produce five categories of translation: (1) Nabokov’s ‘lexical’ translation, such as a crib with the words put in sequence; (2) prose translation; (3) literal or ‘identische’ translation (Dryden’s ‘Metaphrase’); (4) paraphrase; and (5) imitation (Goethe’s ‘parodistische’). My study will pay only fleeting attention to (1), when I consider paratexts and readers’ aids in Chapter 7, and not a great deal to (2), which features in my discussion of metrical choices in Chapter 8. Translations in categories (3) and (4) are my central focus, while (5), which I consider beyond the scope of this study, features only in the specific form of travesties, discussed briefly in Chapter 4.Footnote 120

With these parameters in mind, and privileging the idea of a spectrum rather than a binary opposition, consider the frequently cited formulation offered by the German philosopher Friedrich Schleiermacher Schleiermacher (1768–1834) in his 1823 lecture to the Berlin Royal Academy of Sciences entitled, ‘On the Different Methods of Translating’ (‘Ueber die verschiedenen Methoden des Uebersetzens’):Footnote 121

Either the translator leaves the author undisturbed insofar as this is possible and moves the reader in his direction, or he leaves the reader undisturbed and moves the writer in his direction.

This formulation was actually inspired by Goethe, writing in 1813, who is rarely given the credit for it. Goethe wrote:Footnote 122

There are two maxims in translation: one requires that the author of a foreign nation be brought across to us in such a way that we can look on him as ours. The other requires that we ourselves should cross over into what is foreign and adapt ourselves to its conditions, its peculiarities and its use of language.

Venuti took up Schleiermacher’s idea in his 1995 book The Translator’s Invisibility.Footnote 123 While Venuti’s focus is mainly on postcolonial translations, his framework is nonetheless useful for earlier material too: he directs us to consider what degree of difficulty the translator imposes on her/his readership. This framework points to the comfort of the reader: is the translator more or less ‘invisible’ (to use Venuti’s term) or is the reader constantly reminded that s/he is engaging with a text produced in another language from another culture?Footnote 124

The challenges of translation and the dangers of going too far in either direction are expressed vividly by the Prussian philosopher and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835), founder of the Humboldt University of Berlin:Footnote 125

To me, all translating seems simply to be an attempt to solve an impossible problem. Thus every translator must always run aground on one of two reefs: he either adheres too closely to the original, at the expense of the taste of his nation; or he adheres too closely to the characteristics of his nation at the expense of the original.

His terminology of national interest inevitably reflects his nineteenth-century context; in Chapter 1 I explore the intersection between Virgil translation and nationalism, a concept that predates the rise of the modern nation state, as I explain there. A more nuanced way of articulating this idea is Venuti’s:Footnote 126 ‘Translation can never simply be communication between equals because it is fundamentally ethnocentric.’

While the idea of a spectrum encompassing the various choices open to a translator makes the process of translation sound like a horizontal exercise, many and varied asymmetries often render translation inferior, marginal and peripheral.Footnote 127 So it should not be surprising that much of the imagery used to theorize translation activity involves a hierarchy in which the translation is inferior to the original and different kinds of translation can be ranked vertically. I should note here that current translation theory is averse to the hierarchical term ‘original’ and prefers to substitute a term such as ‘prior text’ to avoid ‘reify[ing] a hierarchy of writerly value’.Footnote 128 I choose to persist with the term ‘the original’ not because I believe that translations cannot be original works in their own right, but because in this very particular case the prestige and authority of Virgil does usually enact a hierarchy.Footnote 129

In a brilliant article, ‘Images of Translation’, the Belgian translation theorist Theo Hermans analyses the metaphors used to describe literal and free translations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in treatises, translators’ prefaces and laudatory poems attached to translations. Besides the language of subjection and servility, there are transformative metaphors, such as digestion and transplantation; dissimulative metaphors, such as clothing; eristic metaphors, including wrestling and treading on heels; metaphors of discovery (e.g. buried treasure); metaphors of outside–inside (e.g. husk and kernel); metaphors of filiation; and metaphors of identification, including metempsychosis. In another discussion, Hermans shows that many of the images evoked by translation theorists involve some degree of manipulation, coercion or violence. His explanation of polysystems, the approach of Gideon Toury and others, applies particularly well to Virgil’s Aeneid:Footnote 130

The theory of the polysystem sees literary translation as one element among many in the constant struggle for domination between the system’s various layers and subdivisions. In a given literature, translations may at certain times constitute a separate subsystem, with its own characteristics and models, or be more or less fully integrated into the indigenous system; they may form part of the system’s prestigious centre or remain a peripheral phenomenon; they may be used as ‘primary’ polemical weapons to challenge the dominant poetics, or they may shore up and reinforce the prevailing conventions. From the point of view of the target literature, all translation implies a degree of manipulation of the source text for a certain purpose.

In other words, the polysystems approach emphasizes the ideological dimensions of translation and translations by examining the cultural norms in which the target text circulates. What this approach neglects, though, is the presence of flesh-and-blood translators, as articulated eloquently by Pym’s plea that we think about translators as real people.Footnote 131

The potential roles of translations connect with the particular cultural contexts of the translator, a topic I explore in Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, with a focus on issues of centre and periphery, the offensive or defensive agendas of translations, and the materiality of translations. In this my approach aligns with that recommended by Pym in Method in Translation History. Pym argues that premodern and early modern translations should be seen primarily as a cultural rather than purely linguistic phenomenon, since they are intended to serve a variety of broadly defined utilitarian objectives. The physical form of the book itself presents a significant cultural indicator of purpose, an issue explored by Anne Coldiron, Marie-Alice Belle, Brenda Hosington and Craig Kallendorf, among others, in their studies of mise-en-page and typography.Footnote 132 In other words, translation participates alongside other types of communication in the idea popularized by Marshall McLuhan in the 1970s that ‘the medium is the message’.Footnote 133

The French translation theorist Antoine Berman identifies the tensions and the resulting risk of violence in his model study of the German Romantics’ ideas on translation:Footnote 134

Every culture resists translation, even if it has an essential need for it. The very aim of translation – to open up in writing a certain relation to the Other, to fertilize what is one’s Own through the mediation of what is Foreign – is diametrically opposed to the ethnocentric structure of every culture, that species of narcissism by which every society wants to be a pure and unadulterated Whole. There is a tinge of the violence of cross-breeding in translation.

This framework underlies my Chapter 1, in which I show how translation of a classic author such as Virgil is used to appropriate foreign cultural capital to kick-start or boost vernacular literary culture. The inevitable cultural resistance, Berman continues, ‘produces a systematics of deformations that operates on the linguistic and literary levels, and that conditions the translator, whether he wants it or not, whether he knows it or not’. These observations take us into the ‘how’ of translation, a multifarious topic that I tackle in Chapters 6, 7, 8 and 9. There are different kinds of ‘deformations’ that translators can produce in their translations, deformations which complicate the labels ‘domesticating’ and ‘foreignizing’, as explored in the final part of Chapter 9. In my final chapter, Chapter 10, I pursue one of the metaphors mentioned earlier, according to which translators identify with their author, even to the degree of claiming metempsychosis. Before I indicate the contents of my ten chapters, I will explain how I came to choose these particular principles of organization.

0.7 The Organization of the Book: What It Is Not and What It Is

I rejected a chronological approach as boring and impossible, given the sheer number of translations. I do, however, include as Appendix 2 a chronological list of the translations mentioned or discussed in the book which will supply a degree of sequential overview. At the same time, I rejected the language-by-language approach because it would obscure important connections, influences and synchronicities between languages.Footnote 135 Instead of a comprehensive overview, I have undertaken a representative study of the cultural history of translations of Virgil, aiming to capture salient elements of the traffic between different languages and cultures, such as we see clearly in the way that travesties of the Aeneid spread from Italy to France and then to England, and later from Austria to Russia and thence to Ukraine and beyond (discussed briefly in Chapter 4). In this I adopt a similar approach to Anne Coldiron, whose important work on translation in the first century of printing in the West, Printers without Borders, is a model of how case studies can constitute more than the sum of their parts. She emphasizes that translations do not fit neatly into national literary histories:Footnote 136