In 1960, the number of immigrants globally was 78 million; by 2024, 304 million (United Nations 2024). This unprecedented movement of people—both over time and across space—means more countries are becoming increasingly diverse. Even the most homogeneous countries, per the Ethnic Power Relations dataset (Cederman, Wimmer, and Min Reference Cederman, Wimmer and Min2010), such as Denmark and South Korea, are facing this phenomenon. And as these newcomers settle down and have children, and their children have children, the diaspora population will also continue to grow.

In this paper, we are interested in the political attitudes of the diaspora population. Specifically, we ask: What explains diaspora attitudes toward their ancestral homeland? One of the earliest arguments put forth by diaspora scholars focuses on pull factors: The diaspora population is likely to have strong affinity for the ancestral homeland based on a shared ethnic identity—an identity that draws on a common language about a distinct culture and memories (Safran Reference Safran1991; also see Leblang Reference Leblang2010). Another explanation emphasizes the push factors: When the diaspora population is racialized, othered, and classified as “perpetual foreigners” (Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2008)—or worse, vilified as a fifth column (Mylonas and Radnitz Reference Mylonas and Radnitz2022)—this can make it difficult for the diaspora to identify positively with the contemporary homeland even if they were born and raised there.

We build on the works of Abramson (Reference Abramson2017), Adamson (Reference Adamson2012), Betts and Jones (Reference Betts and Jones2016), Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2005), Mavroudi (Reference Mavroudi2007), Ragazzi (Reference Ragazzi2014), and Wilcock (Reference Wilcock2020) in recognizing that the link between diaspora and ancestral homeland is malleable. Where we depart from these works is theoretically focusing on language use at home. While language is often a marker of a distinct culture, its use can vary both (1) spatially, i.e., across individuals in the same diaspora; and (2) temporally, i.e., over time by the same community. This variation is important: We argue that when a member of the diaspora cannot speak the language of the ancestral homeland, the link with the ancestral homeland weakens, if not outright breaks. And thus, when the ancestral homeland calls upon the diaspora, the message does not resonate. In contrast, for the member of the diaspora who still uses the language of the ancestral homeland, the link is much stronger, and responses to rhetoric will be more positive.

We test our argument by focusing on the ethnic Chinese diaspora and its political attitude toward the People’s Republic of China (PRC). We do so because we can leverage two empirical features. The first is that the Chinese language is an amalgamation of mutually unintelligible vernaculars. What this suggests is that the diaspora-ancestral homeland link does not manifest in the same vernacular for everyone. This is key since the PRC government puts forth its rhetoric almost exclusively in one singular vernacular: Standard Chinese. The second empirical feature is that the ethnic Chinese diaspora has two governments claiming legitimacy to the ancestral homeland (Hoe Reference Hoe2005; Yang Reference Yang2012). Moreover, since both regimes are relatively new (1911 and 1949), there were waves of Chinese migration out of China predating either regime. When multiple representative bodies claim legitimacy to the same albeit fragmented homeland, this can affect diaspora politics (Panagiotidis Reference Panagiotidis2015). Variation in Chinese diaspora behavior and attitudes is very much linked to the ideology and legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party in China and the Kuomintang and other parties in Taiwan (Han Reference Han2019; Siu Reference Siu, Parreñas and Siu2007)

Here, we should clarify what we mean by diasporas and homelands. Historically, diasporas have meant people who have been expelled from their homeland, e.g., Jews and Armenians (Safran Reference Safran1991). Since then, the category has expanded to include any “segment of a people living outside the homeland” (Connor Reference Connor and Sheffer1986: 16)—whether it is “due to dispersal or immigration” (Grossman Reference Grossman2019: 1267; italicized in original source). Examples of diaspora communities include Cubans (López Reference López2018), Filipinos (Quinsaat Reference Quinsaat2019, Reference Quinsaat2024), Iranians (Cohen and Yefet Reference Cohen and Yefet2021; McAuliffe Reference McAuliffe2008), Russians (Kolstø Reference Kolstø2014), and Turks (Arkilic Reference Arkilic2021). It is important to recognize that while immigrants can be part of the diaspora community, not all members of the diaspora are immigrants. Instead, members of the diaspora can also be second-, third-, or even fourth-generation; these individuals could have been born and raised outside the ancestral homeland. Immigration scholars often call this other country the “host society” (e.g., Maxwell Reference Maxwell2010; Stoessel, Titzmann, and Silbereisen Reference Stoessel, Titzmann and Silbereisen2012). While this may be a factually correct phrase in some cases, it risks classifying all members of the diaspora community as newcomers. Doing so renders those who may have already been in the country for multiple generations as perpetual foreigners. This can have normative implications that we want to avoid. Given this context, we call this other country the “contemporary homeland.”

We also want to note that while our theory is about how language links the diaspora to the ancestral homeland, when we talk about the Chinese diaspora, we use the word vernacular instead. We do so because of its neutral connotation (Tam Reference Tam2020). From a linguistic standpoint, two vernaculars are considered “dialects” when there is 85% mutual intelligibility. American English and British English, for example, are considered dialects. Yet, the vernaculars in China’s southern provinces (e.g., Cantonese) have around 20% mutual intelligibility with Standard Chinese. From a political standpoint, however, a vernacular is considered a “language” when it is a “dialect with an army and a navy”—i.e., it has politically subsumed other dialects (see Chan Reference Chan2021; Liu Reference Liu2015). Consider Cantonese, the vernacular spoken in Hong Kong, Macau, and the surrounding areas in Guangdong Province. Beijing calls Cantonese “yue hua ,” literally the “dialect” of the Guangdong people. Conversely, the Cantonese, including the diaspora in places like London, Sydney, and Vancouver, call the same vernacular “yue yu ,” i.e., the “language” of the Guangdong people. This dialect versus language debate is by no means Cantonese-specific. We see similar discourses surrounding the Hakka and Hokkien vernaculars. The latter is, in fact, known by many of its speakers as tai yu —i.e., “the language of Taiwan”—thus suggesting the very political nature of the dialect versus language debate. Even Standard Chinese, despite being the official vernacular in three countries, has a different name in each one: putonghua (common talk) in China; guoyu (official language) or zhongwen (language of the [imperial] Chinese civilization) in Taiwan; and huayu (language of the [post-imperial] Chinese) in Singapore. To sidestep this political landmine, we opt for the most neutral terminologies: vernacular instead of language or dialect. Likewise, we call the Mandarin vernacular “Standard Chinese.”

Explaining Diaspora Attitudes

Diasporas bridge two worlds. On the one hand, they may have acculturated, assimilated, or integrated with the contemporary homeland culture. The focus then becomes whether their attitudes differ from everyone else’s (e.g., Walker, Roman, and Barreto Reference Walker, Roman and Barreto2020) and whether the contemporary homeland society recognizes members of the diaspora as “one of us”—i.e., whether they are part of the larger ingroup (Liu and Ricks Reference Liu and Ricks2022). On the other hand, they can be seen as extensions of their ancestral homeland—especially those trying to harness the diaspora for soft power (Thunø Reference Thunø2018) and fifth-column purposes (Mylonas and Radnitz Reference Mylonas and Radnitz2022).

The relationship between the diaspora and their ancestral homeland can be complex. They constitute imaginations and attitudes (Morawska Reference Morawska2011). Consider that the history of the diaspora and their experiences can cultivate dispersed identities (Agnew Reference Agnew2005; Bakalian Reference Bakalian2017; Panossian Reference Panossian2004). Similarly, the ecology of the diaspora can reflect ancestral homeland politics (Skrbiš Reference Skrbiš1997; Wayessa Reference Wayessa2024). This happens when the diaspora engages in ancestral homeland politics through the online public sphere, which can reversely affect the composition and components of diaspora politics (Laguerre Reference Laguerre2005; Parham Reference Parham2005). Furthermore, memories of the ancestral homeland can contribute to the formation and variation of diasporic identity (Davidson and Khun Eng Reference Davidson and Khun Eng2008; Naïïli Reference Naïïli2009). The heritage the diaspora carries from their ancestral homeland becomes the foundation of hybrid identities (Ang Reference Ang2003; Smith and Leavy Reference Smith and Leavy2008).

Yet, in this hybridity, there is often an implied zero-sum dynamic (c.f., Marquardt Reference Marquardt2017, Reference Marquardt2021; Sen Reference Sen2000): the more a member of the diaspora is attached to the ancestral homeland, the less they identify with the contemporary host culture—and vice versa (see Stoessel, Titzmann, and Silbereisen Reference Stoessel, Titzmann and Silbereisen2012; Tartakovsky Reference Tartakovsky2008, Reference Tartakovsky2009). We see this across a range of individual-level factors, including place of birth—i.e., those born in the contemporary homeland are less likely to identify with the ancestral homeland (Citrin and Wright Reference Citrin and Wright2014; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2010); age—e.g., older people are more likely to identify with the ancestral homeland; younger people, however, are not because of attachment to memories (Haller and Landolt Reference Haller and Landolt2005); gender—e.g., school-aged boys are more likely to report negative experiences with multiculturalism (see Schachner et al., Reference Schachner, Juang, Moffitt and van de Vijver2018); and socioeconomic status—i.e., those who have had less education are less likely to have assimilated and feel included in the contemporary homeland (Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez1999).

We can group the mechanisms accounting for diaspora attitudes into two sets. Note that two sets need not be mutually exclusive. The first is that there is a pull—i.e., there is some sort of affinity that draws the diaspora back. At the individual level, individuals who are connected are, all else being equal, more positive about their ancestral homeland. This connection can be physical: e.g., family presence (Chiswick and Miller Reference Chiswick and Miller1996) and property ownership (Li and Chan 2018). It can also be cultural: e.g., media consumption (Moss Reference Moss2020). Technological development—from printed media to social media platforms—has made it possible for the diaspora to not just maintain literal ties with the ancestral homeland but also be immersed in the figurative symbols and narratives of the culture. This is the case from the non-English speaking diaspora communities in Australia (Chiswick and Miller Reference Chiswick and Miller1996) to the Hungarian-concentrated areas outside of Hungary, e.g., Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Ukraine (Csata et al. Reference Csata, Compton, Liu and Attila Papp2024) to the Cameroonian neighborhoods in Oslo (Mainsah Reference Mainsah2009).

This pull, however, does not manifest simply at the individual level; it is also matched by what is going on in the ancestral homeland (Gamlen Reference Gamlen2018; Koinova and Tsourapas Reference Koinova and Tsourapas2018; Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi2014). Who in the ancestral homeland is doing the pulling varies: from the government to specific political parties; from diaspora entrepreneurs in civil society to international institutions (Délano Alonso and Mylonas Reference Délano Alonso and Mylonas2017; Amato Reference Amato, Amato and Pyun2024; Glasius Reference Glasius2017). Regardless of which agent(s) is responsible for the pull, ancestral homelands can try to harness the diaspora and build a network with an array of policies (Dickinson Reference Dickinson2017; Gamlen Reference Gamlen2014; Smith Reference Smith1999). These efforts can happen for instrumental reasons such as soft power diplomacy (Cohen Reference Cohen2017; Gamlen Reference Gamlen2008). They can also happen for explicit interest-based reasons—whether it is increasing vote shares (Reidy Reference Reidy2021) or tourism numbers (Abramson Reference Abramson2017; Coles and Timothy Reference Coles and Timothy2004); whether it is increasing investments (Leblang Reference Leblang2010) and remittances (Leblang Reference Leblang2017), addressing brain drain (Rhee and Yin Reference Rhee, Yin, Yudkevich, Altbach and Salmi2023; Tsourapas Reference Tsourapas2015), or inducing philanthropy (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2008; Sidel Reference Sidel2008).

We see the harnessing of diaspora with technological developments. The proliferation of social media allows for the mobilization of a distinct identity (Adamson and Demetriou Reference Adamson and Demetriou2007) where there are narratives of imagined communities (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2009; Van Hear and Cohen Reference Cohen2017). When governments of ancestral homelands talk about the historical greatness of the civilization and its rightful place in the global order, this rhetoric can be attractive to the diaspora abroad who themselves may be detached from the contemporary homeland country (Wayland Reference Wayland2004) and are looking to preserve their identity (Wilcock Reference Wilcock2020). Sirseloudi (Reference Sirseloudi2012) talks about precise mechanism when examining the Turkish diaspora in Germany. These tensions are even more pronounced when relations between the two homelands are hostile. Under such regime and ideological strains, the ancestral homeland has a structural opportunity to introduce a wedge narrative (Chester and Wong Reference Chester and Wong2023; Greitens Reference Greitens2024; also see Adamson Reference Adamson2019, Koinova and Tsourapas Reference Koinova and Tsourapas2018; Zhou and Liu Reference Zhou, Liu and Zhou2017).

In contrast to the pull, the second set of mechanisms for explaining diaspora attitudes focuses on the push. If there are barriers in the contemporary homeland, it can be challenging for the diaspora to feel welcomed (Berry Reference Berry1997). For example, it matters whether the diaspora can access state resources (Délano Reference Délano2011; Entzinger Reference Entzinger2005). Even if there is a clearly delineated legal path, at the individual level, experiences can shape perceptions (Huang, Hung, and Chen Reference Huang, Hung and Chen2018; Zou, Meng, and Li Reference Zou, Meng and Li2021). When discrimination is widespread, these feelings of being a “perpetual foreigner” (Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2008) can make it difficult to identify with the contemporary homeland (see Decimo and Gribaldo Reference Decimo, Gribaldo, Decimo and Gribaldo2017; Prinz Reference Prinz2019; Westle and Buchheim Reference Westle, Buchheim, Westle and Segatti2016).

Experiences of discrimination and inclusion, however, do not happen strictly at the individual level. Instead, they are often linked to contemporary homeland politics (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Brown, Brown and Marks2002)—i.e., should the government compete with, be in conflict with, accommodate, or assimilate the diaspora (Rumbaut Reference Rumbaut2015)? We see this calculus play out in the education curriculum: When textbooks denigrate the diaspora as a cultural threat, this impacts how others treat the diaspora (Cohen Reference Cohen2004; Ng Reference Ng2003; Wee Reference Wee2003). We also see this politics in census classifications. At one extreme, governments can go to great lengths to demarcate the diaspora. In Indonesia, the ethnic Chinese have been excluded from the panethnic Indonesian pribumi classification (Setijadi Reference Setijadi2017, Reference Setijadi, F and Ricci2019, Reference Setijadi2023). Likewise, in Myanmar, the ethnic Chinese, Indians, and Rohingyas have been recognized legally as non-taingyintar (Jap Reference Jap2021). Conversely, at the other extreme, governments in the contemporary homeland can make efforts to erase the diaspora’s distinct identity. We see this in Thailand, where the ethnic Chinese and ethnic Lao diasporas became “Thai” through a process of nation-building that included both sticks and carrots (Phongphichit Reference Phongphichit2010; Tejapira Reference Tejapira2009; Wasana Reference Wasana2019).

Across these arguments is often the assumption of some primordial link between the diaspora and the ancestral homeland. This primordial link is based on some shared culture that is passed down through the generations (Geertz Reference Geertz, Hutchinson and Anthony1994). It is a link that is fixed; it is either always there or, if it goes dormant, it is one that can be easily revived. Yet, there is also research that shows that individual identities and attitudes are malleable—especially when situated in multiple cultural environments (Cheng and Lee Reference Cheng and Lee2013; Chiou and Mercado Reference Chiou and Mercado2016). Connections to a place—e.g., ancestral homeland or contemporary homeland—can become ambiguous or severed (Hundt Reference Hundt2014; Khun Eng Reference Khun Eng2006). We discuss the dynamism of this link and offer a theory of how it affects diaspora attitudes in the next section.

Language and the Homelands

One common vehicle for the primordial link between diaspora and ancestral homeland is language. Language is often a marker (Chandra Reference Chandra2006)—if not, the marker (Tocqueville Reference Tocqueville1835/2002)—of a distinct culture. It identifies the ingroup; and just as importantly, it demarcates the outgroup (Brown and Ganguly Reference Brown, Ganguly, Brown and Ganguly2003). Simply put, the language of the diaspora should match the language of the ancestral homeland.

While language is an important cultural if not civilizational marker, there may be endogenous reasons for incongruence between the diaspora and the ancestral homeland (Marquardt Reference Marquardt2017, Reference Marquardt2021). One reason has to do with the linguistic repertoire of the individuals in the diaspora. Languages can be lost: when someone does not use a language for an extended period, they can lose proficiency in it. And on a larger scale, a group can lose its language over generations. We see this with Akkadian and Latin; and we see it with the countless indigenous languages that are endangered. Just as languages can be lost, conversely, languages can also be learned. While every individual may have a “mother tongue,” they can also learn second or third languages and become more proficient in one of these later languages than their mother tongue. We see this shift with immigrants who may have sufficiently assimilated and become more fluent in the contemporary homeland language. In short, the language of individuals within the diaspora may change.

The second reason for the incongruence has to do with the ancestral homeland. Even if the territorial boundaries of the ancestral homeland remain unchanged, the government and the regime sitting in the capital governing over the land can. This can have implications for language policies. It is neither implausible nor unusual for governments to change the official/national language(s) of the state. Some governments have chosen to replace one language with another—e.g., Timor-Leste (Tétum for Indonesian); others have simply removed one language—e.g., Malaysia (English) and Ukraine (Russian); while others have added languages—e.g., Ireland (Gaelic) and Luxembourg (Luxembourgish).

These language policies are inherently political in that they suggest who belongs to the ancestral homeland and who does not (Liu Reference Liu2015). What this means is that when a former language of the ancestral homeland is no longer recognized by the new regime, the diaspora—particularly if it left before the regime change—loses its association. While they may still have that primordial 23-and-me link, their emotional attachment to that land has now been severed. Put differently, while they may still have memories and hand-me-down stories, their visceral attachment to and trust of the current government is very superficial, if not outright negative.

We do not assume what language is spoken at home by the diaspora. It can be the language of the ancestral homeland. It can be the language of the contemporary homeland. It can also be both or neither one. Whichever language is spoken is the one that shapes their identity and attitudes to both homelands. We know languages can shape public opinions (Lee and Pérez Reference Lee and Pérez2014; Pérez Reference Pérez2016). In the same vein, the logic is that when there is congruence between the language of the individual in the diaspora and the official language of the ancestral homeland—all else being equal—the individual in the diaspora is going to hold the ancestral homeland in a more positive light. However, when there is incongruence due to changes to the individual linguistic repertoire and/or politics in the ancestral homeland, the link breaks. Note that we are not contesting that language is the only mechanism that matters for the link. Links can break for nonlinguistic reasons. We are, however, arguing that speaking the ancestral language matters for maintaining said association. This discussion brings us to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis: A member of the diaspora community is less positive about the ancestral homeland when they do not speak the official language of the ancestral homeland at home.

The Ethnic Chinese Diaspora and the People’s Republic of China

In this paper, we focus on the ethnic Chinese diaspora for three reasons. First, the Chinese diaspora—at 40 million (Tan Reference Tan2006)—is the largest diaspora population in the world, rendering it a normatively important case. One of the major waves in contemporary history was in the 19th century during the Qing Dynasty. Large numbers of ethnic Chinese from southern China (namely, Fujian and Guangdong) emigrated to all corners of the world, including Southeast Asia (Suryadinata Reference Suryadinata1997), Australia (Chan Reference Chan and Tan2007), the Americas (Carranzo Ko Reference Ko2017; Hsu Reference Hsu2015; Hu-Dehart Reference Hu-DeHart1980, Reference Hu-DeHart1989, Reference Hu-Dehart1993), and Europe (Benton and Pieke Reference Benton and Pieke1998). Figure 1 shows the spread of the ethnic Chinese diaspora today. Initially, many engaged in hard labor. Over time, there was the shift to shopkeepers, merchants, and middlemen. While many returned to China, large numbers remained. For those who stayed, they established local schools, social associations, and other civic organizations (Wu Reference Wu2021).

Figure 1. The ethnic Chinese diaspora globally.

Note: Map created by authors using data from Ethnic Power Relations database and individual country census.

Second, the Chinese language offers unique leverages for empirical testing. China is home to a diversity of vernaculars, including Standard Chinese, Cantonese, and Hokkien. When spoken, each one of these vernaculars is mutually unintelligible with each other—and more importantly with Standard Chinese. The overlap between these vernaculars can be as low as 20% (Liu Reference Liu2021).Footnote 1 While Standard Chinese is the official language of China today, this has not always been the case—in speaking or writing. It only became the de jure official language in 1911 when the Qing Dynasty was toppled. And even then, a century later, it was still not the de facto lingua franca. PRC’s first nationwide language census—the 2004 Survey of China’s Language Use—indicated only half of the population (53.06%) was proficient in Standard Chinese (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 2004). And while the number has since increased to 80.7% in 2020, this development was the product of intense top-down Standard Chinese promotion campaigns and the spread of social media (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 2021). In short, there is substantial differentiation between what is spoken by the diaspora globally and the contemporary official language of the ancestral homeland.

Third, Chinese politics provides us with a natural experiment. The literature on diaspora attitudes often focuses on an ancestral homeland where the rhetoric has escalated—e.g., Jews with Netanyahu, Hungarians with Orbán, and Turks with Erdogan. While the political landscape in the ancestral homeland can change, it is one thing when it is about escalating rhetoric; it is another matter when the political regime—if not the entire empire—collapses. The transition from (1) the Qing Dynasty to a nationalist republic and then the subsequent transition from (2) a nationalist republic to a communist dictatorship is nothing short of extreme. These are overnight shocks to the diaspora on whether and, if so, how they identify with the ancestral homeland. As noted just above, one such shock was the recognition of Standard Chinese as the official language—again, a vernacular that most of the diaspora overseas neither spoke nor wrote. This drastic change makes it possible to identify affinity beyond some primordial connection.

Research Design: Sinophone Borderlands

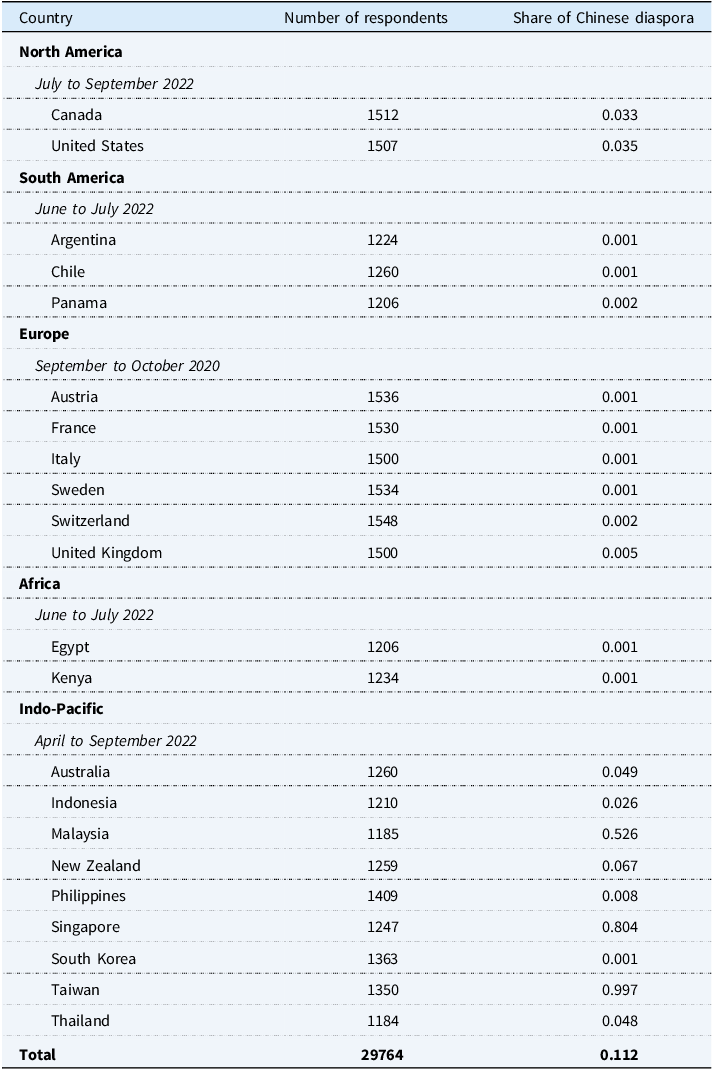

To measure attitudes toward China, we employ original data from the Sinophone Borderlands project.Footnote 2 The project aimed to understand global attitudes toward China—from policy preferences to views about social and human rights issues. In all, nationally representative surveys were administered in 56 countries between 2020 and 2022 (N > 80,000). In this paper, we focus on the 22 surveyed countries where there was at least one ethnic Chinese respondent (N = 29,764). Table 1 shows the list of countries, survey period, the number of respondents, and the share of which were ethnic Chinese respondents.

Table 1. The ethnic Chinese diaspora in the Sinophone Borderlands Survey

To identify the ethnic Chinese diaspora sample, we focus on two questions. The first is their ethnic identity: “What do you identify yourself as?” We note any respondent who answers Chinese or some derivative thereof as a member of the ethnic Chinese diasporaFootnote 3 . The second question is about the language spoken at home. We code for any respondent who answered Chinese or a specific Chinese vernacular. We do, however, take care to differentiate whether the vernacular is Standard Chinese and/or non-Standard Chinese (most common: Hokkien). In all, 11.23% of the respondents (N = 3343) are considered part of the ethnic Chinese diaspora. As we see in Table 1, most of the ethnic Chinese diaspora are in Singapore (N = 1002) and Taiwan (N = 1345). Not coincidentally, these are two of the three ethnic Chinese-majority countries in the world (Hu and Liu Reference Hu and Liu2020; Liu Reference Liu2021). To ensure the results are not driven by these cases—whether computationally or politically—we also run our models with the two excluded for robustness purposes (more below).

To measure attitudes toward China, we focus on a battery of feeling thermometer questions. In all, there are nine questions about how the respondents feel toward China, where 0 represents cold, negative feelings and 100 represents warm, positive feelings. The questions focus on (1) trade with China; (2) Chinese investments; (3) China’s rise as major power; (4) China’s military power; (5) China’s technology; (6) Belt and Road Initiative; (7) China’s impact on the global natural environment; (8) China’s influence on democracy in other countries; and (9) promotion of Chinese culture and language. The alpha Cronbach score between the nine measures is 0.9452. Given this, we aggregate the nine measures by taking the average. It seems that across all 22 countries and nine measures, the average feeling toward China is quite neutral: 47.40.

Results

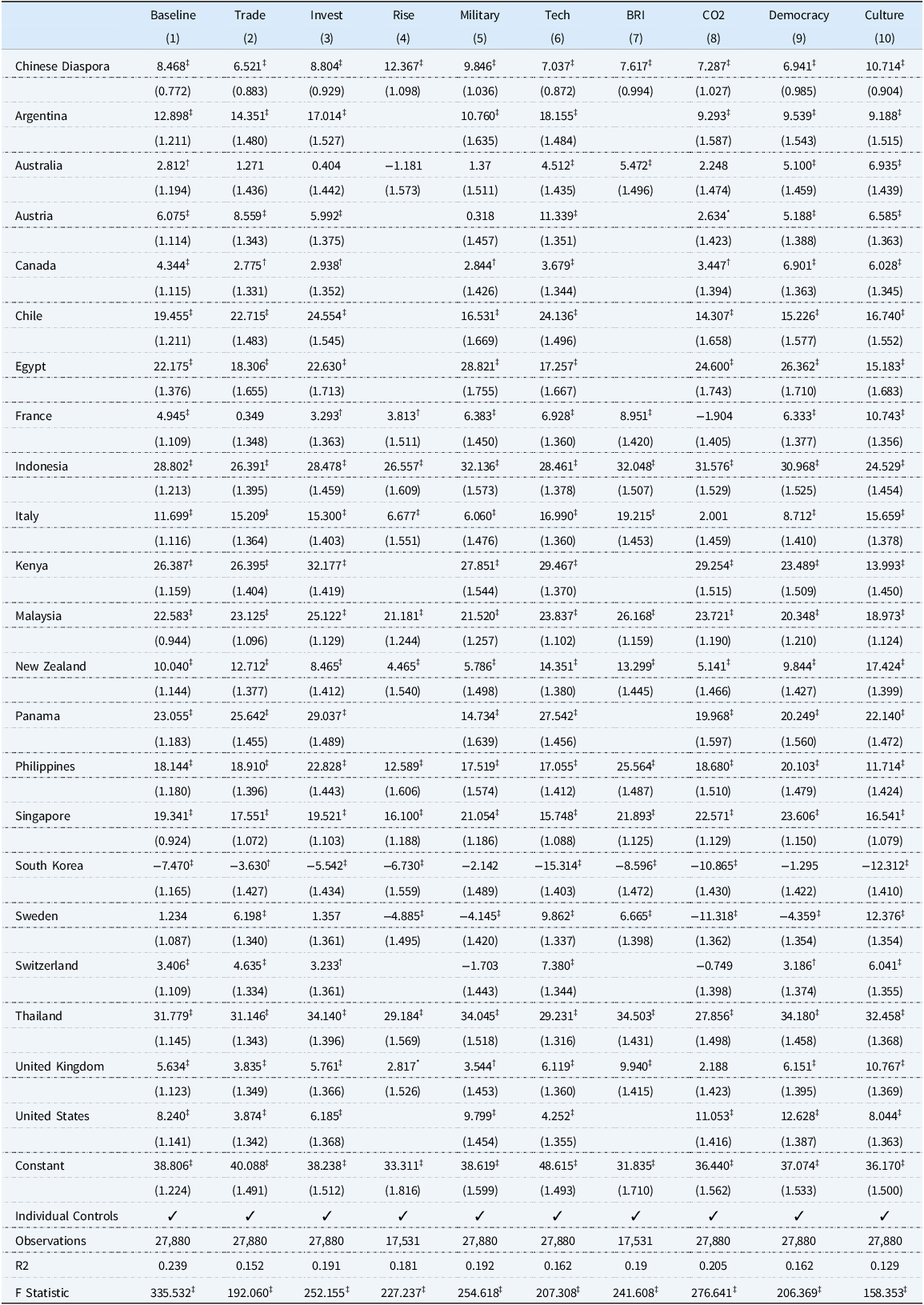

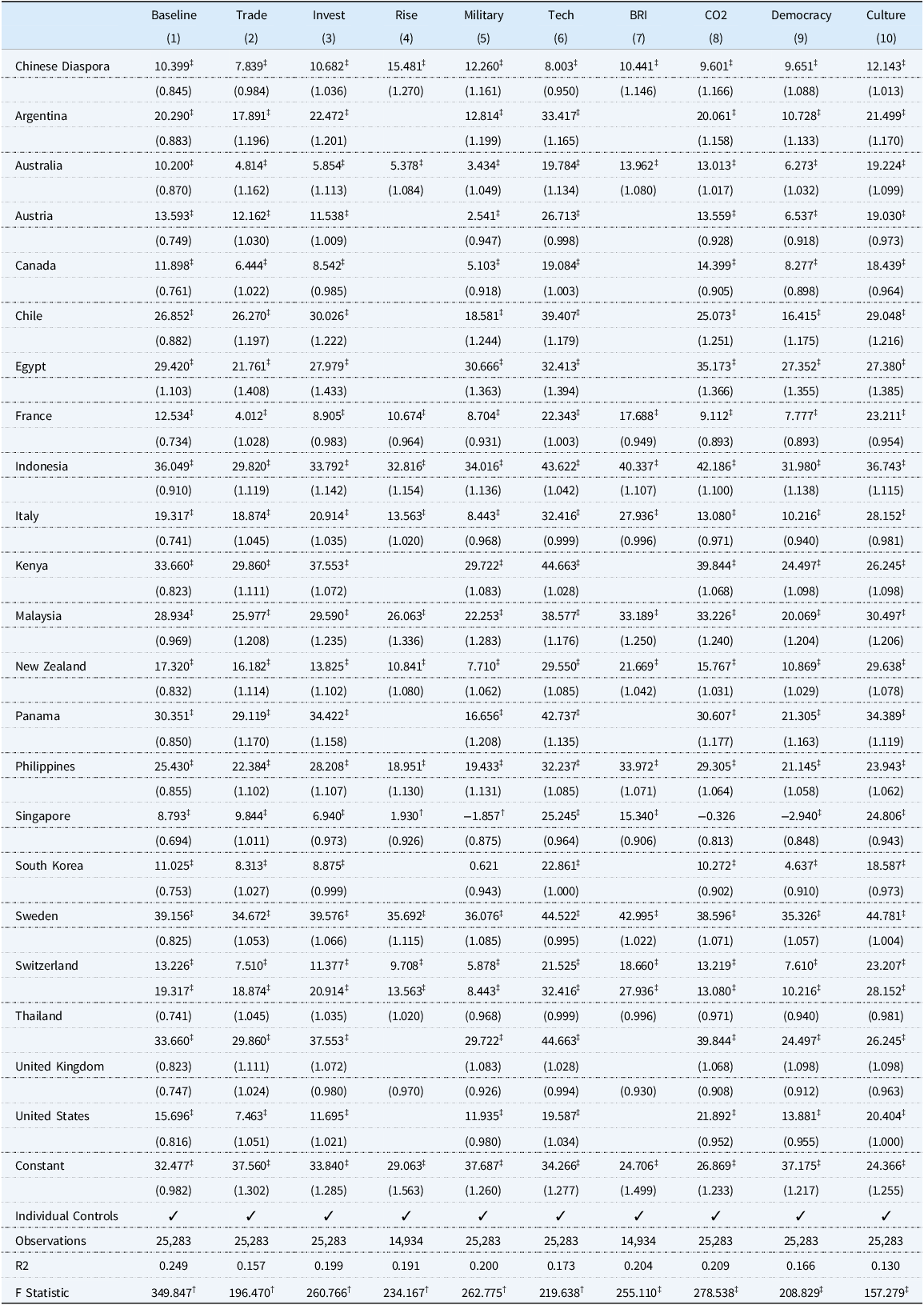

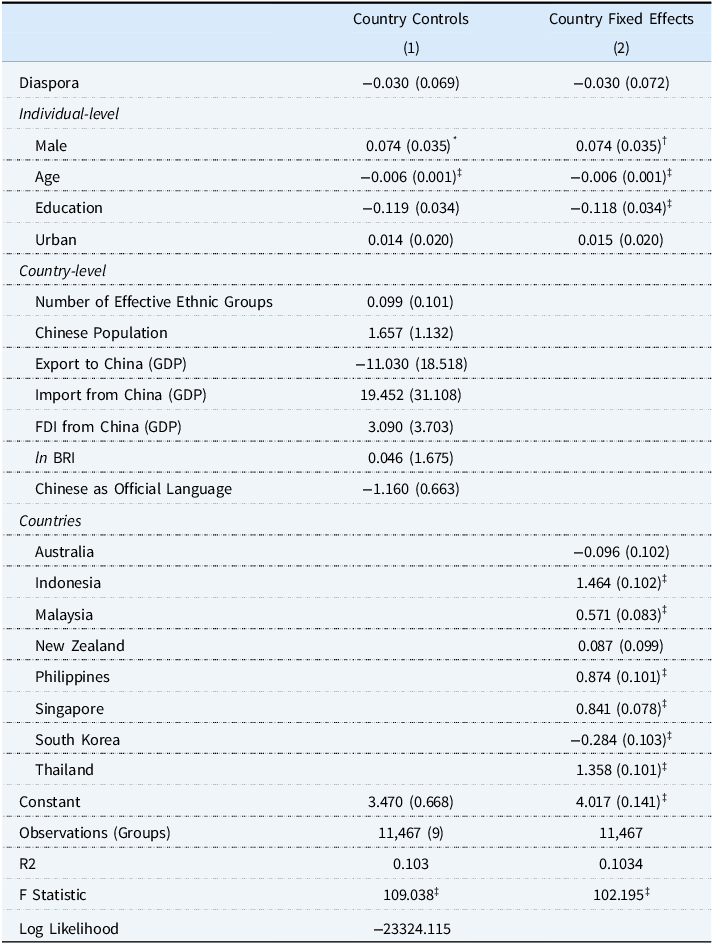

We begin by assessing first and foremost whether ethnic Chinese respondents are—all else being equal—more supportive of China than non-ethnic Chinese respondents. The results in Table 2 suggest this is the case. As a reminder, we consider a respondent to be part of the ethnic Chinese diaspora if they identify as Chinese and/or speak a Chinese vernacular at home. In Model 1, we look at diaspora attitudes toward China in aggregate. This is the average indexed score across all nine feeling thermometers. We see that the diaspora respondent is about eight percentage points more positive toward China than a non-diaspora respondent. Note that these effects are by no means being driven by either Singapore or Taiwan. As we see in Table 3, the results remain substantively unchanged across all ten models when we exclude the two cases.

Table 2. Diaspora versus non-diaspora attitudes toward China (Singapore and Taiwan included)

Notes: Coefficients are reported with robust standard errors in parentheses. Models estimated with multilevel effects linear regression. Individual controls: male (=1), age (continuous between 18–65), education (primary/secondary/tertiary), and urban (four-point category). Reference category: Taiwan. *p < 0.100; †p < 0.050; ‡p < 0.010.

Table 3. Diaspora versus non-diaspora attitudes toward China (Singapore and Taiwan excluded)

Notes: Respondents from Singapore and Taiwan removed. Coefficients are reported with robust standard errors in parentheses. Models estimated with multilevel effects linear regression. Individual controls: male (=1), age (continuous between 18–65), education (primary/secondary/tertiary), and urban (four-point category). Reference category: South Korea. *p < 0.100; †p < 0.050; ‡p < 0.010.

Next, we rerun the same model but focus on each individual feeling thermometer. Model 2 (in both Tables 2 and 3), for example, focuses on trade with China. Diaspora respondents are six percentage points more positive than non-diaspora respondents. Interestingly, this is the smallest difference across all measures. In contrast, the two largest—perhaps not surprisingly—are China’s rise as a major power (Model 4) and the promotion of Chinese culture and language (Model 10). In both measures, diaspora respondents were more than ten percentage points more positive about China than non-diaspora respondents.

Among the country controls, it seems attitudes in South Korea are the most negative. Anecdotally, this is not surprising given the historical legacies, including an ethnic Chinese community in South Korea that struggled to integrate (Rhee Reference Rhee and Fernandez2009). Empirically, however, this result could also be driven by the very small number of ethnic Chinese diaspora respondents in South Korea. Put differently, there are simply a lot more negative non-diaspora respondents in the South Korean sample. Attitudes toward China are also relatively negative in Taiwan—the reference country in the model. In contrast, we see that the most positive attitudes are in Thailand and Indonesia. This is not wholly surprising given the sizable Chinese diaspora populations and strong economic relations with China for both countries.

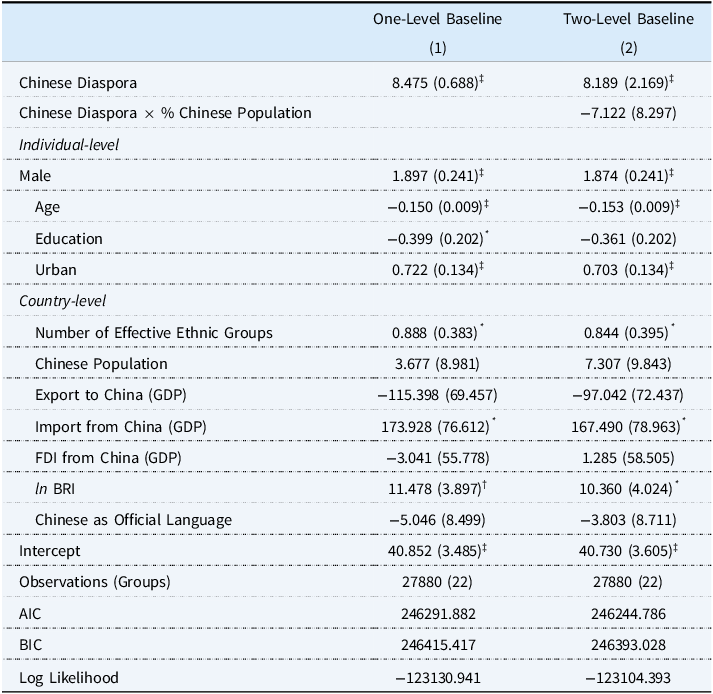

Given that we see variations across countries, it is possible that individual attitudes toward China are also influenced by country-specific factors. To consider this, we run a mixed-effect model where we control for (1) the number of political relevant groups (Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Bormann, Rüegger, Cederman, Hunziker and Girardin2015); (2) share of Chinese population as of 2021 (data sources: Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Bormann, Rüegger, Cederman, Hunziker and Girardin2015 if available; if not, country census); (3) export to PRC as a share of total gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022; (4) import from PRC as a share of total GDP in 2022; (5) foreign direct investment from PRC as a share of total GDP in 2022; (6) whether the country is a participant of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); and (7) whether Chinese is an official language.

The results in Table 4 show that being ethnic Chinese generally increases positive attitudes toward China. This effect, however, does not vary with the share of the Chinese population in the country. As we see in Model 2, the interaction between diaspora and share of Chinese population is not statistically significant. In fact, the negative correlation between the random intercept and random slope for diaspora indicate that in countries with higher baseline attitudes toward China, the positive effect of being part of the diaspora is smaller.

Table 4. Mixed effects model of attitudes toward China

Note: Coefficients are reported with robust standard errors in parentheses. Models are estimated using two-level linear regression with mixed effects. The 22 countries are included; Taiwan is the base category. *p < 0.100; †p < 0.050; ‡p < 0.010.

At the country level, PRC import levels have a marginally significant positive effect on attitude toward PRC. Additionally, being part of the BRI is associated with a 10.36 unit increase in attitude toward PRC, holding other variables constant. This effect is statistically significant, but the impact could be both ways, as countries in which public opinion is more favorable toward PRC were more likely to have joined BRI in the first place.

While these results—robust across model specifications—highlight that there are country-level effects at play, it is possible that at the individual level, there is also preference falsification. For example, it is possible that ethnic Chinese respondents are more inclined to answer positively about China across the board, precisely because it is about China and not because they truly feel that way. To assess this, we focus on an intentional negative test. There is a question about China’s future with respect to democracy: Do you believe that China will become democratic one day? Responses range on a seven-point scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” If there is an ethnic Chinese-identity-driven falsification going on, we would expect the effects to also be significant. Yet, as we see in Table 5—using both mixed effects (Model 1) and multilevel linear effects (Model 2)— this is not the case. An ethnic Chinese respondent is no more likely to believe that China will be democratic than a non-ethnic Chinese respondent. And, in fact, the coefficient is negative.

Table 5. Mixed effects model of attitudes toward China

Note: Model 1 estimates perceptions of China’s democratic values using linear mixed-effects regression for 9 countries (Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, and Taiwan). A random intercept is specified for each country to account for unobserved heterogeneity. Coefficients are reported with robust standard errors using Satterthwaite’s method. In Model 2, the sample is restricted to diaspora respondents with Taiwan as the reference category, and coefficients are reported with robust standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.100; †p < 0.050; ‡p < 0.010.

Mechanism: Chinese Ethnicity versus Chinese Vernacular

If the ethnic Chinese diaspora is more positive toward China, what is the mechanism driving this affinity? On the one hand, it could be driven by some exogenous primordial identity. Simply put, there is some innate pull of the ancestral homeland. On the other hand, it could be the result of something more endogenous. Our argument is that the language spoken at home facilitates an understanding of how people in the ancestral homeland talk and see themselves on the global stage. In other words, language facilitates some shared group consciousness and possibly linked fate at the global level (McClain et al. Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009).

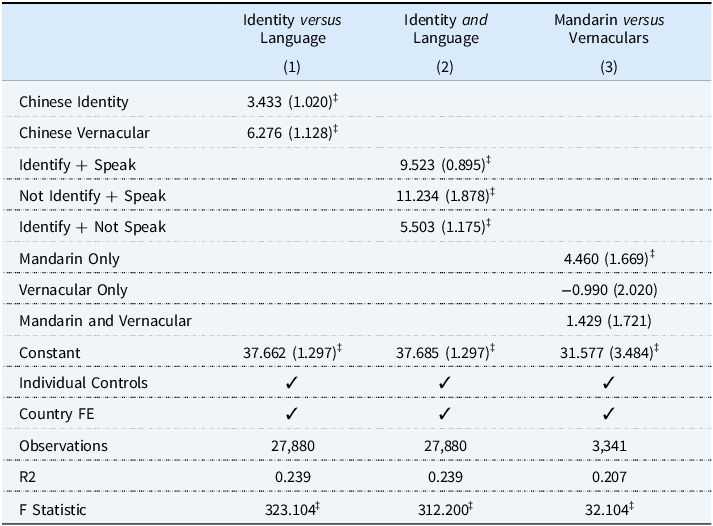

To assess which of the two is driving the ethnic Chinese diaspora affinity—i.e., is it about being Chinese or speaking Chinese—we rerun the baseline index model. This time, however, we disaggregate diaspora into those who identified as being ethnic Chinese (Chinese Identity=1; N = 3185) versus those who speak a Chinese vernacular—any Chinese vernacular—at home (Chinese Vernacular=1; N = 2946). We see the results in Table 6 (Model 1). While the coefficient for the vernacular is larger than that of ethnic identity, the difference in the two coefficients is in fact not statistically significant (p-value = 0.102). It seems both the identity and instrumental mechanisms are at play.

Table 6. Disaggregating the diaspora population

Note: Coefficients are reported with robust standard errors in parentheses. Models are estimated using multilevel-effects linear regression. The sample is restricted to diaspora respondents. *p < 0.100; †p < 0.050; ‡p < 0.010.

The two mechanisms are by no means mutually exclusive. In fact, identity and language run together so frequently that they are often conflated (see Liu and Ricks Reference Liu and Ricks2022). Yet, that is not the case. For example, it is possible that an ethnic Chinese respondent can speak a Chinese vernacular but does not speak it at home because they live with people who do not speak it. Alternatively, it is possible that an ethnic Chinese respondent cannot speak a Chinese vernacular because they have acculturated, assimilated, or integrated. Conversely, it is also possible that an ethnic Chinese respondent has acculturated, assimilated, or integrated so sufficiently that they do not identify as being ethnically Chinese on the survey; however, they still can speak a Chinese vernacular at home with their family.

To tease out whether identity or language is a necessary or sufficient condition and whether the presence of both exponentiates the diaspora attitudes, we break down the diaspora into four groups: (1) those that identify as being ethnic Chinese but do not speak a Chinese vernacular at home; (2) those that do not identify as ethnic Chinese but do speak a Chinese vernacular at home; (3) those that identify as ethnic Chinese and do speak a Chinese vernacular at home; and (4) those who neither identify as ethnic Chinese nor speak a Chinese vernacular at home.

The results in Model 2 are interesting. We find language appears to play a stronger role than identity in predicting a respondent’s attitudes toward China. In this estimation, the base category is the group who do not identify as Chinese and do not speak vernacular Chinese at home. Respondents who do speak a Chinese vernacular at home are generally much more positive regardless of their identity. Among respondents who identify as Chinese, speaking a vernacular at home is associated with a four–percentage-point increase in positive attitudes toward China, whereas among respondents who do not identify as Chinese, the increase is 11 percentage points. Both effects are statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

Conversely, consider that among those who do speak a vernacular, identifying as Chinese does not make a statistically significant difference in their feeling toward China. It seems that Chinese identity only has a statistically significant effect among those who do not speak any vernacular (i.e., about 5.5 percentage points). This suggests a possible group consciousness and linked fate mechanism. In these surveys, respondents are asked to self-identify their ethnicity. While there may be no survey enumerator sitting across from the respondent,Footnote 4 the surveys were administered by local companies that were not necessarily associated with being “Chinese.” As such, in cases like Indonesia and Thailand, where there were substantial efforts to de-Sinicize the ethnic Chinese population historically, it is possible that an ethnic Chinese respondent opted to answer with the broader pan-ethnic identity (Indonesian or Thai). Yet when asked about what languages were spoken at home, they answered with a Chinese vernacular. It is these individuals and not those who have been able to identify publicly as ethnic Chinese and speak a Chinese vernacular without concern (for example, in Malaysia or Singapore) that may exhibit more group consciousness and linked fate with China more generally.

Observable Implication: Disaggregating Chinese Vernaculars

While Standard Chinese has become the dominant Chinese vernacular, it is far from the only one spoken by the diaspora. There are reasons to suspect respondents who speak Cantonese, Hakka, and/or Hokkien at home are inclined to feel differently than their Standard Chinese-speaking counterparts about China. One reason is that their ancestors left China before Standard Chinese became the official language. Another is that while they may have emigrated more recently in the Standard Chinese-official era, they are from a region where Cantonese, Hakka, and Hokkien are widely spoken. These regions tend to be in southern China, where the distance—not just in terms of miles, but also in terms of emotions—to Beijing is large. We consider this by disaggregating the Chinese vernacular. We identify respondents who answered (1) Standard Chinese only (N = 1266), (2) a non-Standard Chinese vernacular (N = 334), and (3) Standard Chinese and a non-Standard Chinese vernacular (N = 1346).

The results in Table 5 (Model 3) demonstrate the importance of disaggregating the diaspora. While respondents who only speak Standard Chinese at home are almost four percentage points more positive (than non-Chinese speaking diaspora), the same cannot be said for those who speak a non-Standard Chinese vernacular at home. In fact, those who speak only a non-Standard Chinese vernacular at home (e.g., Cantonese, Hakka, or Hokkien) are almost one percentage point less positive about China than a diaspora respondent who cannot speak a Chinese vernacular, and the difference between coefficients of Standard Chinese-only and vernacular-only is statistically significant. This suggests a political disconnect from—if not disapproval of—contemporary China.

Interestingly, the coefficient for those who speak both Standard Chinese and non-Standard Chinese vernaculars at home is not statistically significant. There could be two types of respondents in this mixed category. One type is those from a predominantly non-Standard Chinese vernacular family—and with its associated anti-China attitudes. However, there is also recognition that Standard Chinese is an important vernacular for business; it is also possible that it is the only vernacular available at the local Chinese vernacular schools. And as such, the Standard Chinese spoken at home is very instrumental. The second type of respondent is a first generation—if not an immigrant—from a southern province. The experience of living in China could mean having some proficiency in Standard Chinese.

Conclusion

This paper examines diaspora attitudes toward their ancestral homeland. Specifically, it focuses on the language spoken at home and whether it was congruent with the official language of the ancestral homeland. We argue that when there is incongruence, the link breaks. Links can break because the individual (or their family over generations) changed linguistic repertoires or because the ancestral homeland changed what it considered to be official language. The empirical evidence focusing on the ethnic Chinese diaspora globally lends support to this argument.

The Sinophone Borderlands Survey, unfortunately, does not ask how long the respondent has been in the country. For example, there is no question asking whether the respondent was born in the contemporary homeland (foreign born status), and related, whether both of their parents were as well (generation status). Such questions would allow us to differentiate between (1) an ethnic Chinese who was born to parents who were also born and raised in the contemporary homeland; and (2) an ethnic Chinese who was born and raised in a non-Standard Chinese-speaking household in the PRC but fled China. Both types of respondents would show up as ethnic Chinese who do not speak Standard Chinese and have no positive attachment to China. While these two individuals are qualitatively different, they both suggest the lack of uniformity in attitudes among the diaspora.

By focusing on when the linguistic link between diaspora and the ancestral homeland can break, this paper highlights how diasporas are not necessarily fifth columns.Footnote 5 They are not necessarily some human capital stock for the ancestral homeland to bring out of dormancy. This is not to say ancestral homelands are not guilty of introducing wedge narratives. But to assume—and to respond from a policy standpoint—that all individuals in the diaspora are susceptible to such calls is dangerous. It ignores how some in the diaspora may, in fact, hold negative attitudes toward their ancestral homeland. And even if individuals have positive attitudes, it does not warrant them being construed as a threat by default.

Likewise, it is possible that members of the diaspora may identify very much with their contemporary homelands (see Koinova Reference Koinova2021). By definition, ethnic Chinese who chose not to identify as Chinese and who do not speak a Chinese vernacular at home are “uncountable” in our survey. They simply get coded as members of the hegemon. Yet, as we witnessed during the pandemic, the rise of anti-Asian (Chinese) hate—from the United States to Europe, from Canada to Australia—highlights how even those who are fully assimilated and integrated can still be “perpetual foreigners.” Unfortunately, the politicization and vilification of an outgroup are not specific to the Chinese or Asians. We saw it with the Germans during the World Wars, those from communist countries during the Cold War, and the Muslims after 9/11. For this reason, it is imperative that we better understand diasporas and their attitudes toward not just the ancestral homeland but also their contemporary one.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at University of California, Berkeley (2022), Palacký University, Olomouc (2022), and University of Texas at Austin (2023). Many thanks to the organizers and participants at these workshops for their helpful comments—and in particular Regina Branton, Kristina Kironska, and Madeline Hsu. We also appreciate feedback from the anonymous reviewers.

Funding statement

Richard Turcsanyi was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (Grantová Agentura České Republiky, GAČR), as part of the research project “Public attraction to non-democratic regimes: A case study of China,” project no. 24-10048S.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.